You probably remember Herbert Hoover as the guy who bungled the Great Depression. Maybe you shouldn’t. Maybe you should remember him as a bold explorer looking for silver in the jungles of Burma. Or as the heroic defender of Tientsin during the Boxer Rebellion. Or as a dashing pirate-philanthropist, gallivanting around the world, saving millions of lives wherever he went. Or as the temporary dictator of Europe. Or as a geologist, or a bank tycoon, or author of the premier 1900s textbook on metallurgy.

How did a backwards orphan son of a blacksmith, dropped in the middle of a forgotten spot in the Midwest, grow up to be a captain of industry and a US President? How did he become such a towering figure in the history of philanthropy that biographer Kenneth Whyte claims “the number of lives Hoover saved through his various humanitarian campaigns might exceed 100 million, a record of benevolence unlike anything in human history”? To find out, I picked up Whyte’s Hoover: An Extraordinary Life In Extraordinary Times.

Herbert Hoover was born in 1874 to poor parents in the tiny Quaker farming community of West Branch, Iowa. His father was a blacksmith, his mother a schoolteacher. His childhood was strict. Magazines and novels were banned; acceptable reading material included the Bible and Prohibitionist pamphlets. His hobby was collecting oddly shaped sticks.

His father dies when he is 6, his mother when he is 10. The orphaned Hoover and his two siblings are shuttled from relative to relative. He spends one summer on the Osage Indian Reservation in Oklahoma, living with an uncle who worked for the Department of Indian Affairs. Another year passes on a pig farm with his Uncle Allen. In 1885, he is more permanently adopted by his Uncle John, a doctor and businessman helping found a Quaker colony in Oregon. Hoover’s various guardians are dutiful but distant; they never abuse or neglect him, but treat him more as an extra pair of hands around the house than as someone to be loved and cherished. Hoover reciprocates in kind, doing what is expected of him but excelling neither in school nor anywhere else.

In his early teens, Hoover gets his first job, as an office boy at a local real estate company. He loves it! He has spent his whole life doing chores for no pay, and working for pay is so much better! He has spent his whole life sullenly following orders, and now he’s expected to be proactive and figure things out for himself! Hoover the mediocre student and all-around unexceptional kid does a complete 180 and accepts Capitalism as the father he never had.

His first task is to write some newspaper ads for Oregon real estate. He writes brilliant ads, ads that draw people to Oregon from every corner of the country. But he learns some out-of-towners read his ads, come to town, stay at hotels, and are intercepted by competitors before they negotiate with his company. Of his own initiative, he rents several houses around town and turns them into boarding houses for out-of-towners coming to buy real estate, then doesn’t tell his competitors where they are. Then he marks up rent on the boarding houses and makes a tidy profit on the side. Everything he does is like this. When an especially acrimonious board meeting threatens to split the company, a quick-thinking Hoover sneaks out and turns off the gas to the building, plunging the meeting into darkness. Everyone else has to adjourn, the extra time gives cooler heads a change to prevail, and the company is saved. Everything he does is like this.

(on the other hand, he has zero friends and only one acquaintance his own age, who later describes him to biographers as “about as much excitement as a china egg”.)

Hoover meets all sorts of people passing through the Oregon frontier. One is a mining engineer. He regales young Herbert with his stories of traveling through the mountains, opening up new sources of minerals to feed the voracious appetite of Progress. This is the age of steamships, skyscrapers, and railroads, and to the young idealistic Hoover, engineering has an irresistible romance. He wants to leave home and go to college. But he worries a poor frontier boy like him would never fit in at Harvard or Yale. He gets a tip – a new, tuition-free university might be opening in Palo Alto, California. If he heads down right away, he might make it in time for the entrance exam. Hoover fails the entrance exam, but the new university is short on students and decides to take him anyway.

Herbert Hoover is the first student at Stanford. Not just a member of the first graduating class. Literally the first student. He arrives at the dorms two months early to get a head start on various money-making schemes, including distributing newspapers, delivering laundry, tending livestock, and helping other students register. He would later sell some of these businesses to other students and start more, operating a constant churn of enterprises throughout his college career. His academics remain mediocre, and he continues to have few friends – until he tries out for the football team in sophomore year. He has zero athletic talent and fails miserably, but the coach (whose eye for talent apparently transcends athletics) spots potential in Hoover and asks him to come on as team manager. In this role, Hoover is an unqualified success. He turns the team’s debt into a surplus, and starts the Big Game – a UC Berkeley vs. Stanford football match played on Thanksgiving which remains a beloved Stanford football tradition.

Other Stanford students notice his competence, and by his senior year he is running not just the football team but the baseball team, a lecture series, a set of concerts and plays, and much of the student government. For the first time, he makes many social contacts, which is sort of like having friends, although real emotional connection remains beyond him. Whyte describes an occasion when Will Irwin, the football team’s star player, suffers a career-ending injury:

[Irwin] was outfitted with a plaster cast and deposited in his dorm room. Hoover visited him to approve spending on the athlete’s medical supplies…Hoover carried his head to one side as he took in Irwin’s cast and obvious discomfort…To make conversation and keep up his courage, Irwin tried to make light of his situation and watched as Hoover tried to laugh. A ‘deep, rich, chuckle’ originated far down in his chest, Irwin recalled, yet it was strangled ‘before it came to the surface’. Hoover did not offer the patient a single word of consolation or reassurance during his time in the room. Irwin assumed hat Hoover’s sympathies, for he did appear to be affected, were garroted and buried in the same internal graveyard as the chuckle. After a few minutes, Hoover headed for the door and, at the last instant, turned and blurted ‘I’m sorry’. Irwin recognized that this minimal expression of emotion was as traumatic for Hoover as a broken ankle.

Hoover graduates Stanford in 1895 with a Geology degree. He plans to work for the US Geological Survey, but the Panic of 1895 devastates government finances and his job is cancelled. Hoover hikes up and down the Sierra Nevadas looking for work as a mining engineer. When none materializes, he takes a job an ordinary miner, hoping to work his way up from the bottom:

He signed on as a mucker at the Reward Mine, shoveling wet dirt and rock into an ore car on ten-hour shifts for two dollars a day, seven days a week. The Cornishmen mocked him for his schooling and taught him the basics of their mole-like existence: how to breathe while the dust cleared from a blast; how to nap in a steel wheelbarrow heated from underneath by candles. The ceaseless grind of filling his car and pushing it up the slick rails of the Reward’s dripping tunnels taxed Hoover’s stamina. He was tortured in his sleep by muscle pain and neuralgia.

After a few months, he finds a position as a clerk at a top Bay Area mining firm. One year later, he is a senior mining engineer. He is moving up rapidly – but not rapidly enough for his purposes. An opportunity arises: London company Berwick Moreing is looking for someone to supervise their mines in the Australian Outback. Their only requirement is that he be at least 35 years old, experienced, and an engineer. Hoover (22 years old, <1 year experience, geology degree only) travels to Britain, strides into their office, and declares himself their man. The executives “professed astonishment at Americans’ ability to maintain their youthful appearance” (Hoover had told them he was 36), but hire him and send him on an ocean liner to Australia.

