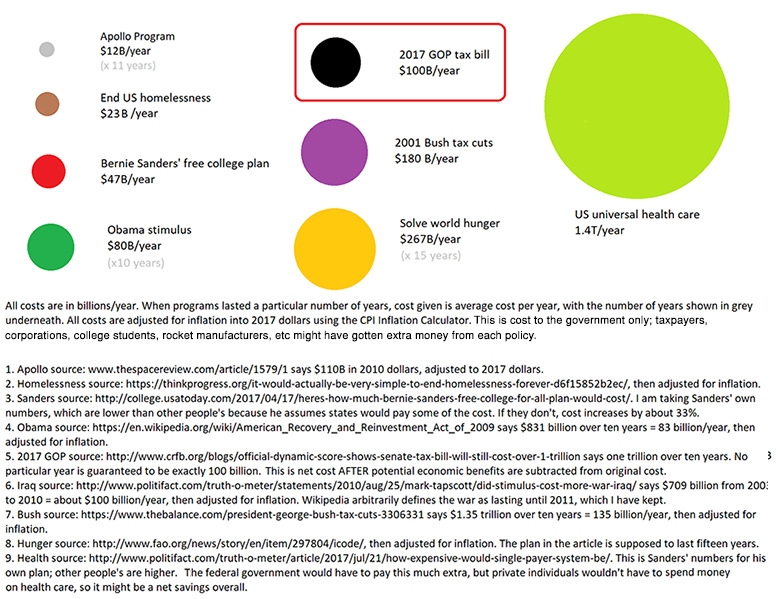

Here is the cost of the current GOP tax bill placed in the context of other really expensive things. Although it’s not quite enough money to solve world hunger, it’s enough to end US homelessness four times over or fund nine simultaneous Apollo Programs.

I’m writing this post sort of as penance. During the primaries, I wrote a post arguing that Sanders’ college plan was bad. And compared to any reasonable use of the money, I still think that’s true.

But I worry that people – including me – focus way too much on the kind of bad idea that tries to help people but ends up being too expensive, and not enough on the kind of bad idea where there’s only the thinnest veneer of a claim anyone will be helped at all. If Sanders had been elected, and we were debating his college plan, people would be worried. The affordability of every piece of it would get run over with a fine-toothed comb. Its irresponsibility would be noticed.

Well, instead of Sanders we got Trump. I won’t say nobody’s talking about the tax plan – the problems with it have been all over the news – but are our fiscal irresponsibility detectors being triggered twice as strongly as they would if it was Sanders’ college plan we were considering?

There must be a toxoplasma effect going on here, where things that are possibly bad get debated to pieces, because debating them is so much fun – but things that are definitely bad, things that nobody likes, get through much more easily. Even more pessimistically, if Sanders proposed free college for everybody, it would get a lot of resistance precisely because the fact that so many people would benefit would make sure everyone knew about it and was thinking about it a lot and understood how big a deal it was. Since nobody except a few corporations benefits from the GOP tax plan, how do we even get a feel for how big and important it is?

Next election, if he’s running, I’m probably going to support Sanders, who seems like a decent person who really wants to help the poor. This is going to be a weird choice for someone who flirts with identifying as libertarian, given the whole socialism thing. But the thing is, we have antibodies to socialism. When people push socialism, we give it the scrutiny it deserves. I’m more worried about the things we don’t have antibodies to, and one of them is going to be passed by a joint session of Congress in the next week or two.

Can somebody give the arguments in favor of this tax bill? There have to be some, right?

The decisionmakers get benefits from the big corporations in some form?

Expanding the standard deduction will allow people to keep more of their own money while simplifying tax preparation. Lowering the corporate rate will make it more attractive for businesses to stay here because the new rate is closer to the global average. Estimates are 40-80% of the corporate tax rate will go towards higher wages. Changes to the repatriation tax will encourage companies to bring their money back to the US and will cut incentives for companies to move headquarters overseas. Cutting taxes for pass through corps will encourage entrepreneurs and small businessmen. Getting rid of the SALT deduction will stop poor states from subsidizing rich states and stop the penalty of consumption taxes which are better way to tax.

It increases the debt, but rates are at a historic low so it is cheap to borrow money.

That’s not a good way of putting it. The net subsidy flows from rich states to poor states. The SALT deduction goes in the opposite direction but it isn’t nearly large enough to change the the sign. When it is eliminated the magnitude of the net subsidy flows will increase, not decrease.

Maybe “Stop taxpayers in states with low taxes subsidizing the local government budgets of spendthrift states” or something like that?

The thing about SALT is that it lets states (not necessarily the rich ones, but in practice the rich ones – well, the ones with big tax bases anyway) raise their local taxes higher than they normally would (because <100% of the additional tax is a net expense for the taxpayer) while simultaneously taking money out of the federal budget. That seems not quite right, though I lack the expertise to claim to know the actual impact of this.

It’s very hard to look at SALT as anything but a red/blue tug-of-war, but try to imagine starting with a blank slate federation and trying to decide whether to tax-exempt state and local taxes. Should someone who makes 100k and pays 10k in state and local taxes be taxed like someone who makes 100k and pays no such taxes, or like someone who makes 90k and pays no such taxes?

Presumably living in the high-tax locale comes with some benefits paid for by those taxes–insofar as the taxes are approximately a quid pro quo, as especially seen in elite public school districts, it’s silly to be able to deduct them.

On the other hand, if your state’s taxes are high because it has a very strong welfare program (or other things you don’t directly benefit from), then your taxes are more analogous to charitable gifts, and probably should be deductible.

In an ideal world we wouldn’t have a SALT deduction. I just don’t think sourcreamus’ description was accurate. And it was inaccurate in a way that is in my experience not uncommon. Within my state (NY) we have many people under the very much mistaken impression that upstate subsidizes downstate when there are very large flows in the opposite direction.

It is a subsidy to the state government. The government may subsidize people in poor states but the SALT deduction subsidizes the actual state.

Is subsidy defined by anything more than where money is spent?

If the Federal government gives Alabama a billion dollars to spend providing healthcare to its citizens (imaginary example) that’s a subsidy. If the federal government spends a billion dollars in California hiring coders to create the software for Obamacare, or a billion in Iowa buying corn, that isn’t a subsidy. Nor is it a subsidy if the feds spend a billion dollars in Virginia running a military base. In all of those cases, the benefit to people in the state isn’t the amount of money spent, it’s only whatever profit they make on selling what the feds are buying.

Is there a defensible definition of subsidy that your claim is based on?

I don’t think it is as simple as that. If there’s a factory in Virginia making widgets and the government buys $1 billion of them because the Senators from Virginia insisted, but no one gets any benefit from these widgets, then the entire amount less whatever materials were imported from other states should be credited as a subsidy to Virginia. The income of the workers in those factors is welfare by another name. Likewise the dividends to the shareholders of the widget making company.

After having written this comment it occurs to me that you may have been using ‘profit’ in a broader sense than is common to include the above. In which case I guess we agree.

Determining which States are subsidizing other States is highly dependent on the sources and destinations of money you consider. If you look at the “New York’s Balance of Payments in the Federal Budget” (pdf):

You see the OFFICE OF THE NEW YORK STATE COMPTROLLER making the argument that

When you look at the calculations, you see that (on page 11)

Then,

Amazingly, the money sent to individuals (table on page 26) Florida is second, NY is #33, and ND and Utah at the bottom. Who’d have thunk a lot of people retire in Florida.

Looking at money actually paid to the State of NY for grants (table on page 27) NY is fourth.

I personally think that when discussing Federal government policy you should ignore the payments made from the Federal government directly to individuals and focus on the money given to the State governments. I can understand why people would choose differently since a lot of the money given to the State is then given by the State to people.

