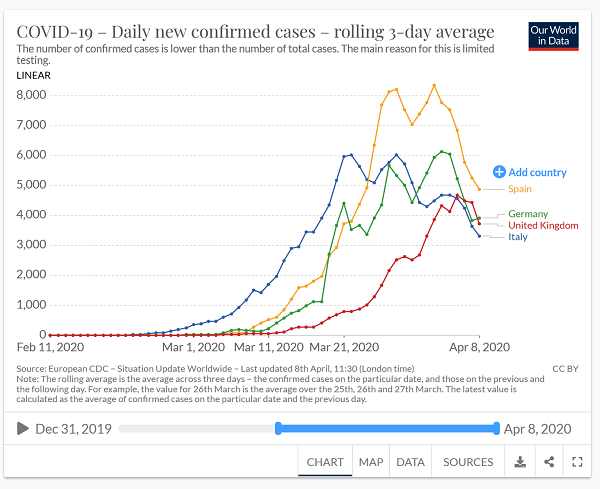

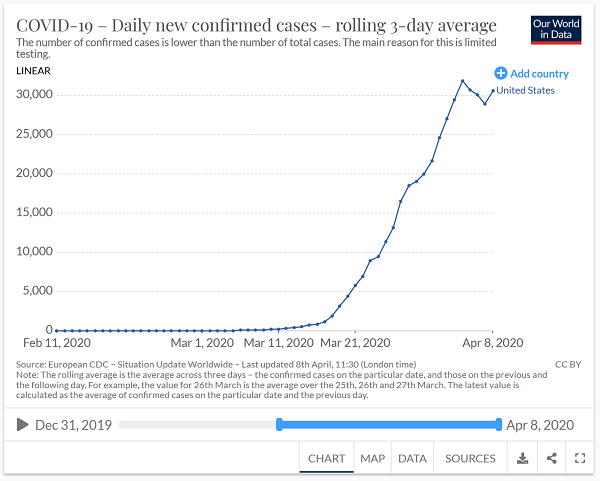

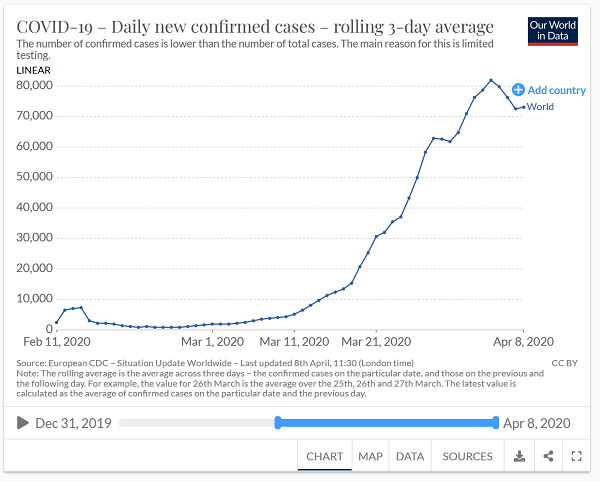

The second derivative is the rate of growth of the rate of growth. Over the past few weeks, the second derivative of total coronavirus cases switched from positive (typical of exponential growth) to zero or negative (typical of linear or sublinear growth) in most European countries. Over the past few days, it switched from positive to zero/negative in the United States and the world as a whole. These are graphs of the rate of growth – notice how they go from shooting upward to being basically horizontal or downward-sloping (source).

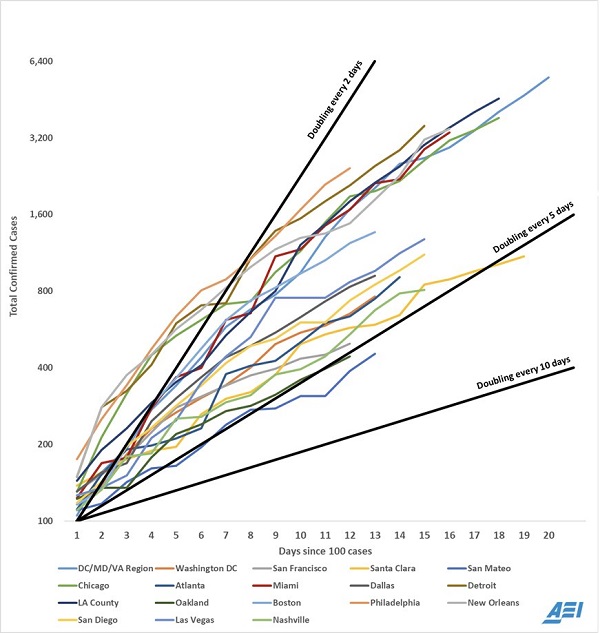

This graph shows the numbers a little differently, (source), but you can see the same process going on in individual US cities:

It would be premature to say we’re now winning the war on coronavirus. But we’ve stopped actively losing ground. If we were going to win, our first sign would be something like this. Current containment strategies are working.

As before, feel free to treat this as an open thread for all coronavirus-related issues. Everything here is speculative and not intended as medical advice.

The Bat Flu

SSC reader Trevor Klee has a great article on why humans keep getting diseases from bats (eg Ebola, SARS, Marburg virus, Nipah virus, coronavirus). He explains that because bats expend so much energy flying, they run higher body temperatures than other mammals, which degrades their DNA. Their DNA is such a mess that the usual immune system strategy of targeting suspicious DNA doesn’t work, so they accept constant low-grade infection with a bunch of viruses as a cost of doing business. Sometimes those viruses cross to humans, and then we get another bat-borne disease.

Subreddit user nodding_and_smiling doesn’t quite buy it:

I don’t think deep-diving into the bat immune system, while certainly very interesting, is necessary to explain the number zoonotic diseases from bats. I think a more important point is there is just a crazy number of bats, and the post doesn’t seem to fully appreciate this.

There are over 1,250 bat species in existence. This is about one fifth of all mammal species. Just to get a sense of this, let me ask a modified version of the question in the title:

“Why do human beings keep getting viruses from cows, sheep, horses, pigs, deer, bears, dogs, seals, cats, foxes, weasels, chimpanzees, monkeys, hares, and rabbits?”

That list contains species from four major mammal clades: ungulates (257 species), carnivora (270), primates (~300), and lagomorphs (91). Adding all these together, we don’t even get to 3/4 of the total number of bat species…

Read the full comment (and the ensuing discussion) for more, including whether biodiversity vs raw numbers is the appropriate measure here.

Mail Suffrage

The Wisconsin Democratic primary (plus some unrelated elections) went ahead as usual this week, with people going out to voting booths instead of voting by mail. Democrats wanted to allow (mandate?) mail voting, but Republicans refused.

Presumably Republicans assumed mail voting would benefit Democrats? The last time a state instituted vote-by-mail, in New Jersey, it did seem to increase the Democratic share of the vote.

I’m surprised by this, because I would have expected mail voting, as opposed to booth voting, benefits people with good executive function who are familiar with doing things by mail – ie older, richer people, ie Republicans. It would appear that I am wrong.

What if the epidemic isn’t done by November? There will probably be a discussion of lifting the shutdown to have a normal election, vs. voting entirely by mail, vs. combination where people who want to vote by mail can but the polls are open for everyone else. I don’t know if the second option is in the Overton Window right now (or if it should be). The party lines here seem to be the same: Nancy Pelosi is already pushing for it, and conservatives are already denouncing it as a liberal plot.

I’m in favor, obviously, but also terrified that something goes wrong. In one scenario, failure to agree on vote-by-mail rules (or failure to implement them competently) delays the election, with no clear way to get it back on track. In another, the sudden panicked switch to a less-tested voting method goes wrong in unpredictable ways and creates ambiguity over election results. It could be Bush v. Gore x 1000.

The Neoliberal Project has an analysis of what we should do and how to make postal voting work. I just really hope it doesn’t come to this.

Charity Update

Last week I linked a list of potentially good coronavirus charities cobbled together by some random people on the EA forum. Now a more serious organization, 80,000 Hours, has posted their own list.

