NYT: Economic Incentives Don’t Always Do What We Want Them To (h/t MR). For the first time in history, the title actually understates the article, which argues that incentives can be surprisingly useless:

Economists have somehow managed to hide in plain sight an enormously consequential finding from their research: Financial incentives are nowhere near as powerful as they are usually assumed to be.

The article starts with some surprising facts. Increased taxes on the rich don’t make rich people work much less. Salary caps on athletes don’t decrease athletic performance. Increased welfare doesn’t make poor people work less. Decreased job opportunities in one area rarely cause people to move elsewhere.

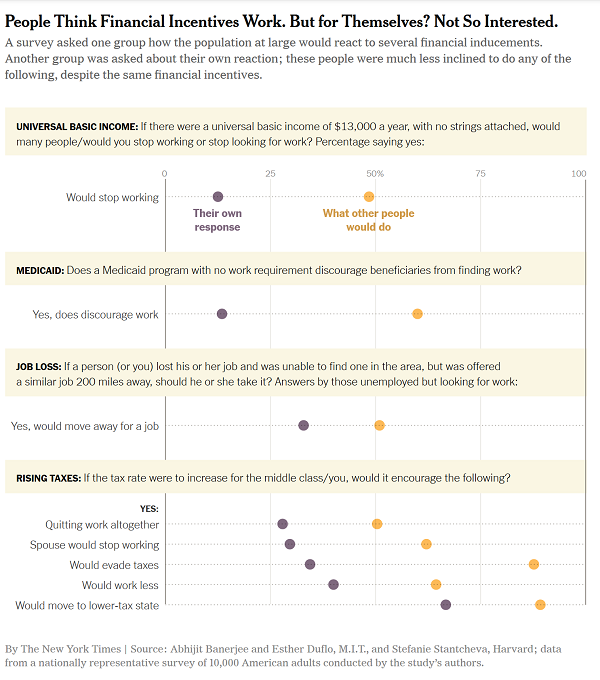

Then it presents a neat chart showing that most people believe others would respond to an incentive, but deny responding to that incentive themselves. For example, 60% of people say a Medicaid program with no work requirement would prevent many people from seeking work, but only 10% of people say they themselves would stop seeking work with such a program.

…but keep in mind an alternate interpretation would be “desirability bias makes people deny they would work less and evade taxes”

All this suggests that:

If it is not financial incentives, what else might people care about? The answer is something we know in our guts: status, dignity, social connections. Chief executives and top athletes are driven by the desire to win and be the best. The poor will walk away from social benefits if they come with being treated like a criminal. And among the middle class, the fear of losing their sense of who they are and their status in the local community can be an extraordinarily paralyzing force.

They conclude that this argues in favor of policies like raising taxes on the rich and removing all requirements from welfare programs.

The authors are Nobel Prize winning economists, so I assume they’re basically right. And I’m not up to doing a complicated literature review to compare all the cases where economic incentives do work to the cases where they don’t and develop a well-informed understanding of the subtleties in their position. So instead, a few low-effort thoughts.

First, it matters less whether the average person responds to economic incentives, and more whether the marginal person will. If I need someone to cover the graveyard shift at work, nobody will do it for normal pay, and I offer double pay, all I need is for one employee to be incentive-sensitive enough to take me up on it. Maybe most people wouldn’t accept any amount of money to become an oil rig worker, a McKinsey consultant, or a camgirl, but ExxonMobil/McKinsey/MyFreeCams.com only need just enough qualified people to accept whatever deal they’re offering.

Likewise, perhaps if I had no alarm system protecting my house, 99.999% of people still wouldn’t rob me. But 99.999% of people not robbing you is still known as “getting robbed”.

So “most people don’t respond to most economic incentives” is totally compatible with “economic incentives rule the world and control everything around us.”

Second, grant that most people care primarily about “status, dignity, [and] social connections”. A lot of how that works out in real life is “doing the socially acceptable thing”. Even if incentives are weak in the short term, they can be very strong in the long term after they have time to act on what is or isn’t socially acceptable.

It’s all nice and good to say “most people wouldn’t steal even in the absence of punishment”. But what about music piracy? Nobody had any way to enforce rules against pirating music. Maybe only a few people pirated at first. But then more and more people did it, and eventually the unwritten rule among teenagers became that music piracy was okay – in fact, that you were weird if you didn’t do it. On the other hand, stealing a CD from a record store still feels horrifying and criminal and inconceivable. Although there are subtle differences between the two cases (it costs nonzero money to make a physical CD) I still think a lot of this is social norms that formed downstream of enforcement-related incentives.

Or: most people would never cheat on welfare. But there are Alabama counties where over 25% of the population are on disability, an increase of 50% from just fifteen years earlier. I don’t want to accuse any of them of cheating, per se, and see here for a more in-depth analysis. But I think it’s easy to normalize taking disability for lesser and lesser afflictions, and that part of the normalization process involves an economic incentive to do it and a lack of incentive not to.

Or: in Sierra Leone, 84% of people say they have paid bribes; in Japan, 1% have. So do “people” care about financial incentives or not? Grant that “status, dignity, [and] social connections” are more important, and that this is what prevents bribery in Japan. But once these factors permit bribery, it becomes rampant. And are these factors themselves maintained partly by incentives, eg punishments upon being caught? I’m not sure.

Third, remember that principles are usually downstream of politics. So one fun game is to take a principle usually used on one side of the political spectrum, then apply it in support of the opposite side and see if you still hold it.

So. We know there’s no reason not to raise taxes, since rich people don’t respond to financial incentives. But there’s also no reason to close tax loopholes – rich people defrauding the government of money through tax evasion is surely as unthinkable as poor people defrauding the government through welfare scams. And there’s no reason to question the bonuses of Wall Street traders, since it’s not like anything as crass as a financial incentive would cause them to make risky trades.

Did pharmaceutical companies incentivize opioid overuse through paying doctors to overprescribe? Doesn’t matter, doctors would never let financial incentives affect their prescribing decisions. Are senators cozying up to companies that will give them lucrative sinecures later in a “revolving-door” system of legal bribery? No, because incentives aren’t powerful enough to make senators abandon their dignity. Are billionaires destroying the environment just to make a buck? No, the financial incentives to do so wouldn’t outweigh the cost in status and social connections.

None of this snark disproves the real empirical research the authors use to show that rich people’s taxes, poor people’s welfare use, and economic mobility are not very incentive-sensitive. But I hope they prevent people from generalizing to a general sense that financial incentives don’t matter, or turning this into a purely partisan issue where anyone who believes in financial incentives at all gets accused of “dog whistling” conservativism.

Fourth, and most important, the more we’re ruled by social incentives, the more importance financial incentives take on as a counterweight. Quoting my favorite part of the article again:

If it is not financial incentives, what else might people care about? The answer is something we know in our guts: status, dignity, social connections. Chief executives and top athletes are driven by the desire to win and be the best. The poor will walk away from social benefits if they come with being treated like a criminal. And among the middle class, the fear of losing their sense of who they are and their status in the local community can be an extraordinarily paralyzing force.

I think this is profoundly true, so true that it’s almost impossible to appreciate enough. The article frames it positively – we care about community more than money, how heartwarming. But I find it disquieting – it could equally be framed “We care more about fitting in and not seeming weird than about anything else in the world”. 99% of world-changing ideas are stillborn when their would-be-inventor worries they might sound weird for proposing them. 99% of great companies don’t get off the ground because their would-be-founder worries about what other people would think. The most important ideas for changing government and society sit on the lunatic fringe, because everyone worries that supporting such ideas might keep them out of the Inner Ring.

