At the beginning of every year, I make predictions. At the end of every year, I score them. Here are 2014, 2015, and 2016.

And here are the predictions I made for 2017. Strikethrough’d are false. Intact are true. Italicized are getting thrown out because I can’t decide if they’re true or not.

WORLD EVENTS

1. US will not get involved in any new major war with death toll of > 100 US soldiers: 60%

2. North Korea’s government will survive the year without large civil war/revolt: 95%

3. No terrorist attack in the USA will kill > 100 people: 90%

4. …in any First World country: 80%

5. Assad will remain President of Syria: 80%

6. Israel will not get in a large-scale war (ie >100 Israeli deaths) with any Arab state: 90%

7. No major intifada in Israel this year (ie > 250 Israeli deaths, but not in Cast Lead style war): 80%

8. No interesting progress with Gaza or peace negotiations in general this year: 90%

9. No Cast Lead style bombing/invasion of Gaza this year: 90%

10. Situation in Israel looks more worse than better: 70%

11. Syria’s civil war will not end this year: 60%

12. ISIS will control less territory than it does right now: 90%

13. ISIS will not continue to exist as a state entity in Iraq/Syria: 50%

14. No major civil war in Middle Eastern country not currently experiencing a major civil war: 90%

15. Libya to remain a mess: 80%

16. Ukraine will neither break into all-out war or get neatly resolved: 80%

17. No major revolt (greater than or equal to Tiananmen Square) against Chinese Communist Party: 95%

18. No major war in Asia (with >100 Chinese, Japanese, South Korean, and American deaths combined) over tiny stupid islands: 99%

19. No exchange of fire over tiny stupid islands: 90%

20. No announcement of genetically engineered human baby or credible plan for such: 90%

21. EMDrive is launched into space and testing is successfully begun: 70%

22. A significant number of skeptics will not become convinced EMDrive works: 80%

23. A significant number of believers will not become convinced EMDrive doesn’t work: 60%

24. No major earthquake (>100 deaths) in US: 99%

25. No major earthquake (>10000 deaths) in the world: 60%

26. Keith Ellison chosen as new DNC chair: 70%

EUROPE

27. No country currently in Euro or EU announces new plan to leave: 80%

28. France does not declare plan to leave EU: 95%

29. Germany does not declare plan to leave EU: 99%

30. No agreement reached on “two-speed EU”: 80%

31. The UK triggers Article 50: 90%

32. Marine Le Pen is not elected President of France: 60%

33. Angela Merkel is re-elected Chancellor of Germany: 60%

34. Theresa May remains PM of Britain: 80%

35. Fewer refugees admitted 2017 than 2016: 95%

ECONOMICS

36. Bitcoin will end the year higher than $1000: 60%

37. Oil will end the year higher than $50 a barrel: 60%

38. …but lower than $60 a barrel: 60%

39. Dow Jones will not fall > 10% this year: 50%

40. Shanghai index will not fall > 10% this year: 50%

TRUMP ADMINISTRATION

41. Donald Trump remains President at the end of 2017: 90%

42. No serious impeachment proceedings are active against Trump: 80%

43. Construction on Mexican border wall (beyond existing barriers) begins: 80%

44. Trump administration does not initiate extra prosecution of Hillary Clinton: 90%

45. US GDP growth lower than in 2016: 60%

46. US unemployment to be higher at end of year than beginning: 60%

47. US does not withdraw from large trade org like WTO or NAFTA: 90%

48. US does not publicly and explicitly disavow One China policy: 95%

49. No race riot killing > 5 people: 95%

50. US lifts at least half of existing sanctions on Russia: 70%

51. Donald Trump’s approval rating at the end of 2017 is lower than fifty percent: 80%

52. …lower than forty percent: 60%

COMMUNITIES

53. SSC will remain active: 95%

54. SSC will get fewer hits than in 2016: 60%

55. At least one SSC post > 100,000 hits: 70%

56. I will complete an LW/SSC survey: 80%

57. I will finish a long FAQ this year: 60%

58. Shireroth will remain active: 70%

59. No co-bloggers (with more than 5 posts) on SSC by the end of this year: 80%

60. Less Wrong renaissance attempt will seem less (rather than more) successful by end of this year: 90%

61. > 15,000 Twitter followers by end of this year: 80%

62. I won’t stop using Twitter, Tumblr, or Facebook: 90%

63. I will attend the Bay Area Solstice next year: 90%

64. …some other Solstice: 60%

65. …not the New York Solstice: 60%

WORK

66. I will take the job I am currently expecting to take: 90%

67. …at the time I am expecting to take it, without any delays: 80%

68. I will like the job and plan to continue doing it for a while: 70%

69. I will pass my Boards: 90%

70. I will be involved in at least one published/accepted-to-publish research paper by the end of 2017: 50%

71. I will present a research paper at the regional conference: 80%

72. I will attend the APA national meeting in San Diego: 90%

73. None of my outpatients to be hospitalized for psychiatric reasons during the first half of 2017: 50%

74. None of my outpatients to be involuntarily committed to psych hospital by me during the first half of 2017: 70%

75. None of my outpatients to attempt suicide during the first half of 2017: 90%

76. I will not have scored 95th percentile or above when I get this year’s PRITE scores back: 60%

PERSONAL

77. Amazon will not harass me to get the $40,000 they gave me back: 80%

78. …or at least will not be successful: 90%

79. I will drive cross-country in 2017: 70%

80. I will travel outside the US in 2017: 70%

81. …to Europe: 50%

82. I will not officially break up with any of my current girlfriends: 60%

83. K will spend at least three months total in Michigan this year: 70%

84. I will get at least one new girlfriend: 70%

85. I will not get engaged: 90%

86. I will visit the Bay in May 2017: 60%

87. I will have moved to the Bay Area: 99%

88. I won’t live in Godric’s Hollow for at least two weeks continuous: 70%

89. I won’t live in Volterra for at least two weeks continuous: 70%

90. I won’t live in the Bailey for at least two weeks continuous: 95%

91. I won’t live in some other rationalist group home for at least two weeks continuous: 90%

92. I will be living in a house (incl group house) and not apartment building at the end of 2017: 60%

93. I will still not have gotten my elective surgery: 90%

94. I will not have been hospitalized (excluding ER) for any other reason: 95%

95. I will make my savings target at the end of 2017: 60%

96. I will not be taking any nootropic (except ZMA) daily or near-daily during any 2-month period this year: 90%

97. I won’t publicly and drastically change highest-level political/religious/philosophical positions (eg become a Muslim or Republican): 90%

98. I will not get drunk this year: 80%

99. I get at least one article published on a major site like Huffington Post or Vox or New Statesman or something: 50%

100. I attend at least one wedding this year: 50%

101. Still driving my current car at the end of 2017: 90%

102. Car is not stuck in shop for repairs for >1 day during 2017: 60%

103. I will use Lyft at least once in 2017: 60%

104. I weight > 185 pounds at the end of 2017: 60%

105. I weight < 195 pounds at the end of 2017: 70%

Some justifications for my decisions: I rated the civil war in Syria as basically over, even though Wikipedia says otherwise, since I don’t think there are any remaining credible rebel forces, and ISIS is pretty dead. Trump’s approval rating is taken from this 538 aggregator and is currently estimated at 38.1%. I rated the border wall as not currently under construction, despite articles with titles like The Trump Administration Has Already Started Building The Border Wall, because it was referring to a 30-foot prototype not likely to be included in the wall itself (have I mentioned the media is terrible?). I refused to judge the success of the Less Wrong renaissance attempt, because it seemed unsuccessful but was superseded by a separate much more serious attempt that was successful and I’m not sure how to rate that. I refused to judge whether or not I got a new partner because I am casually dating some people and not sure how to count it. I refused to judge whether I got 95th percentile+ on my PRITE because they stopped clearly reporting percentile scores.

