[Thanks to Marco DG for proofreading and offering suggestions]

I.

Several studies have shown a genetic link between autism and intelligence; genes that contribute to autism risk also contribute to high IQ. But studies show autistic people generally have lower intelligence than neurotypical controls, often much lower. What is going on?

First, the studies. This study from UK Biobank finds a genetic correlation between genetic risk for autism and educational attainment (r = 0.34), and between autism and verbal-numerical reasoning (r = 0.19). This study of three large birth cohorts finds a correlation between genetic risk for autism and cognitive ability (beta = 0.07). This study of 45,000 Danes finds that genetic risk for autism correlates at about 0.2 with both IQ and educational attainment. These are just three randomly-selected studies; there are too many to be worth listing.

The relatives of autistic people will usually have many of the genes for autism, but not be autistic themselves. If genes for autism (without autism itself) increase intelligence, we should expect these people to be unusually smart. This is what we find; see Table 4 here. Of 11 types of psychiatric condition, only autism was associated with increased intelligence among relatives. This intelligence is shifted towards technical subjects. About 13% of autistic children (in this sample from whatever social stratum they took their sample from) have fathers who are engineers, compared to only 5% of a group of (presumably well-matched?) control children (though see the discussion here) for some debate over how seriously to take this; I am less sure this is accurate than most of the other statistics mentioned here.

Further (indirect) confirmation of the autism-IQ link comes from evolutionary investigations. If autism makes people less likely to reproduce, why would autism risk genes stick around in the human population? Polimanti and Gelemter (2017) find that autism risk genes aren’t just sticking around. They are being positively selected, ie increasing with every generation, presumably because people with the genes are having more children than people without them. This means autism risk genes must be doing something good. Like everyone else, they find autism risk genes are positively correlated with years of schooling completed, college completion, and IQ. They propose that the reason evolution favors autism genes is that they generally increase intelligence.

But as mentioned before, autistic people themselves on average have lower intelligence. One study found that 69% of autistic people had an IQ below 85 (the average IQ of a high school dropout). Only 3% of autistic people were found to have IQs above 115, even though 15% of the population should be at this level.

These numbers should be taken with very many grains of salt. First, IQ tests don’t do a great job of measuring autistic people. Their intelligence tends to be more imbalanced than neurotypicals’, so IQ tests (which rely on an assumption that most forms of intelligence are correlated) are less applicable. Second, even if the test itself is good, autistic people may be bad at test-taking for other reasons – for example, they don’t understand the directions, or they’re anxious about the social interaction required to answer an examiner’s quetsions. Third, and most important, there is a strong selection bias in the samples of autistic people. Many definitions of autism center around forms of poor functioning which are correlated with low intelligence. Even if the definition is good, people who function poorly are more likely to seek out (or be coerced into) psychiatric treatment, and so are more likely to be identified. In some sense, all “autism has such-and-such characteristics” studies are studying the way people like to define autism, and tell us nothing about any underlying disease process. I talk more about this in parts 2 and 3 here.

But even adjusting for these factors, the autism – low intelligence correlation seems too strong to dismiss. For one thing, the same studies that found that relatives of autistic patients had higher IQs find that the autistic patients themselves have much lower ones. The existence of a well-defined subset of low IQ people whose relatives have higher-than-predicted IQs is a surprising finding that cuts through the measurement difficulties and suggests that this is a real phenomenon.

So what is going on here?

II.

At least part of the story is that there are at least three different causes of autism.

1. The “familial” genes mentioned above: common genes that increase IQ and that evolution positively selects for.

2. Rare “de novo mutations”, ie the autistic child gets a new mutation that their non-autistic parent doesn’t have. These mutations are often very bad, and are quickly selected out of the gene pool (because the people who have them don’t reproduce). But “quickly selected out of the gene pool” doesn’t help the individual person who got one of them, who tends to end up severely disabled. In a few cases, the parent gets the de novo mutation, but for whatever reason doesn’t develop autism, and then passes it onto their child, who does develop autism.

3. Non-genetic factors. The best-studied are probably obstetric complications, eg a baby gets stuck in the birth canal and can’t breathe for a long time. Pollution, infection, and trauma might also be in this basket.

These three buckets and a few other less important factors combine to determine autism risk for any individual. Combining information from a wide variety of studies, Gaugler et al estimate that about 52% of autism risk is attributable to ordinary “familial” genes, 3% to rare “de novo” mutations, 4% to complicated non-additive genetic interaction effects, and 41% “unaccounted”, which may be non-genetic factors or genetic factors we don’t understand and can’t measure. This study finds lower heritability than the usual estimates (which are around 80% to 90%; the authors are embarrassed by this, and in a later study suggest they might just have been bad at determining who in their sample did or didn’t have autism. While their exact numbers are doubtful, I think the overall finding that common familial genes are much more important than rare de novo mutations survives and is important.

Most cases of autism involve all three of these factors; that is, your overall autisticness is a combination of your familial genes, mutations, and environmental risk factors.

One way of resolving the autism-intelligence paradox is to say that familial genes for autism increase IQ, but de novo mutations and environmental insults decrease IQ. This is common-sensically true and matches previous research into all of these factors. So the only question is whether the size of the effect is enough to fully explain the data – or whether, even after adjusting out the degree to which autism is caused by mutations and environment, it still decreases IQ.

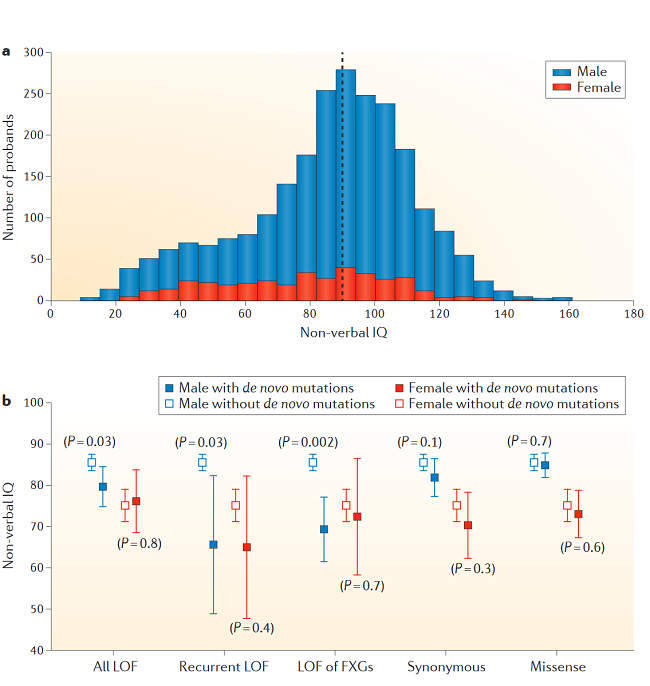

Ronemus et al (2014) evaluate this:

They find that even autistic people without de novo mutations have lower-than-average IQ. But they can only screen for de novo mutations they know about, and it could be that they just missed some.

