I.

One of psychiatry’s many embarrassments is how many of our drugs get discovered by accident. They come from random plants or shiny rocks or stuff Alexander Shulgin invented to get high.

But every so often, somebody tries to do things the proper way. Go over decades of research into what makes psychiatric drugs work and how they could work better. Figure out the hypothetical properties of the ideal psych drug. Figure out a molecule that matches those properties. Synthesize it and see what happens. This was the vision of vortioxetine and vilazodone, two antidepressants from the early 2010s. They were approved by the FDA, sent to market, and prescribed to millions of people. Now it’s been enough time to look back and give them a fair evaluation. And…

…and it’s been a good reminder of why we don’t usually do this.

Enough data has come in to be pretty sure that vortioxetine and vilazodone, while effective antidepressants, are no better than the earlier medications they sought to replace. I want to try going over the science that led pharmaceutical companies to think these two drugs might be revolutionary, and then speculate on why they weren’t. I’m limited in this by my total failure to understand several important pieces of the pathways involved, so I’ll explain the parts I get, and list the parts I don’t in the hopes that someone clears them up in the comments.

II.

SSRIs take about a month to work. This is surprising, because they start increasing serotonin immediately. If higher serotonin is associated with improved mood, why the delay?

Most research focuses on presynaptic 5-HT1A autoreceptors, which detect and adjust the amount of serotonin being released in order to maintain homeostasis. If that sounds clear as mud to you, well, it did to me too the first twenty times I heard it. Here’s the analogy which eventually worked for me:

Imagine you’re a salesperson who teleconferences with customers all day. You’re bad at projecting your voice – sometimes it’s too soft, sometimes too loud. Your boss tells you the right voice level for sales is 60 decibels. So you put an audiometer on your desk that measures how many decibels your voice is. It displays an up arrow, down arrow, or smiley face, telling you that you’re being too quiet, loud, or just right.

The audiometer is presynaptic (it’s on your side of the teleconference, not your customer’s side). It’s an autoreceptor, not a heteroreceptor (you’re using it to measure yourself, not to measure anything else). And you’re using it to maintain homeostasis (to keep your voice at 60 dB).

Suppose you take a medication that stimulates your larynx and makes your voice naturally louder. As long as your audiometer’s working, that medication will have no effect. Your voice will naturally be louder, but that means you’ll see the down arrow on your audiometer more often, you’ll speak with less force, and the less force and louder voice will cancel out and keep you at 60 dB. No change.

This is what happens with antidepressants. The antidepressant increases serotonin levels (ie sends a louder signal). But if the presynaptic 5-HT1A autoreceptors are intact, they tell the cells that the signal is too loud and they should release less serotonin. So they do, and now we’re back where we started – ie depressed.

(Why don’t the autoreceptors notice the original problem – that you have too little serotonin and are depressed – and work their magic there? Not sure. Maybe depression affects whatever sets the autoreceptors, and causes them to be set too low? Maybe the problem is with reception, not transmission? Maybe you have the right amount of serotonin, but you want excessive amounts of serotonin because that would fix a problem somewhere else? Maybe you should have paid extra for the premium model of presynaptic autoreceptor?)

So how come antidepressants work after a month? The only explanation I’ve heard is that the autoreceptors get “saturated”, which is a pretty nonspecific term. I think it means that there’s a second negative feedback loop controlling the first negative feedback loop – the cell notices there is way more autoreceptor activity than expected and assumes it is producing too many autoreceptors. Over the course of a month, it stops producing more autoreceptors, the existing autoreceptors gradually degrade, and presynaptic autoreception stops being a problem. In our salesperson analogy, after a while you notice that your audiometer doesn’t match your own perception of how much effort you’re putting into speaking – no matter how quietly you feel like you’re whispering, the audiometer just keeps saying you’re yelling very loud. Eventually you declare it defective, throw it out, and just speak naturally. Now the larynx-stimulating medication can make your voice louder.

In the late ’90s, some scientists wondered – what happens if you just block the 5-HT1A autoreceptors directly? At the very least, seems like you could make antidepressants work a month faster. Best case scenario, you can make antidepressants work better. Maybe after a month, the cells have lost some confidence in the autoreceptors, but they’re still keeping serotonin somewhere below the natural amount based on the anomalous autoreceptor reading. So maybe blocking the autoreceptors would mean a faster, better, antidepressant.

