I.

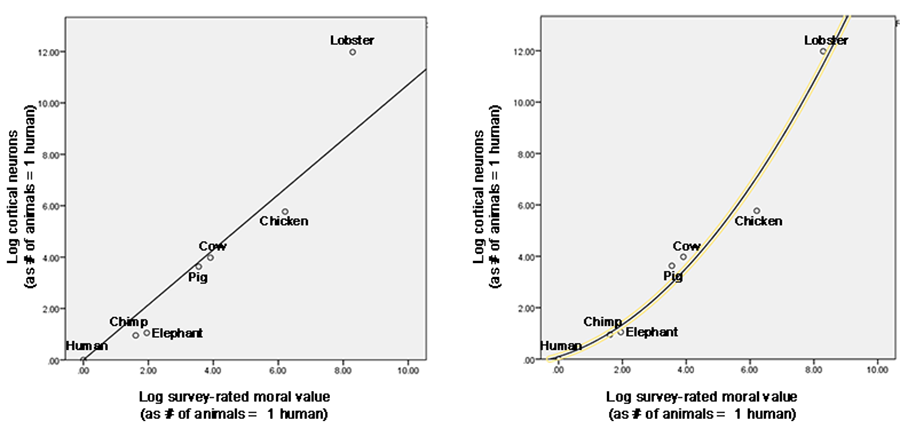

They say “don’t judge a book by its cover”. So in case you were withholding judgment: yes, this bright red book covered with left-wing slogans is, in fact, communist. Inventing The Future isn’t technically Nick Srnicek and Alex Williams’ manifesto – that would be the equally-striking-looking Accelerate Manifesto. But it’s a manifesto-ish description of their plan for achieving a postcapitalist world.

S&W start with a critique of what they call “folk politics”, eg every stereotype you have of lazy left-wing activists. Protesters who march out and wave signs and then go home with no follow-up plan. Groups that avoid having any internal organization, because organization implies hierarchy and hierarchy is bad. The People’s Front of Judaea wasting all their energy warring with the Judaean People’s Front. An emphasis on spectacle and performance over results. We’ve probably all heard stories like this, but some of S&W’s are especially good, like one from an activist at a trade summit:

On April 20, the first day of the demonstrations, we marched in our thousands toward the fence, behind which 34 heads of state had gathered to hammer out a hemispheric trade deal. Under a hail of catapult-launched teddy bears, activists dressed in black quickly removed the fence’s support with bolt cutters and pulled it down with grapples as onlookers cheered them on. For a brief moment, nothing stood between us and the convention centre. We scrambled atop the toppled fence, but for the most part we went no further, as if our intention all along had been simply to replace the state’s chain-link and concrete barrier with a human one of our own making.

S&W comment:

We see here the symbolic and ritualistic nature of the actions, combined with the thrill of having done something – but with a deep uncertainty that appears at the first break with the expected narrative. The role of dutiful protester had given these activists no indication of what to do when the barriers fell. Spectacular political confrontations like the Stop the War marches, the now familiar melees against G20 or World Trade Organization and the rousing scenes of democracy in Occupy Wall Street all give the appearance of being highly significant, as if something were genuinely at stake. Yet nothing has changed, and long-term victories were traded for a simple registration of discontent.

To outside observers, it is often not even clear what the movements want, beyond expressing a generalized discontent with the world…in more recent struggles, the very idea of making demands has been questioned. The Occupy movement infamously struggled to articulate meaningful goals, worried that anything too substantial would be divisive. And a broad range of student occupations across the Western world has taken up the mantra of “no demands” under the misguided belief that demanding nothing is a radical act.

All of this is pretty standard commentary, both from leftists and from rightists making fun of them. What S&W added that I hadn’t heard before was an attempt to portray this all as coming from bad philosophy. I had always assumed most leftist groups sucked because they were primarily made of stoner college kids and homeless people, two demographics not known for their vast resources, military discipline, or top-notch management skills. But S&W believe they suck because they choose to suck, for principled reasons.

