0. Introduction

I grew up in the 90s, which meant watching movies about plucky children fighting Pollution Demons. Sometimes teachers would show them to us in class. None of us found that strange. We knew that when we grew up, this would be our fight: to take on the loggers and whalers and seal-clubbers who were destroying our planet and save the Earth for the next generation.

What happened to that? I don’t mean the Pollution Demons: they’re still around, I think one of them runs Trump’s EPA now. What happened to everything else? To those teachers, those movies, that whole worldview?

Save The Whales. Save The Rainforest. Save Endangered Species. Save The Earth. Stop Slash-And-Burn. Stop Acid Rain. Earth Day Every Day. Reduce, Reuse, Recycle. Twenty-five years ago, each of those would invoke a whole acrimonious debate; to some, a battle-cry; to others, a sign of a dangerous fanaticism that would destroy the economy. Today they sound about as relevant as “Fifty-four forty or fight” and “Remember the Maine”. Old slogans, emptied of their punch and fit only for bloodless historical study.

If you went back in time, turned off our Pollution Demon movie, and asked us to predict what would come of the environment twenty-five years, later, in 2018, I think we would imagine one of two scenarios. In the first, the world had become a renewable ecotopia where every child was taught to live in harmony with nature. In the second, we had failed in our struggle, the skies were grey, the rivers were brown, wild animals were a distant memory – but at least a few plucky children would still be telling us it wasn’t too late, that we could start the tough job of cleaning up after ourselves and changing paths to that other option.

The idea that things wouldn’t really change – that the environment would neither move noticeably forward or noticeably backwards – but that everyone would stop talking about environmentalism – that you could go years without hearing the words “endangered species” – that nobody would even know whether the rainforests were expanding or contracting – wouldn’t even be on the radar. It would sound like some kind of weird bizarro-world.

Just to prove I’m not imagining all this:

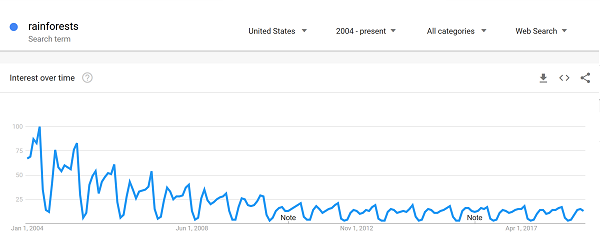

This is the volume of Google searches for “rainforests” over time. It goes up each year when school starts, and crashes again for summer vacation. But on average, there are only about 18% as many rainforest-related searches today as in 2004.

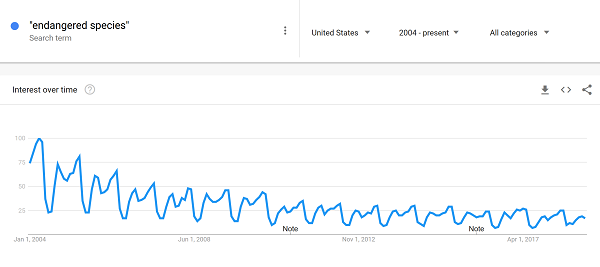

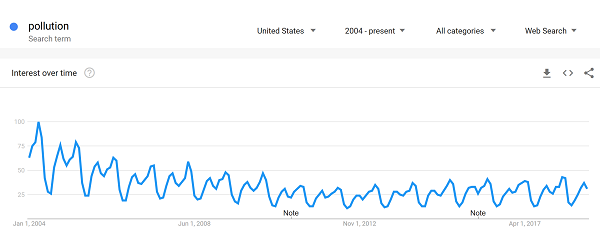

“Endangered species”, 25%

“Pollution”, 43%

And these are just since Google started tracking searches in 2004. The decline of 90s environmentalism must be even bigger.

So what happened?

Every so often you’ll hear someone mutter darkly “You never hear about the ozone hole these days, guess that was a big nothingburger.” This summons a horde of environmentalists competing to point out that you never hear about the ozone hole these days because environmentalists successfully fixed it. There was a big conference in 1989 where all the nations of the world met together and agreed to stop using ozone-destroying chlorofluorocarbons, and the ozone hole is recovering according to schedule. When people use the ozone hole as an argument against alarmism, environmentalism is a victim of its own success.

So what about these other issues that have since fizzled out? Did environmentalists solve them? Did they never exist in the first place? Or are they still as bad as ever, and we’ve just stopped caring?

1. Air And Water Pollution

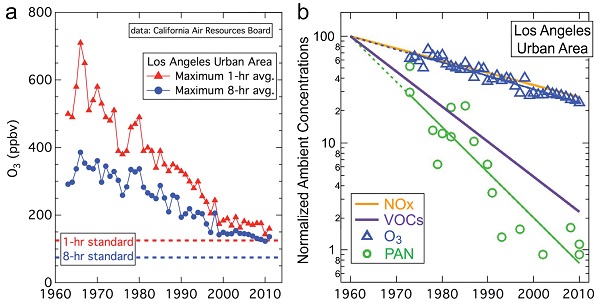

Have you seen what Chinese cities look like on a smoggy day? Trick question: neither have the Chinese. The US used to be like that. I grew up near Los Angeles during the 1990s. My mother tells the story of a time when I was very young and my grandparents came to visit from the Midwest. “It reminds us of home,” they said, “it’s so flat.” “We’re surrounded by mountains”, my mother told them. We were. You couldn’t see any of them.

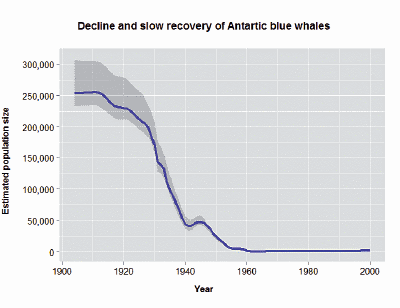

Environmentalists crusaded against this. Here are the results:

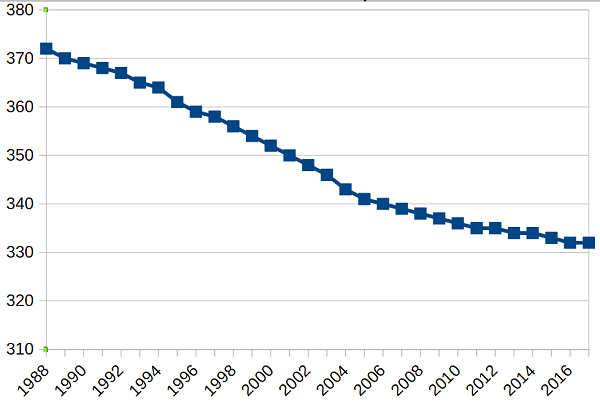

A lot of the credit goes to the Clean Air Act, passed in 1963 and tightened in 1990. Along with its more visible (pun intended) effects, scientists suspect it has prevented about 200,000 deaths from lung disease and a host of other cases of asthma, bronchitis, and even heart attacks.

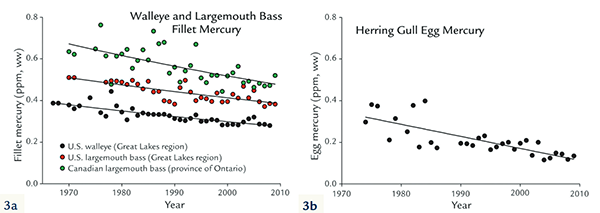

It’s hard to find great data on water because there are so many different kinds of water and so many different ways it can be polluted. But just to choose a random very bad thing, here’s mercury levels in Great Lakes fish:

I don’t know of anyone claiming this is anything other than a response to stricter environmental laws.

As a result of these victories, people are no longer as concerned about air and water pollution. From Gallup:

This seems like a clear case of good work.

Verdict: Environmental movement successfully solved this problem.

2. Acid Rain

Acid rain is a combination of rain and pollution which gets very acidic and destroys plants and structures. It was a staple of very early 90s environmentalism, and understandably so: the prospect of acid falling from the sky and dissolving everything is very attention-grabbing. I remember the discourse focusing on statues; George Washington’s marble face slowly melting under sizzling raindrops makes a heck of an image.

I am not the first person to notice that Washington’s face remains mercifully unmelted. In 2009, Slate asked Whatever Happened To Acid Rain?. EPA Blog, 2010: Whatever Happened To Acid Rain?. 2012, Mental Floss: What Ever Happened To Acid Rain? By 2018 the Internet had advanced, so here’s the Whatever Happened To Acid Rain Podcast. Even the Encyclopedia Britannica, itself a good candidate for a “Whatever Happened To…” piece, has a What Happened To Acid Rain article.

