Some Democrats angling for the 2020 presidential nomination have a big idea: a basic jobs guarantee, where the government promises a job to anybody who wants one. Cory Booker, Kirsten Gillibrand, Elizabeth Warren, and Bernie Sanders are all said to be considering the plan.

I’ve pushed for a basic income guarantee before, and basic job guarantees sure sound similar. Some thinkers have even compared the two plans, pointing out various advantages of basic jobs: it feels “fairer” to make people work for their money, maybe there’s a psychological boost from being productive, you can use the labor to do useful projects. Simon Sarris has a long and excellent article on “why basic jobs might fare better than UBI [universal basic income]”, saying that:

UBI’s blanket-of-money approach optimizes for a certain kind of poverty, but it may create more in the long run. Basic Jobs introduce work and opportunity for communities, which may be a better welfare optimization strategy, and we could do it while keeping a targeted approach to aiding the poorest.

I am totally against this. Maybe basic jobs are better than nothing, but I have an absolute 100% revulsion at the idea of implementing basic jobs as an alternative to basic income. Before getting into the revulsion itself, I want to bring up some more practical objections:

1. Basic jobs don’t help the disabled

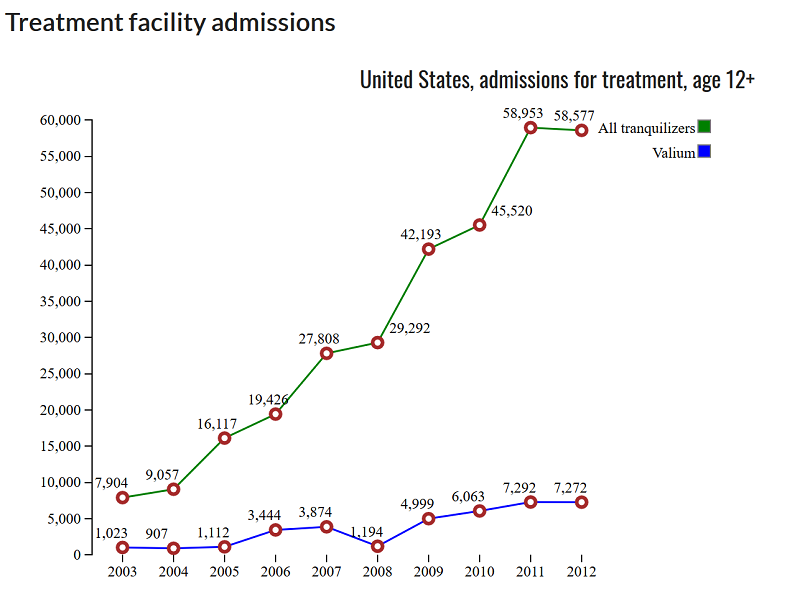

Disability has doubled over the past twenty years and continues to increase.

Experts disagree on how much of the rise in disability reflects deteriorating national health vs. people finding a way to opt out of an increasingly dysfunctional labor market, but everyone expects the the trend to continue. Any program aimed at the non-working poor which focuses on the traditionally unemployed but ignores the disabled is only dealing with the tip of the iceberg.

The current disability system has at least three major problems which I would expect basic income to solve.

First, the disability application process is a mess. Imagine the worst DMV appointment you’ve ever had to obtain the registration to a sketchy old car you got from a friend, then multiply it by a thousand – then imagine you have to do it all while being too disabled to work. Even clear-cut applications can take months to go through, inflicting an immense burden on people who don’t know where their money is coming from during that time. And people with harder-to-prove conditions like mental illness and chronic pain might require multiple appeals – dragging the process out for years – or never get it at all. The disabled people I have talked to generally hate everything about this.

Second, disability is becoming a catch-all for people who can’t find employment. This is a useful function that needs to be served. But right now, it involves unemployed people faking and exaggerating disability. This rewards liars and punishes the honest. If society labels the system “FOR DISABLED PEOPLE ONLY”, basic fairness – to the disabled, to taxpayers, and to honest workers who aren’t gaming the system – require them to gatekeep entry. Right now they spend lots of time and money on gatekeeping and still mostly fail. But any attempt to crack down would exacerbate the first problem, the one where real disabled people have to spend months or years in a Kafka novel before getting recognized.

Third, because of the first and second problems disabled people feel like they constantly have to prove themselves. Sometimes they’ll have good days – lots of conditions are relapsing-remitting – and they’ll want to go play in the park or something. Then they have to worry that some neighbor is going to think “well, that guy looks pretty healthy”, take a photo, and they’ll end up as one of those stories with headlines like SO-CALLED DISABLED PERSON CAUGHT PLAYING SPORTS IN PARK. Other times it’s a bureaucratic issue. I had a patient who, after a few years on disability, recovered enough that he thought he could work about ten hours a week. When he tried to make it happen, he learned he would lose his disability payments – apparently if you can work at all the government doesn’t believe you’re really disabled – and ten hours a week wasn’t enough to support himself. So he cancelled the new job and didn’t work at all.

As long as you have a system whose goal is to separate the “truly” disabled people from the fakers, you’re going to run into problems like these. But refuse to gatekeep, and you have an unjust system where anyone who wants to lie can get out of work while their more honest coworkers are left slaving away all day. Basic income cuts the Gordian knot by proposing that everyone is legally entitled to support, whether they’re disabled or not. Disabled people can get their money without gatekeeping, and there’s no reward for foul play.

Basic jobs abandons this solution and takes us right back to the current system. If you’re abled enough to perform a government job, you’ve got to do it. Who decides if you’re abled enough? The Kafkaesque gatekeepers. And so we get the same bureaucratic despair, the same attempts to cheat the system, and the same perverse incentives.

And the number of disability claims keeps rising. Remember, a lot of economists think that the flight away from work and toward disability comes from people voting with their feet against exactly the kind of low-paying unpleasant jobs that basic jobs advocates want to offer everybody. Expect them to vote against those too, with no clear solutions within the basic jobs paradigm.

2. Basic jobs don’t help caretakers

And another 10% to 15% of the jobless are people caring for their sick family members.

This is unavoidable and currently uncompensated. The AgingCare Caregiver forum says their “number one question” is whether people who need to take time off work to care for a sick or elderly parent can get money. The only answer they can provide is “if the person you’re caring for has money or insurance, maybe they can pay you”. If they don’t, you’re out of luck. [EDIT: apparently some states do offer some money for this].

Right now our society just drops the ball on this problem. I don’t blame it; giving people money to care for family members would be prohibitively expensive. It would also require a gatekeeping bureaucracy that would put the disability gatekeeping bureaucracy to shame. Not only do they have to assess if someone’s really unable to subsist without care, they also have to decide who gets to take the option for which relatives. I have a second cousin some number of times removed who’s very disabled; can I quit my job and get paid a reasonable salary to take care of him? What if I tell you I’ve never met him or even talked to him on the phone, and just have my grandmother’s word for it that he exists and is sick? What exactly counts as caretaking? If I go visit my second cousin once a day for an hour to make sure he hasn’t gotten any sicker than usual, should the government pay me a full salary? What if actually doing that is 100% vital to my second cousin’s continued survival and I wouldn’t be able to do it consistently while holding down a job? You are never going to be able to make a bureaucracy that can address all these issues fairly.

Basic income cuts the knot again, giving everyone enough money that they can take care of sick or aging friends or relatives if they so choose. You don’t have to justify your choice to provide this level of care (but not that level) to the government. You can just do what needs to be done.

Basic jobs once again drops the ball on this problem. If your mother is dying, you can’t be there to help her, because the government is going to make you dig ditches and fill them in again all day to satisfy people’s worry that somebody somewhere might be getting money without doing enough make-work to “deserve” it.

3. Basic jobs don’t help parents

Everything above, except this time you’re a single parent (or a double parent whose spouse also works) and you want to take care of your child. If you could afford daycare, you probably wouldn’t be the sort of person who needs to apply for a guaranteed basic job. What do you do?

I know what the basic jobs people’s solution to this is going to be: free daycare for all! Okay. So in addition to proposing the most expensive government program ever invented, you want to supplement it by passing the second most expensive government program ever invented, at the same time? Good luck.

But even aside from this, I want us to step back and think about what we’re doing. I have met people – mostly mothers, but some fathers too – who are heartbroken at the thought of missing the best years of their children’s lives grinding away at a 9 to 5 job, stuck in traffic commuting to their job, or being too tired to spend time with them after they get home from their job. These people miss their kids’ first steps, outsource watching their first words to underpaid daycare employees, and have to choose between attending their kids’ school plays and putting food on the table.

And if we check the Treasury and decide that we, as a society, don’t have enough money to solve this problem – then whatever, we don’t have enough money to solve this problem.

But I worry we’re going to check and find we have more than enough money. But somebody is going to be so excited about making poor people do busy-work to justify their existence, that we’re going to insist on perpetuating the problem anyway. And if that forces us to pay for universal free daycare, we’re going to be spending extra money just to make sure we can perpetuate the problem as effectively as possible. We’re going to be saying “We could give basic income for $800 billion, or basic jobs plus universal daycare for $900 billion. And that extra $100 billion? That’s the money we spend to make sure you’re digging ditches and filling them in all day, instead of getting to be at home spending time with your kids.”

