Little Soldiers is a book by Lenora Chu about the Chinese education system. I haven’t read it. This is a review of Dormin111’s review of Little Soldiers.

Dormin describes the “plot”: The author is a second-generation Chinese-American woman, raised by demanding Asian parents. Her parents made her work herself to the bone to get perfect grades in school, practice piano, get into Ivy League schools, etc. She resisted and resented the hell she was forced to go through (though she got into Stanford, so she couldn’t have resisted too hard).

Skip a decade. She is grown up, married, and has a three year old child. Her husband (a white guy named Rob) gets a job in China, so they move to Shanghai. She wants their three-year-old son to be bilingual/bicultural, so she enrolls him in Soong Qing Ling, the Harvard of Chinese preschools. The book is about her experiences there and what it taught her about various aspects of Chinese education. Like the lunches:

During his first week at Soong Qing Ling, Rainey began complaining to his mom about eating eggs. This puzzled Lenora because as far as she knew, Rainey refused to eat eggs and never did so at home. But somehow he was eating them at school.

After much coaxing (three-year-olds aren’t especially articulate), Lenora discovered that Rainey was being force-fed eggs. By his telling, every day at school, Rainey’s teacher would pass hardboiled eggs to all students and order them to eat. When Rainey refused (as he always did), the teacher would grab the egg and shove it in his mouth. When Rainey spit the egg out (as he always did), the teacher would do the same thing. This cycle would repeat 3-5 times with louder yelling from the teacher each time until Rainey surrendered and ate the egg.

Outraged, Lenora stormed to the school the next day and approached the teacher in the morning as she dropped Rainey off. Lenora demanded to know if Rainey was telling the truth – was this teacher literally forcing food into her three-year-old son’s mouth and verbally berating him until he ate it. The teacher didn’t even bother looking at Lenora as she calmly explained that eggs are healthy and that it was important for children to eat them. When Lenora demanded she stop force-feeding her son, the teacher refused and walked away.

Or the seating:

As Lenora hears more crazy stories from her son and friends, she keeps coming back to one question: “what does Rainey actually do in school?” Lenora tries to ask Rainey, but he always replies, “we sit still.” He also occasionally mentions painting and eating, but that’s it.

So Lenora goes to Rainey’s teacher one day and asks to sit in on classes to observe. Lenora is told that this is not possible. So she asks if she can know a little more about what the school is teaching Rainey. The teacher tells her that she is already told everything she needs to know, and that this is the “Chinese way.”

Since Lenora couldn’t get a look into Soong Qing Ling, she went to another local school and bribed her way into a classroom-observation post with some well-placed handbags. She discovered that Rainey was basically right. Chinese preschool really does seem to consist of sitting still. Unless given different orders, all students were required to sit in their seats with their arms at their sides, and their feet flat on a line of tape on the ground. This is not an easy task for three-year-olds.

There were two teachers in the classroom with a classic good cop/bad cop dynamic. The good cop stood in the front of the room with the desks splayed out before her. She would give simple instructions like orders to get food, water, or sometimes paint, though usually she said nothing at all. The bad cop was another teacher who prowled the classroom. Any time she saw a student remove a foot from the line, move arms from his side, or otherwise deviate from the instructions, she would yell at the student to fall back in line. Lenora spent about a week watching tiny kids get screamed at for trying to get water, shifting in their chairs, or talking to classmates.

Or art class:

When Lenora sat in on a kindergarten class, she witnessed an art lesson where the students were taught how to draw rain. The nice teacher drew raindrops on a whiteboard, showing precisely where to start and end each stroke to form a tear-drop shape. When it was the students’ turns, they had to perfectly replicate her raindrop. Over and over again. Same start and end points. Same curves. For an hour. No student could draw anything else. Any student who did anything different would be yelled at and told to start over.

The point of this exercise was not to teach students how to draw raindrops. Drawing raindrops is not an important life skill, and drawing them in a particular way is especially not important. Even the three-year-old students in the class seemed to realize this as many immediately created their own custom raindrop shapes and drew landscapes, all to be crushed under the mean teacher’s admonishment. The real point of the exercise was to teach students to follow directions from an authority figure. But more than that, the point was to follow pointless and arbitrary directions. The more pointless and arbitrary the directions are, the more willpower is required to follow them.

Chinese people presumably put up with this because it makes sense within their culture; why did Chu put up with it? Dormin half-jokingly suggests maybe she really wanted to write the book she eventually wrote, and this was her research. But Chu herself says it eventually got results:

After spending 75% of the book relentlessly complaining about her son’s Chinese education, with the occasional anecdote about how horrible her own culturally Chinese upbringing was, Lenora decides Chinese schools aren’t so bad.

After a few years in China, Rainey changed. Though Lenora constantly worried if Rainey’s creativity and leadership potential was being snuffed out, she couldn’t help but be impressed by his emerging self-control. He could sit still for longer. He always greeted people politely. He finished eating his food. He asked permission a lot.

Lenora didn’t realize what Rainey had become until she took him back to the US for a few weeks to visit family. There, the contrast between Rainey and his same-aged American counterparts become stark. Lenora’s friends’ kids ate junk food all day while Rainey asked for vegetables. They couldn’t read or do basic addition while Rainey was close to being bilingual and had started double-digit addition and subtraction by first grade. They wandered obliviously in their own worlds while Rainey’s Chinese grandparents were thrilled to receive respectful greetings every time Rainey entered the room […]

What really sold Lenora on Chinese education was that it apparently worked. At the time of writing the book, Shanghai was scoring first place in the world on the PISA exams, beating heavy-hitters like Norway and Singapore. Supposedly, education scholars and professionals all over the world were looking at China for wisdom. They all saw the bad, but they saw a lot of good too.

(before going forward, I should interject that China’s great PISA scores are kind of fake. China struck a deal with the OECD (the group that administers PISA) to let it conduct testing only in its four richest and best-educated provinces. Rich and well-educated places always do well on PISA. That China’s four best provinces outperform the average score of other countries is unsurprising. This article points out that if the US were allowed to enter only its best-educated state (Massachussetts, obviously) we would be right up there with China. So this probably isn’t as impressive as Ms. Chu thinks.)

This is just a sample of the great stuff in Dormin’s review of Little Soldiers, and I strongly recommend you read the whole thing. You should also read the comments, which point out that this may be more about a few elite Chinese schools than about an entire country. But I want to use these excerpts as a jumping-off point to talk about the US education system, unschooling, and child development in general.

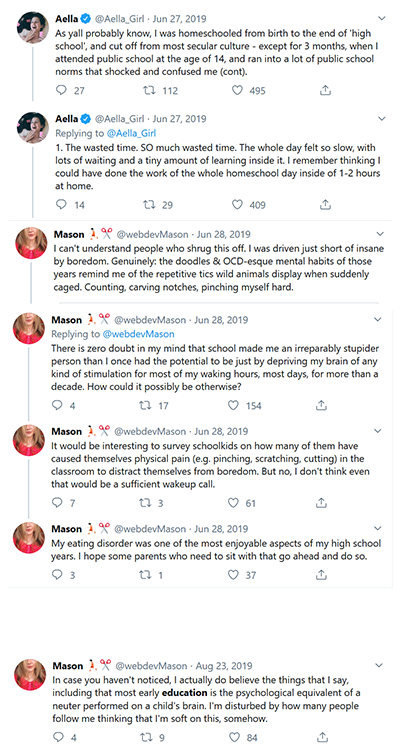

I predict most of my Bay Area friends would hate the Chinese education system as Chu describes it. I predict this because they already hate the US education system, which is only like 10% as bad. I’m especially thinking of @webdevmason and @michaelblume, who often write about the ways American education is frustrating, regressive, and authoritarian. Bright-eyed, curious kids come in. They spend thirteenish years getting told to show their work, being punished for reading ahead in the textbook, and otherwise having their innate love of learning drummed out of them in favor of endless mass-produced homework assignments (five pages, single-spaced, make sure you use the right number of topic sentences).

