This is an entry to the Adversarial Collaboration Contest by Mark Davis and Mark Webb, who sent the following introduction along with their entry:

Mark Davis is a naturopathic doctor. Naturopathic medicine is a century-old profession in the United States, but it’s small, with fewer than 10,000 NDs licensed to practice naturopathic medicine in the US in 2018. The profession has been historically highly skeptical of vaccination in general, and the modern profession is contentiously split on the topic, with vocal advocates of CDC-scheduled routine childhood vaccination and vocal dissidents both offering continuing medical education for NDs. Mark Davis’ main goal in this adversarial collaboration was to argue that there is enough reasonable doubt that routine childhood vaccines could contribute to hyper-inflammatory disease, and enough reduced harm from vaccine-preventable diseases from other medical and public health interventions (in countries with greater economic resources) that parents should be given wide latitude to make individual choices re: routine childhood vaccines despite the clear benefits to individual and public health from preventing those diseases. He became more convinced in his conversations with Mark Webb that widespread childhood vaccination is in the best interest of public health.

Mark Webb is a clinical researcher – with a current focus in oncology. He completed a PhD in immunology, specifically focused on the mechanisms driving the development of asthma. Mark Webb’s main goal in this collaboration was to argue that atopy and autoimmunity are likely not driven by vaccination, and that this idea is a distraction from finding the real causes of the increase in these diseases. Throughout the collaboration, he was reminded of the nature of safety surveillance with all drugs, and of the sensitive nature of vaccination as a medical intervention. He became persuaded that policy should not just reflect the best evidence currently available, but should also reflect a certain degree of humility that there will always be something we don’t know.

Setting the parameters of the debate

Why are vaccines the target of both intense support on the one side, and intense skepticism on the other? In part, this is because of the nature of how vaccines work. On the side supporting vaccination, there is strong evidence that vaccination changed the face of epidemic disease in the 20th century. Smallpox is effectively extinct, and polio is nearly there. What agent caused this veritable miracle? Vaccines did. Some diseases are harder to create vaccines against, like HIV or herpes, but eventually we can envision a day when vaccine development can – not just cure – but prevent huge numbers of people from ever having to worry about the deadly diseases of the past. Vaccination is clearly a proven tool for promoting public health. It has been successful at eradicating diseases that used to be endemic to various regions; and where diseases haven’t been eradicated vaccination has been very successful at preventing outbreaks and disease spread. What could possibly be bad about vaccination?

Perhaps the biggest reason vaccination has received the degree of skepticism it does is because of how it is administered. Any medical intervention that is targeted toward a high percentage of the population should be scrutinized. Indeed, it would be irresponsible not to undergo continual safety surveillance of a medical intervention that is administered to 90% or more of the population. Vaccines are also administered in multiple doses to one of the most vulnerable population categories: children. There is a strong tradition in clinical research to ensuring high levels of oversight toward children and other vulnerable populations.

Finally, vaccination is a medical intervention intended to produce a permanent effect. It is especially important to be vigilant about therapies whose effects are intended to be persistent. A drug that temporarily relieves asthma symptoms is generally less suspect than one that actually cures asthma. This is because if the expected effects disappear over time, any unknown and unexpected effects are more likely to disappear (although this is not always the case). However, if we’re looking at a treatment with long-lasting effects, unknown long-lasting effects could also appear.

This does not, in itself, mean we shouldn’t implement medical innovations meant to be permanent, targeted toward children, or that would have widespread impact. That would be like suggesting we cease all pediatric cancer research. But it is important to understand why the conversation about vaccine safety is necessarily an ongoing inquiry, not a one-off check of whether “vaccines are safe”. It is also not irrational for a subset of individuals to continue to be wary of possible missed adverse effects, no matter how much research fails to demonstrate any harm.

Before we introduce the parameters of this debate, we wish to emphasize that vaccination is a method of intervention, not one specific intervention. The statement “vaccines are safe” cannot be applied across the board to all vaccines that ever have or ever will be created, any more than you could say, “prescription drugs are safe” for all current and future prescription drugs. This question would hinge more on our confidence in the clinical approval process to ensure drug safety – an interesting question, but one entirely beyond the scope of this essay. In that sense, any general complaint you might make about prescription drug approval or safety could equally apply to any vaccine. In addition, a dozen studies demonstrating the safety of the DTaP vaccine do not demonstrate that MMR is safe. Studies for MMR have to be conducted independently, just as studies about amlodipine do not tell us whether olmesartan is safe.

These, then are the parameters surrounding vaccine safety:

- Vaccination has proven benefits to public health

- Vaccination has all the hallmarks of an intervention with the potential to cause harm

One more consideration should be noted here. In general, the benefits of widespread adoption of routine childhood vaccination in countries with fewer economic resources are clear and not disputed between the collaborators. Nations with little access to medical care are likely to see greater benefits from vaccination than nations with highly accessible medical care infrastructures. For example, an infection that would be lethal in parts of sub-Saharan Africa might be easily treated if contracted in France. Thus, a risk-benefit analysis for economically developed countries will require a more stringent requirement for clear benefit over risk than in the developing world.

From this, we will consider two proposals for economically developed nations such as the US, Europe, Canada, Japan, etc.:

- Mandatory vaccination is necessary to achieve public policy objectives for vaccines.

- Public policy should encourage parents to not vaccinate, or should at least normalize parents’ decisions to avoid vaccination.

Should vaccination be mandatory?

In order to recommend that vaccination, as a matter of public policy, should be mandatory, we would need to show that:

- Vaccination achieves a legitimate public policy objective

- This public policy objective cannot be achieved without making vaccination mandatory

When considering vaccine benefits (and indeed virtually everything about vaccines) it is important not to generalize the best or worst aspects of one vaccine with another vaccine, or a vaccine used in one socio-economic context with a vaccine used in another. The benefits of the smallpox vaccine have been significantly greater than, say, the rotavirus vaccine, and rotavirus vaccine provides more benefits in countries with few healthcare resources. Even so, rotavirus vaccination still conveys positive benefits that should not be ignored; those benefits should simply be put in context, and any potential adverse effects of rotavirus vaccination should be factored in.

Let’s continue with rotavirus for a minute to highlight what we mean. In most people who contract rotavirus, the greatest concern is dehydration. Most deaths from rotavirus currently occur in the third world, not because rotavirus isn’t transmitted in the US, but because among those who do contract rotavirus hydration therapy is highly successful. In other words, if you’re living in a place where you have to hike 3 miles to collect dirty drinking water that made you sick in the first place, you’re going to struggle with this disease. If you live in Germany and have ready access to quality healthcare services no matter where in the country you live, you’re probably going to be fine.

That doesn’t mean the rotavirus vaccine does nothing. Most people who get the vaccine will be spared the debilitating diarrhea and possibly the trip to the ER. So it’s a meaningful intervention, but it’s not really a life-or-death intervention in resource-rich countries. A similar story can be told for some – though not all – of the other vaccines on the US CDC’s recommended schedule. Generally speaking, not contracting the disease produces the positive good of preventing morbidity and other costs to individuals, but it’s mostly not a life-or-death event. This distinction is important, because “has strong benefits” can be weighed against potential downsides. On the other hand, “keeps you from dying” is hard to weigh against even debilitating or disfiguring downsides. This is basically how something like chemotherapy can become a real treatment, instead of a particularly cruel “enhanced interrogation” technique.

If you live in a totalitarian dictatorship, it’s much easier to make something mandatory. You just tell everyone to do it and if they don’t, you line them up against the wall. In a democratic republic, where the perception of the people often shapes public policy, it’s important not to make enemies of the general public. And although this is not a bar against a mandatory policy, it suggests any such policy should be tempered with the aim of ensuring it is strongly justified, is not rigidly unyielding, and therefore does not become burdensome and unpopular. In the US, in most states, mandatory public vaccination tends to meet this bar (with some qualifications).