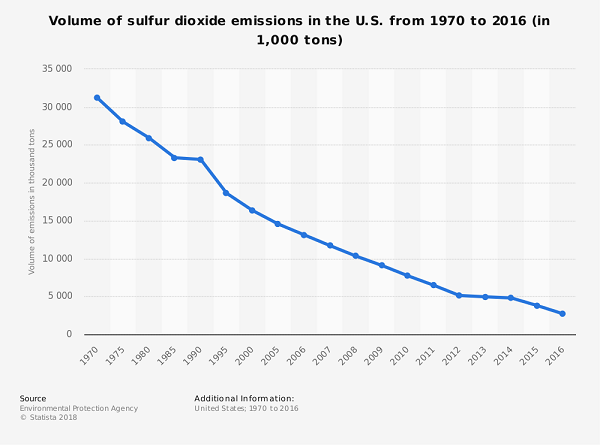

Most of these sources say environmentalists solved acid rain by cutting down on emission of sulfur dioxide, the main offending chemical. A Bush I era cap-and-trade policy gets a lot of the credit in the US, but it looks like it was a broader effort than that:

There’s less clear data on rain acidity, but all my sources agree it has modestly declined in the US, thought it is still “between 2.5 and eight times more acidic than it should be”. Lakes and rivers are slowly recovering. On the other hand, in newly-industrializing countries like China and India, rain is becoming more acidic and they’re going through some of the same issues we were in the 80s.

This picture is slightly complicated by some people who claim acid rain was always exaggerated and “we solved it” is a convenient retreat from acknowledging this (for what it’s worth, these people tend to be global warming skeptics too). Most of them point to the 1990 National Acid Precipitation Assessment Program, a giant government investigation into the acid rain problem. I found a 1990 New York Times article on the report here:

A comprehensive Federal report that was supposed to resolve the issue of how much damage is caused to forests by acid rain has come under criticism from some distinguished scientists who are reviewing it.

The critics said that the report gave an incorrect impression that air pollution was not causing any large-scale problems for forest ecosystems. They also said that the report, still in draft form, ignored a number of studies suggesting serious air pollution problems.

But other experts contend that the general conclusion of the report is essentially right. The report concluded that with the exception of damage to red spruce at high elevations in the East, forests in the United States are not suffering serious damage from acid rain […]

The report now being reviewed is the final draft, completed at a cost of nearly $500 million. It examines the effects of other pollutants, like ozone, as well as acid deposits, and it concludes that air pollution causes far less environmental damage than has been feared.

An interim report issued by the study group in 1987, before Dr. Mahoney became director, was sharply criticized by many scientists. They contended that it tailored research findings into conclusions that matched the political goals of the Reagan Administration, which opposed new controls on air pollution. No such criticism has been leveled at the 28-volume final draft, which has been generally praised as a sound scientific document.

There is, however, some unhappiness among scientists with the volume dealing with forest health and productivity in the United States and Canada.

Dr. Ellis B. Cowling, associate for research at North Carolina State University’s College of Forest Resources, said in a telephone interview: ”The tone is that we don’t have a problem except in southern California, and with red spruce at high altitudes. That is not a fair statement of the state of scientific knowledge.” He added, ”Perhaps the authors were a bit too hasty in reaching conclusions.”

Dr. Cowling, who is highly regarded by colleagues as a conservative, solid scientist, wrote a memorandum to the authors of the forest health volume. He offered a series of suggestions for changing the wording of conclusions in ways that he said would reflect the state of science more accurately.

The first of those would change a finding that stated, ”The vast majority of forests in the United States and Canada are not affected by decline.” To be more consistent with the data, Dr. Cowling said, the conclusion should read: ”Most forests in the United States do not show unusual visible symptoms of stress, marked decreases in the rate of growth or significant increases in mortality.”

Just because symptoms of forest decline are not currently visible, Dr. Cowling argued, does not rule out the possibility that they are under way.

This article also provides a summary of contemporaneous responses to NAPAP, which quotes study director James Mahoney’s summary of his own report: “The sky is not falling, but there is a problem that needs addressing.”

I cannot find anyone really challenging the NAPAP report nowadays, so I provisionally accept that the damage from acid rain, while real, was exaggerated at the time.

There’s a related debate about how much the lakes and streams affected have recovered. Some lakes and streams are naturally acidic; there is some debate over what percent of lake/stream acidity is natural vs. acid-rain-related. In recent years this debate has focused on whether lakes/streams have recovered after the SO2 decline; if they haven’t, this might suggest their problems were never human-activity-related in the first place.

Global warming skeptic blog Watt’s Up With That claims they haven’t:

Possibly the greatest evidence against harmful effects of acid rain is the fact that acidic lakes have not “recovered” after most sulfur and nitrogen pollution was removed from the atmosphere. The 2011 NAPAP report to Congress stated that SO2 and NO2 emissions were down, that airborne concentrations were down, and that acid deposition from rainfall was down, but could not report that lake acidity was significantly reduced. The report states, “Scientists have observed delays in ecosystem recovery in the eastern United States despite decreases in emissions and deposition over the last 30 years.” In other words, the pollution was mostly eliminated, but the lakes are still acidic.

You can find the report here. Like all long government reports, the details are ten zillion different trends in different directions that don’t form a cohesive narrative, and the executive summary is “things are good in all the ways that suggest we deserve more money, but bad in all the ways that suggest we need more money”, It is complicated enough that you shouldn’t trust my excerpting, but at least to me the relevant excerpts seem to be:

Levels of acid neutralizing capacity (ANC), an indicator of the ability of a waterbody to neutralize acid deposition, have shown improvement from 1990 to 2008 at many lake and stream long-term monitoring sites in the eastern United States, including New England and the Adirondack Mountains. Many lakes and streams still have acidic conditions harmful to their biota even though the increases in ANC indicate that some recovery from acidification is occurring in sensitive aquatic ecosystems

And:

Despite the environmental improvements reported here, research over the past few years indicates that recovery from the effects of acidification is not likely for many sensitive areas without additional decreases in acid deposition. Many published articles, as well as the modeling presented in this report, show that the SO2 and NOx emission reductions achieved under Title IV from power plants are not recognized as insufficient to achieve full recovery or to prevent further acidification in some regions.

So Watts seems to be mostly wrong when they say lakes are not recovering, but mostly right when they say ecosystems are not recovering. But NAPAP has some explanations for why ecosystems are not recovering: first, if you poison a lake and kill everything, then even if you remove the poison later everything is still dead. Second, there are complicated natural cycles that gradually wash old deposited land-based pollution into lakes, and it will be a long time before all the pollution deposited on land gets fully washed away. Third, maybe we haven’t fought acid rain hard enough.

I think a lot of the epistemic work here is going to get done by people’s respective stereotypes about the trustworthiness of global warming denialists vs. big government agencies whose budget depends on there being a problem. But my impression is that Watts’ claim that poor recovery suggests acid rain was never a problem don’t hold up very well.

In any case, it’s undeniable that rain has become a lot less acid lately, and likely that this has at least modest positive effects on some ecosystems as well as on the built environment. Anti-Confederate protesters have replaced acid rain as the number one threat to our statues. Our precious, precious statues. Someday they will be safe.

Verdict: A little of everything: partly solved, partly alarmism, partly still going on.

3. The Rainforests

Maybe the most typical image of 90s environmentalism is men in bulldozers clear-cutting a rainforest, while tapirs and tree sloths gently weep.

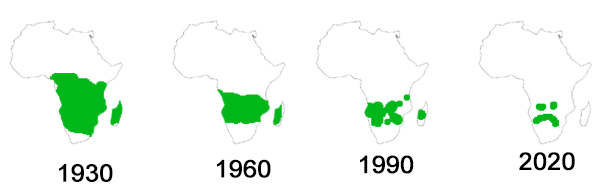

Or maybe it was the declining-rainforest-coverage-over-time-maps. I feel like about one in every three posters I saw as a child looked something like this:

This is a fake example. Please stop asking me where I am getting the data from.

I thought surely nothing could be easier than digging up a few of them and seeing whether their 2020 predictions were right. But I can’t find them anywhere. According to the Internet, there is no such thing as 90s-era maps showing declining rainforest coverage over time. Can anyone else locate these?

Anyway:

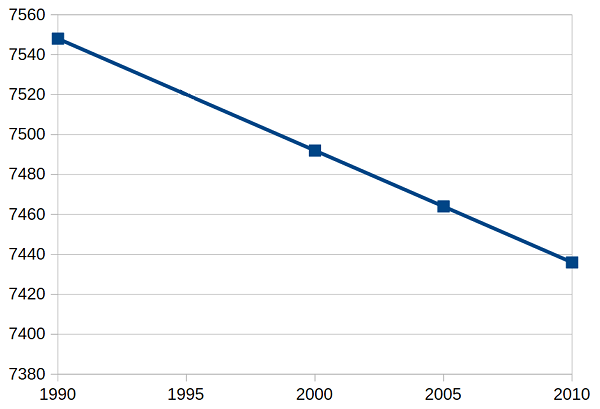

Here’s a graph of the size of the Amazon over time (source, note that the y-axis is not at zero). At 90s levels of deforestation, the Amazon would have disappeared in about 200 years. At current levels, it will disappear in about 400 years.