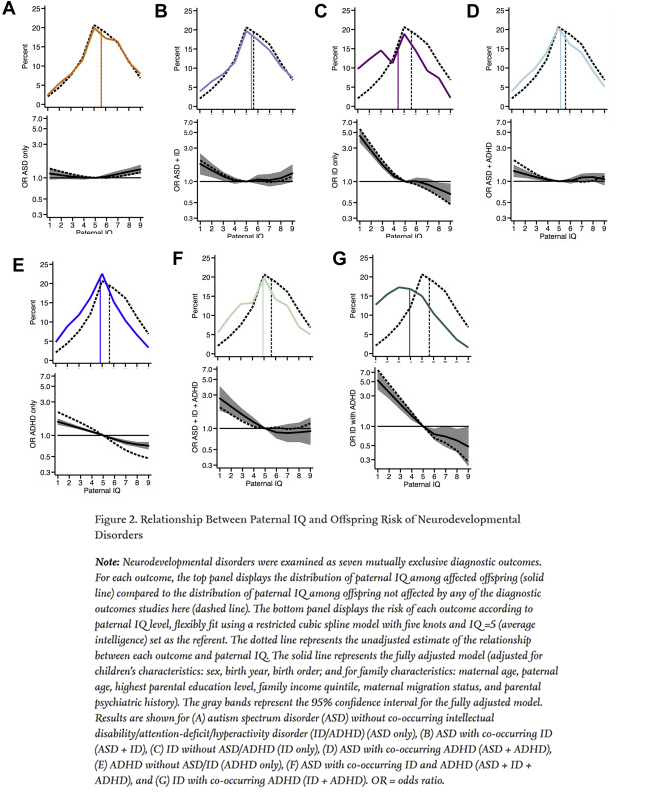

Here’s another set of relevant graphs:

This one comes from Gardner et al (2019), which measures the cognitive ability of the fathers of autistic people and disaggregates those with and without intellectual disability. In Graph A, we see that if a child has autism (but not intellectual disability), their likelihood of having a father with any particular IQ (orange line) is almost the same as the likelihood of a neurotypical child having a father of that IQ (dotted line). Disguised in that “almost” is a very slight tendency for fathers to be unusually intelligent, plus a (statistically insignificant) tendency for them to be unusually unintelligent. For reasons that don’t entirely make sense to me, if instead we look at the likelihood of the father to be a certain intelligence (bottom graph, where dark line surrounded by gray confidence cloud is autistic people’s fathers, and dotted line is neurotypical people’s fathers) it becomes more obvious that more intelligent people are actually a little more likely to have autistic children (though less intelligent people are also more likely.

(remember that “no intellectual disability” just means “IQ over 70”, and so many of these not-intellectually-disabled people may still have low intelligence – I wish the paper had quantified this)

Graph B is the same thing, but with people have have autism with intellectual disability. Now there is a very strong effect towards their fathers being less intelligent than usual.

This confuses me a little. But for me the key point is that high-intelligence fathers show a trend (albeit not significant in this study) to be more likely than average to have children with autism and intellectual disability.

These questions interest me because I know a lot of people who are bright nerdy programmers married to other bright nerdy programmers, and sometimes they ask me if their children are at higher risk for autism. While their children are clearly at higher risk for autistic traits, I think they want to know whether they have higher risk for the most severe forms of the syndrome, including intellectual disability and poor functioning. If we take the Ronemus and Gardner studies seriously, the answer seems to be yes. The Gardner study seems to suggest it’s a very weakly elevated risk, maybe only 1.1x or 1.2x relative risk. But the Gardner study also ceilings off at 90th percentile intelligence, so at this point I’m not sure what to tell these people.

III.

If Ronemus isn’t missing some obscure de novo mutations, then people who get autism solely by accumulation of common (usually IQ-promoting) variants still end up less intelligent than average. This should be surprising; why would too many intelligence-promoting variants cause a syndrome marked by low intelligence? And how come it’s so inconsistent, and many people have naturally high intelligence but aren’t autistic at all?

One possibility would be something like a tower-vs-foundation model. The tower of intelligence needs to be built upon some kind of mysterious foundation. The taller the tower, the stronger the foundation has to be. If the foundation isn’t strong enough for the tower, the system fails, you develop autism, and you get a collection of symptoms possibly including low intelligence. This would explain low-functioning autism from de novo mutations or obstetric trauma (the foundation is so weak that it fails no matter how short the tower is). It would explain the association of genes for intelligence with autism (holding foundation strength constant, the taller the tower, the more likely a failure). And it would also explain why there are many extremely intelligent people who don’t have autism at all (you can build arbitrarily tall towers if your foundation is strong enough).

I’ve only found one paper that takes this model completely seriously and begins speculating on the nature of the foundation. This is Crespi 2016, Autism As A Disorder Of High Intelligence. It draws on the VPR model of intelligence, where g (“general intelligence”) is divided into three subtraits, v (“verbal intelligence”), p (“perceptual intelligence”), and r (“mental rotation ability”) – despite the very specific names each of these represents ability at broad categories of cognitive tasks. Crespi suggests that autism is marked by an imbalance between P (as the tower) and V + R (as the foundation). In other words, if your perceptual intelligence is much higher than your other types of intelligence, you will end up autistic.

It doesn’t really present much evidence for this other than that autistic people seem to have high perceptual intelligence. Also, it doesn’t really look like autistic people are worse at mental rotation. Also, the Gardner paper has analyzed autistic patients’ fathers by subtype of intelligence, and there is a nonsignificant but pretty suggestive tendency for them to have higher-than-normal verbal intelligence; certainly no signs of high verbal intelligence preventing autism. I can’t tell if this is evidence against Crespi or whether since all intellectual abilities are correlated this is just the shadow of their high perceptual intelligence, and if we directly looked at perceptual-to-verbal ratio we would see it was lower than expected. Also also, Crespi is one of those scientists who constantly has much more interesting theories than anyone else (eg), and this makes me suspicious.

Overall I would be surprised if this were the real explanation for the autism-and-intelligence paradox, but it gets an A for effort.

Conclusions

1. The genes that increase risk of autism are disproportionately also genes that increase intelligence, and vice versa (~100% confidence)

2. People diagnosed with autism are less intelligent than average (~100% confidence, leaving aside definitional complications)

3. Some of this effect is because autism is caused both by normal genes and by de novo mutations and environmental insults, and the de novo mutations and environmental insults definitely decrease intelligence. Every autism case is caused by some combination of these three factors, and the more it is caused by normal genes, the more intelligence is likely to be preserved (~100% confidence)

4. This is not the whole story, and even cases of autism that are caused entirely or mostly by normal genetics are associated with unusually low IQ (80% confidence)

5. This can best be understood through a tower-versus-foundation model where higher intelligence that outstrips the ability of some mysterious foundation to support it will result in autism (25% confidence)

6. The specific way the model plays out may be through perceptual intelligence out of balance with verbal and rotational intelligence causing autism (3% confidence)

(The post is awesome, here’s a few errata, feel free to delete this after reading.) The line here has an extra close-paragraph symbol

> (though see the discussion here) for some debate over how seriously to take this; I am less sure this is accurate than most of the other statistics mentioned here)

which I assume is the one missing from the later section here

> (which are around 80% to 90%; the authors are embarrassed by this, and in a later study suggest they might just have been bad at determining who in their sample did or didn’t have autism. While their exact numbers are doubtful, I think the overall finding that common familial genes are much more important than rare de novo mutations survives and is important.

Also, “IQ over 70” should be ““IQ under 70”, and “people have have autism” should be “people who have autism.

More errata, I think:

I don’t think this paragraph fits the note in the image. First, doesn’t the note say that the bottom graph (for each letter) is the likelihood that a father of x IQ will have a child with the specified outcome? And second, doesn’t it say that in the bottom graph, the dotted and solid lines represent unadjusted and adjusted estimates, respectively?

I’ve heard stories of autistic children sometimes regressing in development around 2 years old, e.g. children who previously had normal or even remarkable verbal abilities for their age suddenly “losing words”. Maybe this is a “tower collapse” event.

This pattern is not uncommon (my son followed this trajectory), and is partly responsible for the even less uncommon belief that vaccines cause autism, because the regression coincides with vaccination.

Other possible explanation(s): Some kind of anxiety about doing things wrong, combined with worrying about whether one is “supposed” to be able to do a thing yet. As an example of the latter… there was a time when I was in math class when we’d started learning about simple equations with variables (4n + 2 = 3n + 5 or whatever) but we hadn’t yet learned about adding things to both sides (I think we were just supposed to guess and check). I’d figured out myself how to do that, but tried to hide that I knew how because I thought I wasn’t supposed to know yet. (Then also add to that the fact that people making a big deal out of “Wow you can do this thing!” can be super unpleasant…)

In primary school, for a while we used to have daily spelling tests, where we had to spell ten words. If we got 10/10, we’d get a gold star, and, if 9/10, a silver star. I always used to get one word wrong on purpose because I preferred the silver stars. I still sometimes feel bad about whether that ended up slightly ruining some sort of investigation into which methods of teaching spelling were better or something like that. It would not surprise me if a lot of non-neurotypical children were doing similar things, and that it poses genuine problems for studies like those discussed above.

