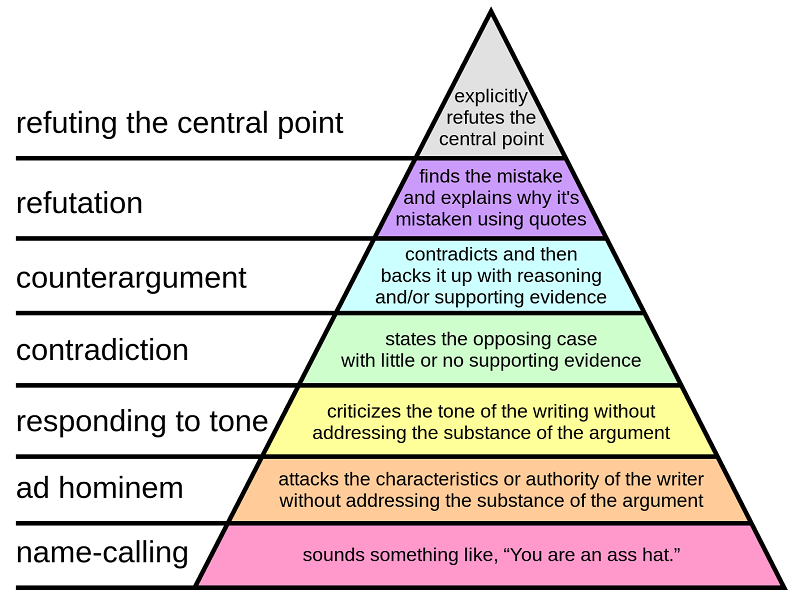

In 2008, Paul Graham wrote How To Disagree Better, ranking arguments on a scale from name-calling to explicitly refuting the other person’s central point.

And that’s why, ever since 2008, Internet arguments have generally been civil and productive.

Graham’s hierarchy is useful for its intended purpose, but it isn’t really a hierarchy of disagreements. It’s a hierarchy of types of response, within a disagreement. Sometimes things are refutations of other people’s points, but the points should never have been made at all, and refuting them doesn’t help. Sometimes it’s unclear how the argument even connects to the sorts of things that in principle could be proven or refuted.

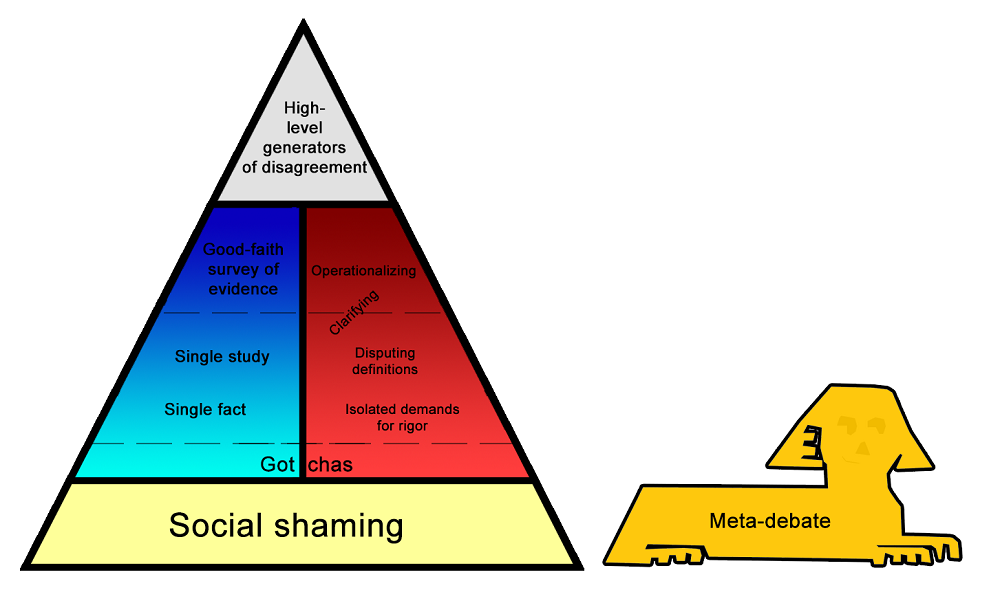

If we were to classify disagreements themselves – talk about what people are doing when they’re even having an argument – I think it would look something like this:

Most people are either meta-debating – debating whether some parties in the debate are violating norms – or they’re just shaming, trying to push one side of the debate outside the bounds of respectability.

If you can get past that level, you end up discussing facts (blue column on the left) and/or philosophizing about how the argument has to fit together before one side is “right” or “wrong” (red column on the right). Either of these can be anywhere from throwing out a one-line claim and adding “Checkmate, atheists” at the end of it, to cooperating with the other person to try to figure out exactly what considerations are relevant and which sources best resolve them.

If you can get past that level, you run into really high-level disagreements about overall moral systems, or which goods are more valuable than others, or what “freedom” means, or stuff like that. These are basically unresolvable with anything less than a lifetime of philosophical work, but they usually allow mutual understanding and respect.

I’m not saying everything fits into this model, or even that most things do. It’s just a way of thinking that I’ve found helpful. More detail on what I mean by each level:

Meta-debate is discussion of the debate itself rather than the ideas being debated. Is one side being hypocritical? Are some of the arguments involved offensive? Is someone being silenced? What biases motivate either side? Is someone ignorant? Is someone a “fanatic”? Are their beliefs a “religion”? Is someone defying a consensus? Who is the underdog? I’ve placed it in a sphinx outside the pyramid to emphasize that it’s not a bad argument for the thing, it’s just an argument about something completely different.

“Gun control proponents are just terrified of guns, and if they had more experience with them their fear would go away.”

“It was wrong for gun control opponents to prevent the CDC from researching gun statistics more thoroughly.”

“Senators who oppose gun control are in the pocket of the NRA.”

“It’s insensitive to start bringing up gun control hours after a mass shooting.”

Sometimes meta-debate can be good, productive, or necessary. For example, I think discussing “the origins of the Trump phenomenon” is interesting and important, and not just an attempt to bulverizing the question of whether Trump is a good president or not. And if you want to maintain discussion norms, sometimes you do have to have discussions about who’s violating them. I even think it can sometimes be helpful to argue about which side is the underdog.

But it’s not the debate, and also it’s much more fun than the debate. It’s an inherently social question, the sort of who’s-high-status and who’s-defecting-against-group-norms questions that we like a little too much. If people have to choose between this and some sort of boring scientific question about when fetuses gain brain function, they’ll choose this every time; given the chance, meta-debate will crowd out everything else.

The other reason it’s in the sphinx is because its proper function is to guard the debate. Sure, you could spend your time writing a long essay about why creationists’ objections to radiocarbon dating are wrong. But the meta-debate is what tells you creationists generally aren’t good debate partners and you shouldn’t get involved.

Social shaming also isn’t an argument. It’s a demand for listeners to place someone outside the boundary of people who deserve to be heard; to classify them as so repugnant that arguing with them is only dignifying them. If it works, supporting one side of an argument imposes so much reputational cost that only a few weirdos dare to do it, it sinks outside the Overton Window, and the other side wins by default.

“I can’t believe it’s 2018 and we’re still letting transphobes on this forum.”

“Just another purple-haired SJW snowflake who thinks all disagreement is oppression.”

“Really, do conservatives have any consistent beliefs other than hating black people and wanting the poor to starve?”

“I see we’ve got a Silicon Valley techbro STEMlord autist here.”