Paradoxically, I think this argues in favor of financial incentives. The beauty of financial incentives is that they provide a counterbalance to status incentives. The counterbalance is weak, inconsistent, blink-and-you-miss-it, but it is real. If all the cool people say “we do it this way”, 99% of people will do it that way to fit in, but there will be one person who does it the much better way that lets them outcompete everyone else and make $10 billion. And having $10 billion brings “status, dignity, [and] social connections” of its own. Even if only a tiny number of people are sensitive to money, it’s enough to create a core who occasionally try making things better even when that’s not cool.

One corollary of this is that when you remove financial incentives, you don’t get everyone acting ethically for the good of all. You just get status incentives with no counterbalance. I can think of few things scarier.

I think you forgot about the biggest point here. This is a self report study. Those are notoriously inaccurate. I don’t trust people to accurately tell me what they would do. I find it very plausible that people underestimate the extent to which they respond to incentives in order to fuel their delusions that they are less lazy/greedy/self-interested than they really are.

Isn’t that kind of a fully general counterargument?

Like…

Walter: “All people are stinky.”

Scott: “I surveyed them and they aren’t.”

Walter: “Of course they’d say that…”

I mean, if you don’t believe people when they say stuff that is laudable aren’t u in wild west country? Nobody can refute anything (of course you WOULD say you aren’t guilty of so and so, the motive is obvious!), so everyone has to accuse first?

A better description of your hypothetical re: what Scott is saying is:

The question isn’t what people say they’ll do, it’s what they actually do when they have to live with the consequences. In your hypothetical, if you conclude they aren’t stinky by actually smelling them, not asking them.

No, it’s a widely applicable heuristic for weakening of purported evidence.

Also worth pointing out that in economics, there is a general skepticism for believing survey style evidence. People might *say* they will do anything. There are relatively weak incentives to tell the truth, and often can be substantially social desirability motives for giving an untruthful answer. “Do what I do, not what I say” and so forth. In fact, I recall there is evidence that people’s predictions of other people’s behavior is more accurate than their claims about their own behavior, when looking in contexts where these social considerations are at play (for example, people don’t like admitting that they will procrastinate, but quite accurately predict that other people will procrastinate).

This phenomenon is so pervasive, economics has jargon for it: “revealed preference”. As opposed to stated preference.

No. Not all studies are self reports. We could look at places where policies were actually implemented and see how people’s actions changed

It’s not a fully general counterargument, it’s pointing out that the value of self-reporting evidence is low, and larger or more self-reporting studies aren’t completely independent sources of evidence.

@Walter

I think that there is a difference between studies that ask about what people are or did, versus studies that ask them what they would do. The latter are probably much less truthful, because people don’t get anywhere near the same level of cognitive dissonance that they get from misrepresenting the past.

Also, predicting the future allows people to assume circumstances that flatter themselves, while people could not choose the circumstances to such an extent when talking about current or past reality.

Or to give an example:

If I tell you that I’ve never cut someone off in traffic, it feels like a lie if I remember doing it once, for example when I failed to look in my mirrors. Yet if I tell you that I don’t expect to cut people off in the future, I’ll probably think about intentionally cutting off people, which I won’t do.

Sort of. It’s a fully general counterargument against putting too much weight on survey data, which is totally appropriate. If survey data is all the evidence you have for your claim, you don’t have high-quality evidence for your claim.

The bigger issue here is that the survey data they cite simply don’t support the narrative they’re pushing. If a double-digit percentage of people say that they would stop working if they got a basic income, that’s a pretty big deal, and it’s a rather bizarre choice to present it as a refutation of the 50% of respondents who said that a basic income would cause many people to stop working.

It’s not at all clear why they think that those numbers should match. If you polled a bunch of Americans and asked half of them, “Do many Americans speak Spanish?” and asked the other half, “Do you speak Spanish?” and the numbers don’t match, that’s not much of a gotcha moment.

Well put. And further, it depends on the severity of the behavior/event whether it qualifies as ‘many’. As far as social and economic impacts, 12% of the population no longer seeking employment is quite a lot.

True. On the other hand, it’s also a pretty far cry from 50% of the population no longer seeking employment.

If the study is correct, most people reading the study will intuitively estimate the number of people who would quit and live on UBI as 50%. That is, they’d be overestimating by a factor of approximately four.

If you want to know whether people think that 51+% of people will do something, there is a way to ask that, using the word ‘majority.’

Esther Duflo and Abhijit Banerjee are both migrants to the US, coming from countries where English is not the native language, so perhaps their language skills are to blame. Or perhaps they are just careless. Or biased.

If people, purposefully or not, misconstrue “many” into “most” then we have lost the very useful word “many.”

Somewhat related data point. Some years ago I had a pick-up/red pill phase and read everything I could get my hands on, including a bunch of relevant studies (a bit over half a meter high printed, if I remember well). THE defining moment in reading those papers was when I started filtering them based on self reporting. Turns out I could have saved myself quite a bit of time – by far most of them were… I’m not going to say irrelevant, but let’s just say there were different attractors for studies that had a high degree of self reporting and those that didn’t. Once you started paying attention to this it was pretty obvious. (In case anybody is wondering, the second kind strongly suggests women prefer men that are tall, buff and dominant. Now I wonder how prestige plays into this – I’m tempted to guess it’s more likely it wasn’t studied enough, rather than it’s not relevant. But at the time I wasn’t aware of the difference).

For some reason, the article emphasizes a self-report study, but it cites a bunch of much more robust evidence. I presume the self-report study was emphasized because they wanted to highlight the contrast between what people say they expect others would do and what they say they would do themselves (though I’m not sure why they want to emphasize that), but the other evidence they provide much more briefly is obviously more relevant to the question of the effectiveness of financial incentives.

It’s actually really frustrating that the self-report study is what’s being focused on, not the other studies of how people have observably responded to financial incentives. The survey is the new thing these authors have produced, so it’s natural for them to focus on it, but I’d hope folks here would be willing to at least engage with the other studies (I think they linked like 5 in the article?).

FFS, the survey is something they did because of other studies. It was done to explore an observed phenomena in the economics literature of people not responding to financial incentives in the ways a classical treatment would expect!

Scott’s points 1 and 2 above are well-taken. Financial incentives can shape social incentives, and its arguably marginal individuals who matter for that process.

Regarding the other studies, I think that it’s important to note that they mainly focus on the effects of UBI-like policies on labor supply. This is a fairly weak incentive–people aren’t getting paid to not work, they’re receiving unconditional money that at best will slightly lessen the incentive to work (since marginal dollars from working are worth less when you have a basic income). As has been mentioned below, the studies in which the transfers were explicitly temporary are particularly bad: It seems completely financially rational not to quit your job and live off the basic income for three years when you’ll need to have a job to support yourself after the end of the study.

In short, I don’t think these UBI studies show much about people’s general tendency to respond to financial incentives.

I will say though, it is a good way to undermine objections to the welfare work requirement/UBI that I use extensively. I wait until someone conversationally drops “well, without a subsistence level financial incentive, why would anyone even work?” and then I find ways to steer the conversation towards personal incentives and point out how they don’t really align.

There is a strong social incentive to say on a survey that you yourself would not change your behavior for the marginal dollar; it’s quite low-status, undignified, and antisocial to say that you would. And there is no financial incentive to say that you don’t care what others think of you. As for actual behavior…

Are people reliably better at predicting what the average person would do than what they themselves would do?

Very likely. People are MUCH better at predicting test score the median person will receive than predicting what percentile they will rank.

I don’t think that analogy quite works. Test scores are a question of aptitude, not values.

(Which is not to say that people are perfect at predicting how their values will be applied in real-world situations.)

This.