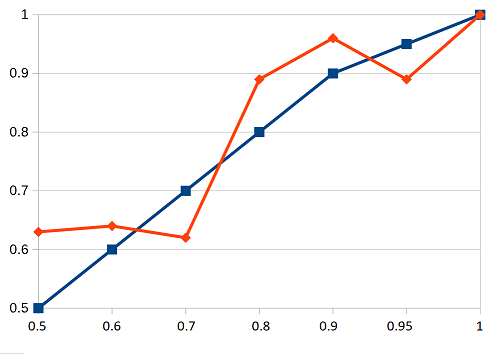

This is the graph of my accuracy for this year:

Of 50% predictions, I got 5 right and 3 wrong, for a score of 62%

Of 60% predictions, I got 14 right and 8 wrong, for a score of 64%

Of 70% predictions, I got 8 right and 5 wrong, for a score of 62%

Of 80% predictions, I got 16 right and 2 wrong, for a score of 89%

Of 90% predictions, I got 24 right and 1 wrong, for a score of 96%

Of 95% predictions, I got 8 right and 1 wrong, for a score of 89%

Of 99% predictions, I got 4 right and 0 wrong, for a score of 100%

Blue is hypothetical perfect calibration, red is my calibration. The multiple crossings of the blue line indicate that I am neither globally overconfident or globally underconfident.

Last year my main concern was that I was underconfident at 70%. I tried to fix that this year by becoming more willing to guess at that level, and ended up a bit overconfident. This year I’ll try somewhere in the middle and hopefully get it right.

There weren’t enough questions to detect patterns of mistakes, but there was a slight tendency for me to think things would go more smoothly than they did. I overestimated the success of my diet, my savings plan, my travel plans my job start date, my long-FAQ-making ability, and my future housing search (this last one led to me spending a few weeks at a friend’s group house, failing on a 95% certainty prediction). I only made one error in favor of personal affairs going better than expected (SSC got more hits than last year; maybe this isn’t a central example of “personal affairs going smoothly”). None of these really caused me any problems, suggesting that I have enough slack in my plans, but apparently I’m not yet able to extend that to being able to make good explicit predictions about.

My other major error was underestimating the state of the US economy, leading to a couple of correlated errors. I think I got Trump mostly right, although I may have overestimated his efficacy (I thought he would have started the border wall by now) and erred in thinking he would lift sanctions on Russia.

Otherwise this is consistent with generally good calibration plus random noise. Next year I’ll have played this game five years in a row, and I’ll average out all my answers for all five years and get a better estimate; for now I’ll just be pretty satisfied.

Predictions for 2018 coming soon.

…the Kurds and Kurdish-aligned militias are still around and control significantly more of the country than they did before. The non-Kurdish rebel forces haven’t really lost much ground at all in the last year. See this tweet for percentages.

That tweet seems to be remarking on how much change there was in the past year, and claims the government has gained 39.5% more territory. It also supports Scott’s claim that ISIS is pretty dead.

I’d rather know percentages of population, not land. Surely the Opposition is fragmented because people are?

It is possible that in retrospect we will consider the war to have ended by now without a formal agreement because fighting peters out, especially Assad vs Kurds. But I doubt that will happen.

You mean the non-Kurdish non-Daesh rebel forces (or to put it another way, the non-Kurdish non-Daesh non-Assad forces). Or you could simply say the non-Daesh forces, since the Kurdish-aligned and Assad-commanded forces haven't lost much either (inasmuch as they have gained).

Yeah, there are a lot of areas under control of a lot of various forces, but is there any major fighting going on?

That is after all what makes a war.

As i pointed out in a post below, the Syrian Arab Army is currently conducting a major offensive to retake Idlib Governorate from rebel forces. It cannot be said that major fighting has ended until that offensive concludes.

Even so, looking at how much territory was held by ISIS, it does seem as though the Syrian regime reasserting control was the (most likely) lesser evil of outcomes. Perhaps the Kurds are an even lesser evil, but I’m not sure if they can win if they decide to go on the offensive now, and they may be content to hold that territory, given their separatist ideology. The regime might not let them keep it in the long term though, so if the opposition is mopped up (and it looks like it will be given they are only holding the same territory while the regime has expanded to take all that ISIS territory back), then the Kurds may not be far behind. Fighting will probably resume at some point.

The Kurds are happy to hold on to the Kurdish areas and have no interest in ruling all of Syria.

As I understand it, they’re currently protected by the US, but she can be a fickle ally.

The long term game for Syria is impossible to predict, but with both Turkey, Russia, Iran, USA having fighting troops there on top of the local Assad, Kurds, ISIS, Al Qaeda, many local militias, and why not also Iraq, it’s hard to be optimistic about a quick and just peace.

It should be noted that the kurds/SDF/’democratic federation of nothern syria’ is focused on a broader ideology than kurdish interests (worth researching if you want to understand the goals of the movements there) & has been gunning for some kind of autonomy/federalism arrangement with the syrian government for some time now.

The Kurds and Kurdish-aligned militias have always(*) been around and quietly controlling otherwise-forgotten chunks of Syria, Iraq, Iran, and Turkey without really bothering anyone. That doesn’t mean all four nations are engaged in perpetual civil wars. And civil wars almost always end with violence undergoing an exponential decay over a period of years; Robert E. Lee convincing everyone to knock it off and go home is an extreme outlier. A sophisticated prediction of “Civil War X will end” would include careful hedging about ongoing insurgency, but if you’re going to limit it to the Syrian war being “over”, Y/N, it’s basically over.

* For modest generations of “always”, but at least a generation

There are still large scale conventional combat operations being conducted by the SAA against Ahrar al-Sham and Tahrir al-Sham in the Northwest. Only when those conclude can we say the war is over, in the sense that it will have wholly shifted to playing whack-a-mole with insurgents. That is assuming the Assadists and the Kurds don’t suddenly decide to throw down, but i would give that low probability.

CFAR often claims most people are poorly calibrated, and one of the touted benefits of lesswrong-style rationality is becoming better calibrated. You seem especially well calibrated. Has it helped you? Is calibration worth working on for the bulk of us that are poorly calibrated? Could you make predictions, trade on them, and out perform the market? Or maybe work as a venture capitalist if that market is less efficient?

Angela Merkel is still the chancellor of Germany as a caretaker, but it remains unclear if she will remain so permanently, pending coalition talks so I am not sure if it is known that she “is reelected Chancellor.”

Yes; if she doesn’t end up being chancellor, I think it’d be appropriate to go back and change the data retroactively. If she does, it’s fine.

Also, if you want to take the prediction literally, she has not been re-elected in 2017 because no such election has taken place.

I would indeed take the prediction literally here. A failure to know the pitfalls of how exactly a German Chancellor is elected before making a predictions is still a failure to predict an outcome. If his prediction had been “Angela Merkel will stay Chancellor throughout 2017” he would’ve been right of course, even if, for example, the SPD had won a plurality and their coalition talks had failed to reach an agreement before the end of 2017.

Otherwise, this prediction here would basically mean “Scott foresaw the first coalition talks failing, but then also the SPD caving later on and then elect Merkel Chancellor sometime in 2018”.

At least declare it uncallable right now and then edit once Merkel is confirmed again (which is likely, but not a done deal). Or put your prediction of these talks right now and/or a predictions of how likely a snap election is gonna be and, if that one takes place, which party will win a plurality in the 2018 predictions.

I think that it’s improper to state the Syrian Civil War has already ended; you should at least make that italic. Personally, I would cross it out. Things are going so well there that we can predict with high confidence an end in 2018, even in early 2018, but there are still belligerents on the ground who have not acceded to a cease-fire. It’s unlikely, but Daesh or another of the many forces that still control a tiny amount of territory might regroup, or fighting might break out over the status of Rojava, which has peaceful ambitions but controls extensive territory that Assad wants to regain.

In particular, there has been fighting in Harasta between the Syrian government army and Al Qaeda affiliates/allies in 2018. It’s minor, but I don’t see how you can say that this is not part of the Syrian Civil War; such battles were a routine part of the war in 2017. It may be the last gasp of groups that have already lost, but it’s not Hiroo Onada taking potshots at the Philippine police; it’s a continuation of the same fighting that we saw before.

I meant to say that I would count your prediction correct, not that I would cross it out (counting it wrong). (I forgot which way you predicted it when I wrote that.)

I disagree that we can be very confident that the Syrian civil war will end in 2018, and I would bet against it given 4:1 odds in my favor.