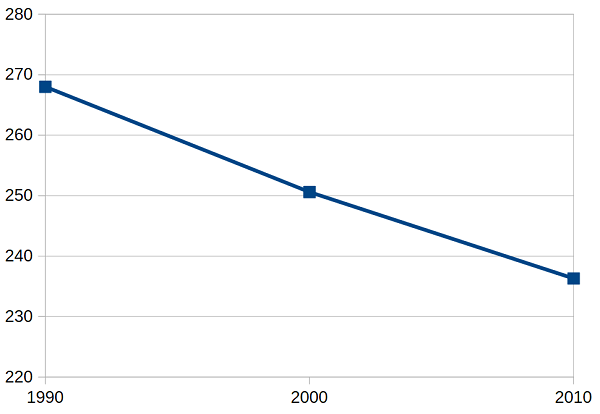

Here’s the Congo (somewhat dubious source, same caveat). At the rates shown here it will be gone in 250 years – but it seems to have slowed after the period on the graph.

And here’s Southeast Asia (source, same caveat). At this rate, the southeast Asian forest will be gone in 150 years, though some new papers are suggesting we may be underestimating the deforestation rate.

Overall it looks like deforestation may have decreased modestly in the Amazon (and possibly the Congo) since the 1990s. It has not decreased significantly in Southeast Asia, and whatever decreases have happened are not relevant to the scale of the problem.

The only good news is that all those “rainforests will be gone by 2050” posters were just wrong; there is more rainforest than that. But not that much more.

Verdict: The problem still exists, and we are just ignoring it now.

4. Endangered Species

So just find how many species go extinct each year, and whether it’s a lot or a little, and then we’ll know what’s going on with this, right? Ha ha, as if.

On the one hand, the UN Environment Programme says that “150-200 species of plant, insect, bird and mammal become extinct every 24 hours.”

On the other, nobody can name more than a single-digit number of species that go extinct in any given year. The 2017 list includes five: a bat, a cat, a flatworm, a lizard, and a snail. This matches longer-term surveys: Ceballos et al (2018) find that about 477 vertebrate species have gone extinct since 1900 – again, about five per year. And a recent survey found only four to eight bird species had disappeared since the turn of the century.

I have no idea where the 150-200 number per day comes from, and neither does anyone else. The closest I can find to a justification is this WWF page, which reminds us that if there are 100 million animals species, and “the extinction rate is just 0.01% per year”, then at least 10,000 species go extinct every year (=200-300/day) – but all of these numbers are completely made up.

One could try to justify these estimates with something like “assume only one in a thousand species has been discovered and is monitored well enough to detect its extinction, so if we detect five extinctions per year then five thousand must be happening” – but I’ve never heard anyone actually say this. Also, with apologies to all the undiscovered species, if they’re so tiny and uncommon as to never get discovered, it doesn’t seem like their extinction is going to change very much.

Five known species going extinct per year may sound like a lot if you’re thinking it’s something like “rhinos, pandas, whales, spotted owls, and leopards”. But realistically there are 385 species of shrews. We could spend our entire yearly extinction budget on shrews for the next sixty years and still have more than enough kinds of shrews left to satisfy basically anybody.

I’m trying to think what the best counterargument to this would be – the best case that we really do need to consider species extinction a dire concern.

Maybe this is too vertebrate-centric, and there are lots of insects and plants and such going extinct all the time? But this List Of Recently Extinct Insects suggests that of about 6000 known insect species, only 50-100 have gone extinct in the past century. And one of those was this giant earwig which I really think the world is better without.

Or maybe we can’t directly predict the future from the past. Imagine 1000 square miles of rainforest with a homogenous distribution of species. Clear-cut 50% of the rainforest, and no extinctions. Clear-cut 90% of the rainforest, still no extinctions. Clear-cut 99%, maybe a few extinctions if you’re unlucky. Then clear-cut the last remaining 1% and everything dies. It seems like something like that might be happening – see for example this report that global animal populations have declined 58% over the past forty years.

But any concept of endangered species that focuses on “many well-known species will be gone soon” doesn’t seem consistent with the evidence.

Verdict: Partly alarmism, partly still going on.

5. More And More Trash Piling Up Until The Whole World Is Just A Giant Mountain Of Trash

Wait, what? Was this really a concern? Did I really spend my primary school years being told that if I didn’t vigilantly recycle everything, one day I would be submerged beneath a sea of trash, breathing by means of a trash snorkel? Am I hallucinating all of this?

As usual, it turns out to be the Mafia’s fault. In the 1980s, mob boss Salvatore Avellino took over New York City’s landfill industry, and in a shocking development which nobody could have predicted, was corrupt. New York City soon ran out of landfill space. Somehow all of its excess trash ended up on a barge called the MOBRO-4000, because the Eighties, and this barge apparently sailed up and down the east coast of North America searching for a place to deposit its trash. In its many exciting adventures it reached the coast of Belize, got involved in a confrontation with the Mexican Navy, and finally went back to New York, where at some point landfill space was found and the crisis was over.

But a giant boat full of trash made a really memorable image, and it got nationwide news coverage, and environmentalists took advantage of this to tell everyone there was no more landfill space anywhere in the world and we all had to recycle right now. According to Wikipedia:

At the time, the Mobro 4000 incident was widely cited by environmentalists and the media as emblematic of the solid-waste disposal crisis in the United States due to a shortage of landfill space: almost 3,000 municipal landfills had closed between 1982 and 1987. It triggered much national public discussion about waste disposal, and may have been a factor in increased recycling rates in the late 1980s and after. It was this that caused it to be included in an episode of Penn & Teller: Bullshit! (season 2, episode 5) in which they debunk many recycling myths.

I’m even absolutely right in remembering primary school lessons centered around garbage covering the Earth and killing everybody. Here’s a New York Times article from 1996 – ie after the crisis had a little bit of time to fade – lightly mocking the new curricula that followed in its wake:

After the litter hunt in Ms. Aponte’s science classroom, it was time for a guest lecturer on garbage. A fifth-grade class was brought in to hear Joanne Dittersdorf, the director of environmental education for the Environmental Action Coalition, a nonprofit group based in New York. Her slide show began with a 19th-century photograph of a street in New York strewn with garbage.

“Why can’t we keep throwing out garbage that way?” Dittersdorf asked.

“It’ll keep piling up and we won’t have any place to put it.”

“The earth would be called the Trash Can.”

“The garbage will soon, like, take over the whole world and, like, kill everybody.”

Dittersdorf asked the children to examine their lives. “Does anyone here ever have takeout food?” A few students confessed, and Dittersdorf gently scolded them. “A lot of garbage there.”

She showed a slide illustrating New Yorkers’ total annual production of garbage: a pile big enough to fill 15 city blocks to a height of 20 stories. ‘There are a lot of landfills in New York City,” Dittersdorf said, “but we’ve run out of space.”

From the same beginning-of-the-backlash period we also get this 1995 Foundation for Economic Education piece, Are We Burying Ourselves In Garbage?:

A popular idea in public discourse today is that the United States produces an overwhelming amount of trash–so much that our landfills will not be able to handle the quantity. The most eloquent symbol of this viewpoint was the “garbage barge,” which in the late 1980s left Long Island and could not find a port or country willing to accept its 3.168 tons of refuse. [But] the actual data (such as they are) on the amount of municipal solid waste produced present us with more questions than answers.

This article also deserves note for hitting on a brilliant solution:

The crisis mentality has distorted judgment of waste disposal. The notion that modern America is especially wasteful is demonstrably wrong, both in terms of the last decades as well as the last 100 years. The idea that our landfills are literally “running out” is even less credible. If in the next century major portions of the United States really need to export their refuse to other states, a “gold mine” for refuse burial does exist: South Dakota. This state is geologically, economically, and politically almost ideal for massive municipal solid waste management.

None of this is a joke. This is how your parents did Discourse, people.

But it turns out capitalism works: if there’s a shortage of landfills, that incentivizes people to create new landfills. Also, the world is very large and it is hard to cover a significant portion of it in trash. There was a brief blip as cities figured out how to pay for more waste disposal, and then nobody ever worried about the problem again. Recycling remained inefficient and of dubious benefit, and never really caught on.

There is still an international problem as Third World countries struggle with infrastructure issues around trash disposal. You still see occasional articles like Huffington Post’s People Are Living In Landfills As The World Drowns In Its Own Trash, from earlier this year. But I think in general nobody in the First World still considers this a major problem.

Well, almost nobody:

The earth, our home, is beginning to look more and more like an immense pile of filth.

— Pope Francis (@Pontifex) June 18, 2015

Verdict: Alarmist. So, so, alarmist.

6. Peak Resource

Is the earth’s ballooning human population using up resources at an unsustainable rate?

Technically the answer must be “yes”, since by definition nonrenewable resources have to run out at some point. But when? Long after we have escaped to space and gotten access to shiny new resources? Or soon enough that we have to worry about it?

