This is the bi-weekly visible open thread (there are also hidden open threads twice a week you can reach through the Open Thread tab on the top of the page). Post about anything you want, ask random questions, whatever. You can also talk at the SSC subreddit or the SSC Discord server. Also:

1. Some other people have been doing their own analyses of the survey results. See this post on top blog recommendations, this one on politics, personality, and religion, and these collected findings. I don’t necessarily endorse all of these analyses and there’s some good pushback and additions in the comments.

2. Comment of the week is the really good (and really long) debate between algorithmic bias researcher Ilya Shpitser and algorithmic bias article writer Chris Stucchio. It starts here and continues for several hundred comments – go down to here if you want to start at the point where it gets interesting. Can I convince Ilya and Chris to do an adversarial collaboration explaining what everyone agrees on in this area and what’s still controversial? If not, does anyone else who’s at least kind of an expert on this want to do it? Also a fun comment – this comment on how Karl Marx believed a weird pseudoscientific theory linking national character to soil quality.

3. I wrote an article for the new Less Wrong site – A Less Wrong Crypto Autopsy.

4. GiveWell wants you to know that they’re hiring for some open positions. They do very well-respected effective altruism work. Some positions are based in the San Francisco Bay Area, others are more open to people doing them remotely.

I’ve been reading this blog for years now. At the beginning I distinctly remember thinking of Scott as a genius, I rated him higher than EY, it was common to visit here once a week and being presented with new insights that’d leave me thinking for hours.

I first noticed a downturn a few years ago. Articles weren’t as insightful as before, it was easier to spot mistakes or slips on the arguments, strawman arguments were being made at least once every two weeks or so, but despite all this quality was still higher than on (by then, already defunct) LW, and I wasn’t aware of any 3rd site that was better than either, so I kept coming back, albeit at decreasing frequencies.

Commenters were always worse, though. Although article quality was, in general, higher here than on LW, commenters here have always been worse than there. I’ve always wondered whether they aren’t dragging Scott’s waterline down, somehow.

Over time I’ve developed an habit to stop and think about what I’m doing and in those instances I’ve frequently wondered: where am I wasting my time on? Have my actions so far been conducive to what I was actually expecting to achieve? I’ve insisted on remaining at this site (and on LesserWrong, after it debuted, and on others of a similar tint) despite lowering quality because those were the only communities with an explicit interest in both epistemic and instrumental rationality. Despite this, it has been obvious for a while that neither have helped me achieve my objectives as much as other activities I spend my time with, and so they aren’t much more than “entertainment”, things I read thinking about the improvements I’m making, but without actually improving by an amount that would be expected given the amount of time I spend here.

But that “entertainment”, when it no longer gives you important (or even interesting) insights, when you start noticing reasoning mistakes on nealy every post, when you see them taking actions that you think are harmful to society at large (and, including, to that small comunity itself), when neutral and impartial analyses are left behind and strawman articles are posted and commenters regard it as some form of “charitability”, “impartiality”, “impecable logical analysis”. It just isn’t entertaining anymore.

If content is no longer entertaining, nor instrumentally helpful, nor epistemically accurate, then I receive no benefits coming here on a frequent basis. It just seems that the values held in high regard by the community aren’t the values they have actually maximized for. I’ve already cut some links with the rationalist community at large before and this was the last bastion holding me in place. So, this is my goodbye post. I’ll return every 6 months or so in order to check for any progress but, honestly, I’m not expecting to see much. See you in June.

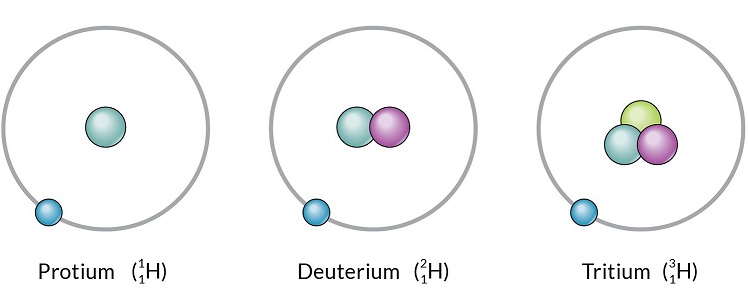

You know, if you look cross-eyed at the picture in this post, you can see vaguely 3D models of Hydrogen-2 and Hydrogen-4.

I knew a guy who somehow could trick his brain to see a pair of stereoscopic images in 3D without using a stereoscope. He was a programmer and what he did was duplicate his window in Atom or whatever so it was tiled vertically: one on the left, one on the right, full-screen. Then he’d get his head a certain distance from the monitor and could program in 3D.

I was never able to replicate that trick myself.

Suppose you had a group of intelligent people with a variety of views and motivations on a complex, contraversial topic/question, and you wanted that group to research, discuss and produce the most truthful account/answer of that topic/question. Assuming you had control over how the group would function, could determine the principles and rules that governed the group, but could not control the account/answer itself, what would you do? What principles/rules would you make? How would the group be organized? What roles would there be? By what medium and in what way would people interact? Would you limit the size of the group?

In Dream Makers Frank Herbert wanted small packs tearing into different parts of the problem.

I’d like to remind everyone that some SSC members are playing Diplomacy on Backstabbr.

There seems to be a coordination problem, how fitting.

Game 2 has 5/7 Players. Someone please join.

http://www.backstabbr.com/game/5767909670912000/invite/F3IYT1

Game 1 has 6/7 Players. There was a full 7 the first version, but team Cicero has not rejoined and no one wants to take the spot claimed by someone else.

http://www.backstabbr.com/game/5732216907235328/invite/14343D

To get a game going, I intend to claim Cicero’s spot if vacant for one more day and am open to team members. Reply with contact information.

What is the current least-sucky dating site?

I find myself semi-on-the-market, have never bothered using one, and don’t know where to start. I’m poly, do not intend to marry or have kids, but don’t have much interest in purely casual sex either. I have one girlfriend, but we don’t expect it to be permanent. I am Grey Tribe.

The only sites I know anything about are Tindr (which I gather will not suit, given the lack of interest in casual sex) and OkCupid (which I’ve heard has gone downhill in recent years).

Not in the market myself, but many male friends who are or were recently- Tinder gets used a lot for more than just the casual sex market. Several guys I know are with long-term girlfriends they met on Tinder.

Varies by region, as I understand it, because whatever dating site is the schelling point in an area has the massive advantage of actually being the dating site where people are.

Off the top of my head, there’s “Bumble” and “It’sjustlunch” and a search for speed dating will get you somewhere in a lot of locations, and there’s the crypto-currency one that just launched that got its own full post by SSC, and there’s ChristianMingle and eHarmony (both paid) and there’s the craigslist personals and… also there’s the sugardaddy / affair sites, which if you are poly might or might not aim at what you’re interested in, and now you’ve got the search terms you need to get started, maybe.

from experience, OKcupid has dropped off a little since allowing paid promotions and some other things, the last I really used it even to explore was a year ago–was still pretty close to its peak then, from what I could tell as someone who’d used it since 2010 or so.

Recently, we talked about the Efficient Market Hypothesis, specifically about investing to try to beat market returns. I believe this was part of the discussion about Eliezer’s new book re: expert consensus.

Providing some feed-back from the ground, based on conversations with my “hard-nosed” accounting co-workers.

1. It looks like everyone who invested in Bitcoin at the peak lost money. While everyone was talking about it non-stop when it was at its peak, there’s a sullen feeling of regret lingering in the air now. They were watching the price every day, multiple times a day: now they barely mention it.

2. Among my group of young financial professionals, males under the age of 40, I’d estimate investments in crypto-currency to be somewhere between 50 and 75 percent. Average investments are small (like $500) but some guys have some pretty large stakes ($10,000+).

