[Epistemic status: I haven’t independently verified each link. On average, commenters will end up spotting evidence that around two or three of the links in each links post are wrong or misleading. I correct these as I see them, but can’t guarantee I will have caught them all by the time you read this.]

You’ve probably seen the Russian city flag with the bear splitting the atom. But this is just the tip of the great Russian animal flags iceberg.

All archaeologists agree that the Roman artifacts dug up around Tucson, Arizona, are a hoax. Everyone agrees that there was no Roman colony of “Calalus” in North America that did battle with the Toltec Indians before finally being defeated in the 9th century AD. But who buried dozens of carefully-forged “crosses, swords, religious/ceremonial paraphernalia containing Hebrew and Latin inscriptions, pictures of temples, leaders portraits, angels, and a dinosaur inscribed on the lead blade of a sword” around Tucson during the 1920s to make it look like there was?

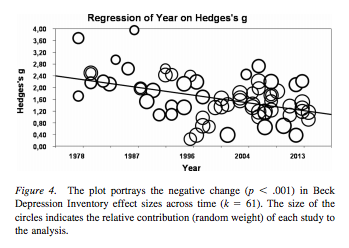

New study by growth mindset proponents finds an effect size of d = 0.11, highest in medium-achieving schools with challenge-supporting peer norms when the moon is in Scorpio. Even if true it should cast doubt on previous studies, since 0.11 is not a human-observable effect size or commensurate with the small-study findings in earlier growth mindset work.

Before genetic engineering, there was atomic gardening, the 1970s practice of planting some seeds in a circle around a radiation source and hoping some of them got beneficial mutations. The process produced modern Ruby Red grapefruits, among other things.

Despite the apparent renewal in interest, only about 1% of Americans think the gap between rich and poor is the most important issue – although it looks like it’s hard to get people to agree on what is a major problem in general.

What is continuous AI takeoff? What would a discontinuity in AI takeoff mean?

One of the engineers who worked on the Viking Mars landers continues to make the case that they discovered life on Mars in the 1970s and everyone is just ignoring this for no reason.

Table Of Organic Compounds And Their Smells. Smell is…a lot more logically organized in a dimensional space than I thought. And in case you have the same question I do: “ethereal” = “smells like ether”.

You might already be following the Navy UFO thing: over the past few years, the Navy has encouraged its pilots to come forward with UFO accounts, signal-boosted the reports, and sponsored UFO research organizations, as if they’re trying to stoke interest for some reason. Now the plot gets weirder: a Navy scientist has filed a patent for a quantum superconducter antigravity drive capable of UFO-like feats of impossible aeronautics. When the Patent Office rejected it as outlandish, the Chief Technical Officer of naval aviation personally wrote the Patent Office saying it was totally possible and a matter of national security, after which the Patent Office relented and granted the patent. The patent thanks UFO researchers in the acknowledgements, includes a picture of a UFO recently sighted by Navy pilots, and does everything short of print in capital letters ‘THIS COMES FROM A UFO’. Scientists who were asked to comment say the proposed drive is “babble” and none of the supposed science checks out at all. Has the Navy fallen victim to conspiracy-peddlers, are they deliberately trying to stoke conspiracy theories for some reason, or what?

Related: Army Partners With Former Blink-182 Founder To Study Alien Technology.

Principles For The Application Of Human Intelligence: Can decision-making by human intelligences introduce bias? Can HI be racist? “Until…human debiasing techniques reach the efficiency of our regular auditing, review, and modification of algorithms, we should not implement these human decision systems.”

BMJ: Failing to complete a prescribed antibiotic course does not contribute to antibiotic resistance.

Along with all of WeWork’s many other red flags, did you know they used kabbalah in decision-making? I would add that the name “Adam Neumann” has kabbalistic implications all by itself, regardless of what decision-making procedures he uses.

A while ago I linked an article about a supposedly disastrous trial of genetically engineered mosquitos in Brazil. This was wrong. The media misunderstood the incident, blew it out of proportion, and it seems that possibly the journal screwed up the original paper somehow? In any case, the scientists who wrote the paper the whole thing was based around are so upset that they are asking for their own paper to be retracted.

California passes a law saying that freelance journalists may not write more than 35 stories per year, which many freelance journalists argue is not enough to survive on and would essentially destroy freelance journalism as a career option. The story seems to be that California wanted to ban Uber from classifying its drivers as freelancers, and the easiest way to do this was just to ban freelance work and carve out exceptions for any form of freelance work the state didn’t want to ban, and whoever was in charge of exception-making randomly chose the number “35” for freelance journalism. The lawmaker responsible has apologized to freelance journalists, but the cynical part of me isn’t sure what apology they can give beyond “we’re sorry our law ending people’s freedom to make contracts with flexible work schedules also affected popular people who can complain”. And if you think I sound angry, as always you should read @webdevmason’s takes (1, 2). Anyway, I think California journalists should feel lucky to be allowed 35 stories; most new housing in the state is limited to two.

