Thanks to everyone who commented on the review of The Structure Of Scientific Revolutions.

From David Chapman:

It’s important to remember that Kuhn wrote this seven decades ago. It was one of the most influential books of pop philosophy in the 1960s-70s, influencing the counterculture of the time, so it is very much “in the water supply.” Much of what’s right in it is now obvious; what’s wrong is salient. To make sense of the book, you have to understand the state of the philosophy of science before then (logical positivism had just conclusively failed), and since then (there has been a lot of progress since Kuhn, sorting out what he got right and wrong).

The issue of his relativism and attitude to objectivity has been endlessly rehashed. The discussion hasn’t been very productive; it turns out that what “objective” means is more subtle than you’d think, and it’s hard to sort out exactly what Kuhn thought. (And it hasn’t mattered what he thought, for a long time.)

Kuhn’s “Postscript” to the second edition of the book does address this. It’s not super clear, but it’s much clearer than the book itself, and if anyone wants to read the book, I would strongly recommend reading the Postscript as well. Given Scott’s excellent summary, in fact I would suggest *starting* with the Postscript.

The point that Kuhn keeps re-using a handful of atypical examples is an important one (which has been made by many historians and philosophers of science since). In fact, the whole “revolutionary paradigm shift” paradigm seems quite rare outside the examples he cites. And, overall, most sciences work quite differently from fundamental physics. The major advance in meta-science from about 1980 to 2000, imo, was realizing that molecular biology, e.g., works so differently from fundamental physics that trying to subsume both under one theory of science is infeasible.

I’m interested to hear him say more about that last sentence if he wants.

Kaj Sotala quotes Steven Horst quoting Thomas Kuhn on what he means by facts not existing independently of paradigms:

[Kuhn wrote that]:

A historian reading an out-of-date scientific text characteristically encounters passages that make no sense. That is an experience I have had repeatedly whether my subject is an Aristotle, a Newton, a Volta, a Bohr, or a Planck. It has been standard to ignore such passages or to dismiss them as products of error, ignorance, or superstition, and that response is occasionally appropriate. More often, however, sympathetic contemplation of the troublesome passages suggests a different diagnosis. The apparent textual anomalies are artifacts, products of misreading.

For lack of an alternative, the historian has been understanding words and phrases in the text as he or she would if they had occurred in contemporary discourse. Through much of the text that way of reading proceeds without difficulty; most terms in the historian’s vocabulary are still used as they were by the author of the text. But some sets of interrelated terms are not, and it is [the] failure to isolate those terms and to discover how they were used that has permitted the passages in question to seem anomalous. Apparent anomaly is thus ordinarily evidence of the need for local adjustment of the lexicon, and it often provides clues to the nature of that adjustment as well. An important clue to problems in reading Aristotle’s physics is provided by the discovery that the term translated ‘motion’ in his text refers not simply to change of position but to all changes characterized by two end points. Similar difficulties in reading Planck’s early papers begin to dissolve with the discovery that, for Planck before 1907, ‘the energy element hv’ referred, not to a physically indivisible atom of energy (later to be called ‘the energy quantum’) but to a mental subdivision of the energy continuum, any point on which could be physically occupied.

These examples all turn out to involve more than mere changes in the use of terms, thus illustrating what I had in mind years ago when speaking of the “incommensurability” of successive scientific theories. In its original mathematical use ‘incommensurability’ meant “no common measure,” for example of the hypotenuse and side of an isosceles right triangle. Applied to a pair of theories in the same historical line, the term meant that there was no common language into which both could be fully translated. (Kuhn 1989/2000, 9–10)

