[This is an entry to the Adversarial Collaboration Contest by TracingWoodgrains and Michael Pershan (a k-12 math teacher), on advanced students in the education system]

“What do America’s brightest students hear? Every year, across the nation, students who should be moved ahead at their natural pace of learning are told to stay put. Thousands of students are told to lower their expectations, and put their dreams on hold. Whatever they want to do, their teachers say, it can wait.” – A Nation Deceived, p.3

“There is an apparent preference among donors for studying the needs and supporting the welfare of the weak, the vicious, and the incompetent, and a negative disregard of the highly intelligent, leaving them to ‘shift for themselves.'” – Hollingworth, 1926

1. Eager to Learn and Underachieving

Pretend you’re a teacher. With 25 students, who gets your attention during class?

There’s the kid who ask for it, whose hand is constantly up. There’s also the quiet kid in the corner who never says a word, but has been lost in math since October, who will fail if you don’t do something. There’s the student in the middle of the pack, flowing along. Finally, there’s the kid who finishes everything quickly. She’s looking around and wondering, what am I supposed to do now?

In a survey of teachers from 2008, just 23% reported that advanced students were a top priority for them, while 63% reported giving struggling students in their classes the most attention. A 2005 study found the same trend in middle schools, where struggling students receive the bulk of instructional modification and special arrangements. This was true even while 73% agreed that advanced students were too often bored and under-challenged in school. While teachers, it seems, are sympathetic to the smart bored kid, that’s just not a priority for them.

This isn’t to blame teachers who are under all sorts of pressure to carry low-performing students over the threshold and who, in any event, are only trying to do what’s best for their kids. Which is the most urgent concern? If you don’t equip a kid with the skills they need, next year’s class might be a disaster for them. Or maybe they’ll fail out of school. And behavior problems? Often those begin with academic struggles. Gifted children, on the other hand — they’re on the way to becoming gifted adults. They can take care of themselves, for a minute, the logic goes. More often than not, the teacher will encourage the early finisher to go read a book, or start homework, or do anything at all while the teacher works to help the quiet, lost kid in the corner.

If the kids are just a little bored, that’s nothing strange. It’s hard to find someone who wasn’t bored in school sometimes. For many top students, already poised for achievement, this turns out just fine. And yet, there are persistent stories of how the lack of challenge can turn into something more serious.

One version of the story goes like this: from a young age, a student finds the work in school easy. It doesn’t take long for them to expect school to be easy for them — it becomes a point of pride. Over years of floating through school, an identity takes hold. Then, one day, maybe after years of schooling, something finally becomes challenging for the student… but there’s nothing nice about this challenge. The challenge is now a threat. The student begins to find school challenging, and their world falls apart. They feel isolated and misunderstood at school. They lash out. They hate it, and they can’t wait to get out.

When we asked Reddit users and blog readers to describe their experience of school, we heard versions of this story:

- Miserable waste of time, was almost never offered opportunities to learn. Largely ignored teachers and read books during class. I felt like it was a profound injustice that I was punished for doing so. I now have kids of my own and will be home-schooling them.

- I was bored. The pace was too slow and work was not interesting. Being forced by law to get up early and go somewhere to learn things I already know means permanent and firm dislike.

- I went to local public schools for kindergarten through high school, and the experience wasn’t good. Academically, the classes were slow and poorly taught. Even the AP classes were taught at the speed of the slowest student, which made the experience excruciating. The honors and regular classes were even worse: I was consistently one or more grades ahead of the rest of the class in every non-AP class except honors math. I learned not to bother studying or doing homework even in the AP classes which probably wasn’t great for my work ethic.

The stories of student pain and underachievement in school get more intense as we consider cases of extremely precocious children. The pressures on the student increase, and without help a student often experiences isolation from their peers and a whole other host of difficult feelings. Miraca Gross studied students like these in Australia and found that precocious students were often suffering in silence. Speaking particularly about precocious students who underachieve, she writes:

The majority of the extremely gifted young people in my study state frankly that for substantial periods in their school careers they have deliberately concealed their abilities or significantly moderate their scholastic achievement in an attempt to reduce their classmates’ and teachers’ resentment of them. In almost every case, the parents of children retained in the regular classroom with age peers report that the drive to achieve, the delight in intellectual exploration, and the joyful seeking after new knowledge, which characterized their children in the early years, has seriously diminished or disappeared completely. These children display disturbingly low levels of motivation and social self-esteem. They are also more likely to report social rejection by their classmates and state that they frequently underachieve in attempts to gain acceptance by age peers and teachers. Unfortunately, rather than investigating the cause of this, the schools attended by these children have tended to view their decreased motivation, with the attendant drop in academic attainment, as indicators that the child has “leveled out” and is no longer gifted.

What do we make of these stories? How common are such experiences?

From the literature on “gifted underachievement” we get partial confirmation — underachievement is a real phenomenon, supported by numerous case studies. According to a survey of various school practitioners, underachievement is the top concern when it comes to gifted students. By definition, advanced students are only a small percent of each student body, so few are affected in any given place, but on a national scale it becomes a more serious problem.

This is not just a problem for the affluent. It has persistent impacts on Black students, poor students, and students who are learning English, who are less often recommended for gifted programs or special accommodations. Here’s one way this manifests itself: in one study, 44% of poor students identified as gifted in reading in 1st Grade were no longer academically exceptional by 5th Grade. For higher-income families, only 31% of 1st Graders experience this slide.

The lack of attention to this group extends to the research. It’s difficult to pin down the number of students impacted. While underachievement is a real phenomenon, current research doesn’t tell us very much about the factors contributing to gifted underachievement. What studies have been done tend to focus almost entirely on things like whether students with ADHD or unsupportive families underachieve, rather than looking at controllable factors like the sort of teaching students experience in school.

Schools are the institutions in charge of educating kids. Those who rush into school, eager to learn, should not walk out feeling rebuffed and ignored. This is doubly true for talented kids from at-risk populations, who may not have the support structure outside of school to ensure their success if school has no time for them. It’s clear, though, that we cannot degrade the experience of other students to help those who already have an academic leg up. Is there a feasible approach to address this problem without making things worse?

We have good reason to think that personalized attention makes a huge difference to a student’s learning. Research suggests that tutoring that supplements a student’s coursework is a very effective educational intervention. Benjamin Bloom caught people’s attention with the idea of a 2 standard deviation effect in the 1980s. More recent research has lowered that sky-high estimate to more realistic numbers, and a meta-analysis found an effect size of 0.36, still a powerful impact, enough to take a student from the 50th percentile of achievement to the 64th.

If supplemental tutoring works, the dream goes, what if we replaced classroom work entirely with tutoring? Can’t we just do that for gifted underachievers and precocious students? We have tantalizing success stories of this kind in the education for precocious children. In a famous case, John Stuart Mill‘s father decided that the philosophy of utilitarianism needed an advocate, and planned a demanding course for him. Mill didn’t underachieve: he learned Greek at age 3, Latin at age 8, and flourished as a philosopher. László Polgár declared he had discovered the secret of raising “geniuses” and went about showing it by tutoring his daughters in chess from the age of 3. It’s hard to argue with his results: two grandmasters and an international master, one of whom became the 8th ranked chess player in the world and the only woman ever to take a game off the reigning world champion.

