I.

I recently reviewed Secular Cycles, which presents a demographic-structural theory of the growth and decline of pre-industrial civilizations. When land is plentiful, population grows and the economy prospers. When land reaches its carrying capacity and income declines to subsistence, the area is at risk of famines, diseases, and wars – which kill enough people that land becomes plentiful again. During good times, elites prosper and act in unity; during bad times, elites turn on each other in an age of backstabbing and civil strife. It seemed pretty reasonable, and authors Peter Turchin and Sergey Nefedov had lots of data to support it.

Ages of Discord is Turchin’s attempt to apply the same theory to modern America. There are many reasons to think this shouldn’t work, and the book does a bad job addressing them. So I want to start by presenting Turchin’s data showing such cycles exist, so we can at least see why the hypothesis might be tempting. Once we’ve seen the data, we can decide how turned off we want to be by the theoretical problems.

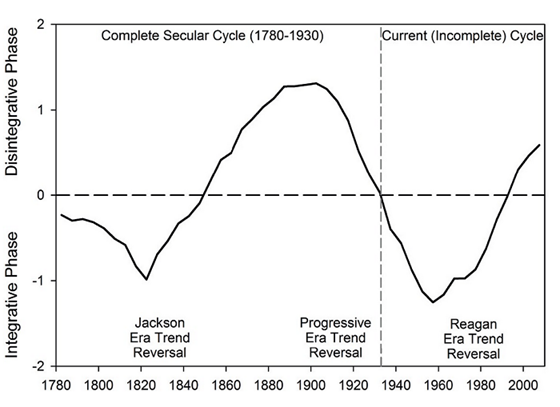

The first of Turchin’s two cyclic patterns is a long cycle of national growth and decline. In Secular Cycles‘ pre-industrial societies, this pattern lasted about 300 years; in Ages of Discord‘s picture of the modern US, it lasts about 150:

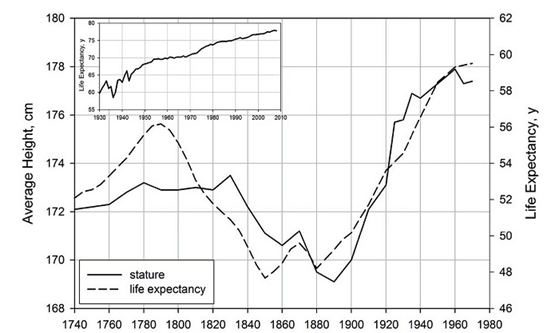

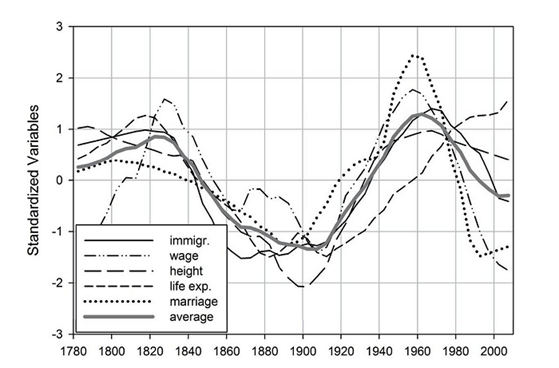

This summary figure combines many more specific datasets. For example, archaeologists frequently assess the prosperity of a period by the heights of its skeletons. Well-nourished, happy children tend to grow taller; a layer with tall skeletons probably represents good times during the relevant archaeological period; one with stunted skeletons probably represents famine and stress. What if we applied this to the modern US?

Average US height and life expectancy over time. As far as I can tell, the height graph is raw data. The life expectancy graph is the raw data minus an assumed constant positive trend – that is, given that technological advance is increasing life expectancy at a linear rate, what are the other factors you see when you subtract that out? The exact statistical logic be buried in Turchin’s source (Historical Statistics of the United States, Carter et al 2004), which I don’t have and can’t judge.

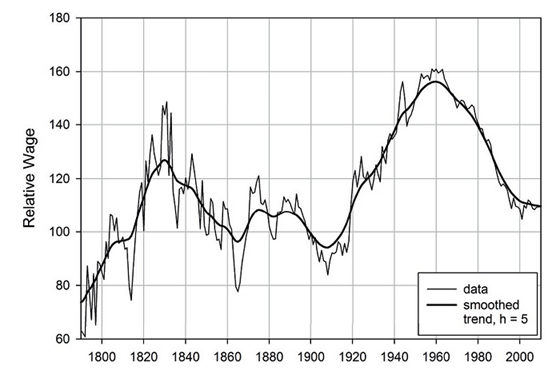

This next graph is the median wage divided by GDP per capita, a crude measure of income equality:

Lower values represent more inequality.

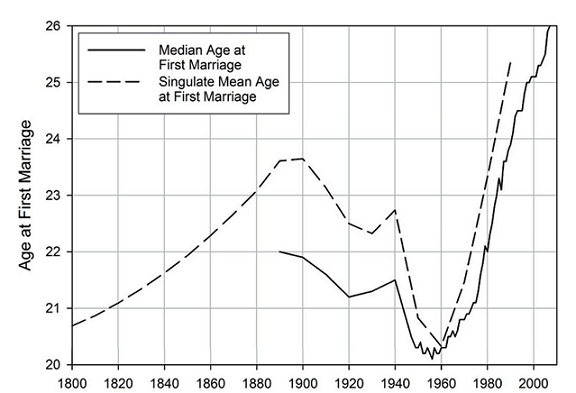

This next graph is median female age at first marriage. Turchin draws on research suggesting this tracks social optimism. In good times, young people can easily become independent and start supporting a family; in bad times, they will want to wait to make sure their lives are stable before settling down:

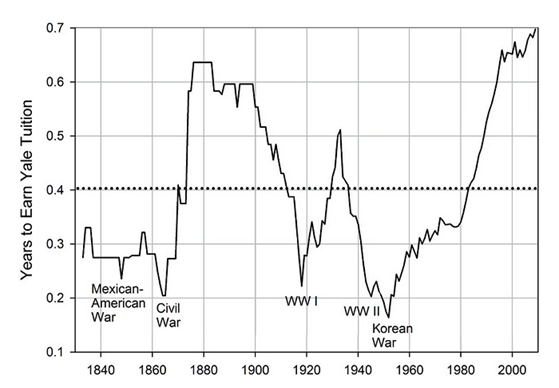

This next graph is Yale tuition as a multiple of average manufacturing worker income. To some degree this will track inequality in general, but Turchin thinks it also measures something like “difficulty of upward mobility”:

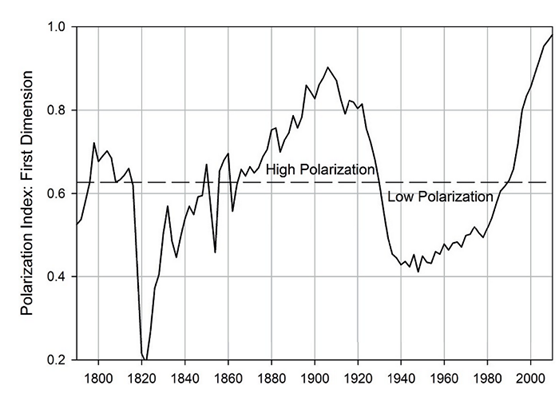

This next graph shows DW-NOMINATE’s “Political Polarization Index”, a complicated metric occasionally used by historians of politics. It measures the difference in voting patterns between the average Democrat in Congress and the average Republican in Congress (or for periods before the Democrats and Republicans, whichever two major parties there were). During times of low partisanship, congressional votes will be dominated by local or individual factors; during times of high partisanship, it will be dominated by party identification:

I’ve included only those graphs which cover the entire 1780 – present period; the book includes many others that only cover shorter intervals (mostly the more recent periods when we have better data). All of them, including the shorter ones not included here, reflect the same general pattern. You can see it most easily if you standardize all the indicators to the same scale, match the signs so that up always means good and down always means bad, and put them all together:

Note that these aren’t exactly the same indicators I featured above; we’ll discuss immigration later.

The “average” line on this graph is the one that went into making the summary graphic above. Turchin believes that after the American Revolution, there was a period of instability lasting a few decades (eg Shays’ Rebellion, Whiskey Rebellion) but that America reached a maximum of unity, prosperity, and equality around 1820. Things gradually got worse from there, culminating in a peak of inequality, misery, and division around 1900. The reforms of the Progressive Era gradually made things better, with another unity/prosperity/equality maximum around 1960. Since then, an increasing confluence of negative factors (named here as the Reagan Era trend reversal, but Turchin admits it began before Reagan) has been making things worse again.

