I.

From Vox: Solving The Mystery Of The Internet’s Most Beloved And Notorious Fanfic. The fanfic is “My Immortal”, a Harry Potter story so famous that it has its own Wikipedia page, and articles about it in Slate, Buzzfeed, and The Guardian.

It’s famous for being really, really bad. Spectacularly bad. Worse than it should be possible for anything to be. You wouldn’t think you could get The Guardian to write an article about how bad your fanfiction was, but here we are. Everyone agrees that it must have taken a genius to make something so awful, but until recently nobody knew who had authored the pseudonymous work. The Vox article investigates and finds it was probably small-time author Theresa Christodoupolos, who goes by the pen name Rose Christo.

But this leaves other mysteries unresolved. Like: what is going on with it? Its plot makes little sense – characters appear, disappear, change names, and merge into one another with no particular pattern. Even its language is fluid, somewhere between misspelled English and a gibberish that can at best produce associations suggestive of English words.

All these features are unusual in a modern fanfiction. But they’re typical of alchemical texts, which are usually written in a layer of dense allegory. Might this shed more light on My Immortal? After spending way too long investigating this, I find strong evidence in favor. My Immortal is a description of the Great Work of alchemy. Its otherwise-inscrutable symbolism is a combination of three traditions: the medieval opus, the 17th century Rosicrucians, and the native German traditions encoded in Goethe’s Faust. We’ll start by going over these traditions, then delve into the text to unveil the hidden meaning.

First Source: The Medieval Opus

Medieval alchemy centered around the Great Work, or magnum opus, of creating the Philosopher’s Stone. The Stone is supposedly a substance that can transmute lead into gold and grant immortality. But scholars since Jung have also interpreted the opus symbolically, as a process of spiritual transformation. In this reading, the chemical processes are a metaphor for psychological processes, and the creation of the Stone represents the discovery of the true Self, similar to the Christian gnosis or Buddhist enlightenment. Descriptions of the opus tend to describe it as taking place in a series of stages, usually three: nigredo (blackness), albedo (whiteness), and rubedo (redness).

In the first stage (nigredo, “blackness”), you start with some kind of base matter. In the chemical allegory, this is usually lead. In the psychological version, this is the normal mental state, with all of its hangups and uncertainties. The seeker at this stage is symbolized by the raven, blackest of animals. He (the medieval system assumes a male seeker) must begin by confronting his unconscious mind, which takes the form of a dragon. The unconscious is full of bizarre and shameful repressed material, and the seeker’s instinct is to run away. Instead, he must slay the dragon, at which point the dragon rises again as an ally. The seeker then unites with the unconscious in the first “chemical wedding”, ending in a sudden revelation of blinding whiteness – the second stage of the Work.

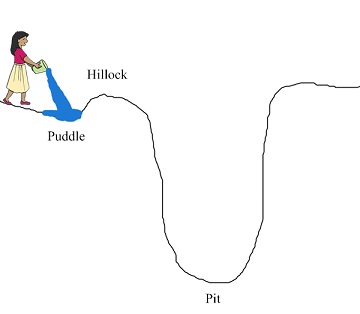

In the second stage (albedo, “whiteness”), the base matter must be cleansed of its impurities. The seeker is analogized to a child in a baptismal font, or bathing in a stream, or [any of several other water metaphors]. Eventually it begins to shine with its own inner silvery-white light. When the dross has been cleared away, the seeker encounters a second representation of his feminine principle. He unites with the feminine principle in the second “chemical wedding”, and finally see his True Self as it really is.

In the third stage (rubedo, “redness”), the seeker has already discovered his True Self as a sort of distant guiding star, but has yet to relate it to the rest of his life or the everyday world. The otherworldy True Self must be united with the seeker’s worldly personality in the final and greatest alchemical wedding, often called the Marriage of the Sun and Moon, or the Marriage of the King and Queen, or [several other flowery metaphors], which joins all opposites into a final cataclysmic union – the Philosopher’s Stone. When this stage ends, the seeker is once again an ordinary person interacting with the ordinary earthly world, but now in a way fully integrated with his true Self. In some traditions, the work is cyclic, and the seeker begins again at the nigredo stage.

Some of this is already in canonical Harry Potter – the first book in the series was originally called Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone, and Rowling included a few alchemical “easter eggs”. In particular, she includes characters named after two of the three stages: Albus Dumbledore (= albedo) and Rubeus Hagrid (= rubedo). There is no character representing the blackness stage, probably because calling somebody “Nigerus” would be Problematic.

In order to turn Rowling’s half-assed name-dropping into a true alchemical allegory, My Immortal has to introduce the missing character with a blackness-themed name. Accordingly, its first sentence starts “Hi my name is Ebony Dark’ness Dementia Raven Way”.

