A while back when I wrote about how China’s economic development might not have increased happiness there much, Scott Sumner wrote a really interesting response, Does Anything Matter?

He points out that it’s too easy to make this about exotic far-off Chinese. Much the same phenomenon occurs closer to home:

If nothing really matters in China, if even overcoming horrible problems doesn’t make the Chinese better off, then what’s the use of favoring or opposing any public policy? After all, America also shows no rise in average happiness since the 1950s, despite:

1. A big rise in real wages.

2. Environmental clean-up (including lead–does Flint matter?)

3. Civil rights for African Americans

4. Feminism, gay rights.

5. Dentists now use Novocain (My childhood cavities were filled without it)

6. 1000 channels in glorious widescreen HDTV

7. BlogsI could go on and on. And yet, if the surveys are to be believed, we are no happier than before. And I think it’s very possible that we are in fact no happier than before, that there’s a sort of law of the conservation of happiness. As I walk down the street, grown-ups don’t seem any happier than the grown-ups I recall as a kid. Does that mean that all of those wonderful societal achievements since 1950 were absolutely worthless?

But there are exceptions. I recall reading that surveys showed a rise in European happiness in the decades after WWII, and Scott reports that happiness is currently very low in Iraq and Syria. So that suggests that current conditions do matter.

The following hypothesis will sound really ad hoc, but matches the way a lot of people I know talk about their lives. Suppose people’s happiness is normally calibrated around the sort of lifestyle that they view as “normal.” As America got richer after 1950, it all seemed very normal, so people didn’t report more happiness. Ditto for China during the boom years. Everyone around you was also doing better, so you started thinking about how you were doing relative to your neighbors. But Germans walking through the rubble of Berlin in 1948, or Syrians doing so today in Aleppo, do see their plight as abnormal. They remember a time before the war. So they report less happiness than during normal times.

The obvious retort is – modern Chinese grew up when China was very poor. Why didn’t they calibrate themselves to poverty, such that sudden wealth seems good? What’s the difference between a Chinese person going from poverty to wealth, versus a Syrian going from stability to chaos? Might it be a shorter time course? A sudden shock is noticeable, a gradual thirty-year improvement in living standards isn’t?

Probably not. There seem to be a lot of cases where happiness of large groups does change gradually in response to social trends less dramatic than a world war.

First, consider African-Americans. The New York Times calls the increase in black happiness over the past forty years “one of the most dramatic gains in the happiness data that you’ll see”. This is not just about poverty; in 1970, blacks who earned more than 75% of whites were only in the tenth percentile of white happiness. Today, those blacks would be in the fiftieth percentile; they’re still doing worse than would be expected based on income, but not nearly as much worse. This is a very sensible and predictable thing to find. Black people face a lot less racism and discrimination today than in 1970 [citation needed], so assuming that was really unpleasant we shouldn’t be surprised that they’re happier. But notice that this is a time course very similar to the rise of China! It doesn’t look like black people picked a happiness level to calibrate on and then never bothered to adjust. It looks like they adjusted exactly like we would expect them to, even over the course of a multi-decade change.

Second, consider women. In 1970, US women were generally happier than US men. Today, the reverse is true. There seems to be a general pattern around the world of women being happier than men in traditional societies and less happy than men in modern societies (though see Language Log for a contrary perspective). I don’t think of this as a weird paradox. It seems perfectly reasonable to me that having to work outside the home makes people less happy, getting to spend time with their family makes them more happy, and having to work outside the home but also being expected to take care of your family at the same time makes them least happy of all. In any case, the point is that the numbers are changing. Men and women aren’t just fixating on some level of happiness and staying there, they’re altering their happiness level based on real trends, just like African-Americans did (but apparently unlike Chinese).

Third, I was finally able to find a paper that had really good data on change in happiness in different countries, and it supports the idea that happiness can change significantly on a countrywide level.

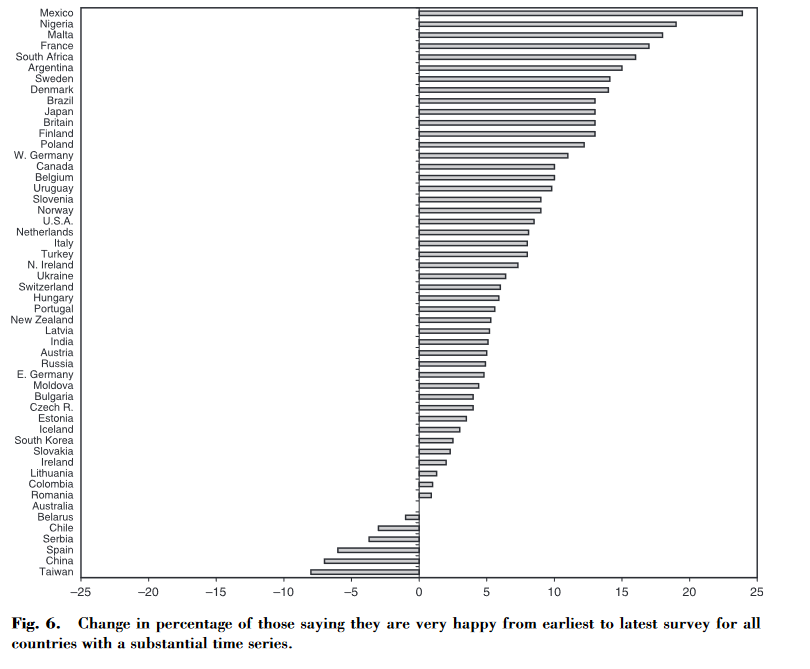

This is change in happiness in a bunch of countries between about 1990 and 2010 (the years were slightly different in each country). There are other graphs for related concepts like life satisfaction and subjective well-being that look about the same.

The most striking finding is that most countries got happier between those two years – sometimes a lot happier. In Mexico, the percent of people saying they were very happy increased by 25 percentage points!

Just eyeballing the graph, there’s not an obvious relationship between happiness and economic growth – China is still near the bottom like we talked about before, and France – a country that’s been First World since forever – is near the top. Even Japan, which is famous for its decades of stagnation, has done pretty well. But the authors tell us that after doing their statistical analyses, there is a strong relationship with economic growth. Okay, I guess.

They also say there’s a dramatic relationship with freedom and democracy. Mexico, the top country on the graph, went from a relatively closed to a relatively democratic government during this time. South Africa, number five, went from apartheid to no apartheid. Some of the ex-Communist countries like Poland and Ukraine also look pretty good here. On the other hand, other ex-Communist countries like Lithuania and Estonia are near the bottom. I wonder if this has to do with cutoff points – since every country started at a slightly different time, maybe they began sampling Poland during the worst parts of Soviet dictatorship and got Lithuania right in the first euphoria of independence? I don’t know. It all seems very noisy.

They also mention that the United States’ supposedly level happiness is kind of a misunderstanding. People say things like “Happiness in the US has been flat from 1950 to today”, but in fact it declined from 1950 to 1979 and increased from 1980 to today. They attribute this to the 1950s being unusually happy; then the 60s and 70s being unusually conflict-prone, and the Reagan Revolution and Clinton years were back to being optimistic. They don’t have data that stretches too long after that.

(This is pretty neat for Reagan and Clinton. When I die, I’ll consider my life a success if people attribute a spike on national happiness graphs to my influence.)

So apparently population happiness levels do change in response to relevant social changes, even on multi-decade timescales. Which brings us back to asking – what’s up with China?

The graph above shows India as doing okay – not great, but okay. But a similar graph on subjective well-being – which should be another way of looking at the same thing – shows India as doing pretty poorly, right down there with China – even though its GDP per capita quadrupled during the period of study.