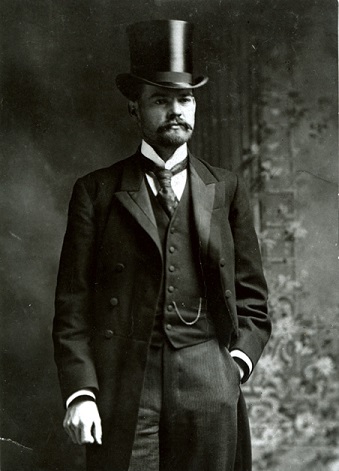

22 year old Hoover trying his best to look like a respectable 36 year old capitalistWhat does he think of his new home?

In numerous letters over the next two years, Hoover would refer to Western Australia as hell, and he meant it. The landscape was hell, a flat, monotonous, dust-choked desert, barren but for low tangles of mulga and wattle bush as far as the eye could see.

The climate was hell, a dry broil for the most part, one hundred degrees at midnight for days on end…

The insects were hell, scorpions, tarantulas, snakelike centipedes, and disease carrying airborne pests with an unerring aim for one’s eyes and dinner plate…

The settlements were hell, overnight ramshackled boomtowns with names like Kalgoorie and Coolgardie, box-shaped lodgings with walls of corrugated iron that roared in the wind, beds with unwashed sheets, meals of beans, biscuits, canned potatoes, and “tinned dog” (probably mutton or ham), entertainment consisting of out-of-date copies of American magazines, the odd horse race, and drunks dodging camels on Main Street.

“You cannot appreciate the real damnation of this country,” wrote Hoover.

Hoover soon manages to personally offend every single person in Australia:

The harshness of the environment and Hoover’s desire to prove himself drew an element of savagery from him. He fired rafts of employees for laziness and incompetence and dumped two of his own assistants for being “damn noodle heads”…uncompromising in pursuit of better margins, Hoover haggled with camel dealers to save a few dollars on freight costs He moved swiftly to shut losing properties…He lengthened shifts in the Coolgardie mines from 44 to 48 hours (his efforts to introduce labor-saving technology at another mine would result in a job action, which Hoover answered by firing the strikers and hiring more pliable Italian labor)…

Hoover drove himself relentlessly as well, sleeping as little as four hours a night. His eyes and stomach gave him trouble. Months of roasting on the Western Australia grill left him with a chronic inflammation of the bladder. Sometimes he was so ill he could not sit up, but he refused to slow down, traveling on his back on a mattress on the bottom of a horse-drawn cart.

After a year, Hoover is the most hated person in Australia, and also doing amazing. His mines are producing more ore at lower prices than ever before. He receives promotion after promotion.

Success goes to his head and makes him paranoid. He starts plotting against his immediate boss, Berwick Moreing’s Australia chief Ernest Williams. Thought Williams didn’t originally bear him any ill will, all the plotting eventually gets to him, and he arranges for Hoover to be transferred to China. Hoover is on board with this, since China is a lucrative market and the transfer feels like a promotion. He travels first back to Stanford – where he marries his college sweetheart Lou Henry – and then the two of them head to China.

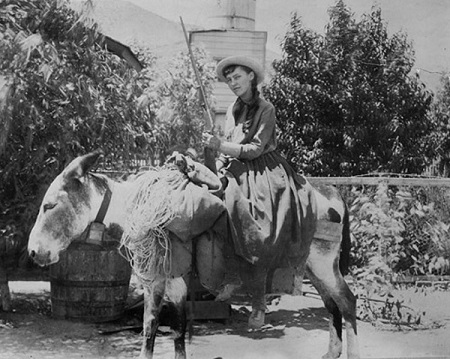

Herbert Hoover’s college sweetheartChina is Australia 2.0. Hoover hates everyone in the country and they hate him back:

Hoover shared the prevailing European conviction of Chinese racial inferiority. He would write of the ‘simply appalling and universal dishonesty of the working classes, the racial slowness, and the low average of intelligence’…Hoover was baffled at their lack of enthusiasm for mechanization and orderly administration. Lou reported that ‘the utter apathy of the Chinese to everything, their unconquerable dilatoriness’ was almost heartbreaking to her energetic husband.

The same conflicts are playing themselves out on the world stage, as Chinese resentment at their would-be-colonizers boils over into the Boxer Rebellion. A cult with a great name – “Society Of Righteous And Harmonious Fists” – takes over the government and encourages angry mobs to go around killing Westerners. Thousands of Europeans, including Herbert and Lou, barricade themselves in the partly-Europeanized city of Tientsin to make a final last stand. Hoover

“…fought fires in the settlement and delivered food and medical supplies on his bicycle, hugging the brick walls along the street to avoid gunfire. Reporters on the scene observed that he seemed to be moving on the double quick, furiously jingling the change in his pockets and chewing nuts without shucking them. Lou, unwilling to join other women in the safety of the basement at city hall, ran bicycle errands of her own, a .38 Mauser strapped to her hip…

In between dodging artillery shells, Hoover furiously negotiates property deals with his fellow besiegees. He argues that if any of them survive, it will probably because Western powers invade China to save them. That means they will soon be operating under Western law, and people who had already sold their mines to Western companies would be ahead of the game and avoid involuntary confiscation. Somehow, everything comes up exactly how Hoover predicts. US Marines arrive in Tientsin to liberate the city (Hoover marches with them as their local guide) and he is ready to collect his winnings.

Problem: it turns out that “Whatever, sure, you can have my gold mine, we’re all going to die anyway” is not legally binding. Hoover, enraged as he watches apparently done deals slip through his fingers, reaches new levels of moral turpitude. He offers the Chinese great verbal deals, then gives them contracts with terrible deals, saying that this is some kind of quaint foreign custom and if they just sign the contract then the verbal deal will be the legally binding one (this is totally false). At one point, he literally holds up a property office with a gun to get the deed to a mine he wants. Somehow, after consecutively scamming half the population of Asia, he ends up with the rights to China’s most lucrative minefields. Berwick Moreing congratulates him and promotes him to managing director. He and Lou sail for London to live the lives of British corporate bigshots.

Predictably, Hoover makes an amazing corporate bigshot:

Hoover had a ‘gift of juggling corporate assets in such a manner that insiders almost always benefitted’, whatever happened to the capital of the original shareholders. He was masterful at wielding write-offs and preference shares with multiple voting power on the grounds that new capital was required to avert bankruptcy. His favorite deals were those so complicated no one else could figure out they worked.

On top of this, Hoover could keep mental maps of dozens of mines in his mind and, by one account, follow the progress of each shaft like a blindfolded chess master. He liked to receive telegrams from these properties and, without opening them, noting only the date and address, predict the level of the mine and the cost per ton of ore. He was usually correct.

His intellectual capacities and powerful will made Hoover a fearsome negotiator. Arriving at the table with shirtsleeves rolled up, abrupt and aggressive, he had a singular talent for stripping away nonessential information and getting directly to the root of things, and he knew how to close. He possessed what one businessman said was a curious dynamic force that could compel the most reluctant person to put signatures to paper.

Also predictably, Hoover manages to offend everyone in Britain. Soon he is signing off on a ‘mutually agreeable’, ‘amicable’ dismissal from Berwick Moreing. They agree to let him go on the condition that he does not compete with them – a promise he breaks basically instantly. He goes into banking, and his “bank” funds mining operations in a way indistinguishable from being a mining conglomerate. Eventually he abandons even this fig leaf, and just mines directly.