First, the policy is not rigidly unyielding in most states. Every state in the USA has some form of mandatory vaccination policy in order for children to attend public schools. Since education is mandatory, and public schooling is freely available to all children, this amounts to a strongly coercive opt-out system. Parents who do not wish to vaccinate are forced to pay a price for their dissention by finding some other way to educate their children than through the public education system they cannot opt out of contributing to through taxation.

Some exceptions are allowed, depending on the state you live in. For example, every US state allows exemptions for medical reasons, since, for example, some small percentage of people are allergic to some of the components of vaccines. All but three states allow religious exemptions, for those whose religion prohibits vaccination (CA, MS, and WV only allow medical exemptions, representing less than 15% of the total US population). But if you don’t belong to a religion that prohibits vaccination, you’ll need to live in one of the 18 states that allow exemptions for personal beliefs as well (these include AR, AZ, CO, ID, LA, ME, MI, MN, MO, ND, OH, OK, OR, PA, TX, UT, WA, and WI representing about 35% of the US population) if you want your children to attend public school without getting them vaccinated.

There is, perhaps, a general concern about totalitarian tendencies here. The concern is that, with physicians as gatekeepers of medical care, they are in a particularly coercive position when it comes to individual patient decisions. Say a patient is strongly opposed to some aspect of vaccination, and wants to opt out of the system. When they try to do this, perhaps their doctor refuses to play along, preferring to use their position of authority to compel the parents to following standardized guidelines. This is certainly the case in some situations, but is it the norm? According to a survey of Washington State pediatricians in 2011, a majority reported they are willing to follow an alternative vaccination schedule to the one advocated by the CDC if a parent requests one. Interestingly, 77% of the pediatricians surveyed reported parents sometimes or frequently make these requests. So not only are parents asking pediatricians to follow different guidance than what the CDC recommendations, most pediatricians report that they are willing to comply. As these are statistical results, this means that there are some parents asking to follow a different vaccine schedule who are refused by their pediatrician; but it appears that (at least from what we know of Washington State) these parents need only go looking for a readily-available second opinion and they will find a pediatrician who is willing to go along with the vaccine schedule they prefer.

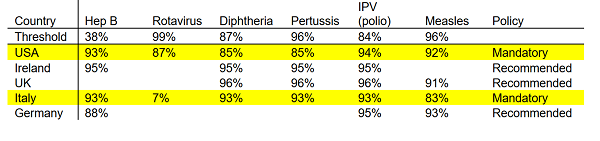

Despite this, the argument, “vaccination should be mandatory” must contend with one uncomfortable fact: in many European nations vaccination isn’t mandatory, and those nations often achieve higher vaccination rates than in the US. The table below lists different nations’ vaccination rates. In addition to comparing these rates to one another, it is necessary to compare rates to the threshold required for “herd immunity”. One compelling public health argument in favor of vaccination is the potential of a vaccine to stop the spread of a disease because an infected person will be unlikely to spread the infection prior to recovery because everyone they meet is already immune. It’s a little more complicated than this, but fortunately it can be easily simplified into one number that represents the percentage of the population that needs to be vaccinated in order to ensure the disease will slowly die out faster than it can spread. This is represented by the “threshold” row in the table below.

Notice that for hepatitis B less than 40% of the population needs to be vaccinated in order to achieve herd immunity. Hepatitis B is usually the first vaccine babies get, with current recommendations being to give this prior to leaving the hospital. The specifics of why this vaccine is recommended this early are probably beyond our scope, but from the perspective of “intended to stop the spread of the disease” we’re probably more aggressive than we need to be. Meanwhile, for rotavirus nearly everyone has to get the vaccine in order to achieve herd immunity. We’d have to live in a totalitarian dictatorship to get the kind of levels we’d need to eradicate rotavirus through vaccination alone. It’s important here to note that the vaccine does confer protection to an individual who receives it. But since rotavirus is so highly contagious, really high vaccination rates are not enough to stop the spread of the disease. Thus, as a personal healthcare decision the rotavirus vaccine appears highly attractive. However, as a matter of public policy rotavirus vaccination cannot be expected to prevent outbreaks. It might make them a little less severe, or perhaps they’ll spread more slowly, but they’ll still happen.

The important observation from the table above, however, is that nations like Ireland and the UK have much higher vaccination rates than the US without making them mandatory. Often, these rates are much higher. For example, the US rate of vaccination against diphtheria is below what is required to achieve herd immunity, in contrast to diphtheria vaccination rates in Ireland and the UK, which exceed the level required for herd immunity. This is not to say that eliminating mandatory vaccination will increase vaccination rates. Each nation has different, and unique, health care systems, laws, policies, and behavioral norms. This is probably more complicated than “Let’s just copy what the Germans are doing.” But it is not possible to argue, “Without mandatory vaccination we cannot achieve herd immunity; people will be dying of disease in the streets!” Although we should be cautious about sudden, dramatic changes to a system that is largely working, both authors concede that in developed nations such as the US mandatory vaccination is probably not necessary to achieve public health objectives.

Should health authorities normalize parental decisions not to vaccinate?

Any medical intervention comes with some level of risk, both known and unknown. For vaccination, the most common, well-documented, known risk is the potential for an allergic response to some component of the vaccine. The most common allergic component is egg, and people with severe egg allergies are instructed to consult their physician prior to vaccination. How common are allergies to vaccines? A good estimate is about 3 per one million doses. This would be the equivalent of about 200 people in France, or 35 in the US state of Ohio. This is the biggest recognized, known risk of vaccines. But are there significant unrecognized risks of vaccination that could impact the risk/benefit assessment of vaccine safety?

In order to make a general recommendation against vaccination as a matter of public policy, any identified harm would need to outweigh the benefits which those vaccines confer upon their recipients. There are a number of theories about potential harm that could come from vaccines. Much ink has been spilled about vaccines and autism, and it is not our intent to cover that ground again here. Both authors agreed that the evidence does not support a link between vaccines and autism.

There is another, more subtle linkage that we would like to consider here; this is the hypothesis that vaccines might contribute to autoimmune and autoinflammatory diseases such as multiple sclerosis, type I diabetes, inflammatory bowel disease, rheumatoid arthritis, etc., or to atopic diseases such as asthma, eczema, and food allergies. These diseases have been increasing for decades – the same decades during which we have increasingly been administering more vaccines, earlier and earlier in childhood and into infancy. Thus, it is appropriate to consider the possibility of a causal link between these two phenomena: do vaccines lead to autoimmune and allergic disease?

Are kids who are vaccinated more likely to develop these immune system diseases? Despite a large number of studies into this area, the results so far have been mixed. On one hand you could argue, as above, that vaccines lead to increases in immune system diseases. And indeed, you can find researchers who have demonstrated just such a link for DPT, tetanus, MMR, etc.

