. . .

Brought peace.

As you may have noticed, instead of another GIGANTIC WALL OF TEXT I am trying to write my rebuttal to Reactionary philosophy in the form of several smaller posts that I can then link together in a sequence index. This particular post addresses Reactionary claims that modern society causes international instability, leading to increased war (or increased “total war”) and the resulting mayhem.

This claim I received mostly from blog posts I can’t find right now and from discussions with Michael Anissimov. It goes that when states are fully sovereign, self-interested, and run by noble classes – as they were long ago – their wars are rare, as short as possible, and mostly fought in a civilized way.

But when states are subject to a larger international order (like the UN or “international law”), interested in ideological concerns, and governed by a host of factions competing for democratic power – as they are today – wars are more common, bungled into increased length and fatality, and turn into “total war” where anything goes and civilians are considered valid targets.

Michael specifically mentioned the Congress of Vienna as an example of the old order, pointing out that a bunch of aristocrats met up, divided Europe among them, and there was peace for decades afterwards. He compared this to the inelegance of modern “police actions” and “foreign interventions”, pointing out how World Wars I and II, at the beginning of the modern era, were unmatched in their deadliness and brutality.

Luckily, these questions about war and the stability of different models of international relations can be investigated empirically. Are wars worse today, or were we worse during the old aristocratic era? By what standards?

Let’s ask the media! War Is Going Out Of Style, says the New York Times. War And Violence On The Decline In Modern Times, trumpets NPR. Josh Goldstein says we are “winning the war on war”, Steven Pinker proclaims the victory of the better angels of our nature, and John Mueller even more triumphantly posits that War Has Almost Ceased To Exist

The statistics bear them out. The BBC notes:

The Human Security Report found a decline in every form of political violence except terrorism since 1992. “A lot of the data we have in this report is extraordinary,” its director, former UN official Andrew Mack, said.

It found the number of armed conflicts had fallen by more than 40% in the past 13 years, while the number of very deadly wars had fallen by 80%.

The study says many common beliefs about contemporary conflict are “myths” – such as that 90% of those killed in current wars are civilians, or that women are disproportionately victimised. The report credits intervention by the United Nations, plus the end of colonialism and the Cold War, as the main reasons for the decline in conflict.

The trend is older than just this decade. According to Goldstein:

In fact, the last decade has seen fewer war deaths than any decade in the past 100 years, based on data compiled by researchers Bethany Lacina and Nils Petter Gleditsch of the Peace Research Institute Oslo. Worldwide, deaths caused directly by war-related violence in the new century have averaged about 55,000 per year, just over half of what they were in the 1990s (100,000 a year), a third of what they were during the Cold War (180,000 a year from 1950 to 1989), and a hundredth of what they were in World War II. If you factor in the growing global population, which has nearly quadrupled in the last century, the decrease is even sharper. Far from being an age of killer anarchy, the 20 years since the Cold War ended have been an era of rapid progress toward peace.

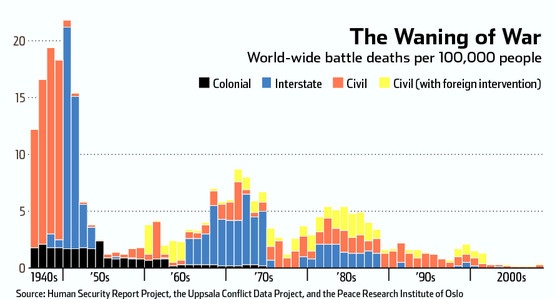

And Steven Pinker shows the following graph:

So there’s more than enough data to show the world has been getting more peaceful over the past seventy years. The most plausible Reactionary response would be that this is too small a time horizon: that the horrors of progressivism should be viewed over a timescale of centuries.

First of all, this shouldn’t be true. A staple of Reactionary thought is that the world has become notably more progressive since World War II, and a hyper-willingness to attribute anything that’s declined since that period to the progressive world-view. What’s good for the goose is good for the gander. Second, it is very suspicious to say that the part of the data you don’t have good statistics for, and only that part of the data, proves your point.

But in order to address this objection more fully, I tried to get fuzzy ballpark area data on the deadliness of wars in past centuries. My methodology was to comb Wikipedia’s list of wars by death toll, take all the ones with casualties of one million or greater, and organize them by era. The eras I used were 21st Century So Far, 1950-2000, 1900-1950, 1850-1900, 1800 -1850, 1700-1800, 1600-1700, 1500-1600, 1000-1500, 1-1000, and 500 BC – 1. Where casualties were given as a range, I took the center of that range, except in the Taiping Rebellion where I believe the top of Wikipedia’s range is crazy high and so I took nearer the bottom; where conflicts spanned more than one era, I placed them in the one containing the majority of the conflict.

I added up total war casualties for each era, then scaled them by population using 2005 as the standard – that is, deaths were multiplied so that the new number was the same percent of the 2005 population as the original was of its own era’s population. Then I divided by the length of the era to give average deaths per century during that era.

The 1900 – 1950 era indeed came on top, with 626 million projected deaths per century per 2005 population. Second place was 1600 – 1700, with 442 million. Other violent periods of note were 1850 – 1900 (326M), 1000 – 1500 (230M), and 1800-1850 (106M). There was no obvious trend related to time.

However one trend worthy of note is that the 21st Century So Far and the period 1950-2000 were by far the two most peaceful eras of any in the study (both at about 28M).

So the most progressive periods in history are also the most peaceful. And the Reactionaries’ pet period, the 1600s when the Stuarts ruled England and the Hapsburgs were still mighty, was the deadliest age of history outside a World War. I tested what would happen if I limited the domain to Europe, and the results are much the same (with the exception of 1850 – 1900 becoming much more peaceful).

This study is actually biased against me and in favor of the Reactionaries in two ways. First, I eliminated all wars with death counts less than a million, because otherwise it would have taken forever. But that disproportionately eliminates pre-modern wars, since they were fought among lower-population nations – a conflict today need only kill 1/7000th of the population to make my list, but one in 0 BC would have had to kill a full 1/100 or be dropped entirely.

Second, technology! Two days worth of airplanes dropping bombs on Dresden in the 1940s killed more people than several long and bloody medieval crusades. More modern death counts should probably be discounted to take into account the fact that we are just way better at killing each other when we want to, even though we want to much less often. Yes, the era of World Wars saw slightly greater deaths per population than the era of absolute monarchy in Europe. But the Allies were killing people with nuclear bombs, and the Hapsburgs were killing people with bayonets. The 17th century in particular, and the past in general, just really really sucked.

