[This post was up a few weeks ago before getting taken down for complicated reasons. They have been sorted out and I’m trying again.]

Is scientific progress slowing down? I recently got a chance to attend a conference on this topic, centered around a paper by Bloom, Jones, Reenen & Webb (2018).

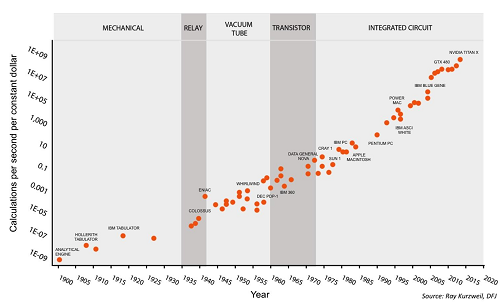

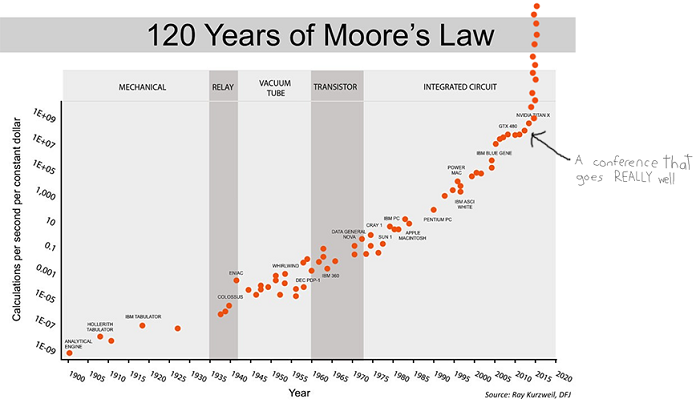

BJRW identify areas where technological progress is easy to measure – for example, the number of transistors on a chip. They measure the rate of progress over the past century or so, and the number of researchers in the field over the same period. For example, here’s the transistor data:

This is the standard presentation of Moore’s Law – the number of transistors you can fit on a chip doubles about every two years (eg grows by 35% per year). This is usually presented as an amazing example of modern science getting things right, and no wonder – it means you can go from a few thousand transistors per chip in 1971 to many million today, with the corresponding increase in computing power.

But BJRW have a pessimistic take. There are eighteen times more people involved in transistor-related research today than in 1971. So if in 1971 it took 1000 scientists to increase transistor density 35% per year, today it takes 18,000 scientists to do the same task. So apparently the average transistor scientist is eighteen times less productive today than fifty years ago. That should be surprising and scary.

But isn’t it unfair to compare percent increase in transistors with absolute increase in transistor scientists? That is, a graph comparing absolute number of transistors per chip vs. absolute number of transistor scientists would show two similar exponential trends. Or a graph comparing percent change in transistors per year vs. percent change in number of transistor scientists per year would show two similar linear trends. Either way, there would be no problem and productivity would appear constant since 1971. Isn’t that a better way to do things?

A lot of people asked paper author Michael Webb this at the conference, and his answer was no. He thinks that intuitively, each “discovery” should decrease transistor size by a certain amount. For example, if you discover a new material that allows transistors to be 5% smaller along one dimension, then you can fit 5% more transistors on your chip whether there were a hundred there before or a million. Since the relevant factor is discoveries per researcher, and each discovery is represented as a percent change in transistor size, it makes sense to compare percent change in transistor size with absolute number of researchers.

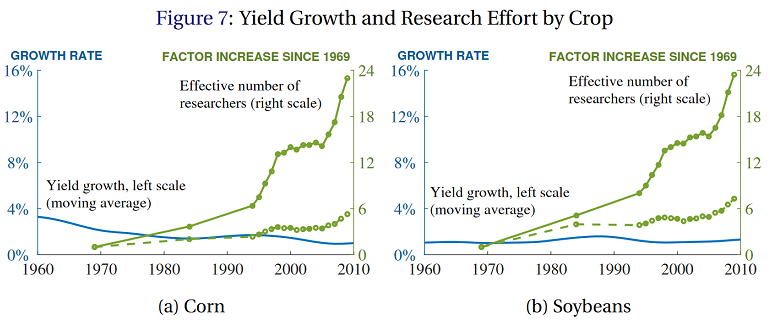

Anyway, most other measurable fields show the same pattern of constant progress in the face of exponentially increasing number of researchers. Here’s BJRW’s data on crop yield:

The solid and dashed lines are two different measures of crop-related research. Even though the crop-related research increases by a factor of 6-24x (depending on how it’s measured), crop yields grow at a relatively constant 1% rate for soybeans, and apparently declining 3%ish percent rate for corn.