Now you're making me sad. :–(

What happened with Amazon?

Yeah. In my experience, it is very much the other way round — buy anything form them, and they suck money our of your account forever.

I was picking up a few hundred dollars a month from my affiliate account, until one month I inexplicably got $40,000. I looked for plausible explanations and came up empty. I told Amazon, saying it was probably a mistake, and they said “whatever” and let me keep it.

Of 50% predictions, I got 5 right and 3 wrong, for a score of 62%

Of 60% predictions, I got 14 right and 8 wrong, for a score of 64%

Of 70% predictions, I got 8 right and 5 wrong, for a score of 62%

Of 80% predictions, I got 16 right and 2 wrong, for a score of 89%

Of 90% predictions, I got 24 right and 1 wrong, for a score of 96%

Of 95% predictions, I got 8 right and 1 wrong, for a score of 89%

Of 99% predictions, I got 4 right and 0 wrong, for a score of 100%

This is quite a bit like how NFL field goal kickers are evaluated. E.g. Greg Zuerlein made 6 of 7 field goal attempts from 50 yards or further, 12 of 12 from 40 to 49, 11 of 12 from 30-39, 8 of 8 from 20-29, and 1 of 1 from 10-19 yards:

Player Team PAT FG 0-19 20-29 30-39 40-49 50+ Lg Pts

Greg Zuerlein LA 44/46 38/40 1/1 8/8 11/12 12/12 6/7 56 158

NFL field goal kickers’ stats look strikingly like Scott’s predictions.

Nobody seems exactly sure how to weight placekickers’ performances, however.

There isn’t much interest in the media over who is the best NFL placekicker, in part because field goal percentages are so extremely high.

One problem that keeps kickers from becoming famous celebrities is that they don’t take many longshot kicks from beyond a point where they have about a 50% chance of making it. In contrast, way back in 1970 placekicker Tom Dempsey was sent out on the last play of the game to attempt a 63 yard field goal. The coach had gotten confused about where the ball was and later admitted he wouldn’t have sent Dempsey out if he’d known. But Dempsey who was born with no toes on his kicking foot, made the 63 yarder to win the game. This remained a record for longest field goal in the NFL until only a few years ago. Dempsey, unlike most placekickers, was famous.

Similarly, this kind of calibration forecasting doesn’t get much attention because Scott isn’t attempting any 63 yarders. In fact, he argues that he logically can’t make a prediction with less than a 50% chance of coming true. This tends to take a lot of the excitement out of reading about his impressive results.

What would attempting 63 yarder prediction even look like? Are you trying to say it would be impressive if if Scott tried to predict something with a 10% likelihood and it ended up happening? If that happened a lot it would indicate poor prediction abilities, not good ones.

I think you forget that every prediction >50% has an implicit opposite prediction of <50%.

If you predict that an event has a 10% chance of occurring, even though the consensus is that it is only 1% likely.

Consensus calibration isn’t available – if it was, then a lot of Scott’s predictions may well be “63-yarder” predictions.

That’s why the 2018 predictions should come with a survey where SSC readers can give their own estimate. And perhaps we could also vote on our own questions for Scott to predict (maybe on the subreddit or something, so we can vote).

Adding more descriptors to each prediction would make it more impressive. A “20 yarder” is saying that Le Pen won’t get elected. A “40 yarder” is predicting that Le Pen would not get elected by losing in the 2nd round of voting. The 63 yarder of this is predicting that Le Pen loses in the second round to Emmanuel Macron.

I was thinking something like this.

It’s not very fair that you get to choose the questions that you answer.

“I predict with 99% certainty that gravity will still be around in one year.”

One year passes.

“Oh wow I’m such an accurate predictor. My prediction was correct.”

To be statistically significant with just 99% predictions, you’d need to make many hundreds of them, and you’d be a poor predictor if they all came true. You’d need at least three or four of (gravity still works, relativity still works, sun still rises in the East, hundreds more like it) to fail, to count as well-calibrated, if that’s your game.

Not sure that four 99%-level predictions in a mix of less confident claims has that much power either; most of the significance is going to come from the 70-90% level predictions. But if you’re going to start with a list of questions and find that, on analysis, some do come in at the 99% level, it’s intellectually honest to include them anyway.

What John said about 99%, plus I don’t think that Scott is trying to play a game that he’s playing unfairly. (Your not being invited to compare your score with Scott’s, for example.) He’s making predictions about things that he’s interested in, like anybody might do, and then he’s adding something to that: he’s stating his confidence and checking his calibration. It’s reasonable to check that with the predictions that he would have made anyway.

If he’s not comparing his predictions against anyone else’s predictions, what does he learn?

Maybe they were all very easy predictions. Maybe if you asked random people to make predictions about the same questions, Scott would actually score lower than average. How can he learn anything about his own prediction ability without that information?

What would “easy question” even mean? The point in this game is not to be right or wrong about the predictions but to be right or wrong about your calibration. Predicting that gravity still exists in 2019 at only 99% probability would mean you’re very poorly calibrated. You should also note that Scott didn’t actually make any 99% predictions, because as John said, you’d have to make a lot of them to get significant results.

I don’t see what this has to do with your complaints about unfairness. But anyway, I believe that he’s comparing himself to his own past years with the goal of personal improvement.

Thanks for all comments.

Here’s one way to have a forecasting tournament that would be pretty exciting. Pit two celebrity forecasters, e.g., Scott versus Philip Tetlock or Nate Silver, against each other. The really interesting event would be at the beginning when decide who will bet on what. Give them a list of 100 forecasts for 2018 drawn up by a neutral party. Let them bid against each other to see who would go further out on a limb on each question.

For example, say that both agree that the Democrats will pick up seats in the 2018 House election. Scott bids that he bets the Democrats will pick up at least 30 seats. His opponent counters with the Democrats picking up at least 35 seats. Scott counters with at least 38 seats. His opponent thinks about one-upping this bet, but then decides to let Scott have it: if the Democrats pick up 38 or more seats, Scott wins; 37 or fewer and his opponent wins.

Alternatively, the third party could propose a bet over whether the Democrats will pick up at least 30 seats. Scott bids that he’ll take that bet with a 60% probability. His opponent offers 65%. Scott counters with 68% and his opponent lets him have it.

To be an exciting (not just accurate) predictor, you have to predict events that most other people think are low confidence, with high confidence, and be correct.

The Islamic State may be dead, but Ahrar al-Sham, Tahrir al-Sham, and what remains if the the Free Syrian Army still hold the entirety of Idlib Governorate, as well as parts of the Hama and Aleppo Governorates. The Syrian Arab Army is conducting a major offensive against them as we speak. It beggars belief to declare the war over when they are ongoing combat operations involving tens of thousands of men that will very likely take months to resolve. The original prediction was correct, the Syrian Civil War is not over yet.

I’m not sure if I’d have had the confidence to predict this in advance, but it seems like Trump isn’t effective AT ALL: the bad things he does mostly to be, dismantling stuff, and allowing republican congress to pass bad stuff. Which might be even worse than if he was committed to something specific, I’m not sure 🙁

I love reading about the calibration process, you do it well.

I missed ISIL being basically over! 🙁 I guess that itself is better than the alternative, although going back to Asad status quo isn’t great. Fewer proxy wars pls 🙁

You never hear about bad things ending, do you? You just sort of stop hearing about them, which can be either because they stopped, or just because the media lost interest.

It’s like with the economy. The first I ever hear of the economy being good is when someone reports that the economy, after having been good for a while, is now bad again. No one ever tells me that the economy is good right now.

If you think the media doesn’t report when the economy’s doing well, then you’re clearly not paying attention. They started doing so late 2015. Then there’s this from year and a half ago, discussing how people are still anxious about the economy even though it’s been doing great. And just yesterday the New York Times reported that the markets are booming. We’ve been having good economic news for two years now, so maybe the problem is not the reporting, but that you don’t notice it.

Well, they sure manage to make me notice their laments of “things are worse than ever! Threat of homelessness and starvation imminent!” every five years or so, so at the very least they must be a lot louder with it! :p

But it’s nice to hear that the markets are apparently booming at the moment.