II.

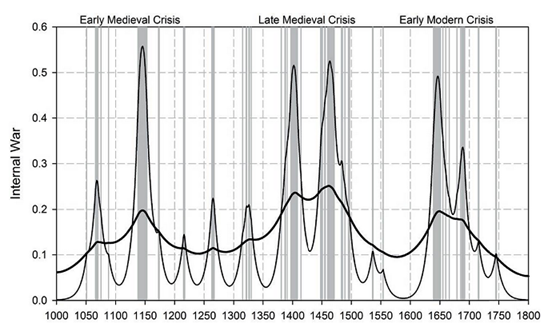

Along with this “grand cycle” of 150 years, Turchin adds a shorter instability cycle of 40-60 years. This is the same 40-60 year instability cycle that appeared in Secular Cycles, where Turchin called it “the bigenerational cycle”, or the “fathers and sons cycle”.

Timing and intensity of internal war in medieval and early modern England, from Turchin and Nefedov 2009.

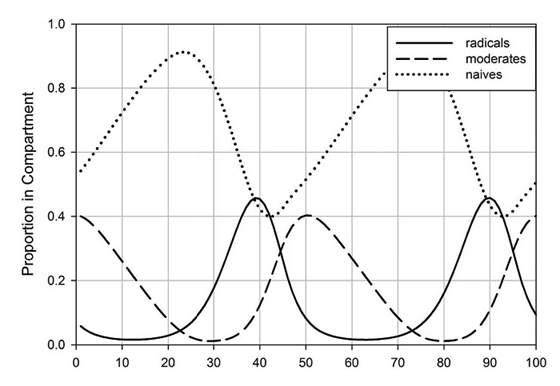

The derivation of this cycle, explained on pages 45 – 58 of Ages of Discord, is one of the highlights of the book. Turchin draws on the kind of models epidemiologists use to track pandemics, thinking of violence as an infection and radicals as plague-bearers. You start with an unexposed vulnerable population. Some radical – patient zero – starts calling for violence. His ideas spread to a certain percent of people he interacts with, gradually “infecting” more and more people with the “radical ideas” virus. But after enough time radicalized, some people “recover” – they become exhausted with or disillusioned by conflict, and become pro-cooperation “active moderates” who are impossible to reinfect (in the epidemic model, they are “inoculated”, but they also have an ability without a clear epidemiological equivalent to dampen radicalism in people around them). As the rates of radicals, active moderates, and unexposed dynamically vary, you get a cyclic pattern. First everyone is unexposed. Then radicalism gradually spreads. Then active moderation gradually spreads, until it reaches a tipping point where it triumphs and radicalism is suppressed to a few isolated reservoirs in the population. Then the active moderates gradually die off, new unexposed people are gradually born, and the cycle starts again. Fiddling with all these various parameters, Turchin is able to get the system to produce 40-60 year waves of instability.

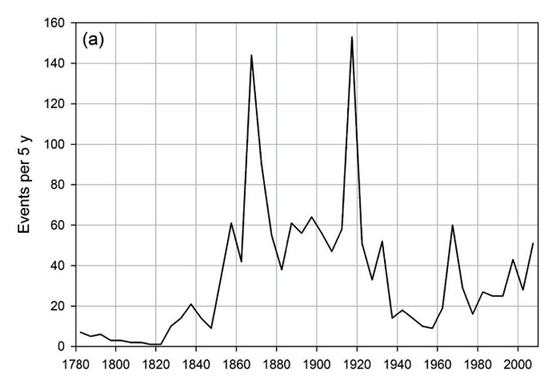

To check this empirically, Turchin tries to measure the number of “instability events” in the US over various periods. He very correctly tries to use lists made by others (since they are harder to bias), but when people haven’t catalogued exactly the kind of instability he’s interested in over the entire 1780 – present period, he sometimes adds his own interpretation. He ends up summing riots, lynchings, terrorism (including assassinations), and mass shootings – you can see his definition for each of these starting on page 114; the short version is that all the definitions seem reasonable but inevitably include a lot of degrees of freedom.

When he adds all this together, here’s what happens:

Political instability / violent events show three peaks, around 1870, 1920, and 1970.

The 1870 peak includes the Civil War, various Civil War associated violence (eg draft riots), and the violence around Reconstruction (including the rise of the Ku Klux Klan and related violence to try to control newly emancipated blacks).

The 1920 peak includes the height of the early US labor movement. Turchin discusses the Mine War, an “undeclared war” from 1920-1921 between bosses and laborers in Appalachian coal country:

Although it started as a labor dispute, it eventually turned into the largest armed insurrection in US history, other than the Civil War. Between 10,000 and 15,000 miners armed with rifles fought thouasnds of strike-breakers and sheriff’s deputies, called the Logan Defenders. The insurrection was ended by the US Army. While such violent incidents were exceptional, they took place against a background of a general “class war” that had been intensifying since the violent teens. “In 1919 nearly four million workers (21% of the workforce) took disruptive action in the face of employer reluctance to recognize or bargain with unions” (Domhoff and Webber, 2011:74).

Along with labor violence, 1920 was also a peak in racial violence:

Race-motivated riots also peaked around 1920. The two most serious such outbreaks were the Red Summer of 1919 (McWhirter 2011) and the Tulsa (Oklahoma) Race Riot. The Red Summer involved riots in more than 20 cities across the United States and resulted in something like 1,000 fatalities. The Tulsa riot in 1921, which caused about 300 deaths, took on an aspect of civil war, in which thousands of whites and blacks, armed with firearms, fought in the streets, and most of the Greenwood District, a prosperous black neighborhood, was destroyed.

And terrorism:

The bombing campaign by Italian anarchists (“Galleanists”) culminated in the 1920 explosion on Wall Street, which caused 38 fatalities.

The same problems: labor unrest, racial violence, terrorism – repeated during the 1970s spike. Instead of quoting Turchin on this, I want to quote this Status 451 review of Days of Rage, because it blew my mind:

“People have completely forgotten that in 1972 we had over nineteen hundred domestic bombings in the United States.” — Max Noel, FBI (ret.)

Recently, I had my head torn off by a book: Bryan Burrough’s Days of Rage, about the 1970s underground. It’s the most important book I’ve read in a year. So I did a series of running tweetstorms about it, and Clark asked me if he could collect them for posterity. I’ve edited them slightly for editorial coherence.

Days of Rage is important, because this stuff is forgotten and it shouldn’t be. The 1970s underground wasn’t small. It was hundreds of people becoming urban guerrillas. Bombing buildings: the Pentagon, the Capitol, courthouses, restaurants, corporations. Robbing banks. Assassinating police. People really thought that revolution was imminent, and thought violence would bring it about.

One thing that Burrough returns to in Days of Rage, over and over and over, is how forgotten so much of this stuff is. Puerto Rican separatists bombed NYC like 300 times, killed people, shot up Congress, tried to kill POTUS (Truman). Nobody remembers it.

The passage speaks to me because – yeah, nobody remembers it. This is also how I feel about the 1920 spike in violence. I’d heard about the Tulsa race riot, but the Mine War and the bombing of Wall Street and all the other stuff was new to me. This matters because my intuitions before reading this book would not have been that there were three giant spikes in violence/instability in US history located fifty years apart. I think the lesson I learn is not to trust my intuitions, and to be a little more sympathetic to Turchin’s data.

One more thing: the 1770 spike was obviously the American Revolution and all of the riots and communal violence associated with it (eg against Tories). Where was the 1820 spike? Turchin admits it didn’t happen. He says that because 1820 was the absolute best part of the 150 year grand cycle, everybody was so happy and well-off and patriotic that the scheduled instability peak just fizzled out. Although Turchin doesn’t mention it, you could make a similar argument that the 1870 spike was especially bad (see: the entire frickin’ Civil War) because it hit close to (though not exactly at) the worst part of the grand cycle. 1920 hit around the middle, and 1970 during a somewhat-good period, so they fell in between the nonissue of 1820 and the disaster of 1870.

III.

I haven’t forgotten the original question – what drives these 150 year cycles of rise and decline – but I want to stay with the data just a little longer. Again, these data are really interesting. Either some sort of really interesting theory has to be behind them – or they’re just low-quality data cherry-picked to make a point. Which are they? Here are a couple of spot-checks to see if the data are any good.

First spot check: can I confirm Turchin’s data from independent sources?

– Here is a graph of average US height over time which seems broadly similar to Turchin’s.

– Here is a different measure of US income inequality over time, which again seems broadly similar to Turchin’s. Piketty also presents very similar data, though his story places more emphasis on the World Wars and less on the labor movement.