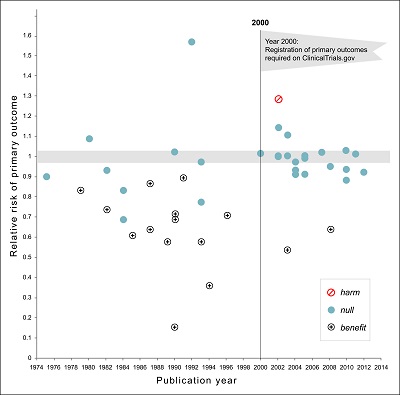

BJRW go on to prove the same is true for whatever other scientific fields they care to measure. Measuring scientific progress is inherently difficult, but their finding of constant or log-constant progress in most areas accords with Nintil’s overview of the same topic, which gives us graphs like

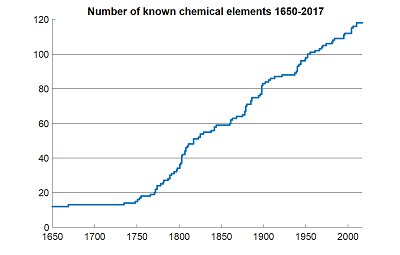

…and dozens more like it. And even when we use data that are easy to measure and hard to fake, like number of chemical elements discovered, we get the same linearity:

Meanwhile, the increase in researchers is obvious. Not only is the population increasing (by a factor of about 2.5x in the US since 1930), but the percent of people with college degrees has quintupled over the same period. The exact numbers differ from field to field, but orders of magnitude increases are the norm. For example, the number of people publishing astronomy papers seems to have dectupled over the past fifty years or so.

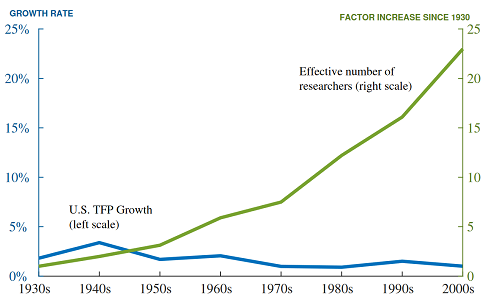

BJRW put all of this together into total number of researchers vs. total factor productivity of the economy, and find…

…about the same as with transistors, soybeans, and everything else. So if you take their methodology seriously, over the past ninety years, each researcher has become about 25x less productive in making discoveries that translate into economic growth.

Participants at the conference had some explanations for this, of which the ones I remember best are:

1. Only the best researchers in a field actually make progress, and the best researchers are already in a field, and probably couldn’t be kept out of the field with barbed wire and attack dogs. If you expand a field, you will get a bunch of merely competent careerists who treat it as a 9-to-5 job. A field of 5 truly inspired geniuses and 5 competent careerists will make X progress. A field of 5 truly inspired geniuses and 500,000 competent careerists will make the same X progress. Adding further competent careerists is useless for doing anything except making graphs look more exponential, and we should stop doing it. See also Price’s Law Of Scientific Contributions.

2. Certain features of the modern academic system, like underpaid PhDs, interminably long postdocs, endless grant-writing drudgery, and clueless funders have lowered productivity. The 1930s academic system was indeed 25x more effective at getting researchers to actually do good research.

3. All the low-hanging fruit has already been picked. For example, element 117 was discovered by an international collaboration who got an unstable isotope of berkelium from the single accelerator in Tennessee capable of synthesizing it, shipped it to a nuclear reactor in Russia where it was attached to a titanium film, brought it to a particle accelerator in a different Russian city where it was bombarded with a custom-made exotic isotope of calcium, sent the resulting data to a global team of theorists, and eventually found a signature indicating that element 117 had existed for a few milliseconds. Meanwhile, the first modern element discovery, that of phosphorous in the 1670s, came from a guy looking at his own piss. We should not be surprised that discovering element 117 needed more people than discovering phosphorous.

Needless to say, my sympathies lean towards explanation number 3. But I worry even this isn’t dismissive enough. My real objection is that constant progress in science in response to exponential increases in inputs ought to be our null hypothesis, and that it’s almost inconceivable that it could ever be otherwise.

Consider a case in which we extend these graphs back to the beginning of a field. For example, psychology started with Wilhelm Wundt and a few of his friends playing around with stimulus perception. Let’s say there were ten of them working for one generation, and they discovered ten revolutionary insights worthy of their own page in Intro Psychology textbooks. Okay. But now there are about a hundred thousand experimental psychologists. Should we expect them to discover a hundred thousand revolutionary insights per generation?