It’s reported, but never as major news. You have to read the whole paper/website to learn about it.

It’s selection bias of what they choose to report and focus on, and how they report it. The media in general only focuses on bad news, but places like the NYT can be counted on to downplay anything that touches on the culture wars that doesn’t fit their narrative. One can always try to imagine how they would report the rise of ISIS if it happened while Trump was in office, alas we cannot run alternate universes for a fact check.

This type of reporting is typical.

Is that being ineffective? The stuff the Republican congress is passing may not be stuff you like, but it’s in line with what Republicans like. Destroying ISIS is a major victory which he deserves a lot of credit for.

And it’s worth remembering that Scott’s expectations of an economic downturn now were pretty mainstream at the time. Pundits speculated in a kidding-not-kidding way that both parties were trying to throw the presidential election so they wouldn’t get blamed for the oncoming recession.

“But Trump didn’t do anything to help the economy!” you say. Ah, but that’s the genius of it. The economy has grown beyond all expectations at precisely the same time the left has been saying “the Republicans haven’t passed any major legislation!” Trump is providing empirical proof that the government governs best when it governs least.

Ladies and gentlemen, I give you Donald Trump: the first libertarian president.

“Destroying ISIS is a major victory which he deserves a lot of credit for.”

lol

What did Donald Trump do to destroy ISIS, beyond not getting in the way of Russia and Iran destroying ISIS?

Changing the rules of engagement and giving commanders in field more decision making capability. Mattis claimed the strategy is now “annihilation tactics”. Bombing rates have increased even as ISIS’s footprint has decreased. A BBC article stated they were dropping bombs on single militants.

The BBC covered these battles much more comprehensively than any outlet in the US. Example.

Exactly how much difference this all makes and whether it qualifies as “bombing the shit out of ISIS” is unclear. What is clear are the results, Raqqa was basically flattened.

The US bombing the crap out of someplace and declaring victory has a long history, but a very poor correlation with anything resembling actual victory. The very first post in this topic included a link to a map of who actually controls Syria this year vs. last. Most of the territory that ISIS lost, was taken by the Russian-backed Syrian regime. The rest fell to the Kurds. Over the border, it was mostly the Iranian-backed Iraqi regime with a side order of Kurds. The US dropped some bombs, flattened mostly-abandoned buildings and said “we’re helping!”. Feel free to cheer for Donald Trump if you wish.

You asked: “What did Donald Trump do to destroy ISIS?”. I answered the question, not cheering for anybody. The US never had any intention of occupying Syria and has given up on removing Assad, these questions are moving the goalposts.

If you don’t think dropping 200 bombs and missiles per day on the self declared capital of ISIS wasn’t “helping” I guess you can choose to believe that. They weren’t dropping bombs on empty buildings, they were dropping bombs on people shooting from empty buildings.

The ideology of ISIS will live on, as far as them having dreams of being a nation state that evolves to a global caliphate, that has been destroyed. We will see what the future brings.

You stated that Donald Trump deserved a lot of credit for defeating ISIS, which A: is pretty much cheering and B: implies that his efforts were decisive or nearly so.

Bombing ISIS holdouts in a mostly-abandoned city is not decisive, did not destroy ISIS, and isn’t worth cheering. Bombing ISIS generally, if you’re only willing to do it where there is no chance of civilian or friendly-fire casualties and not willing to follow it up with ground troops, is not decisive and isn’t going to destroy ISIS. To the extent that it is useful at the margin and/or designed to evoke cheers beyond the magnitude of the accomplishment, it is something Barack Obama was doing for literally years before Donald Trump was elected.

Maybe the USAF dropped more bombs on ISIS under Donald Trump than under Barack Obama. Maybe the RCAF dropped more bombs on Al Qaeda under Stephen Harper than under Paul Martin; that doesn’t get Harper “a lot of the credit” for defeating Al Qaeda.

Staying out of the way is underrated as a strategy, and exactly what you’d expect from the first libertarian president.

Eh? Trump’s main domestic policies thus far have involved strengthening the police, giving them more military grade weapons, pushing for increased immigration restrictions, encouraging ICE to be more aggressive, ect. His AG is strongly against legalizing marijuana. Overall Trump seems like a classic “lock them up/ build a wall/ law and order/ make the military bigger” big government conservative, the type who wants to strengthen the police and military aspects of governance; pretty much the opposite of a libertarian.

REEFER MADNESS, and multi billion dollar wall-shaped pyramids are both very libertarian issues.

Even if that’s all that he did, it’s still better than any other President would have done.

Yeah no, i will confidently say that every single person who ran in 2015 would have done the same thing. Just think about this for a second. The first time the President-Elect gets briefed about Daesh, s/he’s going to get told that we’ve already got a strategy, and it’s been working. What do you think happens next? President-Elect nods his or her head, and tells them to keep up the good work.

The only candidate in the entire field who i could picture trying to foist some crazy sonbitch plan on the Joint Chiefs is Donald Trump. Except not even he did that, what he actually did was appoint St. Mattis for SecDef and let him handle it. The worst case scenario is President Sanders is hesitant to engage in as vigorous a bombing campaign, and maybe Islamic State takes an extra couple months to be taken off the board in that instance.

Under the hypothesis that I’m working with (that the President did nothing but keep out of the way of forces led by others), even Sanders comes out fine. But actually I wasn’t thinking about Sanders, since Trump never ran against him. (Also not thinking about Johnson, Stein, etc, even though I voted for one of them.)

Maybe you’re right, and that’d be good for Presidents’ listening to reason. But Clinton promised a no-fly-zone, and I don’t trust any of the other Republicans not to have picked a similar fight with Assad.

Hell, I didn’t trust Trump (I don’t trust him about anything), I just hoped. And I gave up that hope on April 7! But apparently the Scott-Adams types were right about that, and Trump only did it to get the neocons off his back.

The 50% predictions are useless for calibration, as they could easily been stated as predictions for the exact opposite at 50%. Hence the percentage “correct” is basically a function of how you randomly chose which side to state as the positive side of the prediction.

There is some way to properly mathematically decide how good your prediction was, in a way which rates a 100% prediction coming true as good, a 50% prediction coming true as meaningless, and a 60% prediction at an appropriately discounted level. I don’t know it, Scott doesn’t seem to know it, most people here don’t know it, and it may or may not have been mentioned last year somewhere where I can’t find it.

We should find it and use it, not pretend that the analysis Scott used is meaningful. Roll-your-own-statistical-analysis is as bad as roll-your-own-cryptography.

Also, I complained about this very thing last year.

I’d argue that a 100% prediction coming true should also count for nothing, while a 100% prediction coming false should count infinitely bad. Never make a 100% prediction.

Scott isn’t analysing much. He’s drawing a curve that contains more information than the one number that you want to use, and in fact that number will be obtained by integrating some transformation of that curve. So reporting the curve can’t be wrong, in principle. (Except for the 50% score, since that contributes literally no relevant information.)

You don’t argue that. You find the statisticians who have studied how to do such things and you look it up, and nobody’s done that here. You don’t roll your own statistical analysis.

Also, your method would produce surprising results. If a successful 100% prediction doesn’t count and a successful 50% prediction doesn’t count, there must be some number between 50 and 100 where a successful prediction counts the most. I find this unlikely.

First of all, presentation matters. The curve looks very much like it’s supposed to carry useful information as is.

Second, Scott is analyzing it, and even if he isn’t literally putting a numeric value on it, he’s making a determination: “Otherwise this is consistent with generally good calibration plus random noise.” How does he know this without knowing how to analyze anything?

Maybe you don’t, but I’m a trained mathematician familiar with Bayesian philosophy. I’m perfectly capable of judging my contributions. (And I don’t have one; I spent a little time trying to come up with a good method of scoring and didn’t, but the important thing is that I knew that I didn’t.)

Also, I did try to look it up, but I don’t seem to have the right buzzwords. I might have to ask a statistician, but I’m hoping that one will just show up here!

Yeah, I noticed this too. I thought of 1/e (or 1 − 1/e in this case), which is the probability with the maximum expected surprisal. It doesn’t seem like such a special probability, but it turns out to maximize something interesting anyway. (But we’re not really talking about surprisal here, so that’s not probably not actually the maximizing number this time.)