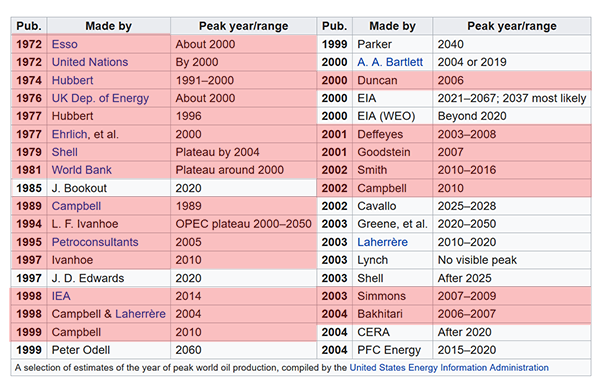

A big part of 90s environmentalism involved worrying that it was the latter. A particular concern was “peak oil”, the point at which we had exhausted so much of the world’s oil that production rates declined every year thereafter and oil started becoming gradually rarer and more expensive. Wikipedia has a helpful table of people’s peak oil predictions. I’ve highlighted the ones that have already passed in red.

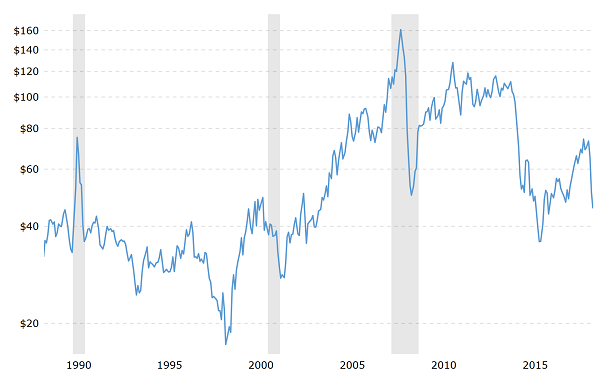

Almost everyone working before 2000 thought we would have reached peak oil by now. But here’s world oil production over time:

And the price of oil:

What happened? People discovered fracking and other paradigm-shifting techniques to extract oil from shale, which opened up vast new previously-inaccessible oil fields. The peak oil predictors might call this unfair – they calculated correctly given the technology they knew about – but the whole argument of the people who say we don’t have to worry about peak resource (sometimes called “cornucopians”) is that technology will advance fast enough to satisfy our resource needs. In this case they were right.

What about non-oil resources?

In 1980, leading environmental scientist and peak-resource proponent Paul Ehrlich made a bet with cornucopian economist Julian Simon about how resource prices would change over the next decade. The Simon-Ehrlich Wager has become a famous example of futurology done right – two people with different theories implying different predictions coming together, agreeing on exactly what each of their theories implied, and then publicly committing to put them to the test. According to Reb Wiki:

Simon challenged Ehrlich to choose any raw material he wanted and a date more than a year away, and he would wager on the inflation-adjusted prices decreasing as opposed to increasing. Ehrlich chose copper, chromium, nickel, tin, and tungsten. The bet was formalized on September 29, 1980, with September 29, 1990 as the payoff date. Ehrlich lost the bet, as all five commodities that were bet on declined in price from 1980 through 1990, the wager period.

Looks pretty good for Simon and the cornucopians. But the article continues:

Ehrlich could have won if the bet had been for a different ten-year period. Ehrlich wrote that the five metals in question had increased in price between the years 1950 to 1975. Asset manager Jeremy Grantham wrote that if the Simon–Ehrlich wager had been for a longer period (from 1980 to 2011), then Simon would have lost on four of the five metals. He also noted that if the wager had been expanded to “all of the most important commodities,” instead of just five metals, over that longer period of 1980 to 2011, then Simon would have lost “by a lot.” Economist Mark J. Perry noted that for an even longer period of time, from 1934 to 2013, the inflation-adjusted price of the Dow Jones-AIG Commodity Index showed “an overall significant downward trend” and concluded that Simon was “more right than lucky”. Economist Tim Worstall wrote that “The end result of all of this is that yes, it is true that Ehrlich could have, would have, won the bet depending upon the starting date. … But the long term trend for metals at least is downwards.”

How about today? An econblogger is still keeping track of the Ehrlich-Simon wager, and finds that as of August 2017, Simon (who is now dead) is still winning; a basket of the five metals involved still costs less than it did in 1980.

Can we zoom out even further? There are a bunch of commodity indices that do for commodities what the Dow Jones does for stocks. I chose the Standard & Poor Goldman-Sachs Commodity Index kind of randomly because they were a familiar name and it was easy to find which goods they included. I’m not quite sure I’m doing this right, but this seems to be the most relevant graph:

The price of commodities in general is still lower than in 1980 (also, with this graph it becomes clear Ehrlich was really unlucky in which year he started his wager).

I have never heard anyone claim that this represents an environmentalist victory: I don’t think there was any large-scale attempt to conserve or recycle chromium/tungsten/whatever that led to its current abundance. I think this was just a victory for resource extraction technology.

There are still theoretical reasons to think we have to run out of stuff eventually. But in terms of how the past 25 years have treated 90s-era concerns about resource depletion, it’s hard to answer anything other than “savagely”.

Verdict: Alarmist

7. Saving The Whales

I remember frequently being told we had to do this. Apparently it paid off, since a global moratorium on whaling was signed in 1982.

The ban is not perfect. Indigenous peoples are allowed to hunt whales in traditional ways. Japan pretends their whaling is for “scientific purposes” and has so far gotten away with it. Norway and Iceland never signed the moratorium and continue to whale.

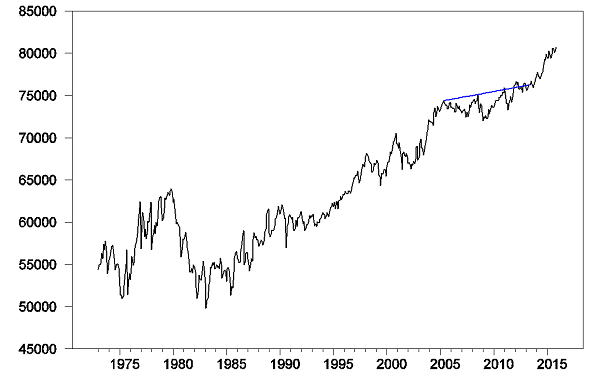

But overall, things are going pretty well. There aren’t a lot of graphs, but the International Whaling Commission (which despite its name is against whaling) says blue whale populations are increasing at about 8%/year, humpback whales around 10%, and fin whales around 5%. Those sound pretty good, but they have to be taken in context:

Okay, fine. There’s one graph. But it’s really depressing. See that tiny micro-bump at the end? That represents progress.

Verdict: Environmental movement successfully solved this problem.

8. Concluding Thoughts

This was not a very conclusive exercise. When I add these up – as if that were at all an acceptable thing to do! – I get 2⅓ that were solved, 2⅚ that were alarmism, and 1⅚ that continue. So there is not much to be said about them as a group. Some were solved through heroic effort. Some turned out to be completely made up. Some of them are still out there but have stopped capturing the public’s attention.

Victories I can understand. It’s the latter two categories that confuse me.

How did the non-problems fade away? There was no moment when some brave iconoclast posted ninety-five theses to the door of the local recycling center and said “No! There is not a landfill crisis!” I mean, John Tierney wrote things along those lines, and did a great job of it. But he’s not a household name and there was never a time when everyone said “Oh, John Tierney is right, let’s stop worrying about this.” The people who stopped worrying about this never heard of John Tierney. At some point people just went from being very worried about the landfill crisis to shaking their heads and saying “The world getting full of trash? Sounds pretty stupid.”

And the story with peak resources seems entirely different. You will still occasionally see people saying “The Earth can’t support our greed, soon we will run out of everything”, and reasonable people will nod along with this and admit it is very wise. But you hear it like once a year now, as opposed to it being a constant refrain. This idea was never intellectually defeated at all, at least not on the popular level. It just faded away.

Was there some rarified level of intellectual debate where these ideas lost out? And then, denied their support from the commanding heights of the ivory tower, did journalists stop writing about them, schoolteachers stop teaching them, and then eventually the public – who have no will of their own and have to be told what matters – wander off and do something else?

Or was the change bottom-up? Did the public, after the millionth editorial on the trash crisis, say “Okay, whatever”, such that journalists realized this was no longer a good way to sell newspaper subscriptions? Is there a natural news mega-cycle of a decade or so, after which the public gets tired of hearing about a certain story, the intellectuals get tired of talking about it, every possible angle has been explored, and people move on, whether or not it was solved? Does this explain why the rainforests, a real problem that is still going on, similarly lost public attention?

Or maybe climate change took over everything, became so important that everything else faded into the background. This is certainly how it feels to me. Whenever I hear about the rainforests nowadays, it’s as a footnote to some global warming story where they add that we should save the rainforest as a carbon sink. Whenever I hear about landfills or recycling today, it’s in the context of trash giving off greenhouse gases. It feels almost like some primitive barter system has been converted to a modern economy, with tons of CO2 emission as the universal interchangeable currency that can be used to put a number value on all environmental issues. Can’t figure out a way to convert whales into a carbon sink? Guess they’ll have to go.

