[Previously in sequence: Fundamental Value Differences Are Not That Fundamental, The Whole City Is Center. This post might not make a lot of sense if you haven’t read those first.]

I.

Thanks to everyone who commented on last week’s posts. Some of the best comments seemed to converge on an idea like this:

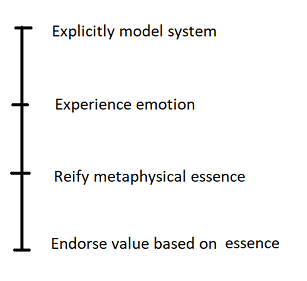

Confusing in that people who rely on lower-level features are placed higher, but the other way would have been confusing too.

Sometimes we can use theories from science and mathematics to explicitly model how a system works and what we want from it. But even the scholars who understand these insights rarely know exactly how to objectively apply them in the real world. Yet anyone who lives with others needs to be able to do these things; not just scholars but ordinary people, children, and even chimpanzees.

So sometimes we use heuristics and approximations. Evolution has given us some of them as instincts. Children learn others as practically-innate hyperpriors before they’re old enough to think about what they’re doing. And cultural evolution creates others alongside the institutions that encourage and enforce them.

In the simplest case, we just feel some kind of emotional attraction or aversion to something.

In other cases, the emotions are so compelling that we crystallize them into a sort of metaphysical essence that explains them.

And in the most complicated cases, we endorse the values implied by those metaphysical essences above and beyond whatever values we were trying to model in the first place.

Some examples:

People and animals need a diet with the right number of calories, the right macronutrient ratios, and the right vitamins and minerals. A few nutritional scientists know enough to figure out what’s going on explicitly. Everyone else has evolved instincts that guide them through this process. Hunger and satiety are such instincts; when they’re working well, they make sure someone eats as much as they need and no more. So are occasional cravings for some food with exactly the right nutrient – most common in high-nutrient-use states like pregnancy. But along with these innate heuristics, we have culturally determined ones. Everyone has a vague sense that potato chips are “unhealthy” and spinach is “healthy”, though most people can’t explain why. Instead of asking ordinary people and children to calculate their macronutrient and micronutrient profile, we ask them to eat “healthy” foods and avoid “unhealthy” foods. There’s something sort of metaphysical about this – as if “health” were a magic essence that adheres to apples. And in fact, sometimes this goes wrong and people will do things like blend a thousand apples into some hyper-pure apple-elixir to get extra health-essence – but overall it mostly works.

EXPLICIT MODEL: Trying to count how many calories and milligrams of each nutrient you get

EMOTIONAL EXPERIENCE: Feeling hungry or full

REIFIED ESSENCE: Some foods are inherently healthy or unhealthy

ENDORSED VALUE: Insisting on only eating organic foods even when those foods have no quantifiable benefit over nonorganic

Every society has some kind of punishment for people who don’t follow their norms, whether it’s ostracism or community service or beheading. There’s a good consequentialist grounding for why this is necessary, with some of the most academic work being done in the field of prisoners’ dilemmas and tit-for-tat strategies. But again, we don’t expect ordinary people, children, and chimpanzees to absorb this work. The solution is the (innate? culturally learned? some combination of both?) idea of punishment. Punishment relies on a weird metaphysical essence of moral desert; people who do bad things deserve to suffer. The balance of the Universe is somehow off when a crime goes unavenged. Take this too far and you get the Erinyes and the idea that justice is the most important thing. There are references from ancient China to Hamlet that if you have something important you need to avenge, you need to do that now or you’re a bad person. None of this follows from the game theory, but it’s a really good way to enforce the game-theoretically correct action.

EXPLICIT MODEL: Trying to figure out how to best deter antisocial behavior and optimize society

EMOTIONAL EXPERIENCE: Feeling angry when someone wrongs you

REIFIED ESSENCE: Justice: the world is out of balance when crimes go unavenged

ENDORSED VALUE: Wrongdoers must suffer whether or not that prevents future crimes

If you reward people who create value, sometimes those people will be inspired to keep creating value. This is hard for people to keep in mind, and there’s a constant temptation to confiscate other people’s things for our own enrichment. Some kind angel gave us the metaphysical idea of “deserving”, the opposite of punishment. We get rights claims like “People deserve to keep what they’ve earned”. Five thousand years of taxation have made only a partial dent in this intuition, to the point where many people still feel like something is going wrong when a producer and the value they produced are separated. Some would argue that this has gotten completely out of hand, to the point where we insist on people keeping money far past the point where it could possibly be any further incentive to them.

EXPLICIT MODEL: Letting people keep what they produce incentivizes further production

EMOTIONAL EXPERIENCE: Anger when someone takes something rightfully yours

REIFIED ESSENCE: Natural rights; governments cannot take away property rights because they are ordained by God or natural law

ENDORSED VALUE: You can’t take people’s property, whether or not this will affect further production

In past societies, STDs were a common cause of death and disfigurement. Nobody had the medical knowledge to really understand what an STD was or how to avoid getting one. But every society had some kind of complicated code of sexual purity. Usually this was designed from a male perspective, and said that women who had sex with too many other men were “impure”, virgins were especially “pure”, and a woman who had only had sex with you was “pure” relative to you. These rules protect people who follow them against STDs, and plausibly culturally evolved for that purpose (among others). But because no one knew about STDs, the rules rely on a kind of metaphysical notion of “purity” that doesn’t correspond to any real-world characteristic. For example, someone who’s had sex with a hundred people but who nevertheless never contracted an STD would seem metaphysically “impure” by the rules, but in reality safe to have sex with; this would be irrelevant to medievals who had no way to identify such people, but is very relevant now. Or: if you have good sexual protection and STDs are easily treatable, the whole “purity” system seems a lot less important, but if you think of it as a metaphysical construct important in its own right you might not realize this.

(before you tell me that STDs aren’t important enough to inspire something as universal and compelling as sexual purity laws, remember that in the pre-antibiotic era about 10% of city-dwellers had syphilis (see studies from early Mesoamerica, 1700s Chester, early 1900s London. During this period syphilis had a mortality rate of up to 20%, with survivors often permanently unhealthy and disfigured. And this is just one of many dangerous STDs!)

EXPLICIT MODEL: Figuring out the likelihood that your partners have STDs helps you avoid high-risk pairings

EMOTIONAL EXPERIENCE: Feeling grossed out at the idea of having sex with somebody who “sleeps around”

REIFIED ESSENCE: Idea of sexual purity

ENDORSED VALUE: It’s wrong to be slutty or have sex with a slutty person even if there are effective strategies for preventing STDs

Most people are happier when they’re in at least some Nature, whether this means a grand national park or just a leafy suburb with lots of chirping birds. The average person would consider a concrete lot full of Brutalist apartments a little soul-crushing. This probably comes from an evolutionary heuristic in favor of fertile areas and against barren ones; the closest chimpanzee-parseable equivalent to a concrete lot would be a desert or lava flow, where food and shelter are scarce. But nowadays we can order takeout, and the Brutalist apartment buildings provide all the shelter we need. This is probably another obsolete evolutionary relic, but it’s a very persistent one.

EXPLICIT MODEL: More plants and less gray rock means a more hospitable area with more food sources

EMOTIONAL EXPERIENCE: Contentment when surrounded by plants; depression when surrounded by concrete

REIFIED ESSENCE: Idea of “Nature”

ENDORSED VALUE: Environmentalism; the preservation of Nature for its own sake whether it benefits humans or not

Value differences, then, are people who operate at different levels of the ladder.

