These are my preliminary choices for California elected positions and ballot initiatives. Some of them are based on Ozy’s recommendations and the Berkeley EA and rationalist community’s recommendations. I agree with the latter’s note that because California ballot propositions are weird superlaws that permanently overrule the legislature unless repealed by voters, in general we should be very cautious about them (though some of them were recommended by the legislature itself, since for complicated reasons it needs voter support to do certain things).

I’m giving first-level justifications for my votes (ie “I support this person because she wants higher taxes”) but not always second-level justifications (“here’s why higher taxes are good”). You can usually find discussion of these on other blog posts.

Governor of California is the big one. Democrat Gavin Newsom is a former successful businessman, mayor of San Francisco, and lieutenant governor of California (also second cousin of musician Joanna Newsom). He has stated that if elected, he will let people call him “the Gavinator”. Republican John Cox is a former successful businessman, best known for sponsoring a ballot initiative to make legislators wear the logos of their top 10 donors on the State Assembly floor, “much like NASCAR drivers”. He also has a fascinating plan to reform politics from the ground up with a 12,000 (!) member legislature. I don’t really like Newsom – he led a movement called “Care Not Cash” to restrict giving money to the homeless, and supposedly opposed anti-gay Proposition 8 so incompetently that his statements may have increased support for the measure. He also had an affair with his campaign manager’s wife in a scandal that seemed unusually scummy even for a politician. I like John Cox as a person, but he doesn’t seem to have any relevant governing experience. And he was anti-Trump until Trump became popular among Republicans, then about-faced and decided Trump was his new best friend, and now he’s basically just a Trumpist. I am going with Newsom; God help me, God help California.

The Lieutenant Governor is a sinecure interesting only insofar as its holders often become governors themselves, kind of like the US Vice President. Democrat Ed Hernandez is a optometrist who is very involved in health policy. He makes a big deal about Fighting Pharma Companies, and a somewhat less big deal about having taken hundreds of thousands of dollars from pharma companies and hundreds of thousands more from insurance. His opponent Eleni Kounalakis is also a Democrat, because California, and was previously Obama’s ambassador to Hungary. I am not sure exactly what an ambassador does, but if part of her job was to keep a watch on Hungary I feel like this is a strike against her. On the other hand, she has been exposed to superior Habsburg institutions. And she and her husband fund Hellenic Studies at state universities, raising the prospect that maybe she will transform California into some kind of Hellenic-Habsburg fusion superstate. More seriously, Hernandez has done some really good work in health care, including better drug transparency and easier prior auths (non-doctors will not understand this term; doctors will hear it and rush to vote for him immediately). But he seems anti-Medicare-for-all, and kind of in the pocket of insurance companies. He also has been a big proponent of race-based admissions in California colleges. Kounalakis is pro-Medicare-for-all, has Obama’s endorsement, and is really strong on housing policy. Advantage Kounalakis.

The State Controller was an important position back in the time of Mustapha Mond, but nowadays it just audits finances. Betty Yee is the incumbent, and California’s finances have been doing surprisingly well lately, and she sounds very smart and says the right things about preparing for inevitable downturns and promoting fiscal responsibility. Konstantinos Roditis is running mostly on fighting the gas tax and defunding high-speed rail. While high-speed rail will inevitably be a boondoggle that we gnash our teeth over for decades to come, I’m concerned about his obsession with cutting taxes, the gas tax seems like a particularly bad tax to make a stand over, and I’m concerned about replacing a highly competent person who’s kept us solvent with a random low-tax crusader. Advantage Yee.

The State Board of Equalization was an important position back in the time of Harrison Bergeron, but nowadays it just assesses certain taxes. Democrat Malia Cohen boasts that she is strong on climate change, which is relevant because the Board handles gas taxes; she also boasts that she is strong on LGBTQ and abortion rights, which is relevant because California. Republican Mark Burns is centering his whole campaign around strengthening Prop 13, one of the worst laws in California. Both candidates’ names sound like minor Unsong characters, but I choose Malia, no contest.