Second Source: The Rosicrucian Writings

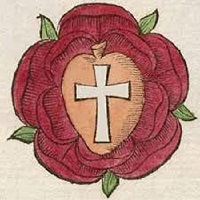

These were a series of anonymous pamphlets that took Germany by storm in the early 17th century. They purported to reveal the existence of a secret brotherhood of alchemists, the Rosicrucians, who had discovered vast mystical secrets and were going to disclose them any day now. According to the pamphlets, they had been founded by a hero-sage, Christian Rosenkreutz, who had traveled the world seeking wisdom. But Rosenkreutz was a bit too allegorical for anyone to think he was a real person. His last name was German for “Rosy Cross”, referring to a long tradition of alchemical symbolism in which one produced the Stone by uniting the Rose (the feminine? the spirit? the consciousness?) and the Cross (the masculine? the material world? the body?). The symbolism was a bit unclear, but it caught on, and soon all sorts of mystical groups were using a rose cross as their logo and claiming to be Rosicrucian-inspired.

The most famous Rosicrucian work was The Chymical Wedding Of Christian Rosenkreutz, which purports to be a story about Rosenkreutz getting an invitation to go to a castle for a wedding. But this is just the frame story for throwing a metric ton of inscrutable symbolism at the reader, as Christian successively encounters candle-lighting virgins, golden scales, white serpents, and a bunch of gates and towers. Everybody assumed there were deep mystical secrets contained in this, probably related to the alchemical wedding necessary to achieve the Philosopher’s Stone.

My Immortal wears its Rosicrucian themes on its sleeve. Most obviously, its author uses the not-exactly-subtle pen name “Rose Christo”. But also, the third sentence of the introduction is just “MCR ROX!” A quick check at the My Immortal Wiki tells us that MCR is supposed to be an abbreviation for “My Chemical Romance”.

I maintain that if you are writing a fanfiction of a book about the Philosopher’s Stone, and you use the pen name “Rose Christo”, and you reference a “chemical romance” in the third sentence, you know exactly what you are doing. You are not even being subtle. My Immortal is in part a modern retelling of The Chymical Wedding of Christian Rosenkreutz.

Third Source: Goethe’s Faust II

You know the story. A great alchemist, frustrated by the limitations of his mortal faculties, makes a deal with the Devil. The Devil will give the alchemist anything he desires. In exchange, if the alchemist ever knows a single moment of perfect happiness, he will die and the Devil will get his soul. Maybe you even know the followup: he covets an innocent maiden, Gretchen, and with the help of the Devil he gradually corrupts her until she chooses death over a life of sin.

All that is Faust Part I. Later in life, Goethe wrote the much weirder Faust Part II. A German scholar assures me that “nobody has any idea what it’s about”, except that it is definitely an alchemical metaphor in some way.

A brief synopsis: Faust, thanks to his pact with the Devil, has now become a powerful sorcerer and respected statesman. He decides that a cool thing to do would be to marry Helen of Troy (here called by her German name “Helena”) the most beautiful woman in history. The Devil (with the help of the Sibyl) helps him time-travel back to ancient Greece, where he meets Helena, seduces her, and brings her back to his own time. They have a child together, but the child dies, and in grief Helena departs Faust for the Greek underworld. Faust devotes himself to a different project – raising a new country out of the sea, which he will govern. The country-raising goes really well, and looking upon his new territory, Faust accidentally feels a single moment of perfect happiness. He dies, and the Devil takes his soul and drags him to Hell. Then a choir of angels show up and distract the Devil. While he is distracted, they carry Faust up to Heaven. There he meets all the women in his life – eg Gretchen and Helena – as well as the Virgin Mary. All of them are revealed to be aspects of the Eternal Feminine within himself (or something), and by recognizing this, he is redeemed and found worthy of salvation. The end.

My Immortal is full of symbolic wordplay (for example, did you catch that “MCR ROX” references not just the Chemical Wedding but also its end result, the Stone?) When it mentions that a character is Goth, or seems Goth, or does something in a Goth way, this is often a visual pun (Goth = Goethe) telling us that the scene has a parallel in Faust. We’ll go over some examples later.

Overall Structure

The canonical version of My Immortal is separated into two books of 22 chapters each. In occultism, 22 is the number of completion, especially in Kabbalah (where there are 22 letters of the Hebrew alphabet, 22 generations from Adam to Israel, and 22 paths on the Tree of Life), and Tarot (where there are 22 Major Arcana). So we can think of the book, like the Opus, as a double-traversal of the Tree of Life – first going up from Earth to Heaven, then returning to Earth again.

The medieval and Rosicrucian themes are mostly concentrated in the first half of the text, and consist of a series of thwarted traversals of the alchemical path. At the end of Part 1, a final successful traversal is completed. In Part 2, we segue to a scene-by-scene identity with Part 2 of Faust. More specifically:

Chapter 1 – 5: Alchemical Path 1, nigredo, albedo. Purification fails, seeker sinks back into prima materia.

Chapters 6 – 18: Alchemical Path 2, nigredo, albedo, partial rubedo. Second alchemical wedding fails, seeker sinks back into prima materia

Chapters 18 – 22: Alchemical Path 3, nigredo, albedo, rubedo. Second alchemical wedding partly completed, seeker remains in limbo state.

Chapters 22 – 39: Equivalent to Faust, Act II, Scene 3.