4. Jobs are actually a big cause of poverty

Poor people’s two largest expenses are housing and transportation.

Guaranteed jobs have to be somewhere. Most of them will be in big cities, because that’s where everybody is. The ones in the country will be few and far between.

That means to get to your government-mandated job, you’ll either need to live in the big city or have a car. Living in the big city means tripling your monthly rent. Having a car means car payments, insurance payments, repair payments, gas payments, and incidentals.

When I first started working with poor patients, I was shocked how many of the problems in their lives were car-related. For well-off people like me, having a car is background noise; you buy or lease it for a reasonable price, then never worry about it again. Poor people can’t afford to buy and don’t always have good enough credit to lease. They tend to get older, sketchier cars that constantly break down. A constant complaint I heard: “My car broke, I can’t afford repairs, and I’m going to get fired if I can’t make it to my job”. Some of them can’t afford insurance and take their chances without it. Others have had various incidents with the police that cost them their license, but they can’t just not show up to work, so they drive anyway and hope they don’t get arrested.

Then there are the little things. Your work doesn’t have a break room, so you’ve got to eat out for lunch, and there goes a big part of your food budget. Your work demands a whole new set of business clothes, so there’s double your clothing budget. You can’t attend things during normal business hours, so you have to pay extra for out-of-hours services.

And then there’s all of the problems above. You can’t take care of your children anymore, so you’ve got to pay for daycare or a nanny or an Uber to take them to their grandparents’ house. You can’t take care of your sick parents anymore, so you’ve got to pay for a home health aide to come in and look after them. You get job-related strain or stress, and there’s the cost of a doctor’s appointment.

And then there are the fuzzier things. If you’ve just spent the entire day at work, and you’re really exhausted, and you never get any time to yourself, maybe you don’t have the energy left to drive to the cheaper supermarket on the other end of town. Maybe you don’t have the time to search for the absolute best deal on the new computer you’re getting. Maybe you don’t have the willpower to resist splurging and giving yourself one nice thing in your life of wage slavery. All of this sounds kind of shameful, but they’re all things that my patients have told me and things that I do myself sometimes despite my perfectly nice well-paying job.

5. Basic jobs may not pay for themselves by doing useful work

I once read an economist discussing why unemployment exists at all. That is, there are always people who would like to have someone clean their house, take care of their children, or come to their house and cook them food. And there are always businesses that would like their floors a little cleaner, or their customers served a little faster, or one more security guard to keep everything safe. Surely they would pay some amount of money to get these jobs done? And surely some homeless person would rather take that small amount than starve on the streets? So why are there still unemployed people?

One answer must be the minimum wage, but how come this happens even in times and places where minimum wages are absent or easy to evade?

The economist suggested that not all employees are net positive. Employees can steal from you, offend your customers, or be generally weird and smelly and ruin the atmosphere. They can be late or not show up at all – and if you made plans depending on their presence, that can be worse than your never hiring them in the first place. A bad nanny can traumatize your kid. A bad maid can break your priceless vase. A litigious employee can take you to court on false charges. Somebody who’s loud and curses at you and constantly smells of marijuana can just make you a little more stressed and unhappy all the time.

So if you have a job that only produces 1 utility, but a bad employee in that job will cost you 10 utility, and there’s a 10% chance any employee you get will be bad – then you’re not going to fill that job no matter how low a salary people are willing to work for.

How bad can employees get? Please read these AskReddit links. They’re slightly off-topic, but they’re going to give you information you can’t get any other way:

— AskReddit: Bosses of Reddit, what was your worst employee like?

— Managers of Reddit, who was your worst employee?

— What is the worst employee you have had to put up with?

— Who’s the worst coworker you ever had?

It’s safe to say they can get pretty bad.

I know many unemployed people who are amazing virtuous hard-working folks. But I also know the unemployed guy who lives in a cardboard box by the BART station, is surrounded by a protective shell of discarded beer cans, and shouts “GRAAAAGH” at passers-by for inscrutable reasons. And the amazing virtuous hard-working folks have a decent shot at getting a job in the private sector eventually, but the guy who shouts “GRAAAAGH” never will. Your population of basic-job-needers is going to be disproportionately composed of people who don’t fit into the regular workforce. How do you think that will turn out?

I worry some people think choosing basic jobs over basic income means free labor. Like, if you were going to pay someone a basic income of $10K/year, but the market value of their labor is $8K/year, you could employ them running a soup kitchen, get that $8K of value, and then you’re really only “losing” $2K/year.

I am less sanguine. If you pay people $10K/year, you’re only losing $10K/year. If you employ them to run a soup kitchen, and the soup kitchen has to keep closing because of hygiene violations, or gets hit with a sexual harassment lawsuit because someone groped a customer, or burns down because someone left the stove on, or loses all its customers because the manager shouts “GRAAAAGH” at everybody who asks for soup – then you’re losing more.

6. Private industry deals with bad workers by firing them; nobody has a good plan for how basic jobs would replace this

Suppose someone does accidentally leave a stove on and burn down the soup kitchen. You transfer them to an agricultural commune and they crash the tractor into a tree. You transfer them to some kind of low-risk paper-pushing job, but they’re late to work every day and skip it entirely once or twice a week, and important papers end up tragically un-pushed. After a while, you decide they are too incompetent to add non-negative value to any of the programs on offer. What do you do with them?

If you fire them, then you’re not a basic jobs guarantee. You’re a basic-jobs-for-skilled-workers-whom-bosses-like guarantee. We already have one of those – it’s called capitalism, maybe you’ve heard of it. But a real solution to poverty would have to encompass everybody, not just people who are good at working within the system.

And if you don’t fire them, what’s your plan? Accept a certain level of burning-things-down, customer complaints, coworker complaints, and unexcused absences? Let them make everybody around them miserable? Turn your soup kitchen into some kind of federal disaster area because you’re absolutely committed to letting every single human being in the United States work there?

Or transfer them to a job in a padded room putting blocks in stacks and knocking them down again, in a way that inconveniences nobody because nobody cares about it? Abandon all pretense at creating anything other than busy-work for poor people out of an all-consuming desire to make sure nobody can live comfortably unless they have spent forty hours of every week in boredom and misery?

Or offer these people a basic income, and let all your other employees hate you for giving incompetent people leisure time at home with their family while the hard workers dig ditches all day?

This isn’t speculation about some vague future. These questions get played out all around the country in our existing “government must take everyone no matter how little they want to be there” institution, ie public school. Here’s a quote from a reader the last time we discussed the public school system.

I was friends with a guy who briefly worked as a teacher at a public high school in central DC (I’m 80% sure it was Cardozo High). He had an education background thanks to spending several years working as a youth camp counselor and as an after-school program counselor, and that was sufficient to qualify him for DCPS’ abbreviated teacher training program (such a thing existed in 2009 when he did it; I’m unsure if it is still around). During the training program, I remember him speaking about his enthusiasm for the teaching skills he was learning and about his eagerness to put them to use (in retrospect, I think some of this was a nervous attempt to convince himself the job wouldn’t be bad). After a break of several months, we spoke again, and he was almost totally disillusioned with the job and was already thinking of quitting. This is what I remember him saying:

1) On the first day of classes, there was no orientation for new teachers, no brief meeting where the Principal shook his hand and said “Welcome Aboard,” nothing. He had to go to the front office and ask a secretary what classroom was his and walk there by himself.

2) Unexcused absences were chronic and undermined his ability to teach anything. At the start of each of his classes, he had a written roster of students, and he had to check off which students were there. For any class, typically 20-30% of students would be missing, without explanation (This is a very important point to remember whenever anyone tries to blame DCPS’ poor outcomes on large class sizes–on paper, each class might have 35 students, but typically, only 23 are actually showing up). Additionally, the 20-30% of students who were absent each class varied from day-to-day, meaning one student didn’t know what was taught on Monday, the one next to him was there Monday but not Tuesday, the third was there the first two days but not Wednesday, etc.

3) Student misbehavior was atrocious. For example, out of the students who showed up to class, it was common for some to walk into the classroom late, again without any explanation and often behaving disruptively. As a rule, whenever a student did that, he was obligated to sign his name on a clipboard for the teacher’s attendance records (there was no punishment for tardiness–late students merely had to write their names down). Some late students would chronically resist doing this, either ignoring him and just going to their desks or yelling curses at him. My friend described an incident where one student–who was physically bigger than he was–yelled out he was a “FAGGOT” when asked to sign the clipboard, provoking laughs from all the other students, before sitting down without signing it. After seeing he could get away with that, the student started calling my friend “FAGGOT” all the time. Other examples of misbehavior included near-constant talking among the students during lessons and fooling around with cell phones.

