[Epistemic status: I am basing this on widely-accepted published research, but I can’t guarantee I’ve understood the research right or managed to emphasize/believe the right people. Some light editing to bring in important points people raised in the comments.]

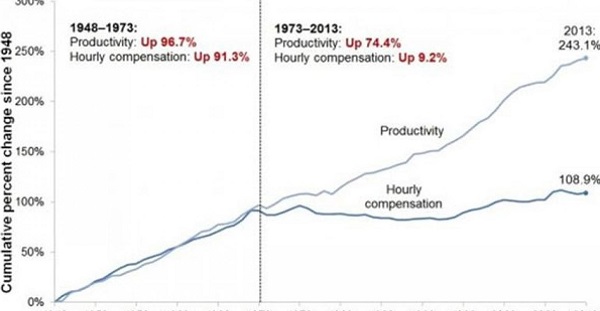

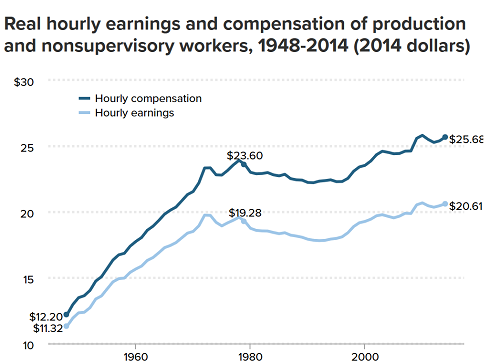

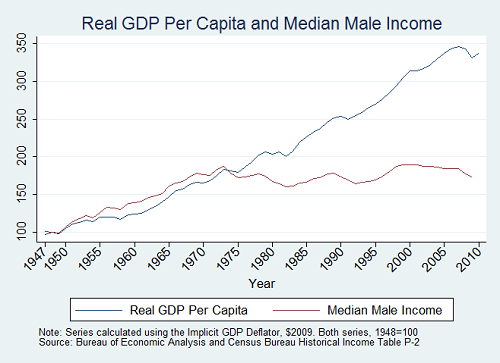

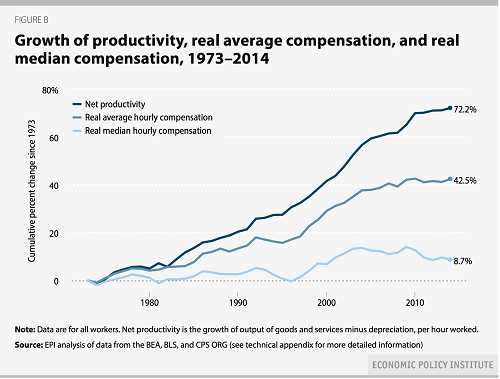

You all know this graph:

Median wages tracked productivity until 1973, then stopped. Productivity kept growing, but wages remained stagnant.

This is called “wage decoupling”. Sometimes people talk about wages decoupling from GDP, or from GDP per capita, but it all works out pretty much the same way. Increasing growth no longer produces increasing wages for ordinary workers.

Is this true? If so, why?

1. What Does The Story Look Like Across Other Countries And Time Periods?

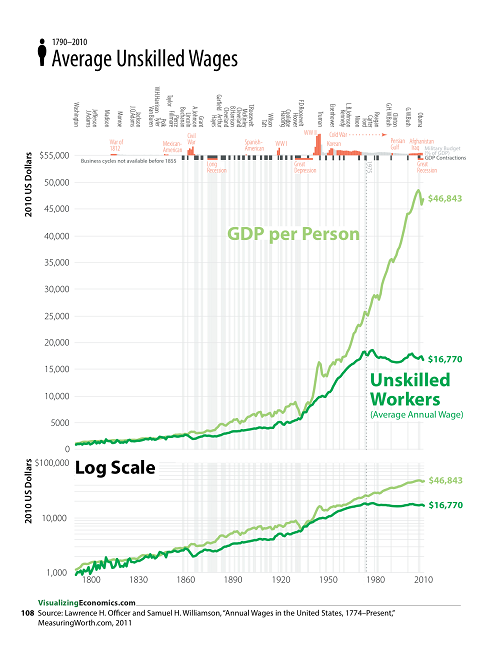

Here’s a broader look, from 1800 on:

It no longer seems like a law of nature that productivity and wages are coupled before 1973. They seem to uncouple and recouple several times, with all the previous graphs’ starting point in 1950 being a period of unusual coupledness. Still, the modern uncoupling seems much bigger than anything that’s happened before.

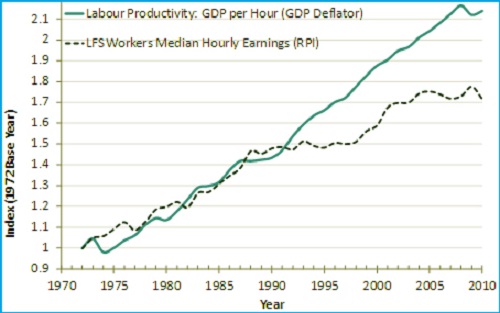

What about other countries? This graph is for the UK (you can tell because it spells “labor” as “labour”)

It looks similar, except that the decoupling starts around 1990 instead of around 1973.

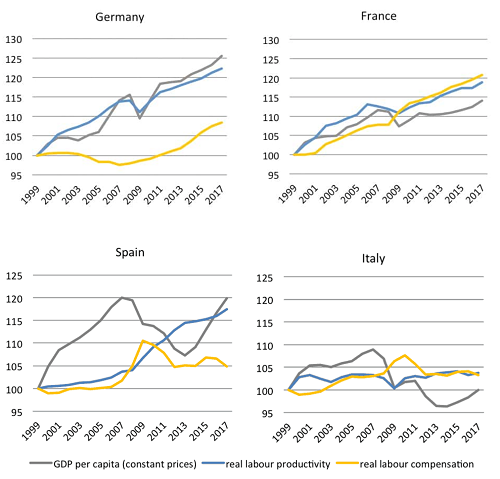

And here’s Europe:

This is only from 1999 on, so it’s not that helpful. But it does show that even in this short period, France remains coupled, Germany is decoupled, Spain is…doing whatever Spain is doing, and Italy is so pathetic that the problem never even comes up. Overall not sure what to think about these.

2. Could Apparent Wage Decoupling Be Because Of Health Insurance?

Along with wages, workers are compensated in benefits like health insurance. Since health insurance has skyrocketed in price, this means total worker compensation has gone up much more than wages have. This could mean workers are really getting compensated much more, even though they’re being paid the same amount of money. This view has sometimes been associated with economist Glenn Hubbard.

There are a few lines of argument that suggest it’s not true.

First, wage growth has been worst for the lowest-paid workers. But the lowest-paid workers don’t usually get insurance at all.

Second, the numbers don’t really add up. Median household income in 1973 was about $48,000 in today’s dollars. Since then, productivity has increased by between 70% and 140% (EVERYBODY DISAGREES ON THIS NUMBER), so if median income had kept pace with productivity it should be between $82,000 and $115,000. Instead, it is $59,000. So there are between $23,000 and $67,000 of missing income to explain.

The average health insurance policy costs about $7000 per individual or $20000 per family, of which employers pay $6000 and $14000 respectively. But as mentioned above, many people do not have employer-paid insurance at all, so the average per person cost is less than that. Usually only one member of a household will pay for family insurance, even if both members work; sometimes only one member of a household will buy insurance at all. So the average cost of insurance to a company per employee is well below the $6000 to $14000 number. If we round it off to $6000 per person, that only explains a quarter of the lowest estimate of the productivity gap, and less than a tenth of the highest estimate. So it’s unlikely that this is the main cause.

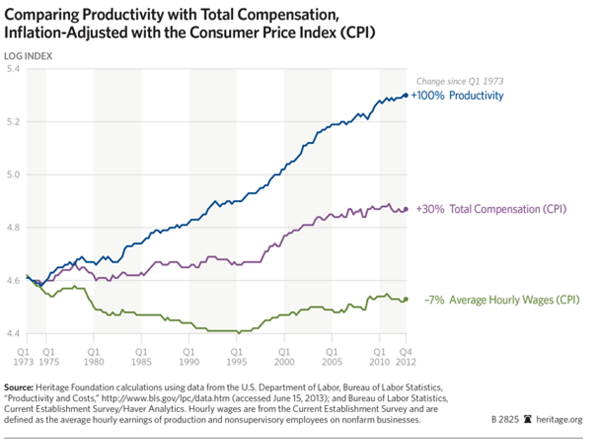

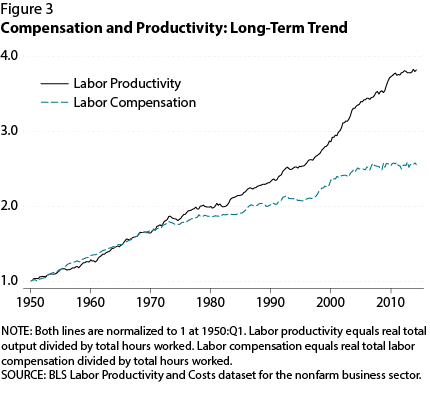

Third, some people have tried measuring productivity vs. total compensation, with broadly similar results:

The first graph is from the left-wing Economic Policy Institute, whose bias is towards proving that wage stagnation is real and important. The second graph is from the right-wing Heritage Foundation, whose bias is towards proving that wage stagnation is fake and irrelevant. The third graph is from the US Federal Reserve, a perfectly benevolent view-from-nowhere institution whose only concern is the good of the American people. All three agree that going from earnings to total compensation alone closes only a small part of the gap. The EPI also mentions that most of the difference between earnings and compensation opened up in the 1960s and stayed stable thereafter (why? haven’t health insurance costs gone up more since then), which further defeats this as an explanation for post-1973 trends.