Some Reactionaries, intuiting this pattern, have tried to dismiss it by saying that, while progressive eras have few wars, their wars are much worse – the sort of “total war” that characterized World Wars I and II, and so rose to new levels of killing and barbarity.

But this article lists the worst conflicts of all time by percent of population killed. And you have to go to number six on the list just to get to World War II! World War I isn’t even on the list! The Mongols did not kill 11% of the population of Earth in twenty-one years by not being aware you could harm civilians; the various mercenaries of the Thirty Years’ War were no more innocent.

One last fact noticed in the process of going through Wikipedia’s wars list: in any particular era, it is always the least progressive countries that are having the wars. Even the miniscule death count in the late 20th and early 21st centuries is limited almost entirely to authoritarian African countries and Islamic theocracies. In neither World War was the major conflict two democracies (by any reasonable definition) fighting one another, and at least in the latter totalitarian side deserves a disproportionate amount of blame. The bloodiest conflicts of the past few thousand years, even adjusting for population, have been in China, which is basically Reactionary Utopia with an authoritarian Emperor, a Mandate of Heaven, and strict racial homogeneity. There is a lot of debate over whether two democracies have ever gone to war (answer: it depends how true of a Scotsman you are) but this very fact should cue you in that war and democracy are not positively correlated (and most likely not even neutrally correlated).

So to sum up: as the world has become more progressive over the past seventy years, conflicts and deaths from conflict have dropped precipitously. Virtually every past era was much more violent than our own, and the biases of this study probably mean they were more violent even than our numbers indicated. Every single one of the five deadliest conflicts in human history occurred before the Enlightenment, and in any given era the more progressive countries both start and participate in fewer wars than the less progressive countries.

Very likely this is due partly or mostly to economic factors – the point that no two countries with McDonalds’ ever go to war is a good one. But this does not negate the fact that our current political and social system is the one that economic factors decided to set up in order to achieve their economic goals.

I’m inclined to agree with your thesis, but there’s a subtle problem in comparing the pre- and post-WWII eras, that being the dog that didn’t bark. The dog, in this case, being global thermonuclear war.

What I mean is that a fair consideration of death-by-government in the late 20th ought to consider the nonzero likelihood of total or near-total extinction. If the chance was only 1%, that’s still another 30-60 million ‘ghost’ deaths that ought to go on progressivism’s tally. And complicating that calculation is the anthropic principle–if there had been such an exchange, we wouldn’t be having this discussion, so the true probability may have been much higher than it would seem to us now.

First, you’re blaming progressivism for the existence of nuclear weapons?

Second, if total extinction could have happened with moderate probability and didn’t actually happen, during the ascendancy of progressivism, then doesn’t that count as 30-60 million deaths *prevented* by progressivism?

Indeed. Adlai Stevenson’s “Don’t wait for the translation”? The Day After? Lyndon Johnson’s “Daisy” ad? The anti-Vietnam movement? The Detente? American right-wingers fairly hated all those pushes against the most frantic outbreaks of American war-mongering, from what I know. And any of that war-mongering could’ve very easily led to more escalation and carnage instead of “containment”.

(Oh, and Nixon going to China too; there was a political reason why it was such an unlikely feat – the paranoid red-baiting climate at home. And, on the other hand and in the meanwhile, Henry Kissinger stirring shit up in South America and covering up for the Khmer Rouge… dude, it’s almost as if Moldbug doesn’t know shit about the Cold War!)

(Well, I misspoke, of course Stevenson’s actions during the Cuban Missile Crisis were technically against the Soviet aggression – but what I mean is, he was a liberal and wanted peaceful coexistence, and opposed to politicians like him were hawks who wanted total victory.)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Adlai_Stevenson_II#UN_role

Remember that Reactionaries consider modern Republicans and Democrats to both be Progressives.

First, you’re blaming progressivism for the existence of nuclear weapons?

No; I’m not sure how you get that reading from what I wrote. I’m saying the existence of nuclear weapons is a fact of post-WWII history. I don’t think this is controversial.

if total extinction could have happened with moderate probability and didn’t actually happen, during the ascendancy of progressivism, then doesn’t that count as 30-60 million deaths *prevented* by progressivism?

No. If I play russian roulette and I get lucky, that doesn’t actually count as saving lives. MAD is fragilizing; fairly assessing the impact is a fundamentally different and much harder problem than assessing the impact of persistent diffuse conflict. In the latter case, it’s clearly fair to use the actual data as a reliable observable for riskiness. With MAD, though, you only have the one data point–did a nuclear exchange happen or not?–and there’s an extra problem of convexity: a 1% chance of killing 100% of the population is, on a straight utility calculation, vastly worse than a 100% chance of killing 1% of the population.

How do you avoid that fragility with reaction, though? The first guy to build nukes establishes global hegemony and avoids MAD by not having any threats left?

I’m not a reactionary, but I think most of them would argue that a patchwork of small heterogeneous sovereignities would be antifragilizing. The Thirty Years’ War probably is preferable to World War III, but…

Oh so in reactopia nobody even has the massive resources to pull off the Manhattan Project in the first place? Kings do seem to like to form empires, though…

I think part of it is the statistical effect of decentralization, which ought to be uncontroversial–nuclear war between Hong Kong and Singapore isn’t going to be an extinction event. The other part is just magical thinking that Well Run Self-Interested City-States wouldn’t do stupid self-annihilating things.

This is fair, and I think that it would be unfair to put the odds below 1% or above 20%, but that’s a very large range. OTOH, for the last quarter century global thermonuclear war has not been an issue in the same way and things seem to still be really really nonviolent.

“It goes that when states are fully sovereign, self-interested, and run by noble classes – as they were long ago – their wars are rare, as short as possible, and mostly fought in a civilized way.”

Well, that’s bobbins, for a start. The Hundred Years’ War? 1337-1453. Mercenaries wandering all around Europe and ravaging the local populations without let or hindrance. The Wars of the Habsburg Succession? Spanish branch, 1700-1714. Austrians, 1740-1748. And those are just off the top of my head.

“the Congress of Vienna”

Yes, that and carving up the Sick Man of Europe worked so well, as we saw in the First World War. I don’t know where Mr. Anissimov learned his history, but I remember our Intermediate Certificate History classes where the back-stabbing, secret alliances, make a deal with one ally and then make another deal with the enemy of that ally all conspired to entangle the European powers in a snare of their own devising, where everyone was so confident that nobody would dare go to war by making the first move that they double-, triple- and quadruple-crossed each other, and by the end when a romantic zealot idiot carried out that ludicrous assassination, the dominoes were lined up to inexorably fall.