Nobody expects this to convince anyone. That’s why I don’t like the term “ad hominem”, which implies that shamers are idiots who are too stupid to realize that calling someone names doesn’t refute their point. That’s not the problem. People who use this strategy know exactly what they’re doing and are often quite successful. The goal is not to convince their opponents, or even to hurt their opponent’s feelings, but to demonstrate social norms to bystanders. If you condescendingly advise people that ad hominem isn’t logically valid, you’re missing the point.

when you do sutuff like… shoot my jaw clean off of my face with a sniper rifle, it mostly reflects poorly on your self

— wint (@dril) September 23, 2016

Sometimes the shaming works on a society-wide level. More often, it’s an attempt to claim a certain space, kind of like the intellectual equivalent of a gang sign. If the Jets can graffiti “FUCK THE SHARKS” on a certain bridge, but the Sharks can’t get away with graffiting “NO ACTUALLY FUCK THE JETS” on the same bridge, then almost by definition that bridge is in the Jets’ territory. This is part of the process that creates polarization and echo chambers. If you see an attempt at social shaming and feel triggered, that’s the second-best result from the perspective of the person who put it up. The best result is that you never went into that space at all. This isn’t just about keeping conservatives out of socialist spaces. It’s also about defining what kind of socialist the socialist space is for, and what kind of ideas good socialists are or aren’t allowed to hold.

I think easily 90% of online discussion is of this form right now, including some long and carefully-written thinkpieces with lots of citations. The point isn’t that it literally uses the word “fuck”, the point is that the active ingredient isn’t persuasiveness, it’s the ability to make some people feel like they’re suffering social costs for their opinion. Even really good arguments that are persuasive can be used this way if someone links them on Facebook with “This is why I keep saying Democrats are dumb” underneath it.

This is similar to meta-debate, except that meta-debate can sometimes be cooperative and productive – both Trump supporters and Trump opponents could in theory work together trying to figure out the origins of the “Trump phenomenon” – and that shaming is at least sort of an attempt to resolve the argument, in a sense.

Gotchas are short claims that purport to be devastating proof that one side can’t possibly be right.

“If you like big government so much, why don’t you move to Cuba?”

“Isn’t it ironic that most pro-lifers are also against welfare and free health care? Guess they only care about babies until they’re born.”

“When guns are outlawed, only outlaws will have guns.”

These are snappy but almost always stupid. People may not move to Cuba because they don’t want government that big, because governments can be big in many ways some of which are bad, because governments can vary along dimensions other than how big they are, because countries can vary along dimensions other than what their governments are, or just because moving is hard and disruptive.

They may sometimes suggest what might, with a lot more work, be a good point. For example, the last one could be transformed into an argument like “Since it’s possible to get guns illegally with some effort, and criminals need guns to commit their crimes and are comfortable with breaking laws, it might only slightly decrease the number of guns available to criminals. And it might greatly decrease the number of guns available to law-abiding people hoping to defend themselves. So the cost of people not being able to defend themselves might be greater than the benefit of fewer criminals being able to commit crimes.” I don’t think I agree with this argument, and I might challenge assumptions like “criminals aren’t that much likely to have guns if they’re illegal” or “law-abiding gun owners using guns in self-defense is common and an important factor to include in our calculations”. But this would be a reasonable argument and not just a gotcha. The original is a gotcha exactly because it doesn’t invite this level of analysis or even seem aware that it’s possible. It’s not saying “calculate the value of these parameters, because I think they work out in a way where this is a pretty strong argument against controlling guns”. It’s saying “gotcha!”.

Single facts are when someone presents one fact, which admittedly does support their argument, as if it solves the debate in and of itself. It’s the same sort of situation as one of the better gotchas – it could be changed into a decent argument, with work. But presenting it as if it’s supposed to change someone’s mind in and of itself is naive and sort of an aggressive act.

“The UK has gun control, and the murder rate there is only a quarter of ours.”

“The USSR was communist and it was terrible.”

“Donald Trump is known to have cheated his employees and subcontractors.”

“Hillary Clinton handled her emails in a scandalously incompetent manner and tried to cover it up.”

These are all potentially good points, with at least two caveats. First, correlation isn’t causation – the UK’s low murder rates might not be caused by their gun control, and maybe not all communist countries inevitably end up like the USSR. Second, even things with some bad features are overall net good. Trump could be a dishonest businessman, but still have other good qualities. Hillary Clinton may be crap at email security, but skilled at other things. Even if these facts are true and causal, they only prove that a plan has at least one bad quality. At best they would be followed up by an argument for why this is really important.

I think the move from shaming to good argument is kind of a continuum. This level is around the middle. At some point, saying “I can’t believe you would support someone who could do that with her emails!” is just trying to bait Hillary supporters. And any Hillary supporter who thinks it’s really important to argue specifics of why the emails aren’t that bad, instead of focusing on the bigger picture, is taking the bait, or getting stuck in this mindset where they feel threatened if they admit there’s anything bad about Hillary, or just feeling too defensive.

Single studies are better than scattered facts since they at least prove some competent person looked into the issue formally.

“This paper from Gary Kleck shows that more guns actually cause less crime.”

“These people looked at the evidence and proved that support for Trump is motivated by authoritarianism.”

“I think you’ll find economists have already investigated this and that the minimum wage doesn’t cost jobs.”

“There are actually studies proving that money doesn’t influence politics.”

We’ve already discussed this here before. Scientific studies are much less reliable guides to truth than most people think. On any controversial issue, there are usually many peer-reviewed studies supporting each side. Sometimes these studies are just wrong. Other times they investigate a much weaker subproblem but get billed as solving the larger problem.

There are dozens of studies proving the minimum wage does destroy jobs, and dozens of studies proving it doesn’t. Probably it depends a lot on the particular job, the size of the minimum wage, how the economy is doing otherwise, etc, etc, etc. Gary Kleck does have a lot of studies showing that more guns decrease crime, but a lot of other criminologists disagree with him. Both sides will have plausible-sounding reasons for why the other’s studies have been conclusively debunked on account of all sorts of bias and confounders, but you will actually have to look through those reasons and see if they’re right.

Usually the scientific consensus on subjects like these will be as good as you can get, but don’t trust that you know the scientific consensus unless you have read actual well-conducted surveys of scientists in the field. Your echo chamber telling you “the scientific consensus agrees with us” is definitely not sufficient.

A good-faith survey of evidence is what you get when you take all of the above into account, stop trying to devastate the other person with a mountain of facts that can’t possibly be wrong, and start looking at the studies and arguments on both sides and figuring out what kind of complex picture they paint.

“Of the meta-analyses on the minimum wage, three seem to suggest it doesn’t cost jobs, and two seem to suggest it does. Looking at the potential confounders in each, I trust the ones saying it doesn’t cost jobs more.”

“The latest surveys say more than 97% of climate scientists think the earth is warming, so even though I’ve looked at your arguments for why it might not be, I think we have to go with the consensus on this one.”

“The justice system seems racially biased at the sentencing stage, but not at the arrest or verdict stages.”

“It looks like this level of gun control would cause 500 fewer murders a year, but also prevent 50 law-abiding gun owners from defending themselves. Overall I think that would be worth it.”

Isolated demands for rigor are attempts to demand that an opposing argument be held to such strict invented-on-the-spot standards that nothing (including common-sense statements everyone agrees with) could possibly clear the bar.

“You can’t be an atheist if you can’t prove God doesn’t exist.”

“Since you benefit from capitalism and all the wealth it’s made available to you, it’s hypocritical for you to oppose it.”

“Capital punishment is just state-sanctioned murder.”

“When people still criticize Trump even though the economy is doing so well, it proves they never cared about prosperity and are just blindly loyal to their party.”

The first is wrong because you can disbelieve in Bigfoot without being able to prove Bigfoot doesn’t exist – “you can never doubt something unless you can prove it doesn’t exist” is a fake rule we never apply to anything else. The second is wrong because you can be against racism even if you are a white person who presumably benefits from it; “you can never oppose something that benefits you” is a fake rule we never apply to anything else. The third is wrong because eg prison is just state-sanctioned kidnapping; “it is exactly as wrong for the state to do something as for a random criminal to do it” is a fake rule we never apply to anything else. The fourth is wrong because Republicans have also been against leaders who presided over good economies and presumably thought this was a reasonable thing to do; “it’s impossible to honestly oppose someone even when there’s a good economy” is a fake rule we never apply to anything else.