– The Columbia Law Review measures political polarization over time and gets mostly the same numbers as Turchin.

I’m going to consider this successfully checked; Turchin’s data all seem basically accurate.

Second spot check: do other indicators Turchin didn’t include confirm the pattern he detects, or did he just cherry-pick the data series that worked? Spoiler: I wasn’t able to do this one. It was too hard to think of measures that should reflect general well-being and that we have 200+ years of unconfounded data for. But here are my various failures:

– The annual improvement in mortality rate does not seem to follow the cyclic pattern. But isn’t this more driven by a few random factors like smoking rates and the logic of technological advance?

– Treasury bonds maybe kind of follow the pattern until 1980, after which they go crazy.

– Divorce rates look kind of iffy, but isn’t that just a bunch of random factors?

– Homicide rates, with the general downward trend removed, sort of follow the pattern, except for the recent decline?

– USD/GBP exchange rates don’t show the pattern at all, but that could be because of things going on in Britain?

The thing is – really I have no reason to expect divorce rates, homicide rates, exchange rates etc to track national flourishing. For one thing, they may just be totally unrelated. For another, even if they were tenuously related, there are all sorts of other random factors that can affect them. The problem is, I would have said this was true for height, age at first marriage, and income inequality too, before Turchin gave me convincing-sounding stories for why it wasn’t. I think my lesson is that I have no idea which indicators should vs. shouldn’t follow a secular-cyclic pattern and so I can’t do this spot check against cherry-picking the way I hoped.

Third spot check: common sense. Here are some things that stood out to me:

– The Civil War is at a low-ish part of the cycle, but by no means the lowest.

– The Great Depression happened at a medium part of the cycle, when things should have been quickly getting better.

– Even though there was a lot of new optimism with Reagan, continuing through the Clinton years, the cycle does not reflect this at all.

Maybe we can rescue the first and third problem by combining the 150 year cycle with the shorter 50 year cycle. The Civil War was determined by the 50-year cycle having its occasional burst of violence at the same time the 150-year cycle was at a low-ish point. People have good memories of Reagan because the chaos of the 1970 violence burst had ended.

As for the second, Turchin is aware of the problem. He writes:

There is a widely held belief among economists and other social scientists that the 1930s were the “defining moment” in the development of the American politico-economic system (Bordo et al 1998). When we look at the major structural-demographic variables, however, the decade of the 1930s does not seem to be a turning point. Structural-demographic trends that were established during the Progressive Era continues through the 1930s, although some of them accelerated.

Most notably, all the well-being variables that went through trend reversals before the Great Depression – between 1900 and 1920. From roughly 1910 and to 1960 they all increased roughly monotonically, with only one or two minor fluctuations around the upward trend. The dynamics of real wages also do not exhibit a breaking point in the 1930s, although there was a minor acceleration after 1932.

By comparison, he plays up the conveniently-timed (and hitherto unknown to me) depression of the mid-1890s. Quoting Turchin quoting McCormick:

No depression had ever been as deep and tragic as the one that lasted from 1893 to 1897. Millions suffered unemployment, especially during the winters of 1893-4 and 1894-5, and thousands of ‘tramps’ wandered the countryside in search of food […]

Despite real hardship resulting form massive unemployment, well-being indicators suggest that the human cost of the Great Depression of the 1930s did not match that of the “First Great Depression” of the 1890s (see also Grant 1983:3-11 for a general discussion of the severity of the 1890s depression. Furthermore, while the 1930s are remembered as a period of violent labor unrest, the intensity of class struggle was actually lower than during the 1890s depression. According to the US Political Violence Database (Turchin et al. 2012) there were 32 lethal labor disputes during the 1890s that collectively caused 140 deaths, compared with 20 such disputes in the 1930s with the total of 55 deaths. Furthermore, the last lethal strike in US labor history was in 1937…in other words, the 1930s was actually the last uptick of violent class struggle in the US, superimposed on an overall declining trend.

The 1930s Depression is probably remembered (or rather misremembered) as the worst economic slump in US history, simply because it was the last of the great depressions of the post-Civil War era.

Fourth spot check: Did I randomly notice any egregious errors while reading the book?

On page 70, Turchin discusses “the great cholera epidemic of 1849, which carried away up to 10% of the American population”. This seemed unbelievably high to me. I checked the source he cited, Kohl’s “Encyclopedia Of Plague And Pestilence”, which did give that number. But every other source I checked agreed that the epidemic “only” killed between 0.3% – 1% of the US population (it did hit 10% in a few especially unlucky cities like St. Louis). I cannot fault Turchin’s scholarship in the sense of correctly repeating something written in an encyclopedia, but unless I’m missing something I do fault his common sense.

Also, on page 234, Turchin interprets the percent of medical school graduates who get a residency as “the gap between the demand and supply of MD positions”, which he ties into a wider argument about elite overproduction. But I think this shows a limited understanding of how the medical system works. There is currently a severe undersupply of doctors – try getting an appointment with a specialist who takes insurance in a reasonable amount of time if you don’t believe me. Residencies aren’t limited by organic demand. They’re limited because the government places so many restrictions on them that hospitals don’t sponsor them without government funding, and the government is too stingy to fund more of them. None of this has anything to do with elite overproduction.

These are just two small errors in a long book. But they’re two errors in medicine, the field I know something about. This makes me worry about Gell-Mann Amnesia: if I notice errors in my own field, how many errors must there be in other fields that I just didn’t catch?

My overall conclusion from the spot-checks is that the data as presented are basically accurate, but that everything else is so dependent on litigating which things are vs. aren’t in accordance with the theory that I basically give up.

IV.

Okay. We’ve gone through the data supporting the grand cycle. We’ve gone through the data and theory for the 40-60 year instability cycle. We’ve gone through the reasons to trust vs. distrust the data. Time to go back to the question we started with: why should the grand cycle, originally derived from the Malthusian principles that govern pre-industrial societies, hold in the modern US? Food and land are no longer limiting resources; famines, disease, and wars no longer substantially decrease population. Almost every factor that drives the original secular cycle is missing; why even consider the possibility that it might still apply?

I’ve put this off because, even though this is the obvious question Ages of Discord faces from page one, I found it hard to get a single clear answer.

Sometimes, Turchin talks about the supply vs. demand of labor. In times when the supply of labor outpaces demand, wages go down, inequality increases, elites fragment, and the country gets worse, mimicking the “land is at carrying capacity” stage of the Malthusian cycle. In times when demand for labor exceeds supply, wages go up, inequality decreases, elites unite, and the country gets better. The government is controlled by plutocrats, who always want wages to be low. So they implement policies that increase the supply of labor, especially loose immigration laws. But their actions cause inequality to increase and everyone to become miserable. Ordinary people organize resistance: populist movements, socialist cadres, labor unions. The system teeters on the edge of violence, revolution, and total disintegration. Since the elites don’t want those things, they take a step back, realize they’re killing the goose that lays the golden egg, and decide to loosen their grip on the neck of the populace. The government becomes moderately pro-labor and progressive for a while, and tightens immigration laws. The oversupply of labor decreases, wages go up, inequality goes down, and everyone is happy. After everyone has been happy for a while, the populists/socialists/unions lose relevance and drift apart. A new generation of elites who have never felt threatened come to power, and they think to themselves “What if we used our control of the government to squeeze labor harder?” Thus the cycle begins again.

But at other times, Turchin talks more about “elite overproduction”. When there are relatively few elites, they can cooperate for their common good. Bipartisanship is high, everyone is unified behind a system perceived as wise and benevolent, and we get a historical period like the 1820s US golden age that historians call The Era Of Good Feelings. But as the number of elites outstrips the number of high-status positions, competition heats up. Elites realize they can get a leg up in an increasingly difficult rat race by backstabbing against each other and the country. Government and culture enter a defect-defect era of hyperpartisanship, where everyone burns the commons of productive norms and institutions in order to get ahead. Eventually…some process reverses this or something?…and then the cycle starts again.

At still other times, Turchin seems to retreat to a sort of mathematical formalism. He constructs an extremely hokey-looking dynamic feedback model, based on ideas like “assume that the level of discontent among ordinary people equals the urbanization rate x the age structure x the inverse of their wages relative to the elite” or “let us define the fiscal distress index as debt ÷ GDP x the level of distrust in state institutions”. Then he puts these all together into a model that calculates how the the level of discontent affects and is affected by the level of state fiscal distress and a few dozen other variables. On the one hand, this is really cool, and watching it in action gives you the same kind of feeling Seldon must have had inventing psychohistory. On the other, it seems really made-up. Turchin admits that dynamic feedback systems are infamous for going completely haywire if they are even a tiny bit skew to reality, but assures us that he understands the cutting-edge of the field and how to make them not to do that. I don’t know enough to judge whether he’s right or wrong, but my priors are on “extremely, almost unfathomably wrong”. Still, at times he reminds us that the shifts of dynamic feedback systems can be attributed only to the system in its entirety, and that trying to tell stories about or point to specific factors involved in any particular shift is an approximation at best.