That’s why nowadays we don’t go to war, we have the Eurovision instead.

Oops! Forgot to mention why the pope continues to have the Swiss Guard – the Sack of Rome in 1527, when the Holy Roman Emperor was unable to control his own army even though he was the victor, and they pillaged and plundered and slaughtered to their hearts’ content.

I mean, damn it, I’m inclined to be a reactionary myself, but this kind of wishful thinking about ‘civilised wars’ is just nonsense on stilts.

So, they point out, we just go back to the 19th century and not earlier.

There are a lot of yesterdays in history. Most of them are incompatible. To demand that a Reactionary defend them all is as silly as demanding that a Progressive defend all Utopian visions, which also have incompatibilities. (Indeed the Utopias often were written against each other, so they are even more incompatible.)

Trouble with the 19th century is it was the Age of Expansion, when continental Europe looked about and started vying with each other for lands, resources, and power. Hence the colonisation of Africa (Belgium had its own mini-empire, see the Congo and King Leopold re: the Casement Report by the Anglo-Irish Roger Casement in his capacity as British consul, this being before he was executed as a traitor). Germany building up its naval forces and more or less kicking off an arms race with Britain over jealousy and imperial ambition, all of which laid the groundwork for the First World War.

“Peace at home” perhaps, but it all led up to the carnage later.

That’s because outside of Europe, the same structures were not in place. That calls for expansion of them, not their denigration.

Structures in themselves are neither particularly good or bad, it’s the use you make of them. If your people are inclined to go “We are the destined masters of the world”, then you can have as many parliamentary representatives as you like, you will still be more inclined to start shooting at your neighbours.

I’m not denigrating European institutions, but I am saying that in themselves, they are no great guarantee of human virtue.

“That’s because outside of Europe, the same structures were not in place.”

That assumes that the European powers without an overseas room for conflict would have been peaceful, rather than getting nastier with each other. Given that they fought various wars with each other as it was…

That’s why nowadays we don’t go to war, we have the Eurovision instead.

To be fair, a war starting over the Romanians failing to win this year would have been totally justified in my opinion. 😀

Romania won a moral victory as encapsulating and embodying the pure, perfect, distilled essence of the Spirit of Eurovision. The Platonic Ideal, as it were 🙂

The Greeks are like ourselves: the country’s fecked on account of the economy, the Troika are screwing us, sod it, we may as well go on the lash 😉

I’m sure Germany was just happy to finally hear what all their money is going towards: subsidizing booze.

The BBC Eurovision broadcast featured an interview with the Greek entry – they claimed it represented how badly they wished the economy was so good alcohol was free.

So they subtitled it with “Alcohol is NOT free.”

I wish to God! Whatever about the Greeks, the German bail-out over here is subsidising the bank bond-holders (and just to make sure we don’t get notions, every now and again an EU official drops in to tell us to keep the austerity going).

God alone knows what the Budget in December will be like; more slash-and-burn, but from what? And now we’re being hauled over the coals about possible tax break deals for Apple.

For those of you unfortunate enough not to have the Eurovision broadcast by your national stations (I believe the Poles, as well as Turkey, didn’t show it for different reasons – Poland because it couldn’t afford it, the Turks because of the kissing Finnish girls) – here is the Romanian entry in all its magnificent glory of perfection of the acme of Eurovision 🙂

And the Greeks 🙂

Of course, in your Reactionary post, you observed that many pieces of progress can be attributed to technology alone. Yes, bombers can do more damage. But anti-aircraft guns and radar can do them serious damage. Improved communications can also avert war without any changes.

And above all else — MADD. The specter of nuclear annihilation probably did more to avert war than any change in human society.

Yes, but as above, it’s very fragile.

“And above all else — MADD. The specter of nuclear annihilation probably did more to avert war than any change in human society.”

Seconded from the Left. (Of course that specter, and the habits it produced, may have made some changes in society, which then … round and round.)

I’m hoping someone comes up with a cite to show that Reactionaries really believe governments more like their ideal are more peaceful.

Second thought: I hope to find out what Reactionaries really believe about governments, war, and peace.

I have yet to encounter a reactionary argument that didn’t seem absurd, and I’d like to know whether this is a particularly good time to practice not being biased in various ways, if I’m only seeing strawmen second hand, or if the whole idea is just actually absurd.

They also have different base level values than you, I think.

For a good summary, read “Liberty or Equality” (1952) by Erik von Keuhnelt-Leddhin.

Good points. I’ll just add that it is really hard to intuit which way technology should weight, since kill tachnology improves but so does medical technology. How many of those old deaths were infection, etc.?

Maybe it would be instructive to compare Greek city states? I don’t know if they differed enough or existed for long enough to be useful but it would control for tech level, population size, ethnicity, etc.

Until World War II most soldiers died of disease.

But many of them probably wouldn’t if there wasn’t a war.

True. So the earlier casualty lists are inflated to the current ones, since the big difference is pencillian.

The big difference is probably clean water.

Also possible. But also technological.

Better sanitation is modern, but reactionaries (at least, not this one) are not against modernity in its technological form. Don’t worry, we don’t want to force anyone to give up his iPad, or penicillin. Indeed, many of us, especially on the net, are big technologists. Do I prefer contact lenses, and air conditioning, and appendectomies, over glasses, being miserably hot, and dying of appendicitis? I do!

One other thing that is modern and which confounds just a bit the particular analysis you are attempting here is modern military tech. We kill less now than we did even 10 years ago, due to the advent of precision guided munitions. There will be no more Dresdens. And we also can save many more wounded than we did even in Vietnam, because of the tremendous advancement in both the understanding of trauma as well as how to deal with it.

As for your attempt at making up stats, I don’t find it that particularly compelling. Let me just sketch out an extremely simplified reactionary view of history to explain why.

We start with the era of unchallenged Catholicism in the West. Sorry, whatever wars happened in Roman times or before in the West, or wars which were non-Western, are not useful. It’s simply a category error to put Genghis Khan down as on my side or yours. So, back to Europe: a great civilization arose. There were indeed wars and they should count against Reaction. This is the period that you strangely lump into 500 years, 1000-1500, and then compare to 50 year periods. Dude: the 230M that you count in that 500 years averages 23M per 50 years. Note that this period, by your stats, is more peaceful than 1950-2000 or 2001- (both 28M according to you). In fact I kind of doubt that is true due to technology, but I am just pointing out here what your own stats imply.