Also as we can see in self report studies about calorie consumption, people tend to missreport their own behavior even when known to be monitored, so we can expect that

our body lies to ussomething makes our memories form in a way that our behavior looks more socialy acceptable.It’s also something we strongly like to tell ourselves, even if we would change our behavior for money.

And when we do, we’re very good at coming up with stories to tell ourselves about how we really made that choice for reason X, and it’s mere coincidence that it happened to be the most financially good.

For more o this, read The Elephant In The Brain.

Unemployed people moving for a job: 30% / 50%

Employed people moving to another state because of taxes: 70% / 85%

I can’t square the two of those. They should be in the opposite order.

I think people are seeing these surveys as political opinion polls. “Do not raise my taxes. I will move!! Or, if not me, then someone else, surely!!!”

Because they were asked in 2018 when the UE rate was under 4%. Who was unemployed during that period? Is this cross section similar at all to those unemployed in 2010?

This seems absurdly high, and pretty clearly false based on the fact that populations of states with the highest taxes haven’t been entirely decimated.

Possibly people are mixing in “could” here. Unemployed people don’t necessarily have the means to move for a job.

I suppose that depends on how much they think of as “high taxes”. Perhaps they’re thinking “well, current Illinois taxes are fine for me, but if they went up from here, I’d have to move”.

Everyone has different price tolerances for such things.

It’s a trickle – you can see its impact in housing markets for properties around the 750k to 1.25MM range in NE, Chicago, and other liberal bastions.

Also, what people report, particularly when being watched, differs from what they actually do, so I’m always skeptical of studies based on self-reporting.

Maybe we can come up with a system where people are led to believe there’s an entity perpetually watching them and evaluating their actions.

The ultimate panopticon lies not in the perception of always being watched, but by taking part in watching oneself and others on society’s behalf.

Exactly.

Revealed Preference > Survey Results in terms of reliability.

If Billionaires say they don’t care about wealth taxes, but most flee the country when they’re passed, those are both evidence, but one of them is a lot stronger evidence than the other.

There’s a whole bunch of comments here which seem to think that this entire research program is based on that one survey they mention. It’s a cute survey, but it’s mostly illustrative.

The evidence that taxes don’t effect behaviour much *is* largely based on revealed preferences. Generally speaking, the early optimal tax literature greatly overestimated people’s sensitivity to changes in tax levels. Fortunately people just keep on trucking regardless- a workaholic surgeon is a workaholic surgeon, even at half the price. Whether specifically billionaires will move in response to wealth taxes is a interesting question though, it’s conceivable that they are unusually responsive to this sort of thing.

I will be the first to admit that I only go as far as what is linked and not canvas their larger corpus of work.

But I also think that’s fair – if they write an op-ed, and I realize that op-ed via Scott, then I’m going to focus on what Scott says and the contents of the op-ed, particularly if I’m already biased, and I am.

For my part, I’m moving out of NYC ASAP, but if you were to ask me similar questions, I’d say no *for now* because my wife is in residency. Of course there’s going to be stickiness in the present, but if you alter certain parameters, the status quo and norms will reset. First at the margins, then to the point where I will become the “other people”

Reverse argument: I’m in software engineering and have considered medical school. Doing the math last time I did it involved a 12-year break-even perspective. That is, I’d be worse off for 12 years if anything happened. If pay for physicians increased it would be less risky for me to do so and I’d be more likely to do so.

Ursus Arctos’s last sentence seems to be the likely case. As per Scott’s number one, those are the margins are far more sensitive to financial incentives, and almost by definition, the 1% are on the margin, and arguably get into/don’t drop out of the 1% because of that sensitivity.

Though we have seen more than a few cases recently where financial incentive sensitivity has been cranked so high that they go full Goodhart’s Law, with Wells Fargo and Boeing. But those may also prove the rule, too, as the billionaires involved tend to make out like bandits, analogy intended, even as their corporations suffer all of the consequences. Those cases, indeed, may precisely occur because they, the individuals on the margin, exploit how the collective is less sensitive to money flows, and so the collective goes along with their schemes as inertia sloshes large amounts of cash around.

I don’t know what “billionaires” are involved in Wells Fargo or Boeing — highly paid execs yes.

It always struck me as amazing that when something goes wrong it’s always because of the “greed” of so and so that caused it, but when you have that same “greed” producing trillions of miles of safe air travel and arguably the best airliners in the world (doesn’t have to be only Boeing) it just sort of gets ignored.

I agree that they went full Goodhart, though. That seems to be a disease of ossified companies and these two look pretty ossified.

Friends of my parents moved from California to Nevada when they wanted to retire and liquidate their $x*10^7 property investments. He explicitly said “Uncle Sam is getting his 30%, but I don’t need to pay another 10% to California.”

They never moved back to California.

I actually just thought the authors formed completely wrong conclusions from the data they presented.

I’m no economist, but if 12% of the workforce left their jobs, wouldn’t that be a very big deal?

Huge deal. And given the likely distribution of such job losses (concentrated in low wage service jobs), I’d expect there to be a spike in wages and costs in those businesses.

I’d expect that the spike in costs would be to add additional automation that results in a further drop in total wages paid.

Particularly since the social incentives for the business would move away from ‘don’t install machines that take people’s jobs’.

I don’t feel like trawling for a source right now, but one of the take-aways from Nixon’s basic-income experiments in the 60s was that most people who received it didn’t quit their jobs altogether, although many dropped their second jobs, with the surprising result that overall, the ditched jobs simply resorbed a lot of unemployment.

$13k/y is a huge deal, but all signs point to people wanting more than that, for comfort, status and a bunch of other reasons.

Of course, we would need empirical evidence that this is still how it would work nowadays. In fact, this is a very important point – that we need more trials of this, rather than heartfelt conviction that freely giving money to people will tank the economy somehow.

In very NIMBY cities in blue states, landlords would capture somewhere around 110% of the surplus from UBI.

And that’s a very good problem to look into! Landlords are very good at capturing surplus, UBI or no, NIMBY blue towns or otherwise. How would that weigh in comparison to the societal ills UBI (or a lesser version of it) would alleviate? It might create new problems, sure, but I don’t think there are solutions that don’t.

If so, those landlords could and should implement UBI within those areas and increase their wealth by 10% per UBI payment cycle.

Wouldn’t work like that. Remember, landlords are long term investors. A UBI in an area without strong border controls, both in and out, serves as a nuisance for anyone trying to run a financially profitable institution. It is expensive which drives out corporations and high income/wealth individuals (who would otherwise pay the taxes), and attracts low skill, low capital, entrants. The end result looks a lot more like Detroit in 1990 than 2019 Nashville for landlords.

Although, presumably, concentrating job losses in low-wage jobs is better than the alternative.

I’d go so far as to say losing low-wage jobs in many cases isn’t bad at all. The important parts of the economy have to do with research and innovation. The world gets better because technology improves, not because consumer goods become more plentiful. Arguably, consumer goods in overabundance make the world worse. Whether because they are sources of super stimuli or they have externalities that go unaccounted for, many consumer goods do harm to people. Low-wage people are less important to research and innovation than they are to the production of consumer goods, so if they were reduced in the economy by ten percent I think that would be a good thing for society at large, to speak nothing of their own gains in happiness.

I don’t know what the argument is for why we need lots of restaurants, cars, and video games, other than that people are pointlessly addicted to them.

Can we not decide other people’s lives aren’t really useful?