All of these three stories run into problems almost immediately.

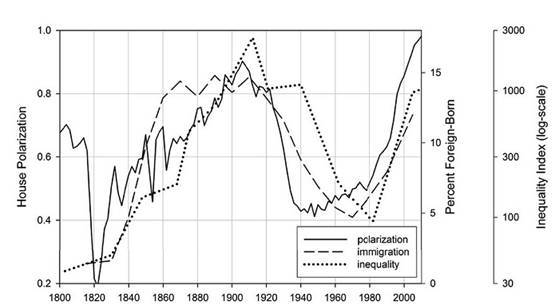

First, the supply of labor story focuses pretty heavily on immigration. Turchin puts a lot of work into showing that immigration follows the secular cycle patterns; it is highest at the worst part of the cycle, and lowest at the best parts:

In this model, immigration is a tool of the plutocracy. High supply of labor (relative to demand) drives down wages, increases inequality, and lowers workers’ bargaining power. If the labor supply is poorly organized, comes from places that don’t understand the concept of “union”, don’t know their rights, and have racial and linguistic barriers preventing them from cooperating with the rest of the working class, well, even better. Thus, periods when the plutocracy is successfully squeezing the working class are marked by high immigration. Periods when the plutocracy fears the working class and feels compelled to be nice to them are marked by low immigration.

This position makes some sense and is loosely supported by the long-term data above. But isn’t this one of the most-studied topics in the history of economics? Hasn’t it been proven almost beyond doubt that immigrants don’t steal jobs from American workers, and that since they consume products themselves (and thus increase the demand for labor) they don’t affect the supply/demand balance that sets wages?

It appears I might just be totally miscalibrated on this topic. I checked the IGM Economic Experts Panel. Although most of the expert economists surveyed believed immigration was a net good for America, they did say (50% agree to only 9% disagree) that “unless they were compensated by others, many low-skilled American workers would be substantially worse off if a larger number of low-skilled foreign workers were legally allowed to enter the US each year”. I’m having trouble seeing the difference between this statement (which economists seem very convinced is true) and “you should worry about immigrants stealing your job” (which everyone seems very convinced is false). It might be something like – immigration generally makes “the economy better”, but there’s no guarantee that these gains are evently distributed, and so it can be bad for low-skilled workers in particular? I don’t know, this would still represent a pretty big update, but given that I was told all top economists think one thing, and now I have a survey of all top economists saying the other, I guess big updates are unavoidable. Interested in hearing from someone who knows more about this.

Even if it’s true that immigration can hurt low-skilled workers, Turchin’s position – which is that increased immigration is responsible for a very large portion of post-1973 wage stagnation and the recent trend toward rising inequality – sounds shocking to current political sensibilities. But all Turchin has to say is:

An imbalance between labor supply and demand clearly played an important role in driving real wages down after 1978. As Harvard economist George J. Borjas recently wrote, “The best empirical research that tries to examine what has actually happened in the US labor market aligns well with economic theory: An increase in the number of workers leads to lower wages.”

My impression was that Borjas was an increasingly isolated contrarian voice, so once again, I just don’t know what to do here.

Second, the plutocratic oppression story relies pretty heavily on the idea that inequality is a unique bad. This fits the zeitgeist pretty well, but it’s a little confusing. Why should commoners care about their wages relative to elites, as opposed to their absolute wages? Although median-wage-relative-to-GDP has gone down over the past few decades, absolute median wage has gone up – just a little, slowly enough that it’s rightly considered a problem – but it has gone up. Since modern wages are well above 1950s wages, in what sense should modern people feel like they are economically bad off in a way 1950s people didn’t? This isn’t a problem for Turchin’s theory so much as a general mystery, but it’s a general mystery I care about a lot. One answer is that the cost disease is fueled by a Baumol effect pegged to per capital income (see part 3 here), and this is a way that increasing elite wealth can absolutely (not relatively) immiserate the lower classes.

Likewise, what about The Spirit Level Delusion and other resources showing that, across countries, inequality is not particularly correlated with social bads? Does this challenge Turchin’s America-centric findings that everything gets worse along with inequality levels?

Third, the plutocratic oppression story meshes poorly with the elite overproduction story. In elite overproduction, united elites are a sign of good times to come; divided elites means dysfunctional government and potential violence. But as Pseudoerasmus points out, united elites are often united against the commoners, and we should expect inequality to be highest at times when the elites are able to work together to fight for a larger share of the pie. But I think this is the opposite of Turchin’s story, where elites unite only to make concessions, and elite unity equals popular prosperity.

Fourth, everything about the elite overproduction story confuses me. Who are “elites”? This category made sense in Secular Cycles, which discussed agrarian societies with a distinct titled nobility. But Turchin wants to define US elites in terms of wealth, which follows a continuous distribution. And if you’re defining elites by wealth, it doesn’t make sense to talk about “not enough high-status positions for all elites”; if you’re elite (by virtue of your great wealth), by definition you already have what you need to maintain your elite status. Turchin seems aware of this issue, and sometimes talks about “elite aspirants” – some kind of upper class who expect to be wealthy, but might or might not get that aspiration fulfilled. But then understanding elite overproduction hinges on what makes one non-rich-person person a commoner vs. another non-rich-person an “elite aspirant”, and I don’t remember any clear discussion of this in the book.

Fifth, what drives elite overproduction? Why do elites (as a percent of the population) increase during some periods and decrease during others? Why should this be a cycle rather than a random walk?

My guess is that Ages of Discord contains answers to some of these questions and I just missed them. But I missed them after reading the book pretty closely to try to find them, and I didn’t feel like there were any similar holes in Secular Cycles. As a result, although the book had some fascinating data, I felt like it lacked a clear and lucid thesis about exactly what was going on.

V.

Accepting the data as basically right, do we have to try to wring some sense out of the theory?

The data cover a cycle and a half. That means we only sort of barely get to see the cycle “repeat”. The conclusion that it is a cycle and not some disconnected trends is based only on the single coincidence that it was 70ish years from the first turning point (1820) to the second (1890), and also 70ish years from the second to the third (1960).

A parsimonious explanation would be “for some reason things were going unusually well around 1820, unusually badly around 1890, and unusually well around 1960 again.” This is actually really interesting – I didn’t know it was true before reading this book, and it changes my conception of American history a lot. But it’s a lot less interesting than the discovery of a secular cycle.

I think the parsimonious explanation is close to what Thomas Piketty argued in his Capital In The Twenty-First Century. Inequality was rising until the World Wars, because that’s what inequality naturally does given reasonable assumptions about growth rates. Then the Depression and World Wars wiped out a lot of existing money and power structures and made things equal again for a little while. Then inequality started rising again, because that’s what inequality naturally does given reasonable assumptions about growth rates. Add in a pinch of The Spirit Level – inequality is a mysterious magic poison that somehow makes everything else worse – and there’s not much left to be explained.

(some exceptions: why was inequality decreasing until 1820? Does inequality really drive political polarization? When immigration corresponds to periods of high inequality, is the immigration causing the inequality? And what about the 50 year cycle of violence? That’s another coincidence we didn’t include in the coincidence list!)

So what can we get from Ages of Discord that we can’t get from Piketty?

First, the concept of “elite overproduction” is one that worms its way into your head. It’s the sort of thing that was constantly in the background of Increasingly Competitive College Admissions: Much More Than You Wanted To Know. It’s the sort of thing you think about when a million fresh-faced college graduates want to become Journalists and Shape The Conversation and Fight For Justice and realistically just end up getting ground up and spit out by clickbait websites. Ages of Discord didn’t do a great job breaking down its exact dynamics, but I’m grateful for its work bringing it from a sort of shared unconscious assumption into the light where we can talk about it.

Second, the idea of a deep link between various indicators of goodness and badness – like wages and partisan polarization – is an important one. It forces me to reevaluate things I had considered settled, like that immigration doesn’t worsen inequality, or that inequality is not a magical curse that poisons everything.

Third, historians have to choose what events to focus on. Normal historians usually focus on the same normal events. Unusual historians sometimes focus on neglected events that support their unusual theses, so reading someone like Turchin is a good way to learn parts of history you’d never encounter otherwise. Some of these I was able to mention above – like the Mine War of 1920 or the cholera epidemic of 1849; I might make another post for some of the others.

