I.

Seeing Like A State is the book G.K. Chesterton would have written if he had gone into economic history instead of literature. Since he didn’t, James Scott had to write it a century later. The wait was worth it.

Scott starts with the story of “scientific forestry” in 18th century Prussia. Enlightenment rationalists noticed that peasants were just cutting down whatever trees happened to grow in the forests, like a chump. They came up with a better idea: clear all the forests and replace them by planting identical copies of Norway spruce (the highest-lumber-yield-per-unit-time tree) in an evenly-spaced rectangular grid. Then you could just walk in with an axe one day and chop down like a zillion trees an hour and have more timber than you could possibly ever want.

This went poorly. The impoverished ecosystem couldn’t support the game animals and medicinal herbs that sustained the surrounding peasant villages, and they suffered an economic collapse. The endless rows of identical trees were a perfect breeding ground for plant diseases and forest fires. And the complex ecological processes that sustained the soil stopped working, so after a generation the Norway spruces grew stunted and malnourished. Yet for some reason, everyone involved got promoted, and “scientific forestry” spread across Europe and the world.

And this pattern repeats with suspicious regularity across history, not just in biological systems but also in social ones.

Natural organically-evolved cities tend to be densely-packed mixtures of dark alleys, tiny shops, and overcrowded streets. Modern scientific rationalists came up with a better idea: an evenly-spaced rectangular grid of identical giant Brutalist apartment buildings separated by wide boulevards, with everything separated into carefully-zoned districts. Yet for some reason, whenever these new rational cities were built, people hated them and did everything they could to move out into more organic suburbs. And again, for some reason the urban planners got promoted, became famous, and spread their destructive techniques around the world.

Ye olde organically-evolved peasant villages tended to be complicated confusions of everybody trying to raise fifty different crops at the same time on awkwardly shaped cramped parcels of land. Modern scientific rationalists came up with a better idea: giant collective mechanized farms growing purpose-bred high-yield crops and arranged in (say it with me) evenly-spaced rectangular grids. Yet for some reason, these giant collective farms had lower yields per acre than the old traditional methods, and wherever they arose famine and mass starvation followed. And again, for some reason governments continued to push the more “modern” methods, whether it was socialist collectives in the USSR, big agricultural corporations in the US, or sprawling banana plantations in the Third World.

Traditional lifestyles of many East African natives were nomadic, involving slash-and-burn agriculture in complicated jungle terrain according to a bewildering variety of ad-hoc rules. Modern scientific rationalists in African governments (both colonial and independent) came up with a better idea – resettlement of the natives into villages, where they could have modern amenities like schools, wells, electricity, and evenly-spaced rectangular grids. Yet for some reason, these villages kept failing: their crops died, their economies collapsed, and their native inhabitants disappeared back into the jungle. And again, for some reason the African governments kept trying to bring the natives back and make them stay, even if they had to blur the lines between villages and concentration camps to make it work.

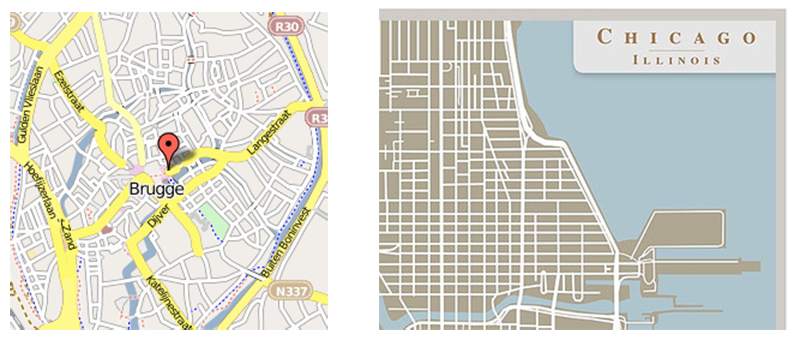

A favorite Seeing Like A State image: a comparison of street maps for Bruges (a premodern organic city) with Chicago (a modern planned city)

Why did all of these schemes fail? And more importantly, why were they celebrated, rewarded, and continued, even when the fact of their failure became too obvious to ignore? Scott gives a two part answer.

The first part of the story is High Modernism, an aesthetic taste masquerading as a scientific philosophy. The High Modernists claimed to be about figuring out the most efficient and high-tech way of doing things, but most of them knew little relevant math or science and were basically just LARPing being rational by placing things in evenly-spaced rectangular grids.