We shouldn’t dismiss this as irrelevant, because many things that close only a small part of the gap may, when added together, close a large part of the gap. But this doesn’t do much on its own.

3. Could Apparent Wage Decoupling Be An Artifact Of Changing Demographics?

The demographics of the workforce have changed a lot since 1973; for example, more workers are women and minorities. If women and minorities get paid less, then as more of them enter the workforce, the lower “average” wages will go (without any individual getting paid less). If they gradually enter the workforce at the same rate that wages are increasing, this could look like wages being stagnant.

But if we disaggregate statistics by race and gender, we don’t see this. Here’s average male wage over the relevant time period:

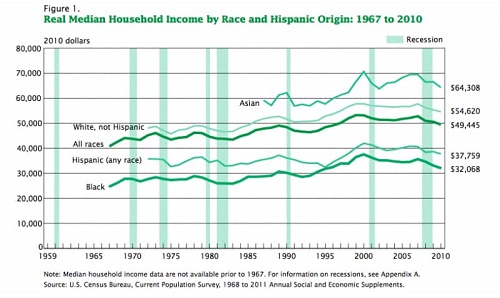

And here’s average income disaggregated by race:

The patterns for whites and men are the same as the general pattern.

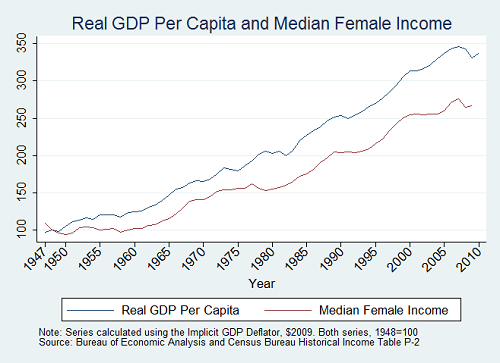

There is one unusual thing in this area. Here’s the pattern for women:

Women’s income is rising at almost the same rate as productivity! This is pretty interesting, but as far as I can tell it’s just because women’s career prospects have been improving over time because of shifting cultural attitudes, affirmative action, and the increasing dominance of female-friendly service and education-heavy jobs. I’m not sure this has any greater significance.

Did increased female participation in the workforce increase the supply of labor and so drive the price of labor down? There’s a tiny bit of evidence for that in the data, which show female workforce participation started rising much faster around 1973, with a corresponding increase in total workforce. But this spurt trailed off relatively quickly, and female participation has been declining since about 2000, and the wage stagnation trend continues. I don’t want to rule out the possibility that this was part of what made 1973 in particular such a strong inflection point, but even if it was, it’s long since been overwhelmed by other factors.

4. Could Apparent Wage Decoupling Be An Artifact Of How We Measure Inflation?

Martin Feldstein is a Harvard economics professor, former head of the National Bureau of Economic Researchers, former head of the President’s Council of Economic Advisors, etc. He believes that apparent wage stagnation is an artifact of mismeasurement.

His argument is pretty hard for me to understand, but as best I can tell, it goes like this. In order to calculate wage growth since 1973, we take the nominal difference in wages, then adjust for inflation. We calculate wage inflation with something called the Consumer Price Index, which is the average price of lots of different goods and services.

But in order to calculate productivity growth since 1973, we use a different index, the “nonfarm business sector output price index”, which is based on how much money companies get for their products.

These should be similar if consumers are buying the same products that companies are making. But there can be some differences. For example, if you’re looking at US statistics only, then some businesses may be selling to foreign markets with different inflation rates, and some consumers may be buying imported goods from countries with different inflation rates. Also (and I’m not sure I understand this right), if people own houses, CPI pretends they are paying market rent to avoid ignoring housing costs, but PPI doesn’t do this. Also, PPI is not as good at including services as CPI. So consumer and producer price indexes differ.

In fact, consumer inflation has been larger than producer inflation since 1973. So when we adjust wages for consumer inflation, they go way down, but when we adjust productivity for producer-inflation, it only goes down a little. This means that these different inflation indices make it look like productivity has risen much faster than wages, but actually they’ve risen the same amount.

As per Feldstein:

The level of productivity doubled in the U.S. nonfarm business sectorbetween 1970 and 2006. Wages, or more accurately total compensation per hour, increased at approximately the same annual rate during that period if nominal compensation is adjusted for inflation in the same way as the nominal output measure that is used to calculate productivity.

More specifically, the doubling of productivity represented a 1.9 percent annual rate of increase. Real compensation per hour rose at 1.7 percent per year when nominal compensation is deflated using the same nonfarm business sector output price index. In the period since 2000, productivity rose much more rapidly (2.9 percent ayear) and compensation per hour rose nearly as fast (2.5 percent a year).

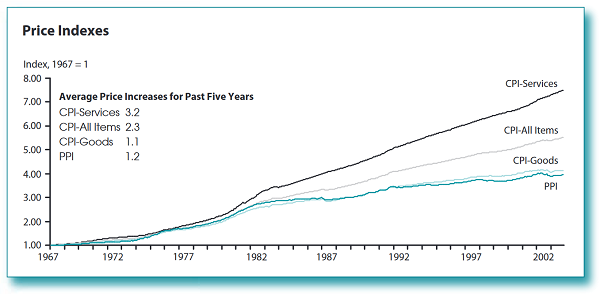

Why is the CPI increasing so much faster than business-centered inflation indices?

The Federal Reserve blames tech. The services-centered CPI has comparatively little technology. The goods-heavy PPI (a business-centered index of inflation) has a lot of it. Tech is going down in price (how much did a digital camera cost in 1990? How about now?) so the PPI stays very low while the CPI keeps growing.

How much does this matter?

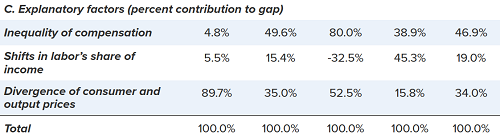

The left-leaning Economic Policy Institute says it explains 34% of wage decoupling:

The right-leaning Heritage Foundation says it explains more:

If we estimate the size of the gap as 70 pp (between total compensation CPI and productivity), switching to the top IPD measure closes 67% of the gap; switching to the PCE measure explains 37% of the gap. I’m confused because the EPI is supposedly based on Mishel and Gee, who say they have used the GDP deflator, which is the same thing as the IPD which the Heritage Foundation says they use. I think the difference is that Mishel and Gee haven’t already applied the change from wages to total compensation when they estimate percent of the gap closed? But I’m not sure.

One other group has tried to calculate this: Pessoa and Van Reenan: Decoupling Of Wage Growth And Productivity Growth? Myth And Reality. According to a summary I read, they believe 40% of wage decoupling is because of these inflation related concerns, but I have trouble finding that number in the paper itself.

And the CBO looks into the same issue. They’re not talking about it relative to productivity, but they say that technical inflation issues mean that the standard wage stagnation story is false, and wages have really grown 41% from 1979 – 2013. Since productivity increased somewhere between 70% and 100% during that time, this seems similar to some of the other estimates – inflation technicalities explain between 1/3 and 2/3 of the problem.

Everyone I read seems to agree this issue exists and is interesting, but I’m not sure I entirely understand the implications. Some people say that this completely debunks the idea of wage decoupling and it’s actually only half or a third what the raw numbers say. Other people seem to agree that a big part of wage decoupling is these inflation technicalities, but suggest that although they have important technical implications, if you want to know how the average worker on the street is doing the CPI is still the way to go.

Superstar economist Larry Summers (with Harvard student Anna Stansbury) comes the closest to having a real opinion on this here:

When investigating consumers’ experienced rise in living standards as in Bivens and Mishel (2015), a consumer price deflator is appropriate; however, as Feldstein (2008) argues, when investigating factor income shares a producer price deflator is more appropriate because it reflects the real cost to firms of employing workers.

I am a little confused by this. On the one hand, I do want to investigate consumers’ experienced rise (or lack thereof) in living standards. This is the whole point – the possibility that workers’ living standards haven’t risen since 1973. But most people nowadays work in services. If you deflate their wages with an index used mostly for goods, are you just being a moron and ensuring you will be inaccurate?