For example, “sexually liberated” people might use condoms, or ask their partners to check if they have STDs. But having done this, they’ll ignore the metaphysical idea of “purity”; they don’t care how many other people their partner has had sex with. And if they’re not planning to have sex with someone, they’ll ignore their “purity” full stop – having STDs doesn’t make you a bad person. These people explicitly model the complicated dynamic of STD contagion, and cast off the metaphysics as a primitive approximation they no longer have any use for.

Traditional or religious communities are more likely to endorse values based on the “purity” metaphysical essence. They understand the biology of STDs just as well as the sexually liberated people. They just don’t care. On an intellectual level, they believe that sexual purity is more than just a predictive model of STD risk, or that they’ve gained some additional function in the meantime, or that the predictive model still works better than calculating it out explicitly. Or they might not think in these terms at all, and value purity as a terminal good. Or they might be following their instincts in a way that can’t be reducible to anything at all.

Other people are somewhere in between. I know in theory that I cannot get AIDS through touching infected blood left on a sheet or chair. Absent some sort of very unlikely chain of events involving weird mouth ulcers and very fast turnaround times, I can’t even get it by rubbing the blood on food and eating it. But I would still feel more than zero trepidation about doing this. It would seem that even though I identify with the sexually-liberated explicit-complicated-dynamic-modellers, I have some weak vestige of the metaphysical purity heuristic left. This makes me more sympathetic to people with the full version. They don’t seem like weird mutants too stupid to figure out what an STD is, they feel like people with my instincts magnified a million times until they’ve become irresistible.

I have tried very hard to cultivate a vital rationalist skill called “admitting I am being an idiot while feeling no obligation to change”. That is, I feel comfortable saying I’m being very silly by objecting to touching the HIV-infected blood. If someone were to lecture me that admitting this obligates me to touch the blood or else I will have proven myself a hypocrite, I would tell them to go jump in a lake. This is important because I’m pretty sure my purity-instinct urge not to eat HIV-infected blood is stronger than my urge to be right about factual issues. If I was forced to either eat the blood, or to make up some plausible-but-false reason why the experts were wrong and blood was unsafe, I would make up the reason. And then not only would I not eat the blood – a venial sin if ever there was one – but I would be obfuscating the debate, screwing up lots of people’s ideas about epidemiology, and taking a step on the slippery slope toward becoming a dishonest and dishonorable person. I would rather just admit I’m silly.

But I think this is a hard skill, one that I often get wrong even despite frequent practice, and one I don’t expect anyone to succeed at all the time. I think some people with strong metaphysical heuristics – around HIV, around sex, around whatever – are going to get to work justifying them. If many people share a certain strong metaphysical heuristic, then there will be entire communities dedicated to researching justifications for it, coming up with philosophy around it, and reinforcing one another for being wise and good enough to believe it.

I think this is a big part of where value differences come from, and why I’ve insisted that despite the differences being real, they’re not incomprehensible. Most people have at least some level of metaphysical-STD-purity-intuition. And most people have at least some level of explicit-dynamic-modeling-of-STD-risk. Our differences come not from some people being enlightened and other people being mutants with the bizarre idea of “sluttiness” as a terminal bad, but by settling on a different part of the ladder from totally-endorsed-value-based-on-essence to total-explicit-modeling.

II.

A natural interpretation of Part I: people with explicit modeling are smart and good, people who still use metaphysical heuristics are either too hidebound to switch or too stupid to do the modeling.

I think this is partly right, but since our goal is to make value differences seem less clear-cut and fundamental, I want to make the devil’s advocate case for respecting metaphysical heuristics.

First, the heuristics are, if nothing else, proven to be compatible with continuing to live; the explicit models often suck.

Soylent uses an explicit model of nutrition to try to replace our vague heuristics about “eating healthy”. I am mostly satisfied with the quality of its research; it generally avoids stupid mistakes. It does not completely avoid them; the product has no cholesterol, because “cholesterol is bad”, but the badness of cholesterol is controversial, and even if we grant the basic truth of the statement, it applies only at the margin in the standard American diet. If you eat only one food item, you had better get that food item really right, and it turns out that having literally zero cholesterol in your diet is long-term dangerous. This was an own-goal, and a smarter explicit modeler could have avoided it. But explicit models that only work when you get everything exactly right will fail 95% of the time for geniuses and 100% of the time for the rest of us.

And even if Soylent had avoided own-goals, they still risk running up against the limit of our understanding. Decades ago, doctors invented a Soylent-like fluid to pump into the veins of patients whose digestive systems were so damaged they could not eat normally. These patients tended to get a weird form of diabetes and die. After a lot of work, the doctors discovered that chromium – of all things – was actually a really important dietary nutrient, and nobody had ever noticed before because it’s more or less impossible to run out of chromium with any diet except having synthetic fluids pumped into your veins. After years of progress on nutritional fluids, the patients who need them no longer die; we can be pretty sure we’ve found everything that’s fatal in deficiency. But these patients do tend to feel much worse, and be much less healthy, than people eating normal diets. How many mildly-important trace micronutrients are left to discover? And how many of these are or aren’t in Soylent?

We know that for some reason eating multivitamins does not work as well even for vitamin-having purposes as eating food with the relevant vitamins in them. This seems to have something to do with absorption and bioavailability, but we’re not sure what. Does Soylent have the good bioavailability of food, or the bad bioavailability of multivitamins? Nobody knows, because we still don’t quite understand how bioavailability works. All we know is that evolution seems to have found one viable solution, given that people who eat food do not immediately die. If we replace food with intelligent application our best available explicit models, we might do okay – or we might feel vaguely ill all the time because there’s something important we’re missing.

On the society-wide level, the sort of explicit-modeling that created Soylent becomes high modernism, the philosophy critiqued in James Scott’s Seeing Like A State. You subject everything to the command of a central planner, who is supposed to be able to explicitly model social dynamics, and try to prevent people from using fuzzy evolved heuristics like tradition or “the way things are”. The extreme version of this is those Young Adult Dystopias: can’t justify exactly why there should be families? Then families are just obsolete detritus of our evolutionary past, and we should form a Department Of Child-Rearing that takes all kids and subjects them to carefully-doled-out industrial-scale parenting techniques.

Second, all of our values are unjustifiable crystallizations of heuristics at some level, and we have to have some value.

One of the examples above supposes that our love of nature comes from heuristics about where to find food and water. Suppose we proved this conjecture was right. Given that we can now order pizza and bottled water to concrete lots, the heuristic is obsolete. Does this mean we should stop caring about nature, and cut down all our forests and national parks and replace them with concrete lots? Suppose this would be very profitable, and that on cost-benefit analysis this outweighs the practical economic benefits of wild spaces (carbon sinks, drug discovery from exotic species). Is there any remaining reason we still want the national parks?

Compare this to punishment-for-the-sake-of-punishment. Maybe now we can replace this with an explicit model of consequentialist punishment where we should only punish people up to the point where it’s necessary to have a safe and stable society. Returning to the dialogue:

Simplicio: I admit – I believe in punishment in a sense stronger than as a heuristic for consequentialism. I think it’s morally important, in a terminal sense, that evildoers be made to suffer for their deeds. Not suffer infinitely. But suffer some amount proportional to how much they hurt others. I want this regardless of whether it deters them or not.

Sophisticus: But that’s just reifying a weird misfiring of an obsolete heuristic about how to maintain a safe community.