Interesting. For what it’s worth, I was diagnosed with Aspergers (which has now been folded into autism) at age 12 and as part of the diagnosis they did an IQ test with a “processing IQ” component and a “verbal IQ” component, and although the documents I have don’t list the actual scores, the result is referred to in the documents as being very high in the verbal component and very low in the processing component.

Has anyone here actually met a highly intelligent person who is genuinely normal? Not just running an emulation of “normal” to deal with other people?

Yes. Generally high end career civil servants and similar.

Terrifyingly competent and motivated, shockingly good with people, and with few visible mental issues. It’s possible they just have a very good emulation that never slips even in casual situations, but at some point that basically merges with normal.

This is interesting to me, since I am on a career path to become a high end career civil servant, GS-12 at 25 years old for those that know what that means, and I am anything but normal. I’m somewhere on the autism spectrum and have high levels of anxiety. I am able to emulate being normal very well at work, but horrible in casual settings. This has held me back at networking events, but overall, there is some tolerance for being abnormal out of the office. I would say half of the up and coming civil leaders have hints of being abnormal. What will be interesting to see if we get weeded out before getting close to the top, and if the breakdown will stay the same. Fortunately, at home, I can act how I want, which recharges me significantly.

Strongly agree. GS-14 speaking, and I’m not exactly normal either. The best civil servants get an extra allowance of weirdness points to allocate as necessary.

From a certain perspective, it merges with normal.

From another…

If I suggest autism is effectively what we call people whose… mental resolution (in the sense of pixels per inch) is too high, would that make sense to you?

This seems like circular logic to me. By the same rationale, you could say that no one is normal, and everyone is simply running a mental emulation.

You’re starting with the premise “intelligence is incompatible with normality” and then reflexively dismissing all evidence to the contrary with “they’re not really normal, they’re just pretending.” Which is 1.) completely unfalsifiable, and 2.) could equally be applied to people who aren’t especially intelligent.

This is true in a sense, but also alters what we mean by “normal”.

Normal is being concerned enough with appearing normal to try being normal, yes.

I notice a lot of people confuse normality with charisma. Having charismatic superpowers isn’t “normal”, and I suspect requires being sufficiently unconcerned with opinion – sufficiently thing-oriented – so as to cease to be normal.

How exactly are you defining “normal”? A lot of people are using social aptitude as a proxy because that’s at least something measureable (at least in concept, if not in practice). Normality is just too vague to be quantifiable.

Your argument also seems tautological to an extent; if you’re defining “normal” as “someone who thinks like a normal person,” that’s basically the equivalent of describing an object as being shaped like itself. It also becomes meaningless to say that “no highly intelligent people are normal,” since by definition, highly intelligent people will think in different ways than people with average intelligence.

You could also define “normal” as simply referring to a lack of explicit mental illnesses or emotional problems. But then the answer to your question becomes so obvious that it’s hardly worth asking in the first place; there are countless people who are highly intelligent without suffering from any kind of psychological condition or personality disorder or mental/emotional instability.

I had a professor once whose research thesis was basically this applied to language. The idea is that autistic children have more and finer-grained category boundaries, causing them to over-differentiate similar phonemes that most speakers use interchangeably. She hoped to use this theory to explore why some autistics show delayed language acquisition.

Umm, what? I used to live in the DC area and still work with the civil service in my current job.

Obviously it cannot be 100%, but I have not yet encountered one that isn’t a narcissist or what the internet calls an “autist”. James Comey’s twitter and book are exactly what I’d expect from a career civil service person. Naive, narcissistic, completely detached from human interaction. These are the people that make the Turing test invalid, you’d think they were the chatbot.

Would you mind clarifying what you mean by “narcissist?” I mean, if you go with The Last Psychiatrist’s standards we are basically all narcissists and to some extent the claim “Comey is a narcissist” loses meaning.

The bit about Comey honestly just seems like partisan sniping to me. The odds of him actually having Narcissistic Personality Disorder or any kind of Autistic Spectrum Disorder are close to 0. It’s highly unlikely for someone with either of those conditions to become the Director of the FBI.

I am not saying they have the full disorder (and no its not a partisan snipe, except to the extent that being very skeptical of the US bureaucratic class is partisan). I am simply saying that when you encounter lots of GS11+ people they are exactly like Comey. That’s probably how he got to that level. He is the most Civil Servicy person around. They get offended more if you question them than normal lawyers do, they have the 4chan-y social awkwardness that those communities jokingly call “autism”, etc.

Its a highly abnormal subset of people. Regarding Narcissim, the first website I pulled up had these as the first 3 symptoms:

* Have an exaggerated sense of self-importance

* Have a sense of entitlement and require constant, excessive admiration

* Expect to be recognized as superior even without achievements that warrant it

These 3 have a near 100% incidence rate among civil service employees that I’ve had to interact with.

People at the higher end of the corporate ladder that I’ve met were very intelligent and also seemed generally normal, though of course they had much higher-than-normal ambition, stamina, and interest in their business.

Beware Simpson’s Paradox. Plenty of people are both smarter and more charismatic than us. We just rarely see them because they don’t hang out with us losers.

Within our filter bubble, people have similar levels of status, so they can be smart but not charismatic or charismatic but not smart. We don’t let people who are neither smart nor charismatic hang out with us, and people who are both smart and charismatic don’t want to hang out with us.

You underestimate the potential of a good emulation, I think.

I’m pretty sure that at some point the emulation efficiency hits diminishing returns- that it’s not “emulations all the way up,” in other words.

There’s no reason to assume that every intelligence-enhancing trait necessarily increases “weirdness.” And so, we’d expect that not every person blessed with a strong combination of intelligence-enhancing traits is going to have an excess of weirdness that they have to brute-force emulate their way around.

Some, yes; all, no.

Well, I think it’s certainly a reasonable possibility, which in my experience appears to be true, that beyond a certain point, intelligence either directly causes ‘weirdness’ or is reliant upon it as a foundation. Either way, I don’t think you can have one without the other above a certain level.

I guess it depends on how you define ‘weirdness’; I define it as “having interests, beliefs, or though processes that are significantly different than most people” I don’t think I’ve encountered any extremely intelligent people for whom none of the above are the case.

If your definition of ‘weirdness’ includes beliefs and interests, then almost by definition anyone whose underlying cognition is unusually effective or ineffective will be ‘weird.’ Thus, “I can’t think of anyone who’s very intelligent and not weird” ceases to be meaningful.

For purposes of a discussion of this, I think it’s best if we restrict ourselves to unusual behaviors. Insofar as autism has a coherent definition, it is a category that embraces a variety of behavioral and neural processing anomalies.

Thus, the question under discussion becomes “does every highly intelligent person have some of these autism-linked genes, or are there other paths to high intelligence that do not involve these genes?”

Agreed. There are plenty of incredibly smart and simultaneously charismatic people out there. There are maybe as many as 1000 of them in the Western world, and none of them would want to ever hang out with us — because they are smart enough to know that their time would be better spent managing their billion-dollar corporations and/or governments.

That figure seems very low to me, though it depends what exactly you define as “incredibly smart” and “incredibly charismatic.” If we take “incredibly” to be synonymous with top percentile, there would be 75 million people in the world who are incredibly intelligent. Assuming that intelligence is neither positively nor negatively correlated with social skills, that means 1% of those 75 million people would also be in the top percentile for social aptitude, for a total of 750,000 people. The Western world (taken to mean Europe and the Anglosphere) comprises roughly 1/6th of the global population, which means there should be about 125,000 Westerners who are both incredibly smart and incredibly charismatic. Of course, since intelligence and social aptitude seem to have a slight positive correlation, the real number might be closer to 150,000 or 200,000.

I think top 1% is too low a bar for “incredibly”. Someone at the 99.0 percentile for intelligence would probably seem quite mediocre by SSC standards.