4) Teachers received almost no support from the school administration. Had sane rules been followed at this high school, students would have been immediately sent to the office for formal punishment for these sorts of offenses I’ve described. However, under such a policy, the office would have been overwhelmed with misbehaving students and probably some of their enraged parents, so the administration solved the problem by forbidding teachers from sending students to the office for anything other than physical violence in the classroom. My friend had no ability to formally punish the student who liked to call him “FAGGOT” other than to use stern verbal warnings.

5) Most of the students were unwilling and in some cases unable to learn. During class sessions, the students were clearly disengaged from what he was teaching. Homework completion rates were abysmal. As the end of the academic semester neared, he saw that a huge fraction of them were on track to fail, so he resorted to pitiful cajoling, pizza parties, reward schemes, and deals involving large curves to everyone’s grades if they could only, for once do a little work, and it didn’t work. Some of his students were Latino and understood little or even no English, meaning they learned (almost) nothing, even when they tried. He resorted to seating the students who knew no English next to bilingual Latinos who could translate for them. That was the best he could do. In fairness, he spoke glowingly of some of his students, who actually put in some effort and were surprisingly smart […]

I’ll never forget how crestfallen and stressed out he was when he described these things to me. Having never taught in American public schools, I didn’t realize just how bad it was, and the detailed nature of his anecdotes really had an impact on me. I advised him to finish his year at the high school and then to transfer to ANY non-urban school in the area, even if it meant lower pay or a longer commute. We lost touch after that, but I can’t imagine he still works in DCPS.

The education system remains popular because they can always hold up glossy posters of smiling upper-class children at Rich Oaks Magnet High School and claim the system works. But basic jobs are going to be selecting primarily from the very poor demographic and they’re going to get hit with the same problem as the poorest public schools – a need for people to behave, combined with inability to credibly disincentivize misbehavior.

Basic income avoids this problem. It provides money to everyone, good employees and bad employees alike, without forcing any workplace to keep people it finds unproductive or threatening, and without having to find humiliating make-work jobs for anybody.

7. Private employees deal with bad workplaces by quitting them; nobody has a good plan for how basic jobs would replace this

And if you think this is a problem for the managers, just wait until you see what the employees have to put up with.

Some bosses are incompetent. Some are greedy. Some are downright abusive. Some don’t have any obvious flaw you can put your finger on, they just turn every single day into a miserable emotional grind. Sometimes the boss is fine, but the coworkers are creeps, or bullies, or don’t do their fair share. Sometimes the boss and the coworkers are both okay, but the job itself just isn’t suited to your personality and what you can manage.

In private industry, people cope by leaving their job and finding a better one. It’s not a perfect system. A lot of people are stuck in jobs they don’t like because they’re not sure they can find another, or because they don’t have enough money to last them through the interim. And this is one reason why poor people who can’t easily change jobs have worse working conditions than wealthier people who can. But everyone at least has the option in principle if their job becomes unbearable.

What about the people who can’t get any jobs besides the guaranteed basic ones? How do they deal with abusive working conditions?

Probably somebody will set up some system to let you quit one basic job and go to a different one in the same city. But probably it will end up being much more complicated than that. How do you deal with the guy who quits every job after a week or two, looking for the perfect cushy position? How do you deal with the case where there’s only one basic job available within a hundred miles? How do you deal with the case where everyone wants the same few really good jobs, and nobody wants to work at the awful abusive soup kitchen down the road?

People will set up systems to solve these problems, and the systems will be unwieldy and ineffective, just like the systems for switching public schools today, and just like all the other clever top-down socialist systems people invent to replace exit rights. Probably they’ll take the edge off some of these problems, but probably nobody will be truly satisfied with the results.

Basic income solves this problem. It doesn’t make anybody stay at a workplace they don’t like.

8. Basic income could fix private industry; basic jobs could destroy it

In my dreams, the government finds a way to provide a basic income at somewhere above subsistence level. The next day, every single person working an awful McJob quits, because there’s no reason to work there except not being able to subsist otherwise.

After that, one of two things happens. First, maybe McDonald’s makes a desperate effort to invent awesome robots that can serve food without human support. Society and Ronald McDonald share a drink together – McDonald’s has managed to remain a profitable company providing a valuable service, and poor people live comfortable lives without having to flip burgers eight hours a day.

Or maybe inventing robots is hard, and McDonald’s has to lure some people back. They raise pay and improve working conditions, until the prospect of working for McDonald’s and getting luxuries is better than the prospect of living off basic income and getting subsistence. Maybe McDonald’s has to raise prices; maybe they even have to close some stores. But again, something like McDonald’s continues to exist and workers are relatively well-off.

A poorly-planned basic jobs guarantee could make the problem worse. Suppose that the government decided to use its free labor to farm cows. This puts various private cow-farming companies out of business; after all, the government can pay its employees out of the welfare budget, but private companies have to pay employees out of revenue. Some of the unemployed cow-farmers go get a guaranteed basic job, putting further private companies out of work. And other unemployed cow-farmers go work at McDonald’s, driving up the supply of McDonald’s employees and so ensuring lower wages and worse conditions.

This isn’t to deny that a well-planned basic jobs guarantee could have the same effect as basic income; if the government jobs were better than McDonald’s’s, McDonald’s might have to raise wages and improve conditions to lure people back. The direction of the effect would depend on how good the government jobs are and how much they compete with private industry. I predict the government jobs will be very bad, and compete with private industry a lot, which makes me expect the effect will be negative.

9. Basic income supports personal development; basic jobs prevent it

I have a friend who was stuck on a dead-end career path. His job paid a decent amount, he just didn’t really like where it was going. So he saved up enough money to live on for a year, spent a year teaching himself coding, applied to a programming job, got it, and felt a lot more comfortable with his financial situation.

And I had a patient in a similar situation. Hated her job, really wanted to leave it, didn’t have enough skills to get anything else. So she went to night school, and – she found she couldn’t do it. After working 8 to 6 every day, her ability to go straight from a long day’s work to a long night’s studying just wasn’t in the cards. And her income didn’t give her the same opportunity to save up some money and take a year off. So she gave up and she still works at the job she hates. The end.

Basic income would give everyone who wants to work the same opportunity as my friend – the ability to take a year off, cultivate yourself, learn stuff, go to school, build your resume – without it being a financial disaster.

Basic jobs would leave everyone in the same position as my patient – forced to work 40+ hours a week, commute however many hours a week, good luck finding time to earn yourself a ticket out of that lifestyle while still staying sane.

There are more creative things you can do with time off work. Entrepreneurs like to talk about “runway” – how long can you keep burning through money before you run out and have to declare your new business a failure? Sometimes your runway is costs like renting an office or paying employees, but for small one-person businesses the question is usually “how long can I continue to live and feed myself working on this not-yet-profitable company?”

And poor people have runway issues of their own. One of the most common reasons poor people end up in crappy jobs is because they don’t have the luxury of a long job search. If your savings will only last you a month before you can’t make rent, you’re going to accept the first job that will take you and feel grateful for it. If you have a guaranteed income source, you can wait until somebody presents you with a better fit.

Basic income is unlimited runway. Entrepreneurs can feel free to try out crazy ideas without the constant pressure of losing their shirt; people in between jobs can feel free to spend time looking for options they can tolerate.

Basic jobs solves none of these problems, and maintains the time pressures that prevent people from exploring interesting ideas or realizing their full potential.

10. Basic income puts everyone on the same side; basic jobs preserve the poor-vs-the-rest-of-us dichotomy

Welfare users often talk about the stigma involved in getting welfare. Either other people make them feel like a parasite, or they just worry about it themselves. Basic jobs would be little different. There will be the well-off people with jobs producing useful goods and services. And there will be the people on guaranteed basic jobs, who know their paychecks are being subsidized by Society. In the worst case scenario, people complaining about workplace abuses at their guaranteed basic job will be told how lucky they are to have work at all.

Basic income breaks through that dichotomy. Everybody, from Warren Buffett to the lowliest beggar on the street, gets the same basic income. We assume Warren Buffett pays enough taxes that the program is a net negative for him, but taxes are complicated and this is hard to notice. Rich people are well aware they contribute more to the system than they get out. But they don’t think of it on the level of “I pay $340 in taxes to support my local police station, but only get $154.50 of police services. Meanwhile, Joe over there pays $80 in police taxes and gets $190 in police services. I hate him so much!”

There will be people on basic income who have no other source of money. There will be people who supplement it with odd jobs now and then. There will be people who work part-time but who plausibly still get more than they pay in taxes. There will be people who work full-time and maybe pay more than they get but aren’t really sure. At no point does a clear dichotomy between “those people getting welfare” and “the rest of us who support them” ever kick in.

11. Work sucks

Amidst all of these very specific complaints, I worry we’re losing site of the bigger picture, which is that work sucks. I have my dream job, the job I’ve been lusting after since I was ten years old, it’s going exactly as well as I expected – but I still Thank God It’s Friday just like everyone else.