- DPT (article; article)

- Tetanus specifically

- Tuberculosis (BCG vaccination doesn’t prevent allergic disorders, but positive TB test does)

- Measles (article; article)

Meanwhile, other researchers have hypothesized that vaccination protects against development of allergic disease and autoimmunity. How might this be? There is strong evidence that increased antibiotic use in early childhood is associated with increases in developing immune system diseases; childhood use of antibiotics can shift the balance of commensal bacteria in a way the hygiene hypothesis would predict makes you more susceptible to immune system diseases. So it’s also possible that not vaccinating could lead to increased antibiotics use if your child does get infected with measles, mumps, pertussis, etc. Regardless of whether antibiotics are the mediating factor, some studies indicate certain vaccines having a protective effect against atopy:

- Tuberculosis (meta-analysis)

- Measles (article; article)

- MMR (article)

Finally, some studies find no difference between vaccination and natural infection in development of immune system disease:

- Multiple vaccines (article; article)

- DPT (as a marker for all vaccines)

- Pertussis (We were only able to locate one genuine placebo-controlled RCT of a routine childhood vaccine in which the authors looked for atopy – they found no significant difference in atopy between the placebo and real pertussis vaccine groups at ages two and a half and seven)

This topic has been reviewed multiple times in the scientific literature, and the conclusions have been the same each time: there is no demonstrable impact of vaccines driving immune system diseases. Given these conflicting studies, we can’t say that there is convincing evidence that vaccines either cause increased immune system disease or that they protect against development of these diseases.

One hypothesis for how vaccines might contribute to the rise in atopy and autoimmunity side-steps most of the evidence cited above. These articles look at whether vaccination itself causes allergic disease, but what if the opposite is true – not vaccinating protects against allergic disease?

Hygiene Hypothesis

What causes the development of autoimmune, autoinflammatory, and atopic disease? A full answer to that question – one that could lead to prevention of these diseases – would probably be worth at least a Nobel prize in medicine; which is to say we don’t entirely understand it. However, the current leading explanation in vogue amongst immunologists and epidemiologists who study the recent trend in which we see these diseases increasing dramatically in the developed world is call the hygiene hypothesis.

First proposed about thirty years ago, the hygiene hypothesis is the idea that some of the bacterial and parasitic infections that modern medical technology has eliminated might have been performing an important function in the human immune system – and when you take them away you start seeing problems. For example, if you go back 5,000 years in human history, few people would be completely free of parasitic infections, such as hookworm or whipworm. These parasites might make you mildly ill after you first get infected, but so long as your immune system maintains control of the infestation you may not notice it. There is a constant, low-grade battle between your immune system and the parasite. This battle doesn’t just go on your entire life, but has gone on for generations of humans (and their common ancestors), such that this is the normal state of affairs. Fast forward 5,000 years, and modern water treatment suddenly prevents millions of people from ever experiencing a type of infection that was a constant throughout humanity’s evolution. As a result, the immune system doesn’t know what to target. There has never been a time when there was nothing to fight, so it begins to fight itself, accidentally.

This hypothesis isn’t just high-level theoretical hand-waving. Parasites, such as hookworm, have been shown to induce the same kind of immune mediators that are commonly seen in autoimmune diseases. In fact, some people with diverse autoimmune, allergic and autoinflammatory conditions have started intentionally infecting themselves with hookworm. Based in part on this movement, clinical trials have been conducted, and more are currently under way investigating whether re-introducing parasitic infections such as hookworm can be used to treat Crohn’s and other autoimmune diseases.

If the hygiene hypothesis is correct, and removing certain persistent infections is driving the increase in autoimmunity, autoinflammation, and atopy; does that mean there is a hygiene hypothesis explanation that links vaccination with these diseases?

This hypothesis is much more difficult to test, in the case of vaccination, because it’s not saying the vaccine itself causes allergy and autoimmunity. Instead, it argues that getting rid of diseases such as measles and pertussis causes the increase in allergy and autoimmunity. Thus, it doesn’t really matter whether you get the vaccine or not, what matters is whether you get measles or pertussis or not. If everyone around you gets vaccinated, herd immunity will kick in – the very effect public policy is looking to achieve – and you will never get the chance to catch measles. So no matter how large or well-designed or randomized/controlled, a study that compares US children who are vaccinated with those who aren’t won’t be able to test the hypothesis that endemic measles outbreaks protect against development of allergies and autoimmunity.

The closest we can come to addressing this question are some of the measles studies cited above. One of these compared individuals in Guinea-Bissau who were either naturally exposed to measles or who had been vaccinated; they identified a protective effect for natural measles exposure. Meanwhile, another study in Finland made a similar comparison and found natural measles infection exacerbated atopy and allergic disease. The problem with this approach is that it doesn’t just compare vaccination with not vaccinating – it compares people who don’t vaccinate with those who do. These are not necessarily the same. For example, people with access to vaccines in a nation such as Guinea-Bissau might be of a different socio-economic status than people with no access to vaccines. And socio-economic status has been identified as a factor in development of atopy and autoimmunity.

One way to look at this is to ask whether vaccinated children have different immune system markers, such that they look like they are more susceptible to developing immune system diseases. Researchers at the University of British Columbia looked for exactly this kind of change in a recent study. They took blood from children who had or had not been vaccinated and looked at whether these children’s circulating immune system cells differed from each other. They did not find any of the differences we would expect to find if vaccines caused a general shift in a vaccinated person’s immune system. This study should be taken with a large grain of salt however, as the sample size was smaller than expected, due to the difficulty of recruiting unvaccinated children.

A more targeted way to test this hypothesis would be to randomly assign children to receive one or multiple vaccinations and compare to children who receive no vaccination, then expose all the children to the disease(s) they were vaccinated against and check whether they develop various types of atopic and autoimmune disease. This would have to be done in a nation that currently has endemic levels of the disease in question and/or frequent outbreaks. Also, a nation with no scruples about conducting experiments on children in which you intentionally expose them to infectious agents at an early age.

This does not mean the hypothesis cannot be tested, but it will be a difficult hypothesis to test consistently, and the current state of the evidence suggests a high level of disagreement. In advance of such evidence, we might ask: What are the implications if this hypothesis were confirmed? Would that mean deciding whether to accept – even encourage – endemic disease burdens such as measles, polio, pertussis, etc.? There is no reason to believe that the hygiene hypothesis requires specific bacterial or parasitic infections in order to promote the development of a healthy immune system. It is likely that whole classes of commensal bacteria are protective against the development of atopy and autoimmunity. If there were a group of people, living in a nation that has achieved herd immunity to many of the infectious agents discussed above, and that had rates of allergy and autoimmunity significantly below that of the rest of the population we might study that group to determine whether they are exposed to commensal agents that are protective against atopy and autoimmunity.

Fortunately, the Amish in the US provide an excellent example of just such a case. They experience almost none of the diseases we associate with developed nations. They have far less cancer, asthma, food allergies, MS, etc. You might think, “but that’s because they don’t vaccinate!” except that they do vaccinate. Different communities vary, as each Amish community makes its own rules about what aspects of modern technology to adopt, but one survey of the Amish suggests that about 85% of Amish children are receiving vaccinations. Additional anecdotal evidence suggests this may be a lower bound, but even if we assume 85% of Amish children are getting vaccinated we have to wonder why they see such low rates of modern diseases. Sure, they aren’t at the 90-95% of most of the rest of the country, but it’s hard to see how that extra 5-10% vaccination rate could be leading to such a huge increase in autoimmune diseases – especially without significant numbers of outbreaks running through their communities. Maybe it’s just something about the Amish?

It’s not just something about the Amish. An early observation about the hygiene hypothesis is that people who live on farms have a much lower rate of developing immune system disorders. The belief is that this is because they are more frequently exposed to environmental bacteria and parasites.

A group of researchers identified a different German religious sect, called the Hutterites, which also engages in regular farming. They are closely related to the Amish, and came from similar parts Germany at similar times. However the norms of the Hutterites dictate a much lower interaction between livestock and children/pregnant women (most hygiene hypothesis evidence suggests prenatal, neonatal, up through young childhood exposure is the critical exposure period). This genetically similar group, who had less early-life exposure to the farm environment than the Amish, gets asthma at a rate 5-7 times higher than Amish farmers (Amish asthma rate is 2-3%, Hutterite asthma rate is 15%). The researchers then took dust from the Amish barns and forced mice to breathe it in. They found the dust protected the mice from developing an experimentally-induced allergic response, and that it caused real, measurable changes in the immune systems of these mice, consistent with what we see in humans who are less allergic, and consistent with the differences they saw in the Amish farmers who had low allergic disease compared to the Hutterites.

