[This is an entry to the 2019 Adversarial Collaboration Contest by BlockOfNihilism and Icerun]

Note: For simplicity, we have constrained our analysis of data about pregnancy and motherhood to the United States. We note that these data are largely dependent on the state of the medical and social support systems that are available in a particular region.

Introduction: Review of abortion and pregnancy data in the United States

We agreed that it was important to first reach an understanding about the general facts of abortion, pregnancy and motherhood in the US prior to making ethical assertions. To understand abortion rates and distributions, we reviewed data obtained by the CDC’s Abortion Surveillance System (1). The Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System (PRAMS), Pregnancy Mortality Surveillance System (PMSS) and National Vital Statistics datasets were used to evaluate the medical hazards imposed by pregnancy (2, 3, 4). Finally, we examined a number of studies performed on the Turnaway Study cohort, maintained by UCSF, to investigate the economic effects of denying wanted abortions to women (5, 6, 7, 13).

Abortion rates by trimester and maternal age: Using data collected by the CDC, 638,169 abortions were performed in the United States in 2015. Data was received from 49/52 reporting areas, suggesting that these rates are likely close to the population rates. This was equivalent to 188 abortions per 1000 live births, a 24% decline from 2006. Of these, approximately 65% were performed prior to 8 weeks of development, and 91% before 13 weeks of development. An additional 7.6% were performed at between 14-20 weeks. Approximately 90% of abortions were performed on women older than 19, and adolescent women between the ages of 18-19 accounted for 67% of the abortions in women under 19. By race, non-Hispanic black women were most likely to undergo an abortion (25 per 1000 women), while non-Hispanic white women were least likely (6.7 per 1000). This translates to a rate of 390 abortions per 1,000 live births in non-Hispanic black women and 111 per 1,000 live births in non-Hispanic white women. (1) These data show that most abortions are undertaken prior to the end of the first trimester, that most women choosing an abortion are adults, and that non-Hispanic black women are disproportionately more likely to choose an abortion.

Mortality and morbidity associated with abortion and pregnancy: On average, there were 0.62 fatalities per 100,000 legal abortions between 2008-2014 (six reported fatalities in 2014). For comparison, in 2015 there were 17.2 pregnancy-related fatalities per 100,000 live births in 2014. These data suggest that an abortion is generally safer than attempting to carry a child to term. Also, it is important to consider the racial disparities within these data. For example, African-American women were three times as likely to die as a result of pregnancy than non-Hispanic white women (42.8 vs 13 per 100,000 live births). The reasons for these disparities are unclear. (3)

Pregnant women are also at risk for severe morbidity associated with pregnancy and delivery, with approximately 50,000 women experiencing at least one severe complication in 2014. This translated to a rate of ~140/10,000 deliveries. Approximately 1.2% of live births resulted in severe maternal complications. Women can also experience significant psychological morbidity after pregnancy, as 1 out of 9 women who deliver a live fetus develop postpartum depression. We were unable to find CDC data for morbidity resulting from abortion procedures; however, one publication reported approximately 2% of abortions result in a medical complication. As this data did not discriminate between minor and severe complications, it would be reasonable to assume that abortions result in a lower overall severe complication rate than pregnancy. We will make the further assumption (based on educated guessing) that late-term abortions are more risky than early-term abortions. (2)

From these data, we conclude that pregnancy and delivery pose a significant risk to the mother’s health. These risks are greatest for African-American and Native American women. By comparison, abortion appears to pose much lower risks of death, and probably much lower risks of morbidity. Consequently, mothers undergo unique and substantial hazards which are imposed by pregnancy.