If this were clearly and obviously true, shouldn’t New Yorkers be rallying for secession?

It’s not like we haven’t thought about it. The last civil war didn’t go very well for anyone though. More seriously there have been proposals for NYC to secede from New York state. My personal favorite was a 1969 independent ticket with the chutzpah to say we’d leave the state and _they_ would have to change their name to Buffalo.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Partition_and_secession_in_New_York#1969

I just estimated that 0% will go towards higher wages, so now “estimates are” that 0-80% will go towards higher wages.

But maybe we should focus on credible estimates.

Who did the corporations supporting the tax cut think would end up with most of the benefit?

Are you arguing that corporations wouldn’t support the tax cut if they only got 20% of it? That $300,000,000,000 or so isn’t enough incentive, and that they would only support it if they were going to get 100%?

Are you familiar with Ricardian equivalence? If find it implausible with respect to individuals, but you’ll find it underlying a lot of those 40-80% models, so it’s important.

It implies that corporations won’t be in favour of an unfunded tax cut if they get 20% of the benefit and expect to be on the hook for >20% of the future obligations it creates. Certainly they won’t be wildly in favour if the difference between benefit and expected future costs is positive but small, and yet they were. Workers seemed less excited.

I am familiar with Ricardian equivalence, I do not believe the following

1. That the average voter/poll respondent is familiar with RE or

2. That the people running the corporations now that would benefit from the tax cut will expect to be in the same situation when rates are raised

3. That those people can predict who will be in power and what types of taxes will actually be raised with enough surety to pass over what certainly looks like a solid deal up front.

I agree with you on 1, baconbacon, but, as I pointed out, that doesn’t really apply here.

2 confuses ownership and control, and is, I believe, wrong in either form. Corporations are built to be forward-looking, with forward-looking calculations baked into their share prices.

3. Is probably true, but substitutes “losses of uncertain expected value” with “losses of zero expected value”. These are pretty different. Given the much-heralded risk aversion of investors, the fact that the future costs of increased present deficits are uncertain should increase their impact on current owners.

You stated

If workers aren’t aware of RE then using their mood/reaction to gauge if the result will be good for them isn’t useful.

This confuses the real and the ideal. For example some shareholders aren’t just shareholders but are employees whose bonuses are tied to short(er) term performance. Share holders also skew older than the general population, and these older people often have a preference for streams of income (dividends) over asset prices. There are a dozen different ways in which the long terms stock price effect could be different from the short term incentives of the shareholders.

Additionally RE only holds if taxes are expected to eventually rise, it could still be rational to support the bill if you expected it to be a net boom for the economy, pushing up revenues across the board or keeping a political party who is (allegedly) in favor of lower spending/taxes, which would neutralize the RE issue.

Realistically though all these explanations, starting with RE are unnecessarily complex as the majority of shareholders, workers and tenured professors aren’t familiar with RE nor are the engaging in the type of complex projections that would be necessary to make truly ‘rational’ choices. There is simply to much stuff going on with the rest of their lives to be able to dedicate to such projections.

I do not know who you are, could you provide a link to your research so we can evaluate how good your estimate is?

There aren’t any links in any of these posts, sourcreamus. That only now seems to have become a problem for you.

For what it’s worth, I’m a PhD economist working with no general model of taxation and the economy, no professional focus on the area and an ideological prior against reduction in corporate taxation, ceteris paribus.

Go look at your “80% of the benefit goes to workers” studies and you’ll find much the same, I suspect, but in reverse. Then post the links with comparable summaries, maybe.

pd,

Expert consensus is fairly overwhelmingly against you, so there really is no reason for anyone to give any weight to what you are saying on the basis you provide, is there?

pdbarnsley is here questioning how expert the opinion is that disagrees with him. It is probably not very convincing to simply assert they are experts, but perhaps a few links or other citations might lend credence.

Considering even elite economists admit that the vast majority of their models aren’t based on reality and use a bunch of handwaving:

https://paulromer.net/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/WP-Trouble.pdf

It might make sense to listen to the CEO’s who will actually be making the decisions. Only 35% say they will increase investments and wages. The rest will just hand it over to their already wealthy shareholders via stock buybacks.

https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2017-11-29/trump-s-tax-promises-undercut-by-ceo-plans-to-reward-investors

Here are some links

Labor and Capital Shares of the Corporate Tax

Burden: International Evidence

International Burdens of the Corporate Income Tax

The ABCs of Corporation Tax Incidence

@userfriendlyyy:

Your Romer quote is about macroeconomics. I like to say that a course in macro is a tour of either a cemetery or a construction site.

The division of the burden of a tax among those affected, however, is straightforward microeconomics, more accurately labeled as price theory. The relevant analysis goes back at least as far as Marshall, which is to say well over a hundred years.

@DavidFriedman

I don’t care how long the profession has been counting angels on the head of a pin. When you are using Toy Models you aren’t operating in reality. No model anywhere can make CEO’s not pour the whole tax cut into stock buybacks to the exclusive benefit of the billionaire class.

@userfriendlyyy

Models suck. But the alternative (conjectures) sucks more.

Scott Sumner initially had some good things to say about the bill:

http://www.themoneyillusion.com/?p=32709

Although he’s less a fan of the Senate version, especially after republicans might keep the AMT:

http://www.themoneyillusion.com/?p=32734

The status quo corporate tax is a conceptual and practical disaster. It has one of the highest nominal marginal rates in the world but collects a middle of the pack percentage of GDP. It hits different companies in wildly different ways and massively rewards spending on accountants and tax lawyers. The US is one of only two significant economies that taxes companies incorporated in the country on worldwide income instead of only on income earned in the country. This amounts to a serious advantage for companies incorporated elsewhere. In order to partially mitigate the harshness of this unique rule we have a crazy system of deferred taxation which ends up encouraging foreign investment over domestic investment and also excessive borrowing.

The tax bills reform the corporate tax code. Not nearly as comprehensively as I would like, the resulting system is still a mess, but nonetheless significantly. It couples these reforms with a big cut, and that I don’t think is especially needed, but given the reforms that exist I wouldn’t say it is all bad.

On the passthrough side, which amounts to another part of the corporate tax code, the system is actually made worse — more irrational and complicated and rewarding of game playing. That anti-reform is in service of more cuts, which again were probably not needed.

As to the individual income tax there’s a mix of reform measures (e.g. eliminating credits and deductions especially in the House bill, less so in the Senate) and anti-reform measures (e.g. eliminating the AMT in the House bill or making it apply to less returns in the Senate bill). How to judge the overall effort is complicated by the fact that some of these provisions are set to sunset in ten or fewer years. The Republicans ask that we take for granted that they won’t be allowed to expire while the Democrats say we should look at the bill as it is. Like with the other parts reform here is only a part of the overall cut story.

Finally, there’s the elimination, or increase in the exemption for, the estate tax. I’m not an especially enthusiastic supporter of the estate tax, particularly given how it is so often evaded, but if it was going to be eliminated I would very much have liked to see the elimination of the step up basis for the capital gains tax for transfers on death. If taxes aren’t going to be owed by estates at the very least deferred taxes owed on capital gains shouldn’t just disappear into thin air because the person that owed them died. They should follow the asset.

TL;DR Overall I don’t think it is a good bill and don’t support its passage, but there are some parts of it that are okay solutions to legitimate problems.

That seems fine – my biggest beef against the estate tax is that you’re effectively taxing things that have already been taxed at least once, and often more than that. I’m fine with capital gains getting taxed at a fair rate that follows the asset once.

What does your ideal corporate tax reform (presumably revenue neutral, among other things) look like?