I strongly doubt that. And yes, I know the survey showed that the average SSC reader had an IQ of 138, but I’m extremely skeptical of that finding too. I suspect a lot of people who answered the survey were giving scores from IQ tests they took as children, or from internet tests of dubious quality. And at least a few of them were probably just lying outright.

But if you want to redefine “incredible” to mean the top 0.1 percent of the population, then yes, Bugmaster’s guess would be roughly accurate: There’d be approximately 1,250 people who were both incredibly smart and incredibly charismatic in the Western world, or maybe 1,500-2,000 if you assume a minor positive correlation between being intelligence and being socially adept.

I think somewhere in the 90s percentile of IQ is plausibly normal by SSC standards.

I don’t think 99% would stand out here, but I don’t think it’d quite be mediocre either.

The differences between 99% and 99.5% get swamped by other differences between people within that group in traits like energy or perseverance or whatever. What will really make someone come off as intelligent within that group is going to be something like 99% IQ plus 99% along that other stuff. Energy/perseverance/drive and other harder to measure factors.

Why do people keep thinking charisma is normality, out or curiosity? Is it because that is a trait many people here associate with passing for normal?

I’m really curious, how many people identify with this statement? I feel like unless your definition of “normal” includes “non-highly intelligent” this is just so far from true.

I don’t know their actual IQs, but I’m very confident a lot of people in my bubble are nice, funny, enjoyable, sports-watching people with 99% intelligence.

Maybe I just don’t understand what you mean by normal. Could you elaborate?

Hrm. Perhaps it will help if I ask a question.

How much effort do people, particularly young people, put into being “normal” – that is, into fitting in?

Maybe one bias from my statement is I’m young, and many of my smart friends are also young. I imagine the effort you put into fitting in goes down as you get older. Good clarifying question.

I’m going to interpret “fitting in” as “being liked.”

A lot of the super smart people I know also seem super interesting — either being very funny, uniquely talented, or engaging. The talented ones don’t seem to put extra effort into being impressive for other’s sake. The other two options I guess take effort, but I’d say it’s effort that they enjoy putting in, because they enjoy the rewards (friendship, novel socializing, etc.).

So in that sense, maybe it’s just a phrasing problem. Do a lot of super smart people play the game? I’d say so. But many do it for positive outcomes versus negative pressure, which is how I interpreted your question.

Hrm. I think you’d need to ask them about their internal experiences, but I’d guess a lot of the people you find unusually functional aren’t putting a lot of effort into fitting in.

Struggling to describe this. Normal includes insecurities, anxieties, caring what other people think. Take these away and you arrive at something that seems like an effortless confidence and freedom. I’d guess the funny people can be funny even when their jokes bomb, because they can make their failed jokes into a joke at their own expense?

Dammit, I was nodding along until you threw in sports-watching.

(:D Sorry, couldn’t resist the quip; please carry on.)

I’m not sure what you mean by normal. I’ve certainly known highly intelligent people who did not seem to be crazy or disfunctional in any obvious way. Highly intelligent people are likely to have different interests, read and talk about different things, than average people–does that make them not normal?

FWIW, I know a few bona-fide genius-level people; on the order of “Ph.D. in particle physics at age 15, millionaire at age 30” type of stuff. By and large, they find conversations with non-genius people extremely boring, because they can predict exactly what the other person will say long before he says it. For this reason, they don’t tend to hang out with normal people much.

You might want to adjust for inflation. A PhD in particle physics at 15 is incredibly impressive, but a programmer starting out of college at an FAANG who saves a bit will be a millionaire by 30.

Well, in my case it was a single person who did both…

Are you sure any of that is a real thing?

If you are an expert in X, and the popular understanding of X is X’, you will end up having the exact same conversation about X every time. It would be an excellent skill for a teacher.

(I have “predicted” conversations, but only because the other person forgot we already had it. I then play out both parts of the conversation from memory as their mouth gapes open.)

Honestly, your genius doesn’t sound very good at digging into people. He (I presume) seems to be a bad conversationalist, likely through lack of practice. It’s not difficult to guess what someone’s response would be to many chit-chat topics.

This reminds me of something a past friend mentioned. This friend had been working for many years with Leroy Hood. During a conversation on something or other he told my friend that he knew what my friend was going to say, then ended up saying “that’s not what I’d thought you’d say” afterward. Hood got his M.D. at 25/26 and Ph.D. at 29/30, so might not be of the caliber of your acquaintance, though.

Hard to specify. “I know it when I see it” and all that.

I guess in a context-specific sense, normal is being defined as not-autistic?

There was definitely a sperg-normie dynamic on my last work team, all highly intelligent. The normies were not spergs running emulations, they’d have the same confused look whenever we sperged-out about something that we had when they talked about sportsball.

Why do you think they aren’t sperging out about sportsball?

Sure, most of them. If you mean extraverted, no small number.

Of course people like that exist. Intelligence and social aptitude don’t seem to be positively correlated, at least not very strongly, but they’re definitely not negatively correlated. If anything, there’s a slight positive correlation between the two. (That said, it becomes an incredibly strong correlation if you’re taking mentally disabled people into account, as people with IQs below 70 tend to have extremely poor social skills.)

As for my own personal experience, I’ve found that people with high conceptual intelligence (as opposed to mathematical intelligence) tend to be more charismatic. I’ve known people who were very mathematically and/or technically inclined who had poor social skills. But the ability to notice patterns in the world, analyze phenomena and their causes/effects, understand highly complex and abstract concepts, and make connections between things all seem to be correlated with higher levels of social awareness and persuasive ability.

I work with with a lot of very smart people, and have throughout my career. Most are weird in the sense of having uncommon interests (reading history or science books or studying languages for fun, say), but most seem pretty normal in terms of personality and affect and such. I’d say the people in my field are shifted about half a sigma toward introverted, toward socially awkward, and toward tending to become obsessive about their interests/hobbies, but that leaves a lot of people who’d seem pretty normal in most ways. My office mate is a big sports fan who cares a lot about his yard and house and is a fairly partisan Democrat…and who’s also a mathematician who plays folk music and speaks several languages. Most of my coworkers (except for the youngest ones) are married, and many have children. They’re often chatting about the latest sportsball game or what their kids are doing or their vacation plans–conversations that wouldn’t seem unusual anywhere in the US. Other times, the conversations would seem weird as hell in most places–discussions of physics or evolution or game theory or genetics or whatever, with a high background level of assumed knowledge.

Most successful businessmen. My current boss. My bosses at my last job (normal modulo their ethnic origin). A couple of property developers I’ve worked with.

I’m not sure how “normal” she is, but an acquaintance through RenFaire is head of some Army Corps of Engineers office in the Bay Area, and she’s one of the very few people I consider noticeably more intelligent than me.

Most genuinely intelligent people are also fairly charismatic. Yes their interests and opinions are often eccentric, but they are self-aware of this and do not have problems navigating everyday interactions.

People running ‘an emulation of normal’ are usually not staggeringly intelligent. Social relationships are not difficult and people who cannot navigate them are displaying a serious deficit. They may also have eccentric opinions or interests but they’re more likely to pursue them obsessively or compulsively without good reason, and they have trouble with self-awareness and awareness of others.

Preoccupation with what’s ‘normal’ and whether you are ‘normal’ is a sign of mediocrity in my experience (though it’s not terminal). Brilliant, productive people don’t spend time either wishing to be normal, wishing to be different, or obsessing how they are different from ‘normal.’ They’re simply too busy getting things done for a triviality that reduces to dumb averages to matter to them.

If the IQ/autism risk genes are being selected for, we should be seeing more top-level geniuses each generation (I’m very skeptical of this) and more autistic children (this half checks out).

That sounds like the Flynn effect, although the Flynn effect generally isn’t considered genetic.

Except that from the sound of it, the IQ/autism risk genes are…

[DANGER, OVERSIMPLIFICATION FOLLOWS]

…a sort of arrangement where if you pick up to four of them you get enhanced intelligence, five or six and you get high-functioning intelligent autism, and seven or more and your brain crashes on boot-up and the autism stops you from functioning.