But in other ways, his tens of millions of dollars are mellowing him out. Over his years in London, he develops hobbies besides making money and crushing people. He starts a family; he and Lou have two sons, Herbert Jr and Allen. He even hosts dinner parties, very gradually working on the skill of getting through an entire meal without mortally offending any guests:

His fund of small talk was perpetually overdrawn, and if he interacted with the guests at his elbows, it was typically in a series of grunts or nods. If he wanted to make a point, he made it in a flat voice and then stopped abruptly, as one friend noted, someone had pulled his plug. If aroused, he would speak with force, sometimes veering into tactlessness, pursuing minor differences of opinion so harshly and indignantly that his victims nursed grudges for the rest of their natural lives. One acquaintance considered him the bluntest man in Europe, another ‘the rudest man in London’. He seldom took the time to enjoy his food, and was once clocked swallowing five courses in eleven minutes flat.

And he writes a book on metallurgy, which becomes the canonical text for a generation of engineering students. He can’t resist adding some of his own commentary. For example:

Among the book’s idiosyncratic touches is Hoover’s attempt to end discussion of the capacity of different races of workers, a common debating point in early 20th century mining, by quantifying a racial productivity gap. He deemed one white worker equal to two or three of the colored races in simple tasks like shoveling, and as high as one to eleven in the most complicated mechanical work.

But also:

To the engineer falls the work of creating from the dry bones of scientific fact the living body of industry. It is he whose intellect and direction bring to the world the comforts and necessities of daily need. Unlike the doctor, his is not the constant struggle to save the weak. Unlike the soldier, destruction is not his prime function. Unlike the lawyer, quarrels are not his daily bread. Engineering is the profession of creation and of construction, of stimulation of human effort and accomplishment.

Finally, having won respect in the financial, social, and intellectual worlds, he decides the natural next step is to become a public servant. Insofar as he has any political philosophy, he thinks of engineers as a sort of benevolent master race, destined to lead the world into an efficient technocracy. And he can think of no better standard-bearer than himself. He writes some Stanford friends, asking if they would support him for Governor of California. They suggest he start lower on the ladder, and offer him a position on the Stanford Board of Trustees, which he accepts (trustees are supposed to live in Palo Alto, but he lies and tells them he is moving back right away). He begins his public career by attacking tenure, “which he considered a protection racket for the weak and lazy and an outrage on the sanctity of higher education.”

Okay, fine. He hadn’t mellowed out that much. He manages to offend everyone in Stanford basically immediately, and that probably would have been the end of his career in politics. Luckily for him, World War I chooses that moment to break out, and little things like tenure are suddenly forgotten in the shadow of the greatest conflict the world has ever known.

II.

Count up the victims of World War I, and American tourists will be pretty far down the list. But victims they were. When the conflict broke out, thousands of Americans were overseas visiting the cathedrals of Florence or the museums of London. They woke up one morning to find the ships that were supposed to take them back had been conscripted into the war effort, or refused to sail for fear of enemy fire. The banks that were supposed to cash their travelers’ checks were panicking, or devoting all their funds to the war effort, or dealing with a million other things. The hotels that were supposed to house them were closed indefinitely, their employees rushing to enlist out of patriotic fervor. And so thousands of frantic Americans, stuck in a foreign continent with no money and nowhere to stay, showed up at the door of the US Embassy in London and said – help!

The US Consulate in London didn’t know how to solve these problems either. But Herbert Hoover, still high on his decision to pivot to philanthropy and public service, calls them up and asks if he can assist. They say yes, definitely. Hoover gets in touch with his rich friends, passes around the collection plate, and organizes a Committee For The Assistance Of American Travelers. Then he gets to work, the way only he can:

Within 24 hours, Hoover’s committee had its own stationery, and within forty-eight it was operating a booth in the ballroom of the Savoy Hotel as well as three other London locations. Through his business connections, Hoover managed to bypass restrictions on telegraph service and open a transatlantic line to allow Americans to wire money to stranded friends and relatives. In a city suddenly flooded with refugees, he reserved for American travelers some two thousand rooms in hotels or boardinghouses. He issued a press release proclaiming that his Residents’ Committee was assuming charge of all American relief work in the city, and that in doing so it had the blessings of its honorary chairman, Walter Hines Page, the US ambassador to London.

…which is totally false. Hoover is starting to display a pattern that will stick with him his whole life – that of crushing competing charities. He begins a lobbying effort to get the US Embassy to ban all non-Hoover relief work, focusing on the inefficiency of having multiple groups working on the same problem. When the US Assistant Secretary Of War arrives in London to coordinate a response, he is met on the dock by Hoover employees, who demand he consult with Hoover before interfering in the US tourist issue. Eventually the Embassy, equally exasperated by Hoover’s pestering and impressed with his results, agrees to give him official control of the relief effort.

After two months of work, Hoover and his Committee have repatriated all 120,000 US tourists, supporting them in style until it could find them boat tickets. All of its loans and operating costs have been repaid by grateful tourists, and its budget is in the black. The rescued travelers are universal in their praise for Hoover, albeit partly because Hoover has threatened to ruin any of them who get too critical:

Other complainants were received with less patience, including a hotheaded professor of history from the University of Michigan, who wrote to accuse the Residents’ Committee of mistreatment. Hoover refuted his charges indignantly and comprehensively, copying his response to the president of the university and its board of regents. After a meeting with his employer, the professor returned Hoover an abject retraction and apology.

Just as Hoover is preparing to rest on his laurels, he receives a cry for help. Germany has occupied and blockaded Belgium. The blockade prevents this tiny, heavily urban country from importing food, and the Belgians are starving. Germany needs its own food for its own armies, and is refusing to help. The Belgians order a thousand tons of grain from Britain, but when their representative comes to pick it up, Britain refuses to let them transport it, nervous at sending food into enemy-occupied territory. During tense negotiations, someone suggests using neutral power America as a go-between. But America is 5,000 miles away and busy with its own problems. So the US Ambassador to Britain asks his new best friend Herbert Hoover if he has any ideas.

Hoover invites Emile Francqui, a Belgian mining engineer he knows, to Britain. Together, they plan a Committee For The Relief of Belgium, intended not just to help transport the thousand tons of grain at issue, but to develop a long-term solution to the impending Belgian famine. Nothing like this has ever been tried before. Belgium has seven million people and almost no food. No government is offering to help, and they don’t have enough money to feed seven million people even for one day, let alone indefinitely. Hoover springs into action…

…by crushing all competing attempts to provide food for Belgium. He attacks the Rockefeller Foundation, which is trying to help, with a blitz of press coverage accusing it of various forms of insensitivity and interference, until it finally backs off. Then he gets to work on the government:

The letter bore several Hoover watermarks, beginning with its heavy load of facts and figures organized in point form. It noted that myriad relief committees were springing up both inside and outside of Belgium, and urged consolidation. “It is impossible to handle the situation except with the strongest centralization and effective monopoly, and therefore the two organizations [Hoover outside Belgium and Francqui inside it] will refuse to recognize any element except themselves alone.” The letter also contained Hoover’s usual autocratic and slightly paranoid demands for “absolute command” of his part of the enterprise.