Though this sort of tutoring seems like a dream come true for underachieving gifted students, in practice it’s a non-starter in schools. (It lives on in homeschooling, to an extent). In a world where schools are struggling to help every kid learn to read, the ethics of only assigning tutors to gifted students is dubious and almost certainly a political impossibility. The cost of assigning a tutor to every child, meanwhile, would do something special to property taxes. This simple answer, then, can lead to a clearer understanding of the complexity of educational questions: It’s possible to focus on simple practices that work while disregarding nonacademic concerns and political feasibility.

To be useful, educational ideas should be effective, politically feasible, and economical. If tutoring for gifted underachievers isn’t workable, might there be some other way to approximate the benefits of personal, human attention? Here are three of the most common tools that advocates for gifted education propose:

- Grouping students of the same age in classes according to their abilities, i.e. tracking (National Association for Gifted Children)

- Accelerating students through the curriculum according to their readiness, ignoring age or grade level (A Nation Deceived)

- Using personalization software to replace a human tutor (How Khan Academy Will Help Find The Next Einstein)

What follows is an evaluation of how promising each of these tools is, both in theory and in practice.

Our favorite one-stop reading on gifted education research: this.

Our favorite one-stop reading on tutoring: this.

2. Ability Grouping (a.k.a Tracking)

The case for placing students of similar abilities together in a classroom seems like it ought to be as simple as the case for tutoring. Teachers will be more effective if their students have similar pacing needs. So, group kids who need more time in one class and those who need less time in another. It’s not tutoring, but it should be the next best thing.

Things in education research are rarely that simple, though.

Bob Slavin, a psychologist who studies education, is one of the most-cited education researchers around. He seems like a compulsively busy fellow. He writes, he runs research centers, he designs programs for schools. (He blogs.) A journalist from The Guardian once asked Slavin for his likes and dislikes, and in case you were wondering he likes work and dislikes complacency.

In the late ’80s and early ’90s, Slavin performed a series of meta-analyses of the existing literature on tracking and between-class ability grouping. Overall, he found no significant benefits from ability grouping, even for “top track” students across elementary, middle, and high schools.

But the other surprising finding of Slavin’s was that nobody was academically hurt by ability grouping — not even the lowest track students. Slavin argued that when you consider all the non-academic concerns, the scales weigh in favor of detracking, i.e. avoiding ability grouping.

What are those non-academic concerns? In the conclusion of his review of the evidence from elementary schools, he writes:

“Ability grouping plans in all forms are repugnant to many educators, who feel uncomfortable making decisions about elementary-aged students that could have long-term effects on their self-esteem and life chances. In desegregated schools, the possibility that ability grouping may create racially identifiable groups or classes is of great concern.” (p.327)

That’s Slavin’s view. So, where is the debate?

One thing that is decidedly not up for debate in the literature is that Slavin’s non-academic concerns are real. Opponents and defenders of tracking alike agree that low-track classes are often chaotic, poorly taught environments where bad behavior is endemic, and that this is a major problem. Tom Loveless is a contemporary defender of tracking, and writes that “even under the best of conditions, low tracks are difficult classrooms. The low tracks that focus on academics often try to remediate through dull, repetitious seatwork.” Jeannie Oakes made a name for herself by carefully documenting the lousiness of a lot of low track classes.

Some tracked schools seem to have done better with their low tracks. Gamoran, an opponent of tracking, speaks highly of how some Catholic schools handle lower tracks. Gutierrez identifies several tracked schools with strong commitments to helping students across the school advance in mathematics, and concludes that “tracking is not the pivotal policy on which student advancement in mathematics depends.” Making these experiences better is an important goal. These difficult dynamics are a genuine and widespread issue, though, and educators are rightly concerned about them.

Slavin’s concerns about exacerbating racism in schools are relatively uncontroversial as well. It’s not so much that race is a factor in track placement. Using a large nationally representative sample and controlling for prior achievement, Lucas and Gamoran found that race wasn’t a factor in track placement. (Though Dauber et al, found that race was a factor in track placement in Baltimore schools, so maybe sometimes racism is a factor in placement.)

But because of existing achievement gaps between e.g. Black and white students, there’s the potential in a racially mixed school that ability groups will effectively sort Black students into the lowest track and expose them to a lot of dynamics that are difficult to quantitatively measure but frequently discussed in education. A school where being Black is associated with poor performance and misbehavior will, according to many educators and researchers, lead to lower expectations and academic self-esteem for all Black students.

(Good news for people who like bad news: school segregation is getting worse, so the interaction between tracking and race is getting better.)

The main controversy surrounds Slavin’s claims about the academic impact of ability grouping. His meta-analyses were part of an extended back-and-forth with Chen-Lin & James Kulik, who wrote several competing analyses on the ability grouping literature. Slavin and the Kuliks each criticized the other’s methodology, but the core point the Kuliks made was that ability grouping did have positive effects on gifted students as long as curriculum was enhanced or accelerated to match, and that this typically did happen in dedicated gifted and talented programs. The Kuliks pointed out that both they and Slavin largely agreed on the data both analyzed, but that Slavin excluded studies of gifted programs from his research while the Kuliks made those studies a focus.

Tom Loveless, senior fellow at the Brookings Institution, summarized one important aspect of their dispute, which is that their debate centers more on values than their read of the extant evidence:

Slavin and Kulik are more sharply opposed on the tracking issue than their other points of agreement would imply. Slavin states that he is philosophically opposed to tracking, regarding it as inegalitarian and anti-democratic. Unless schools can demonstrate that tracking helps someone, Slavin reasons, they should quit using it. Kulik’s position is that since tracking benefits high achieving students and harms no one, its abolition would be a mistake (p.17)

Betts notes the studies the Kuliks and Slavin reviewed in their meta-analyses had some flaws, with relatively small N and non–nationally representative data. Using more nationally representative samples, a number of researchers (Hoffer, Gamoran and Mare, Argys, Rees and Brewer) came to the conclusion that conventional tracking benefits students in the high tracks and hurts those in the low tracks. But it’s really hard to control for the right factors in these definitely non-experimental studies, and Betts and Shkolnik raise questions about the results of these papers. And there was also a recent big meta-meta-analysis that found no benefits for between-class grouping, echoing Slavin, but that did find benefits for special grouping for gifted students, echoing the Kuliks.

Just to mess with everybody, Figlio and Page argue that by attracting stronger students to the school (because parents seek tracking) students in low-tracks benefit, secondarily.

So, in summary, what should we make of all this? Betts, an economist, says in a review of the literature that when it comes to the average impact of tracking or the distribution of achievement “this literature does not provide compelling evidence.” Loveless doesn’t disagree, but notes that for high achievers, the situation is clearer:

“The evidence does not support the charge that tracking is inherently harmful, and there is no clear evidence that abandoning tracking for heterogeneously grouped classes would provide a better education for any student. This being said, tracking’s ardent defenders cannot call on a wealth of research to support their position either. The evidence does not support the claim that tracking benefits most students or that heterogeneous grouping depresses achievement. High achieving students are the exception. For them, tracked classes with an accelerated or enriched curriculum are superior to heterogeneously grouped classes.” (p.22)

At the end of the day, all academic impacts of tracking are mediated by teaching and the curriculum. If a teacher doesn’t change what they teach or how they teach it, no grouping decision will help or hurt a student academically in a significant way. Tracking only could benefit gifted students if it came with some sort of curricular modification.

This is a conclusion with wide-reaching support. Even Slavin, who so staunchly opposed conventional ability grouping, was extremely impressed by something called the Joplin Plan, which involves three core features:

- Grouping students based on reading ability, regardless of grade level

- Regular testing and regrouping of students on the basis of the tests

- A different curriculum for each group of students

Slavin, the Kuliks, and everyone else seemed to agree that students in the plan — at all ability levels — tended to get 2-3 months ahead of students in typical programs over a year of instruction. The Joplin plan involves ability grouping — the good kind of ability grouping.

