Introduction

Assortative mating is when similar people marry and have children. Some people worry about assortative mating in Silicon Valley: highly analytical tech workers marry other highly analytical tech workers. If highly analytical tech workers have more autism risk genes than the general population, assortative mating could put their children at very high risk of autism. How concerned should this make us?

Methods / Sample Characteristics

I used the 2020 Slate Star Codex survey to investigate this question. It had 8,043 respondents selected for being interested in a highly analytical blog about topics like science and economics. The blog is associated with – and draws many of its readers from – the rationalist and effective altruist movements, both highly analytical. More than half of respondents worked in programming, engineering, math, or physics. 79% described themselves as atheist or agnostic. 65% described themselves as more interested in STEM than the humanities; only 15% said the opposite.

According to Kogan et al (2018), about 2.5% of US children are currently diagnosed with autism spectrum disorders. The difference between “autism” and “autism spectrum disorder” is complicated, shifts frequently, and is not very well-known to the public; this piece will treat them interchangeably from here on. There are no surveys of what percent of adults are diagnosed with autism; it is probably lower since most diagnoses happen during childhood and the condition was less appreciated in past decades. These numbers may be affected by parents’ education level and social class; one study shows that children in wealthy neighborhoods were up to twice as likely to get diagnosed as poorer children.

Given that respondents are likely wealthier than average, we might expect a rate of 2.5% – 5%. Instead the rate is noticeably higher than that, consistent with the hypothesis that this sample will be more autistic than average. About 4% of the SSC survey sample had a formal diagnosis of autism, but this rose to 6% when the sample was limited to people below 30, and to 8% below 20. This sample is plausibly about 2-3x more autistic than the US population. Childhood social class was not found to have a significant effect on autism status in this sample.

Results

I tried to get information on how many children respondents have, but I forgot to ask important questions about age until a quarter of the way through the survey. I want to make sure I’m only catching children old enough that their autism would have been diagnosed, so the information below (except when otherwise noted) comes from the three-quarters of the sample where I have good age information. I also checked it against the whole sample and it didn’t make a difference.

Of this limited sample, 1,204 individual parents had a total of 2,459 children. 1,892 of those children were older than 3, and 1,604 were older than 5. I chose to analyze children older than 3, since autism generally becomes detectable around 2.

71 children in the 1,892 child sample had formal diagnoses of autism, for a total prevalence of 3.7%. When parents were asked to include children who were not formally diagnosed but who they thought had the condition, this increased to 99 children, or a 5.2% prevalence. Both numbers are much lower than the 8% prevalence in young people in the sample.

What about marriages where both partners were highly analytical? My proxy for this was the following survey question:

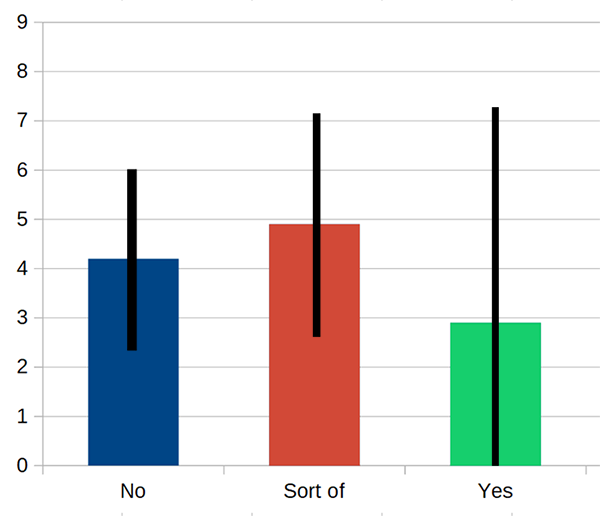

I’ll be referring to these answers as “yes”, “sort of”, and “no” from here on, and moving back to the full sample. 938 parents answered this question; 51 (5.4%) yes, 233 (24.8%) sort of, and 653 (69.4%) no. Keep in mind the effective sample is even smaller, since both partners in two-partners-read-SSC-families may have filled out the survey individually about the same set of children (though this should not have affected the “sort of” group). Here is the autism rate for each group, with 95% confidence interval in black:

There is little difference. If we combine the latter two groups, the confidence interval narrows slightly, to 2.7 – 6.5.

I asked respondents about the severity of their children’s autism.

People who hadn’t previously reported any children with autism gave answers other than N/A for this one, which was confusing. Instead of the 71 children we had before, now it’s up to 144 children. I’m not sure what’s going on here. Of these phantom children, 101 had mild cases, 31 moderate, and only 12 severe. Severe autism was only present in 0.6% of the children in the sample. There was no tendency for couples where both partners were highly analytical to have children with more severe autism.

Discussion

Autism rates in this survey were generally low. Although the general rate of 3.7% was higher than the commonly-estimated US base rate of 2.5%, this is consistent with the slight elevation of autism observed in higher social classes.

There was no sign of elevated risk when both partners were highly analytical. The sample size was too small to say for certain that no such elevation exists, but it can say with 95% confidence that the elevated risk is less than three percentage points.

This suggests that the answer to the original question – does assortative mating between highly analytical people significantly increase chance of autism in offspring – is at least a qualified “no”.

Why should this be? It could just be that regression to the mean is more important in this case than any negative effects from combining recessive genes or mixing too many risk genes together. Or maybe we should challenge the assumption that being a highly analytical programmer is necessarily on a continuum with autism. It seems like p(highly analytical|on autism spectrum) is pretty high, but p(on autism spectrum|is highly analytical) might be much lower.