People with this position usually make two claims. One, US public school as it currently exists is awful, basically institutionalized child abuse. Two, this is bad for the economy. I’ve been through too much school myself to feel like challenging the first, so I want to focus on the second.

Salman Khan, John Gatto, and other education rebels trace the current school systems back to the Prussians, who invented compulsory education to prepare children for a career as infantrymen or factory workers. It’s a great story. Like most great stories, it’s kind of false. But like most kind-of-false things that catch on, it has an element of truth. Children who can sit still in a classroom and do what their teachers say are well-placed to become adults who can sit still in an open office and do what their bosses say. So (according to this logic), even if our schools are awful, they were well-suited to the Industrial Age economy. Some hypothetical mash-up of Otto von Bismarck and Voldemort, who wanted the country to produce as much as possible and didn’t care how many children’s souls were crushed in the process, might at least endorse the education system on widget-maximization grounds.

But (these same people argue), the Industrial Age is over. The most important skills now are entrepreneurship and creative problem solving. Reinventing yourself, selling yourself, carving out a new niche for yourself. Figuring out what’s going to be the next big thing and pursuing it without anyone else watching over you. We’re in XKCD’s world now, where 900 hours of classes and 400 hours of homework matter less to your career success than one weekend messing around with a programming language in 11th grade. The Prussian model of education stamps out the kind of independent agency that could help people navigate the weird, formless 21st century world.

How might the personified Chinese education system respond?

What if it said “I don’t know what you 老外 are doing in America, but I’m not crushing anybody. I’m just telling kids to sit here drawing 1,000 raindrops in a row without moving or protesting. If after that you decide you don’t want to found the next Uber, that’s on you. But if you do decide to found the next Uber, I will have taught you the most important skill: discpline. Learning how to sit still and obey others is the necessary prerequisite to learning how to sit still and obey yourself.”

If it was really mean, it might go further. “I notice most of you Americans suck at this skill. I notice you’re always whining about how you don’t have enough discipline to pursue your interests. Some of you are writers who spend years fantasizing about the novel you’re going to publish, but can never quite bring yourself to put pen to paper. Others want to learn another language, but reject real work in favor of phone apps that promise to ‘gamify’ staying at a 101 level for the rest of your life. You don’t need to feel bad about having no self-control; after all, nobody taught you any. If you’d gone to 宋庆龄幼儿园, you would have spent your formative years learning to sit still and focus, having your natural impulse to slack off squeezed out of you. Then you could have pushed through and written your novel, or learned 官話, or if you wanted to start Uber you could start Uber. At the very least you’d be doing something other than lying in bed browsing Reddit posts about how adulting is hard.”

My Bay Area friends treat people as naturally motivated, and assume that if someone acts unmotivated, it’s because they’ve spent so long being taught to suppress their own desires that they’ve lost touch with innate enthusiasm. Personified China treats people as naturally unmotivated, and assumes that if someone acts unmotivated, it’s because they haven’t been trained to pursue a goal determinedly without getting blown around by every passing whim.

What evidence is there in favor of one education system or the other?

I can’t find any good studies directly supporting or opposing either of these claims. The best I can do is The Development Of Executive Functioning And Theory Of Mind: A Comparison Of Chinese And US Preschoolers. They find that on various tests of executive function, “Chinese [preschool-age] children’s performance was consistently on par with that of US children who were on average 6 months older” (other sources say 1-2 years). But lots of interventions change things in childhood; this isn’t interesting unless it persists into adulthood, and I don’t see any work on this. This study on racial differences in personality traits found weak and inconsistent white-Asian differences on adult conscientiousness, but the Asian sample was Asian-American and differences in education were probably pretty minor.

What about circumstantial evidence?

First and most important, since extreme cultivation of discipline vs. laissez-faire childrearing is a property of parents as much as schools, any claimed effect would run afoul of all the twin studies showing that shared environment has few long-term effects on any trait. For example, this meta-analysis of factors affecting self-control that finds “no or very little influence of the shared environment on the variance in self-control”. But we can always invoke the usual loophole in shared environment findings: maybe the US doesn’t contain anything as extreme as the Chinese education system, so US-only studies can’t capture its effects.

Second, both Westerners and Chinese seem to include some very impressive and some less impressive people. It certainly doesn’t seem wrong to say that Chinese people seem more diligent and Westerners seem more independent, but there are so many potential biases at work that I would hate to take this too seriously as evidence for or against one form of education. Also, Chinese-Americans who are educated in US schools also seem more diligent than white Americans, so maybe the education system doesn’t contribute too much to this. Maybe Chinese culture promotes diligence better in general, this causes diligence-focused school systems, but the diligence-focused school systems don’t themselves cause the diligence.

Third, we could try to find more extreme versions on both sides and see what happens there. Pre-industrial populations with no education were famously bad at the discipline needed for factory work. From Pseudoerasmus:

The earliest factory workers were lacking in what Mokyr & Voth call “discipline capital” — non-cognitive ‘skills’ like punctuality, sobriety, reliability, docility, and pliability. Whether they had been peasants or artisans, early workers were new to industrial work habits and they had a strong preference for autonomous work arrangements. They were accustomed to setting their own pace of work in farming, domestic outwork, or artisanal workshops, and disliked the time rules and strict supervision of the factories.

All this is consistent with colourful descriptions of the early history of the textile industry in the Global South, including Japan. Mills were described as places of chaos and disorder. They were supposedly filled with workers ‘idling’, ‘loitering’, ‘socialising’, smoking, tea-drinking, or just disappeared for the day. In Japan, “twenty percent of the female operatives…absent themselves after they receive their monthly pay check” (Saxonhouse & Kiyokawa 1978). In Shanghai, it was said female mill workers could be found breast-feeding infants during work hours (Cochran 2000). Or at Mumbai mills, workers “bathed, washed clothes, ate his meals, and took naps” (Gupta 2011).

But this could be as much about expectations as about abilities.

Which historical culture had the most authoritarian-instillment-of-virtue-focused approach to child-rearing? Surely the New England Puritans were up there – remember that eg Puritan parents would traditionally send children away to be raised by other families, in the hopes that the lack of familiarity would make the child behave better”. They certainly ended out industrious. But they were also creative and self-motivated, sometimes almost hilariously so. On the other hand, I’m not sure that the Puritans who ended up incredibly creative were exactly the same Puritans who suffered extreme strict child-rearing – there seems about a century gulf between the evidence of authoritarian parenting in the 1600s and the crop of geniuses born in the late 1700s – so I’m not sure how seriously to take this.

Fourth, we could look at US trends over time. Both US parenting and US schooling seem to be getting less authoritarian over time; 31 states have banned corporal punishment since 1970, and the teachers I know confirm a shift away from most forms of discipline. Over the same time period, children have gotten weirdly better behaved – less crime, less teenage pregnancy, more willing to jump through various stupid hoops to get into a good college. This seems to contradict the Chinese theory – the children are no worse at controlling their impulses. But there are other findings that contradict the Bay Area theory – entrepreneurship is decreasing; more top students are choosing to go work for a boss at a big bank rather than go do something weird. I think the better behavior is probably just caused by lower lead; I have no idea why people are more risk-averse. Secular decline in testosterone, maybe?