I’ve been trying to work out for years a way to replace the tax on corporations with taxes on the beneficiaries of corporations. I think that would be conceptually much simpler. You’d still probably want to have some kind of nominal tax on corporations (probably on revenue) to act as a frictional force and prevent the endless multiplication of every more elaborate nested corporate forms. But in terms of revenue I’d think if you could tax ways that companies pay out (in cash or otherwise) than you wouldn’t need to worry about how to define profit or where it was earned.

Unfortunately there is a hole that I can’t think of any way to plug. Companies have {domestic, foreign} {shareholders, debt holders, employees}. If the united states was the whole world you could put in place income taxes for individuals (including benefits) to cover employees, tax dividends and bond coupons, and tax capital gains. Then you wouldn’t need to worry about a corporate tax. Anyone that benefited from corporate profits would have reportable income which could be taxed on their level.

However given the existence of foreign shareholders how do you tax the capital gains they earn by buying and selling shares in your domestic companies? For dividends it’s easy, just make the companies withhold, but I can’t see how you could do it for capital gains. Even if you require share transactions to be registered they’d just form a foreign company to hold shares and buy and sell interests in that company, which would not have to be registered.

Alternatively we could decide that foreign shareholders don’t owe us anything. But I think most people’s intuition is that if someone is e.g. living in Barbados and is getting $100mm a year in dividends / realized capital gains from Apple, then he is benefiting significantly from goods and services provided by the USG (and CA government) and ought to pay something towards them.

Unless and until I come across some solution to that problem my second best choice is a territorial taxation system along the lines of what is common in the EU with a series of treaties and accounting conventions to try to stop the transfer pricing problem from making the systems a joke. And the elimination of various loopholes, exemptions, incentives, credits, deductions, etc. If we going to have social engineering I’d rather see it done on the spend side. With the possible exception of very clear and clean Pigovian cases.

Accidentally reported this post when I meant to click reply… I think the ability of both corporations and individuals to change jurisdictions is obviously the biggest problem to taxation in the world and a huge contributor to inequality. It drives governments into a spiral to compete on cutting taxes to retain corporate revenues and jobs. As money producing assets get more and more intangible this becomes a bigger problem, especially with tax evasion masquerading as intellectual property licensing deals. Big companies and extremely wealthy individuals will always be better equipped to follow the lower rate, which will drive the burden on people with less mobility and strain the middle class and governmental budgets.

Governments around the world need better coordinating mechanisms for taxation to stop this power imbalance. I’m encouraged somewhat by the rulings against Apple in Ireland because it seems like a step in the right direction.

Remember. The US still has the most powerful government in the world. If the Americans can’t even get the taxes that they’re owed, what chances do other countries have of getting their share of corporate profits to maintain their systems?

This can’t be stressed enough, zenmore. If even the mighty U.S. cannot be truly sovereign (in that it has to constantly cater to capital owners seeking the best returns, and thus has strict limits on what voters can actually have their government do), then that should be a sign of how democracy and capitalism mix (they don’t).

Unless, of course, you had a world government that could deal with global capitalism on an even footing.

Or, given that national governments seem here to stay, you could have “Capitalism in One Country.” Capital controls, autarky, etc. Then, theoretically, you could hold existing domestic capital hostage, force it to play ball with the only game in town on whatever terms the populace of that country, wants, and still have national sovereignty…although capital would still try to play different parts of that country against each other (as Amazon is doing now, shopping around for the lowest bidder, making cities pathetically kowtow to it one by one).

So, then I suppose you could institute capital controls in each state, or city…etc., forcing it to not flee Detroit, MI for Lansing, MI. But by that point you are talking about so many restrictions on what capital owners can do with their capital, that the government might as well take over that capital and decide how it will be invested.

Doesn’t that argument also imply that democracy and freedom–specifically freedom to leave–don’t mix? After all, the ability of a government to tax labor income is strictly limited by the threat that individuals might vote with their feet.

Democracy is a way in which governments make decisions. Those governments, like non-democratic ones, still face lots of other constraints.

Every time you spend your after tax income on consumption taxed goods you’re being taxed twice. The goal of a tax system is to raise the target amount of revenue as efficiently and equitably as possible, but the equity goal relates to treating persons, not dollars, equitably.

The “double taxation” thing is an unhelpful red herring. You need to show the an estate tax deters productive behaviour more than a practical alternative tax and/or that it hits a group who are deserving of special accommodation. I think that’s a hard sell.

But “I already paid my taxes” is just question begging.

@ pdbarnlsey

The estate tax is a tax on people who are bad at planning or are unusually unlucky. Last I looked, the costs related to litigating over the estate tax were a substantial fraction of the total tax collected.

In theory one could get a lot of money from taxing the estates of rich people, except that rich people have lawyers and are often willing to waste $99 on expensive lawyers and dubious money-losing tax-avoidance schemes in order to save $100 in taxes. People with lots of money and power and lawyers in practice can get loopholes enacted and arrange their affairs to maximize the use of these loopholes or can fritter away their profits in ways that are hard to tax. So you only get the big bucks from people who die unexpectedly early or are really bad at planning or are unlucky in that their affairs suddenly change in a way that breaks their prior tax-avoidance strategy right before dying.

If you ignore the cost to the economy of bad investments made only for tax-avoidance purposes and ignore the cost of the estate’s legal team and count the government’s legal efforts as basically free then the estate tax does bring in some net income, but not very much. Near as I can tell, the reason people like the estate tax is not that it’s a practical or cost-effective way to raise revenue, but merely that it feels like a way to stick it to (some) rich people. Though naturally not the most deserving ones. 🙁

Glen is certainly correct that estate tax collection is wildly inefficient. That said, there are much better reasons to support it than simply to stick it to rich people.

First, it is silly to call it double taxation, as it’s not a tax on the individual passing the money on. It is clearly a tax on those who inherit the money.

We’re always worried about the incentives of taxation. The only incentive the government should be concerned about wrt to inheritance tax is the that it discourages people with money they won’t spend in this lifetime from being productive. This is an important incentive, I will not deny, but I might point out it is unlikely to be as strong as the incentive of someone to make money which they will consume during their lifetime.

I’m not certain, but the one group of people who seem to spend money MORE inefficiently than the federal government are the heirs of multi million dollar estates. Even worse, it disincentivizes them from being productive themselves. If you think that there is correlation with becoming wealthy and being productive in the economy, and you think there is correlation across generations in being productive, this is even worse. I don’t have anything against rich people, they’re my friends and family!. I just think that passing money along down the line is bad policy.

I’m usually a very quantitative guy, but I have no numbers to back any of this up. It’s one of very very few opinions I allow myself based off anecdote. I’ve seen some very smart people in my family and in families I am friendly with rest on money that is comfortable, but far less than the average taxable estate. It really is a waste.

Glen, these sound like people with extremely low marginal utility of income and/or really bad priorities. I can live with transferring money from them to their lawyers as a cost of transferring some other money to the State. Some lawyers are quite nice people.

You are confusing revenue with profit. The fact that clients spend ten thousand dollars on lawyers does not mean that the lawyers are better off by ten thousand dollars. To get that money they have to spend time doing work, time that they could have spent doing work for some other client, perhaps at a slightly lower rate. Or reading a book, playing a video game, skin diving, … .

Seen on a longer time scale, money spent on lawyers is pulling talented people into being lawyers instead of doing something else with their lives.

The mistake you are making is a very common one–the same mistake I recently pointed out here in the context of claims about the amount by which the federal government subsidized different states.

Revenue is not profit.

In the hypothetical as stated, a person has the choice between A: handing over $100 to a tax collector, or B: paying $99 to a lawyer and keeping $1 as income. How does Plan B reflect “low marginal utility of income”? For any positive marginal utility of income, Plan B is objectively better.