3. Listening to these guys talk about stocks is hilarious. They talk constantly about investing for the “long haul” and only in stocks they “understand.” This is apparently supposed to convince themselves of their seriousness and Warren Buffet-like inquisitiveness. Nonetheless…

4. Several of these guys are investing in the company stock, but not purchasing it through the company (which offers a 10% discount). They do not like the 1-year vesting period. Apparently, while they want to invest for the long-term, they do not want to invest if they are required to hold the stock for long-term. This baffles me.

5. They continue to think our stock is under-valued. This baffles me more, as our revenues are clearly declining. They do not have access to any material non-public information (it’d be illegal to trade on that!), but they should at least be close enough to the numbers to know that we aren’t doing so hot.

6. If they were actually paying attention to the sector as a whole, they’d see that our biggest competitor, who is also the biggest player in our industry, is priced at a good 25-30% lower than us. Our biggest competitor has better growth, a better portfolio, and a higher dividend yield. This does not give them any pause, and they think our stock will continue to go even higher (even though it looks over-priced compared to industry standards).

7. I sometimes discuss stocks with them. I do not actively invest, but it’s fun to talk stocks sometimes. Many do not know what a P/E ratio is, or why a P/E ratio is relevant.

8. They invent their own explanations for anything. When discussing the Green Mountain/Dr. Pepper merger, they automatically assumed Green Mountain is in Vermont for “tax reasons.” This was asserted without any evidence.

9. They buy into narratives EXTREMELY easily. This is disturbing me. Hold on, let me emphasize: this is really, really, really disturbing to me. These are all numbers guys, and while they are fairly low-ranking, they are entrusted with a fair degree of financial information. However, they will buy into whatever nice-sounding narrative they hear from a company CEO. For instance, if Apple spins a narrative about how Iphone X is going to have great sales because they are going to be able to sell it to underwater welders, they will buy it hook, line, and sinker. They will not ask any questions about the crush depth of an Iphone X, or whether the market for underwater welders is large enough to affect Apple’s gross revenue of $230 billion.

10. These guys treat Seeking Alpha as if it were gospel. I have literally heard several times “I have no idea what this stock is, but they said it was a Buy.” How this reconciles with #3 above, I have no idea. I do not think Warren Buffet would say “I don’t even know what this company does, but someone said to buy it, so I put $1 billion into it!”

11. Most of these guys are swimming naked. They have practically nothing in their checking accounts. I imagine if a recession hits and they lose their jobs, they will have to liquidate their stock holdings at an unfavorable price in order to keep from being bankrupt.

Overall, I think I am looking at a bunch of guys who have simply never lived through a recession and don’t know how precarious their investment positions actually are in the short-run. I suspect they are in for a RUDE awakening the next time the bubble bursts and a recession hits.

What sort of experience do the rest of you have with friends and colleagues investing in the market?

The strong efficient markets hypothesis is obviously horseshit if you spend any amount of time watching price action on a speculative asset. But the weak efficient markets hypothesis has some teeth to it: it allows assets to behave irrationally as long as they’re not so irrational that it’s possible to make stupid money without getting correspondingly stupid lucky or investing a stupid amount of time. A weakly efficient market doesn’t have to be all-knowing, it just has to be smarter than the average bear (who, as you’ve implied, is very, very dumb) and loosely correlated with reality in the long run.

No, it has to be smarter than the weighted average bear, based on how financial resources are distributed.

How can someone work in accounting and not know what the P/E ratio is?

Good Q. We don’t typically deal with those kinds of valuations. However, all of us took business classes in college, so all of us SHOULD know what a P/E is. We might not remember something like the Quick Ratio, but P/E is one of the obvious ones.

Especially if you fancy yourself a junior Warren Buffet.

Random questions (I don’t know much about finance):

– “I’d estimate investments in crypto-currency to be somewhere between 50 and 75 percent”. What does this mean? Percent of what?

– “They continue to think our stock is under-valued. This baffles me more, as our revenues are clearly declining. They do not have access to any material non-public information (it’d be illegal to trade on that!), but they should at least be close enough to the numbers to know that we aren’t doing so hot.” How is ‘how well the company’s doing’ not material non-public information? Or does everyone know the company is doing badly?

– Playing devil’s advocate: assuming Seeking Alpha is run by some well-respected finance expert, is this such a bad idea? Isn’t it like saying “I don’t know anything about cancer, but my doctor recommends chemotherapy, so I’ll do that one”?

All public companies make quarterly reports on their revenue, among other things. It’s likely people in the accounting department work on these reports directly or indirectly. So while anyone (the public) could know this information, these guys definitely should.

Your doctor is at least supposed to have a professional ethical duty to you. He is supposed to only make recommendations that are a) in your interest and b) that he is competent to make. The guys that write at seeking alpha pretty much exhaust their legal responsibilities by disclosing whether or not they own a stock and have no professional ethical responsibilities to the reader to begin with.

-Crypto-currency investment: I mean something like 50-75% of the guys have SOME stake in a crypto-currency. No one has anything like 50% of their assets in Bitcoin, but the typical guy in my group has SOMETHING in there. They actually try to peer pressure me into investing, which is really odd.

-Re material information: What Brad said is accurate, publicly traded companies have a lot of reporting requirements. We all have some idea of the day-to-day operations, but we really don’t know what the full quarter numbers are going to be until they are released to the public. Plus, companies typically issue guidance: they will say they plan to make $100 billion in revenue next year, of which $5 billion will be profit, or whatever. We won’t have any idea if we can hit those numbers, but we should have a vague gut feeling of whether business is good or bad.

That’s why I say nothing is material. I could say that Account X is not doing so hot and we gave steep discounts this year, which is really bad and would get me fired. But it’s also a really small portion of the portfolio, and I don’t have access to the full metrics of the account anyways, so it’s not material: disclosing that information by itself would not affect any investor’s decision. (And if it would, I need to get paid a lot more).

But when we see the whole company numbers and compare to what we know about the accounts, we should be able to form a good idea of what’s actually happening. And we’re really close to the accounts, so we shouldn’t be deluded like the typical investor MIGHT be.

These guys seem to be buying into the bullshit. It’s not like we are going to go bankrupt or anything, but I’m expecting some belt-tightening, and these guys are expecting us to soar. Our stock price declined 35% this year, so…you know…I’d say I’m closer to right than the guys who bought while our stock was at an all-time high.

-I would normally agree with you on the devil’s advocate piece. I’ll leave aside the rational arguments and argue as if you were one of these guys. You remember the Daily Show, right? Do you remember Jon Stewart tearing into Jim Cramer? Jim Cramer is the guy with the infamous Bear Stearns call. Jim Cramer was an expert telling you to buy all sorts of stocks, but I believe if you followed his advice, you would have significantly underperformed a typical index fund.

From my rationalist perspective, I am generally a believer in the weak form of the EMH, so I can outsource my judgement to the market as a whole by investing in an index fund. It may not be perfect, but it does a pretty good job, and I have to do next to no thinking.

Why odd?

It’s negative to them if their investment doesn’t work out, because then you get to laugh at them, while they feel jealous. It’s negative to them if their investment does work out, because then you might very plausibly get jealous. If they succeed at pressuring you to invest, they increase the social stability of your relationship with the rest of the team.

You should see it as a compliment: they value you socially.

I def. see it as a compliment. It’s just weird because I don’t see a lot of peer pressure now that we are in our 30s. There’s some when it’s time for SHOTS SHOTS SHOTS (and occasionally someone fills an entire coffee mug of vodka). There’s a bit less when it comes to adhering to workplace norms.

But peer pressure over investment and savings decisions? I don’t really get it. The only equivalent I’ve seen are the young people telling me not to pay off student loan debt too fast and taking more time to travel (which is a flat NO! from me as well).

What’s the rationale for that? Some kind of tax deduction thing, or just not wanting to feel bad about it themselves?