The top option is still the Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security, which researches and advocates for biosecurity policy. Last week someone in the comments doubted the quality of their work, pointing out that one of their flagship efforts is a ranking of how prepared different countries are for a global pandemic; their 2019 listing put the US at the top, which now feels like a cruel joke. But I’m not sure how much to hold it against them. Looking at their webpage, it mostly investigates whether a country has good plans addressing various issues of a crisis, and lots of resources that it can deploy if needed. As best I can tell, the US had great plans and didn’t follow any of them, and lots of resources which it totally failed to deploy effectively. Responsible think tanks are probably not allowed to add a -10000 points at the end of their analysis for “but its leaders are idiots”. This might still be a good time to reread Samzdat on hokey country rankings and no_bear_so_low on hokey country rankings.

Speaking of charity, you can read on Twitter about the trials and tribulations of people trying to donate face masks to hospitals, and here’s an article from three years ago about issuing pandemic bonds as a novel insurance-type way of funding global disease response. Pretty neat.

And you might think that a page called The COVID Challenge where you sign up to deliberately get infected with coronavirus is a bad idea, but it’s actually some volunteers trying to make a list of people who would be willing to get deliberately infected (if it came to that) in order to test vaccines, which they will hand over to vaccine-makers once they get to the testing stage. Rationalist John Beshir did something like this for a malaria vaccine last year and earned $3200 (plus the warm glow of having made a difference) by letting himself getting bitten by infected mosquitoes in an Oxford laboratory.

There Is No Coronavirus In Ba Sing Se

Turkmenistan is a strange country. You probably remember it for its wacky former dictator Turkmenbashi, who among other things renamed the month of March after his mother, and told citizens that anyone who read his book three times would enter Heaven. Or for its wacky current dictator Gurbanguly Berdymukhamedov, who NPR describes as a “dentist/rapper/strongman”. Or for its impressive accomplishment of beating out North Korea to be named the most repressive country on Earth by Reporters Without Borders.

Its coronavirus response will do nothing to improve its reputation: early reports claimed it had banned mentioning the word ‘coronavirus’ or acknowledging its existence in any way.

The Diplomat argues this is not quite true; some state media seems to be using the word. But they are definitely arresting people for talking about it outside official government organs, and they are definitely denying that there are any cases in the country. Since Turkmenistan is right next to Iran, which has had thousands of cases for months, this is pretty implausible.

The Diplomat also requests that people try not to focus on the country’s wacky dictators so much every time they talk about it, since that makes it hard to get people to take its suffering seriously. Sorry, Diplomat and Turkmen people 🙁

And SSC reader Castilho describes their home country of Brazil, which seems to be right up there with Turkmenistan:

We’re one of the few countries in the developing world that actually could handle the pandemic reasonably well (We have around 61.000 ventilators, or 1 ventilator per 3.300 people, which isn’t actually that bad and could be expanded for a decent epidemic response)…

However, our president has decided to go all-in on denying how serious the virus is. The Atlantic even called him “the new leader of the Coronavirus denial movement“. He’s accusing local politicians who have instituted lockdowns of plotting to destroy the country’s economy in order to use it against him later. His sons, who are local politicians in the wealthy parts of the country, have been saying this is all a plot by leftist politicians together with the People’s Republic of China to make him and Trump look bad. I wish I was kidding…

The worst part is that he’s led a nationwide movement telling people to leave their homes and go back to their normal lives. The government actually wanted to make “Brazil can’t stop” into a nationwide campaign, but when a significant part of the population didn’t appreciate it, they just deleted the social media posts and now they claim there never was such a campaign.

Read the full comment for more.

And last month I wondered about the surprisingly slow spread of cases in Iran. I can’t find anyone saying so outright, but it seems like the numbers are probably wrong. At least that’s what I gather from articles like this and Twitter accounts like this highlighting the scale of the crisis there, which seems at least as bad as anywhere in the world. I don’t know if they’re deliberately lying about case numbers (why start now, after the numbers were so bad a few weeks ago?) or if testing has just completely broken down there. See also this article on how their form of government has led to power struggles and a garbled response. I would say something mean about radical Islamic fundamentalism, except that the whole thing mirrors blow for blow what happened between Cuomo and de Blasio in New York.