Summers and Stansbury continue:

Lawrence (2016) analyzes this divergence more recently, comparing average compensation to net productivity, which is a more accurate reflection of the increase in income available for distribution to factors of production. Since depreciation has accelerated over recent decades, using gross productivity creates a misleadingly large divergence between productivity and compensation. Lawrence finds that net labor productivity and average compensation grew together until 2001, when they started to diverge i.e. the labor share started to fall. Many other studies also find a decline in the US labor share of income since about 2000, though the timing and magnitude is disputed (see for example Grossman et al 2017, Karabarbounis and Neiman 2014, Lawrence 2015, Elsby Hobijn and Sahin 2013, Rognlie 2015, Pessoa and Van Reenen 2013).

If I intepret this correctly, it looks like it’s saying that the real decoupling happened in 2000, not in 1973. I see a lot of papers saying the same thing, and I don’t understand where they’re diverging from the people who say it happened in 1973. Maybe they’re using Feldstein’s method of calculating inflation? I think this must be true – if you look at the Heritage Foundation graph above, “total compensation measured with Feldstein’s method” and productivity are exactly equal to their 1973 level in 2000, but diverge shortly thereafter so that today compensation has only grown 77% compared to productivity’s 100%.

Nevertheless, Summers and Stansbury go on to give basically exactly the same “Why have wages been basically stagnant since 1973? Why are they decoupled from productivity?” narrative as everyone else, so it sure doesn’t look like they think any of this has disproven that. It looks like maybe they think Feldstein is right in some way that doesn’t matter? But I don’t know enough economics to figure out what that way would be. And it looks like Feldstein believes his rightness matters very much, and other economists like Scott Sumner seem to agree. And I cannot find anyone, anywhere, who wants to come out and say explicitly that Feldstein’s argument is wrong and we should definitely measure wage stagnation the way everyone does it.

My conclusions from this section, such as they are, go:

1. Arcane technical points about inflation might explain between 33% and 66% of the apparent wage stagnation/decoupling.

2. “Explain” may not mean the same as “explain away”, and it’s not completely clear how these points relate to anything we care about

5. Could Wage Decoupling Be Explained By Increasing Labor-Vs-Capital Inequality?

Economists divide inequality into two types. Wage inequality is about how much different wage-earners (or salary-earners, here the terms are used interchangeably) make relative to each other. Labor-vs-capital inequality is about how much wage earners earn vs. how much capitalists get in profits. These capitalists are usually investors/shareholders, but can also be small business owners (or, sometimes, large business owners). Since tycoons like Jeff Bezos and Mark Zuckerberg get most of their compensation from stocks, they count as “capitalists” even if they are paid some token salary for the work they do running their companies.

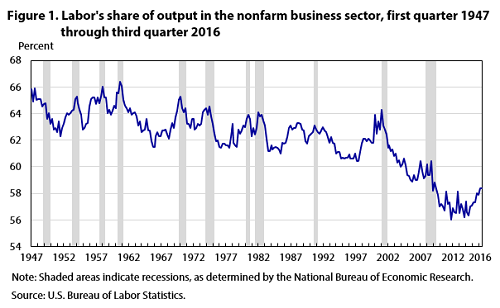

Here is the labor-vs-capital split for the US over the relevant time period; note the very truncated vertical axis:

This type of inequality was about the same in the early 1970s as in the early 2000s, and has no clear inflection point around 1973, so it probably didn’t start this trend off. But it did start seriously decreasing around 2000, the same time people who use the more careful inflation methodology say wages and productivity really decoupled. And obviously labor getting less money in general is the sort of thing that makes wages go down.

Why is labor-vs-capital inequality increasing? For the long story, read Piketty (my review, highlights, comments). But the short story includes:

Today’s wage inequality is tomorrow’s labor-vs-capital inequality. If some people get paid more than others, they can invest, their savings will compound, and they will have more capital. As wage inequality increases (see below), labor-vs-capital inequality does too.

The tech industry is more capital-intensive than labor-intensive. For example, Apple has 100,000 employees and makes $250 billion/year, compared to WalMart with 2 million employees and $500 billion/year – in other words, Apple makes $2.5 million per employee compared to Wal-Mart’s $250,000. Apple probably pays its employees more than Wal-Mart does, but not ten times more. So more of Apple’s revenue goes to capital compared to Wal-Mart’s. As tech becomes more important than traditional industries, capital’s share of the pie goes up. This is probably a big reason why capital has been doing so well since 2000 or so.

There’s an iconoclastic strain of thought that says most of the change in labor-vs-capital is just housing. Houses count as capital, so as housing costs rise, so does capital’s share of the economy. Read Matt Ronglie’s work (paper, summary, Voxsplainer) for more. Since houses are neither involved in corporate productivity nor in wages, I’m not sure how this affects wage-productivity decoupling if true.

Whatever the cause, the papers I read suggest that increasing labor-vs-capital inequality explains maybe 10-20% of of decoupling, almost all concentrated in the 2000 – present period.

6. Could Wage Decoupling Be Explained By Increasing Wage Inequality?

The other part of the two-pronged inequality picture above. This one seems more important.

One way economists look at this is in the difference between the median wage and the average wage:

Add in the other things we talked about – the health insurance, the inflation technicalities, the declining share of labor – and the “””average””” worker is doing almost as well as they were in 1973. In fact, this is almost tautologically true. If the entire pie is growing by X amount, and labor’s relative share of the pie is staying the same, then labor should be getting the same absolute amount, and (ignoring changes in the number of laborers) the average laborer should get the same amount.

So the decline in median wage is a mean vs. median issue. A few high-earners are taking a lot of the pie, keeping the mean constant but lowering the median. How high?

Remember, productivity has grown by 70-100% through this period. So even though the top 5% have seen their incomes grow by 69%, they’re still not growing as fast as productivity. The top 1% have grown a bit faster than productivity, although still not that much. The top 0.1% are doing really well.

This is generally considered the most important cause of wage stagnation and wage decoupling, other than among the iconoclasts who think the inflation issues are more important. Above, I referred to a few papers that tried to break down the importance of each cause. EPI thinks wage inequality explains 47% of the problem. Pessoa and Van Reenen think it explains more like 20% according to Mishel’s summary (my eyeballing of the paper suggests more like 33%, but I am pretty uncertain about this).

7. Is Wage Inequality Increasing Because Of Technology?

Here’s one story about why wage inequality is increasing.

In the old days, people worked in factories. A slightly smarter factory worker might be able to run the machinery a little better, or do something else useful, but in the end everyone is working on the same machines.

In the modern economy, factory workers are being replaced by robots. This creates very high demand for skilled roboticists, who get paid lots of money to run the robots in the most efficient way, and very low demand for factory workers, who need to be retrained to be fast food workers or something.

Or, in the general case, technology separates people into the winners (the people who are good with technology and who can use it to do jobs that would have taken dozens or hundreds of people before) and the losers (people who are not good with technology, and so their jobs have been automated away).

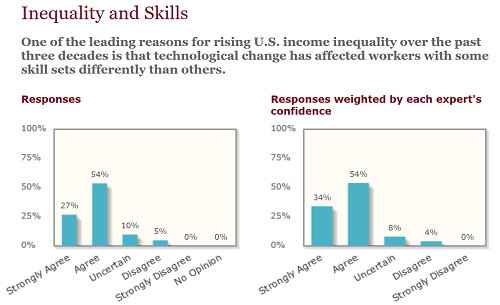

From an OECD paper:

Common explanations for increased wage inequality such as skill-biased technological change and globalisation cannot plausibly account for the disproportionate wage growth at the very top of the wage distribution. Skill-biased technological change and globalisation may both raise the relative demand for high-skilled workers, but this should be reflected in broadly rising relative wages of high-skilled workers rather than narrowly rising relative wagesof top-earners. Brynjolfsson and McAfee (2014) argue that digitalisation leads to “winner-takes-most” dynamics, with innovators reaping outsize rewards as digital innovations are replicable at very low cost and have a global scale. Recent studies provide evidence consistent with “winner-take-most” dynamics, in the sense that productivity of firms at the technology frontier has diverged from the remaining firms and that market shares of frontier firms have increased (Andrews et al., 2016). This type of technological change may allow firms at the technology frontier to raise the wages of its key employees to “superstar” levels.

It…sounds like they’re saying that technological change can’t be the answer, then giving arguments for why the answer is technological change.

I think this is just the authors’ poor writing skills, and that the real argument is less confusing. The Huffington Post is surprisingly helpful, describing it as:

What this means is that skilled professionals are not just winning out over working class stiffs, but the richest of the top 0.01 percent are winning out over the professional class as a whole.

That Larry Summers paper mentioned before becomes relevant here again. It argues that wages and productivity are not decoupled – which I know is a pretty explosive thing to say three thousand words in to an essay on wage decoupling, but let’s hear him out.