Control attained, Hoover springs into action actually feeding Belgium. He launches one of the largest public relations campaigns the world has ever seen, sending letters to newspapers around the world asking for donations. He “urged reporters to investigate the famine conditions in Belgium and play up the ‘detailed personal horror stuff’. He personally arranged for a motion picture crew to capture footage of food lines in Brussels, and he hired famous authors, including Thomas Hardy and George Bernard Shaw, to plead for public support of the rescue effort.” He constantly telegrams his exasperated wife and children, now safely back in Palo Alto, demanding they raise more and more money from the West Coast elite.

He browbeats shipping conglomerates until they agree to ship his food for free, then browbeats railroads until they agree to carry it. By telegraph and letter he coordinates banks, docks, trains, ships, and relief workers on both sides of the Atlantic. But that’s just the prelude. His real problem is the governments. Britain doesn’t want food shipped to Belgium, because right now the starving Belgians are Germany’s problem, and they don’t want to solve an enemy’s problem for them. But Germany also doesn’t want food shipped to Belgium, because the Belgians are resisting the occupation, and they figure starvation will make them more compliant. Shuttling back and forth across the North Sea, Hoover tries to get them to switch theories: Germany needs to think starving Belgians are their problem which it would be helpful to solve, and Britain needs to think starvation would make Belgians more compliant with the German occupation. In the end, both countries allow the shipments.

He goes on a fact-finding mission to Belgium, and manages to somehow offend everyone in the country that he is, at that very moment, saving from mass starvation:

A third of Brussels’ population was receiving free food at more than a hundred canteens set up by the Comite Central and supplied by the CRB. Ration cards entitled the bearer to coffee, soup, and bread. On the cold, wet morning of December 1, Whitlock took Hoover to the street outside a theater that had been converted to a canteen in the Quarter des Marolles. They saw hundreds of Belgians shivering silently in the breadline…Whitlock kept his eyes on Hoover throughout the visit and saw him turn away and stare off down the street rather than share his feelings. Whitlock understood Hoover’s reaction as simple reticence. Others witnessing the same sort of behavior found it disturbing. They noticed how Hoover obsessed over the logistics of food distribution while avoiding interaction with recipients of relief and thought him a bloodless man. “He told of the work in Belgium as coldly as if he were giving statistics of production,” said US official. “From his words and his manner he seemed to regard human beings as so many numbers. Not once did he show the slightest feeling.”

Hoover’s reticence was chronic. He was the sort of man who could sit for three hours on a train with his closest colleagues and not utter a single word, or bid farewell to his wife, not expecting to see her again for several months, in a curt telegraph: “Goodbye, Love, Bert”. It was often difficult to know if his behavior was due to bad manners, callousness, anxiety, or an effort to manage powerful emotions, because he was capable of all these things. Indeed, a few days after he averted his eyes from the breadline, he wrote, “It is difficult to state the position of the civil population of Belgium without becoming hysterical.” The sight of ragged and hungry children especially bothered him, and he soon inaugurated a program of daily hot meals of bread and cocoa at Belgian schools.

By 1915, Hoover is, indeed, feeding millions of Belgians, indefinitely, using only private funding. He is also almost broke. Millions of Brits and Americans have given him contributions, from tycoons donating fortunes to ordinary people donating their wages, but it’s not enough. His expenses pass $5 million a month, which would be about $100 million today; all these bills are starting to catch up to him. In an act of supreme sacrifice, Hoover pledges his entire personal fortune as collateral for the Committee’s loans, then takes out more money. The grain shipments continue to flow, but his credit is at its end.

He continues beating on the doors of every government official he can find – British, German, American – demanding help. They all say their budgets are already occupied with the war effort. He begs them, lectures them, tells them that millions of people are doing to die. He goes all the way to the top, finagling an opportunity to meet with British Prime Minister David Lloyd George. Lloyd George later calls Hoover’s presentation “the clearest he had [ever] heard on any subject”, but he can offer only moral support.

What finally works is going to Germany and meeting with their top military brass. The brass are unimpressed; they still think that Belgium starving is as likely to help them as hinder. But the contact spooks top British officials, who agree to meet with Hoover again. Hoover feeds them carefully crafted lies, saying that the German brass have told him that British aid to Belgium would be a disaster to the Central Powers and so they, the Germans, are going to fund everything Hoover wants and more. “Oh no they don’t!” say the British, who promise to give Hoover even more funding than his imaginary German partners. The Committee for the Relief Of Belgium is finally back in the black. And what a black it is:

The scope and powers of the Committee For Relief of Belgium were mindboggling. Its shipping fleet flew its own flag. Its members carried special documents that served as CRB passports. Hoover himself was granted a form of diplomatic immunity by all belligerents, with the British permitting him to cross the Channel at will and the Germans providing him a document saying ‘this man is not to be stopped anywhere under any circumstances’. Hoover had privileged access to generals, diplomats, and ministers. He enjoyed personal contacts with the heads of warring governments. He negotiated treaties with the belligerents, advised them on policy, and delivered private messages among them. Great Britain, France, and Belgium would soon be turning over to him $150 million a year, enough to run a small country, and taking nothing for it beyond his receipt. As one British official observed, Hoover was running ‘a piratical state organized for benevolence.’

In 1917, America enters World War I. Hoover is no longer neutral and so has to resign from the CRB. He returns to the US a war hero. The New York Times proclaims Hoover’s CRB work “the greatest American achievement of the last two years.” There is talk that he should run for President. Instead, he goes to Washington and tells President Woodrow Wilson he is at his service.

Wilson is working on the greatest mobilization in American history. He realizes one of the US’ most important roles will be breadbasket for the Allied Powers, and names Hoover “food commissioner”, in charge of ensuring that there is enough food to support the troops, the home front, and the other Allies. His powers are absurdly vast – he can do anything at all related to the nation’s food supply, from fixing prices to confiscating shipments to telling families what to eat. The press affectionately dubs him “Food Dictator” (I assume today they would use “Food Czar”, but this is 1917 and it is Too Soon).

Hoover displays the same manic energy he showed in Belgium. His public relations blitz telling families to save food is so successful that the word “Hooverize” enters the language, meaning to ration or consume efficiently. But it turns out none of this is necessary. Hoover improves food production and distribution efficiency so much that no rationing is needed, America has lots of food to export to Europe, and his rationing agency makes an eight-digit profit selling all the extra food it has.