So in 1986, when the Baltimore School Superintendent turned to Bob Slavin to design a program that would improve the city’s most dysfunctional schools, guess how Slavin grouped students?

Slavin worked with research scientist Nancy Madden (they’re married) to design Success for All for Baltimore, and it’s a prominent program in the school improvement world, implemented in thousands of schools and spreading. Those three features of the Joplin plan — assessment, regrouping along the lines of ability and targeted teaching — are core features of their program.

Success for All isn’t the only example of a successful curriculum implementing these ideas. Direct Instruction was created by Siegfried Engelmann and Wesley Becker in the 1960s, and it also groups students according to their current levels in reading and math while frequently reassessing and regrouping. DI has a strong body of research supporting its efficacy (for one, it was the winner of the famous-in-education Follow Through experiment), but fell largely out of favor outside of remedial classrooms. In early 2018, a new meta-analysis spanning 50 years of research reinvigorated conversation around Direct Instruction. It found an average effect size of 0.51 to 0.66 in English and math over 328 studies (p<0.001), — strong evidence that the program works.

While its effect on student performance is rarely disputed, the program remains controversial. Historian of education Jack Schneider writes: “Direct Instruction works, and I’d never send my kids to a school that uses it. The program narrows the aims of education and leaves little room for creativity, spontaneity and play in the classroom. Although test scores may go up, the improvement is not without a cost.” Ed Realist worries that its pedagogy is unsavory, has not been shown to work for older students, that wealthier parents are voting with their feet against the curriculum, and that DI could exacerbate gaps between students. Supporters, by contrast, paint the picture of a robust, effective system that has been ignored and disregarded.

Success for All and Direct Instruction are not simple programs for schools to adopt. Implementing them amounts to a major organizational change, and pushes at the extremely resilient notion that children in school should be grouped by their ages. Comprehensive ability grouping programs such as these seem to work, but in practice they are rarely used.

Our favorite one-stop source for reading on ability grouping: here, or maybe here to get a broader picture of the controversy.

3. Acceleration

Forget the comprehensive approach, then. Does it work to simply move an individual student (e.g. an underchallenged and frustrated student) through the curriculum at whatever pace seems to make sense?

There are a few different ways schools can help some students access the curriculum more quickly. A kid can skip a full grade, or several grades in extreme cases. They can stay in their grade for some classes, but join higher grade levels for some parts of the day. They might be assigned to two classes in one year (e.g. Algebra 1 and Geometry). Or, in some cases, a young student might start school at an even younger age than is typical.

If a child is ready for a higher level within a subject and studies it instead of the lower level, it’s almost a given that they’ll learn more. The real research questions are (a) from an academic standpoint whether accelerated children do tend to be ready, or if they do poorly in classes post-acceleration) and (b) whether acceleration exposes students to non-academic harm (e.g. stress, demotivation, loss of love for subject, poor self-esteem).

The Study of Mathematically Precocious Youth (SMPY) is an ongoing longitudinal study examining thousands of mathematically gifted students. In one SMPY study, researchers compared the professional STEM accomplishments of mathematically gifted students who skipped a grade to those who remained at grade level. They found that, controlling for a student’s academic profile in a pretty sophisticated way, students who skipped a grade tended to be ahead of the non-skippers in terms of degrees earned, publications, citations accrued, and patents received. From this work it seems skipping a grade in the SMPY cohort did nothing to hurt a kid’s learning or enthusiasm for their passions.

Acceleration has been one of the focuses of SMPY studies. A 1993 piece about SMPY findings reported “there is no evidence that acceleration harms willing students either academically or psychosocially.” This is supported by various meta-analyses, going back to the 1984 Kulik & Kulik paper and confirmed by more recent work such as a 2011 analysis of existing studies. Beyond the “does no harm” findings, these meta-analyses also report academic benefits to students.

It can be confusing, when reading these studies, to keep track of just how gifted the students happen to be. For example, SMPY has studied five cohorts so far, ranging from students who assessed in the top 3% to those who assessed in the top 0.01%. As we consider students farther away from the mean of achievement, the need for acceleration becomes more acute.

Lots of teachers encounter “1 in 100” students every year, but the education of “off the charts” students is necessarily more a matter of feel than policy. Still, there are success stories to learn from, and they show a remarkable sensitivity to both the academic and social well-being of the student.

Terence Tao is a famous success story of this kind. He surprised his parents by discovering how to read before turning two, and as a child he started climbing through math at a blistering rate. He was identified as profoundly gifted from a young age, and his education was carefully tracked by Miraca Gross as part of her longitudinal study of profoundly gifted children:

His parents investigated a number of local schools, seeking one with a principal who would have the necessary flexibility and open-mindedness to accept Terry within the program structure they had in mind. …

This set the pattern for the ‘integrated,’ multi-grade acceleration program which his parents had envisaged and which was adopted, after much thought and discussion, by the school. By early 1982, when Terry was 6 years 6 months old, he was attending grades 3, 4, 6 and 7 for different subjects. On his way through school, he was able to work and socialize with children at each grade level and, because he was progressing at his own pace in each subject, without formal “grade-skipping,” gaps in his subject knowledge were avoided.“

His education continued in much the same fashion, culminating in a Ph.D. by the age of 21 and a remarkable and balanced life since. He has since given his own advice on gifted education.

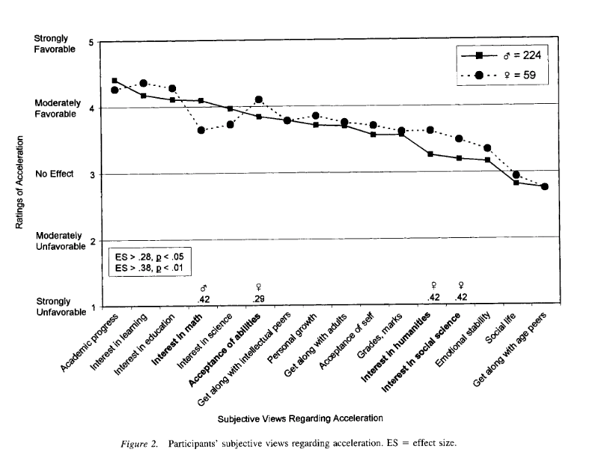

Given the success of acceleration, are we accelerating enough? On the one hand, it appears that acceleration is a widely used tool for giving gifted students what they need. When looking at the top 1 in 10000 students in terms of mathematical ability as identified by the SMPY, nearly half of the group skipped grades, and almost all of them had some form of acceleration, whether that meant advanced classes, early college placement, or other tools. About two-thirds reported being satisfied with their acceleration, rating it favorably across many categories:

The dissatisfied third of those 1 in 10000 students, for the most part, reported wishing they had been offered more acceleration. And advocates for gifted education strongly endorse the notion that acceleration is under-used. A Nation Deceived is premised on this idea — though besides for “more” the report doesn’t get specific concerning how many students ought to be accelerated, and the report mostly makes a cultural argument in favor of acceleration, citing stories like Martin Luther King Jr. graduating high school at 15.

We wanted to know more about how educators think about acceleration, so we surveyed (via twitter) twenty-one teachers, academic coaches, tutors and administrators. The survey prompted educators to respond to the following scenario:

In your school there is currently a 1st Grader who does math above grade level, e.g. he performs long division in his head. His parents initiated contact with the teacher after hearing their child complain that math at school was boring. They’re concerned that he isn’t being challenged. The classroom teacher knows that he is above grade-level in math, and is trying to meet his needs in class. The parents, however, do not think the current situation is working. The teacher reports that the student is difficult to engage during math class, and that sometimes he misbehaves during math.