Obvious limitations of this survey include the small sample size of both-partners-highly-analytical couples, the weak operationalization of highly analytical as “member of the SSC, rationalist, and effective altruist communities”, and the inability to separate non-autistic children from children who are not yet diagnosed. Due to these limitations, this should only be viewed as providing evidence against the strongest versions of the assortative mating hypothesis, where it might increase risk by double, triple, or more. Smaller elevations of risk remain plausible and would require larger studies to assess.

I welcome people trying to replicate or expand on these results. All of the data used in this post are freely available and can be downloaded here.

Thank you for dispelling a mild but deep worry I have had for a long time.

At the risk of exacerbating your worries — beware the man of one study. Someone (preferably, multiple someones) would need to replicate Scott’s results before we can treat them as reliable. Still, it’s a somewhat encouraging result.

Remember that this is a very low (and self-selecting) sample size too. Look at the error bars on that chart.

If I had to guess I would assume parents of severely autistic children had less free time to spend taking internet surveys for a start.

Nah. We have day jobs too, and time to slack off at the office.

In relation to the social status of autism, I’d be interested to know if there was a similar smaller proportion of children of members with ADHD as there is a higher proportion with autism than average (although did you discount non-US responses before comparing to the US average?). That’s just because being in the friends (and is) having children phase of life I get to observe some interesting features in the way these conditions are diagnosed. To strawman it, if you’ve got stable middle-class parents then you’ll have autism; the further you get from that ideal the more likely the label of choice is ADHD.

This might be UK (or even my social circle)-specific, but I am guessing from observation that it relates to a child’s learned ways of dealing with the frustration that they are sometimes feeling. It may also relate to the fact that those diagnosing have a norm of middle-class expectations, and therefore behaviours further from these are seen as more violent and disruptive, more characteristic of ADHD (note this is not a condemnation – I’ll defend my middle-class right to make judgements about other’s behaviours quite happily).

Be that as it may, there’s two points I’m edging towards here:

1. Is there value next year in surveying ADHD to see if there is an association (I know some children get both diagnoses but that seems to be rare)? Or some other common condition (dyslexia?) to get a wider picture – the autism figures in isolation might move towards answering a question, but imply autism can understood in isolation.

2. If there is an increased chance of autism in Silicon Valley, at least there might be some related lower risk of ADHD of this roo is social-class specific.

PS Thanks for doing this. We possibly take all your work for granted and you deserve more thanks.

A related phenomenon, the rates of ADHD diagnosis in the US are higher than in europe, which diagnosis more of other disorders, because ADHD treatment was approved by insurance companies the earliest, so there’s been a strong incentive to diagnose ambiguous cases as ADHD. (e.g. diagnostic criteria for ADHD and dyspraxia often overlap, but if its easier to get treatment for ADHD that would be labelled as ADHD)

I have to question the assumption that the actual rates of ADHD are the same in the US and Europe. ADHD seems exactly like the sort of thing that’s going to be highly correlated with people deciding that they’re tired of living in cramped, boring Europe and want to go to America instead. (This also applies to a bunch of other mental conditions, but ADHD seems the strongest.)

Lots of places in Europe are not cramped and plenty of places in the US are. The latter actually draw the most immigrants.

I was speaking much more of the period 100 years ago or more when the US and Europe were a lot more different than they are today, and when the bulk of the ancestors of today’s white population left Europe and came here.

bean,

Most white immigrants to the US didn’t come from the undoubtedly crowded towns and cities of Europe, but from the declining rural communities which also fed migration to those same towns and cities. Migration was a choice between crowded places to which to migrate (note people were not generally volunteering to go to uncrowded Australia).

Would those people than go on an even more cramped ship for three months?

I think people are fastening onto the word “cramped” in a way I didn’t really intend. This theory isn’t so much about physical population density as it is about the social structures and opportunities. Going to America was usually voluntary, but also a major risk. The sort of people for whom that seems like a good idea are likely to have rather different mindsets from those who choose to stay closer to home, in a way that probably correlates with ADHD. And given what we know about heritability, this suggests we’d see it overrepresented in America today.

US levels being roughly 4 times as high as UK levels seems like a lot to account for by that sort of mechanism.

Using bean’s theory, then people in Canada and Australia and New Zealand should be included with people from the US. Do these countries also have higher ADHD?

There is a positive association between autism and ADHD, so thet autists are more likely than others to be diagnosed with ADHD, and vice versa. It’s not uncommon to have these two diagnoses on top of each other.

Thanks. I would expect that as I am in effect suggesting that the two things are often interpretations of the same aet of observed symptoms. I would suggest the interest is in the single diagnosis cases though: is there any patterns that can be seen as to why a particular diagnosis might be reached, and not both?

What percentage of parents who responded had autism? I would guess it was lower than the general pool, since my prior is autistic people are less likely to have children at all.

Another consideration would be that we don’t necessarily want to avoid mild-moderate autism as a trait. I am sorry I didn’t get to respond to your survey on time – by the time I saw it you had already closed it. Both my partner and I read slate star and have an autistic son. But I wouldn’t want him to be neurotypical. He’s one of us, as it were.

~1%, so about a quarter that of the general pool. But the age controls make it tricky, since age alone anticorrelates the two.

What is the autism prevalence among children of SSC’ers who said they themselves are autistic?

I would expect that most SSC cases are mildly to moderately affected, and that the mildly affected are over-represented, while the severely affected are under-represented.

There’s also probably a difference between “highly analytical” and “at least mildly autistic” – my wife fits the first, but not really the second. I’m not sure what’s a good way to separate those out. Incidentally, both my daughters are mildly autistic, the older one more so than the younger.