And your “bad priorities” crack just hides an assumption that all good people must always place a positive value on handing money over to tax collectors. If you can “live with” taking people’s money because they don’t place a positive value on handing it over willingly, why, that seems mighty convenient for you.

Isn’t this a general argument against taxing rich people in any way? I don’t see how it is specific to the estate tax at all.

Maybe that really is your argument, but it seems deeply flawed – rich people are better at avoiding taxes, sure, but taxing them still seems important given that they have all the money.

On the passthrough side, which amounts to another part of the corporate tax code, the system is actually made worse — more irrational and complicated and rewarding of game playing. That anti-reform is in service of more cuts, which again were probably not needed.

As someone who has used passthrough entities, I internalized that the whole point was to substitute the individual return for the corporate return, which seems a fair trade-off. Now it looks like you’ll get to use passthrough but then still use the corporate rate if that ends up better. Maybe it’s status quo bias on my part, but that looks like a tax giveaway (one that benefits Trump personally) and not really a fair way of allocating out the tax burden.

Holding as a constant the corporate (C corp) changes it made sense to have a small cut to the overall top rate. Because under the new rates the double taxation rate (assuming qualified dividends or long term cap gains): 1- [(1 – .2) * (1 – .238)] = 39.04%

came out to be lower than the top passthrough rate of 39.6%.

But there was no reason for such a large cut and especially no reason for such a complicated structure with favored and disfavored passthroughs.

What is the point of making changes like this expire at all (if not to pretend it’s a permanent change because the expiration is in the fine print)?

The reason they expire is because of the the Byrd rule. Those rules in turn exist because a prior congress wanted to bias things in the direction of smaller deficits. If you think that deficits are a very big deal, then there’s your point.

Personally, I don’t think much of the filibuster and am not overly worried about deficits. So for me there isn’t much of a point.

It’s a cross between an accounting game, designed to work around restrictions put in place to avoid adding to the deficit, and a shell game, designed to disguise huge corporate tax cuts as a gift to the middle class.

Paul Krugman’s take:

Maybe I’m missing something but….why doesn’t Krugman’s argument work exactly the same the other way? IOW, as a rebuttal of Democrat criticisms of the bill? Arguments of that format have always struck me as a bit silly, and entirely unpursuasive to anyone who isnt on Team A or Team B.

“It only cuts taxes if it raises the deficit” and “It only raises the deficit if it doesnt cut taxes” should be just as good for either side of the argument, right?

On a strictly logical level: suppose I told you that an upcoming bill was either going to poison you or stab you, but not both. It would not be a good defense of the bill to say: “Ah, but on the flip side, either it will not stab you, or it will not poison you!” Either way, something bad is happening.

Regarding the details of the bill: even before the temporary tax breaks expire, the bill heavily favours the rich. This WaPo article has a number of graphs demonstrating the overall tilt of the tax cut, and comparing it to historical tax cuts. Even in 2019, before any of the provisions sunset, half of the tax cut goes to people earning more than 20K. By 2027, the top 0.6% would be claiming 60.7% of the cut, and people making $10K-$40K would actually pay more in 2027 than under the status quo.

In other words: the current bill is ridiculously regressive. Preserving the temporary provisions would bring it down to merely “very regressive”, at the cost of a significant hit to the deficit.

Hmm, that doesnt seem quite right to me. I like the analogy and I’m a strong believer in the “Yes, and” school of analogizing, embracing the offered analogy and trying to conduct the conversation in that framework, so I apologize that I’m not quite clever enough to express what I mean using the stabbing and poisoning metaphor, and will have to abstract it a bit.

To me, it seems more like they are saying you will either get:

Good Thing A, at the cost of Bad Thing B

or

Good Thing Not-B, at the cost of Bad Thing Not-A

And Krugman is, rightly, criticizing the proponents of this deal for trying to have it both ways….while trying to have it both ways himself. The supporters focus on Good Things, the detractors on Bad Things, but both are making the same error.

The only way out of this hypocrisy-trap, it seems to me, is to simply conclude (as, to be fair, you personally seem to be doing) that what matters is that the tradeoff between Good Things and Bad Things favor the Bad Things, and so whichever way it ends up working out, the net result is negative. But that isnt what Krugman is doing.

All major bills are written this way, the CBO has guidelines that it follows and everyone knows how the score will come out ahead of time. The ACA was written with provisions in the back half to give it a better score but that no one writing expected to be initiated.

@Chad:

It’s more like “Tolerable Thing Not-A, at the cost of Intolerable Thing B” vs “Tolerable Thing Not-B, at the cost of Intolerable Thing A”.

More concretely: “It only raises the deficit if it doesn’t cut taxes” is false. It raises the deficit either way, to the order of a trillion dollars over ten years. If the temporary tax cuts are preserved, it will raise the deficit even more. In this case, Tolerable Thing Not-A is “it raises the deficit, but only temporarily, and not so much that the Byrd Rule prohibits it from being passed with 50 votes”, and Intolerable Thing A is “it raises the deficit in the long term, and it can’t pass without Democratic votes”.

In the other direction, Tolerable Thing Not-B is “half of the tax cut goes to people making more than $200K“. (I said 20K in my previous post; that was a typo.) Intolerable Thing B is “60% of the tax cut goes to people making more than $1m.”

The asymmetry is that supporters of the bill need it to be acceptable on both axes — neither fiscally insane, nor a giveaway to the rich — while critics only need it to fail along one of the axes. There are more ways for a bill to fail than succeed.

Question about the estate tax: Why isn’t it just taxed as part of the income tax (you’re receiving money from another person)?

In general gifts are not taxable income to the recipient.

But they are to the giver. Since the giver’s dead in this instance, You could just take the tax out of the inheritance.

That’s the estate tax. The gift and estate taxes are part of the same scheme. Your estate tax exemption for example can also be used as a lifetime gift tax exemption above the annual exclusion.

Tyler Cowen doesn’t go as far as endorsing it, but suggests a rationale: it’s about attracting investment to the US.

Like Reaganomics/supply-side, but focused on corporations rather than individuals.

This.

At the margin, a lower corporate tax rate in the U.S. attracts additional foreign investment and incentivizes U.S. based firms to send less capital overseas.

If you actually do the math on this, the size of the effect is unimpressive. Krugman has been banging his drum about this for a while. A few highlights:

If you are attracting foreign investment, then by definition you are increasing the trade deficit. Moreover, your foreign investors will demand a return on their investment, meaning that a good chunk of any GDP growth will leave the country and not be reflected in national income. If you look at the actual mechanisms for how this works, many of the gains are small and could take decades to materialize. Simple models show wage growth, but the effect is significantly weakened if you consider that the US economy is a non-trivial fraction of the overall world economy.

But don’t trust my non-economist’s summary: go read the articles.

And that is a bad thing why?

Fair point: an increase in the trade deficit is not necessarily an economic problem (although Trump certainly seems worked up about it.) That said, as I understand it — and there is a good chance I have missed something — the resulting increase in the value of the dollar plays an important role in the story Krugman lays out in the third link about why any increase in the capital stock would be a very slow process.

I’m not in favor of this bill (or more technically, these bills, since there are still two that have to be reconciled), but I’ll offer the best defense I can think of. There are aspects to the bill that do make sense. Eliminating deductions reduce distortionary effects, and that’s overall a good reform. For example, the home mortgage interest deduction causes the IRS to collect more from a renter than an otherwise identical homeowner. The state-and-local tax deduction causes the IRS to collect more from someone who hires their own recycling service over an otherwise identical person who pays for recycling services through their town’s property taxes. The reduction in those distortionary deductions are a reasonable and good part of this bill. The reduction in rates without an equivalent reduction in spending is dangerous. So fast-forward to 2020 when we’re likely to have democratic majorities, what are they likely to do? I’d wager that they would raise the rates (or even more likely, add in new very high brackets with much higher rates), but not reinstate deductions. So if we take the long view, the tax policy in 2020 might be slightly better than it is today, not solely because of this bill, but taking this bill and the likely response in tandem.

