I.

I got Jordan Peterson’s Twelve Rules For Life for the same reason as the other 210,000 people: to make fun of the lobster thing. Or if not the lobster thing, then the neo-Marxism thing, or the transgender thing, or the thing where the neo-Marxist transgender lobsters want to steal your precious bodily fluids.

But, uh…I’m really embarrassed to say this. And I totally understand if you want to stop reading me after this, or revoke my book-reviewing license, or whatever. But guys, Twelve Rules For Life is actually good.

The best analogy I can think of is C.S. Lewis. Lewis was a believer in the Old Religion, which at this point has been reduced to cliche. What could be less interesting than hearing that Jesus loves you, or being harangued about sin, or getting promised Heaven, or threatened with Hell? But for some reason, when Lewis writes, the cliches suddenly work. Jesus’ love becomes a palpable force. Sin becomes so revolting you want to take a shower just for having ever engaged in it. When Lewis writes about Heaven you can hear harp music; when he writes about Hell you can smell brimstone.

Jordan Peterson is a believer in the New Religion, the one where God is the force for good inside each of us, and all religions are paths to wisdom, and the Bible stories are just guides on how to live our lives. This is the only thing even more cliched than the Old Religion. But for some reason, when Peterson writes about it, it works. When he says that God is the force for good inside each of us, you can feel that force pulsing through your veins. When he says the Bible stories are guides to how to live, you feel tempted to change your life goal to fighting Philistines.

The politics in this book lean a bit right, but if you think of Peterson as a political commentator you’re missing the point. The science in this book leans a bit Malcolm Gladwell, but if you think of him as a scientist you’re missing the point. Philosopher, missing the point. Public intellectual, missing the point. Mythographer, missing the point. So what’s the point?

About once per news cycle, we get a thinkpiece about how Modern Life Lacks Meaning. These all go through the same series of tropes. The decline of Religion. The rise of Science. The limitless material abundance of modern society. The fact that in the end all these material goods do not make us happy. If written from the left, something about people trying to use consumer capitalism to fill the gap; if written from the right, something about people trying to use drugs and casual sex. The vague plea that we get something better than this.

Twelve Rules isn’t another such thinkpiece. The thinkpieces are people pointing out a gap. Twelve Rules is an attempt to fill it. This isn’t unprecedented – there are always a handful of cult leaders and ideologues making vague promises. But if you join the cult leaders you become a cultist, and if you join the ideologues you become the kind of person Eric Hoffer warned you about. Twelve Rules is something that could, in theory, work for intact human beings. It’s really impressive.

The non-point-missing description of Jordan Peterson is that he’s a prophet.

Cult leaders tell you something new, like “there’s a UFO hidden inside that comet”. Self-help gurus do the same: “All you need to do is get the right amount of medium-chain-triglycerides in your diet”. Ideologues tell you something controversial, like “we should rearrange society”. But prophets are neither new nor controversial. To a first approximation, they only ever say three things:

First, good and evil are definitely real. You know they’re real. You can talk in philosophy class about how subtle and complicated they are, but this is bullshit and you know it. Good and evil are the realest and most obvious things you will ever see, and you recognize them on sight.

Second, you are kind of crap. You know what good is, but you don’t do it. You know what evil is, but you do it anyway. You avoid the straight and narrow path in favor of the easy and comfortable one. You make excuses for yourself and you blame your problems on other people. You can say otherwise, and maybe other people will believe you, but you and I both know you’re lying.

Third, it’s not too late to change. You say you’re too far gone, but that’s another lie you tell yourself. If you repented, you would be forgiven. If you take one step towards God, He will take twenty toward you. Though your sins be like scarlet, they shall be white as snow.

This is the General Prophetic Method. It’s easy, it’s old as dirt, and it works.

So how come not everyone can be a prophet? The Bible tells us why people who wouldn’t listen to the Pharisees listened to Jesus: “He spoke as one who had confidence”. You become a prophet by saying things that you would have to either be a prophet or the most pompous windbag in the Universe to say, then looking a little too wild-eyed for anyone to be comfortable calling you the most pompous windbag in the universe. You say the old cliches with such power and gravity that it wouldn’t even make sense for someone who wasn’t a prophet to say them that way.