Eventually the world is shaken by Gutenburg. The problem is this: the New Testament is basically a blueprint for egalitarian rebellion. The most obvious reading has Jesus as a rabble rousing rebel, telling everyone to fuck authority. When only priests can read and/or have a copy, the powerful can hide this Jesus and control the people. When everyone can read his own cheap Bible, everyone can determine for himself that the ultimate Author has determined that that all men are brothers, the poor are morally superior, that they should take up a sword, that possessions are suspect and the rich damned, that the last shall be first, etc. So, practically immediately the virus of radical egalitarianism is loosed upon on the world. And practically immediately there are really nasty wars erupting.

Now you have a period of five hundred years in which democracy gradually wins, but not without reversals and not without much blood. The old regime is gradually displaced everywhere, radically terminated in some places. The wars in this period must be looked to determine fault, but they are the ones that are most interesting (at least to reactionaries). Many of them are revolutionary wars of some kind, and these are almost all extremely bloody. Early in the period the egalitarian/democratic mind-virus is limited to Europe, but later on it spreads to the world via European missionaries. Most important for later history, the English dissenters are kicked out and given a rich country all their own, which (of course) rebels and then gradually becomes the center of world progress.

It is the last 200 years of the 500 where progress is powerful enough to really get big wars. This explains the ramping up you see in your war stats, for this period.

Finally, there is the culmination of the democratic era in Europe, with WWI and then WWII. The non-democracies are defeated both times in the bloodiest wars to date. Finally, Europe is purged of all elements of the old regime. Progress has won. Now there’s nothing left to fight about — and as we see, no fighting. Outside of Europe, it takes just a few decades for the USA or USSR to displace all remaining non-progressive opposition (aka “colonialism”), and nasty but small wars erupt in most of these places. There’s some odd proxy wars fought between the USA and USSR, both standard bearers for progress, but these wars end when the USSR collapses.

Finally there is just the USA astride the world. All remaining regimes must be left regimes; we tolerate nasty left regimes like Cuba, but not nasty right regimes like South Africa. However in both cases there is not much war.

With this view in mind, let us revisit the atrocity timeline you reference. Look at the list of Percentage of World Population Killed. We remove the first five entries as before Gutenberg and/or not Western. Then WWII. Then another non-Western, then the Taiping Rebellion which I am not sure about. (It is modern enough that it might have been sparked by egalitarian memes, but I really know next to nothing about it.) (OK, just did my wikipedia reading and the Taiping Rebellion is definitely progressive.) So we have 4 of 10 of the worst wars as progressive ones. The other 6 don’t count. Zero of 10 reactionary.

Or consider the adjacent top ten, Deaths Per Year. Here we have progress really showing its colors, since genocides are included. We have 7 of 10 progressive atrocities, and 3 of 10 don’t count. No reactionary wars.

We Wrestle Not With Flesh and Blood But Against Powers and Principles

Dude, that’s 230M per century.

You’re right. I misread Scott. I withdraw that particular criticism.

Those aren’t 230M deaths from 1000-1500, but 230M deaths per century. Just as all the other numbers. (Also they’re extrapolated deaths, but that’s not terribly important.)

You know, there’s a reason Scott used “percentage of population” as a measure. The human population in 1000AD was about 400 million. The human population now is about 7 billion. Can you hazard a guess as to why unscaled numbers of population might provide slanted results?

Leonard –

Are you describing World War Two as a “progressive war”? That would seem odd. Even if one accepts the argument that Churchill and Roosevelt proceeded from liberal motives and could have avoided war, Hitler would more than likely have invaded Russia and Japan would more than likely have sought expansion in Asia. Are Adolf Hitler and the Imperial Japanese to be classified under “progressives”?

Might want to get onto the Latin Americans about that, man. Pinochet? Montt? The Contras? America spent much of the twentieth century imposing right wing regimes on overly pinko peoples.

The best argument that reactionaries might have, I think, is a conservative one: that current threats to world peace are at least partly products of liberal universalism. I believe that the invasions of Iraq and Afghanistan had far more to do with resources and geopolitics than establishing liberalism but they could not have been promoted without sunny sentiments of democracy and secularism. Many of the threats to peace within nations, meanwhile, are the products of leaders opening borders with little thought to the question of how people from different cultures might get on with one another. Things are fairly peaceful now, then, but how long they’ll remain peaceful is worryingly arguable.

If the world were completely unprogressive, than the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan still could have happened, but the justifications would have been more like “they don’t have enough sense to rule themselves” or “they don’t know what to do with their oil”.

Are you kidding me? This IS the current justification, it’s just that the definition of “enough sense to rule themselves” is different under 21st century liberal capitalism than it used to be in, say, Kipling’s times. If Western propaganda started speaking exclusively about the concrete state of “human rights” in third-world countries (and I’m all for human rights), someone would’ve turned it around to at least make a plea to sanction Pakistan or Saudi Arabia. Even the dominant discourse of today’s propaganda is not nearly as focused on liberalism and universalism as reactionists like to pretend. And behind the propaganda, surprise surprise, only a few do-gooder NGOs really care about individual welfare and rights.

I was sufficiently unsure of my ground that I thought I’d see if it would pass as deadpan humor.

Multiheaded –

Even the dominant discourse of today’s propaganda is not nearly as focused on liberalism and universalism as reactionists like to pretend.

A fair point. But this does not mean that all the little Hitchenses who wax lyrical about freedom and democracy – among whom I could have been numbered in times gone by – do not believe in the virtues of “spreading” both, it just means they are inconsistent in their beliefs. And the most sincere beliefs can be the most incoherent.

I suspect that the propagandists themselves, like Bill Kristol or Robert Kagan, are an odd mix of cynical ambitions and liberal presumptions, in that they invade countries to assert American power; secure resources; protect Israel et cetera rather than to free their citizens but probably believe they can establish stable market systems that will make the aforementioned ambitions realisable. I doubt they give a solitary damn about Iraqis, then, but they probably weren’t hoping to establish a dysfunctional state that sells oil to Russia and gets friendly with Iran.

“When only priests can read and/or have a copy, the powerful can hide this Jesus and control the people.”

This again? My dear, if you’re going to promote a Reformation view of how the Wicked Romanists Perverted the Pure Gospel, please follow through – one of those who promoted, as you say, “everyone can read his own cheap Bible” was Martin Luther, who most certainly did not approve of the Peasants’ Rebellion in Germany after the foundations of religious social order were challenged.

Once the vacuum of the breakdown of unquestioned religious authority came about, the secular princes stepped in very quickly to claim it for themselves – the notion of the “Divine Right of Kings” came about because kings and princes claimed for themselves to be the ultimate authorities in worldly affairs as delegated by God, and had plenty of Bible verses to quote to back it up.