And other people have it almost arbitrarily worse. Here are some of the cases you hear about several times a week doing psychiatry:

“I work really long days at my job. I have to deal with angry clients, bosses who don’t appreciate me, and coworkers who try to dump their work on me. By the time I get home after my hour-long commute, I’m too wiped to do anything other than make a microwave dinner and watch TV for an hour or two until I pass out. Then on the weekends I take care of business like grocery shopping, cleaning, and paying my bills. Then Monday comes around and I have to do it all over again. I feel like work drains all my energy and doesn’t leave me any time to be me. I used to play in a band, and we had dreams of making it big, but I had to quit because I don’t feel like I have time for it any more. It’s just work, go home, sleep, repeat.”

“I can’t stand the new open office plan. I feel like I’ve got to do work in the middle of a loud bar where everyone’s trying to talk over each other. Sometimes I hide in the janitorial closet just so I can concentrate for a couple of hours while I finish sometimes important. I’m afraid if anyone ever catches me doing that they’ll say I’m ‘not a team player’ and I’ll get written up, but I just can’t take being crammed together with all those people. Maybe if you gave me some Adderall I could focus better?”

“Sorry I haven’t seen you in a few months. My workplace says it gives time off for doctor’s appointments, but you still get in trouble for missing targets, and I just couldn’t find any time that works. I ran out of my medication a month ago and am having constant panic attacks, so if you could refill that right away it would be nice. And sorry, I need to go now, I’m actually calling you from the bathroom. I wanted to call you from the janitorial closet, but when I went in, there was a woman inside who mumbled something about the open office plan and accused me of distracting her.”

And the people with the worst jobs don’t have good enough time or money to see psychiatrists; I just never meet them. But I understand it gets pretty bad:

Amazon employee here. The post [The Undercover Author Who Discovered Amazon Warehouse Workers Were Peeing In Bottles Tells Us The Culture Was Like A Prison] is pretty spot on. They don’t monitor bathroom breaks, but your individual rate (or production goal) doesn’t account for bathroom breaks. Or let’s say there is a problem like you need two of something and there’s only one left, well you have to put on your “andon”, wait for someone to come “fix” for you, all the while your rate is dropping. The two most common reasons pepole get fired are not hitting rate, and attendance. They don’t really try to help you hit rate, they just fire and replace.

My first week there two pepole collapsed from dehydration. It’s so common place to see someone collapse that nobody is even shocked anymore. You’ll just hear a manager complain that he has to do some report now, while a couple of new pepole try to help the guy (veterans won’t risk helping becuse it drips rate). No sitting allowed, and there’s nowhere to sit anywhere except the break rooms. Before the robots (they call them kivas) pickers would regularly walk 10-15 miles a day, now it’s just stand for 10-12 hours a day.

People complain about the heat all the time but we just get told 80 degrees (Fahrenheit obviously) is a safe working temp. Sometimes they will pull out a thermometer, but even when it hits 85 they just say it’s fine.

There’s been deaths, at least one in my building… Amazon likes to keep it all hush hush. Heard about others, you can find the stories if you search for it, but Amazon does a good job burying it.

Every now and we have an inspection, where stuff like this should be caught and changed. But they just pretty it up. If the people doing the inspection looked at numbers on inspection day vs normal operation, they would see a massive difference… but no fucks given.

The truth is the warehouses operate at a loss most the time, Amazon literally can’t afford to pay the workers decent pay, and can’t afford to not work them to death. The entire business model is dependent on cheap (easily replacable) labor, which is why tier 1s are the bulk of the Amazon work force. My building has like 3-5k workers most the time and around 10-30k on the holiday (what they call peak). Almost all of that is tier 1, most states have 4-7 of these warehouses, and some like Texas and Arizona have tons more.

Next time you order something off Amazon, remember it was put in that box buy a guy sweating his ass off trying to put 100-250 things in a box per hour, for 10 hours a day or he will be fired, making about a dollar more than minimum wage. Might have even been a night shift guy, who goes to work at 630pm and gets off at 5am.

I 100% understand that advocates of basic jobs insist that they’ll be better than that, that they guarantee really good jobs in clean sunny offices where everybody has a smile in their face and is well-paid. I also understand they said the same thing about those DC public schools before throwing huge amounts of money at them. Forget promises; I care about incentives.

Either one of basic jobs or basic income could be potentially the costliest project the US government has ever attempted. Government projects usually end up cash-constrained, and the costliest one ever won’t be the exception. The pressure to cut corners will get overwhelming. It’s hard to cut corners on basic income – either citizens get their checks or they don’t. It’s simple to cut corners on basic jobs. You do it the same way Amazon does – you let working conditions degrade to intolerable levels. What are your workers going to do do? Quit? Neither Amazon nor government-guaranteed basic jobs need to worry about that – both know that their employees have no good alternatives.

Gathering a bunch of disempowered poor people in a place they’re not allowed to opt out of, with budget constraints on the whole enterprise, is basically the perfect recipe for ensuring miserable conditions. I refuse to believe that they will be much better than private industry; the best we can hope for is that they end up no worse. But the conditions in private industry are miserable, even for people with better resources and coping opportunities than basic jobs recipients are likely to have.

I grudgingly forgive capitalism the misery it causes, because it’s the engine that lifts countries out of poverty. It’s a precondition for a free and prosperous society; attempts to overthrow it have so consistently led to poverty, tyranny, or genocide that we no longer believe its proponents’ earnest oaths that this time they’ve got it right. For right now, there’s no good alternative.

But if we have a basic jobs guarantee, it will cause all the same misery, and I won’t forgive it. The flimsy justifications we can think up won’t be up to the task of justifying the vast suffering it will cause. We can’t excuse it as necessary to produce the goods and services we rely on. We can’t excuse it as a necessary condition for political freedom. If a worker asks “why?”, our only answer will be “because Cory Booker thought a basic jobs guarantee would play better among the electorate than basic income, now get back to packing boxes and collapsing from dehydration”. There will be an alternative: a basic income guarantee. We will have rejected it.

I feel like as a quasi-libertarian, I sometimes downplay how awful private industry, capitalism, and the modern workplace are. If so, I apologize. The only possible excuse for defending such a flood of misery is what inevitably happens when people meddle with it. But the price of such morally tenuous greater-good style reasoning is that you need to stay hyper-aware of times when you don’t need to defend the system, when there is a chance to do better without destroying everything. I think basic income is such a chance. And I think basic jobs are a tiny modification to the idea, which destroys its potential and perpetuates all the worst parts of the existing system.

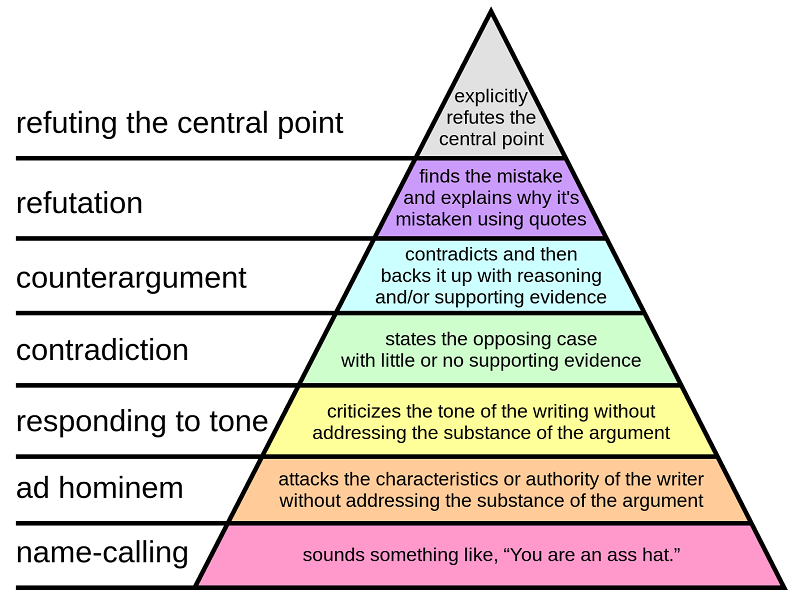

It would be unfair to make this argument without responding to jobs’ proponents points, so I want to explain why I don’t think they provide a strong enough argument against. These will be from the Sarris piece. I don’t want to knock it too much, because it’s a really fair and well-written piece that presents the case for jobs about as well as it can be presented, and any snark I might give it below is totally undeserved and due to personal viciousness. But it argues:

i) Studies of UBI haven’t been very good, so we can’t know if it works.

Studying a UBI pilot with an end date is not studying UBI at all: It is instead studying a misnamed temporary cash payment. By the nature of pilots, the cohort’s behavior cannot reliably change to depend on UBI’s long term existence. No study yet has guaranteed a cohort money forever, and even if it did it would be difficult for a pilot to study the long term effects, some of which may be generations out. What pilot can tell us what its like for kids to grow up with parents who have never worked?[…]

Basic Job programs are more amenable to piloting and a gradual roll-out, since new clusters of jobs appear (and end) all the time. Piloting Basic Jobs can be tried in different communities with varying magnitudes. The legislation to justify such a pilot may already be in place[1], and even a pilot may have lasting benefits. What we learn from the pilot will be more applicable than studying temporary cash transfers in a community and expecting that knowledge to translate into society-wide UBI. If a pilot is successful, one can imagine a kind of National Civil Service, organized like existing federal programs such as the National Park Service, which can hire professionals to train and supervise projects.