There’s no need to frame it quite like that. What if a lot of people’s lives are currently being funnelled in directions that are indeed not useful for society or humanity at large? What if they would be spend more conducively to human flourishing in more… domestic activities? Or what if, indeed, it doesn’t matter how they are spent? I don’t think we want the space of possible social arrangements under consideration to be arbitrarily restricted by the need to keep up polite pretences. If you have a good consequentialist argument for keeping up that pretence, that’s another matter, but you seem to be proclaiming the need to do so as an article of faith.

I’m saying this as someone who, as these things go, is definitely not among the most useful sections of humanity.

What reason is there to believe that?

What reason is there to believe that?

Because they are inconvenient to our Five-Year Plan.

Why do we need art or birth control or delicious food? Are people pointlessly addicted to expression, sex outside procreation and tasty things?

@berk

Let’s say that if North Americans reverted to 1950s levels of consumption or reconstructed their society so it looked more like Western Europe then I would not have as many criticisms to make of it with regards to its consumerism. The fact that its consumerism is gained by coercing people to work jobs they don’t like and may in fact hate, or by forcing people who are unable to work to become homeless, makes me despise it all the more.

Why 1950? Who decides?

Coercion involves force or threats (such as the threat of imprisonment for breaking a law). Where do you see coercion in low wage jobs?

If you are concerned about coercion then closer to Western Europe is the wrong direction.

@berk

I went with the 1950s largely out of caprice. I once read about how Clark Ashton Smith lived prior to and during that decade (or perhaps only prior to it), and it involved a somewhat dilapidated cabin with no electricity or running water, but a well he drew water from (and it was an old mine, at that) and annual controlled burnings of the surrounding vegetation to eradicate any deleterious plants, such as burrs. He furthermore dedicated himself to literary aspirations as well as artworks and minor projects such as constructing a hedge wall out of local rocks. This to me does not seem like a bad way to live, and the idea that all of the material progress we have made that supersedes and precludes that kind of lifestyle is both good and desirable is an absurdity to me.

Coercion is involved in forcing people to work because if they do not do it they will become homeless and suffer various abuses and privations. This is an implicit threat. The people who would drop out of the labor force if granted 13k per year are likely people who are only in it to begin with because of this coercive factor, so wanting to keep these people working by denying them succor is akin to wanting to coerce them to work.

The problem of lots of low-wage workers deciding to stop working isn’t economic. Employers will invest more in automation, there will be more mid-wage jobs making the machines that did low-wage jobs, etc.

It’s psychological. Low-wage workers are either just starting out, and have a clear path to higher-wage work, or they’re long-term low-wage workers. The long-term low-wage workers are not generally the sort of people who will use their free time doing things that look like work but don’t pay; they’re likely to use that time as leisure time. And that’s psychologically bad for people.

Women, much more so than men, can find fulfillment in child-raising, but even among the men who would be happy to raise kids full-time while on UBI, the likelihood of them living full-time with their kids isn’t very high, so effectively, that option isn’t available to long-term low-wage men.

But having large numbers of not-well-educated men with nothing fulfilling in their lives is really not a good social policy.

Anthony,

You are simply poorly informed. Those UBI “retirees” are going to learn to play a musical instrument, go to the opera, the theatre, and read Kant, Stendhal, and Proust. Sheesh!

Exactly. Their own data contradicts their conclusions. How nice of them to show it to us so we can know right away they’re full of shit without having to look up studies!

Unfortunately, no.

Ironically, they may be right that financial incentives matter “less than people think” (although the survey data they present does not really support that), but how they get from there to “and therefore, wealth taxes” is very mysterious.

Well, it’s a pretty big deal, but then again, maybe it’s a big improvement? Aren’t things like early retirement and parents taking more time off good things? And there’s more work and better pay for people who want to work.

But we probably shouldn’t get hung up over where the dividing line is between “a big deal” and “not a big deal.” Binary distinctions are inherently imprecise and disputing them leads to unenlightening arguments.

Not for economic growth/prosperity.

Whether the costs are worth the benefits is subjective & probably depends at least partly on your own circumstances (would this change help you or burden you).

Human labor is not fungible and the extra pay would be more than offset by the higher taxes, so employers and working people would be worse off.

Also please note: the difference between 2% growth and 3% growth is not 1%; it’s 50%(!)

Growth is highly sensitive, and will be the primary determinant of the wellbeing of our grandchildren and their grandchildren.

When you are building something amazing that takes generations of work to inch towards, there are always people who want to eat the seed corn.

Scott had a nice parable here

https://slatestarcodex.com/2017/11/09/ars-longa-vita-brevis/

+1

Good for whom? As measured how?

I would personally call 12% of the American workforce (about 19 million) “many” people. Assuming the self-reporters to be accurate, and that there wasn’t additional qualifying information in the question, I’d say the “many” voters had it right.

Presumably, although it would probably matter a lot how quickly they left.

The labor force participation rate in the US is about 6% lower than it was in 2000 (63.2% vs. 67.3%, 4.1 percentage points). This mostly coincides with bad stuff in the economy during that period.

On the flip side, another 12% of the current labor force exiting would take us down to about 55.6% participation, which would be a low in post-WWII USA, but not by that much – the rate was between 58% and 60% from 1948 to about 1970.

Obviously there’s a lot different between then and now. The biggest difference probably would be the huge influx of women into the labor force between about 1950 and 1990, but also the rate of people completing four years of college went from about 5% to about 35% (keeping them from working for several additional years but presumably increasing their lifetime productivity).

All this is to say that the economy has functioned with various rates of labor participation over the years, so I think it’s not obvious that, for example, slowly losing the least productive eighth of workers would necessarily be catastrophic.

As everyone says, 12% leaving the economy is a big deal, although whether that is good or bad is open to debate.

But really the 12% is a huge guess. As others have said, self-reporting is subject to many flaws. Even when I look into my own head, I don’t really know the answer to this. It depends on so many variables: the current state of my career and whether I think there are more upsides or downsides in the future, the current alternatives I have to living off UBI, my spouse’s career and choices, my needs for money for medical reasons, childcare, etc., and just how I am currently feeling about my job. It could all change next week, and probably will change next year.

I find it curious that people used these results to prove financial incentives don’t really matter.

10% of people admitted they’d quit their job due to basic income. That’s over 15 million people in the United States. Basic income would cause greater net job destruction than the Great Recession!

30% said that if middle class taxes went up substantially, their spouse would quit working. Two in five said they would work substantially less.

Yeah, it’s true that we judge financial incentives as more powerful than perhaps they are, but these are not small numbers. I would have actually guessed the employment impact of basic income would be closer to -2% rather than -10%, for example.

15 million low-wage jobs are not even remotely equivalent to the Great Recession.

What makes you think all the jobs lost would be low-wage jobs?

I, for one, would quit my job and do not hold a low wage job. Since I more or less have to work to earn money and survive I want to both work (1) someplace I am appreciated, and (2) someplace that earns enough to stop working sooner rather than later or allows me to get by working fewer hours. A low wage job wouldn’t fit that criteria. Basic income would address my concerns and allow me to not work.

You would be replaced by somebody. The person who took your job would have quit their previous crap job, but is happier working your job and having your money than not working at all.

The net effect is that the least desirable jobs are the first to be unfilled.

Voluntary and involuntary job destruction are pretty different. For example, if people retired earlier *voluntarily* would that be good or bad?

Could go either way, depending on whether they’re choosing to retire earlier because something has happened to make retirement more attractive, or something has happened to make work less attractive.

I was going to say something similar. 10% of people is “a lot” of people, for at least some definitions of “a lot”, which makes the interpretation weird.

The numbers given don’t feel surprising to me at all. Not saying I would have guessed them correctly in advance or anything, but they don’t come close to making me think financial incentives don’t matter. Rather, they give me a quantifiable first-order baseline for how much financial incentives do matter.

