[This post is having major technical issues. Some comments may not be appearing. If you can’t comment, please say so on the subreddit.]

I. I Come To Praise Caesar, Not To Bury Him

Several years ago, an SSC reader made an r/slatestarcodex subreddit for discussion of blog posts here and related topics. As per the usual process, the topics that generated the strongest emotions – Trump, gender, race, the communist menace, the fascist menace, etc – started taking over. The moderators (and I had been added as an honorary mod at the time) decreed that all discussion of these topics should be corralled into one thread so that nobody had to read them unless they really wanted to. This achieved its desired goal: most of the subreddit went back to being about cognitive science and medicine and other less-polarizing stuff.

Unexpectedly, the restriction to one thread kick-started the culture war discussions rather than toning them down. The thread started getting thousands of comments per week, some from people who had never even heard of this blog and had just wandered in from elsewhere on Reddit. It became its own community, with different norms and different members from the rest of the board.

I expected this to go badly. It kind of did; no politics discussion area ever goes really well. There were some of the usual flame wars, point-scoring, and fanatics. I will be honest and admit I rarely read the thread myself.

But in between all of that, there was some really impressive analysis, some good discussion, and even a few changed minds. Some testimonials from participants:

For all its awfulness there really is something special about the CW thread. There are conversations that have happened there that cannot be replicated elsewhere. Someone mentioned its accidental brilliance and I think that’s right—it catches a wonderful conversational quality I’ve never seen on the Internet, and I’ve been on the Internet since the 90s – werttrew

I feel that, while practically ever criticism of the CW thread I have ever read is true, it is still the best and most civil culture war-related forum for conversation I have seen. And I find the best-of roundup an absolute must-read every week – yrrosimyarin

The Culture War Roundup threads were blessedly neutral ground for people to test their premises and moral intuitions against a gauntlet of (sometimes-forced!) kindness and charity. There was no guarantee that your opinion would carry the day, but if you put in the effort, you could be assured a fair reading and cracking debate. Very little was solved, but I’m not sure that was really the point. The CWRs were a place to broaden your understanding of a given topic by an iterative process of “Yes, but…” and for a place that boasted more than 15,000 participants, shockingly little drama ensued. That was the /r/slatestarcodex CWRs at their best, and that’s the way we hope they will be remembered by the majority of people who participated in them. – rwkasten

We really need to turn these QCs into a book or wiki or library of some kind. So much good thought, observation, introspection, etc. exists in just this one thread alone–to say nothing of the other QC posts in past CW threads. It would be nice to have a separate place, organized by subject matter, to just read these insightful posts – TheEgosLastStand

I think the CW thread is obviously a huge lump of positive utility for a large number of people, because otherwise they wouldn’t spend so much time on it. I’ve learned a lot in the thread, both about the ideas and beliefs of my outgroups, and by better honing my own beliefs and ideas in a high-pressure selective environment. I’ve shared out the results of what I’ve learned to all of my ingroup across Facebook and Twitter and in person, and I honestly think it’s helped foster better and more sophisticated thought about the culture war in a clique of several dozen SJ-aligned young people in the OC area, just from my tangential involvement as a vector – darwin2500

On one hand, as other commenters in this thread have said, I recognize it does have a lot of full-time opinionated idiots squabbling, and is inarguably filled with irrationality, bad takes, contrarianism, and Boo Outgroup posturing. I agree with many of [the criticisms] of overtly racist and stupid posts in there. Yet it also has a special, weird, fascinating quality which has led to some very insightful discussions which I have not encountered anywhere else on the Internet (and I have used the Internet 8+ hours a day almost my whole life). – c_o_r_b_a

There is no place on the internet that can have discussions about culture war topics with even an approximation of the quality of this place. Shutting this thread down [would] not mean moving the discussion elsewhere, for a lot of people it means removing the ability to discuss these things entirely – Zornau

I feel that the CW thread, for all its flaws, occupies a certain niche that can’t easily be replicated elsewhere. I also feel that its flaws need to compared not to a Platonic ideal but to typical online political discourse, which often ends up as pure echo chambers or flame wars. – honeypuppy