“He, uh, told us that we should do good, and not do evil, and now he’s looking at us like we should fall to our knees.”

“Weird. Must be a prophet. Better kneel.”

Maybe it’s just that everyone else is such crap at it. Maybe it’s just that the alternatives are mostly either god-hates-fags fundamentalists or more-inclusive-than-thou milquetoasts. Maybe if anyone else was any good at this, it would be easy to recognize Jordan Peterson as what he is – a mildly competent purveyor of pseudo-religious platitudes. But I actually acted as a slightly better person during the week or so I read Jordan Peterson’s book. I feel properly ashamed about this. If you ask me whether I was using dragon-related metaphors, I will vociferously deny it. But I tried a little harder at work. I was a little bit nicer to people I interacted with at home. It was very subtle. It certainly wasn’t because of anything new or non-cliched in his writing. But God help me, for some reason the cliches worked.

II.

Twelve Rules is twelve chapters centered around twelve cutesy-sounding rules that are supposed to guide your life. The meat of the chapters never has anything to do with the cutesy-sounding rules. “Treat yourself like someone you are responsible for helping” is about slaying dragons. “Pet a cat when you encounter one on the street” is about a heart-wrenchingly honest investigation of the Problem of Evil. “Do not bother children when they are skateboarding” is about neo-Marxist transgender lobsters stealing your precious bodily fluids. All of them turn out to be the General Prophetic Method applied in slightly different ways.

And a lot of them – especially the second – center around Peterson’s idea of Order vs. Chaos. Order is the comfortable habit-filled world of everyday existence, symbolized by the Shire or any of a thousand other Shire-equivalent locations in other fantasies or fairy tales. Chaos is scary things you don’t understand pushing you out of your comfort zone, symbolized by dragons or the Underworld or [approximately 30% of mythological objects, characters, and locations]. Humans are living their best lives when they’re always balanced on the edge of Order and Chaos, converting the Chaos into new Order. Lean too far toward Order, and you get boredom and tyranny and stagnation. Lean too far toward Chaos, and you get utterly discombobulated and have a total breakdown. Balance them correctly, and you’re always encountering new things, grappling with them, and using them to enrich your life and the lives of those you care about.

So far, so cliched – but again, when Peterson says cliches, they work. And at the risk of becoming a cliche myself, I couldn’t help connecting this to the uncertainty-reduction drives we’ve been talking about recently. These run into a pair of paradoxes: if your goal is to minimize prediction error, you should sit quietly in a dark room with earplugs on, doing nothing. But if your goal is to minimize model uncertainty, you should be infinitely curious, spending your entire life having crazier and crazier experiences in a way that doesn’t match the behavior of real humans. Peterson’s claim – that our goal is to balance these two – seems more true to life, albeit not as mathematically grounded as any of the actual neuroscience theories. But it would be really interesting if one day we could determine that this universal overused metaphor actually reflects something important about the structure of our brains.

Failing to balance these (Peterson continues) retards our growth as people. If we lack courage, we might stick with Order, refusing to believe anything that would disrupt our cozy view of life, and letting our problems gradually grow larger and larger. This is the person who sticks with a job they hate because they fear the unknown of starting a new career, or the political ideologue who tries to fit everything into one bucket so he doesn’t have to admit he was wrong. Or we might fall into Chaos, always being too timid to make a choice, “keeping our options open” in a way that makes us never become anyone at all.

This is where Peterson is at his most Lewisian. Lewis believes that Hell is a choice. On the literal level, it’s a choice not to accept God. But on a more metaphorical level, it’s a choice to avoid facing a difficult reality by ensconcing yourself in narratives of victimhood and pride. You start with some problem – maybe your career is stuck. You could try to figure out what your weaknesses are and how to improve – but that would require an admission of failure and a difficult commitment. You could change companies or change fields until you found a position that better suited your talents – but that would require a difficult leap into the unknown. So instead you complain to yourself about your sucky boss, who is too dull and self-absorbed to realize how much potential you have. You think “I’m too good for this company anyway”. You think “Why would I want to go into a better job, that’s just the rat race, good thing I’m not the sort of scumbag who’s obsessed with financial success.” When your friends and family members try to point out that you’re getting really bitter and sabotaging your own prospects, you dismiss them as tools of the corrupt system. Finally you reach the point where you hate everybody – and also, if someone handed you a promotion on a silver platter, you would knock it aside just to spite them.