By 1918, Europe is in ruins. The warring powers have declared an Armistice, but their people are starving, and winter is coming on fast. Also, Herbert Hoover has so much food that he has to swim through amber waves of grain to get to work every morning. Mountains of uneaten pork bellies are starting to blot out the sky. Maybe one of these problems can solve the other? President Wilson dispatches Hoover to Europe as “special representative for relief and economic rehabilitation”. Hoover rises to the challenge:

Hoover accepted the assignment with the usual claim that he had no interest in the job, simultaneously seeking for himself the broadest possible mandate and absolute control. The broad mandate, he said, was essential, because he could not hope to deliver food without refurnishing Europe’s broken finance, trade, communications, and transportation systems…

Hoover had a hundred ships filled with food bound for neutral and newly liberated parts of the Continent before the peace conferences were even underway. He formalized his power in January 1919 by drafting for Wilson a post facto executive order authorizing the creation of the American Relief Administration (ARA), with Hoover as its executive director, authorized to feed Europe by practically any means he deemed necessary. He addressed the order to himself and passed it to the president for his signature…

The actual delivery of relief was ingeniously improvised. Only Hoover, with his keep grasp of the mechanics of civilization, could have made the logistics of rehabilitating a war-ravaged continent look easy. He arranged to extend the tours of thousands of US army officers already on the scene and deployed them as ARA agents in 32 different countries. Finding Europe’s telegraph and telephone services a shambles, he used US Navy vessels and Army Signal Corps employees to devise the best-functioning and most secure wireless system on the continent. Needing transportation, Hoover took charge of ports and canals and rebuilt railroads in Central and Eastern Europe. The ARA was for a time the only agency that could reliably arrange shipping between nations…

The New York Times said it was only apparent in retrospect how much power Hoover wielded during the peace talks. “He has been the nearest approach Europe has had to a dictator since Napoleon.”

Once again, Hoover faces not only the inherent challenge of feeding millions, but opposition from the national governments he is trying to serve. Britain and France plan to let Germany starve, hoping this will decrease its bargaining power at Versailles. They ban Hoover from transporting any food to the defeated Central Powers. Hoover, “in a series of transactions so byzantine it was impossible for outsiders to see exactly what he was up to”, causes some kind of absurd logistics chain that results in 42% of the food getting to Germany in untraceable ways.

He is less able to stop the European powers’ controlled implosion at Versailles. He believes 100% in Woodrow Wilson’s vision of a fair peace treaty with no reparations for Germany and a League Of Nations powerful enough to prevent any future wars. But Wilson and Hoover famously fail. Hoover predicts a second World War in five years (later he lowers his estimate to “thirty days”), but takes comfort in what he has been able to accomplish thus far.

He returns to the US as some sort of super-double-war-hero. He is credited with saving tens of millions of lives, keeping Europe from fraying apart, and preventing the spread of Communism. He is not just a saint but a magician, accomplishing feats of logistics that everyone believed impossible. John Maynard Keynes:

Never was a nobler work of disinterested goodwill carried through with more tenacy and sincerity and skill, and with less thanks either asked or given. The ungrateful Governments of Europe owe much more to the statesmanship and insight of Mr. Hoover and his band of American workers than they have yet appreciated or will ever acknowledge. It was their efforts…often acting in the teeth of European obstruction, which not only saved an immense amount of human suffering, but averted a widespread breakdown of the European system.

III.

Hoover wants to be president. It fits his self-image as a benevolent engineer-king destined to save the populace from the vagaries of politics. The people want Hoover to be president; he’s a super-double-war-hero during a time when most other leaders have embarrassed themselves. Even politicians are up for Hoover being president; Woodrow Wilson is incapacitated by stroke, leaving both Democrats and Republicans leaderless. The situation seems perfect.

Hoover bungles it. He plays hard-to-get by pretending he doesn’t want the Presidency, but potential supporters interpret this as him just literally not wanting the Presidency. He refuses to identify as either a Democrat or Republican, intending to make a gesture of above-the-fray non-partisanship, but this prevents either party from rallying around him. Also, he might be the worst public speaker in the history of politics.

Warren G. Harding, a nondescript Senator from Ohio, wins the Republican nomination and the Presidency. Hoover follows his usual strategy of playing hard-to-get by proclaiming he doesn’t want any Cabinet positions. This time it works, but not well: Harding offers him Secretary of Commerce, widely considered a powerless “dud” position. Hoover accepts.

Harding is famous for promising “return to normalcy”, in particular a winding down of the massive expansion of government that marked WWI and the Wilson Administration. Hoover had a better idea – use the newly-muscular government to centralize and rationalize America. In his first few years in Commerce – hitherto a meaningless portfolio for people who wanted to say vaguely pro-prosperity things and then go off and play golf – Hoover instituted/invented housing standards, traffic safety standards, industrial standards, zoning standards, standardized electrical sockets, standardized screws, standardized bricks, standardized boards, and standardized hundreds of other things. He founded the FAA to standardize air traffic, and the FCC to standardize communications. In order to learn how his standards were affecting the economy, he founded the NBER to standardize government statistics.

But that isn’t enough! He mediates an inter-state conflict over water rights to the Colorado River, even though that would normally be a Department of the Interior job. He solves railroad strikes, over the protests of the Department of Labor. “Much to the annoyance of the State Department, Hoover fielded his own foreign service”. He proposes to transfer 16 agencies from other Cabinet departments to the Department of Commerce, and when other Secretaries shoot him down, he does all their jobs anyway. The press dub him “Secretary of Commerce and Undersecretary Of Everything Else”.

Hoover’s greatest political test comes when the market crashes in the Panic of 1921. The federal government has previously ignored these financial panics. Pre-Wilson, it was small and limited to its constitutional duties – plus nobody knew how to solve a financial panic anyway. Hoover jumps into action, calling a conference of top economists and moving forward large spending projects. More important, he is one of the first government officials to realize that financial panics have a psychological aspect, so he immediately puts out lots of press releases saying that economists agree everything is fine and the panic is definitely over. He takes the opportunity to write letters saying that Herbert Hoover has solved the financial panic and is a great guy, then sign President Harding’s name to them. Whether or not Hoover deserves credit, the panic is short and mild, and his reputation grows.

While everyone else obsesses over his recession-busting, Hoover’s own pet project is saving the Soviet Union. Several years of civil war, communism, and crop failure have produced mass famine. Most of the world refuses to help, angry that the USSR is refusing to pay Czarist Russia’s debts and also pretty peeved over the whole Communism thing. Hoover finds $20 million to spend on food aid for Russia, over everyone else’s objection:

Russian relief would prove less popular than the Belgian variety, with the left accusing Hoover of seeking to undermine communism with capitalist aid…and the right charging him with rescuing and legitimating the shaky Soviet regime. Hoover gave the same answer to all critics: ‘Twenty million people are starving. Whatever their politics, they shall be fed.’

Maxim Gorky, in Italy nursing his tuberculosis, wrote Hoover personally: ‘In the past year you have saved from death three and one-half million children, five and one-half million adults. In the history of practical humanitarianism I know of no accomplishment which in…magnitude and generosity can be compared to the relief you have actually accomplished.

So passed the early 1920s. Warren Harding died of a stroke, and was succeeded by Vice-President “Silent Cal” Coolidge. Coolidge won re-election easily in 1924. Hoover continued shepherding the economy (average incomes will rise 30% over his eight years in Commerce), but also works on promoting Hooverism, his political philosophy. It has grown from just “benevolent engineers oversee everything” to something kind of like a precursor of modern neoliberalism:

Hoover’s plan amounted to a complete refit of America’s single gigantic plant, and a radical shift in Washington’s economic priorities. Newsmen were fascinated by is talk of a ‘third alternative’ between ‘the unrestrained capitalism of Adam Smith’ and the new strain of socialism rooting in Europe. Laissez-faire was finished, Hoover declared, pointing to antitrust laws and the growth of public utilities as evidence. Socialism, on the other hand, was a dead end, providing no stimulus to individual initiative, the engine of progress. The new Commerce Department was seeking what one reporter summarized as a balance between fairly intelligent business and intelligently fair government. If that were achieved, said Hoover, ‘we should have given a priceless gift to the twentieth century.’