I think you missed the most obvious lazy thought of all: A bunch of people saying they don’t care about money but that other people do is a huge red flag for a hidden preference. Is it possible they’re just saying they don’t care when they’d actually switch?

Overall, I think they’re missing a long term effect. Let’s say you’ve spent twenty years working in finance and working a particular way and all your social status and identity is bound up in that. And then all of a sudden it becomes more lucrative to work as a camgirl or some other low status profession. Will you quit tomorrow and become a camgirl? Maybe not. Maybe never. But a greater proportion of bright young people will and over time the quality of your financial professionals will decrease and of your camgirls will increase.

If that seems far fetched, a similar process happened with computer science. Talk to old computer scientists, the ones who had large portions of their careers before the 1990s (or even earlier). It was not as highly paid or prestigious. Being a computer scientist was mostly the preserve of math nerds and the employment prospects weren’t guaranteed. Many people left computer science for other, better paid fields.

But then financial incentives shifted. Now computer scientists make a lot of money and control some of the most powerful corporations on earth. They were still not prestigious: in fact, analysis from dating sites show that computer programmers score slightly below average as a ‘sexy’ job. And nerd stereotypes are still pretty damn condescending. Hollywood movies about Googlers are often not complimentary. On the other hand, Google and FB and the like have a lot of money. Slowly we’re getting things like Little Big Lies where a bunch of tech workers are being treated like they’re in Mad Men because the money and success has translated into real social power and prestige. It’s on a delay, but it does happen.

You can see numerous other shifts. In fact, the camgirl thing really is happening in some parts of Asia and Eastern Europe. One of the wealthiest women in Romania runs a camgirl site. One of the wealthiest men in Hungary does too. They are actually getting political influence these days.

I think Thiel has a good point here. Remember that a lot of wealth and progress is often created by a minority of very strange people. The more you create complicated rules or redistribute from them to society at large, the more you’re punishing creatives and innovators and rewarding conformity. Because weirdos with a good idea and an incredible work ethic are probably not the popular kids in high school. But they can earn a ton of money. Meanwhile, the handpicked CEO of Morgan Stanley is very good at elite social games. If you ask the Weirdo and Morgan Stanley’s CEO to give up half of their income forever, you’re hurting the Weirdo more than the CEO.

In general, I think we as a society don’t understand the extent to which money doesn’t determine social class. I think this is because we’ve never had a formal titled aristocracy where a poor person whose grandfather was the Count of Bumbleywumbly looked down on a multimillionaire banker. So we imagine that a Harvard professor with all the right friends and a cousin in the Senate is actually less powerful than a working class businessperson just because the businessperson is wealthier.

–From The Notebook of Lazarus Long

This is a very good point. Economists usually are skeptical of self-reported claims about what people will do in certain situations – their answers are subject to all sorts of status-signalling motives, and there is little cost to lying. In fact, when considering behaviors with status considerations, there is evidence that people are more accurate when making predictions about what others will do (e.g. predicting that others will procrastinate) than they are in their predictions about their own behavior (where they vastly underestimate their future procrastination).

I thought I’d read something like that as well, but wasn’t sure where or if my mind was tricking me.

I think an alternate hypothesis is that people have an unrealistically low opinion of others. I can think of cases (voter fraud, drug use by welfare recipients) where policy attempts to solve a problem of people being worse than they actually are.

This is why I called it an obvious and lazy thought. It does bear further investigation but it’s a hypothesis at least as plausible as yours, isn’t it?

@Erusian >

Sounds like a good argument and means to slow down the pace of change to me!

Physically (all the new tower block apartments replacing the homes and businesses that were there for decades) more has changed in the last ten years than in the thirty previous years.

I suppose some teen and twenty somethings like the novelty, but I’m pretty sure the older folks that are dizzy with “future shock” outnumber them.

I approve of the “slow the roll” plan!

I’m genuinely curious how you got that out of what I said. But I could see something like that, yes.

I mean, I wouldn’t say we really want to slow the roll. What we instead want is (rather than protecting some aesthetic sense of comfort) to be assured the changes are good. Thus we could have a system where people who want to make changes are absolutely free to do so but they have to suffer the consequences good and hard. Maybe that’s a billion dollars and a supermodel spouse. Maybe it’s drugged out insanity. But only after we know the results will we implement them in society at large. At least, if such a system could be designed.

Of course, we could also have socialistic community control of any changes. But the issue there is that it will tend towards conservatism and away from innovation or growth.

@Erusian >

I assumed you spoke truly and your prescription would create the results you listed, and since I want the opposite results doing the opposite would have opposite results.

Well I happen to feel that an “aesthetic sense of comfort” promotes mental health, @eric23 linked to a presentation that was pretty convincing that some more constraints and stability than is common in the U.S.A. leads to more happiness.

Yes, that is exactly what I anticipate, and welcome.

If we go too far and induce Cuban levels of stasis than we may liberalize back again, my hope is to dial the rate of change back to the pre-internet era, even just at a 1997 rate would be preferable to the massive disruption we’ve endured lately.

I see. So, my home community has received huge numbers of immigrants, such that Hispanics have gone from about 20-30% of the population when I was born to being about 70% today. Would this also be something you want to turn back the clock on?

Because otherwise my community has been effectively disrupted entirely without technology. I used to be go every Sunday with my father to get corned beef sandwiches and soda at corner delis. Those shops are basically gone: they’ve been replaced by various Hispanic cuisines. Everything has changed: the buildings are different, the cuisine is different, language has changed. (Most of them do learn English but many people speak to each other in Spanish, Spanish is basically required for service positions, and it’s shifted the ways English is spoken). Also, the GDP per capita has declined over the past thirty years because the new immigrants tend to be poor.

It doesn’t bother me just as I’m not against technological disruption. But I certainly know other people it does bother and want to reach something like stasis. We had an election today and one of the candidates was a rather extreme right-wing type that wanted to deport large segments of the population and was pretty open about restoring the city back to its state decades ago by privileging the minority of people that were actually born here. Would you support that in order to maintain the community I was born into?

@Erusian says: “…Would you support that in order to maintain the community I was born into?”

Sounds far too late for that, restoration would disrupt too many kids from the only homes they know.

It’s much the same in my neck of the woods, Hispanics and (to a lesser extent Asians) have largely displaced the African Americans who had been here for decades (they either displaced the Portuguese in some neighborhoods, or the neighborhoods weren’t built yet until WW2), 120 years ago the anglophone “49’ers” displaced the Spanish speaking Peraltake family that owned what are now many cities. Vietnamese immigrants have largely displaced the Chinese-Americans who had previously been there, to a lesser extent Chinese have displaced what had been an Italian neighborhood. Down the highway near San Jose new mostly south Asian immigrants neighborhoods have sprung up on what was once farmland displacing the families that sold the land plus a few mostly Mexican descent farm workers.

But nothing matches the displacement caused by all the college students and graduates who were born elsewhere, while there have always been some (I married one decades back), the sheer scale is epic, they’re like locusts, and there’s no sign yet of the deluge abating.

My first thought to lessen the onslaught is to have a “graduate tax” here to discourage them, but they already do that to themselves with their student loans and how much they bid up housing, yet still they come unrelentingly.

Maybe they are Nobel Prize winners, but this article is very badly argued. I don’t know whether they just wanted to throw some red meat to the readers of the NYT (see the Saez/Zucman article in WaPo that repeats the same stats and data that have been devastated by a number of economists including Larry Summers) or whether the Economics prize has gone the way of Lit and Peace.

In any case if they are right this is very bad news for a carbon tax (and every other behavioral tax). Funny, and I thought they worked. Time to end them all! Start with cigarettes!

