I.

I always wanted to meditate more, but never really got around to it. And (I thought) I had an unimpeachable excuse. The demands of a medical career are incompatible with such a time-consuming practice.

Enter Daniel Ingram MD, an emergency physician who claims to have achieved enlightenment just after graduating medical school. His book is called Mastering The Core Teachings Of The Buddha, but he could also have called it Buddhism For ER Docs. ER docs are famous for being practical, working fast, and thinking everyone else is an idiot. MCTB delivers on all three counts. And if you’ve ever had an attending quiz you on the difference between type 1 and type 2 second-degree heart block, you’ll love Ingram’s taxonomy of the stages of enlightenment.

The result is a sort of perfect antidote to the vague hippie-ism you get from a lot of spirituality. For example, from page 324:

I feel the need to address, which is to say shoot down with every bit of rhetorical force I have, the notion promoted by some teachers and even traditions that there is nothing to do, nothing to accomplish, no goal to obtain, no enlightenment other than the ordinary state of being…which, if it were true, would have been very nice of them, except that it is complete bullshit. The Nothing To Do School and the You Are Already There School are both basically vile extremes on the same basic notion that all effort to attain to mastery is already missing the point, an error of craving and grasping. They both contradict the fundamental premise of this book, namely that there is something amazing to attain and understand and that there are specific, reproducible methods that can help you do that. Here is a detailed analysis of what is wrong with these and related perspectives…

…followed by a detailed analysis of what’s wrong with this position, which he compared to “let[ting] a blind and partially paralyzed untrained stroke victim perform open-heart surgery on your child based on the notion that they are already an accomplished surgeon but just have to realize it”.

This isn’t to say that MCTB isn’t a spiritual book, or that it shies away from mysticism or the transcendent. MCTB is very happy to discuss mysticism and the transcendent. It just quarantines the mystery within a carefully explained structure of rationally-arranged progress, so that it looks something like “and at square 41B in our perfectly rectangular grid you’ll encounter a mind-state which is impossible to explain even in principle, here are a few woefully inadequate metaphors for this mind-state so you’ll know when you’ve found it and should move on to square 41C.”

This is a little jarring. But – Ingram argues – it’s also very Buddhist. If you read the sutras with an open mind, the Buddha sounds a lot more like an ER doctor than a hippie. MCTB has a very Protestant fundamentalist feeling of digging through the exterior trappings of a religion to try to return to the purity of its origins. As far as I can tell, it succeeds – and in succeeding helped me understand Buddhism a whole lot better than anything else I’ve read.

II.

Ingram follows the Buddha in dividing the essence of Buddhism into three teachings: morality, concentration, and wisdom.

Morality seems like the odd one out here. Some Buddhists like to insist that Buddhism isn’t really a “religion”. It’s less like Christianity or Islam than it is like (for example) high intensity training at the gym – a highly regimented form of practice that improves certain faculties if pursued correctly. Talking about “morality” makes this sound kind of hollow; nobody says you have to be a good person to get bigger muscles from lifting weights.

MCTB gives the traditional answer: you should be moral because it’s the right thing to do, but also because it helps meditation. The same things that make you able to sleep at night with a clear mind make you able to meditate with a clear mind:

One more great thing about the first training [morality] is that it really helps with the next training: concentration. So here’s a tip: if you are finding it hard to concentrate because your mind is filled with guilt, judgment, envy or some other hard and difficult thought pattern, also work on the first training, kindness. It will be time well spent.

That leaves concentration (samatha) and wisdom (vipassana). You do samatha to get a powerful mind; you get a powerful mind in order do to vipassana.

Samatha meditation is the “mindfulness” stuff you’re always hearing about: concentrate on the breath, don’t let yourself get distracted, see if you can just attend to the breath and nothing else for minutes or hours. I read whole books about this before without understanding why it was supposed to be good, aside from vague things like “makes you feel more serene”. MCTB gives two reasons: first, it gets you into jhanas. Second, it prepares you for vipassana.

Jhanas are unusual mental states you can get into with enough concentration. Some of them are super blissful. Others are super tranquil. They’re not particularly meaningful in and of themselves, but they can give you heroin-level euphoria without having to worry about sticking needles in your veins. MCTB says, understatedly, that they can be a good encouragement to continue your meditation practice. It gives a taxonomy of eight jhanas, and suggests that a few months of training in samatha meditation can get you to the point where you can reach at least the first.