He argues that apparent decoupling between productivity and wages could result either from literal decoupling – that is, none of the gains of increasing productivity going to workers – or from unrelated trends – for example, increasing productivity giving workers an extra $1000 at the same time as something else causes workers to lose $1000. If a company made $1000 extra and the boss pocketed all of it and didn’t give workers any, that would be literal decoupling. If a company made $1000 extra, it gave workers $1000 extra, but globalization means there’s less demand for workers and so salaries would otherwise have dropped by $1000, so now they stay the same, that’s an unrelated trend.

Summers and Stansbury investigate this by seeing if wages increase more during the short periods between 1973 and today when productivity is unusually high, and if they stagnate more (or decline) during the short periods when it is unusually low. They find this is mostly true:

We find substantial evidence of linkage between productivity and compensation: Over 1973–2016, one percentage point higher productivity growth has been associated with 0.7 to 1 percentage points higher median and average compensation growth and with 0.4 to 0.7 percentage points higher production/nonsupervisory compensation growth.

S&S are very careful in this paper and have already adjusted for health insurance issues and inflation calculation issues. They find that once you adjust for this, productivity and wages are between 40% and 100% coupled, depending on what measure you use. (I don’t exactly understand the difference between the two measures they give; surely taking the median worker is already letting you consider inequality and you shouldn’t get so much of a difference by focusing on nonsupervisory workers?) As mentioned before, they finds the coupling is much less since 2000. They also find similar results in most other countries: whether or not those countries show apparent decoupling, they remain pretty coupled in terms of actual productivity growth:wage growth correlation.

They argue that if technology/automation were causing rising wage inequality or rising labor-capital inequality, then median wage should decouple from productivity fastest during the periods of highest productivity growth. After all, productivity growth represents the advance of labor-saving technology. So periods of high productivity growth are those where the most new technology and automation are being deployed, so if this is what’s driving wages down, wages should decrease fastest during this time.

They test this a couple of different ways, and find that it is false before the year 2000, but somewhat true afterwards, mostly through labor-capital inequality. They don’t really find that technology drives wage inequality at all.

I understand why technology would mean decoupling happens fastest during the highest productivity growth. But I’m not sure I understand what they mean when they say there is no decoupling and productivity growth translates into wage growth? Shouldn’t this disprove all posited causes of decoupling so far, including policy-based wage inequality? I’m not sure. S&S don’t seem to think so, but I’m not sure why. Overall I find this paper confusing, but I assume its authors know what they’re doing so I will accept its conclusions as presented.

So it sounds like, although technology probably explains some top-10% people doing moderately better than the rest, it doesn’t explain the stratospheric increase in the share of the 1%, which is where most of the story lies. I would be content to dismiss this as unimportant, except that…

…all the world’s leading economists disagree.

Maybe when they say “income inequality”, they’re talking about a more intuitive view of income inequality where some programmers make $150K and some factory workers make $30K and this is unequal and that’s important – even though it is not related to the larger problem of why everybody except the top 1% is making much less than predicted. I’m not sure.

I feel bad about dismissing so many things as “probably responsible for a few percent of the problem”. It seems like a cop-out when it’s hard to decide whether something is really important or not. But my best guess is still that this is probably responsible for a few percent of the problem.

8. Is Wage Inequality Increasing Because Of Policy Changes?

Hello! We are every think tank in the world! We hear you are wondering whether wage inequality is increasing because of policy changes! Can we offer you nine billion articles proving that it definitely is, and you should definitely be very angry? Please can we offer you articles? Pleeeeeeeeaaase?!

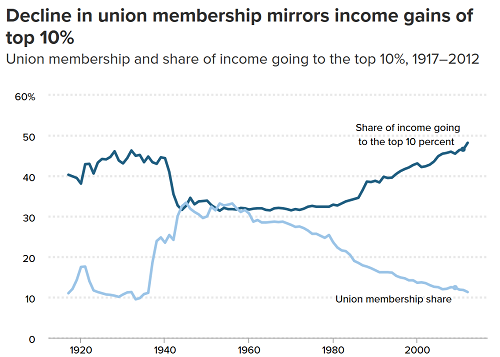

Presentations of this theory usually involve some combination of policies – decreasing union power, low minimum wages, greater acceptance of very high CEO salary – that concentrate all gains in the highest-paid workers, usually CEOs and executives.

I have trouble making the numbers add up. Vox has a cute thought experiment here where they imagine the CEO of Wal-Mart redistributing his entire salary to all Wal-Mart workers equally, possibly after having been visited by three spirits. Each Wal-Mart employee would make an extra $10. If the spirits visited all top Wal-Mart executives instead of just the CEO, the average employee would get $30. This is obviously not going to single-handedly bring them to the middle-class.

Vox uses such a limited definition of “top executive” that only five people are included. What about Wal-Mart’s 1%?

The Wal-Mart 1% will include 20,000 people. To reach the 1% in the US, you need to make $400,000 per year; I would expect Wal-Mart’s 1% to be lower, since Wal-Mart is famously a bad place to work that doesn’t pay people much. Let’s say $200,000. That means the Wal-Mart 1% makes a total of $4 billion. If their salary were distributed to all 2 million employees, those employees would make an extra $2,000 per year; maybe a 10% pay raise. And of course even in a perfectly functional economy, we couldn’t pay Wal-Mart management literally $0, so the real number would be less than this.

Maybe the problem is that Wal-Mart is just an unusually employee-heavy company. What about Apple? Their CEO makes $12 million per year. If that were distributed to their 132,000 employees, they would each make an extra $90.

How many total high-paid executives does Apple have? It looks like Apple hires up to 130 MBAs from top business schools per year; if we imagine they last 10 years each, they might have 1000 such people, making them a “top 1%”. If these people get paid $500,000 each, they could earn 500 million total. That’s enough to redistribute $4,000 to all Apple employees, which still isn’t satisfying given the extent of the problem.

Some commenters bring up the possibility that I’m missing stocks and stock options, which make up most of the compensation of top executives. I’m not sure whether this gets classified as income (in which case it could help explain income inequality) or as capital (in which case it would get filed under labor-vs-capital inequality). I’m also not sure whether Apple giving Tim Cook lots of stocks takes money out of the salary budget that could have gone to workers instead. For now let’s just accept that the difference between mean and median income shows that something has to be happening to drive up the top 1% or so of salaries.

What policies are most likely to have caused this concentration of salaries at the top?

Many people point to a decline in unions. This decline does not really line up with the relevant time period – it started in the early 1960s, when productivity and wages were still closely coupled. But it could be a possible contributor. Economics Policy Institute cites some work saying it may explain up to 10% of decoupling even for non-union members, since the deals struck by unions set norms that spread throughout their industries. A group of respected economists including David Card looks into the issue and finds similar results, saying that the decline of unions may explain about 14% or more of increasing wage inequality (remember that wage inequality is only about 40% of decoupling, so this would mean it only explains about 5% of decoupling). The conservative Heritage Foundation has many bad things to say about unions but grudgingly admits they may raise salaries by up to 10% among members (they don’t address non-members). Based on all this, it seems plausible that deunionization may explain about 5-10% of decoupling.

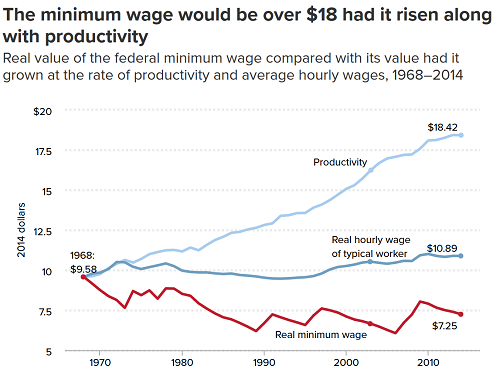

Another relevant policy that could be shaping this issue is the minimum wage. EPI notes that although the minimum wage never goes down in nominal terms, if it doesn’t go up then it’s effectively going down in real terms and relative to productivity. This certainly sounds like the sort of thing that could increase wage inequality.

But let’s look at that graph by percentiles again:

Wage stagnation is barely any better for the 90th percentile worker than it is for the people at the bottom. And the 90th percentile worker isn’t making minimum wage. This may be another one that adds a percentage point here and there, but it doesn’t seem too important.

I can’t find anything about it on EPI, but Thomas Piketty thinks that tax changes were an important driver of wage inequality. I’ll quote my previous review of his book:

He thinks that executive salaries have increased because – basically – corporate governance isn’t good enough to prevent executives from giving themselves very high salaries. Why didn’t executives give themselves such high salaries before? Because before the 1980s the US had a top tax rate of 80% to 90%. As theory predicts, people become less interested in making money when the government’s going to take 90% of it, so executives didn’t bother pulling the strings it would take to have stratospheric salaries. Once the top tax rate was decreased, it became worth executives’ time to figure out how to game the system, so they did. This is less common outside the Anglosphere because other countries have different forms of corporate governance and taxation that discourage this kind of thing.