(I wrote that, then remembered I lived in 21st century America, did a Google search, and sure enough there are dozens of articles arguing that saving whales is an efficient way to neutralize greenhouse gases)

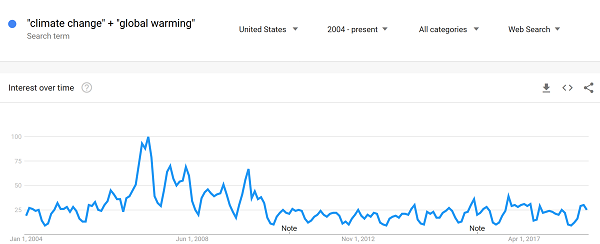

But as attractive as this picture is, it’s hard to find the supporting data. There’s just not hard evidence that we care more about global warming than we did fifteen or twenty years ago:

Here’s the Google Trends. There was a lot of interest in 2006, which I think gets attributed to Al Gore’s An Inconvenient Truth in that year, but not a lot of signs of increase today.

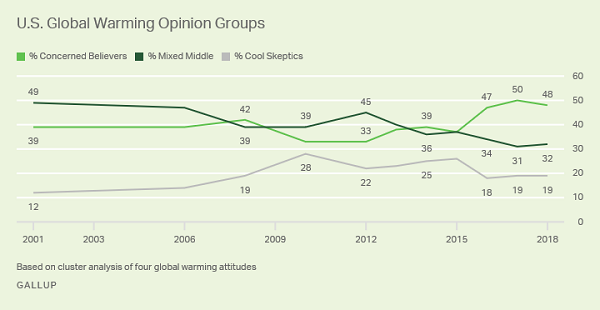

Here’s Gallup. It at least shows a spike starting in 2016 – but given its timing and the lack of obvious 2016 global-warming related events, I think it’s probably just another Trump backlash effect.

If global warming is eating all the other environmental issues, it doesn’t seem to be extracting that much nutrition from their corpses. And the ozone hole – probably the most global-warming-like issue of the last generation – managed to gather popular support at the same time that people were worried about a host of other things. I don’t know. Maybe given the public’s tendency to get bored of an issue after a decade or so, global warming has to cannibalize the rest of environmentalism just to survive at all. Depressing if true.

Or maybe it’s a zeitgeist thing. For some reason, it’s hard to imagine 2018 being the Year Of Rainforest Concern. There’s something very 90s Optimism about worrying about the rainforests, something where even the warnings of doom have a cheerful ring to them. I remember a Rainforest Charity Box at my local mall as a kid, promising that if you donated $10, you would save a brightly colored parrot, and if you donated $50, you might save a jaguar. Who thinks that way these days? Now if you donate some amount to stopping global warming, you will have won yourself a lecture from a bunch of people telling you that still doesn’t mean you have the right to feel good about yourself, and the world is going to fry regardless. Have we just passed the point where anybody can care about crisp mountain streams or frolicking snow leopards any more?

The most important thing I take away from the exercise is a sort of postmodern insight into the way environmental issues are constructed. This is definitely not me saying they are all made up; many of them are very real. But the mapping from real crisis to social panic is tenuous, contingent, and historical. Sometimes random things that shouldn’t matter get magnified into the issue du jour; other times giant world-threatening crises manage to slip everyone’s attention.

Imagine that twenty years from now, nobody cares or talks about global warming. It hasn’t been debunked. It’s still happening. People just stopped considering it interesting. Every so often some webzine or VR-holozine or whatever will publish a “Whatever Happened To Global Warming” story, and you’ll hear that global temperatures are up X degrees centigrade since 2000 and that explains Y percent of recent devastating hurricanes. Then everyone will go back to worrying about Robo-Trump or Mecha-Putin or whatever.

If this sounds absurd, I think it’s no weirder than what’s happened to 90s environmentalism and the issues it cared about.

It seems a little odd to omit global warming from the set of 90s environmental concerns, given the debate over Kyoto, the prominence of pre-Inconvenient-Truth Al Gore at that time, and the ridicule heaped on him over _Earth in the Balance_.

As all of the predictions and models have been shown to be vastly overstated (hence the name change from Global Warming to Climate Change), most folks have generally lost interest in this “crisis”.

Source for your claimed etymology? Wikipedia says that the terms “global warming”, “climate change”, and the now outdated “climatic change” all date back to at least the 70s.

All these terms sound pretty mild to me. Even a cut-rate propagandist looking to raise the alarm should be able to do better. “The Heat Trap” sounds more severe than all of them, and isn’t completely inaccurate.

Everything you just said is completely wrong. Whoever told you that there was an intentional change in terminology to protect the idea is lying to you.

It wasn’t a big conspiracy, but I hear “climate change” a lot now, and it was quite rare 15-20 years ago(when I was first getting into political debate). It feels like there’s been some evolutionary pressure pushing people from “GW” to “CC”, probably to try to stop denier talking points, even if there’s no Carbon Catastrophe Conspiracy Coordinating Committee making it happen.

I mean, there is a “conspiracy”… By Frank Lutz, republican strategist.

http://web.archive.org/web/20121030085144/http://www.ewg.org/files/LuntzResearch_environment.pdf

There was an intentional shift by those intending to minimize the effects of climate change to move from “global warming” (which sounded scary) to “climate change” (which sounded less scary). Meanwhile, in the actual science of climate change, both terms have been used, because they mean different things – global warming is a more precise term; climate change is more general, and the latter was always considerably more common in the scientific ilterature.

https://skepticalscience.com/climate-change-global-warming.htm has more details.

Going by google metrics, there is a slight shift in popular usage (climate change is more common, global warming is less common, see here: https://trends.google.com/trends/explore?date=all&geo=US&q=climate%20change,global%20warming ) but this may be in part driven by “An Inconvenient Truth”; you can see the huge spike in 2006; and it’s a very minor shift either way.

It is important to remember that when it comes to global warming, there is a huge denialist contingent intent on arguing in the public square very loudly in poor faith, fueled by fuel industry money. The entire right-wing sphere in the USA is either part of this or influenced by this. This is extremely well-established. This debate is very reminiscent of the “debate” surrounding teaching creationism in the classroom – one side is simply utterly uninterested in the truth. The sooner people realize that, the better. And, uh… pro tip – it ain’t the side that has literally all the scientific evidence backing them up.

Wasn’t it because some of the predicted effects of global warming were things like “stuffs up the gulf stream”, which should cool down the UK and the east coast of the US?

Every summer at least one person tells me that global warming is definitely happening because it’s hot outside, and every winter an equal and opposing number of people tell me global warming is definitely not happening, and also they can stand in the rain perfectly fine without the flesh sloughing off their bones, and by the way dogs still aren’t extinct yet. Maybe “global warming” triggers an annoying common sense reaction but “climate change” doesn’t.

Luntz is a fun character, to be sure. (For those unaware, he’s also the one who created the “death taxes” moniker. Effective bugger, though quite single-minded)

To be clear, though, I’m referring to terminology used by laypeople who are genuinely concerned about carbon. My social circles have shifted over the relevant timeframes, of course, so I can’t say it’s definitely a true signal. But it seems like the left has shifted, and I’ve seen multiple posts over the years explicitly attacking AGW deniers for using “global warming” too narrowly and switching to “climate change” as a response. Most of that was like a decade ago now, but it seems like that was the most likely cause from my observations.

As for the science of the issue, be careful what you claim. I agree that the climatology of AGW is pretty bulletproof at this point(sometimes overstated, and often overconfident, but obviously correct in direction). I’m no climatologist, but I generally trust those who are, and the physics makes a lot of sense. That said, the economics of many AGW solutions are hilariously bad, and economics is a field I feel quite conversant in. The recent shift to carbon taxes has helped a ton here, but if the green movement ever decides to do any more than that, I’d put >90% confidence on their efforts being overcosted, counterproductive, and generally stupid.

@eh as said – there really isn’t a shift like that. Not a big one in the public consciousness, and definitely not one within the scientific literature. I’m not aware of any public campaigns to shift the language other than the aforementioned one by Lutz.

@Alsadius: Well, as said, the actual effect sizes just aren’t that big, and I’m not sure there’s really a “there” there.

fueled by fuel industry money

Ah, it’s been a while since I read a good old-fashioned “the big oil companies are sitting on the research that will let us run cars on water for a hundred miles to the gallon!” style conspiracy post, thanks BPC!

@Deiseach

The claim is that they lobby for their interests…

Deiseich:

Big Oil making everyone forget about some kind of massively better engine technology is hard. Big Oil preferentially funding the minority of researchers in climate modeling who get results that look better for their bottom line is pretty easy. =

@Aapje

The claim is that they lobby for their own interests with such efficacy that ‘The entire right-wing sphere in the USA is either part of this or influenced by this.’