From their responses, it certainly seems that acceleration was on the table, but almost always the last option after a number of in-class or non-classroom options (e.g. after school clubs) were explored. That acceleration in math should be a “break in case of emergency” response is also the line offered by the National Council of Teachers in Math: tracking is morally indefensible, acceleration should be viewed with suspicion but can sometimes be appropriate.

In many ways, mainstream education is living in Bob Slavin’s world. He was a leading opponent of tracking, but was impressed by certain forms of ability grouping. He took the research on ability grouping that actually works (through assessment, frequent regrouping, and curricular modification) and used it to create a program for failing schools. He expresses suspicion about acceleration of gifted students in general, but agrees that at times it is a useful and necessary tool. If you broach the conversation about acceleration with your child’s teachers, you might hear some version of Bob Slavin’s take.

There is more to say about where this skepticism comes from. But it’s important to note that just because a student could be accelerated doesn’t always mean that they should. While some gifted students fit the profile we sketched above — frustrated with school, bored and underchallenged, and finding it hard to connect to peers — many equally capable students are happy in their school lives. (We heard some, but not many, happy stories from online commenters.) If a child is happy and successful without acceleration, they are likely to remain happy and successful regardless of whether they are accelerated, and if they don’t want to accelerate, it should not be forced on them. At least some of the suspicion towards acceleration comes from parents who inappropriately push schools to accelerate their happy, satisfied children.

Acceleration is also not the only option. There is much more to learn than is taught in regular courses. Even in a normal class, a well-designed curriculum or an experienced teacher can create “extensions” to the main activity, so that students who are ready for more have something valuable to engage with. Enhancement or exposure to new, similar topics can serve students as well. A student who has jumped ahead in arithmetic may be entranced by a glance at Pascal’s triangle and number theory. One who is fascinated by English might find similar joy in learning Spanish or Chinese. Both of these, alongside acceleration, follow a simple principle: if a child wants to learn more and is able to do so, let them learn more. Overall, the balance of evidence suggests that acceleration is a practical and resource-effective way to help gifted, underchallenged students flourish in schools.

Our favorite one-stop source for reading on acceleration: here.

4. Educational Goals in Conflict

Through acceleration, tutoring, or ability grouping, some kids could learn more. Why aren’t schools aggressively pursuing that? Shouldn’t they be working to teach kids as much as possible? Isn’t that what a school supposed to do? That educators are skeptical of ability grouping or acceleration can be maddening from the perspective of learning maximization: Why are schools leaving learning on the table?

Here’s something we don’t talk about nearly enough: schools are simply not in the learning-maximization business. It turns out that parents, taxpayers and politicians call on schools to perform many jobs. At times, there are trade-offs between the educational goals schools are asked to pursue, and educators are forced to make tough choices.

Historian David Labaree has one way of thinking about these conflicting educational goals, which he expands on at length in Someone Has to Fail. For Labaree, there are three competing educational goals that are responsible for creating system-wide tensions:

- democratic equality (“education as a mechanism for producing capable citizens”)

- social efficiency (“education as a mechanism for developing productive workers”)

- social mobility (“education as a way for individuals to reinforce or improve their social position”)

As Labaree tells it, these goals end up in tension all the time. A lot of things that seem like gross ineptitude or organizational dysfunction are really the result of the mutual exclusivity of these goals:

These educational goals represent the contradictions embedded in any liberal democracy, contradictions that cannot be resolved without removing either the society’s liberalism or its democracy … We ask it to promote social equality, but we want it to do so in a way that doesn’t threaten individual liberty or private interests. We ask it to promote individual opportunity, but we want it to do so in a way that doesn’t threaten the integrity of the nation or the inefficiency of the economy. As a result, the educational system is an abject failure in achieving any one of its primary social goals … The apparent dysfunctional outcomes of the school system, therefore, are not necessarily the result of bad planning, bad administration, or bad teaching; they are an expression of the contradictions in the liberal democratic mind.

Ability grouping and acceleration fit nicely within the tensions Labaree exposes. These learning-maximizing approaches could find support from those who see education as a national investment in our defense or economy. Of course, the strongest demand for acceleration in schools can come from parents, who want schools to give their children every possible opportunity to be upwardly mobile. (“We want to make sure they can go to a good college.”)

Those act as forces in favor of ability grouping and acceleration. But schools also know that they are held responsible for producing equitable outcomes for a citizenry that sees each other as equals. A program that raises achievement for top students without harming others has an appeal an economist could love, but within schools this can count as a problem.

The way this plays out in practice is that many schools are inundated with requests to accelerate a kid. Parents — especially financially well-off, well-connected parents — can typically find ways to apply pressure to schools in hopes of helping their children reach some level of distinction. They’ll sometimes do this even when it wouldn’t benefit a child’s education (it would be educationally inefficient), or when it would exacerbate inequality (by e.g. letting anyone with a rich, pushy parent take Algebra 1 early).

In short, from a school’s standpoint those are two problems with acceleration. First, parents will push for it even when it’s not academically or socially appropriate. Second, it can exacerbate inequalities. That could explain where the culture of skepticism within education comes from.

This is meant entirely in terms of explaining the dynamic. The way this plays out can be incredibly painful. Systems designed to moderate parental demand can keep a kid in a depressing and frustrating situation:

My older son wanted to move up to a more advanced math course for next year. He took two final exams for next year’s course in February and answered all but 1/2 of one question on each. So roughly 90% on both and his request to skip the course was denied. (source)

Districts sometimes have extensive policies that can be incredibly painful to navigate when trying to get a student who truly needs acceleration out of a bad classroom situation. We heard from one educator who had a very young student expressing suicidal ideations. It was all getting exacerbated by the classroom situation — the kid said he felt his teachers and peers hated him because he loved math. The parents and the educator tried to find a better classroom for the child, and were met with all the Labaree-ian layers of resistance. Off the record, the educator advised the parents to get out of dodge and into a local private school that would be more responsive to his needs.

A happy ending: the 4th Grader moved to a private school where he was placed in an 8th Grade Honors class. He likes math class now. He seems happier, he’s growing interested in street art and social justice work.

But without a doubt, there are some unhappy endings out there.

5. Personalization Software

“Ours is an age of science fiction,” Bryan Caplan writes in The Case Against Education. “Almost everyone in rich countries — and about half of the earth’s population — can access machines that answer virtually any question and teach virtually any subject … The Internet provides not just stream-of-consciousness enlightenment, but outstanding formal coursework.”

The dream of using the Internet to replace brick-and-mortar classrooms is a dream that is entirely in sync with the times. This is reflected in the enormous enthusiasm directed towards online learning and personalization software. Bill Gates, Elon Musk, and Mark Zuckerberg have all invested heavily in personalization and teaching software. And the industry as a whole is flush with funding, raising some 8 billion dollars of venture capital in 2017, while reaching 17.7 billion in revenue.

Finally — a way out of the school system and its knot of compromises! If schools are institutions whose goals are in tension with learning-maximization… then let’s stay away from schools and their tensions and give the children the unfettered learning they want. Let’s create the ideal tutor as a piece of software.