If so, then the top-level geniuses may well have something else going on upstairs to enhance their intelligence, some other difference from the norms, that isn’t part of the complex of IQ/autism risk genes. Autism-risk genes may just be plumping up the middle tiers, those who are noticeably intelligent but not staggering one-in-a-million test cases.

So one model is that we should see two things happening at once, as a result of the assortative mating by IQ that’s been going on for a couple generations now in the US:

a. Increasingly smart people at the high end, as the smart people tend to meet in college/at work and pair off and have super-smart kids.

b. Increasing numbers of autistic kids at the high end, as some of the smart kids get too many overlapping IQ-enhancing genes that mess up something important.

Any chance it’s just a matter of recessive genes? Like, if you have one copy of a particular high-IQ gene you get high IQ, but two copies of that gene is too much of a good thing and you get autism?

This is a common situation, but not with many genes of small effect.

Seems like it could apply if there were many genes of small but overlapping effect, so that one particular aspect of mental performance is sometimes pushed past the breaking point.

My crank theory is that autism, when looked at through the “environmental toxins are causing Very Serious Problems” lens, starts looking suspiciously like an environmentally induced phenotype

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Genetic_assimilation

A link between Tay-Sach’s gene and intelligence. I remember seeing that article 10 years ago and I’ve never followed up, so replication not guaranteed.

Greg Cochran has a paper that discusses this and other IQ/genetic disease in Jews links here. (PDF link) This was the link from Wikipedia; I’m not sure where else to look for the paper.

It’s also a chapter of The 10,000 Year Explosion.

It was my first thought, too – admittedly followed by the second thought “wait, no, they’ll have thought of that one ages ago”.

I was thinking of Sickle Cell Anemia, where if you get the gene from one parent you are immune to malaria, while if you get from both, your blood can’t carry enough oxygen.

This gene developed in Africa, and can be seen as a fundamental reason for the transatlantic slave trade. Everyone else, enslaved or not, kept dying off working the fields. But African slaves survived.

How much of this could be IQ tests failing to effectively measure g in autistic individuals?

I would expect a challenge, in testing the intelligence of Autistics. It’s not like they’ll answer anybody. They would more easily get high IQ amongst Aspies, whom I don’t consider Autistic.

There was a Conversations With Tyler podcast with Michelle Dawson (link here including transcript) where this was discussed. She pointed out that there are a couple widely-used kinds of IQ test. For one, it’s multiple different kinds of mental tasks whose scores are then combined to get an IQ score. For another (Ravens), it’s a bunch of iterations of the same basic task (a kind of visual puzzle with one piece missing), described here.

Her claim was that autistics often did *way* better on Ravens than on the multiple subtest kind of IQ test. As I understand it (I’m an interested amateur, not an expert, so don’t trust this too far!), in the general population, you will see a very strong correlation between the IQ score someone gets on the two different kind of IQ test, but among autistics, the correlation is much weaker. (And maybe there’s some kind of subtype of autism –> size of correlation thing happening, too.)

There is a (high functioning) autistic musician named Henny Kupferstein who spends a lot of time teaching piano to autistic kids. She has absolute pitch, an attribute that is quite rare in the general population, but she says an amazingly high proportion of her autistic students have it to some degree, even when they didn’t know it. She has an article on her website here: https://hennyk.com/autism-and-perfect-pitch/ and a book: https://hennyk.com/book-perfect-pitch-in-the-key-of-autism/

Some of the stuff she says about this seem a bit woo-woo, but interesting anyway. I don’t know what to make of this:

I see what you did there.

Precision of it? Awareness of it? Moments of it?

There are different levels of the concept we call “perfect pitch”. Some people can correctly identify the pitch of a single note played on the piano. Go up a level and they can tell you the pitch of your hair dryer. Go up a level and you can mash a bunch of sequential notes on a piano with one left out of the middle and they can tell you the highest note, lowest note, and the one you left out. When I was a music major in college it was the research interest of one of my professors and he put the students with perfect pitch through a couple of tests like this in class.

And then there’s Jacob Collier, who can detect, and accurately sing, the difference between an A at 440Hz and at 432Hz, and that allows him to do stuff like this (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mPZn4x3uOac) where he sings a 10-part harmonisation of “In the Bleak Midwinter” in which he’s gradually shifting the key-centre upwards throughout, and then for the last verse he performs a 4-chord pivot to a key halfway between G and G# on the scale he’s in at the time, by taking advantage of slight mis-definition in the equal-tempered approximations to those pivot chords that allows him to quickly shift to an entirely out-of-tune system (if you switched directly, it would just sound like trash) in just four chords without it sounding odd. It’s talked through in detail here (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Xd54l8gfi7M).

Wow! Thank you for introducing me to him. He’s amazing!

I wonder what human spoken language would be like if that kind of ability were universal.

Couldn’t this all be the result of several essentailly different things being lumped together under the label “autism spectrum”? Perhaps the mechanisms for high IQ autism and low IQ autism are different.

To test this, you could see if higher IQ autistic people tend to have more or fewer of these genes correlated with high intelligence, compared to low IQ autistic people. According to the “different mechanism” theory, they should have more, but by the “collapsing tower” theory, they should have fewer.

Well, much debate here gets into the distinction between people with “high functioning autism” and Aspergers, due to a muddling at that end of the scale. Aspergers was definitionally distinguished from autism due to a lack of the cognitive deficits associated with that condition, but in 2013, the DSM-5 folded it into autism spectrum disorders, so this could make it difficult to analyse the genes of high function autistics if that was the mistake I believe it was.

It’s possible some degree of politics was involved in this decision:

I suspect that this is the case. My experience watching a relative currently diagnosed with severe, non-verbal autism grow up is that his diagnosis is a catch-all for “he doesn’t seem capable of abstract thought but we have ruled out all the other, better-understood potential causes.” No one can offer more than conjecture about the cause of his condition, and no one knows how to treat it (unless you listen to the vaccine-chelation charlatans the way that his father does) so why is the medical establishment making confident claims regarding the connection between his condition and “high-functioning autism”?

The reason seems to be that there is great overlap in symptoms, although there is great diversity in symptoms.

Has paternal/maternal age been eliminated as cofounding factor from parents IQ/autism correlation? This seems a possible explanation, if high-IQ parents have children significantly later…

I like the tower explanation, but not so much the different types of intelligences: maybe autism is a combination of rare IQ-boosting alleles inherited from parents, together with high general genetic load (which, among other detrimental effects, decrease IQ, negating the IQ-boosting alleles). the genetic load would be due to bad luck in parent mixing (recessive-recessive pairs) and parent age. Without the load, the child would have had a high IQ, but with weak fundation (genetic load) no. Still, the IQ-boosting alleles produce autism instead of a more “classical” low IQ that genetic load alone would have had…

The ‘note’ in the second image mentions adjusting for maternal and paternal age (among other things), and it doesn’t look like the adjustment makes an important difference.

Yes indeed. paternal IQ/ autism seems pretty much decorrelated, which is strange given the 100% confidence that autism genes are IQ boosting.

Maybe the pattern is something like this (calling “rare” IQ/autism boosting alleles IQb):

IQb + low genetic load : extremely high intelligence, slight or undetectable autistic tendencies, strongly tenchnically inclined

no IQb + low genetic load : high intelligence, sociable, not so technically inclined

IQb – medium genetic load : high intelligence, autistic – highly functional autist or autistic tendencies, strongly tenchnically inclined

no IQb + mgl: normal

IQb + high genetic load: autism with lowish IQ, always diagnosed as autist

no IQb + hgl: very low IQ, non-autistic mental disorders

Is it possible to measure autism on some scale, rather than as a binary category? It would be interesting to see more fine-grained dependency between autism and IQ, i.e. people that are 30% autistic have average IQ X.

Is there precedent for this tower-versus-foundation model being useful for any other health issue, or was it just made up specifically for autism?