Still, if the reason that you're calibrating your probabilities is to become more rational, and if rational people never make 100% predictions, then you shouldn’t get any reward for making a 100% prediction, even if it is correct. (At least that’s what I’m thinking; I’m not completely confident about that, ‘I'd argue’ is meant to solicit rebuttals, such as you offered.)

Also, if we are integrating some function of probabilities, then the maximum of that function is not necessarily that special. We could just as well measure things with odds or log odds, and integrate a function of those, and the maximum of that function would be different. (Not just in the trivial way that a probability is a different number from the equivalent odds or log odds, but in that the two numbers would not even be equivalent.)

It carries the relevant information, and it’s a natural representation that isn’t chosen to deceive. Even if the proper thing to do is to apply a transformation before integrating, I'd expect people to draw this curve first before drawing the other curve (if they have room). Doubly so if there are some different competing proposals for how to assign a score (which would not surprise me at all), with this curve intended to be the neutral representation.

Yeah, you’re right about that. I think that the curve is enough to make it clear that he's well-balanced between under-calibration and over-calibration, but we don’t have enough to say that the calibration is overall good or bad. Wildly fluctuating without an overall bias is still bad (it’s not enough to call it ‘random noise’ and forget about it), and maybe that’s what we have here.

I forgot to say, and don’t want it lost in the editing, that anything based on integrating the transformation of a curve really should only be applied to a set of independent predictions. (After all, if you double up a prediction, then that shouldn’t really change the score.) Otherwise, you really need to assign a score to the entire probability distribution over all possible combinations of outcomes, which Scott has not told us (and which would be exponentially more information that he has given us, so not practical).

I think that one could make a reasonable go at this, but not without manipulating the data beforehand. (Even throwing out the obvious cases where one prediction is logically entailed by the next, there are subtler correlations when the topics are related, for example when two predictions both state that the economy is doing well or badly.)

And you didn’t either. Which is entirely proper!

Someone on reddit pointed out Brier scores which sounds like it might fit.

I think at least part of the answer is that getting a 50% prediction correct doesn’t provide no information. If you make one 50% prediction and get it correct that can’t provide any information. But if you make 20 50% predictions and get 10 of them correct, that’s a sign that you’re well calibrated.

This paper from the Monthly Weather Review (The Discrete Brier and Ranked Probability Skill Scores) may be useful. It explains the standard scoring methods used to grade weather prediction methods.

I didn’t what? I made an argument about one aspect of the situation, and you replied that I shouldn’t, and I replied that I am allowed to.

Yes, that looks interesting! And now I know the buzz word search for, which is ‘scoring rule’. There’s others besides the Brier rule, and I’ll have to think about which (if any) is the right way to do this.

I have a comment about the 50% predictions too, but I’m going to make it in another part of this thread.

You take the log of the probability, and that’s your score. If you estimate 80%, and you’re right, your penalty is log(0.8), if you’re wrong, it’s log(1 – 0.8). It’s doesn’t really matter what the base of the log is.

The goal is to have the highest score. Scores are always negative, unless you estimate 100% and you’re right – then your score is 0, which is the highest possible score. If you’re wrong, your score is minus infinity, and you may never play again. Never make a 100% prediction.

This isn’t measuring what we want to measure. For example, if Scott makes 4 predictions, all at 75%, then the best score should come when 3 are correct and 1 is wrong. But this measure gives the best score when all are correct. This is more of a correctness-of-predictions score than correctness-of-calibration score.

You’re talking about assigning a loss function for predictions.

Scott is drawing a calibration graph.

Both are fine and frequently used in the relevant literature.

Don’t accuse people of ignorance if you don’t know the subtleties yourself.

Scott is drawing a conclusion, not just drawing a graph.

Scott, do you have any response to this? This has been brought up in the calibration threads for as long as I’ve been reading SSC, and it seems very clear that it renders the 50% calibrations meaningless. Do you disagree with the arguments that have been presented, or is there some other reason why you continue to include 50% predictions?

How about 50% predictions that contradict the conventional wisdom? If most pundits give a candidate a 10% chance of winning, and you give him 50% (and you do this repeatedly and are right half the time) you are on to something.

Sure, but the noteworthy part of that isn’t that you’re well-calibrated at 50%. The noteworthy part is that you’re apparently a much more accurate predictor than the pundits. In the scenario you described, I’d be pretty impressed even if your predictions happened 90% of the time.

If that’s the case, you aren’t randomly framing them, so the criticism doesn’t apply.

They’re absolutely useful. If you try to make 10 guesses at the 50% error rating and 8 turn out to be true, you’re probably not calibrating 50% very well. The point of calibration is having a good sense of when things are 50% likely vs some other probability, so being accurate at the 50% level is a part of that.

The problem with the 50% predictions is that every time you predict “50% chance of A”, you’re also predicting “50% chance of ~A”. If my 50% predictions are actually 80% likely to come true, that’s going to result in my predictions of A coming true at 80% and my predictions of ~A coming true at 20%, which will cancel out to an overall success rate of 50%.

Given that Scott’s actual predictions will be a mix of A and ~A (because it’s basically random whether he happens to phrase a 50% prediction as “War in Syria” or “No war in Syria”), his 50% predictions will come true roughly 50% of the time, no matter what he predicts.

I’m not sure if I’m explaining this well, but I’m almost positive that I’m correct. If you want to see empirical evidence of this, take any list of predictions, and flip half of them (so that a prediction of “War in Syria” becomes “No war in Syria” and vice versa). If you do that with a large enough number of predictions, you will end up with 50% of them being correct. Unless you have a principled way of deciding whether to predict A or ~A (and I don’t think that’s realistic for a 50% prediction), that’s going to happen all the time.

Look at it this way: if you say:

1. X has 80% probability

you could next say

2. ~X has 20% probability

And we could score those two statements (and others like that). It would be redundant but not meaningless.

But if 1 and 2 say 50% the whole thing is meaningless.

In your scenario, if you’re perfectly calibrated, you’ll get 80% of the X’s right and 20% of the ~X’s right, for perfect calibration at 80% and 20%. The difference in my scenario is that, at 50%, both the X’s and the ~X’s are counted toward the same score.

Actually, upon re-reading your last line, I’m not sure if you’re agreeing or disagreeing with me.

So if you say there is a 50% chance a coin flip comes up heads, that is meaningless and cannot be tested, because you could just as easily have said there is a 50% chance of the coin coming up tails???

You can test “The coin will come up heads”. How do you test “50% odds, the coin will come up heads”? Note that this is different from “the coin will have come up heads roughly 50% of the time after N flips”.

Forget the coin flip, imagine you’re clueless about gravity and prone to saying “50% odds on the apple falling down” and its equivalent “50% odds on the apple not falling down”. Apple always falls down, but if we do this 100 times and you always randomly pick a position (because you don’t care), your expected accuracy is 50%*. When you say 50%, you effectively make no prediction either way.

*note that you’re not particularly likely to bet down vs up in a 50-50 or similarly balanced ratio, the ratios from 0-100 to 100-0 are each equally likely

“How do you test “50% odds, the coin will come up heads”? Note that this is different from “the coin will have come up heads roughly 50% of the time after N flips”.”

No, it’s the same.

Regarding the apples, you wouldn’t look at your overall “average” when you are making the same prediction many times. You would look at the frequency of correct “apple falls” predictions and “apple does not fall” predictions and it would be apparent that you were way off.

I agree when you have uncorrelated one-off 50% predictions, the actual results aggregated can’t tell you anything about the accuracy of your predictions.

No you’re not.

“50% chance of A” really means “if A happens, I will score this prediction as correct, and my chance of scoring this prediction correct is 50%”. “50% chance of ~A” means “if ~A happens, I will score this prediction as correct, and my chance of scoring this prediction correct is 50%”.

If you predict one event, this won’t matter. But if you are trying to predict multiple events, the two kinds of predictions combine differently and produce different distributions.