This dream isn’t just in sync with our times — it has a long history. This history is particularly well-documented by historian Larry Cuban (author of Teachers and Machines and Tinkering Toward Utopia) and by Audrey Watters (she’s writing a book about it). Watters’ talk “The History of The Future of Education” is as good a representative as any of the major thesis: that the dream is larger than any particular piece of technology. Motion pictures, radio, television, each of these was at times promoted as an educational innovation, able one day to free students from lockstep movement through school and into a personalized education. From Thomas Edison to B.F. Skinner, tech advocates have long envisioned the future that (at least according to Caplan) we’re living in now.

Then again, tech advocates in the past also thought they were living in the age of personalized learning. In 1965, a classroom that used a program called Individually Prescribed Instruction was described this way:

Each pupil sets his own pace. He is listening to records and completing workbooks. When he has completed a unit of work, he is tested, the test is corrected immediately, and if he gets a grade of 85% or better he moves on. If not, the teacher offers a series of alternative activities to correct the weakness, including individual tutoring.

For comparison, here is the NYTimes in 2017, and the headline is A New Kind of Classroom:

Students work at their own pace through worksheets, online lessons and in small group discussions with teachers. They get frequent updates on skills they have learned and those they need to acquire.

The similarity between modern day and historical personalization rhetoric doesn’t settle the matter — in a lot of ways, clearly the Internet is different — but personalization software seems to have arrived at a lot of familiar, very human frustrations.

Anyone who has gone online to learn has, at some point, come face to face with this dilemma: On the internet, you can study almost all human knowledge, but usually you don’t. In a world with virtually every MIT course fully online for free, a world with Khan Academy and Coursera and countless other tools to aid learning, why has the heralded learning revolution not yet arrived?

In a way, the revolution has arrived — it just hasn’t improved things much. Rocketship Schools, a California charter using online learning for about half of its instruction, has had solid results. Lately, though, they’ve moved away from some of their bigger bets on personalization and rediscovered teachers, saying “We’ve seen success with models that get online learning into classrooms where the best teachers are.” School of One was a widely hyped high school model in NYC that was preparing to scale up its offerings… until a fuller picture of the results came in and it was pilloried. Online charter schools, meanwhile, seem to actively depress learning.

Part of the problem is that it’s hard to get solid research on the efficacy of various ed tech products. Many tools, particularly those sold directly to schools or used by online charters, are proprietary and stuck behind paywalls, selectively presenting their best data and limited demos. The ed tech sector in general seems to deliver mixed results to students.

Why is it so hard to make effective teaching software?

For one, teaching is complex. A good human teacher does a lot of complicated things — gets to know their students, responds to the class’ moods and needs, asks “just right” questions, monitors progress, clarifies in real time as a look of confusion dawns on the class, etc., etc. — and it’s simply hard to get a computer to do that.

Maybe, theoretically, a piece of software could be designed that does these things. But in practice, many software designers don’t even try. It’s easier and cheaper to make pedagogical compromises, such as providing instruction entirely through videos. Yes, there are some thoughtful tools made by groups like those at Explorable Explanations, such as this lesson on the Prisoner’s Dilemma. But building high-quality tools well-adapted for a digital environment is difficult and time-consuming, and for prospective designers, destinations like Google or Blizzard tend to be more glamorous than working with schools. In practice, humans currently have a lot of advantages over computers in teaching.

Even if we overcame all the design issues, though, would students be motivated to stick with the program? Studies of online charters point to student engagement as the core challenge. When you put a kid in front of a computer screen, they jump to game websites, YouTube, SlateStarCodex, Google Images — anything other than their assigned learning. Many educational games that try to fix this resort to the “chocolate covered broccoli” tactic, trying to put gamelike mechanics that have nothing to do with learning around increasingly elaborate worksheets.

To be fair, student engagement is also the core challenge of conventional schools. But that’s precisely what the much-maligned structures of school are attempting to confront. The intensely social environment helps children identify as students and internalize a set of social expectations that are supportive of learning. The law compels school attendance, and schools compel class attendance. .And, once a child is in the classroom, their interactions with actual, live human instructors can set high academic expectations that a child will genuinely strive to meet.

The conventional story is that school is incredibly demotivating, but compared to their online counterparts schools are shockingly good at motivation. MOOCs like those on Coursera have an average completion rate of 15 percent — public schools do much better than this. Popular language app Duolingo’s self-reported numbers from 2013 would put their language completion rate at somewhere around 1%. If all a user has to rely on is their daily whim to continue a course, the most focused and conscientious may succeed, but those are the ones who already do well in schools. That’s a big part of why people lock themselves into multi-year commitments full of careful carrots and sticks to get through the learning process. Writers such as Caplan think that people are revealing their true interests when they skip learning to fart around on the web, but we might as well see a commitment to attend school as equally revealing. People need social institutions to help do things we’d truly like to do. As such, even as computers become better teachers, the motivational advantage of schools seems likely to persist.

How might tech-based learning tools address these factors, so they might stand a chance at holding students’ attention long enough to teach them? Art of Problem Solving, an organization promoting advanced math opportunities to children, makes a good case study. It’s found a balance worth examining. First, it provides accessible gamelike online tools that center on a careful sequence of thought-provoking problems. Second, it offers scheduled online classes with the promise of a fast pace, challenging content, and a peer group of similarly passionate students taught by subject matter experts. The online classes are more expensive offerings, but they preserve the human touch.

What does that balance mean for students? If they’re in the conscientious, self-motivated crowd that wants to learn everything yesterday, they can gorge themselves on software designed to be compelling. No barriers keep them from progressing. Software can always point to a next step, a harder problem. On the other hand, if they want to lock a motivational structure around themselves and keep the social benefits of school in a more challenging setting, they can.

Not every successful tool need look identical, but that core idea is worth repeating: software should enable the passion and self-pacing of eager kids, but should not rely on that to replace the power of social, human motivational structures. Yes, sometimes even the same structures used in “regular” schools.

Online learning, then, fits squarely within the history of attempts to automate teaching. Over and again we make the same mistakes and forget the lessons of history: that teaching is more complex than our machines have ever been, that motivation is largely social, and that schools will have a hard time distinguishing between altrustic designers and opportunistic profit-seekers.

For those in the market for online learning there are a lot of mediocre tools available, and many truly bad ones. Right now, there’s nothing that seems ready to serve as a full-on replacement for school without consistent, careful human guidance.

That said, depending on your passions, there are some excellent resources for learning out there. Especially if a student has a caring mentor or a passionate peer group, they can learn a lot online. As educators and designers create more tools that respect both the power and limitations of machines, that potential can grow. But it’s not quite science fiction.

Our algorithm has determined that you should watch the following two videos: here and here to balance realism and idealism

6. Practical Advice

Education is complex and resists easy generalizations. That said, here are some generalizations.

On navigating school for your child:

- The brightest students do not thrive equally in every setting. Even the best students achieve more with teachers than on their own. Unless tutoring or some other private arrangement is possible, this means that a school is the best place to be for learning.

- But school right now doesn’t work for all kids. One fix: if a child wants to be accelerated and seems academically prepared for it, acceleration will usually help them.

- Most schools aren’t in the business of maximizing learning for every student, and in particular they tend to be skeptical of acceleration.

- Therefore: If your kid needs more than what school is offering, be prepared to be a nudge.

- But if you think your kid needs to be challenged more and your kid is perfectly happy in school, try really hard not to be a nudge.

- Don’t fight to move your child to a class that covers the exact same material at the exact same pace but has the word “Honors” next to it. That sort of ability grouping makes no educational difference.

- Prioritize free, open online tools. Don’t expect online tools to do the work for you or your child. Expect more distraction and less progress if online learning time is unstructured or unsupervised.