Fifth, we could look at research on the effects of preschool more generally. Some studies find that US preschools do not make children smarter, but still improve life outcomes like graduation rates, crime rates, and employment. Although there are lots of theories about the “noncognitive skills” that accomplish this (including that they don’t exist and the improvement is an artifact of bad experimental technique), this is certainly consistent with preschool teaching children discipline at a critical window. If this hypothesis were true, the effect of preschool would be much larger in China, but I don’t know of any Chinese studies on the topic.

Sixth, we could look at the research on meditation for very young kids. The Chinese theory casts preschool as a sort of dark-side form of mindfulness. In traditional Buddhist settings, monks would sit perfectly still and concentrate on the most boring thing imaginable, and the head monk would slap them with a bamboo stick if they moved. The resemblance to the school system is uncanny. So maybe school’s effects on self-control could be modeled as a sort of less-intense but much-more-drawn-out meditation session. Unfortunately, the studies surrounding mindfulness in kids are crap, so this doesn’t help either.

Really none of this seems very helpful and we’re kind of left with our priors. And maybe one of our priors is “don’t abuse children”, so there’s that.

But what about the Polgars? They turned all three of their children into chess prodigies through a strategy that seemed based around exposing them to absurd amounts of chess at a very young age. If we generalize, it does look like very young children might have very plastic minds that you can shape through out-of-distribution experiences. But Lazslo Polgar insisted that his technique didn’t use force; the point was to interest his children in the material so avidly that they inflicted near-Chinese levels of intensity on themselves in order to study it more successfully.

One problem with the physical universe is that even after you study a question in depth and decide more evidence is needed, there are still real children you have to educate one way or the other. I have no general solution for this, but the Polgar strategy seems like a good deal if you can pull it off.

The idea of multiple classes per semester of school is that children will learn multiple topics effectively simultaneously.

Is it possible to get superior results by exposing kids to a variety of learning strategies – if not simultaneously, then consecutively? (Is anything gained by forcing a child to obey during the entirety of schooling that wouldn’t be gained by forcing them to endure it for 1 hour a day, or one semester of preschool [with periodic followup, perhaps]?)

Given the inherent difficulties of finding out what’s best for a particular kid, such broad exposure may help discover what’s best for each particular kid.

If you’re going to experiment with conflicting priors, you may as well throw everything plus the kitchen sink (available in Montessori schools) at it.

The counterargument to this would be that some teaching strategies might require full immersion to be successful. Can you imagine a kid switching from a US-style classroom to a Chinese-style one each day? It seems like it would be hard to get young kids to understand that they have to sit still and unquestioningly obey one teacher while giving them more latitude for creativity with a second teacher.

Of course this is all speculation, and you’re right that it would be valuable to be able to try different techniques — both to see what works for individual kids as you noted and to see what works in general. Randomized controlled trials are of course rather difficult to run on education.

Same teacher, different tasks, at least for pre-school.

It is really hard to get children to consistently follow totally different sets of rules from different authority figures in similar environments. I don’t think you could make this work.

Really? My impression is that young children intuitively understand this sort of thing. They learn quickly that mom and dad are different people with different standards who respond to behaviors differently (and they adapt themselves accordingly).

Note that even in the book, the child seems to have understood that even though he would be forced to eat eggs at school, he could still refuse them at home.

I’m curious why you think this. My kids (2 and 5) have absolutely no problem following different sets of rules in different contexts, it seems to come very naturally to them.

Definitely. Almost all kids quickly learn which parent is more lenient on what, who to ask for what and adjust (to varying extents) to each parent based on the parents’ moods.

@Matt M

@natethenate

@baconbits9

1) Note that I said “totally different.”

If two parents have moderately different degree of willingness to give a child a cookie for good behavior, either way the rule still looks like “sometimes child gets a cookie for [list of behaviors]” when viewed from thirty thousand feet. The child may strategically seek a decision from the cookie-generous parent, but they’re still following a broadly comparable pattern either way. But imagine the contrast between two parents, in the same house, one of whom will say “you can have a cookie literally any time you want” and one who will say “you can literally never have a cookie.” They take turns controlling cookie access on alternating days.

Now those are two totally different rules in the same environment.

2) Note that I said “consistently follow” totally different sets of rules, not “understand” them.

The most common outcome of one parent being much more lax than the other on a particular subject is that the de facto rules start to devolve towards the standards of whichever parent is more lax. The children understand that there are two sets of rules just fine. The problem isn’t that they don’t understand it or can’t navigate that environment. It’s that they will be much harder to train to follow the strict rules when they have the lax rules as a ‘more fun’ example.

Remember the cookie example from above. Realistically, the never-cookie parent is going to spend a lot of time frustrated that the child absent-mindedly just walks right up to the cookie jar and takes out a cookie without so much as a by-your-leave… Because the child has a very strong incentive to “forget” that they’re supposed to be following the strict rules. This greatly increases the disciplinary burden of enforcing the strict rules on no-cookie days, which in turn makes it a lot harder to maintain and train standards of no-cookie behavior. And increases the risk that he child will start to resent the no-cookie days, view “not eating cookies” as a sign of humiliating subservience, and in adult life rebel by gorging on cookies or something.

3) Note that I said “in similar environments.”

This part of the statement is doing a lot of the heavy lifting. Children can definitely learn to follow different sets of mutually exclusive rules in different parts of their overall world. But that’s very different from teaching them “in this building, with this teacher, you get to go to the bathroom whenever you like without permission, unless it is between 9 a.m. and 11 a.m. in which case you can’t because that’s discipline training time.” In that scenario, the rules are changing sharply without an underlying change in the surrounding environment to explain the change.

@ Simon_Jester

You’ve set the bar really high — *very* different sets of rules, in *almost exactly* the same environment. I can’t speak personally to a situation like that.

What I can say is that if your parameters are loosened a bit — somewhat different rules for two different classrooms in the same school, for example, or quite different rules for school vs after-school day care vs home — they seem to have no trouble at all.

I’m inclined to believe they could also handle the original proposal, unless you have some reason to think they can’t.

Parents can be very different and have very different standards. Many kids grow up in houses where one is the disciplinarian and one is the comforting/motherly figure., kids navigate these waters regularly.

For the “totally different rules in similar environments” concern, one could paint and decorate a classroom to look totally different, and put all the classes with one set of rules into that classroom taught by one particular teacher.

@natethenate

I think the model of “can they handle it” or “do they understand it” is unhelpful in this context. The problem isn’t that children lack the mental wherewithal to understand that there are different sets of rules in different contexts. The problem is that if the bulk of their time is spent in “laxity context” and then you try to send them to a discipline class to teach them discipline only once a day (or a few times a week), while not teaching discipline at other times…

I don’t think it’ll work. The child will tend to react to “discipline class” by rebelling against the discipline, or by being compliant in the short run but in the long run thinking of it as an unwelcome humiliation, and adopting opposite behaviors as a way of asserting independence.

It’s like, imagine you grow up with fairly typical American parents, but they take you to this really really strict 19th century style church where there’s no fidgeting and no talking and you have to sit still and sing hymns exactly in key and you get a switching if you disrupt anything or mess anything up.

The odds are pretty good, IMO, that coming away from that experience you won’t have “learned discipline” in that church. You’ll have learned to hate going to church. The experience of “discipline class” has to be repeated frequently enough that it becomes a normal part of the child’s experience, as opposed to an unwelcome periodic intrusion on the child’s mental life.

@baconbits9

Yes, but if the two parents are acting as a coordinated team (“wait till your father gets home,” “go ask your mother to help you with that,”) then there is de facto only one set of rules to navigate. The fact that the parents take on different roles doesn’t mean the child won’t get a spanking for making a scene; it just means the spanking is deferred until the disciplinarian parent shows up.

Insofar as there are two rulesets in opposition to each other, the child is going to develop preferences for one and resentment against the other. No prize for guessing which one, if one is “go do your own thing” and the other is “get screamed at for drawing raindrops wrong 1000 times.”