Piketty does some work to show that increasing wage inequality in different countries is correlated with those countries’ corporate governance and taxation policies. I don’t know if anyone has checked how that affects wage decoupling.

9. Conclusions

1. Contrary to the usual story, wages have not stagnated since 1973. Measurement issues, including wages vs. benefits and different inflation measurements, have made things look worse than they are. Depending on how you prefer to think about inflation, median wages have probably risen about 40% – 50% since 1973, about half as much as productivity.

2. This leaves about a 50% real decoupling between median wages and productivity, which is still enough to be serious and scary. The most important factor here is probably increasing wage inequality. Increasing labor-capital inequality is a less important but still significant factor, and it has become more significant since 2000.

3. Increasing wage inequality probably has a lot to do with issues of taxation and corporate governance, and to some degree also with issues surrounding unionization. It probably has less to do with increasing technology and automation.

4. If you were to put a gun to my head and force me to break down the importance of various factors in contributing to wage decoupling, it would look something like (warning: very low confidence!) this:

– Inflation miscalculations: 35%

– Wages vs. total compensation: 10%

– Increasing labor vs. capital inequality: 15%

—- (Because of automation: 7.5%)

—- (Because of policy: 7.5%)

– Increasing wage inequality: 40%

—- (Because of deunionization: 10%)

—- (Because of policies permitting high executive salaries: 20%)

—- (Because of globalization and automation: 10%)

This surprises me, because the dramatic shift in 1973 made me expect to see a single cause (and multifactorial trends should be rare in general, maybe, I think). It looks like there are two reasons why 1973 seems more important than it is.

First, most graphs trying to present this data begin around 1950. If they had begun much earlier than 1950, they would have showed several historical decouplings and recouplings that make a decoupling in any one year seem less interesting.

Second, 1973 was the year of the 1973 Oil Crisis, the fall of Bretton Woods, and the end of the gold standard, causing a general discombobulation to the economy that lasted a couple of years. By the time the economy recombobulated itself again, a lot of trends had the chance to get going or switch direction. For example, here’s inflation:

5. Inflation issues and wage inequality were probably most important in the first half of the period being studied. Labor-vs-capital inequality was probably most important in the second half.

6. Continuing issues that confuse me:

– How much should we care about the difference between inflation indices? If we agree that using CPI to calculate this is dumb, should we cut our mental picture of the size of the problem in half?

– Why is there such a difference between the Heritage Foundation’s estimate of how much of the gap inconsistent deflators explain (67%) and the EPI’s (34%)? Who is right?

– Does the Summers & Stansbury paper argue against policy-based wage inequality as a cause of median wage stagnation, at least until 2000?

– Are there enough high-paid executives at companies that, if their money were redistributed to all employees, their compensation would have increased significantly more in step with productivity? If so, where are they hiding? If not, what does “increasing wage inequality explains X% of decoupling” mean?

– What caused past episodes of wage decoupling in the US? What ended them?

– How do we square the apparent multifactorial nature of wage decoupling with its sudden beginning in 1973 and with the general argument against multifactorial trends?

Hi Scott

this is Anna Stansbury, one of the authors of the Stansbury-Summers paper you discuss in the article. Glad to see you diving into this debate.

I think it would be helpful for your readers to clarify a few things:

In the debates about decoupling, there are really three different debates happening, and often at cross purposes.

(1) WHICH WORKERS ARE WE INTERESTED IN?

The first debate is: WHOSE pay should we be comparing with productivity? This is ultimately a normative question. It doesn’t depend on theory, and there isn’t a right/wrong answer. Rather, the right choice of workers to look at depends on the question being asked.

Some authors look at the average pay of ALL workers in the economy. They are asking: “on average, has workers’ pay grown less than productivity?” This question is the *exact* analog of asking: “has the share of income going to workers (the labor share) declined”? Mechanically, if the labor share declines, average pay grows more slowly than productivity.

Some authors want to look at workers who are more representative of the typical worker, using either median pay or the pay of production and non-supervisory employees. They are asking: “has the pay of typical workers grown less than average productivity?”. This is a fundamentally different question.

Note that mechanically, rising labor income inequality means that the pay of typical workers has grown by less than the average pay of all workers … so even if average pay has kept up with productivity, if labor income inequality has risen, typical pay won’t have kept up with productivity. Therefore as you note in a late section of your piece, and as the EPI has clearly explained, the divergence between productivity and the pay of typical workers is a result – mechanically – of two phenomena: a falling labor income share, and rising labor income inequality.

Throughout your piece, you cite work interchangeably that actually is asking different questions – some of them are asking about typical workers (median or production/nonsupervisory), and some of them are asking about average pay. Feldstein, Lawrence, Winship and Sherk, for example, look at average pay. The EPI focuses on typical workers, who they define as production/nonsupervisory workers, or as the median worker. This is a large part of why they achieve “different results” – they’re simply asking different questions.

(2) MEASUREMENT CHOICES

The second debate happening to do with decoupling is: given our choice on whose pay to compare with productivity, what are the correct measurement choices? This is where choices about depreciation, inflation, health benefits etc come in. In this case there are some right/wrong answers. For example, it seems clearly right to compare *total compensation* including health benefits, and not just wages. All authors in the debate in recent years use total compensation, not just wages. It also seems correct to use productivity growth net of depreciation, since “you can’t eat depreciation” as Dean Baker said. Once again all authors in the debate in recent years use net productivity, not gross productivity. In other cases it’s more complex – the correct choice of inflation measure isn’t necessarily obvious between CPI, PCE and a producer price deflator, and it partly depends on what question you’re asking and whether you think the divergence between the different inflation measures reflects real phenomena as experienced by people, or is simply a statistical artefact.

These measurement choices definitely, as you note in your post, make a difference to the conclusions. Particularly, with sensible measurement adjustments, it looks like *average* compensation has not diverged much at all from productivity and if it has, it has only done so since the early 2000s (as noted, this is exactly analogous to saying that the labor share has not fallen much and if it has, it has only fallen since the early 2000s).

However, regardless of the measurement adjustments you choose to make, it is incontrovertibly true that the pay of *typical* workers has diverged substantially from productivity since about 1973 (as noted, this is the result of labor income inequality having risen substantially since about 1973).

This is the point Larry Summers and I make in our paper, which you quote with confusion: “If I intepret this correctly, it looks like it’s saying that the real decoupling happened in 2000, not in 1973…Nevertheless, Summers and Stansbury go on to give basically exactly the same “Why have wages been basically stagnant since 1973? Why are they decoupled from productivity?”. In the first part of your quote, we are talking about *average* compensation having diverged from productivity since 2000. In the second part of your quote, we are talking about and *typical* compensation having diverged from productivity since 1973 (measured either as median compensation or average production/nonsupervisory compensation).

Figure 2 on page 9 of our paper provides a clear breakdown of the productivity-compensation divergence under different measurement assumptions and when looking at different workers (average versus median). Hopefully this clears up the confusion.

https://piie.com/system/files/documents/wp18-5.pdf

(3) DIVERGENCE IN LEVELS VERSUS DELINKAGE IN GROWTH RATES

Larry Summers and I ask in our paper “If productivity growth increases, to what extent does it increase the pay of typical workers?” Note that we are *not* asking the question: “has pay really diverged from productivity”? It is very clear that in levels, the pay of median workers and the pay of production/nonsupervisory workers has diverged substantially from productivity. No-one disputes this (though they dispute the magnitude). As far as I know, our paper is the only paper on this topic addressing this question, rather than questions (1) or (2) above.

Why is our question a different question from whether the levels have diverged? There could be different reasons why productivity and pay diverged. On one extreme is what we call delinkage: something may be blocking the transmission mechanism so that higher productivity growth doesn’t translate systematically into higher pay growth. But just as two time series growing together doesn’t mean that one causes the other, two series diverging may not mean that the causal link between the two has broken down. Other factors may have come into play which appear to have severed the connection between productivity growth and pay growth. So on the other extreme is what we call linkage: higher productivity growth still translates into higher pay growth, but at the same time, other factors are pulling down pay even as productivity seeks to raise it.

A good analogy: think of typical workers’ pay as the level of water in a bucket. A tap is supposed to fill the bucket (tap = productivity growth). Over the last forty years, the tap has been running but the level of water has barely risen. You are trying to figure out why. Perhaps there is a blockage in the tap, so despite the tap being on, very little water has come out of it into the bucket. Or perhaps the water from the tap has been flowing into the bucket but at the same time there’s a hole in the bucket and water has been leaking out. If the first view is correct, the most urgent issue is to unblock the tap. There’s no point trying to turn up the water pressure because the water won’t be able to flow past the blockage. But if the second view is correct, then if you turn up the water pressure the level of water in the bucket will rise even if the hole doesn’t get fixed — though it’s clearly best ALSO to fix the hole. So we are trying to answer the question: is the tap blocked?