It’s one of the only political forums I can read online without reaching for the nearest sharp stick to poke my eyes out. It has a sort of free-flowing conversational feel that’s really appealing. There are some thoughtful people and discussions there that I hope can continue and be preserved. – TracingWoodgrains

Thanks to a great founding population, some very hard-working moderators, and a unique rule-set that emphasized trying to understand and convince rather than yell and shame, the Culture War thread became something special. People from all sorts of political positions, from the most boring centrists to the craziest extremists, had some weirdly good discussions and came up with some really deep insights into what the heck is going on in some of society’s most explosive controversies. For three years, if you wanted to read about the socialist case for vs. against open borders, the weird politics of Washington state carbon taxes, the medieval Rule of St. Benedict compared and contrasted with modern codes of conduct, the growing world of evangelical Christian feminism, Banfield’s neoconservative perspective on class, Baudrillard’s Marxist perspective on consumerism, or just how #MeToo has led to sex parties with consent enforcers dressed as unicorns, the r/SSC culture war thread was the place to be. I also benefitted from its weekly roundup of interesting social science studies and arch-moderator baj2235’s semi-regular Quality Contributions Catch-Up Thread.

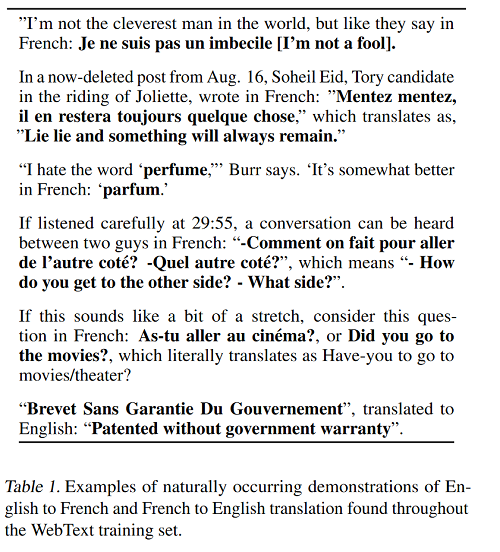

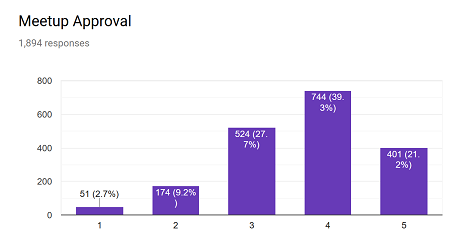

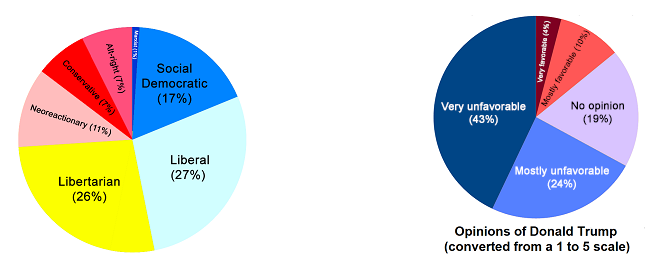

The Culture War Thread aimed to be a place where people with all sorts of different views could come together to talk to and learn from one another. I think this mostly succeeded. On the last SSC survey, I asked who participated in the thread, and used that to get a pretty good idea of its userbase. Here are some statistics:

Superficially, this is remarkably well-balanced. 51% of Culture War Thread participants identified as left-of-center on the survey, compared to 49% of people who identified as right-of-center.

There was less parity in party identification, with a bit under two Democrats to every Republican. But this, too, reflects the national picture. The latest Gallup poll found that 34% of Americans identified as Democrat, compared to only 25% Republican. Since presidential elections are usually very close, it looks like left-of-center people are more willing to openly identify with the Democratic Party than right-of-center people are with the Republicans; the CW demographics show a similar picture.