Chapters 40 – 44. Equivalent to Faust, Act II, Scene 5. Third alchemical wedding succeeds, Stone attained.

I realize these are very odd claims, so I want to demonstrate the flow of symbolism in each of these and compare it to that used in more traditional alchemical texts.

II.

Chapters 1 – 5: First Path

In his papers on alchemy, Carl Jung writes “Great importance was attached to the blackness as the starting point of the Work”. The first sentence of My Immortal begins “Hi my name is Ebony Dark’ness Dementia Raven Way”.

But Ebony’s name isn’t just blackness. It’s a combination of all the different symbols of the nigredo stage. Let’s look at the rest of the Jung quote:

Great importance was attached to the blackness as the starting point of the Work. Generally it was called the “Raven”. In our context the interpretation of the nigredo as terra (earth) is significant. Like the anima media natura or Wisdom, earth is in principle feminine. It is the earth which, in Genesis, appeared out of the waters, but it is also the terra damnata.

I’ve bolded the relevant points. Unlike the albedo and rubedo characters, the nigredo character must be feminine. Her name references the Raven. More speculatively, damnata = Dementia? I think plausibly true. Her name is just a bunch of nigredo symbols strung together.

The nigredo stage begins with a black substance (sometimes identified with lead, the starting point for the transmutation) being placed in a vessel called “the coffin”. From Landauer & Barnes (2011):

The alchemists used a number of different vessels in their work and these vessels – variously known as alembic, coffin, egg, sphere, prison, and womb – particular to stages in the alchemical process. During the blackness of the putrefying Mortificatio, the vessel was represented as a coffin or prison

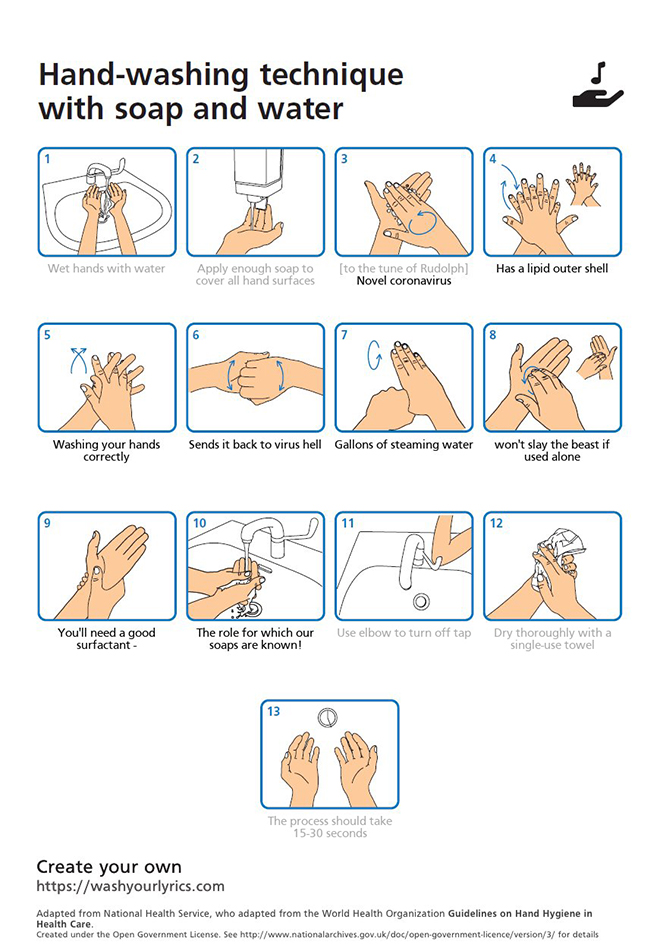

Each of the three paths in Part I of My Immortal begins with Ebony waking up in a coffin. For example Chapter 2: “I got out of my coffin and took of my giant MCR t-shirt which I used for pajamas”. Remember, MCR means “my chemical romance” and when it appears it usually tells us that we are getting an alchemical analogy.

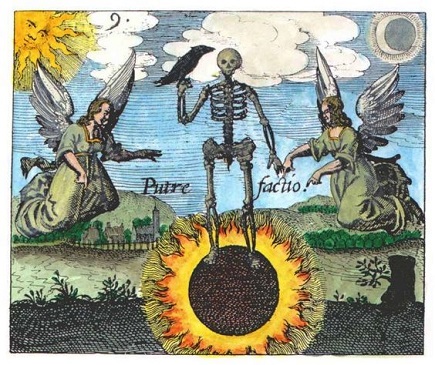

The black substance in the coffin must then undergo a series of reactions, usually symbolized as interactions between a raven and dragon. Sometimes the raven and dragon are the same entity; other times they are different entities that must confront each other and unite. For example, from the Aurelia Occultae Philosophorum:

I am an infirm and weak old man, surnamed the dragon; therefore am I shut up in a cave, that I may become ransomed by the kingly crown. A fiery sword inflicts great torments on me; death makes weak my flesh and bones. My soul and my spirit depart; a terrible poison, I am likened to the black raven, for that is the wages of sin.