Fourth, it tries to link events most people would consider separate – wage stagnation since 1973, the Great Stagnation in technology, the decline of Peter Thiel’s “definite optimism”, the rise of partisan polarization. I’m not sure exactly how it links them or what it has to stay about the link, but link them it does.

But the most important thing about this book is that Turchin claims to be able to predict the future. The book (written just before Trump was elected in 2016) ends by saying that “we live in times of intensifying structural-demographic pressures for instability”. The next bigenerational burst of violence is scheduled for about 2020 (realistically +/- a few years). It’s at a low point in the grand cycle, so it should be a doozy.

What about beyond that? It’s unclear exactly where he thinks we are right now in the grand cycle. If the current cycle lasts exactly as long as the last one, we would expect it to bottom out in 2030, but Turchin never claims every cycle is exactly as long. A few of his graphs suggest a hint of curvature, suggesting we might currently be in the worst of it. The socialists seem to have gotten their act together and become an important political force, which the theory predicts is a necessary precursor to change.

I think we can count the book as having made correct predictions if violence spikes in the very near future (are the current number of mass shootings enough to satisfy this requirement? I would have to see it graphed using the same measurements as past spikes), and if sometime in the next decade or so things start looking like there’s a ray of light at the end of the tunnel.

I am pretty interested in finding other ways to test Turchin’s theories. I’m going to ask some of my math genius friends to see if the dynamic feedback models check out; if anyone wants to help, let me know how I can help you (if money is an issue, I can send you a copy of the book, and I will definitely publish anything you find on this blog). If anyone has any other ideas for to indicators that should be correlated with the secular cycle, and ideas about how to find them, I’m intereted in that too. And if anyone thinks they can explain the elite overproduction issue, please enlighten me.

I ended my review of Secular Cycles by saying:

One thing that strikes me about [Turchin]’s cycles is the ideological component. They describe how, during a growth phase, everyone is optimistic and patriotic, secure in the knowledge that there is enough for everybody. During the stagflation phase, inequality increases, but concern about inequality increases even more, zero-sum thinking predominates, and social trust craters (both because people are actually defecting, and because it’s in lots of people’s interest to play up the degree to which people are defecting). By the crisis phase, partisanship is much stronger than patriotism and radicals are talking openly about how violence is ethically obligatory.

And then, eventually, things get better. There is a new Augustan Age of virtue and the reestablishment of all good things. This is a really interesting claim. Western philosophy tends to think in terms of trends, not cycles. We see everything going on around us, and we think this is some endless trend towards more partisanship, more inequality, more hatred, and more state dysfunction. But Secular Cycles offers a narrative where endless trends can end, and things can get better after all.

This is still the hope, I guess. I don’t have a lot of faith in human effort to restore niceness, community, and civilization. All I can do is pray the Vast Formless Things accomplish it for us without asking us first.

America underwent a nervous breakdown around 1919, and then calmed down rapidly under President Harding, who ran on “normalcy.” The country remained remarkably orderly during the stresses of the Depression, kind of like how in 2009 not just crime but pedestrian traffic fatalities were low.

Here’s an excerpt that Bryan Burrough wrote for “Time” summarizing his book on 1970s bombings:

“In a single eighteen-month period during 1971 and 1972 the FBI counted an amazing 2,500 bombings on American soil, almost five a day. Because they were typically detonated late at night, few caused serious injury, leading to a kind of grudging public acceptance. The deadliest underground attack of the decade, in fact, killed all of four people, in the January 1975 bombing of a Wall Street restaurant. News accounts rarely carried any expression or indication of public outrage. …

“And the violence actually grew more deadly as the number of underground groups dwindled and grew more desperate; the deadliest year for underground violence was 1981, when eleven people were killed in bombings and bank robberies gone bad.”

So, a lot of these bombs were set off by people who love the sound of broken glass, but weren’t really out to kill anyone.

https://time.com/4501670/bombings-of-america-burrough/

Instead of bombs, the problem that got a ton of publicity at the time was skyjacking of airliners. There were 40 hijackings in the US in 1972 alone. Some were terrorists, but many skyjackers were just low-grade losers out for some ransom and an adventure.

https://www.wired.com/2013/06/skyjacking-gallery/

I can recall my trying to invent a Skyjacking board game during the summer of 1972 when I was 13.

Airlines started running passengers thru metal detectors in 1973 and the crisis receded pretty quickly, except for serious terrorist organizations.

If I read that correctly you seem to be in favour of faster AGI development as we are doomed otherwise? Guess Nick Land successfully converted you to his side in the end. 😉

P.S: I dont blame you as I am coming to similar conclusions myself.

As might be said on Reddit – user name checks out

To highjack Clarke: either we submit to governance by AI, or we do not. Both are equally terrifying.

Well the first signs were there in our host 2016 pre-election post:

https://slatestarcodex.com/2016/09/28/ssc-endorses-clinton-johnson-or-stein/

I guess the part of the “keep the world functional enough” plan is not looking good lately so maybe we should try our luck with machine Gods and hope the LW/MIRI fears turn out to be unfounded. I mean we are screwed anyway so why not roll the dice.

And to be fair being turned into paperclip is far more interesting death scenario than one that will happen with increasing societal dysfunction. (being blown up by Russian/Chinese ICBM’s in WW3, being shot during new American civil war as a evil reactionary, getting killed in climate-change caused weather event…etc).

The thing is, societal dysfunction or not, you are doomed to die anyway — by old age if not anything else. Trying your luck with the machine Gods might change that, for better or worse.

@HomarusSimpson

Either we submit to governance and replacement by AI or there is some hard limit coded into the universe that prevents non-meat substrate intelligences from matching (let alone exceeding) human intelligence, in which case we would try to make giant biological brains specially designed to desire servitude instead, but then if there’s a hard coded rule that prevents even this, we seriously have to start giving more credibility to the possibility that there is/are a creator/creators and they don’t want any other general intelligences equivalent or greater than humans to exist in the universe. Yeah, both of these sound generally unnerving, but I would certainly rather the former scenario than the latter.

Providing reality is governed by the laws of physics in a consistent way, and there aren’t flippant exceptions coded in, the overwhelmingly likely scenario is that general superintelligence is possible, and then the only question is whether we suffer global ecological and civilizational collapse before the machines govern and replace us. The small upside is the sub-scenario of the latter where we get to govern the machines and make them do useful things for us for a few decades before they (or “it” if you believe in the singleton theory) take control of the government and start ruling over us. The small upside of that scenario in turn is the sub-sub-scenario where machines went through a humanized ethical path due to general AI being derived from brain simulation rather than evolutionary algorithms, and then they rule over us in a way that has some respect for human rights, rather than seeing us as a source of materials to be used for something else.

A comfy retirement while we are gradually obsolesced doesn’t sound so bad but it brings a sense of existential unease to many people. About the only scenario that sounds remotely progressive to the human ego is the one where the machines upgrade us to be like them in a way that maintains continuity of consciousness.

There is an often overlooked possibility to elevate ourselves to the superintelligent tier, either by advanced biotech or, more plausibly, by augmenting human brain with AI modules. In that case the entities doing the governance could be, at least to some extent, considered human.

No, “Vast Formless Things” is here meant to mean social trends.

I think Vast Formless Things refers to mysterious large scale socio-historical trends more than AGIs.

Re economists and immigration: It’s almost as if economists respond to incentives, and most of the incentives in recent decades (e.g., Koch money, Democratic Party politics, etc.) have been on the side of promoting immigration as Good For The Economy.

Yes I think it’s blindingly obvious why economists say immigration is good. It’s impossible to get a man to understand something when his salary depends on his not understanding it.

Is there something stopping Trump et al buying some economists?

It’s not “buying economists” directly, more like “compromising institutions that train and pay economists”. This is a multidecadal process, and anti-immigration political forces haven’t yet had the time (or the coordination) to do it.

The media would tell him to fire those economists, and like the lapdog he is he’d do it.

Our betters sure love Stephen Miller and Peter Navarro, don’t they?

More generous interpretations:

1.) The economists being surveyed haven’t actually studied what’s being asked thoroughly themselves.

2. ) Finding good empircal evidence for immigration harming wages would be difficult since reality can’t easily distinguish between shifts in the labor supply curve and an increase in labor supplied. We would expect immigration pressures to be strongest when labor demand is strongest.

Bjorgas comes close to instituting the right kinds of statistical controls one would need to prove it definitively but ends up being left with very thin data as a result.