If you make a pair of predictions, “50% chance of A the first time and 50% chance of A the second time” is not synonymous with “50% chance of A the first time and 50% chance of ~A the second time”. If you got the sequence “A, ~A” you would say that the first pair of predictions was properly calibrated and the second one was not–the two pairs don’t mean the same thing, even though you substituted an “identical” prediction.

If a coin comes up heads 100% of the time (or any probability), but you randomly predict sides with 50% confidence, you’ll be right 50% of the time. That doesn’t say anything about your calibration or the tested events.

Yes, in that hypothetical. But is there a reason to believe that accurately models what is taking place here?

In that case your calibration is correct.

Agreed.

A 50% confidence is equivalent to saying you’d take either side of the prediction. Having a good sense of where that point is would be useful if you wanted to set up an over/under wager (in which you get a house cut, rather than participating in the betting yourself), among other scenarios.

Suppose you work as a meteorologist. In order to see if your work is reasonably accurate, you go back and see how your weather predictions turned out for the last year. You find that you predicted a 50% chance of rain on 100 days.

What you would want to find is that it rained about 50 of those days, and did NOT rain the other 50. You don’t ‘win’ by having more of those days with rain. That would make your predictions less accurate.

You’re doing things properly when half of your 50% guesses of rain are ‘wrong.’

If I randomly choose to predict “It will rain today” or “It will not rain today”, I will be correct approximately 50% of the time. That says nothing about my calibration or predictive skill.

Do most places have rain 180 days a year?

Doesn’t matter. For each individual day, you have a 50% chance of getting it right whether it’s raining or sunny. Sum over 365 days and your predictions will almost certainly look around 50% accurate, whether it rained 0, 365, or 180 days that year.

This only works since you’re aggregating individual predictions, though — “how many days is it going to rain this year?” is one prediction and not a binary one, and you need to evaluate its accuracy differently.

That’s very interesting. Thanks.

From this post in the Sequences:

and then goes on to explain how you can get more useful information by looking at more than calibration.

50% predictions are perfectly calibrated all the time every time when you include the fact that they directly imply a 50% prediction of the opposite outcome. Whatever happens, half are right and half are wrong. You don’t need to see the results to know this, so they’re not useful in assessing calibration. 50% prediction is a claim of absolute ignorance.

“50% prediction is a claim of absolute ignorance.”

Is a 50% prediction that a coin flip will be heads a claim of absolute ignorance?

A 50% prediction of X is a claim about scoring as welll as a claim about probability of scoring. A 50% prediction of X does not, then, imply a 50% prediction of ~X.

Sure it does. It says you’re calibrated enough (in this domain) to know that you don’t have any particular weather-related insight to make your predictions better than chance.

Thank you, this certainly introduces a boondoggle I hadn’t thought of.

It’s kind of fascinating to me how complicated statistics actually are, a lot of the time. My statistics I learned for a job in biology barely scratches the surface.

A big difference between the meteorological example (and also the coin, where the goodness of calibration tells us how well Scott can judge the coin’s bias) and what’s going on with Scott’s actual predictions (AFAIK) is that there is a systematic way of saying which prediction is which in the meteorological example. That is, while it’s arbitrary whether to say 50% rain or 50% no rain, once that decision has been made for the first prediction, then there is no more arbitrariness in the subsequent predictions. But Scott’s predictions are all unrelated, so this technique won’t work there.

Still, as Yosarian2 notes nearby, psychology matters. If Scott picks a consistent rule to phrase his 50% predictions (maybe always predicting the outcome which he would prefer, assuming that such a thing always exists), then the percentage of correct 50% predictions tells us something (perhaps about Scott’s level of optimism).

If the choice of how the prediction is phrased is random, isn’t the expected number of 50% predictions to be “correct” still 50%? It’s unlikely that someone who is well-calibrated will get 10 50% predictions correct in a row. The phrasing might introduce more random noise, but shouldn’t make the data useless.

edit for example:

suppose I make a series of 6 predictions for 6 different fair dice (d4, d6, d8, d10, d12, d20). How I phrase the prediction is determined randomly, and I think the dice are fair, so I might say “50% that the d4 will come up 1 or 2, 50% that the d6 will come up 4-6, 50% the d8 comes up 1-4” etc. In expectation, I get 50% of my predictions true, so I’m well-calibrated.

On the other hand, someone who thinks the dice are all biased towards low numbers might say there’s a 60% chance that each die gives a result in the bottom half of its range. This person will be right 50% of the time, and is thus overconfident.

They’re not harmful, just useless.

“If the choice of how the prediction is phrased is random, isn’t the expected number of 50% predictions to be “correct” still 50%?”

Yes.

“It’s unlikely that someone who is well-calibrated will get 10 50% predictions correct in a row.”

No. The expected value is 50%, but the chances of getting 50% exactly are the same as getting 100% (or 30%, or 0%): with randomised phrasing, the chance of getting

xof yournguesses correct is1/(n+1)for allx.Actually, you’re more likely to get 50% exactly than any other exact percentage, at least if there’s an even number overall so that 50% is even possible. For example, in the case of 2 predictions, you have a 25% chance of getting 0% correct, a 50% chance of getting 50% correct, and a 25% chance of getting 100% correct. In general, the probability of getting x of n guesses correct is C(n,x)/2^n.

You are obviously right, I am silly.

You could just as easily have picked the other side. But you couldn’t just as easily have predicted 10% or 90%–that would have been a different prediction, inconsistent with 50%.

If Scott makes ten 50% predictions and five of them turn out correct, that’s evidence that his calibration is pretty good. If either 1 or 9 turn out correct, that’s evidence that it isn’t.

Assume the predictions are of independent events. The test I suggest is to assume that all of Scott’s probabilities are correct and calculate how likely it is on that assumption that the actual results would be at least as far from his prediction as they were. The less likely that is the worse Scott is at calibrating his predictions.

Suppose, for simplicity, that his entire prediction was a list of ten independent events for each of which he claimed .5 probability. Seven of them turn out to be true. calculate the odds that ten coin flips will give you one, two, three, eight, nine or ten heads. That’s the probability that the outcome would be at least as far from his prediction as it was if his probabilities were correct.

The easy case is if all his predictions are false (or all true). That’s the odds of flipping a coin ten times and getting either ten heads or ten tails, so .5^9. It’s very unlikely, so strong evidence that the odds were not really .5 for each.

You would like to know the probability that the odds were all .5 conditional on the actual outcome, but the best you can do, just as with a conventional confidence measure, is the odds of the actual outcome (Scott doing at least as well as he did) conditional on the probabilities being all .5.

Sort of sorting out my own confusion more than making a claim:

So the way I keep thinking about it trying to sort out this comment chain, is that for any prediction Scott makes, the format he’s using, “P(X) = Y%”, is mathematically equivalent to if he were to say “P(X) = Y% && P(~X) = (100 – Y)%”. This is why his graph’s x-axis doesn’t need to go below .5.

In this sense, I think it makes sense to imagine looking at every prediction and its converse. This doesn’t seem like it should affect our results; being perfectly calibrated at 90% predictions means you’re also perfectly calibrated at 10% predictions, and vice versa, because all that matters is the phrasing (90% X, 10% ~X describe the same belief and pay out the same for the same outcome as bets)*. If we do this, then suddenly some of the confusion about 50% predictions goes away. Including all their inverses, also weighted at 50%, means that exactly half of our 50% “predictions” come true. No matter what the results are, 50% is “perfect” calibration, because it doesn’t claim anything. It’s not actually choosing a side, but it looks like it is, because it starts with the phrasing “I predict X with proability-“, but you’re not actually saying X is more likely to happen.

Another way I’m thinking about it is that 50% predictions are the 0 point for certainty. At first brush it might seem like saying something is 40% likely means you’re less certain, but in reality any deviation from 50% is a claim to predictive power, with 100% and 0% being perfect knowledge (which is impossible, hence their not being real probabilities). If Scott, instead of giving a 50% figure, had phrased them as “I don’t know whether X will happen.”, which is what he’s saying by saying 50%, he would achieve perfect calibration. I’m almost certain I remember reading about this exact concept in the Sequences somewhere but can’t find where it was.