I see a lot of conflicting perspectives about whether economic growth increases national happiness. It may, but the effect isn’t as big as you’d expect, and is usually overpowered by other factors. Maybe it isn’t even direct, but has something to do with development increasing democracy, liberalism, rule of law, and stability. China got the development, but its happiness genuinely didn’t increase because of country-specific factors that have something to do with how it developed (inequality? pollution? authoritarianism?).

This matches the race and gender data. Blacks saw a big happiness boost during a time when their feeling of freedom (but not their income) increased relative to whites. Women saw a small happiness drop during a time when their income (but not their feeling of freedom) increased relative to men.

So it looks like happiness can change. It just didn’t change in China over the past thirty years. The apparent paradox of improving economic situation and stable/decreasing happiness is genuinely paradoxical. Intangibles are probably just way more important than money, even amounts of money big enough to raise whole countries out of poverty.

Hi Starslatecodex.

Could you please check out this book on psychotherapy. I swear this will be one of the best books you have read. Its groundbreaking and rational. There is nothing like it.

I swear im not selling you anything. I think this book will change the way you look at mental health and help allot of people.

Sincerley.

https://books.google.ca/books?id=Da9lPEDayPMC&printsec=frontcover&source=gbs_ge_summary_r&cad=0#v=onepage&q&f=false

The whole book is free. Please read it. You will thank me later.

I dont have time to explain it all. I know this message may seem absurd. Im begging you to trust me. This is about helping others.

Please.

I’ve heard about this. It’s apparently in the midst of some actual trials (like CBT did) in the UK I think? Will check it out and probably leave some notes/a summary here later.

I’ve gone through the first few chapters and this seems to be very similar to NLP in that the discoverers found a potentially useful tool, flipped their shit, and decided to insist THIS EXPLAINS EVERYTHING. Their enthusiasm then prevented rational inquiry into the thing they discovered. Claims of meeting much higher standards of evidence than CBT and other forms of therapy do not look legit on a first pass. Still some interesting content. Summary to follow.

Are you that Richard guy who was always pushing perceptual control theory in an equally hamhanded way on LW?

This seems like a weird response. PCT seems like the best model of human reasoning to me, and so I wouldn’t be surprised at all if it was deeply relevant to psychiatry. (I would be very interested in you reviewing that eBook.)

I agree with you that Richard Kennaway didn’t present it the best way (that’s why I wrote my own introduction to it), but I have seen a lot of things, especially in the LW sphere, which were gold but presented terribly. My go-to example is probably Direct Instruction, a method of scientifically constructing and testing lesson plans in order to teach as effectively as possible, which was explained in an unscientific and meandering way. (I could keep going–like the time Viliam thought one of MIRI’s major donors was a scam, instead of a professional gambler who speaks English as a second language.)

Maybe you come across more noise than I do, but the quality of ideas and quality of presentation aren’t correlated all that well, and so I think it shouldn’t play a big part of your filter.

Seconded. The explanatory power of PCT seems to be very strong. I would like to see your thoughts if you have strong convictions for/against the theory.

Perception-error modification is like noisy gradient descent in the brain!

the explanatory power seems specious, the cited figures of .96 correlations doesn’t pass a sniff test. First guess is they are double counting the explanatory power of variables that actually funge against each others’ explanatory power. Similar thing happens in using blood markers to predict CVD risk if the researchers aren’t careful. Can’t remember the name for this phenomenon.

Link?

For the record, the only evidence I have for the whole thing not being a scam is your word, Vaniver.

And when I asked you whether you are participating with the guy in the “donating to MIRI through you” project, you said no.

Later I read somewhere in a LW comment (maybe written by you, maybe not, I don’t remember) that the guy is a big MIRI donor. Evidence wasn’t included.

Based on this, I updated my estimate that this is a scam from 99% to about 70%. Maybe I should have updated further; I don’t know. I expected that things will later sort themselves out… either by someone reporting they successfully donated to MIRI using the proposal, or by someone reporting they got scammed… and as far as I know neither of this happened.

Is there any other publicly available evidence I missed?

I don’t know who he is, but he is not me.

I’m not “anon” either. In these columns, I am no-one but myself.

BTW, I don’t recognise your description of the postings I made about PCT, which were few and a long time ago, and unlike Mark’s empty hyping, did actually contain the ideas. (In saying this, I am not seeking a conversation on the subject, just putting down a marker.)

I dont understand how people see Mark and think Richard.

Ha, Ha, Ha

Anyways..

I heard you liked P.C.T. I have a psychotherapy book based on it. The creator was close friends with Will Powers. I can not figure out how his books have been neglected in P.C.T discussion. He has published plenty of papers on P.C.T and has alot of connections in the field. See for yourself.

https://books.google.ca/books?id=Da9lPEDayPMC&printsec=frontcover&source=gbs_ge_summary_r&cad=0#v=onepage&q&f=false

The book is free.

-If anyone still has yet to get the message Richard is not me.-

I knew Bill Powers myself for many years. (“Bill”, not “Will”, for those on first name terms, despite the opportunities for nominative determinism provided by the latter.)

However, although I’m somewhat familiar with the method of levels, there is nothing I can usefully say about the book, even at the risk of “pushing” it “hamhandedly”. I know nothing about psychotherapy and Scott is a professional practitioner. I’m aware that there have been studies on MoL, but I don’t know the results and have no references.

Hi Richard Kennaway,

Good point. I should post a link to some references and studies about M.O.L. They range from case studies too trials and can be found here. There are still plenty more from other researches that are floating the web.

http://www.methodoflevels.com.au/about-mol/

For more general P.C.T psychology:

http://www.pctweb.org/psy/psychology.html

Dr.Tim Carey has gotten back to me for every question ive ever asked. So if you have any questions/points I am certain he will answer back.

Ive also seen some P.C.T researches get in debates online. This one might be helpfull to look at and it shows what M.O.L looks like under a critical spotlight/rational inquiry.

http://psychsciencenotes.blogspot.ca/2016/01/a-quick-review-and-analysis-of.html?m=1

(Look at the comments section)

All right, sorry, that was uncalled for and my memories of that time are hazy.

No, it was exactly the right response.

It’s about Method of Levels, a therapeutical strategy based on perceptual control theory. After skimming the first few results of a Google Search i have to agree: this is important. Just understanding the concepts behind it made a lot of things click in my mind and raised my current level of happiness considerably, so it’s very relevant to this thread.

Ham-handed or not, it was very useful. Thank you!

You type like someone who’s extremely excited because they finally found an ebook with conclusive proof of the existence of Bigfoot which, if only people would read it, they would find impossible to deny.

If what’s behind that link is, in fact, a genuinely novel and groundbreaking psychotherapy method with demonstrated way-better-than-placebo-and-SSRI results in early clinical trials and it works in one month and it has a 0% relapse rate, etc etc, please consider spending an hour collecting your thoughts and writing something a little more informative and persuasive – I’d be interested in reading about something like that, obviously, but if I followed every link that came with recommendations like “I swear I’m not selling you anything” and “This will be one of the best books you have ever read” I wouldn’t have time to read slatestarcodex, let alone read the comments section and see your comment

e: I’m not meaning to just be rude by the way. It looks like you really do care about this new psychotherapy technique and if you plan on throwing out links to it and begging people to read about it, you might as well write up a nice quick intro to it so people have a reason to click your links other than “some guy on the internet says it’s amazing”

So, I guess I’m a little late to the party, but I thought I’d add, this was not one of the best books I’ve ever read. It wasn’t even rational. The key insight boils down to “it’s good to encourage clients to reflect (also, don’t be Freud)”, which is fine enough so far as it goes, but hopefully obvious to anyone who is even trying; and it loses some of its lustre when you try to wring a hundred and fifty pages of pseudoscientific formalism out of it. What’s more, this “perceptual control theory”, while basically no worse a formal model for cognition than all the others to which it is logically equivalent despite repeated claims of superiority (such as stimulus response, with respect to which the author has apparently failed to notice that ‘perception’ is a synonym of ‘stimulus’ and the ‘control’ action is, well, a response), is actually a really really unhealthy way to think about your own mind.