They give a few specific principles, but sum them up in the idea of prefiguration: leftist groups should embody utopian leftist values right now. If capitalism is big and complicated and inhuman, leftist groups should be small, simple, and human-scale. If capitalism is coldly rational, leftist groups should be based on transient displays of emotion. If capitalism creates highly-organized hierarchies, leftist groups should be a formless mass of equals. If capitalism is ruthlessly focused on results, leftist groups should prize the journey itself. The goal shifts from concrete results to “prefigurative experience”: where people have a sense of life outside of capitalist strictures, which then sort of mystically lights a spark that kindles revolution in the hearts of all mankind. Or something:

Even granting the problematic assumption that most people would want to live as the Occupy camps did, what efforts might be possible to physically and socially expand these spaces? When theorists face up to this question, vague hand-waving usually ensues: moments will purportedly ‘resonate’ with each other; small everyday actions will somehow make a qualitative shift to ‘crack open’ society; riots and blockades will ‘spread and multiply’; experiences will ‘contaminate’ participants and expand; pockets of prefigurative resistance will just ‘spontaneously erupt’. In any case, the difficult task of traversing from the particular to the universal, from the local to the global, from the temporary to the permanent, is elided by wishful thinking.

Is this a straw man? I have read many leftists complaining that this is what other leftists think, and relatively few leftists saying they think this – though this could be an artifact of who I read. But S&W don’t think it’s straw-mannish. To their credit, they write to an implied audience of pro-folk-politics leftists, begging them to change their ways. More on this later.

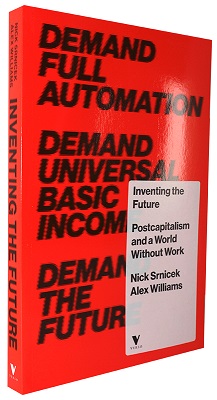

They conclude this section by saying that folk politics has failed and better ideas are needed. They give a brief nod to a long string of leftist victories over the past half-century or so (civil rights, women’s rights, gay rights, environmental regulation, massive increase in most categories of government social spending, etc, etc, etc), but are unimpressed, since these are compromises within capitalism domination. I would have liked to see them address an alternate perspective, where capitalism having to keep making compromise after compromise to defuse pressure from the left is exactly what lefist victory should look like. Would electing Bernie Sanders and instituting Medicare-For-All be just another capitalist compromise? What about electing Andrew Yang and instituting Universal Basic Income? At some point you have to admit that all these “compromises” add up and now you have 90% of what you wanted in the first place. I assume they have some kind of complicated theoretical structural reason why this doesn’t work, but it still seems like a pretty good deal.

II.

What is the opposite of folk politics? S&W point to the Mont Pelerin Society.

The Mont Pelerin Society has a great story, and you should read Kerry Vaughn’s long writeup of the same topic. But the short and oversimplified version is: in the 1940s, everyone serious was either a Big Government Socialist or a Big Government Keynesian. Friedrich Hayek founded the Mont Pelerin Society (named after the site of its first meeting) to promote neoliberalism – here meaning the sort of small-ish government free market thinking common in economics today. At first they were just a few fringe thinkers with no power. But they developed a long-term strategy to change that. Vaughn, S&W, and others sum up the basic points as:

1. Foster intellectual talent

2. Seek long-term academic influence. Getting your members professorships won’t feel as exciting and tangible as reshaping policy immediately. Get the professorships anyway.

3. Push a utopian vision (in the case of the neoliberals, one of freedom and prosperity), along with practical first steps within the Overton Window (eg deregulating the airline industry).

4. Be prepared to step in as saviors when a crisis arrives. Milton Friedman:

There is enormous inertia — a tyranny of the status quo — in private and especially governmental arrangements. Only a crisis — actual or perceived — produces real change. When that crisis occurs, the actions that are taken depend on the ideas that are lying around. That, I believe, is our basic function: to develop alternatives to existing policies, to keep them alive and available until the politically impossible becomes politically inevitable.

The neoliberals spent the 1940s through the 1970s slowly moving through steps 1 – 3. They gathered a stable of friendly academics, journalists, politicians, and (especially) think tanks, sometimes by converting people in positions of power, other times by putting their own loyalists into positions, and especially by founding their own organizations. When the stagflation crisis of the 1970s struck, they had marshalled a strong case as the alternative to the Keynesian system that had produced the crisis. Politicians – especially Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher – agreed to implement their policies, and the rest is history.

S&W abhor the Mont Pelerin Society’s policies, but they are impressed by their success. They describe the result of MPS’ efforts as a “hegemony”, a paradigm so self-consistent and self-contained that it seems like, as the famous saying goes, “there is no alternative”. Neoliberal economics has stock answers to all of the objections raised against it and supports neoliberal politics, which has stock answers to all the objections raised against it and supports neoliberal culture, and so on.

They argue that leftists should abandon folk politics and do something more Mont Pelerinish, which they call a counter-hegemonic project. The Left should create a network of academics, journalists, think tanks, and politicians who come up with leftist ideas, push the culture to the left, and make sure the public knows Communism is the alternative to the current failing system.