If a high quantity of a good thing comes with a risk of problems that reduce the quantity again, then you could understand the ability to keep the problems at bay as „foundation of the tower“. (So I don‘t understand why confidence goes down so much for point 5 in the conclusion of the original post, from 80 to 25 percent.)

Each of us have different stories to share.

I married an autistic woman. She is a university qualified computer systems engineer. One of our children is an Asperger (labelled as high functioning autistic in the DSM). I recognised my son was different at about 15 months old. He taught himself the alphabet before he was 1 year old.

We are both university qualified. Both moderate to high IQ. We had children at around 30. My wife’s father (an engineer) is likely autistic. I have no family history of autism. I am known as a word smith (and it’s an important part of my career, but I’m not in journalism).

My son was measured using the full Weschler and most of his scores were 96-99th percentile (that’s VERY high). His processing was below average. I have always considered him more naturally gifted than me.

Of the autistics I personally know (through common support groups), the Aspergers all have a parent who is an engineer or computer scientist of some sort.

We have another child who shows no autistic traits. He has the making of a superb engineer.

Keep in mind, my sample size is small. However, I wouldn’t be surprised if a statistically high proportion of people here are autistic or have autistic family members.

One other observation that may interest people. We were grouped with autistic including low functioning autistics. If the mums with low functioning autistic children, the ones I spoke to described the fathers as losers or deadbeats. I’m not suggesting this accounts for the high/low intelligence as the sample size was small. I recall it because the lowest functioning children all had loser fathers. The difference between high and low functioning autistic children is significant.

Is it kind of like a bimodal distribution, i.e. most kids will be pretty clearly high or low functioning, with little in between?

What are the percentages of children who fall in each group?

It could be one of the categorization problems Scott was talking about in “Against Against Autism Cures.” If you’re not “low-functioning” but don’t have strong enough autistic traits to be clearly a high-functioning autistic, you don’t have “autism” you’re “just a little weird?” It seems that a process like this could conceptually produce an artificial bimodal distribution, even if the traits aren’t bimodally distributed. My stats-fu isn’t strong enough to know if this actually pencils out, though.

Heck, maybe there are two different underlying conditions here that have similar enough symptoms that we categorize them together (per Scott’s observation in his “The Body Keeps the Score” review that we tend to categorize psychiatric disorders heavily by effect, because the cause is so murky).

Potential confounder: having a low-functioning autistic child is highly stressful and often unpleasant. Being a deadbeat or loser, or being perceived as same, may be a result, not a cause, of the specifically low-functioning types. For example, they may dislike the father for not doing enough when the kid is self-harming from overstimulation. Or the dad may have left or tuned out because he couldn’t handle the situation (but could have handled a socially inept kid who won’t shut up about WWI airplane models). Their career progress might have stalled due to stress and sleep deprivation. Etc.

Many such cases with Aspergers (me too), whereas for high functioning autism the deficit is inverted for processing vs visuo-spatial. The DSM-5 change was a mistake in my view because high functioning autism and AS genuinely seem to be quite different in structure, and it seems as though there were some low level political motivations for folding them together (see upthread). This makes it difficult to analyse high functioning autistics separate from those who would have previously been distinguished as having Aspergers.

EDIT:

Or maybe not, because the researchers just act like they are cognitively distinct “subtypes” anyway, so it might not make much difference in practice.

From this study Scott linked:

Interestingly, this one addresses the P>V, and V>P subtypes and suggests:

Isn’t autism a bit more sensitive to increased parental age than many other mental disorders? If it is, that could explain some of these results.

>They are being positively selected, ie increasing with every generation, presumably because people with the genes are having more children than people without them.

I think this was also true for some genes supposedly predisposing to ADHD and Schizophrenia. (Although, aren’t gene-behavior connections in general pretty suspect, as per your previous post?) https://slatestarcodex.com/2019/05/07/5-httlpr-a-pointed-review/

https://sci-hub.tw/10.1176/appi.ajp.2018.18070881

Can we quantify the causality going the other way?

i.e. do people predisposed to have autistic kids tend to have them later?

I would expect that to be the case based simply on the premises. If smart people are predisposed to have autistic kids (which Scott seems very confident of), another trait of smart people is that they tend to get more education than average. Getting more education is strongly correlated with later childbearing / siring. Based on those two correlations, I would be very surprised if it didn’t add up to a correlation between predisposition for autism and children later in life.

If relatives of autists are smarter, then that sounds to me like a regression towards the mean. Instead of autism causing low IQ, low IQ (in a mental architecture that typically causes high IQ) would cause autism, and then of course when you look at the relatives of a downwards outlier you will find higher IQ.

(When your edit window expires before you submit the edit, it just discards your text and you have to retype it? -.-)

In the graph of relatives, are autists typically on the border or inside of high-IQ regions?

Perhaps different people train their brain using different optimization strategies, and when you optimize too well you risk ending up in the autistic basin of configuration space, which does well in the environment a fetus or baby faces.

How much do we know about how intelligence develops and what might impact it?

Probably wrong ideas generated from your writing here:

We know that core elements of cognition not only do develop early in life, but *have* to develop in life. For example, the experience of people who are blind at birth and then are given sight as an adult vs. those who lost vision as a child and then have their sight restored as an adult. It’s similar with hearing.

Could there be some sort of input(s)/connection(s) in early development which is responsible for the development or unfolding of intelligence like that? If missing, intelligence develops a lot less/later/incompletely?

What led me to ask this is stories of people who were deaf from birth who’d get cochlear implants as adults. Because they lacked the development of the auditory processing, it was very draining for them because it mostly came across as a large amount of noise. This meant that they’d routinely turn them off. Now imagine that someone was in that condition but *couldn’t* turn it off. I could easily see someone unable to focus, stuck in a room banging their head just trying to make the noise go away.

I don’t have time to go through all the links this morning but wanted to add some more studies.

Here’s a study that claims “Few adults with autism have intellectual disability; however, autism is more prevalent in this population. Autism measures may miss more women with autism.”

Another study showing how autistic people have higher prevalence in inpatient psychiatric units.

And an article by John Elder Robison pointing out that most of our data on autistic people come from children and the extreme cases. We don’t have an understanding of how autism exists in the general populace so our data is skewed towards the worst because of where that data comes from.

This is the only study I know that has actually measured autism rates in the general public.

Spoiler alert: ASD in adults was estimated to be 1%

And this is a productive comment because?

… because it is in line with the current prevalence of autism diagnoses in children, but a bit lower. This shows a) there isn’t much of a childhood autism epidemic going on, it’s more likely that previous underdiagnosis occurred. and b) people diagnosed with autism using current criteria are quite prevalent in the community and presumably functioning in their communities.

@alwhite

I didn’t understand why you left out the actual finding, which seems to be an important fact to note.

So I gave that fact to save others the effort to dig for it, while trying to give a subtle hint to you that it is better to include the finding.

What do you guys think of the recent research linking autism to gut bacteria?

Arizone State University – Autism symptoms reduced nearly 50% two years after fecal transplant

The Economist – More evidence that autism is linked to gut bacteria

My outside view intuition is that gut bacteria are the new priming and also literally HTTLPR.

I actually find it rather consistent with the idea that our brain chemistry is tuned to work with a given level of hormones/neurotransmitters produced by our gut bacteria as per Maybe Your Zoloft Stopped Working Because A Liver Fluke Tried To Turn Your Nth-Great-Grandmother Into A Zombie

Say you are a bright nerdy tech-aligned person who is attracted to other bright nerdy tech-aligned people; you have a medium preference for eventually having kids but you really don’t want an autistic child. Is there anything you can do in terms of testing or practice to reduce your risk?

I’m not especially neurologically atypical, but enough that I’m not confident I might not pass down some potentially deleterious genes. This fear is reinforced by the fact that of my 12 cousins, 1 is severely autistic, another one is autistic, but can function, 2 are diagnosed aspie and another 1 is an edge-case. This might sound mean, and I’m very sorry if this offends anyone, but just seeing what my family has gone through, I would definitely find having a severely disabled child worse than not having one and would likely be unhappy with a child any more than slightly aspie. (This sounds harsh, but I want a child at least as normal as I am).