I have some minor caveats – Alaska has had a (very small) universal basic income for some time, which seems to have worked relatively well. And basic job studies will also have trouble scaling; smaller trials might preferentially select the most functional unemployed people, would have less impact on private industry, and can always just dismiss people back to the general pool of the unemployed. But overall I agree with the point that basic income is a bigger change and we should be more suspicious of bigger changes.

But at some point you’re arguing against testing something because it’s untested. If we can’t 100% believe the results of small studies – and I agree that we can’t – our two options are to give up and never do anything that hasn’t already been done, or to occasionally take the leap towards larger studies. I think basic income is promising enough that we need to pursue the second. Sarris has already suggested he won’t trust anything that’s less than permanent and widespread, so let’s do an experiment that’s permanent and widespread.

ii) UBI gives everyone the same amount, but some people need more (for example, diabetics need more money to pay for insulin). Existing social programs like medical aid take this into account; UBI wouldn’t.

This seems like exactly the problem that insurance exists to solve. Bringing insurance into the picture, “everybody has to get this” switches from a negative to a positive.

I won’t speculate on how this will look, except to note that it would work well with some kind of mandate where the cost of a Medicare-like state insurance gets auto-deducted from your UBI. Since I’m quasi-libertarian, I would support people’s right to opt out of this, after signing and notarizing a bunch of forms with “I UNDERSTAND I AM AN IDIOT AND MIGHT DIE” on them in big red letters, but I understand other people might prefer to avoid the chance of moral hazard. It still seems like this problem is solvable.

iii) Somehow even if everyone has more money they won’t be better off

One of the biggest assumptions people make with UBI is that the problems of today and the near future are primarily ones of money. I don’t think the data supports this. [link to various charts showing that people generally have food and access to health care]

On some level, if you’re tempted to believe this you should find a poor person and ask them how they feel about being poor. I predict they will say it is bad. They will not agree that our society has basically solved all of its money-related problems. They will say there is a very real sense in which their money-related problems remain unsolved. I guarantee you they will have very strong feelings about this.

But that’s overly pat. A steelman of Sarris’ point might go something like this: it definitely seems true that there is some complicated way in which a family of eight living in a tiny farmhouse in the Kansas prairie in 1870 was happy and felt financially secure even though they probably only earned a few hundred dollars a year by today’s measures. So isn’t it weird that people earning twenty thousand dollars a year still think of material goods as their barrier to happiness?

I think explaining that effectively would require a book-length treatment. But I think the book would end with “even though it’s weird and complicated, poor people today who make $10,000 or $20,000 are often unhappy, in a way that richer people today aren’t, and this involves money in a real sense.”

I am not the person to write this book (though see the post on cost disease); I can only relay what poor people tell me. Sometimes it’s “my rent-controlled apartment is underneath noisy frat boys who keep me awake every night with their parties, but I can never leave because it’s the only apartment I can afford in this town.” Sometimes it’s “I hate my boss but I can’t leave because if I go a month without getting a paycheck I won’t have enough money for rent.” Sometimes it’s “I couldn’t afford good birth control, got pregnant, and now I can’t afford to support the child, what do I do?” Sometimes it’s “Obamacare mandates me to buy health insurance, but I can’t afford it, I guess I am going to have to pay a fee I can’t afford on tax day instead.” Sometimes it’s any of a thousand versions of “my car broke down and I can’t afford to get it fixed but I need to get to work somehow”. Sometimes it’s “I am sick but if I miss a day of work my company will fire me, because when you’re poor enough legally-enshrined workplace protections somehow fail to exist in real life”. And sometimes it’s “I work eighty hours a week driving for Uber because it’s the only way to make ends meet, I hate everything.” A lot of times it involves the same crappy job-centered lifestyle I worry a basic jobs guarantee would perpetuate forever.

Trying to steelman the “it’s not money” point further takes us to Sarris’ other essay on UBI, where he writes:

Rent is currently eating the world. Rental income just hit an all-time high. If everyone is given a very predictable amount of money, it may be seen as a system that can be gamed by landlords and maybe other essentials producers. Implementing UBI without reforming land use and zoning regulations may end up as nothing more than a slow transfer to landlords. What are the odds of that happening? Well, it seems like it already did happen with healthcare and college tuition (loans) in the US, and if those are our guide, the “money” part and the “meaningful reforms” part should be done in a very particular order.

Since housing does work well in some places (Japan and Montreal come to mind) I think this is a problem that can be fixed. But without the fix first, UBI may be punting real political problems while giving the appearance of solving them (until years later), and making the price inflation obvious for landlords, just like it was for healthcare companies and colleges getting guaranteed loans.

Payments as a solution to a broken system is not the same as fixing the system. If UBI punts this real problem, we’ll be creating a financial time bomb.

This is basically how I think about any request for giving more money to education or health care, so I guess I have to take it seriously. Maybe the situations aren’t exactly the same – education and health care seem to eat up money by hiring administrators, which doesn’t have an obvious analogy to ordinary individuals. But the Kansas farmhouse example suggests that something like this must go on even at the personal level.

It looks like probably what’s being described is that – absent some magical ability to create new houses out of thin air (a task known to be beyond the limits of modern technology) – housing is a positional good and so raising the position of everyone equally will just give extra cash to landlords. The best that can be said here is that insofar as these goods aren’t perfectly inelastic, basic income will help a little. And insofar as other goods used by poor people (cars? furniture? generic medications?) are decently elastic, basic income will help a lot. I do agree the problem exists.

But I think this is one case where basic income is clearly better than basic jobs. All basic jobs can do is give you money, which can get eaten by rent-seekers. Basic income gives you freedom. Somebody works 50 hours a week at two McJobs to afford an apartment, gets basic income, and then they work 20 hours a week at one McJob and afford their apartment. The price of an apartment doesn’t change, but their life has improved.

And by lowering the demand for jobs, basic income provides the seed of a solution to the housing problem. The reason rent costs so much in the Bay Area is because everyone wants to live in the Bay Area because it has so many great jobs. You can buy a house in the country (or in an unpopular city) for cheap; people don’t because the jobs aren’t as good, or the good jobs take longer to find. Freed from the need to live right in city center (or right next to the subway stop leading to city center), people can spread out again. If rent is $2000 in San Francisco and $500 in Walnut Creek, they can live in Walnut Creek (and still go to San Francisco whenever they want – cities are very accessible from suburbs, for every purpose except commuting during rush hour five days a week).

Go to the suburbs and people are building new housing tracts all the time. Supply is elastic and everyone’s backyards are so far away from one another that NIMBYs mostly stay quiet. It’s only when our job-centered culture forces everybody into historic San Francisco city center that we start having problems.

There’s still going to have to be a hard battle against cost disease. But much of the cost disease comes from overregulation and creeping socialism, and much of overregulation and creeping socialism come from well-intentioned concerns about the poor. Witness how California’s recent housing bill was opposed by socialists making vague warnings about “greedy developers”. If we can solve the non cost-disease-related parts of poverty first, maybe the socialists will lose some power and we can start fighting the cost disease problem in earnest.

iv) Without work, people will gradually lose meaning from their lives and become miserable

After claiming that money isn’t really a problem for most people, Sarris continues:

The biggest societal ill today is not that people don’t have enough money to survive, it is that to survive and thrive people need things beyond food and rent: Social responsibility, sense of purpose, community, meaningful ways to spend their time, nutrition education, and so on. If we fixate merely on the money aspect, we may be misdiagnosing what is making our 21st century so miserable for so many people.

From some psychologists’ points of view, one of the worst things you can do to someone who is suffering from addiction or loss of hope is to give them no-strings-attached money, when what they really need is regularity and the responsibility that comes from having a purpose, even if its simply a job or a station. Basic Jobs have a chance of making the opioid crisis better, UBI risks making it worse…the at-risk population in the US need functions and responsibility more than just a check.

Social responsibility. Sense of purpose. Community. Meaningful ways to spend your time. This is some big talk for promoting jobs that in real life are probably going to involve a lot of “Do you want fries with that?” Getting a sense of purpose from your job is a crapshoot at best. Getting a sense of purpose outside your job is a natural part of the human condition. The old joke goes that nobody says on their deathbed “I wish I’d spent more time at the office”, but the basic jobs argument seems to worry about exactly that.

And let’s make the hidden step in this argument explicit. Everyone on basic income will have the opportunity to work if they want. In fact, they’ll have more opportunity, since people who hate working will have dropped out of the workforce and demand for labor will rise. So the basic jobs argument isn’t just that people need and enjoy work. The argument is that people need and enjoy work, but also, they are too unaware to realize this, and will never get the work they secretly crave unless we force them into it.

That doesn’t seem right. I don’t know enough hopeless opiate addicts to contradict an apparent psychological consensus on them, but it seems to me a lot of people do perfectly well finding meaning on their own time.