Isn’t this pretty much just the “long march through the institutions”? And didn’t it happen thirty years ago?

I’m confused by this whole topic. Marxists seem to talk a lot about Gramsci and “cultural hegemony”, and “march through the institutions” was a phrase used by Gramscians to describe their strategy of controlling institutions in the name of Marxism. And Inventing The Future seems to say “Yes, this is exactly what we want” and even cites Gramsci in a bunch of footnotes. But whenever a non-Marxist mentions this, it gets branded a vile far-right anti-Semitic conspiracy theory. I’m guessing that there’s some subtle distinction between the stuff everyone agrees is true and the stuff everyone agrees is false, and that lots of people will get angry with me for even implying that it might not be a vast gulf larger than the ocean itself, but I can’t figure out what it is and don’t want to land on the wrong side of it and get in trouble.

So let’s say no. Let’s say S&W’s plan of taking over institutions in the name of leftism is completely new. Could this exciting and very original idea be just crazy enough to work?

S&W and their fellow communists aren’t the first group I’ve heard bring up the Mont Pelerin Society as an example to be emulated. As you can tell from the link above, some effective altruists are thinking in this direction too. And “take over academia and dominate the intellectual world” is a good job if you can get it. But it still sounds pretty hard, especially if lots of other people have the same idea.

The neoliberals had some dazzling successes. But so did Napoleon. And if the centerpiece of your strategy is “Take over France, then go from there, after all it worked for Napoleon”, you could be accused of focusing too much on one past success without considering alternatives. Also, you probably can’t take over France. Taking over France is hard. Sure, Napoleon did it once, but think of all the people who must have tried to take over France and failed. I don’t know, seems like a really underspecified plan.

III.

So what is S&W’s plan?

This doesn’t get a huge amount of space in the book, but it seems to be: fight for automation and universal basic income in order to produce a “post-work world”.

There is much discussion of why work is bad, which I appreciate. I think communists are wrong about a lot of things, but when this is all over, I believe their principled insistence that work is bad and that we should not have to do it – maintained firmly against a bunch of people who want basic job guarantees or who consider freedom from work a utopian impossibility – will be one thing they can be really proud of. S&W are very sure work is bad, they manage to express this without accidentally adding on anything blitheringly stupid, and their point that we should head into a post-work world is well-taken.

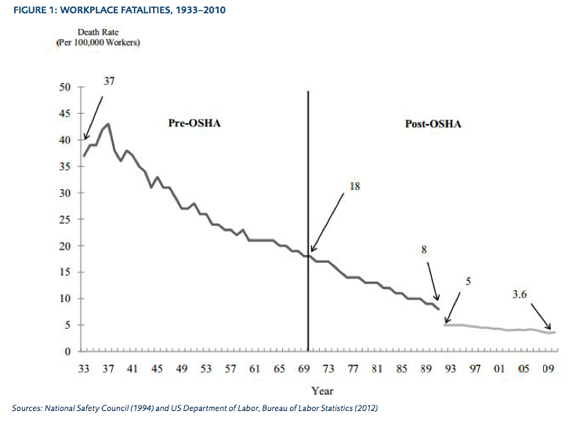

They discuss the increasing role of automation in society, complete with ill-fated predictions that many people who lost their jobs in the Great Recession (just before the book was written) will never get them back and unemployment will remain permanently high. They argue that automation is a vital component of a post-work world, and argue that leftist movements should use whatever strength they have to fight for automating things further. They argue that capitalism is not automating as quickly as it could be, and this is bad for workers:

Full automation is something that can and should be achieved, regardless of whether it is yet being carried out. For instance, out of the US companies that could benefit from incorporating industrial robots, less than 10% have done so. This is but one area for full automation to take hold in, and this reiterates the importance of making full automation a political demand, rather than assuming it will come about from economic necessity. A variety of politices can help in this project: more state investment, higher minimum wages, and research devoted to techniologies that replace rather than augment workers. In the most detailed estimates of the labour market, it is suggested that between 47 and 80 per cent of today’s jobs are capable of being automated. Let us take this estimate not as a deterministic prediction, but instead as the outer limit of a political project against work. We should take these numbers as a standard against which to measure our success.

(notice the suggestion to raise the minimum wage in order to encourage automation; this is more realism than I usually hear in this kind of discussion.)