Sometimes these can be more complicated and ambiguous. One could argue that

“Banning abortion is unconscionable because it denies someone the right to do what they want with their own body” is an isolated demand for rigor, given that we ban people from selling their organs, accepting unlicensed medical treatments, using illegal drugs, engaging in prostitution, accepting euthanasia, and countless other things that involve telling them what to do with their bodies – “everyone has a right to do what they want with their own bodies” is a fake rule we never apply to anything else. Other people might want to search for ways that the abortion case is different, or explore what we mean by “right to their own body” more deeply. Proposed without these deeper analysis, I don’t think the claim would rise much above this level.

I don’t think these are necessarily badly-intentioned. We don’t have a good explicit understanding of what high-level principles we use, and tend to make them up on the spot to fit object-level cases. But here they act to derail the argument into a stupid debate over whether it’s okay to even discuss the issue without having 100% perfect impossible rigor. The solution is exactly the sort of “proving too much” arguments in the last paragraph. Then you can agree to use normal standards of rigor for the argument and move on to your real disagreements.

These are related to fully general counterarguments like “sorry, you can’t solve every problem with X”, though usually these are more meta-debate than debate.

Sometimes isolated demands for rigor can be rescued by making them much more complicated; for example, I can see somebody explaining why kidnapping becomes acceptable when the state does it but murder doesn’t – but you’ve got to actually make the argument, and don’t be surprised if other people don’t find it convincing. Other times these work not as rules but as heuristics – for example “let people do what they want with their body in the absence of very compelling arguments otherwise” – and if those heuristics survive someone else challenging whether banning unlicensed medical treatment is really that much more compelling than banning abortion, they usually end up as high-level generators of disagreement (see below).

Disputing definitions is when an argument hinges on the meaning of words, or whether something counts as a member of a category or not.

“Transgender is a mental illness.”

“The Soviet Union wasn’t really communist.”

“Wanting English as the official language is racist.”

“Abortion is murder.”

“Nobody in the US is really poor, by global standards.”

It might be important on a social basis what we call these things; for example, the social perception of transgender might shift based on whether it was commonly thought of as a mental illness or not. But if a specific argument between two people starts hinging on one of these questions, chances are something has gone wrong; neither factual nor moral questions should depend on a dispute over the way we use words. This Guide To Words is a long and comprehensive resource about these situations and how to get past them into whatever the real disagreement is.

Clarifying is when people try to figure out exactly what their opponent’s position is.

“So communists think there shouldn’t be private ownership of factories, but there might still be private ownership of things like houses and furniture?”

“Are you opposed to laws saying that convicted felons can’t get guns? What about laws saying that there has to be a waiting period?”

“Do you think there can ever be such a thing as a just war?”

This can sometimes be hostile and counterproductive. I’ve seen too many arguments degenerate into some form of “So you’re saying that rape is good and we should have more of it, are you?” No. Nobody is ever saying that. If someone thinks the other side is saying that, they’ve stopped doing honest clarification and gotten more into the performative shaming side.

But there are a lot of misunderstandings about people’s positions. Some of this is because the space of things people can believe is very wide and it’s hard to understand exactly what someone is saying. More of it is because partisan echo chambers can deliberately spread misrepresentations or cliched versions of an opponent’s arguments in order to make them look stupid, and it takes some time to realize that real opponents don’t always match the stereotype. And sometimes it’s because people don’t always have their positions down in detail themselves (eg communists’ uncertainty about what exactly a communist state would look like). At its best, clarification can help the other person notice holes in their own opinions and reveal leaps in logic that might legitimately deserve to be questioned.

Operationalizing is where both parties understand they’re in a cooperative effort to fix exactly what they’re arguing about, where the goalposts are, and what all of their terms mean.

“When I say the Soviet Union was communist, I mean that the state controlled basically all of the economy. Do you agree that’s what we’re debating here?”

“I mean that a gun buyback program similar to the one in Australia would probably lead to less gun crime in the United States and hundreds of lives saved per year.”

“If the US were to raise the national minimum wage to $15, the average poor person would be better off.”

“I’m not interested in debating whether the IPCC estimates of global warming might be too high, I’m interested in whether the real estimate is still bad enough that millions of people could die.”

An argument is operationalized when every part of it has either been reduced to a factual question with a real answer (even if we don’t know what it is), or when it’s obvious exactly what kind of non-factual disagreement is going on (for example, a difference in moral systems, or a difference in intuitions about what’s important).

The Center for Applied Rationality promotes double-cruxing, a specific technique that helps people operationalize arguments. A double-crux is a single subquestion where both sides admit that if they were wrong about the subquestion, they would change their mind. For example, if Alice (gun control opponent) would support gun control if she knew it lowered crime, and Bob (gun control supporter) would oppose gun control if he knew it would make crime worse – then the only thing they have to talk about is crime. They can ignore whether guns are important for resisting tyranny. They can ignore the role of mass shootings. They can ignore whether the NRA spokesman made an offensive comment one time. They just have to focus on crime – and that’s the sort of thing which at least in principle is tractable to studies and statistics and scientific consensus.

Not every argument will have double-cruxes. Alice might still oppose gun control if it only lowered crime a little, but also vastly increased the risk of the government becoming authoritarian. A lot of things – like a decision to vote for Hillary instead of Trump – might be based on a hundred little considerations rather than a single debatable point.

But at the very least, you might be able to find a bunch of more limited cruxes. For example, a Trump supporter might admit he would probably vote Hillary if he learned that Trump was more likely to start a war than Hillary was. This isn’t quite as likely to end the whole disagreement in a fell swoop – but it still gives a more fruitful avenue for debate than the usual fact-scattering.

High-level generators of disagreement are what remains when everyone understands exactly what’s being argued, and agrees on what all the evidence says, but have vague and hard-to-define reasons for disagreeing anyway. In retrospect, these are probably why the disagreement arose in the first place, with a lot of the more specific points being downstream of them and kind of made-up justifications. These are almost impossible to resolve even in principle.

“I feel like a populace that owns guns is free and has some level of control over its own destiny, but that if they take away our guns we’re pretty much just subjects and have to hope the government treats us well.”

“Yes, there are some arguments for why this war might be just, and how it might liberate people who are suffering terribly. But I feel like we always hear this kind of thing and it never pans out. And every time we declare war, that reinforces a culture where things can be solved by force. I think we need to take an unconditional stance against aggressive war, always and forever.”

“Even though I can’t tell you how this regulation would go wrong, in past experience a lot of well-intentioned regulations have ended up backfiring horribly. I just think we should have a bias against solving all problems by regulating them.”

“Capital punishment might decrease crime, but I draw the line at intentionally killing people. I don’t want to live in a society that does that, no matter what its reasons.”

Some of these involve what social signal an action might send; for example, even a just war might have the subtle effect of legitimizing war in people’s minds. Others involve cases where we expect our information to be biased or our analysis to be inaccurate; for example, if past regulations that seemed good have gone wrong, we might expect the next one to go wrong even if we can’t think of arguments against it. Others involve differences in very vague and long-term predictions, like whether it’s reasonable to worry about the government descending into tyranny or anarchy. Others involve fundamentally different moral systems, like if it’s okay to kill someone for a greater good. And the most frustrating involve chaotic and uncomputable situations that have to be solved by metis or phronesis or similar-sounding Greek words, where different people’s Greek words give them different opinions.

You can always try debating these points further. But these sorts of high-level generators are usually formed from hundreds of different cases and can’t easily be simplified or disproven. Maybe the best you can do is share the situations that led to you having the generators you do. Sometimes good art can help.

The high-level generators of disagreement can sound a lot like really bad and stupid arguments from previous levels. “We just have fundamentally different values” can sound a lot like “You’re just an evil person”. “I’ve got a heuristic here based on a lot of other cases I’ve seen” can sound a lot like “I prefer anecdotal evidence to facts”. And “I don’t think we can trust explicit reasoning in an area as fraught as this” can sound a lot like “I hate logic and am going to do whatever my biases say”. If there’s a difference, I think it comes from having gone through all the previous steps – having confirmed that the other person knows as much as you might be intellectual equals who are both equally concerned about doing the moral thing – and realizing that both of you alike are controlled by high-level generators. High-level generators aren’t biases in the sense of mistakes. They’re the strategies everyone uses to guide themselves in uncertain situations.

