It seems to be Gush About The Victorians Month in the academic community or something.

How The Mid-Victorians Worked, Ate, and Died (h/t Michael Vassar) claims that the mid-Victorian period was a golden age of health during which life expectancy was as high or higher than today and the diseases we consider a “normal part of aging” simply failed to exist. No cancer, no heart disease, just living happily and healthily until you were felled by tuberculosis at age 85. They credit the Victorian diet – in particular its lack of additives and preservatives and its overload of nutrients, the latter made possible by very high calorie diets that compensated for their increased level of physical activity. The authors admit we probably can’t safely replicate such a high calorie diet in today’s sedentary society, but suggest taking lots and lots of vitamins and supplements in order to get the same high nutrient level the Victorians did.

I am really really bad at understanding nutrition (AT LEAST I ADMIT IT!), so I will limit this to attempts to fact-check a few claims, plus some extremely speculative commentary. Let’s start with the thesis:

We argue in this paper, using a range of historical evidence, which Britain and its world-dominating empire were supported by a workforce, an army and a navy comprised of individuals who were healthier, fitter and stronger than we are today. They were almost entirely free of the degenerative diseases which maim and kill so many of us, and although it is commonly stated that this is because they all died young, the reverse is true; public records reveal that they lived as long – or longer – than we do in the 21st century.

And the evidence in support:

The fall in nutritional standards between 1880 and 1900 was so marked that the generations were visibly and progressively shrinking. In 1883 the infantry were forced to lower the minimum height for recruits from 5ft 6 inches to 5ft 3 inches. This was because most new recruits were now coming from an urban background instead of the traditional rural background (the 1881 census showed that over three-quarters of the population now lived in towns and cities). Factors such as a lack of sunlight in urban slums (which led to rickets due to Vitamin D deficiency) had already reduced the height of young male volunteers. Lack of sunlight, however, could not have been the sole critical factor in the next height reduction, a mere 18 years later. By this time, clean air legislation had markedly improved urban sunlight levels; but unfortunately, the supposed ‘improvements’ in dietary intake resulting from imported foods had had time to take effect on the 16–18 year old cohort. It might be expected that the infantry would be able to raise the minimum height requirement back to 5ft. 6 inches. Instead, they were forced to reduce it still further, to a mere 5ft. British officers, who were from the middle and upper classes and not yet exposed to more than the occasional treats of canned produce, were far better fed in terms of their intake of fresh foods and were now on average a full head taller than their malnourished and sickly men.

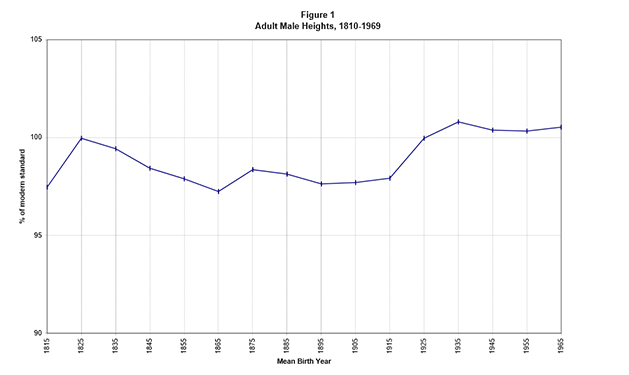

This is very suspicious. If the British Army started recruiting from different populations, or started lowering their standards generally because they needed more men, these data are useless. I tried to find an alternate source of height data, and the best I could come up with was the extremely thorough Height, Weight, and Body Mass of the British Population Since 1820, who say:

This graph seems to do quite well at picking up real decreases in height like the one starting in the birth cohort of 1825 (possibly due to the Corn Laws?), but it has pretty much nothing to say about any great collapse in the last few years of the 19th century. Assuming the average army recruit was 20 years old. In 1883, they would have been in the 1863 birth cohort; in 1901, in the 1881 birth cohort. But in fact, the 1881 birth cohort is taller on average than the 1863 birth cohort!. The army’s troubles with finding sufficiently tall infantrymen cannot be due to the Amazing Shrinking Englishman – it must be a matter of casting a wider recruiting net or something.