The Secretary of State handles elections and voter registration. Republican candidate Mark Meuser takes the typical Republican position that we need to tighten standards to fight voter fraud. Democratic candidate Alex Padilla takes the typical Democratic position that there is no such thing as voter fraud and worrying about it is discriminatory. Mark Meuser protests that there is absolutely voter fraud, and highlights how a California man successfully registered his dog to vote. Alex Padilla says that not wanting dogs to vote is discriminatory, and he will order all poll workers to accept wet, slightly-chewed-up ballots. Mark Meuser protests that the man who registered his dog to vote had registered his other dog to vote twenty years earlier and still nobody has taken any action. Alex Padilla boasts of endorsements from some of California’s top politicians, like Mayor Max of Idyllwild. I respect Mr. Meuser’s strong anti-dog stance, but I am concerned, based on his name, that he may secretly be a cat. Advantage Padilla.

The State Treasurer helps manage investments and finances. Republican Greg Conlon is a former accountant who is running on a platform of pointing out that the pension crisis is a giant ticking time bomb that is about to explode and consume us all. Democrat Fiona Ma is running on a platform of investing in shiny popular causes that make us feel good about ourselves, and covering the time-bomb with a pile of leaves so its ominous ticking noises don’t keep us up at night. Advantage Conlon

The Attorney General leads a vast army of attorneys into battle against the attorneys of foreign lands. Democrat Xavier Becerra is the incumbent, and has an unblemished record of taking the most liberal possible position on everything. Republican Steven Bailey is a judge who is Strong On Crime and Very Tough, and so serious that he can call the lawsuit over Trump’s wall “borderline frivolous” without adding even so much as a “pun not intended”. While neither candidate really talks much about mass incarceration, it’s pretty clear that Bailey gets an erection every time he thinks about it, and Becerra plans to ignore it while demonstrating conspicuous outrage about Trump’s latest tweet. Advantage Becerra, I guess.

Reason calls the Insurance Commissioner race The Most Important Election You’ve Never Heard About. Apparently California has a system where a Commissioner has to approve all new insurance products. The Commissioner sometimes uses this power in weird ways – for example, one official refused to approve insurances’ plans unless they divested from investments in coal. Steve Poizner is a Bay Area tech entrepreneur and used to be a Republican but has since switched to being an independent – if he wins, he will be the first independent elected to a major position. Ricardo Lara is “one of the [state] Senate’s most liberal members” and running as a Democrat. I don’t have the background to judge the technicalities of insurance policy. But Poizer is a former incumbent who by all accounts did pretty well, and I think it’s great that a non-partisan person might win a major position. Advantage Poizner.

Everyone dislikes Dianne Feinstein for a different reason. Some people dislike her support for the Iraq War and the Drug War. Other people dislike her attempted constitutional amendment to ban flag burning. Other people dislike her support for the PATRIOT Act, mass surveillance, prosecuting Edward Snowden, and banning strong encryption. Other people dislike her opposition to single-payer healthcare. Other people dislike her support of arms sales to Saudi Arabia. Other people dislike her consistently bad positions on free speech, from supporting universities turning away conservative speakers, to supporting universities’ right to expel students who criticize Israel, to sponsoring an act that classifies various nonviolent forms of animal activism as potential ecoterrorism. I hear some people are Republicans, and have an entirely different set of reasons to dislike her. In these divided times, there isn’t much that can make people step across the aisle and shake hands with people on the other side of hot-button issues – but all of us – rich and poor, white and black, urban and rural – can get behind disliking Dianne Feinstein. I have no real opinion on the other Democrat, Kevin De Leon, so I’m voting for him.

For House of Representatives, it’s the Democratic candidate vs. the Green Party candidate, because California. The Green Party candidate, Laura Wells, looks pretty great – she seems like a smart person who helped institute Instant Runoff Voting in Oakland, giving the city one of the few sane voting systems in the US. Barbara Lee is not nearly as awesome, but she did cast the only vote against authorizing military force in the War on Terror in Congress. This is a sufficiently impressive act that I will vote for her anyway even though I think she is worse on a lot of other things; I would rather reward Congresspeople for taking high-variance unpopular stands that turn out to be right than get someone who will be a 5% better technocrat. Sorry, Laura. If you run for something else later I will support you for that.

There’s also a race for “15th District”, which sounds like one of those groups that sends people to the Hunger Games. This is Buffy Wicks vs. Jovanka Beckles. Beckles is a socialist who is running on the presumption that restricting housing supply will make it more affordable, and on accusing everyone else of being corporate profit establishment capitalist shills. Wicks is endorsed by Barack Obama and East Bay for All, and supports building more housing. I also support her vampire-slaying work (I’m not just going off her name – she even looks similar). Advantage Wicks.