While scientific theories employ terms used more generally in ordinary language, and the same term may appear in multiple theories, key theoretical terminology is proprietary to the theory and cannot be understood apart from it. To learn a new theory, one must master the terminology as a whole: “Many of the referring terms of at least scientific languages cannot be acquired or defined one at a time but must instead be learned in clusters” (Kuhn 1983/2000, 211). And as the meanings of the terms and the connections between them differ from theory to theory, a statement from one theory may literally be nonsensical in the framework of another. The Newtonian notions of absolute space and of mass that is independent of velocity, for example, are nonsensical within the context of relativistic mechanics. The different theoretical vocabularies are also tied to different theoretical taxonomies of objects. Ptolemy’s theory classified the sun as a planet, defined as something that orbits the Earth, whereas Copernicus’s theory classified the sun as a star and planets as things that orbit stars, hence making the Earth a planet. Moreover, not only does the classificatory vocabulary of a theory come as an ensemble—with different elements in nonoverlapping contrast classes—but it is also interdefined with the laws of the theory. The tight constitutive interconnections within scientific theories between terms and other terms, and between terms and laws, have the important consequence that any change in terms or laws ramifies to constitute changes in meanings of terms and the law or laws involved with the theory (though, in significant contrast with Quinean holism, it need not ramify to constitute changes in meaning, belief, or inferential commitments outside the boundaries of the theory).

While Kuhn’s initial interest was in revolutionary changes in theories about what is in a broader sense a single phenomenon (e.g., changes in theories of gravitation, thermodynamics, or astronomy), he later came to realize that similar considerations could be applied to differences in uses of theoretical terms between contemporary subdisciplines in a science (1983/2000, 238). And while he continued to favor a linguistic analogy for talking about conceptual change and incommensurability, he moved from speaking about moving between theories as “translation” to a “bilingualism” that afforded multiple resources for understanding the world—a change that is particularly important when considering differences in terms as used in different subdisciplines.

Syrrim offers a really neat information theoretic account of predictive coding:

Suppose you have an alphabet composed of 27 letters (the familiar 26 plus a space). You are interested in encoding it in binary for transmission. Of course you want to use as few bits as possible. How might you go about doing this? The first suggestion would be to assign each letter a bit patter of equal length. In this case, your transmission will take 4.76 bits each. You realize that in english some letters occur much more frequently than others, and to devote the same number of bits to each is wasteful. You find a table recording letter frequencies in common english texts, and reassign the bit patterns to give shorter values to more common letters. In this way, you reduce the number of bits needed to 4.03 per letter on average. Next you realize that some letters are followed by others even more commonly than they appear in normal text. Encoding the bit patterns based not only on the letter in question, but also the previous one reduces your usage to 3.32 bits per letter.

Now we play a game. A person is asked to guess what the current letter is. We tell them if they got it right or wrong. The right answer advances the current letter. They might initially guess the letter ‘t’. If they are right, they might further guess ‘h’. Getting that wrong, they could try ‘a’, and so on. The answer to each question, being yes or no, encodes a single bit. We record how many questions they ask over some long text, and therefore find the number of bits per letter to be 1.93.

(This example derived from Science and Information Theory by Leon Brillouin)

In this latter game, we ask the participants to guess (predict) what a letter is, and therefore define an encoding (coding) for each letter. The method by which a person performs this prediction is twofold. First, they have some idea what the text is saying, and therefore what it will say next. Second, every time they receive a negative response, they realize the text is saying something slightly different than they guessed, and so change their prediction for future letters.

The use of bits highlights an important practical application of all this. When you see some text as I am writing here, you see 4.76 bits for every letter (more, because of capitalization and punctuation and what not). And yet you require only 1.93 bits in order to know what is being said. The extra 2.83 bits take the form of redundancy. If I made some spelling error, or you read what I said particularly quickly, you might miss one of the letters I intended to convey. Yet because you have so many extra unnecessary bits, you can recover what is lost. This is done the similarly to how it was done in our game. As you read, you expect some letter to come next. When you encounter a slightly unexpected letter, you would update your expectation to account for it. When you encounter a completely unexpected letter, you might ignore it and continue as if your expectation was met.