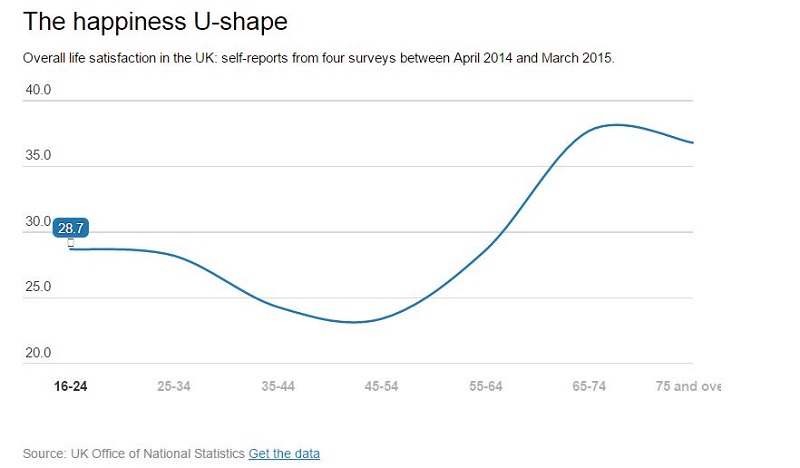

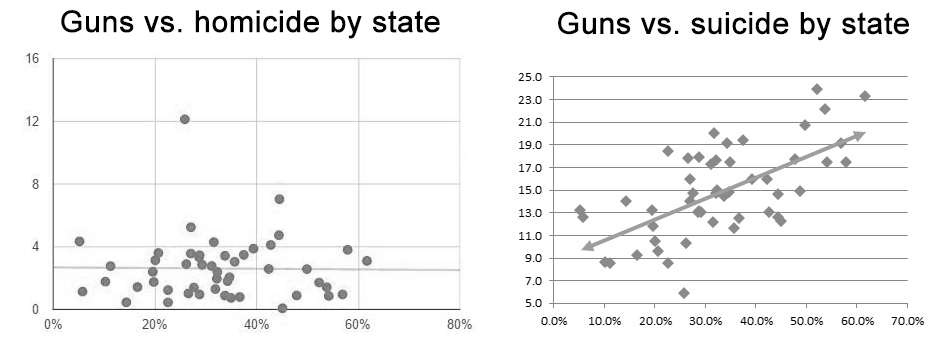

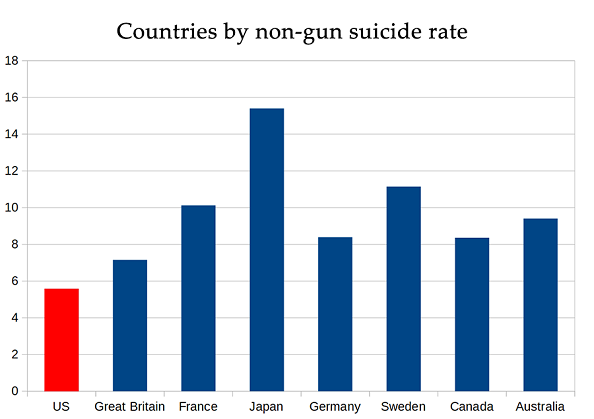

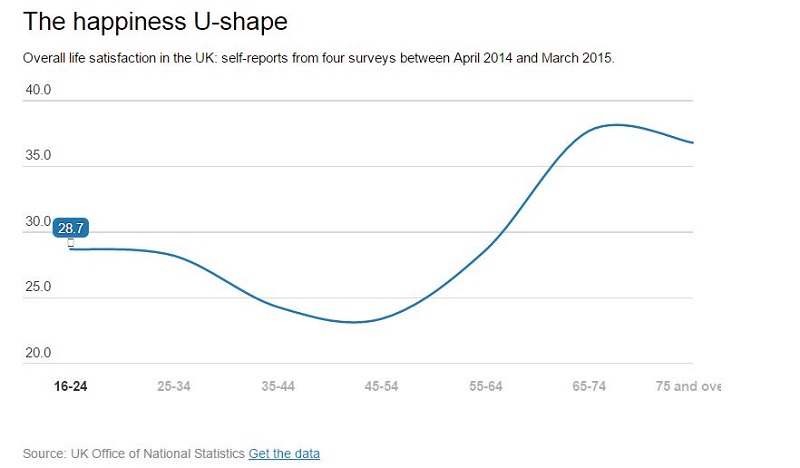

What about the retired? The graph of happiness vs. age looks like this:

This is not the shape we would expect if stopping work suddenly made you miserable and deprived you of purpose. Retired people seem to avoid work just fine and have lots of fun golfing, watching golf tournaments, going on golf vacations, arguing about golf, and whatever else it is retired people do.

Sarris says that “If you think UBI would not make the opioid crisis worse, the onus is on UBI proponents to show how writing ‘UBI’ on the top of the check instead of ‘disability’ would do that.” I would counter-argue that the onus is on opponents to explain why writing ‘UBI’ on the check works so much worse than writing ‘Social Security’.

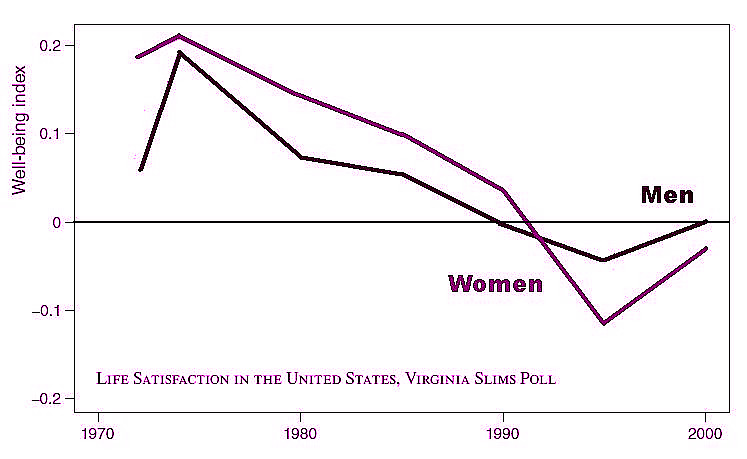

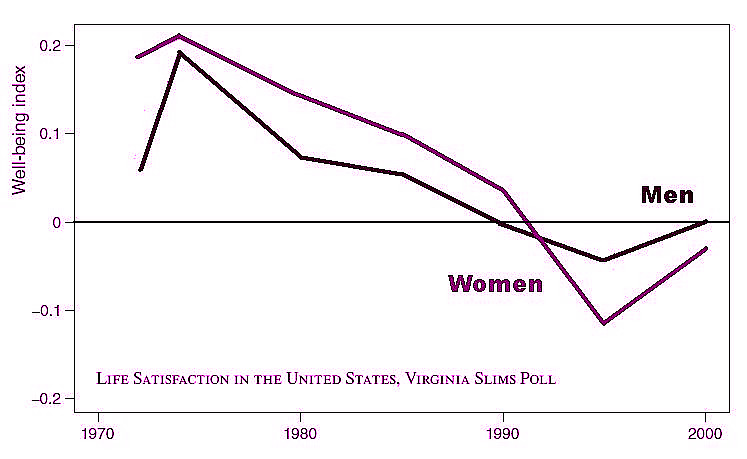

What about homemakers? Yes, homemaker is a full-time job. But it’s the full-time job a lot of people would do if they didn’t have to do their regular full-time job, which makes it fair game when we’re talking about basic income. Here’s a graph of male vs. female happiness over time:

If we assume most women in 1970 were homemakers, and most women in 2000 are working, their shift from homemaking to working doesn’t correspond to any improvement in happiness, either absolutely or relative to men.

There is some debate over whether modern-day homemakers are happier than modern-day workers or vice versa, with the most careful takes usually coming down to “people who prefer to stay home are happier staying home, people who prefer to work are happier working”. But there is no sign of the collapse in meaning and happiness we would expect in homemakers if not having an outside-the-house job reduces you to purposeless nihilism.

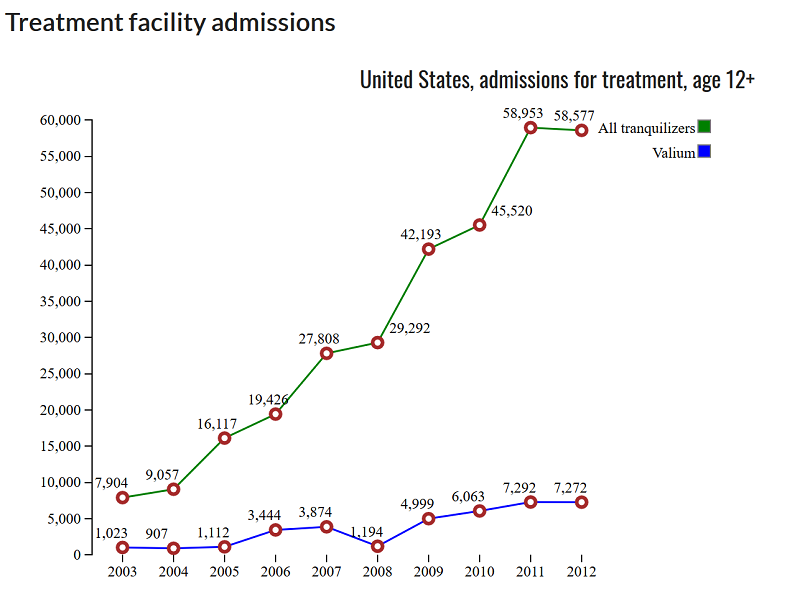

When I bring this up to people, they always have the same objection: “Didn’t women back then use lots of tranquilizers because of how stressed and upset they were? Didn’t they even call Valium ‘Mother’s Little Helper?'” Yes. But take it from a psychiatrist who prescribes them: people still use lots of tranquilizers. Nobody cares anymore, because it’s no longer surprising or ironic.