But are they right? They compare US athletes with salary cap to European ones with no cap. Which ones are paid more though (on an after tax basis of course)? They don’t say (I have no idea).

That executives don’t work less hard if their pay is reduced does certainly does not cohere with anecdotal personal experience (including my own turn as an executive who moved half way around the world and stopped working solely because of crushing taxes in my preferred country. Retirement is great though.) I wouldn’t mention anecdotal experience but apparently Bannerjee and Duflot have validated gut feelings.

People don’t move to take better jobs — well that’s true, people move much less than they used to. But they need a lot more than just citing that fact to establish that the reason is a mysteriously reduced response to incentives (and the US I think was and still is the country with the greatest internal migration — could be wrong about that).

Re: Carbon taxes. Firms are generally much more responsive than individuals.

They compare US athletes with salary cap to European ones with no

Is this really indicative of anything? Did anyone think that a professional athlete, of all people, is going to run a little less hard because the tax rate is 40% instead of 30%?

Comparing across countries is stupid.

Within the US, tax rates could well matter for where the athlete plays. Establish a residence in Texas and play for the Rangers and pay 0% state tax on all your home games, compared to playing for the Athletics and pay 13%. Anyone attempting to find this effect in performance metrics is smoking dope.

Where you would find it, if anywhere, is how much the Rangers-versus-Athletics needs to pay for an equivalent player. Which involves figuring out what “equivalent” means, which sounds like a lot of work, uggh.

But a baseball player who wants to make a lot of money is playing in the United States regardless of income tax rates, because that is where the baseball market is. If someone wants to make a lot of money in soccer, they are going to Europe. The US Soccer Federation has revenue of about $100 million. The best players in Europe make upwards of $50 million. No tax rate will offset the size of those markets.

A question that has been in my mind since writing this:

Have any baseball teams tried to arrange the pay of their players such that they get paid more for the games in low-tax states? It might be bad PR if your home state is California, but if your home state is Texas maybe your contract gives big bonuses for easy things like signing baseballs for fans before home games.

10% can be “many”. There is not necessarily a paradox here. (Similarly for “would it encourage” in the last question. Doesn’t apply to the third question but there the results are much closer (and also both much lower than I would have expected, guess I have accepted the cosmopolitan lifestyle more than I realized).)

One thing I’ve been trying to do to get a scope on US population statistics is to translate it into states. With 50 states in the union, you just cut the percent in half: 10% is the population of 5 average US states.

The entire population of Tennessee, Georgia, Alabama, Mississippi, and Kentucky combined would certainly count as “many”, no matter how far away 10% is from “most”.

It sometimes seems like every argument being had ever is just an echo of similar contentions brought up for decades. There is a benefit in this – that you can call upon old dead people far more articulate than you to phase your arguments.

My choice of dead guy then would be Milton Friedman. Just replace the phrase “political self-interest” with “social-status” and you have a striking resemblance to Scott’s objection 40+ years prior

@James Banks

‘Technocrats’ have been working very hard on depoliticization in my country and in the EU, by arguing that there are no alternatives to their politics, signing treaties that bind the hands of politicians without the consequences being discussed before the treaties are signed, having judges make policy, choosing what laws to enforce, etc, etc. This kind of elitist control actually has a long history in my country.

Especially in the Dutch lower class and non-rural areas, there is a lot of apathy about politics, but it is an angry apathy: “They don’t care about our interests or needs & we have no power to change it.”

I’m with Aapje here: Democratic politics aren’t great but non-democratic politics would be worse.

Most people against competitive capitalism tend to focus in on, not the abstract idea of competition, but against the results. They point to the people who win in capitalist competition, and say “look at these people and what they do; are we really better off with them?”

Suppose, hypothetically, that the consequence of a competitive health care market is that 40% of the population has to sell themselves into debt slavery to buy medicine to avoid dying before the age of seventy.

If so, then it is not entirely unreasonable to argue that maybe the game’s not worth the price of admission. Or to argue that a noncompetitive system would pay off better in terms of human flourishing. Because sure, not having innovative medical technology is [i]bad[/i]… but being saddled with rent-seekers and having much of the population in debt slavery is [i]worse.[/i]

@Simon_Jester

Against their interpretation of the results, which is far from the same thing, as it usually involves ignoring or misunderstanding important outcomes.

This is a good example. A very strong case can be made that nearly all of us are winners, at least in a ‘having goods and services’ sense, relative to the alternative, but that some merely win more than others.

A typical error I see is that relative losers are equated to absolute losers, even though the two can differ (as in: if I give Bob $100 and Jane $10 million, then Bob is an absolute winner, but relative loser).

It seems pretty telling that you resort to an example that is the opposite of reality. In 1850’s England & Wales, the life expectancy of a 5 year old was 55. Today, it is 80, without debt slavery.

The evidence is very strong that true rent-seeking is actually very low and that technology has increased the rewards for being very talented and reduced the rewards for being less talented, in many fields. In other words, where once someone with 10 talent could give 10 utils to people and someone with 20 talent could give 20 utils to people, it is now more often the case that the person with 10 talent can only give 1 util and the person with 20 talent can give 100 utils to people.

The logical consequence is then that if people are for a large part self-interested util maximizers, they will increasingly want to coerce the people with lots of talent, by giving them money, while decreasingly wanting to coerce those with less talent.

That is not the fault of capitalism, nor something that I’ve seen anyone offer a solution for, other than sacrifice the overall level of utils for more equality in outcomes.

It seems weird that the survey only asked about financial incentives but not about social ones (or maybe this NYT article only reported results about financial incentives; I haven’t looked at the actual papers). If your goal is to determine if financial or social incentives work best, surely your survey should include both types of incentives? Otherwise it’s like an experiment without a control group.

Aren’t all the people who responded “yes” to “many people would do x” correct? In the “would you?” section at least ten percent of the respondents said “Yes, I would do x”. That sounds like “many people” to me.

Or, to put it another way, if someone asked me:

“If there were a universal basic income of $13,000 a year with no strings attached, would many people stop working or stop looking for work?”

I would probably have said “no”. Then if I was told that 10% of the surveyed people said that they would quit their job, then I would move my beliefs more towards “yes”. Not completely, since it is still just a survey, but some.

Good point! The whole headline comparison in that graph of “oh look, people say they won’t respond to incentives as much as they predict others’ will” is certainly plausibly highly misleading.

It would be interesting to know how people actually behave in the situations presented rather than just how they think they would behave. Incentives, financial and otherwise, impact not just behavior but also cognition in powerful and often subtle ways — witness the famous chapter in Freakonomics dealing with real estate agents and their commissions. Charlie Munger presents it well:

One libertarian talking point that I’m only partially convinced of is that financial incentives reduce the incidence of racism. If all you have is “status, dignity, social connections”, there is less incentive to treat people who don’t look like you fairly, but everybody’s money spends the same. The most notorious example is that the railroad company Homer Plessy rode on fought the law mandating segregation.

More recently Uber has made it easier for black people to get rides, and that’s probably not because Travis Kalanick was deeply concerned about the racism of taxi drivers.

There’s a number of pre-employment personality tests based on the principle of asking questions like “Do you believe other people would steal?” and taking the answers as more reflective of the testee’s own predilections than if they’d asked directly “would you steal?”. If these tests are based on reality (a big question mark) then this survey proves the opposite of the headline.

I really hate those tests. I remember having to take several when applying to retail jobs in high school/college. I never got a call from anywhere that required those tests, so I assume I was failing at roughly a 100% rate. The answer to “do you believe other people would steal” is obviously “yes”.

And you certainly don’t want to entrust anyone who said “no” with any responsibility.

Just look up the right answers ahead of time.