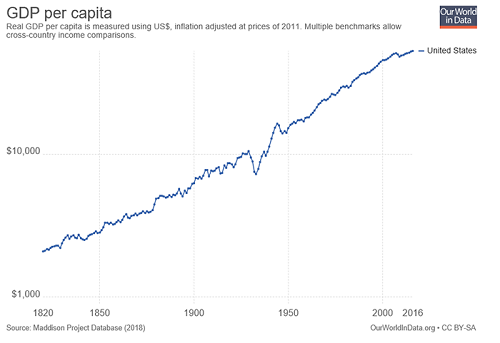

Or: the economic growth rate in 1930 was 2% or so. If it scaled with number of researchers, it ought to be about 50% per year today with our 25x increase in researcher number. That kind of growth would mean that the average person who made $30,000 a year in 2000 should make $50 million a year in 2018.

Or: in 1930, life expectancy at 65 was increasing by about two years per decade. But if that scaled with number of biomedicine researchers, that should have increased to ten years per decade by about 1955, which would mean everyone would have become immortal starting sometime during the Baby Boom, and we would currently be ruled by a deathless God-Emperor Eisenhower.

Or: the ancient Greek world had about 1% the population of the current Western world, so if the average Greek was only 10% as likely to be a scientist as the average modern, there were only 1/1000th as many Greek scientists as modern ones. But the Greeks made such great discoveries as the size of the Earth, the distance of the Earth to the sun, the prediction of eclipses, the heliocentric theory, Euclid’s geometry, the nervous system, the cardiovascular system, etc, and brought technology up from the Bronze Age to the Antikythera mechanism. Even adjusting for the long time scale to which “ancient Greece” refers, are we sure that we’re producing 1000x as many great discoveries as they are? If we extended BJRW’s graph all the way back to Ancient Greece, adjusting for the change in researchers as civilizations rise and fall, wouldn’t it keep the same shape as does for this century? Isn’t the real question not “Why isn’t Dwight Eisenhower immortal god-emperor of Earth?” but “Why isn’t Marcus Aurelius immortal god-emperor of Earth?”

Or: what about human excellence in other fields? Shakespearean England had 1% of the population of the modern Anglosphere, and presumably even fewer than 1% of the artists. Yet it gave us Shakespeare. Are there a hundred Shakespeare-equivalents around today? This is a harder problem than it seems – Shakespeare has become so venerable with historical hindsight that maybe nobody would acknowledge a Shakespeare-level master today even if they existed – but still, a hundred Shakespeares? If we look at some measure of great works of art per era, we find past eras giving us far more than we would predict from their population relative to our own. This is very hard to judge, and I would hate to be the guy who has to decide whether Harry Potter is better or worse than the Aeneid. But still? A hundred Shakespeares?

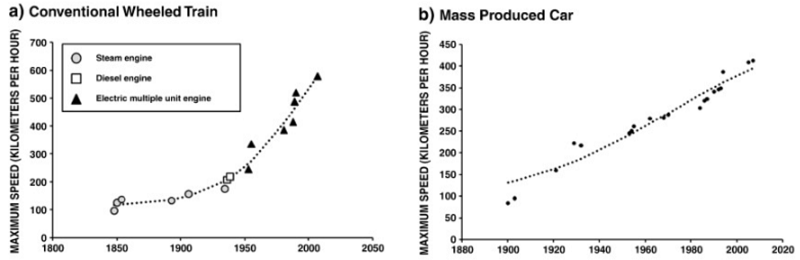

Or: what about sports? Here’s marathon records for the past hundred years or so:

In 1900, there were only two local marathons (eg the Boston Marathon) in the world. Today there are over 800. Also, the world population has increased by a factor of five (more than that in the East African countries that give us literally 100% of top male marathoners). Despite that, progress in marathon records has been steady or declining. Most other Olympics sports show the same pattern.

All of these lines of evidence lead me to the same conclusion: constant growth rates in response to exponentially increasing inputs is the null hypothesis. If it wasn’t, we should be expecting 50% year-on-year GDP growth, easily-discovered-immortality, and the like. Nobody expected that before reading BJRW, so we shouldn’t be surprised when BJRW provide a data-driven model showing it isn’t happening. I realize this in itself isn’t an explanation; it doesn’t tell us why researchers can’t maintain a constant level of output as measured in discoveries. It sounds a little like “God wouldn’t design the universe that way”, which is a kind of suspicious line of argument, especially for atheists. But it at least shifts us from a lens where we view the problem as “What three tweaks should we make to the graduate education system to fix this problem right now?” to one where we view it as “Why isn’t Marcus Aurelius immortal?”