Interested in the last sentence, can you expand on that a bit? It seems like thinking of some of your sub processes as a bunch of little thermostats that try to keep things in some sort of homeostasis is a useful model and I can’t think what it harms. It reminds me of the law of equal and opposite advice.

I want to stress that I chose the words “way to think about your own mind” with some precision. It sounds like you’re talking about treating it as a flexible, intuitive characterisation, almost a gimmick – a sort of inverse personification you might use in some situations as an informal model.

That’s probably fine, as far as I can tell. I’m not sure it’s particularly useful.

Where I’m suggesting things could go astray is if you started to habitually think of your mind as working that way, not literally but perhaps the next thing over; I mean, if you start to believe that your brain is really closely approximated by one of those flowcharty PCT diagrams, the way the book strongly advises, you are going to damage yourself. The tendency to consider your mind abstractly as an integrated, fluid will is essential for it to function properly, and it seems to be possible to break that in ways that seriously impair your ability to introspect productively.

(If you would like some broad speculation as to why that happens, my theory is that it’s because it’s impossible for any finite system to specify its own state beyond a certain threshold granularity, as it always takes more degrees of freedom to store that information than exist in the system being described, which implies that it’s fundamentally impossible for any brain to understand itself very precisely, and you can run into that limit even if the model is inaccurate as long as it is sufficiently complex and granular.)

You can add degrees of freedom to your brain by simply using a computer… or a whiteboard 🙂

Ricardo: — which you would then need to include in order to fully specify the system, requiring more degrees of freedom to describe those too.

That’s like saying you cannot understand a computer because it can have a stupendous number of degrees of freedom. Maybe not infinite, but certainly more than you can fit in your brain. You don’t need to know every brain state to understand the brain. In fact, much incredible work as been accomplished in a short amount of time.

Exactly, because you can use abstractions. A brain can’t know its own state in detail, it can only have a vaguer impression that takes less information to specify. If you try to make the abstraction more granular, it becomes less useful and less accurate. Which is what I said to begin with.

I started reading the book. But it had a low signal to noise ratio. So I started skimming it progressively faster. There’s little in it that I couldn’t have gleaned from the wikipedia page. It reminds me of when I wanted to learn about the Flow once. So I borrowed a library book written by Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi and was disappointed to find nothing actionable. Anyhow.

* * *

MoL tl;dr

a) Go meta (aka self-reflection).

In the MoL book, the only actionable advice is basically “to figure out what’s bothering you, think on the meta level”. Which is (like CBT) excruciatingly obvious to the rational sphere, but perhaps not to the average Joe (or Scott’s attending physician).

On one hand, I feel this book is further confirmation that psychotherapists do nothing which a dialogue with a close friend couldn’t accomplish. Jim Carey and Will Powers are fully cognizant of this, as the book spends the first 20 or 30 pages explaining that psychotherapy is mostly a sham. Very similar to what our host has been preaching. Maybe psychotherapists serve a role that the pastor/shaman used to fill in more traditional communities. (Obligatory Szaszsz reference.)

On the other hand, I’m reminded of an occasion when a friend was distressed over a decision regarding a romantic relationship. Apparently, he had asked other friends for advice. And these friends had responded with unproductive cliches like “whatever happens was meant to be”. So maybe laypeople are not qualified to play psychotherapist after all.

On the third hand, he and I did eventually get to the bottom of things after an hour of metacognitive discourse, at which point his conflict was conclusively resolved. So at the end of the day, I dunno — should I count this anecdote as evidence that laypeople (like myself) are qualified to be psychotherapists? or should I count this as evidence that laypeople (like his other friends) do not have enough common sense to be psychotherapists.

* * *

PCT tl;dr

b) Feedback Loops are a thing.

c) Neural Networks are a thing.

To laymen, b) perhaps seems obvious. I think its value primarily lies in the fact that it’s a scholarly augmentation of B.F. Skinner. So when a friend is like “pavlovian conditioning”, you can respond “yeah. But actually… FEEDBACK LOOPS” then cite this book.

But again, maybe these sorts of common sense ideas really do need to be explicated with a 150-page e-book. I’m reminded of how Scott Aaronson once went to a conference regarding a certain cognitive theory that “consciousness = interconnectivity of a system”. He was the only speaker who offered criticism of the theory.

I admit I am intrigued by the relationship drawn by the book between error-correction and attention.

Also. The book reminds me of Kevin Simler’s review of The Bicameral Mind. In that they posit the existence of sub-agents trying to satisfy incompatible goals.

Hi FullMeta_Rationalist

Im glad you read the book. Good summary.

Tim Carey does repeat himself a few times for the sake of getting people to understand some very important ideas (he says this in the beginning of the book). The normal person/psychotherapist is unfamiliar with what he says.

Also as obvious as “going meta” is, it is rare that we actually do this when were in conflict. Most times we don’t even know were in conflict. Since you read the book im sure you heard about background thoughts/disruptions. These are very hard to catch by yourself.

Finally im glad you tested out M.O.L and hope you do it again. I hope doing this gives you an idea about how right/wrong M.O.L is.

Now for some questions;

1. Do you think the theory of M.O.L is right or wrong.

2. Do you think the future of psychotherapy and mental health care lies in the direction of M.O.L/P.C.T

3. Would you recommend the book to Starslatecodex.

To learn more about M.O.L here is a list of case studies and trails.

http://www.methodoflevels.com.au/about-mol/

Theres some other stuff just floating the web too.

*Also the site contains many videos of M.O.L in action. If you have any questions or criticisms of M.O.L/P.CT you can email Dr.Tim Carey at the site and I am certain he will get back.

Is this theory falsifiable in the Popperian sense?

Only sort of. The thing Gendlin’s Focusing, MoL and NLP have in common is that they state that *something* special occurs in psychotherapy that works vs psychotherapy that doesn’t across multiple schools of psychotherapy. If it turned out that there wasn’t a true invariant but rather it wound up being a smattering of different parameters (with maybe something like a threshold effect) that would be evidence against them. They might then retreat to the claim that there are one-three ingredients that tend to be outsized in effect. This is the more conservative claim that I think I agree with.

1.1) In case you’re asking whether I believe the mind is (to at least some degree) organized hierarchically.

Of course. Why wouldn’t it be? As far as I’m concerned, that’s the Null Hypothesis. Or at least it should be for any reductionist who’s put a modicum of thought into this. Possible alternative hypotheses include: the mind’s architecture is as flat as a pancake (we’re all nematodes); the mind’s architecture is a parallel forest of dissociative identities (we all have Mutliple Personality Disorder); the mind is a linear automata (BF Skinner); the mind is an incorporeal monoid (Dualism).

To paraphrase Lumifer, exactly in what way is this theory falsifiable? In order to interest me, the claim is going to have to be a little more specific. Which the book does take a stab at during page xii, but then handwaves away the onus probandi with “Just for the record and without getting further into details (…)”.

1.2) In case you’re asking whether I believe the technique is useful.

I mean, it’s certainly better than “whatever happens is destiny”. However, it fits my Hollywood stereotype of what psychotherapists do already. Maybe you’ve seen Freaky Friday, that movie where a control-freak single-mother and an angsty teenage daughter involuntarily switch bodies. The mom is a professional therapist. Which means Lindsey Lohan has to pretend to be a therapist. So the mom is like “just say keep saying ‘and how do you feel about that?'”. Like, could this not be classified as MoL?

I guess the source of frustration is that psychotherapy must continue to point towards trivial, low-hanging fruit while a large swath of the population (including the professionals) continually and adamantly bark at a scarecrow. In other news, I think I now know what it feels like to be Alan Kay.