This doesn’t mean everyone is equally right and okay. You’ve reached this level when you agree that the situation is complicated enough that a reasonable person with reasonable high-level generators could disagree with you. If 100% of the evidence supports your side, and there’s no reasonable way that any set of sane heuristics or caveats could make someone disagree, then (unless you’re missing something) your opponent might just be an idiot.

Some thoughts on the overall arrangement:

1. If anybody in an argument is operating on a low level, the entire argument is now on that low level. First, because people will feel compelled to refute the low-level point before continuing. Second, because we’re only human, and if someone tries to shame/gotcha you, the natural response is to try to shame/gotcha them back.

2. The blue column on the left is factual disagreements; the red column on the right is philosophical disagreements. The highest level you’ll be able to get to is the lowest of where you are on the two columns.

3. Higher levels require more vulnerability. If you admit that the data are mixed but seem to slightly favor your side, and your opponent says that every good study ever has always favored his side plus also you are a racist communist – well, you kind of walked into that one. In particular, exploring high-level generators of disagreement requires a lot of trust, since someone who is at all hostile can easily frame this as “See! He admits that he’s biased and just going off his intuitions!”

4. If you hold the conversation in private, you’re almost guaranteed to avoid everything below the lower dotted line. Everything below that is a show put on for spectators.

5. If you’re intelligent, decent, and philosophically sophisticated, you can avoid everything below the higher dotted line. Everything below that is either a show or some form of mistake; everything above it is impossible to avoid no matter how great you are.

6. The shorter and more public the medium, the more pressure there is to stick to the lower levels. Twitter is great for shaming, but it’s almost impossible to have a good-faith survey of evidence there, or use it to operationalize a tricky definitional question.

7. Sometimes the high-level generators of disagreement are other, even more complicated questions. For example, a lot of people’s views come from their religion. Now you’ve got a whole different debate.

8. And a lot of the facts you have to agree on in a survey of the evidence are also complicated. I once saw a communism vs. capitalism argument degenerate into a discussion of whether government works better than private industry, then whether NASA was better than SpaceX, then whether some particular NASA rocket engine design was better than a corresponding SpaceX design. I never did learn if they figured whose rocket engine was better, or whether that helped them solve the communism vs. capitalism question. But it seems pretty clear that the degeneration into subquestions and discovery of superquestions can go on forever. This is the stage a lot of discussions get bogged down in, and one reason why pruning techniques like double-cruxes are so important.

9. Try to classify arguments you see in the wild on this system, and you find that some fit and others don’t. But the main thing you find is how few real arguments there are. This is something I tried to hammer in during the last election, when people were complaining “Well, we tried to debate Trump supporters, they didn’t change their mind, guess reason and democracy don’t work”. Arguments above the first dotted line are rare; arguments above the second basically nonexistent in public unless you look really hard.

But what’s the point? If you’re just going to end up at the high-level generators of disagreement, why do all the work?

First, because if you do it right you’ll end up respecting the other person. Going through all the motions might not produce agreement, but it should produce the feeling that the other person came to their belief honestly, isn’t just stupid and evil, and can be reasoned with on other subjects. The natural tendency is to assume that people on the other side just don’t know (or deliberately avoid knowing) the facts, or are using weird perverse rules of reasoning to ensure they get the conclusions they want. Go through the whole process, and you will find some ignorance, and you will find some bias, but they’ll probably be on both sides, and the exact way they work might surprise you.

Second, because – and this is total conjecture – this deals a tiny bit of damage to the high-level generators of disagreement. I think of these as Bayesian priors; you’ve looked at a hundred cases, all of them have been X, so when you see something that looks like not-X, you can assume you’re wrong – see the example above where the libertarian admits there is no clear argument against this particular regulation, but is wary enough of regulations to suspect there’s something they’re missing. But in this kind of math, the prior shifts the perception of the evidence, but the evidence also shifts the perception of the prior.

Imagine that, throughout your life, you’ve learned that UFO stories are fakes and hoaxes. Some friend of yours sees a UFO, and you assume (based on your priors) that it’s probably fake. They try to convince you. They show you the spot in their backyard where it landed and singed the grass. They show you the mysterious metal object they took as a souvenir. It seems plausible, but you still have too much of a prior on UFOs being fake, and so you assume they made it up.

Now imagine another friend has the same experience, and also shows you good evidence. And you hear about someone the next town over who says the same thing. After ten or twenty of these, maybe you start wondering if there’s something to all of this UFOs. Your overall skepticism of UFOs has made you dismiss each particular story, but each story has also dealt a little damage to your overall skepticism.

I think the high-level generators might work the same way. The libertarian says “Everything I’ve learned thus far makes me think government regulations fail.” You demonstrate what looks like a successful government regulation. The libertarian doubts, but also becomes slightly more receptive to the possibility of those regulations occasionally being useful. Do this a hundred times, and they might be more willing to accept regulations in general.

As the old saying goes, “First they ignore you, then they laugh at you, then they fight you, then they fight you half-heartedly, then they’re neutral, then they grudgingly say you might have a point even though you’re annoying, then they say on balance you’re mostly right although you ignore some of the most important facets of the issue, then you win.”

I notice SSC commenter John Nerst is talking about a science of disagreement and has set up a subreddit for discussing it. I only learned about it after mostly finishing this post, so I haven’t looked into it as much as I should, but it might make good followup reading.

Longtime reader, first (or possibly second) time poster. I just wanted to say I’ve bookmarked and reread this article many times over the past month, and I’m still learning from it. “Arguments above the second line are rare” has become something of a catch-phrase for me, at least in my head.

This is a fantastic chart that I’d love to spread hither and yon in the hope of getting more arguments that aren’t a complete waste of time for everyone involved, but unfortunately the “t” in “Gotchas” overlaps the black dividing bar between the red and blue sections of the pyramid and makes it oddly hard to read. Any chance you could fix that?

There should be another level above the pyramid which is “Extreme humility after reading John Ioannidis”.

Given the discussions of consensus and bias, I thought it might be worth mentioning the sources of my bias against consensus before this thread vanishes.

I grew up in the middle of the destruction of a well established consensus in economics. When I was an undergraduate at Harvard in the early sixties a fellow student, who almost certainly knew nothing about me, remarked that he couldn’t take an economics course at Chicago because he would burst out laughing. I took that as a mildly exaggerated picture of the views presented to him in the, probably introductory, econ course he had taken, hence of the accepted view at one of (indeed, all but one of) the leading departments.

Within about fifteen years of that conversation, the Chicago position had become orthodoxy or near it on some of the major issues disputed between the two schools. On Wikipedia’s list of economics Nobels classified by institution, Chicago beats Harvard eleven to five (that includes one or two figures not associated with the Chicago School but excludes at least one associated with the school but not at Chicago).

My second bias comes from having political views that are far from the orthodoxy in the environment, American academia, that I have spent my life in—and observing how poor an idea most of the people sharing that orthodoxy have of the arguments against it. That goes with another story, also from my time at Harvard.

It was 1964 and I was supporting Goldwater. I got into a friendly conversation with a stranger who wanted to know how I could do so. In the course of the conversation I ran through a number of arguments for my position. In each case it was clear that the man I was talking with had never heard the argument and had no immediate rebuttal. At the end of the conversation he asked me, in what I took to be a “taking care not to offend” tone, whether perhaps I was defending all of these positions for fun, not because I believed in them. I took that as the intellectual equivalent of “what is a nice girl like you doing in a place like this?” How could I be smart enough to offer arguments he couldn’t readily rebut for views he knew were wrong, and stupid enough to actually believe them?

In the years since I have held a political position, anarcho-capitalism, considerable farther from orthodoxy than support of Goldwater was—and observed its status moving, at least in circles I frequent, from “No reasonable person could believe it” to “hardly anyone agrees with it, but it’s an interesting position worth thinking about.”

All of which may help explain why my instinctive response to being told that everyone believes X is to start looking for reasons why X might be false.