We find that despite the divergence in levels between productivity and typical workers’ pay, a higher productivity growth rate likely still increases typical workers’ pay growth. A one percentage point higher productivity growth rate is associated with 0.7-1 percentage point higher median pay growth for example. This implies that:

(1) higher productivity growth in the future can be expected to substantially benefit typical workers, and so policy to raise productivity growth can help typical workers

(2) if productivity growth had been even lower over the last decades, typical workers would have done even worse – in fact, their pay might even have fallen in real terms

(3) other factors *orthogonal* to productivity growth must have been pulling down typical workers’ pay even as productivity growth was acting to raise their pay. We don’t discuss these other factors much in the piece because we don’t have evidence on them, but you can think of candidates as being the other factors people invoke when arguing about inequality – things like declines of unions and labor bargaining power, rise of globalization, etc.

Note that are findings are *not* contrary to the arguments about decoupling made by others, including the EPI authors. We are not arguing “that wages and productivity are not decoupled” in the sense in which you are discussing decoupling this blog. It is perfectly possible for productivity and wages to have diverged in levels but for their growth rates still to be linked. In fact, we avoid the term “decoupling” throughout our paper precisely because we find it to be a term that often increases confusion since different researchers use it to mean lots of different things!

I’d be pleased to write a guest post/reply in this vein on your blog. I’m really glad you’ve dug into this issue, and it’s great to expose more readers to it; it would be great to clear up some of the confusion and issues raised.

Best

Anna

The reality is that the whole thing is pretty obviously a result of poor inflationary calculations.

When we consider people’s actual standard of living, this is pretty obvious.

The median new house today is about 900 square feet larger (which is more than 50% larger) than houses were about 50 years ago, at the start of the 1970s.

Houses today are of much higher quality – we have AC (most homes back then did not) and central heating. The building materials are of superior quality – we have better insulation, better windows, better carpet, and better flooring.

We don’t use toxic materials like lead paint and asbsetos anymore.

The stuff we have inside our homes is also of much higher quality and value. Furniture has gotten better over time, but the real thing that has gotten better is our technological appliances – we have microwaves now. We have better refrigerators and freezers. Basically everything in the kitchen that runs on electricity has gotten better over time. Stoves are better, as are ovens. Dishwashers, clothes washers, and driers have all improved and become more prevalent. TVs are vastly better, are larger, and homes have twice as many of them on average.

Cars are vastly better as well, and get both better mileage and have greatly superior creature comforts, without dumping lead into the atmosphere to do it.

And we have many, many things that we simply did not have previously – personal computers, cell phones, smart phones, the Internet, VHS/DVD/Blu-Ray players.

The quality of health care has also grown considerably, as has the quality of mental health care. And food quality is also good, and we’re eating more of it, which is resulting in Americans becoming quite fat.

Moreover, we’ve greatly cut down on pollution – air quality and water quality have gone up while things like acid rain are much less of an issue. These are extrinsic costs borne by us – we pay more money for, say, electricity from coal now because we made them spend a lot of money to not pollute as much, and all our cars have catalytic converters in them to make them much cleaner in the ways that poison humans but less fuel efficient.

To put it bluntly – people are much richer than they were previously. The fact that new houses are more than 50% larger and have much better stuff inside of them would suggest to me that wages have roughly doubled over the last 50ish years.

But even that may be understating it.

Imagine a new 1970 house, with everything in it, versus a new 2020 house, with everything in it. Imagine that the 1970 house was, magically, a brand new 1970 house, not an aged one, but it was straight out of 1970 all the way through.

How much more would the 2020 house be worth relative to the 1970 house?

I think it would be well more than double.

People are far better off today than they were back then.

There’s three other issues:

1) Devaluation. I think you overlooked this in the Heritage Foundation article, but it is actually a hugely important thing that is easy to overlook. Devaluation has gone up considerably because of computers. My parents have a 40 year old cusinart. A 40 year old computer is basically a holy relic at this point, and almost completely useless for almost all tasks and programs. Computers are everywhere and from the 1990s to the 2010s we’ve had to replace them probably every 3-5 years or so.

The thing about capital goods is that you basically pay for them once and they make you money for a good long while, but with computers, you pay for them on a regular basis, over and over again, because you have to replace them to keep up. It is only in the last few years that this has slowed so that a six year old computer is only somewhat obsolete instead of a nice heavy paperweight; using a 1994 computer in 2000 was a nightmare, but using a 2013 computer in 2019 is very doable.

But this would explain the “later” wage decoupling – productivity “went up” but a lot of that went into replacing capital goods on a more regular basis. As the saying goes, you can’t eat depreciation. If your company has to spend $2000 more a year now buying electronic equipment for you to use, that means that you’d have to make $2000 more a year in value just to break even wage-wise. This would be a very significant dampener on wages, and in many companies, the cost has probably actually gone up by more than $2000/year.

2) Misattribution of productivity increases from the Third World. Basically: we import more stuff from China and Mexico and often assemble it into more expensive stuff here. People there work for a lot less than they do here. Productivity is basically a measure of value added. If you aren’t careful in how you calculate your productivity (and there’s a number of people who suggest that we’re not), this would look like increased productivity but it wouldn’t actually be increased productivity *here* but *there*, as a good chunk of the growth would actually be “China and Mexico are better at making stuff than they used to be, resulting in more efficient production.” Or, of course, it just being cheaper to employ people there. Obviously, we would not capture this as gains, but China/Mexico might. Both countries are obviously much richer than they were in 1970.

3) Uneven distribution of productivity increases. People who cut your hair haven’t gotten much more efficient at it. People who sequence DNA have gotten *wildly* more efficient at it. If one industry is ten thousand times more efficient and another industry is not at all more efficient, that averages out to an enormous “productivity increase”, but in real life, most industries saw very little improvement. There’s actually a lot of evidence for this; high tech has seen most of the high productivity gains in recent years.

—

But I think all of this is missing the forest for the trees: the entire premise is wrong.

Inflation and productivity increases are actually arbitrary bullshit.

The cost per teraflop in 2017 dollars in 1961 was $156.8 trillion.

The cost per teraflop in 2017 dollars in 2017 was $30.

That’s a productivity increase of 5.2 trillion times.

So the answer, clearly, is that every one of us is actually a multitrillionaire by the standards of the 1960s many times over.

Pretty much everything else that humans have been doing (except improvements in DNA sequencing, which was a direct result of this anyway) completely pales in comparison to this, so it overwhelms… oh, every other factor combined.

The problem is that this is a completely insane answer so we simply pretend that it isn’t the case. But why not? We talk about how much more bread costs today, or a gallon of milk or gas, why not a teraflop?

But this puts into stark relief the fact that we are fundamentally arbitrarily deciding that some things “count” and others don’t.

When we figured out how to make aluminum cheaply, it went from a metal roughly as valuable as silver to something we make cans out of.

That sort of thing just *happens* sometimes, and all of our calculations pretty much have to pretend like it isn’t really a thing because otherwise these advancements outweigh everything else.

But they are clearly quite massive improvements in productivity, so this is basically just a way of saying “Things aren’t really getting better that fast!”

And while that’s a valid argument with aluminum, which mostly just replaced other metals we were using, computers basically let us put the sum knowledge of humanity into our pocket.

Maybe our smart phones really are worth the equivalent of hundreds of trillions of dollars and we just pretend like they’re not because it’s just insane to think about it that way.

But really, I think that the whole thing is pretty much bunk. Acting like these numbers actually have any meaning is probably just flat-out wrong as the numbers themselves are probably without any real meaning due to all the ad hoc adjustments we have to make to make them not result in things like smart phones with the same value as the entire planet in 1961.

@thetitaniumdragon

Where?

Maybe worldwide but my own eyes tell a very different story.

The Berkeley, California house my parents bought in 1972, while working intermittently as haulers and roofers (mostly my Dad but sometimes my Mom would pitch in), when my Dad was in his early 30’s and my Mom in her mid 20″s. When me and my wife bought a house it was in 2011 after a financial collapse caused a short dip in skyrocketing housing prices when we in our mid to late 40’s, and none of my peers growing up here stayed in town and bought a house, with almost all of them having a lower standard of living than their parents and often grandparents had at the same age.

Those I know who have better living standards than their parents?

Immigrants – all of them, not those born here.

The house me and my wife bought was and the buildings I repair are still filled with lead and asbestos, I have to regularly replace the filters for my respirator and make sure that I change clothes before coming home so I don’t spread lead to my son’s – it’s a very rare week that I don’t encounter lead and asbestos.

And the new homes?

I see a few old houses being mostly torn down (but not completely in order to retain the old property tax rate) and rebuilt bigger, but I see far more being subdivided, and what new housing there is is overwhelmingly small cramped condos and apartments – filled with people leaving the suburbs or from across the border and overseas in search of jobs. More than a decade ago there were new single family homes built far in-land, until gasoline prices spiked in 2007, and people couldn’t afford to drive to work anymore from those far locations with in places with Hellish summer weather, freezing winter weather and few jobs.