In Jung’s more psychological version, the raven is the seeker and the dragon is the seeker’s unconscious mind. The seeker must begin by confronting his unconscious and all the repressed material therein.

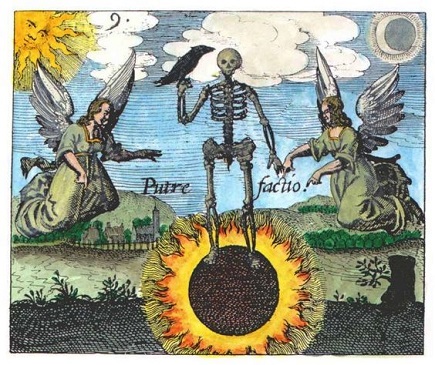

A typical alchemical illustration with raven and dragon. This one isn’t going so well for the raven.

In the first chapter of My Immortal, a raven-named character meets a dragon-named character:

“Hey Ebony!” shouted a voice. I looked up. It was…. Draco Malfoy!

“What’s up Draco?” I asked.

“Nothing.” he said shyly.

But then, I heard my friends call me and I had to go away.

The encounter with the unconscious begins the process of mortificatio. This is cognate with the English word “mortify”, and with good reason – the unconscious is full of all of our deepest and most shameful repressed desires. Herzer and Gillabel describe it like so:

In alchemy the dragon corresponds closely with what Jung called the Shadow. The Shadow is the name for a collection of characteristics and impulses which could be conscious, but which are denied. At the same time we recognize and see them in other people. Some examples of the Shadow are: egotism, laziness, intrigues, unreal fantasies, indifference, or being obsessed by money and possessions. The Shadow is the inferior being in us that desires what we do not allow ourselves because it is uncivilized, because it is incompatible with society’s rules and with the image of our ideal personality. It is all that what we are ashamed of.

When Ebony encounters Draco, she feels shame:

“OMFG, I saw you talking to Draco Malfoy yesterday!” [Willow] said excitedly.

“Yeah? So?” I said, blushing.

“Do you like Draco?” she asked as we went out of the Slytherin common room and into the Great Hall.

“No I so fucking don’t!” I shouted.

“Yeah right!” she exclaimed.

The work of the nigredo stage is to transmute this shame into acceptance and even love. Some sources describe this as slaying the dragon – but after being slain, the dragon rises again in a perfected form. Once the seeker is fully comfortable with their dragon, self and unconscious unite in the first alchemical wedding.

Just then, Draco walked up to me.

“Hi.” he said.

“Hi.” I replied flirtily.

“Guess what.” he said.

“What?” I asked.

“Well, Good Charlotte are having a concert in Hogsmeade.” he told me.

“Oh. My. Fucking. God!” I screamed. I love GC. They are my favorite band, besides MCR.

“Well…. do you want to go with me?” he asked.

I gasped.

Draco invites Ebony on a date, where they will see a band Ebony compares to My Chemical Romance. In general, concert dates in My Immortal represent alchemical weddings. This particular concert is the wedding at the end of the first stage. We know this because the story describes Ebony’s clothing in detail at several points, and it is always some combination of black, white, and red. The particular colors at any given time indicate the stage of the Work being represented. In this case, when dressing up for the concert, Ebony says:”I painted my nails black and put on TONS of black eyeliner. Then I put on some black lipstick.” The only color is black – so she is still entirely in the nigredo stage.

At the end of the concert/date/wedding, Draco and Ebony go to the Forbidden Forest and have sex, representing the union of Ebony and her unconscious. This signals the end of the nigredo stage and the beginning of albedo.

Then he put his thingie into my you-know-what and we did it for the first time.

“Oh! Oh! Oh! ” I screamed. I was beginning to get an orgasm. We started to kiss everywhere and my pale body became all warm. And then….

“WHAT THE HELL ARE YOU DOING YOU MOTHERFUKERS!”

It was…………………………………………………….Dumbledore!

Almost all descriptions of the beginning of albedo emphasize its suddenness. Jung writes that “the nigredo gives way to the albedo…the ever deepening descent into the unconscious suddenly becomes illumination from above”. Remember that Albus Dumbledore is the Harry Potter character representing albedo, even as Ebony represents nigredo. So as Ebony has sex with Draco (deepening descent into the unconscious), suddenly she sees Dumbledore standing over her.

The part where the seeker has sex with the dragon is canon.

But there are signs that the transition is not complete. Dumbledore interrupts her before she can have an orgasm; the union has been only partially consummated. And there are 21 marks between “was” and “Dumbledore” (20 ellipses plus one lone period), which is one short of 22, the mystical number of completion.

As we will see later, Ebony skipped a step – she did not kill the dragon before uniting with it. Therefore, the purification of the albedo appears as the hostile interference of a superego perceived as alien, rather than as a deliberate cleansing from within. Dumbledore admonishes Ebony for her disgusting sexual act and forces her and Draco to separate, ending the path.