For educators:

- If you are an elementary teacher or administrator and your school is looking to try new things, consider cross-grade ability grouping by subject, especially in math and reading.

- Gifted kids are usually not equally talented in all fields. Consider options to accelerate to different levels in each subject based on demonstrated skill in that subject.

- A lot comes easily to smart kids, and sometimes they never get the chance to learn to struggle. Find something they think is hard, academic or not, so they are able to handle more important challenges later.

- If a child is bored in your class and knows the material, they probably shouldn’t be in your class.

For tech designers and users:

- If you’re making online tools, make the learning the most interesting part of them. Don’t rely on chocolate-covered broccoli or assume that just presenting the material is enough. Take the problem of motivation seriously.

- Look for passionate groups with robust communities, whether online or offline. Don’t overlook the social aspect of learning.

And for advocates of educational reform, in general:

- People almost only talk about educational efficacy. But don’t be fooled — educational debates are only sometimes about what works, and frequently about what we value.

One last thing: if you’re an educator or a parent or just somebody who spends time around children, take their feelings seriously, OK? If a kid is miserable, that’s absolutely a problem that has to be solved, no matter what district policy happens to be.

Acknowledgments: Thanks to /u/Reddit4Play from reddit, JohnBuridan from the SSC community, blogger Education Realist, and many others who read drafts and offered ideas along the way.

Excellent work. (And by that I sadly mean it confirms more or less all of my priors as a reasonably long time high school teacher and graduate student in educational matters as well as documents them with references.)

If I would offer one suggestion for an even better writeup, it would be to move the part about what percentage of the children the whole thing is about to the beginning and maybe try to expand it a little. As a teacher and educator, there is enormous difference between policy for handling 2 sd+ and 4 sd+ children.

Since the final writeup seem so conventional to me I would like to direct a question to tracingwoodgrains.

What have been your experience of the process?

Glad you enjoyed it, and that it read as accurate to you!

We wrestled a lot with what percentage of children to focus on, and that’s one reason it ended up under-emphasized. It’s surprisingly hard to nail down the number of children who end up frustrated and slowed down in school, particularly since most of the research around “gifted underachievement” focuses on non-school factors, and only a few researchers (Gross, SMPY) usually bother dividing “gifted” kids into more precise categories and hunting down 3+ or 4+ SD kids. You’re right, the policy difference for handling the two groups is huge.

As for my experience with the process, my first impression is that it was long. We have a 150-page pile of background notes and side conversations. Finding a really good adversarial collaboration partner (which Michael was) creates a really cool environment: you’re both passionate about something, but you’re passionate about different views of it and see different parts as important, which means it only takes a comment or two to spawn pages of discussion and a dive through four or five more research papers.

A lot of this didn’t end up in the final paper, some due to relevance, some due to length, and some simply because we couldn’t reach a satisfying consensus. Even on what we did include, though, we noticed a compelling phenomenon: we would agree pretty much entirely on the object-level facts, but then take a step back and wrap them in dramatically diverging narratives. For me, generally speaking that meant a cynical view of traditional education and an optimistic view of alternatives; for Michael, the opposite. So once we started writing the paper there was a lot of, “So, we agree completely, right?” “Right!” “Great, I’ll just write this bit, then.” “Wait, no no no, you focused on all the wrong things! We need to go back and redo this completely.”

It was by far the most fruitful period of learning I’ve had in any context, to be honest. When someone’s questioning the core assumptions behind your views as you research, you end up diving pretty deep in all sorts of directions. Michael was really good about both questioning without attacking and providing useful research, and as a result I was pretty obsessive about the topic during the contest timeframe.

I wouldn’t say I’m in a rush to do it again. It was a lot of work. But it’s one of the most meaningful opportunities I’ve had, and I’m really grateful Michael spent so much time working with me on this. If there’s interest, I might do a more complete write-up of what the process looked like, with more topic-related specifics.

I’d be very interested in hearing about the process!

My current goal is to sit down within the next few days and write a more detailed post outlining where we started, particular areas of contention or compelling differences of perspective, and a few of the points we talked a lot about but never made it into the essay. Working to present things as a unified front was a fantastic exercise, but as several comments have pointed out, it makes it hard to notice the push and pull of opinions that led to those conclusions, and I expect that for all the collaborations, seeing what needed to happen to reach the endpoint would be a useful exercise.

If or when I make the post, I’ll likely end up tossing it on SSC’s companion subreddit and in one of the next Open Threads.

Wow, the other entries are going to have to be pretty damn impressive if this is what they’re competing against.

Has anybody used clustering algorithms to group classes? You could cluster students according to scores in subjects e.g. every month so that the curriculum could be dynamically adjusted to accommodate the maximum number reasonably possible.

Seconded. With such a small sample set I’m guessing this is an outlier (because the best writers or the most fruitful topic just happened to get ordered first), but I’m going to be utterly thrilled if it isn’t (because the adversarial collaboration format either attracts the best writers or facilitates or encourages the best writing on the most interesting topics). Even if that’s the case, adversarial collaboration may not be the Holy Grail of replicating rational writing, but it might still be a big improvement over the current “start a great blog, hope some of your audience is inspired to do the same, hope some of those succeed, repeat”.

I think you are misunderstanding the implications of this summary.

Over and over, we see see that the educators have a very important role or function. The function is properly responding to the overall needs of the students in their class. That requires being able to accurately assess those needs. And the needs don’t exist solely for each individual student, but the class as a whole.

Switching students every month will amount to a problem of “thrashing”, where every month teachers are spending time re-learning their classroom, instead of serving it.

I don’t think so. The clusters would probably be quite stable after a few months. But even then, fine, we could say check the clusters every three months. Or just once every year. It’s just that when I went to school kids spent several years with the same group of arbitrarily selected people in every subject, when those groups could have been selected in a so much more logical way.

I think one issue that our current system faces is that there is little pairing of teachers and students, as if teachers are practically fungible and that they don’t have their own preferences or abilities to teach certain students better.

IANAT (teacher) but I’ve known several. As far as I can tell, the overwhelming majority of teachers would prefer to teach the brighter kids. Throughout my entire educational experience from K-Masters, it seemed like the teachers with the most seniority were always given the top tracks, while the newbies had to “earn their stripes” teaching the remedial courses.

This may not be the most appropriate place for this so if it isn’t I’m fine with this being deleted.

But I was wondering, how does unschooling/Sudbury education fit in to all of this? Is there just too little research on it to seriously comment on it? The only even semi-serious research I’ve seen on it are the surveys conducted on graduates from the Sudbury School in Massachusetts, which suffers from limited sample size and author bias, among other things. Is or has there been any attempt to research it? Or do education scholars just not take it seriously? Is it just too radical?

I don’t think that it’s fringeness makes it ignored; I think it’s fringeness makes it highly variable. In my experience homeschoolers and unschoolers have vastly different outcomes depending on the same factors from the post: presence, or lack thereof, of guidance and attention, conscientiousness, compelling content. Furthermore, I am extremely skeptical of non-rich parents being able to provide an adequate high school education to a gifted child.

Imagine the set of all homeschoolers in America. Each homeschool/unschool can be lumped into different categories depending on the adults involved. As an educator at a college-model k-12 school, I deal with a lot of former homeschool/unschool parents. Sometimes they respond very well at getting their child the help and support they need, sometimes they do not, sometimes they cannot.

I’m not sure what you mean by rich/non rich but a handful of home schoolers I have talked to with gifted kids basically sent them to community college classes for more advanced (if not strictly better) instruction for a few hundred dollars a semester. I am also under the impression that gifted+interested students typically learn straight from textbooks/videos with parents doing fairly minimal interventions and encouragements.