Edit: Here it is. Relevant moment:

So maybe what I’m talking about is that by not looking at discrimination, the 50% predictions become meaningless, except in demonstrating Scott’s ignorance of a proposition, which we can obviously infer from his 50% prediction, without looking at the results.

*The isomorphism between Scott’s current format, and adding in each predictions converse, may not be as mathematically innocuous as I’m imagining, but it sure seems like all we’re doing is doubling our volume.

What does this really show? If I am throwing a weighted coin that always gives heads and you randomly oscillate between heads and tails predictions (because of your 50% certainty model), your correctness average will follow a binomial distribution.

Assuming you throw ten times, we have ~20% odds for four correct predictions, ~25% for five, ~20% for six. So if you get only one prediction correct (1%), we’ve either shown that you are unlucky, or that you aren’t picking your phrasing randomly and the way you choose which 50% side to take tends to anticorrelate with reality.

That doesn’t make them useless; if your 50% predictions are consistently right then it means you should have ranked them higher; if they’re consistently wrong then you should have ranked them lower.

Yes you could state them in the converse and if you are perfectly calibrated it shouldn’t matter, but the way that you state them matters psychology, and really the goal is to measure human systematic cognitive errors, so that matters a lot.

Hm, but how can your 50% predictions be “consistently right”? You’re actually not claiming that you think P or ~P is the correct prediction. “P(X) = .5” == “P(X) =.5 && P(~X) = .5”. Your 50% predictions being consistently right is also them being consistently wrong, isn’t it?

This makes me feel like I’m missing something. Does saying “X will happen: 50%” actually mean something that implies you’re “really” predicting X, rather than ~X? Because to me it seems like it is *actually saying* “X and ~X, each with P = .5”

Maybe the point of Scott’s exercise, in these cases, is to see if he has a tendency to “arbitrarily” choose the right or wrong prediction to write down in cases where he thinks he’s ignorant, even though technically speaking writing down X or ~X isn’t actually a prediction in favor of either one?

You are “right” if you get these 50/50 predictions correct only 50% of the time. This is an exercise in your ability to gauge the uncertainty in your own predictions.

If you predict with 50% certainty that Trump will continue to use Twitter you are not estimating your uncertainty very well.

The way I would put it is this:

If I was going to make a 50% prediction, I would try to always make it in the direction where IMHO “conventional wisdom” would say the odds of the event happening are less than 50%. Basically, put it in the direction where the prediction coming true would seem “surprising” to most people. (For example, I might say “there is a 50% chance that most types of cancer will be curable most of the time within the next 7 years” since IMHO that result would be more surprising to most people then failure would be.)

If I always did it in that direction, and 50% of my predictions came true, then that would mean I am well calibrated. If less than 50% come true, then it means that when I go against what I think is the “conventional wisdom” I am correct less often then I expect; if more than 50% come true then it means when I go against what I think is “conventional wisdom” I am correct more often then I expect.

You do have to be consistent though, and always make predictions going in the same direction, or else it can become meaningless.

As you say, this gives information as to how well calibrated you are in going against the conventional wisdom. Elsewhere around here, I suggested making the predictions in the direction that you would prefer come true, and then you learn how well calibrated your optimism is. This is all certainly useful, but I also think that it’s fundamentally different from how well calibrated your probabilities themselves are, which is what we’re talking about at the 70% level.

The way Scott does his predictions, you can’t mark them lower than 50%. If he wants to mark down a prediction of “10% chance of X happening”, he writes that as “90% chance of X not happening”. This suggests that he doesn’t exactly have a particularly consistent way of choosing whether to predict X or ~X at the 50% confidence level.

What kind of a cognitive error would it measure? It seems like the error would be something like “systematic bias in how you phrase predictions”, which would be pretty strange, and very different from the typical overconfidence/underconfidence errors.

To phrase the objection a bit differently:

As Scott is doing things, a prediction of 50% for A *is also* a prediction of 50% for not-A.

So, obviously, exactly half of anyone’s 50% predictions on binary questions come true.

Well, phrasing it like that makes it seem obviously untrue; or at least, not inherently true.

Reductio ad absurdum: suppose I am very good at making predictions in some particular field – say, 99% of my binary predictions come true. That doesn’t stop me from (incorrectly) believing that they are actually only 50% likely and presenting them as such. Scott’s analysis would correctly show that I was underconfident, wouldn’t it?

Also: if I were to say, “The Sun will explode tomorrow, 50%” that would certainly be overconfident; “The Sun will NOT explode tomorrow, 50%” would be underconfident; both statements are wrong, but they’re wrong in different ways, aren’t they?

Regarding your reductio:

If you actually believed that your predictions were 50% likely to be true, you’d be basically indifferent between phrasing them as “Prediction” and “Opposite of Prediction”, depending on how you happened to think of them. You’ll have a 99% success rate on the first kind and a 1% success rate on the second kind, which will average out to 50%.

Regarding overconfidence/underconfidence:

I don’t think you can really treat overconfidence as being the same as “predictions that have too high of a confidence percentage”, for exactly the reason that you’re illustrating. If you predict “80% chance that X will happen”, you’re also implicitly predicting “20% chance that X will not happen”. If X actually has a 70% chance of happening (leaving a 30% chance of X not happening), you are simultaneously both overconfident and underconfident.

I think it’s more useful to define overconfidence as something like “predictions that are too extreme”. That way, the 80% prediction and the implicit 20% prediction are both considered overconfident.

I have to admit that my initial feeling about your sun explosion example matches yours, but let me pose a question about a slightly different example: If I say “The sun will not explode tomorrow, 0.00001% confidence”, does that still strike you as underconfident? According to your definition, that would be ludicrously underconfident, but it definitely “feels” overconfident to me.

I disagree, but I must admit that I’m not entirely sure why, which makes my claim suspicious.

Perhaps when I say a 50% prediction what I am thinking of would be better described as a 50%+x prediction, where x is too small to meaningfully quantify but is still definitely positive? (Although I have a nagging feeling that I should really be talking about odds rather than probabilities, and that logarithms ought to come into it somewhere. Weird.)

As for overconfidence vs. underconfidence, consider that (for example) someone who routinely overestimates risks is not the same as someone who routinely underestimates risks, and it seems important to be able to distinguish the two cases. It seems that it ought to be possible to organize the mathematics so that this is possible without this apparent ambiguity.

I think there’s a clue in the fact that your version of the sun explosion example seems like a cheat: when you are making a prediction, it is always expected to be phrased so that the probability is 50% or more. Presumably there’s a reason for that expectation, and knowing what it was might help. 🙂

EDIT: no, that can’t be quite right. “The sun will explode tomorrow: 10%” seems perfectly OK (and neither underconfident nor overconfident) presumably because it is talking about a risk, rather than a prediction. Except a risk assessment is a sort of prediction. I’m confused.

Also: if I were to say, “The Sun will explode tomorrow, 50%” that would certainly be overconfident; “The Sun will NOT explode tomorrow, 50%” would be underconfident; both statements are wrong, but they’re wrong in different ways, aren’t they?

Since the statements are equivalent, they are definitely not wrong in different ways. Someone who said the first is exactly as confident as someone who said the second. What we have here is an issue in which “overconfidence” hasn’t been defined precisely. You can’t mix math with a poorly-defined English word and expect to remain free of paradoxes.

Anyway, saying you think a binary event happens (or doesn’t happen) with 50% probability is like saying you have no relevant information that would help you decide whether it will happen; it is as unconfident as it is possible to be. This is the uninformed prior.

If I were trying to define “confidence” properly I think that I’d claim that underconfidence consists of not updating enough away from the uninformed prior based on whatever information you have, and overconfidence means you’re over-updating. This would be a way that you could get to something resembling ShemTealeaf’s suggestion of “predictions that are too extreme.”

I’m not sure that follows. By way of dubious analogy, two different arguments can result in the same (incorrect) conclusion, but still be wrong in different ways.

The idea of defining overconfidence vs underconfidence in terms of over-updating vs. under-updating sounds reasonable, but I don’t think 50% is usually going to be the appropriate choice of prior. To go back to the weather analogy, if you know that it rains 10% of the time on average, but are trying to predict whether or not it will rain on any particular day, it is 10% – not 50% – that is a “non-prediction”; so to speak.