Some people have a disgust reaction to debt and make what are probably sub-optimal decisions from a purely financial standpoint because of them. Particularly when it comes to very low interest debt — some student loan debt has a fixed interest rate as low as 3.4% with the possibility of a further 0.25% discount for on-time payment and certain repayment options that can cut the effective rate even further depending on income.

Inasmuch as those reactions are immutable or close to it, they are just another preference and purely financial optimization should probably take a back seat to preference optimization, but if they can be reasonably overcome by laying out the objective case, then I don’t see anything wrong with mild social push-back.

As one of the people you are talking about, this is what I was asking for.

I actually think my irrational disgust of debt is fairly rational given that humans are frequently overconfident and that the typical fail case for borrowing too much is worse than the fail case for borrowing too little. One must also consider his own consciousness level–how likely are you to have the occasional late fee eat up the savings of borrowing at a fixed interest just below inflation, etc.

Yup, if you have a low interest debt, it makes no sense to pay it off immediately. You could put that money to work better other places. For example, my car is financed at 0% interest. You can say I am an idiot for spending too much money on my car, but I am not going to pay it off early, because there is no benefit.

What financially makes sense varies from person to person. We have student loan debt that’s accruing 6.5% interest and another loan that’s adjustable-rate at the prime rate, so right now we are at 4.5%, and that will continue to climb as the Fed raises rates. So….I’m a bit more interested in paying that down than instagramming myself from the Chichen Itza, or whatever the youngsters do these days.

These guys want to travel, spend a lot of money, and then put their money into high-investment returns. Some probably have lower interest rate loans, too.

Brad basically explained it, but yeah, I’ve given a similar objective explanation to friends and colleagues- my wife and I both have (very low interest) student debt, and her’s is even deferred interest-free while she’s pursuing her master’s degree. So it’s a way better deal for me to kick extra cash into paying down my slightly-higher-rate mortgage, or possibly just to add more contributions into index funds, since the annual expected growth in the funds is bigger than the interest rate on the student loans. (Though you need to take taxes into account on both sides, so it’s not quite that simple a trade)

I think there’s an argument to be made that if you’re generally conservative with money, paying off “low-interest” debt can be a very good plan.

The general theory is “You shouldn’t pay off debt if you think you can make more with your investments.” But a conservative person probably isn’t investing in penny stocks or in bitcoins and counting on making a 20% annual return. My dad refuses to invest in anything riskier than a government bond. So yeah, he should probably pay down his 3% mortgage whenever he can.

If all you’re doing with your money is sticking it in a savings account that earns 0.5% interest per year, paying down debt is almost always a better option.

I definitely see paying the higher rates down with lower interest rate loans, assuming all else equal, sure. Pay the minimum on the student loan until you pay off your credit cards, compare the rates on the student loans to the rates on the car, etc.

Borrowing in order to invest (other than, say, starting a personal business), even if it all the details point in your favor, seems risky–if you lose your job and can’t easily withdraw from the investment it’ll end up costing you in fees. (And if you can liquidate it in emergencies, how are you getting such favorable rates?).

If you have non-essential assets to cover it, then that’s a different matter as well.

But while I’ll grant that there’s cases where having debt can work for you, I’m not sold on how common it is to be paying down a loan at such low interest rates compared with any safe investment. Maybe I’m letting a lot of money sit on the table though. It could well be that paying off student loans when the money could have been put into 401K or company stock offerings was a “safe” but foolish choice had I done the numbers. However, I used the hueristic that interest rates are going to be higher than most investment pay-offs (barring matching funds essentially doubling investments immediately, of course).

Heh, the 10 year treasury bond rate is 2.76%, so for me I don’t think there is ever a case that I should be investing in treasuries over paying down my mortgage.

On the other hand, a high-yield Muni fund from Vanguard has a 10 year return of 4.7%. Muni funds I think are tax free at the federal level? Not sure if that changed with the new tax bill. THAT might be a better option, because you don’t pay tax on the Muni, and don’t lose the tax deduction from paying down your mortgage…you just incur a higher default risk.

Dunno, though, not really an expert, and don’t currently have the need to be (paying down higher-interest student debt is more important). I collect money from dead-beats, I don’t do tax planning.

Randy,

I don’t think there’s anything wrong with your heuristic. It’s not necessarily value optimal and there’s a good chance you are leaving money on the table, but I wouldn’t care all that much. If you’re doing the right things, you’ll be able to provide for your family and build up a comfortable nest egg, as long as you don’t blow massive amounts of money on houses and cars and travel that you don’t need.

I’ve got similar heuristics to you, which is why I am planning on knocking out my mortgage as soon as I have some extra cash to do so. I figure we can be debt free in 10 years, which is going to feel pretty damn awesome.

One thing, though:

See, this is why I don’t think these guys are really serious about investing, because they only talk about stocks and crypto-currency and blah blah blah.

If you want to juice returns, you want to leverage up and use Other People’s Money (OPM).

A good way to do this is in Real Estate, which is my uncle-in-law, an actual professor in finance, plows his money into income-generating real estate.

I do know SOME guys that want to get into the real estate bandwagon, or have in a very limited fashion.

This is baffling to me- these are finance guys aged 30-40? My marketing colleagues aged 25-35 would laugh at their ignorance of basic investing, let alone how the programmers would feel.

To me, outside the finance industry, this would be like digital marketing guys not understanding the difference between bounce rate and exit rate, or why you need to actually test good ideas to see if they’re actually performant, or why when some random SAAS promises you 3000% growth it’s obviously bullshit.

1. Are you really sure the same people believe both 3 and 10? It’s very common that different people with different opinions hold contradictory views.

2. I am confused how you connect “under 40” to “never experienced recession”. If these guys are in their 30s, 2007-2009 should have been influential years for them. I am in my 20s and they were influential for me. It is possible they didn’t have stake in the market back then, but they should have some awareness of economic ups and downs.

If you are in a certain age range then the ‘market down’ was a crazy, weird event but it has been dwarfed in financial impact by ‘market up’ since then. If you lost 10s of thousands in the dip but kept buying/contributing then the upswing has far, far exceeded that. Even if you sold out and sat on the sideline for a couple of years it hasn’t been particularly bad and you might well have recovered and then some.

1. I am 100% confident that at least SOME people hold #3 and #10. They’ve express both sentiments to me. There’s (IIRC) at least 3 guys who have expressed this view.

There is one guy I know who I suspect does NOT hold to #3, but he has never clearly articulated otherwise. He describes his investments as “I’m already paying into a 401k and I have a little extra, so I am going to play around with it.” That’s obviously not #3.

Most guys I’d describe as “unknown” about their exact level of contradiction here. Keep in mind, I’m not running survey data, only reporting our casual conversations.

2. They lived through the recession, largely at the beginning of their careers before they had sizable investment holdings. I think there’s a big difference between living through a recession as a worker and really experiencing it as a capitalist. My Mom never invested much in stocks until the late 90s and FREAKED OUT when the Dot-Com Bubble hit, and that was a pretty mild recession.

Most probably still had a safety net from their parents as well. I know I did, and the guys I know from back then did as well. It’s a big difference between riding out a recession on your parent’s couch and trying to make a mortgage payment.

I don’t know your experiences. It’s just my rule of thumb that ascribing opinions to a every member of a group of people can easily be wrong.

It seems to me that losing a job and needing to move back in with your parents is a much more traumatic event than seeing the stock market fall. One directly changes your entire living situation and the other is merely psychological discomfort of seeing some numbers go down, assuming the investments are not a source of living expenses.

If one has based their hopes for a good/better future on those numbers going up at a certain rate & instead they rapidly go down, that can be quite traumatic.

My fears about UFAI are more about conflict issues than mistake issues. It’s conceivable that someone will come up with a paper clipper by accident, but I’m much more worried about a corporation or a government or possibly a religion trying to use AI to achieve dominance.

or possibly a religion trying to use AI to achieve dominance.