The crude average figures often used to depict the brevity of Victorian lives mislead because they include infant mortality, which was tragically high. If we strip out peri-natal mortality, however, and look at the life expectancy of those who survived the first five years, a very different picture emerges. Victorian contemporary sources reveal that life expectancy for adults in the mid-Victorian period was almost exactly what it is today. At 65, men could expect another ten years of life; and women another eight. This compares surprisingly favourably with today’s figures: life expectancy at birth (reflecting our improved standards of neo-natal care) averages 75.9 years (men) and 81.3 years (women); though recent work has suggested that for working class men and women this is lower, at around 72 for men and 76 for women.

Given that modern pharmaceutical, surgical, anaesthetic, scanning and other diagnostic technologies were self-evidently unavailable to the mid-Victorians, their high life expectancy is very striking, and can only have been due to their health-promoting lifestyle. But the implications of this new understanding of the mid-Victorian period are rather more profound. It shows that medical advances allied to the pharmaceutical industry’s output have done little more than change the manner of our dying. The Victorians died rapidly of infection and/or trauma, whereas we die slowly of degenerative disease. It reveals that with the exception of family planning, the vast edifice of twentieth century healthcare has not enabled us to live longer but has in the main merely supplied methods of suppressing the symptoms of degenerative diseases which have emerged due to our failure to maintain mid-Victorian nutritional standards. Above all, it refutes the Panglossian optimism of the contemporary anti-ageing movement whose protagonists use 1900 – a nadir in health and life expectancy trends – as their starting point to promote the idea of endlessly increasing life span. These are the equivalent of the get-rich-quick share pushers who insisted, during the dot.com boom, that we had at last escaped the constraints of normal economics. Some believed their own message of eternal growth; others used it to sell junk bonds they knew were worthless. The parallels with today’s vitamin pill market are obvious, but this also echoes the way in which Big Pharma trumpets the arrival of each new miracle drug.

I was wondering how long it would take “Big Pharma” to make an appearance.

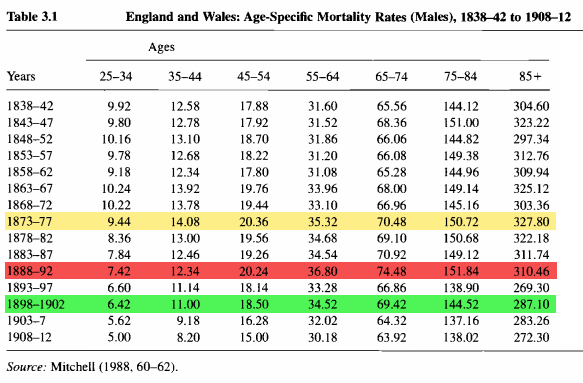

Anyway, here we turn to Health and Welfare During Industrialization, which includes the following table:

This is confusing, so let me explain.

I’ve taken the mortality tables from Steckel and deleted everything before age 25. Clayton and Rowbotham admit that infant mortality has improved since the Victorian period, so we’re not counting that.

I’ve marked the 1873 to 1877 period – the last period unambiguously before Clayton and Rowbotham’s 1880 “nutritional collapse” – in gold. This is our baseline.

We notice that the subsequent period actually has lower mortality in nearly every category. This is fine. Just because they’ve invented less nutrititious food doesn’t mean that people have started eating it yet, or that it’s had time to affect their health. Instead, I’ve looked for the worst post-1880 period and marked that in red as the bottom of the “nutritional collapse”. As you can see, it’s 1888 – 1892.

Finally, I’ve taken the period including 1900 – what they describe as “a nadir in health and life expectancy trends”, and marked it in green.

As we can see, the “nadir” – 1900, is actually lower mortality in all age groups than the “golden age” of 1873 – 1877. The “collapse”, if it occurred at all, was a tiny statistical blip that was then easily overpowered by the general secular trend of decreasing mortality.