I meant that even super homeschool parents have difficulty teaching beyong the 8th grade level, and so they need help which requires either some excess capital or a rich social network. Often homeschool parents form co-ops in which parents who are knowledgable/enthusiastic about certain subjects teach, and sometimes they hire an outside tutor to teach the classes they don’t have a teacher for. I know of four co-ops in my county. I’m sure there are many more than that. They pool resources are and are very cost-effective, while usually being academically nondemanding.

Many parents do not have money to spend on tutors or community college classes ($350 a class in my county + book fee + transport) to take care of an entire high school education.

(Furthermore, co-ops do not have longterm staying power, and usually fold in on themselves due to the diversity goals of adults involved, low investment, and easy exit.)

It’s possible, John Buridan, in at least some states for students to enroll part-time as homeschoolers and part-time in public school (see, e.g., here for Iowa). That also means that homeschoolers can take advantage of state-funded post-secondary education options to pursue more challenging coursework without paying tuition (though transportation might still be an issue). That’s not enough for a full day’s education, but it would certainly be enough to cover classes that are more intellectually demanding, expensive to do right (chemistry comes to mind), or simply outside the knowledge of the parent-teacher.

You might know all of this, but, as you don’t mention it, it seems an important qualifier to your comment. There are options for managing high school that do not put the whole burden of cost on either parents or the local school district. Furthermore, I wonder whether you underrate the ability of parents to teach. Surely any “super homeschooler” worthy of the name is going to have at least a Bachelor’s in some subject. Do you think that someone with a BA in History or English couldn’t tutor children in literature or American history (or perhaps: guide his/her children in studying) to at least the level reached in most high schools? I’ll grant, someone with a Master’s in the same field, a dynamic teaching style, and a highly engaged classroom could do substantially better, but how many children are going to find that?

Further, what do you mean by “rich social network?” If you mean that parents must have rich friends, I don’t think your explanation sustains the claim. If you mean, on the contrary, that parents must have a full and strong set of social connections in order to manage high school, I would guess that that is not uncommon among homeschoolers. Certainly the ones I knew when I was homeschooled seemed to, and the tendency to have 1) fairly strong religious ties, 2) mothers with the flexibility to “network” with others mothers during the day, and 3) a relatively small group of families involved (few enough, in the highly educated, smallish city I know best that every homeschooling family could at least be aware of the rest) would tend to suggest that such connections are common more generally.

Of course, high school is more complicated than earlier grades, and I think I agree that most parents are unlikely to handle it as well. I would guess that most of the homeschoolers I knew growing up either went to high school full-time at some point or took classes in high school/through PSEO; a few went to college early. But it certainly was not obviously a pragmatic necessity either to be wealthy or to stop homeschooling at ninth grade.

All good points, Philipp. It’s true that some states allow that. Mine doesn’t nor does the state I border, so I didn’t think to mention it. I believe Indiana one such state that does.

I do not mean to underrate parents’ ability to teach. I see it all the time. Parents require a “socially rich network,” when there is not a shared public school option. My claim is that no parent has the expertise needed to teach every high school subject. A socially rich network is just a group of friends who have expertise which you don’t have and time to help teach the things you don’t know as well.

From what I can tell being able to call on someone you trust who can teach or tutor the subject you as a parent are not comfortable with is necessary for successful homeschooling for a family through the years.

These issues also mean it is easy to start a co-op, especially if you just have some short term needs that you want filled. Beyond that just family and friends can help out a large amount. In high school I lived with my mother’s first cousin who taught french in a Canadian high school for 2 weeks to try to catch me up in a subject I didn’t have much affinity for, and took an advanced biology course at a local university one summer (I was not home schooled) and a few years ago my wife’s aunt and uncle took in one of her home schooled cousins for 3 months to give her a year’s worth of calculus.

The point here is not that everyone has the right support structure to do all of these things, but that many people probably do or at least could if they put effort into building them. The number of people who are some combination of poor or isolated enough, unable to master the subject matter themselves with the aid of books and the internet and with no friends, relatives or co-ops to turn to who end up with a 3+ sigma child is going to be fairly low.

Aren’t you making a major assumption that all gifted children have the same learning style there? Not all children learn in the same way, and I’ve seen no reason to think learning style is correlated to gifted (I used to work in school administration including setting up applied systems for recording progress).

I’m not, as it isn’t an exhaustive list of ways to teach intelligent kids, its just two examples to help define the issue. If you start with the supposition that only the ‘rich’ can afford to pay for decent instruction for talented high school age students then it helps to define what ‘rich’ is. If that means being able to pay $3-400 a class per semester and provide transportation then you are talking about the top portion of what is generally considered lower class income* and up being able to afford 1+ classes a semester. That leaves maybe 15-20% of the population for whom it is genuinely out reach for, meaning the scope of the issue is far less than was implied by the post I was responding to.

*some areas are low population enough that the transportation would be more onerous but (by definition) relatively few people live in these areas.

My 13 years-old son is being homeschooled (a classmate trying to stab him was the final straw), and has just started attending a Spanish class at Berkeley City College.

Judging by my own experiences in the Berkeley, California public schools in the 1970’s and ’80’s, my two “academic” classes (Cultural Anthropology and European history), and my “vocational’ classes (welding) at “community colleges”, and my time as an indentured apprentice plumber, as well as what I know of my little brothers education (with financial support from his family, including me, and his in-laws he graduated from San Francisco State and now has a white collar job with the State of Maryland) Junior High school should be eliminated, and High School should end no latter than age 16.

Too much time is wasted, and youths could be better educated elsewhere.

We actually looked quite a bit at unschooling and Sudbury education during the process! You’re right that a lack of serious research makes it difficult to comment on directly, but a lot can be done by looking at the research comparing direct and exploratory education methods. In almost every study we looked at that compared the two, direct methods beat exploratory ones (the sort unschooling and Sudbury schools endorse) out on every measure of learning. This includes critical thinking processes and adapting knowledge for meaningful use, two points often raised in favor of exploratory learning.

If your priority is academic learning, or building skills in general, unschooling is the wrong way to go. The motivation problems we mentioned with online school are fully in force when a child is in charge of their own learning, and it’s honestly really valuable to have a structure around you pushing and obligating you to study even topics you’re interested in. Since those are my priorities when it comes to education, I would personally put my children in virtually any other system before turning to a Sudbury-style one. I think it’s great that people keep experimenting with new and unusual systems, though. An ideal school would likely combine the high points of the ethos behind Sudbury schools (inspiring passion in students, focusing on the child’s natural aptitudes and interests) with a structure more suited to learning and gaining skill.

Thanks for the response! I’d be interested to see some more cites on the advantage of direct over exploratory education. Are there some with longer observation periods such as years or decades, instead of weeks (such as this one arguing against direct instruction). A lot of the effects that I see Sudbury/unschooling advocates point to are fuzzy “life skills” like motivation, time management, cooperation, and conflict resolution, the latter two particularly in Sudbury schools. Reportedly these only become evident over the course of years, due to the deschooling effect.