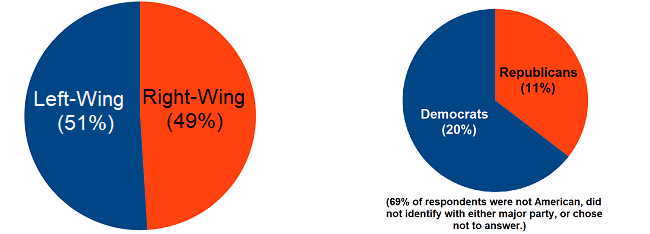

Looked at in more detail, this correspondence with the general population is not quite as perfect as it seems:

The pie chart on the left shows people broken down by a finer-grained measure of political affiliation. We see very few people identified as straight-out conservatives. Right-of-center people were more likely to be either libertarians or neoreactionaries (a technocratic, anti-democracy movement that the survey instructed people to endorse if they wanted to be more like “for example Singapore: prosperity, technology, and stability more important than democratic process”). Although straight-out “liberal” had a better showing than “conservative”, the ranks of the Left still ended up divided among left-libertarians and social democrats (which the survey instructed people to endorse if they wanted to be more like “for example Scandinavian countries: heavily-regulated market economy, cradle-to-grave social safety net, socially permissive multiculturalism”). Overall, the CW thread is a little more to the fringes on the both sides, especially the parts of the fringes popular among its young, mostly nonreligious, kind of libertarian, mostly technophile demographic.

It also doesn’t like Trump. Although he has a 40% approval rating among the general population, only about 14% of CWers were even somewhat favorable toward him. RCP suggests that anti-Trumpers outnumber pro-Trumpers in the general population by 1.4x; among CW thread participants, that number increases to almost 5x! This fits the story above where most right-of-center participants are libertarians or skeptical of democracy/populism as opposed to standard conservatives. Still, I occasionally saw Trump supporters giving their pitch in the Culture War thread, or being willing to answer questions about why they thought what they did.

During the last few years of Culture War thread, a consensus grew up that it was heavily right-wing. This isn’t what these data show, and on the few times I looked at it myself, it wasn’t what I saw either. After being challenged to back this up, I analyzed ten randomly chosen comments on the thread; four seemed neutral, three left/liberal, and three conservative. When someone else objected that it was a more specific “blatant” anti-transgender bias, I counted up all the mentions of transgender on three weeks worth of Culture War threads: of five references, two were celebrating how exciting/historic a transgender person recently winning an election was, a third was neutrally referring to the election, a fourth was a trans person talking about their experiences, and a fifth was someone else neutrally mentioning that they were transgender. This sort of thing happened enough times that I stopped being interested in arguing the point.

I acknowledge many people’s lived experience that the thread felt right-wing; my working theory is that most of the people I talk to about this kind of thing are Bay Area liberals for whom the thread was their first/only exposure to a space with any substantial right-wing presence at all, which must have made it feel scarily conservative. This may also be a question of who sorted by top, who sorted by new, and who sorted by controversial. In any case, you can just read the last few threads and form your own opinion.

Whatever its biases and whatever its flaws, the Culture War thread was a place where very strange people from all parts of the political spectrum were able to engage with each other, treat each other respectfully, and sometimes even change their minds about some things. I am less interested in re-opening the debate about exactly which side of the spectrum the average person was on compared to celebrating the rarity of having a place where people of very different views came together to speak at all.

II. We Need To Have A National Conversation About Why We Can No Longer Have A National Conversation

This post is called “RIP Culture War Thread”, so you may have already guessed things went south. What happened? The short version is: a bunch of people harassed and threatened me for my role in hosting it, I had a nervous breakdown, and I asked the moderators to get rid of it.

I’ll get to the long version eventually, but first I want to stress that this isn’t just my story. It’s the story of everyone who’s tried to host a space for political discussion on the Internet. Take the New York Times, in particular their article Why No Comments? It’s A Matter Of Resources. Translated from corporate-speak, it basically says that unmoderated comment sections had too many “trolls”, so they decided to switch to moderated comment sections only, but they don’t have enough resources to moderate any controversial articles, so commenting on controversial articles is banned.