It’s not true to say that, thanks to Gutenberg, the mass dissemination of Scripture in the vernacular was solely responsible for the “the virus of radical egalitarianism”. There were plenty of movements long before that; see the long history of heresies such as the Bogomils (10th century), Cathars (11th century), Lollards (mid 14th century), and a whole raft of splinter movements, apocalyptic cults and the like. And post-Gutenberg, as I said, the secular states were only too happy to step in and make themselves the powers, leading quite soon to Cuius regio, eius religio where you could think whatever you liked about saying your prayers including denouncing the pope as a limb of Satan but you better make damned sure you were in agreement about who the prince was – see how Elizabeth’s spymaster Walsingham cleverly turned the trials of recusants and priests coming in from the Continent into treason trials and not heresy or religious ones; who is going to stand up for the rights of potential assassins and terrorists driven by blind zealotry who hate the (English) way of life and just want to do away with all that right-thinking patriots hold dear?

If you want to argue about the rise of unchecked egalitarian movements, go ahead, but please don’t re-purpose “Foxe’s Book of Martyrs” while doing so.

“The problem is this: the New Testament is basically a blueprint for egalitarian rebellion. The most obvious reading has Jesus as a rabble rousing rebel, telling everyone to fuck authority.”

I find this interpretation … dubious. Give unto Caesar what is Caesar’s and all that. Could you pull some quotes to back this up?

The stuff about giving up all your wealth to the poor, and that the way you treat Him is based on the way you treat the least among you?

I got three repeated messages when I read the Gospels: eternal life through Jesus; Jesus hates divorce; Jesus hates rich people.

Oh, sure, he was big on people giving up everything and becoming religious hobos or whatever, but he didn’t seem to have a problem with the civil authorities – indeed, there’s repeated emphasis on how he wasn’t the expected messianic leader who would overthrow the Roman occupation and reestablish Israel as a sovereign nation. Except maybe metaphorically.

One notes that only one person was told to give up everything — a special vocation, not a general call.

It’s helpful to notice whom the was saying what to.

So … you’re saying all wars (involving western societies) are between Reactionaries and Progressives, and any war involving Progressives is a “progressive atrocity”?

Interesting article.

Just as you have fairly criticised Reactionaries for treating you as a Generic Liberal Foil, you generalise quite a lot about Reactionaries. These are the beliefs that we all seem to hold in common. There isn’t necessarily a single Reactionary line on war, political engineering and many other important questions.

Regarding war, as with crime, if I had to come off the fence I’d say political approaches were better in the Victorian era, but not necessarily so further in the past. However, the real problem here is the huge number of variables; it is difficult to know whether two people are controlling for the same ones. Ideally, one controls for things one cannot hope to change, since in comparing the present to the past one usually makes hidden inferences about the utility of future decisions. However, there’s no guarantee that two Reactionaries and a progressive will agree with each other about what those independent variables are.

In the case of those Reactionaries who claim that the state of war is strictly and obviously worse today, and this is all due to progressivism or the Cathedral, I endorse your well-researched criticism. I think, however, that a more thorough critique would have to address arguments such as this, this>, this, and this.

I must also point out that this:

seems rather different to what Moldbug and many other Reactionaries think. He says,

Like Moldbug’s political absolutism, I’m skeptical about this confident claim. However, I’m not too impressed with what passes for international law, and in particular I think that USG is too dominant. It causes problems, not limited to war, which seem facially inexplicable. For example, if you read all of Angus Roxburgh’s political history of modern Russia, you may get a strong sense that Russia’s high level of corruption, political gangsterism and lack of economic freedom has been stimulated by USG’s bullying, tactless and irresponsible promotion of democracy on Russia’s doorstep. The American elite would respond with similar authoritarianism to genuine threats to their power, e.g. if the Tea Party en masse were to start assassinating high-level bureaucrats and forming militias. Consider the America elite’s totalitarian response to just one terrorist in Boston.

I think that Russia’s disastrous conflict with Chechnya would also have been conducted differently, were it that the threat of American intervention did not loom over all such conflicts. So the modern, international balance of power causes harm in ways not limited to full-blown and prolonged war. It is very difficult to compare it to arbitrary periods of history, but there is undoubtedly room for improvement of some kind, and this seems unlikely to be generated within conventional democratic politics.

Also, here is James Burnham, writing in 1943 about how overt violence can funge for even worse, subterranean conflict.

In the case of those Reactionaries who claim that the state of war is strictly and obviously worse today, and this is all due to progressivism or the Cathedral, I endorse your well-researched criticism. I think, however, that a more thorough critique would have to address arguments such as this, this, this, and this.

After I skimmed the links you posted, I see a clear reason why Scott’s impression that the Reactionaries liked his explanation of Reaction so much could be true: Everyone in the Reaction seems to be more interested in being a goddamn poet than being understood.

I’ve never felt such a strong urge to thumbs up a comment.

Yes, precisely.

I consider myself thumbs-upped. 🙂

“Everyone in the Reaction seems to be more interested in being a goddamn poet than being understood.”

A lot of people feel the same way about the rationalist crowd except instead of aping poets they ape philosophers. Lots of big fancy complicated words designed to impress people rather than actually aid in understanding.

I agree! So, to the gulag with all of you people!

Their habit of reinventing a new philosophical vocabulary certainty doesn’t help. It is not like the world needs another of those behemeoths.

“but one in 0 BC would have had to kill a full 1/100 or be dropped entirely.”

Agreed with this post, but this seems like an implausibly low population estimate. The entire Roman Empire, for which we at least have some records, peaked at about 100 million people during the first century AD.

You’re correct. I misread my population table – I wrote down 100 million as an average for the 500 BC to 1 AD period and then wrongly listed that as the population in 1 AD, but in fact 100 million was the population in 500 BC, and the population in 1 AD was 200 million according to Wikipedia.

(that still doesn’t mesh well with your Roman Empire estimate, but it seems more within the margin of error)

I think the strongest reason war is less deadly when it happens are the progressive urges civilized countries have. Sure our weapons are technologically more advanced, but the fact that we CARE about civilian casualties seems far far more important to me. I’ve in fact seen it argued by conservatives that the reason we get long drawn out wars like Vietnam and Iraq is our pussy-footing around, and it would be far more humane to engage in TOTAL war, because it would be over far sooner and more decisively. I think it can be convincingly argued that governments run by progressive sentiments end up less efficient and effective, but those sentiments are far better and more amenable to my values than many reactionary sentiments.