What are the best practices here?

Breed with a Stacy or a Chad. /s

Seriously, what sort of advice do you expect?

Have children earlier, maybe? Increased parental age correlates with autism risk, AIUI. And if you do have a more challenging child, you’ll have more energy to deal with it as a younger parent.

Of the 5 relatives, how many are males?

I would recommend having girls through IVF if that is legally allowed in your jurisdiction?

And also reproducing younger (banking frozen eggs and/or sperm early for the IVF).

Girls also get autism, but seem to stay undiagnosed much more often.

Perhaps this is an obvious point with an obvious answer, but wouldn’t female prevalence of diagnosed autism be expected to be markedly lower? As far as I can tell, the explosion in diagnoses is primarily driven not by the very low-functioning (everyone could already tell that non-verbal folks had something wrong with them) but by increased diagnosis of medium-to-high-functioning people.

Since the definition of autism (as noted by Scott and discussed elsewhere in the comments) is primarily symptomatic, that means you only get the diagnosis if you display symptomatic behaviors meeting a certain noticeable threshold. Most of these seem to be related to social ability. If females have a higher average baseline social competence, it would stand to reason that even the impaired girls would remain above the diagnosis threshold in greater numbers. E.g. Being 1.5 standard deviations less socially adept than the average girl might make you weird, but not problematic, while being 1.5 standard deviations less socially adept than the average boy might make you a classroom / societal problem.

The threshold is probably different for women and men.

3, but the serious cases are all male.

Does affliction rates vary with age of both parents? I don’t know why, but my prior is that the mother’s age matters more.

I don’t know. I have a female acquaintance who was diagnosed with autism. At times she has been productively employed in a technological field. But her personal life is a mess. She’s a real handful to deal with and that deters quality men from being interested in her. And her failure to understand social cues lets her be taken advantage of by lower-quality men, who have sexually abused her on multiple occasions. So is she a “non-serious case”? She’s capable of living without a caretaker, but other than that, the impact on her quality of life seems pretty serious.

No guarantees in biology, but you can try to find a future partner with no such family history. Lots of bright nerdy tech-aligned people don’t.

Guys — autism is not a thing. Like many DSM diagnoses it is a junkheap of often unrelated symptoms wrapped up in a single label for essentially politically reasons. Coming up with elaborate speculations as to why a unitary “autism” would be characterized by wildly divergent and contradictory symptoms (like being very bright and perceptive and being completely non-verbal and unable to learn) just leads you further down the rabbit hole. It would be better to try for more precision/clarification concerning the form of social or linguistic impairment you are concerned about and investigate that. There is no reason to think that e.g. the kind of social impairment characteristic of bright but shy and social awkward people has much if anything to do at a deep level with the impairment experienced by non-verbal children with profound intellectual disabilities, despite the fact that we have built a social system that applies a similar label to both.

But don’t take my word for it, check out the excellent 2016 lit review by Waterhouse et al which concludes:

Link to the entire piece — https://link.springer.com/content/pdf/10.1007/s40489-016-0085-x.pdf

For all his skepticism in some areas, Scott is remarkably accepting of the overall conceptual framework of psychiatric and psychological diagnosis despite its glaring philosophical flaws, which have been pointed out by many (see e.g. the Council for Evidence-Based Psychiatry in the UK on the lack of validity of diagnostic categories in psychiatry — http://cepuk.org/unrecognised-facts/diagnostic-system-lacks-validity/). It is where his bread is buttered professionally, but I wish he would think more deeply about it.

Then why is there a genetic link? If the genetic risk factors for high-functioning and low-functioning autism have a lot of overlap, as Scott suggests, then that strongly implies a connection in etiology.

But I don’t think there is overlap between the genetic factors for high-functioning and low-functioning autism. Low-functioning autism has all kinds of genetic linkages to all kinds of different genetic syndromes that cause brain damage, damage that often extends beyond autistic symptoms. High-functioning autism looks more like the same polygenetic soup one finds with other complex personality characteristics like intelligence or Big Five character traits. Given the numerous different genetic correlates to autism, if one wants to preserve the diagnostic validity of autism by finding a single etiology, one might hypothesize that all of these genes affect a narrow set of brain circuitry in a similar way, but as discussed in the Waterhouse paper people have tried to do this and (per her lit review) failed to do so.

With that said, I’m not an expert and there is a vast literature rummaging around for genetic correlates to autism, so I’m mostly going by the linked paper above. But in general there will always be a hereditary component to personality characteristics that is probably linked to genes and one will be able to find correlations, but that is a long long way from understanding etiology or validating a single diagnostic label for a broad phenotype.

The “Tower vs Foundation” model seems to treat intelligence as if it’s an attribute like height or arm length; the modification of some static variable. But by “intelligence” mean the ability of a complex system (a brain) to operate effectively; so “being smart” is much more similar to “being able to run really fast” or “having a good immune system.”

So by comparison, I could imagine that there’s a bunch of gene variants that increase limb length, and that if you have a certain number of these you get some nice Usain Bolt proportions that help you win races. If you have too many, your legs are bizarrely long twigs that you totter around on like a newborn giraffe, and you’ve just gone to far so you won’t be a great runner. The physical kinematics of the human body dictate some ideal limb proportions for the 500-meter dash (say), and that’s a target your genetic makeup can miss in either direction.

The entire idea of a gene “for intelligence” is just as silly as a gene for “running fast.” There are genes which have lower-order effects, and intelligence or running are higher-order capabilities that emerge from the lower-order system in complex ways (indeed, there’s probably several more layers than that.) There’s obviously no reason genetic factors would aggregate in a nice linear fashion in that kind of situation. (And, just to acknowledge what I suspect was the subtext of this entire post, that’s really bad news for people who want to get significant IQ gains from genetic engineering.)

Thumbs up to this perspective. Comparing intelligence to running fast understates the issue, it is much more like a complex rules-based game such as football, baseball, etc. for which certain genetic inputs might be extremely valuable but there are numerous different ways to arrive at the end point of being good at the game, and numerous different ways that even people genetically gifted in some important capacity can end up being bad at playing the overall game.

Yeah, your reaction is what I was scrolling down here to say, but you beat me to it. 🙂 Your model of “too much of a good thing” seems to, to my non-doctor, non-expert mind, fit perfectly.

You mentioned “height”, which I think is a good example too – we have studies (possibly not good ones) showing that taller people have better outcomes, get treated nicer, are more attractive – but people who get too tall have bad medical problems, shorter life expectancy.

Even if intelligence is analogous to “running fast” or “having a good immune system,” the tower/foundation model is still workable.

If you keep stacking up genes that in isolation would improve your running speed, but that involve trade-offs or may have adverse interactions with each other by both modifying the same chemical pathway or something… Eventually you have too many and things collapse. Each gene’s benefit is based on underlying assumptions about how the body works, and if you change enough of those assumptions, the entire edifice becomes a failure.

To some extent, incompatible advantages can ‘stack’ by affecting entirely different things (one runner with salutary mutations affecting his legs, his lungs, and his adrenal gland)… But to some extent they can’t.

Intelligence may be very much the same way.

Yes, I was thinking something very similar: Broadly speaking, it’s pretty clear that intelligence differeces come from differences in brain structure or organization, macroscopic and/or microscopic. The genes that control the development of that definitely don’t do so in a linear or easily explainable way. For example, why do people with down syndrome or williams syndrome have differently shaped faces? On the first level it’s obviously ‘because of the genetic abnormalities they have’, but it’s not like we could look at those gene differences and predict that those features would develop in that way. Or in the case of plants, their leaf structures are generated by a fractal pattern, and even small changes in the parameters of that fractal cause large changes in the ultimate pattern in a way that is chaotic and difficult to predict. And intelligence, being a function of the brain itself rather than directly of the genes that generate it, would in this analogy depend more directly on something more like the shape of the plant’s leaves than the internal fractal parameters that generate it.

So it may not just be something like ‘too much of a good thing’ but ‘the relationship between the seed parameters (genes) and the result (brain architecture/intelligence) is something that’s chaotic rather than simple.