3.) “Good for the Economy” and “Raises the wages of every working class person without exception” are not synonyms. If I invented a machine that could instantly and reliably turn wheat, beef, lettuce, milk, etc. into a completed cheeseburger, that would be amazing for the economy (Food is cheaper and more plentiful!) but terrible for the wages of fast-food employees. I’d expect an economist to vocally support this innovation even if they acknowledged that some McDonald’s employees would lose their jobs.

The thing is, when people say “the economy” they mean (at least) two different things, which aren’t wholly equivalent. One is mostly about production of goods and services, the other mostly about distribution of demand for labor. (When people talk about GDP it’s mostly about the first; when they talk about unemployment rate, it’s mostly about the second.)

The hypothetical Auto-Cheeseburger-Machine would create more, cheaper goods and services (boosting the economy in the first sense), but narrow the demand for labor (hurting the economy in the second sense). It’s often assumed that any narrowing of labor demand will automatically be compensated by new jobs created in the new goods-and-services environment, leaving the demand-side as a wash and thus translating into pure gain from the cheaper goods. (Often, this has even been true.) But this compensation doesn’t act instantly or without friction, and it’s not a given that it will always act at all; thus, the economists’ assumption that hurting the demand-side to boost the goods-side is always a win is something that should at least be made explicit and interrogated, not simply assumed without question in every circumstance.

(and of course the reason why economists are reluctant to do this can be laid at least in part at the feed of industrialists’ interests; they always benefit from cheaper goods, and rarely suffer from decreased demand, and by coincidence they are also broadly the class that funds economics departments.)

Ask not what The Economy can do for you; ask what you can do for The Economy.

All true. But “Good for the economy” and “Good policy” are also not good synonyms.

If you want the elites to have cheap nannies and gardeners at the expense of the working class, dont be so shocked when the working class elects a populist who at least pretends to not despise them.

Exactly.

On the one hand you have the law of supply and demand predicting immigration reduces wages. On the other hand you have empirical data showing depressed wage growth during periods of high immigration. But on the other other hand you have experts telling me I’m a racist for observing that the data fits the theory.

Parsimonious explanation: the experts are corrupt.

Yes, it’s the same hands-on-ears la la la la la la response sociologists give you when you try to bring up biology and heritability of IQ/life outcomes (in context to how refractory they are to environmental intervention in Western societies). It’s arguably for a good cause (in addition to being a response to incentives) but it’s intellectually dishonest enough that eventually some of us will notice we are confused. Low skill immigration is good for the immigrants themselves and as a byproduct, for elites, and is likely a net utilitarian gain. So it’s very convenient to ignore negative impacts on low/middle-skill natives. It’s also convenient to ignore the implications it has for aspects of society upstream of econ (i.e. the Thielian libertarian-authoritarian pipeline) because those implications are a vague and hard to prove and also crimethink.

Anything conclusion which is even vaguely threatening to the elites is considered out-of-bounds. It’s true of the IQ question, the immigration question, and other topics which are “settled”.

This reminds me of the American Physical Society claiming the evidence for global warming was incontrovertible while also allowing discussions on whether the mass of the proton changed over time and how multiverses behave.

Anytime the experts agree on something and dont allow dissent, you should very much expect the opposite to be true.

If we stipulate for the sake of argument that global warming does not exist…

In such a world, elites don’t profit very much from continued belief in global warming, compared to a counterfactual world where no one believed in global warming.

It’s possible to construct scenarios where everyone has a competing incentive structure to enforce belief in global warming on each other, even though no one actually has good reason to believe it themselves.

…But then, it’s also possible to construct scenarios where this entire exercise in hypothesizing a conspiracy to enforce beliefs about climate change is a false alarm. Something on par with noticing that hypothetically there could be a conspiracy to convince everyone that the American Civil War took place. There could be, but that’s not the way to bet, when you can literally go to old Civil War battlefields with a metal detector and dig up bullets, or exhume the war graves and find skeletons with gunshot wounds.

Similarly, we live in a world where comparing photos of glaciers from 1919 to 2019 is often striking. We live in a world where the Northwest Passage is open to shipping when some of the greatest explorers of the nineteenth century died icebound in vain trying to find it. We live in a world where we know for a fact that carbon dioxide levels in the atmosphere have risen by something like 30-50% from pre-modern levels, where basic physics says that carbon dioxide is a greenhouse gas, and where interestingly the aforesaid things are true.

All of which suggests that the theory “elites enforce belief in global warming because it threatens the elite” needs to be amended to “elites enforce belief in global warming because evidence indicates that continuing to ignore global warming will threaten future generations of the elite and everyone else too.”

The fact that the man shouting that the roof is about to fall down happens to own the roof doesn’t mean it’s a good idea to hang around and wait to see what happens- let alone to block the exit doors.

On the contrary, even in a world where global warming does not exist, a subset of the elite benefits from enforcing belief in it, because it creates a crisis, and crises are a prime opportunity to take power. (“never let a crisis go to waste”, and all.) This is hardly an unusual political maneuver, and it should be easy to see that it’s possible for someone to benefit from it.

It’s quite easy to imagine how elites would benefit from taxing the byproducts of combustion. The evidence for global warming should be examined at face value, and not based on how the elites benefit from the crisis, but as a separate endeavor, it is quite simple to see how they do benefit from it. As Dedicating Ruckus notes above, it creates a crisis, which is an opportunity to tax and control the non-elites.

As to actual reasons to doubt global warming alarm, simply the fact that there is no evidence that CO2 was a driver of global temperatures in the past is sufficient. The failed predictions of the last 30+ years are also quite convincing.

> even in a world where global warming does not exist, a subset of the elite benefits from enforcing belief in it, because it creates a crisis, and crises are a prime opportunity to take power.

But this doesn’t explain why *all* elites would seem to be going in on this. Surely if some elites were trying to manufacture a crisis, other elites would be able to profit from showing the hoax, right?

Have you heard of the Mariel Boat Lift? (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mariel_boatlift)

The labour force of Miami was shock-increased by 7% in around 5 months, and there was no detectable change to macro properties compared to the rest of the country.

BUT

For prime working age male high school dropouts, there WAS a decrease in wages.

So, since a lot of immigration is VERY unskilled (not even high school graduated), it is complementary to the vast majority of the US labour force (since the on-time high school graduation rate is 84% and the total high school graduation rate is presumably several points higher).

This has complicated implications for general welfare.

As I pointed out way back in 2006, economist David Card’s study of wages in Miami and four control cities following the Mariel Boatlift of Cubans to Miami in 1980 had an obvious enormous methodological problem: Miami wasn’t ceteris paribus compared to the other four cities because not only did Miami experience the Mariel Boatlift in 1980, but from 1980 to 1984 Miami also experienced the most notorious Cocaine Boom in economic history, as depicted in “Scarface,” “Miami Vice,” and “Narcos.” Vast quantities of cocaine flowing expensively through Miami during the 1980-84 years studied by Card would naturally tend to raise wages.

Miami in the early 1980s is one of the more famous times/places in American pop culture history, yet economists never seem to remember anything distinctive about Miami in the early 1980s when discussing Card’s study.

The 1820s were an Era of Good Feelings in part because there was just an enormous amount of high quality land — the entire Mississippi-Missouri-Ohio watersheds for a small population to settle, with land being sold to small farmers cheaply by the federal government. The Jeffersonian-Jacksonian vision of yeoman farmers worked well (unless you were an Indian) for awhile.

Unfortunately, one form of farming — slave-worked cotton plantations — proved to be wildly profitable, which was destabilizing. It caused a big increase in inequality and a big increase in anti-egalitarian right wing political extremism in the South, with well-known consequences.

Eventually, the frontier filled in and there was a huge increase in industry, urbanization, and immigration, which was destabilizing for several decades.

Eventually, immigration was cut back, unions grew powerful, and taxes were high to pay for wars hot and cold, reducing inequality.

Homesteading the frontier was my thought to explain that period of low inequality as well.

A similar dynamic is occurring now: homesteading on cheap land is becoming increasingly attractive as the difficulty and cost of hooking up solar for the bare labour saving amenities (washer/dryer, refridgerator, internet, AC) craters.

Do you mean it’s theoretically becoming more attractive as a result of these factors, or are we actually seeing an uptick in homesteading? Because if it’s the latter, I’d be fascinated to learn more about this topic.