I’d expect this to be less likely in natural sciences than social sciences, because 1. the factual questions it discusses are more exact, 2. the questions are less directly related to politics, 3. there are less likely to be hidden motives. (That is, there may be hidden motives from external sources such as outside financial interests, but less likely from the scientists’ own political convictions. E.g. a leftist may be biased against claiming that redistribution hurts economic growth because he’s worries that the claim would be misinterpreted and exaggerated, but also because he actually wants redistribution even if it hurts growth; the opposite for a libertarian. A climate scientist might also be biased against making (inconclusive) claims against AGW as they could be exaggerated, but it’s unlikely that he would want to reduce CO2 emissions even if they don’t cause global warming.)

Unfortunately, this well-known cartoon suggests they might.

That depends on whether the things proposed to reduce CO2 emissions were things he also wanted to do for other reasons. I think it is clear that for many of the people campaigning for action against warming, they are. For some evidence consider this cartoon, popular, in my experience, with such people.

Here is my blog post on it.

One could argue that “Banning abortion is unconscionable because it denies someone the right to do what they want with their own body” is an isolated demand for rigor, given that we ban people from selling their organs, accepting unlicensed medical treatments, using illegal drugs, engaging in prostitution, accepting euthanasia, and countless other things that involve telling them what to do with their bodies – “everyone has a right to do what they want with their own bodies” is a fake rule we never apply to anything else.

This also seems unconvincing as an example. As a matter of fact, we do ban people from selling their organs, accepting unlicensed medical treatments, using illegal drugs, engaging in prostitution and accepting euthanasia, but every one of those examples is a bad law. We should allow people to sell their organs, accept whatever medical treatment they choose, use whatever drugs they choose, engage in prostitution if they wish and accept euthanasia. Therefore it’s reasonable to say that, consistent with believing that people should be allowed to do those things with their bodies we should also believe that people should be allowed to have abortions.

I actually feel somewhat more convinced of the pro-abortion argument now.

The argument is doubly bad. First few people who say “my body, my choice” support the proposition of fully legalizing all drugs and organ sales, which is Scott’s point.

Second pregnancy is one of the few times in which there is grey area in the fact that it isn’t just your body anymore. Some of the same people yelling ‘my body, my choice’ are supportive of preventing pregnant women from smoking and drinking.

The third is wrong because eg prison is just state-sanctioned kidnapping; “it is exactly as wrong for the state to do something as for a random criminal to do it” is a fake rule we never apply to anything else.

I don’t think this is right. I don’t fully understand republicanism, so I’m just going to express the following in monarchical terms, but I think it should port over mutatis mutandis.

The crown never does anything itself. All acts are carried out by subjects. Of course the queen does things personally, but she doesn’t do things like levy taxes or sit in judgment or go to war, and it’s been established since the Case of Proclamations in 1610 that she cannot (except perhaps in the case of going to war).

It therefore seems to me that the distinction between a state act and the act of “random criminal” begs the question. If a person does something, claiming to be acting for the crown, but the act is illicit, then the person is not a true servant of the crown, but just a random criminal. Contrariwise, anybody may perform a “citizen’s arrest”, so what seemed to be a kidnapping might turn out, on closer examination, to be a lawful arrest. The question of whether the arrest is lawful does not depend on whether the arresting agent is a crown employee.

The relevant distinction is not between crown acts and the acts of subjects. To say so would violate the principle of equality before the law. The relevant distinction is between lawful and unlawful acts.

This is illustrated if you consider that really the analogy ought to be saying that “prison is state sanctioned unlawful imprisonment”.

What is expressed by saying “capital punishment is state sanctioned murder” is that capital punishment can never be lawful. All definitions of murder includes the element “unlawful”. On the other hand, it seems clear that capital punishment would satisfy the other elements of the definition (since we no longer have the concept of “outlaws”, the convicted criminal remains under the queen’s peace).

The problem with saying “capital punishment is state sanctioned murder” is that it tends to obscure the real debate: it generates more heat than light. If one says, “capital punishment can never be lawful”, it’s clear where the real debate is. The proponents of capital punishment believe (wrongly, in my view) that it can be lawful.

The problem isn’t that it’s an isolated demand for rigour, because it’s perfectly correct to say that otherwise unlawful acts do not become licit when carried out by the state.

This hinges on whether murder is only a legal definition.

If kidnapping only a legal definition? Is it possible to be kidnapped in a country with no laws about kidnapping? If someone in one of those countries abducts you and holds you for ransom is it fair to declare that it’s not “really” kidnapping.

If you abduct, slaughter and eat a prostitute in a country lacking any coherent government are you a murderer?

Or

Lets imagine I’m best buddies with a dictator , lets say I was roomies with Kim Jong Un at uni.

Now, I convince him, as the lawful leader of the country who legally has the right to make or remove laws that I should have an exception in law. (I am not an expert on NK legalities but lets assume he legally can under the law of the country)

He writes an exception into law such that I’m exempt from being charged with murder as long as I avoid powerful or rich people and their families.

If I then go on a gleeful slaughter spree am I not a murderer?

To bring it back to your example, if I’m in a country where the government has collapsed and am thus stateless, if I handcuff someone and lock them in a cell in my basement am I a kidnapper?

How about if I saw them doing something wrong first? How about if I think that thing is wrong but they don’t?

If I make a citizens arrest and the cops never show up to collect the person am I a kidnapper if I lock them in a cell in my basement and otherwise treat them as the police would if they were in a cell? I schedule a “trial” for a few months down the road and set a “bail” that they or their kin must pay if they want them released before trial. If they don’t turn up for the trial I keep the bail money.

Some might call that kidnapping and ransom if done by an ordinary citizen.

many people don’t believe you have the right to grant rights to others that you don’t yourself have. If you don’t have the right to kill me if you think I’ve done something wrong then they don’t believe you have the right to nominate your mate Bob as the official executioner such that when he cuts my head off it doesn’t count as murder.

Personally I don’t really subscribe to that worldview, there’s a practical side that in reality laws tend to come from the point of a sword without much coherent philosophical backing though that leaves the lines between murder/execution, imprisonment with bail/kidnapping with ransom kinda fuzzy. It feels unsatisfying to say that the difference depends on whether the person/group doing it have enough guns and power to be the defacto government in the area where it happens.

This isn’t an exact match, but it turns out that Hanson blogged about

meta-discussion issues closely related to this blog article today

http://www.overcomingbias.com/2018/05/skip-value-signals.html

Nitpick: It’s not that “97% of climate scientists think the earth is warming,” it’s more like “97% of experienced climate scientists, those with at least 20 published papers, find humans are causing the Earth to warm via greenhouse gases, though some estimates run as low as 91% and there is less consensus among those who have published fewer papers (the simpler question of whether Earth is warming is not in dispute, although a small minority challenge the quantity of warming)”. Several studies have been done, see details here.

I believe the original source of the 97% figure was Cook et. al. 2013. Their 97% was for humans as one of the causes of warming—the example for one of the categories that went into the 97% used the term “contributed to.”

I suspect your “at least 20 published papers” is Anderegg et. al. If you look at the webbed supporting information you discover that of their initial group of climate researchers about a third were in the unconvinced category. It was after they reduced the initial 1372 researchers to the top 100, defined by publications, that they got a figure of 97%.

Note also that they were classifying researchers not by what they said about climate but by whether they were in one or another of various groups, such as signatories to statements on one side or another of climate issues. About 2/3 of the people they classified as “convinced by the evidence” were classified that way because they were IPCC AR4 Working Group I Contributors. I don’t think you can assume that everyone who contributes to the IPCC report agrees with the particular claim (“anthropogenic greenhouse gases have been responsible for “most” of the “unequivocal” warming of the Earth’s average global temperature over the second half of the 20th century”) that the authors are talking about.

It isn’t necessary to believe/suspect what my sources are. Simply click the link and read the bullet points (I’m the author). In particular I’ve mentioned nuances regarding Cook 2013 that you might not be aware of.

I had not seen your claims about Anderegg 2010 before so I had another look.