But not everyone can live on farms (anymore) so current research is also focused at discovering which commensal bacteria humans need to protect against developing immune system diseases. This is similar to the idea of taking the dust from Amish farms, but consistent treatments require us to actually know what elements of the dust actually matter to preventing disease. It’s possible, for example, that modern lifestyles reduce exposure to exposure to mycobacteria. Some promising attempts have been made at reintroduction of killed mycobacteria into atopic individuals. This approach is akin to creating a vaccine against atopic disease, though more recent research has focused on changing the balance of live bacteria instead of simply introducing killed bacteria. This approach attempts to retrain the all-important gut commensal balance through techniques such as fecal microbiota transplantation (poop transplants) or investigating dietary changes that could help push the balance toward protective commensal bacteria and away from sensitizing commensals.

If we create a vaccine that specifically targets the commensal bacteria, or parasites that protect you from developing immune system diseases, we might suspect that vaccine of directly contributing to people who receive it developing those diseases. For example, one such helminth has been the target of recent vaccine development due to the significant harms it causes in the developing world; thus there is a concern on one hand of the persistent symptoms of infection caused by the hookworm infection, and a concern on the other of increasing the risk of allergic infection. In the developing world, where iron deficiency is a major cause of morbidity (large hookworm infections cause iron deficiency as they feed off the blood of hosts), development of an anti-hookworm vaccine could be a significantly beneficial intervention. In economically developed nations these types of infections were mostly eliminated when water treatment eliminated the fecal-oral route many pathogens use to spread from host to host.

Let’s revisit the implications of the hypothesis that the elimination of endemic diseases by vaccines causes an increase in atopy and autoimmunity. Currently, there is not strong evidence that vaccines drive autoimmunity and atopy, although additional research should be done in this area – focusing on disease exposure and not just vaccination status. Even if such a link were to be established in the future, is cessation of vaccination the best approach? Perhaps a better solution to the rise of atopy and autoimmunity is not to actively encourage the return of endemic diseases that are associated with other significant harms, but to encourage exposure to commensal bacteria and parasites that do not come with significant associated morbidity and mortality, such as those that help prevent atopy and autoimmunity in the Amish.

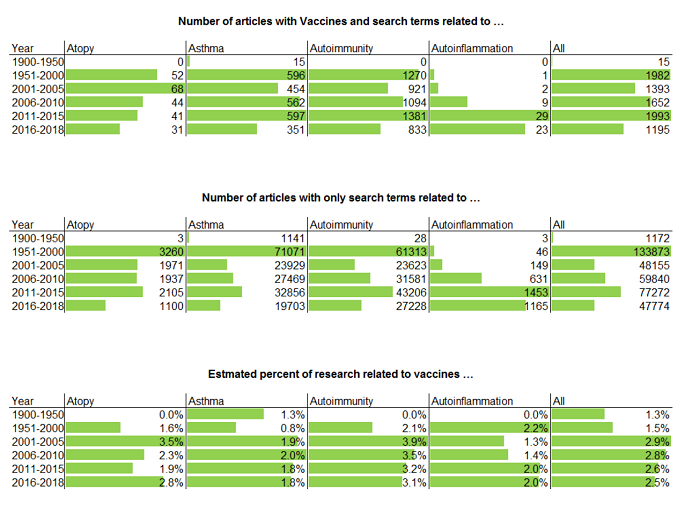

For the vaccines currently recommended today, we haven’t seen convincing evidence of long-lasting or permanent negative side effects. It is important that the medical community continue to monitor vaccines to confirm the relative safety of vaccination, and the evidence of the academic literature is that this is actively happening. Every year, many articles posted to PubMed confirm that ongoing surveillance of vaccine safety is being actively pursued by the scientific research community.

This is appropriate, as we do not ever expect to finally “prove” that vaccines are not harmful. While it is possible to obtain support for a positive declaration such as, “vaccines are effective”, the only way to “prove a negative” with the scientific method is to fail to find support after looking for it. With vaccines, it is important to remember that this is a daunting task. There are many vaccines currently in use, and there are many possible harms to be investigated. In addition, new vaccines are currently being developed, such that we should expect to continue to investigate the safety of various specific vaccines for the foreseeable future.

Conclusions

In the first question, we assessed whether vaccination, as a matter of public policy, should be made mandatory. In essence, this asks whether the benefits to vaccination are sufficiently great that the decision of whether to vaccination should be removed from individual decision-making. Given the sensitive nature of a policy that essentially amounts to dictating private parental medical decisions, we adopted a standard similar to the US Supreme Court’s “strict scrutiny” standard: is it a compelling public health interest, and is it narrowly tailored? This is not generally the standard currently adopted by policy makers today. Mandatory vaccination failed this test, in that it is not narrowly tailored, since herd immunity can be achieved without making vaccination mandatory.

The case of California is an interesting example of how public policy is currently set in regards to vaccination. In 2014, California’s measles vaccination rate was below what is required for herd immunity, and there was a subsequent outbreak of measles at Disneyland. This was a high-profile event. In response, vaccine proponents argued that California’s laws should be strengthened to eliminate the personal and religious exemptions for vaccinations that were then in place. After the law was passed, despite a suspiciously large increase in medical exemptions, vaccination rates rose above the level required to achieve herd immunity, both at the statewide and at the county level. This law also sparked protests from parents who saw the law as removing the rights of parents to make medical decisions for their children. The debate was highly contentious, and continues to be a source of some political animosity.

According to our analysis, future public debates about vaccination do not have to follow this pattern. It is sensible, given the nature of vaccination as a medical intervention, to be skeptical that safety surveillance may have missed something important with respect to vaccines. It is also entirely possible to achieve vaccination rates sufficient to achieve herd immunity without removing medical decision-making ability from parents. A better approach might be to study models such as those of the UK and Germany. In the UK, vaccination is strongly recommended, and vaccines are provided at no cost to the individual. Germany, meanwhile, also strongly recommends vaccination but does not pay for vaccines. A more thorough study of social norms and other factors influencing vaccination rates could provide alternative approaches to the drive for mandatory vaccination, and help alleviate this front of the culture war. This study of alternatives to mandates should be undertaken prior to the next high-profile event, in order to provide policy-makers with a ready alternative that can foment good will between those wary of vaccination and those wary of the potential for outbreaks.

In the second question, we asked whether the public policy toward vaccination should be reversed. It is entirely understandable for concerned parents to adopt a “precautionary principle” approach to vaccination – given the nature of vaccination as a universal medical intervention targeted at babies and young children. However, as a matter of public policy, a general “precautionary principle” approach cannot be recommended in light of the proven harms vaccines protect against. At this time, there is not sufficient evidence that vaccination causes real harms – despite attempts to investigate various mechanisms by which they are theorized to cause harm. This does not mean vaccines cause no harm, but like any medical intervention, we require each vaccine to undergo initial testing for safety and efficacy before regulatory approval, then additional surveillance afterward.

Based on what we currently know, vaccines are an important element of disease control and eradication. Public policy may not require mandatory vaccination, but including recommendations for parents to vaccinate children is a legitimate public policy objective. Vaccine safety and vaccine surveillance are also important and legitimate. Many primary research articles are published each year investigating vaccine risks, and looking for unknown harms.

Ultimately, the question of whether something is “safe” can only ever be either answered:

- “no, we have evidence that it causes significant harm” or

- “we don’t have evidence that it causes significant harm”.