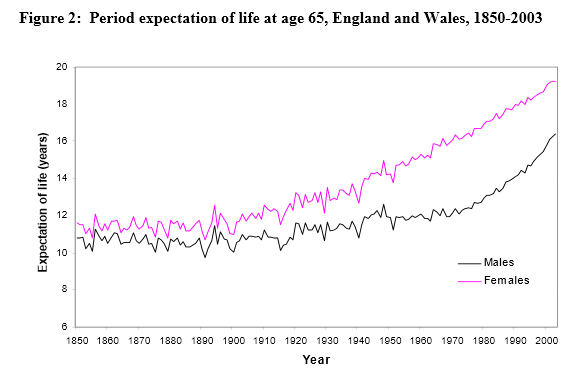

I don’t know exactly how the authors would like me to consider “people born in 1900” vs. “people dying in 1900”, but luckily I also happen to have life expectancy at age 65 for Britain for the entire period of 1841 to 2001 (God, I love the Internet!):

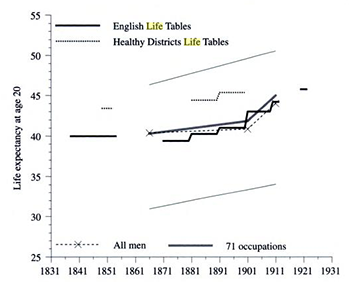

There’s nothing on there that could remotely be the kind of collapse they’re talking about, unless it be that little blip around 1890 which is more than compensated for five years later. Annnnnd here’s some more data, divided by occupation and showing life expectancy at age 20:

This isn’t especially high resolution, but it’s interesting in that it suggests adult life expectancy in the Victorian period was around 65 and not the more modern 75. Sure enough, the book I took it from estimates life expectancy at age 20 (ie excluding childhood mortality) to be about 62.5. Unfortunately, I can’t access Clayton and Rowbotham’s sources, so I can’t tell whether they make an even better argument that it really was 75. But this matters for claims like “there was much less cancer”, because cancer increases a lot with age and so if you’re cutting off the end of the age distribution of course you’re going to get less cancer (imagine you learned people never went bald in caveman times – this could be either because they all ate nutritious mammoth meat, or because they all died before age 30).

Overall I’m going to say I wish I could access their sources, but the fact that they don’t quote any numbers or show any graphs in support of their “life expectancy decrease from 1880 to 1900” hypothesis makes me suspect they don’t have any [EDIT: See bottom of post].

Their next point is that the Victorians had much less cancer and heart disease than people today. This I am totally willing to believe. The authors provide ample evidence in another paper of theirs, and it accords well with very similar evidence presented by Gary Taubes in Good Calories, Bad Calories.

The Victorian Age was before the mass-marketing of cigarettes, before most of the carcinogenic chemicals we inhale all the time, and their diet contained ample fruits and vegetables – foods that we know lower cancer and heart disease risk. Many of them were manual laborers, there were much fewer obesogenic foods, and people were generally normal weight. It is not mysterious or revolutionary to propose they had less cancer and heart disease than we did.

But let’s look at Clayton and Rowbotham’s explanation:

Degenerative diseases are not caused by old age (the ‘wear and tear’ hypothesis); but are driven, in the main, by chronic malnutrition. Our low energy lifestyles leave us depleted in anabolic and anti-catabolic co-factors; and this imbalance is compounded by excessive intakes of inflammatory compounds. The current epidemic of degenerative disease is caused by widespread problem of multiple micro- and phyto-nutrient depletion (Type B malnutrition.)

With the exception of family planning and antibiotics, the vast edifice of twentieth century healthcare has generated little more than tools to suppress symptoms of the degenerative diseases which have emerged due to our failure to maintain mid-Victorian nutritional standards. The only way to combat the adverse effects of Type B malnutrition, and to prevent and / or cure degenerative disease, is to enhance the nutrient density of the modern diet.

Whoa whoa whoa whoa whoa.

Gary Taubes does a pretty good job recording all the primitive cultures that also have no degenerative diseases. The Eskimos are one such. They basically just eat meat. You can also find cultures pretty much anywhere, with any diet, who also lack these degenerative diseases. In fact, I think people who are actually malnourished – starving Africans and the like – still have lower rates of these degenerative diseases as long as they’re not eating a “modern” diet.