Lots of big houses standing empty with places that people actually live in being more cramped isn’t a rise in living standards!

Pull the other one it has bells on it!

Oven and stoves with pilot lights from the ’50’s are sold for a premium because they don’t break down anywhere near as often as these damn electric igniter ones!

Yes copper pipes last longer than steel ones, but nothing lasts as long as the “red brass” pipes and fittings from the ’50’s!

The old 1920’s steam heating systems were much more comfortable than the new forced air crap!

I work very hard to jury-rig the old 1960’s brass and bronze plumbing fixture valves (despite replacement parts becoming scarcer or impossible for me to find) because they can go longer without repair or replacement than the new plastic crap!

And clothes?

My wife searches Goodwill and the Salvation Army for old clothes ’cause the new stuff has shallow pockets and is far thinner and less durable, the boots I wear are mostly decades old that I pay to repair because the good durable U.S. made ones may only be mail ordered for a much higher premium than used to be the case, while the stores are filled with shoddy overseas made replacements that cobblers say can’t be repaired when they soon wear out!

Show me one that isn’t a tiny condo!

Who the Hell knows? Land prices are so high relative to wages now and whatever is standing on it is a tiny fraction of the price!

The house me and my wife got waa smaller and older than my parents house, though I suppose it could be argued that the refrigerator is fancier, and some of the pipes were copper instead of steel, but the water heater and furnace really were even older versions of their 1970’s equivalents so I don’t buy any stories about stuff being “updated”, it simply took decades more labor hours to get a smaller older version of what my parents had in ’72.

A bigger chunk of my wages goes to pay for health insurance than in years past and if my son’s are privileged to get to go to college like their mother did it will cost much more, especially more than the free college education my mother had in the late 1960’s and early ’70’s.

And as far as I can tell those younger than me have to pay an even higher percentage of their earnings towards rent than I did at their age in the ’80’s and ’90’s.

This sure feels like declining living standards to me!

Oh by the way, my wife’s 2004 Toyota Prius seems pretty nice, the breaks work really good, but the 1976 Toyota Corolla I drove until 2001, and the 1984 Toyota Camry I drove till 2005 both got better gas mileage.

The smartphone are neat though, I’ll grant you that.

Thanks for the great post.

I’ve only very quickly skimmed the comments.

It’s important to look at total cost of labor, not just ‘compensation.’ I’m not sure if ‘total cost of labor’ is the same as the formal metric of ‘labor costs.’ Increasing payroll taxes in the US would explain some of the decoupling as the incidence of payroll taxes falls almost completely on employee salaries.

see; https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/7/7b/Payroll_tax_history.jpg/800px-Payroll_tax_history.jpg

The entrance of China into the global market is never discussed, and it’s rather the elephant in the room. Its labor costs seem to have plummeted since 2012. I’m not sure what happened before then.

https://tradingeconomics.com/china/labour-costs

“Why is there such a difference between the Heritage Foundation’s estimate of how much of the gap inconsistent deflators explain (67%) and the EPI’s (34%)? Who is right?”

Heritage’s graph includes managerial income, I believe.

1973 increase of labor supply (women, expats)

2001 China accession to WTO plus acceleration of expat uptake

I think the argument being made in the OECD paper that confused you was that “skilled workers/’winners’ getting a bigger slice of the pie” *wasn’t*, in fact, sufficient to explain the data; rather, *even among skilled workers*, whoever did the job “best” — the “winner” — got most of the wages. Thus the 0.1% effect: it’s not enough to be a skilled programmer or whatever, you have to happen to be the *best* programmer. Winner-takes-most.

Nice work and comprehensive research. Thank you. My modest, simple thinking: if productivity is measured by production (stuff, things, or revenue) per worker, why would it have a direct relationship with wages (pay per person). Nothing is handmade. Coupling makes no sense, since the start. People think pay is proportional to value, and I hear people saying teachers should be better paid because of their contribution/value to society. This sense of value and pay is not real. Wages, or salaries, are a consequence of demand and offer. If we had fewer people available to work as teachers, the pay would be higher. Why are doctors so well paid? Because the offer is short. Since 70’s we introduced computers, in the 80’s downsizing, in the 90’s ERP, in 2000 the cloud. More technology has reduced the need for workers and wages go down (unemployment going up is global, the offer is up).

That’s all good up until the conclusion, which sounds very confused to me. You quoted a lot of people debunking the claim, but you never stepped back to ask what the claim even means. It’s a complicated claim, so there are different ways to debunk it. Some of them are almost opposite. In particular, some ways of debunking it are just as “scary” as the original claim.

What scares you? Inequality? Then debunking the claim by saying that rising inequality is really due to healthcare (compensation) and housing (CPI/PPI) is not debunking that claim at all.

Rising wage inequality is an effect, not a cause. What would it mean for it to cause decoupling?

If the CEO sucks all the money out of the company, and the company sucks it out of the employee, then company has a bad bargaining position with respect to the CEO, but it is still true that the employee has a bad bargaining position with respect to the company, that it is keeping more of his producitivity. Indeed, the cliche is that the CEO is paid the big bucks to reorganize and extract more from the workers.

I know nothing about economics, but maybe the effect is really not as multifactor as it seems. Apart from some measurement issues, it all might be a result of the decline of the relative economic strength of skilled factory workers (basically, because of automation) that simply caused the “decoupling” through various channels (decline of unionization, easier globalization, smaller taxation of high incomes, acceptability of ultra rich, etc.)

You cannot ignore the coincidence with the closing of the gold window. Breton Woods obviously constrained monetary policy, or the US would not have abandoned it. While there is no obvious direct link between a gold standard and the coupling between productivity and wages, there is absolutely a link between a gold standard and monetary policy, in particular the interest rate the central bank is able to maintain.

One could argue that, since Nixon’s closing of the gold window, and outside a few short periods, in particular the Volcker Shock, interest rates in the US have been held below some “natural rate” of interest. Perhaps just the pressure of draining gold reserves caused the Fed to keep interest rates higher than they might have, which would have maintained the cost of capital relative to labor (since interest rates directly add to the cost of capital). Once that pressure was gone, the Fed had one fewer things to worry about, so they started using monetary policy more aggressively to try to “fine tune” the economy. At that point, central banks around the world began competitively devaluing their currencies, at least intermittently.

It wouldn’t be enough just to reduce the cost of capital relative to labor, because otherwise a “fair” proportion of those gains should have gone right back to labor. Which means the change in ratio would have had to cause capital to become more powerful relative to labor as well. Which is exactly what we’ve seen with the decline of labor unions. And because a lower interest rate also means a lower risk-free rate of return, money that might have gone to dividends and salaries has instead been reinvested in more capital. So we’ve had capital continually growing as a fraction of the economy.

The bright side of all this is that a consistent return of interest rates to whatever that “natural rate” of interest is should over time cause a “re-coupling” of productivity with wages. Of course, it will also trigger a long recession. But I think we’d come out the other end much stronger. This will never be politically tenable, so I think instead things will just continue to get worse and worse until our economic system gets overthrown by another broken economic system, because people will have learned all the wrong lessons from our mistakes.

BW would have eventually constrained monetary policy, but that does not imply that it was already constraining policy. That the US could abandon it fairly easily (for a multinational agreement) implies that it did not constrain policy particularly much.

Perhaps, but this article is about figuring out how much effect various theorized causes could have had on decoupling, not about coming up with ways those causes might not have had an effect.

That being said, it seems unlikely to me that the US would have pulled out of BW just because it would eventually constrain monetary policy. It also seems unlikely that observing the drain on gold reserves that was already happening wasn’t constraining monetary policy. The ensuing inflation is also evidence of easing of monetary policy after the US pulled out of BW.

If gold reserves continued to drain then eventually they hit zero, at which point the US would have to

1. Cancel BW and refuse to redeem dollars for gold or

2. Contract the money supply enough that they could buy gold on the open market at the convertibility rate or less.

Basically the constraints on the MS made sure that the US would bail on BW.

A theory needs supporting evidence more than “hey this happend around the same time you have to consider it!”.

A large chunk of this is just Simpson’s paradox.

These headlines go together:

* Good news! Unemployment is down! Employment is up!

* In simultaneous but unrelated news, productivity is down! Average wages are down! Wage inequality is up! Hurting the working classes!

And these headlines go together:

* Good news! Average wages are up! Productivity is up! Wage inequality is down!

* In simultaneous but unrelated news, employment is down, unemployment is up, disability claims are up, number of people no longer actively seeking work is up.

Productivity and wages are measured per *unit of work*, e.g. per employed worker, per hour or day worked. What’s happening here (or at least a good chunk of it) is that the composition of the workforce is changing as people move in and out of employment.