@localdeity

I actually think that would help.

The only problem is that the students are still going to a designated Discipline Class that makes up only a small percentage of their time, as opposed to the larger percentage taken up by the Chinese preschool as a whole.

(Sorry for accidentally clicking “report” instead of “reply” at first)

Children can generally understand games, where rules have to be obeyed. Why couldn’t they understand the concept of a “strict discipline day” (or even week, etc) which its specific rules? (Except breaking them would have more serious consequences than most games).

I’m biased toward the highly-adaptable view of childhood brain plasticity. You certainly could have a system that samples from many different approaches, but I’d think from that system you’d get the worst features of all these systems. Presumably, children who are forced to sit and stare at the wall for hours on end are going to develop a more nuanced strategy for keeping their brain occupied sufficient to accomplish their task than children who do it less frequently. Also, I think we tend to reduce a whole system of pedagogy to the parts that are most striking to our eyes, and a partial instruction in many theories would give short shrift to all of them.

A while back Scott published a post about guidelines versus recommendations that I think is apt here. The first question you want to answer is what you want the education to achieve, then tailor your approach to that strategy. Some strategies are clearly better than others in general, but that doesn’t translate to “always better for everyone”, which is what this kind of discussion usually devolves into. And why should we think one size would fit all learners? Indeed, if we look at a statistical distribution and say that because the average child in one learning approach does better than the average child in another we’re missing something about the individual children in both systems – especially the children for whom that approach didn’t work. In effect, we try to mold children into statistics, which is an artificial construction.

Some kids probably thrive in a highly-structured environment, either because they lack discipline and will benefit from having it imposed on them, or because that’s the kind of environment their brain naturally works well in. Some kids might thrive from instruction based on self-directed learning, like in Montessori, for similar reasons of deficiency or aptitude.

I see the issue of teaching style as similar to career choice. Lots of people treat choosing a career as having to find the One Perfect Profession they will be uniquely suited to. But I think that’s wrong, and it makes the selection process not only more difficult than it needs to be but also less targeted, as you’re forced to resolve nuance into black-and-white questions of Good/Bad paths. In my case, I’m certain I would have enjoyed a number of different career paths/branches other than the ones I chose. Instead of optimizing for perfect, I optimized along preferences of outcomes. Because of that I’ve never regretted the paths I didn’t take, even though I know they held some satisfying opportunities for me that are no longer available. I think individual parents should do the same kind of nuanced decision-making when selecting which learning style is best suited for their children’s needs and aspirations. It’s probably a failure mode to decide on one technique to rule them all, since every child is different.

Getting rid of leaded gasoline explains much of the decline in crime last few decades. This could well also be part that.

Later in that same paragraph:

Anyone have a good link to some study about that?

https://www.motherjones.com/kevin-drum/2018/02/an-updated-lead-crime-roundup-for-2018/

Wikipedia treats it as a hypothesis which is difficult to prove conclusively. The page also mentions legalization of abortion, which Freakonomics pointed to, as another (not mutually exclusive, of course) possible explanation. I would think comparing different countries legalizing abortion at different time points could be enlightening, but I’m too lazy too look it up right now.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lead%E2%80%93crime_hypothesis

There are dozens of theories on this. Most are of the type “this confirms what I’ve always been saying!”.

I assume it’s more than one reason for a complex thing like this. But the lead theory has some real good data. Different jurisdictions abolished leaded gasoline in different years, and if you correlate that with crime state 23 years later, it looks quite convincing.

At least that’s what I’m told, and what the possibly cherry picked curves I’ve seen show. I haven’t independently researched this, of course.

The “23 year” factor comes from lead damaging growing toddler brains, but it takes about that time for the kid to grow up to a violent man in his prime.

I went to school from K-12 in 1964-1976 in Sherman Oaks, CA, which was then home to the busiest freeway interchange in the world (405/101).

Who do I sue to get my missing IQ points back?

The effects of lead on IQ are probably overrated (they reflect a lot of SES cofounding) and they seem to be concentrated on the executive function, impulse control, and working memory.

Oh, I missed that 🙁

Guess not only great mind think alike!

I literally read that sentence you quoted, verbally thought “it’s probably just lead” and then read the part on lead a few seconds later. It was great.

The interesting thing about the lead connection is that China has much worse pollution than the US. (I don’t know about lead pollution specifically — does anyone know of any data on this? I’d be surprised if they had less lead pollution though.) Would Chinese children be even more obedient with less pollution? I’m not sure how this fits into the argument. It will be interesting to see what results China gets as their pollution situation improves.

I would guess that’s true now, but leaded gas only ended in the 80’s, it accounted for the vast majority of lead in the air, and the US had a much larger auto market during that time. China might have missed the lead issues in the same way that Africa (hopefully) misses the coal issues.

I don’t know how to effectively summarize this paper, but Lead contamination in China appears to have peaked later than in the US.

The Nevin thesis is basically that all modern crime is caused by lead

https://www.amazon.com/Lucifer-Curves-Legacy-Lead-Poisoning-ebook/dp/B01I3LTR4W

Crime rates are lower now than they were in 1970, but were in the process of exploding in 1970 after having increased dramatically during the 1960s.

Is it possible that crime rates are not decreasing but that record-keeping of crime rates are being manipulated so that it seems as if crime rates are decreasing? The incentives of the record-keepers align with showing such a decrease, no?

Almost certainly the case, and I’m not sure it matters.

There’s a famous NYPost headline called “Headless Body in Topless Bar” where a man went into a bar, held them up at gunpoint, and made the bartender cut the head off a patron. On the front page, just below the headline, there is a picture of a man kicking and screaming at the photographer as he is thrown into a police car.

The punchline is that they are different men.

The man in the picture had walked into the Waldorf Astoria, a famous 5-star hotel in NYC, ran into a lady in the stairwell and stabbed her to death. That’s ONE DAY in NYC in the 1980’s.

Whatever else you want to say about American urban crime rates, they are nowhere *near* that sort of level. You’d notice. Maybe SF is starting to get close in a categorical “Difference in magnitude not sufficient to be difference in kind” sort of way. Nowhere else is that bad yet.

Absolutely. The question is a matter of degree.

The decline appears even, and to approximately the same degree, if we look only at homicides. And it’s really hard to fudge the numbers on homicides in anything resembling a developed society. In Iraq in the years following the 2003 war and at the height of the insurgency, independent investigation found that government records of homicides tracked fairly closely with reality.

I’ve heard that and have generally believed it, and the Iraq example is a dramatic illustration of how far the principle can carry.

I’d add the caveat that large changes in the quality of trauma medicine can be a confounding factor in the use of homicides as a proxy for levels of violence. If a hospital system get significantly better at handling trauma cases resulting from violent crime, then that can produce a declining homicide rate even if acts of violence were happening at the same levels, because if the victim survives, then the incident probably shows up as attempted murder or aggravated assault instead of murder or manslaughter.

If anything, I would guess that the crime stats are more complete today then they were before the 1970s. There are certain crimes, like rape, that are more likely to be reported today versus the past. There are more “eyes” on the world today, so it’s harder to commit a crime without anyone knowing. I also suspect that there were more crimes in the past that were just ignored than there are today. If a black man was found beaten in an alley, I suspect that 1950s cops would be less likely to investigate, or even report it than they would be today.

Counterproposal: people care much less about their neighbours today, qua lowered community participation, so fewer crimes are reported / investigations demanded.

If your neighbour 3 doors down vanishes, in 1950 she’s in your church, you play bridge on Sundays, and she sometimes watches your kids. Everyone knows her vanishing is out of character and the whole church goes to the police to demand an investigation.