To me, this suggests that their “phytonutrient depletion” hypothesis needs to contend with another – that it’s not that we’re not getting enough of the right stuff, but rather that we’re getting too much of the wrong stuff. As far as I know, this is what mainstream nutrition science believes as well as most of the more interesting crackpots, although of course everyone differs as to what the wrong stuff is. It is a promising and venerable theory and nothing the authors of this paper have said thus far casts the slightest doubt upon it. Indeed, they admit that the “nutritional collapse” was caused by the introduction of preserved foods, additives, and cheap sugar.

Our levels of physical activity and therefore our food intakes are at an historic low. To make matters worse, when compared to the mid-Victorian diet, the modern diet is rich in processed foods. It has a higher sodium/potassium ratio, and contains far less fruit, vegetables, whole grains and omega 3 fatty acids. It is lower in fibre and phytonutrients, in proportional and absolute terms; and, because of our high intakes of potato products, breakfast cereals, confectionery and refined baked goods, may have a higher glycemic load. Given all this, it follows that we are inevitably more likely to suffer from dysnutrition (multiple micro- and phytonutrient depletion) than our mid-Victorian forebears…

Since it would be unacceptable and impractical to recreate the mid-Victorian working class 4,000 calorie/day diet, this constitutes a persuasive argument for a more widespread use of food fortification and/or properly designed food supplements (most supplements on the market are incredibly badly designed; they are assembled by companies that do not understand the real nutritional issues that confront us today, and sell us pills containing irrational combinations and doses that can do more harm than good.

To insist, as orthodox nutritionists and dieticians do, that only whole fruit and veg contain the magical, health-promoting ingredients represents little more than the last gasp of the discredited and anti-scientific theory of vitalism (‘Vitalism—the insistence that there is some big, mysterious extra ingredient in all living things—turns out to have been not a deep insight but a failure of imagination’, Daniel Dennett) Even the stately FSA concedes that fruit juices count towards your five-a-day, as do freeze-dried powdered extracts of fruits and vegetables. As our knowledge of phytochemistry and phytopharmacology increases, it has become perfectly acceptable to use rational combinations of the key plant constituents in pill or capsule form.

These arguments are developed in ‘Pharmageddon’, a medical textbook which illustrates how micro- and phyto-nutrients can be specifically combined in order to prevent and treat the chronic degenerative diseases that characterise and dominate the 20th and 21st centuries; and how they could be integrated into our food chain in order to reduce the contemporary and excessively high risks of the degenerative diseases to the far lower mid-Victorian levels.

So first things first. I am almost sure I went to medical school, and the sorts of textbooks I read there all had names like “Essentials Of Biochemistry, Third Edition”, and “Introduction To Gastroenterology” and almost never names like “Pharmageddon”.

Second, the authors cite some sources for their claim that all supplements currently on the market are poorly designed and do more harm than good. These sources show that a bunch of different supplements are either ineffective or cause cancer, and are entirely correct. What they do not cite are any sources that show that “correctly designed” supplements do more good than harm. This is because those sources do not exist because no one has ever discovered that.

The reason the medical community isn’t switching wholesale from evil pharmageddon-causing drugs to all-natural Victorian-approved nutrient supplementation isn’t because they’re in the grip of Big Pharma, it’s because no one can find supplements that are consistently proven to work.

(the medical community actually is saying “eat right and exercise”, but NO ONE LISTENS)

And yes, part of the lack of working supplements is the coordination problem of “there’s no money in studying supplements”. I think it would be great if we could figure out some way to coordinate supplement studies more effectively. But it’s kind of hard to make that case when all the supplement studies that have been done have been total duds and the pro-supplement community has just kept replying with “But those supplements were poorly designed!” and then suggesting a perplexing and extremely contradictory trove of other possible designs, all of which themselves are later found not to work.

One point that seriously enlightened me, thought, was the authors’ comments on vitalism. It’s definitely true that eating whole foods has useful properties (like reducing risk of diseases) and also definitely true that taking supplements that supposedly share vitamins with those foods doesn’t. And it’s also true that I was previously taking this as an Unfortunate Fact Of Life. Which is dumb. Of course we should be trying to figure out what magical property of whole foods makes them effective and then trying to deliver that magical property in a pill. I am disappointed at myself for not realizing that was important sooner, and that alone makes me profoundly grateful I read this study.

It’s just that I don’t think we’re quite there yet, and until we are, supplementation isn’t all that useful.