2) I’m no psychotherapist. So I don’t have enough information to make a confident prediction. Most of my psychology opinions are formed through the lens of our caliph, Scott. So whatever opinion I come up with will probably just be a proxy for his opinion.

That said. Until psychology finds something genuinely novel, psychotherapy should probably just stay the course. E.g. self-reflection, the hostessing of salarymen, and the injection of metaphorical-lithium into the water supply.

3) Would not recommend. Instead, I recommend a 10-minute safari through the PCT wikipedia page.

I read (most of) the Wikipedia article on PCT.

– A car cruise control system is a piece of unthinking matter. Each segment of the loop affects the next by pure physical determinism. Intentionality, and therefore control, can only be attributed because we know that the system was designed by a human engineer. The engineer wanted the system to control the car’s speed and it does, therefore what it controls is the car’s speed. Not perception (the readout of the car’s speed), nor behavior (the opening of the gas), but a piece of reality. Alternatively, one may focus on direct causality and say that the system controls the opening of the gas (behavior), with the goal of controlling the car’s speed. What nobody says is that the system controls the readout, because that’s retarded.

– Therefore, the whole diatribe about “controlling perception, not behavior” is completely unnecessary and a waste of everyone’s time. The terminology was arbitrarily picked to maximize the impression of surprise and counterintuitiveness. It’s clickbait, essentially.

– What if there is no loop? For example, I am flexing my biceps right now. Assuming the PCT model, I am changing the reference point, and the motor neurons are firing, but the loop is not closing. The arm is not moving, no angle is changing, and the feedback stimulus does not move any closer to the reference point. The neurons are going to keep firing in vain as long as I will it (or until I get tired). My arm control system is clearly not controlling its perception of the arm’s state: how can something be said to control something else when it has no effect on it? All it is controlling is the contraction of the muscles, i.e. behavior.

– The notion that matching the behavior implies that you have matched the internal structure is completely wrong.

That used to be the case—then some fucking idiot decided to put a computer in the loop.

What evidence is there that these changes are real, and not just changes in how people report their levels of happiness? It seems plausible to me that cultural differences — varying across both geography and time — could cause a lot of variation in the level of happiness reported on some 1-10 scale even if the actual levels of happiness remained unchanged. It’s not clear to me how you would separate that kind of thing from the presumed “true” underlying happiness level.

That’s exactly what I was thinking. Chinese people probably think about happiness in a much different way than Americans. We can’t really trust any of the data, and probably won’t be able to until we can solve the hard problem of consciousness. But of course, we would like to something until then. Is there any other way we can try to measure happiness? What if we look directly at the brain?

“What if we look directly at the brain?”

Sure, we could use fMRI! Oh wait, never mind.

Hah! Funny, but depressing. For anybody who hasn’t heard about it: http://www.theregister.co.uk/2016/07/03/mri_software_bugs_could_upend_years_of_research/

http://blogs.discovermagazine.com/neuroskeptic/2016/07/07/false-positive-fmri-mainstream/#.V5Fws_krLIV

Some questions about how serious the problem actually is….

It looks as though it would help if someone looked at how much is based on the unreliable fMRI scans, rather than just counting things.

Oh good, something to do with all that salmon in the fridge.

One specific thing: a large part of contemporary Facebook Meme Feminism is the “don’t tell me to smile” variety. This suggests that there was and is more pressure on women than on men to present themselves as cheerful, and that an aspect of some varieties of feminism is resisting that pressure.

Considering that if you look at the Language Log articles what you’ve got is “a shift of a few percentage points, mostly accomplished by shifting the opinions of around 5 women in a hundred from “very happy” to “pretty happy””, it seems plausible that something like that may be confounding things. (If you look at their graphs, the phrase “lost in the noise” springs to mind).

Just in case anyone is wondering, I’ve had strangers on the street tell me to smile. Snapping at them cheered me up amazingly. I’m not sure that seeing their faces fall was an essential part of the experience, but it certainly didn’t hurt (me).

I’ve told men to smile and that cheered us both up. I think there is some selection bias operating in the trope that women are hectored excessively to smile.

I’m a man and I’ve been told to smile in the street a total of one time in my life. I found it fairly off-putting, and the idea of getting that treatment frequently boils my blood.

I don’t know what the actual frequency of this for men vs. women is. I’ve only ever asked one (very conventionally attractive) female friend about this, and she said that she hadn’t even realized this was a thing, but that she always smiles when she passes strangers anyway. Still, a trend of telling women to smile seems very compatible with traditional gender dynamics as I understand them, whereas a trend of telling men to smile does not.

I completely agree that Peter’s idea seems plausible. I’d like to point out that the flip side of this phenomenon is that women today are more likely to be told that they should be upset and feel oppressed wherever gender is concerned. This may be contributing to lower level of reported happiness.

(Or maybe I’m just pulling this out of my ass. I wasn’t alive during the 1970’s, during which I’m sure the feminism movement was at least as vigorous as it is today, although its flavor was obviously very different. But I imagine the general vibe of the early 70’s to be “we’ve been oppressed, but now we’re getting liberated!”, while the sentiment of today’s online feminism seems rather less positive.)

I’m just one data point, but an area where feminism has made my life emotionally worse is talk about women pedestrians giving way too much to men. Some of them talk about just not giving way at all until they bump into men.

I don’t know whether I’m mostly giving way. I don’t know what I’d rather do.

If I care, what I should probably do is spend a while observing before I try to change anything.

What has actually happened is feeling as though I’m obliged to make a decision about my sidewalk behavior, and it makes the mere sight of a man in my path of travel infuriating, and I don’t mean I’m angry at him, I mean I’m angry at feminists who’ve made just walking in a city much more work than it was.

At this point, I’ve dropped any concern about the issue because I think it’s more trouble than it’s worth.

I imagine that recent feminist activism against “manspreading” on subways has had a similar effect on some women who live in big cities.

Possibly, but the difference I see is that taking up more than one subway seat is well-defined, while how much giving way is polite isn’t.

Any kind of thinking about or awareness of how you walk down the street will make your life worse, I find. Once you start thinking about it you disrupt the unconscious process.

In Impro there’s a great analysis of this whole thing; actually that book has the best analysis of status in human behaviour I’ve ever seen. It’s not just gender. Low status people give way to higher status ones. Men are higher status in our culture so women end up giving way to men quite often, but there are other components to this; age vs youth is a big one. Elderly Germans will mow you down in their path because older people are high-status in Germany.

It was extremely enlightening. But it made walking down the street really suck. I kept bumping in to people because I was thinking about it too much.

This was my thinking, as well. If someone conducting a poll asked me if I’m happy, I’d probably pause to contemplate the question long enough that they’d get frustrated and end the conversation. And maybe eventually answer, “I don’t know, how do I know?” or something otherwise potentially ridiculous, potentially true, potentially both.

“a gradual thirty-year improvement in living standards”

A twenty-fold increase in real income over thirty years (roughly the Chinese experience, I believe) is not gradual.

The first time I visited China was 2002. The second time 2008. It was almost unrecognizable. And I’m sure people who visited in the 80s and 90s would have said the same about 2002 China. I joke that China is like a puppy–every time you see it it’s completely different.

That said, it probably feels more gradual when you’re living it–but Chinese people have the same impression. I have a friend in his 30s who grew up in a small town. He says his hometown is completely different from his childhood memories of it.

Economically, 1 China year is like 3 regular years.

I’m betting the gender imbalance that appeared in China due to sex selecting abortions was enough to blow away any economic gains among men. (Not being able to get a date should probably affect happiness.) But unless I look at changing gender ratios and happiness rates among men and women, that’s just a guess.

Also the Chinese people I know say that economic boom mostly hit the cities, not the rural areas. Could that affect things?

56% of the population of China lives in cities, so unless rural people are significantly worse off, you’d still expect to see positive changes.