Finally, it is 1928. Hoover feels like he has accomplished his goal of becoming the sort of knowledgeable political insider who can run for President successfully. Silent Cal decides not to run for a second term (in typical Coolidge style, he hands a piece of paper to a reporter saying “I do not choose to run for President in 1928” and then disappears and refuses to answer further questions). The Democrats nominate Al Smith, an Irish-Italian Catholic with a funny accent; it’s too early for the country to really be ready for this. Historians still debate whether Hoover and/or his campaign deserves blame for being racist or credit for being surprisingly non-racist-under-the-circumstances.

The main issue is Prohibition. Smith, true to his roots, is against. Hoover, true to his own roots (his mother was a temperance activist) is in favor. The country is starting to realize Prohibition isn’t going too well, but they’re not ready to abandon it entirely, and Hoover promises to close loopholes and fix it up. Advantage: Hoover.

The second issue is tariffs. Everyone wants some. Hoover promises that if he wins, he will call a special session of Congress to debate the tariff question. Advantage: Hoover.

The last issue is personality. Republican strategists decide the best way for their candidate to handle his respective strengths and weaknesses is not to campaign at all, or be anywhere near the public, or expose himself to the electorate in any way. Instead, they are “selling a conception. Hoover was the omnicompetent engineer, humanitarian, and public servant, the ‘most useful American citizen now alive.’ He was an almost supernatural figure, whose wisdom encompasses all branches, whose judgment was never at fault, who knew the answers to all questions.” Al Smith is supremely charismatic, but “boasted of never having read a book”. Advantage: unclear, but Hoover’s strategy does seem to work pretty well for him. He racks up most of the media endorsements. TIME Magazine offers a rare dissent, saying that “In a society of temperate, industrious, unspectacular beavers, such a beaver-man would make an ideal King-beaver. But humans are different.”

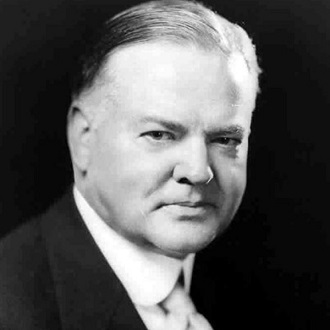

Apparently not that different. Hoover wins 444 votes to 87, one of the greatest electoral landslides in American history.

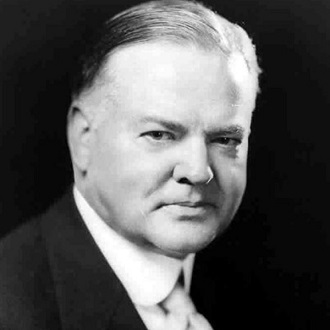

You may not like it, but this is what peak presidentialness looks likeAnne McCormick of the

New York Times describes the inauguration:

We were in a mood for magic…and the whole country was a vast, expectant gallery, its eyes focused on Washington. We had summoned a great engineer to solve our problems for us; now we sat back comfortable and confidently to watch our problems being solved. The modern technical mind was for the first time at the head of a government. Relieved and gratified, we turned over to that mind all of the complications and difficulties no other had been able to settle. Almost with the air of giving genius its chance, we waited for the performance to begin.

IV.

Herbert Hoover spent his entire presidency miserable.

First, he has no doubt that the economy is going to crash. It’s been too good for too long. He frantically tries to cool down the market, begs moneylenders to stop lending and bankers to stop banking. It doesn’t work, and the Federal Reserve is less concerned than he is. So he sits back and waits glumly for the other shoe to drop.

Second, he hates politics. Somehow he had thought that if he was the President, he would be above politics and everyone would have to listen to him. The exact opposite proves true. His special session of Congress comes up with the worst, most politically venal tariff bill imaginable. Each representative declares there should be low tariffs on everything except the products produced in his own district, then compromises by agreeing to high tariffs on everything with good lobbyists. The Senate declares that the House of Representatives is corrupt nincompoops and sends the bill back in disgust. Hoover has no idea how to solve this problem except to ask the House to do some kind of rational economically-correct calculation about optimal tariffs, which the House finds hilarious. “Opposed to the House bill and divided against itself, the Senate ran out the remaining seven weeks [of the special session] in a debauch of taunts, accusations, recriminations, and procedural argument.” The public blames Hoover, pretty fairly – a more experienced president would have known how to shepherd his party to a palatable compromise.

Also, there are crime waves, prison riots, bootlegging, and a heat wave during which Washington DC is basically uninhabitable. Also, at one point the White House is literally on fire.

…and then the market finally crashes. Hoover is among the first to call it a Depression instead of a Panic – he thinks the new term might make people panic less. But in fact, people aren’t panicking. They assume Hoover has everything in hand.

At first he does. He gathers the heads of Ford, Du Pont, Standard Oil, General Electric, General Motors, and Sears Roebuck and pressures them to say publicly they won’t fire people. He gathers the AFL and all the union heads and pressures them to say publicly they won’t strike. He enacts sweeping tax cuts, and the Fed enacts sweeping rate cuts. Everyone is bedazzled:

The sweep and speed of Washington’s response to the crash, which gave the impression that Hoover had ‘thoroughly anticipated the debacle and mapped out the shortest road to recovery’, was hailed in the press as an entirely new approach to management of the nation’s economic affairs.” Herald-Tribune: “President Hoover’s prompt action to prevent the depression extending to business and industry saved the situation. The panic was checked in a few days. Wages were left unaffected, stabilization was insured; production was encouraged to continue as usual. This leadership was all the more notable, since it was practically the first of the sort ever to originate in the White House.

And:

Economic joined journalists in congratulating Hoover on what was easily the most sophisticated response to a major economic event by any administration. ‘For the first time in our history,’ wrote Keynesian forerunners William Foster and Waddill Catchings, ‘a president is taking aggressive leadership in guiding private business through a crisis.

Six months later, employment is back to its usual levels, the stock market is approaching its 1929 level, and Democrats are fuming because they expect Hoover’s popularity to make him unbeatable in the midterms. I got confused at this point in the book – did I accidentally get a biography from an alternate timeline with a shorter, milder Great Depression? No. I do think I accidentally got a biography by someone obsessed with defending Hoover at any cost and willing to stray into revisionist history to do it. As per Whyte, Hoover would take some brilliant and decisive action. Economists would praise him. The economy would start to look better. Everyone would declare the problem solved – especially Hoover, sensitive both to his own reputation and to the importance of keeping economic optimism high. Then for reasons totally outside the President’s control, the recovery would stall, or reverse, or something else would go wrong.

People are still debating what made the Great Depression so long and hard. Whyte’s theory, insofar as he has one at all, is “one thing after another”. Every time the economy started to go up (thanks to Hoover), there was another shock. Most of them involved Europe – Germany threatening to default on its debts, Britain going off the gold standard. A few involved the US – the Federal Reserve made some really bad calls. The one thing Whyte is really sure about is that his idol Herbert Hoover was totally blameless.