The Era of Good Feelings was also helped by the fact that they had the two main writers of the Constitution (Jefferson and Madison) as members of the same party running for the presidency, and the other party disbanded during the term of their hand-picked successor (Monroe). But the 1828 election, and all the extremely hard feelings caused by the “corrupt bargain” where Henry Clay instructed his electors to pick John Quincy Adams over the war hero Andrew Jackson, seem to me to suggest the idea that the “Era of Good Feelings” was really just a weird anomaly caused by one political party disbanding itself and briefly leaving a vacuum rather than an opposition. And the rise of the Democrats and Whigs seemed to lead directly to the chaos of the Civil War as their conflict kept studiously avoiding the topic of slavery.

There was slavery and a frontier in 1820, there was slavery and a frontier in 1860, how come the former period had unity and optimism and the latter period had division and pessimism?

One possible difference is the farmland quality available on the frontier. They were pushing up against the Rockies in some places, and in others were moving out into vast open plains without the forests / rivers that made simple homesteading without a train network to deliver finished goods viable. [You need wood to build a farmhouse, and the plains have fantastic soil but nearly no wood…note that a LOT of Ellis Island era immigrants from Scandinavia ended up in Minnesota / Iowa / further west because you could get a “farm in a kit” from Sears delivered by train {1880s}]

Another possible difference is the degree of native resistance. There was a notable period in time when the frontier in Texas actually contracted due to the rise of the Comanche (see, https://www.amazon.com/Empire-Summer-Moon-Comanches-Powerful/dp/1416591060). That period in the 1840s, 50s, 60s was a period when native plains tribes had mastered horseback raiding to an extent that made burning isolated white homesteads viable and non-governmental retribution nearly impossible.*

*Remember that for the period from ~1790 – 1810 the government was (at least to a minimal degree) trying to restrain settlers from moving into the Ohio River valley to attempt to honor its treaties with the native tribes there, but was failing and the settlers were making headway against the natives. My toy mental model for the difference between this case and the 1850s relates to the greater mobility of the plains indians making it difficult / impossible for the white settlers to retaliate to a homestead being burned by burning a native village, since the “village” in question was mobile and hundreds of miles away. It took the post-Civil War military’s logistical skill (and willingness to finance multi-hundred person expeditions for months at a time) to finally break the back of the Comanche.

West of the 100th parallel on the Great Plains, there wasn’t enough rain for farming, so mostly just ranching, which was fun, but couldn’t support a huge population. So the Frontier as a place for a big population started to peter out after the really good places to farm like Illinois and Iowa were settled.

Slavery wasn’t as wildly profitable in the 1820s as it was during the 1850s “Cotton Is King” bubble. Plus, in the 1820s, Southern slaveholders were mostly just filling in deep South states that everybody had already agreed would be slave states.

After the Mexican war, huge new territories were added, and whether they’d wind up slave or free was up in the air. Thus, Bloody Kansas in the 1850s.

Southern elites in the 1850s were increasingly megalomaniacal about the Overwhelming Goodness of Slave Societies (whereas in the 1820s they’d tended to be a little sheepish about their Peculiar Institutions). Many Northerners came to see the Slave Power as intent on soon imposing slavery on Caribbean countries to be conquered and imposing respect for Southern slaveholders’ property rights even on Northern states.

Southern elites came to see having control of the federal government as their right, and thus the results of the 1860 election were intolerable to them.

I wonder if he or anyone has tried to fit the pattern to other modern countries or regions? Obviously that would be open to a lot of data fitting, but if you can see the same trends play out in lots and lots of different situations, it would be a lot more convincing.

A simple explanation for a correlation between immigration and inequality, as that the immigrants themselves are poor.

I was assuming immigrants were too few to affect inequality all on their own (and it’s not clear that adding more poor people necessarily increases inequality since most people are poor anyway) but I agree this is one plausible possibility.

One argument against this is that inequality among whites, and inequality among blacks, are both rising in the modern period – see https://www.pewsocialtrends.org/2018/07/12/appendix-b-additional-tables-4/psdt-07-12_economic_inequality-appb-01/ . Most immigrants aren’t white or black, so this should be a marker for how inequality is changing among existing citizens, separate from the effect of immigrants naturally being unequally wealthy.

> I’m having trouble seeing the difference between this statement (which economists seem very convinced is true) and “you should worry about immigrants stealing your job” (which everyone seems very convinced is false).

Stealing your job is not the same as driving down wages. The idea that immigrants steal your job is an example of the lump of labor fallacy – it assumes that there’s a specific amount of work to be done, and the only question is how to divide it up, when in fact people’s needs are insatiable, and there’s always something you’d like someone to do, if the salary is low enough.

That immigrants lead to lower wages is a simple example of supply and demand. If there’s a greater supply of labor, the price (the wage) falls.

Another reason why immigrants will decrease wages is remittances. The US has 25 million non-citizen immigrants, let’s say that half of them are in the labor force (same rate as all Americans). These 12.5 million immigrant workers send out $56 billion in remittances, or about $4,500 per worker per year. That’s a huge chunk of their wages that doesn’t get spent in the US, and thus doesn’t stimulate additional labor demand in the US. Even aside from remittances, immigrants may live more cheaply and consume less because their position is insecure, or just because coming from poor countries they are thriftier.

(Note: I’m a first-generation immigrant with a lower consumption rate than most native Americans.)

This argument is flawed to put it nicely, spending doesn’t produce additional labor demand in this way. Even in (totally incorrect) economic models like Keynesian economics spending only stimulates demand under specific economic conditions, and does not hold it as a general rule. We can skip all the theory stuff and jump right to the empirical observations. If this were true then areas with high rates of emigration to the US and high rates of remittances would boom, which we do not see, and there would also be a large correlation between waves of immigration to the US and declines in growth which is the opposite of what is observed.

By a freshman-level supply-demand computation, spending money in the local economy will stimulate labor demand in the local economy, depending of course on what exactly you’re spending it on.

It’s very possible this computation is inapplicable for one reason or another, but it would be good to give an understandable reason why, rather than snidely dismissing it and then jumping to problematic empirical data.

No it doesn’t. Freshman level supply and demand simply shows that increased demand will push prices up which will lead to higher supply. It says nothing about where that supply comes from, nor says anything about local wealth or wages.

Okay, so freshman-level supply and demand plus a kindergartner’s understanding of how the universe works predicts that more money in the local economy, that is “the area in which you can live and commute here”, leads to higher wages in the local economy, because workers cannot travel infinite distances. If you have high labor demand at point X, the supply to satisfy that demand is constrained to come from a finite radius surrounding X.

Was this meant to be a substantive objection, or are you just nitpicking?

I understand that you are attempting to take a shot at me, but you literally just said that you can make your view work if you take a completely ignorant person’s view of the world, which is mostly a shot at your position.

Anyway, lets walk through the logical inferences of supply and demand curves in this situation rather than a child’s model of how the world works.

There is no local economy that fits such a description. There is a price that would encourage you (as in a general person, not you in particular, though it likely applies to you in particular) to commute to the other side of the world for work on a regular basis. There is no finite radius unless you are describing the radius of the earth (plus a bit more for people who want to be astronauts), and the majority of the money that you spend in your local economy is already earmarked for some distant destination. The pineapple you bought at your ‘local’ grocery store was imported from hundreds or thousands of miles away, and the majority of your ‘demand’ for pineapple is going to pay the costs of producing and shipping the pineapple and leaving you immediate area. Likewise the majority of goods and services produced ‘locally’ are sold to non locals.

Lets explore the logical outcomes of what happens if you mandated actual local spending, ie no importing goods or services from beyond some arbitrary, but close, boundary. By the logic of ‘local spending = higher wages” workers should end up wealthier.

Lets start with my pineapple, now they aren’t native to my area so there are two choices, either someone has to build a greenhouse to produce them locally or they are no longer available for purchase. If you could produce pineapples for sale locally at a price less than what it costs to ship them to my locality there would be a strong incentive to do so already, so in the vast majority of cases (near 100%) the price of pineapples goes up or pineapples are unavailable. The real earnings of all local workers in terms of how many pineapples they can purchase must fall, and this should be true of every good that has any single component made outside of the local area.

Facts about the world that are obvious even to a kindergartner are still true. If a kindergartner could point out the flaw in your argument, that usually means your argument is bad.

This obscurantism of “favor the counterintuitive over the obvious, just so you can dunk on non-initiates” is not a way to approach truth.

Okay. Sure. So rather than “there is a finite radius that supplies all the labor demanded in a given area”, we can say “there is an extreme discontinuity in the curve relating commute time and labor supplied at a given price, right around the value that constitutes a reasonable commute”.

This means the same thing in 99% of cases, but it also accounts for the completely inconsequential edge cases of “someone is paying me $1M/yr to commute halfway around the planet”, and so forth, which have absolutely no effect on the implications of this question, but which if not addressed you’ll drag out as a gotcha.