Comparison of pregnancy-associated risks and other common risk factors: It is difficult to compare the risks of pregnancy with other factors due to the disparate means of measuring those risks (per live birth, vs per person). However, a naive interpretation of the available data suggests that, while pregnancy is relatively unlikely to lead to severe consequences, it compares in risk to other common activities. For example, the mortality rate associated with motor vehicle accidents is 12.1 per 100,000 people. This is similar to the risk of death per 100,000 live births for women in the US (16.7). (8)

An alternative approach is to examine how pregnancy, childbirth and post-pregnancy changes affect overall mortality. According to the National Vital Statistics Reports (Volume 68, 2016), pregnancy and childbirth was the 6th leading cause of death for women(all races and ethnicities) aged 20-24 and 25-29, accounting for 652 deaths in the two groups combined. Pregnancy and childbirth was the 10th leading cause of death for women between the ages of 15-19 (28 deaths). These data indicate that pregnancy is a leading cause of death in women of child-bearing age. (4)

Socioeconomic costs of unwanted pregnancy: The socioeconomic effects of abortion denial have been studied extensively on the Turnaway Study cohort at the University of California-San Francisco. One study on this cohort found that mothers who were denied a wanted abortion due to gestational age experienced a significantly higher likelihood of being unemployed, in poverty and using public assistance programs like WIC. (6) Another study based on this cohort found that already-born children of a mother denied an abortion were significantly more likely to live in poverty and fail to meet developmental milestones.(5) Mothers who were denied abortions were also less likely to have and meet aspirational goals.(7) These data indicate that women who received wanted abortions experience significantly less socioeconomic strain than women who are denied an abortion.

Adoption vs abortion: Adoption is commonly suggested as an alternative to abortion. Adoption does eliminate the direct socioeconomic burdens of parenthood. However, adoption is rarely considered as an alternative to abortion. For example, in the U.S., there were approximately 18,000 adoptions compared with nearly 1 million abortions. A recent article in The Atlantic did an excellent job of summarizing potential reasons for the discrepancy. Adoption obviously does not alleviate the physical burdens and hazards of pregnancy. Additionally, several studies have suggested that women do not choose adoption due to worry about their perception of the emotional effect of giving away a child. Pro-adoption groups also suggest that both pro- and anti-abortion advocates fail to emphasize or properly counsel women on considering adoption as an alternative to abortion. (9)

Who are the stakeholders in the abortion question? The mother, the father, the fetus, and society at large. The mother’s unique interests are her safety and health, the development of a unique bond with a new human life, and the economic, emotional and physical burdens of motherhood. The father, if held responsible, shares the economic and emotional burdens of parenthood. The fetus, once it has developed the fundamental features of a human being, has at least a theoretical interest in preserving its life. Society at large has an interest in justice and preserving the rights of its members, if only out of self-interest for the individuals within that society. At some point in time, a fetus becomes considered a member of that society, with the same rights as all other individuals. Consequently, the point of conflict arises when a mother (or both parents) desires to terminate a pregnancy prior to delivery.

The question: At what point during development does abortion become a moral wrong?

Starting positions: At conception (icerun), At fetal viability/minimal neurological activity (BlockofNihilism)

icerun’s Position: A Future Like Ours: Conception

Many arguments for and against abortion pick out a characteristic of the fetus – its size, level of consciousness, ability to feel pain, etc. – and go on to argue why this characteristic, or lack of one, gives the fetus a right to life. Unfortunately, these characteristics tend to have accidental byproducts – they may give the right to life to sheep or remove it from infants. The Future Like Ours arguments begin by determining what best accounts for the wrongness of killing people like you and me (who people on both sides of the abortion debate agree it is wrong to kill). And then use this standard to determine if it is wrong to kill a fetus (who it is contested whether it is wrong to kill).

A Future Like Ours

In Why Abortion is Immoral, Marquis argues killing someone like you or me is prima facie wrong because the deceased is robbed of a valued future like ours. (10) Killing most directly and significantly harms the one who is killed.

The harm to the deceased is the loss of her valued future. Her future would have included all of the experiences, relationships, and works that were valuable for their own sake or means to something valuable. She loses not only those parts of the future she valued in the moment but also those experiences, relationships, and works that she would have come to value as she grew older or is not currently aware of as she grew older: a 16 year old may not value parts of his future whether that be a career, family, or woodwork but if the teenager had been allowed to develop may have come to value these parts of his future.