And it’s not just the New York Times. In the past five years, CNN, NPR, The Atlantic, Vice, Bloomberg, Motherboard, and almost every other major news source has closed their comments – usually accompanied by weird corporate-speak about how “because we really value conversations, we are closing our comment section forever effective immediately”. People have written articles like The Comments Apocalypse, A Brief History Of The End Of The Comments, and Is The Era Of Reader Comments On News Websites Fading? This raises a lot of questions.

Like: I was able to find half a dozen great people to do a great job moderating the Culture War Thread 100% for free without even trying. How come some of the richest and most important news sources in the world can’t find or afford a moderator?

Or: can’t they just hide the comments behind a content warning saying “These comments are unmoderated, read at your own risk, click to expand”?

This confused me until I had my own experience with the Culture War thread.

The fact is, it’s very easy to moderate comment sections. It’s very easy to remove spam, bots, racial slurs, low-effort trolls, and abuse. I do it single-handedly on this blog’s 2000+ weekly comments. r/slatestarcodex’s volunteer team of six moderators did it every day on the CW Thread, and you can scroll through week after week of multiple-thousand-post culture war thread and see how thorough a job they did.

But once you remove all those things, you’re left with people honestly and civilly arguing for their opinions. And that’s the scariest thing of all.

Some people think society should tolerate pedophilia, are obsessed with this, and can rattle off a laundry list of studies that they say justify their opinion. Some people think police officers are enforcers of oppression and this makes them valid targets for violence. Some people think immigrants are destroying the cultural cohesion necessary for a free and prosperous country. Some people think transwomen are a tool of the patriarchy trying to appropriate female spaces. Some people think Charles Murray and The Bell Curve were right about everything. Some people think Islam represents an existential threat to the West. Some people think women are biologically less likely to be good at or interested in technology. Some people think men are biologically more violent and dangerous to children. Some people just really worry a lot about the Freemasons.

Each of these views has adherents who are, no offense, smarter than you are. Each of these views has, at times, won over entire cultures so completely that disagreeing with them then was as unthinkable as agreeing with them is today. I disagree with most of them but don’t want to be too harsh on any of them. Reasoning correctly about these things is excruciatingly hard, trusting consensus opinion would have led you horrifyingly wrong throughout most of the past, and other options, if they exist, are obscure and full of pitfalls. I tend to go with philosophers from Voltaire to Mill to Popper who say the only solution is to let everybody have their say and then try to figure it out in the marketplace of ideas.

But none of those luminaries had to deal with online comment sections.

The thing about an online comment section is that the guy who really likes pedophilia is going to start posting on every thread about sexual minorities “I’m glad those sexual minorities have their rights! Now it’s time to start arguing for pedophile rights!” followed by a ten thousand word manifesto. This person won’t use any racial slurs, won’t be a bot, and can probably reach the same standards of politeness and reasonable-soundingness as anyone else. Any fair moderation policy won’t provide the moderator with any excuse to delete him. But it will be very embarrassing for to New York Times to have anybody who visits their website see pro-pedophilia manifestos a bunch of the time.

“So they should deal with it! That’s the bargain they made when deciding to host the national conversation!”

No, you don’t understand. It’s not just the predictable and natural reputational consequences of having some embarrassing material in a branded space. It’s enemy action.

Every Twitter influencer who wants to profit off of outrage culture is going to be posting 24-7 about how the New York Times endorses pedophilia. Breitbart or some other group that doesn’t like the Times for some reason will publish article after article on New York Times‘ secret pro-pedophile agenda. Allowing any aspect of your brand to come anywhere near something unpopular and taboo is like a giant Christmas present for people who hate you, people who hate everybody and will take whatever targets of opportunity present themselves, and a thousand self-appointed moral crusaders and protectors of the public virtue. It doesn’t matter if taboo material makes up 1% of your comment section; it will inevitably make up 100% of what people hear about your comment section and then of what people think is in your comment section. Finally, it will make up 100% of what people associate with you and your brand. The Chinese Robber Fallacy is a harsh master; all you need is a tiny number of cringeworthy comments, and your political enemies, power-hungry opportunists, and 4channers just in it for the lulz can convince everyone that your entire brand is about being pro-pedophile, catering to the pedophilia demographic, and providing a platform for pedophile supporters. And if you ban the pedophiles, they’ll do the same thing for the next-most-offensive opinion in your comments, and then the next-most-offensive, until you’ve censored everything except “Our benevolent leadership really is doing a great job today, aren’t they?” and the comment section becomes a mockery of its original goal.