Meanwhile, many of the potential benefits of vaccination are recognized at the level of community adoption – which introduces a coordination problem. Thus, the central conflict we encounter in this area is between individuals who wish to invoke the precautionary principle for themselves and for their families, versus community standards that seek to eliminate a known danger. This conflict (between individual freedom to dissent in order to avoid fat-tailed risk versus a level of community solidarity necessary to combat societal ills) is common to many problems besides vaccination.

We believe this coordination problem may be largely resolved without restricting individual freedom. Individuals who wish to invoke the precautionary principle for themselves and their families should not be penalized for doing so.

As an anarchist (possibly transitioning back to libertarianism / minarchism) of course my answer is “no”. But I’ll be goddamned if I’ll let your little plague rat come over to my house.

This collaboration was a huge disappointment. There is little or no evidence cited to support the stated conclusion, and in fact, the essay seems to be arguing against itself.

You conclude with “mandates are not necessary to achieve high vaccination rates” despite citing an example (the California case) which shows the opposite. The only evidence ever offered in favor of the conclusion is the higher vaccination rates in Europe, but the essay never addresses confounding factors or seriously argues that the US could magically turn into Germany.

Possibly stupid idea, but I’ll put it out there anyway: Why not implement cap-and-trade for vaccination? Say “we need herd immunity of X%, and population due for this vaccine of Y, so we have X*Y vouchers. The first N are given to those with religious and medical exemptions (with more stringent controls to prevent the issues from CA), and the remaining exemptions (X*Y-N) are randomly distributed to those in the target population (or their guardians).” They can give them away, trade them, sell them, set fire to them, etc.

Of course, there’s all kinds of complication, but this way people can exercise their choice without endangering others, but must also bear a proportional cost of that choice. If there are few anti-vaxxers in a given market, the exemptions would be low-demand, low-cost items reflecting the minimal danger such a small anti-vax population would pose, while in markets with lots of anti-vaxxers, the high demand and thus high cost of vouchers would force them to reckon with the societal costs of their choices, and force them to “put their money where their mouth is” so to speak. Plus, it’s like the lottery – a tax on stupid people.

There’s tons of implementation difficulties (how big are the markets, how to prevent excessive religion & medical exemptions, etc.), but at the least it preserves some aspect of choice while making the cost of that choice proportionate to the externality imposed on others.

This was really, really good, with two caveats: the formatting of the abstract and the headers is needlessly loud, and the end of the essay, as my highschool history teacher once said, falls off a cliff. There should probably be an additional paragraph at the end, or the last one should be expanded a bit.

That said, I think this essay sets the standard for what a “good” project of this sort should look like. It properly identifies two bounds in policy space, clearly states what sort of evidence is needed to support the selection of a policy on either side of those bounds, and then discusses the state of the evidence and the actually-in-use policy in terms of the identified bounds.

I appreciate Mark and Mark explaining their initial viewpoint in the beginning as well as how their views changed as a result of this collaboration.

One thing I am certainly curious about is in the European model where voluntary vaccination rates in certain jurisdictions are higher than in the US, how much of that could be confounded or due to public/subsidized health-care compared to the US? I’m certain Medicaid cover vaccinations for children of poor families, but then after a certain income level,

Hungary has a very high infant vaccination rate. This entry mentions “we’d have to live in a totalitarian dictatorship to get the kind of levels”, which might point in the direction of how that tradition started.

I was born in 1985, and as an infant I got vaccines against at least diphteria, polio, measles, tubercolosis by the BCG vaccine, rubella, and tetanus. (I do not claim to be effectively protected against all these diseases, in particular, the tetanus vaccine is known to give protection only for a short time period. There are a few more vaccines I got as an infant or as a child, but I don’t have adequate documentation to tell what exactly.) People of my age are typically also vaccinated against tick-based encaphelitis, but I am exempted for medical reasons (meaning that I got very sick for an unknown reason shortly after I got the first of multiple shots). The set of vaccines people get have changed since, as https://www.xkcd.com/1950/ illustrates: I am among the Brians, I got varicella as a child because there was no vaccination yet. I am not familiar with the actual policies, neither the ones when I was an infant nor the current ones, but I know there’s been public campaigns to convince adults to get certain vaccines, including the one against Hepatitis B and yearly flu vaccines. Most adults have to pay part of the cost of these vaccines, but certain people in the endangered population get them for free, eg. yearly flu vaccines are free for the elderly and for teachers in primary education.

Obviously the publicity campaigns are there because not enough people get the flu vaccines to prevent epidemic outbreaks in all years. Basically the vaccine situation is much worse for adults than for children.

—–

In Hungary, pet dogs get mandatory rabies vaccination. There are rules for mandatory vaccinations to pets in many countries. These rules are taken so seriously that it is well-known that bureaucracy makes transporting pets through country borders in Europe very difficult, because every country requires different forms of documentation from vets. So I have a question. Do you happen to know of any research studies on how vaccination affects immune system diseases in dogs?

> In order to recommend that vaccination, as a matter of public policy, should be mandatory, we would need >to show that:

> 1) Vaccination achieves a legitimate public policy objective

> 2) This public policy objective cannot be achieved without making vaccination mandatory

You would also need to show that the legitimate public policy objective is worth the costs of regulation–both the financial costs and more fuzzy costs to freedom/legitimacy.

A bad question. The epidemiological differences between the hundreds of different {disease, vaccine} pairs are overwhelmingly important and the question makes no distinctions. The whole thing can be framed more usefully as:

(1) which vaccines should be mandatory under which circumstances?

(2) which non-mandatory vaccines should be encouraged and/or subsidized?

(3) who should decide whether to add or remove a vaccine for the list in (1)?

Once you notice that there are hundreds of vaccines, only a small fraction of which are mandatory, and that there are some vaccines on the list which probably don’t belong there, you will be better equipped to debate this than most of the anti-vaxxers, who lump all vaccines together, and than most of the anti-anti-vaxxers, who never get beyond “the science is settled” and imagine that the list of mandated and recommended vaccines was immaculately conceived rather than hammered out by a messy process involving lots of committees and diverging interests.

On libertarian principles, I’m against mandating vaccinations except when there is a public health emergency. Achieving herd immunity against deadly or permanently disabling diseases is the only reason I would accept mandating vaccinations, but the worst infectious diseases rarely meet this condition (measles is the best example to argue for mandatory vaccination today, but only because smallpox and polio are no more).

That is a fair point. Not all vaccines should be mandatory, certainly.

I thank the authors for their work in what must have been a difficult task. I am a vaccine supporter, but, their review has made me curious as to whether vaccine mandates are the most effective pathway to meeting public health goals via widespread vaccine adoption. They rightly point out that any intervention which permanently modifies the body of a child must be subjected to intense scrutiny.

However, all in all I found this review extremely disappointing. The review fails to describe the well-described beneficial effects of vaccinations, and utilizes faulty reasoning in justifying concerns that vaccines could possibly cause significant harm.

I. The review does not adequately describe the benefits of vaccination

Any medical decision must appropriately balance risk and benefit – meaning, expected value of the treatment of disease, and expected value of the adverse effects of treatment. The authors have attempted to describe a medical decision without making any serious attempt at describing the benefits. This is negligent.

1. Basic public health aims remain undescribed and unaddressed

The very first item of discussion is “1. Vaccination achieves a legitimate public policy objective.” I found no explicit description of that objective.

Despite their stated aims, there is basically no discussion of the consequences of tetanus, diphtheria, pertussis, measles, mumps, rubella, meningococcus, polio, smallpox, H flu, pneumococcus, hepatitis B, hepatitis A, or varicella. There are cursory references to “smallpox is gone, and polio might be soon,” but the review does not describe why we even want smallpox and polio to disappear – this is a staggering oversight.