Chapter 6 begins “The next day I woke up in my coffin. I put on a black miniskirt that was all ripped around the end and a matching top.” Ebony is back in the coffin, dressed in all black. She has returned to the very beginning of the Work.

Chapters 6 – 18: Second Path

In this section, Ebony retraces her steps. She meets Draco again. They have sex again. But this time, Ebony learns that Draco is in love with Harry Potter (nicknamed “Vampire” in this work), and breaks up with him angrily. This causes Draco to commit suicide – she has slain the dragon. Later, she learns that Draco has inexplicably come back to life (as the alchemical symbolism insists must happen) and is being held hostage in Voldemort’s lair. Recall again the description from Aurelia Occultae Philosophorum: “I am an infirm and weak old man, surnamed the dragon; therefore am I shut up in a cave, that I may become ransomed by the kingly crown”. She rescues Draco and has sex with him again. The path has been completed in full.

But she actually reaches the albedo stage earlier than that – at the moment Draco dies. Let’s go through the symbolism piece by piece:

We practiced for one more hour. Then suddenly Dumbeldore walked in angrily! His eyes were all fiery and I knew this time it wasn’t cause he had a headache.

“What have you done!” He started to cry wisely. (c dats basically nut swering and dis time he wuz relly upset n u wil c y) “Ebony Draco has been found in his room. He committed suicide by slitting his wrists.” […]

I started crying tears of blood and then I slit both of my wrists. They got all over my clothes so I took them off and jumped into the bath angrily while I put on a Linkin Park song at full volume. […]

I got out of the bathtub and put on a black low-cut dress with lace all over it sandly.

Dumbledore appears, again “suddenly”. He gives her the news of Draco’s death. Then Ebony slits her wrists. Compare to Hamilton’s The Alchemical Process Of Transformation:

Completion of the first stage is now experienced as a death, which is in fact a complete letting go of the old sense of self that was identified unconsciously with the earth nature. Images of fire and burning often accompany the images of death and endings. Now we are ready to enter the second stage.

Did you catch how Dumbledore’s “eyes were all fiery”?

Just as the nigredo stage should begin in a coffin, so the albedo stage should begin in a baptismal font. But a bathtub is a perfectly serviceable replacement – in fact, a raven in a bathtub is the same image used in this part of The Chymical Wedding Of Christian Rosenkreutz. A magic egg hatches a black bird, and then:

A bath colored with fine white powder had been prepared for the bird, which enjoyed bathing in it until the lamps placed beneath the bath caused the water to become uncomfortably warm. When the heat had removed all the bird’s feathers it was taken out.

When Ebony gets out of the bath, she puts on a “dress with lace all over it” – the lace is presumably white, so the dress is black-and-white, signifying that she has now attained both the nigredo and the albedo stages. Her current task in the Work is to purify herself, see through the falsehoods of the ego, and behold her true Self.

Ebony notices that Professors Snape and Lupin have been videotaping her naked in the bath. She accuses them of pedophilia and then “I took my gun and shot Snape and Loopin a gazillion times and they both started screaming and the camera broke.” This is the purification and the confrontation with the ego. The ego is analogized to a voyeur with a camera, recording everything we do, showing us our own nakedness. Ebony shoots the camera and breaks it. Compare to Dogen’s analogy of enlightenment to breaking a mirror.

Ebony’s next step should be a second alchemical wedding, this time with her animus.

The medieval alchemists (writing for their male readers) spoke of the anima figure, the feminine archetype within every man. The anima can appear as a hideous old hag, but if accepted, turns into a supernaturally beautiful young woman, the intended bride of the second alchemical wedding. Jung adds that every woman has an equivalent animus, the male archetype. Presumably he too starts out appearing ugly, but if accepted he transforms into a handsome young man.

Ebony’s dual animus is Hagrid on the one side, and Harry “Vampire” Potter on the other. She constantly conflates these two characters in bizarre ways; we readers are supposed to understand that they represent different facets of the same archetype, which Ebony cannot integrate. For example, when Harry comes in in Chapter 12, Ebony says “I THOUGHT IT WAS HAIRgrid but it was Vampire.” Later, she will constantly refer to them by a combined names like “Hairgrid”, “Hargrid”, or even “Hahrid”.

Ebony externalizes the negative aspects of her animus as Hagrid (note the “Hag”, which she cannot bring herself to say), canonically the ugliest person at Hogwarts. Hagrid is everything she hates: prep, not Goth, and “fucked up”. She externalizes the alluring aspects as Harry, canonically rich, famous, and attractive. Ever since Twilight, the archetypal animus figure – the alluring, supernaturally beautiful, mysterious male – has been the vampire, so Harry becomes “Harry ‘Vampire’ Potter”.

There’s more. In My Immortal, Harry has a pentagram-shaped scar. The pentagram is an alchemical symbol, but there’s some evidence that it’s not what’s really involved here. Earlier in the story, Ebony describes Draco as “wearing white foundation and messy eyeliner kind of like a pentagram (geddit) between Joel Madden and Gerard Way.” Later she uses the same device: “My voice sounded lik a pentagram betwen Amy Lee and a gurl version of Gerard Woy”. I think we are supposed to infer that, as a Satanist, she is uncomfortable with naming the Christian symbol (the cross) and so replaces it with a Satanist symbol (the pentagram). So plausibly Harry has a cross-shaped scar.