There are ten judges up for re-election. Most sources recommend that people vote ‘yes’ for all of them to preserve judicial independence, so I did that.

The State Superintendent of Public Instruction runs the education system. For an enforced non-partisan office, this race is pretty heated. It has $50 million in spending, and when I Google either candidate’s name I get attack ads trying to tell me why not to vote for him. Both candidates support increased funding and universal pre-K, because California. Marshall Tuck seems a little more pro-charter school, and is against a move where money that was earmarked for high-needs students was instead used to raise teachers’ salaries. Thurmond has the support of teachers’ unions, which I guess makes sense considering. I am usually pro-charter-school and pro-supporting-high-needs-students, but Thurmond supports later start times for middle and high school, and this is pretty important to me. But Tuck has more experience and the support of Obama’s education secretary, so I guess I’ll go with him.

Proposition 1 authorizes bonds to fund affordable housing. The California legislature requested this, newspapers unanimously support it, and affordable housing seems good. Yes.

Proposition 2 authorizes redirecting money earmarked for mental health care to housing mentally ill people. The legislature supports it, housing the mentally ill is probably better for them than whatever else this money was going to do, and I generally support giving the government more flexibility on how to spend its money. Yes.

Proposition 3 authorizes bonds to fund water supply projects. The legislature did not request this. Environmental groups are skeptical. It is sponsored by companies that would benefit from it. Newspapers are unanimously opposed. No.

Proposition 4 authorizes bonds to build children’s hospitals. The legislature did not request this. There are always propositions to fund children’s hospitals and it seems kind of unfair since you’re not allowed to be against healthy children. There is no real evidence of a children’s health crisis. No.

Proposition 5 expands a previous proposition that says people’s taxes on their house cannot increase too quickly while they live in it. This created a problem: imagine that you are a 70 year old whose children have moved away and whose spouse has died. You live in the big five-bedroom house you raised your family in forty years ago, but you want to move somewhere smaller and closer to caregivers and more accessible given whatever health problems you might have. Since buying a new house resets your property taxes, instead of having your taxes pegged to what your current house cost forty years ago, you would have to pay the value of your new house today. This would mean order-of-magnitude-increases in taxes. So you just never move, and keep occupying a five-bedroom house as a single person, whether you like the house or not. To solve this problem, the 1980s measure Proposition 60 allowed elderly homeowners move once, to a smaller house, in the same county, and keep their previous property tax assessment. The current Proposition 5 would say they can move as many times as they want, to any sized house, in any county, and keep their tax assessment. It also extends this to disabled homeowners, who might also need a one-story house or house with more accommodations after they become disabled, and who might also be financially unable to manage the move if it would raise their property taxes. Overall I agree with the idea that taxes should not distort the market and force you to live in a house that is too big for you or doesn’t accommodate your disability; given that there is a housing crisis, forcing people to live in houses that are too big for them seems especially stupid. The California Chamber of Commerce also agrees and says this would free up 100,000 additional houses a year to help ease the housing crisis. However, all my friends, including the ones who are supposedly YIMBY, are very angry about this. I am having difficulty figuring out why in between all the use of “I’ve got mine” and “this is about hating poor people”, but I think it has something to do with anger at the idea that some people can keep their property taxes low forever. I agree this is bad, but it is the existing system; this new proposition just stops favoring people who keep their current home over people who, for reasons of age or disability, have to move houses. I understand anger about low property taxes, but making it harder for older or disabled people to move into houses that meet their needs feels like a particularly cold-hearted way of expressing that. It sounds like the main area of disagreement is whether, if this proposition fails, elderly and disabled people will move anyway but pay higher taxes, or whether they will just stay around to avoid the tax increase. Studies suggest that the lock-in effect from Proposition 13 is real, but don’t let me compare it to anything else or say how much of it has stuck around after Proposition 60. Since this is a matter of comparing coefficients, and I don’t know the coefficients, I am tempted to just look at endorsements. Bloomberg seems in favor, Reason seems ambivalent, and YIMBY Action says no. I think the amount of time it would take for me to feel comfortable with my opinion on this is higher than any possible benefit of getting it right, so I will abstain.

Proposition 6 repeals the gas tax. The gas tax is a reasonable way to internalize the cost of road infrastructure to drivers. It also helps fight climate change and raises much-needed funds for the state. While it is regressive compared to an optimal tax policy, it’s probably better than whatever else would replace it. No.