And through such a lens, only the “low-hanging fruits” explanation makes sense. Explanation 1 – that progress depends only on a few geniuses – isn’t enough. After all, the Greece-today difference is partly based on population growth, and population growth should have produced proportionately more geniuses. Explanation 2 – that PhD programs have gotten worse – isn’t enough. There would have to be a worldwide monotonic decline in every field (including sports and art) from Athens to the present day. Only Explanation 3 holds water.

I brought this up at the conference, and somebody reasonably objected – doesn’t that mean science will stagnate soon? After all, we can’t keep feeding it an exponentially increasing number of researchers forever. If nothing else stops us, then at some point, 100% (or the highest plausible amount) of the human population will be researchers, we can only increase as fast as population growth, and then the scientific enterprise collapses.

I answered that the Gods Of Straight Lines are more powerful than the Gods Of The Copybook Headings, so if you try to use common sense on this problem you will fail.

Imagine being a futurist in 1970 presented with Moore’s Law. You scoff: “If this were to continue only 20 more years, it would mean a million transistors on a single chip! You would be able to fit an entire supercomputer in a shoebox!” But common sense was wrong and the trendline was right.

“If this were to continue only 40 more years, it would mean ten billion transistors per chip! You would need more transistors on a single chip than there are humans in the world! You could have computers more powerful than any today, that are too small to even see with the naked eye! You would have transistors with like a double-digit number of atoms!” But common sense was wrong and the trendline was right.

Or imagine being a futurist in ancient Greece presented with world GDP doubling time. Take the trend seriously, and in two thousand years, the future would be fifty thousand times richer. Every man would live better than the Shah of Persia! There would have to be so many people in the world you would need to tile entire countries with cityscape, or build structures higher than the hills just to house all of them. Just to sustain itself, the world would need transportation networks orders of magnitude faster than the fastest horse. But common sense was wrong and the trendline was right.

I’m not saying that no trendline has ever changed. Moore’s Law seems to be legitimately slowing down these days. The Dark Ages shifted every macrohistorical indicator for the worse, and the Industrial Revolution shifted every macrohistorical indicator for the better. Any of these sorts of things could happen again, easily. I’m just saying that “Oh, that exponential trend can’t possibly continue” has a really bad track record. I do not understand the Gods Of Straight Lines, and honestly they creep me out. But I would not want to bet against them.

Grace et al’s survey of AI researchers show they predict that AIs will start being able to do science in about thirty years, and will exceed the productivity of human researchers in every field shortly afterwards. Suddenly “there aren’t enough humans in the entire world to do the amount of research necessary to continue this trend line” stops sounding so compelling.

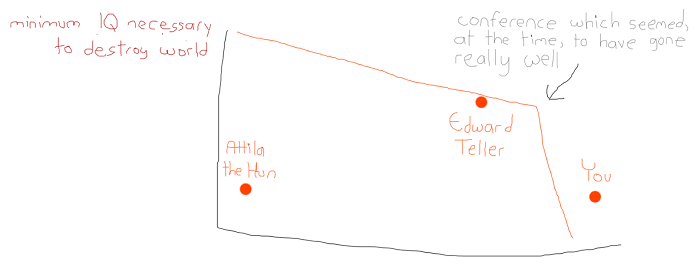

At the end of the conference, the moderator asked how many people thought that it was possible for a concerted effort by ourselves and our institutions to “fix” the “problem” indicated by BJRW’s trends. Almost the entire room raised their hands. Everyone there was smarter and more prestigious than I was (also richer, and in many cases way more attractive), but with all due respect I worry they are insane. This is kind of how I imagine their worldview looking:

I realize I’m being fatalistic here. Doesn’t my position imply that the scientists at Intel should give up and let the Gods Of Straight Lines do the work? Or at least that the head of the National Academy of Sciences should do something like that? That Francis Bacon was wasting his time by inventing the scientific method, and Fred Terman was wasting his time by organizing Silicon Valley? Or perhaps that the Gods Of Straight Lines were acting through Bacon and Terman, and they had no choice in their actions? How do we know that the Gods aren’t acting through our conference? Or that our studying these things isn’t the only thing that keeps the straight lines going?

I don’t know. I can think of some interesting models – one made up of a thousand random coin flips a year has some nice qualities – but I don’t know.

I do know you should be careful what you wish for. If you “solved” this “problem” in classical Athens, Attila the Hun would have had nukes. Remember Yudkowsky’s Law of Mad Science: “Every eighteen months, the minimum IQ necessary to destroy the world drops by one point.” Do you really want to make that number ten points? A hundred? I am kind of okay with the function mapping number of researchers to output that we have right now, thank you very much.

The conference was organized by Patrick Collison and Michael Nielsen; they have written up some of their thoughts here.