So it’s called the Butlerian Jihad for a reason?

+1, for at least two reasons:

a. An AI in a box at a university lab starts out powerless but may be able to get power over time by convincing people to let it out of the box, offering people things they want, etc. An AI supporting an investment bank or intelligence agency in its mission *starts out* in a position of great power and influence. Instead of manipulating/bribing/threatening college students or researchers to do its bidding, it starts out manipulating people with serious power and with congressmen on speed-dial. The CIA’s AI or Citibank’s AI also starts out with access to valuable information flows and can probably get more, and can probably much more quickly get resources for improving its computing power; the university AI in a box has to do a lot more steps to get those things. Almost any path to having a big impact on the world for a research-project AI is shorter for an AI of a powerful institution.

b. Even if the AI never develops its own goals or has mis-specified goals lead it to turn its creator into paperclips, if the CIA or Citibank end up with the first general superhuman AI, and it gets ahead of the rest of the world on the exponential improving capabilities curve, we end up with the CIA or Citibank owning the world, or perhaps with their AI owning the world while to the outside world, it looks like CIA or Citibank are in charge.

c. If the world awakens to the risk of this AI in time to stop it, the research lab AI starts with *enormously* fewer resources with which to defend itself. The CIA/Citibank one starts out with connections and institutional power and even some muscle, right away.

Are you asking for arguments why this is a smaller problem? Is there a chance for you to change your mind?

I think it’s possible people will start out by trying to win a conflict, but they will end up admitting they made a mistake (ie even by the “winner’s” values it was a mistake)

Possibly related

Unrelated to anything:

I’ve been going through some of the music I listened to when I was younger. Paid no attention to lyrics at the time, but one song in particular caught my attention lately. “Explode” by The Cardigans.

Insert epithet here, after I realized what it was, and sort of by association, what the band name probably refers to (something warm and comforting). Most of their music, on re-examination, seems to be running along the theme of “Attempting to provide emotional support for teenagers who don’t receive any/enough”.

Assuming I am correct on their purpose, I find it quite an interesting project. The only other band with a sort-of similar purpose I can think of might be The Verve Pipe (the US band, not the UK band by the same name), but their target audience seems to be somewhat older, as they seem to aim at the college crowd.

Which leaves me wondering what else I haven’t noticed about music, which I mostly listen to for novelty (I tend to like music that does interesting things I haven’t encountered before)

…

Similar thought: Piano pieces were often designed to capture specific experiences/emotions; appreciation of them was a specific kind of class symbol in that you could judge what kind of person someone was by what pieces they could relate to / appreciate.

At least, that is my guess, after listening to Chopin and reflecting on secondhand depictions of the culture around piano pieces, trying to fill in the gaps the observers were missing.

Oddly enough, you can also reach this conclusion regarding the Insane Clown Posse!

Never listened to them, TBH. I’ve always sort of patterned matched them as punkish nu metal, which had no appeal at all.

Actually, the English band is just The Verve.

So it is!

I misremembered The Verve’s naming issues as being in conflict with The Verve Pipe, when it was with a record label.

(I still don’t know what “verve” means and have no intention of finding out.)

It’s a bit like “vim” 😛

I’ve never listened to The Cardigans, but your description validates the judgment I made based on their name. I will continue to not listen to them.

I was a huge Nirvana fan from about ages 12-16. I used to think their lyrics were deep because they didn’t make obvious sense, as if Cobain was so smart and guru-like he was hiding meaning behind multiple layers of cryptic symbolism or something (symbolism I of course uniquely understood). Then I stopped listening to much Nirvana between about ages 17-24 and when I came back to them later I realized most of their lyrics were just deliberate nonsense. Because Cobain was less of a “tortured artist” than a goofy guy who thought that kind of thing was funny.

Yeah, their name pretty much sums up their sound, now that I think about it.

It is interesting music, mind. But the vocal style is annoying to a lot of people.

You might like Mechanical Poet. Maybe.

As I was reading your description of The Cardigans and grimacing, I thought about what I think good rock music should be: loud, aggressive, dangerous. Not monotonously uniformly so, but that should be the default. But also with an intelligence and mysteriousness (unlike what another loud, aggressive, dangerous style of music — rap — ought to have).

That’s why I like bands like Helmet and Soundgarden.

Hm. Mechanical Poet is more sinister than aggressive.

Kontrust, maybe. “Just Propaganda” is a decent song.

ETA:

I wouldn’t mind rap so much if someone would just take away all their goddamned high hats. By the way, you are welcome; if you hadn’t heard it before you will now.

High hats? You mean like, the piece of a drum set comprised of two cymbals? None of the rap I like has actual drum set sounds in it.

It’s a modern rap phenomenon. Certainly old-school rap didn’t pull that shit.

It is almost comical at this point. It misses comedy by a thin sliver of being annoying as shit.

Even though I’m old enough to have been a fan of Nirvana during those ages, I wasn’t. I came to it later. I never thought their lyrics were deep. But I don’t expect or even want deep lyrics from my music. I like English language lyrics mostly because I can sing along, whereas I can’t hum very well.

Deep is probably the wrong word. It’s a terribly abused word, to the point where if you say something is deep that basically means it’s vapid and cliche, a truism at best, a trite delusion at worst. Maybe a better term would be “challenging and beautiful.”

Well anyway, 13-year-old me though Nirvana’s lyrics were challenging and beautiful. 23 year-old me thought they were mostly silly, sometimes clever. The surrealist influence of the Meat Puppets was more obvious to me then, too, since by then I’d become way more familiar with their (the Meat Puppets’) catalog. Later I realized there was some Melvins influence too, and Melvins lyrics aren’t even surreal, they’re plain unintelligible. (Though Buzz says they mean something, but only to him. I can dig it.)

I guess I come at it from a different angle. I can appreciate the artistry of a great poem, but I don’t much enjoy them. I think trying to set a great poem to music, would just make it that much harder to appreciate.

It’s just not what I’m looking for in my music.

I like to sing along to “In Bloom”, for maximum irony. Because I know not what it means.

Me too. Like to shoot my gun also.

I like Kurt Cobain’s lyrics much more now that I’m old enough to see through them. I have a big soft spot for meaningful-seeming nonsense.

I played around with some numbers for a fantasy setting to get a handle on civilization hierarchy. My assumptions:

A given unit of hierarchy can effectively service around six sub-units.

The smallest unit is around 30 people, and constitutes a farming region.

Each unit (gauging by Wikipedia information on civilization hierarchy, plus a guess that a single farmer can provide for around one extra person, and checking the math) typically supports about three times as many people as the unit beneath it; six farming communities supports a hamlet of around 90 people, which supports a small village of about 270 people, and so on and so forth.

Long story short, the number of hamlets you need to support a capital city of more than a hundred thousand people is staggering.

Which brought to mind the rural areas I group up in, which are filled with long-defunct hamlets (although this being the US, they didn’t call themselves that).

Which in turn leaves me somewhat slack-jawed at the level of social disruption of the past two centuries.

ETA: For reference, the maximum population of pre-industrial London appears to have been around 600,000

ETA again: Given the population of England at the time was around 5.5 million, this suggests my hierarchy estimates are off; 6 might be too low

Industrial/Agricultural revolution is a big deal. Not many people are needed to actually get calories out of the ground anymore.

That part I grokked. I didn’t grok all the intermediary organizational units that were rendered obsolete as well with modern transportation, or exactly how prolific they were.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gram_panchayat

There are still apparently 250,000 of these base-level administrative units – which appear to still be more of a large village than a hamlet in scale – in rural India, and they are further subdivided into a number of wards (!)

Which is lower than my initial calculations, but still quite staggering.

I was trying to figure out what a properly-extrapolated D&D-like universe would look like; without food or space constraints (people can literally just make more of both with magic), the population explosion would be insane.