Literally all of this is wrong. The denialist contingent is not huge. There are virtually none arguing in the public square. They are not arguing in bad faith, and they are not funded by fuel industry money. The right-wing sphere in the U.S. is neither a part of this nor influenced by this (since it doesn’t exist). What you argue is neither “established” nor actually true. The debate has nothing to do with creationism at all. Both sides are interested in the truth. One side doesn’t have literally all the scientific evidence backing them up.

I’ve witnessed skeptics being attacked for using the term “global warming” and admonished that they are stupid idiots because they aren’t using the phrase “climate change.” All by environmentalists.

I think GW is likely a real problem but that doesn’t mean the people who happen to be on my side always argue in good faith.

@BPS:

On the subject of spending on criticism of AGW …

Some time back, I came across an article which claimed to show how much was being spent. If you read it, you discovered that they were taking organizations such as AEI, which among other things were critical of the current orthodoxy, and attributing their entire budget to such criticism when, in the case of organizations I knew about, it was a minor issue for them.

Do you have a source for your claims—not someone else who makes them but someone providing evidence for them—and if so what is it? How does the amount it claims is being spent compare with the amount spent by the federal government and private foundations on work supporting the current orthodoxy?

“The entire right-wing sphere” may be an exaggeration, but it’s not all that strange to think that big oil companies might have a profit motive, that their arguments and positions on issues might be influenced by that, and that–having the amount of money and leverage they do–they might have some level of sway over the political discourse.

All of that doesn’t in and of itself prove that they’re wrong, but it is a reason to treat their arguments (and the arguments of those who might’ve been influenced by them) with more skepticism.

@Hyzenthlay says:

If this notion not at all strange, what do you say to the idea that climate scientists might be systematically biased towards results that, if accepted, would tend to result in increased prestige, funding, and importance for climate science?

@cassander

I wouldn’t find that strange or surprising, either. More alarming/controversial studies get more attention than less alarming/controversial ones, in any area of science. And since fear is always politically useful, it’s also not implausible that some politicians would use global warming as a bogeyman so they can then say, “Don’t worry, once I’m in power I’ll do something about it.” There are potential biases in both directions.

But studies still have to go through the review process and are heavily scrutinized, so while it’s neither perfect nor totally unbiased, I tend to think science is better at producing answers than other avenues. And while there’s some disagreement among climate scientists about how severe the problem is, there seems to be a pretty wide consensus that it is a problem.

I also don’t think acknowledging the existence of biases and flaws in the process of producing studies means that any and all scientific knowledge can be thrown out. It’s often still the best information we have, so pointing out general problems and perverse incentives within science as a whole is often done selectively, in a fallacy-of-gray kind of way, to dismiss particular studies.

@Hyzenthlay:

Would it bother you to learn that big oil companies have repeatedly provided funding to scientists generating mainstream global warming alarm? For instance, British Petroleum and Shell were large sponsors of the UEA Climatic Research Unit. (you can still find them listed in an Acknowledgements paragraph here.)

To the extent that oil companies have some level of sway over the political discourse, it’s not actually clear which direction that sway is pushing things!

(If you want to be cynical about this, there do exist arguments that being involved in climate alarmism helps large oil companies…but it’s also possible the people on corporate boards enjoy getting good press from such investments. Or they see it as an investment in goodwill with liberal regulators/legislators. Or it could be a marketing expense aimed at pleasing the public and buying off their worst detractors.)

Glen Raphael:

It’s also quite possible for a large organization to be doing lots of mutually-contradictory things at once–perhaps they’re supporting high-quality scientific research from one pot of money, quackery that will support their economic position from another pot, mainstream climate science with another pot, dissident climate science with still another pot, etc.

Hyzenthlay,

But studies still have to go through the review process and are heavily scrutinized, so while it’s neither perfect nor totally unbiased, I tend to think science is better at producing answers than other avenues. And while there’s some disagreement among climate scientists about how severe the problem is, there seems to be a pretty wide consensus that it is a problem.

I’m an academic scientist. While peer review is better than nothing, it is usually far less than “heavy scrutiny”. Reviewers are lazy and subject to peer pressures like people in any other area. If a paper doesn’t challenge current orthodoxy or other interest it may be recommended for publication with barely a look. Conversely, it can be very difficult to publish something that goes against the grain. I think this is the common experience of all working researchers.

I’m a physical scientist, but I imagine this is far more true in the softer, more difficult sciences, where I would put climate science at the moment, than in the physical sciences where I have direct experinece.

Early models grossly overestimated some warming, and other early models also grossly underestimated it. This will be the case for any model of any kind that get refined over time; poorer models have greater variance, and as a model improves, both the lower and upper bounds get reduced.

I’m not sure if it has affected public interest in the problem, but reality is that there continues to be a significant problem and as the science has improved, the findings have become quite robust. But I agree this could be a case of “public lost interest, but it’s still a significant problem” like the rainforest loss conclusions.

I find this claim to be quite surprising. Source?

Also, the term “Global Warming” is still accurate, AFAIK. Average global temperatures have increased since the industrial revolution began. [1] What I’ve always heard is that the term “Climate Change” is preferred for the reason that increased temperature isn’t the only consequence of rising atmospheric CO_2. There’s also ocean acidification, changing rainfall patterns, etc.

[1] https://climate.nasa.gov/vital-signs/global-temperature/

I think it is important to distinguish between work done by serious scientists, in which group I would include the IPCC and William Nordhaus among others, and the extensive puffery by popularizers. If you look only at the rhetoric, the former group are alarmists as well. But if you look at the numbers, they aren’t.

The first IPCC report badly overestimated future warming. Since then the estimates have been high, but not wildly high. The IPCC fourth report claimed that AGW was causing drought, the fifth report retracted that claim. For some of my favorite examples of modest claims by people with alarmist rhetoric, see this (IPCC) and this (Nordhaus).

I feel the change was because about 99% of common people talking about it confuse weather with climate, and “global warming” plays to that confusion, allowing people alternatively mock “global warming” as ridiculous concept in the middle of the winter and proclaim “global warming” conclusively proven by the heat of the summer – to the ridicule of more informed opponents, and hopelessly confusing the essence of the matter.

“Climate change” is less vulnerable to this confusion (though it is vulnerable to more sophisticated trolling, highlighting the fact that the climate has been changing all the time, so strictly speaking fighting “climate change” is pointless).

Agreed — global warming was part of 90’s environmentalism, not something later and separate. Obviously it’s mentioned, I’m confused why it didn’t get its own section; it’s mentioned, as I just said, in a way that suggests that it’s something later and separate.

Because he was asking where these issues went, and it clearly hasn’t gone anywhere.

As I interpreted it, this was an article largely about environmental issues we no longer hear about, not all issues covered in the 90s. This was substantiated by graphs about declining interest on Google trends. As climate change is still definitely on the environmentalist radar, I think it makes some sense to skip it.

Oh man this one. Does anyone remember that Simpsons episode? (They also did the ‘syringe tide’ at one point too.) Or the Choose-Your-Own-Adventure with the trash aliens? I felt dumb as a kid when I finally cottoned onto how small dumps are and how big and empty North America was and realized that this could never be a problem, not in a million years.

One name for this mega-cycle is “the issue-attention cycle”: “Up and down with ecology – the ‘issue-attention cycle'”, Downs 1972; “On Anthony Downs’s ‘Up and Down with Ecology: The “Issue-Attention” Cycle'”, Gupta & Jenkins-Smith 2015.

Yes, but somehow more as an example of local government corruption / incompetence; “The Garbageman Can” is almost as much a masterpiece as the Monorail Song in that niche. Fortunately, Matt Groening had a second shot at the subject in Futurama, so we can be pretty sure where his sarcastic pen is pointed.

Eh. The trash came from elsewhere, it wasn’t just mocking Quimby. And then you have the Indians at the end. It was easy to read in the zeitgeist then.

Yeah but our oceans actually are suffering from a vast increase in the amount of non-biodegradable trash.

All trash is biodegradable, is it not?

All trash is biodegradable, is it not?

No, and it tends to go the other way, and degrade the “bio” instead of being degraded by it.

Most common plastics do not biodegrade. For a long time, it was claimed/hoped that they did, but it turns out that instead the degrading comes from UV light, not biological activity. And the polymers do not break down all the way back to component atoms or even monomers, but instead to dust-sized grains small enough to accumulate (and accumulate and accumulate) in places where the UV doesn’t penetrate, such as just below the top of the soil, and floating just below the top of the water surface, both of which are possibly the worst possible places for the stuff to accumulate.

Much of the stuff that you would point at now and call paper and cardboard is full of plastic.

“Ewaste” is even worse, because it’s awkwardly sized pieces of plastic and metal and toxic battery chemistry, and full of enough weird shit that melting/burning it for metal value is… problematic.

The well meaning demand to recycle post-customer trash is counterproductive, resulting in the stuff getting shipped often long distances, and processed and ground up in ways that let it get into the biosphere.