…except a thousand times more subtle than this, and reaching into every corner of life, and so omnipresent that avoiding it may be the key life skill. Maybe I’m not good at explaining it; read The Great Divorce (online copy, my review).

Part of me feels guilty about all the Lewis comparisons. One reason is that maybe Peterson isn’t that much like Lewis. Maybe they’re just the two representatives I’m really familiar with from the vast humanistic self-cultivation tradition. Is Peterson really more like Lewis than he is like, let’s say, Marcus Aurelius? I’m not sure, except insofar as Lewis and Peterson are both moderns and so more immediately-readable than Meditations.

Peterson is very conscious of his role as just another backwater stop on the railroad line of Western Culture. His favorite citations are Jung and Nietzsche, but he also likes name-dropping Dostoevsky, Plato, Solzhenitsyn, Milton, and Goethe. He interprets all of them as part of this grand project of determining how to live well, how to deal with the misery of existence and transmute it into something holy.

And on the one hand, of course they are. This is what every humanities scholar has been saying for centuries when asked to defend their intellectual turf. “The arts and humanities are there to teach you the meaning of life and how to live.” On the other hand, I’ve been in humanities classes. Dozens of them, really. They were never about that. They were about “explain how the depiction of whaling in Moby Dick sheds light on the economic transformations of the 19th century, giving three examples from the text. Ten pages, single spaced.” And maybe this isn’t totally disconnected from the question of how to live. Maybe being able to understand this kind of thing is a necessary part of being able to get anything out of the books at all.

But just like all the other cliches, somehow Peterson does this better than anyone else. When he talks about the Great Works, you understand, on a deep level, that they really are about how to live. You feel grateful and even humbled to be the recipient of several thousand years of brilliant minds working on this problem and writing down their results. You understand why this is all such a Big Deal.

You can almost believe that there really is this Science-Of-How-To-Live-Well, separate from all the other sciences, barely-communicable by normal means but expressible through art and prophecy. And that this connects with the question on everyone’s lips, the one about how we find a meaning for ourselves beyond just consumerism and casual sex.

III.

But the other reason I feel guilty about the Lewis comparison is that C.S. Lewis would probably have hated Jordan Peterson.

Lewis has his demon character Screwtape tell a fellow demon:

Once you have made the World an end, and faith a means, you have almost won your man [for Hell], and it makes very little difference what kind of worldly end he is pursuing. Provided that meetings, pamphlets, policies, movements, causes, and crusades, matter more to him than prayers and sacraments and charity, he is ours — and the more “religious” (on those terms) the more securely ours.

I’m not confident in my interpretation of either Lewis or Peterson, but I think Lewis would think Peterson does this. He makes the world an end and faith a means. His Heaven is a metaphorical Heaven. If you sort yourself out and trust in metaphorical God, you can live a wholesome self-respecting life, make your parents proud, and make the world a better place. Even though Peterson claims “nobody is really an atheist” and mentions Jesus about three times per page, I think C.S. Lewis would consider him every bit as atheist as Richard Dawkins, and the worst sort of false prophet.

That forces the question – how does Peterson ground his system? If you’re not doing all this difficult self-cultivation work because there’s an objective morality handed down from on high, why is it so important? “C’mon, we both know good and evil exist” takes you pretty far, but it might not entirely bridge the Abyss on its own. You come of age, you become a man (offer valid for boys only, otherwise the neo-Marxist lobsters will get our bodily fluids), you act as a pillar of your community, you balance order and chaos – why is this so much better than the other person who smokes pot their whole life?

On one level, Peterson knocks this one out of the park:

I [was] tormented by the fact of the Cold War. It obsessed me. It gave me nightmares. It drove me into the desert, into the long night of the human soul. I could not understand how it had come to pass that the world’s two great factions aimed mutual assured destruction at each other. Was one system just as arbitrary and corrupt as the other? Was it a mere matter of opinion? Were all value structures merely the clothing of power?

Was everyone crazy?