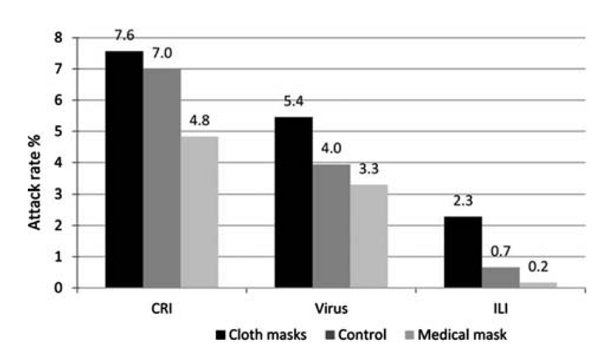

And finally, here’s a great article on the mystery of Japan. Tl;dr: cultural traditions like mask-wearing and bowing helped it for a while, crowded trains aren’t as bad as you’d think because nobody’s talking, banning large gatherings very early was a really good move, their weak half-hearted version of test-and-trace worked for a while out of sheer luck, but now cases are finally starting to rise and there probably won’t be a mystery to explain for much longer.

Economic Unanimity

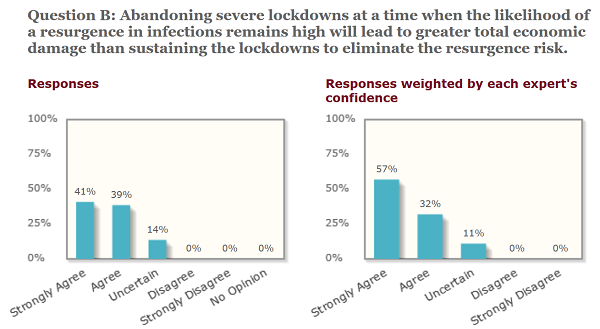

The IGM Economics Experts Panel surveys a view dozen top economists on the issues of the day. This month they’re focusing on coronavirus. Here are some sample results:

…they pretty unanimously support the lockdown, even when asked only to reflect on its economic impact.

Some socialists on social media are trying to spread a narrative where capitalists think the economy is more important than lives and want to lift the lockdown immediately, and it’s only socialists who are standing up for the importance of saving people. Top economists aren’t a perfect stand-in for capitalists, but it’s still pretty clear that they’re wrong.

Also, there are starting to be some econ papers trying to more rigorously analyze the pros and cons of lockdown. The Benefits and Costs of Flattening the Curve for COVID-19 says that “assuming that social distancing measures can substantially reduce contacts among individuals, we find net benefits of roughly $5 trillion in our benchmark scenario”.

USA! USA!

Is there anything Americans can be proud of here?

@noahpinion reminds us of America’s long history of being late on the trigger but doing a great job once we get started (Churchill: “You can always count on Americans to do the right thing – after they’ve tried everything else.”). We were late entrants into both World Wars but had an outsized effect on both of them. In that spirit, although we were very slow to start testing, we’ve ramped up impressively fast – from almost none to 1/3 of South Korean levels per capita within a few weeks.

Also worth celebrating – during the Wuhan phase of the pandemic, China built an impromptu 1,000 patient hospital in ten days. US media reported this as unbelievable – a sign that a young and vigorous country could accomplish feats that a decadent America could never dream of. But last week in New York, the Army Corps of Engineers converted the Javits Convention Center into an impromptu 2,000 patient hospital in…about ten days.

I don’t know, maybe this was easier because they’re converting an existing structure instead of building a whole new one (though even the Chinese used prefab units). But it’s nice to know we still have it in us to do things quickly. There’s no civilizational decline. If the government ever legalized building things quickly again, we’d be mopping the floor with China within weeks.

Legal Immunity

There’s a Jewish legal principle called marit ayin, which means that it’s illegal to do something which is legal but looks illegal. For example, you can’t eat some kind of plant-based Impossible Bacon, because it would look like you were eating real bacon. Some authorities say it is sometimes permissible to eat the Impossible Bacon if you leave the box out in a prominent position so that it doesn’t look illegal; I’m not sure of the details.

The argument is that widespread flagrant unpunished violation of the law makes the law uncompelling and unenforceable, and this is true whether the violation is real or imagined. If you never see anyone eat bacon, you probably won’t eat it yourself; if everyone around you seems to be eating bacon all the time, it feels less taboo. Also, if you’re a police officer, it’s hard to identify the real bacon eaters if there are a bunch of people eating Impossible Bacon who get annoyed every time you question them.