In summary, I can’t confirm this paper’s suggestion of dire health costs from a “nutritional collapse” in the 1880s. However, the notion of a gradual rise in cancer, heart disease, and other degenerative diseases linked to a modern diet seems correct. Their attribution of this to nutrient deficiency is unsupported and probably only a small part of the problem, and their opinions on supplementation seem to possibly veer into crackpottery. However, they are right to note that we need a better science of supplementation and that once we develop this science, supplements really really ought to work.

EDIT: Andrew G points out in comments that the study compared Victorian life expectancy at age 60 to modern life expectancy *at birth* in their attempts to say life expectancy was staying about the same. This is clearly not kosher. Victorian life expectancy at age 20 (a good point to rule out childhood mortality) was about 62.5, and modern life expectancy at age 20 is…something older than life expectancy at birth which is 77 or so. So their “life expectancy has stayed the same” argument is completely wrong.

Wait, all supplements are bad for you and/or cause cancer? What about, like, supplementing B vitamins because one is vegan and likely to be deficient in that?

Good question and I’m not sure.

>(the medical community actually is saying “eat right and exercise”, but NO ONE LISTENS)

It seems to me like lots of people are listening, and indeed, we can predict who is listening based on looking at their bodies. Though I suppose there are a lot of people with impressive bodies who take supplements like choline an protein powder. Do those also have the problems you mentioned?

The increased mortality with vitamins seen in some studies is no longer mysterious; it is specifically a result of antioxidants protecting cells from oxidative stress, where cancerous cells benefit from that protection more. (http://rsob.royalsocietypublishing.org/content/3/1/120144.full)

I think the claims about the same nutrients being better when they come from food than when they come from supplements are mostly bunk, but if that were true in a specific case, I expect it’d be either a case of different bioavailability (so adjusting the dose to compensate would be fine), or of release schedule (nutrients in food are released slowly over the course of digestion, which allows time for processing mechanisms to ramp up and down).

Another big difference between the Victorian diet and the American diet is variety; they ate much fewer different things. Typical Americans eat so many different foods, it’s impossible to keep good track of how each food make them feel later, or of which foods sate which types of hunger. (Yes, there is more than one type of hunger and yes, matching them up to foods is a thing which humans would normally do.)

And for what it’s worth, I do think that micronutrient deficiency represents a big chunk of the problem. It’s not the *whole* problem, it just happens to be the part of that’s easiest to figure out and deal with.

Okay, I was raised on goat’s milk and sea air, but this was before the days of “organic food” and was just called “living in the country”.

There is definitely a difference of taste between, say, eating new potatoes that have been grown using seaweed as fertiliser and earing the new season potatoes you get in the supermarket. Probably a lot of the micronutrients we are now missing were provided in exactly that way, e.g. households having small vegetable plots and using things like seaweed brought straight up from the strand and used as fertiliser, which provided iodine in the soil and then that was taken up by the plants (yeah, when I was a kid, my father had us hauling it by the bucketful for his potato rows since we lived literally three minutes away from the seaside).

Artificial fertilisers in intensive farming probably don’t have the same effect. So I would be more willing to give credence to the notion of the entire environment of what we eat contributes to the benefits and you can’t simply replicate that by saying “Aha! Compound X is the magic ingredient, let’s extract/manufacture that on a commercial basis and stick it in pill form!”

Jim, the article you linked sounds less sure that antioxidant supplements cause cancer: “the time has come to seriously ask whether antioxidant use much more likely causes than prevents cancer.” How certain is this?

Over the course of the 20th century, people continued to shrink, so the minimum height today to join the US Marines is 4’10”. (I know this because I typed “marine height” into google because I wanted to know the height of Le Pen.)

And so presumably in another century or less, the American military will have dwindled to a fleet of drones controlled by imported African Pygmies.

Having had a Victorian-era grandmother, let me take a shot at some of these statements:

“our high intakes of potato products, breakfast cereals, confectionery and refined baked goods”

19th (and pretty much 20th and 21st) century Irish diets revolved around potatoes and bread, with some added grains like oats in porridge. The most exotic vegetable was probably kale (things like garlic were fancy foreign notions). They’re right about less processed foods, but the thing is, this wasn’t due to virtue, it was due to poverty – and as soon as the working classes could afford to buy shop bread (instead of making their own soda or wholemeal bread) and especially buns and cakes, they went crazy on them.