We would have a lot less “trash turning into ecologically damaging plastic in the oceans and toxins in the foodchain” if we would just stop fucking with the stuff, and ship it the shortest possible distances and bury it with minimum possible fuss in stable landfills lined with heavy… plastic.

Widespread species extinction is not a “dire concern” in the same sense that the burning of the Library of Alexandria was not a dire concern. If your question is “will this cause the end of human civilization?”, the answer is no, not unless extinction levels really ramp up unprecedentedly. If your question is “will this cause immeasurable loss in potential scientific knowledge of ecosystems and evolutionary history, and irreversibly make the existence on earth less enjoyable for future generations?”, the answer is yes.

I think that oversells the library of Alexandria, and undersells extinction risks.

Was the burning of the library of Alexandria that big of a deal at the time though? It seems like a pretty localized tragedy. It makes historians now sad, but lots of libraries have burned throughout the ages. Material progress was slower in the past, but I don’t think it was due to the difficulty of preserving information.

On the other hand, even if most species are as irrelevant to the typical human as the library of Alexandria was back then, there are some extinctions that could be extremely costly. I’m not aware of any civilization level catastrophic extinctions that are plausible off the top of my head, but accidentally driving extinct enough honeybee species or something like that could be very costly.

It’s somewhat complicated to quantify costs of extinctions in and of themselves because so many things that cause extinctions are also directly harmful to humans. Pollution could conceivably wipe out a lot of species in a lake or river, and it also poisons any humans who drink from the lake etc.

This reminds me of a recent article in the New York Times.

To summarize: insect populations are experiencing a massive decline worldwide, even in protected areas that you’d expect to be immune from pollution or environmental loss, which has the potential for negative effects on the environment that aren’t captured by extinction statistics. (For example: ever realize how few dead insects you find on your windshield nowadays?)

At least part of that is improved aerodynamics of automobiles.

This also reminded me of that New York Times article. When I was a gradeschooler in the 90s, I remember a distinct focus on the extinction of individual species. The extinction of a few species did not seem like that big of a deal to me then or now. But the New York Times article speaks of extinction differently than I remember from my childhood:

This seems much more concerning than the issues I remember being discussed (at least with gradeschoolers) in the 90s. For this reason, I think Scott’s verdict that the extinction debate was “Partly alarmism, partly still going on” is probably correct, but because 90s environmentalists did not frame extinction concerns correctly.

I’m a professional research taxonomist, so I can answer this confidently:

Species began to be formally cataloged in the 1700s, and by the mid-1800s we had a extremely good idea of what species were present in the western world at least. Archeological evidence can push our knowledge of the presence of species even further back (1000’s of years) for some taxa, such as mollusks and mammals.

The evidence that species extinction rates rapidly rose in the 20th century, and is directly contributable to human activity, is rock-solid. Pre-industrialisation communities were stable and diverse, post-industrilization communities have been chaotic and simplified.

Like I said earlier, whether you consider this a “big deal” or not depends on how much you value scientific knowledge of the history and diversity of life. Extinction rates are not high enough to cause any real existential trouble for human civilization.

by the mid-1800s we had a extremely good idea of what species were present in the western world at least.

I have the impression that the number of species identified in the US increased by a factor of 5 or so since the passage of the Endangered Species Act, as animals previously considered part of one species were subdivided into multiple species with much smaller ranges. Was I just completely confused?

I used the word “species” here in the colloquial sense. That is, a distinct biological entity. In the formal sense what I am referring to are the number of taxa. We knew what the taxa of North America were by the mid-1800s, so we can reliably map their rate of extinction from there.

What you are probably heard about, is changing trends in question of what taxonomic rank to assign entities: subspecies, variety, or full species. There’s a certain ebb and flow to scientific trends here, with the number of “species” (in the formal sense) high in the 1800’s-~1930, reduced to varieties and subspecies from ~1930-1990, with a modern re-assignment to species rank occurring from ~1990 to today. Many “new” species of the past 30 years are actually old ones that were described in the 1800s, and subsequently forgotten or de-ranked (which tends to lead to them being forgotten).

So the total number of “species”, in the formal sense, is a separate question from the rate extinction.

“There are still theoretical reasons to think we have to run out of stuff eventually.”

You really, really, really must read (at least the first couple of chapters of) The Unlimited Resource, by the Julian Simon you reference. It’s out of print, so here a .doc copy: https://sanjeev.sabhlokcity.com/Misc/ultimate-resource.doc

Could you summarize the main point?

As a resource gets scarcer its price increases. This increase in price causes people to use less of the resource and to innovate. Such innovation will eventually allow us to use the resource more efficiently, to find new means of getting the resource, and to find substitutes for the resource. Markets + brains save us from running out of the resource.

Seems like the two perspectives agree more than they disagree.

When you say: As the resource gets scarcer and it’s price increases, people will use it more efficiently or find substitutes. No need to panic.

The environmentalist hears: “As the resource gets scarcer and it’s price increases, people will be forced to find ways to make do with less, and nations will scramble to try to find available substitutes, if there are any. There will be chaos and human suffering.”

Its true that markets could save us from literally running out of any resource, because the last few bits of Resource X will be sold at auction to museums and wealthy collectors, thus preserving it from ever literally running out.

In addition to what Guy in TN said, “Use resources more efficiently or find substitutes” is exactly what many environmentalists argue for, right? If there’s any disagreement between the environmentalist argument and James Miller’s summary, it seems to be on the urgency of the “innovation” step.

But we don’t tend to reach the chaos and human suffering part due to resource depletion (at least not to a detectable degree), because for whatever reason prices don’t spike hard enough for the transition to be brutal and resources don’t run out fast enough. The eventually of switching to substitutes or finding new extraction methods happens very fast.

And prices go up for all sorts of reasons all the time.

Environmentalists don’t typically predict things like “in a worst case scenario, due to resource depletion you may have to cut your consumption a little bit for a couple years after which time things will be keep improving”.

@mdet

In a very loose fashion that is true. But when environmentalists discuss the problem they tend to propose very specific methods of getting there. Methods that have little to do with the observed trends. Oil companies didn’t start fracking because of environmentalists.

It’s not like the 19th century had catastrophes where we ran out of fuel sources until environmentalists managed to put into place policies for government investment in finding substitutes or conserving resources.

And in some cases, the environmental movement has likely been detrimental (like the U.S. lack of usage of nuclear power).

There are probably some more relevant cases like water. But the people working on things like markets in water rights seem pretty fringe as far as the environmental movement goes.

In the long perspective, nothing appears to cause human suffering, because the march of technology cancels any losses out. That’s why if we look at the fish population vs. human well-being index of the Great Lakes area in 1900, and compare it to today, it appears that the fish population doesn’t matter at all (and is actually negatively correlated with human well-being).

What is missing from this analysis, is the question of how high our gains could have been otherwise, if resources had been sustainability managed.

I also think it is a reasonable position, for the more “alarmist” types, not to assume the technological explosion that occurred over the past few centuries will continue indefinitely. If it progresses anything like biological evolution, it will be in fits and starts, with the occasional dead end.

@Guy in TN

The claim isn’t that finding new things makes the suffering small in the long run. It’s that the suffering is typically small in the short run (year to 10 years).

This question isn’t even potentially answerable without specifics and even then it’s not clear how to answer that sort of counterfactual. There are tragedy of the commons cases, but for whatever reason it’s not the general rule that the tragedy case occurs.

While an interesting possibility, I’m not aware of signs of it being a serious possibility in the next few decades (and we already have technologies at hand that could be used to provide energy for a very, very long time). Seems like the flip of AI risk to me. Similarly, I think it’s hypothetically interesting, but I don’t believe it’s a productive thing for more than a few people to think about and certainly not something many people have to do anything about for the foreseeable future.

Most of the world still hasn’t reached the level of technology and infrastructure of the richest nations yet which implies that there’s still a lot of growth left to go even if technological progress suddenly slows.

I’m not wanting to strawman your argument, but this is a bold claim. Are you saying there have rarely been cases where resources were depleted, which lead to significant (albeit short-term) human suffering? The collapse of the fisheries industry put lots of people out of work. When mines run out, they create ghost towns, causing collapse of property values and forcing people to migrate. Over-exhaustion of the soil lead to the Dust Bowl. There are so many examples of this, I’m not sure where to begin.

(Edited as to not strawman you)

mdet: I think the big disagreement between cornucopians and greens is that greens feel like the problem needs to be solved by government interventions – funding research into innovations, pushing people away from consumption, subsidizing alternatives, and so on. Cornucopians trust existing market forces to do that job perfectly well, and don’t feel any additional intervention is either necessary or wise. Often this is attached to a belief that governments are rather stupid (it’s no surprise to me that Simon was a libertarian), but that’s not strictly required.