Sure glad that tranquilizer overuse problem got nipped in the bud in the 1970s when we cancelled stay-at-home parenting.

What about aristocrats? History presents us with many examples of entire classes who managed to live off other people’s work and avoid working themselves. These people seem to have not only have been pretty happy with the deal, but often used their free time to contribute in less purely economic ways. Lord Byron and Warner von Braun were hereditary barons, Bertrand Russell a hereditary earl, de Broglie a hereditary Duke, Condorcet and de Sade hereditary Marquises. Von Neumann’s family was some kind of nouveau riche Austro-Hungarian nobility; Wittgenstein’s family was something similar. Winston Churchill was grandson of a Duke and son of a Lord. None of them ever had to worry about money: society gave them a giant basic income check from their ancestral estates.

Yet Churchill found meaning by saving the UK. Von Braun found meaning by shooting missiles at the UK. Condorcet found meaning by becoming one of the foremost defenders of human rights. De Sade found meaning by becoming one of the foremost violators of human rights. De Broglie and von Neumann found meaning by contributing to fundamental physics. Russell and Wittgenstein found meaning by literally figuring out what meaning was. Overall they seem like a pretty flourishing bunch.

What about college students? Technically they have to go to classes, but a lot of them get away with ten hours or less of class per week, and even more of them just never attend. Some, like Mark Zuckerberg and Bill Gates, use the extra time to found startups. Others, like everyone else, use the extra time to party and take lots of drugs. Either way, they seem pretty happy.

What about the self-employed? Being self-employed costs you a lot of the supposed psychological benefits of work. You might not be leaving the house. You might not be interacting with other people. But studies find that the self-employed are happier than the other-employed, even though they work longer hours and have less job security.

What about hunter-gatherers? Hunting-gathering in a fertile area is a pretty good gig, and usually lets people support themselves with only a few hours’ work per day. Most evidence suggests they’re pretty happy despite their lack of material goods.

What about schoolchildren? Every year, I would complain that I hated school. Every year, my mother would repeat some platitude like “Oh, when summer comes around you’re going to be so bored that you’ll be begging to go back”. And every year, summer vacation would be amazing, and I would love it, and I would hate going back to school with every fiber of my being. I understand this is pretty much a consensus position among schoolchildren. This has left me forever skeptical of arguments of the form “Oh, if you had freedom you would hate it”.

What about me? When I graduated medical school, I applied to residency and was rejected. That left me with a year open before I could try again. Thanks to some odd jobs, a little savings, and charity from friends and family, I was able to subsist. I spent the year meeting new people, hiking around California, falling in love, studying philosophy, and starting this blog. At the end of the year I applied to residency again and was accepted. I’m glad I got the job I wanted, but I also remember that year fondly as maybe the best I’ve ever had, and the one that set the stage for a lot of the good things in my life that happened since. I think this is pretty common for well-off people. We call it a “gap year” or a “sabbatical” or “going off to find yourself” or any of a bunch of other terms that disguise how it’s about doing exactly what people say you can’t do – being happy without a 9 to 5 job.

When I bring these points up, basic jobs advocates usually find reasons to dismiss all of them. Schoolchildren and college students are at a special part of their life that doesn’t generalize. Homemakers like being with their kids. Aristocrats get the world as their oyster. Retirees are mysteriously and permanently mesmerized by golf, which becomes an ur-need subsuming all other human desires. Hunter-gatherers are evolutionarily adapted to their lifestyles. I am just weird. They dismiss all of these as irrelevant and go back to their core example: in the US, right now, unemployed and disabled people are terribly unhappy.

I accept the very many studies that show this, but I do wonder if this has more to do with contingent features of unemployment than with work being necessary to human flourishing. For example, unemployed people are chronically low on money. Unemployed people face stigma and constant social pressure to get employment. Unemployed people live in a society built around and emphasizing jobs. Unemployed people may have pre-existing problems in their lives that led to their unemployment. Unemployed people sometimes suffer from disabilities or chronic pain. Unemployed people have no friends to hang out with during business hours because everyone else is working.

If you compared gay vs. straight happiness in 1980, you probably would have found gay people were much less happy. Now some studies suggest that in liberal and accepting areas, they are as happy or happier. The relative happiness of different groups isn’t necessarily a human universal; it can also depend on how society treats them.

Given all this, I lean in favor of thinking most people would tolerate financially secure leisure time just fine. I might be wrong. But I am still more comfortable letting people decide for themselves. People who try leisure and like it – or who prefer homemaking, or taking care of elderly parents, or anything else – will stay out of the workforce. People who try leisure and don’t like it will apply for the new, better class of jobs that will exist once increased demand for labor has forced employers to up their standards. Or they’ll go volunteer at their church. Or they’ll start a nonprofit. Or they’ll do something ridiculous like try to be the first person to unicycle around the world.

Or maybe the meaninglessness of modern life will start to recede. Why don’t we have strong communities anymore? One reason I keep hearing from my patients is that they had lots of friends and family back home in Illinois or Virginia or wherever – but all the good jobs are in the Bay Area so now they live here and don’t know anybody. My own friends have managed to set up a halfway-decent semi-intentional community in California, but only because by a happy coincidence they all work in computers and all the good computer jobs are in the Bay. Freeing people from needing to orient their entire life around where they can get a job might lead to a lot more intentional communities like mine. Or it might lead to other things we can’t think of right now. A bunch of people with a lot of leisure time to throw at problems, and a bunch of people with money and a problem of meaningless, seems like a pretty good combination if you’re looking for meaning-as-a-service.

The best studies on homemakers find that women who want to be homemakers are happier as homemakers and sadder if forced to work, and women who want to work are happier as workers and sadder if forced to stay at home. I would not be surprised if there are some people who are happiest working, and others who are happiest pursuing leisure activities. A basic income would make it easier for both groups to get what they want.

v) If something went wrong, basic jobs programs could be more gracefully wound down.

What if it doesn’t work? What if we run out of jobs? Suppose a Basic Job program fails 20–30 years into the future. Maybe there’s too much corruption or not enough oversight, or the political will is no longer there, or the money itself is no longer there. Contingency planning is good: No matter how much you trust the pilot, you still want an airplane with emergency exits.

If this happens, the side effects seem less severe (or even mildly positive) when contrasted with a UBI failure. So what if we accidentally fund farms, and bakeries, and furniture production, and house construction, and all sorts of small scale crafts across the country? Even in pessimistic scenarios we can expect some of the businesses and functions built to continue serving their communities after an official program is gone, in the same way that the Hoover dam is still there. A Basic Job program can plan for contingencies and the divvying up of what’s been created, democratically, by community. Sheep farmers that are no longer supported by the government have at least got their flocks. If things ever go south, Basic Jobs better position us to try something else.

“So what if we accidentally fund farms?” asked Stalin, creating the kolkhozes. Maybe I am being mean here, but “let’s guarantee full employment by sticking poor laborers on a government farm somewhere and teaching them to till the earth” is a plan that ought to set off as many historical alarm bells as “let’s do something about all the Jews around here” or “let’s murder the Mongol trade delegation”.

True, nobody is proposing the other prong of socialist agricultural policy, which is crushing the private farms. But it’s important to remember that what’s being proposed is basically socializing large parts of the economy in ways that history tells us lead not only to agricultural catastrophe when being set up, but to economic ruin when being wound down:

In the 1990s, the GDP of Russia declined by 50%. Fifty percent! I don’t know if that’s ever happened before in history outside of a civil war or foreign invasion. The Iraqi economy survived the Iraq War and subsequent sectarian conflict better than the Russian economy survived winding down its basic jobs program.

Maybe I’m being unfair. Socializing part of the economy is probably safer than socializing all of it. And not crushing the private farms really does provide a safety valve that previous collectivization efforts lacked (though if the government farms are more subsidized than they are inefficient, you’ll crush the private farms whether you want to or not).