My relatively uninformed opinion would be: what the mutations might be affecting in lower-order terms are some subtle parameters of prior mapping, or something like a lower threshold for what’s considered to be sufficient fit for model validity, or what kinds of sensory inputs to give particular significance to. Given that many drugs both medical and recreational appear to affect similarly subtle parameters broadly through relatively simple molecules, there’s no reason to assume they can’t be much more specifically fine-tuned through genetics.

Maybe specific areas for different such quirks of processing have some optimal Goldilocks zones for their values, which if all fit might give you some sort of the upper bounds of human intelligence-maybe there are multiple such optimal/viable configurations, however hitting all the targets simultaneously must be relatively rare, and some of the targets might be smallish, others might be essentially fixed without some de novo mutation for likely good evolutionary reasons.

It wouldn’t surprise me if what’s perceived in higher order terms as stereotypically autistic might be a series of misses on such optimal targets, over- or under- shoots, and then you end up in a situation where a child has difficulty working out how to discard pareidolia from their mental model of the world say just because of a specific kind of synapse oversensitive in some particular way, or later they engage in repetitive behavior instead of altering their mental model to accommodate more unpredictable interactions because it appears more efficient to their brain to conserve the model because of the overstated unpredictability of the alternatives, et cetera.

Some might get lucky and be able to manage the negatives from such unusual prior models away by the effects of other quirks, say having abstract thoughts feel more natural through some particular tweaks making the net their active inference casts ‘wider’ with higher error tolerance or by lowering the interconnectivity between different oversensitive mental modules that they don’t interfere with one another as much or whatnot – then you get high-functioning autistic individuals, maybe Newton’s one cliched example of that sort of configuration.

The Tower vs Foundation model is probably an oversimplification of something like this.

My personal bet would be that different sorts of mutations associated with autism could be slotted into abstract prior-mapping-affecting categories manifesting through tiny quirks of cellular chemistry, and some degree of interplay between them and those that affect general nervous tissue metabolism and anatomy might also be the case.

And the ‘extreme male brain’ hypothesis in that light might just be an artifact of a statistical consequence of GMV in that set of traits, as it could be less reproductively costly to have a less stable architecture for those types of parameters in males due to higher reproductive payoff of hitting one of those ‘optimal configurations’ in terms of number of offspring, as well as lower individual investment.

This post is missing a discussion of the changing meaning of “autism”. Now that Asperger’s syndrome has been removed from the DSM, in favour of something understood by lay people as “autism”, I’ve become autistic, along with a fair number of other geeks, nerds, etc. (*)

It’s not hard to measure my IQ, except that it generally falls at the top of the scale where the tests don’t make effective distinctions. (Or did, 20+ years ago when I last took an IQ test.) On that and other evidence, it’s pretty clear the above article isn’t talking about autistics like me. But it’s frankly unclear who it is talking about. Non-verbal people requiring institutionalization? (I.e. the classic stereotype.)

(*) to complicate matters, in normal usage, I’m “autistic”, but in many usages I wouldn’t be described as “having autism”. Some vaguely similar term like “high functioning autism” would be used. (Note that if autism is really one thing [not a complex syndrome], with high and normal functioning individuals, and high vs normal correlates with IQ, then if you only measure the “normal” autistics, you’d get results like the above, due to sampling bias. No need for (extremely valid) concerns about whether IQ tests accurately measure (normal/low) functioning autistics, e.g. the non-verbal.

One other effect of this change in labelling, is that studies of “autistics” before and after the renaming can’t be combined into any kind of meta-study, unless they are both much more detailed in their description of the grouyp they are measuring, and happen to target the same people.

This would be a more useful post if it addressed this change in terminology.

The Waterhouse study I linked above (https://link.springer.com/content/pdf/10.1007/s40489-016-0085-x.pdf) argues that even before the autism-aspergers lumping made things worse, ASD samples within single studies (let alone meta-analyses) were not useful for scientific inference because the “autism” diagnosis lumps together so many wildly disparate developmental and social issues. As the authors put it:

I spent a lot of time reading about giftedness (having a IQ > 130) in the last few months, specifically educating gifted kids and teenagers, and I found out quite some things about how giftedness can interact with social ability:

It turns out that giftedness can be quite a burden for children and teenagers, as not many of their peers can relate to them and vice versa. This can lead to bullying and social isolation, which in the long term can cause depression and the failure to learn social customs. There is another problem: Giftedness also increases empathy, which in the wrong environment can be a bad thing. Think about it this way: When most other people behave incomprehensible for you because they don’t see the same emotional nuances and act on their impulses, it is hard to learn social customs, even though you theoretically have the potential to be very skilled socially.

There is yet more. Giftedness makes people more idiosyncratic. It’s hard to pin down why this is the case, but I think it is related to the things above, but also to the fact that gifted people tend to be bad at copying other people instinctively. I think this is connected to gifted people tend to be good at finding creative solutions to things rather than the most obvious ones, which in the case of weird walking or talking styles can look like autistic behavior.

Reading about this seems a little bit strange at first, but I must say, I teach in the mathematics department of a university, and I observe this everyday in my best students. Every year, we get like 4 or 5 students who are just ready for hardcore abstract mathematics from the get go, and since a few years my university allows them to take masters level lectures as early as they want. I would say that 80% of them carry a fair amount of weirdness with them, which shows in speech impediments, idiosyncratic/shitty clothing styles and obsessions with bizarre topics.

This could be constructed as autistic behavior, but I don’t buy it. The reason is that interacting with those students always feels the same, it doesn’t matter how weird they seem at first. They all share the same hunger for mathematics, and if you get to know those who seem “normal” on the surface, you find out that they have some interesting hobbies as well. The latter are the Feynman types: Goofballs with a myriad of weird interests (Feynman was into playing the Bongo drums and the short lifed Soviet Republic Tannu Tuva, among other things).

All this leads me to believe that people who are gifted and who’s weirdness is more obvious are often misdiagnosed as having Asperger autism. Or rather, that the concept of Asperger autism is more related to giftedness, and not to autism. I’m very open to people arguing the contrary, but I must say, in 8 years of doing abstract mathematics, I never met an Asperger-like person where giftedness did not seem to be part of the equation.

There are so many ways to be weird and out of touch with the people around you, related to very different sets of issues and characteristics.

Observing matters in my local school, I think that child psychiatry is best understood as a means of managing problems that arise in children’s socialization to the school environment, and clusters of diagnoses align with a big three of socialization difficulties:

“weird don’t fit in” kids are diagnosed as autistic

“restless can’t sit still or stop acting up” kids are diagnosed as ADD

“violent/fighting/tantrum” kids are diagnosed with oppositional disorders

There are huge practical and financial incentives within our system to diagnose all of these sets of kids with some kind of medicalized disorder, regardless of whether any underlying physical mechanism is understood or present (and sometimes it is, but many different developmental issues can lead you down each of these roads).

As a practical matter of course these disorder clusters can easily overlap and often do, as seen in the most recent DSM when they allowed co-diagnosis of autism and ADHD for the first time (by popular demand pretty much!). But they offer a way of grouping “types” of problem kids that has caught on. At the individual level things are generally way more complex than these symptom-based diagnoses and the key is to ask *why* the kid isn’t mixing well socially, gets into fights / lashes out, or can’t sit still rather than reify it as a brain dysfunction.

I find it absolutely bizarre that the intelligence of kids who don’t fit in is often ignored. It is known that gifted kids can be misdiagnosed as autism, ADHD or both, but many psychologist never bother doing IQ tests, or do them, but then ignore the results.

Slightly differently: Being gifted makes it harder to take certain things seriously. What is the point of arbitrary social rituals?

Well, there is a point, but it takes a long time to grasp it, at which point you are significantly behind people who went along with them without questioning them. More, you have probably already settled into an existence that minimizes their importance to you by the time you have enough information to piece together the importance of predictability.

More, by that point your identity probably includes significant aspects which make the idea of becoming normal and predictable less personally palatable.