But the main point of samatha meditation is to improve your concentration ability so you can direct it to ordinary experience. Become so good at concentrating that you can attain various jhanas – but then, instead of focusing on infinite bliss or whatever other cool things you can do with your new talent, look at a wall or listen to the breeze or just try to understand the experience of existing in time.

This is vipassana (“insight”, “wisdom”) meditation. It’s a deep focus on the tiniest details of your mental experience, details so fleeting and subtle that without a samatha-trained mind you’ll miss them entirely. One such detail is the infamous “vibrations”, so beloved of hippies. Ingram notes that every sensation vibrates in and out of consciousness at a rate of between five and forty vibrations per second, sometimes speeding up or slowing down depending on your mental state. I’m a pathetic meditator and about as far from enlightenment as anybody in this world, but with enough focus even I have been able to confirm this to be true. And this is pretty close to the frequency of brain waves, which seems like a pretty interesting coincidence.

But this is just an example. The point is that if you really, really examine your phenomenological experience, you realize all sorts of surprising things. Ingram says that one early insight is a perception of your mental awareness of a phenomenon as separate from your perception of that phenomenon:

This mental impression of a previous sensation is like an echo, a resonance. The mind takes a crude impression of the object, and that is what we can think about, remember, and process. Then there may be a thought or an image that arises and passes, and then, if the mind is stable, another physical pulse. Each one of these arises and vanishes completely before the other begins, so it is extremely possible to sort out which is which with a stable mind dedicated to consistent precision and not being lost in stories. This means the instant you have experienced something, you know that it isn’t there any more, and whatever is there is a new sensation that will be gone in an instant. There are typically many other impermanent sensations and impressions interspersed with these, but, for the sake of practice, this is close enough to what is happening to be a good working model.

Engage with the preceding paragraphs. They are the stuff upon which great insight practice is based. Given that you know sensations are vibrating, pulsing in and out of reality, and that, for the sake of practice, every sensation is followed directly by a mental impression, you now know exactly what you are looking for. You have a clear standard. If you are not experiencing it, then stabilize the mind further, and be clearer about exactly when and where there are physical sensations.

With enough of this work, you gain direct insight into what Buddhists call “the three characteristics”. The first is impermanence, and is related to all the stuff above about how sensations flicker and disappear. The second is called “unsatisfactoriness”, and involves the inability of any sensation to be fulfilling in some fundamental way. And the last is “no-self”, an awareness that these sensations don’t really cohere into the classic image of a single unified person thinking and perceiving them.

The Buddha famously said that “life is suffering”, and placed the idea of suffering – dukkha – as the center of his system. This dukkha is the same as the “unsatisfactoriness” above.

I always figured the Buddha was talking about life being suffering in the sense that sometimes you’re poor, or you’re sick, or you have a bad day. And I always figured that making money or exercising or working to make your day better sounded like a more promising route to dealing with this kind of suffering than any kind of meditative practice. Ingram doesn’t disagree that things like bad days are examples of dukkha. But he explains that this is something way more fundamental. Even if you were having the best day of your life and everything was going perfectly, if you slowed your mind down and concentrated perfectly on any specific atomic sensation, that sensation would include dukkha. Dukkha is part of the mental machinery.

MCTB acknowledges that all of this sounds really weird. And there are more depths of insight meditation, all sorts of weird things you notice when you look deep enough, that are even weirder. It tries to be very clear that nothing it’s writing about is going to make much sense in words, and that reading the words doesn’t really tell you very much. The only way to really make sense of it is to practice meditation.

When you understand all of this on a really fundamental level – when you’re able to tease apart every sensation and subsensation and subsubsensation and see its individual components laid out before you – then at some point your normal model of the world starts running into contradictions and losing its explanatory power. This is very unpleasant, and eventually your mind does some sort of awkward Moebius twist on itself, adopts a better model of the world, and becomes enlightened.

III.

The rest of the book is dedicated to laying out, in detail, all the steps that you have to go through before this happens. In Ingram’s model – based on but not identical to the various models in various Buddhist traditions – there are fifteen steps you have to go through before “stream entry” – the first level of enlightenment. You start off at the first step, after meditating some number of weeks or months or years you pass to the second step, and so on.