Simplicio: Yup! And me wanting Yellowstone to continue to exist is just reifying a weird misfiring of an obsolete heuristic about how to get delicious elk meat. And surely you don’t want to pave over Yellowstone.

Sophisticus: I take joy in Yellowstone. That’s an emotional experience in my brain. I’m happier and more comfortable in Nature. Even if the heuristics that produced this are wrong, that feature of my brain isn’t going away any time soon. So on a consequentialist level, I can argue that Yellowstone should be maintained for my sake and the sake of everyone else who enjoys it, even though I’m not sure my enjoyment comes from a reasonable source.

Simplicio: I take joy in watching murderers and rapists get what they deserve. This is a base-level pleasure for me, just like seeing trees and mountains are for you. I am under no more imperative to justify what I want than you are.

Sophisticus: You are, though. Because you directly desire for people to suffer, which violates some of our other shared values. We have to reach reflective equilibrium among our values, and for me at least the value to wish happiness rather than suffering on other people overwhelms the desire for punishment.

Simplicio: First, I think we should be careful to frame it the way you just did: “Making people suffer for their crimes is good, but this is outweighed by other goods”. If we say it that way, it sounds no more exotic than the trolley problem.

Sophisticus: It’s at a –

Simplicio: – but second, if paving over Yellowstone would have economic benefits, then those benefits would cash out in jobs, lower housing costs, cheaper consumer goods, and the like. All of those produce utility for people. Both of our weird preferences – mine for punishment, yours for nature – satisfy some crystallized heuristic at the expense of general utility. I still fail to see how we’re different.

Sophisticus: I agree that preserving Yellowstone may incidentally fail to maximize utility. But it seems like you’re directly aiming at reducing people’s utility. That’s a pretty big difference.

Simplicio: Exactly which principle are you invoking here? The act-omission distinction? Or the principle that the morality of an act depends upon what feelings are going through your head when you do it?

Sophisticus: Um…

Simplicio: Because I think both of those are sometimes useful – as heuristics. But if you’re going crystallize those heuristics, let me have my crystallized heuristic about punishment.

Simplicio is actually being nice here. If he wanted to be especially brutal, he might ask Sophisticus something like – wait, why are we privileging utilitarianism (here being called “consequentialism”, but it seems like both of them are working from an implicitly utilitarian framework) anyway? Utilitarianism says that what’s really important is reducing suffering, but we can invent an evolutionary story for that too. We want to help other people and make them happy because that’s a useful heuristic for creating a flourishing community, being well-liked, and being likely to have other people help us in our own time of need. But some utilitarian applications of this principle go beyond that; certainly caring about effective charity for the Third World, or wild animal suffering, or anything in those realms brings us just as far from the proper domain of our help-and-don’t-harm-others heuristic as how to build a suburb with widely-available pizza delivery takes us from our nature-as-fertile-lands heuristic. Why should we privilege the harm foundation over the justice foundation? Why not just say “My urge to relieve suffering conflicts with my urge to inflict punishment on evildoers. Both urges have their place, and either can be extended out to infinity with weird results. Today I choose my urge to inflict punishment; tomorrow I might choose the other. So it goes.”

To be absolutely brutal about it:

EXPLICIT MODEL: Helping others will key me in to networks of reciprocal altruism and raise my status in the community

EMOTIONAL EXPERIENCE: Desire to help others, empathy, horror at the suffering of others

REIFIED ESSENCE: “Utility”

ENDORSED VALUE: Utilitarianism, the belief that maximizing utility is the highest good regardless of what other goods it produces

III.

Leave it there, and the fundamental-value-differences narrative starts to sound more appealing again. I reify and endorse utility, you reify and endorse punishment, now we have to fight. So I want to talk about how in principle people end up choosing what level to crystallize heuristics at.

First, let’s be blunt: dumber (here meaning either less educated or lower-IQ) people probably crystallize heuristics lower on the ladder. Chimpanzees, cavemen, and children can’t understand game theory and shouldn’t try. They usually run off instinct and taboo, and if you take that away from them they will just get confused.

There are widely replicated findings that higher-IQ and more-educated people tend to be less socially conservative. Social conservativism means a lot of things, but I think in this case it’s probably a stand-in for where you crystallize your heuristics; sexual purity intuitions are an obvious example. This makes sense; smarter people are probably more successful at explicit models, or at least have a higher estimation of their likelihood of success at such models. Smarter people do better on the Cognitive Reflection Test, a measure of whether people go with snap intuitive answers or try to explicitly model situations.

But there’s also reason to think that the more exposure someone has to a heuristic-relevant situation, the more compelling the heuristic will be. I described how my great-grandmother, usually a very kind and forgiving person, became more vengeful once someone close to her was murdered; I was able to partly replicate her experience just by vividly imagining terrible crimes happening to people close to me. This matches the cliche that “a conservative is a liberal who has been mugged; a liberal is a conservative who has been arrested”.

One of the weirdest examples of this is the germ theory of democracy, which finds the presence of tolerant multicultural individualist societies to be correlated with pathogen stress even after accounting for other relevant confounders. In this view, people at high risk of disease feel an urge to stick to people they know well – their family members, neighbors, and co-ethnics – to avoid the sort of mixing that spreads exotic pathogen strains. People at low risk of disease are more cosmopolitan, happy to receive anyone who comes around.

Related: people crystallize heuristics on a lower level when the system the heuristic is meant to model is a system they care about getting right. Consider Haidt’s Moral Foundation of Authority, which he says conservatives have and liberals lack. This fits nicely into the explicit-model-to-essence-to-endorsed-value model. The explicit reasoning is that social groups need to coordinate, and once whatever mechanism you have to produce rules has produced its rules, people need to respect and listen to them or else they’ll be in a Hobbesian state of nature. Liberals may say they’re “against authority”, but when the Vice-President of the NAACP asks an NAACP staffer to prepare a report by next week, she will probably prepare a report by the next week, not just because she’s afraid of being fired but because the NAACP will fail if it can’t handle basic tasks like “get reports prepared”. When a labor union leader tells the workers to strike, they will probably strike, even if they don’t feel like it, because they know that unless they act as a coordinated group they’ll never be able to exert any power. So:

EXPLICIT MODEL: Top-down organization is an effective way to coordinate large organizations

EMOTIONAL EXPERIENCE: Respect, deference

REIFIED ESSENCE: “Authority”, “legitimacy” (in the sense of “this guy is the rightful king, but that guy is a pretender”)

ENDORSED VALUE: Respect for authority

Frimer et al (study, popular article) have done some work on this. They find that when you ask people to imagine “Authority”, they imagine a police officer, a military commander, or some other stereotypically conservative figure who conservatives respect and liberals do not. Since liberals have little interest in making the police more effective, there’s no reason for them to “respect authority” in this case. When researchers give subjects the example of some environmental organization trying to coordinate its environmental activism, liberals are much more likely to say people should respect the authority of the organization leaders.