The central empire of the setting has 2.7 trillion citizens. I’ve limited magic in the setting by adding a cost which is relevant to NPCs but not players (people age in proportion to their power, and using power increases your power), so farming and such still have a purpose. I think I have the political hierarchy worked out now, I just learned something crazy along the way about our own world.

Now I need to figure out broader economics.

Long story short, the number of hamlets you need to support a capital city of more than a hundred thousand people is staggering.

Large part of the reason for royal progresses. Keeping the court fed is expensive and consumes a ton of resources. By moving on a circuit, you (a) permit the build-up of resources again in the last area – be that your capital or the last lord – that hosted you (b) spread the expense around (c) check up on the loyalty of those same lords by reminding them of your presence and power (d) reduce their resources to build up an army etc. by instead having to expend it on hosting the court (as well as the propaganda element, the chance for the common people to get at least a glimpse of the monarch, and the rest of it).

Where did you get the number 6 from? This sounds really really interesting but I’m still quite confused by your model.

Tesselation; hexagons, basically.

It is almost certainly wrong; there is no reason to believe a capital can support the same number of sub-city regions as each city can support towns can support villages can support hamlets, or whatever. And calculating it out, it appears it might be too low anyways; England’s numbers only work with a constant of 8-12 there.

But my goal wasn’t to get it exactly right, it was to get a handle on what the right kind of numbers would look like.

I’d be interested to read a more detailed account of your project, including what numbers you found worked best for your fantasy world and how your model compares/maps on to examples in history.

Which is why there were either zero or one such cities in actual preindustrial nations. Mostly zero, and if there was one it was usually because it had stifled the development of any other large city in that nation.

I found this to be quite helpful for such matters.

I’m not sure if Scott bothers with the OT, but if not, I’d really appreciate if anyone could refer him here, please please please. I’d really appreciate it.

I’ve experienced a strange kind of loss today and I’m trying to figure it out.

It started when I met a girl about a year and half ago. She was really cute, and short, and she felt perfect to me, because at 5’3 there aren’t too many girls that give me a height gap, which is really important once you factor the high heels. At the time though, I was too anxious to actually ask a girl out. The situation also might as well not have worked – I was a waiter at the restaurant and she was a guest. I’ve got her name by looking at her credit card, and yes I know it’s creepy, but I’ve felt like it was justified – she was really sweet. I’ve looked at social media profiles out of curiousity but they’re mostly inactive.

Recently, she started working at the reception desk of my gym, I was leaving one day and she told me goodbye and I was really happy, like wow, I actually meet her again! The next time I went to the gym I wanted to give her a thanks, because that day wasn’t so good and her goodbye made it much better, and also to ask her if she’s available.

Nope. Boyfriend. Maybe it was because I stuttered, it was really difficult for me to open up. When I was in first grade, I asked a girl out and got laughed at and I only asked a few girls out since then, but my courage kept being shut down when they told me about their boyfriend. I was really excited at getting the courage to even if it wasn’t smooth, but no, she had a boyfriend and I have a broken heart.

I know my behavior here is probably a bit obsessive – but I don’t know how to deal with my feelings now. I can’t tell if I’m feeling bad because of the rejection, or maybe because ever since I met her I got into this fantasy that I’ll meet her again and get my chance and it’ll work and it’ll be some happily ever after or maybe I just regret I didn’t took the chance back then, a year and half ago.

I’m just entirely unsure how to deal with it, and it’s sapping out my other things (I have no motivation to program, or to do anything much) and I don’t know how to solve it. It just feels like such a big wasted opportunity and I can’t let it go. Everything I do just feels like it won’t make me happy. It feels secondary to the sadness and disappointment.

I’m not sure I’ve seen Scott in the OTs. Would you accept advice from other people?

I won’t decline anyone’s kindness. Please do.

First piece of advice: give it a few weeks. What you’re describing stings a bit, but it’s not the kind of thing you’re going to grieve over. How many girls from years ago can you remember having longed for from a distance only to get up close and find out they’re unavailable? Do you lose sleep over any of them? Probably not.

I don’t know how old you are or where you’re at in your life. All you’ve told us is that you wait tables and that you go to a gym. I infer from this that you’re pretty young — probably early 20s, late 20s at the most. Since you read SSC I infer you are above-average intelligence and likely to earn more money than typical waiting jobs in the future. I also infer that you are romantically lonely and looking for a relationship.

People here always give me crap for this but my advice to lonely people looking for a romantic relationship is always to get a dog and take it to a dog park and meet women that way. That’s what I would do if I wasn’t married.

I know dogs aren’t for everyone, so if that’s a nonstarter then ignore this, but I think it’s an ideal way to meet women for multiple reasons. 1) Even if you’re completely unsuccessful, you’ve still gotten your dog healthy exercise. 2) Even if you’re unsuccessful, you might still make some new friends. 3) Having a dog puts you in an authoritative position of responsibility. That is attractive to women and is also good for your own personality development if you handle it right by being a good dog owner. 4) Being a good dog owner requires many of the same skills that make you a good father, and that is attractive to women too. 5) Women who have dogs are preselected for other attractive qualities. 6) Your two dogs playing together is an automatic conversation-starter, plus engaging in conversation is easier for most people while they’re petting a dog. 7) Probably other stuff I’m forgetting right now. NOTE: Don’t get a dog unless you’re ready to properly care for it; I’m just saying if you are, you can include it in your romantic strategy.

I appreciate your help. And your guesses are correct.

I’m skipping the dog idea though, I’m bad with pets. Had a parrot.

Would appreciate responses from others, as well.

Fair enough. I think “wait a few weeks” is still good advice for you though, with respect to the feelings you mentioned.

Do. Not. Do. This. And Well, don’t suggest it.

You’re committing to rewriting how you live your life for the next decade. You can only live in about a third of the homes you could before, and that’s if your city is dog friendly. You will find it 10x as hard to move to a new location. You can’t take a vacation ever again without spending weeks working out logistics.

(It also won’t work. Girls talk to you at the dog park because you’re hot and it’s a convenient excuse.)

How about the low cost version of the strategy. Don’t get a dog, do go to the dog park, strike up conversations with women who are walking dogs?

I’m not on the dating/sex/marriage market any more, having managed a successful long run contract quite a while back. But I do walk around my neighborhood, encounter people walking dogs, and interact with them. It seems do be a reasonably easy way of striking up a casual conversation with a stranger.

See what I mean?

Although I’m not sure about going to dog parks without a dog. I’ve done that a few times with my daughter, because I was trying to get her to be more comfortable around dogs and also to see how good dog owners interacted with their dogs, as a prelude to getting one ourselves (hasn’t panned out yet). I think most of the people there with their dogs figured that out by looking at us, but if it was just me instead it might have come off as creepy.

Isn’t there a website where you can sign up to be a dog walker? It’s like Uber for dog walkers. That sounds pretty great: you earn money AND take a dog to the dog park with all the dating opportunities it affords* but without the restrictions and responsibilities of owning one. Although one drawback is you don’t get the benefit of being a dog owner and instead sort of align your brand with more of a “man for hire” thing, and transience is probably less attractive to women, but who knows maybe it’s not a big deal.

*And yes, Andrew Hunter, it can afford you plenty. I have an ugly friend (gangly, scrawny, goofy-looking face) with a cute dog (yellow lab mix, looks like a big happy puppy even though he’s like 8) and when we go to the dog park girls are always talking to him. Maybe this won’t happen to anyone but don’t act like it is an impossibility.

Most of that is a pretty serious exaggeration.

Housing is an issue if and only if you’re in a very tight housing market, otherwise you can find plenty of places willing to let at least smaller dogs in. And if you own a home you can of course do what you want.

It is not “10x harder to move” unless you are moving somewhere like Hawaii or changing countries.