Not being able to afford to consume a lot of red meat and working long hours of back-breaking physical toil (even washing clothes is hard work when it all has to be done by hand) probably is behind the general better health, but there isn’t some magic “Victorian diet” that will cure all our modern ills.

Regarding the medical advice about “Eat right and exercise”, I wish that there was some consistent advice. To date, what I’ve seen/had recommended is: (a) take fish oil supplements at least, but better if you eat portions of oily fish during the week, they’re good for cardiovascular health (b) oops, our latest study shows that fish oils make no difference at all to heart health (c) eat more fruit and vegetables (d) except if you’re diabetic or have developed type 2 diabetes, because there are sugars in fruits and vegetables and eating your five portions a day will send your blood sugar rocketing when you’re supposed to be cutting it down to below 5 mmol/L (this has been particular fun for me trying to eat a balanced diet)

You can stop reading the paper after the second sentence of the abstract:

This is not just wrong, but hilariously wrong.

Sure, but that’s not what they’re saying. Their statement, read straightforwardly, implies that basal metabolic consumption is nearly zero, which is ludicrous. Mean basal metabolic calorie consumption is around 1500 calories. If a modern person actually burns 2000 calories, and a Victorian burned 4000, the Victorian would be doing five times as much work. It’s a total howler of a statement, and it’s in the abstract.

If the problem is less “you don’t eat enough vitamin A” and more “you eat too much processed sugar” then adding “vitamin A pills” to your processed sugar intake won’t help; whilst adding more carrots to your diet probably means removing something else from it (after eating a certain amount you are probably no longer hungry for more) which might mean removing some of the excess processed sugar…

“Eat right and take regular exercise” would be easier advice to follow if “right” and “regular” were better defined. As it stands it not really… advice, so much as it is “trite nonsense”.

Most of what we ‘know’ about eating right, beyond ‘avoid obvious nutrional deficiency diseases’, is wrong or not even wrong. People still believe the lipid hypothesis. Nobody knows a damned thing.

As far as exercise goes, there’s an obvious correlation between exercise and health, but it’s very rare to find a study that controls for causation running in the opposite direction. That is, it’s clear, but nearly never acknowledged, that the healthy are more able and more inclined to exercise than the ill; in particular, those who become ill or injured (sometimes from exercise itself!) are prone to reduce or stop exercise activity. So yes, there’s an obvious correlation, but there’s something very wrong with the usual interpretation.

More about what’s known about exercise, including that it seems to be bad for about 10% of people.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?feature=player_embedded&v=E42TQNWhW3w#!

This is a great video! Thanks for the link, going to pass it on.

Also blood pressure. Over here it’s still pretty much that 140/80 is normal (although the American measure of 120/80 is being adapted more and more).

But now I see American recommendations that you should be hitting for blood pressure of 110/70, and when I said to myself “Where the hell did these figures come from?”, apparently they’re based on some Amazonian tribe.

Well, I’m not an Amazonian Indian living in the middle of Brazil, I’m a short, fat, white Irishwoman who can’t pretend to be middle-aged any more living in a small coastal town. The only time I had blood pressure readings like that was after a surgical procedure, and it’s not generally recommended you go about under the effects of anaesthesia in your everyday life.

It’d be a hell of a lot easier to hit targets if they didn’t keep moving the goalposts. “Oh, we said this was the reading you needed to be normal? We lied! You’re going to die unless you drop another (insert whatever measure)!”

Correction: I’ve just looked up definitions, and depending which you use, I have another 4-11 years when I can call myself middle-aged.

Woo-hoo!

Just you wait, all you kids, until you hit your late forties and all of a sudden time hits you like a ton of bricks and you find yourself actually needing to go to the doctor where for decades you just took some aspirin and stayed in bed. Oh, yes.

Did… did they just compare Victorian life expectancy at 65 with modern life expectancy at birth?

Even excluding infant mortality, it’s inexcusable not to understand that additional life expectancy at age X is not the same thing as additional life expectancy at age Y plus the difference between X and Y.