So let me tell you about my experience hosting the Culture War thread.

(“hosting” isn’t entirely accurate. The Culture War thread was hosted on the r/slatestarcodex subreddit, which I did not create and do not own. I am an honorary moderator of that subreddit, but aside from the very occasional quick action against spam nobody else caught, I do not actively play a part in its moderation. Still, people correctly determined that I was probably the weakest link, and chose me as the target.)

People settled on a narrative. The Culture War thread was made up entirely of homophobic transphobic alt-right neo-Nazis. I freely admit there were people who were against homosexuality in the thread (according to my survey, 13%), people who opposed using trans people’s preferred pronouns (according to my survey, 9%), people who identified as alt-right (7%), and a single person who identified as a neo-Nazi (who as far as I know never posted about it). Less outrageous ideas were proportionally more popular: people who were mostly feminists but thought there were differences between male and female brains, people who supported the fight against racial discrimination but thought could be genetic differences between races. All these people definitely existed, some of them in droves. All of them had the right to speak; sometimes I sympathized with some of their points. If this had been the complaint, I would have admitted to it right away. If the New York Times can’t avoid attracting these people to its comment section, no way r/ssc is going to manage it.

But instead it was always that the the thread was “dominated by” or “only had” or “was an echo chamber for” homophobic transphobic alt-right neo-Nazis, which always grew into the claim that the subreddit was dominated by homophobic etc neo-Nazis, which always grew into the claim that the SSC community was dominated by homophobic etc neo-Nazis, which always grew into the claim that I personally was a homophobic etc neo-Nazi of them all. I am a pro-gay Jew who has dated trans people and votes pretty much straight Democrat. I lost distant family in the Holocaust. You can imagine how much fun this was for me.

People would message me on Twitter to shame me for my Nazism. People who linked my blog on social media would get replies from people “educating” them that they were supporting Nazism, or asking them to justify why they thought it was appropriate to share Nazi sites. I wrote a silly blog post about mathematics and corn-eating. It reached the front page of a math subreddit and got a lot of upvotes. Somebody found it, asked if people knew that the blog post about corn was from a pro-alt-right neo-Nazi site that tolerated racists and sexists. There was a big argument in the comments about whether it should ever be acceptable to link to or read my website. Any further conversation about math and corn was abandoned. This kept happening, to the point where I wouldn’t even read Reddit discussions of my work anymore. The New York Times already has a reputation, but for some people this was all they’d heard about me.

Some people started an article about me on a left-wing wiki that listed the most offensive things I have ever said, and the most offensive things that have ever been said by anyone on the SSC subreddit and CW thread over its three years of activity, all presented in the most damning context possible; it started steadily rising in the Google search results for my name. A subreddit devoted to insulting and mocking me personally and Culture War thread participants in general got started; it now has over 2,000 readers. People started threatening to use my bad reputation to discredit the communities I was in and the causes I cared about most.

Some people found my real name and started posting it on Twitter. Some people made entire accounts devoted to doxxing me in Twitter discussions whenever an opportunity came up. A few people just messaged me letting me know they knew my real name and reminding me that they could do this if they wanted to.

Some people started messaging my real-life friends, telling them to stop being friends with me because I supported racists and sexists and Nazis. Somebody posted a monetary reward for information that could be used to discredit me.

One person called the clinic where I worked, pretended to be a patient, and tried to get me fired.

(not all of this was because of the Culture War thread. Some of this was because of my own bad opinions and my own bad judgment. But the Culture War thread kept coming up. As I became more careful in my own writings, the Culture War thread loomed larger and larger in the threats and complaints. And when the Culture War thread got closed down, the subreddit about insulting me had a “declaring victory” post, which I interpret as confirmation that this was one of the main things going on.)