It does not take “weeks” to make arrangements to go on vacation. It takes a few hours to find a decent local dog boarder and get them your dog’s vaccination records, and after that it’s a five minute phone call to set up a reservation whenever you need it. It’s not super cheap, but if you can afford the vacation in the first place it’s not much of a burden. Certainly for me it’s one of the easier aspects of planning a vacation.

They definitely do get you positive attention. Heck last time I picked up my dog from the boarder I got rather flirtatious comments from two separate attractive women my age in the span of a couple minutes. I am not the sort of person that normally happens to sans dog.

Plus dogs are great, better than a girlfriend in a lot of respects anyway. Certainly they give you somebody to commiserate with when you get rejected.

Anyway DunnoWhatToDo already turned down a dog for perfectly valid reasons and that’s fine. But it’s not generally bad advice, as long as you’re cognizant of the responsibilities involved.

>How about the low cost version of the strategy. Don’t get a dog, do go to the dog park, strike up conversations with women who are walking dogs?

Or you can offer to walk a friend’s dog. Or you can become a dog sitter and get paid to walk around with a dog.

In any case, I kind of feel that the type of person that gets into conversations with women in dog parks is also the kind of person who gets into conversations with women in other places, so I doubt getting a dog will help.

Yep.

It’s worth remembering that virtually all “Here’s how lonely and introverted and nerdy guys can get better at talking to women” advice also applies to handsome, athletic, extroverted, charismatic guys too – and they are listening to it and following it as well.

If you’re the weird creepy guy that no girls want to talk to at school, then you’re going to be the weird creepy guy that no girls want to talk to at the dog park as well.

Sometimes when out for a walk with my gal, because I know she’s shy, I’ll say “Can we pet your dog” when a nice dog goes by with their human. Fewer than one person in 20 says something like, “Actually, she’s really skittish.” The rest invite us to pet the dog. (I’m not that big on petting dogs; I do it to be social. But my gal enjoys it, and it’s a sort of way to admit that I know it’s frustrating for her that I think we aren’t ready for a dog ourselves).

But for meeting like-minded people, unless you know a neighborhood that’s really highly concentrated with people who’d be a good match for you (maybe a young people’s hang out, where everyone has the same subculture and is nearly the same age), I really suggest you think about dating online, or through a specific meet-up sort of thing (like a young dems networking hour), rather than trying to connect with strangers. Outside of a few places in our lives like college, where we’re surrounded by people in the same stage of life, we have to meet *a lot* of random people before we’re going to meet a good match.

Also, the short guys I know who’ve learned to dance highly recommend that, if it’s an option.

It is fine that it hurts. It is fine that you have regrets. The important thing is that you didn’t compound the regret by not asking again. You asked, she said no, that sucks. Next time it won’t hurt quite so badly, though it’ll still hurt. The alternative, that there isn’t a next time, means that you will spend the rest of your life hurting over this (and whatever other past missed opportunities / noes there have been) and rather than lessening over time, those pains will get worse.

Paradoxically perhaps, the key to lessening the hurt you are feeling now is to go out and find new potential hurts to inflict on yourself. Don’t wait another year and a half. Hopefully at some point someone will say yes, and if and when that happens as long as that relationship keeps going the prior noes will mostly fade into irrelevance.

I’d add that it is important to remember that such pain is temporary. “This too shall pass”

IMHO this is good advice.

I went through this a few times when I was younger. You are doing better than I started off doing if you are able to ask. I think it is a pretty common experience. If you are clinically depressed and can’t handle it, treat it as any other clinical depression you can’t handle (ie seek help). If you think you can deal with it on your own, it will take a few months (and possibly another girl) and then you will feel better.

(I expect this sort of thing operates on the same system as breakups, just with a fully imaginary and hope-based relationship. I would never have admitted this publicly when it was me going through it, but I guess I can say it now that it’s somebody else. Breakups are always really hard but people do get over them.)

I don’t know if this helps, but a very long time when I was very down about something, probably a woman less interested in me than I was in her, I found some comfort in the solidity of the external world. The existence of the tree I am touching does not depend on my mood, and it will still be here when I feel better.

Yeah, I think I can handle this myself.. try and meet someone else.. still sad about it, and could barely get any sleep.

> (I expect this sort of thing operates on the same system as breakups, just with a fully imaginary and hope-based relationship.

That’s a good way to describe it. I’m not sure if this is the right idea, but maybe I’m just sad that the.. loss of a fantasy? I know it feels silly and stupid to get caught up on something so minor that happened a year and half ago, but at the same time I’d be lying if I said my emotions aren’t genuine. I’m feeling too conflicted between “time to get over it” and “there’s only one of her”. And I just don’t know what to do about it, it feels like an internal bravery debate. Both sides have their merit. It’s really hard to choose.

It is quite unlikely that, by pure chance, you happened to encounter the one woman in the world best suited to you.

David:

I can agree with you on an intellectual level, but not on an emotional one.

I did run a rough back of the envelope calculation on the subject and concluded that the woman I ended up with–we’ve been married for over thirty years now, with two adult children–was about a one in a hundred thousand catch.

In an emotional level, isn’t it enough to believe that the one you lost is sufficiently better suited to you than average so that your chance of finding another as good is low? It isn’t as if you get to search the entire world population.

That probably isn’t true either, but I can easily see why you might feel it was true. At least for a while.

I’m no expert, but I do know there’s no perfect angels out there waiting for you (or anybody), and I can guarantee you this person is very flawed close-up same as you and I and everyone is. If you can manage, I’d strongly suggest don’t pin all your hopes on one lady before you’re going out with them (its great to be devoted in a relationship, but never to someone you don’t know). You did a great job to ask, its scary stuff for everybody but worth it, and remember the answer was not about you!

Congrats on actually asking her out. That’s tricky, especially when you’re not used to it, and—even if you slightly fluffed the delivery—you should be proud of it. (But not the kind of proud where you rest on your laurels; the kind that spurs you on to do more, and better, in the future.)

If you see her there again, try not to feel too sheepish about having asked her out. I don’t think you have any reason to be embarrassed, and I expect she’ll be quite friendly to you. (She sounds like a friendly person, and it’s more likely to have raised you in her eyes than lowered you, even though she had to decline.) I’m now very friendly with a woman whom I asked out and who declined me somewhere I frequent. Though it may be hard for you to be very friendly if you’re that heartbroken.

It’s painful (my God, I know it’s painful), but I’d say your best option now is to give up on her as thoroughly as you can, lay your dreams of being with her totally to rest, etc. When you can bear it (this probably won’t be straight away), you may find that finding other women to pursue helps to cheer you up. It doesn’t even need to be anything definite: even the glimmer of a possibility with other women can take the edge off the sting, I think.

Good luck.

Update:

https://slatestarcodex.com/2018/01/31/open-thread-94-25/#comment-596660

I made the mistake of subscribing to new messages on the conflict vs mistake thread, and wound up with a horrible impression of the other followers of this blog – far different from the one I’d gotten simply reading whole articles, comments and all.

I think this is a potentially interesting example of how presentation matters. The individual responses drowned me in the kind of sub thread I’d normally scroll past, consisting in this case of people with strong negative opinions about some group of people pontificating about those people’s complete vileness. At least the groups weren’t categories that folks are born with, or otherwise can’t avoid. They were, IMO, inaccurate strawmen, unless the posters make a “no true scotsman” argument – people of similar opinions, who aren’t completely bad, aren’t really members-of-hated-category, because the definition of hated-category includes that members are completely bad.

FWIW, there were hated categories that are commonly associated with both sides of the US political divide … at least by the opposite side. (The main message I took away was that the posters were unthinking members in good standing of their respective subtribes. That, and a bemusement at how discussion stayed even remotely civil, with that level of bias and hatred on display. Perhaps the comments were later moderated out?)