This is my second time reading the paper and it struck me that no consensus percentage was provided for the full 908 researchers who had their names on at least 20 papers. It stops after saying that “The UE [unconvinced by the evidence] group comprises only 2% of the top 50 climate researchers as ranked by expertise (number of climate publications), 3% of researchers of the top 100, and 2.5% of the top 200”. For the whole 908 one must calculate manually from the numbers: (N[CE] = 817; N[UE] = 93). The numbers should add up to 911 (since 3 researchers were in both groups) but somehow add up to 910 instead. Anyway, if we assume (unlike Anderegg) that the 3 researchers in both groups are actually UE (it’s quite plausible that certain people contribute to the IPCC report but publicly disagree with its core conclusion), that gives us 90% [89.8% – somehow miscalculated this first time]. Very interesting, and roughly consistent with results from that AAAS survey showing 93% consensus, and Verheggen 2014 (91% of the ~467 respondents with the most publications).

I also checked your second claim about “2/3” – it’s not in the paper itself so I went to “SI” (supplementary info) which links to more detailed info here. I verified that you’re correct. Evidently, Anderegg is not an ideal source.

A few things.

First-

Personally, I actually do consistently treat people who do violence on a consistent ethical basis, and there are some libertarian/anarchist types who follow the same ethical reasoning.

Second-

I think there can be legitimate cases about not legitimatizing discourse that don’t serve the “shaming/gang sign” function you’re talking about. As a recent example, in a facebook group called Beyond left/right politics or something like that, there quite a few posts about understanding Neo-Reactionary perspectives. In the modern age where something like the “incel” movement can go from fringe of fringe to relative mainstream, the media in the interest of shaming can make fringe ideologies quickly go viral, and people taking up new reactionary politics in response to the intersectionalist left, I think there could be a legitimate argument that increasing the exposure of fringe ideologies is genuinely a bad idea.

Third-

Increasingly, I find myself frustrated by the incredible inferential distance between myself and so many people. We can understand how conversation and debate function, but how to we use this knowledge to communicate with others who do not?

These days, I find so much of what i want to express requires long explanations of concepts and frustrating attempts to ask the right questions to figure out what the other person understands and how they are thinking and the best way to explain it to them and how I need to unpack the linguistic traps that limit their thought, and most people just don’t have the patience for that or want to have their world view deconstructed just to have a conversation with me.

The more rationalist I become,the more like I feel I need something like the metaphor language of Darmok to communicate efficiently. And the more difficult it becomes to actually communicate with the majority of people.

Curious that I see some similarities and coincidences between both pyramids, and Kohlberg’s stages of moral development in the sense that as one travels higher, greater cognitive load and reasoning skills are required. If you don’t want to read the rest of this post, the tl;dr is that the six stages, (and stage 4.5) seem to map on the levels of Scott’s pyramid well, and you can probably see this by putting up Scott’s diagram and the six stages side by side.

To begin, Scott divides the pyramid into three sections based on dotted lines, similar to Kohlberg’s three sections on Pre-Conventional, Conventional, and Post-Conventional morality. The bottom of the pyramid basically represents the first two minutes of this, and should be avoided if you’re trying to persuade. Social shaming seem to map well to Obedience/Punishment: One is trying to reinforce a base level punishment to convince the other not to make the argument, or trying to get the other to rationalize based on obedience/punishment ideas rather than the merits of the argument. Once we elevate to Gotchas, we’re at stage 1. Gotchas are still Pre-conventional, as the focus of the Gotcha, as Scott says:

Gotchas! Map similarly to primitive self-interest. One says a Gotcha not because its a compelling argument, but because one is trying to boost their individual reputation at the expense of the other (Hey y’all, remember that time I made so-and-so look like an idiot) and not considering how it actually enhances the argument space at all.

Once we go beyond the first dotted line, we’ve now gone into Conventional territory. In this sense, single facts or demands for rigor map somewhat into stage three social consensus motivations “I am providing this anecdote/piece of information because I believe it will appeal to your considerations” or “You believe in bodily autonomy, so how can you support thing-that-goes-against-it”. While these are still considerably weak, they are a significant improvement over Pre-Conventional arguments/reasoning.

The next level of evidence: Studies and disputing definitions, shows and enhancement over the previous level of single facts and isolated rigor, in the same way that stage 4 maps over stage 3. Just as stage 4 morality/reasoning not only looks at social consensus, but also norms and practical limitations for the functioning of society. A scientific study is no longer just “I am providing this to appeal to your considerations” but “I am providing this to appeal to your considerations, and it follows conventions that will allow you to replicate the results” similar to how Laws are used to codify norms to make behavior more predictable. Similarly, arguments over definitions try to improve the conventions of words used, and appeals to prior authoritative sources of language rather than a personal interpretation of contradiction (i.e. “You claim to be for bodily-autonomy, which could mean this-thing, and this-thing contradicts thing-that-goes-against-it which you support”)

A further coincidence I find, mentioned in the Wikipedia page:

Scott similarly puts clarifying on the dotted line between the middle and highest thirds of the pyramid, while the 4+ stage straddles Conventional and Post-Conventional morality/rationalizing. The four plus stage according to Kohlberg, looks at dissatisfaction with social systems and a desire to reform them (or at least understanding their limitations.) Similarly, clarification builds on disputing definitions, but this time tries to do things like Taboo the words or remove an appeal to the authoritative basis of the word, and instead get down to the details of what is being argued.

Once we get past the second dotted line, we’re now into Post-Conventional morality, or stages 5 and 6. Kohlberg believed most people developed to stage 4 and remain there for most of their lives. Similarly, as Scott states, getting into the top tiers of the pyramid isn’t easy (requiring some moral decency, intelligence, and knowledge of philosophy)

Operationalizing and Evidence Surverys map well onto Stage 5 morality. Similar to how people with stage 5 reasoning/morality recognize that there are numerous perspectives that contradict each other and so complex meta-laws or mechanisms/social contracts are needed to reconcile conflicting desires. Good faith surveys of evidence try to not only look at multiple studies, but also try to look at studies that come up with different conclusions, to possible narrow down what is true (“these things appeal to some of your considerations, but the whole body of science rejects these others”) Operationalizing not only focuses on definitions, but also establishing goal posts, and rules for how to reach them. The

functions as a sort of social contract for argument (“I will reconsider or apply the term bodily-autonomy in these circumstances”)

What’s also interesting since the wiki page mentions:

Which also doubles back to what Scott was saying about Gotchas! A Gotcha! has the potential to be a good point with mental effort (“Studies show background checks don’t improve plus here’s other studies on criminal subversion of rules…” vs “If guns are outlawed only outlaws will have guns!”) but the motivation and effort is different. To give an example of Kohlberg’s idea, a stage 2 person’s reasoning for evading taxes might be “This tax takes away my money. I prefer to keep my money and I know how to get away with it”, wheras a stage 5/6 person’s might be “This tax is unfairly assessed and enforced, and I plan to show how one can evade it and am ready to go to jail if prosecuted. Helping others evade it creates a more equitable application of the law (no-one is getting taxed) and both actions reinforce publicity behind it, making it more likely citizens will petition to have it removed” or just consider Colbert’s abuse of SuperPAC rules vs why your regular politician might be motivated to create a SuperPAC.

Finally we reach the apex of Kohlberg’s stages and Scott’s pyramid: Universal Ethical Principles and High Level Generators of disagreement, respectively. Both claim the highest stages are elusive, and both again, can be confused with lower levels of disagreement. They also seem to intertwine in a certain way. In Scott’s case, the high level generators could map to what would ostensibly be, stage six individuals trying to reconcile their own universal principles (“Unlike other compelling cases for regulating this-bodily autonomy-thing, I’ve seen other cases where regulating-this-bodily-autonomy-thing backfires, and maintain a general heuristic of not regulating-bodily-autonomy-things”) or stage 5 individuals briefly coming to stage 6 reasoning when evaluating their own positions on issues. Likewise, to get to stage 6, you basically have to internalize high level generators of disagreement within yourself to get to a rational and consistent base of ethics that you follow. A stage 6 person’s rationale for opposing gun control isn’t “a compelling argument that guns support individual liberty, social contracts and opposing tyranny of the government.” A stage 6 person would oppose gun control because they internalize high level generator arguments for individual liberty, social contracts, and opposing tyranny of the government, recognize how guns could both be used to support (self-defense) and subvert (crime) those high level generated principles, and developed a mental calculus that supports less government control of guns.