There seem to be two arguments in favor of the bill, the practical and the moral.

The practical argument is as follows:

This can be steelmanned to:

This argument is, broadly speaking, true, but it ignores the crucial fact that the advantage an individual actor’s purchasing power provides for the economy has diminishing returns. The tax bill is aimed at relieving tax burden on actors who already have a great deal of purchasing power, and who in some cases have outright admitted that they don’t need any more and plan on pocketing the money saved and using it for signalling games instead of doing something useful.

The bill won’t have zero positive impact on the economy, but based on the current best available data the positive impact it has on the economy will not outweigh the cost of the bill.

The moral argument goes like this:

This argument is valid, but only if you’re a deontologist.

The bill will also help out certain people immensely in their signalling games, which is probably a big motivator for a lot of its supporters even though nobody wants to admit it.

Eh. It’s only perfect if all of the assumptions of perfect markets are met and some of those are physically impossible. Theory of the second best tells us that sometimes we get closer to the advantages of a perfect market if we have a government that violates more of the assumptions of perfect markets.

Which is to say that in addition to your correct point about diminishing returns and status games, the steelmanning is in some situations also incorrect.

Theory of the Second Best gives us no reason to believe that government intervention will, on average, move the market outcome closer to the optimum rather than farther from it. All it implies is that there are changes that could be made that would do that.

To put the point a little more strongly… . Economics tells us that, to first approximation, the market gives us the perfect result (defined in terms of economic efficiency–I’m ignoring the legitimate criticisms of that criterion, which are ultimately more philosophy than economics). For various familiar reasons that result breaks down in the second approximation, where we allow for externalities and similar problems, which is why there are things government could do that would push the system closer to optimum.

But there is no comparable argument to imply that government, even in a similar first approximation, will produce the perfect outcome. You are choosing between a system where market failure exists but is the exception and one where it is the norm. For more details see …

Lower corporate taxes will mean more investment and less money going into the government. Long term, it will limit the amount of money the government will spend, which will be a good thing depending on how actively destructive you view the government programs the Left would like to spend money on. My own view is that taxes should be if anything higher, with the money going to direct redistribution to the lower and middle classes. But I still see this as a step in the right direction. The government can always tax the money back later if necessary but elimination of the deductions will be more permanent.

Elimination of special interest deductions? LOL not in this country,

https://www.wsj.com/articles/gops-late-changes-to-tax-bill-buoy-key-industries-1512404092

Best I can do is that this is half of a reasonable tax reform bill, and we’ll have to hope the Democrats can pass the second half in 2021. The US has the underlying framework of a reasonable progressive income tax system with rates safely on the good side of the Laffer Curve, and a small library’s worth of special cases tacked on because each and every one of them is good for some small but very interested group of voters. Individually, removing any one of them does harm to the group that has become accustomed to their benefit, and will feel like an attack. Collectively, any real reform will involve getting rid of a whole lot of these special cases. And politically, we aren’t in a place where we can get a bipartisan solution where everybody shares the pain at once.

The GOP is doing its level best to cut out all the special cases that generally favor Democratic constituencies (see e.g. tax-deductible tuition remission for grad students); I trust that if the Democrats can retake the government in 2020 they’ll return the favor. And then we’d need to reduce the baseline tax rates to achieve something close to revenue-neutrality when the deductions and exemptions go away. The GOP has helpfully front-loaded this part for us, as I don’t expect the Democrats to be as big on tax “cuts” as opposed to tax reform.

However, as Scott notes, front-loading the rate cuts makes this a revenue-negative bill and I’m not part of the team that thinks we can just paper that over by printing dollars. So if the Democrats don’t make a clean sweep in 2020, this gets ugly.

As far as I can tell, the tax deduction for graduate students is basically a way for universities to fleece the Federal government (and other granting agencies) and donors. If I understand correctly, the university charges tuition and the department (which is funded by donors and the institutional portion of grants) or the lab budget (grants) remits tuition to graduate students. Removing it will probably force this to change, causing much wailing and gnashing of teeth among university administrators, but perhaps helping more money earmarked for science go to science, not new rock climbing walls?

I was only a graduate student for six weeks, so I’m low confidence on all this though.

The tyler cowen and Scott sumner lines are fairly good.

http://marginalrevolution.com/marginalrevolution/2017/11/new-gop-tax-bill.html

http://econlog.econlib.org/archives/2017/11/better_than_exp.html

In sum, far from ideal, but a few solid steps in the right direction.

One of these guys likes it: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=A9zDDkOPjQA

Interesting argument. Last year I read someone who made nearly the exact opposite argument – they were a Sanders-liberal but declared their vote for Trump because they thought Clinton’s shenanigans would mostly go unnoticed by an apathetic/supportive press while Trump’s would be brightly exposed for all to see… (Is there something going on with varying expectations about the relationship between awareness and effects?)

Has that strategy ever worked out in the entire history of democracy?

It has already worked. Allegations of sexual assault by Trump have led the media to expose other sexual predators. When there were allegations against Bill Clinton the supportive press covered up for him.

You’re stretching. The floodgate moment was the Harvey Weinstein stories coming out; until that happened, Trump had faced as much in the way of consequences as Bill Clinton did. Less, even. Still has.

When the other team does something bad it is easy to admit it is bad. When your team does the same thing it is easy to brush it off. If Hillary had been elected making a big deal about sexual harassment would be providing her enemies a cudgel to use against her and the press would have made less of a deal of it.

Clinton only faced consequences when the legal cases were adjudicated. Trump may face consequences yet.

I’m having a very hard time following exactly how you can possibly credit Trump for The Reckoning, as the cool kids are calling it. Most of the people who’ve fallen are in the left-leaning entertainment industry, not on the right.

When? Is there anything other than pure fantasy and wishful thinking that leads you to say this? We had an accountability moment last year; the verdict came back ‘eh’.

I mean, they weren’t wrong. Trump’s shenanigans have definitely been well-covered by the press. It just didn’t help. A full sketch of the argument would also have to include having a hostile Congress and some sense of shame that makes you not do things when everyone is against them.

It didn’t help because the press didn’t pillory WJC for it, and so lost their ability to aim that particular gun at the other side of the house.

I for one, am willing to give DJT a pass for exactly as many years as WJC was given.

Nothing works like that. People are judged for their misdeeds at the time they come to light, and again, later, maybe, if they’re still in the public eye, viz., Harvey Weinstein but not Roman Polanski being expelled from the Academy. (Previous Reddit thread about the subject.)

Still, an accountability moment may be coming for Bill Clinton; in the same way that Democrats care deeply about the deficit because Republicans pretend to, Democrats will clean their own house because the Republican party now pretends to care deeply about sex crimes while funneling money to Roy Moore, just as Mike Cernovich is really sincerely upset about jokes using the word ‘rape’ enough to get Sam Seder fired over them.

I don’t think anyone on the right gets to high-horse it up over Bill Clinton at this point.

When you say it didn’t help what do you mean? What has actually been passed into law under Trump that shouldn’t have?

Muslim ban?

It’s a seven-country ban that happens to include Muslim-majority countries. It is not immediately based in religion, it originated from a list of countries considered by past administrations.

While I don’t know the numbers, I’m guessing the majority of the world’s Muslims are not from those seven countries.

Say instead that it was a ban on a group of majority-Catholic Central and South American countries that include many drug cartels. Would you call it a Catholic ban, a Central/South American ban, a drug-cartel ban?