A more recent study (study, popular article) found similar results, although with similar caveats. They were investigating a construct called cognitive rigidity, and asked questions like “true or false: a group which tolerates too much dissent among its members cannot exist for long?”. Conservatives tend to agree with the base question more, but when you specify “an environmental group”, liberals agree more. I still think this is kind of stupid and more about liberals’ willingness to agree to anything that sounds vaguely pro-environmental. At one point they’re investigating the question “A dead hero is better than a live coward”, they change it to “When it comes to preventing global warming, a dead hero is better than a live coward”, and liberals just go ahead and agree with the statement instead of asking what the f@#k. I consider these studies very questionable and preliminary. But here are some true-or-false questions I offer to the next person to do a study like this:

A: It is dangerous to show too much mercy to people who commit crimes

B: It is dangerous to show too much mercy to people who commit gun violence

A: Barack Obama was the president, and his opponents should have treated him with respect even when they disagreed with his policies

B: Donald Trump is the president, and his opponents should treat him with respect even when they disagree with his policies

A: If I were an employee in a company, I would try to carry out the CEO’s orders even if I disagreed with them, because otherwise we would be disorderly and totally ineffective

B: If I were a member of a labor union, I would try to carry out the union leader’s policies even if I disagreed with them, because otherwise we would be disorderly and totally ineffective

I’m not asserting that liberals and conservatives would answer their respective questions exactly the same. My guess is that even in a value-neutral way, conservatives have these foundations a little more crystallized than liberals, just as they have most other heuristics a little more crystallized than liberals. But I am saying that nobody has done this experiment correctly, and I am suspicious that the groups would be closer than people think.

People can choose metaphysical heuristics or explicit models based on their own innate tendencies, their education, their intelligence, their experiences, and what kind of question we’re thinking about. Rather than talking too much about fundamental value differences, we should be asking where a given person has chosen to place themselves on the metaphysical-heuristic-to-explicit-model ladder at any particular moment.

IV.

This way of looking at things will be valuable if it helps people who crystallize heuristics at different levels understand each other. Here are a couple of common mistakes I think I see:

People who endorse values based on crystallized essences might think that people who use explicit models are weirdly and inexplicably evil, because the essentialists assume the modelers believe in the essences but don’t care about them, or prefer the opposite. If you believe in Essential Purity, then someone who doesn’t might seem like someone who supports Essential Impurity, rather than somebody working off a totally different system.

On the opposite side, if you’re a pure consequentialist, you might see someone who endorses crystallized-essence values as doing something inexplicable and evil. If you think of it as no different from what you do when you like nature, it might be easier to understand.

I have to bring these up because they’re obvious, but really I don’t see either of these that often. The main mistake I see is people on both sides having at least moderately good understanding of how to do explicit causal models, but accusing the other of being Neanderthals who only care about a crystallized-metaphysical-essence and have totally abandoned reason.

That is, I see communists assuming every single libertarian in the world is a fundamentalist about property rights and thinks they’re so sacrosanct that they must be maintained even in the face of horrible suffering, whereas they (the communists) quite reasonably want what makes a flourishing society full of happy people. Whereas the libertarians say they just want universal wealth and prosperity, whereas communists so bloody-mindedly attached to the metaphysical principle of Equality that they don’t care whether attempts to create it will lead to gulags and total economic collapse.

I see cosmopolitans believing that they want what’s best for society, but that nativists are working off an essentialist racism, where foreigners are inherently inferior in some vague metaphysical way. And the nativists, for their part, are arguing that they’re really concerned about the effects of too much immigration, but the cosmopolitans’ blind adherence to Multiculturalism as good in itself makes them unwilling to debate the real-world consequences of their actions.

Since most metaphysical heuristics are a stand-in for something real, we should expect blocs of allied people to contain some people who want the real thing, and other people who are running metaphysical heuristics that point at the thing. That is, the Tough On Crime bloc will have some members who just want to deter crime more, and other members who believe criminals deserve to suffer because of metaphysical Justice. The Soft On Crime bloc will have some members who question whether people need a ten year prison term for stealing a CD-ROM, and others who believe that prison is torture (metaphysical essence!) and so unconscionable regardless of its deterrent effect. If both sides try to position themselves as the hard-headed practical people, but weak-man the other side as having some incomprehensible metaphysics that makes them impervious to reason, that’s going to effectively shut down the possibility of debate.

Except my actual position is that the same sort of experiences that give you the metaphysical Justice intuition – having personally been a victim of crime, really caring a lot about making it as rare as possible, not being very well-educated – are also likely to make you overestimate the consequentialist value of deterring crime (and vice versa for the other side). My guess is a lot of people fluidly move back and forth between these levels, just as I would expect people who are very interested in only eating organic food to also be more likely to care about what percent RDA of vitamins are in their food. This isn’t sinister, or a reason to think that people are only claiming consequentialist arguments for their heuristics. It’s just a natural consequences of the way our values get produced and the fuzziness in everybody’s value system.

I think your spectrum model captures a large fraction of the value differences out there, but this:

assumes that, at a base level, everyone shares the aims of each particular moral dimension. I don’t think this is true. For example, how do you fit people who go to barebacking parties to get infected with HIV and be done with it, into the mold of “sexually transmitted diseases are bad, and we take different approaches to avoid them”?

Well if everyone was following ideal behaviour we wouldn’t need principles or heuristics or laws.

As an aside, I suspect that sort of thing is mostly an urban legend and blown out of proportion, but risk seeking is a thing.

I think the implication is that the statement applies in general, and that there may be groups who don’t share the common aims, but that they are so small in number as to be generally irrelevant. Or at least I don’t think Scott believes that all aims are absolutely and totally universal, no exceptions. His entire point in all of these articles seems be that we should update our priors in the direction of fewer intractable value differences among the majority of the populace.

People who want to get STDs do actually exist, but they are so extremely rare that they aren’t part of the general debate about how most people are going to get along as a society despite different ideologies.

As long as they don’t pose a major public health problem, yeah, fine.

How about people who want to “smash capitalism”? “Smash the patriarchy”? Replace all state institutions with free-market-driven companies? Do people like this exist? Do we ignore all radical fringe groups until they are no longer fringe, and start running the show?

Assuming that value differences are due to different positions on the abstraction ladder seems equivalent to saying, we kinda agree on the point we’re trying to reach, but we think different approaches are necessary to reach it – basically, we’re all mistake theorists, but don’t realize it.

That may hold for large fractions of some countries, but it does not include significant minorities in each society, and it does not hold well at all across different cultures. Ask yourself, disregarding the means necessary to achieve such a state and assuming it has somehow been brought about and functions as advertised, would you want to live

– in a SJW’s utopia?

– in an anarcho-capitalist’s utopia?

– in a communist’s utopia?

– in a devout Muslim’s utopia?

– in a devout Catholic’s utopia?

If not, why not?

Edit: some of the peculiarities of each utopia can probably be explained by claiming they take their Endorsed Values way too far and too literal. That is kind of condescending – “No, deep down you really don’t believe in submission to Almighty God, you just want an orderly society” – and it doesn’t change the fact that their utopia looks very much like my hell, because I don’t care all that much about the principle underlying their Endorsed Values, and they violate the principles I actually care about.

Utopias typically assume that the humans that inhabit them behave substantially differently from actual humans, so your question is rather nonsensical, like asking: would you enjoy being a cow?

An actual cow has needs and desires so different from mine that changing myself into a cow would mean losing everything that make me me. So at that point, that cow who used to be me might enjoy being a cow, but it wouldn’t be me enjoying being a cow. I can imagine whether I would enjoy the cow lifestyle as the human that I’m now, but then I would not actually be a cow, but merely a human in cowface.

Similarly, in a communist Utopia, people will gladly give away any benefit they get from their natural gifts to make everyone as equal as possible. If you were to place the actual me in that scenario, it would stop being a Utopia. If you were to alter my mind so I would act according to the Utopian ideal, I would stop being me/human.