It’s also about 400% more confusing and obscure for that 2% increase in technical validity. Which is why this kind of obscurantism is unproductive; it’s just nerds having “WELL, AKSHUALLY” dick-waving contests.

This is true, but demand for imported pineapples still correlates positively with demand for on-the-spot labor at some level, if only for the people who run the grocery stores and unload the trucks. The magnitude of the correlation will vary depending on the good, but it should always be positive (I can’t think of any counterexamples, at least).

Thus local spending will always increase local labor demand by some positive amount, though the actual magnitude of the amount depends heavily on circumstances. Holding the nature of the demanded goods and services constant, money spent locally still increases local demand, thus local wages, more than money sent overseas for someone else to spend. (Or, for that matter, money stuffed under someone’s mattress.)

If you actually cut off all trade outside the radius of 20 miles or whatever, obviously people’s lives would get worse.

There are two different components to what makes people wealthier: production of goods/services, and distribution of demand. If you lock down all outside trade, you will indeed see demand for local labor increase. Other things being equal, this would make things better for workers. But of course, other things aren’t equal, and the large reduction in available goods implied by shutting down all imports will overpower the demand effect.

This doesn’t have any bearing on the original question, though, which was about spending money locally (whether on locally-produced or imported goods) or shipping it directly overseas as a remittance. It seems obvious that, on the margin at least, the former will produce greater local labor demand, without reducing goods availability.

You haven’t demonstrated that it is a fact, you claimed that S&D curves supported a position, when I pointed out that it wasn’t true you then stated that a completely uninformed opinion of how economics works could allow you to interpret S&D curves that way. You haven’t presented any facts so far.

I have a 6 year old at home, I can get a kindergartner’s view of how the world works at any time, places like SSC for me are places where I can get nuance or work through more complicated positions. If you want to be walked through an econ 101 class I suggest taking such a course, if you want to make bold declarative statements about supply and demand curves I suggest you back them up with more than ‘duh, its obvious’ if you don’t want to appear ‘dunked on’.

No, the implication is exactly the opposite, which is highlighted by the extreme example, is that there is no reasonable definition of ‘local economy’ that adds any value to the discussion. The lead actress at the local playhouse probably studied theater somewhere far enough away to be outside your local economy, and even if she didn’t then the person who designed the lights, wrote the original script, or developed the method of construction for the playhouse.

Are you honestly going to try to tell me that towns don’t exist?

The “local economy” is your town, plus or minus surrounding separate communities that people can move between easily on a daily basis. When we talk about the effect of something on the “local economy”, we’re talking about the effect on the people who live in your town. Is that clear enough for you?

Yes, obviously there’s a whole lot of economic ties between any given town and the larger country surrounding it, but the question of who lives and works where still creates a notable and separable economic sub-unit.

“and there would also be a large correlation between waves of immigration to the US and declines in growth which is the opposite of what is observed.”

This point would only hold assuming that the spending/remittance from immigrants dominates all other factors that affect US economic growth. I don’t think anyone would agree with that.

Another issue is that different immigrant waves (and to be more granular- immigrants from different nations) have had different patterns of spending versus remittances. A lot of that has to do with whether they plan on staying, or on just making money and then returning to their home country.

I think the initial poster’s point does hold, relatively speaking- immigrants spending money on US businesses employing US workers stimulates the US economy to some degree. That same money spent in Honduras (or another country) will stimulate the US economy to a far lesser degree.

If other factors dominated then you would expect no correlation, and not the opposite correlation. However the claim of the original post is that remittances will reduce wages so periods of high immigration would be very likely to at least decrease gpd per capita which is also not observed. The absolute best case argument for this is ‘it happens, but is so small to be negligible’.

Three scenarios.

1. Immigrant works in the US, spends 25% of his salary and saves the other 75%.

2. Immigrant works in the US, spends 25% of his salary, sends the other 75% home in the form of a check.

3. Immigrant works in the US, spends 25% of his salary, spends the other 75% on goods he buys in the US, sends those goods home.

What are the differences in wages for US workers under each scenario and why?

1 depends on what “saving” means. If he stuffs it under the mattress, it’s probably quasi-equivalent to 2. If he invests it somehow, it funds expansion elsewhere, but I don’t have a good feeling for how that differs from spending it directly on goods/services.

2 is the modal case people claim makes immigrants (relatively speaking) bad for local workers. As compared to a local worker making the same salary, the immigrant “consumes” the same amount of local labor demand, but “produces” only 25%. (The remaining 75% presumably gets spent back in the immigrant’s country of origin, and some of that might get back to US demand depending on how trade works, but certainly much less.)

3 is somewhat equivalent to the worker spending his entire salary on US goods for his own consumption, as the US-worker comparison equivalent presumably does.

These models are all simplistic, but probably no more so than any back-of-the-envelope model; they should probably be considered “useful but low-fidelity” on the whole.

If other factors dominate, then you might see the correlation, because the causality runs the other way.

High growth in the US means higher demand for labor, and thus higher wages, which would increase the number of people willing to emigrate to the US. Political constraints may reduce the number of those able to emigrate to the US, but there will also be political demand to allow more immigration.

That is possibly the case in some scenarios, but even if higher relative wages in the US were the causal mechanism you would still have situations where collapsing wages in non US countries, such as during the famines in Ireland and the economic depression in Germany after WW1, are driving immigration. In these situations you would expect the large waves of immigrants to slow US economic growth, especially on a per capita basis, because the gap is widening mostly because of the collapse of the economy in those countries. That we don’t see a drag associated with those immigrant waves indicates once again that the effect is weak at best and likely non-existent*.

*It is my limited understanding that remittances from both examples were common, which fits with the general pattern of economic immigrants to the US throughout its history.

The way I understand it, remittances will increase the supply of the local currency in foreign economies, thus lowering its price, and thus weakening the local currency in the global market; this makes buying things in that local currency more attractive, as the conversion rate makes buying cheaper. It’s why China frequently tried to lower the value of its coin, and why Trump accusses them of currency manipulation. China wants the Renminbi low, so people buy chinese products.

That said, the american dollar is a special case, cause it’s used for transactions everywhere. I assume dollar remittances barely tickle the value of the dollar? Could be wrong here, but 56 billions seems small bananas to the overall amount of trade in dollars everywhere.

I’d be more curious to see what % that is of the country’s GDP that it’s being remitted to

The thing about America for most of its history is that it’s an open system.

In the Old World, countries rarely shifted their boundaries by more than a border province or two. More importantly, that land came ready-populated.

The USA, OTOH, had the relief valve of the frontier. Millions of acres of ‘conveniently uninhabited’ land to settle.

Malthus and Secular Cycles assume a mostly closed system, so we shouldn’t expect them to apply to the US.

My understanding is that Borjas is one of the most pessimistic economists (definitely not the mainstream view), but that even his estimates are really mild: no long run effect for all workers, and only a 5% reduction in wages for high school dropouts. How much `instability` can be attributed to that?

Short Run / Long Run

All native workers: -3.4% / 0.0%

High school dropouts: -8.2% / -4.8%

High school graduates: -2.2% / +1.2%

Some college: -2.7% / +0.7%

College graduates: -3.9% / -0.5%

Got the table from Bryan Caplan’s blog, who got it from Borjas’s textbook.

https://www.econlib.org/archives/2007/03/borjas_wages_an.html

(couldn’t use HTML table formatting for some reason)

My understanding is that Bjorgas’s data refers to the specific instances of immigration he studied, there was a sudden increase in the immigrant population in Miami.

So it’s not reasonable to infer from this that the most pessimistic estimate for the effects of immigration on wages is 5% **For any locale, any magnitude, and any duration**

I can try to double check this later though.

Sweden is currently suffering about 120 attacks with explosives (bombs and hand grenades) yearly, which adjusted for population would be something like 3500 yearly bombings in the U.S.

It’s almost exclusively driven by (frequently loosely) organized crime, with access to old Yugoslavian military surplus.

I suppose because of human nature, if all else fails to explain why. Man is jealous. We share this trait with our evolutionary brothers:

The story of a couple who raised a chimpanzee (Moe) as their surrogate son. After many years, Moe was taken away from them because he bit another person. They visited Moe in the sanctuary which also sheltered other chimps. One day they brought Moe a birthday cake, and the other chimps were watching Moe eat the cake. Those others were out of their cage for some reason. They viciously attacked and mauled the man, biting off his face and genitals before they could be stopped, and didn’t even go for the cake.

If someone else has a lot more money than you, they will be able to inflict a lot more power on you. This seems relevant even if your own standard of living has improved.