He argues that Hoover’s bank relief plan could have stopped the Depression in its tracks – but that Congressional Democrats intent on sabotaging Hoover forced the plan to publicize the names of the banks applying. The Democrats hoped to catch Hoover propping up his plutocrat friends – but the change actually had the effect of making banks scared to apply for funding and panicking the customers of banks that were known to have applied. He argues that the “Hoover Holiday” – a plan to grant debt relief to Germany, taking some pressure off the clusterf**k that was Europe – was a masterstroke, but that France sabotaged it in the interests of bleeding a few more pennies from its arch-rival. International trade might have sparked a recovery – except that Congress finally passed the Hawley-Smoot Tariff, the end result of the corruption-plagued tariff negotiations, just in time to choke it off.

Whyte saves his barbs for the real villain: FDR. If the book is to be believed, Hoover actually had things pretty much under control by 1932. Employment was rising, the stock market was heading back up. FDR and his fellow Democrats worked to tear everything back down so he could win the election and take complete credit for the recovery. The wrecking campaign entered high gear after FDR won in 1932; he was terrified that the economy might get better before he took office, and used his President-Elect status to hint that he was going to do all sorts of awful things. The economy got skittish again and obediently declined, allowing him to get inaugurated at the precise lowest point and gain the credit for recovery he so ardently desired.

For example: November 1932. Hoover has just lost the election, but is a lame duck until March. The European debt crisis flashes up again. Hoover knows how to solve it. But:

He had already met with congressional leaders and learned, as he had suspected, that they would not change their stance without Roosevelt’s support. Seized with the urgency of the moment, he continued to bombard his opponents with proposals for cooperation toward solutions, going so far as to suggest that Democratic nominees, not Republicans, be sent to Europe to engage in negotiations, all to no avail. Notwithstanding what editorialists called his “personal and moral responsibility” to engage with the outgoing administration, Roosevelt had instructed Democratic leaders in Congress not to let Hoover “tinker” with the debts. He had also let it be known that any solution to the problem would occur on his watch – “Roosevelt holds he and not Hoover will fix debt policy”, read the headlines. Thus ended what the New York Times called Hoover’s magnanimous proposal for “unity and constructive action”, not to mention his 12-year effort to convince America of its obligation and self-interest in fostering European political and financial stability…

During the debt discussions and to some extent as a result of them, the economy turned south again. Several other factors contributed. Investors were exchanging US dollars for gold as doubt spread about Roosevelt’s intentions to remain on the gold standard. Gold stocks in the Federal Reserve thus declined, threatening the stability of the financial sector…what’s more, the effectiveness of [Hoover’s bank support plan], which had succeeded in stabilizing the banking system, was severely compromised by [Democrats’] insistence on publicizing its loans, as the administration had warned. For these reasons, Hoover would forever blame Roosevelt and the Democratic Congress for spoiling his hard-earned recovery, an argument that has only recently gained currency among economists.

And:

Alarmed at these threats to recovery, Hoover pushed Democratic congressional leaders and the incoming administration for action. He wanted to cut federal spending, reorganize the executive branch to save money, reestablish the confidentiality of RFC loans, introduce bankruptcy legislation to protect foreclosures, grant new powers to the Federal Reserve, and pass new banking regulation, including measures to protect depositors…He was frustrated at every turn by Democratic leadership taking cues from the President-Elect…On February 5, Congress took the obstructionism a degree further by closing shop with 23 days left in its session.

In mid-February, there is another run on the banks, worse than all the other runs on the banks thus far. Hoover asks Congress to do something – Congress says they will only listen to President-Elect Roosevelt. Hoover writes a letter to Roosevelt begging him to give Congress permission to act, saying it is a national emergency and he has to act right now. Roosevelt refuses to respond to the letter for eleven days, by which time the banks have all failed.

Then, a month later, he stands up before the American people and says they have nothing to fear but fear itself – a line he stole from Hoover – and accepts their adulation as Destined Savior. He keeps this Destined Savior status throughout his administration. In 1939, Roosevelt still had everyone convinced that Hoover was totally discredited by his failure to solve the Great Depression in three years – whereas Roosevelt had failed to solve it for six but that was totally okay and he deserved credit for being a bold leader who tried really hard.

So how come Hoover bears so much of the blame in public consciousness? Whyte points to three factors.

First, Hoover just the bad luck of being in office when an international depression struck. Its beginning wasn’t his fault, its persistence wasn’t his fault, but it happened on his watch and he got blamed.

Second, in 1928 the Democratic National Committee took the unprecedented step of continuing to exist even after a presidential election. It dedicated itself to the sort of PR we now take for granted: critical responses to major speeches, coordinated messaging among Democratic politicians, working alongside friendly media to create a narrative. The Republicans had nothing like it; the RNC forgot to exist for the 1930 midterms, and Hoover was forced to personally coordinate Republican campaigns from his White House office. Although Hoover was good (some would say obsessed) at reacting to specific threats on his personal reputation, the idea of coordinating a media narrative felt too much like the kind of politics he felt was beneath him. So he didn’t try. When the Democrats launched a massive public blitz to get everyone to call homeless encampments “Hoovervilles”, he privately fumed but publicly held his tongue. FDR and the Democrats stayed relentlessly on message and the accusation stuck.

And third, Hoover was dead-set against welfare. However admirable his attempts to reverse the Depression, stabilize banking, etc, he drew the line at a national dole for the Depression’s victims. This was one of FDR’s chief accusations against him, and it was entirely correct. Hoover suspected that going down that route would lead pretty much where it led Roosevelt – to a dectupling of the size of government and the abandonment of the Constitutional vision of a small federal government presiding over substantially autonomous states. He decided it wasn’t worth it. So Herbert Hoover, history’s greatest philanthropist and ender-of-famines, would go down in history as the guy who refused to feed starving people. And they hated him for it.

V.

Some people might call Herbert Hoover a sore loser. But he argues that no, it’s totally reasonable for him to spend the rest of his life attacking FDR and trying to destroy his legacy.

His theory, explained in the countless books, pamphlets, and speeches that he spends his post-presidential life writing, is that FDR came from the same cloth as Hitler and Stalin. The miseries of the Great Depression, the centralizing tendencies of the age, the rise of mass media, and the collapse of republican virtue were combining all around the world in a monstrous reaction against the cause of liberty. “Daily,” wrote Hoover, “the world goes back to the regimentation of the Middle Ages, whether it be Bolshevism, Hitlerism, Fascism, or the New Deal.”

He has more! “[The New Deal] has no philosophy. It is sheer opportunism, a muddle of a spoils system, of reckless adventure, of unctuous claims to a monopoly of human sympathy, of greed for power, of a desire for popular acclaim and an aspiration to make the front pages of the newspapers.” He has more! “The New Deal has contributed to sapping our stamina and making us soft…the road to regeneration is burdensome and hard. It is straight and simple. It is a road paved with work and with sacrifice and consecration to the indefinable spirit that is America.”

He has more! He just keeps going like this, again and again. FDR, for his part, seems slightly befuddled. He tried offering Hoover a position coordinating the US effort to help war refugees – which Hoover turned down, assuming anything from FDR was a trick. Hoover just keeps shouting and fulminating and writing more and more books and pamphlets until FDR dies – which enrages Hoover, who wanted him to “live long enough to reap what he had sown”.