Okay, fair enough, good point. So living happily in, say, a communist utopia would require people to be reshaped as good communists. If being reshaped in such a way fundamentally disagrees with what you consider worth striving for now, how is this not a fundamental value difference?

If communists would advocate some sort of plausible intervention to change humankind, I would agree that the difference can be reduced to values.

In the absence of that, I think that they suffer from the just world fallacy.

In a communist utopia, people choose to cooperate and pool their resources due to shared understanding that society is not a zero-sum game and what’s to its benefit is to their benefit (which at that point is pretty obvious, especially for people who remember giving away any benefit they got from their natural gifts to make capitalists as rich as possible). This does not require a significant change to human behavior, it merely assumes a basic human behavior that most people are already capable of (being a team player, caring family member and generally a good person to be around).

Or, to put it another way:

PS: If we were to place the actual you in that scenario, the worst you could do is be a leech, which would hardly break the system (or, for that matter, be noticed at all). To actually break the system, you would have to forcibly appropriate a significant amount of capital, which would not happen because there wouldn’t be a coercive state in place to aid you the way it aids modern-day capitalists.

@Hoopdawg

People already do that without communism. The stock market is a mechanism to allow people to pool their resources. Taxation is another way.

However, while society is not merely zero sum, it is not merely positive sum either. People naturally show both zero and positive sum behavior, allowing them to function in a complex society where you have cooperation and defection, shared goals and conflicting goals, etc.

Any societal model that is based on the assumption that everyone will only cooperate and only has shared goals, will fail.

Corruption, unwillingness to pay taxes, breaking contracts and other leeching behavior is actually pretty serious problem in many countries.

I think that you fail to appreciate that leeching is only a manageable problem in Western society because we have slowly and painfully built up institutions and culture that reward cooperation and punish defection fairly effectively.

A common mistake in communist thinking seems to be that it is believed that Western society/capitalism causes selfish behavior, rather than that it actually tries to keep it in check. This is like blaming the police for creating crime.

People with such an Utopian view of human nature have a horrible track record, as they tend to destroy existing institutions in the hope of unleashing human nature…which does happen…but not how they expect.

@Aapje

I thought along those lines for a long time but have shifted recently so I want to respond to some of these ideas here. For myself, the reason I was fairly well convinced by the points you brought up is that the histories and works I read all tended to implicitly or explicitly support those narratives, and that is because writing itself seems to only arise in state based societies with hierarchies that promote the kind of individualistic, motivated to promote the self, highly competitive mindset. That’s a lot to throw out there I know, but let me get to the more particular points. A lot of below is going to be coming from David Graeber’s Debt, James Scott’s Against the Grain, and David Freidman’s work on legal systems of different societies.

Very true! But it’s worth remembering that this exists in countries with either market provision of basic necessities (aka if you’re not trying to increase your value in the economic marketplace you can wind up starving), lots of arbitrary power for those high on the hierarchy, or most commonly both. And this is not the only way human societies are or have been organized! Just take the Amish, they don’t use police or the threat of starvation to enforce their rules but social pressure. And that’s what peasants in Europe were doing in the centuries before enclosures sealed off the common land, or what people groups in the Americas or Africa did when anthropologists studied them. Sure for extreme cases explusion could be an option, but even more common was the use of money not for normal market transactions, but as a social currency to denote guilt and a need for recompense.

But what if those institutions are incentivizing a lot of the corruption by tying so much status to material gain? These are not the only institutions that have reigned in greedy human behavior and given how a number of other societies have functioned, they don’t even seem that great at it in the grand scheme of things (the Iroquois seem to have a rather egalitarian and low corruption society for the first good example that comes to mind and Western society actively destroyed some of it’s own anti-corruption mechanisms such as criminalizing non-payment of debt).

If Western society really did try to keep selfishness in check, why does it glorify the people who benefit themselves the most (like say billionaires)? Why did it actively undermine traditional cooperative systems of credit and collective management of the commons? Why did the democratic governments of Western Europe not send support to the Catalonian anarchists who were fairly successfully building cooperative organizations, but still were fine allowing both the fascists and the Stalinists to arm their respective sides? Why did Western colonial governments force atomistic participation in markets and private property against long standing collective arrangements across Africa and Asia (not the mention the Americas before then)?

And for why so many of these ex-colonial countries have such rampant problems with corruption, conflict, and general defecting on their prisoners dilemmas, well if you go in and rip up traditional economics and social structures you’ve got the worst of all worlds. Not the limits the West has managed to work out while still encouraging atomistic capitalism, but still the individualism and self interest that’s no longer controlled by traditional society.

People with a capitalist, individualistic view of human nature also have a terrible track record. But what seems to be a better categorization to use is people who want greater amounts of centralized control of large parts of human life have a terrible track record whether we’re talking Stalin, Pinochet, or Disraeli (in India in particular, India had recurring famines under British rule that have never recurred after independence).

People who didn’t have market transactions for most goods have the track record of…being the vast majority of human existence. And some of those societies were horrible and sucked, and some were pretty nice all things considered. But when their existence and societies are really taken seriously, a lot of the typical capitalist (and indeed typical economist) framing of human motivations look a whole lot less normal and natural.

Sadly I don’t think I can fully lay out how my thinking has changed in this comment, but I recognize how natural a lot of this comment would have felt to me even a few months ago. So I want to have some dialog on this.

I’m not sure where your criticism’s at, no one would deny that capitalism is a system of economic organization that has institutions and ways of managing its excesses.

Communism would also possess institutions that would channel (tautologically) selfish motivations into prosocial behavour, it would just do it better than capitalism being a more advanced stage of economic development, just as capitalism is compared to feudalism.

Just to be clear, I don’t really buy the progression of history idea. But the problem of selfish motivations being directed pro-socially was largely dealt with pretty decently unlike Aapje’s arguments that the West is actively constraining such motivations.

As just an example of how the West actively tries to encouraging increasing selfishness rather than controlling it, this was a video shown at my work recently to encourage motivation. Beyond being a bit overwrought, this is an example of how the West “tries to keep selfishness in check.” Sure the making yourself better aspect is there, but it’s not just better than your previous self, it’s explicitly better than the other people around you. There’s no notion of collective effort here, just the individual. And this sort of motivational video is everywhere in the corporate world. In my more cynical moments I can’t help but think that if this works and I view my coworkers as competitors, I’m not going to do any collective action with them will I?

My main arguments are above this is just an illustration to make it clearer. The West pushes selfishness in ways other societies don’t. This is why The Fundamental Attribution Error is common among Western people (particularly the college educated relative elites of the West) and no where else. We aren’t discouraging defection but encouraging it, then trying to limit the worst consequences.

Is capitalism the worst system ever? No, and some anticapitalist ideas (particularly the Stalinist/Maoist ones) have been pretty bad. But the truth that some anti-capitalist ideas have been bad doesn’t get rid of the problems inherent in capitalism. We’re not at the end of history.

@Aapje

Yes? (Though yours are not good examples.) People do things now and would continue doing things. Nothing changes in that regard, which was the point.

Then it’s good that the model I speak of only requires cooperation from people who do have shared goals. Bonus: it also vastly enhances individual’s exit rights, a very efficient conflict resolution technique.

Luckily, in our communist utopia we’ve already eliminated taxes, (economic) contracts and corruptible top-down hierarchies.

Uh, no. I think that you fail to appreciate that leeching is a serious problem in Western society because we have slowly and painfully built up institutions and culture that reward leeching.