…and it would be far more humane to engage in TOTAL war, because it would be over far sooner and more decisively…

Perhaps. On the other hand, it would be more humane to engage in no war at all, as would have been eminently possible in Iraq and Vietnam. Some reactionaries seem to me to be far too gung ho about the righteousness of starting wars whenever it would be cathartic. John Derbyshire once said that after the bombing of Pan Am Flight 103, America “would have been entirely justified in sending an expeditionary force to invade Libya and reduce its towns, cities, military and commercial establishments, and communications facilites to heaps of trash”. The fact that it has never been proved that Libyans were even guilty does not seem to have occurred to him.

Also, that previous meddling by vested interests in the Middle and Near East set up situations where the chickens came home to roost. Sure, bomb your enemy-of-the-moment into dust – but what about all the hardliners who ran their countries under iron control backed up by American and British aid because it suited national interests of those countries, and made their citizens hate the West for very good reasons?

I won’t comment on Royal Dutch Shell and its activities in Nigeria, but the same company has a gas pipeline on the west coast of Ireland, which caused and continues to cause a lot of controversy, and there is a definite indication that the government of the day (and subsequent governments) were very inclined to support the multinational by using the national police force as pretty much security for Shell, never mind handing out compulsory purchase orders like confetti and the judiciary taking a very dim view of protests.

It seems to me that the reason why the period 1950-now has been remarkably peaceful by historical standards is essentially historical contingency. It’s the result of a lot of factors, remarkably few of which can be convincingly tied to enduring results of modernity, and it doesn’t seem to me to be at all safe to assume that it will continue.

We have, to start with, WWII. This was really remarkably bloody, and had (at least) two relevant effects: it shocked Europe and Japan, at least, into going just about entirely pacifist since (and these are both areas that have, historically, driven quite a lot of wars) and it set up the Cold War status quo, in which any war that was fought would eventually become an aspect of the US/Soviet confrontation, and hence invoke the specter of global thermonuclear war. The former effect is running out. Few people who remember WWII remain alive today, fewer and fewer as time goes on, and more aggressive powers like China and the Muslim world are starting to put pressure on Europe and Japan. Either these powers will throw aside their recent pacifism, and hence more or less inevitably go back to triggering wars on a semi-regular basis, or they’ll get run over, and replaced in the international calculus by more aggressive powers who will likewise trigger more wars. The latter effect has already run out, inasmuch as the Soviets are now gone; the US’ commanding military dominance has had something of the same effect, but that can’t last forever (in my cynical moments, I’m reasonably sure it can’t last much longer than now). And when the US stops being overwhelmingly militarily dominant, it can’t shield Europe or Japan nearly as effectively, pushing their return to belligerant status harder.

I don’t see anything about modernity, either the technology or the politics, which seems likely to me to actually reduce war in the long run. The UN is a joke; the only nations who would pay attention to it rather than nationalistic ambitions are the ones we don’t need to worry about anyway. Economic interlinking is more significant, but still won’t overpower nationalism, when that force stops having been neutered by WWII. Of course, the technology with which we fight wars has changed and will remain changed. But the effect this has on casualties can’t really be rigorously predicted; it may be true that there will never again be a Dresden, but it’s certainly true that there is now the potential for Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Saying that in modern times there will never be war on the same scale again seems shockingly, even irresponsibly optimistic to me.

Steven Pinker lays out the case for a long-term trend in falling wartime deaths, and the reasons for believing ‘modernity’ (democracy, human rights, media) to be responsible, much better than Scott does. Of course, he has a 700 page book to do it in and more solid references. Well, about 200 pages for chapters 5 and 6 of _Better Angels_.

The argument from historical contingency proves too much. Maybe the british were remarkably powerful and successful only because they lucked into the steam engine and had nothing to do with their culture? Or maybe they only GOT the steam engine because of the culture? How do we distinguish these? Statistics for the last 70 or so years are the only things we have to go on for a “progressive-dominated” world, and I don’t think just throwing them out because it’s historical contingency is better than paying attention to them.

My main objection to this is intuitive – it seems really really hard to imagine, say, France and Italy going to war right now (I agree it is much easier to imagine, say, Iran and US). Insofar as there seems to be something called “liberal modernity” which France and Italy have and Iran doesn’t, it seems plausible that this is really good at preventing wars long-term.

(I think this might be the same as Friedman’s McDonalds point)

But Italy doesn’t really have anything France wants, in order for them to go to war over it. An unstable government and a dodgy economy? Got that at home 🙂

Now, unless a new Napoleon arises in France to start making his family kings of Europe, I agree we’re very unlikely to see Franco-Italian wars again – or unless we get a recrudescence of the Guelphs and the Ghibellines, where some Italian city-states allied with the French king against the Pope and/or the Holy Roman Emperor.

The fact that Italy has not had civil war is just as much a part of the claim about violence as the fact that it has not warred with France. But whatever level of internal conflict there is in Italy, factions will have foreign support.

In particular, the Years of Lead seems to have had foreign involvement. At the time, at least some people expected more violence. Propaganda Due, which may have had CIA and Vatican support, had plans for Italy very similar to the CIA’s contemporary work in Chile.

“We have, to start with, WWII. This was really remarkably bloody, and had (at least) two relevant effects: it shocked Europe and Japan, at least, into going just about entirely pacifist since (and these are both areas that have, historically, driven quite a lot of wars) and it set up the Cold War status quo, in which any war that was fought would eventually become an aspect of the US/Soviet confrontation, and hence invoke the specter of global thermonuclear war.”

In the past, very bloody wars have not had this effect: for example, World War 2 followed twenty years after World War 1, which was probably unparalleled in terms of traumaticness.

The Cold War seemed pretty good at producing limited, non-thermonuclear wars…Vietnam is the paradigmatic example, but there are others. Besides, wars have been declining even faster since the Cold War ended.

I think you are mistaken to say that the 17th century is the pet period of the reactionaries (eg, see Leonard’s comment). The reason that they talk about that period is that it is the beginning of modernity. They talk about the Stuarts because they were deposed. The English Civil War was quite modern and was entirely the fault of the radical Protestants. It wasn’t nearly so bloody as the 30 Years War or the French Wars of Religion, both of which have more blame to go around. But the Reactionaries are certainly aware of these wars and see them as central features of the beginning of modernity.

As to question of whether large death tolls occur in progressive places or not, you are certainly right to point to imperial China. But I want to address the recent “authoritarian African countries and Islamic theocracies” that you label the opposite of progressive. Of course reactionaries will call them modern. But in any event, what is important is their governments lack legitimacy and thus stability. Monarchies may or may not be autocratic, but their central feature is predictable succession.