I’m sure they’re readily available now, but I’m less confident they were readily available by a simple search in, say, 2002 (could be totally wrong).

I wish I had a better understanding how to reconcile your point 2 in this piece with your support for a universal basic income designed to ease and remove the stigma from a decision not to work. The obvious objection to the latter is that, consistent with the former, the erosion of the societal stigma against voluntary unemployment will cause cascading decisions of the next marginally inclined workers to quit the workforce, adding ever more strain to the demands on the remaining workers, which will in turn further reduce the societal expectations to engage in productive economic activity, producing a vicious cycle.

The robots get better faster than human generations. More voluntary exit from the workforce over time is probably in the features rather than bugs column.

There’s going to be a limit. People who make 200k aren’t going to start quitting their jobs because they get a 13k basic income.

I’m personally not convinced an actually-livable universal income will equilibrate somewhere good yet, but if income inequality keeps going up we will reach that point eventually.

Just wanted to offer a counterpoint to the take on Point Four above that sounds similar to “Great Man” theories on history regarding entrepreneurs. Yes Jobs, Gates, Bezos etc are brilliant businessmen who started mega-empires of businesses, but sometimes these businesses come from breakthroughs originating from Government research like the GPS, so i don’t believe that removing the moonshot financial incentives would stop people making things or starting companies. Arguably, being comfortable for the rest of your life is a floor, and after that it just becomes a number for comparing power and status and becomes excessive.

Some people, myself included, just enjoy and feel the compulsion to make things. Perhaps due to the social incentives of being known as someone who makes things, but also just for the sake of creation itself. For every operating system that redefines how computers work there’s cases like Volvo giving away the patent for the three-point seat belt. This is undeniably an advancement and boon to society that wasn’t incentivised by money.

I also don’t believe that 99% of important ideas start out on the lunatic fringe. I think it would be 1% of ideas that end up as revolutionary and important start there, with the vast majority of good ideas starting off as an iteration of something that was already a good idea. Take most of science for example. Researchers get paid a pittance compared to other industries doing ground-breaking work but they do it because they might get to name something after themselves one day, i.e. social renown. Arguably most of science is taking existing ideas and trying to go a step further. Not coming at things from the lunatic fringe trying to revolutionise.

This is a genuinely surprising assumption for me to see. My priors are that if you get ten different Nobel-winning economists in a room and ask them questions any more complicated than “is supply and demand real?” you will get ten different answers. It’s not as bad as social science where you’d get eleven answers, but this ain’t physics. Economics? You can prove anything with economics.

Another alternate explanation is that this is instance number ten million of “everyone thinks they’re above average”. Most people think they’re more hardworking or less tax-evadey than others and they don’t even have to be lying, just following whatever broken cognitive process leads them to think they’re a good driver.

It’s not quite that bad. See http://www.igmchicago.org

The simpler explanation is that the Economic Nobel prize is not a real Nobel prize. It was not included in Nobel’s will, and was just tacked onto the other prices. The name is not the same. The regular Nobels are just called “The Nobel Prize in Chemistry”, while the Economic one is “The Sveriges Riksbank Prize in Economic Sciences in Memory of Alfred Nobel”. So the accurate name would be the Sveriges Riksbank Prize.

The Sveries.

The economic prize is awarded by the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences, just like the Nobels for chemistry and physics. It probably makes more sense to split up the Nobels by who awards them:

Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences: chemistry, economics and physics

Nobel Assembly at the Karolinska Institute: physiology or medicine

Swedish

RapistsAcademy: literatureNorwegian Nobel Committee: peace

I don’t think the founding father of the prizes would like this! Also this would put the Craafordies, Sjobergies, Schockies, Aminoffies and Tobiases prizes in the same standing as the Nobels, economic and not economic.

The Nobel prizes seem like an anachronism to me, with their focus on individuals, whose main ‘value’ is as a mediocre PR mechanism for science.

IMO, the best approach is just to not take them very seriously.

What exactly is explained by the fact that the economics prize was established by someone other than a dynamite manufacturer?

It’s named that way in order to mislead people into giving it the prestige of the dynamite manufacturer. If you don’t think the dynamite manufacturer deserves that prestige, misleading is still misleading. You shouldn’t justify deceit on the grounds that the thing that people are being deceived about is something they shouldn’t care about anyway.

(Emphasis added.)

{Citation needed.}

Why else would they name it the Sveriges Riksbank Prize in Economic Sciences in Memory of Alfred Nobel, at a point in time when the Nobel prizes were very prestigious? If I start a new company called Walmart Fishing Supplies, is it credible that I’m not trying to piggyback off the brand recognition of the well-known supermarket?

Why else? You yourself gave the answer: they’re given out by the same organization that awards some of the other prizes (and at the same ceremony as all of them save the Peace Prize)– a natural extension of their “brand”, if you will. The original complaint is analogous to complaining that Walmart Corp. is trying to bamboozle us into thinking each new Walmart has been personally founded by Sam Walton.

Nobel has prestige because of the prizes, not the other way around. And the prizes have prestige because they generally do a good enough job of picking recipients that people actually working in the various fields regard a Nobel as the highest honor that can come their way. This is every bit as true of the economics Nobel as any of the others.

Interestingly, the Nobel website’s FAQ states that they won’t adopt more prizes, suggesting that they regretted adopting the Sveriges Riksbank Prize.

In this case, its less of a put a bunch of economists in a room and you’ll get a bunch of different answers and more of a “we are writing for politicians, so the truth does not matter.” Its just them using their recent nobel prize to push their political agenda and assuming that politicians will not be able to tell that they are being deliberately misleading.

YES!

I think progressives vastly underestimate how important incentives are to the bottom 4 quintiles, and conservatives overestimate how important they are to the top decile. I think I agree with Duflo and Banerjee that many of the highest paid people are very ambitious and strongly desire to be the best, so they are mostly competing for relative status, not so much their net income. In that case I could see very little deadweight loss from higher tax rates on the top few percent (I’m not sure just how high would be too high, or where to draw the line though).

But they are completely out to lunch just believing some garbage questions that people give false responses to in a survey. Not to mention their explanation of the responses seems to mischaracterize what the responses actually show. e.g. “Seventy-two percent of them declared that an increase in taxes would “not at all” lead them to stop working.” Ok…stop doesn’t mean work fewer hours… so that means that 28 percent of people would quit working if their taxes went up? Maybe they’re just terrible writers that cannot communicate effectively, I don’t know. But then when you look at their chart it completely contradicts what they actually say. Are they intentionally trying to mislead people?! Or, do their survey results give completely contradictory responses? Either way you shouldn’t put too much faith in it.

e.g. “If tax rates went up for you/the middle class, would it encourage…[quitting work/working less?]”

It looks like about 40% of people even admit they would work less if their taxes went up! And remember, a substantial portion of these people are living in a world with relatively fixed schedules and may not be easily able to work less than the standard full-time shift they are employed for.

And then approximately 35% were not expected to work less, implying that the income effect dominates the substitution effect to leisure (or else we should expect 100% of people to be “encouraged” aka incentivized to work less!).

Also, every time someone cites a UBI “experiment” or something like it, you can never let them make any kind of conclusion about how it affects long run labor supply. Of course people didn’t quit their jobs or reduce their hours much (again, even assuming they could reduce them much!) when they got what THEY KNEW was a TEMPORARY income boost. Their lifetime expected income was barely changed, so of course their labor supply should barely change. That provides us with basically no information on how labor supply will change in the long run (e.g. for future generations) when people react to very significant permanent (expected to be, anyway) changes in the welfare and tax structure. I think looking at Europe shows us persuasive evidence that at least in the long run, incentive effects are very powerful and substantially reduce labor output for the vast majority of the population.