So I didn’t filter by age, so my numbers are a little different than Scott’s. I filtered based on the “Children”, “Autism,” and “ChildrenAutism” columns. I counted 187 people who both had at least one child and either “have a formal diagnosis of autism” or “I think I might have this condition, although I have never been formally diagnosed.” Of those, 32 have at least one child with autism (17.2%). I counted 1703 respondents with at least 1 child. Of those, 93 had been diagnosed with autism (5.5%). So it looks like having a parent who either has autism or thinks they have autism is pretty strongly associated with increased likelihood of autism in offspring.

I am not sure exactly why all of my numbers don’t match Scott’s, if anyone sees an error with how I did this let me know. I just filtered everything in Excel cuz I’m lazy.

I’m not sure which of your numbers you say don’t match mine, but one reason might be because I was going by child – ie if a parent has two children, one of whom has autism, that counts as 50%. It sounds like you are going per parent with at least one autistic child, which might be part of the difference.

That’s probably it. Just wanted to be sure I wasn’t looking at the wrong columns.

What is the actual research question Scott is attempting to answer? We already know that autism is highly heritable, so assortative mating between autistic people would absolutely put children at some increased risk of being autistic.

It seems to me like what Scott really wants to test is the amount of overlap between “autism genes” and “analytical genes”. Insofar as there is even a slight amount of overlap between autism and analytical-ness (seems likely), there will be a non-zero increase in the risk of autism among children with analytical parents. That said, the current study is woefully underpowered to test this hypothesis even with the inclusion of the inattentive respondents (i.e., people who said they didn’t have a kid with autism then later said they did). I might have missed it, but Scott also didn’t actually measure “analytic-ness”. He just assumes we’re all analytical. Right? Surely his assumption is valid, but this needs to be confirmed. Even a single face-valid item would have shined some light on this assumption.

It would have been very interesting if Scott found a positive result because that would mean the effect size was large, but I completely disagree when he says that his negative result suggests a “qualified no” to his question. I think the only reasonable take-away from this is that the effect size is somewhere between trivially small and moderate, which is what everyone probably expected. In other words, this probably shouldn’t shift our priors much at all.

My understanding is his baseline assumption/hypothesis is ‘all autism genes are analytical genes’. Call them ‘nerd genes’. If you have some of them, you end up analytical. If you have a lot of them, you end up autistic. So, two people who are nerdy would have a higher chance of having a kid with enough of these genes to put you in autistic territory which is undesirable.

I would guess that Scott is open to the possibility that the overlap could be anywhere between “small-but-non-trivial” and “quite a lot”. I doubt he believes that analytic genes and autism genes are exactly the same.

I agree with your guess about his overall hunch, but that’s not what he tested in his post.

His research question is stated clearly in the third paragraph of the “Discussion” section: “Does assortative mating between highly analytical people significantly increase chance of autism in offspring?”

The measure of “analytic-ness” is the question about whether your partner reads SSC or participates in the EA or rationalist community.

Are we confident that

is a good proxy for “analytic-ness”? I’m also not entirely convinced that “analytic traits” necessarily map directly to “autistic traits”.

I wish Scott had included a self-identified degree of analytical-ness in the survey, even as I concede that SSC readers are almost certainly predominantly analytical.

I think it would have also improved his analysis. Sure, our average level of analytic-ness might be higher than the general population, but there will still be variation among SSC readers. He could have included that as a covariate in his model to test for the interaction we’re all assuming is there. In other words, he could have tested whether the incidence of autistic children among SSC users is higher among readers who were highest in analytic-ness. In fact, he could have asked the exact same question about the partner too and shown that the highest incidence of autistism is among the kids of SSC readers who were themselves highly analytical and married to highly analytical people.

I’m not sure asking an analytically-inclined population to analyse their own analytical-ness is going to get a stable measure. After all, is there a reasonable upper bound to analytical-ness? Would we all put it an the same place or not? I cant see a way you can create a stable scale by asking for this form of self-analysis. At least a factual (give or take the impressionistic question about our partners likelihood to enjoy reading SSC) proxy question has a link to reality.

I expect people to confuse their level of intelligence with their natural tendency to be analytical.

Scott comes out and says that’s one of the weak points of the analysis, and I think he’s correct that it is. I think SSC/EA/rationalist populations do map to some place in “analytic” space, but there are certainly other types of analytic people that don’t overlap with this subset. It’s also not clear to me that participation in EA in particular necessarily means a person is highly analytic. Could they simply have read/heard some arguments in favor of EA (“we figure out which charities save the most lives and direct your money accordingly”), decided that it made sense, and then gave their money to charities some particular EA organization put their stamp of approval on? No serious analysis required.

I think the question he really wants to answer is: “should you, friend of Scott or ssc reader with an analytical partner, be worried about your own children”. So he isn’t really looking for whether an effect exists, but rather whether it’s big enough to warrant behavioral changes. Still a very underpowered study, but I think it does a decent job of saying “your kid doesn’t have a 30% chance of getting autism, it’s probably roughly the general population average, chill and live your life”

Endorsed.

@drunkfish

You’re right, but what RGTP_314 was IMHO getting at is that that assumption was obviously untrue to anyone pondering it for more than a minute. If the children of two highly analytical parents had a 30% chance of having autism, we would _know_. We would have known for centuries. There would probably be something in the bible and on the pyramids about how having two highly analytical people have children together is taboo because the child is likely to possessed by demons.

Even if the chance were 10%, we would know, because the effect would be obvious, thus draw interest and given forking paths and publication bias, we’d see studies with an estimate of a 20% effect. Which would then be haggled down somewhat in subsequent studies and we might end with a biased estimate of 13%, but still we would know.