Whyte’s theory is that this period of Hoover’s life sowed the seeds for the modern conservative movement: “Modern American conservatism, conceived as an antidote to the New Deal, was born on December 16, 1937, with Hoover as its prophet and philosopher.” He doesn’t do much to back this theory up, and Hoover gets all of a paragraph in Wikipedia’s long History of conservativism in the United States. We are left to piece it together from a few mentions here and there – Hoover befriending and helping a young William F. Buckley, Hoover giving a key endorsement to Barry Goldwater, and of course the namesake Hoover Institution that he founded, funded, and guided until his death.

I have to admit this is a hole in my understanding. Smart people definitely say that modern American conservativism began with Buckley and Goldwater and their friends, but what does this mean? Hasn’t about half of America been conservative since the 1700s? Hasn’t a philosophy of small government, individual freedom, and capitalist economics been pretty fundamental to America since its beginning? I’m not sure, and without this knowledge I don’t feel qualified to judge Hoover’s role.

Hoover passes in 1964, ninety years old. He lived long enough to become a hero to a new brand of conservative who considered him an intellectual forebear, and through various acts of public service to win back the love of his country. He had not quite finished his magnum opus, Freedom Betrayed. In 2012, historians finally dug it up, revised it, and released it to the world. It turned out to be 957 pages of him attacking Franklin Roosevelt. Give Herbert Hoover credit: he died as he lived.

VI.

I’m sorry this review was so long. I couldn’t bear to make it any shorter. I find the whole story so fascinating, and I just regret I couldn’t include more. I didn’t even get a chance to mention the time Hoover rescued the US South from the Great Mississippi Flood, or the time he discovered ancient ruins in the jungles of Burma, the time a 71-year-old Hoover was called back into service by President Truman to solve another post-World-War famine, or the time he invented the new sport of Hooverball (now part of the popular CrossFit exercise program).

Herbert Hoover on a famine relief tour of Poland, along with some of the children he is helping.Hoover was a man who did everything wrong. He was the quintessential

High Modernist. He was arrogant, he was authoritarian, he didn’t listen to anyone, he put no effort into pleasing people or making his ideas more palatable. He never solicited stakeholders’ opinions. He lied like a rug, constantly and egregiously. He lived his life like a caricature of exactly the sort of person who should fail at philanthropy and become a horror story to warn future generations.

But he won anyway. He started from a measly few million dollars and beat out Rockefellers and Carnegies to become the most successful philanthropist in early 20th century history. Whyte’s estimate of 100 million lives saved seems much too high; there were only 100 million people in Europe total during the relevant period. But even during his own time, people universally credited him with saving millions. And he did it again and again and again. I didn’t even have space to talk about the time he saved the Southern United States from a giant flood, or half a dozen other impressive accomplishments. Maybe the rules are wrong. Maybe all of this stuff about how authoritarian approaches never work, and you need to let the people you are helping lead the way, is all just modern prejudices, and putting a brilliant and very rich engineer in charge of a hypercentralized organization is just as good as any other way of doing things.

But even this I find less interesting than his psychology. He combined a personal callousness with a love for all humanity. When he was inspecting mines in Australia, he fired the worst-performing X% of workers. One worker begged him to reconsider – he had a family to support. Hoover raised $300 for the man’s family – a lot of money at the time! Probably more than Hoover made in a month! – but fired him anyway. In 1932, when the Bonus Army marched on Washington, Hoover was adamant that he would not give these men – poor, starving veterans – a single cent more than they were entitled to by their existing benefits. But he also instructed his staff to go around to their encampments and give them food and supplies in secret.

Sometimes his stubbornness calls to mind the fictional Inspector Javert, who refuses to bend the law for any reason. In this model, Hoover sympathizes with everybody, but his honor forbids him to bend the rules in favor of underperforming employees or protesters who want more than their contracts entitle them to. But this picture of a hyper-honorable Hoover crashes into his constant willingness to lie, cheat, and bend the rules in his own favor. Sometimes his lies are for the greater good, like when he tells Britain that Germany is preparing to feed Belgium. Other times they seem entirely selfish, like his various Chinese mining scams. The best that can be said about Hoover is that if he decides a principle is involved, he sticks to it.

And this is actually really good! Again and again through the book, Hoover feels like the only person with a moral compass. When it is in everyone’s strategic interest to let Belgium starve, Hoover is the only one who is able to keep fixated on the potential human toll. When it is in everyone’s interest to let the USSR starve, only Hoover – despite his fanatical anti-communism – is able to stick to the frame where the Russians are human beings and politics is beside the point. When Americans are starving during the Great Depression…

…okay, Hoover totally dropped the ball on that one. In fact, one of his Democratic opponents wrote something about how maybe if unemployed American workers pretended to be Belgians, they could get Hoover’s sympathy. I don’t have a great explanation for this. But Hoover’s weak and inconsistent sympathies are often enough to let him outdo everyone else. Or at least, he is uncorrelated with everyone else and succeeds when they fail. Again and again Hoover is accused of treating people like numbers on a piece of paper. But if this is true, it seems to be linked to the reverse talent – the ability to remember that numbers on a piece of paper represent people, even when other people would rather forget.

I’m equally confused about Hoover’s politics, although it’s not really his fault. The whole era confuses me. The Progressives, Hoover’s own faction, seem clearly related to modern progressives. But they also give me more of a technophile, rationalist feel than their modern counterparts. Am I imagining things? If not, where did this go?

And how did Hoover so deftly merge his centralizing technocratic engineer side with his small-government individual-freedom pro-capitalism side? Maybe it wasn’t that deft? Maybe he started his life as a centralizing technocrat, then made a 180 after becoming a small-government individualist helped him dunk on FDR more effectively? But it didn’t feel that way. It felt like all of it was coming from some central set of core beliefs throughout his life.

My confusion here feels similar to my confusion about Tyler Cowen’s “state capacity libertarianism”. Creating a strong and effective state is certainly…a goal you can have. But I don’t understand the argument for calling this a libertarian project. At best, it’s a project not entirely opposed to libertarianism. Still, perhaps this is my ignorance. Cowen thinks that strengthening the state and instituting effective technocratic government can be allied to a small-government individualistic market-based philosophy. Whatever he’s smoking, maybe Herbert Hoover was smoking the same thing.

I get the impression that Kenneth Whyte is a bit of a revisionist historian, too sympathetic to his subject to tell his story the way everyone else does. But at least in Whyte’s telling, the Hoover presidency was a great missed opportunity, or at least a fulcrum of history. If a few key economic events had been a few months off in one direction or the other, FDR might have been a footnote to history, and a four-term President Hoover might have left an indelible mark on America. Instead of a New Deal, we might have gotten a optimistic small-government technocratic meritocracy that was able to merge the best aspects of a dying frontier America with the best aspects of the industrial age.

In one of the most poignant passages in the book, Commerce Secretary Hoover fires back at his socialist critics. He points out that of the top dozen US officials – the President, VP, and ten Cabinet Secretaries – eight, including himself, had begun as manual laborers and worked their way up. That was the America Hoover was working to defend. He lost, and now we have this shitshow. But it’s hard to begrudge him the attempt.