Minced oaths: You probably knew “gosh” = “God” and “darn” = “damn”. But did you know “crikey” = “Christ kill me”, and maybe even “bloody” = “by our Lady”? As always, Aaron Smith-Teller takes it too far.

The Middle East is quickly becoming less religious.

Which occupations disproportionately support which Democratic presidential candidates? Mostly what you’d expect, if anything a little too on the nose. Mathematicians for Warren, talent agents for Harris, pizza delivery drivers for Yang, etc. Also, if you want to figure out who is “the candidate of the rich”, you will find all the data you need here.

Jason Crawford’s Roots Of Progress blog on the history of science is going full time. Highly recommended – see eg his post on iron here. There’s also a subreddit.

Latest poll on how Americans view civility: 88% believe that “compromise and common ground should be the goal”, but 83% believe that “I’m tired of leaders compromising my values and ideals [and] want leaders who will stand up to the other side.”

A few weeks ago I posted about the bygone age when people used the Internet for endless arguments about atheism. If you’re sad you missed that era, good news! There’s still a little piece of it going strong over at DebateReligion.reddit.com.

Pollution map: California wildfires vs. a totally normal day in China

Local Bay Area news: mass shooting at a party in an AirBnB house in Orinda, five dead. Orinda responds by banning AirBnB; AirBnB responds by banning parties. Seems to me like they’re just launching pointless attacks on coincidental features of this particular shooting instead of going after the real problem: houses.

Some pushback against Bryan Caplan’s Open Borders: Garrett Jones does an analysis where he shows that on Caplan’s own assumptions, average income of native-born US residents would fall by 40%, from $55,000 to $38,000. Caplan pushes back in a couple of ways. First, even under Jones’ assumptions, global GDP would almost double (because the natives being worse off is more than compensated by immigrants being better off). Second, a bunch of complicated statistical issues with Jones’ analysis. Third, pointing to South Africa, where the end of apartheid did not lower white incomes at all (!), showing that, even in multiracial countries where a richer race/class is outnumbered by a more politically powerful poorer race/class, this doesn’t seem to hurt the richer race/class (at least so far). There’s more at the link. See also the discussion of Open Borders at r/TheMotte.

Did you know: Brazil has more homicides than America + China + Russia + the EU + the rest of the Anglosphere combined?

Last month I linked the BernieBlindness subreddit so people could speculate whether weird media failures to include Bernie Sanders in lists of candidates were mistake or conspiracy. Here’s an even more impressive list of weird media failures to include Andrew Yang. Since I don’t think anyone feels especially threatened by Yang, I count this as strong evidence for the media just being too dumb to remember who all the candidates are consistently.

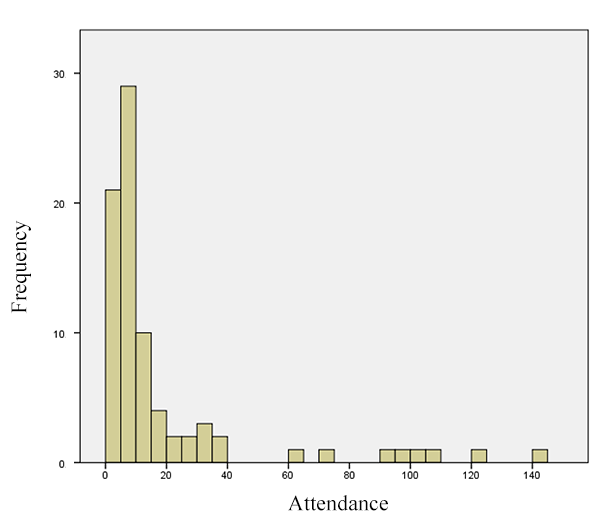

I can’t believe we’ve been rationalists for over a decade now and nobody proposed just doing a scientific study to see whether the Democrats or the Republicans are better. Apparent answer: when studied through careful causation-detecting economic techniques, having a state switch from Democratic to Republican control, or vice versa, has almost no effect on various outcomes of interest like unemployment, crime, or school attendance. This is true even when you limit it to the most extreme cases (state goes from unified Democratic control to unified Republican control and stays that way for many years). Not really sure what to think of this.

LW: autopsy of last year’s self-driving Uber crash. Hindsight is 20-20, and I usually try to hesitate to critique people smarter than I am who are trying to do an insanely difficult thing – but this still seems completely inexcusable and shockingly incompetent.

Texas plane crash was gender reveal party gone wrong; this comes hot on the heels of gender reveal parties being linked to a pipe bomb death and alligator abuse.

A team including Joseph Henrich (author of Secret Of Our Success) publishes a giant paper making the case that Westerners’ psychological differences from the global norm (more individualist, more trusting, less bound by tradition) date back to kinship structures enforced by the early Catholic Church (many of you will have first heard this theory from Twitter user @hbdchick, who’s been using it to explain everything for the past half-decade). There’s been a big (and sometimes nasty) pushback from less-quantitatively-oriented historians; see The Scholar’s Stage for a great play-by-play and a spirited defense of Henrich.