In 2020, you don’t know her habits; you don’t even know her name. You don’t even notice she’s gone.

That doesn’t work for murder. There is almost always a body, which turns up. And even if the victim doesn’t know her neighbors, she probably has a job, or a kid in school, or … .

And murder rates have fallen roughly in half from their peak a few decades back.

It’s possible, but the same incentives would have led to under-reporting in the past too. Here’s an article in Chicagomag about the Banana-republic tier efforts to minimize reported crime:

https://www.chicagomag.com/Chicago-Magazine/May-2014/Chicago-crime-rates/

It’s enough for me to note that the homicide rate, considered the most reliable crime statistic, is not different than it was in the 1950s, despite better medical care today allowing more people to survive murder attempts, despite better police work, despite better surveillance, despite less absolute poverty, despite less de-jure segregation, ect.

As a data point, in my neighborhood in Seattle, in the local neighborhood discussion group, someone a few weeks reported that someone broke open the hood of their new car, ripped out a bunch of engine parts that had resell value, and did so much damage that the repair estimate totaled the car. The Seattle PD refused to take a report, because they didnt consider it “car theft”, it was “petty vandalism” or maybe “petty theft”, as if someone had stolen some old tools of a back porch or something. The real reason, of course, is that progressive crusader mayor is embarrassed by the “Seattle Looks Like Shit” meme, and has ordered the crime stats down by any means other than actually imprisoning people.

This seems almost certainly false to me based on experience in my area. I’ve lived in the same region of a major city for 30+ years, my parents lived in the region for at least 20 years longer than that, and some of my elderly neighbors who I know well have lived in the general area for 85+ years. Over that time crime has vastly vastly vastly decreased. Houses and cars used to be broken into on a weekly or more frequent basis. That doesn’t happen anymore. When I was a kid people used to steal our trash cans. That doesn’t happen now.

It’s also possible “Suburbanization” has something to do with this….

I mean if you look at something like crime “Paying” some threshold $$$/hour – it’s a lot more time consuming to rob a few cars scattered through a couple miles with a lot of yards and dogs in-between than when they are all in the same building…. Seriously – lets say 10% of cars are unlocked just because… You could go down a 1-mile suburban road to check 10 cars or go through some Big City Parking garage/Apartment Complex and pull 400 car door handles in one parking lot… And so if you can make 5x as much working at WalMart, cutting lawns, or fixing cars – why resort to stealing?

Western culture is on a trend to consider children people too who have the right to be self-directed and happy.

And when my kids grow up useless hopefully UBI or similar will save them.

Simultaneously it is on a trend to treat infants like babies, children like infants, and teenagers like children. Safety-first is the rule of the day: self-reliance and independence don’t seem to be a priority.

This is vastly less true in America than in any East Asian culture, at least among the middle/upper class (which is pretty much all the children I’ve met in Asia). It’s insane how childish Japanese/Chinese young people are in comparison to their Western counterparts.

Yet the Japanese allow their kids a lot more independence than Americans, walking to school by themselves etc.

There’s comparatively little crime in Japan. And for all I know Japanese journalism doesn’t sensationalize and amplify what crime they do have.

Indeed. The reason American parents don’t let their kids walk to school is less “they are likely to be abducted” and more “the media has falsely convinced them they are likely to be abducted.”

That is certainly a reason why they can get away with raising their kids to be more independent. Though as Matt points out, children virtually never get abducted by strangers in the US anyway.

I don’t know how true it is that Japanese (or Chinese) kids are childish compared to Americans. I’ve stayed with a young family in Japan a few times and didn’t notice any particular immaturity.

Here’s a youtube video depicting Japan’s culture of raising kids to be independent, getting to school alone at 6 years old is the norm: Japan’s Independent Kids

I also wonder how much of this is helicopter parents seeing the inside of their own bubble. My kid’s* in 1st grade and there are lots of 1st graders walking there in the morning.

Maybe there’s a question of scale. We drop our kid off by car, because although we don’t live all that far away, it is longer than I’d expect a six year-old to walk, plus you have to walk along the shoulder of one busy thoroughfare without a sidewalk and cross another one, and there are for whatever reason often car crashes along that route. If we lived in the neighborhood of the school where our kid could walk there by staying on sidewalks and not having to cross any road with a speed limit over 35mph, it would be different.

Of course there are probably parents in that neighborhood who still don’t think that’s safe enough. And presumably some of these Japanese parents are letting their kids walk to school even in busy urban places with lots of challenging intersection crossings…

*ETA: Clarifying comment inspired by baconbits9’s comment: I have multiple kids.

My guess is that parents are a lot more protective of their first children and in general more relaxed as things progress. Lots of 1 child families means lots of kids who are more protected.

But doesn’t Japan have a serious fertility problem? I would guess this means most kids in Japan are only children.

I believe Japan’s main problem is the number of childless women. This link has (eyeballing the graph) roughly as many women with 3 kids as with 1, and the largest segment by a good amount is 2. However the 20%+ who end up with zero kids is the major drag on their fertility rate.

It was stupid of me to say that they’re way more childish. Upon reflection I don’t think it’s true, and I do think it’s a pretty racist sentence so I regret writing it.

@Enkidum:

I don’t know if it’s true, but it isn’t racist. Culturalist, maybe.

Enkidum,

This whole post is a speculation about the superiority of one culture, in some respects, over another and its causes. If there’s any point in discussing that at all, we need to be able to say both positive and negative things about different cultures. So I don’t think your post was bad at all except it would have been more useful with some evidence.

Also – many American schools have consolidated and so distances children travel are much further.

We are 10+ miles away from our kid’s school… No way the kids are walking 10+ miles each way…. 1/2 mile – Sure, walk or ride a bike… 10+ Miles – nope!

Wait. Are infants and babies two different things?

Are infants between babies and children in the variant of English you speak? I would use “toddlers” for that age group.

I’ve always considered infants a subtype of babies. A baby is anything pre-toddler. A baby starts as a newborn, then spends a few months as an infant, then a few more months as baby (NOS), then becomes a toddler.

Baby is broad and generic, ranging from a fetus still in the womb to a toddler. Infant is more specific for a young baby who is out of the womb but with almost no independence. My wife and I strongly disagree on toddler, when our youngest took her first steps at 10 months I said she’s a toddler, she said no way until at least a year old.

Pssh, I use “baby” for anyone under the age of 25, or under the age of 30 and doesn’t have kids.

@baconbits9: A toddler is a person who toddles.

https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/toddle

I was under the impression that China has low pop culture output.

They also have a lethally censorious government, to be fair.

True, but I think the government also wants more pop culture output (but, to be fair, not at the cost of censorship)

I found this lamenting the cultural output: http://en.people.cn/90782/7973104.html

I’ve found at least some people (Liu Cixin) suggesting that Chinese science fiction is currently going through a golden age, but I’ve never seen any work from anyone other than Cixin himself. And, of course, Cixin has said himself that he couldn’t get away with publishing the Three-Body Problem today, due to its criticism of the Cultural Revolution.

There is definitely a Chinese SF boom, with a bunch of great writers. If you don’t read Chinese, your best bet is to check out the anthologies Ken Liu has edited in translation, Invisible Planets and the follow-up Broken Stars. Some of the authors in there have longer works available in English as well.

I’ve heard the rumor that at least part of the SF boom is that CCP officials who went to the west and interviewed high-tech workers found out that a lot of them had grown up as SF fans, and so is interested in promoting domestic SF for its knock-on effect on (post-)industrialization, but I can’t confirm this.

@Erl137 – Thanks. I just bought a copy of Invisible Planets. I’ll take a look at it.

I’ve seen some discussion, a few years back, of the puzzle of why China, with a very large number of educated people, scientists, and the like, doesn’t seem to be producing a corresponding number of really top level people, Nobel winners and the like.