The law is almost definitely pointless, but smearing it for what it isn’t is not a good way to discuss it.

You are correct. The countries on the list contain somewhat less than ten percent of the Muslim population of the world.

To be fair, I’d argue that this actually [i]did[/i] happen. The media has historically had a very friendly relationship with most recent presidents, and probably would have had a friendly relationship with Clinton, but it’s developed a strongly adversarial one with Trump. Mostly because Trump went out of his way to antagonize them.

I do question whether this was worth Trump’s shenanigans actually happening, though.

Is that true in general or is Obama an anomaly? I’m too young to remember anything before late Bush-43, but my impression was that Bushes, Reagan, Carter, and Ford did not get very good treatment from the media, and for Clinton is varied* a LOT.

* @Randy M — should this also be “veried a lot”? 😛

It was definitely true in the case of Bush Jr. The media was willing to criticize him in some ways, but it didn’t have nearly the openly antagonistic relationship that it has with Trump, and it was quite happy to, e.g., cheerlead for the Iraq War.

The elite media has a hostile relationship to Trump. The “prole” media, for lack of a better word – i.e. Fox News, National Enquirer, most news outlets owned by Sinclair or by iHeartMedia – is pro-Trump. That is to say, the media that most Americans actually consume on a daily basis is pro-Trump. Network news is probably more anti-Trump, but declining in importance. Trump has learned what Putin, Orban, and Kaczynski already know. Freedom of the press for small circulation outlets that only appeal to high IQ dissidents doesn’t really affect the ability of an authoritarian to rule, and probably reduces the overall level of dissent among the masses by creating the appearance of an internal enemy the ruler can blame for his problems.

If you’re describing Blue Tribe media as “elite” and Red Tribe media as “prole”, you’ve already accepted a number of false Red Tribe assumptions.

The lowest rated network news, CBS, has twice as many viewers as Fox News’s top rated show. Combined the network news shows have 8 times as many viewers as Fox News. The combined subscriptions to the various NY Times modalities are 10 times the circulation of the National Enquirer.

Comparing top shows on CBS to Fox News ignores that Fox News runs news for many more hours per day Over 10 times more hours, I assume.

And if you only count the parts of the news that have a partisan political message or bias, Fox News probably spends at least 100x more time per day than CBS. (10 times as much news programming, and 10 times the density of partisan messaging.)

The error here seems to be considering the press a more important check than Congress.

Sometimes you just can’t predict the simpering cravenness of congress.

I mean, I can’t say it’s a good tax plan, but surely it’s clearly better than Sanders’ college plan. Spending on tulips is equivalent to just burning the money. This money will actually go to people who can spend it on real stuff, capital will get cheaper so there will be an increase in investment, etc. Almost certainly insufficient to cover the cost, but way better than tulips.

Obviously going to college does have *some* real benefit, even if it’s not much, so it’s not entirely tulips.

Especially since Sanders is proposing making *tuition* at *public* colleges/universities free, not entirely paying for people to go to any university. Public schools are already much cheaper than private schools and the tuition isn’t nearly the entire cost. For example, at UMass Amherst, tuition and fees are around $15,000 for in-state students, which is about half the total cost.

Sanders also wants colleges to focus much more on work study programs, which are productive both for the economy and building job skills.

On net? This is not obvious, certainly not generalized across the population.

I have heard very little opposition to this idea, but I’m somewhat against it. First of all, it seems a bit like saying, “Well, if we only require one tulip instead of two, it will cost half a much and all of our problems will be solved!”

More importantly, if you believe at all in the mission of liberal arts, the idea of throwing away the last opportunity to teach most people about the world is a disgrace. And worse, throwing it away in pursuit of the Almighty dollar!

Wait, that’s not what I’ve seen ‘Work-study’ to mean. It just means you have a job while you’re studying. My liberal-arts school had work-study programs, and you had better believe those people were not skipping out on anything.

I never understand how it is possible to believe that government-funded college provision will be better for people than consumer-funded provision. Clearly Sanders had conditions for colleges to focus on work study programmes, but the fact colleges do not do this now is actually significant. Since students select to pay fees, and are not paying fees to support work study programmes at the level that Mr Sanders believes appropriate, then the obvious conclusion (unless we assume widespread elitist mismanagement) is that work study programmes are not actually that popular amongst people wanting to go to College.

If Mr Sanders’ plans were implemented however, then he would be able to insist on more programmes being offered that are not wanted, presumably (because government is not likely to increase funding) at the expense of the programmes currently wanted. It is the central planning fallacy in action, and government funding of college education leaves the whole sector wide open to this sort of thing, or the ever-present threat of not funding ‘non-productive’ programmes.

The work-study programs in this context would be intended to benefit the people who do not currently attend college, because the need to work prevents them. It is only a side-benefit that current attendees would also have more work opportunities.

Fees? What fees do you mean? It is more to do with scheduling both the classes and the work opportunities to be compatible, and also making the work opportunity guaranteed (employer of last resort). Students cannot pay a fee in order to obtain the advantages of this kind of opportunity. There is no fee to pay that guarantees them an employer for the duration of their degree.

I think that the Federal Work-Study Program fills up so that there are more applicants than spots for them. If true then these spots are wanted. If the spots were unwanted and not taken, though, then so what? What is the loss?

You’re going to have to explain this one to me.

Free college helps the following groups:

1. Poor kids who can’t currently afford to go to college: they get to go to college, this makes them earn more money later in life.

2. Middle and upper middle class families who can afford to send their kids to college but not without taking on significant debt or saving a significant portion of their income: they get to spend that money on other stuff.

3. Universities that give out financial aid to help poor and middle class kids attend: they get to redirect that money towards other stuff, like research funding or additions to the medical center or what have you.

Tax cuts for the wealthy/major corporations just go straight into the c-suite hookers and blow budget.

This sort of argument is whybasic economics should be required in schools. Who actually pays the tax depends on economic conditions outside the government’s control, not who nominally gives you the money. CEOs can claim they’ll give themselves bonuses with the tax cut, but they’ll be outcompeted by corporations that invest and attract talent.

Moreover, the corporate income tax is highly distortionary. As Scott Sumner pointed out in a blog post linked in this thread, reducing it does actually cause growth.

Except CEOs have been giving themselves bonuses with tax cuts for decades now and this has conspicuously failed to happen.

Amazon appears to me to spend it’s tax cuts on technology hiring and capital goods. They are notoriously stingy with cash bonus all the way up the ladder upto and including the CEO, who has to sell off slices of his ownership of the company that he founded, to pay for “hookers and blow”, or in his case, funding a space program, underwriting the Clock of the Long Now, and saving a major newspaper from shutting down. His personal “hookers and blow” hobbies appear to consist of getting swol lifting hard and heavy, and spending evenings cooking dinner with his family.

“CEO bonuses” is a red herring. In the books of any large organization, it doesn’t matter to the workers or the shareholders if the CEO pay gets doubled or distributed to the workers/shareholders, because there are so many of the latter.

CEOs are probably overpaid relative to their worth to the company, but arguments to reduce their pay or stop it from going up are just applause lights.

What decades? The corporate tax rate has not been cut since 1988.

This.

Walmart may be an unusual case, but when I recently ran the numbers, I found that if you cut the CEO’s pay to nothing, you’d be able to pay workers approximately $0.01 more per hour… or $10 a year.

This is uh, not the slam dunk people normally treat it like.

I’m not convinced of your three points. I think that college is *way* overblown nowadays, where it seems that almost every job requires it. Free college for all is just going to make this problem worse.