2. Rotavirus symptomatology is inadequately (and misleadingly) described

The review also describes that, in the third world, rotavirus vaccination can prevent deaths related to dehydration. This falsely implies that the only manifestation of rotavirus infection is diarrhea, and that the clinical syndrome associated with rotavirus vaccination is inconsequential in developed nations such as the US.

Epidemiologically, the authors underestimate the burden imposed by rotavirus gastroenteritis. From Prevention of rotavirus gastroenteritis among infants and children: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). MMWR Recomm Rep. 2009:

Symptomatologically, the authors fail to describe the entire profile of rotavirus infection. Rotavirus can cause encephalitis, meningitis, and seizures in 2-3% of children. Furthermore, it can cause intussusception, at higher rates than rotavirus vaccination. From Potential Intussusception Risk Versus Benefits of Rotavirus Vaccination in the United States Pediatric Infectious Disease Journal 2013 :

3. Straw argument regarding the public health benefits conferred by vaccination

The review states that “We’d have to live in a totalitarian dictatorship to get the kind of levels we’d need to eradicate rotavirus through vaccination alone… as a matter of public policy rotavirus vaccination cannot be expected to prevent outbreaks.” This is a motte-and-bailey – eradication of rotavirus may not be achievable, but that does not mean the same thing as preventing outbreaks. Neither does it mean the same thing as (or necessary for) significantly reducing healthcare utilization and bad outcomes. The authors essentially claim “If rotavirus is too virulent to be eradicated, it’s not worth vaccinating for from a public health standpoint” and that claim is utterly false.

It is well-demonstrated that rotavirus vaccination has significantly reduced healthcare utilization. See :

Decline and change in seasonality of US rotavirus activity after the introduction of rotavirus vaccine. Pediatrics. 2009

Reduction in acute gastroenteritis hospitalizations among US children after introduction of rotavirus vaccine: analysis of hospital discharge data from 18 US states. J Infect Dis. 2010

Rotavirus vaccine and health care utilization for diarrhea in U.S. children. N Engl J Med. 2011

New Vaccine Surveillance Network. Direct and indirect effects of rotavirus vaccination upon childhood hospitalizations in 3 US Counties, 2006–2009. Clin Infect Dis. 2011

II. The review overstates the case for vaccine harm surveillance

The review goes to great lengths in order to philosophically justify eternal surveillance of vaccine safety :

However it fails to justify these claims, and furthermore, is ultimately inconsistent in its reasoning.

1. The review’s root claims regarding vaccine harm surveillance are isolated demands for rigor

Throughout the review, the root claim regarding vaccine surveillance is “The most we can say is that we don’t have evidence that a vaccine causes significant harm, therefore, no amount of evidence can prove a vaccine is safe.” This is an isolated demand for rigor. No scientific claim could ever meet this standard, and yet, we allow other scientific findings to stand and we allow science to proceed. Vaccine safety, despite its necessary high standards, is not exempt from basic scientific reasoning.

2. The claim that vaccines may cause yet-unrecognized harms must be responsive to evidence

Strength of claim is delimited by strength of evidence. There is an abundant lack of evidence that vaccines cause significant harm – neither large-scale epidemiologic studies nor explorations of indirect pathogenesis has yielded any evidence thereof. From the standpoint of signal detection, the effects local to vaccinations (in temporal, spatial, and pathophysiologic senses) have been very thoroughly investigated already. If vaccinations cause harm, there will be a much greater distance from any instance of vaccination and the effect, and the detection of that signal would be subject to a prohibitive degree of statistical control and alternative pathophysiologic hypotheses. Therefore, detection of a significant harm signal attributable to vaccinations is unlikely ever to occur.

This means that the strength of evidence in favor of vaccine harms is, and likely will remain, extremely weak. Therefore, the claim that vaccines may be harmful is weakened. It is indeed irrational for this claim to remain unweakened by evidence.

3. Vaccine adverse events are unlikely to ever clear the clinical significance threshold even if a signal is detectable

Low-intensity signals should be met with low-intensity responses. The more evidence and surveillance required to detect an adverse effect of a vaccine, the smaller its effect size must be, either in terms of its frequency, its morbidity, or both. As such, the longer it takes to discover these effects, the more they will be outweighed by the benefits that the vaccine confers. At some point, there will be no events of clinical significance left to discover.

4. In light of 1-3, advocating for persistently high levels of vaccine surveillance is essentially petitio principii.

To advocate for continued intense vaccine surveillance (in order to justify vaccine refusal) is to posit three things : that vaccines can never be adequately proven safe, that gathered evidence of vaccine safety need not delimit our ongoing concern for vaccine harms, and that the intensity or clinical significance of a vaccine harm signal need not delimit our response to that signal.

This is essentially begging the question – assuming that one day vaccination will be linked to some harm, and that this harm will justify halting vaccinations.

5. The authors implicitly endorse point 4 when they mention their agreement that vaccines do not cause autism. The line of reasoning the authors use to justify claims of ongoing intense scrutiny of vaccine safety is practically identical to the line of reasoning used to justify claims that vaccinations cause autism.

I didn’t follow the line of reasoning that “things which cause a permanent effect must be subjected to more scrutiny.” Painting my front door blue is a permanent effect. Should the government form a subcommittee to scrutinize whether I can do that? Clearly not.

It would be more reasonable to say that things which look risky should be subjected to more scrutiny. So do vaccines look risky or not? I think both of the authors would agree that they don’t look risky, based on the evidence presented here. On the other hand, letting kids go unvaccinated is known to be risky. It only takes one traveller or visit from a relative to get your unvaccinated kid sick, possibly fatally.

So, to me the conclusion comes out of left field here. Sure, drinking a 24-pack of beer and driving 100 MPH on the highway is known to be dangerous. But what about the risks of NOT doing that? I mean… we can’t find any, but maybe they exist!

Consider the decision to make visible marks on your body. The decision to get a permanent tattoo must be subjected to greater scrutiny than the decision to get a temporary tattoo.

Permanent tattoos involve greater risk: the risk that you won’t like the tattoo in the future. On the other hand, painting my door is not risky, even if the paint is permanent. So again it comes down to risk, not permanency.

Pontifex. I am not saying that we pay attention to permanency instead of risk. Of course risk is the dominant feature of the decision.

I am saying that permanency effectively magnifies risk. We have to be more careful with decisions whose effects can not be undone.

On the point of how well do we actually understand all the harms, your rotovirus stats cited are from 2013? If you look at the current CDC stats, they estimate the risk of intussusception from rotavirus vaccination “to range from about 1 in 20,000 to 1 in 100,000”, which, if I did the math right, is 2-7 times riskier than what your citation claimed.

The biggest problems I see with mandatory vaccination are:

1. There are some vaccines which do have a proven higher risk than reward. Those also tend to change over time as the disease dies out and/or the vaccine becomes less risky/more effective. Based on the current recommendations, I’m not confident in the ability of the political/bureaucratic process of making the best decision on that for everyone else, above my ability to make it for myself.

2. Absent overwhelming evidence the only way to prevent harm to others is to override individual choice, people making their own decisions for themselves is the best system

The paper I cited used a risk of vaccination related intussusception of 1:50,000.

Well done,

The conclusion seems premature. Just because Germany, Ireland, and England can achieve herd immunity does not mean America can. Perhaps what allows them to achieve herd immunity is transferable to America such as bgulino’s suggestion but perhaps it is just the general conformity and deference to authority that Europeans have culturally more than Americans do. The experience with California they mention would seem to undermine the idea that recommended the vaccinations is enough to achieve safety.