I think the draconian censorship coupled with total command economy and the resulting culture of corruption might all contribute to the issue.

Command economy ensures that the Party officials decide how much science, and of what type, must be completed before the end of the current Five Year Plan.

This is obviously impossible, since science doesn’t work like that, but fortunately scientists don’t need to actually discover N new things by the end of the fiscal year, they just need to report that they did. Endemic corruption makes this a lot easier.

Meanwhile, strict control over all forms of expression ensures that scientists don’t step out of line. This prevents them from collaborating effectively (unless they are collaborating on faking results for the bosses), and it also ensures that smart people get “taken care of” pretty early on — since smart people tend to ask all kinds of inconvenient questions, and we can’t have that.

In some extreme cases, entire scientific disciplines can be obliterated by fiat, e.g. genetics in the USSR (and “cybernetics”, a.k.a. computer science, almost followed suit).

That sounds like a description of the USSR. Is it clear that the same is true of China?

It’s not a democracy, and there are a substantial number of state owned entities, but my impression is that it’s mostly a market economy, and one would expect that to produce occasional innovators along the lines of Elon Musk, whether or not it produced the equivalent in academic fields.

That’s a fair point; that said, China does occasionally investigate its millionaires for corruption and promptly has them disappeared (after seizing the assets, of course). Ironically, all of their corruption charges are likely true, since there’s no way to get anything done without bribing someone, but still, I can see how it would create a chilling effect. Also, I’m not sure to what extent their government controls scientific institutions, as compared to commercial ventures — their level of control might well be higher.

I do think there’s a very real way in which the anti-authority/independent behaviors that make for a good entrepreneur are discouraged in China. If not by the education system, by the fact that trying to break into a market as an outsider quickly results in bureaucratic hurdles being thrown in front of you by incumbent players with connection to the local political leaders. To succeed you have to be willing to play nice with the existing players, something antithetical to how we describe entrepreneurship, since we usually group that with “disruption”.

I can’t offer an explanation, but I can say that in my field, I encounter Chinese papers fairly regularly. While none of them are flat out wrong or bad science, they’re often just…unimpressive. The papers are legitimate contributions that fill in gaps, but they’re never making huge strides that open entirely new areas or dramatically change our understanding of a system.

Surely this is what happens when you’re forced to sit still as a child and value order and structure above creativity – competence instead of innovation?

Yes, but you often feel the same with western papers, when comparing new papers with old one. It’s biased, as old paper which are still cited are the good ones and/or the ones that pionnered a new field….But still, I feel new papers are more “formulaic”, and tends to do just the minimum to be published and prepare another publication. You feel that the metric to be maximized is paper/year, and if you can say something in 3 diluted papers or one outstanding one, the 3 diluted are now often prefered.

This is a well known consequence of the publish or perish attitude. Academics are evaluated on how many publications they have, which is easy to measure, rather than their quality, which is much more difficult to measure. Some institutions use number of citations or journal prestige as a proxy for quality, but those metrics have their own issues.

Honestly, I don’t think that’s it. My field is comparatively small (if we ran a solo conference, it would probably be two orders of magnitude smaller than Society for Neuroscience) and very recent, with most of the really powerful tools only becoming available in the past 40 years (which seems like a long time, but it’s a small field with a lot of ground left to cover). As a result, every year people are publishing what will doubtless become major, foundational papers that make huge strides in core questions. We’re where genetics was in the decade or so after Watson & Crick, basically.

Obviously some labs are more innovative than others, but *none* of those innovative labs are in China. That strikes me as noteworthy.

@Cerastes:

FWIW, I am not a biologist but I do work with plant genomics a little. From what I’ve seen, there’s a massive amount of research going on in China in this area, but most of the papers they publish are just… meh.

I’d think that an apparent surplus of boring papers might be due to of a lack of out-of-the-box thinking in a field but also might be due to those making-sure-we-got-this-right kinds of studies being a necessary foundation before a new breakthrough can be made. In other words, are the Chinese reserachers failing to aim for big breakthroughs or are they totally aiming for them but using a strategy of producing a large quantity of small steps of progress?

With a replication crisis happening more or less in various fields, I feel pretty positive about the prospect of one part of the science world being intensely inclined on doing boring just-making-sure-we-got-this-right kind of research. Maybe the seeming lack of big results among Chinese research is more congruent with reality?

True in my field as well. Well, where “Chinese” means “Chinese universities”, expat Chinese do as well as anyone else — which suggests the causation could go the other way, if good researchers prefer to move abroad.

Also my experience.

Plausibly this could be the whole effect: if you’re good enough to innovate, why not boost your potential by moving to the US?

I’ve always heard that that is a pretty straightforward consequence of the incentives in Chinese academia, which emphasizes quantity over quality much more than the US/europe, and has high enough standards for quantity that even principled researchers need to spend a lot of their time pumping out least publishable units.

What does it mean to be a “Chinese paper”?

What I’m looking to disambiguate is someone like my wife’s cousin. She was born and raised in China, but came to America for college. She’s now a professor at Berkeley, and respected enough to have been inducted into the National Academy of Sciences.

How would you count her? Is she “Chinese” because of her name, or “American” because any paper she puts out is going to say “Berkeley” (even though her formative years were in China)? I don’t think this is such an edge question, given the number of foreigners who come here to study.

And whatever you decide there, how does it impact Scott’s question, anyway?

I wouldn’t be surprised if this is a fairly large part of it though. The high-end Chinese students figure out a way to get to a Western country, where their talents pay better, leading a to a brain drain in the homeland.

I think the reason is that Nobel prizes (with one notable exception, which China is unlikely to get) tend to be given to people at the end of a long and glorious career, while China in spite of their long tradition of education has been ramping up international science fairly recently.

One explanation for Chinese papers being dull is that where a Western author would write one big paper with all the results and insights, Chinese (or Russian) authors would write fifteen papers, one on each nugget of the research, with lots of repetition and 20 co-authors.

One could speculate about why this pattern exists, but at least the last time I looked at publications from China it was true.

Maybe a western author 20 years ago. Current western authors do not differ to their chinese or russian counterparts, at least that’s my impression.

As an insider, I feel that when research was more a hobby than a job (because the pay is either garanteed whatever you do (early 20th century academic?), or you just are wealthy enough it’s irrelevant (19th century and before?), it’s pure self motivation and intellectual competition among peers, and I think this hobby-like science produce flamboyant (sometimes wrong, but flamboyant anyway) outcome at a reduced frequency.

When it’s a job with external evaluation, it produce scientific paperwork, safe, frequent and boring.

If we wanted to take Nobel Prize results really seriously as an indication of talent, China’s extremely low on both overall Nobels per capita and scientific Nobels per capita. Russia, for comparison, has about 30x as many in science. That comparison probably goes a decent way toward cancelling out “draconian censorship coupled with total command economy and the resulting culture of corruption” as a factor @Bugmaster, since both countries have been pretty authoritarian in recent history (I’m assuming Russia inherited the USSR’s Nobels in the Wikipedia dataset). Even if we discount everything pre-1976 I can’t imagine that would close the 30:1 gap meaningfully – for example, the listed entries since 2010 include only 1 scientific Nobel for China and 60 for the US, if I counted right.

That seems to leave us with either a long lead time required to make important discoveries, a flawed Nobel selection process, or something being seriously wrong with China’s education system, general culture, or whatever else. I’d bet the next 10 years will clear things up considerably.

I am totally outside the scientific community, but from my lay knowledge my guess is all of the above.

People have for many years pointed to the low number of Nobels from Japan. But these complaints are out of date. Japan has more Nobel prizes in the 21st century than the 20th.