Proposition 7 allows the legislature to change Daylight Savings Time in ways consistent with federal law. It’s necessary because there was a previous ballot proposition about Daylight Savings Time, and now the legislature can’t change it without another ballot proposition. There is actually some evidence that Daylight Savings Time transitions cause car accidents and interfere with circadian rhythms. There’s also the status quo bias – if we didn’t already have a rule that we switched time by an hour in the spring and autumn, would anyone be proposing it? I’m open to arguments that Daylight Savings transitions might be useful somehow, but I don’t want them as a superlaw that the legislature can never change. Yes.

Proposition 8 says dialysis companies can only charge 115% of the cost of treatment (the extra 15% would presumably be split among administrative expenses and profits). I tend to err on the side of not increasing the massive overregulation of health care. Even if I didn’t, I would like the California legislature to be able to decide whether to regulate health care or not, rather than pass it as a superlaw that can never be repealed no matter how badly it goes. No.

There is no Proposition 9, because California.

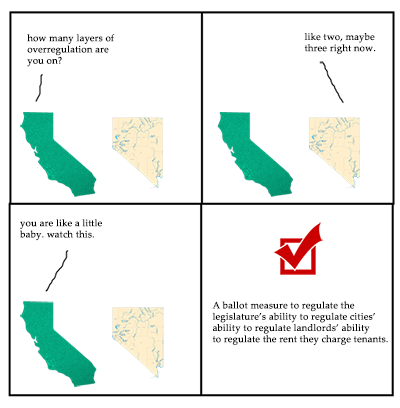

Proposition 10 repeals an existing statewide law saying that cities cannot institute rent control. I am tempted to oppose this measure, since in the IGM weighted poll, 95% of economists believe rent control is bad for the poor and reduces affordable housing, compared to only 1% who say it is good. And if rent control were legal, I have no doubt cities would try to decree that no house can ever cost more than $1, declare victory over evil greedy capitalists, and then get all confused a year later when the state had became an uninhabitable wasteland, because California. On the other hand, I also don’t like state governments telling city governments what to do, and the legislature saying “no community can institute this law which many of you want but we don’t like” seems like a violation of Archipelago principles and the idea of “laboratories of democracy”. I worry that standing up for this principle will end up costing the poor, but if you don’t have principles when those principles lead to something bad, then you just don’t have principles. On the other hand, is it really in keeping with localism for the California electorate to pass a ballot proposition repealing a law of the California legislature? Are we past the point where any principles can make sense of this at all?

This is another one where I don’t feel like I can do anything other than abstain.

Proposition 11 retroactively makes it legal to require ambulance operators to stay on-call during breaks. It is sponsored by an ambulance company who was sued for illegally requiring ambulance operators stay on-call during breaks. Instead of just paying damages like a normal company, they decided to put a proposition on the California ballot saying they were retroactively right all along. Their argument is that ambulance workers already get “breaks” in the sense of there being a lot of downtime when there are no emergencies, so normal break law requiring additional breaks shouldn’t apply to them. Also, it’s really hard to come up with a call schedule for emergency services at the best of times and regulations make that even more difficult. The mistake theorist in me is happy to admit that some of these are good points. But the conflict theorist in me would be much more comfortable with this argument coming from anybody other than an ambulance company who was already being sued for denying workers breaks. The correct sequence is “pass law saying you can do something, then do it”. Also, if the California legislature wants to give ambulance companies an exemption from normal break law, it can do that without a superlaw that can never be repealed. No.

Proposition 12 amends a previous proposition to clarify standards for factory farms in California. It mandates cage-free confinement for some animals, and increases minimum cage sizes for others. This is a very simple measure to prevent a tiny bit of preventable animal cruelty and make factory farming a little less bad. It is strongly supported by everyone in the effective altruist movement and most animal rights groups. It is opposed by PETA (who believe that animals should not be farmed at all) and by economists who point out that raising the minimum cage destroys jobs for low-cage workers. That part about the economists was a joke. There is no good reason to oppose this measure. Strong yes. If you only take my advice on one measure on the California ballot, let it be supporting this one.

Also, there was an old socialist talking point that all the promises of reform within capitalism only amount to “bigger cages, longer chains”. If Proposition 12 passes, capitalist reformers will have fulfilled half of their promises. How many other systems can say the same?