Measuring happiness is really hard, it turns out. Slight changes in wording, translation differences, and linguistic and cultural drift make results unreliable. As a sort-of control, poll people on how healthy they are, which there are at least objective proxies for; iirc, people also do not generally report being healthier than in the past.

That’s like saying lets just measure how wealthy people are. That gives us better data but it’s not answering our question.

I think Tedd meant something else. Suppose that people report the same level of health as 50 years ago — but you know that their life expectancy and quality has risen by looking at objective data. Then you know that there is something very problematic with self-reporting.

Another possibility is that you will find a certain bias in how people self-report bias and you could, presumably and arguably, make the case that you can use this bias of known magnitude to correct for the (assumed) bias in happiness reports.

So yeah, not bullet proof, but also, not useless.

The first paragraph was indeed what I meant.

Which is what exactly? “Happiness” does not have an agreed upon meaning. How can you measure something when you don’t even know what it is you are measuring? One way to deal with this common problem in the social sciences is to use an operational definition. An operational definition of happiness would at least give us an unambiguous, if limited, meaning of term.

My general rule of thumb is that if you cannot assign a unit of measure to your dependent variable then you are are not doing science.

I also think that when people are asked “rate on a 10 point scale how happy you are” they answer a simpler question, which is comparing their happiness to hours. After all, we go around thinking “my job sucks” and not “I feel 4/10 happy today”. This means that people can become massively happier, in general and minute-to-minute, and yet report little-changed numbers on surveys.

The entire idea of happiness seems so noisy as to be a useless concept, as far as quantitative measurement is concerned. Like i would expect the effect from asking questions in the morning or evening, before after dinner, before after a smoke, to be considerably higher that almost any macro level change (ie poor/rich, healthy/unhealthy, free/unfree) the only exception would be be things so big and culturally present that it affects the answer your EXPECTED to give. For example you’d feel bad and conflicted telling white survey takers that you where happy if you were black in the civil rights era, or telling the international community you were happy if you were in the midst of the Syrian civil war.

So for a few culturally high profile things the “right” answer is expected of you, and any other thing (long term trends ect.) will be drowned out by how close you are to your smoke break.

It reminds me of the pain scale used in hospitals.

There’s an improved version of the hospital pain scale; I don’t know how widely it’s used.

I thought the 80’s onward was when the stagnation of middle class incomes started in the US — so why did happiness rise then after falling when people were doing better?

No Vietnam war and people felt more confident about the Cold War?

No, the stagnation begins in the early 70s, I believe (depending on measurement).

Additionally, the 1970s, and early 80s, had several nasty recessions, along with the OPEC Oil Crisis, along with stagflation.

The 1980s has a big return to stability. Also, since more women enter the workforce, the family feels richer (even if median hourly wages stagnate).

The late 1990s was a good time for worker wages, too.

Contrary to all the “Reagan and Thatcher ruined everything” talk you hear in academia, the 80s and 90s, and especially the Reagan years, were years of high satisfaction and optimism among most people in the US. Reagan did win 49 states in 84, after all. Can one even imagine that level of satisfaction with any president today?

Also its only median wage that’s stagnant (and then only in the states), total expense on employee has gone up (your healthplan is way better today than the 80s), tech has improved dramatically (it used to be you’d have to read academic articles to have conversations like this), and buying power has improved (i remember my mom telling me that when she got rid of her old junker car she was able to just buy a new pair of boots, now you could buy 5 pairs of boots just for the price of the scrap metal). THe quality of everything has improved dramatically as well as the variety (there would have been barely one sushi place in my city in the 80s that produced sushi as good as my discount sushi place) Additionally median wage is probably skewed by more irregular working arrangements (again more options), household income, the thing that actually determines how wealthy you and the world around you are likely to be, has never stopped growing.

Stagnation started in 1975.

The oil shocks were over, for one:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/1973_oil_crisis

Not being forced to get gas only on even or odd number days helped. Also, the 1980s heralded the explosion of information technologies-cable TV, computing, home recording, affordable personal electronics.

In retrospect, rationing by even- or odd-numbers was really dumb. The whole thing was caused by price controls. These days, we just let gas prices rise and there is always enough gas (with a few exceptions).

There are occasional calls to go back to stupid policies like that. Trump and Sanders would both easily back a plan like that because it’s easy to get the populists to encourage it in the short term.

Has anyone looked in to whether the people doing these surveys have looked in to cultural differences and ways around it? Surely they must have thought of that.

Even if Mexicans are culturally predisposed to say they’re happy more than Japanese, presumably the culture surrounding talking about happiness in Mexico and Japan didn’t change dramatically over a 30 year period, so we can still compare the change?

My concern is that self-reported happiness probably correlates more strongly with an intellectual sense of whether things are going well or not, as opposed to daily lived experience, and that that has a lot to do with the media, actually.

I wouldn’t be surprised to find black happiness dropping dramatically very recently because all the news reports are about how, if you’re black, policemen will just shoot you for no reason. The likelihood of being shot by a policeman for a black person has probably actually gone down recently (due to scandal-wary police), but awareness of the possibility has gone up, and that’s what matters for something like self-reported happiness.

Can we presume that? Based on my observations of culture and history, I think it’s pretty clear the culture surrounding talking about emotions generally changed noticeably in the US between, e.g., 1945 and 1975. (Between 1965 and 1975, for that matter.)

I don’t know enough about Japan or Mexico to have an informed opinion, but Japan at least seems to have undergone noticeable cultural changes in the last generation.

I’ve seen a couple of things by black men who’d been taught that they’d be safe from the police if they were very respectful and compliant. They were horrified to find that the strategy they believed in wasn’t good enough.

It’s not completely fool-proof but it’s pretty damn good. Also the same thing goes for all races.

I am somewhat curious how you define “Safe from the police”.

If you find yourself in circumstances where the police has a reason to suspect you of a crime, you will obviously be treated accordingly, but being compliant and respectful will make the process less unpleasant.

I don’t see how that is dependent on race, perhaps with the exception that black men may find themselves in such circumstances more often than other demographics.

The BLM narrative is that police are exclusively or at least extremely predominately a threat to black people; that white people are safe around police and furthermore aren’t and don’t need to be taught to act deferential towards them.

The first part is false; if police are racist in their killing it is not to the extent that a black man must rationally feel mortal fear around them but a white man should rationally feel safe.

The second part is laughably false.

http://www.nbcnews.com/news/us-news/cops-shoot-unarmed-caregiver-charles-kinsey-his-hands-while-he-n614106

I consider it relevant that black people seemed to be generally more afraid of police before the videos came out. It’s something people could be wrong about (including that black people might be appropriately afraid while white people are too trusting), but it’s reasonable that people would have pretty good (mostly local) information through their experience and social networks.

Why do you start by assuming that police don’t abuse their power?

Your linked article was interesting, but I don’t see how it proves anything beyond police officers being able to feel stress and act rashly under said stress which is a problem other than racism. (And one that I believe most police forces are working on to the best of their ability.)

I start by assuming that police are sadly lacking in power to abuse, which is almost the same, but not quite.

The police are operating on uncertain and often flawed information, in a stressful and potentially dangerous situation. They have to make split-second judgement calls that are later scrutinised by investigation teams that have never been in a similar situation and have all the time in the world to mull over details. This is not an enviable position to be in.

Frankly, I’m amazed things don’t go wrong more often than they do and believe the west is blessed with police forces that are much more competent than we have any right to expect, given what we pay them.

The reason I am willing to extend a certain slack to the police is mostly from personal experience. I have not been a police officer, but I have been in combat situations and will use that as a gauge for what is reasonable behaviour on the part of the police.

I have also had the misfortune to be arrested on a few occasions and I will summarise the most dramatic of these incidents here as an example:

I was sitting in my car idly wondering what was holding up traffic when the answer came in the form of a SWAT team descending on my vehicle. This would not have made my top ten list of possible reasons for a traffic jam before the event. I remained silent, compliant and calm during the arrest. The silent bit is more important than you might think; speaking when not spoken to in a stressful situation only adds to the stress. I was roughed up some, enough to require stitches, but not shot.