So, uh, several things:

1) As people have already pointed out, much of human behavior is tautologically selfish. Selfish is good, people should be selfish and there’s nothing about communism that would require them not to be.

2) On the other hand, of course capitalism does create a lot of harmful Molochian incentives. It’s just wrong to conflate them with a moralist notion of selfishness. They’re Molochian, if you care about actually accomplishing anything at all, you’re forced to follow them even if you’re the biggest altruist in the world.

3) Your moralist notion of selfishness is, well, moralist. That is, it’s a value based on reified essence. Funnily, this is what you accuse communists of. Even more funnily, this is what Scott just warned you not to do. Even more funnily, it’s the second time I point this out to you.

4) Finally, the notion of selfishness that our society currently pushes seems to be selectively applied to people on the bottom of the social ladder. You’re selfish if you’re in trouble and ask for help, or if you simply demand adequate reward for your work. On the other hand, if you’ve accumulated enough abstract numerical value called money, you’re allowed to force people to cater to your whims and nobody will call you selfish. So allow me to posit that, all other things aside, your notion of selfishness is simply broken.

@christhenottopher

I didn’t argue that the West discourages selfishness. I argued that it provides checks and balances, which is nearly the opposite claim. The West encourages people to act selfishly, but within a framework that tries to make pro-social behavior the most logical behavior from a selfish point of view.

Imagine two people, Bob and Mary. They each have stuff or skills that the other wants to benefit from. Bob is much stronger than Mary. In full anarchy, Bob will now take the stuff he wants from Mary by force and/or force her to work for him. Now add a police force that is stronger than Bob and which prevents Bob from stealing from Mary and/or enslaving her. Now Bob’s most logical selfish behavior is to trade with Mary. The police is a check on Bob’s behavior which makes cooperation his most logical selfish move.

In this situation the police doesn’t punish selfishness, but their existence changes the circumstances to make pro-social behavior the best selfish behavior.

—

At the end of the day, all societies have to curb their most capable and aggressive members or they will turn into an oppressive hierarchy. It’s very common for the most egalitarian societies to do this by simply keeping their most capable people down. For example, the Amish strongly discourage higher education. While this works, it obviously greatly retards human progress and prosperity. Another common method is to demand that goods are shared with everyone, which discourages taking risks and making excessive sacrifice, since the rewards for doing so go to others. So that tends to make everyone poor.

—

I would argue that (given current technology) capitalism within a social democratic framework is probably the closest you can get to: ‘from each according to their abilities, to each according to their needs.’

It seems to me that this ideal is incompatible with egalitarianism, since people are not the same. So any society that best fulfills that ideal is going to be highly unequal. The high IQ person is not to best use his abilities to be a nurse and the paraplegic has greater needs than the healthy. So at this point I already strongly disagree with a lot of more extreme socialists who believe that egalitarianism is not just compatible with, but actually results in ‘From each according to their abilities, to each according to their needs.’

An issue with maximizing this ideal is that ability does not necessarily match desire and that human nature has a large selfish element. For example, if a person enjoys being a nurse more than programming, but he can provide greater benefit to others as a programmer, then it may be better if that person sacrifices a bit of their own enjoyment for others by being a programmer. Similarly, many people may like having someone make meals for them and spoon the food into their mouths like Roman emperors, but in a society with limited supply of goods and services, it’s probably better to have society feed the paraplegic and let the healthy do the work themselves.

So given that people are not naturally sufficiently altruistic in applying their abilities for the benefit of others, nor will they only take what is offered if they actually need it more than others, we need to alter human behavior. For the first part, to get people to use their abilities for others more than they would like to, we probably need some form of coercion, where this coercion should not be excessive (in other words, it should not detract too much from the needs of that person). One solution to this would be to have central planning, where we tell a person what work to do. A problem with that solution is a lack of transparency/information. It is very hard to determine what abilities people have, how much value is provided to others and what the cost is to people to use their abilities for others. Furthermore, this form of coercion encourages people to hide their abilities when they prefer to do something different and to lie about how badly they dislike doing things. So this solution can’t really work.

A better solution is to reward people based on how much value they provide to others, preferably by having consumers give out ‘reward tokens’ based on how much value they get from a producer. This decentralized system is not adversarial like the previous solution, so it leads people to cooperate with the system, rather than resist it. However, the only reward we can give is to meet someone’s needs better, which inherently means that we better meet the needs of those who provide more value to others, which violates the second part of our goal. However, this seems like a necessary cost. We cannot solve this. What we can do is not maximally reward people for providing more value to others. For example, by using progressive taxation where we take reward tokens from the most productive and give them to the least productive, so the latter group still gets to trade in reward tokens to have their needs met.

—

If we seek to optimize the second part of the goal (‘to each according to their needs’), we have very similar problems that exist when optimizing for the first part of the goal. If we centrally allocate goods and services, we again suffer from a lack of transparency/information and again create an adversarial situation that encourages people to lie about their needs.

We can also allocate everyone the same goods, but then we run into the problem that needs differ. The bald man doesn’t need a comb. The sick person needs medicine that others do not.

If we decentralize the system, by giving everyone ‘need tokens’ with which they can buy goods and services, we get a cooperative system where those with the highest need can offer the most tokens in return for getting a good or service. It seems to me that this works a lot better.

—

One cannot really choose the decentralized solution for merely one of the goals. Choosing it for one means that you have to choose it for the other, where the the ‘reward tokens’ and ‘need tokens’ are the same thing. We call this system ‘capitalism’ and the tokens ‘money.’ A big advantage of the system is that we can tune it, to find the appropriate balance between concerns. If we want to push people to use their abilities more for the benefit of others, we can increase salary differences and/or reduce redistribution. If we want less productive people to more often have their needs met, we can do the opposite.

Anyway, my claim is not that this system is perfect. On the contrary, the system is inherently incapable of maximally achieving both goals. However, my claim is that this reflects imperfections in humanity and the world in general. I don’t see how we can have a perfect system without fixing these imperfections.

At the core, this is my objection to communism and most Utopian systems. These generally do not have plausible solutions to fix the imperfections that exist in the world or to correct for them, yet they claim that they can achieve a perfect outcome. So I dismiss them and consider them dangerous (since their believers tend to replace imperfect systems that achieve decent outcomes, with ‘perfect’ systems that achieve much worse outcomes).

@Hoopdawg

I doubt that. Imagine this scenario:

– Bob can make cookies, but not coffee. Making coffee for others costs him 1 util. Consuming a coffee gives him 10 utils.

– Mary can coffee, but not cookies. Making coffee for others costs her 1 util. Consuming a cookie gives her 10 utils.

These people have no shared goal. The perfect solution for Bob is to get coffee from Mary, but not make a cookie for Mary. The perfect solution for Mary is to get cookies from Mary, but not make coffee for Mary. The optimal utilitarian solution is for both to accept a loss of 1 util to give the other a gain of 10 utils. This can only be achieved by having a system that rewards cooperation (which for this small scale example doesn’t have to be formal, but can be a reputational informal system, but that breaks down when you scale things up).

My impression is that you falsely believe that in the above scenario, these people have a shared goal and that you thus don’t need a system to enforce cooperation (nor if you scale it up and/or make the scenario more complex).