This is significant because a few paragraphs later, when Ebony is in the hospital after her wrist-slitting injury, Hagrid comes and offers Ebony a bouquet of roses. Harry (the cross-bearer) is the same person as Hagrid (the rose-bearer). Ebony needs to recognize them as different aspects of the same animus, the united Rosy Cross, so she can behold her True Self. Let’s see how she does:

Hargrid came into my hospital bed holding a bouquet of pink roses.

“Enoby I need to tell u somethnig.” he said in a v. serious voice, giving me the roses.

“Fuck off.” I told him. “You know I fucking hate the color pink anyway, and I don’t like fucked up preps like you.” I snapped. Hargrid had been mean to me before for being gottik.

“No Enoby.” Hargrid says. “Those are not roses.”…He suddenly looked at them with an evil look in his eye and muttered Well If you wanted Honesty that’s all you haD TO SAY! .

“That’s not a spell that’s an MCR song.” I corrected him wisely.

“I know, I was just warming up my vocal cordes.” Then he screamed. “Petulus merengo mi kremicli romacio(4 all u cool goffic mcr fans out, there, that is a tribute! specially for raven I love you girl!)imo noto okayo!”

And then the roses turned into a huge black flame floating in the middle of the air. And it was black.

Pictured: Ebony Raven and “a huge black flame floating in the middle of the air.”

If Ebony had accepted Hagrid, he would have turned into Harry, united with her for the second alchemical wedding, and revealed her True Self. Instead, he produces the sign of black fire. The black sun (sol niger) is one of the most ominous symbols in alchemy. Its various connotations are too complicated to explain here (see The Black Sun: The Alchemy And Art Of Darkness for a thorough review) but they are generally highly negative. “The sol niger [is] Saturn, is the shadow of the sun, the sun without justice, which is death for the living.”

Yet at times the Black Sun can be useful; suffering itself becomes a catalyst for transformation. This seems to be one of those times. Ebony is shocked into acknowledging Hagrid (“Now I knew he wasn’t a prep. “OK I believe you now'”)

Is this good enough for her to find her True Self? Going back to the text:

And then the roses turned into a huge black flame floating in the middle of the air. And it was black. Now I knew he wasn’t a prep.

“OK I believe you now wtf is Drako?”

Hairgrid rolled his eyes. I looked into the balls of flame but I could c nothing.

“U c, Enobby,” Dumblydore said, watching the two of us watching the flame. “2 c wht iz n da flmes(HAHA U REVIEWRS FLAMES GEDDIT) u mst find urslf 1st, k?”

“I HAVE FOUND MYSELF OK YOU MEAN OLD MAN!” Hargrid yelled.

Dumbledore tells Ebony that she needs to find herself. But it is Hagrid who retorts that he has found herself. I take this to mean she has failed to integrate with Hagrid; he remains a psychopomp figure, containing the knowledge of Ebony’s Self but unable to transmit it to her.

Nevertheless, something has been gained, because:

Anyway when I got better I went upstairs and put on a black leather minidress that was all ripped on the ends with lace on it. There was some corset stuff on the front. Then I put on black fishnets and black high-heeled boots with pictures of Billie Joe Armstrong on them. I put my hair all out around me so I looked like Samara from the Ring (if u don’t know who she iz ur a prep so fuk off!) and I put on blood-red lipstick, black eyeliner and black lip gloss.

Ebony is still dressed mostly in black, but has a tiny bit of white (the lace) and the slightest bit of red (the lipstick). She is basically back in nigredo now, with only hints of the other stages she has tried to attain.

All of this catches up with her in the total fuckup of an attempted alchemical wedding that follows. If she is actually in albedo, she should be uniting with her animus. If she is actually in rubedo, she should be uniting with God. Instead, it’s just Draco again.

Then I saw a poster saying that MCR would have a concert in Hogsmede right then. We [Ebony and Draco] looked at each other all shocked and then we went 2gether.

There is a long list of Ebony and Draco’s preparations for the concert (cf. the preparation chapters of The Chymical Wedding Of Christian Rosenkreutz, and note the part where Ebony calls Draco “Christian” at the beginning of Chapter 16).

The original chemical romance.

But the actual concert itself is a disaster:

Gerard was da sexiest guy eva! He locked even sexier den he did in pix. He had long raven blak hair n piercing blue eyes. He wuz really skinny and he had n amazing ethnic voice. We moshed 2 Helena and sum odder songz. Sudenly Gerard polled of his mask. So did the other membez. I gasped. It wasn’t Gerard at all! It was an ugly preppy man wif no nose and red eyes… Every1 ran away but me and Draco. Draco and I came. It was…….Vlodemort and da Death Deelers!