To tie into the card example. A playing card contains log2(52) = 5.7 bits of information. If you are flashed a playing card very quickly, you might only have enough time to get 5.7 bits of information out of it. In this case, you would be forced to assume it is a playing card. If you have more time to look at it, you might be able to extract more bits, but even then, you might so heavily expect a playing card, that you ignore other possibilities.

Going back to the game: A person is allowed to ask which letter is next. But what makes the answer a single bit doesn’t depend on the nature of the question, only the binary nature of the answer. We could permit any yes or no question and still count bits by the number of questions. We then get into the interesting game of what question to ask. If someone had no clue what letter would follow, and wanted to determine it as quickly as possible, they might ask if it appeared in a particular half of the possible letters or the other. Or if they feel sufficiently confident in their guess, they might guess two or more letters at a time. (Brillouin points out the value 1.93 for the number of bits per letter must be too high because we force the player to ask for the letter even when it is obvious)

Now the playing card. You ask: “is it red or no?”, (no), “is it spades or no?”, (no). The prevailing paradigm implies that you now have complete information on the suit. “then it must be clubs?” (no). Once you realize that these are fake playing cards, you ask about the color and the suit independently. One could do a treatment of paradigms in science in a similar way: “is it a particle?” (yes) “then it isn’t a wave?” (no). “wait what?”…

Michael Watts writes:

I find [the quote about dormitive potency] very interesting, because the paradigm everyone mocks (according to this) is the same paradigm current in medicine today.

Years ago, I started to have a problem with the skin on my fingertips peeling off. This got to the point where I consulted a doctor, and he told me “we call this desquamation, which means “it’s peeling”. We don’t know why, and there’s nothing you can do about it.” Eventually, it cleared up by itself. We don’t know why.

There’s an old joke among doctors (at least I hope it’s a joke) that if you don’t know what a patient has, you just repeat their symptoms back to them in Greek or Latin:

“I get headaches at night and I don’t know why.”

“You have idiopathic nocturnal cephalgia.”

“Wow, you figured that out so quickly! Modern medicine really is amazing!”

JP corrects some of my terminology:

It would be better to distinguish more clearly between schools and paradigms. Copernican astronomy, Newtonian mechanics and Predictive Coding are all schools. Only the former two were paradigms; that is, largely unchallenged and generally accepted. In the non- or prescientific stage medicine, psychology, … are currently in, there’s plenty of competing schools, and therefore no paradigm. What is required is an exemplar that sets the stage for a consolidation: a paradigmatic, i.e. paradigm-building, explanation for a phenomenon, after which everyone models their own explanations from hereon. For example (my example, not Kuhn’s), Darwin proposed a particular explanation for how the birds he found on the Galapagos islands got to have their beaks. Since then, a story about how something is in biology counts as an answer if and only if it has the same form as Darwin’s explanation.

Constructing such explanations following the form of the exemplar is the process of Normal Science, which a truly scientific discipline is mostly engaged in: solving puzzles. That sounds dismissive, but solving a puzzle might be as interesting as explaining how birds came about – not just on Galapagos, but in general – that is, they’re dinosaurs. Exciting!

I think the summary is also light on some of what Kuhn in particular was most interested in: in particular, incommensurability. Yes, Kuhn did indeed claim that we can make statements about the falsity of something only from within a certain paradigm (or school). Now Kuhn has plenty of inventory for talking about how a particular school might be thoroughly useless (i.e., it can be inconsistent and utterly fruitless) , but “empirically false from an objective, out-of-paradigm point of view” is not amongst them. In fact, it is inherent especially to a science following the highest standards that it is deeply embedded in one particular worldview, or one might say, ideology.

From John Nerst:

Kuhn gets overinterpreted a lot by people who like to push various species of relativism. As I see it, such overinterpretaton results from taking conclusions that only apply cleanly in the limit case and generalizing them to the whole domain. In this view the parts of a paradigm are all precisely dependent on each other for meaning to such an extent that if a paradigm is only somewhat different from another it is completely different and therefore not comparable at all and the distance between them is not meaningfully traversable. Paradigms are internally integrated and coherent, and insulated from each other. You have to pick one because it’s impossible to mix them, and outside of a particular paradigm a concept means nothing at all. In or out.