Luckily we already knew a chemical that could block these – pindolol. Pindolol is a blood-pressure-lowering medication, but by coincidence it also makes it into the brain and blocks this particular autoreceptor involved in serotonin homeostasis. So a few people started giving pindolol along with antidepressants. What happened? According to some small unconvincing systematic reviews, it did seem to kind of help make antidepressants work faster, but according to some other small unconvincing meta-analyses it probably didn’t make them work any better. It just made antidepressants go from taking about four weeks to work, to taking one or two weeks to work. It also gave patients dizziness, drowsiness, weakness, and all the other things you would expect from giving a blood-pressure-lowering medication to people with normal blood pressure. So people decided it probably wasn’t worth it.

III.

And then there’s buspirone.

Buspirone is generally considered a 5-HT1A agonist. The reality is a little more complicated; it’s a full agonist of presynaptic autoreceptors, and a partial agonist of postsynaptic autoreceptors(uh, imagine the customer in the other side of the teleconference also has an audiometer).

Buspirone has a weak anti-anxiety effect. It may also weakly increase sex drive, which is a nice contrast to SSRIs, which decrease (some would say “destroy”) sex drive. Flibanserin, a similar drug, is FDA-approved as a sex drive enhancer.

Buspirone stimulates presynaptic autoreceptors, which should cause cells to release less serotonin. Since high serotonin levels (eg with SSRIs) decreases sex drive, it makes sense that buspirone should increase sex drive. So far, so good.

But why is buspirone anxiolytic? I have just read a dozen papers purporting to address this question, and they might as well have been written in Chinese for all I was able to get from them. Some of them just say that decreasing serotonin levels decreases anxiety, which would probably come as a surprise to anyone on SSRIs, anyone who does tryptophan depletion studies, anyone who measures serotonin metabolites in the spinal fluid, etc. Obviously it must be more complicated than this. But how? I can’t find any explanation.

A few books and papers take a completely different tack and argue that buspirone just does the same thing SSRIs do – desensitize the presynaptic autoreceptors until the cells ignore them – and then has its antianxiety action through stimulating postsynaptic receptors. But if it’s doing the same thing as SSRIs, how come it has the opposite effect on sex drive? And how come there are some studies suggesting that it’s helpful to add buspirone onto SSRIs? Why isn’t that just doubling up on the same thing?

I am deeply grateful to SSC commenter Scchm for presenting an argument that this is all wrong, and buspirone acts on D4 receptors, both in its anxiolytic and pro-sexual effects. This would neatly resolve the issues above. But then how come nobody else mentions this? How come everyone else seems to think buspirone makes sense, and writes whole papers about it without using the sentence “what the hell all of this is crazy”?

And here’s one more mystery: after the pindolol studies, everyone just sort of started assuming buspirone would work the same way pindolol did. This doesn’t really make sense pharmacologically – pindolol is an antagonist at presynaptic 5-HT1A receptors; buspirone is an agonist of same. And it doesn’t actually work in real life – someone did a study, and the study found it didn’t work. Still, and I have no explanation for this, people got excited about this possibility. If buspirone could work like pindolol, then we would have a chemical that made antidepressants work faster, and treated anxiety, and reduced sexual dysfunction.

And here’s one more mystery – okay, you have unrealistically high expectations for buspirone, fine, give people buspirone along with their SSRI. Lots of psychiatrists do this, it’s not really my thing, but it’s not a bad idea. But instead, the people making this argument became obsessed with the idea of finding a single chemical that combined SSRI-like activity with buspirone-like activity. A dual serotonin-transporter-inhibitor and 5-HT1A partial agonist became a pharmacological holy grail.

IV.

After a lot of people in lab coats poured things from one test tube to another, Merck announced they had found such a chemical, which they called vilazodone (Viibryd®).

Vilazodone is an SSRI and 5-HT1A partial agonist. I can’t find how its exact partial agonist profile differs from buspirone, except that it’s more of a postsynaptic agonist, whereas buspirone is more of a postsynaptic antagonist. I don’t know if this makes a difference.

The FDA approved vilazodone to treat depression, so it “works” in that sense. But does its high-tech promise pan out? Is it really faster-acting, anxiety-busting, and less likely to cause sexual side effects?