I don’t want to claim martyrdom. None of these things actually hurt me in real life. My blog continues to be popular, my friends stuck by me, and my clinic didn’t let me go. I am not going to be able to set up a classy new FiredForTruth.com website like James Damore did. What actually happened was much more prosaic: I had a nervous breakdown.

It wasn’t even that bad a nervous breakdown. I was able to keep working through it. I just sort of broke off all human contact for a couple of weeks and stayed in my room freaking out instead. This is similar enough to my usual behavior that nobody noticed, which suited me fine. And I learned a lot (for example, did you know that sceletium has a combination of SSRI-like compounds and PDE2 inhibitors that make it really good at treating nervous breakdowns? True!). And it wasn’t like the attacks were objectively intolerable or that everybody would have had a nervous breakdown in my shoes: I’m a naturally obsessive person, I take criticism especially badly, and I had some other things going on too.

Around the same time, friends of mine who were smarter and more careful than I was started suggesting that it would be better for me, and for them as people who had to deal with the social consequences of being my friend, if I were to shut down the thread. And at the same time, I got some more reasons to think that this blog could contribute to really important things – AI, effective charity, meta-science – in ways that would be harder to do from the center of a harassment campaign.

So around October, I talked to some subreddit mods and asked them what they thought about spinning off the Culture Wars thread to its own forum, one not affiliated with the Slate Star Codex brand or the r/slatestarcodex subreddit. The first few I approached were positive; some had similar experiences to mine; one admitted that even though he personally was not involved with the CW thread and only dealt with other parts of the subreddit, he taught at a college and felt like his job would not be safe so long as the subreddit and CW thread were affiliated. Apparently the problem was bigger than just me, and other people had been dealing with it in silence.

Other moderators, the ones most closely associated with the CW thread itself, were strongly opposed. They emphasized some of the same things I emphasized above: that the thread was a really unique place for great conversation about all sorts of important topics, that the majority of commenters and posts were totally inoffensive, and that one shouldn’t give in to terrorists. I respect all these points, but I respected them less from the middle of a nervous breakdown, and eventually the vote among the top nine mods and other stakeholders was 5-4 in favor of getting rid of it. It took three months to iron out all the details, but a few weeks ago everyone finally figured things out and the CW thread closed forever.

At this point this stops being my story. A group of pro-CW-thread mods led by ZorbaTHut, cjet79, and baj2235 set up r/TheMotte, a new subreddit for continuing the Culture War Thread tradition. After a week, the top post already has 4,243 comments, so it looks like the move went pretty well. Despite fears – which I partly shared – that the transition would not be good for the Thread, early signs suggest it has survived intact. I’m hopeful this can be a win-win situation, freeing me from a pretty serious burden while the Thread itself expands and flourishes under the leadership of a more anonymous group of people.

III. The Thread Is Dead, Long Live The Thread

I debated for a long time whether or not to write this post. The arguments against are obvious: never let the trolls know they’re getting to you. Once they know they’re getting to you, that you’re susceptible to pressure, obviously they redouble their efforts. I stuck to this for a long time. I’m still sort of sticking to it, in that I’m avoiding specifics and super avoiding links (which I realize has made my story harder to prove true, sorry). I’ll try to resume the policy fully after this, but I thought one post on the subject was worth the extra misery for a few reasons.

First, a lot of people were (rightfully! understandably!) very angry about the loss of the Culture War thread from r/ssc, and told the moderators that, as the kids say these days, “a decent respect to the opinions of mankind requires that they should declare the causes which impel them to the separation”. I promised to do this, so now I am.

Second, I wanted there to be at least one of these “here’s why we’re removing your ability to comment” articles that was honest, not made of corporate-speak, and less patronizing than “we’re removing the comment section because we value your speech so much and want to promote great conversations”. Hopefully this will be the skeleton key that helps you understand what all those other articles would have said if they weren’t run through fifty layers of PR teams. I would like to give people another perspective on events like Tumblr banning female-presenting nipples or Patreon dropping right-wing YouTubers or Twitter constantly introducing new algorithms that misfire and ban random groups of people. These companies aren’t inherently censorious. They’re just afraid. Everyone is afraid.