_Any_ substantial effect size would be easy to research (and of enough real world relevance), and thus most likely already be known. It’s only when you get down to a 1-2% increase over ‘normal’ risk (whoever counts as ‘normal’ for that purpose is a tricky question all in itself) that you need large sample sizes, representative samples and noise-free measurements (of analyticalness, of child autism) to have a hope of being estimate the effect. Since Scott’s study fails points two and three of those, and badly the _only_ possible outcome where it would shift our priors would be if by a fluke it ended up producing a vast overestimate (which would then reach significance) and Scott forgetting to think twice about that before posting. As it is, it was dead on arrival.

Andrew Gelman has been criticizing a similar study by Satoshi Kanazawa on parental attractiveness and boy/girl ratio in children since 2006/7. He refers to the general problem as “they are trying to use a bathroom scale to weigh a feather—and the feather is resting loosely in the pouch of a kangaroo that is vigorously jumping up and down”.

https://statmodeling.stat.columbia.edu/2015/04/21/feather-bathroom-scale-kangaroo/

This is my basic argument. That said, I don’t think Scott shouldn’t have bothered with the analysis and the write-up. If he had found something noteworthy, it would have been very interesting. Of course, it would need to be followed up with a study specifically designed to test the hypothesis with a large representative sample yadda yadda yadda. However, I don’t think we should assume that we are already aware of all the large-and-important effects in the world.

So… I agree that it seemed obvious that there isn’t a huge effect, but I disagree that testing for the huge effect was worthless. Mostly, I disagree with his conclusion that failing to detect the effect in a small survey of SSC readers means that there probably isn’t an effect large enough to consider important.

> That said, I don’t think Scott shouldn’t have bothered with the analysis and the write-up.

I’m going to disagree here. There’s a lot of value in publishing null results, even if only to allow other people to not bother inadvertently reproducing the same non-published null result.

Put another way: if someone else has the same concern and review this write-up they will have a better idea of what they are up against. They’re going to have to at least find a methodological flaw or a much larger sample size. They’ll to describe the flaw which would explain why they might find a positive result, or have a much better estimate of the sample size required to power their study to be able to uncover a significant finding.

@Garrett

It was confusing because of the double-negative, but I’m pretty sure @RGTP_314 agrees with you.

@RGTP_314

My point is that ‘if he had found something noteworthy’ it would have to have been an vast overestimate. That’s the only way to get to p<0.05 with small sample size and very noisy measurements.

That's actually a key results of the replication crisis, that all these small fancy studies that get published when they get lucky and file-drawered otherwise are _not_ worth doing, because they just polute the scientific literature with inflated estimates. And waste considerable time and effort of the scientific community until they are eventually corrected.

Re: "I don’t think we should assume that we are already aware of all the large-and-important effects in the world." as far as effects everyone can hypothesize about and which are easily observable, yes, we really are aware of all of them. Or if you want to be nitpicky, maybe the chance is one in a million or less that nobody before you thought to test this effect that's easy to assume and visible to the naked eye, no fancy studies or statistics involved. The exceptions are effects that couldn't exist before today or those connected to a complex theory that ties together disparate observations in a way very few people can.

The only way I could see this being useful is if it was narrowly confined to SCC survey takers and limited to a question like 'given an unrepesentative sample and poor meaurements, should our a priori low belief in _extreme values_ increase or decrease a small bit.' That's something that can usefully be answered with this data.

@Garrett

In a vacuum, I agree with you. In practice, I expect people who run studies woefully underpowered for the range of reasonably to be expected effect size to notice this. And if the ‘result’, ‘duh, we didn’t think about possible effect sizes (and power/sample size)’ then it’s hard to see the value added, because that you shouldn’t run your studies like that is part of every introductory statistics/experimental design book.

I’ve always thought that if there is a correlation among “high-achieving” parents and children with autism, the trait that they had in common was more along the lines of a type of conscientiousness than analytical ability. This is purely based on personal observation and may mean nothing, but it would also seem to be the trait most selected for in recent assortive mating.

I also agree that it can’t be all that direct a connection, because we would have seen it disproportionately in some place like Boston. While I do think there was much more diversity of personalities in marriage until recently, cultures still could be pretty selective towards things like analytical ability, and within those cultures, analytical men tended to go for analytical women. And in many cases in a place like Massachusetts, you’d probably marry someone from the same community, probably the same religious background, generally from a pretty narrow sphere, and it generated unique personality types, but I don’t think there’s much indication of this phenomenon. You got the “Puritans” that Scott has written about, some of whom probably would qualify as on the spectrum, but that’s a different presentation. Writers, reformers, and very religious people tend to marry each other, and at certain times in history we have had social movements that attracted a certain type of person, and in which many members married each other. I feel like the assortive mating effects would be particularly intense here, especially as there were higher rates of marriage and children in general. As far as I am aware, it wasn’t associated with particular risks, beyond possessing the same quirks as the parents.

Wouldn’t it still be valuable to check whether you or your partner have autism yourselves, or a history of autism in your family ? If so, you could very well have a 30% chance of conceiving a child with autism, regardless of your IQ…

This was my assumption, but I think what got me all whiny was that he wasn’t very clear about exactly what he was trying to test. What I would have liked to see is a hypothesis that specifically refers to his actual measures. For example, “I expect to see that SSC readers with kids and sorta/very analytical partners tend to have a higher rate of autistic children than the 2.5% incidence in the US estimated by Kogan et al (2018).”

To be completely fair, all I do all day is read cognitive/neuro/decision-making literature, so when I saw Scott adopt the “short study report” format I immediately donned my grumpy academic hat and started having an internal tantrum when I couldn’t find a formal hypothesis. In the end, the reason I commented was because when I finished reading the post I was left wondering: Wait, what would the data have looked like if Scott’s hunch was supported? I felt like I missed the point and I almost never feel that way when reading SSC posts.