On a chemical level, things look promising. This study finds that vilazodone elevates serotonin faster and higher than Prozac does in mice. And this is kind of grim, but toxicologists have noticed that vilazodone overdoses are much more likely to produce serotonin toxicity than Prozac overdoses, which fits what you would expect if vilazodone successfully breaks the negative feedback system that keeps serotonin in a normal range.

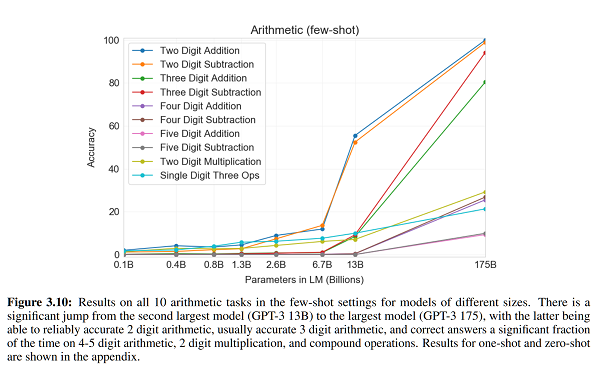

On a clinical level, maybe not. Proponents of vilazodone got excited about a study where vilazodone showed effects as early as week two. But “SSRIs take four weeks to work” is a rule of thumb, not a natural law. You always get a couple of people who get some effect early on, and if your study population is big enough, that’ll show up as a positive result. So you need to compare vilazodone to an SSRI directly. The only group I know who tried this, Matthews et al, found no difference – in fact, vilazodone was nonsignificantly slower (relevant figure). There’s no sign of vilazodone working any better either.

What about sexual side effects? Vilazodone does better than SSRIs in rats, but whatever. There’s supposedly a human study – from the same Matthews et al team as above – but sexual side effects were so rare in all groups that it’s hard to draw any conclusions. This is bizarre – they had a thousand patients, and only 15 reported decreased libido (and no more in the treatment groups than the placebo group). Maybe God just hates antidepressant studies and makes sure they never find anything, and this is just as true when you’re studying side effects as it is when you’re studying efficacy.

Clayton et al do their own study of vilazodone’s sexual side effects. They find that overall vilazodone improves sexual function over placebo, probably because they used a scale that was very sensitive to the kind of bad sexual function you get when you’re depressed, and not as sensitive to the kind you get on antidepressants. But they did measure how many people who didn’t start out with sexual dysfunction got it during the trial, and this number was 1% of the placebo group and 8% of the vilazodone group. How many people would have gotten dysfunction on an SSRI? We don’t know because they didn’t include an active comparator. Usually I expect about 30 – 50% of people to get sexual side effects on SSRIs, but that’s based on me asking them and not on whatever strict criteria they use for studies. Remember, the Matthews study was able to find only 1.5% of people getting sexual side effects! So we shouldn’t even try to estimate how this compares. All we can say is that vilazodone definitely doesn’t have no sexual side effects.

I can’t find any studies evaluating vilazodone vs. anything else for anxiety, but I also can’t find any patients saying vilazodone treated their anxiety especially well.

There’s really only one clear and undeniable difference between vilazodone and ordinary SSRIs, which is that vilazodone costs $290 a month, whereas other SSRIs cost somewhere in the single digits (Lexapro costs $7.31). If you’re paying for vilazodone, you can take comfort in knowing your money helped fund a pretty cool research program that had some interesting science behind it. But I’m not sure it actually panned out.

V.

Encouraged by Merck’s success…

(not necessarily clinical success, success at getting people to pay $290 a month for an antidepressant)

…Takeda and Lundbeck announced their own antidepressant with 5-HT1A partial agonist action, vortioxetine. They originally gave it the trade name Brintellix®, but upon its US release people kept confusing it with the unrelated medication Brilinta®, so Takeda/Lundbeck agreed to change the name to Trintellix® for the American market.