Just exactly what happened in the twentieth century, anyway? How was it that so many tens of millions had to die, sacrificed to the new dogmas and ideologies? How was it that we discovered something worse, much worse, than the aristocracy and corrupt religious beliefs that communism and fascism sought so rationally to supplant? No one had answered those questions, as far as I could tell. Like Descartes, I was plagued with doubt. I searched for one thing— anything— I could regard as indisputable. I wanted a rock upon which to build my house. It was doubt that led me to it […]

What can I not doubt? The reality of suffering. It brooks no arguments. Nihilists cannot undermine it with skepticism. Totalitarians cannot banish it. Cynics cannot escape from its reality. Suffering is real, and the artful infliction of suffering on another, for its own sake, is wrong. That became the cornerstone of my belief. Searching through the lowest reaches of human thought and action, understanding my own capacity to act like a Nazi prison guard or gulag archipelago trustee or a torturer of children in a dunegon, I grasped what it means to “take the sins of the world onto oneself.” Each human being has an immense capacity for evil. Each human being understands, a priori, perhaps not what is good, but certainly what is not. And if there is something that is not good, then there is something that is good. If the worst sin is the torment of others, merely for the sake of the suffering produced – then the good is whatever is diametrically opposite to that. The good is whatever stops such things from happening.

It was from this that I drew my fundamental moral conclusions. Aim up. Pay attention. Fix what you can fix. Don’t be arrogant in your knowledge. Strive for humility, because totalitarian pride manifests itself in intolerance, oppression, torture and death. Become aware of your own insufficiency— your cowardice, malevolence, resentment and hatred. Consider the murderousness of your own spirit before you dare accuse others, and before you attempt to repair the fabric of the world. Maybe it’s not the world that’s at fault. Maybe it’s you. You’ve failed to make the mark. You’ve missed the target. You’ve fallen short of the glory of God. You’ve sinned. And all of that is your contribution to the insufficiency and evil of the world. And, above all, don’t lie. Don’t lie about anything, ever. Lying leads to Hell. It was the great and the small lies of the Nazi and Communist states that produced the deaths of millions of people.

Consider then that the alleviation of unnecessary pain and suffering is a good. Make that an axiom: to the best of my ability I will act in a manner that leads to the alleviation of unnecessary pain and suffering. You have now placed at the pinnacle of your moral hierarchy a set of presuppositions and actions aimed at the betterment of Being. Why? Because we know the alternative. The alternative was the twentieth century. The alternative was so close to Hell that the difference is not worth discussing. And the opposite of Hell is Heaven. To place the alleviation of unnecessary pain and suffering at the pinnacle of your hierarchy of value is to work to bring about the Kingdom of God on Earth.

I think he’s saying – suffering is bad. This is so obvious as to require no justification. If you want to be the sort of person who doesn’t cause suffering, you need to be strong. If you want to be the sort of person who can fight back against it, you need to be even stronger. To strengthen yourself, you’ll need to deploy useful concepts like “God”, “faith”, and “Heaven”. Then you can dive into the whole Western tradition of self-cultivation which will help you take it from there. This is a better philosophical system-grounding than I expect from a random psychology-professor-turned-prophet.

But on another level, something about it seems a bit off. Taken literally, wouldn’t this turn you into a negative utilitarian? (I’m not fixated on the “negative” part, maybe Peterson would admit positive utility into his calculus). One person donating a few hundred bucks to the Against Malaria Foundation will prevent suffering more effectively than a hundred people cleaning their rooms and becoming slightly psychologically stronger. I think Peterson is very against utilitarianism, but I’m not really sure why.

Also, later he goes on and says that suffering is an important part of life, and that attempting to banish suffering will destroy your ability to be a complete human. I think he’s still kind of working along a consequentialist framework, where if you banish suffering now by hiding your head in the sand, you won’t become stronger and you won’t be ready for some other worse form of suffering you can’t banish. But if you ask him “Is it okay to banish suffering if you’re pretty sure it won’t cause more problems down the line?” I cannot possibly imagine him responding with anything except beautifully crafted prose on the importance of suffering in the forging of the human spirit or something. I worry he’s pretending to ground his system in “against suffering” when it suits him, but going back to “vague traditionalist platitudes” once we stop bothering him about the grounding question.