Real science isn’t like this, and therefore conclusions that follow from this don’t necessarily apply. Kuhn uses examples that suggest it, but as many have said since then he kind of cherry picks and generalizing the pattern and using it to draw far-reaching and radical conclusions of science as a whole is, well, an overinterpretation.

In real life concepts are both a bit vague and meaningfully more-or-less different (instead of just “the same” or “different”, full stop) in a way that makes it possible and in fact common to compare paradigms and pieces of paradigms (pieces that can be moved around without losing all of their meaning). This is because what we have are typically paradigm-like structures that overlap partially and are at least somewhat reconcilable. This is pretty true in the physical sciences and very true in the social sciences.

The ideas in TSOSR are valuable not because they describe science perfectly but because they work as a corrective to the prevailing view at the time. It’s one pole, and adding it to what we already had creates a new space (a spectrum where there used to be a point) which is great, but it’s important to remember that the new pole isn’t the whole space. To understand science you need both that side of the story and the fact-gathering/positivist/naive inductivist/whatever one. Generalizing only that facet gets you to the wrong place just as much as generalizing only the logical positivist side (or the falsificationist one if you want to get all multidimensional) does.

Virgil Kurkjian gives some eamples of Kuhn explaining how words have different meanings across paradigms:

Revolutionary changes are different and far more problematic. They involve discoveries that cannot be accommodated within the concepts in use before they were made. In order to make or to assimilate such a discovery one must alter the way one thinks about and describes some range of natural phenomena. The discovery (in cases like these “invention” may be a better word) of Newton’s second law of motion is of this sort. The concepts of force and mass deployed in that law differed from those in use before the law was introduced, and the law itself was essential to their definition. A second, fuller, but more simplistic example is provided by the transition from Ptolemaic to Copernican astronomy. Before it occurred, the sun and moon were planets, the earth was not. After it, the earth was a planet, like Mars and Jupiter; the sun was a star; and the moon was a new sort of body, a satellite. Changes of that sort were not simply corrections of individual mistakes embedded in the Ptolemaic system. Like the transition to Newton’s laws of motion, they involved not only changes in laws of nature but also changes in the criteria by which some terms in those laws attached to nature […]

One brief illustration of specialization’s effect may give this whole series of points additional force. An investigator who hoped to learn something about what scientists took the atomic theory to be asked a distinguished physicist and an eminent chemist whether a single atom of helium was or was not a molecule. Both answered without hesitation, but their answers were not the same. For the chemist the atom of helium was a molecule because it behaved like one with respect to the kinetic theory of gases. For the physicist, on the other hand, the helium atom was not a molecule because it displayed no molecular spectrum. Presumably both men were talking of the same particle, but they were viewing it through their own research training and practice. Their experience in problem-solving told them what a molecule must be. Undoubtedly their experiences had had much in common, but they did not, in this case, tell the two specialists the same thing. As we proceed we shall discover how consequential paradigm differences of this sort can occasionally be.

John Schilling notes that I left out part of the story in my explanation of Copernicanism and stellar parallax. The problem wasn’t just that the medievals assumed the stars were close. It was that they appeared to be discs rather than points, which ought to imply close proximity.

absence of parallax isn’t a “glaring flaw” in Copernican theory; it’s only the combination of immeasurably small parallax and large apparent diameter of the fixed stars that is a glaring flaw. A finite diameter implies a finite distance, particularly with the reasonable assumption that stars are the same class of object as the Sun, and the stellar diameters measured by 16th and 17th-century observers corresponded to distances incompatible with the parallax measurements of those observers.