I disagree. I believe that capitalism is at the core a system that discourages leeching and encourages altruism. However, the solution is imperfect, so you need solutions for the problems of capitalism. Those solutions in turn have problems, etc. So you have fixes for fixes for fixes, where the remaining issues are smaller and smaller after each intervention (ideally). At one point, you can no longer effectively fix the remaining issues and have to live with them. You call these Molochian and argue that you have to accept these to get things done, which I strongly agree with.

Those remaining problems are very visible and they are actually caused by capitalism and/or the fixes for capitalism, so it’s easy to blame capitalism for creating problems. It’s much harder to recognize the benefits of capitalism, so it’s easy to blame capitalism for its problems, yet not credit it (enough) for its benefits.

No, the notion that people are obligated to the labor of others only to the extent that they are willing to themselves labor for others apply to everyone. The people on top of the social ladder are usually not blamed for violating this, because the social ladder matches up with the value that people produce to others, relative well. The people who are unwilling to sacrifice for the benefit of others are relatively often found at the bottom of the social ladder, where you also find most people with very little ability to fulfill the needs of others.

We have a safety net that prevents those with little ability from having too little of their needs met, but this enables those who are capable, but refuse to, to benefit from this as well. Our choice to limit the ability of capitalism to enforce a quid-pro-quo allows people to not obey this broadly shared moral obligation. The result of this latter group are feelings of unfairness by those who pay taxes, against those who violate the quid-pro-quo, even though they can act differently. Unfortunately, those with little ability to fulfill the needs of others are often unfairly mistaken for the other group.

When people on top of the social ladder are perceived as violating the quid-pro-quo, there is often strong condemnation of those people as well. For example, many are resentful of bankers.

Money is not an arbitrary token. See my comment above. It signifies needs of others being met. So spending money to get your own needs met fulfills a quid-pro-quo. Someone gave you this money when their needs were met and now you get to get to have your own needs met by transferring this token to another person, who then can transfer this token again to have their needs met, etc, etc.

If everyone would have the same natural ability to fulfill the needs of others and has the same level of need, this would be a completely fair system. Alas, humans are diverse in both, creating an imperfection that requires compromises to the system.

@Aapje

+1 to most of your commentary here. Well said.

Perhaps I can put it more clearly.

Human inequality is a fact and provides great opportunity for trade of goods and services, since people differ in their ability to make things, how much pleasure or displeasure they feel to make those things and their desires for goods and services. If they then make trades, they greatly increase the extent to which their needs are met.

However, people don’t merely differ in which abilities they have or which needs they have, but also in their level of ability and need. So if they trade based on a quid-pro-quo model, people with high ability to meet the needs of others get more of their own needs met. People can be convinced to accept much more lop-sided deals with people they know well, as a social gift, so communism may be able to work in very small communities. However, people are generally not willing to accept hugely imbalanced trades with people they don’t have a strong social relationship with.

There are enormous advantages to not limit trades to small communities, but to scale things up to create trade networks of millions or billions of people. We cannot have strong social relationships with these people. Capitalism allow people to make these trades on a much larger scale and thus with much more efficiency, generally making people much better off. However, it does not solve the problem that people want quid-pro-quo trades with strangers. Capitalism did not create that problem however, it is a feature of human psychology.

Communism also doesn’t have a solution for this, which is why it has only ever worked in (very) small communities with strong social bonds.

Neither capitalism nor communism can make people trade on a large scale in a way that reduces the disparity between the very able and the less able, so what now?

The answer is to introduce a re-distributive system, where we let the trades happen mostly in a way where people get to act selfishly, but where we take away some of the trade tokens from the able, after they concluded the trades. Then we either give those to the less able directly or provide services for the less able with that money. This re-distributive system is (one part of) social democracy.

When we do such redistribution, we seem to be able to more easily trigger the social bonding mechanisms in people. So they are generally more willing to pay taxes to transfer wealth to strangers than to make lopsided trades with strangers. This is why redistribution is a relatively successful way to reduce inequality.

Marx wanted to fix the trade system itself, replacing capitalism with something better, rather than to add a kludge to capitalism. However, he doesn’t seem to have understood the actual problem, so he didn’t actually provide a solution. It also seems that the kludge actually works remarkably well, at least when compared to the alternatives (although not when compared with perfection).

People who have an optimistic view of what humanity can be and do may consider the downsides of mixed capitalism to be horrible and be very susceptible to (idle) promises of near-perfect systems that create enormous happiness and lack of suffering. I would advise these people to watch some Holocaust documentaries, nature documentaries with animals ripping other animals to shreds, the bleaker Werner Herzog movies, Russian movies and such. Then after they have created strong feelings within themselves of anger and/or sadness at the cruelty of nature & man and feel strong skepticism at the ability of people to find solutions, a social democratic capitalist system might no longer feel like an injustice, but instead, like an enormous human achievement*.

* Relative to our rather limited abilities, in the same way that you might applaud a handicapped person for doing something that is easy for an able person and that you thus wouldn’t applaud an able person for. If you view mankind as gods, you can only be disappointed. Better to view mankind as handicapped, infantile beings and applaud the things they do that are not the worst.

I’m not sure it isn’t the other way around. Without redistribution your existence is no threat to me, just an opportunity for mutual benefit. With redistribution part of the rules every individual is a threat to every other individual, since each wants the transfers to go to himself, not from himself.

@Aapje

I think there’s a big difference between less able and unable. I’m less able at producing wealth than Jeff Bezos by many orders of magnitude, but I am able enough to produce a materially good life and don’t have any expectation that Bezos is obligated to reduce our disparities.

Disparity itself isn’t an issue for me but absolute poverty is. It seems disparity in itself seems an issue for you, so are we at different places on the ladder? Below is my not-great attempt to build the ladder that might correspond to egalitarian values:

EXPLICIT MODEL: If someone has more than someone else, then…

EMOTIONAL EXPERIENCE: Feelings of injustice (envy?)

REIFIED ESSENCE: ??

ENDORSED VALUE: Egalitarianism through redistribution

Any thoughts on how this would get filled in? Feel free to rewrite what I already have put down. I’m initially skeptical that we’re both on the same ladder at different places, but I could be wrong.

@DavidFriedman

I am assuming that redistribution is desirable and is probably even a desire/need of many if not most people, so at that point the only question is how to do it.

One solution is to expect people to help others of their own accord, based on their own dislike of seeing people do poorly. The problem with that solution is that it only really works for people whom you know fairly well. In a society with extreme specialization, you have many small transactions with many different people, so expertly assessing the need of each person you interact with is enormously costly, if you even have access to the information.

Lowering those cost by looking for simplistic signs incentivizes people to fake signals of inability and/or poverty. People who are honest but don’t send those clear signals (for example, a person with serious medical issues that are not visible) can fail at being seen assessed correctly too. So then you probably get many false positives and negatives.

The level of cheating that will then happen will probably then greatly reduce people’s willingness to help.

So an alternative is then to have poor people enter into a more intimate & long term relationship with an organization that provides assistance. This can be a private charity or a government organization. Both have advantages and disadvantages.

—

I would argue that the main resistance that most (well off) people have when it comes to redistribution is not the loss of resources, but more whether their sacrifice will actually help the needy, rather than end up with cheaters.

Even though you may not agree as a libertarian, I think that people tend to distrust their own ability more than the ability of charities and the government. So they will more easily redistribute through those organizations than to do it entirely themselves.

@IrishDude

Very few people are truly unable to produce anything, nor are people generally willing to let people starve who can produce something, but too little to earn enough food to survive. So realistically, we are talking about a threshold of ability to earn, below which we consider them in need of aid.