Alongside the demand for increased automation, leftists should demand a universal basic income:

Drawing upon moral arguments and empirical research, there are a vast number of reasons to support a UBI: reduced poverty, better public health and reduced health costs, fewer high school dropouts, reductions in petty crime, more time with family and friends, and less state bureaucracy. Depending on how UBI is presented, it is capable of generating support from across the political spectrum—from libertarians, conservatives, anarchists, Marxists and feminists, among others. The potency of the demand lies partly in this ambiguity, making it capable of mobilizing broad popular support […]

The demand for a UBI is a demand for a political transformation, not just an economic one. It is often thought that UBI is simply a form of redistribution from the rich to the poor, or that it is just a measure to maintain economic growth by stimulating consumer demand. From this perspective, UBI would have impeccable reformist credentials and be little more than a glorified progressive tax system. Yet the real significance of UBI lies in the way it overturns the asymmetry of power that currently exists between labour and capital. As we saw in the discussion of surplus populations, the proletariat is defined by its separation from the means of production and subsistence. The proletariat is thereby forced to sell itself in the job market in order to gain the income necessary to survive. The most fortunate among us have the leisure to choose which job to take, but few of us have the capacity to choose no job. A basic income changes this condition, by giving the proletariat a means of subsistence without dependency on a job.

S&W finally sum up their platform as:

1. Full automation

2. The reduction of the working week

3. The provision of a basic income

4. The diminishment of the work ethic

I am surprised by points 1, 2, and 4. I don’t disagree with them. But they seem heavily dependent on point 3. If there’s no basic income, automation is a disaster – it just leaves everyone in the same kind of normal bad old unemployment we have now. Same with a diminished work week and lack of work ethic. Usually I think of platforms as the sort of thing where if you get three-quarters of what you want you can declare victory; here three-quarters of the platform would be a dystopia.

On the other hand, UBI would lead inevitably to the other three points. As S&W mention, once living off a UBI becomes a viable alternative to working, many people (though not everyone at once) will choose to do this. That will increase the cost of labor, drive wages up, and encourage businesses that haven’t yet automated to do so. It will also reduce the number of hours people need to (or choose to) work, and once people aren’t working and goods are being produced without labor, there won’t be any need for a work ethic.

I’m especially surprised by the insistence on automation (which takes up more space than this review might indicate). Aside from its ability to enable a UBI, automation itself doesn’t necessarily seem good. If it would cost more to automate a task than to hire workers to do it, there doesn’t seem much advantage in automating, assuming that workers have free choice to take whatever deal the business offers. That is, compare a world in which a factory pays $100,000 per year to operate a car-making robot, and you get a $30,000 a year basic income, vs. a world where a company pays $50,000 per year to hire a car-building employee, and you have the choice between getting a $30,000 a year basic income, or earning $80,000 a year by taking the company’s offer. The second world seems clearly better. I know the usual communist answer is to talk about flow-through effects on who has political power, but I feel like a world in which workers are necessary to make goods is one in which workers have more political power than a world where they aren’t.

So maybe a friendly amendment to S&W’s platform would throw out everything except the UBI?

I doubt they would accept this amendment, but I can’t predict exactly what they would say when turning it down. Certainly they really don’t like libertarians who agree with them on UBI and want to help them with it, but I can’t seem to wring a specific complaint out of their denunciations:

The demand for a UBI, however, is subject to competing hegemonic forces. It is just as open to being mobilized for a libertarian dystopia as for a post-work society. Hence, three qualifications must be added to this demand. First, it has to provide a sufficient amount to live on, second, it has to be universal and third, it has to be a supplement rather than a replacement for the welfare state…

There’s a lot of stuff like this, culminating in a triumphant jab that if there were a UBI, we would end up in the world libertarians claim they want, the one where everyone is free and happy and can choose how to live their lives, rather than the world we all know libertarians secretly do want, where everybody is oppressed by the rich forever. Won’t that be ironic! Won’t the libertarians howl with anguish when they realize what kind of clever political judo trick the Marxists have played on them!

I think I speak for everybody when I say: please don’t throw me in the briar patch! Not the briar patch! Anything but that!

IV.

S&W often use the word “hegemony”, usually in the context of a current neoliberal hegemony or a hoped-for future communist hegemony. I started out reading this as just an emphatic way of saying “power”, as in “the neoliberals are definitely almost-irreversibly in power” or “the communists are definitely almost-irreversibly in power”. After looking into it more, I think the best interpretation of “hegemony” is “paradigm” in the Kuhnian sense, or as the sort of thing that should be in one of the leftmost boxes of this table. A hegemony is a self-consistent way of looking at the world that guides how we think about things and what questions we ask. It is not just made of facts, but also of perspectives, biases, values, and investigational techniques, all coming together into a coherent whole.