During interrogation, it turned out the police were acting on credible but ultimately flawed information that I was a terrorist about to set off a dirty bomb in a major city. (this was not long after 9/11 so the paranoia factor was high) Given their information, I would not have held it against them if they had shot me, as from their perspective it would have been a perfectly reasonable thing to do, especially if they felt they were losing control of the situation. (which I did my best to prevent by said calmness and compliance)

After 48 rather unpleasant hours while they cleared up the misunderstanding, I took the arresting team out to the pub for a few drinks. This was appreciated.

After this, do I consider myself “safe” from the police? Yes. Do I consider myself safe from paranoid nutjobs who report suspected terrorism? Not really, but I’m not sure if anything can be done about that.

From my perspective, the main difference between my experience and the ones related in the media these days seems to be that I am not angry about it.

Edit: all these meandering paragraphs were essentially just to say that the bar that police should meet is:

Given the information available at the time, and the time allowed for deliberation (typically .1 sec), is this a mistake I could be absolutely certain I would not have made myself?

All the evidence I have seen tells me that the police are usually better than me, so who am I to complain?

@Nybbler

Of course those narratives are false. You made them up.

I’m dubious about those “haven’t been there” arguments, since you can usually find people who have been there on both sides of a disagreement.

@ Richard

Imagine yourself interacting with someone who’s in foul mood and you’re are a bit cheeky and not terribly respectful (though not rude).

Now compare the case when that someone is a cop and when that someone is, say, a municipal clerk.

Should anyone rationally feel ‘safe’ to be disrespectful and cheeky to someone in a high risk and high stress job and whose contact with the public is often (although not always) dealing with the worst and most dangerous people in the community? And whose job sometimes (although not often) sees them facing legitimate threats to their life and limb from said members of the community?

@ Dahl

Yes, anyone should feel safe in the presence of a public servant paid out of his taxes.

If the said public servant cannot differentiate between cheeky and threatening, he doesn’t look to be qualified for the job.,

On the other hand, people should not be going about being cheeky and disrespectful to strangers of any stripe, on account of its being rude.

Certainly, in the same sense that a virgin with a bag of gold about her neck should be able to walk naked across the realm, safe and unmolested.

Very nice as an aspirational goal or a moral demand. In any actual human society, virgins are advised to go clothed and keep their bags of gold hidden even though they “shouldn’t have to”.

Richard,

The police are not lacking in power to abuse. They have the power to commit violence on anyone who is not a member of the political elite, with impunity; the entire system will back them up. The scrutiny they receive after such violence … well, the line from the Declaration of Independence about protecting them by means of mock trials comes to mind.

And most (white) people are perfectly OK with this. Look at you; you were as compliant and deferent as any tyrant could demand, and your encounter with police STILL resulted in injury great enough to require stitches. And you’re OK with that, and bought your abusers beer afterwards. That’s something akin to Stockholm Syndrome, if not the thing itself.

Lumifer

So you think it’s rational to expect that any member of the public can at any time approach someone in one of the highest risk, highest stress jobs in modern society, and be cheeky and disrespectful (while having no awareness of whether said public servant has just had an altercation with someone carrying a knife, or has just intervened in a domestic safety matter where they were responsible for physically removing a child from dangerous parents for instance or more stressful things) and the public servant should be able to guess why you are approaching in such a manner and, using their famed ‘public servant perfect insight’ (PSPI – such a common term i should really start using this acronym), respond in such a way as for any and all members of the public to feel nothing less than safe in doing so.

And all this because people pay tax? And the public servant is paid a salary from this tax?

Is that fair? Or is there some more moderate version of this story that better fits?

@ Mary

Let’s try this again with better reading comprehension skills. I said:

@ John Schilling

Right, and what do we do to people who grab the bag of gold with one hand and the virgin’s ass with another? Do we tell them “Oh, it was all her fault, you’re good to go”?

@ Dahl

I’m not talking about rational expectations. I’m talking about rights. I would like to think that I have right not to be beaten, tazed, pepper-sprayed, and on occassion shot without either seriously breaking the law or being an imminent threat.

If you believe I do not have such rights, well, we have a serious disagreement about the type of society we live in.

At a small tangent …

Much discussion of these issues assumes that being a policeman is a very dangerous job.

It isn’t. The death rate for policemen is about thirteen per hundred thousand. The rate for loggers is about ten times as high. For construction workers, about half again as high.

To put it differently, the probability of being killed if you are a police officer, from any cause including accidents, is only about three times as high as the probability of being murdered for a random American.

Last I looked, US law enforcement wasn’t even the US civilian job with the highest risk of death from intentional injury; iirc bartenders and taxi drivers rank higher. For all on-job risks of death it’s not even in the top 10.

Generally, we put those people in jail… when we have proof beyond a reasonable doubt that they committed the elements of the crime, with appropriate mens rea, within the jurisdiction of the prosecuting authority, supposing they’ve been provided competent legal defense (and probably a few other conditions).

Sometimes, we might not be able to have all of those things. Your choices are not, “Never prosecute wrongdoing,” and, “Utopia where nobody even tries to break the rules.” You have to select a level of proof and civil liberties to work with and accept that there will be people who still try to do bad things and get away with them. John’s point that you’re asking for a fundamental internal moral change in the entire population rather than any particular legal or policy adjustment stands.

Right, and what do we do to people who grab the bag of gold with one hand and the virgin’s ass with another? Do we tell them “Oh, it was all her fault, you’re good to go”?

Typically we have a hard time finding them to do anything at all.

What we don’t do, is imagine this is a sign of intolerable social decay or as a grave national problem whose solution must be a top priority. Every society accepts some type and level of criminal violence(*) on the grounds of “shit happens” and “yes you really were asking for it”, punishing specific offenders iff they can be positively identified but otherwise moving on.

People may legitimately disagree with where the line is drawn, but if you’re anywhere in the gray area and demanding that all right-thinking people must side with you, that’s just tribal signaling.

*Yes, including criminal violence by policemen

But how should the other 47% feel?

Let’s try this again with better reading comprehension skills. I said:

and you’re are a bit cheeky and not terribly respectful (though not rude)

And I deny it. You can not be cheeky and disrespectful without being rude.

The problem is not reading comprehension, it’s the delusion that people aren’t being rude when people are.

That’s obviously a joke, but unless you’re committing a crime inside of a federal building or on a military installation, the police are not paid by federal income taxes.

If all you care about is happiness, then, logically, you should find a way to wirehead yourself as soon as possible — since wireheading maximizes your happiness.

If that prospect doesn’t sound appealing, then either happiness doesn’t matter to you, or perhaps it does, but there’s something else that matters more. This preference for things other than happiness may or may not be rational (I personally don’t know of any good arguments against wireheading), but nonetheless, most likely is there.

If we grant that such preference exists, then the happiness paradox is no longer a paradox. Sure, women are less happy in modern societies; but perhaps they value something else, such as being able to make their own choices, more than they value merely feeling good as much as possible (though, again, such preferences may be irrational).

Are you sure wireheads are happy?

Look like Yvain solved his procrastination problem somehow.

Scheduling is a hell of a drug.

Do elaborate.

I have tried a couple times now to schedule, and it worked for a couple days, but then i forget to one morning/evening and its right back to slovenly student. Any resources you recommend or helpful advice?

I’m slightly confused. It was working, then you forgot 1 day, and it’s ruined forever? Why not just schedule the next day? If you can do 3/4 days scheduled, that’s pretty good right? And you’ll probably get better as you get more used to scheduling. Is this like the “To hell with it” fallacy, where people eat a cupcake so declare their diet ruined and order a large pizza? (I think it was called “Failing with abandon” somewhere on LW)

It is amazing what falling off for one day can do for your willingness to get back on track.