I was thinking about this recently with the news that Germany is considering issuing immunity certificates for people who have gotten coronavirus, recovered, and are now safe to do normal activities. It’s a good idea, but suffers from the same problem as Impossible Bacon – if there are hundreds of people going outside maskless, eating at restaurants, and sunning themselves on the beach, it’s going to be hard for the rest of us to take lockdown seriously enough.

The equivalent of the rabbis’ put-the-box-out solution would be for governments to issue not just a certificate but some kind of unique article of clothing people could wear to mark their status. For example, they might give an unusually shaped red cap – if the beaches are full of people in red caps, that’s fine and doesn’t say anything about whether you personally should go sunbathe. And if the beachgoers see someone without a red cap, they can question them or keep their distance.

This would take a lot of centralized coordination, though. I’m not sure how you could send the same message without a government order explaining what the cap meant to everybody. Though (as per this Onion article) wearing a fake pangolin snout over your nose would send a strong signal.

A reader who has overcome the disease emailed me to ask whether there are any useful volunteer opportunities for people like him – anyone have any advice?

Short Links

Last week I expressed confusion about how to measure population density so that arbitrary choices of border don’t distort the results. Commenters delivered by finding me this article on population-weighted density, which solves my theoretical concerns but doesn’t really change any of the numbers much.

The Netherlands is another country which, like Sweden and Brazil, is volunteering to be the control group for the great experiment of whether national lockdowns work. Maybe someone should compare them to Belgium or somewhere like that in a few months and see how they did.

An aircraft carrier captain publicly complained that the Navy was failing to address an epidemic aboard his ship; the Navy fired him for whistleblowing. I’m having a hard time thinking of any perspective other than “the Navy is bad and should be torn down totally to the foundations, preferably using some sort of land-based weapon so they can’t fight back”, but here’s a different ex-captain trying his best to give a nuanced perspective.

Say what you will about the New York Times’ coverage lately, but their cover design remains second to none.

This Tumblr post has a discussion of how/whether a Clinton administration might have responded differently to the pandemic, but the part I like is the discussion of the phrase “follow the pandemic response playbook”. It turns out this is a literal document, called the Playbook For Early Response To High Consequence Emerging Infectious Disease Threats And Biological Incidents, and you can read it here.

Marginal Revolution: are hospitals really saving that many people?

UK clinical guideline body NICE now officially recommends against using NSAIDs for coronavirus. Still not completely proven, but I think they’re right to advise caution. While most experts themselves behaved appropriately, this is more egg on the face of the media, which until a few weeks ago was running stories telling people this was a myth and they should ignore it.

538 surveyed infectious disease experts around the US, asking them to predict the number of cases in X days’ time, with confidence intervals. The results are in, and the experts did worse than just continuing the exponential curve on the graph would have. EDIT: But see here.

If you’re following Robin Hanson’s variolation proposals, you can watch Hanson debate vs. Zvi Moskowitz and vs. Greg Cochran (and here’s Cowen on Hanson). Anyway, viral dose seems to have gone mainstream, though nobody seems to be doing anything about it yet.

The two different interpretations of “flatten the curve”. I think this explains why so much of the discussion around this phrase has been confusing.

Trump Asks Medical Supply Firm 3M To Stop Selling N95 Respirators To Canada, and also Key Medical Supplies Were Shipped From US Manufacturers To Foreign Buyers. I think we’re supposed to be outraged about both of those things simultaneously but I can’t manage it, maybe some of you will have better luck.

How much risk do young people really face from coronavirus? What are the risks of long-term complications? Sarah C investigates.

Last week, Elon Musk got widespread praise (including here) for donating a thousand ventilators he managed to procure through his Tesla supply chain. Now the picture has become more confusing. Reporters looking at a picture of his shipment noticed that the boxes pictured are for BiPAP machines – technically a kind of ventilator, but not the kind hospitals need to fight coronavirus. Was the whole thing a giant mistake or cynical PR stunt? But then some hospitals tweeted thanking Tesla specifically for delivering “Medtronic invasive ventilators”, which are the kind hospitals need to fight coronavirus. Some people are theorizing that maybe hospitals don’t want to offend Musk since he might have real ventilators later, other people that maybe Musk got both some useful and some non-useful ventilators in his shipment. I dunno. In any case, he’s still promising to make some at Tesla factories, though.