I picked up Inventing The Future (on advice from a couple of left-accelerationists I encountered at the Southern California SSC meetup) because I feel bad that I’ve never been able to get my head around the communist paradigm. In the past, I’ve learned new paradigms by reading a lot of books from within that paradigm (and hating them) and debating people from within that paradigm (and thinking they’re crazy). Then fifty books and a hundred debates down the line, I finally get some kind of inkling of where they’re coming from, and then after a while I can naturally make my mind shift into that mode and my only differences with them are at the high-level generators of disagreement. I was born into the Woke California Liberal paradigm, I managed to force myself to understand the libertarian paradigm in college, I managed to force myself to understand the right-wing paradigm a few years ago, and I would really like to be able to understand the communist paradigm too.

This leaves me in the awkward position of needing to read a lot of communist books and wanting to be as accepting as possible towards them, while also inevitably knowing I’m going to hate the first fifty. So I’ll be honest: I really didn’t like Inventing The Future.

Part of this isn’t S&W’s fault. The book was very much not meant for me. Not everything has to be a 101 space. It’s perfectly fine for the Pope to write an encyclical explaining the Catholic position on marriage without including a justification of why you should believe in God, or why Jesus is so great, or why anyone should care what the Pope thinks, or whether marriage should exist at all. People who already believe all of those things should be able to debate the godly Christian papal way of defending marriage among themselves. Likewise, a book for communist true believers about how to win doesn’t necessarily need to justify communism.

But there were times when I feel like even a true believer would have been groping for some reassurance. During their attack on folk politics, S&W were pretty open about how the problem was that groups tried to apply communist principles to communist activism. For example, communism should be non-hierarchical, so some activist groups tried to be non-hierarchical, but then all those activist groups failed. Or: communism says we should abandon market economies for ones based on mutual aid, so Occupy camps tried to have internal economies based on mutual aid, but then those camps couldn’t get resources distributed effectively. S&W’s conclusion was: stop trying to run your activist groups in a communist way, that never works. I’m sure they’re right. But I feel like even true believers might have wondered why real communism, when it came, would go differently. This was never explained.

Likewise, S&W talked quite honestly about how many small-scale experiments with communism have failed. They gave the example of some Argentine workers forming commune-like organizations when that country’s economy collapsed. These kind of worked for a while, but the authors describe them as uninspiring, noting that such communes-within-capitalism could be “as oppressive and environmentally damaging as any large-scale business”. Once the economy recovered, Argentines were pretty relieved to be able to return to normal capitalist living. S&W’s conclusion: you have to destroy all of capitalism at once or it doesn’t count.

I understand this has been a common position in communism since well before Trotsky. But imagine a pharmaceutical company admitting that its drugs have killed everyone who’s taken them so far, but adding “But if we give this drug to everyone in the world at the same time, then it will definitely cure everything!” You would think they would at least add “We recognize this may be a cause of some concern to people who worry past trends won’t suddenly reverse, and we will just end up killing everyone in the world, but here’s why you shouldn’t worry…”. You would think even true believers might want to hear some reassurance at this point. S&W do not provide it.

I don’t want to be too harsh on them. Capitalists have a similar conundrum: if the free market works, how come most businesses are organized as top-down hierarchies? How come there’s a Vice President of Sales who gets hired, promoted, and fired – instead of just some sales consulting businesses offering their time to the CEO at market rate? Capitalists have confronted these issues; probably communists have confronted theirs too. This is the sort of 101 stuff that Inventing The Future is under no obligation to bother with. It just made the book a bad match for me.

And all of this was exacerbated by S&W devoting entire chapters to ideas I considered obvious that were apparently highly controversial to their intended audience. For example, S&W were going to make some demands for what a future communist state should be like. I was interested in hearing these demands. Instead they went on for page after page about whether it was okay to demand things. For example:

We [will] advance some broad demands to start building a platform for a post-work society. In asserting the centrality of demands, we are breaking with a widespread tendency of today’s radical left that believes making no demand is the height of radicalism. These critics often claim that making a demand means giving into the existing order of things by asking, and therefore legitimating, an authority. But these accounts miss the antagonism at the heart of making demands, and the ways in which they are essential for constituting an active agent of change. In this light, the rejection of demands is a symptom of theoretical confusion, not practical progress. A politics without demands is simply a collection of aimless bodies. Any meaningful vision of the future will set out proposals and goals, and this chapter is a contribution to that potential discussion…

When they get to discussing how communism is good, they don’t anticipate any object level complaints about how, eg, maybe capitalism is better. But they do worry that “communism is good” sounds like a universal statement, and universal statements can be exclusionary. So:

To invoke such an idea is to call forth a number of fundamental critiques directed against universalism in recent decades. While a universal politics must move beyond any local struggles, generalising itself at the global scale and across cultural variations, it is for these very reasons that it has been criticised.