This discrepancy could be resolved by better parallax measurements, or by better measurements of stellar diameter. And in fact, it was in 1720 that Halley used stellar occultation to show that the observed disks were optical anomalies and stellar angular diameter was immeasurably small – thus stars were immeasurably distant and could have immeasurably small parallax.

As you note, it was not long after this (but see also James Bradley and aberration) that the Tychonic model was finally done away with and the Heliocentric model became dominant.

Frog-Like Sensations writes:

It’s natural to find Kuhn’s metaphysics unclear since he was completely unclear about his metaphysics in Structure, and he spent much of the remainder of his career attempting to get clearer on it. Here’s one of the last things he wrote about this:

By now it may be clear that the position I’m developing is a sort of post-Darwinian Kantianism…Underlying all these processes of differentiation and change, there must, of course, be something permanent, fixed, and stable. But, like Kant’s Ding an sich, it is ineffable, undescribable, undiscussible. Located outside of space and time, this Kantian source of stability is the whole from which have been fabricated both creatures and their niches, both the “internal” and the “external” worlds. Experience and description are possible only with the described and describer separated, and the lexical structure which marks that separation can do so in different ways, each resulting in a different, though never wholly different, form of life. Some ways are better suited to some purposes, some to others. But none is to be accepted as true or rejected as false; none gives privileged access to a real, as against an invented, world. The ways of being-in-the-world which a lexicon provides are not candidates for true/false. (“The Road Since Structure”, 12)

Now, you may wonder how you can possibly make something clearer by saying it is a form of Kantianism, and as a non-Kant-scholar, I understand the feeling. But here’s my best stab at what’s going on here.

The most distinctive feature of Kant’s metaphysics is that he claims that a large number of things that are ordinarily claimed to be features of mind-independent reality — that is, of the world as it is in itself as opposed to how it is as represented by minds — are actually features of how our minds must represent the world. This includes both the obvious things, like color, and some really surprising things, like causality and the nature of space and time. So things in themselves do not enter into causal relations or exist in space and time, but they still exist and ultimately ground the nature of the world as it appears to us.

Kant’s view is not relativistic because (1) he thinks that the particular facts that are part of the world of appearance are (non-causally) determined by the nature of mind independent things (the “Ding an sich” mentioned above), and (2) he thinks that all minds impose the same kind of structure on the world (e.g., causal and with space and time).

Kuhn’s proposal is to reject the second claim. Instead of minds all imposing the same type of structure on the world, Kuhn suggests that changing paradigms can impose their respective structures on the world. There is still a mind-indpendent reality that in some way determines how things appear to us and also constrains how successful a given paradigm can be. But all the things that differ between paradigms concern only the features of our representation of reality. Mind-independent reality does not contain any of the relevant properties and so does not settle things one way or another, except insofar as it somehow renders one paradigm more useful than another at solving particular puzzles.

Anyway, I don’t find this view particularly appealing, but it’s the most coherent thing I’ve managed to get out of Kuhn.

I have to admit I have some of the same confusions about Kant as I do about Kuhn. I understand Kant as saying that because we see the world through the mediating influence of our mind, we can never know anything about true reality.

I agree that we see the world through mediating influences, but I’m not sure how far he wants to go with the “never know anything about true reality” piece. For example, I believe I have a car. Can I say with some confidence that true reality contains an object corresponding to my car? That it really and truly has four wheels? That its gas tank is half full? That its interaction with my sense organs explains why I so consistently get such nicely-structured car-related sense-data?

Sure, you can say something boring like “wheels are a social construct, really there are just rubber molecules in a cylindrical pattern”, or even “rubber molecules and shapes are both social constructs, in reality there’s only blobs of quantum amplitude on a holographic boundary entity”, or even “in reality there’s something as far beyond quantum amplitude blobs as quantum amplitude blobs are beyond wheels”. But you can say this kind of thing without Kant, and we just shrug it off as “Yeah, on one level that’s true, but I’m right about the wheels too.” Does Kant have anything to add to this?