But the High Modernists were pawns in service of a deeper motive: the centralized state wanted the world to be “legible”, ie arranged in a way that made it easy to monitor and control. An intact forest might be more productive than an evenly-spaced rectangular grid of Norway spruce, but it was harder to legislate rules for, or assess taxes on.

The state promoted the High Modernists’ platitudes about The Greater Good as cover, in order to implement the totalitarian schemes they wanted to implement anyway. The resulting experiments were usually failures by the humanitarian goals of the Modernists, but resounding successes by the command-and-control goals of the state. And so we gradually transitioned from systems that were messy but full of fine-tuned hidden order, to ones that were barely-functional but really easy to tax.

II.

Suppose you’re a premodern king, maybe one of the Louises who ruled France in the Middle Ages. You want to tax people to raise money for a Crusade or something. Practically everyone in your kingdom is a peasant, and all the peasants produce is grain, so you’ll tax them in grain. Shouldn’t be too hard, right? You’ll just measure how many pints of grain everyone produces, and…

The pint in eighteenth-century Paris was equivalent to 0.93 liters, whereas in Seine-en-Montane it was 1.99 liters and in Precy-sous-Thil, an astounding 3.33 liters. The aune, a measure of length used for cloth, varied depending on the material(the unit for silk, for instance, was smaller than that for linen) and across France there were at least seventeen different aunes.

Okay, this is stupid. Just give everybody evenly-sized baskets, and tell them that baskets are the new unit of measurement.

Virtually everywhere in early modern Europe were endless micropolitics about how baskets might be adjusted through wear, bulging, tricks of weaving, moisture, the thickness of the rim, and so on. In some areas the local standards for the bushel and other units of measurement were kept in metallic form and placed in the care of a trusted official or else literally carved into the stone of a church or the town hall. Nor did it end there. How the grain was to be poured (from shoulder height, which packed it somewhat, or from waist height?), how damp it could be, whether the container could be shaken down, and finally, if and how it was to be leveled off when full were subjects of long and bitter controversy.

Huh, this medieval king business is harder than you thought. Maybe you can just leave this problem to the feudal lords?

Thus far, this account of local measurement practices risks giving the impression that, although local conceptions of distance, area, volume, and so on were different from and more varied than the unitary abstract standards a state might favor, they were nevertheless aiming at objective accuracy. This impression would be false. […]

A good part of the politics of measurement sprang from what a contemporary economist might call the “stickiness” of feudal rents. Noble and clerical claimants often found it difficult to increase feudal dues directly; the levels set for various charges were the result of long struggle, and even a small increase above the customary level was viewed as a threatening breach of tradition. Adjusting the measure, however, represented a roundabout way of achieving the same end.

The local lord might, for example, lend grain to peasants in smaller baskets and insist on repayment in larger baskets. He might surreptitiously or even boldly enlarge the size of the grain sacks accepted for milling (a monopoly of the domain lord) and reduce the size of the sacks used for measuring out flour; he might also collect feudal dues in larger baskets and pay wages in kind in smaller baskets. While the formal custom governing feudal dues and wages would thus remain intact (requiring, for example, the same number of sacks of wheat from the harvest of a given holding), the actual transaction might increasingly favor the lord. The results of such fiddling were far from trivial. Kula estimates that the size of the bushel (boisseau) used to collect the main feudal rent (taille) increased by one-third between 1674 and 1716 as part of what was called the reaction feodale.

Okay, but nobody’s going to make too big a deal about this, right?

This sense of victimization [over changing units of measure] was evident in the cahiers of grievances prepared for the meeting of the Estates General just before the Revolution. […] In an unprecedented revolutionary context where an entirely new political system was being created from first principles, it was surely no great matter to legislate uniform weights and measures. As the revolutionary decree read “The centuries old dream of the masses of only one just measure has come true! The Revolution has given the people the meter!”

Okay, so apparently (you think to yourself as you are being led to the guillotine), it was a big deal after all.

Maybe you shouldn’t have taxed grain. Maybe you should tax land. After all, it’s the land that grows the grain. Just figure out how much land everybody owns, and you can calculate some kind of appropriate tax from there.

So, uh, peasant villagers, how much land does each of you own?