In a widely-followed debate with Sam Harris, Peterson defended a pragmatic notion of Truth: things are True if they help in this project of sorting yourself out and becoming a better person. So God is True, the Bible is True, etc. This awkwardly jars with book-Peterson’s obsessive demand that people tell the truth at all times, which seems to use a definition of Truth which is more reality-focused. If Truth is what helps societies survive and people become better, can’t a devoted Communist say that believing the slogans of the Party will help society and make you a better person?

Peterson has a bad habit of saying he supports pragmatism when he really supports very specific values for their own sake. This is hardly the worst habit to have, but it means all of his supposed pragmatic justifications don’t actually justify the things he says, and a lot of his system is left hanging.

I said before that thinking of Peterson as a philosopher was missing the point. Am I missing the point here? Surely some lapses in philosophical groundwork are excusable if he’s trying to add meaning to the lives of millions of disillusioned young people.

But that’s exactly the problem. I worry Peterson wakes up in the morning and thinks “How can I help add meaning to people’s lives?” and then he says really meaningful-sounding stuff, and then people think their lives are meaningful. But at some point, things actually have to mean a specific other thing. They can’t just mean meaning. “Mean” is a transitive verb. It needs some direct object.

Peterson has a paper on how he defines “meaning”, but it’s not super comprehensible. I think it boils down to his “creating order out of chaos” thing again. But unless you use a purely mathematical definition of “order” where you comb through random bit streams and make them more compressible, that’s not enough. Somebody who strove to kill all blue-eyed people would be acting against entropy, in a sense, but if they felt their life was meaningful it would at best be a sort of artificial wireheaded meaning. What is it that makes you wake up in the morning and reduce a specific patch of chaos into a specific kind of order?

What about the most classic case of someone seeking meaning – the person who wants meaning for their suffering? Why do bad things happen to good people? Peterson talks about this question a lot, but his answers are partial and unsatisfying. Why do bad things happen to good people? “If you work really hard on cultivating yourself, you can have fewer bad things happen to you.” Granted, but why do bad things happen to good people? “If you tried to ignore all bad things and shelter yourself from them, you would be weak and contemptible.” Sure, but why do bad things happen to good people? “Suffering makes us stronger, and then we can use that strength to help others.” But, on the broader scale, why do bad things happen to good people? “The mindset that demands no bad thing ever happen will inevitably lead to totalitarianism.” Okay, but why do bad things happen to good people? “Uh, look, a neo-Marxist transgender lobster! Quick, catch it before it gets away!”

C.S. Lewis sort of has an answer: it’s all part of a mysterious divine plan. And atheists also sort of have an answer: it’s the random sputtering of a purposeless universe. What about Peterson?

I think – and I’m really uncertain here – that he doesn’t think of meaning this way. He thinks of meaning as some function mapping goals (which you already have) to motivation (which you need). Part of you already wants to be successful and happy and virtuous, but you’re not currently doing any of those things. If you understand your role in the great cosmic drama, which is as a hero-figure transforming chaos into order, then you’ll do the things you know are right, be at one with yourself, and be happier, more productive, and less susceptible to totalitarianism.

If that’s what you’re going for, then that’s what you’re going for. But a lot of the great Western intellectuals Peterson idolizes spent their lives grappling with the fact that you can’t do exactly the thing Peterson is trying to do. Peterson has no answer to them except to turn the inspiringness up to 11. A commenter writes:

I think Nietzsche was right – you can’t just take God out of the narrative and pretend the whole moral metastructure still holds. It doesn’t. JP himself somehow manages to say Nietzsche was right, lament the collapse, then proceed to try to salvage the situation with a metaphorical fluff God.

So despite the similarities between Peterson and C.S. Lewis, if the great man himself were to read Twelve Rules, I think he would say – in some kind of impeccably polite Christian English gentleman way – fuck that shit.

IV.

Peterson works as a clinical psychologist. Many of the examples in the book come from his patients; a lot of the things he thinks about comes from their stories. Much of what I think I got from this book was psychotherapy advice; I would have killed to have Peterson as a teacher during residency.