One nice thing about the subreddit’s karma system is that it makes it easier for me to figure out who to highlight here. The top-voted comment was by ArgumentumAdLapidem:

This book is near and dear to my heart. As a young ArgumentumAdLapidem, a undergraduate physics major, I was really feeling my oats, and taking some upper-level history classes, just to prove I could do it. For some reason, some poor post-doc was assigned to do recitations, and got me, and I was STEMlording, as young STEMlords are wont to do. He gave me Kuhn to read. I read it, then bought it, then read it again. I had the same conclusion as SSC’s initial premise: this book is a fairly trivial description of the history of science. Lots of dirty laundry, to be sure, but nothing earth-shattering. He, of course, disagreed, and thought the book decisively proved that science was dethroned as the one-true-pursuit-of-Truth. Sadly, this story ends here, there was never a meeting of the minds. Reality intervened, there were finals to study for, and a wildly-overambitious lab project to complete.

But I still have that book. Actually, I have two copies, as someone else, unbidden, gave me a copy as well. Apparently history-of-science grads and philosophy-of-science grads hand them out to physics grads like garlic to vampires. (I readily admit, this might be a commentary on my former and/or current arrogance.) Over the years, I’ve thought about how I would have had that conversation differently. Here’s the current iteration:

To build a skyscraper, we need a foundation. The ultimate weight, volume, and height of the skyscraper is limited by the strength and soundness of the foundation. Science operates in a similar manner … the scope, accuracy, and detail of the scientific project is ultimately limited by the fundamental soundness of the model. The overall history of science, then, is the successive abandonment of one skyscraper for a bigger and better one, one with a stronger foundation, which allows the tower to reach greater heights.

But the devil is in the details, and Kuhn lays them out.

— There are people who have corner offices in the old skyscraper who don’t want to leave. They like their social status in this building, and they discourage (or punish) people who leave the building. They belittle people trying to build a new one.

— It’s not obvious, when the new foundation is being laid, that it will be any better or stronger than the existing one. You have to build the skyscraper (run the experiments) to find out.

— There are a lot of abandoned foundations laying around. They developed cracks, were built on unsuitable ground, or were otherwise deficient in some way that wasn’t discovered until they actually tried to build something on top of it. Most new scientific models fail. There are fads – some hot new model will attract a lot of attention, but begins to fade when it doesn’t show results. The scions of the current building can point to all the failure around them and confidently predict this new attempt will fail as well.

— As the skyscraper is being built, it’s not a smooth process. There will be mistakes and partial rebuilds. Most of the the time, the new building will be a piecemeal framework of exposed structural beams, and will spend most of its time being shorter and less comfortable than the old building. The corner offices of the old building will look out their windows, see a tangle of metal and sweat in the construction site below them, and chuckle at their naive enthusiasm.

— The old building does still grow. There are remodels, things get slicker, more polished, expansions are added, maybe another floor is added. But the foundation can still only take so much, and can only be reinforced to a certain extent. Epicycles.

— The new building has new problems the old building didn’t have. The fire suppression system needs more powerful pumps to push water to ever higher floors. The doorman who just knew everybody has been replaced by a keycard authentication system that is confusing and annoying. These look like flaws to people in the old building, rather than the necessary scaffolding for a bigger, better building. The flat-earther model “Earth must be flat because look how far I can see”, which is simple, must be replaced with the more powerful “Earth is round, and, in a vacuum, you wouldn’t be able to see that far, but we must account for atmospheric refraction, here’s some corrections.” Annoying. But it isn’t just replacing one problem for another. The old problem was a fundamentally-limiting contradiction in the basic model that couldn’t be solved without scrapping the model. The new problem might be solvable. You won’t know until you try. You have to build the building to know.