I’ve always wondered how long it takes to make a really good painting; some seem so intricate that I imagine an artist working full-time for a year just to get it right. Turns out I am very off and a skilled artist can make impressive-looking paintings in a few hours.

The Libertarian Party of Kentucky ran a third-party candidate who split the vote and helped a Democrat get elected Kentucky governor this year; here is their statement on the results.

Last month, one of the world’s leading Napoleonic historians was rescued from an icy river, only to have relief turn to horror when he was discovered to be wearing a backpack full of severed human arms. Then things got weird.

Alexey Guzey spent 130 hours chronicling errors in the first chapter of Dr. Matthew Walker’s hit book Why We Sleep, and is suitably upset by it. It seems to be paying off with high-volume sites like Andrew Gelman and Hacker News taking note. No response yet from Walker, but I agree with Gelman’s suggestion that Joe Rogan (who helped popularize Walker) should invite Alexey on his show to talk about it. See also this comment on the subreddit critiquing some of Guzey’s points, with ensuing discussion – the one about not using correlation to infer causation in all-cause mortality stats is a very important point, here and always.

Mark Zuckerberg started Facebook in college and cemented a cultural association between young people and entrepreneurship. But according to the American Institute for Economic Research, this association is wrong: the average successful entrepreneur is 45 when they found their company, the youngest entrepreneurs are the least successful, and a 50-year-old’s company is almost twice as likely to succeed as a 30-year-old’s.

A few weeks ago I reviewed an NYT article on incentives; since then some real economists including David Henderson (Part 2 here) and Bryan Caplan have weighed in with their own thoughts.

If you’re wondering what socialists want, this article on How To Build Socialist Institutions gives a pretty good rundown of moderate socialist proposals (eg nationalize things that have successfully been nationalized in other countries and times, switch various things to co-ops).

Myths about WWI: contrary to the portrayal that officers sat in comfortable tents as they sent enlisted men to certain death, officers were about 50% more likely to die than ordinary soldiers.

From the best of new Less Wrong: Design Principles Of Biological Circuits. I was especially impressed by this passage: “The body uses an integral feedback mechanism to achieve robust exact adaptation of glucose levels, with the count of pancreatic beta cells serving as the state variable: when glucose is too low, the cells (slowly) die off, and when glucose is too high, the cells (slowly) proliferate…mutant cells which mismeasure the glucose concentration could proliferate and take over the tissue. One defense against this problem is for the beta cells to die when they measure very high glucose levels (instead of proliferating very quickly). This handles must mutations, but it also means that sufficiently high glucose levels can trigger an unstable feedback loop: beta cells die, which reduces insulin, which means higher glucose “price” and less glucose usage throughout the body, which pushes glucose levels even higher. That’s type-2 diabetes.” Any experts reading who can confirm if this is true?

“Do you think we’re prepared for the big reveal that the last century and a half of history has been orchestrated by an immortal Andrew Johnson with space-radiation-related superpowers and a grudge?”

New research paper claims that “deaths of despair” are caused by white people being angry at the loss of their white privilege. This should immediately prompt another round of “spot the statistical malpractice people are using to provide scientific cover for the dominant narrative”, but in this case Clay Routledge has already done our work: the paper is just a rehash of the finding that Trump did unusually well in areas hit by the opioid epidemic and deaths of despair. The paper uses Trump support as a proxy for racism, tries to adjust out a few confounders, declares the whole thing probably causal, and so reframes this as “racism must be causing deaths of despair”.

The Department of Homeland Security opened a fake university in Michigan. They convinced immigrant students (who had legitimate student visas) to go there, used their openly-DHS-persona to ensure students the university was legitimate – then arrested those students for visa fraud since they were attending a fake university. They claim that since the university was fake (ie didn’t have any real classes or professors), they were operating a sting on immigrants who were okay with attending a fake university in order to keep their visas. But students claim they weren’t told it was a fake university without classes or professors when they signed up, and some students who transferred out once they figured out it was fake were also arrested. I’ve been reading about efforts to abolish the DHS recently, and the people involved stress they don’t mean that nobody should ever enforce immigration laws. They mean that the DHS, specifically, as an organization, has a screwed-up culture, and that dissolving it and leaving immigration enforcement to various other departments the way it was before 2001 would work better. This university thing seems like Exhibit A.

Man wields narwhal tusk to thwart terrorist’s murder spree is now a thing that has happened.

Kurt Vonnegut’s ice-9 is science fiction, but the same process – a new crystalline form arising in a substance, spreading unstoppably, and destroying everything that relied on the old form – happened in real life to the AIDS drug ritonavir (tumblr post, paper).

Zero HP Lovecraft: God-Shaped Hole