I don’t know how Japan turned it around. Maybe it just took a lot of time to build up invisible intellectual capital. It’s too soon to hold this against China. Or maybe Japan changed something. But what changed definitely wasn’t the obvious attributes of the educational system.

I wouldnt even call it “invisible”, a lot of Nobels are for applied, not theory.

Over the last 10 in chemistry only 2/10 could be realistically be called “theoretical” and both still required some experimentation. In physics 3/10 are theoretical in nature, one of those 3 being split.

Are you saying that people in China aren’t producing really top level people, or that Chinese-ethnicity aren’t top level people in proportion to population? The former could be answered by immigration, the latter could be that the most talented Chinese people are optimizing for things not measured by our definitions of top level. Which is to say, a cultural difference in the standards by which top level status is conferred (similar to how fiction awards ceremonies largely produce result orthogonal to general populace evaluation). If China’s accrual of world power/influence is disproportionate to its quantity of top level people, that points to the measure of top level people having fallen to Goodhart’s Law.

What I was saying was that people in China don’t seem to be producing top level people at anything like the scale one would expect. That was based not on my own observation but on discussions I had seen by people trying to explain the pattern.

My understanding is that there’s no safety net to fail and perverse incentives to conform.

As such, “top level people” tend to emigrate, particularly given the historical economic situation.

I think Chinese pop culture mostly stays in China.

Japan has a similar school system, or even more military-like (e.g. kids wearing uniforms), and it exports lots of pop culture. Arguably, Japanese pop culture is at the present more innovative than the nostalgia-porn Western pop culture.

Censorship really is a huge issue. Good art tends to ask hard questions, and it’s hard to get that when censorship is so strict. One of the few pieces of Chinese media to make it outside is webnovels, and webnovels are notable for being one of the least censored forms of media in China. Even there, there are known cases of popular web novel authors having to censor large chunks of their works.

Here’s a note from the govt after a huge number of novels were taken off Qidan, a major platform:

There have been several cases of novels being delisted for referencing religion, politics, or sexuality too much. This can sometimes also extend to descriptions of violence that are seen as overly gorey. Enforcement is super inconsistent, which creates a chilling effect because authors don’t know where the line is and so tend to play it safe.

Chinese schoolkids wear uniforms as well, or at least some of them do.

I was under that impression until relatively recently. But, there’s a whole world of ‘Chinese Web Novels’ with its own tropes and genre conventions, and more authors than you could ever read. From what I hear, these are really popular with young Chinese people, on the level of Japanese manga or such.

“Culture” you want to showcase in public only really develops with surplus wealth being available to fund it… China was one of the poorest per-capita nations in the world 30 years ago…

Now that the Chinese incomes are coming up and people have some disposable income – we will see this change….

Incentives generally work pretty well in the economy. So I say if you want children to learn more, give them incentives. Imagine taking every high school class and doubling its size. If one teacher costs 55,000$ and the new class size is 45, you’ve got more than 1,000$ per student to dish out according to performance. Pretty sure it would work, though we wouldn’t do it, as education is not the primary purpose of schooling.

AFAIK increasing class size has rapidly diminishing returns with respect to education quality.

There’s being RCT’s done.

Turns out paying kids large amounts for good results is close to useless. (think “$X000 and car if you get A’s in your exams!!!!”)

Paying kids small amounts for instrumental steps like reading books or behaving well is highly effective.

In a big experiment, paying kids a dollar or so per book read was spectacularly effective, far beyond any other intervention or any other financial or staff intervention trialed.

Tiny sums of money and the teacher simply asked a few questions to be reasonably sure the kid read it.

The cost for paying kids to read books was also the cheapest intervention. In terms of the national level education budget, if it was rolled out nationally it would be petty-cash level.

It’s sad that it never seems to have filtered out into education policy.

Pizza Hut has a similar program where kids get free pizza for reading a certain number of books. According to Wikipedia, studies have shown it to have little effect, and parents have justifiably criticized it for being a way to advertise in schools.

I know of experiments which paid kids around ~50$. I’m suggesting an order of magnitude more.

Children don’t respond linearly to increasing amounts of money.

Partly this is irrational but understandable- most children don’t have a concept of what it even means to have five hundred dollars; almost no parent will give a child that kind of money.

Conversely there’s a rational reason: the larger a cash prize is, the less likely the child is to get to spend it autonomously. Even if the parent doesn’t outright take the money away from them, they may take it away for practical purposes (it goes into a college fund and won’t be coming out for a period about as long as the child’s entire living memory to date). And certainly the parent is likely to try to exercise control over how the money is spent.

So expect the effectiveness of this intervention to grow with, oh, the square root of the amount of money you spend on it.

Meanwhile, the difficulties of teaching a class tend to increase with the square of the class size, because there are N(N-1)/2 possible interactions between students and some fixed percentage of those interactions are a cause of trouble at any given time. There are linear terms, but for large class sizes the square term tends to dominate.

So it’s a losing game to ‘save money’ by increasing class sizes (loosely speaking, reduce student educational benefit proportionate to square of amount of money saved) to reward students large sums financially (loosely speaking, increase benefit proportionate to the square root of the amount of money saved).

…

Another problem is that the logistics of running a class (grading, calling Timmy’s mom because he keeps throwing things, et cetera) get significantly more difficult with class size, until you realistically cannot find teachers capable of maintaining the classroom environment singlehandedly- there are only so many hours in a day and human capacity for work is finite.

I’ve long theorized that one thing that might work well would be to have large classrooms with 2-3 teachers each who specialize as “disciplinary,” “instructional,” and “support” or something… but outside special education this is rarely if ever even vaguely attempted, and in SPED it tends to be done along very different lines and with less specialization.

Bring back corporal punishment and running large classes becomes easy-peasy. Any kids who keep misbehaving get sent kicked out of the classroom, sent to detention.

Of course, that doesn’t signal well…

@Alexander Turok

That…isn’t what corporal punishment means. I mean, I’m not particularly against teachers being allowed to spank kids, but the term you used doesn’t match the examples you used.

I know. I mean in addition to it.

Of course, if you send out kids who are misbehaving, the remainder are behaving.

If the misbehaving kids keep misbehaving and never come back, it’s very Darwinian. The class without them would be very different and a lot better.

Depending on the school and the teacher, this could happen to quite a few kids. But American education believes in Mathew 18:12.

The big problem is that we’ve found that a higher high school dropout rate has problems all its own. Because it turns out that most of the kids who chronically misbehave in school and don’t stop even when you call their parents or give them detentions? Yeah, they don’t stop doing that when they get kicked out of school. And their misbehavior tends to start early enough that kicking them out puts them at a crippling disadvantage in the workforce; no one wants to hire a 18-year-old who got kicked out of middle school at the age of 13, even if they’ve reformed their behavior.

Furthermore, a lot of student misbehavior is the consequence of something that frankly isn’t the child’s “fault” in a moral-judgment sense, such as abuse, an unstable home life, or other such problems. Which makes it seem desirable to address these issues on a level higher than “you are the weakest link goodbye,” if nothing else so we’re not quite so swamped by maladjusted loonies twenty years down the road.

This is especially true in a country like the US, where the school system is as close as a lot of children ever get to having easy access to a psychiatrist or a social worker.

@Simon_Jester,

Agree with everything you write. My question is simple: is our current system helping with any of those problems? I think it’s a costly signal: we care about those kids, and putting them in a room they don’t want to be in and teaching them things they don’t want to learn is costly for us to do, thus a signal we care. I don’t think it does anything to actually help them.

Conversely there’s a rational reason: the larger a cash prize is, the less likely the child is to get to spend it autonomously. Even if the parent doesn’t outright take the money away from them, they may take it away for practical purposes (it goes into a college fund and won’t be coming out for a period about as long as the child’s entire living memory to date). And certainly the parent is likely to try to exercise control over how the money is spent.