It’s one thing for doctors, engineers, lawyers, scientists, teachers, college professors, etc. to require a college degree. I’m an engineer, for example, use significant portions of what I learned in my college coursework every day and have kept and used many of my textbooks as references. It’s another matter for needing a college degree to be a secretary, where the degree requirement is “whatever”. Do we really need somebody to spend 4 more non-earning years if the coursework isn’t actually on point for the job?

Point 1 seems to be trying to get more people to go to college. There are probably one or two Einsteins out there remaining undiscovered because they just haven’t experienced college, but for the most part, if you want to see what those additional college students would look like: look at the bottom 10% of our college class. It will be more students like this. Even burning the money would be better, because we wouldn’t be humiliating these students.

Point 1 is trying to get more people who currently can’t go to college because they can’t afford it to go to college, not trying to get more people who currently can’t go to college because they’re too stupid to go to college.

Cities that have implemented free college programs (like Kalamazoo MI) seem to think it’s had a positive effect on high school performance as well, since if college is an attainable goal for poor kids they’ll be more likely to get their act together in high school.

What’s the dropout rate for kids from the Kalamazoo Promise?

Not appreciably higher than for demographically similar students from elsewhere in the state, and test scores, high school graduation rates, and college graduation rates have been steadily improving since the program was implemented.

You meant to say “50%.”

Yeah, which is not not appreciably higher than demographically similar student from elsewhere in the state, so the Promise does not appear to be encouraging idiots who have no interest in going to college to go to college just because it’s free – those people are already going to college and flunking out because there’s tremendous social pressure to go to college. And a student who flunks/drops out of college doesn’t cost the Promise anything going forward, so it’s not like they’re living the high life for four years: if anything, the Promise is allowing kids to try out college for a year to see if it’s right for them without taking on debt, which seems like an unalloyed public good.

Worth mentioning for some of those (Like Doctors and Lawyers) requiring an undergraduate degree is exactly as pointless as the secretary, which I think was explicitly pointed out in Scott’s tulip subsidies post.

Yeah, but this is an argument that law degrees and medical degrees should be undergraduate degrees in the first place

College has benefits certainly, the problem is that the benefits aren’t as much a slam dunk as they used to be due to rising costs, and adding more subsidies to the “tulips” will probably just raise the cost more. That is, we agree that college is unaffordable, but the argument should be over why it costs so much, not who should foot the ludicrous bill.

Lower corporate taxes will certainly have benefits beyond hookers and blow (hey, hookers and drug dealers need income too). Much of the money will probably go to increased wages or capital investment. Or it will go to the shareholders and be taxed as capital gains anyway. It doesn’t disappear into the ether.

The question is, as always, whether those benefits will be worth the reduced budget / increased taxes elsewhere.

But we’re arguing about relative cost-benefit. Neither option is “no benefit at all”.

The closest comparison to Bernie’s free college proposal is probably Scotland’s free college system, where universities have to agree to limit their underlying tuition rates to x + inflation for the government to pick up the tab for their students. You’re not going to see much tulip speculation in that sort of a setup, because universities can’t actually raise their tuition rates at will without jeopardizing their stream of free government money

…or raise their fees to reflect rising costs, which inevitably are rising at a higher than inflation rate.

They can’t raise their fees above inflation or they lose their government money.

Correct me if I’m wrong, but isn’t the very reason American college are so expensive that they get subsidies in the first place?

Like, the more the government pays for college, the more colleges can drive up their prices without loosing customers since students have no incentive to look for cheap colleges since they know the government is the one paying the price?

For some reason, when either college or health care comes up, this point is lost on most. (though it’s discussed a lot here).

Subsidies without caps will do that.

Burning the money would be better than Sanders’ college plan. When money is burned, nothing is wasted. It simply increases the value of the remaining money proportionally.

Using money for unproductive purposes is worse than burning it, since this wastes real, scarce resources.

Sending people to college is no more an unproductive purpose than sending people to high school, and we’ve already decided that sending people to high school is a productive use of our resources.

That’s not entirely fair. Obviously making everyone in the US get a PhD wouldn’t be a good idea, so there has to be a cut-off at some point. Now, where that cut-off is, I’m not sure, but you can’t just state for certain that it’s not at the end of highschool.

Surely the cut-off should be based on academic standards, not on ability to pay.

Nobody I’ve seen is proposing college for people of every IQ, only college for people of every income level.

We decided incorrectly. And its becomes more incorrect each year, and importantly, its becoming apparent that it was incorrect to more people each year.

My first major step into the Red Pill was discovering what had happened to high schools since I had graduated.

I may regret asking this, but what happened to high schools after you graduated?

His political enemies obtained increased cultural significance of course.

The fact that we’ve decided to send kids to high school doesn’t magically make it productive to do so. We decide to do unproductive things all the time.

It’s not a solid argument, since different amounts (and directions!) of education are optimal for different career paths of people.

The first year of schooling is useful/needed/economically worthwhile for almost everyone, the twentieth year of schooling is useful/needed/economically worthwhile only for a small fraction of the population. The society benefits if almost everyone is able to read; the society doesn’t particularly benefit if everyone gets a tertiary degree instead of becoming productive as soon as they’ve reached the schooling level they need; above that level more people spending more years in college is an expensive hobby that’s great and useful for self-improvement if you can afford it, but has no reason to be subsidized by others.

At what marginal year of education spend does the average person not see enough lifetime salary increase to make the tuition cost worthwhile?

It’s definitely not senior year of high school.

Currently ~35% of US adults go to college. A noticeable portion of them (mostly depending on the major) *already* have a negative lifetime salary effect by this choice, and if we’re talking about the average (I’m assuming median) person, then we’re talking about what would be the marginal student if college enrollment increased by half – and yes, I do assume that for them the optimum point would likely be the senior year of high school (or possibly two years of trade school after that), it’d be reasonable to expect that *in aggregate* getting four years head start in a job or apprenticeship would get them a lifetime salary increase over spending those four years on a college degree that’s essentially irrelevant for their career.

It’s worth noting that this is a “tragedy of commons” situation – when facing that choice individually, any one of them could gain some extra benefit by having those credentials, but when looking at the effects of such choice, it’s a zero sum game – their competitors will also have the same credentials, so there’s no benefit, but all of them have spent four years on that.

Also note that simply comparing the lifetime salary of college graduates and non-graduates is *highly* misleading, since what we’d want is comparing the lifetime salary of college / non-college of people *with the same innate qualities*, everything from conscientiousness and intelligence to socioeconomic status. You can’t compare someone who graduated a good school with someone who didn’t attend any; you need to compare them with someone who was accepted to the same school but didn’t join for financial reasons, and also had the qualities and conditions necessary to graduate.

Again, all kinds of factors count – in addition to the obvious issues of high school education quality and general intelligence, the simple measure of college/noncollege cohort income also “counts” the effect of socioeconomic status. Yes, someone who drops out because they were raising a child as a single parent or because they couldn’t combine studies with a day job they needed to feed themselves is going to have a much lower lifetime income than a successful graduate – but they’re also going to have a much lower lifetime income *anyway*, even if college admission is free and equal, since they have all these other difficulties to fight through; you can’t just assume that if they receive free tuition then their lifetime income is going to jump to the level of currently successful graduates, it won’t happen more often than not.

This is the right question for the individual, but the wrong question for society; if education is mostly a positional good (for instance, if the signaling theory of education is mostly right), then the social effects will be negative long before the individual effect.

@jonathanpaulson

It’s even worse if it’s only partially a positional good. Say every dollar spent on post-highschool education produces 50 cents worth of benefit in terms of better skills leading to greater productivity. If half the cost is subsidized, then it not just in the self interest of every person in society to get as much education as possible, it’s in the self interest of every employer to hire the most overeducated people they can find. If education is purely signalling/positional, some natural contrarians can defect, not lose much, and hope to inspire others. If education does produce some value, but less than it costs to get, then the trap gets much stickier.