Saudi Arabia is an absolute hereditary monarchy with, as far as I can tell, a very stable political environment. It’s also a very awful place to be if you aren’t a (male) citizen or a Western tourist/expat.

Or look at the Japanese Shogunate; lots of “social stability” and authoritarian control for 300 years, then it simply collapsed in the face of global technological and economic change, and led to the rise of an extremely aggressive, ruthless militarist and imperialist ideology among the heirs of the dispossessed ruling caste.

(yes, yes, I realize that we’re talking about slightly different things here; chance of violent death vs. persistent conditions of socioeconomic deprivation and general repression)

I actually disagree with this. Monarchies have predictable succession in theory but rarely in practice over long time scales, and a *huge* number of wars are in fact fought between rival claimants to the throne. Whether it’s “younger son is smarter than older son”, “older son might not be legitimate”, “legitimate heir is three years old and someone else wants to be regent”, “there’s no legitimate heir and a couple distant family members all have claims”, or “well, it’s time for a new dynasty anyway”.

Democracies seem to do much better in that if anyone ever gets super-confused over who the government should be they can just have another election.

Democracies have legitimacy problems too, in that you have to trust that the election was carried out fairly. These days we have paternity tests that are so cheap and easy they churn out TV on an industrial scale about them.

If you want to talk about democracy vs monarchy, then talk about it. But you brought up “authoritarian African countries and Islamic theocracies” and seem to be grouping them with monarchies. I’m just objecting to grouping the with monarchies.

Democracies seem to do much better in that if anyone ever gets super-confused over who the government should be they can just have another election.

No, it is just the very definition of democracy is a country that successfully transfers power via elections. There are innumerable cases of democratic elections collapsing due to fraud, the strongman simply ignoring the elections, or a faction that objects to the outcome and starts a civil war. But then the country gets reclassified as “not a democracy.”

It’s not a virtue in a form of government that attempts at it often fail.

Not sure to what extent your title should be interpreted as making claims as opposed to jokes, but “education” and “public order” are serious points of contention with the reactionaries.

In what way? Do they say these are not goods, not provided by modernity (exclusively, originally, or at all)?

Wait, if you want to live in the past, why stop at the 1600s? Every thing I come across about tribals says they are all really happy, and some even want to go back after living in modern society for a while.

In fact, if you think about it, our happiness meters must be kinda optimised for tribal lifestyles (at least socially; abundance does increase happiness).

For one thing, I think that tribals are much further outside the Structured Industrial Society Box than, well, structured sorta-industrial societies.

Also, reactionaries don’t reject tech. A significant number are transhumanists.

Yeah it will be far harder to do, but isn’t it better in terms of ideals? If I wanted to be a reactionary I’d totally say we needed to decentralise social structures as far as possible.

It doesn’t sound all that far-fetched to convert the world into a set of tech-friendly Auroville-like places (it’s not the same but its close).

Do you have a spreadsheet or other form of partial results from your calculations that you can share?

2000-2013: 3.7

Pop: 6.5

Rat: 1

WDY2005: 3.7

Adjusted: 28.4

3,700,000 – Second Congo War (1998–2003)

1950 – 2000: 9

Pop: 4

Rat: 1.6

WDY2005: 14.4

Adjusted: 28.8

1,700,000 – Afghan Civil War (Afghanistan, 1979–)

1,200,000 – Korean War (1950–1953)

2,000,000 – Nigerian Civil War (1967-1970)

1,000,000 – Iran–Iraq War (1980–1988)[31]

1,000,000 – Second Sudanese Civil War (1983–2005)

1,600,000 – Bangladesh Liberation War (1971)

1,000,000 – First Indochina War (1946-1954)

1900 – 1950: 101

Pop: 2

Rat: 3.2

WDY2005: 323

Adjusted: 646

69,000,000 – World War II (1939–1945), (see World War II casualties)[2][3]

7,000,000 – Russian Civil War and Foreign Intervention (1917–1922)[14]

20,000,000 – World War I (1914–1918) (see World War I casualties)[10]

3,700,000 – Chinese Civil War (1927–1949)

1,500,000 – Mexican Revolution (1910–1920)[30]

1,000,000 – Sino–Tibetan War (1930-1932)

1850 – 1900: 38

Pop: 1.5

Rat: 4.3

WDY2005: 163.4

Adjusted: 326

1,000,000 – War in Venezuela (1830-1903)

20,000,000 – Taiping Rebellion (China, 1850–1864)[9]

10,000,000 – Dungan revolt (China, 1862 –1877)

5,000,000 – Conquests of Menelik II of Ethiopia (1882–1898)[15][16]

1,000,000 – Panthay Rebellion (1856–1873)

1,000,000 – Nien Rebellion (1853–1868)

1800 – 1850: 9

Pop: 1

Rat: 6.5

WDY2005: 58.5

Adjusted: 106

4,500,000 – Napoleonic Wars (1803–1815)

2,000,000 – Shaka’s conquests (1816–1828)[23]

2,500,000 – Russian–Circassian War (1763–1864)

1700 – 1800: 19

Pop: 0.75

Rat: 8.6

WDY2005: 163.5

Adjusted: 163

16,000,000 – White Lotus Rebellion (China, 1794-1804)

2,000,000 – French Revolutionary Wars (1792-1802)

1,200,000 – Seven Years’ War (1756–1763)[33][34]

1600 – 1700: 41

Pop: 0.6

Rat: 10.8

WDY2005: 442.8

Adjusted: 442

5,000,000 – Conquests of Aurangzeb (1681-1707)

3,000,000 – Second Northern War (1655-1660)

1,100,000 – Eighty Years’ War (1568–1648)

25,000,000 – Qing dynasty conquest of Ming dynasty (1616–1662)[8]

7,000,000 – Thirty Years’ War (1618–1648)[17]

1500 – 1600: 4

Pop: 0.5

Rat: 13

WDY2005: 52

Adjusted: 52

1,000,000 – Japanese invasions of Korea (1592–1598)[32]

3,000,000 – Huguenot Wars[ (1562 – 1598)

1000 – 1500: 72

Pop: 0.4

Rat: 16

WDY2005: 1152

Adjusted: 230

45,000,000 – Mongol conquests (1206-1324)

13,000,000 – Conquests of Tamerlane (1370–1405)

3,000,000 – Hundred Years’ War (1337-1453)

2,000,000 – Fang La Rebellion (1120-1122)

2,000,000 – Crusades (1096-1272)

7,000,000 – Reconquista (790-1300)

0 – 1000: 17

Pop: 0.3

Rat: 21

WDY2005: 357

Adjusted: 35.7

5,000,000 – Yellow Turban Rebellion (184–205)

3,000,000 – Hunnic Invasion (408–469)

5,000,000 – Gothic War (535–554) (535-554)

4,000,000 – Three Kingdoms War in Ancient China (189-280)

500 BC – 0: 11

Pop: 0.2

Rat: 32

WDY2005: 352

Adjusted: 70

10,000,000 – Era of Warring States (China, 475 BCE–221 BCE)

1,000,000 – Gallic Wars (58 BCE–52 BCE)

Thanks!