A lot of these are pretty boring, but Ingram focuses on the fourth step, Arising And Passing Away. Meditators in this step enter what sounds like a hypomanic episode:

In the early part of this stage, the meditator’s mind speeds up more and more quickly, and reality begins to be perceived as particles or fine vibrations of mind and matter, each arising and vanishing utterly at tremendous speed…As this stage deepens and matures, meditators let go of even the high levels of clarity and the other strong factors of meditation, perceive even these to arise and pass as just vibrations, not satisfy, and not be self. They may plunge down into the very depths of the mind as though plunging deep underwater to where they can perceive individual frames of reality arise and pass with breathtaking clarity as though in slow motion […]

Strong sensual or sexual feelings and dreams are common at this stage, and these may have a non-discriminating quality that those attached to their notion of themselves as being something other than partially bisexual may find disturbing. Further, if you have unresolved issues around sexuality, which we basically all have, you may encounter aspects of them during this stage. This stage, its afterglow, and the almost withdrawal-like crash that can follow seem to increase the temptation to indulge in all manner of hedonistic delights, particularly substances and sex. As the bliss wears off, we may find ourselves feeling very hungry or lustful, craving chocolate, wanting to go out and party, or something like that. If we have addictions that we have been fighting, some extra vigilance near the end of this stage might be helpful.

This stage also tends to give people more of an extroverted, zealous or visionary quality, and they may have all sorts of energy to pour into somewhat idealistic or grand projects and schemes. At the far extreme of what can happen, this stage can imbue one with the powerful charisma of the radical religious leader.

Finally, at nearly the peak of the possible resolution of the mind, they cross something called “The Arising and Passing Event” (A&P Event) or “Deep Insight into the Arising and Passing Away”…Those who have crossed the A&P Event have stood on the ragged edge of reality and the mind for just an instant, and they know that awakening is possible. They will have great faith, may want to tell everyone to practice, and are generally evangelical for a while. They will have an increased ability to understand the teachings due to their direct and non-conceptual experience of the Three Characteristics. Philosophy that deals with the fundamental paradoxes of duality will be less problematic for them in some way, and they may find this fascinating for a time. Those with a strong philosophical bent will find that they can now philosophize rings around those who have not attained to this stage of insight. They may also incorrectly think that they are enlightened, as what they have seen was completely spectacular and profound. In fact, this is strangely common for some period of time, and thus may stop practicing when they have actually only really begun.

This is a common time for people to write inspired dharma books, poetry, spiritual songs, and that sort of thing. This is also the stage when people are more likely to join monasteries or go on great spiritual quests. It is also worth noting that this stage can look an awful lot like a manic episode as defined in the DSM-IV (the current diagnostic manual of psychiatry). The rapture and intensity of this stage can be basically off the scale, the absolute peak on the path of insight, but it doesn’t last. Soon the meditator will learn what is meant by the phrase, “Better not to begin. Once begun, better to finish!”

If this last part sounds ominous, it probably should. If the fourth stage looks like a manic episode, the next five or six stages all look like some flavor of deep clinical depression. Ingram discusses several spiritual traditions and finds that they all warn of an uncanny valley halfway along the spiritual path; he himself adopts St. John’s phrase “Dark Night Of The Soul”. Once you have meditated enough to reach the A&P Event, you’re stuck in the (very unpleasant) Dark Night Of The Soul until you can meditate your way out of it, which could take months or years.

Ingram’s theory is that many people have had spiritual experiences without deliberately pursuing a spiritual practice – whether this be from everyday life, or prayer, or drugs, or even things you do in dreams. Some of these people accidentally cross the A&P Event, reach the Dark Night Of The Soul, and – not even knowing that the way out is through meditation – get stuck there for years, having nothing but a vague spiritual yearning and sense that something’s not right. He says that this is his own origin story – he got stuck in the Dark Night after having an A&P Event in a dream at age 15, was low-grade depressed for most of his life, and only recovered once he studied enough Buddhism to realize what had happened to him and how he could meditate his way out:

When I was about 15 years old I accidentally ran into some of the classic early meditation experiences described in the ancient texts and my reluctant spiritual quest began. I did not realize what had happened, nor did I realize that I had crossed something like a point of no return, something I would later call the Arising and Passing Away. I knew that I had had a very strange dream with bright lights, that my entire body and world had seemed to explode like fireworks, and that afterwards I somehow had to find something, but I had no idea what that was. I philosophized frantically for years until I finally began to realize that no amount of thinking was going to solve my deeper spiritual issues and complete the cycle of practice that had already started.