If the least productive (and lowest paid) workers lose their jobs, average productivity will go up, and average wages will rise, and wage inequality will fall. This happens without anybody getting paid more and without anybody getting better at their job.

If the least productive workers find jobs (after being unemployed), average productivity will go down, and average wages will go down, and wage inequality will rise. This happens without anybody getting worse at their jobs, and nobody is paid less because of this.

To the extent that the periods of decoupling correspond to low or falling unemployment, and the periods of coupling correspond to high or rising unemployment, it’s Simpson’s paradox.

Other things could be happening too, but if you don’t control for unemployment and workforce composition you won’t know.

Edit: Just noticed that this is also @dumky2’s point though he doesn’t use the name “Simpson” or mention unemployment.

Edit 2: In case it’s not really, really obvious, if you care about people’s welfare, unemployment is definitely something you should are about a lot more than whether median wage tracks GDP.

This may be true, but with this effect inequality decreases and the average wage increases when (average) productivity increases. During the apparent decoupling phenomenon the post is about, producivity increased but the median wage didn’t significantly increase, and wage inequality increased.

You might guess that these are true but Scott is pointing to a break in the 1970s and the 70s were a period of high unemployment, not low unemployment.

But I don’t see how Simpson’s paradox could explain the decoupling between productivity and wages. As you note, both productivity and wages are measured per unit of work. That means that low productivity and low paid labor entering or exiting the workforce should push both productivity and wages to the same direction (i.e. entering lowers both and exiting raises both).

Caveat lector: I am not an economist, and I read Scott’s very helpful roundup quickly yesterday, so if he addressed this (it looks like maybe tangentially in Section 7?) and I missed it, sorry. So take this theorizing for what it’s worth.

It seems to me that these datasets actually line up quite well, theoretically speaking, with Scott’s former (also good) article on Cost Disease. What we are looking at is increased production of goods and services, but with less of the productivity boost being captured by the median wage earner. Wouldn’t one valid explanation be that most productivity is actually coming from a relatively small set of people and industries, while more and more workers are in jobs where they are not contributing a lot to productivity? All else being equal, that would result in the median worker being responsible for (and thus compensated for) a smaller percentage of the resulting production, while the smaller subset is more valuable and compensated more highly because their skills are actually useful in production and thus get bid up.

The reason I think this would line up well with Cost Disease is that industries subject to Cost Disease show a pattern of rising costs decoupled from increased productivity. That pattern also, it seems to me, could be explained by low-productivity workers proliferating. If you add lots of low-productivity workers, you will see costs increase substantially, but unless the low-productivity workers have exactly the same distribution of wages as the high-productivity workers (which you wouldn’t expect based on demand), the addition of the lower-productivity folks will stagnate the median wage by sheer numbers.

Economy-wide, this could look both like low-productivity people joining every industry (for example, more lawyers in an engineering firm don’t build more bridges faster, though they may be necessary to function) and also like certain industries showing little productivity gain but growing purely through addition of personnel, while other industries with high per-person productivity produce most productivity growth but with too few people to offset the median (for example, lots more warm bodies in classrooms producing the same basic education, but a lot of productivity coming from a relative few people in tech).

I think you may be underestimating the effects of women’s workforce participation. The increased labor supply had some obvious effects and probably caused much of the initial decoupling. We’re talking about a huge change in labor supply.

As more women got jobs, the labor supply grew. This lowered the equilibrium price of labor. There weren’t immediate pay cuts, because wages are really sticky. Companies and workers hate cutting wages in nominal dollars. Instead companies let wages stay constant and inflation cut wages.

Increased labor allowed people to be employed in less productive jobs. These were jobs that were unprofitable at higher labor prices. As wages adjusted to the new price, they became attractive to companies. Marginal jobs were created, driving incomes down.

This also caused capital’s share of income to rise. All production needs some combination of capital and labor. As the work force increased, the amount of capital did not similarly increase. This caused a relative scarcity of capital, driving up the equilibrium price of capital.

You are correct that it does not explain the changes after 2000, but that seems to be when technological factors really took off.

Labor force participation rate for women rose from ~32% in 1947 to ~43% in 1970, it rose another 11 percentage points between 1970 and 1985. Prime age labor force participation rate also climbed 8 points from 1947 through 1970, a rise matched from ’70 through ’82, which makes it a little unlikely that women entering the workforce caused the major shift in the 70s but not from ’47-’70.

There are confounders here, as overall LFPR only climbed a little during that period due to demographic shifts, however total hours worked climbed as much in % terms from ’47 to ’70 as it did from ’70 to ’90, which shoots a major hole in your theory. If people were being employed in less productive jobs, and were lower payed then you would expect more hours worked, not a very similar increase over similar time frames (and don’t get hung up on the 23 year vs 20 year comparison, there is enough bumpiness in the graph that I can choose start and end dates where the pre ’70 period had higher rates of growth or almost identical rates of growth).

Why start postwar? I am much more interested in 1850-1930 trends than 1945-1960, they are more relevant to today.

Postwar is the easiest to get good data on.

But calling it good data is silly because it obviously starts a a strange baseline.

The data is very good, the conclusions are weak due to small sample size issues.

I’m seeing a rate of 33% in 1950 going to 43% in 1970 to 57% in 1990. Male participation (measuring from the top of the seasonal spikes) went from 88% to 82% to 78%. Assuming male and female populations were equal, this means the workforce was 27% female in 1950, 34% in 1970, and 42% in 1990.

I’m looking at hours worked too. There’s a 40% growth in both time frames. Population grew 34% between 1950 and 1970. Work was slightly outpacing population growth (this is partially because of baby boomers growing up, and I’m using raw census data because working age population doesn’t go back that far with the St. Louis fed). Population increased 22% between 1970 and 1990. This means hours per person increased 4% between 1950 and 1970. It increased 15% between 1970 and 1990.

You say that you’d expect to see hours worked rise if there were lower paid, less productive jobs. Adjusted for population, this is exactly what we do see.

Hours per person isn’t a good metric, most of the population growth in the pre ’70 period was a baby boom, those people didn’t start hitting the workforce until ’63 when babies born in ’45 hit 18 and the influx pretty much kept going into the early 60s meaning the tail end of the boomers hitting the workforce were the college grads in the mid 80s. You want to count hours per working age person.

This is true. As I said, I wasn’t finding that data easily. It’s still better than working with raw hours without population.

It would be if you didn’t know the direction of the demographic shifts, but we do (and I have the advantage of having been through several of these discussions before).

here is one adjustment, though it doesn’t go back before ’77 unfortunately.

This doesn’t explain why labor’s share of the GDP stayed more-or-less the same until 2000, and only wage inequality increased significantly.

I agree, and IMO its because people always mistake in their minds the top earners and equity holders. For most of the time it was elite wage earners that were causing the “decoupling” for the median. They live like capital holders, but earn money differently.

I recent essay in the New York Times titled “

How the Upper Middle Class Is Really Doing” reads in part:Is it more similar to the top 1 percent or the working class?

and it has a chart similar to the one’s our host provided but it starts in 1980 instead of 1973, and it shows the income gains of the top 1% as increasing more than productivity, the bottom 90% as less than productivity, and the “90th to 99th percentile” (the top 10% minus the top 1%, presumably what is meant by “upper middle class”) in income as keeping pace with productivity.

What interests me is that mostly incomes rise and fall in tandem with booms and recessions, but there is one part of the chart that shows that in the early 1980’s the bottom 50%’s incomes were falling, while the top half’s incomes were rising, in no other period do I see such a stark difference.

I’m guessing rising “payroll” taxes and lower income taxes?

Also of note: Apparently in New York Times-speak “Rich” is the top 1% in income, “working class” is 90% of Americans (and includes both “the middle class”, and the “poor”), and “the upper middle class” is 9% of Americans.

Good to know the next time I see those terms.

Thanks for posting this, that article hit on a lot of points that I try (probably unsuccessfully) to hit on when talking about this. That drop in the early 80s is definitely interesting.

Not the end-all be-all, but I think those are at least reasonable definitions. Worth noting top 1% starts somewhere a little south of $500,000 per year.

This also helps explain why “most households will be in the top quintile at some point” isn’t as impressive as it sounds, there isn’t a very large gap between the 60th percentile and the 80th, for instance.

The piece cites Piketty’s work, specifically the graph early on. Some have accused that specific output as being the result of cherry picked data. One critic says

and

And another goes

I have not seen an attempt at a refutation from Piketty against either of these claims (I have seen one to some other charges, as there have been many).

There are some more fundamental measurement changes. The decline in average household size, the shift from C to S corporations, the decline of corporate perks. Even putting aside the issues of inflation and compensation vs. wages, these factors make it very difficult to tease out actual historical levels of wages. I’m not sure a valid comparison can really be made.

Nitpick: $400,000 is the threshold, not the average. I couldn’t find a reliable figure for the average income of the top 1%, I’ve seen figures inluding $700,000 and $1,500,000.