C.S. Lewis might have hated Peterson, but we already know he loathed Freud. Yet Peterson does interesting work connecting the Lewisian idea of the person trapped in their victimization and pride narratives to Freud’s idea of the defense mechanism. In both cases, somebody who can’t tolerate reality diverts their emotions into a protective psychic self-defense system; in both cases, the defense system outlives its usefulness and leads to further problems down the line. Noticing the similarity helped me understand both Freud and Lewis better, and helped me push through Freud’s scientific veneer and Lewis’ Christian veneer to find the ordinary everyday concept underneath both. I notice I wrote about this several years ago in my review of The Great Divorce, but I guess I forgot. Peterson reminded me, and it’s worth being reminded of.

But Peterson is not really a Freudian. Like many great therapists, he’s a minimalist. He discusses his philosophy of therapy in the context of a particularly difficult client, writing:

Miss S knew nothing about herself. She knew nothing about other individuals. She knew nothing about the world. She was a movie played out of focus. And she was desperately waiting for a story about herself to make it all make sense.

If you add some sugar to cold water, and stir it, the sugar will dissolve. If you heat up that water, you can dissolve more. If you heat the water to boiling, you an add a lot more sugar and get that to dissolve too. Then, if you take that boiling sugar water, and slowly cool it, and don’t bump it or jar it, you can trick it (I don’t know how else to phrase this) into holding a lot more dissolved sugar than it would have if it had remained cool all along. That’s called a super-saturated solution. If you drop a single crystal of sugar into that super-saturated solution, all the excess sugar will suddenly and dramatically crystallize. It’s as if it were crying out for order.

That was my client. People like her are the reason that the many forms of psychotherapy currently practised all work. People can be so confused that their psyches will be ordered and their lives improved by the adoption of any reasonably orderly system of interpretation.

This is the bringing together of the disparate elements of their lives in a disciplined manner – any disciplined manner. So, if you have come apart at the seams (or you have never been together at all) you can restructure your life on Freudian, Jungian, Adlerian, Rogerian, or behavioral principles. At least then you make sense. At least then you’re coherent. At least then you might be good for something, if not yet good for everything.

I have to admit, I read the therapy parts of this book with a little more desperation than might be considered proper. Psychotherapy is really hard, maybe impossible. Your patient comes in, says their twelve-year old kid just died in some tragic accident. Didn’t even get to say good-bye. They’re past their childbearing age now, so they’ll never have any more children. And then they ask you for help. What do you say? “It’s not as bad as all that”? But it’s exactly as bad as all that. All you’ve got are cliches. “Give yourself time to grieve”. “You know that she wouldn’t have wanted you to be unhappy”. “At some point you have to move on with your life”.

Jordan Peterson’s superpower is saying cliches and having them sound meaningful. There are times – like when I have a desperate and grieving patient in front of me – that I would give almost anything for this talent. “You know that she wouldn’t have wanted you to be unhappy.” “Oh my God, you’re right! I’m wasting my life grieving when I could be helping others and making her proud of me, let me go out and do this right now!” If only.

So how does Jordan Peterson, the only person in the world who can say our social truisms and get a genuine reaction with them, do psychotherapy?

He mostly just listens:

The people I listen to need to talk, because that’s how people think. People need to think…True thinking is complex and demanding. It requires you to be articulate speaker and careful, judicious listener at the same time. It involves conflict. So you have to tolerate conflict. Conflict involves negotiation and compromise. So, you have to learn to give and take and to modify your premises and adjust your thoughts – even your perceptions of the world…Thinking is emotionally painful and physiologically demanding, more so than anything else – exept not thinking. But you have to be very articulate and sophisticated to have all this thinking occur inside your own head. What are you to do, then, if you aren’t very good at thinking, at being two people at one time? That’s easy. You talk. But you need someone to listen. A listening person is your collaborator and your opponent […]

The fact is important enough to bear repeating: people organize their brains through conversation. If they don’t have anyone to tell their story to, they lose their minds. Like hoarders, they cannot unclutter themselves. The input of the community is required for the integrity of the individual psyche. To put it another way: it takes a village to build a mind.