You could put pressure on parents not to do this. Most parents don’t seize their 16-year olds incomes from working, and this would be of similar size. Some do, and some would, but these parents would be incentivized to replace incentive with direct pressure on their kids.

Everyone directly involved, myself included, believes, down to at least a meta-layer or two deep, that it helps.

You can argue cost/benefit, mind.

The basic idea is that it makes a fairly major difference whether someone has, say, a 7th grade, 10th grade, or 12th grade education when they leave high school. If you let a kid ‘nope nope nope’ out of high school by being an unruly little shit at the age of fifteen, you’ll get a lot of unruly little shits leaving high school with that 7th grade education.

But if you keep them in for another three years, you get some mixture of still-unruly-larger-shits and now-ruly-larger-less-shitty types, with something like a 10th grade education on average.

It’s still not great, arguably not even good, but abandoning the whole idea is likely to cause problems as bad or worse. I think the real priority shouldn’t be “sigh, we have to try to educate all those inferior bozos,” because the reasons for bozo-ness are so complicated that trying to attribute them all to personal inferiority is absurd.

I completely agree that we should try to educate these kids. We shouldn’t just throw them on the streets. But

1) We should try to educate them with things that they will find useful. Don’t bore them and turn them into failures by saying the only thing that counts as “education” is college prep.

2) If their behavior problems are bad, they shouldn’t be in classes with people who will lose out if they are around. It really isn’t fair to the better behaved kids.

What do you mean by “on the streets?” Are you aware that there exist jobs they could get? Worse case scenario they don’t and aren’t earning any income, which would also be the case if they were forced to attend school. If the mentality is “we need to do something to show we care,” that’s the problem. Perhaps a universal income could solve it.

Vocational ed has the same problem as higher ed. When you subsidize something, you overproduce it. If there were a need for certain skills, the market would pay to train them. Maybe there’s a failure of credit markets, in which you could solve it through subsidized loans.

Are you aware that there exist jobs they could get?

There are damn few jobs you can get at (the rapidly increasing) minimum wage if you have the skills of a 15-year-old. You can say, “Oh, well, we shouldn’t have a minimum wage” but we do, and we have to work within what’s possible.

If there were a need for certain skills, the market would pay to train them.

Need? What is this “need” you speak of? Was there a need in 1600 for a machine to pump out coal mines? The people who wanted to mine coal certainly thought so. But the Watt-Bouton steam engine didn’t come to market until 1775.

We’re at 3% unemployment. That may change if Bernie and co. send it to infinity, but for now there’s plenty of jobs.

Cutting edge innovation is hard, few could do it. Eventually someone(not employed by the government) did. This isn’t a conversation about to what degree government should subsidize cutting-edge research. We’re not talking about inventing something new, we’re talking about subsidizing something we already know who to do. If the machine had already been invented but miners weren’t using it unless the government subsidized its manufacture, I’d say it isn’t too useful.

We may have plenty of jobs, but 15 year olds aren’t allowed to take most of them. Even 17 year olds aren’t allowed to take many of them. And even if it were legal, there probably aren’t plenty of jobs for people too unskilled or too undisciplined to get through high school.

There are a limited number of full-time jobs where an unskilled 15-year-old is worth $15 an hour plus the employer’s social security tax, unemployment insurance payment, etc. Those jobs are already filled. More would not magically open up even if the unemployment rate went from December’s 3.5% down to zero.

As you know, the Bureau of Labor Statistics actually calculates six unemployment rates (U-1 to U-6; the above is the canonic U-3). They also report a labor force participation rate and an employment-population ratio, which stood at 63.2% and 61.0% for last December.

In a big experiment, paying kids a dollar or so per book read was spectacularly effective

Effective at what? Getting them to read more books? And if so, what kind of books? If it’s getting third graders to read another Berenstain Bears or Arthur book, I’m not sure how useful that is.

The reason paying kids lots of money for big results doesn’t work is probably that those big results are simply impossible. The kids may really really want the money and the car but just can’t pull off lots of As.

Having kids reading is high-status. Having them play video games or throw rocks in the streets is loss status. If a group can get its kids to read more, it raises its status in the eyes of distant observers. That’s really what this is about.

If you want economic efficiency, the education budget should be drastically cut and kids who don’t want to learn should be encouraged to leave school at age 15 and enter the workforce.

@Alexander Turok

The big problem is that the workforce doesn’t want the kind of kid who doesn’t want to learn; they won’t really want to learn to do their job, either. And in many cases the desire to not learn is caused in part by external factors that you can’t really purge from your society without making sure everyone gets an education.

It is something of a dilemma.

Sure it does, it just won’t pay them very well. We’re at 3% unemployment right? The “skills gap” and “structural unemployment” memes should be tossed in the trash.

How’s the effort to do it by giving everyone an education working out?

We’re at 3% unemployment when you count a lot of hilariously underemployed people and don’t count a lot of people who have given up trying or otherwise dropped out of the ’employable’ pool.

I don’t know how you feel about immigration, but deliberately embracing the creation of a native-born pool of low-cost extremely undereducated labor to drive down labor prices in my own country sounds like a worse idea than deliberately importing foreign low-cost labor. At least the foreign laborers had the gumption to walk 500 miles to get here instead of just crashing on their parents’ couch or something, so you’re likely to get more labor per dollar spent on them.

Hence my characterization of the phenomenon as a ‘dilemma.’ We can’t fix the roof while it’s raining, when it’s not raining we can’t find the leak, there’s a hole in the bucket, there is a crack in everything.

My point is that kicking out 20% of your student body to improve the educations of the other 80% is a recipe for excitingly different problems than we have today, not for no problems.

My own favored solution is, essentially, reform schools for chronic misbehaving students, with the option of being transferred back to general education schools if the student, well, reforms. The catch is that you have to recognize that educating the reform-school kids is a difficult and important job whose workforce legitimately has cause to ask for more money, not something to shuffle off on teachers you don’t like.

You shouldn’t count underemployed people, except in the case where they are only working 20 hours a week and want more. If underemployed means they just want a better job, well, don’t we all?

If they aren’t back in it now with 3% unemployment, the problem’s with them, not the economy.

I’m an immigration skeptic. It’s a flawed comparison because the “native-born pool of low-cost extremely undereducated labor” is already here. It’s just a question of whether they spend years 16-18 working or doing nothing productive while costing the education system a lot of money. I don’t see mandatory education at ages 16 to 18 doing much to improve their productivity thereafter.

The “only working 20 hours a week and want more” cases are among the ones I’m talking about- they count as “employed” when someone says “we have a 3% unemployment rate,” but they work the kind of jobs you need two or three of to make a living.

I mean, yes, the problem often is with them- though it’s often something a differently organized society could have fixed. The practical problem is that the more deliberately we embrace the idea “if you aren’t fitting our template gracefully you can just fuck off and become an extremely impoverished drone at the margins,” the more starkly we find ourselves developing a self-perpetuating underclass.

And the more talent we’re going to just plain waste. Because “Kids who don’t want to learn at 15” are extremely hard to tell apart from “kids who badly need psychiatric care but have parents too thick-headed to realize that.”

The former may be better off entering the workforce; the latter most likely are not.

In a society which strongly pushes everyone through high school, a high school dropout will be harshly stigmatized. Employers won’t want to hire them, even where knowledge learned in school is not relevant to the workplace.(To those who’d say it is: how do you explain why employers don’t care about high school GPA? If “skills” matter, why don’t employers care about the degree to which you learned them?) But in a society which doesn’t push everyone through high school, it will carry no special stigma. Just look at history.