I had a very good friend that was in the band that employed me as a sound tech and roadie. He was in a similar place, caught like me in something we would later call the Dark Night and other names. He also realized that logic and cognitive restructuring were not going to help us in the end. We looked carefully at what other philosophers had done when they came to the same point, and noted that some of our favorites had turned to mystical practices. We reasoned that some sort of nondual wisdom that came from direct experience was the only way to go, but acquiring that sort of wisdom seemed a daunting task if not impossible […]

I [finally] came to the profound realization that they have actually worked all of this stuff out. Those darn Buddhists have come up with very simple techniques that lead directly to remarkable results if you follow instructions and get the dose high enough. While some people don’t like this sort of cookbook approach to meditation, I am so grateful for their recipes that words fail to express my profound gratitude for the successes they have afforded me. Their simple and ancient practices revealed more and more of what I sought. I found my experiences filling in the gaps in the texts and teachings, debunking the myths that pervade the standard Buddhist dogma and revealing the secrets meditation teachers routinely keep to themselves. Finally, I came to a place where I felt comfortable writing the book that I had been looking for, the book you now hold in your hands.

Once you meditate your way out of the Dark Night, you go through some more harrowing experiences, until you finally reach the fifteenth stage, Fruition, and achieve “stream entry” – the first level of enlightenment. Then you do it all again on a higher level, kind of like those video games where when you beat the game you get access to New Game+ . Traditionally it takes four repetitions of the spiritual path before you attain complete perfect enlightenment, but Ingram suggests this is metaphorical and says it took him approximately twenty-seven repetitions over seven years.

He also says – and here his usual lucidity deserted him and I ended up kind of confused – that once you’ve achieved stream entry, you’re going to be going down paths whether you like it or not – the “stream” metaphor is apt insofar as it suggests being borne along by a current. The rest of your life – even after you achieve complete perfect enlightenment – will be spent cycling through the fifteen stages, with each stage lasting a few days to months.

This seems pretty bad, since the stages look a lot like depression, mania, and other more arcane psychiatric and psychological problems. Even if you don’t mind the emotional roller coaster, a lot of them sound just plain exhausting, with your modes of cognition and perception shifting and coming into question at various points. MCTB offers some tips for dealing with this – you can always slow your progress down the path by gorging on food, refusing to meditate, and doing various other unspiritual things, but the whole thing lampshades a question that MCTB profoundly fails at giving anything remotely like an answer to:

IV.

Why would you want to do any of this?

The Buddha is supposed to have said: “I gained nothing whatsoever from Supreme Enlightenment, and for that reason it is called Supreme Enlightenment”. And sure, that’s the enigmatic Zen-sounding sort of statement we expect from our spiritual leaders. But if Buddhist practice is really difficult, and makes you perceive every single sensation as profoundly unsatisfactory in some hard-to-define way, and can plunge you into a neverending depression which you might get out of if you meditate hard enough, and then gives you a sort of permanent annoying low-grade bipolar disorder even if you succeed, then we’re going to need something better than pithy quotes.

Ingram dedicates himself hard to debunking a lot of the things people would use to fill the gap. Pages 261-328 discuss the various claims Buddhist schools have made about enlightenment, mostly to deny them all. He has nothing but contempt for the obviously silly ones, like how enlightened people can fly around and zap you with their third eyes. But he’s equally dismissive of things that sort of seem like the basics. He denies claims about how enlightened people can’t get angry, or effortlessly resist temptation, or feel universal unconditional love, or things like that. Some of this he supports with stories of enlightened leaders behaving badly; other times he cites himself as an enlightened person who frequently experiences anger, pain, and the like. Once he’s stripped everything else away, he says the only thing one can say about enlightenment is that it grants a powerful true experience of the non-dual nature of the world.