As a matter of historical record, European modernity was inseparable from its ‘dark side’ – a vast network of exploited colonial dominions, the genocide of indigenous peoples, the slave trade, and the plundering of colonised nations’ resources. In this conquest, Europe presented itself as embodying the universal way of life. All other peoples were simply residual particulars that would inevitably come to be subsumed under the European way – even if this required ruthless physical violence and cognitive assault to guarantee the outcome. Linked to this was a belief that the universal was equivalent to the homogeneous. Differences between cultures would therefore be erased in the process of particulars being subsumed under the universal, creating a culture modelled in the image of European civilisation. This was a universalism indistinguishable from pure chauvinism. Throughout this process, Europe dissimulated its own parochial position by deploying a series of mechanisms to efface the subjects who made these claims – white, heterosexual, propertyowning males. Europe and its intellectuals abstracted away from their location and identity, presenting their claims as grounded in a ‘view from nowhere’. This perspective was taken to be untarnished by racial, sexual, national or any other particularities, providing the basis for both the alleged universality of Europe’s claims and the illegitimacy of other perspectives. While Europeans could speak and embody the universal, other cultures could only be represented as particular and parochial.

Universalism has therefore been central to the worst aspects of modernity’s history. Given this heritage, it might seem that the simplest response would be to rescind the universal from our conceptual arsenal. But, for all the difficulties with the idea, it nevertheless remains necessary. The problem is partly that one cannot simply reject the concept of the universal without generating other significant problems. Most notably, giving up on the category leaves us with nothing but a series of diverse particulars.

I am tempted to sum up the book as something like “So, obviously everyone agrees that we should overthrow all existing societies to install world communism. But many people doubt that causes lead to effects. Well, I’m here to tell you that we’ll never overthrow all existing societies in favor of world communism unless we take actions that cause that to happen.”

And the authors aren’t just being silly. The book has an epilogue where they respond to criticism they received since the book was published, and it’s all people praising them for their commitment to revolution while also accusing the causes-have-effects thing of being highly problematic. So A+ on writing what your audience needs to hear. I’m just not among them.

V.

Feminist critics of bad pick-up artistry accuse it of “looking for women’s secret cheat code that will make them have sex with you”. The opposite of looking for a cheat code (they say) is actually having and demonstrating value. If women don’t like you, you should try to cultivate value, or demonstrate the value you already have, instead of finding the Three Words And Five Gestures That Will Make Any Girl Get Naked Right Now.

Not everything has to be a 101 space. So maybe my concerns are just an artifact of me wandering into a part of literature where I don’t belong. But at its worst, Inventing The Future feels like a search for the public’s secret cheat code that will make them have a revolution with you.

There is no discussion of why communism is good. There is no discussion of whether the masses might not like communism because they’ve thought about it for a while and decided that communism is a bad idea. There is no discussion of whether some demonstration that communism is good would convince the masses to like it more. Just a laser-like focus on finding the secret propaganda cheat code that will convert the masses to communism.

I don’t know how unfair I’m being here. The most sympathetic reading I can give this is something like “Somewhere off-screen we’ve already agreed that every right-thinking person already knows communism is better than capitalism. And we’ve all agreed that the elites have brainwashed the masses into denying it. And the elites will never give up their own self-interest. So the only remaining question is how we can create a system of organization and publicity and so on powerful enough to reverse the masses’ brainwashing.” This is at least good conflict theory.

But at times S&W seem to dip into a deeper epistemological nihilism. From a paragraph on the rise of neoliberalism:

The crisis (stagflation) was one that no government knew how to deal with at the time, while the solution was the preconceived neoliberal ideas that had been fermenting for decades in its ideological ecology. It was not that the neoliberals presented a better argument for their position (the myth of rational political discourse); rather, an institutional infrastructure was constructed to project their ideas and establish them as the new common sense of the political elite.

Google cannot find any references to “myth of rational political discourse” except in this book. Maybe there’s some long discussion of this idea under another name somewhere, but S&W don’t think it’s worth clarifying or giving any further pointers. They just declare it a myth and move on.

Anyone who spends time on Twitter can be forgiven for thinking that rational political discourse is mythical, and that this is so obvious as to not require justification. I’ve written about these issues before and won’t repeat the entire debate. But one subpoint seems especially important: how does this interact with the plan to build a Mont Pelerin Society of the left?