Third, I would like to offer one final, admittedly from-a-position-of-weakness, f**k you at everyone who contributed to this. I think you’re bad people, and you make me really sad. Not in a joking performative Internet sadness way. In an actual, I-think-you-made-my-life-and-the-world-worse way. I realize I’m mostly talking to the sort of people who delight in others’ distress and so this won’t register. But I’m also a little upset at some of my (otherwise generally excellent) friends in the rationalist community who were quick to jump on the “Oh, yeah, the SSC subreddit is full of gross people and I wish they couldn’t speak” bandwagon (to be clear, I don’t mean the friends who offered me good advice about separating from the CW thread for the sake of my own well-being, I mean people who actively contributed to worsening the whole community’s reputation based on a few bad actors). I understand you were probably honest in your opinion, but I think there was a lot of room to have thought through those opinions more carefully.

Fourth, I want anybody else trying to host “the national conversation” to have a clear idea of the risks. If you plan to be anything less than maximally censorious, consider keeping your identity anonymous, and think about potential weak links in your chain (ie hosts, advertisers, payment processors, etc). I’m not saying you necessarily need to go full darknet arms merchant. Just keep in mind that lots of people will try to stop you, and they’ve had a really high success rate so far.

Fifth, if someone speaks up against the increasing climate of fear and harassment or the decline of free speech, they get hit with an omnidirectional salvo of “You continue to speak just fine, and people are listening to you, so obviously the climate of fear can’t be too bad, people can’t be harassing you too much, and you’re probably just lying to get attention.” But if someone is too afraid to speak up, or nobody listens to them, then the issue never gets brought up, and mission accomplished for the people creating the climate of fear. The only way to escape the double-bind is for someone to speak up and admit “Hey, I personally am a giant coward who is silencing himself out of fear in this specific way right now, but only after this message”. This is not a particularly noble role, but it’s one I’m well-positioned to play here, and I think it’s worth the awkwardness to provide at least one example that doesn’t fit the double-bind pattern.

Sixth, I want to apologize to anybody who’s had to deal with me the past – oh, let’s say several years. One of the really bad parts of this debacle has been that it’s made me a much worse person. When I started writing this blog, I think I was a pretty nice person who was willing to listen to and try to hammer out my differences with anyone. As a result of some of what I’ve described, I think I’ve become afraid, bitter, paranoid, and quick to assume that anyone who disagrees with me (along a dimension that too closely resembles some of the really bad people I’ve had to deal with) is a bad actor who needs to be discredited and destroyed. I don’t know how to fix this. I can only apologize for it, admit you’re not imagining it, and ask people to do as I say (especially as I said a few years ago when I was a better person) and not as I do. I do think this is a great learning experience in terms of psychology and will write a post on it eventually; I just wish I didn’t have to learn it from the inside.

Seventh, I want to reassure people who would otherwise treat this story as an unmitigated disaster that there are some bright spots, like that I didn’t suffer any objective damage despite a lot of people trying really hard, and that the Culture War thread lives on bigger and brighter than ever before

Eighth, as a final middle-finger at the people who killed the Culture War thread, I’d like to advertise r/TheMotte, its new home, in the hopes that this whole debacle Streisand-Effects it to the stratosphere.

I want to stress that I will continue to leave the SSC comment section open as long as is compatible with the political climate and my own health; I ask tolerance if there are otherwise-unfair actions I have to take to make this possible. I also want to stress that I’m not going to stop writing about controversial topics completely – but I do want to have some control over when and where I have to deal with this, and want the privilege of being hung for my own opinions rather than for those of other people I am tangentially associated with.

Please do not send me expressions of sympathy or try to cast me as a martyr; the first make me feel worse for reasons that are hard to explain; the second wouldn’t really fit the facts and isn’t the look I want to present. Thanks to everyone who helped make the CW thread and this blog what it was/is, and good luck to Zorba and the rest of the Motte moderation team.