But still, why would we want to get that? I am super in favor of knowledge-for-knowledge’s-sake, but I’ve also read enough Lovecraft to have strong opinions about poking around Ultimate Reality in ways that tend to destroy your mental health.

The best Ingram can do is this:

I realize that I am not doing a good job of advertising enlightenment here, particularly following my descriptions of the Dark Night. Good point. My thesis is that those who must find it will, regardless of how it is advertised. As to the rest, well, what can be said? Am I doing a disservice by not selling it like nearly everyone else does? I don’t think so. If you want grand advertisements for enlightenment, there is a great stinking mountain of it there for you partake of, so I hardly think that my bringing it down to earth is going to cause some harmful deficiency of glitz in the great spiritual marketplace.

[Meditation teacher] Bill Hamilton had a lot of great one-liners, but my favorite concerned insight practices and their fruits, of which he said, “Highly recommended, can’t tell you why.” That is probably the safest and most accurate advertisement for enlightenment that I have ever heard.

V.

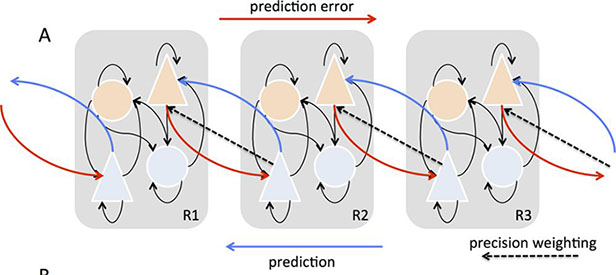

I was reading MCTB at the same time I read Surfing Uncertainty, and it was hard not to compare them. Both claim to be guides to the mysteries of the mind – one from an external scientific perspective, the other from an internal phenomenological perspective. Is there any way to link them up?

Remember this quote from Surfing Uncertainty?:

Plausibly, it is only because the world we encounter must be parsed for action and intervention that we encounter, in experience, a relatively unambiguous determinate world at all. Subtract the need for action and the broadly Bayesian framework can seem quite at odds with the phenomenal facts about conscious perceptual experience: our world, it might be said, does not look as if it is encoded in an intertwined set of probability density distributions. Instead, it looks unitary and, on a clear day, unambiguous…biological systems, as mentioned earlier, may be informed by a variety of learned or innate “hyperpriors” concerning the general nature of the world. One such hyperprior might be that the world is usually in one determinate state or another.

Taken seriously, it suggests that some of the most fundamental factors of our experience are not real features of the sensory world, but very strong assumptions to which we fit sense-data in order to make sense of them. And Ingram’s theory of vipassana meditation looks a lot like concentrating really hard on our actual sense-data to try to disentangle them from the assumptions that make them cohere.

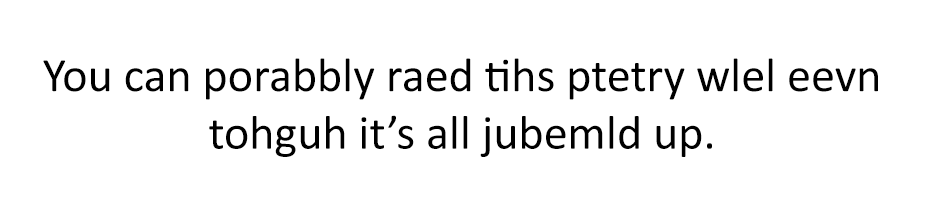

In the same way that our priors “snap” phrases like “PARIS IN THE THE SPRINGTIME” to a more coherent picture with only one “the”, or “snap” our saccade-jolted and blind-spot-filled visual world into a reasonable image, maybe they snap all of this vibrating and arising and passing away into something that looks like a permanent stable image of the world.

And in the same way that concentrating on “PARIS IN THE THE SPRINGTIME” really hard without any preconceptions lets you sniff out the extra “the”, so maybe enough samatha meditation lets you concentrate on the permanent stable image of the world until it dissolves into whatever the brain is actually doing. Maybe with enough dedication to observing reality as it really is rather than as you predict it to be, you can expose even the subjective experience of an observer as just a really strong hyperprior on all of the thought-and-emotion-related sense-data you’re getting.