In summary, it is wrong to kill somebody like you or me because it robs them of a future like ours. The value of a fetus’ future is its current experience, relationships, and works that the fetus values now and those experiences, relationships, and works that the fetus would come to value. A typical fetus cannot currently value it’s experiences, relationships, and works but as the fetus develops it will come to have the same experiences, relationships, and works that we do. Therefore, a fetus has a future like ours. By this definition, it is wrong to kill a fetus from the point of conception (for the record, Marquis does not claim it is wrong to kill a fetus from the point of conception; however, this seems to be the implication).

Intuitions: The future like ours argument works off common assumptions by pro and antiabortion proponents. In doing so it both avoids assuming an ought from an is and creates common ground. The account of the wrongness of killing humans must fit within these intuitions: it must account for why it is wrong to kill typical adult humans, infants, and those who are suicidal but it is not wrong to kill typical sperm, eggs, and some animals. However our intuitions differ on whether it is wrong to kill a typical single cell zygote. Intuitively we both believe it is not wrong to kill a typical zygote, however BlockofNihilism believes this strongly and I believe this weakly. Many anti-abortion advocates have the opposite intuiition.

For BlockofNihilism, this future like ours argument violates his strong intuition that it is not seriously wrong to kill a zygote and this argument fails. For myself, it violates a weak intuition and while on it’s own is not enough to completely overcome the intuition, it holds the strongest sway and influence over my view on abortion as it offends the least intuitions and is more coherent than most other arguments.

BlockofNihilism’s Position: Conscious Perception and Viability

Abortion is morally acceptable until the fetus develops the structures required for perception of external stimuli, with exceptions for preserving the life and health of the mother. Abortion is acceptable because a fetus does not experience conscious suffering “like ours” and simultaneously imposes a significant physical, mental and economic burden on the mother. As the minimum requirements for conscious perception are actually met after fetal viability, I suggest we fall back on viability as a compromise ethical barrier to abortion.

When does the fetus develop “conscious” perception? By conscious perception, we mean perception which a human person would recognize as their own. Obviously, this question in general pushes the limits of our ability of description. As perception is an (obviously) complex topic, I will use the perception of physical pain as an example of the requirements for conscious perception. Pain, too, is a complex psychological concept that arises at the intersection of physical sensation with emotional constructs. At the minimum empirical level, certain neurological structures are necessary, but not sufficient, for the perception of pain. Thus, until these structures are present and active, perception (as we understand it) cannot occur. (10)

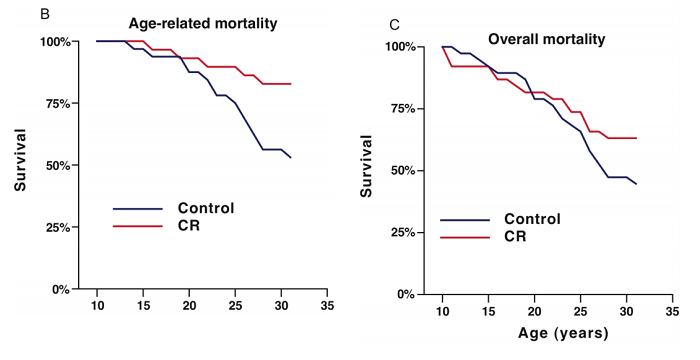

To experience pain, afferent nerves must synapse with spinothalamic nerves projecting to the thalamus, which then connect to thalamocortical neurons projecting to the cortex (the region of conscious experience). Thus, all three components (peripheral pain sensor, thalamic project, and functioning cortex) must all be active for the perception of pain. Based upon multiple studies, nociceptive neurons develop around 19 weeks, thalamic afferents reach the cortex at 20-24 weeks, and somatosensory activity provoked by thalamic activity is detectable around 28-29 weeks. Several behavioral studies have found that at 29-30 weeks of development, fetal facial movements in response to pain are like adults. However, these results have been contradicted by other studies, and these findings may represent non-voluntary and unconscious responses to stimuli rather than the conscious perception of pain. (10)

In any event, a fetus does not have the required neurological structures for what we would recognize as the conscious experience of pain until at least 29 weeks of development, three weeks into the third trimester. (10) Prior to full integration of the various components of the nervous system, and the development of an active cortical system, the pain experience of a fetus would likely be akin to that of a comatose individual- no conscious experience at all.