— There’s a perception problem. The old building holds the height (truth) record basically until the new building reaches the height of the old one. Then the record goes to the new building, and the perception shifts – if you want to be in the game, you got to be in the new building. Some observer, watching the endless parade of people suddenly moving their boxes to the new building, concludes this is all just fad-chasing, like socialites flocking to the hottest club. They’re just doing whatever is popular with the other scientists.

So yes, all this is true. But, after all those failed attempts, all that drama, all that sneering and popularity-games, the skyscrapers still do get taller. As SSC notes, Kuhn barely admits this, in a whisper, on the last page. It is no wonder then, that this book has been used to represent claims far beyond what Kuhn actually claims.

And MoreDonuts on Kuhn vs. Popper:

The other simplistic view [Kuhn] was arguing against was Popper’s notion of falsification. In fact, falsification was the legal precedent for the definition of science at the time, in spite of the fact that philosophers of science never considered it very seriously.

Kuhn’s view also answers the question of why falsification has always been popular among scientists on the ground. When a field is performing “normal science” under a particular paradigm, the acceptance of particular facts or pieces of theory largely does resemble falsification: either the new proposal fits the evidence under the paradigm, or it does not. Kuhn (and Feyerabend) show how this simplistic model falls apart when comparing between paradigms, because there is no way to agree upon what constitutes falsification.

Philosophy of science is controversial because the core conclusion is largely unavoidable: “science” is simply a set of human institutions. There is no hard philosophical grounding for scientific truth. This was an unpopular conclusion historically because Christians were still trying to push Creationism, and progressives needed some argument for why scientific institutions were right and Christian institutions were wrong (the real answer, unironically: our people are smarter and less biased).

A couple of people commented that Kuhn was overstating things because Einstein just expanded upon Newton – a friendly amendment, if you will. Kingshorsey explains (using similar arguments to Kuhn himself) why this isn’t quite right:

I think there are two important lessons to take away from Kuhn: 1) the gap between our ability to model phenomena and our ability to explain those phenomena can be uncomfortably large; and 2) the perceived amount of empirical advantage provided by a new paradigm is not necessarily commensurate with the amount of conceptual adjustment its adoption will require.

A user on the SSC site said that the move from Newtonian to Einsteinian physics is more of a paradigm shuffle than a paradigm shift, because Newtonian equations still work perfectly well for all kinds of calculations. To reframe this user’s statement in terms of point 2, this user thinks that because Einstein’s calculations empirically differ from Newton’s in only certain restricted cases, Einstein’s paradigmatic/theoretical challenge to Newton must be similarly small.

But that’s taking an unreasonably narrow view of what constitutes Newtonianism and Einsteinianism. Neither Newton nor Einstein produced equations in a conceptual vacuum. Rather, both embedded them within a cosmology that rendered them intelligible.

To Newton, space was absolute and yet non-substantive, just the distance between objects. Time was uniform and absolute. Gravity operated instantaneously apart from mediation. Newton believed that these cosmological assertions were necessary for his physics, and that in turn his physics supported these cosmological assertions.

When Einstein comes along, he overturns everything Newton thought about the nature of the universe. Space and time are no longer to be regarded as merely formal properties “within” which things move. Time is relative, space and time are intertwined, and space-time is the very “thing” of which gravity consists.

If we accept both that Einstein’s cosmology is better and that Newton’s math is still pretty good (rather than junk science), we are left with an uncomfortable conclusion. Newton’s degree of success at modeling phenomena in motion did not correlate strongly with his degree of success at explaining the structures or characteristics of reality responsible for that phenomena.

This in turn should lead us to question how much the success of Einstein’s math really supports the cosmology that is bound up with it. After all, what’s to stop a future physicist from saying, “Thanks for these equations, Einstein, I’ll use them where I can, but it’s a shame your model of reality was all wrong”?

And that’s why Kuhn is interesting, and comforting, and frightening. The conservation of certain observations through paradigm shifts forces us to reckon with the possibility that our own scientific successes may one day find a home in a model of reality entirely other than what we imagine now.

Jadagul has a whole blog post worth of comment.