Vortioxetine claimed to have an advantage over its competitor vilazodone, in that it also antagonized 5-HT3 receptors. 5-HT3 receptors are weird. They’re the only ion channel based serotonin receptors, and they’re not especially involved in mood or anxiety. They do only one thing, and they do it well: they make you really nauseous. If you’ve ever felt nauseous on an SSRI, 5-HT3 agonism is why. And if you’ve ever taken Zofran (ondansetron) for nausea, you’ve benefitted from its 5-HT3 antagonism. Most antidepressants potentially cause nausea; since vortioxetine also treats nausea, presumably you break even and are no more nauseous than you were before taking it. Also, there are complicated theoretical reasons to believe maybe 5-HT3 antagonism is kind of like 5-HT1A antagonism in that it speeds the antidepressant response.

After this Takeda and Lundbeck kind of just went crazy, claiming effects on more and more serotonin receptors. It’s a 5-HT7 antagonist! (what is 5-HT7? No psychiatrist had ever given a second’s thought to this receptor before vortioxetine came out, but apparently it…exists to make your cognition worse, so that blocking it makes your cognition better again?) It’s a 5-HT1B partial agonist! (what is 5-HT1B? Apparently a useful potential depression target, according to a half-Japanese, half-Scandinavian team, who report no conflict of interest even though vortioxetine is being sold by a consortium of a Japanese pharma company and a Scandinavian pharma company). It’s a 5-HT1D antagonist! (really? There are four different kinds of 5-HT1 receptor? Are you sure you’re not just making things up now?)

If we take all of this seriously, vortioxetine is an SSRI with faster mechanism of action, fewer sexual side effects, additional anti-anxiety effect, additional anti-nausea effect, plus it gives you better cognition (technically “relieves the cognitive symptoms of depression”). Is any of this at all true?

A meta-analysis of 12 studies finds vortioxetine has a statistically significant but pathetic effect size of 0.2 against depression, which is about average for antidepressants. In a few head-to-head comparisons with SNRIs (similar to SSRIs), vortioxetine treats depression about equally well. Patients are more likely to stop the SNRIs because of side effects than to stop the vortioxetine, but SNRIs probably have more side effects than SSRIs, so unclear if vortioxetine is better than those. Wagner et al are able to find a study comparing vortioxetine to the SSRI Paxil; they work about equally well.

What about the other claims? Weirdly, vortioxetine patients have more nausea and vomiting than venlafaxine patients, although it’s not significant. Other studies confirm nausea is a pretty serious vortioxetine side effect. I have no explanation for this. Antagonizing 5-HT3 receptors does one thing – treats nausea and vomiting! – and vortioxetine definitely does this. It must be hitting some other unknown receptor really hard, so hard that the 5-HT3 antagonism doesn’t counterbalance it. Either that, or it’s the thing where God hates antidepressants again.

What about sexual dysfunction? Jacobsen et al find that patients have slightly (but statistically significantly) less sexual dysfunction on vortioxetine than on escitalopram. But the study was done by Takeda, and the difference is so slight (a change of 8.8 points on a 60 point scale, vs. a change of 6.6 points) that it’s hard to take it very seriously.

What about cognition? I was sure this was fake, but it seems to have more evidence behind it than anything else. Carlat Report (paywalled) thinks it might be legit, based on a series of (Takeda-sponsored) studies of performance on the Digit Symbol Substitution Test. People on vortioxetine consistently did better on this test than people on placebo or duloxetine. And it wasn’t just that being not-depressed helps you try harder; they did some complicated statistics and found that vortioxetine’s test-score-improving effect was independent of its antidepressant effect (and seems to work at lower doses). What’s the catch? The improvement was pretty minimal, and only shows up on this one test – various other cognitive tests are unaffected. So it’s probably doing something measurable, but it’s not going to give you a leg up on the SAT. The FDA seriously considered approving it as indicated for helping cognition, but eventually decided against it on the grounds that if they approved it, people would think it was useful in real life, whereas all we know is that it’s useful on this one kind of hokey test. Still, that’s one hokey test more than vilazodone was ever able to show for itself.

In summary, vortioxetine probably treats depression about as well as any other antidepressant, but makes you slightly more nauseous, may (if you really trust pharma company studies) give you slightly fewer sexual side effects, and may improve your performance on the Digit Symbol Substitution Test. It also costs $375 a month (Lexapro still costs $7). If you want to pay $368 extra to be a little more nauseous and substitute digits for symbols a little faster, this is definitely the drug for you.

VI.