As other types of experience require these same structures to be active, we can conclude that a fetus does not have the minimum capacity for conscious experience until approximately 29 weeks of development. Thus, when considering an abortion prior to this stage of development, we are balancing (1) the harms posed to the mother, a conscious agent, against (2) an entity that does not “experience” anything. To me, this suggests that abortion is permissible at this point.

The fetus is truly viable at ~27 weeks: With intensive care, a preterm neonate can survive at as early as 24 weeks of gestation. However, survival rates at this point are approximately 50%. Also, these severely preterm neonates are at a significantly increased risk of a variety of both short- and long-term complications. By 27 to 28 weeks, the fetus can be delivered and survive in most cases without major interventions. So, true fetal viability and the development of the fundamentals for conscious experience are roughly concurrent, with viability likely being reached prior to conscious experience.

Potential harms and viability: Viability means that the fetus no longer requires the mother’s body to survive. Within the womb, the fetus imposes both a significant immediate burden as well as the potential for significant harms. Once safely delivered, these harms are no longer present. While the mother is still on the hook for the economic and emotional burdens of motherhood, her life is no longer at risk. Also, while adoption is a possibility after birth, it is obviously not an option prior to delivery. Consequently, viability represents a special moment in the development of a fetus- it can live without posing a significant hazard to the mother’s physical well-being. While we could not find solid evidence (likely due to the very low number of late-term abortions performed), my educated guess is that an abortion at this late stage is approximately as dangerous as performing a natural delivery or C-section. Consequently, at viability, it is reasonable to treat the fetus as having full human rights and intercede to protect its life.

icerun’s rebuttal to BlockofNihilism:

Viability: The only difference between a viable fetus and an infant is location, which is not a moral distinction (except in cases of direct harm to the mother) therefore a viable fetus is seen as having the same right to life as an infant. The chain would seem to continue. The primary distinction between a viable fetus and nonviable fetus is that a nonviable fetus survival depends solely on one person (the mother) whereas a viable fetus survival can depend on others. This does not appear to be a moral distinction either and so the viability argument appears to be very closely related to the argument that the fetus gains the right to life at birth or when it becomes an infant. Therefore, a viable fetus would have the same right to life of a newborn however without further reasoning, it seems likely a fetus gains the right to life earlier.

Experience: BlockofNihilism argues that since a fetus before 29 weeks is not capable of conscious experience it is not capable of suffering and therefore it is not wrong to abort. However, there are times when adult humans are not conscious and are even unable to achieve consciousness in the case of temporarily comatose humans. Because they are not conscious they are not capable of suffering. This argument seems to allow for the killing of sleeping and temporarily comatose humans as long as they do not suffer, feel pain, or realize what is happening in the moment.

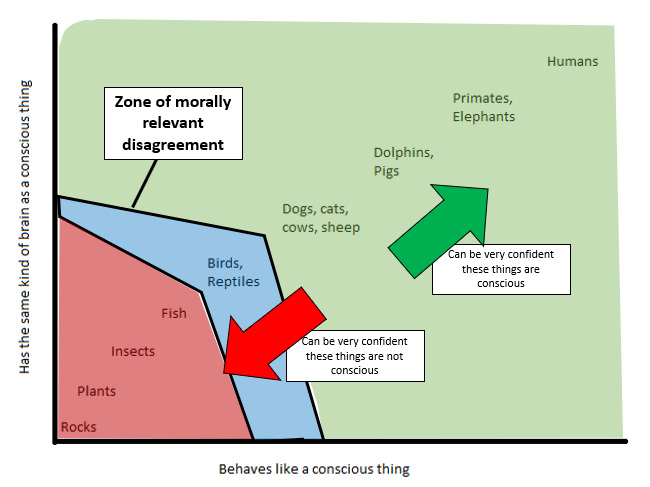

Further, an adult would likely not recognize the consciousness of a fetus as its own. It is unlikely that a fetus or infant has a sense of self and they seem to operate at a significantly lower level of self-awareness. Though we do not have a good understanding of the level of consciousness a fetus holds, a dog appears to operate at a higher stage of consciousness than a fetus though this is very speculative.