And:

A client of mine might say, “I hate my wife”. It’s out there, once said. It’s hanging in the air. It has emerged from the underworld, materialized from chaos, and manifested itself. It is perceptible and concrete and no longer easily ignored. It’s become real. The speaker has even startled himself. He sees the same thing reflected in my eyes. He notes that, and continues on the road to sanity. “Hold it,” he says. “Back up That’s too harsh. Sometimes I hate my wife. I hate her when she won’t tell me what she wants. My mom did that all the time, too. It drove Dad crazy. It drove all of us crazy, to tell you the truth. It even drove Mom crazy! She was a nice person, but she was very resentful. Well, at least my wife isn’t as bad as my mother. Not at all. Wait! I guess my wife is atually pretty good at telling me what she wants, but I get really bothered when she doesn’t, because Mom tortured us all half to death being a martyr. That really affected me. Maybe I overreact now when it happens even a bit. Hey! I’m acting just like Dad did when Mom upset him! That isn’t me. That doesn’t have anthing to do with my wife! I better let her know.” I observe from all this that my client had failed previously to properly distinguish his wife from his mother. And I see that he was possessed, unconsciously, by the spirit of his father. He sees all of that too. Now he is a bit more differentiated, a bit less of an uncarved block, a bit less hidden in the fog. He has sewed up a small tear in the fabric of his culture. He says “That was a good session, Dr. Peterson.” I nod.

This is what all the textbooks say too. But it was helpful hearing Jordan Peterson say it. Everybody – at least every therapist, but probably every human being – has this desperate desire to do something to help the people in front of them who are in pain, right now. And you always think – if I were just a deeper, more eloquent person, I could say something that would solve this right now. Part of the therapeutic skillset is realizing that this isn’t true, and that you’ll do more harm than good if you try. But you still feel inadequate. And so learning that Jordan Peterson, who in his off-hours injects pharmaceutical-grade meaning into thousands of disillusioned young people – learning that even he doesn’t have much he can do except listen and try to help people organize their narrative – is really calming and helpful.

And it makes me even more convinced that he’s good. Not just a good psychotherapist, but a good person. To be able to create narratives like Peterson does – but also to lay that talent aside because someone else needs to create their own without your interference – is a heck of a sacrifice.

I am not sure if Jordan Peterson is trying to found a religion. If he is, I’m not interested. I think if he had gotten to me at age 15, when I was young and miserable and confused about everything, I would be cleaning my room and calling people “bucko” and worshiping giant gold lobster idols just like all the other teens. But now I’m older, I’ve got my identity a little more screwed down, and I’ve long-since departed the burned-over district of the soul for the Utah of respectability-within-a-mature-cult.

But if Peterson forms a religion, I think it will be a force for good. Or if not, it will be one of those religions that at least started off with a good message before later generations perverted the original teachings and ruined everything. I see the r/jordanpeterson subreddit is already two-thirds culture wars, so they’re off to a good start. Why can’t we stick to the purity of the original teachings, with their giant gold lobster idols?