As a more extreme example, if I were to predict (with 10% confidence) that the next set of Lotto numbers will be 15, 20, 32, 41, -5 and Pi, I don’t see any reasonable way not to consider that to be overconfident. Related to “privileging the hypothesis” perhaps?

But the dubious analogy doesn’t work – the two statements really are equivalent. P(A) = 0.5 iff P(~A) = 0.5.

if you know that it rains 10% of the time on average, but are trying to predict whether or not it will rain on any particular day, it is 10% – not 50% – that is a “non-prediction”… if I were to predict (with 10% confidence) that the next set of Lotto numbers will be 15, 20, 32, 41, -5 and Pi, I don’t see any reasonable way not to consider that to be overconfident.

The fact that it rains 10% of the time on average is precisely the information that you are using to update away from the uninformed 50% prior.

And similarly your lottery example is overconfident because you are calling on your knowledge of lotteries, numbers, and sequences.

Hmmm. You’re considering the claim and the stated confidence level together as a single composite statement about the relevant probability with no further meaning; I seem to want to consider the meaning of statements independently as well, e.g., see Yosarian2’s comments about whether the claim is surprising or not.

… it’s like saying “it’s not-not weird” (example) which considered as a logical unit may be equivalent to “it’s weird” BUT …

… uh, anyway, your interpretation seems far more logically sound on the face of it, but where I get stuck is that if making ten correct claims and assigning them 50% confidence isn’t underconfidence, how else can we describe it? And if making ten correct claims and assigning them 70% confidence IS underconfidence, where exactly does the boundary sit between those two scenarios and why?

As I said in a different post, in order for 50% predictions to be meaningful, you should always state them in the same “direction”; I suggested that you always do them in the direction where conventional wisdom would suggest that the odds of the event happening are less than 50%. That is, always word the prediction in the direction where you being correct would be more surprising to people than if you were wrong.

For example, if I think that football team X is much more likely to do well then conventional wisdom would predict, I might say “There is a 50% chance that football team X will win the Superbowl next year”. Most people would put the odds of that happening at much less than 50%.

So if you consistently can take things that most people would consider unlikely, rank them at 50% likely to happen, and then you are correct 50% of the time, then that would imply you are very well calibrated. If you are correct less than 50% of the time, it means you overestimate your ability to go against conventional wisdom; if you are correct more than 50% of the time, it means you actually underestimate your ability to go against conventional wisdom.

But you always do have to state the prediction in the same “direction” (in this case, the direction of “the prediction coming true would be a more surprising result to most people then the prediction not coming true”) in order to measure your calibration. That is not an issue for 75% or 90% predictions, which makes 50% predictions a little more tricky to work with, but I think it’s doable.

(There’s also the complicating factor that you often won’t really know what conventional wisdom is, so in a sense what you’re measuring is how often you’re right when you’re going against what *you think* conventional wisdom is. I think that’s still a valuable thing to know though.)

So in your example, someone might say “there is a 50% chance that the sun explodes tomorrow”; what they are saying is “I think the odds that the sun will explode tomorrow are much higher than conventional wisdom would expect, and I so am going to make a prediction in that direction, and I expect about half of my predictions in that direction to be correct; if half of them are then that would be much higher then conventional wisdom would predict”. I mean, if someone said “There is a 50% chance that the Sun explodes tomorrow, and there is a 50% chance that Alpha Centauri explodes tomorrow”, and tomorrow Alpha Centauri explodes (which I guess we wouldn’t find out about for about 4 years but you get the idea), then after that I would put a hell of a lot of credibility into any predictions that person makes about similar topics in the future.

I would be indifferent between phrasing *one* prediction in that manner or not, but if I had multiple predictions I would not be indifferent between phrasing one of the multiple predictions in that manner or not. a “50% chance of X” prediction is not the same as a “50% chance of ~X” prediction because they combine differently in groups.

Consider making a pair of two 50% chance of X predictions, and consider making a pair of predictions, where one is 50% chance of X and one is 50% chance of ~X. These do not say the same thing; they make identical statements about probability, but different statements about calibration. If the result was X both times, the first pair would be poorly calibrated and the second pair would be well calibrated.

I know there’s a lot of talk already about this, but there’s a big difference between

and

Since Scott’s making predictions over multiple events, the 50% predictions are a way to calibrate whether he’s accurate in predicting which events are 50% likely — not whether he can guess correctly on 50%-likely events.

Sure, he could word them the opposite way, but they’d still be useful for calibration.

E.g., if he predicted 100 coin flips as “heads: 50%” (or equivalently “tails: 50%”), then he’s well calibrated. If he predicted 100 d4 rolls as “lands on one: 50%”, then he’s not well calibrated.

Similarly, for the d4 he could say either “lands on one: 25%” or “doesn’t land on one: 75%”. The wording isn’t significant; the percent correct vs. which items he predicted at that percentage is what matters for calibration.

Could you try and wrap it up into a single function that measures some amount of surprise and then be able get a global value for calibration? Probably, but that doesn’t mean what he’s doing is wrong or that there’s a bias towards which way it’s worded. Also, notice that he only makes predictions in [50,100). So I’ll bet he’s aware that P: 80% is equivalent to ~P: 20%, and is intentionally making all his predictions in the [50,100) range to avoid the confusion of equivalent statements.

If he predicts “lands on one: 50%”, then to him there’s no reason to prefer it to “doesn’t land on one: 50%”. So if he makes 100 predictions about things that are like d4 rolls, roughly half of them will probably take the latter form. This will give him roughly 50% accuracy and make his calibration look really good. This is why you have to discard 50% predictions when measuring calibration.

Really it’s not just that you need to discard 50% predictions. You can’t just see that 50% predictions are bad and decide to ignore them and pretend that everything else is fine. An issue like this points to a deeper issue with the whole methodology. I don’t know offhand how to resolve it and I don’t have the time to figure it out.

I expect that the value of calibration needs to be weighted by the amount of divergence of the prediction from 50%.

This is unsatisfying, because intuitively we would like to be able to say that someone who can assign correct probabilities to events is well-calibrated, regardless of the probability of the event. But I think that’s not actually true, unless there’s a fixed basket of events.

That still seems like an unjustified conclusion. You may insist that his predictions “ought” to be in either form at random, but you can’t actually force him to do so.

Also consider: if someone was actually predicting d4 rolls, it would be obvious if they were cheating in this way, because you can easily distinguish the predictions that look like “I’ll get a 1” or “I’ll get a 2” from those that look like “I won’t get a 1” or “I won’t get a 2” and as soon as you analyze each set separately the calibration rating plummets.

You can only do this singling out of “I’ll get a 1” as different from “I’ll get a not 1” because you know that the probability for them is not 50% (one is overconfident, another is underconfident). Scott sees them as 50%, and thus can’t tell the difference between them.

To put you in Scott’s position: I have here a weighed coin. One of the faces is three times as likely as the other, but you do not know which. I will present you 100 such coins, not necessarily weighed in the same way. For each, I want you to bet on whichever face is like betting on the one in a d4. If you oscillate your predictions, you are cheating*.

*Note that I’m not forcing you to oscillate like I forced Scott above. In fact, I am forcing you to not oscillate, because cheaters get shot. I think you will still oscillate, because honest 50% predictors don’t know better.

Ah, I misunderstood what you meant by “things that are like d4 rolls”.

I was thinking more along the lines of “you know it rains about 10% of the time, but are trying to predict which particular days”. Note that a 50% success rate in this scenario means you are already doing significantly better than chance as far as making predictions goes.

In this scenario, I don’t think there’s any problem in measuring the calibration of 50% predictions. It’s 10% predictions that become a problem.

No, this is specific to 50% predictions.

If you think 10% rain is likely, you will not see 10% not-rain as an equivalent prediction. You will prefer to say “rain, 10% odds”, and you will not oscillate between “rain, 10% odds” and “no rain, 10% odds”. Additionally, if you do oscillate because you’re trying to game the system or something, you will come off as poorly calibrated.

player:1010101010

game: 1000000000

60% correct when giving 10% odds, that’s terrible.