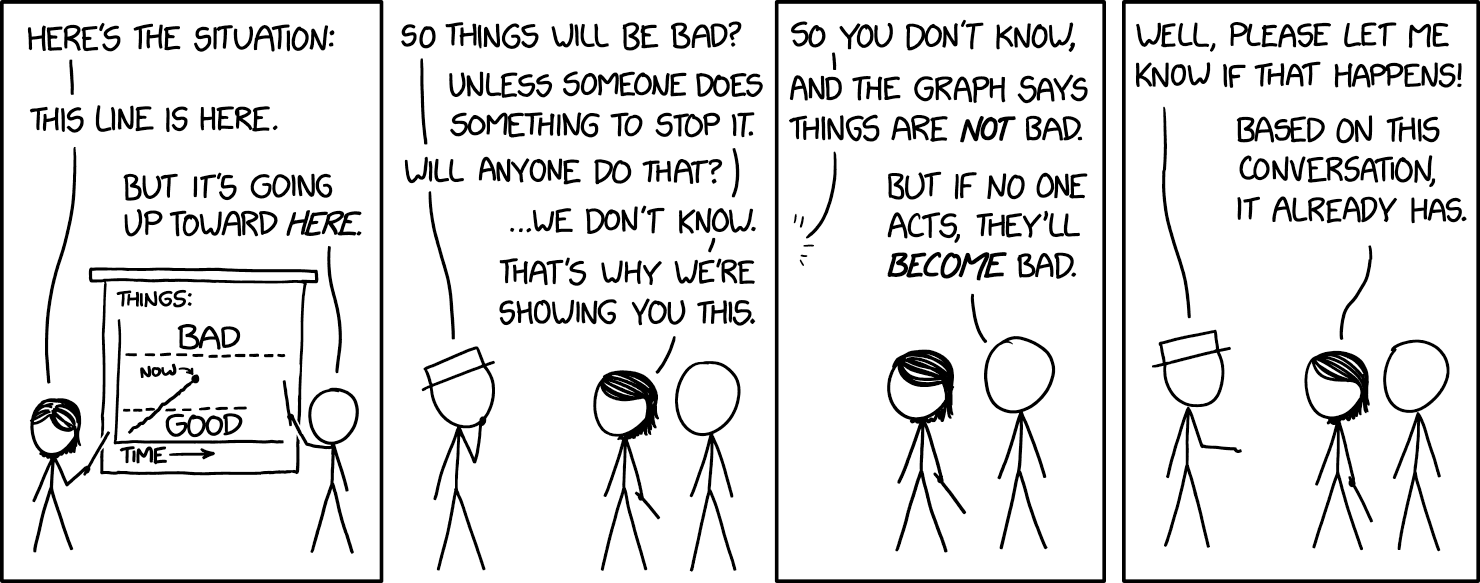

In conclusion, big pharma spent about ten years seeing if combining 5-HT1A partial agonism with SSRI antidepressants led to any benefits. In the end, it didn’t, unless you count benefits to big pharma’s bottom line.

I’m a little baffled, because pharma companies generally don’t waste money researching drugs unless they have very good theoretical reasons to think they’ll work. But I can’t make heads or tails of the theoretical case for 5-HT1A partial agonists for depression.

For one thing, there’s a pretty strong argument that buspirone exerts its effects via dopamine rather than serotonin – a case that it seems like nobody, including the pharma companies, is even slightly aware of. If this were true, the whole project would have been doomed from the beginning. What happened here?

For another, I still don’t get the supposed model for how buspirone even could exert its effects through 5-HT1A. Does it increase or decrease serotonergic transmission? Does it desensitize presynaptic autoreceptors the same way SSRIs do, or do something else? I can’t figure out a combination of answers to this question that are consistent with each other and with the known effects of these drugs. Is there one?

For another, the case seems to have been premised on the idea that buspirone (a presynaptic 5-HT1A agonist) would work the same as pindolol (a presynaptic 5-HT1A antagonist), even after studies showed that it didn’t. And then it combined that with an assumption that it was better to spend hundreds of millions of dollars discovering a drug that combined SSRI and buspirone-like effects, rather than just giving someone a pill of SSRI powder mixed with buspirone powder. Why?

I would be grateful if some friendly pharmacologist reading this were to comment with their take on these questions. This is supposed to be my area of expertise, and I have to admit I am stumped.