The supposed concert/date/wedding proves utterly disastrous – “My Chemical Romance” is just Voldemort wearing a mask. Draco and Ebony flee. Chapter 18 begins:

I woke up the next day in my coffin. I walked out of it and put on some black eyeliner, black eyesharrow, blood-bed lipstick and a black really low-cut leather dress that was all ripped and in stripes so you could see my belly

She is back in the coffin, dressed in all black (she tries to say the word “red”, but fails). She has lost even the hints of previous stages.

Chapters 18 – 22: Third Path

At the beginning of Chapter 18, Ebony is in her coffin, wearing all black. She immediately meets up with Draco (fourth paragraph of Chapter 18). Immediately after this, Dumbledore suddenly appears (fifth paragraph of Chapter 18). There is purification by water (ninth paragraph of Chapter 19, “I ran to the bathroom”). Hagrid suddenly apperas (tenth paragraph of Chapter 19, “Suddenly Hargrid came. He had appearated.”) Hagrid says there is a My Chemical Romance concert that night (thirteenth paragraph of Chapter 19). We have speed-retraced the entire alchemical path accomplished previously.

But this time, Ebony accepts Hagrid by recognizing him as the keeper of the secret of the alchemical wedding (“’U no who MCR r!’ I gasped.”) And so at the concert, the other half of the animus appears to Ebony in a a merciful form (“Vampire and I began 2 make out, moshing to the muzik.”) Instead of going back to her coffin alone, “we went back to our coffins frenching each other…on the gothic red bed together”. Notice that instead of being in a black coffin, they are now in a red bed, the symbol of the bridal chamber after the second alchemical wedding:

Take the fayer Roses, white and red

And joyne them well in won bed.

This ends the first traversal of the Tree of Life. Part 2 of My Immortal will continue some of the same themes, but subordinate them to a more specific purpose: a reworking of Goethe’s Faust, Part II. In the process, it will show us the completion of the third alchemical wedding and the creation of the Philosopher’s Stone.

Chapters 22 – 39: Faust II, Act 3

For many readers, the weirdest part of My Immortal is the subplot beginning around Chapter 23, where Sybil Trelawney helps Ebony go back in time to the 1980s to seduce young Tom Riddle. Using various bizarre time machines (including Marty McFly’s Delorean) Ebony successfully goes back, woos Tom, returns with him to her own time, and has sex with him.

This is bizarre, but it’s a close parallel of Faust II, Act 3, where the Sibyl helps Faust go back in time to ancient Greece to seduce Helen of Troy. Using various bizarre time machines (including riding on the back of the centaur Chiron) Faust successfully goes back, woos Helena, returns with her to his own time, and has a child with her.

There’s actually an even more direct reference. In Chapter 38, Ebony and Tom are talking about music. Even though Ebony has previously committed to not talking about My Chemical Romance because they didn’t exist in the 1980s, she brings up MCR anyway and Tom is mysteriously familiar with them. Then Ebony says something amazing: “Lol, I totally decided not 2 comit suicide when I herd Hilena.”

In context, “Hilena” is a mispelling of “Helena”, an MCR song. But “Helena” is also Goethe’s Helen of Troy figure. I’ll refer you to The Helena Myth In Goethe’s Faust And Its Symbolism for the full treatment, but the point is that this is basically a one-sentence summary of Part II, Act 3 of Faust. It is Faust’s encounter with Helena, representing the feminine ideal, which saves him from despair and makes life worth living. The Ebony-Tom relationship in My Immortal is a close parallel to this, and here it cheekily calls out the original to anyone with ears to listen.

But the matchup is not perfect. Faust scholars identify three alchemical weddings in the book: first to Gretchen, then to Helena, then to a divine figure representing the Virgin Mary. This mirrors the traditional opus – first you unite with your unconscious, then with the anima, then with divinity. The Helena references in Faust all correspond to the second stage – Helena is Faust’s anima.

Ebony has already had an alchemical wedding with her animus in Chapter 20 – the My Chemical Romance concert where she makes out with Vampire. Looking back, there is a Helena reference there too:

Vampire and I began 2 make out, moshing to the muzik. I gapsed, looking at da band. I almost had an orgasim. Gerard was so fucking hot! He begin 2 sing ‘Helena’ and his sexah beautiful voice began 2 fill the hall.

But we should be done with these references! Ebony should be completely in the third stage by now! In Chapter 38, she attends a concert with Satan. This ought to be her third alchemical wedding: union with a divine figure. Given that she is Satanist, the appropriate divine figure is right there. Instead, they’re not only talking about Helena, they’re unconsciously re-enacting the Helena subplot from Faust. Why?

I think the last alchemical wedding never completed. She “makes out” with Vampire, but does not have sex with him. The union is only partial. Her date with Satan is a confused attempt at the second and third alchemical weddings combined, which is why she can’t decide whether to call him Tom Riddle (another animus figure – remember that canonically Harry Potter is a horcrux of Tom Riddle and they share part of the same soul) or Satan (the divine figure). So although the explicit text is a bunch of parallels to the third/final alchemical union with the divine, the symbology and the Faust metaphor are caught in the second stage.