For these reasons, the experience of suffering is not what makes it wrong to kill a fetus or human.

BlockofNihilism’s Rebuttal of the Future Like Ours Account:

Consciousness-based and FLV-based arguments arrive at the same place: For me, any ethical argument that places the interests of a non-conscious entity incapable of experience above the interests of a conscious agent capable of both rational decision-making and of suffering is intuitively absurd. Prior to the development of the basics for neurological experience, the fetus represents the potential for a future life of value or the potential to be a conscious agent. In either case, I do not believe that the potential outweighs the present!

I understand how the future life-of-value (FLV) argument can seem to apply to a fetus: We imagine the entity that will come from the fetus, imagine its potential for an FLV, and extrapolate rights from there. However, a fetus represents the potential for having a life of value and cannot be said to currently possess that future in the way implied by Marquis. I believe the intuitive appeal of the future life-of-value argument arises from our experience and knowledge of what a “future” constitutes. However, fetuses prior to their development of the basic neurological structures required for experience cannot have or value their “future.”

My interpretation is informed by Boonin’s famous critique of Marquis’ “future of value” argument. (11) According to Boonin, the intuitive value of the future can be found in the dispositional ideal present value of a future. A dispositional value or belief is one that is held by someone but not consciously on the mind. An ideal value or desire is one that would be held if one had full information about the situation. The dispositional ideal desire formulation is more parsimonious as it does not invoke potential desires but only present ones. Thus, the wrongness of killing someone like you or me is the taking of a future like ours they dispositionally, ideally, and presently value. Upon developing the neurological structures necessary for experience, a fetus can begin to (at least unconsciously) desire food, close touch, and parent’s voice. The necessary neurological structures for these desires, and for meeting the minimum requirement for having an FLV, is near or at the point of viability.

Consciousness-based accounts do not allow for murdering sleeping people! There is a clear distinction between an entity that has had the experience of consciousness (a sleeping or temporarily comatose individual) and an entity that has never been conscious. A sleeping person still has her memories, desires and agency encoded within her brain; the fact that she is temporarily unaware of those attributes does not mean they do not exist! Conversely, a fetus prior to its developing consciousness has no memories, desires or agency. It cannot be said to be a person yet. My argument is simple- prior to having the minimum requirements for consciousness there is absolutely no chance whatsoever that a fetus can experience any harm like we (persons) do.

Once these structures are developed and active, it becomes far more difficult to determine “when” a fetus or infant reaches consciousness. At this point, I become squeamish with the prospect of destroying something that potentially does have a conscious experience (including a “future of value” concept) like ours. The moral calculus changes: Instead of balancing a person’s interest (mother) vs a nonperson’s interests (fetus), we now have a person vs (maybe a person?). This is where, to be safe and prevent potential harms, we can draw a clear ethical line.

Preventing abortion prior to viability will cause significant harms: As previously discussed, substantial scientific evidence suggests that preventing wanted abortions will lead to harm. First, there would be a significant increase in morbidity and mortality associated with pregnancy. This increase would disproportionately impact economically disadvantaged and minority women. Second, women denied wanted abortions are significantly more likely to suffer socially, economically and psychologically. Perhaps most importantly, women (or both parents) are denied agency and denied the ability to make the ethical decision for themselves according to their unique circumstances and beliefs.