Where people place this threshold is highly subjective and for many if not most people it is not about absolute poverty, but relative poverty.

The issue with putting this in a ladder is that there are different concerns that can influence where people put the ladder. For example, if your terminal value is equality of opportunity, then you will care about relative poverty much more than absolute poverty. If your terminal value is that no one dies of starvation, you will care much more about absolute poverty.

@Aapje

There’s a lot to go through so forgive the late reply. Also I had to break this up into multiple comments (4 to be exact) to avoid the length limits. Which let me say sorry for the length but I did want to include what parts of your comment I was responding to directly in my reply.

I don’t see that as an “opposite claim”. In fact it seems mostly like a rhetorical difference given that the common context of “checks and balances” comes from political science where the phrase refers to limiting powers. The powers of the presidency are not so much channeled by the Congress as discouraged from being greater than they otherwise would be (in theory anyways). Limiting/discouraging are synonyms in that context. Now you do then clarify you specifically mean channeling to pro-social impulses, but that’s not at all incompatible with at the same time encouraging selfish impulses. And what I quoted from you in my first reply you were complaining about communists saying Western civilization “causes selfish behavior”. You point about channeling does not actually dispute whether or not capitalism causes selfish behavior. You further point about the police is also hard to fit into this channeling argument. Are the police channeling crime to pro-social outcomes?

So I stand by capitalism promotes selfishness, especially in the sense of promoting individual achievements and goals over collective ones. Does capitalism also channel some of that into pro-social outcomes? Yes, but I would dispute the degree of this. Sure it’s nice when competition drives a price down, but the individualism of that competition also implicitly encourages things like, make regulations that drive competitors out of business or ignore externalities like pollution.

And here’s a problem I have with a number of your and other similar examples I see. How do we get to Bob and Mary being alone and having a one time encounter with no naturally occurring web of connections to support them? And I do mean natural quite literally here. Everyone is born from a mother, has a father that in most known societies helped in raising the child, most people have siblings, friends form either from normal encounters in a society or from the friendships families formed, and innumerable other connections a person starts making from birth.

So that changes the scenario. Now Bob and Mary are concerned about not just each other, but the support networks that lie behind one another. And they’re also worried about what their own social networks would think of their actions. And further, what if Bob and Mary are having multiple interactions with each other? That changes the incentives they have in whether or not to take the property, and we’ve never even needed to talk about police. Atomized individuals in single encounters have fundamentally different incentives than socially connected ones, and humans did NOT start out atomized. They begin connected. So in order to justify having a group who’s mandate is the use of violence rather than social pressure, you’re having to assume the kinds of people who with rare exceptions, don’t exist in the real world.

Now you could make the argument that empirically police reduce violence, but that requires comparisons between societies not a mere thought experiment with actors that very much don’t reflect real humans. Steven Pinker’s done some of that work and seems to find hunter gatherer societies at least to be more violent via archeology, but then again Nassim Taleb has scolded him for failing to use the real way to calculate long tail probabilities in a world where states made nukes.

You may retort, “models are useful for simplifying hard problems” to which I agree, but these particular simplifications seem more like handing a map to show someone how to get from Chicago to Toronto by land while not including the Great Lakes. 1/4

Curb in what ways? In all ways? That doesn’t seem to really be true. The Amish don’t try to burn the fields of their best farmers. Thee societies limit the power over other people that their best have, but tend to still highly praise accomplishments. That’s where social currencies common in these societies, which can be used as status but not for buying basic survival needs, come into play. Scientists operate cooperative structures without market competition and do pretty important work. Top scientists are highly respected, but they don’t get to arbitrarily fire other scientists. So curbing the most successful from controlling others? Yes that’s common. Curbing them from acclaim and status? That’s not universal.

Companies deciding resource distribution internally are frequently “from each according to their abilities, to each according to their needs”. I don’t pay for the paper I need to print or the computer I use. I don’t engage in a market transaction to get assistance on a project. I ask given my need and they give by their ability. Families work on this level even more, but also this happens in disasters. We use communism all the time but don’t see it because it’s so natural.

Now I know your response “but all of these are within the broader context of other market based transactions and would be impossible without those markets.” Which, sort of. In the context of our current system where lands and capital (aka the means of production) are in private hands distributed to the best profit maximizers, yes these communistic systems are dependent. But historically, advanced societies have worked with few to no markets (Pre-Alexander Persia was known for it’s total aversion to markets as was the Inca Empire…I have to give state examples because that’s where the writing/most focused archaeology has been). 2/4

Equal in what ways though? Equal in status? No society has accorded all it’s members equal social status. Equal in access to basic needs like food, shelter, and healthcare. Yeah that’s possible. High IQ people don’t stop working once they aren’t afraid of starving anymore.

A) Access to benefits in the market is not the only selfish interest people have and status can be awarded in many non-market ways. Just the acclaim of colleagues or audiences drives many without resorting to maximizing material wealth at all.

B) People are not just individuals, but also the relations they have with others. Those relations drive a lot of motivation (for instance “I need to do this to help INGROUP”)

C) That’s not what markets or capitalism do. The system tries to approximate this by rewarding those the most who can get the most value tokens from others which automatically shifts the values towards those who already have more value tokens. This is not contextless! At the dawn of markets and later of broader capitalism, wealth was not evenly distributed to then approximate the equal desires of humans. It was biased very heavily towards those who controlled the means of violence (governments and the aristocracy). The value tokens thus disproportionately have always come from the perspective of the people who gained their status through force, and even as this shifts with the rise of the bourgeois, the bourgeois were always catering disproportionately to the previously wealthy. In essence the entire economy is skewed to those who were already wealthy meaning this isn’t some neutral deciding who serves the most human needs. And yes I’m aware that the poor are catered to as well, but capitalism seeks the needs of wealth not of people. The poor get needs met info as they have wealth, and they always have some, but more production goes to the weathly than their numbers would lead one to expect. Further, because the wealthy are not merely value creators but the beneficiaries of a history of expropriation and violence, this isn’t some pure meritocratic redistribution upwards either.

All of this is also ignoring how the wealth of people in capitalism then can get turned into political influence that tips the scales more. “Doctors are rich already? Cool support restricting the number of med school slots.” “Disney makes bilions? Better extend copyright longer.” The degrees of inequality allowed and the ability of that inequality to leave the lowest losers of the race starving on the streets and dying can then be used to change the system to promote the wealth of the already wealthy.

This is a problem I have with these models you have posited, they ignore the real life context that makes them break down. 3/4

Like the centralized allocation of goods within a company?

But really this is why I prefer decentralized forms of socialism like workers cooperatives or communes. I’m far from sold on the ideas of the Stalinist line of thought. But the options aren’t only “markets or Stalin.” This is where anthropology is really valuable as alternate decentralized systems have existed and continue to exist!

This fundamentally strikes me as an “end of history” type thinking that seems a bit hubristic to be honest. “It’s not perfect but it’s the best we can have.” The diversity of human history should really give lie to that. And let’s be clear, the current capitalist system has been actively crushing many alternatives. Imperialism destroyed many different social and economic structures, anti-capitalist revolutions have been actively opposed by capitalist countries even when they weren’t threatened or at the start involved (the biggest example from my perspective is the Spanish Civil War). The world is covered in states using either central command economies (though not many of those remain) or very hierarchically run capitalist market-based economies and this narrowing of types of social and economic structures is a new development in human history. At the very least I think it’s worth backing some people trying other ideas. 4/4

@christhenottopher