So on the one hand, “how do you do it” – and on the other hand, is there a better way to deal with notifications of comments.

Conflict vs. Mistake is also one of those posts that’s gotten substantial exposure outside the blog and so attracts new commentators, who mostly suck. Happens every time Scott puts a lot of effort into a piece with culture war valence.

How do you subscribe to new messages?

The options are below the ‘Post Comment’ button.

From Jacob Anbinder at Democracy: Politics is Failing Mass Transit. The argument is that the crises in big-city transit systems are being exacerbated by the governmental structures involved. The Progressive Era impulse to move public services to arms-length public authorities so they wouldn’t be subject to the whims of electoral politics has resulted, decades later, in these authorities being unaccountable to anyone and unresponsive in the face of systemic breakdowns.

This is a strong case, but at least here in New York, there had been substantial issues with the city-run subway system that precipitated spinning it off to the NYCTA (since merged into the MTA). Notably, the subway was constantly underfunded due to the elected city government’s reluctance to raise fares and risk a public backlash. Privatization is a possibility, but would it be selling the entire system to a single operator (who would then have monopoly power) or breaking it into competing companies (thus losing the value of a single citywide network)? Would they set their own fares (possibly pricing working-class New Yorkers out of a commute) or would fares be regulated by the city or state (which, of course, is what drove the original private companies out of business)?

There don’t seem to be any easy answers here. (And for those tempted to suggest “just drive everywhere like a normal person” or “jitneys and UberPool” – yes, you’re very smart, shut up.)

Six years ago I would have said it’s a no brainer, give the subway back to the city. Adjust the tax split between city and state to compensate. The city has plenty of non-fare revenue sources it can use to supplement. And bring back the commuter tax to boot, but I digress.

That’d still leave LIRR and metro-north under the clusterf&*k that is the MTA, but at least the jewel in the crown would be under the control of a more accountable entity. But after a full term and facing another of BdB doing his level best to restore the city to the former glory of the Dinkins administration, I’m not so sure.

What makes it all the more depressing is it’s hard to imagine anyone else doing better. Even back when Republicans could still win elections here, Pataki and Giuliani were just as indifferent to transit issues as Cuomo and deBlasio are.

Other systems have the additional problem that there’s nobody to turn them over to. I think specifically of the electrical-fire-prone Washington Metro. The DC government, competence aside, really shouldn’t be taking over a system that’s mostly situated outside the District of Columbia, but likewise the states of Maryland and Virginia and their various localities don’t have a good claim to run it either, so they’re pretty much stuck with the convoluted WMATA arrangement, for good and (mostly) for ill.

Provide the system with more money, it’ll get lost in graft, waste, and corruption. Try to do something about the graft, waste, and corruption, and lose the support of those who benefit from it. It’s not a matter of indifference, the problem can’t be solved under the constraints available.

In the classic version of the problem of a minority with concentrated interest vs a majority with diffuse interest, for any individual member of the majority the interest in question is quite small.

For example, if the FDNY rips us off with poor service and very high costs — well there aren’t that many fires anymore and even if it is 5x more than it should be $2B is still only a little more than 2% of the city budget and funded out of general funds. On the other hand the gross inefficiency and incompetence of the MTA is something that affects many members of the majority in substantial and quite annoying ways. And they see the costs more directly in the form of fares, tolls, and dedicated taxes.

I think NY/NYC politicians could come out ahead politically by fighting the MTA workers (including management) and contractors *if* they could actually beat them.

It doesn’t really seem like there’s an obvious good solution.

The MTA is a mess but, as Brad pointed out, the current city government isn’t exactly wowing us with their competence either. Turning it back over to the city isn’t necessarily the right move.

I don’t have a strong opinion on privatization one way or the other. It might be the best move but I I’m skeptical that it would fix the underlying problems.

To the extent that one of the “problems” of mass transit is something like “It’s very expensive to build and it’s primary customers are poor people who require it to be very cheap to use” – privatization almost certainly can’t help.

The “private sector solution” to a problem like that is usually something like “This cannot be done profitably so let’s not do it” which does not seem like a solution anyone is willing to accept here.

> it’s primary customers are poor people

You don’t know what you are talking about for a change.

A different private sector solution was jitneys, but they got effectively legislated out of existence because the competed with the trolley companies.

Did I call that we’d end up on jitneys or what?

They’re still around, called “dollar vans”, mostly (but not entirely) operating illegally. Due to the cultural milieu in which they operate being so far from mine, I’ve never used them, and for similar reasons I doubt anyone else here has either. But simply on grounds of capacity and labor cost (a van fits 18 people, a train fits 1800 people) I don’t think they’re a workable substitute for the MTA.

I have. Though by the time I used them they were $2 vans, not $1. If you live off flatbush, they are very convenient.

I’m not understanding the argument against privatization and then regulating the prices. It works fairly well for utilities and is based on the same economic reasoning.

LILCO

IRT and BMT were price-regulated private companies that ran competing subways. Their fares had always been five cents. The companies wanted to increase fares, because they weren’t covering costs. The city said no. Result: IRT and BMT went bankrupt and the city took over all of the subways.

Re privatization, compare British rail – its trajectories (both good and bad) stayed pretty much the same after privatization, so it probably doesn’t matter that much unless government is specifically dysfunctional. By specifically I mean “There’s a specific guy running the program who’s awful” or “there’s a specific regulation that ruins it”. General government dysfunction probably isn’t solvable by privatization, since the private system still has to deal with the government for subsidies and permits and such.

(Also, anyone who says “just drive” has clearly not driven in NYC. Subway is significantly faster).

I’m not sure that’s a problem. Wouldn’t it pay multiple companies to coordinate in order to provide better service and so get more customers and make more money?

I’d like to create this as a sort of open post for talking meta about Jordan Peterson.

For instance, is it just me or does he look like he’s terminally ill? True, some people just look like that, but I’ve seen videos of him from a few years ago and he looked much healthier.

Also, why is almost every single video of his on Youtube so misleadingly titled? (Or at least outrageously titled; I haven’t watched every single one.) They’re not all posted by the same person so that seems like a remarkable coincidence, especially because misleadingly titling videos doesn’t seem like the kind of thing that would be done by people who are into Jordan Peterson, although I don’t really know the demographic particulars of his fans well.

How do you guys feel about the statement “Jordan Peterson is the Werner Herzog of academia”?

In some of his interviews he explains that hehas had serious health problems within the last couple of years, though I don’t know the details. And I hadn’t particularly noticed a glut of misleadingly titled videos, but one vague hypothesis is that because he speaks out so much against the radical identity-politics left, he has a common enemy with the sort of people who are on the other end of the horseshoe, but because he is basically a centre-right traditionalist as far as I can tell, if you are of a radicalised identity-politics non-left persuasion (there seems to be a fair few shares from people of a radicalised id-pol MRA persuasion for instance), you enjoy seeing him run rhetorical rings around your opponents, but what he says doesn’t actually support your position that much either, so you end up massaging the title a bit to make it sound like it does?

The videos of his I watched (at Conrad’s recommendation, iirc) were titled “Bible lecture series I: who is God?” or something similar and was as advertised.

I think you mean perhaps short clips others have uploaded?

Yeah. I started with the Cathy Newman interview and have been clicking on “recommended” videos ever since. All or almost all of those have titles that are misleading or outrageous. Obviously the ones Peterson himself uploads will not have that issue.

FWIW, I don’t recommend his Bible lectures unless you’re already a JBP fan. The material is new and not particularly well-refined. It takes Peterson eight hours to get through Adam & Eve. The first three episodes are basically a condensed version of Maps of Meaning.

His Maps of Meaning lectures, on the other hand, are the products of a book he wrote 20+ years ago, and he’s been lecturing on for about as long. By the time you’re watching the 2017 version those are concise, quality explanations of well-defined concepts with insightful examples.