A hypothetical case of customary land tenure practices may help demonstrate how difficult it is to assimilate such practices to the barebones scheme of a modern cadastral map [land survey suitable for tax assessment][…]

Let us imagine a community in which families have usufruct rights to parcels of cropland during the main growing season. Only certain crops, however, may be planted, and every seven years the usufruct land is distributed among resident families according to each family’s size and its number of able-bodied adults. After the harvest of the main-season crop, all cropland reverts to common land where any family may glean, graze their fowl and livestock, and even plant quickly maturing, dry-season crops. Rights to graze fowl and livestock on pasture-land held in common by the village is extended to all local families, but the number of animals that can be grazed is restricted according to family size, especially in dry years when forage is scarce. Families not using their grazing rights can give them to other villagers but not to outsiders. Everyone has the right to gather firewood for normal family needs, and the village blacksmith and baker are given larger allotments. No commercial sale from village woodlands is permitted.

Trees that have been planted and any fruit they may bear are the property of the family who planted them, no matter where they are now growing. Fruit fallen from such tree, however, is the property of anyone who gathers it. When a family fells one of its trees or a tree is felled by a storm, the trunk belongs to the family, the branches to the immediate neighbors, and the “tops” (leaves and twigs) to any poorer villager who carries them off. Land is set aside for use or leasing out by widows with children and dependents of conscripted males. Usufruct rights to land and trees may be let to anyone in the village; the only time they may be let to someone outside the village is if no one in the community wishes to claim them. After a crop failure leading to a food shortage, many of these arrangements are readjusted.

You know what? I’m just going to put you all down as owning ten. Ten land. Everyone okay with that? Cool. Let’s say ten land for everyone and just move on to the next village.

Novoselok village had a varied economy of cultivation, grazing, and forestry…the complex welter of strips was designed to ensure that each village household received a strip of land in every ecological zone. An individual household might have as many as ten to fifteen different plots constituting something of a representative sample of the village’s ecological zones and microclimates. The distribution spread a family’s risks prudently, and from time to time the land was reshuffled as families grew or shrunk…The strips of land were generally straight and parallel so that a readjustment could be made by moving small stakes along just one side of a field, without having to think of areal dimensions. Where the other side of the field was not parallel, the stakes could be shifted to compensate for the fact that the strip lay toward the narrower or wider end of the field. Irregular fields were divided, not according to area, but according to yield.

…huh. Maybe this isn’t going to work. Let’s try it the other way around. Instead of mapping land, we can just get a list with the name of everyone in the village, and go from there.

Only wealthy aristocrats tended to have fixed surnames…Imagine the dilemma of a tithe or capitation-tax collector [in England] faced with a male population, 90% of whom bore just six Christian names (John, William, Thomas, Robert, Richard, and Henry).

Okay, fine. That won’t work either. Surely there’s something else we can do to assess a tax burden on each estate. Think outside the box, scrape the bottom of the barrel!

The door-and-window tax established in France [in the 18th century] is a striking case in point. Its originator must have reasoned that the number of windows and doors in a dwelling was proportional to the dwelling’s size. Thus a tax assessor need not enter the house or measure it, but merely count the doors and windows.

As a simple, workable formula, it was a brilliant stroke, but it was not without consequences. Peasant dwellings were subsequently designed or renovated with the formula in mind so as to have as few openings as possible. While the fiscal losses could be recouped by raising the tax per opening, the long-term effects on the health of the population lasted for more than a century.

Close enough.

III.

The moral of the story is: premodern states had very limited ability to tax their citizens effectively. Along with the problems mentioned above – nonstandardized measurement, nonstandardized property rights, nonstandardized personal names – we can add a few others. At this point national languages were a cruel fiction; local “dialects” could be as different from one another as eg Spanish is from Portuguese, so villagers might not even be able to understand the tax collectors. Worst of all, there was no such thing as a census in France until the 17th century, so there wasn’t even a good idea of how many people or villages there were.

Kings usually solved this problem by leaving the tax collection up to local lords, who presumably knew the idiosyncracies of their own domains. But one step wasn’t always enough. If the King only knew Dukes, and the Dukes only knew Barons, and the Barons only knew village headmen, and it was only the village headmen who actually knew anything about the peasants, then you needed a four-step chain to get any taxes. Each link in the chain had an incentive to collect as much as they could and give up as little as they could get away with. So on the one end, the peasants were paying backbreaking punitive taxes. And on the other, the Royal Treasurer was handing the King half a loaf of moldy bread and saying “Here you go, Sire, apparently this is all the grain in France.”