Yeah fair. The reason I landed on that (apparently correct) interpretation was this line in https://slatestarcodex.com/2019/11/13/autism-and-intelligence-much-more-than-you-wanted-to-know/

I think this is what he had in mind when he referred to “the strongest form of the assortative mating hypothesis”. It’s fair to not think one needs that context to read this post though.

inattentive respondents (i.e., people who said they didn’t have a kid with autism then later said they did)

Should those respondents be characterized as less analytical than others?

I don’t remember the survey that well, but I don’t recall getting questioned about this. I vaguely remember questions about children living at home? I have an adult child with autism spectrum disorder. Is it possible that such situations were overlooked?

I’m not sure what you mean by “It seems like p(highly analytical|on autism spectrum) is pretty high, but p(on autism spectrum|is highly analytical) might be much lower.”

Comparing these two to each other is like apple to oranges, so probably not what you meant.

“Pretty high” without some reference to “regular” value also makes little sense, so probably not that neither.

If you meant that P(A|B)>P(A), yet P(B|A)<P(B), then this is impossible due to definition of P(X|Y)=P(X,Y)/P(Y).

So, what did you mean here?

I think he means P(A|B)/P(A) vs P(B|A)/P(B).

Basically that knowing someone has autism tells you a lot about how analytical they are, but knowing how analytical someone is tells you very little about how autistic they are.

One question I have (as a not-at-all-autistic but very analytical person): Is it that:

a. Autistic tendencies -> being analytical

b. Being analytical -> autistic tendencies

c. Some common cause -> being analytical, autistic tendencies

d. Some kind of selection effect like autistic tendencies -> going into an analytical field

For (d), imagine if the only two jobs are salesman or computer programmer and the population is a mix of somewhat-autistic and not-at-all-autistic people. Even if autism has nothing to do with talent at programming, the more autistic you are, the more likely you will end up as a computer programmer, because you can do that job, but you can’t do a salesman’s job.

From personal and anecdotal experience : a combination of a and d.

Full disclosure : I’m going to talk about “high functioning” autism / aspergers here, because that’s what I have experience with.

D.

I tried a non analytical career for 5 years (customer service sector). It didn’t end well. I liked the job well enough, but my social skills meant that I was always doing poorly on evaluations that measured personability. (Is that a word? Well it is now!) By contrast, at my current engineering job, no one cares if I have minor quirks like stimming or not looking people in the eyes or wearing the same five shirts all the time. They only care that I do my job, and do it well. In short, analytical people are much less stressful to work with than the general population.

A.

Some common traits of autism, such as black and white thinking and having an attention for details, lend themselves well to analytical fields.

B/C.

Out of everyone in my office that I interact with regularly (~100 people) there are two that I suspect might have autism. That’s not much higher than the general population. If it were b or c, I’d expect that number to be much higher.

@drunkfish: I think your second paragraph is indeed what Scott is saying. I’m confused by your first paragraph, though. I thought P(A|B)/P(A) and P(B|A)/P(B) were necessarily equal, because both equal P(A∩B), so it wouldn’t make sense to compare those. It would make sense to compare P(A|B) and P(B|A), as Scott originally suggested.

Hmm maybe I got the math wrong too…

How do you write “the information you gain about A from knowing B”? P(A) is what you knew before, P(A|B) is what you know now. Is it… (P(A|B) – P(A)) /P(A) or something?

I agree that it doesn’t make sense to compare those two quantities, but they definitely don’t equal P(A∩B). (Although, in the two examples I worked through, they were equal to each other.) By definition (of conditional probability), P(A∩B) is equal to P(A|B)·P(B). It would be strange if P(B) were, in general, equal to 1/P(A).

The problem in comparing the quantities isn’t that they’re equal, it’s that they’re meaningless. P(A|B)/P(A) does not represent the probability of anything at all — it can’t, because it’s easy for this quantity to be greater than 1. (Consider what happens when P(A|B) = 1)

(Some quick algebra shows that indeed P(A|B)/P(A) and P(B|A)/P(B) are necessarily equal to each other: both are equal to [P(A ∩ B) / (P(A)·P(B))].)

Is it possible for a highly heritable trait to remain constant or diminish in heritability if both parents have it, like the inverse of the common idea of a recessive gene? That seems to be what this study is suggesting is occurring.

A gene which had an effect with one copy but is deadly with 2 copies would do this. Something like an extreme version of sickle cell.

If both parents are Aa, they can have four potential offspring, AA, Aa, aA, aa. The AA fetus dies in utero and they end up with only 66% of their children having the 100% heritable trait that 100% of the parents had.

Scott isn’t actually finding that the trait is negatively heritable though. That’d require looking at the children of specifically autistic responders. He’s just finding that being analytical doesn’t seem to have a strong impact on your children’s autism, which as Scott points out can be easily explained if you don’t assume analytical=slightly autistic.

Agreed, especially with your last paragraph. I would also add that because autism isn’t 100% heritable, we expect that a sample selecting for autistic/analytical people will be higher than normal on the random/environmental component of autism/analyticity, but their children will only be normal on this metric, so their children should be less autistic/analytical than they are.

“only be normal” assumes no correlation between a parents environment and a child’s? Which seems like a stretch. But some regression to the mean in environment is certainly plausible. (this is very nitpicky, sorry)

Suppose it’s partly heritable and partly random–then you should see regression to the mean. If two one-in-a-million geniuses marry and have kids, their kids will not on average be one-in-a-million geniuses.

I’d also speculate that only the relatively milder forms of autism are very compatible with marrying and having children.

I love the SSC survey and I trust the analysis here, but I doubt it has the power to detect an increased-autism-risk effect if one exists– mostly for the reasons Scott mentions: autism is low-probability relative to “analytical personality”, the survey results are noisy, and regression to the mean may outweigh whatever genetic effects they detect.