On the other hand, maybe I’m just seeing pyramids everywhere

Darmok and Jalad at Tenagra. Shaka, when the Walls Fell. Darmok,His Eyes Open.

Ekaku’s instruction with one hand; Tolkien translating Beowulf; Darwin reading Wallace’s letter;

I think one needs a separate pyramid for PO. The lowest is social shaming or even expression of hatred.

One level higher a basic friend or foe expression.

One level higher a more accurate social categorization, like you belong to group A me to B and we are neither arch-enemies nor arch-allies, these groups tend to get along but sometimes clash.

One level higher an empathic understanding: what life experience, emotion or memory made you feel about the topic the way you do? I said feel, not think. They are different things. I can think a free market is a good thing or a bad thing and bring up many rational TO arguments. But the feeling aspect is that one defender of the free market is detached while another is passionate. While the first may have arrived to it just by thinking and can be convinced otherwise, the second has that passionate emotion from somewhere. This is what is to find out empathically. Maybe a regulation destroyed his dads business and he killed himself. Once you know that, you understand why he cares so passionately about the issue.

So it is like (shittiest asciii art ever)

/ empathy \

/ subgroup \

/ friend or foe \

/ shaming or hatred \

Also, having figured it out, or at least I think I partially did, now I feel like PO is something any intelligent TO person would learn in three weeks if he cares to do so and then go back to learn other TO things. Sorry if I am an ass, probably I am. But PO sounds like something simple and intellectually unchallenging… quickly learnable…

Sorry again. Just one remark. There is Toastmasters. I have seen people go from unintelligible, shy mumblers to actually decent, understandable and likeable public speakers in something like 3 sessions, 3 x 10-20 min talking + feedback. OK that is just one element of PO but I sincerely feel like we could teach people in something like 120 hours how to function socially like an okay PO person…

There is some scattered discussion here about how important clarification is.

An observation, however: Clarification almost never works.

Okay, we agree that a flitchet is a zomp and a frim, rather than a tock and a frim.

What do THOSE words mean, however?

We greatly overestimate how much context we share; imagine, for a moment, trying to have a conversation with someone in a foreign language; your dictionary is composed of the meaning of the words as defined by Conservapedia; theirs, Wikipedia. And you can’t consult each other’s wikis.

That is closer to the true problem. And even that greatly underestimates the difficulty involved.

Communication seems to work because for most cases, the differences are trivial; if I ask you for an apple, and you bring me a Granny Smith when I was expecting a Red Delicious, I can blame myself for being insufficiently specific, and be more specific in the future. Apparently we can communicate, even if your default conceptualization of an apple differs from my own. But an apple is a concrete thing we can point at, and even if there are fuzzy boundaries on our conceptualizations – maybe a hyrbid satisfies your definition but not mine – we can ultimately use reality itself as an objective communication device, and demonstrate our meaning with examples and exceptions.

Anything too abstract to be pointed at? Forget it. There is no common context, and no means of establishing one. Mathematics might be the closest thing we have to such a context, but the myriad interpretations of quantum physics demonstrates that even mathematics cannot provide a true context of meaning.

This is why shared context is really valuable for conversations. A roomful of economists will have a large set of shared concepts and internal mental models and definitions and approaches to thinking about problems. A given economist may think some of those concepts aren’t meaningful or some of those models are not very useful, but he will still understand what they mean. And so a discussion can take place within that shared understanding and context.

I think you left out the highest form of disagreement: betting.

Being the highest form, it is impossible to find unless the stars perfectly align.

Betting in most cases constitutes Operationalizing. You’ve agreed on a set of goal posts for whether something is-or-isn’t and have established a stake of money as the enforcement of it. In the case where you bet heads-or-tails and end up with the coin landing on its edge you’ve veered into higher generators of disagreement, and possibly a 7th unknown tier.

Good post. I can find nothing in it I disagree with.

I would like to state for the record that I’m willing to change my mind on any and all issues where someone can convince me that the other side better increases the ability of all people to sit quietly and contemplate their humanity as much as possible. I would happily become a capitalist pro-life Christian if I genuinely believed that it would lead to more blissful OMMMMMing instead of less.

Conversely, I think I do in fact assume that people who disagree with me have their facts straight and that they are trying to do good as they define goodness. It’s just that their definition is anti-OMMMMM instead of pro-OMMMMM.

I had a weird reaction to this post. Namely:

(1) All the kinds of arguments mentioned here are correctly defined, categorized, and pyramid-ized.

(2) Nothing here bears any resemblance to the way I normally argue.

When I argue, it doesn’t often seem to be about definitions or evidence. Normally, hearing my opponent’s side on either of those points wouldn’t greatly surprise me or shift my position. Instead, my impression is that I normally do one or more of several things:

– Bring in examples / motivations / relevant points from my own experience

– Try to present “point of view” / “worldview” / context so others understand where I’m coming from

– Attack crucial points of opposing arguments that seem fundamentally wrong in how they think about the issue

In other words, something roughly like what I’ve been doing so far in this comment. Didn’t come off as so weird, did it?

I’d propose that we should make like the FDA and add more vertical slices to the pyramid. “Factual evidence” and “definitions” don’t do enough to capture the entirety of a dispute. Some tentative suggestions of possible categories would be “personal relevance” (why do I / should people care about this), “outcome evaluation” (if it’s a policy question, we may have legitimately different visions of what’s a good / bad outcome), and “perspective / worldview” (are there real differences in how we frame / approach the issue– this goes toward addressing Chesterton’s Fence).

Yes, it’s possible to cut those categories down until either they fit in “evidence” or “philosophy” or just get thrown out into the Sphinx– if you rationalize hard enough. But part of my point is that most people don’t break it down into just “evidence” / “philosophy” mentally. And it’s not clear how one would argue, within this framework, that they should.

I don’t think saying people can’t be against something they benefit is A. necessarilly isolated or B. a demand for rigour.

Taking the B. then A.

B. It’s a mostly* stupid argument rather than a demand for rigour. It’s a stupid argument in that it doesn’t follow you should be against things that you benefit from. Whereas a demand for rigour is, to my mind at least, more to do with asking for more or better evidence or a higher bar of proof or better logic/argument.

A. It can be applied pretty consistently by people. Plenty radio talk show hosts and people who think like them, would apply it to capitalism, the class system, unions, sexist culture (eg female acters “benefitting” from being objectified) and loads of other stuff.

*It obviously doesn’t follow that something that benefits you is something you should support, as it might be bad for other people and you might be nice or you might benefit more from something else. But I say mostly because, at times, the real meaning behind it can be, “you’re a hypocrite as you choose to do something that you say you’re against” or “you’re being disloyal to people you owe loyalty to”. Agree with these or not, they follow from some people’s starting assumptions (you should be loyal to group x, you should not do something that you’re against if you have the choice not to), so aren’t stupid, at least in the sense I’m using stupid here.

“Truth-seeking” and “ideology normalizing/advancing/implementing” are different pyramids. While social shaming is at the bottom of the truth-seeking pyramid, it’s at the healthy middle of the ideology-normalization/implementation one. Be careful not to mistake the tactics used to advance a political position, with the rationality used to arrive at one.

As others have mentioned, when someone responds using tactics low on your truth-seeking pyramid, its not to defeat your argument, it’s to defeat you. This is only “bad” from the perspective of truth-seeking being your goal. But truth seeking is not everyone’s goal, at least not all of the time (it is certainly not a terminal goal for myself). Sometimes the point is not to convince you, but to demonstrate shame/ridicule/solidarity against you. These social demonstrations are often more effective tactics at policy and norm implementation than truth-seeking. This is because I don’t need your consent to advance policy, I just need a majority of observers to the conversation to be on my side.