Honestly, I’m not sure if Duflo and Banerjee are just trolling, or just ignorant in that article. I’m very disappointed because I thought Poor Economics was an amazing book.

I was about to say the same thing. The casino income study is slightly better proof, but…one study.

The deadweigh loss doesn’t come mostly from the behavioral changes of the person taxed but from the moving of resource allocation from someone competent to someone incompetent (bureaucrat).

I don’t think that’s right? Aren’t deadweight losses by definition the result of behavioral changes on the part of the transacting parties?

The way I heard someone put it is that we have never studied UBI but we do have a lot of data on what happens if you spread your cash transfer program’s payouts across several years.

Some thoughts:

• If some people respond better to financial incentives than others, I’d expect people who respond better to financial incentives to be more likely to try to get high-paying jobs, and therefore be overrepresented in such jobs. If this effect is strong enough, the point about tax evasion and Wall Street bonuses might not apply, since it may be that wealthy people and Wall Street people are particularly likely to care about financial incentives.

(If this is true, this could also suggest companies might care less about prioritizing profits over other things if executives were paid less and therefore weren’t selected for caring about financial incentives. I don’t know how strong of an effect that would be, though, and whether it would be worthwhile overall.)

• Even if tax evasion is not accepted in society in general, it might be accepted among wealthy people the same way music piracy is accepted among teenagers.

One thing I see mentioned on twitter in certain circles is the idea that “status is zero sum, while wealth/money etc. isn’t”.

People paint the picture of the 1% or whatever gaining wealth at the expense of others, but that’s not necessarily true. Often they (whoever ‘they’ is – entrepreneurs? Business owners?) add to the overall size of the pie.

Status, on the other hand, usually means someone holds a position at the expense of others.

Not sure that’s true. High status people can use status to increase the size of that niche, allowing more high status positions, without decreasing the number in other niches. Most apparent in the arts, I would think.

I’d argue there’s some kind of Dunbar number but for famous people we can remember. Every time someone new rises to a high status position it does decrease the number of others in that niche in that they become less relevant. How many artists are desperately chasing the shadow of their past success?

A complication: there are many different status hierarchies. There’s one for each sport, game, and league. There’s one for the politics of each country, region, and city. There’s one for each industry and career path. There’s one for each kind of art, hobby, craft, lifestyle, ideology, and philosophy. There are literal hier-archies of priests in many different religions. My husband will pay good money to attend a live interview of a prestigious actor whom I’ve never heard of and don’t care about; I may have instead gone to a meetup with a blogger in attendance that he didn’t care about. 😀

Then there is the meta-game where people who are good at climbing social hierarchies try to reduce the number of the hierarchies (because the profit from being at the top is greater when the entire hierarchy is greater), and people who suck at climbing social hierarchies try to create their own (where even at the bottom they won’t be too deep).

For example, the forbidden topic where the gamers want to be left alone, and the socially powerful people insist that they are not allowed to, because there is too much money to be extracted. (“What a nice game you have here. Wouldn’t it be a shame if someone with really good social connections publicly accused you of being sexist?”)

How do you differentiate between:

1) People who want to invade your hierarchy from outside, and want to change the rules in order to more effectively conquer your hierarchy?

2) People who already live in your hierarchy, but want to change the rules in ways they consider more appropriate, say because it results in their head getting stepped on less?

Like, women who play video games are part of the gamer hierarchy. If they say “having all the female characters strut around in bikinis is sexist,” is it because they’re socially adept hierarchy-climbers trying to not allow gamers to have a separate hierarchy? Or is it because they actually don’t like having all the female characters strut around in bikinis?

Are they a conspiracy of people high up another hierarchy who want to grind you under their boot heel by changing rules that are necessary to keep you from getting hurt?

Or are they an internal movement of people low down in your hierarchy who want to change rules that are necessary to keep them from getting hurt?

How do you tell those cases apart?

Pretty much all environments have people who want to push the environment in a direction, where different people want different directions. Some want more bikinis in games, some want less. Some want more hardcore technical topics at conferences, some less. Some want vegan food, others want a roasted whole pig. Etc, etc.

The liberal solution to such disagreements is to allow the organizers of an environment to set their rules, so people can self-select into the environments they like (which typically requires compromising) and make new spaces if they dislike the existing ones.

Invaders don’t make new spaces and do all the required hard work, but try to hijack existing spaces or worse, try to make and enforce rules for all spaces.

What I object to, is exactly this kind of hyperbole, where people who voluntarily enter a space with certain norms and values, demand a change to those norms and values for their own well-being (and/or status), without recognizing that this in turn reduces the well-being (and/or status) of others.

If I hate loud music and go to a loud nightclub, the people running the club are not “grind[ing me] under their boot heel.” I crawled under their boot.

I’m perfectly free to seek out or start a nightclub that fits my preferences/needs. If that is not feasible because too few people want to participate (with money and/or their presence) than it sucks that my preferences are too peculiar, but complaining that this is oppression, is actually a sense of entitlement to the money, time, etc of others.

Ultimately, illiberalism pretty much always seems to distill down to a sense of entitlement and/or unwillingness/inability to empathize with others.

The traditional solution to “some people want girls in bikinis in video games, and some don’t” is the same as “some people prefer vanilla ice cream, and some prefer chocolate”. Let people produce whichever they want, and buy whichever they want.

I don’t organize protests against Harlequin Romance novels. Not because I wouldn’t think they contain harmful gender stereotypes (if a man isn’t a pirate captain, a billionaire, or a vampire, obviously he is unworthy of love), but because I realize I am not the target audience. I also don’t write angry articles about how dildo sizes create unrealistic expectations and therefore the industry should be regulated. I respect other people’s right to have their fantasies. Are you the kind of pervert who puts a pineapple on their pizza? Not my concern.

There are tons of games not containing girls in bikinis. (There are also games containing muscular guys. Who cares?) And there is always the option to create your own game. The tools are available for free; sometimes you only have to add a few pictures and texts. Kids can do that, and they literally do; there are game-making competitions for high-school kids. Being the change you want to see is very easy here.

By the way, there were famous games with female protagonists / made by women / played mostly by women long before social justice decided to liberate the gaming for women.

If you are an insider, you sometimes recognize the people who go like: “How do you do, fellow kids?” They keep making all kinds of mistakes which show their unfamiliarity with the subculture.

Another way to tell the difference is ex post, when after the people succeeded to change the subculture according to their wishes, they leave it. Which is the opposite of what a person who wants to make the subculture more comfortable for themselves would do. We don’t see people who fighted against girls in bikinis in video games creating new video games without girls in bikinis. (Neither we see the Atheism+ people fighting against religion in general.)

One of the most prominent anti-gamer gaters, Brianna Wu, created a game that looks like this.

So I’m not sure that they truly care about ‘objectification’. In general, there seems to be a lot of: ‘I can do X because I’m oppressed, you can’t do X because you are an oppressor.’

To be fair, the problem that many of these people seem to have is an immense lack of talent.

On point four: Well said!

To briefly expand on your point, I think a lot of the problems that those opposed to “capitalism” attribute to it are not problems caused by markets, but pre-existing problems that are actually restrained by competitive markets. Remove the market or the competition and the problem will intensify, not lessen. Look at all the dysfunctions discussed in moral mazes — are these caused by the company’s need to earn a profit? No! These behaviors are hurting the company, not helping it. The problem isn’t the market, the problem is that the managers have managed to protect themselves from its workings; turn up the heat and the company either throws them out on their asses or it dies. They’re nothing but a bunch of courtiers — and you don’t need a market to be plagued with those.