I mentioned above that “take over academia and all other consensus-building organs of society” isn’t a primitive action. I imagine there are libertarians, tradcons, and fascists trying the same thing. What determines who wins?

I group the Mont Pelerin Society together with the Fabian Society and the EA/AI risk movement; all three groups followed similar strategies and were (or have been so far) remarkably successful. And they all share one key feature: remarkably talented people. My summary of MPS elides this as “cultivate intellectual talent”, but again, this isn’t a primitive action. If everyone tries to cultivate intellectual talent, who wins?

The Fabian Society sort of put some work into cultivating intellectual talent. But a more accurate description of the situation is “couldn’t keep intellectual talent out even if they tried”. They would just be sitting around, dreaming up a new idea for pamphlets, and George Bernard Shaw would wander in, say “Hey, I want to swear allegiance to your group and help you with whatever you need”, and they would say “Okay”, and then Shaw would do some kind of brilliant essay that transformed the way everyone thought about everything. Then the next time they needed something written, H.G. Wells would wander in and say “Hey, can I join and you can give me whatever work you need done and I’ll gladly do it?” and they would shrug and say “Sure”. The “cultivation” was downstream of having a really easy time attracting geniuses.

Right now one of the big issues in effective altruism is more available talented people than the movement knows what to do with. People with a resume a mile long who graduated in the top 10% of their class at Oxbridge show up at organizations, offer to work for peanuts, and the organizations say sorry, we’re still busy finding jobs for the last hundred people like you (EA leaders want me to clarify that you should still apply to EA jobs, because talent-matching is hard and people are generally bad at predicting whether they will be useful). Every so often random prestigious professors who control big pools of institutional resources will email the movement asking how they can join and what they can do.

The Mont Pelerin Society seems to have found itself in a similar situation. From Vaughn’s writeup:

Anthony Fisher was a highly decorated fighter pilot who read Hayek’s Road to Serfdom in Reader’s Digest. He traveled to London to seek out Hayek. “What can I do? Should I enter politics?” he asks. As a decorated veteran with good looks and a gift for public speaking, this was a live possibility.

“No.” replied Hayek “Society’s course will be changed only by a change in ideas. First you must reach the intellectuals, the teachers and writers, with reasoned argument. It will be their influence on society which will prevail, and the politicians will follow.”

Later in 1949, Ralph Harris, a young researcher from the Conservative Party gave a lecture with Anthony Fisher in the audience. Fisher loves what he hears and takes Harris aside after the talk. He explains his idea for an organization to make the free market case to intellectuals. Harris is excited. “If you get any further” he says, “I’d like to be considered as the man to run such a group.”

In 1953 Fisher starts the Buxted Chicken Co. which brought factory farming to Britain. The company begins to show a profit which allows him to revisit his idea for for a free-market institute. Fisher signs the trust deed with two friends and gets back in contact with Harris about running the institute. Harris agrees and becomes the new general director on 1 January 1957. Harris meets Arthur Seldon in 1956 and in 1958, Seldon joins the organization. He was initially appointed Editorial Advisor and become the Editorial Director in 1959.

Thirty years later in 1987, Harris become Lord Harris of High Cross and oversaw an institute which boasted 250 major corporate supporters and a budget equivalent to around £1.6M (in 2016 pounds). Seldon helped produce more than 300 publications and nurtured and developed more than 500 authors. Fisher founded the Atlas Economic Research Foundation which worked to aid in the creation of new think tanks, creating 36 institutes in 18 countries all based on the IEA model.

Note Hayek’s advice to Fisher: “Society’s course will be changed only by a change in ideas. First you must reach the intellectuals, the teachers and writers, with reasoned argument. It will be their influence on society which will prevail, and the politicians will follow.” Maybe Hayek believed the public was generally rational. Maybe he didn’t. But he at least believed reasoned argument worked on some people, and that those people would disproportionately be the intellectuals and thought leaders who could bring everybody else around.

How come the Mont Pelerin Society took over academia, but you didn’t? I think the active ingredient of Mont Pelerin strategy is having a good idea. I don’t necessarily mean objectively good in a cosmic sense. But good in the sense that the smartest people around in your era, using the best information around in your era, will conclude it’s true and important after reasoned debate, and offer to help. Good in the sense that you’re not the sort of people who use the phrase “myth of rational political discourse”. The Mont Pelerin Society has been proven right about a lot of things; does anyone want to un-deregulate airplanes these days? Being right about a lot of things seems heavily correlated with eg Karl Popper and Michael Polanyi joining you, and eg Karl Popper and Michael Polanyi joining you seems heavily correlated with being the sort of group that can get your people into high academic positions.