Do we really need government supplied day care for the 17-26 yo cohort now as well?

If 17-26 year olds who go to four years of daycare have significantly higher earnings over the course of their lives than 17-26 year olds who don’t go to four years of daycare – yeah, probably the government should supply that good.

Yeah, I’ve seen the numbers on lifetime earnings vs. tuition cost too; I could hardly have avoided them, they were literally posted on the walls in my high school.

Thing is, those numbers are hopelessly corrupt. It’s not just the usual correlation/causation issue, either, although that is an issue; there’s a deeper question of whether whatever real difference in earnings remains after that is driven by employers using college as a proxy for intelligence/conscientiousness, which you can’t avoid weakening if you make college more ubiquitous. Or, worse, as a proxy for pure social status.

To the extent that college provides productive skills, subsidizing it could be worthwhile. But I don’t know that extent (though I suspect it’s small), and neither do you. And subsidizing credentialism is a spectacularly bad idea.

Do we really need government supplied day care for the 17-26 yo cohort now as well?

That demographic group — well, the male part of it — commits most of the crime, so that’s a good argument for babysitting them.

Supply and Demand, I’d like to introduce you to Qays, Qays, Supply and Demand. You two have a lot to talk about.

Or, politely, it seems to me that if more people go to college, the the relative value of a degree will fall. If everyone goes to college, it will fall to the level equal to the average (or perhaps the lowest point) of the knowledge and skills picked up there. I don’t think that is anywhere near the amount of money that will be spent for it, especially with the price inflation that will come.

Is it too early to get into the spirit of the season?

Are there no prisons? Are there no workhouses?

@Nornagest

Making college free only weakens its utility as a proxy for intelligence/conscientiousness if you simultaneously make it easier to graduate from.

Make college free absolutely weakens its utility as a proxy for pure social status, but that’s a good thing.

If anything, free + rigorous college = college that’s actually more useful as a proxy for intelligence/conscientiousness than it is today, while simultaneously less useful as a proxy for social status.

False. If college is expensive, choosing to start it means you were smart and dedicated enough to get a scholarship, hard-working enough to pay for it yourself, serious enough about it to mortgage your future for it, or rich and connected enough for Daddy’s money to pay for it. All four are correlates of intelligence and conscientiousness, more or less in that order of strength. If college is free, choosing to start it just means you chose to start it.

I don’t think its actual academic difficulty has much to do with its signaling value at all.

@Nornagest

College is expensive, to the point that it’s financed almost exclusively by 1) rich parents 2) debt and 3) need-based financial aid, in that order. The only rung of the university system that it’s feasible for a student to pay their way through is community college. Merit-based aid has no effect at determining whether poor students can go to college or not, since any student smart enough to be getting merit-based aid at a school that doesn’t guarantee to meet financial need could simply have gone to a school that meets financial need in the first place.

If college is free, choosing to start it just means that you chose to start it, yes. But finishing college means you were capable of finishing college, which is a strong signal for intelligence/conscientiousness.

At present the actual academic difficulty of college is a relatively minor part of its signaling value because college is just as much about signaling family wealth as it is signaling intelligence. But if college is no longer about signaling family wealth (since it’s free), all that it will signal will be intelligence.

That’s basically just a restatement of your last post, so I guess all I can say at this point is that I disagree for reasons already given.

Nornagest, you stated that signalling structure IS something. Qays said it would HAVE TO BECOME something. You did not provide any reasons against this reasoning.

Mainly I was just interested in showing that the oft-cited numbers about college graduates’ earnings are bogus — or, to put it more politely, not germane to a debate about whether we should be funding college education.

I guess I got off in the weeds a little with the signaling discussion there, but if we’re talking about a hypothetical future in which graduating college is a pure signal of intelligence, then we’ve already left those earnings numbers far behind. I think I’m much less sanguine about what a college education represents than Qays is, but that’s really beside the point.

@Qualys

What incentive is there to keep colleges as rigorous as it is now? Grade inflation has been a problem for decades, and it will only get worse if colleges accept more students. Colleges and professors have strong incentives to keep students happy so that more will apply and the professor makes tenure, and failing students does not help that. Likely the grade distribution will remian where it is, if not inflate further, while the couse rigor decreases to the level of the bottom student.

@Qays

The disconnect between what you’re saying and what some commenters here are saying is due to the relationship between college credentials and economic success. (or measurable success defined some other way)

Most people here subscribe to the view that education is a positional good which signals some combination of a person’s intelligence, conscientiousness, and social networking/clout. In other words, having certain traits makes you more likely to attend university rather than the other way around.

Increasing the number of people that attend university through one financial mechanism or another does not, therefore, produce individuals of the same caliber as existed prior to the change. It simply dilutes the job market signal

This is why pointing to the increased earnings of college graduates is meaningless. Just as pointing to the increased earnings of people that drive sports cars is meaningless.

Aside: if there are high IQ people born into poor families that would benefit from having their abilities known to universities and employers, a program of the kind described could conceivably help them. However, most people that are classified as impoverished that are capable of doing college level work qualify for full or partial scholarships [both from the feds and from many prominent universities] So any further boosting of enrollment is likely superfluous.

This model predicts the observed outcomes of college graduates in relation to the labor market:

1. College material becomes watered down to accommodate less academically gifted individuals

2. Jobs now require college degrees that previously didn’t (Because not only is the average college graduate less gifted but so is the average HS graduate)

3. More people are compelled to take post-graduate degrees in order to distinguish themselves. Which can be financially ruinous for people who are too rich to qualify for full scholarships but too poor not to need them.

For more information I recommend SSC’s ‘Against Tulip Subsidies’ and/or Bryan Caplan’s lecture ‘The case against education’

@aristides

Colleges currently have an incentive to attract rich students because they’re the ones whose families can afford to pay full freight. This means colleges have an incentive to cater to rich students, which means there’s an incentive not to flunk students, since if your school gets a reputation for being too rigorous you’ll have trouble attracting the most profitable class of students (look at what’s been happening with UChicago, which has been trying very hard to shed its old reputation of academic rigor in order to attract “normal Ivy+ applicants”).

If college is free (that is to say, paid for by the government) universities will have no incentive to prioritize rich students over any other sort of student. Flunking a student out won’t matter, since that student will just be replaced by another student of equal economic value to the school at the start of the next academic year. Acquiring a reputation as a tough school won’t actually be bad for a college’s bottom line, which means grade inflation will decrease. It’s telling that grade inflation is more of a problem in the US, where colleges compete to attract wealthy students, than it is in countries where college is free or heavily subsidized (Canada, Germany, the UK, etc), where colleges compete to attract intelligent students.

@RalMirrorAd

Having certain traits makes you more likely to attend college if you have the money to attend college in the first place. Many students have the personality traits that would incline them to attend college but cannot attend college due to lack of funds. Many other students do not have the personality traits that would incline them to attend college but would be more likely to acquire those traits in high school if college were a financially realistic goal for them to strive towards.

Saying that most people who are impoverished but capable of doing college level work qualify for full scholarships is ludicrous, and partial scholarships don’t help much if you’re impoverished. There are only a few score universities in the entire country that guarantee to meet financial need for all applicants, and these schools are extremely difficult to get into. Poor students generally do not have the time or the mentoring necessary to chase down all the hidden merit scholarships at schools that don’t guarantee to meet financial need, and there are plenty of poorer students who are smart enough to do college level work but not smart enough to qualify for merit scholarships. And then there are all the poor students who do manage to go to college but wind up heavily indebted and unable to have kids/buy a house/start a business/etc for a decade afterwards. Financial barriers to higher education are huge.