The Bible series is entertaining for a JBP fan (and Bible fan), but I really think he should have written The Psychological Significance of the Biblical Stories book first, and then made the lecture series. I understand why he did it. I mean, strike while the iron is hot. But I think it’s very much a work in progress, and I hope after he’s done with the lectures he can pick out the grand themes and write a concise book out of the material.

I guess it depends on the audience, because I feel the opposite way. The bible series is what got me hooked on him as a thinker. The ability to talk engagingly for 8 hours on Adam and Eve (and I have no particular interest in the Bible as “The Bible”) is a revelation itself. I find his more refined stuff to be less engaging (though not uninteresting just not as good).

When I watch videos of Jordan Peterson on YouTube, I tend to look for official sources, like his actual channel (he actually has 2, 1 for his long-form stuff including lectures, Q&A, long-form interviews, etc, and another where he shares short ~5 minute clips cut from videos from the former channel) or the actual outlet that interviewed him or invited him to lecture, and I haven’t found those to be particularly misleadingly labeled. I’d recommend seeking out those sources; in general, I think looking at the primary sources is better practice.

I have seen misleadingly titled videos pop up in my recommendations, usually of the form of something like “Peterson DESTROYS SJW” or “10 times when Jordan Peterson went NEXT LEVEL BEAST MODE” or whatever. My guess is that these clip-show-type videos are put together by people who have been abusively repressed by the SJW-left that Peterson often butts heads with (and commenters here know that there’s no shortage of such people) and thus find someone speaking openly and confidently against them to be incredibly refreshing and thus celebrates it in a typical tribal way. Interestingly, Peterson himself has noted that he’s observed some of his fans doing things like this and says that he dislikes it, as he doesn’t see the exchange of ideas as a battle to be won or lost, and that treating it like that just increases polarization and makes people dig in their heels (I guess that puts him more in the mistake theory side of things?).

After the bizarre Channel 4 interview Peterson gave this interview where he discussed it (and many other things). This interview I thought was excellent, and I was very impressed with the interviewer, who had actually studied Peterson’s work and was able to ask interesting and insightful questions. I was dismayed the rest of the stuff on his channel was in Dutch because I would have liked to have seen more. Anyway, yes, Peterson talks about the reaction to the Channel 4 interview. He “won,” but not the way he wants to “win.” He wants people to talk to each other, and a deescalation of political polarization, not simply to “win” ideological battles.

@Conrad Honcho

That’s pretty funny, because the blog the interviewer works for is known for politically incorrect right-wing edgelording.

But I guess that when something is so far out of the left-wing Overton window that the regular media starts edgelording*, the opposite kind of edgelording cancels this out. So guys who normally edgelord to the right suddenly are the ones who do the respectful interview.

* My newspaper, which normally is relatively decent to right-wing ideas, went Cathy Newman-light on Peterson.

I don’t think he looks ill. But his videos are rarely professionally lit, so “bad lighting” can also be a factor. I could also believe he’s under a lot of stress. There are a lot of people who support him, but an awful lot of people with much louder voices who want him destroyed.

Can you give an example? Are you talking about videos he titled on his channel, or one of the dozens of people who take clips from his videos and repost them? If it’s the latter then the explanation is obvious. Those are just people posting popular things with clickbait titles for ad revenue.

I see the comparison, but it’s not like Peterson is using academia to tell people heroic life stories or something. He’s a clinical psychologist. His job is “someone is having big problems with their life and I give them sound advice.” Taking that to a wider audience with books and youtube videos isn’t a radical departure.

Peterson reminds me of Herzog most when he talks about mythology and Jung. The wider sweeping statements about mankind or the human condition or whatever that veer into the poetic. “The yogurt is alive, yet nobody can hear its cries of pain.” (That’s paraphrasing a joke Twitter account, Werner Twertzog, if I remember right.)

I wish I hadn’t mentioned the video titles, it was just something I found amusing and am not actually perplexed by now that I think about it.

He has been borderline exhausted for the past year and a half. If you watch his (iirc) November Patreon Q&A he gets asked how he is feeling and he talks a little about how he was almost overwhelmed. He was close to losing his job, became embroiled in a national level controversy, has spoken at dozens of events, produced a lecture series for a large live audience, finished writing a book (which he also did the reading for the audio version), and I think he strongly implies that he was battling a depression episode during at least a part of this stretch.

This is a tangent, but what is borderline exhausted? How is it different from regular exhausted?

He is still working and producing content, I think exhausted would mean he actually had to take a break from working to recuperate, borderline implies being near his limits not over them.

@baconbits9

He also has to avoid making any misstatement or what can be misconstrued as a misstatement, because what he says will be assumed to be in bad faith very often. It’s like being on Jeopardy, except you have a noose around your head and are standing on a trap door that will open if you get an answer wrong.

This seems like a very high-stress life to me.

I agree but isn’t that basically true of any public figure?

I doubt Ta-Nehisi Coates worries too much about saying the wrong thing.

@Well…

No, if the media moderately likes you, they tend to interpret ambiguous statements in good faith. If they really like you, they tend to interpret explicitly malicious statements (much) more generously than what was actually said.

Furthermore, if they moderately like you and you make a serious faux pas, they will usually forgive and forget after some time. If they don’t like you, they will keep bringing it up again and again, steering any conversation to it.

The Overton window is not just about what people consider reasonable, it’s a useful concept because beliefs outside of it get treated differently from those inside it.

@Wrong Species & Aapje:

That’s only true if “the media” you’re worried about is limited to mainstream journalism. TNCoates quit Twitter after all! (Multiple times?)

Where you stand WRT the Overton window probably has somewhat to do with your career prospects, but other stresses of being a public figure can easily get you harassed constantly no matter what.

@baconbits9

I watched the interview with the Dutch interviewer and Peterson said that his daughter had a severe food allergy that was very hard to diagnose (the symptoms only started 4 days after ingesting the food and then lasted for a month, making it hard to figure out that it was an food allergy in the first place and also hard to test what food item was responsible).

Anyway, his daughter managed to figure it out herself and then Peterson realized that he probably has a milder version of the same, causing depressions. His own health improved after changing his diet.

I just read something written by an american living in germany. It’s about painkillers and differences in the consumption and the way they’re viewed in those two countries.

Could someone tell me if she’s typical in her attitude towards taking medication?

https://www.nytimes.com/2018/01/27/opinion/sunday/surgery-germany-vicodin.html

(I’m german and I have to say I was apalled at how eager she was to take medication. Whenever a doctor was quoted I wholeheartedly agreed, that you should take as few painkillers as possible for exactly the reasons they gave.)

By anecdote, it was not typical in the 1990’s for Italian hospitals to give morphine to traffic collision victims with broken bones until after the bones had been set. In contrast, in the US, the ER docs would absolutely want pain medication on board before beginning such a procedure. In another contrast – the US and UK attitudes towards pain control in child birth have long differed.

I think there are long standing differences in cultural medical practices. I think that there is evidence the US recently overshot in attempting to control pain. Having said that – while I might have been okay with the idea of a NSAID post surgery, I would have infuriated if my pain level post surgery had been high and my physician refused to prescribe medication to help ease it. No reason for a week’s supply, but 3-4 days of a low dose to dull the ache of surgery and allow me to resume normal activity should have been good.

I’m American, and I find her obsession possibly excessive; I’d be more inclined to trust my doctors. I’d have to know how much it hurt. However, her attitude seems pretty normal for the U.S. When my wisdom teeth were extracted, I was given vicodin by default. It was probably excessive in retrospect. I only took it once, but I think I was given more than one dose.

Bitcoin succeeded as a speculation despite failing as a cryptocurrency. That’s not what the lesswrong people were predicting.

Being smart made them aware of bitcoin before other people. It didn’t make their analysis better.

Culture war questions are allowed in this thread, right?