I admit that Naive Rationalist Praxis is repeating all the reasons why your idea is right – and then, if people don’t listen, repeating them louder and more slowly, like an American tourist trying to communicate in France. I admit that probably you should be more sophisticated than that, and that S&W’s approach hints at a much-needed corrective.

But I still think that if Friedrich Hayek is looking down on us from his gold-plated mansion in Neoliberal Heaven, he’s going to think we’re doing something important right that Inventing The Future is missing.

V.

The last part of the book I found interesting was the emphasis on utopianism.

Both Vaughn and S&W identify the Mont Pelerin Society’s utopianism as part of its strength. From Vaughn:

Hayek believed that liberalism was losing to socialism because the socialists had the courage to be Utopian. The socialists explained the values they were working to attain and justified their project in the context of these values. To combat the socialists, Hayek insisted on explaining the Utopian vision of the neoliberals – a vision he couched in human freedom with competitive markets as the only way to ensure this freedom. As the development of the movement shows, this focus on Utopian visions is an extremely potent weapon.

S&W agree, and say the left’s greatest victories have come in an equally ambitious climate:

Utopian ideas have been central to every major moment of liberation – from early liberalism, to socialisms of all stripes, to feminism and anti-colonial nationalism. Cosmism, afro-futurism, dreams of immortality, and space exploration – all of these signal a universal impulse towards utopian thinking. Even the neoliberal revolution cultivated the desire for an alternative liberal utopia in the face of a dominant Keynesian consensus. But any competing left utopias have gone sorely underresourced since the collapse of the Soviet Union. We therefore argue that the left must release the utopian impulse from its neoliberal shackles in order to expand the space of the possible, mobilise a critical perspective on the present moment and cultivate new desires.

As the last sentence suggests, they believe that capitalism and neoliberalism are incompatible with utopianism, and their success has snuffed out previously widespread utopian ideals:

By contrast, today’s world remains firmly confined within the parameters of capitalist realism.32 The future has been cancelled. We are more prone to believing that ecological collapse is imminent, increased militarisation inevitable, and rising inequality unstoppable. Contemporary science fiction is dominated by a dystopian mindset, more intent on charting the decline of the world than the possibilities for a better one. Utopias, when they are proposed, have to be rigorously justified in instrumental terms, rather than allowed to exist in excess of any calculation. Meanwhile, in the halls of academia the utopian impulse has been castigated as naive and futile. Browbeaten by decades of failure, the left has consistently retreated from its traditionally grand ambitions. To give but one example: whereas the 1970s saw radical feminism and queer manifestos calling for a fundamentally new society, by the 1990s these had been reduced to a more moderate identity politics; and by the 2000s discussions were dominated by even milder demands to have same-sex marriage recognised and for women to have equal opportunities to become CEOs. Today, the space of radical hope has come to be occupied by a supposedly sceptical maturity and a widespread cynical reason.

Anyone who believes that utopian thinking is dead should come to the Bay Area. You can spend Monday listening to an Aubrey de Gray lecture on the best way to ensure human immortality in our lifetimes, Tuesday talking to the Seasteading Institute about their attempts to create new societies on floating platforms, Wednesday watching Elon Musk launch another rocket in his long-term plan to colonize space, Thursday debating the upcoming technological singularity, and Friday helping Sam Altman distribute basic income to needy families in Oakland as a pilot study.

And at every one of these events, you’ll see socialists demanding these people stop, and doing everything in their power to make these people’s lives miserable. Capitalism hasn’t snuffed out utopianism. Utopianism is alive and well everywhere except on the left.

I know the arguments in this space. I know people wonder “what if the benefits of utopia only go to the rich?”. Or “what if letting people have their own private visions of utopia means elites can shape the future?”. Or “when some people don’t have health care, doesn’t spending money on utopian visions seem irresponsible?”. Or a thousand other different things.

But the more of this you do, the less Mont Pelerinny you’ll be. Also, you’ll prevent us from reaching utopia. Which, by definition, would be really really good.

Despite my differences with S&W, I respect them for having a utopian vision. I respect them for putting some work into achieving it. I respect them for (to the limited degree that they can specify exactly what they want) having some decent ideas, even if it’s in a paradigm I can’t quite get my head around. And on the off-chance that Andrew Yang gives them everything they want, by throwing out their entire way of thinking and marching under the banner of libertarianism instead, I intend to be very polite and avoid rubbing their faces in it.