Thanks. I felt that the Disneyland example was directed at those who wish to change from mandatory to voluntary vaccinations. What would happen in the real world in, say, Arizona if there were a high-profile outbreak tomorrow? Likely legislators would say, “We need herd immunity, and our neighbors in California got it by using mandates. If it worked for California, it will work here!” So the emergency fix is going to be mandates.

The message to those who oppose mandates is clear: if you want to continue to have vaccination be voluntary, you have to do the work to make that happen. That means crafting solutions that actually boost vaccination rates, and improve protection of vulnerable populations, to prevent the next outbreak. You can make it happen without mandates, but if you wait and hope declining vaccination rates will signal a “wave of popular dissent against vaccination policy” you’ll be doubly disappointed when that wave switches direction because of an outbreak. Because once the outbreak happens, you’re likely to see popular support for mandates.

How much do we know about the Disneyland outbreak? Specifically, do we know anything about Patient Zero?

Disneyland is a major tourist destination. The original source, and the majority of those who contracted later, could easily have been from out of state – or even from foreign countries.

If you’re going to place the blame for a disease outbreak at the feet of the legislature of California, Disneyland seems like the least plausible place for such a thing to occur.

In a herd immunity model, why would it be relevant whether patient zero was foreign? The point of vaccinating Californians is that when someone sick comes in, their disease can’t spread. If the measles outbreak was confined to Disneyland itself, fine. If it got out into Los Angeles, then it’s fair to assign blame to the legislature of California.

The legislature of California is responsible to the citizens of California. To the extent there is a major tourist attraction capable of drawing in disease from outside of California, it’s reasonable for the people of California to become concerned that what has been brought from outside California does not spread to the citizens of California. This would be a legitimate concern, whether the outbreak stayed confined to the Disneyland campus or not.

Hypothetically, if the outbreak was exclusively contracted by non-California residents, there would be nothing the legislature of California could do to prevent such a thing.

So the question of interest is, what proportion of those infected were California residents vs not?

The way it was handled in the news was something like, “Outbreak in Disneyland; Experts warn of low vaccination rates in California”. So from a purely academic point of view, you’d be interested to know if some group of Djbouti tourists – none of whom had been vaccinated – all contracted measles and caused an outbreak.

From a practical perspective, if there are a bunch of people spreading measles in my community, I’m going to be interested in preventing that spread to my home and family, no matter where they’re from. If I live in Manhattan and there’s an outbreak of zombieism in Times Square, I don’t really care whether the zombies came from out of state. I’m still concerned they’ll make their way to my home no matter how they got there. That doesn’t mean there’s anything NYC can do to prevent zombies from getting to Times Square. But practical considerations have never been a bar to calls for legislative action.

No one considered how inconvenient it is to administer vaccines for parents. In California, you are issued a yellow postcard which is manually filled out by the doctor’s office administering the vaccine. The parent is responsible for keeping the postcard and showing the card history to the school every year. Lose the card and you have to reconstruct the child’s history which may be difficult if you went to several different doctors. Oddly labor intensive and inconvenient considering all schools and all doctors offices in California have internet access. Also, typically a parent has to miss at least a half a day’s work, and the child must miss the same half day each time a vaccine gets administered. The system seems to be set up to cause maximum inconvenience for parents with minimum inconvenience for Doctors and Schools. Compliance rates would improve if a nurse showed up at the school and vaccinated everybody. Something similar to this is done in other countries and was done here in my childhood.

Compliance rates would improve if a nurse showed up at the school and vaccinated everybody. Something similar to this is done in other countries and was done here in my childhood.

I’m surprised to hear they don’t do that in America as that’s how it’s done in Ireland and, as you say, it has everyone in the class getting the same vaccine at the same time (unless kids are absent that day or the parents refused consent) so it doesn’t need one parent to take time off work and take the kid out of school to go to the doctor for the routine vaccination. And because everyone is getting it at the same time, I think that probably has a certain pressure (mild and unacknowledged) on parents to let their kids be vaccinated; someone who’s a convinced anti-vaxxer or who doesn’t want their child to get this particular vaccine will be sure to refuse permission on the consent form, but the ordinary parent who might otherwise not bother (because they forgot, it’s inconvenient to take a day off that day to bring the kid in, that day they’re all going to visit Granny on her birthday or whatever) just has to sign the form and forget about it.

“Line up and let this government employee inject your children with things” is not something that would go over very well in a whole lot of American communities (and not just rural white ones… a whole lot of minorities are very sensitive to this sort of thing as well, and with good reason).

Parents trust their own family doctors significantly more than they trust the government. Having the injections happen at school would probably increase opt-outs significantly.

The nurse is not a government employee. (In Ireland, she might be, to the extent that health care providers are necessarily employed by the government, but that is not the case in the US.) The system being proposed is that a wholesome family doctor who you already know and trust (or their designated assistant) shows up at school to provide vaccinations more efficiently.

There are maybe one or two hundred students per grade level in a typical American elementary school — their parents aren’t all going to know the same doctors. Still, recruiting a local GP or nurse is probably a better idea than trucking in some random CDC employee from the next state over.

(They’ll probably still be a government employee in that somebody’s going to have to pay them to do this and that somebody is going to be the government, though.)

RANT WARNING. This is a tangent unrelated to vaccinations or this article.

Yeah. The vaccinations I got as an infant are recorded on yellow cardboard too, and so are all the medical records written by my childrens’ ophtalmologist-optometrist. That seemed like a sane decision back in 1985, but we should eradicate that tradition as fast as we can. Ever since black-and-white photocopying got so cheap, those hard to copy yellow papers are causing a lot of difficulties to everyone. My mother and I spent probably a day combined to get a readable photocopy of those ophtalmology records, so we can present them to my adult ophtalmologist while the childrens’ ophtalmologist can get the originals back, since they were handwritten in only one copy.

There should be a principle that all important documents shall be written on white paper. If possible, we should also push for black ink rather than blue in pens and stamps. I’d like to go even further, by banning the use of thermal printers and laser printers for such documents, since the documents printed by those are often unreadable after a few months, but using more long-lasting forms of printing would cost a lot of money. Recipes on thermal paper often have a label on their back that the document is guaranteed to be readable for 8 years if stored between 18°C and 23°C temperature and between 42% and 58% air humidity. Needless to say, private individuals cannot store their documents under such circumstances, and even in libraries and museums, maintaining such conditions to protect old documents have a high cost. Ever since the local public transport company started printing all their tickets and passes with these fancy new laser printers a few years ago, I can’t figure out a way to make sure that my bus pass is still more than barely readable at the end of its three month period of validity, since I must carry the original with me every day.

I’m probably voting for this submission because it has been the most informative

A question re. the common argument about herd immunity: the idea is that vaccination for those who can do it will function as a protection for those who can’t. But the very fact that there exist people whose systems can’t handle vaccination implies that there is at least some burden on the system involved. This, then, begins to sound like a demand that the healthy “take one for the team,” so to speak, because their immunity will protect the less healthy. But I’m not comfortable with that (this is not an argument against vaccination, but an argument against making them mandatory, assuming I’m correct that some level of risk/physiological burden is involved).

Except that vaccination actually benefits the person getting vaccinated (assuming protective antibodies are produced as a result, which is not 100%). So those who get vaccinated are highly likely (it differs based on the vaccine) to become immune to getting sick themselves, thus it’s a concrete benefit to the one who gets the intervention, with a spill-over benefit to society.

This would be like if I told you I would roll a 20-sided dice, and if it came up as anything other than 17 I would pay you $100, and everyone else would get $1. (For 17, nobody gets anything, but we continue around the circle rolling dice based on the same rule.) That’s not asking you to assume a burden at all. You would be missing out on a clear benefit if you chose not to participate in the bargain, but so long as you’re part of the circle, you still get the payout.