I think you’re right in terms of solid evidence it’s not the best choice that if you’re looking for academic learning. The argument that advocates give, though, seems to be that this kind of education builds those life skills which then enable people to do self directed learning effectively- in order to, e.g., do online learning, seek tutors, go through college. I’d personally give my kids the choice of what school they want to go to. I do wish there were more data – or even anecdotes – about kids who did Sudbury/unschooling and switched to another method or had negative experiences, and those who come from disadvantaged backgrounds. I also wish there was more info on how Sudbury/unschooling “grads” do compared to their socioeconomic peers. But if wishes were fishes, I’d be running a sushi bar 😉

The comparison with unschooling demonstrates that ordinary education doesn’t do anything. Thus it is not surprising that tracking doesn’t do anything differently. The surprising result is that unschooling doesn’t do anything, either. Not surprising is that the authors write:

and yet continue to write about the system as if it were an education system.

Yeah, that surprised me. I went to a tracked middle and high school system, and the courses were different between the tracks. The idea that someone would do tracking with the same material in each track, and expect useful results… my mind boggles. I guess the idea is it’s easier to teach students of similar ability together, but I’m unsurprised it doesn’t change things for the advanced students. I’d expect the only improvement (if any) to be in the middle (by removing potentially disruptive students and students who are a drag on the class)

My guess is that they mean within-class pacing, as well.

For example, if a gifted student goes to a class for the next grade up, the teacher is still teaching to pace with the worst student. Despite the material being a grade up, it’s likely that the gifted student will still be unchallenged.

To teach to the pace of ability means covering way more material in the same amount of time. Like the difference between 101 classes at MIT vs. a community college.

An Honors class for 9th grade Physics should not be the exact same curriculum as the non-Honors 10th grade Physics class, it should cover more.

(Or, AP classes should be worth more than one college credit if paced correctly, not just equivalence, since the former assumes a higher ability grouping than the latter.)

You want Honors to be y=z*mx, not y=mx+b.

I understand the article to say that acceleration, while not perfect, often works well. Are you disputing that?

I’m addressing the quote that Douglas Knight made, of cases where “tracking” was used, but were not really tracking. The argument is that those particular execution details weren’t really acceleration, as the rate of learning was still the same. Therefore, it is important to make sure that tracking differs in the rate of learning to match the group ability.

Here’s a related point whose correctness I’m not too sure of but I thought it was interesting and it’s not mentioned here — Andrei Toom, in his long explanation of how Russia does math instruction better than America, makes (somewhere in there; I’m going by memory, I’m afraid) the point that America’s idea of acceleration isn’t that great, because instead of going on from an easier version of a subject to a harder version, it just gets you from the easy version of one subject to the easy version of a different, later subject. Better than nothing, but still not really the right thing.

Later subjects, at least in math, at later because they build on earlier subjects, but also are harder, require more analytical thinking or sustained effort, than rudimentary ones. Though this might not be as much the case with elementary math; I could see a gifted student flying through much of the k-5 math in a very short time.

This is not correct. There is a lot of evidence that you can move parts of various subjects around, like having pre-calculus even in elementary or middle school rather than as the standard track in highschool.

The course called pre-calculus is kind of a grab bag. It combines trigonometry, limits, logarithms and exponentials, conic sections, and a few other subjects, some of which can be done before Algebra but some of which cannot.

Hmm… I’m not convinced. Maybe it’s more like a tree structure than a ladder, but I have a hard time picturing geometry or calculus without algebra or arithmetic.

Yeah, this is one of the biggest problems with traditional acceleration, and why I have a hard time endorsing it outright. I focus on it because it’s practical and it’s close to a strict improvement over an alternative of regular classes for advanced children, but I’m much more ardent in support of advanced curricula like the one the folks at Art of Problem Solving use. Their program remains my model for what education for the most advanced students should look like.

Similarly, Benezet did not actually remove math from the elementary curriculum, only arithmetic exercises.

Can’t these gifted kids educate themselves? I’m absolutely middling in intelligence, but as a child I devoured vast amounts of knowledge that had nothing to do with my school curriculum.

If a kid has intellectual curiosity, they don’t need encouragement, just access to information (e.g. the Internet).

Honestly not sure if your post is a deliberate strawman, but you make an assumption here that intellectual curiosity = gifted, or that intelligence and conscientiousness will always be correlated. Smart people can be lazy too. I’m more concerned that when a smart kid is unmotivated in a normal class people think ‘that kid needs to be more challenged’ rather than ‘that kid needs help to be more conscientious.’

I think challenging work is a necessary precondition – conscientiousness helps you most when the homework isn’t something you can breeze through with zero effort.

Maybe you’re middling in intelligence but very high in conscientiousness?

I’m high in intelligence but pretty bad at educating myself. At school and university I took extra classes, but I didn’t really read about all the many subjects that interest me that weren’t covered in classes.

EDIT: somewhat ninja’d

In college I tried to take the most difficult classes precisely because I was not likely to do rigorous studying on my own time. 🙂

They indicate that gifted kids are gifted in certain areas, but that doesn’t mean they are gifted in every area. Scott has mentioned the Indian mathematician Srinivasa Ramanujan, who was really gifted in math, but apparently did not manage that well in other subjects, IIRC.

I was good at math, my handwriting was similar to a crazy hen, I hated PE with every fiber of my being, and I absolutely hated music classes because I am tone deaf. If I was left to my own devices, I would just do math, read cool books, and forget everything else.

Schools are supposed to teach every subject in the curriculum, because we want kids to have a well rounded education. So even if a child loves math and really enjoys it, you may still need to drag the kid so they do at least a bit of exercise (or vice-versa). Children with perfectly all-rounded interests that resemble the school curriculum do not exist, some of the subjects will always be more boring.

Good thing you spent all that time on handwriting, music and PE, I’m sure that really came in handy later in life 🙂

Well, PE is important. I have ruined my health by not doing exercise, and I am slowly learning to do it.

PE was certainly no good for me. Until the testosterone fairy hit, I just couldn’t keep up, at all. I was rather surprised when I got older and was actually able to do some of those things they expected you to do in PE.

(the testosterone fairy is a heavily built bald (but otherwise hirsute) dude, who is about 6″ tall and sports diaphanous wings, a gold tiara, and a wand with a star on the end. In case you’re wondering)

It’s harder to educate yourself if large chunks of your time and attention are taken up with schooling you don’t need.

Of course, this begs the question if ‘being educated’ is different from knowing-a-lot-about-a-subject-you-are-predisposed-to-like…

I think that the so-called “truly educated person” should be Heinlein-esque character.

I tend to agree with the criticisms of that Heinlein quote. Much of that list is arbitrary. Some things in it are mainly useful in certain settings. Some things in it are useful in a wider range of settings, but the emphasis is odd. And some of it is probably from Heinlein assuming that things that happened to be useful to himself are universal necessities.

I agree. But also the “spirit of list” is what I’m getting at. Surely, I wouldn’t defend many or even most items on the list. Would you agree though that an ideal list for you might make for yourself would still be quite broad and include broad skills, specific skills, social know-how, and some quirky aspirations?

…limited usefulness? Which would you cut?

The only ones I can see that might not apply generally are conning a ship and building a wall. And even conning a ship isn’t a bad one.

Changing a diaper is important, if only for understanding what the people who raised you went through.

Planning an invasion means you understand the military, logistics, and large-scale planning. The last is especially useful.

Butchering a hog means you understand where meat comes from and the ethical choices involved and know some things about non-human anatomy that may be useful even if all you ever do is try to figure out if your dog is really sick or not.

Conning a ship…may not be that useful since “give orders” is also on the list. The importance of personal responsibility, perhaps? Quick decision-making? Being cautious with big expensive things? Learning this isn’t bad, it just may be redundant. If he means a spaceship, understanding orbital mechanics is becoming more important given satellites etc and the long-term requirement for the species to survive.