To be fair as an jobless student on summer-break completing online courses, my life doesn’t really have a natural schedule to it. I imagine if their were already a few large sections blocked off on my schedule, and i was reliably waking up in the same place scheduling would be easier.

Any thoughts?

Is a consistent routine necessary for effective scheduling/organization? Or have you found a way around it? Have you Found anyways to effectively maintain a routine? Do you run your morning like a pilot going over his pre-flight check-list? Any general organization tricks?

This is a very interesting phenomenon I have experienced: the thing you really enjoy whenever you do it, yet somehow still have trouble finding the energy to do. This applies, for me, to much of my work, and even, weirdly, sometimes, to sex. Never to eating, however, sadly…

Yes. Whiteheads experience the maximum amount of pleasure that it is possible for a human to experience. At all times. Forever. If that prospect does not appeal to you, then it must mean that you are willing to trade off happiness for something else.

Er, I meant “Wireheads”, looks like I got autocorrected…

I figured it out, but I really enjoyed the literal meaning.

So… it’s like this but with reversed sign?

If all you care about is your own happiness yes. If you care about happiness in general, then you need to stay lucid so you can wirehead the universe.

In this case, you would be one of those people who is responsible for the “happiness paradox”, so my point stands. That is, if someone were to poll you and ask if you’re happy, you’d say, “no, despite all the new advances in technology and medicine I failed to reach my goal of increasing universal happiness by 1%/year” or something.

This doesn’t follow– wireheading might not maximize expected value for an agent even if happiness is given more weight than any other term in the agent’s valuation function. This could be because the agent is already extremely happy, and the small increment in happiness she’ll get from wireheading will be outweighed by much larger decrements in the other terms, or it could be because the other terms individually matter less than happiness but jointly matter more. The strongest claim you can make is that agents who only value (their own) happiness or who assign (their own) happiness lexical priority over all other values should wirehead themselves, but even this depends on the dubious identification of hedonistic pleasure with happiness.

I’m not sure what the difference is between “hedonistic pleasure”, “happiness”, and other kinds of pleasure (assuming they exist at all). Your point about diminishing returns from increased happiness is completely valid, but I don’t think it applies to our current scenario — i.e., I don’t think that humans are already that close to being maximally happy. I could be wrong, though.

The more reason not to conflate them.

Wireheading imposes such catastrophic costs on other domains of human flourishing that it probably won’t be advisable unless your life is currently pretty joyless. If you value autonomy, authenticity, human relationships, accomplishing life goals, etc. even a little bit, you’re going to need a huge boost in happiness to compensate for their erasure. So wireheading will be a good idea only if you’re already miserable or care exclusively about pleasure, just as we would naively expect.

Right, but if you value “autonomy, authenticity, human relationships, accomplishing life goals, etc.” more than happiness, then we would expect exactly the same picture as the one we’re seeing — quality of life improves, but happiness either remains the same or improves only marginally.

That said though, I am honestly not sure what it would mean to value anything more strongly than maximum continuous pleasure (as obtainable through wireheading). I don’t think any satisfaction from accomplishing life goals could compete with that…

That was not the claim. Here, to make this more concrete, let’s plug in some numbers. Pretend that everything Tim values can be measured on a neat interval scale and model the “quantity” of each item of value in Tim’s life as a real number over the unit interval. Assume also that Tim values pleasure five times as much as each of autonomy, authenticity, human relationships, and accomplishing life goals, and that he values nothing else. Note that this means that Tim values pleasure more than everything else combined. Here is his life before wireheading:

Autonomy: .9

Authenticity: .9

Human Relationships: .8

Accomplishing Life Goals: .7

Pleasure: .4

And here, presumably, is how the distribution will look after Tim is wireheaded:

Autonomy: 0

Authenticity: 0

Human relationships: 0

Accomplishing life goals: 0

Pleasure: 1

Given the stipulations above, Tim is better off not being wireheaded. He gains .6 points of pleasure, but he loses the equivalent of ~.61 points of pleasure on the other dimensions of value.

So, to reiterate: wireheading is probably only a good idea if your life is already thoroughly miserable or you accept some form of hedonist monism. If the former, though, there are other interventions that will leave you better off overall than wireheading, and you should focus on those instead. Which means that the possibility of wireheading serves principally as an argument against hedonist monism.

There is a difference between pleasure and happiness. Pleasure is a jolt of reward, probably mostly related to dopamine, you get when you do something which furthers an evolutionary goal–eat fattening food, have an orgasm.

Happiness is a general sense, probably more related to serotonin, that things are going well–that you are on track to have a fulfilling life, which will probably include a lot of pleasure, but which isn’t necessarily defined by pleasure. You may feel happiness when playing catch with your child on a nice day or something, but not “pleasure” (actually, we might find that kind of gross/weird if you did).

Drug addicts typically experience a lot of pleasure–probably more pleasure than is possible to experience without heroine or cocaine. Yet they often don’t experience much happiness. Long run, most people consider happiness more important than pleasure, perhaps because it is more lasting and feels more “real” in some sense.

The problem with wireheading is that it eschews happiness in favor of pure pleasure, though taking away the negative health impact of drugs would still be nice, for certain.

Personally, the best way to think about happiness I’ve come up with is “score”. Happiness is your reward for being successful at this life thing, but isn’t the substance of the success – just like being able to set your score at INT_MAX is not the same as being good at whatever game you’re playing (you’re just a cheater, or highly resistant to ennui of pressing a button repeatedly for days on end).

I agree that “people value other things than happiness” is definitely part of it. Happiness is obviously very important to people, but it’s not the only important thing.

The question is, how much of the people failing to find happiness is due to people not seeking out happiness, and how much of it is due to people being systematically mistaken about what makes them happy? I think that there’s definitely some of both. People in our society often complain that they are not happy, and people who are professionally successful often complain that this success does not translate into happiness. Movies like “Hook,” “Liar Liar,” and “Jingle All the Way” all have a message that professional success does not lead to happiness in the same way that having a family does, that message must resonate with audiences.

So while I agree that happiness isn’t the only valuable thing, I don’t think that “people pursuing other stuff besides happiness” is the only explanation for why happiness isn’t higher. I think that a large part of it is that people are systematically mistaken about how to be happy (in particular they participate in the Rat Race more than they should), and that policies that make it more difficult for people to follow their biases should be made.

One thing I wonder about in the traditional vs. modern cultures and women vs. men’s happiness is total household leisure time. I could find a bunch of research about individual free time, and this showed a small increase in the last half-century. In the meantime, there was a huge shift towards dual-income households. It may be possible that a modern culture has fewer hours of leisure time as a household unit, even though the data for individuals shows a small increase.

Edit:

Also household discretionary income has decreased since the 1970s (http://harvardmagazine.com/2006/01/the-middle-class-on-the-html). I think there may be something to a modern culture living too close to the margin to be relaxed enough to mark down that they are really happy on one of these surveys.

One thing to think about is that (say) 20% of the Chinese living today would have been dead under the conditions of (say) 30 years ago.

You could imagine adjusting the old data for that by adding 25% dead people as “really unhappy”. Or are they blissfully devoid of unhappiness?

I don’t have the answer, just want to point out another way this is hard to sort out.

Most utilitarians I know rank dead people as perfectly neutral, neither happy, nor unhappy. It’s better to be happy than dead, but better to be dead than to be unhappy (though it is still good for an unhappy person to be alive if they will stop being unhappy and become happy at some point in the future).

Well, that’s very different from my preferences, even when I’m unhappy. Don’t kill me and think you did me a favor!