But I’m still not sure if unsocializing the economy is as easy as winding down a basic income. If you want to wind down a basic income, you decrease it by 5% per year, and each year more people go to work in the private sector or start training to do so. If you want to wind down a nationwide system of collective farms, you – well, empirically you flail about for a while, collapse into a set of breakaway republics, and end up getting ruled by Vladimir Putin.

vi) Basic jobs could be used to create useful infrastructure

Have the imagination to consider all of the work that is not being done, and FDR-style public works programs can be found almost everywhere. Building bicycle lane networks. Creating and maintaining public parks, flowerbeds, sidewalks. Demolition and recycling and re-urbanization (or re-forestation) of derelict factory grounds. There are so many things that would make parts of the US better places to live. As long as swaths of America are in disrepair and also where the jobs aren’t, Basic Jobs has a mission to fulfill.

Some of my concern here comes from my concern (mentioned above) that basic-job-havers would not be very good employees, and that you would probably save money by handing needy people a check and separately hiring some super-efficient megacorporation to make your flowerbeds.

But another part comes from asking myself – which would I rather have? More flowerbeds and sidewalks? Or forty extra hours a week to spend seeing friends and family, or pursuing hobbies that I love? Framed this way, the answer is super-obvious – and remember, I love my job.

vii) Capitalism seems to have historically worked pretty well, and basic jobs guarantees preserve the best features of capitalism

We want to try and keep [the] positive effect of capitalist economic transactions. UBI creates paychecks, Basic Jobs programs do too, but Basic Jobs also create transactions, incentives, and products, fulfilling secondary needs for society.

Basic Jobs can be thought of as a program that is paying people to make other people’s lives better in addition to their own. We are paying people to produce local food and crafts, in a subsidized fashion that gives communities an alternative to the WalMart-esque globalized marketplaces. If the government subsidizes the workers so that their goods can be competitive, it will foster local economies while putting money in the pockets of local worker who themselves have more power. Hopefully, the second-order effects of such commerce are large enough to notice. Maybe the benefits will stay. One could argue that the strong Swiss and other European agricultural subsidies are already a soft form of Basic Jobs.

“Capitalism” is a Rorschach test that means many things to many people. Some people think it means oppression, discrimination, and exploitation. Other people think it means any level of freedom better than you get in Maoist China. Still other people identify it with corporations, or banks, or barter, or any of a thousand other things. But to me, if capitalism means anything at all, it means…

Well, remember argument iv above? About how maybe poor people’s lives will be meaningless without work, and maybe they’re not sufficiently self-aware to realize that on their own, so the government should make them work for their own good, in whatever industry most needs their help?

To me, capitalism means shouting “FUCK YOU” at that argument, at the intuitions behind that argument, and at the whole social structure that makes those intuitions possible, then sterilizing the entire terrain with high-quality low-cost American-made salt so that no other argument like it can ever grow again. There are other parts of capitalism, like the stuff about stock exchanges, but they all flow from that basic urge.

Capitalism certainly doesn’t mean you should never get money without working. Heck, some leftists would define a capitalist as a person who gets money without working. The part where you get money without working is the fun part of capitalism. The thing where most people don’t get that is the part that could do with some fixing. That’s why a lot of history’s greatest capitalists (in both senses of the word) – from Friedrich Hayek and Milton Friedman to Mark Zuckerberg and Elon Musk – have supported basic income.

My intuitions are basically Georgist (note to self: read Henry George before saying this too many more times). Capitalists deserve to keep the value they create, but they also owe rent on common resources which they enclose and monopolize (eg land, raw materials). That rent gets paid to the State (as representative of the people who are denied use of the commons) in the form of taxes. The State then redistributes it to all the people who would otherwise be able to enjoy the monopolized resources – eg everybody. I think this process where businesses pay off the government for their raw materials is pretty similar to the process where they pay off the investors for their seed money, and that the whole thing fits within capitalism pretty nicely.

I don’t think the government taking a big role in the economy for Your Own Good can ever really fit within capitalism, at least not the parts of it that I consider valuable. I would consider a basic jobs guarantee, if it lasted, to be a victory for socialism over the parts of capitalism I hold dear – the final triumph of the old Soviet joke about how “We pretend to work, they pretend to pay us”. If you want an image of the future, imagine a glassy-eyed DMV employee staring at a clock, counting down the hours until she can go home – forever.

And that’s what we’re debating here – an image of the future. These basic guarantees always get brought up in the context of technological unemployment. I’ve looked into this before, and although I don’t think jobs are being destroyed per se, I think it’s definitely possible they’re getting worse for complicated reasons. So as more and more people start getting worse and worse jobs, we can choose one of two paths.

First, we can force more and more people into make-work low-paying government jobs. Extrapolate to the very far future, and 99% of the population will spend their time sending their kids off to daycare before a long day of digging ditches that a machine could have dug better, while 1% of people have amazing robot empires.

Second, we can try to break the link between toiling for someone else and being able to live. We can set some tax rate and promise that all revenue above some amount necessary to fund state functions will be redistributed as basic income. It’ll be pretty puny at first. But as GDP grows, more and more people will opt out of work. As the payments increase, we can gradually transfer various forms of welfare into insurance, and use the gains to grow the payments further. There will be plenty of well-paying jobs for whoever wants to keep working, and lives of leisure and enjoyment for the people who don’t. Robots will pick up the slack and keep the big corporations generating the value that gets siphoned off. Extrapolate to the very far future, and 99% of people live in constantly-improving comfort and freedom, while 1% of people have that plus amazing robot empires.

Both of these are kind of tame shock-level-zero visions. But they set the stage for whatever comes next. If we have genetically enhanced superchildren, or Hansonian em overlords, they’re going to inherit the same social structures that were on the scene when they got here. Whatever institutions we create to contain today’s disadvantaged will one day be used to contain us, when we’re disadvantaged in a much more fundamental way. I want those structures to be as autonomy-promoting as possible, for my own protection.

I grudgingly admit basic jobs would be an improvement over the status quo. But I’m really scared that it becomes so entrenched that we can never move on to anything better. Can anyone honestly look at the DC education system and say “Yeah, I’m glad we designed things that way”? Doesn’t matter; we’re never going to get rid of it; at this point complaining about it too much would send all the wrong tribal signals. Nothing short of a civil war is going to change it in any way beyond giving it more funding. I dread waking up in fifty years and finding the same is true of basic jobs.

This is what I mean by hijacking utopia. Basic income is a real shot at utopia. Basic jobs takes that energy and idealism, and redirects it to perpetuate some of the worst parts of the current system. It’s better than nothing. But not by much.

[EDIT: Sarris’ response, where he argues that I am comparing the most utopian formulation of basic income to a very practical ‘let’s get a few unemployed people back to work’ version of basic jobs.]

Highlights From The Comments On Basic Jobs

These are some of the best comments from Basic Income, Not Basic Jobs: Against Hijacking Utopia. I’m sorry I still haven’t gotten a chance to read everything that people have written about it (in particular I need to look more into Scott Sumner’s take). Sorry to anyone with good comments I left out.

Aevylmar corrects my claim that Milton Friedman supported a basic income:

And Virbie further explains the differences between UBI and negative income tax:

There’s some further debate on the (mostly trivial) advantages of NIT or UBI over the other in the rest of the thread.

Tentor describes Germany’s experience with a basic-jobs-like program:

Another German reader adds:

Murphy describes the UK experience:

Herbert Herbertson on the Native American experience:

Unirt describes the Finnish experience:

richarddormersvoice describes the Chinese experience:

Doktor Relling describes the Scandinavian experience:

Yakimi describes the Nauru experience:

I certainly don’t deny that a lot of ghettos and banlieues contain some very unhappy people. But does work help?

Suppose Alex lives in a ghetto and spends 12 hours a day watching TV and eating Cheetos. Bob lives in the same ghetto, works at a gas station 8 hours a day selling people lotto tickets, then comes home and watches TV and eats Cheetos for 4 hours. Aside from economic arguments about producing value for other people, is Bob’s life more meaningful than Alex’s? Is it happier? Would you rather be Alex or Bob? Would you rather Alex exist, or Bob exist?

If you want to make the argument for work, you have to argue that it does something other than turning Alex into Bob. That it has some other effect, where Bob gets home from work and says “You know, all that lotto-ticket selling has awoken a spark of something higher in me. Instead of watching TV, I think I’m going to read Anna Karenina.” Or something. If I’m strawmanning this argument, it’s because I don’t really know how people expect it to work.

I don’t want to disagree with Yakimi. I don’t want to come out and predict “If we institute UBI, we won’t have ghettos full of Alexes”, and have you point and laugh when I’m proven wrong. I think ghettos full of Alexes is a very likely outcome. But I don’t think that’s worse than ghettos full of Bobs. I think it’s just more surprising, more unfamiliar, more of a man-bites-dog style interesting news story that will provoke concern.

Wrong Species writes:

Yes, this is a good point. Most surveys seem to find job satisfaction is higher in the private sector than the public sector, but I could imagine the opposite being true for the most-exploited kinds of unskilled labor.

And for what it’s worth, here’s a reader who works in an Amazon warehouse commenting to say it’s really not that bad.

Naj on another way things can go wrong:

po8crg suggests:

Simon Sarris (author of the piece I was criticizing) writes:

10240 writes:

This is a good and important point.