A commonly cited work on this in libertarian circles is Hayek’s “The Use of Knowledge in Society”. The full work is here, and I’ve included the most common pull quote below:

Two things: from the context of Scott’s post I was thinking of resources that are in a certain sense definitely not renewable. Oil, metals, etc. These are all only a means to some other end and at some point, you have to find a substitute for them or recycle them. By their nature, they also run out relatively quickly in any localized area. Harvesting or growing food is pretty different in the sense that it’s definitely not a finite resource unless you screw up. I would group things like fish stocks, farmland, or forests as a somewhat different category from what I was thinking of. Food overall hasn’t gotten scarcer over time though and has gotten cheaper, so even though certain foods have run out substitutability works out in our favor. We’d have more trouble if we weren’t such opportunistic omnivores though.

Second thing, I was thinking from the point of view of consumers of resources not producers. Producers may suffer somewhat more, but not in a way that is necessarily avoidable (if there is a fixed amount of gold in a local mine, harvesting it arbitrarily slowly just means you don’t have a town in the first place). The problem of producers suffering is most easily fixed by making changing jobs less painful though which seems tangential to the question of environmentalism. Local resource exhaustion was more relevant to consumers in the past when transportation networks were not nearly as good. It may still be relevant in areas with poor infrastructure. But in that case the solution may well be better roads which seems tangential to environmentalism again.

Also, when I say “typically small” I don’t mean “0”. I mean something like “much less than all the overblown claims about peak oil” or “several orders of magnitude less harmful than the last U.S. recession”. Any suffering I personally experienced would be “very, very small” in this context. Perhaps a somewhat poor choice of words.

Are there examples in modern times of mineral resources suddenly becoming so scarce that they cause great human suffering and misery?

The examples I can think of here involve wartime blockades and embargoes, but that’s not such a great model for slowly running out of some resource. In the case where we slowly run out, the price gradually goes up, and users of the resource gradually shift to substitutes or go out of business, while suppliers gradually look for ways to find more of the resource at higher cost. Also, users respond to higher prices with conservation–hybrid cars sell a lot better with $5/gallon gas than with $1/gallon gas.

quanta413:

How about fish and whale stocks. Whaling as an industry largely got killed by over-whaling and declining whale populations. Restrictions on whaling saved some species, but it’s not like we ever went back to large-scale whaling, and doing so would just finish off a bunch of whale species and leave us with no whaling industry again.

@albatross11

Thanks to the capability of transportation in modern times it’s always local.

Nauru eventually ran out of phosphate and became much poorer as a result.

In earlier times empires collapsed:

– an iron age empire in Africa collapsed when they ran out of iron, IIRC.

– Desertification of the Sahara and the middle east certainly changed things for those peoples.

At this point in time I don’t know if it’s really possible globally for resource scarcity to be that bad (barring a large volcanic or meteorite event); it would be the side effects of the more difficult resource extraction technologies that would be bad.

@ albatross11

But we don’t need whale goo for lighting lamps or for cosmetics either anymore right? It is perhaps mildly disappointing that I’ll probably never taste whale, and more disappointing that whale watching is maybe less fun than it would be with more whales though. Whale suffering is a negative too although I’d eat them so obviously I don’t place a high value on that.

It’s odd how potentially “infinite” resources like animals and plants somehow worry me more than thing that have to eventually run out (or be recycled) like oil and gold. Partly we have to eat. Partly I don’t care at all how we get power except in terms of costs, but there’s no perfect substitute for seeing or eating a particular plant or animal.

EDIT:

@anonymousskimmer

I agree with this point although in some cases new extraction technologies may be cleaner than old ones.

What you may be missing is that, on the standard economic model (going back to Harold Hotelling’s piece on depletable resources), individual incentives lead to the optimal use through time just as they do through space. If I use some flour in my cupboard to make bread it isn’t available to make noodles, but that isn’t a problem because I take account of it in deciding what to use the flour for, so there is no need for me to be warned of the depletion of my flour stock. If I pump oil and sell it today I, or my heirs, won’t be able to pump and sell that oil fifty years from now, so I take account of the depletion in deciding what to do today.

That’s a very brief sketch of a more elaborate argument–I have a more detailed account in Chapter 12 of my webbed Price Theory.

Just as in other arguments about economic efficiency, the full result depends on lots of assumptions such as complete information, rational behavior and secure property rights. But it isn’t a situation where, even if we know something is going to run out, we use it wastefully today and don’t have it tomorrow–unless today’s owners don’t have secure property rights in it, so face a “use it or lose it” choice.

Do you always account for the depletion of the flour stock? I don’t.

It seems like your model would not allow for the rational existence of a “low fuel” light in a vehicle. Why would such a light be necessary, if there’s never a need to be warned of depleting stocks?

And how did that fare for the passenger pigeon, or for fish species that have been harvested so aggressively they are no longer viable?

Yep those are all tragedy of the commons issues. Without ownership of the resource there is little incentive not to exploit it until it is gone.

Energy and mineral markets generally don’t have that problem.

Then again, even in those situations so long as the animals can be bred in captivity the market provides an incentive to create more of them. See the market response to bee colony collapse.

http://www.econtalk.org/wally-thurman-on-bees-beekeeping-and-coase/

Tuna fish stocks would be an example that seems to be headed in that direction, and I don’t know that there would be a really good substitute for tuna.

Economist to Researcher: Invent a replacement for fossile fuels. You’d be rich.

Researcher: Sorry, I have no idea how.

Economist a year later: Look, you’d be even richer! I know investors who’d even give you billions right now!

Researcher: I don’t know how. Maybe there is even a law of nature preventing this?

Economist: Just try harder!

Researcher: Sorry, nothing worked!

Economist: Doesn’t matter anymore, both of us need to become farmers, or else we will all starve.

TL/DR: What if throwing money at researchers doesn’t change laws of nature?

It’s clearly possible for some kind of resource constraint to destroy your civilization as you use up some critical irreplaceable thing for which you’re unable to find a substitute.

But honestly, fossil fuels don’t remotely look like that kind of thing. You can grow crops whose oil can be used in diesel engines, you can use power from nuclear/solar/wind/hydro to split hydrogen out from water, you can grow crops and then use fermentation and distillation to make ethanol and methanol, which are pretty high-energy-density fuels, etc.

Right, and I see that Scott has already made the same point, albeit more eloquently, further down in this thread:

Ok, but while I don’t think that we even need a concrete example in order to recognize the possibility of the scenario, Julian Simon seems to disagree and argue that this cannot happen, or rather that it is not reasonable to assume that it can happen, or a waste of time thinking about it, based on history (I have some trouble making sense of the paragraph “Will the Future Break With the Past?” that adresses this point, but hopefully a mix of the above statements comes close). And Simon is not alone in this, I heard this argument from several conservative think tanks.

Anyway, if we stick to fossil fuels for the moment as a possible example:

There are two aspects: The energy balance of the methods you mention (positive or negative? AFAIK e.g. growing crops has a negative energy balance), and the replacement of high-energy-density fuels (AFAIK ethanol cannot replace kerosine).

I can image the following future:

1. Humanity will continue to burn fossile fuels (gone is gone),

2. fossile fuels become increasingly rare, so that more and more “bad” sources like oil sands etc. are used, prices increase,

3. replacements fail in various ways (see above),

4. several technologies depending on fossile fuels experience a regression, like commercial flight and shipping traffic, while wars over sources increase,

5. prices increase further, until only sources remain that are untenable to exploit, governments limit fossil fuels to absolute necessary tasks like ambulances and the military,

6. there is an overall regression to a Renaissance like agricultural society, as alternative sources of energy become also untenable (e.g. because you need fossile fuels for their production and maintenance), after the last oil reserves are burnt in a global war over the last oil reserves.

No idea how likely this is, or if, for example, the production and maintenance of solar panels is possible without supporting technologies that depend on fossil fuels, but I think the possibility of such a scenario is sufficiently illustrated. At least one could make a decent 1970ties Sci-Fi novel out of it (a bestseller if written in 1973 after the first oil crisis. Sigh.).

Getting back to the topic of the OP: I think this point (meaning “the markets will solve this automatically”) is a point for the educated few who get hired by think tanks. The reason peak oil has faded from the public discourse is IMHO

a) topic fatigue,

b) it is obviously not a pressing problem (modulo climate change, of course).

It seems that even in the climate change discourse the point “we need to switch to renewable energy sources anyway because: peak oil, so why not now?” isn’t made very often.

Economists and Greens: we’re going to run out of oil, do something!

Researcher makes fracking and shale extraction cost effective.

Economist: good job!

Greens: we didn’t mean like that!!!

Tim van Beek:

We can produce as much electric power as we like, for many centuries, at the cost of building fission plants and doing fuel reprocessing or running breeder reactors. The cost per kWh of doing that is higher than running a coal plant, but not massively higher, and it’s demonstrably possible to do so because we have countries that produce a lot of their power via fission plants.

With electricity, we can handle agriculture that requires more energy in than out.

From a little Googling around, methane (which can definitely be produced biologically) can be compressed/liquified, at which point it has higher energy density per kg than kerosene, (but somewhat lower density per L). Sunflower oil is pretty close in energy density to kerosene. There may be reasons why these aren’t optimal jet fuels, but I’m pretty sure some similar material could work.