This is the “why” of social shaming- its an irrational behavior in truth-seeking sense, used as a rational tactic in the ideology-advancement sense. I get that it sucks to be on the receiving end of it, but there’s a good reason for its widespread social prevalence.

Good insight. Sad in what it tells us about our social conditions – that most people are willing to steamroll those they disagree with to either impose their will on unconsenting parties or protect their own interests from the same.

An underlying cultural consensus of “live-and-let-live”, which actually defuses the need for a lot of high-stakes political gamesmanship, is sorely lacking in the “land of the free”.

What sphinx of sentiment and ad hominem bashed open their skulls and ate up their brains and imagination?

I don’t think that’s a fair move to make. It sounds an awful lot like the genetic fallacy. Good research is good research. GMU scholars do get published in mainstream outlets, which means that their research has passed through the peer-review system. This isn’t a perfect system, of course, but I think it indicates that the research in question is worth being engaged with by other reasonable people.

The only way you can determine if a particular academic output is good or bad is to actually read it. Knowing that it was produced by a Koch affiliated scholar might give you some reason to doubt it, but that should only further encourage you to read the article, book, etc. in question.

An old example of what may have been donor influence over a different university in the same state, and with roughly the opposite slant.

I think “be convinced” would be more precise/accurate/universal than “learn” here.

I don’t believe in double-cruxing. It has one of the same problems that bets have–you’ve basically told the other guy “you don’t need to refute the spirit of my argument; you just need to refute my literal words”, which will lead to your opponent looking for trivial mistakes in how you presented your argument rather than real refutations.

“If you can name one country where Communists were elected into office, never set up an authoritarian government, and were peacefully removed from office, I’ll believe that Communism is okay.”

“The Republic of San Marino (population 14000) had a Communist government between 1945 and 1957. I win!”

“But I meant a good-sized country.”

“Tough. You agreed that you were refuted if I showed you an example and you didn’t say ‘good-sized’ then.”

. . .

“I’ll believe in miracles if you show me a case where scientists studied something like a regrown limb and positively concluded it was real.”

“Here’s an example. It’s from the 19th Century.”

“I didn’t mean that. I generally don’t trust scientific experiments on touchy subjects made that long ago.”

“You wanted an example, I gave you one. Better start believing in miracles.”

Sorry if I’m off base here– I’ve never done a double-crux myself– but isn’t what you describe more like “single-cruxing”? The person you’re arguing against doesn’t have anything on the line.

A more realistic double-crux of your first example might be: “Communism is okay” reduces to “Communism doesn’t reliably lead to authoritarianism” reduces to “there are good historical examples of non-authoritarian communist societies” etc., where if there *aren’t* good examples, your opponent agrees that this would weaken their opinion that Communism is okay.

More generally, it seems like “If the opposite were the case, that wouldn’t change your mind” should be a valid refutation of any claim to “win” a double-crux.

Yes, those are only single cruxes. Double cruxes are one of them on each side, which doesn’t help–they both have the same problem, and not only that, they give the advantage to uncharitable sides who are more willing to go against the spirit of the point when necessary.

I don’t think that’s true either. It has to reduce your confidence in the result somewhat, but it may not reduce it by enough to matter. If the disputed issue is “it is possible to put a man on the moon”, one example of putting a man on the moon is going to do a lot more to confirm it than the opposite of that is going to disconfirm it.

OK, yes, I see the difficulty of applying double crux specifically to claims of the form “X is possible / X exists”. I don’t think this constitutes a generalized objection to double-cruxing as a tool for resolving arguments, though.

That’s not the only case that has a problem; it’s just one where the problem is unusually obvious. Consider the disputed issue “Bill Gates is a Martian”. Showing that he has one nonhuman trait is a lot better evidence for that than showing that he has one human trait is evidence against. (This is not of course the exact opposite, which is “he has no nonhuman traits”, but it’s going to be what will be provided as evidence in arguments.)

But that’s irrelevant to my first objection, which is that your opponent can pick on a deficiency in your wording or something you forgot to mention that doesn’t really have any bearing on what you’re trying to prove. If I say that I’d believe in miracles if you proved that someone could walk on water, and you then gave me an example of someone walking on ice, that fits my literal request but only because I wasn’t specific enough. If I don’t then go on to believe in miracles, you shouldn’t be able to claim that I reneged on my agreement.

If the double crux exercise falls apart because the original proposition is poorly phrased, or not specific enough, or open to lawyerly interpretations, and/or the counterparty exploits that for a technical “win”, all that signifies is it was a bad formulation of the double crux to begin with – Garbage-in, garbage-out – and that the counterparty isn’t acting in good faith, but merely looking to score some kind of cheap win on a technicality, which defeats the purpose of the exercise.

Both parties have to be of the mindset that the reason they’re doing a double crux is to refine their own beliefs and achieve greater clarity. In your example, one of the agents clearly doesn’t share that objective – they’re still in the “gotcha” frame. A good faith counterpart would actually suggest a better crux proposal if the one offered was too weak.

If both parties have that mindset, do you need to be doing the exercise?

“The shorter and more public the medium, the more pressure there is to stick to the lower levels.”

This should be emphasized more. I think it’s the primary reason most internet debates are stupid.

– In a big internet forum or comment section, if you post a two-page reply, nobody is going to read it. Often there is a popular one-sentence argument that sounds nice but is (IMO) wrong, but the proper counter-argument takes pages. Or there is a one-sentence counter-argument, but it makes you look X (racist/communist/…), not only getting you attacks, but also making most people ignore your argument — and explaining why your argument doesn’t mean you’re X (or why being X doesn’t mean your argument should be ignored) takes pages. Even if you’re intelligent, decent, and philosophically sophisticated, your choices are posting a one-sentence gotcha, or ceding the territory to your opponents.

– It’s not worth spending an hour to convince a few faceless internet strangers out of millions who hold a view you oppose (just to start from square one when someone else posts the same view).

– It’s not worth the effort particularly when you can’t even be sure they even read your counter-arugment. Or that, if they read it and they still disagree, they’ll post a counter-counter-argument you can continue to argue against, rather than deciding they are not willing to spend more time on the debate, and quit it, continuing to hold their view.

– Internet discussion often (more than 10%) has actual arguments. But when a proper debate could be dozens of argument — counter-argument iterations, most of the time only the first few are made, over and over again. (E.g. (1) Women make 77% of what men make. (2) But they choose various jobs in different proportions.) Most internet venues don’t facilitate proper back-and-forth debate (e.g. on this site you can’t get notifications when someone replies to your comment), and you don’t get punished for posting argument (1) (that has already been made 100’000’000 times) without attempting to address (2) (which has been made 40’000’000 times in reply).

Another big one is that we have to get an opinion from a limited amout of information. Even if you’re intelligent, decent, and philosophically sophisticated, you don’t have enough time to make a full survey of evidence on all issues you’re supposed to have an opinion on (for example, because they matter when deciding who to vote for). So, often the best you can do is listen to a few opinion leaders, and try to guess which one is the more likely to tell the truth. At this point an argument like “Senators who oppose gun control are in the pocket of the NRA” becomes relevant, since it increases P(senators oppose gun control | gun control is right) and decreases P(gun control is wrong | senators oppose it).

Yes. This.

Your sub-reasons are all plausible, but I’ll add one more proposal. I suspect this is in fact the largest contributing factor. In internet discussions, most of the poster’s satisfaction comes from the act of writing and posting, not any subsequent interaction.

I have no clear theory as to why this is so. If you pressed me for a guess, it would probably be “something something superstimulus”.

On the other hand, if you accept the above point, it immediately makes clear why and how internet discussion fails to create productive arguments. And the answer is very much consistent with my personal experience.

I don’t really think so. On a forum where I’m more likely to have feedback that I’ve convinced someone (or at least that they’ve considered my arguments), I feel more inclined to put effort into making good arguments.

Noam Chomsky made exactly this point about political talk shows once. Basically, the time slot and format allows for only very conventional arguments that won’t take much time because they’re basically what everyone is already expecting. Trying to make a case for an unconventional view of anything is basically impossible–there’s not time to explain anything very complicated before the next commercial break.