Location, location, location! Viability represents the best point for ethical compromise: Terminating a fetus after it is capable of living “on its own” is equivalent to infanticide. In the special case of a fetus, location does have moral significance. The fetus, living within and dependent upon the mother’s body, poses immediate and potential costs and hazards to the mother. By contrast, once delivery has taken place the fetus/neonate no longer poses these threats. While the mother still has the significant economic and social burdens of motherhood, these burdens are unlikely to lead to immediate physical harm. And for the mother unable to cope with these burdens, adoption or surrendering the care of the infant to the state is an option once delivery of a viable neonate has taken place.

Icerun’s Defense of the Future Like Ours Account

Capacity of a fetus to have a future: The fetus does not have a potential future nor is the fetus’ future simply a concept in its brain. The future of a fetus are those unrealized experiences the fetus will have if its development is not impeded. Likewise, a 20-year-old will be a 25-year-old with experiences, relationships, and works if it’s development is not impeded. Sometimes a human’s development is impeded by natural causes in which case we mourn their loss of a future or by conscious decisions in which case we mourn and try to provide restitution as best possible.

In fact, one’s future is most certainly not in or dependent on the brain. A 4-year-old does not have a good understanding of what it is like to be a 60 year old yet being a 60 year old is still a part of his future. If the 4-year-old is killed, it has lost not only on the relationships it understands as a 4-year-old but also a future that includes a career or children or what it would have found valuable and meaningful as an adult.

Boonin’s present future account fails: Marquis and Boonin account for the value of the parts of our future that we do not know yet (ex: our future in 20 years) in different ways. Marquis includes both our present valuation of the future and our future valuation of the future while Boonin argues for a present ideal desire of the future. However, to have an ideal desire, one must first have an actual desire (if an actual desire is not required, then one could say the zygote or trees have ideal desires).

Though the fetus can be said to have desires, these desires are unconscious. A conscious desire is willed and chosen to a certain extent whereas an unconscious desire is simply the body doing what the body does; a personification which is often helpful but, in this case, not relevant. The unconscious desire for warmth is simply the brain releasing chemicals based on external states. Similarly, the zygote will begin to multiply based on external states, stem cells will divide into different cells based on external states, the heart begins beating based on external states. The heart beating or zygote splitting apart seem to fulfill the requirement of some unconscious desire. The fact that it is the brain responding to outside stimuli is not morally relevant – the fetus does not appear to be aware of a desire for warmth just as it is not aware of the heart’s desire to pump blood. If conscious desires are necessary then newborns and possibly older infants likely do not have a right to life as they do not appear to have conscious desires or a sense of self. In this case though it is more parsimonious, it fails because it does not grant infants a right to life.

Conclusions

icerun’s conclusion: The point where the fetus gains the right to life is rightly contested and debated as I do not believe there are any completely coherent and consistent arguments that define the point of development where the fetus gains the right to life.

The latest possible point where abortion may be permissible appears to be viability where the sole difference between an infant and a fetus is the location (one inside the womb and dependent on a specific person and the other outside the womb that could be cared for by others). However, abortion may be impermissible at an earlier point and the point of viability does not appear to have a moral significance that makes the fetus seriously wrong to kill.

At the end though, I have not come to a solid position at what point it becomes wrong to kill a typical fetus. And it is important to note, have failed to provide a coherent argument. In making my decision on abortion three items weigh heaviest:

First, in cases of consensual sex (excluding rape), parents hold a strong positive obligation to provide and protect a child once it gains the right to life. This obligation comes from the fact that children have a right to life, require support to survive, and that the parents engaged in activities that are known to create humans. Second, the future like ours argument points to the fetus gaining a right to life at conception and though this goes against my intuitions, it comes the closest to providing a coherent and consistent argument. It is a model to understand why it is seriously wrong to kill humans and thus points to an earlier rather than later point in the fetus’ development. My choice of this argument is likely biased by various intuitions that I hold and others would not doubt come to focus on other flawed arguments based on their own intuitions. Third, there are situations where bearing a child brings significant issues and problems for either the mother or fetus where abortion apears the best option.