Oops, I glossed over the disclaimer that John Schilling mentions below, which points out exactly this.

It seems like some commenters have missed this important disclaimer. Scott’s analysis, by his own admission, does not have the power to discern small increases in autism frequency of say 10-20% due to assortive mating, and that is the level of increase we would a priori expect.

But just the ability to rule out large increases of 100-200% or more is useful. Autism rates have increased by 100-200% or more in the past generation or so, and nobody is sure why. This is a matter of real concern. The leading smart theory is probably better reporting, the leading stupid theory is contaminated vaccines, but assortive mating is certainly in the top ten and maybe the top three from what discussion I have seen. If, as the hypothesis goes, our increasingly STEM-oriented society is leading to nerds marrying nerds and producing lots of autistic children, we would really want to know that. Now, we have a data point that says “probably not that”.

Still wants for replication, of course, but thanks to Scott for that one data point.

> If, as the hypothesis goes, our increasingly STEM-oriented society is leading to nerds marrying nerds and producing lots of autistic children, we would really want to know that.

More assortative mating means that more people of similar incomes marry each other; it doesn’t necessarily lead to more nerds marrying each other. Some of the reason assortative mating did not happen in the past was sexism: analytical women still existed, and were probably still more likely to marry analytical men, but the ratio of the income of a 1940s-analytical-woman to a 1940s-analytical-man was much less than a 2020-analytical-woman to 2020-analytical-man.

Also, the selection mechanisms weren’t as well established. A smaller fraction of highly analytical women became engineers or chemists or whatever in 1950 than in 2000, thanks to social pressures.

@caryatis

More traditional societies seem to place less emphasis on having similar personalities than modern societies.

Agreed. I don’t know why you’d limit assortative mating to income. It seems like in contemporary society people are VASTLY more able and interested in finding highly similar partners to themselves across many metrics than they were before the sexual revolution.

That’s not what assortative mating means. Assortative mating is preferential mating between phenotypically similar individuals. The idea that A: “income” is a heritable phenotype and B: it’s the only phenotype we really care about so the whole concept of assortative mating be reduced to “people of similar incomes marry each other”, is one of the more controversial opinions of the Muggle Realists, not an established principle of biology.

Nerdishness is an observable phenotype, and it seems at least as likely to be heritable as income. It is thus fair game for assortative mating. And a recent increase assortative mating for nerdishness is plausible. The oversimplified version is, in the Before Times, people were encouraged to marry their high school sweetheart, and high schools lumped the whole local population in the same classrooms. Now, smart people at least are encouraged to marry no earlier than college, maybe grad school for best results. And we pluck the smart-analytical subset of every community out of those communities, deposit them in either STEM universities like MIT or the culturally distinct STEM departments of general research universities, and say “now start looking around you for your mate”. So, a plausible mechanism for more assortative mating for nerdishness, not for wealth.

Access to universities is significantly correlated with parental income, more so at the very top. The median family income at MIT is twice the national median income. 61% of students are from the top 20% of society. Although compared to the Ivy League, MIT is actually a lot more egalitarian.

Endorsed.

My first guess would be people misreading the question, especially if they filled out the survey in a hurry. I remember answering a similar question as “not severely affected”, assuming it applied to my own experiences with childhood autism and schooling.

In retrospect, I’m probably one of the participants who accidentally reported a phantom child. Sorry about that.

i’m confused by the assumption that having an autistic child isn’t a desideratum.

Scott wrote post about this: https://slatestarcodex.com/2015/10/12/against-against-autism-cures/

i’m disappointed that they haven’t made an attempt to center autism in the last four years.

The population who I expect to potentially change behavior based on this is “Slate Star Codex readers”, so the study population is exactly representative of the target population.

That great, but where do all these references to people outside SSC come from? The conclusion rephrases the question as ‘does assortative mating between highly analytical people significantly increase chance of autism in offspring’, and I see no reference to SSC in there. Replace ‘people’ with ‘SSC readers’ everywhere in the post if you really only meant to generalize to SSC readers.

This is a great argument against issues like “being verbal turns out to be a protective filter” being important, but doesn’t do much to address issues like “filtered out parents too busy with their autistic kids to complete surveys”.

If being a parent of a child with autism affects the probability of continuing to read ssc/take ssc surveys there could be an effect where survey taker parents have children with autism at roughly the population rate but if the childless readers had children those children would disproportionately have autism (and then the parents stop taking the survey).

True, but wouldn’t you expect strong overlap between that and the set of SSC readers who are likely to change their behavior based on a post?

Studies prove: SSC orgies not ill-advised.

Given the gender balance, I’ll pass. (Also my wife would not approve).

Sounds like a version of the El Farol Bar problem?

As the study involved a question about your wife (assuming you did the survey) surely she is welcome to attend as well?

@The Nybbler

That was the joke.

This seems extremely plausible. Claiming to be on the autism spectrum is extremely trendy in the silicon valley tech community, and appears to usually mean “run of the mill introvert who also is a programmer”. Much social bonding appears to center around this shared “autism”. At it’s worst it is used as an excuse to be selectively rude by people who are no where near being autism adjacent.

None of this is intended to be at all offensive to anyone that actually has this condition. For those that do, are you offended by those falsely portraying themselves as such (or at least greatly exaggerating the extent of) or does it help more to have the condition more widely normalized?

People who don’t have autism shouldn’t be describing themselves as “autistic”. Autism has a variety of common symptoms (for lack of a better word). Some of them are considered positive, and some are considered detrimental, to the point of being potentially disabling. It irks me when people off the spectrum start describing themselves as “autistic”, but what they really mean is that they’re highly intelligent, analytical, introverted, and don’t like being around crowds. There’s a big difference between “being around crowds is uncomfortable” and “my sensory sensitivity means that I’m likely to have a meltdown in places with loud noises and people bumping into me”, just as an example.