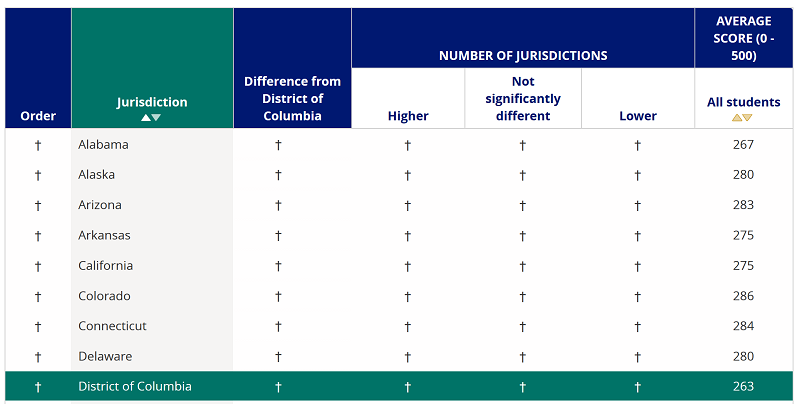

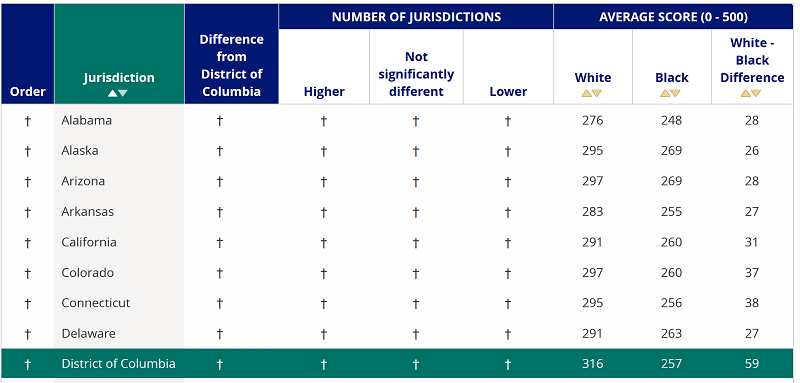

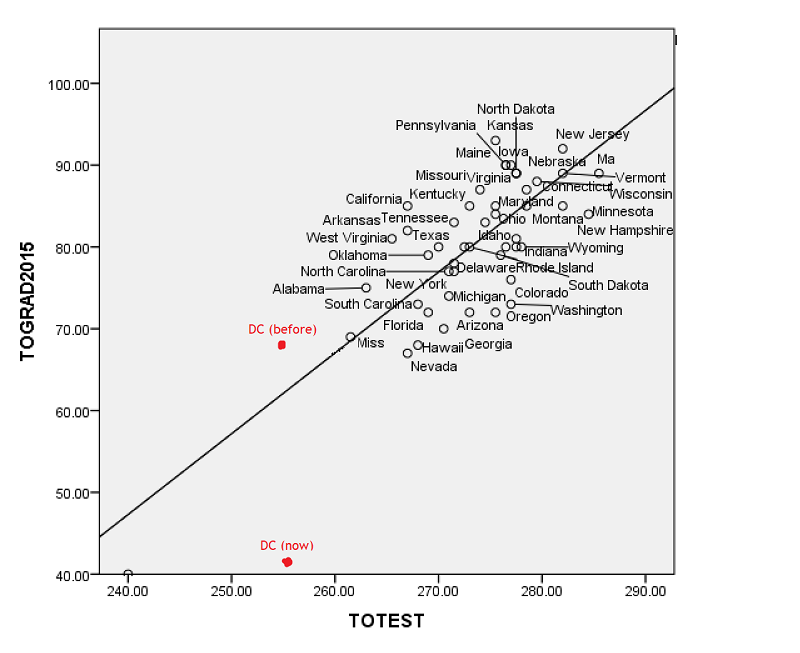

Highlights From The Comments On DC Graduation Rates

Bizzolt writes:

It looks like most other school districts don’t have this policy; it seems plausible that this is the main difference between DC and other poor school districts that nevertheless manage to pass most of their kids.

Userfriendlyyy also focuses on the absences:

Static focuses on absences too:

The absence requirement seems infuriating insofar as it probably fails mostly poor children, and if those children are failing due to the absence requirement rather than because they actually flunk their exams, then it seems mean-spirited to punish inputs rather than actual success.

Maybe they have it because they don’t actually grade students on exam performance (or have lots of different ways to make sure students who flunk exams graduate anyway), but they only want to extend this benefit-of-the-doubt to students who really try. I wonder if it would work to say you can graduate if you manage to make it to school enough times or pass your examinations. That would at least be fairer to poor children who can’t always attend but are able to figure out ways to succeed anyway.

Proyas writes:

Okay, maybe this goes deeper than just the absence thing.

MrApophenia writes:

There’s also this comment on home rule and Puerto Rico which seems to reinforce this idea that districts carefully monitored by competent national authorities do well, and districts that have control of their own standards devolve into corruption and failure really quickly. How does this mesh with the standard federalist/localist/Seeing-Like-A-State style arguments that individual communities know what’s best for them and central planners usually make things worse?

I won’t quote it directly because it’s not from an SSC comment, but some people on the subreddit link to this Reddit post by a DC public school teacher.

See also this thread in the subreddit on how sub-Saharan African schools – despite being much poorer than anywhere in DC – are really well-run, quite safe (except that apparently “baboons are a huge problem”), and a delight to teach at.