A mesh of all three in light of it being uncertain when the right to life begins for a fetus perhaps leads to the stance that abortion should be safe, legal, and rare that investigates abortion on a cases by case basis that attempts to balance the weightiness of aborting a fetus with practical costs and difficulties that are imposed on parents.

BlockofNihilism’s conclusion: If my ethical standard were to be adopted and used to change current practice in the US, it would allow for a few more elective early third-trimester abortions than are currently performed. However, it would have little to no effect on the current situation, as most abortions are performed well before viability. I believe that communicating our knowledge about the fetus pre-viability, including its lack of internal conscious experience, would significantly reduce the potential for psychological harms to women who choose abortions. In contrast, if abortion after conception was prevented, there would be several negative consequences. There would be a significant increase in pregnancy-related morbidity and mortality that would disproportionately affect minority and socioeconomically distressed women. The likely uptick in illegal abortions would increase the likelihood of unsafe abortions, further increasing the risk of morbidity and mortality. Finally, the denial of wanted abortions imposes pronounced social and economic strains on new mothers and their families. These consequences are, obviously, of significant moral concern.

I remain convinced that abortion is acceptable prior to fetal viability. I believe that the intuitive appeal of the FLV argument is, as suggested by Boonin, not applicable to a fetus prior to developing the fundamental requirements for neurological experience. Even if we decided that the FLV argument pertained to fetuses, the fact that abortion pre-viability cannot cause conscious harm outweighs any potential for FLV that could result from a fetus carried to term. I believe (like Aesop) that a bird in the hand (the mother’s rights, interests and potential for harm) far outweighs a bird in the bush (the non-conscious potential person represented by a fetus).

Shared conclusion: Abortion is never a happy choice. Regardless of our ethical position on the abortion question, we agree that new people are of tremendous value! Improvements in the delivery and efficacy of birth control options, increases in social support systems for mothers and parents, reducing pregnancy-associated morbidity and mortality and increasing access to alternative options like adoption are all essential factors in reducing the number of abortions and any potential harms that arise from them. By focusing on these issues rather than on preventing abortions directly through legal or ethical edicts, we can make having a child a more reasonable and safe option than at present.

Works cited:

1. https://www.cdc.gov/reproductivehealth/data_stats/abortion.htm

2. https://www.cdc.gov/prams/index.htm

3. https://www.cdc.gov/reproductivehealth/maternal-mortality/pregnancy-mortality-surveillance-system.htm

4. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nvsr/nvsr68/nvsr68_06-508.pdf

5. Foster DG, Raifman S, Gipson JD, Rocca CH, Biggs MA. Effects of Carrying an Unwanted Pregnancy to Term on Women’s Existing Children. February 2019. The Journal of Pediatrics, 205:183-189.e1.

6. Foster DG, Biggs MA, Ralph L, Gerdts C, Roberts SCM, Glymour MA. Socioeconomic Outcomes of Women Who Receive and Women Who Are Denied Wanted Abortions in the United States. January 2018. American Journal of Public Health, 108(3):407-413

7. Upadhyay UD, Biggs MA, Foster DG. The effect of abortion on having and achieving aspirational one-year plans. November 2015. BMC Women’s Health, 15:102. (Request pdf)

8. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/accidental-injury.htm

9. https://www.theatlantic.com/health/archive/2019/05/why-more-women-dont-choose-adoption/589759/

10. Marquis, Don. “Why Abortion Is Immoral.” The Journal of Philosophy, vol. 86, no. 4, 1989, pp. 183–202. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/2026961.

11. Lee SJ, Ralston HJP, Drey EA, Partridge JC, Rosen MA. Fetal Pain: A Systematic Multidisciplinary Review of the Evidence. JAMA. 2005;294(8):947–954. doi:https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.294.8.947

12. Boonin, D. (2002). A Defense of Abortion (Cambridge Studies in Philosophy and Public Policy). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/CBO9780511610172

13. https://www.ansirh.org/research/turnaway-study