People who aren’t actually autistic don’t have to deal with masking, or meltdowns from sensory overload, or chronic GI issues (very common in autistic people, exact reason for correlation unknown), or getting frequently turned down for jobs due to their interview skills being slightly “off”.

On a less emotional note, I’m against using any medical diagnosis as an adjective. Words mean things, and redefining a medical condition to have a non-medical meaning is not helpful. I think Scott wrote a post on this, but I can’t remember the title.

I don’t share any of those diagnoses, but fully agree and it drives me crazy. It isn’t just autism, either, this is common with a lot of mental issues. OCD is maybe another of the most popular. It has become extremely trendy to “claim” various mental health diagnoses, which seems like a bad thing to me.

This is the first time I’ve ever seen mention of a correlation between autism and GI issues. Where do you recommend I go to read more?

I don’t have links to specific studies, unfortunately. I learned about the correlation shortly after I was diagnosed with autism and I didn’t bother to bookmark anything. Last I looked into it, the verdict was still out on whether the higher prevalence of GI problems was due to genetics, higher levels of anxiety, more restrictive diets, some combination thereof, or something else entirely.

Googling “autism GI issues” pulls up quite a bit, with varying levels of quality. I tend to side-eye anything mentioning “leaky gut syndrome”, mostly because I’m tired of people telling me that my autism will be “cured” if I just took the grains out of my diet. (I can’t cure my autism, and wouldn’t really want to even if it was possible. Let me eat my sandwiches in peace!)

I did some Googling and nearly everything I was finding from reliable sources was concerning children only, which I find strange.

I am dealing with fairly extreme GI issues and am trying to read everything I can about possible cause pathways and appropriate specialists. This is why I am surprised I haven’t heard of this link previously. I am very curious what the underlying cause is, and which direction it goes.

For what little it’s worth, I am currently grain-free and no more or less autistic than I was previously as far as I can tell.

@DNM

I have scoured the internet and the local library, and have talked to all of my local therapists, and I have yet to find any decent resources for autistic adults. I have my theories on why, though I’ll avoid going into details here because it will just devolve into a rant.

My own mystery GI problem turned out to be Crohns, which is extremely annoying to get a diagnosis for. It’s also annoying to treat. My doctor said “sorry, there are no medications that help. All you can do is keep a food diary and try to manage your symptoms.” Good luck! GI issues are awful.

For what it’s worth, I have a formal diagnosis of Asperger’s (which would now be considered ASD), and as far as I know, I’ve never had a meltdown or suffered from GI issues.

I think part of the problem is that autism doesn’t seem to be a binary category. There’s just people with varying degrees of symptoms.

I do hate when people use “autistic” as an insult or use it to describe unrelated things though.

Autism is definitely a spectrum. I’ve been trying to limit my discussion to the Aspergers side, since that’s the side I have more experience with. (I have my suspicions that Aspergers and the more stereotypical “low-functioning” forms of autism may be two separate things, but that’s a discussion for another time.)

Trust me, you’d know if you had GI issues. I am slightly jealous.

I’ve never had a meltdown in the stereotypical “throwing a tantrum” sense, because my parents made it very clear that tantrums were not a thing I was allowed to do. However, I’ve definitely had meltdowns due to sensory overload. Sometimes they manifest as sobbing in a corner, and sometimes they manifest as self-harm.

@Lord Nelson

An issue is that there exists a substantial group of people with certain problems, but no good label for this. I think it is a bit unfair to get upset at people for picking the best label that actually exists (in other people’s minds).

I personally shy away from calling myself autistic, but in practice this means that I have even less ability to explain what I am to people.

This is false. Masking is what we teach people when we civilize them. Nearly everyone does it to a substantial extent and those who don’t are either ostracized for it or the small percentage of people whose natural behavior is very socially acceptable.

More extreme masking is a common response to (perceiving) strong social disapproval or (severe) abuse*, some of which is in response to atypical behavior by the masking individual. This atypical behavior can have all kinds of causes beyond autism (including suffering from a feedback loop, where people behave atypically because they are treated atypically, which makes them act more atypically).

* Note that these are subjective and some people are much more sensitive to this than others.

‘Autism’ actually means very little, including medically. DSM-5’s criteria for autism are extremely shitty. They look a lot for symptoms that can be (indirectly) caused by being atypical in ways other than autism or that can be caused by developmental problems (including those caused by being raised in a shitty environment and/or being victimized). The DSM attempts to reduce this issue by demanding that “symptoms must be present in the early developmental period,” but this ignores that the child’s environment can be shitty during the early developmental period and/or that ‘atypical behavior-> abuse’ can happen early in life.

The DSM also tries to reduce this issue with another criteria: “These disturbances are not better explained by intellectual disability (intellectual developmental disorder) or global developmental delay.” This ignores that a child’s development can be impaired in non-global ways, without autism being a cause.

These criteria make it very easy to confuse being very thing-oriented (aka nerdy) for being autistic.

My apologies on masking. I’d only ever heard it used in the autistic community, so I assumed it was a term that was coined by the autistic community.

Yeah, I have Opinions on the DSM’s criteria for autism, which can be summed up with “the way the DSM handles it is not great”. But I will stand by my statement that being autistic is not just being thing-oriented or nerdy, and that I don’t think it’s helpful to use “autistic” as an interchangeable term in those cases. I know people who are very nerdy, who have hobbies that could be considered “special interests” or obsessions, but who are still not “autistic” because they do not struggle with understanding basic social rules.