That leaves dukkha, this weird unsatisfactoriness that supposedly inheres in every sensation individually as well as life in general. If the goal of the brain is minimizing prediction error, if all of our normal forms of suffering like hunger and thirst and pain are just special cases of predictive error in certain inherent drives, then – well, this is a very fundamental form of badness which is inherent in all sensation and perception, and which a sufficiently-concentrated phenomenologist might be able to notice directly. Relevant? I’m not sure.

Mastering The Core Teachings Of The Buddha is a lucid guide to issues surrounding meditation practice and a good rational introduction to the Buddhist system. Parts of it are ultimately unsatisfactory, but apparently this is true of everything, so whatever.

Also available for free download here

Highlights From The Comments On My IRB Nightmare

Many people took My IRB Nightmare as an opportunity to share their own IRB stories. From an emergency medicine doctor, via my inbox:

From baj2235 on the subreddit:

From Garrett in the comments:

From Katie on Facebook:

From Hirsin on Hacker News:

What is our country coming to when you can’t even attach lasers to babies anymore?

Some of the other stories were kind of cute. Dahud in the comments:

And of course James Miller is still James Miller:

Along with these, a lot of other people were broadly sympathetic but thought that if I knew how to play the system a little better, or was somewhere a little more research-focused, things might have gone better for me. Virgil in the comments:

From Eternaltraveler in the comments:

And from PM_ME_YOUR_FRAME on the subreddit (who I might hunt down and beg to be my research advisor if I ever do anything like this again):

And this really thorough comment from friendlygrantadmit:

Some people thought I was being too flippant, or leaving out parts of the story. Many of them mentioned that the focus on Nazis overshadowed some genuinely horrific all-American research misconduct like the Tuskegee Syphilis Experiment. They emphasized that my personal experience doesn’t overrule all of the really important reasons IRBs exist. For example, tedwick from the subreddit:

And kyleboddy from the comments:

A lot of these are good points. And some of what I wrote was definitely unfair snark – I understand they’ve got to ask you whether you plan on removing anyone’s organs; if they don’t ask, how will they know? And maybe linking to Schneider’s book about eliminating the IRB system was a mistake – I just meant to show there was an existing conversation about this. I definitely didn’t mean to trivialize Tuskegee, to say that I am a radical Scheiderian, to act like my single experience damns all IRBs forever, or to claim that IRBs can’t possibly have a useful role to play. I haven’t even begun to wade into the debate between the critics and proponents of the system. The point I wanted to make was that whether or not IRBs are useful for high-risk studies, they’ve crept annoyingly far into low-risk studies – to the detriment of everyone.

Nobody expects any harm from asking your co-worker “How are you this morning?” in conversation. But if I were to turn this into a study – “Diurnal Variability In Well-Being Among Office Workers” – I would need to hire a whole team of managers just to get through the risk paperwork and the consent paperwork and the weekly reports and the team meetings. I can give a patient twice the standard dose of a dangerous medication without justifying myself to anyone. I can confine a patient involuntarily for weeks and face only the most perfunctory legal oversight. But if I want to ask them “How are you this morning?” and make a study out of it, I need to block off my calendar for the next ten years to do the relevant paperwork.

I feel like I’m protesting a police state, and people are responding “Well, you don’t want total anarchy with murder being legal, do you?” No, I don’t. I think there’s a wide range of possibilities between “police state” and “anarchy”. In the same way, I think there’s a wide range of possibilities between “science is totally unregulated” and “scientists have to complete a mountain of paperwork before they can ask someone how their day is going”.

I dare you to tell me we’re at a happy medium right now. Go on, I dare you.

I regret to say this is only getting worse. New NIH policies are increasingly trying to reclassify basic science as “clinical trials”, requiring more paperwork and oversight. For example, under the new regulations, brain scan research – the type where they ask you to think about something while you’re in an fMRI to see which parts of your brain light up – would be a “clinical trial” since it measures “a health-related biomedical or behavioral outcome”. This could require these studies to meet the same high standards as studies giving experimental drugs or new gene therapies. The Science Magazine article quotes a cognitive neuroscientist:

A bunch of researchers from top universities have written a petition trying to delay the changes (if you’ve got an academic affiliation, you might want to check and consider signing yourself). But it’s anyone’s guess whether they’ll succeed. If not, good luck to any brain researcher who doesn’t want to go through everything I did. They’ll need it.