Gregory Clark had a chart in his book Farewell to Alms showing that deaths due to violent death (including foreign war, internal conflict, and homicide) declined in Europe from the 11th century to the 20th century, went up during the two world wars, and then is back down since. I’m not sure how he calculated the statistics for medieval society, but the stats seem believable from the anecdotal histories I’ve read.

a) Societies with a state tend to have lower death rates due to violence than pre-state societies. England with a strong Stuart king or a strong national parliament will have a lot less violent death than the 14th century feudal England where jungle law applied between every lord and noble. I think most reactionaries agree with this point. I think the rise of the state accounts for most of the decrease in violence through the 19th century.

b) Unipolar systems are generally much more peaceful than multi-polar systems (at least until the unipolar empire collapses). Multi-polar systems tend to be quite violent. Here is where I disagree with at least some other reactionaries. I think Moldbug’s patchwork is a recipe for war. Now there is a case to be made that patchwork is better overall for other reasons. Multi-polar systems can be more dynamic due to military competition, and multi-polar systems eliminate single points of failure ( compare 16th century Europe to China at the same time). But I think anyone who thinks that a multi-polar system would be less violent is crazy. Bi-polar systems seem to have periods of peace punctuated by very violent war. I think we just lucky with the spin of the roulette gun that full fledged war never erupted between the U.S. and Soviet Union.

c) Improved overall mortality rates and lower birth rates both dramatically decrease fervor for war. High birth rates mean you have lots of surplus males pushed off the family farm and looking for adventure and riches. Low birth rates means each child is precious and parents do not want to send their only son to war. And since you are not pushing resource limits, there is less of a reason to go to war.

I think the decrease in war deaths in the past sixty years was due almost entirely to the transition to a multipolar to bipolar to unipolar system, combined with dramatically falling birth rates in the most powerful nations.

There are three additional points where I sympathize with the reactionary case, though I’m not sure I completely agree:

a) There was a huge increase in war death due to the two world wars. Reactionaries blame the extent of the violence in the two world wars on the liberal/left-wing powers (Britain, the U.S. and France). (Read here for the case against Britain in World War I http://mises.org/books/diplomats.pdf ). In this view, World War II was then caused by the left insisting that Germany attempt democracy after World War I, and insisting in destroying all the monarchical regimes that had kept reasonable sanity in politics. The result was real, insane, 200 proof democracy – not the tamed down, moderated by “responsible journalists” and unelected bureaucrats democracy that we have today.

b) There was also a huge increase in war death due to de-colonization, which was a leftist project. The left thought the colonies were ready to government themselves democratically, right now. The colonial powers pulled out, and almost immediately the democratic elections collapsed and dozens of countries ended up in civil war.

c) A number of remaining violent conflicts persist due to an unwillingness to resort to reactionary solutions. For instance, the thing to do in Israel is to have Israel annex Palestine, give the Palestinians various rights to travel and due business so the economies can normalize, but to not extend democracy to Palestine. But that part about not extending democracy is heresy, and so the solution cannot be done. A two-state solution is not viable because the land is so intertwined and Israel’s security position is precarious. And a single democratic state will not work because Israeli Jews would then be a minority vote and subject to democratic revenge at the polls. So the situation remains in limbo, since the one viable solution requires committing heresy against democratic progressivism.

“For instance, the thing to do in Israel is to have Israel annex Palestine, give the Palestinians various rights to travel and due business so the economies can normalize, but to not extend democracy to Palestine. But that part about not extending democracy is heresy, and so the solution cannot be done. A two-state solution is not viable because the land is so intertwined and Israel’s security position is precarious. And a single democratic state will not work because Israeli Jews would then be a minority vote and subject to democratic revenge at the polls. So the situation remains in limbo, since the one viable solution requires committing heresy against democratic progressivism.

Ugh, no. Just no.

I agree that a democratic revenge at the polls might end up being really really bad, but suspect that the alternative suggested would be much worse.

The correct response to such a poor model of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict is not to pick a horn and fall on it, it’s to say Mu to the scenario as presented.

Objectively the average ocidental people live pretty well, but for some reason, not so well as we could. Conclusion: so we need to go back to Monarchy based in a contrafactual argument. I don’t deny, but weapons of mass destruction weight against unsecure progress– toward risk tecnologies–, not progressive policies in general.

One thing that changed sometime in the past couple of hundred years, but has been especially true since World War I: in general, winning a foreign war no longer makes you wealthier. In the old days, you got your army together, went and attacked Those Guys Over There, and if you won, their wealth (in the form of land, gold, and possibly slaves) was now yours. Julius Caesar, Genghis Khan, Alexander the Great, Attila the Hun, and many other famous historical figures all won vast wealth by going to war. In the 20th century, though, wars between nations generally ended up costing far more than you’d ever make back by exploiting someone you conquered. So one much-overlooked reason that there’s less war today than there used to be is that there’s no longer any money in it!

(Note that this analysis doesn’t apply to civil wars: taking over the government of your own nation, even if that nation is fairly poor, can still make you and your supporters very rich. Also, you can still get rich off of other people’s wars – there’s plenty of profit to be had from a war you’re not fighting in.)

“Note that this analysis doesn’t apply to civil wars: taking over the government of your own nation, even if that nation is fairly poor, can still make you and your supporters very rich. Also, you can still get rich off of other people’s wars – there’s plenty of profit to be had from a war you’re not fighting in.)”

Though I suspect civil wars have their own hidden cost – a very long period of instability. If you control the government, you might not be controlling the government next Tuesday. because after winning a civil war,there’s typically lots of guns in the marketplace, maybe lots of factions who just saw how easy it is to overthrow a government, and a reduced social cost of violence.

And outsiders are leery on investing in a place that’s had three different governments in the last year.

Though your second point is well-reasoned. There is a TON of money to be made selling supplies and hospitality to people fighting in the war next door, as long as it doesn’t spill over. Thailand during Vietnam is a very good example of this – American GIs spent a ton of foreign exchange in bars and brothels , and helped kick-start the local economies.