I think for future studies of this type, you should exclude autistic parents from your dataset. It could be that the causal diagram has a node for “is autistic” that positively influences both being analytical and having autistic children, which could cause us to believe being analytical directly causes having autistic children, when in fact it’s just a spurious association.

I had issues with a couple of your wordings. First, you said

It sounds like you are saying that all 144 children are phantom, even though only 71 are. This didn’t seem too bad, as I think I got what was going on from context.

Later, you said

When reading “when people have property P, the elevated risk of trait X is less than Y percentage points” out of context, I would probably think “people with P have at most a Y% chance of X”. “Elevated risk” parses to me as “new final risk number, after elevation has been applied”.

But based on the other numbers you stated, it seems like that interpretation is wrong. My best guess for what you actually mean is that there is a 95% chance that the children of highly analytical parents have a 5.5% (i.e. the 2.5% population baseline plus an elevation of 3%) chance of having trait X.

Judging from the comments, SSC commenters tend to have very strong logical skills, and tend to be be more deeply than broadly knowledgeable. I.e., they tend to know a huge amount about their favorite subjects, but don’t know as much as their IQs might predict about a broad range of topics.

I’m not an expert at reading scientific studies.

But, in the blue/red/green graph, is it weird that the 95% confidence interval extends to 0?

I have read a lot of agricultural studies about the effects of nutrition,

exposure to chemicals, effects of inbreeding, and the like.

They can do a lot of things to goats and rats that can’t be done to people… But I don’t have any reason to believe the generalized conclusions are really all that different between “people” and “animals”…

An example… Prenatal malnutrition effects can persist a LONG time in animals… Some studies show it takes 4 generations with proper prenatal nutrition to get rid of developmental problems this sort of thing causes…. Exposure to nasties/toxins does much the same thing – it can take 4+ generations of “Clean” to undo the problems caused by the exposure…

I have this suspicion that full on Autism falls into this category… And that may be why the statistics on this seem relatively confusing or vague….

For instance – a confounding factor THIS generation has is that our parents/grandparents ate food which was treated with lead, arsenic, nicotine, and benzene based fungicides, herbicides, and insecticides. This stuff wasn’t really completely “Out” of common use until the 1980’s…. So probably 80% of our parents and half of the folks reading this blog ate food treated with these nasties before having their own kids… And this exposure in the 1960’s and 70’s probably had something to do with the “Spike” in Autism seen in the 1980’s because their mothers and fathers were consuming foods treated with harmful chemicals and heavy metal poisons while having children…

Ironically – what this says is that what kids and child-bearing age adults eat is FAR more critical than “Older folks”…. Yet who eats straight junk food vs who gets put on dietary restrictions? Right… We feed all the trash to the kids and young adults because it’s cheap and easy… We put older folks on dietary restrictions because of their health problems…

But so it goes…

Do highly analytical tech workers actually marry other highly analytical tech workers? I know a handful of couples like this who met during CS undergrad, but there are pretty strong norms against this kind of socialization at work, and in the non-work but vaguely professional contexts where this crowd congregates.

My SWE coworkers mostly meet women at nightclubs, which probably skew towards the more extroverted tech workforce (sales, marketing, HR) if tech is significantly represented at all.

I don’t think that’s generally true. Around here, it was uncontroversial and celebrated when one of my rocket-scientist employees married one of her rocket-scientist colleagues (on Werner von Braun’s birthday, for maximum rocket-scientist nerdiness points). More generally, workplace romances lead to ~15% of marriages in the contemporary United States.

Throw in college and meatspace social networking (mostly built at college and work, in the relevant age range), and you’re above 50%.

Not to stereotype, but if your coworkers are willingly going to a nightclub of their own free will, they don’t have the broad autism phenotype and there is no reason to expect they’d be any more likely to have autistic children than the general population.

Which is why people are questioning whether this analysis (of analytical people who may or may not be anywhere on the autism spectrum and whether they are more likely to have autistic children) isn’t terribly useful.

You almost never see two “Super techies” ending up together.

The classic pairing is (man) Engineer/Scientist/accountant + (woman) school teacher or nurse or vice versa (woman) engineer/accountant/scientist + (man) construction worker/tradesman.

One main reason is simply career compatibility. One spouse generally has a “Good job which is not easy to replace without relocation” while the other spouse generally has an “easy to replace anywhere we relocate job”… One engineer friend of mine with a good job married another engineer with a good job… They spent the 1st 5 years of their marriage living 400 miles apart and miserable because it. Her job paid a lot more so he finally quit his job and “Dropped down” into a sales position with a local AC distributor so they could sleep in the same bed and have kids… This guy was super smart and talented – he was top 5 in his engineering class in a well known Engineering university.. He is now the local branch manager at the AC distributor…

Their kids have zero autism spectrum….

Being an adult in Real life means trade-off’s…

I can think of half a dozen examples off the top of my head, in my circle of professional colleagues, and none of them have ever had to do a long-distance relationship. People with high-end technical skills, and not pursuing the nigh-unicorish goal of a tenure-track academic career, generally don’t imagine they must take the next job I am offered for there may never be another. Maintaining a marriage or stable long-term relationship, mostly just requires not taking jobs in remote locations with only one relevant employer unless that employer has a suitable job for both partners.

I think this is something of a malfunction in the thought of some people, that people who have some disability are “compensated” for some way, so created a false pattern in their mind that autism boosts analytical skills.

Real life is not balanced like a game; there’s no compensation for being hit with a disability.

Thus, I’m not surprised by the result here.

Age is another probable factor. People are having children later in life.

“People who hadn’t previously reported any children with autism gave answers other than N/A for this one, which was confusing.”

The wording of this question says “consider your child with autism.” Did all of the previous questions ask about children *diagnosed with* autism?