Well, yes, obviously there is benefit to the individual. But the case for mandatory vaccination tends to imply, if not explicitly state, that there is zero (physical) cost for the individual to weight against the expected benefit. But if that’s not actually the case, then forcing a choice on people arguably becomes more problematic, even if the cost-benefit ration is very favorable, objectively speaking.

I guess it is similar to the question of mandatory schooling, both because it is imagined to be mostly all benefit for the individual and society and because the “free choice” aspect is complicated by those involved being children.

Good point. At the very least, not getting vaccinated means you don’t have to get poked by a needle. Sure, it’s a momentary pain, but it’s a huge factor in people not wanting to do things like give blood, so it’s maybe non-negligible for some.

As to the assumption that vaccination produces some internal, non-negligible stress to the immune system I don’t think that’s really a concern for most people. The thing to remember is that your immune system is constantly fighting off hundreds (at least) of different types of threats right now, as you’re reading this. One additional faux threat is just another day at the office for your T-cells. People think, “but won’t that make me weaker while my body is attacking the vaccine?” except that there’s a reason we give combination vaccinations. Any living organism incapable of robustly fighting off multiple attacks at once was long-ago selected out of the population.

Right, but if something clearly and uncontroversially benefits the individual – there would be no need to make it mandatory.

I think onyomi’s point is that any argument for mandatory vaccination contingent upon the fact that it will establish herd immunity and thereby benefit those who cannot be vaccinated is, very much, a “take one for the team” sort of argument of the style that demands sacrifice from Group X to benefit Group Y.

My skepticism of mandatory vaccination has always relied upon a similar argument. Something like “If you’re so confident these vaccines work, what do you care if the neighbor kid isn’t vaccinated? Your child will get the vaccine and be protected, right?”

All things are unclear or controversial if you ask enough people and if opposition to those things happens to have become a meme.

If my kid has childhood leukemia, or had to receive an organ transplant, or is on certain medications for their chronic RA or psoriasis, vaccination may not be an option for them.

The benefits to vaccination are sufficient that my children (who don’t have any of the above problems) received all of their vaccinations. The cool thing about herd immunity is that is protects the sick, elderly, or otherwise immuno-compromised in addition to those who receive the vaccine itself.

You’re arguing that this is like if a rich guy invests a bunch of research to find a cure for some disease, and suddenly he doesn’t have to worry about it anymore. But you don’t have to worry about it either, even though you didn’t pony up any money for it. You’re arguing that it’s a positive externality generated by an action that is personally beneficial but has some concrete costs. I’m just asking, what costs?

In order to “take one for the team” there has to be something that’s actually being taken. A poke in the arm? Sure. I’ll take that.

You will, but many won’t.

My point is, the justification for mandatory vaccination depends on one of two unique arguments.

1. A paternalistic argument that individuals should be vaccinated “for their own good.”

2. A “needs of the many” argument that individuals owe a duty to the rest of society (in particular, those who cannot get vaccinated)

Now, it’s possible that both of those arguments are true and morally justified. But that doesn’t make it okay to simply combine them and equivocate them.

More specifically, a lot of people make Argument #2, and then when someone counters with “Gee, that sounds very authoritarian. We don’t generally go for that sort of thing in our society. It’s not cool to force someone to do something they don’t like because some other person might benefit from it,” the response is often “Well it’s for their own good anyway” (argument #1).

Make Argument 1 or Argument 2, but don’t make one, then try and switch to the other as soon as someone challenges you on it.

The type of bait-and-switch argument you outline is certainly employed. But I would like to point out that I haven’t done that here.

My point wasn’t, “It’s good for everyone; wait, you don’t like authoritarianism that sacrifices the good of one for the needs of the many? Well it’s good for the one, too, so make them do it anyway.” Honestly I haven’t maintained a mandate recommendation. I have maintained a “herd-immunity is good public policy however that is achieved” recommendation, while rejecting the claim that this is a trade-off system of the needs of the many/few variety.

I know this is a subtle distinction, but I’m actually responding to the claim above that, “if it helps everyone this implies it at least marginally burdens the individual”; and claiming that’s not supported by the evidence. I’m asking “what is the harm?” Besides a needle poke, or very rare, known, and often avoidable complications where is the harm to the individual?

The philosophical question of whether force should be employed to implement a medical intervention that benefits both the individual and society is a separate question. If we can achieve herd immunity without you having to get the vaccine, that’s great for you and I hope you don’t contract the disease when traveling abroad, or meeting with a large group of similarly non-vaccinating people. Meanwhile, I’m going to get it because I personally benefit from it.

I am not harmed by it.

That’s because central examples of authoritarian things harm one person for the sake of others. If the thing doesn’t harm the person, and in fact helps him instead, it’s a non-central example of authoritarianism and “authoritarianism bad” is implicitly about central examples.

I don’t know – but presumably there must be some, or the individuals wouldn’t resist it so vehemently.

You may counter with “These individuals are misinformed – they think there is harm, but they are mistaken” to which my response would be either

1. It has not been scientifically proven that all vaccines are clearly and obvious free from all harms

or

2. Authoritarian practices and behaviors, in general are considered harmful (in the US at least). The loss of liberty to make one’s own decisions is a harm, in and of itself. Freedom and liberty are positive virtues and being denied them is a harm, even if the end result is “only a needle poke.”

I would not counter with “they are misinformed”. Though that is true for some individuals, others are well-informed of the research that fails to detect any harm, despite really trying to find some. The reason, I believe, that some individuals opt out is not due to harm, but due to perceived risk.

1. It’s impossible to show something is absolutely safe. Everyone has to make judgement calls based on the safety of doing (or not doing) things every day. People who opt out of vaccination are – in my opinion – making a basal judgement that vaccination by its nature is suspect as harmful. I think there will always be people who reject just about any innovation, no matter how innocuous the evidence suggests it to be. (In the early days of printing, people used to be skeptical of reading – and not just because of political/religious revolutionary implications, but as a potentially risky activity in and of itself!) I suspect this may be a survival mechanism for the species such that we don’t accidentally wipe ourselves out in the event that the 1-in-a-million “but there could be some harm we just missed somehow” statement actually turns out to be true.

2. If all government intervention of any kind is “authoritarian” and must be avoided at all costs, you have to either become a non-agression principle anarcho-libertarian, or accept that outside that small group a certain degree of centralized control will always be warranted in civil society. Everyone’s threshold is different, though, and I suspect the poke in the arm (or more practically, the removal of the ability to make a medical decision on behalf of your child) is sufficient for a small percentage of people to pass the threshold of “too much authoritarian intervention for my taste.”

@sclmlw,

In regards to risk of harm, I assume you’re aware that all vaccines have a risk of mild, moderate or severe negative reactions among the general population. Even an organization as pro-vaccination as the CDC recognizes there is no vaccine which is “100% safe” for everyone who has ever been vaccinated for it and some vaccines have even been pulled because of the high number of adverse reactions after their use became widespread and initially recommended, so I’m not sure how your concept of “there is no risk” to rolling the dice with no downsides is an accurate analogy.

Let’s take the polio vaccine as an admittedly extreme example. Not only are there currently many more negative reactions to the vaccine each year than there are cases of polio contracted in the U.S., but there were 3x as many cases of vaccination causing polio paralysis in the world last year than new cases of regular polio. The caveat is that the numbers of all of those are tiny, but it’s a persistent trend, not a one-year thing, the point being that what makes sense (inoculate everyone against X!) one day may make less sense another day.

Another bad risk ratio is probably your mentioned rotovirus vaccine, with somewhere around 1 in 20K to 1 in 100K at risk for Intussusception vs. something like a 1 in 6M risk of death from rotovirus in the U.S., most of those victims with population characteristics which don’t generally get vaccinations anyway.