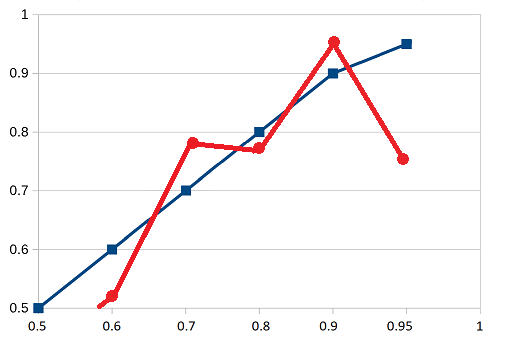

And SpinyStellate doesn’t have much to say about the book, but recommends to us their project SciDash, “rigorous, reproducible, extensible, data-driven model validation [and visualization] for science”. I haven’t looked at it enough to entirely get what’s going on, but at least check it out for its cool visualization of geocentrism vs. heliocentrism (complete with p-values)!

Highlights From The Comments On Kuhn

Thanks to everyone who commented on the review of The Structure Of Scientific Revolutions.

From David Chapman:

I’m interested to hear him say more about that last sentence if he wants.

Kaj Sotala quotes Steven Horst quoting Thomas Kuhn on what he means by facts not existing independently of paradigms:

Syrrim offers a really neat information theoretic account of predictive coding:

Michael Watts writes:

There’s an old joke among doctors (at least I hope it’s a joke) that if you don’t know what a patient has, you just repeat their symptoms back to them in Greek or Latin:

“I get headaches at night and I don’t know why.”

“You have idiopathic nocturnal cephalgia.”

“Wow, you figured that out so quickly! Modern medicine really is amazing!”

JP corrects some of my terminology:

From John Nerst:

Virgil Kurkjian gives some eamples of Kuhn explaining how words have different meanings across paradigms:

John Schilling notes that I left out part of the story in my explanation of Copernicanism and stellar parallax. The problem wasn’t just that the medievals assumed the stars were close. It was that they appeared to be discs rather than points, which ought to imply close proximity.

Frog-Like Sensations writes:

I have to admit I have some of the same confusions about Kant as I do about Kuhn. I understand Kant as saying that because we see the world through the mediating influence of our mind, we can never know anything about true reality.

I agree that we see the world through mediating influences, but I’m not sure how far he wants to go with the “never know anything about true reality” piece. For example, I believe I have a car. Can I say with some confidence that true reality contains an object corresponding to my car? That it really and truly has four wheels? That its gas tank is half full? That its interaction with my sense organs explains why I so consistently get such nicely-structured car-related sense-data?

Sure, you can say something boring like “wheels are a social construct, really there are just rubber molecules in a cylindrical pattern”, or even “rubber molecules and shapes are both social constructs, in reality there’s only blobs of quantum amplitude on a holographic boundary entity”, or even “in reality there’s something as far beyond quantum amplitude blobs as quantum amplitude blobs are beyond wheels”. But you can say this kind of thing without Kant, and we just shrug it off as “Yeah, on one level that’s true, but I’m right about the wheels too.” Does Kant have anything to add to this?

One nice thing about the subreddit’s karma system is that it makes it easier for me to figure out who to highlight here. The top-voted comment was by ArgumentumAdLapidem:

And MoreDonuts on Kuhn vs. Popper:

A couple of people commented that Kuhn was overstating things because Einstein just expanded upon Newton – a friendly amendment, if you will. Kingshorsey explains (using similar arguments to Kuhn himself) why this isn’t quite right:

Jadagul has a whole blog post worth of comment.

And SpinyStellate doesn’t have much to say about the book, but recommends to us their project SciDash, “rigorous, reproducible, extensible, data-driven model validation [and visualization] for science”. I haven’t looked at it enough to entirely get what’s going on, but at least check it out for its cool visualization of geocentrism vs. heliocentrism (complete with p-values)!