I’m pretty sceptical that any purported measure of happiness functions correctly in any case, but, notwithstanding that, none of these examples conflict with Sumner’s thesis. In fact, they describe situations where it seems entirely plausible that happiness changed only because standards for what qualifies as normal changed. For example, the increase in black happiness in the US and all the cases mentioned later under the freedom-and-democracy category might be explained by a recalibration among the relevant people from judging by the better-off to judging by their peers. It doesn’t necessarily matter if the peer group’s status even improves at all in the process, which could be troubling. It’s probably a good idea to give this possibility more consideration.

Editing to add that the same can be applied to women, many of whom have probably expanded their comparison groups from including mainly other women to including the men they are now competing against economically.

An increase in black happiness does not necessarily contradict the hypothesis that happiness is zero sum or a product of how you view yourself relative to others.

This was my exact thought until Scott got to the decade-by-decade analysis later on – if status is a Positional Good, and black people have gained status since the 1970es (which I think is pretty incontrovertible?) then somebody else must have lost it. Did people talk about Hispanics as if they were a different race back then? Was Appalachia the same kind of devastatingly poor?

“if status is a Positional Good, and black people have gained status since the 1970es (which I think is pretty incontrovertible?) then somebody else must have lost it.”

Recall that the Republican nominee is currently running on a platform of dogwhistles to the effect of “white men are no longer in charge of the country and that’s terrible.”

Oh you sweet summer child.

Alternatively, you could present a counterargument

Okay, my counterargument is that he is not currently running on such a platform

Dogwhistles. sigh

The theory that people who don’t agree with you have hidden secret messages in their speech that you have the key to decode and that reveal them to be monsters of wickedness — is normally diagnosed as clinical paranoia.

We had a whole post on dog whistles a while back. The idea that Trump would be using them seems unlikely; Trump whistles can be heard by all.

The Southern Strategy isn’t a paranoid delusion. It’s documented history.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Southern_strategy

So what? We’re not discussing history but the current day.

Appalachia was certainly still poor as dirt, though I think widespread meth is relatively new (alcoholism isn’t). Hispanics were considered separate though I think the name may have been different.

As Wirehead Wannabee points out above, the obvious candidate for ‘status lost’ is your working class white man, your Archie Bunker types.

During the seventies Appalachian coal boom? I doubt it. According to The Economic Impact of the Coal Boom and Bust (pdf) it seems Appalachia in the 70s was more like the midwestern oil boom-towns of a few years ago. The massive poverty came with the coal collapse in the latter half of the 1980s

I don’t know if India is a spoiler here, but has anyone considered that reporting you were really unhappy to be living in China while it was being run by Chairman Mao might be the kind of thing that you didn’t do if you wanted to live a long and prosperous life, that there was a pervasive atmosphere of paranoia after the Cultural Revolution, and that the numbers in China might just be going down because they were artificially inflated in the past?

The survey is said to have begun around 1990, 14 years after Mao’s death.

People were still paranoid about state monitoring in the 90s and continue to be so to some extent even to this day.

A good point. 1990 was during the post-Tiananmen chill of 1989-1992, when the emergence of pluralism in the post-Mao years ground to a screeching halt.

Likewise, Taiwan’s democracy was still unstable at the time and people were used to KMT police state rule.

By contrast, 2010 was the height of the Hu Jintao era of political complacency and Taiwan had become pretty used to democracy by then (not to mention mired in an endless recession).

I agree with several other commenters that survey responses to a question about happiness seem like a poor proxy for measuring actual happiness. If you had asked me to rate my happiness on a 1–10 scale on a randomly chosen day last month, there are days I would have said “7” and days I would have said “3”, despite very little about my life having changed in any way over the course of the month.

Of course, I don’t have a suggestion for how to measure happiness that is better than asking people for a number…

Here is a brief defence of the meaningful nature of the data – it’s absolutely sensitive to stupid stuff, like the weather, but for large samples with good survey practice most of that seems to wash out. Systematic cultural bias and, particularly, people moving the goalposts for what constitutes a “7” are much bigger problems, though.

hmmm. . . I wonder. . .

There were some studies that turned out to be missing a cofactor. That, in fact, happiness was correlated with many good things because it was also correlated with regarding your life as meaningful, which had a better correlation with the good things.

But I’m not sure it’s this one.

One key point when looking at happiness/SWB data (well, I wrote my PhD thesis on this issue, so I think it’s important at least) is that it’s generally ordinal data and doesn’t aggregate properly or produce good measures of central tendency. So you’re stuck either using an arbitrary binary (“very happy”/”not very happy”) scale, like the chart above, or you just shrug your shoulders and pretend you’ve got interval/ratio scale data without any evidence to justify the assumption – this, more or less, was what that recent study on parental happiness as a function of national social policy did.*

One of those approaches is flat wrong, but the other can conceal a lot of important differences between states of the world. A high proportion of “very happy” probably correlates to higher overall national happiness/utility, but it doesn’t necessarily imply it, even if you’re assuming a constant mapping from underlying utility to the reported scale… Ideally you need to map the responses to an interval scale and then derive national/temporal averages, just as a starting point for these discussions.

That thesis sounds interesting. Is it available on-line anywhere?

Hi Alan,

Available here – the technical material on aggregation and a suggested approach to cardinalising the data is the back half of chapter two – the non-technical discussion is in chapter one.

The link didn’t take – I’ll try again:

It looks as though the spam filter is very hungry and has eaten both your link attempts 🙁

Odd. You can google it using my name and “SWB”

Google didn’t find it, but Duck Duck Go worked. https://ses.library.usyd.edu.au/handle/2123/10413

Then, using the title

“Subjective wellbeing, mean reversion and risk” instead of SWB gets Google to play nice 🙂

It sounds interesting. Perhaps you could summarize your findings? I understand that nominal and ordinal measures are often misused in this way.

Thought experiment: Pick 2 of the following to be maximized and one to be set at the lowest tolerable level.

– Health (Including general physical fitness, mental wellbeing, etc.) (Lowest would be something you can’t fix with money.)

– Love (Family, friends, romance, community, “spirituality” etc.)

– Money (Lands, technology, culture, power, etc.)

Pretty cheesy but I think it holds… You see increasing happiness when the math checks, however if you raise any of those parameters too much at the expense of the others, you get neutral or even negative results. Not really paradoxical.

What’s the lowest standard for love and money?

You’re a penniless beggar outside a gated community where everyone hates you.

I think I would be quite happy with maximized health and love (not the “spirituality” part though, that is definitely… not my thing, assuming it is even a real thing in the first place) and minimized money. I would choose it over my current life definitely.

(This doesn’t really translate to real life well of course, real life poverty doesn’t just mean not being able to afford “luxuries”, it means a lot of unpleasant work to get you’re basic necessities, or just not having them- which here are covered by the health part.)

Yeah that characterization of money is really strange.

“Money (Lands, technology, culture, power, etc.)”

It seems to me the things people want most out of money — exempting “health” and “love” — are leisure & security, ends to which land, technology, power, etc., are merely means.

It interests me that people generally assume primitive humans must have been miserable. After all, they were exposed to the elements with no heating or plumbing or cozy beds, no TV or even books to read, constantly hunted and having to hunt for food, no medicine, etc. But from what I’ve heard, modern hunter-gatherer tribes have very high happiness rates. Of course any of us would see our happiness plummet if we were suddenly thrust into a hunter-gatherer life, so we assume that someone who was always a hunter-gatherer would also be unhappy. I think this just goes to show people aren’t too good at understanding different frames of mind.

On the other hand, the colonial authorities in the early European settlements in North America were apparently perennially baffled that people who had been abducted by the natives and lived with them for some time, often refused to come home when offered the chance of rescue, whereas people who had been born and raised in a native tribe, and then subsequently brought up in white society, usually went back to their hunter-gatherer lifestyle as soon as they were able to, so the ‘hunter-gatherers have happier lives than people in agricultural / industrial societies’ hypothesis may have something to do with it.

(Haven’t read the book but James Axtell seems to be the predominant writer on the subject.