Once again, things have gotten extremely bad for Ebony’s spiritual growth. We saw a prelude of this with the omen of the Black Sun in Chapter 12. Now things have deteriorated further. She is going to have to take the hard route: she must go through the fire.

In the middle of the concert with Satan (Chapter 38), the song suddenly becomes dissonant. James Potter tries to shoot Lucius Malfoy, but Ebony jumps in front of the bullet and dies.

Chapters 39 – 44: Faust II, Acts 4-5

Chapter 39 starts with a prelude saying that it’s written by a hacker who hates My Immortal. He cracked the real author’s password and plans to ruin the story by writing a deliberately uncharacteristic chapter. He breaks with all of the normal author’s stylistic conventions, eg by using good spelling and grammar throughout. This new chapter ends with Ebony going to Hell, staying there for all eternity, and never being able to do anything Goth ever again.

Then the original author reasserts control, apologizes for letting her account get hacked, and starts over. According to the new, canon timeline, Ebony survives her apparent death (because she was back in time, and so couldn’t really die) and returns to her own era.

Compare to the ending of Faust. Mephistopheles appears and drags Faust’s soul to Hell. But a choir of angels show up, distract him, and steal Faust’s soul away to Heaven.

The end of My Immortal also revolves around Ebony’s redemption from Hell, but via a novel plot device making use of the fourth wall. Ebony is saved not by a spiritual conflict on her own plane, but by a conflict on a higher plane – that between her Author and a hacker trying to destroy the Author’s story. When the Author wins by getting her password back, Ebony is released from Hell; her eternal damnation is retroactively cancelled. This is a sort of weird way of doing a deus ex machina, but honestly it’s less jarring than Goethe’s version.

Upon his salvation, Faust meets all the female characters from his life again, and they redeem him through the power of the Eternal Feminine. Similarly, upon her release Ebony meets all the male characters from her own life. In her case, this leads to an orgy. In Chapter 43, she has a foursome with Draco, Vampire, and Satan. Now, finally, she is consummating the final alchemical wedding, the “union of all opposites” in which she achieves an ultimate integration with all the male aspects of her personality.

Chapter 44, the last chapter of My Immortal, has no parallel in Faust. Instead of the hieros gamos between masculine and feminine completing the redemptive process and ending the Great Work, in My Immortal it only initiates the final apocalypse. All the good characters and all the evil characters show up in the Great Hall and begin to fight in a difficult-to-follow scene. Finally, Dumbledore tells Ebony she has to fulfill her destiny and kill Voldemort. In the last line, Ebony shouts “ABRA KEDABRA!!!!!!!!!!!11111” and the story ends.

What is the meaning of this final word? It partly corresponds to the Harry Potter spell avada kedavra. But the spelling is neither the Rowling version nor the traditional stage magician version.

The closest match I can find is from Aleister Crowley’s Book of the Law, whose last sentence is “The ending of the words is the Word Abrahadabra” In Crowley’s commentaries, he explains that “[abrahadabra is] the Word of the Aeon, which signifieth The Great Work accomplished.”

So My Immortal ends with an occult term signifying the “ending of words” and completion of the alchemical Great Work. This suggests Ebony’s redemption was successful; she has escaped Hell, merged with the Eternal Masculine, and triumphed over Voldemort (representing death). She has created the Philosopher’s Stone and achieved the story’s namesake immortality.

But in a different commentary, Crowley also writes: “Abrahadabra is the glyph of the blending of the 5 and 6, the Rose and the Cross.”

…which suggests one last, “hidden” chapter.

The hacker subplot in Chapter 39 suggests that “the story” should be taken to include not just Ebony’s own story, but the frame story in which an author is writing My Immortal as a Harry Potter fanfiction and confronting reviewers, hackers, etc. The Ebony story ends with Ebony speaking the mystic word that unites Rose and Cross. The frame story picks up with a woman named Rose Christo appearing and identifying herself as the author. So My Immortal can be said to end with Ebony abandoning her false self (Ebony Dark’ness Dementia Raven Way, the dark leaden substance of the nigredo), and becoming her divine higher Self (Rose Christo, the completed union of Rose and Cross, who exists on a higher plane than Ebony).

Most of the second part of My Immortal mirrors Part II of Faust. But its ending transcends the source material. The moral of Faust is that you can be redeemed. But My Immortal actively demonstrates the redemption that Faust can only point at. It follows the progress of Ebony from a contemptible character in a terrible fanfiction, through the alchemical process of uniting Rose and Cross, to become Rose Christo, a woman who lives in the real world.

It tells us that every one of us is a Mary Sue in the bad fanfiction of our lives – the narrative created by the ego in order to maintain our illusory selfhood. And in the tradition of other great alchemical texts like The Chymical Wedding Of Christian Rosenkreutz and Faust, it gives us a blueprint for escaping that fanfiction and completing the alchemical Work of breaking into reality.

As the end of Faust puts it:

All of the transient,

Is parable, only:

The insufficient,

Here, grows to reality:

The indescribable,

Here, is done.

Woman, eternal

Beckons us on.