Yeah, I noticed that too. I wanted to scream “statistical sleight-of-hand”, although I suppose it’s possible, as you suggest, that it’s merely a glaring mistake rather than actual dishonesty.

So, Scott, your sources are undoubtedly correct, and the average Victorian’s adult life expectancy (generally taken to be life expectancy at age 20) is 65, not 75. But, of course, some people died between the ages of 20 and 65. If you’re alive at age 65, obviously you didn’t die before that, so life expectancy at age 65 must be higher than life expectancy at age 20.

Worth noting, current (US, 2009) life expectancy at age 65 is 17 years for men and 20 for women. Life expectancy at age 75, which confirms that there are some gains in old-age life expectancy since the Victorian era.

Oh wow, I didn’t even notice that! Good catch! That’s probably why my figures for life expectancy at 20 are so different than theirs!

These mistakes wouldn’t be acceptable in an undergraduate term paper. How did this get published?

Recent tests suggest that peer review in scientific publications is not generally distinguishable from random chance.

(cynical, moi?)

“Of course we should be trying to figure out what magical property of whole foods makes them effective and then trying to deliver that magical property in a pill.”

Why? You can’t just prescribe “Eat Broccholi”?

You can, but no one listens!

(I have no right to complain here, I hate all vegetables and most fruits and can’t force myself to eat more than a tiny amount of them. But I would happily take a vitamin pill if it worked.)

Huh. Me, I’ve found that being stir-fried in a Chinese restaurant improves the taste of many vegetables…

More specifically, stir-frying anything green and bitter with fish sauce, rice vinegar, an egg, and sesame oil seems to eliminate the bitterness almost entirely. (This is the way greens are prepared for pad see ew; I usually don’t try to copy the whole dish because frying rice noodles without getting one giant gross blob is Hard.) I can’t stand bok choy generally, but when it’s cooked this way I actually want to eat it.

Unfortunately I don’t have a similarly good solution for fruits. They’re just kind of icky, and if you make them into pie like people keep suggesting then they’re slimy as well.

I find that you usually don’t need to do anything to most fruits to make them tasty, because they’re already full of sugar. Some manage to be more sour than sweet, though, which is why people do things like dip strawberries into chocolate and cover grapefruits with sugar.

I don’t know if I am surprised or not. I don’t know if that applies to me as well or not, in fact. It seems that, since people are eating anyway, if you could provide clear, unambiguous, specific benefits for certain foods in non-marketing speak that should be better than saying take this pill until you die. But then, I know a lot, if not most, American are on medication essentially until they die, so what’s one more?

I do think you would see some risk adjustment from this, such that once you had this pill that granted the bare minimum people would take it as liscense to cut out the few veggetables or what have you that htey were eating and find them selves not much better off.

This is unrelated, but I just was on a part of this blog that showed me commenter emails, and I realized your email strongly suggests you are one of the people on the Fall From Heaven development team.

If that’s true, please know that that is my favorite Civ scenario of all time and I am profoundly grateful for your hard work and that one of my standard Internet nicknames (Yvain) comes from my favorite character on there and that you are great.

Oh, that’s nice of you to say, yes that’s me, as well as most other “Niki’s Knight”s you’re likely to see around the internet. Prefer a more straightforward name these days.

Actually when I first saw your handle on LW I thought you might be the team member that character was named after (then I recalled that his username wasn’t Yvain but Woodelf and felt silly).

It was a great project and the closest I’ve come to a conworld like Raikoth.

Actually your historical information is incorrect: Not only is there historical evidence of cancer–equal to the population percentage you’d see today, but other degenerative diseases including diabetes, cancer, arthritis, kidney disease, pancreatitis, cholecystitis, kidney and gallstones, spinal and cervical degeneration, stroke, and heart attack, etc. We see evidence in the skeletal and mummified remains, and we can read descriptions of these diseases in the written record, even as far back as Galen the famous Roman physician. Diabetes was named for the fact that sufferer’s urine attracted bees by the Greeks. The main difference between now and then is that sufferers of chronic degenerative diseases simply did not live very long, unless they were very, very lucky–if you can call it that.