So from the beginning, kings had an incentive to make the country “legible” – that is, so organized and well-indexed that it was easy to know everything about everyone and collect/double-check taxes. Also from the beginning, nobles had an incentive to frustrate the kings so that they wouldn’t be out of a job. And commoners, who figured that anything which made it easier for the State to tax them and interfere in their affairs was bad news, usually resisted too.

Scott doesn’t bring this up, but it’s interesting reading this in the context of Biblical history. It would seem that whoever wrote the Bible was not a big fan of censuses. From 1 Chronicles 21:

Satan rose up against Israel and caused David to take a census of the people of Israel. So David said to Joab and the commanders of the army, “Take a census of all the people of Israel—from Beersheba in the south to Dan in the north—and bring me a report so I may know how many there are.”

But Joab replied, “May the Lord increase the number of his people a hundred times over! But why, my lord the king, do you want to do this? Are they not all your servants? Why must you cause Israel to sin?”

But the king insisted that they take the census, so Joab traveled throughout all Israel to count the people. Then he returned to Jerusalem and reported the number of people to David. There were 1,100,000 warriors in all Israel who could handle a sword, and 470,000 in Judah. But Joab did not include the tribes of Levi and Benjamin in the census because he was so distressed at what the king had made him do.

God was very displeased with the census, and he punished Israel for it. Then David said to God, “I have sinned greatly by taking this census. Please forgive my guilt for doing this foolish thing.” Then the Lord spoke to Gad, David’s seer. This was the message: “Go and say to David, ‘This is what the Lord says: I will give you three choices. Choose one of these punishments, and I will inflict it on you.’”

So Gad came to David and said, “These are the choices the Lord has given you. You may choose three years of famine, three months of destruction by the sword of your enemies, or three days of severe plague as the angel of the Lord brings devastation throughout the land of Israel. Decide what answer I should give the Lord who sent me.”

“I’m in a desperate situation!” David replied to Gad. “But let me fall into the hands of the Lord, for his mercy is very great. Do not let me fall into human hands.”

So the Lord sent a plague upon Israel, and 70,000 people died as a result.

(related: Scott examined some of the same data about Holocaust survival rates as Eichmann In Jerusalem, but made them make a lot more sense: the greater the legibility of the state, the worse for the Jews. One reason Jewish survival in the Netherlands was so low was because the Netherlands had a very accurate census of how many Jews there were and where they lived; sometimes officials saved Jews by literally burning census records).

Centralized government projects promoting legibility have always been a two-steps-forward, one-step back sort of thing. The government very gradually expands its reach near the capital where its power is strongest, to peasants whom it knows will try to thwart it as soon as its back is turned, and then if its decrees survive it pushes outward toward the hinterlands.

Scott describes the spread of surnames. Peasants didn’t like permanent surnames. Their own system was quite reasonable for them: John the baker was John Baker, John the blacksmith was John Smith, John who lived under the hill was John Underhill, John who was really short was John Short. The same person might be John Smith and John Underhill in different contexts, where his status as a blacksmith or place of origin was more important.

But the government insisted on giving everyone a single permanent name, unique for the village, and tracking who was in the same family as whom. Resistance was intense:

What evidence we have suggests that second names of any kind became rare as distance from the state’s fiscal reach increased. Whereas one-third of the households in Florence declared a second name, the proportion dropped to one-fifth for secondary towns and to one-tenth in the countryside. It was not until the seventeenth century that family names crystallized in the most remote and poorest areas of Tuscany – the areas that would have had the least contact with officialdom. […]

State naming practices, like state mapping practices, were inevitably associated with taxes (labor, military service, grain, revenue) and hence aroused popular resistance. The great English peasant rising of 1381 (often called the Wat Tyler Rebellion) is attributed to an unprecedented decade of registration and assessments of poll taxes. For English as well as for Tuscan peasants, a census of all adult males could not but appear ominous, if not ruinous.

The same issues repeated themselves a few hundred years later when Europe started colonizing other continents. Again they encountered a population with naming systems they found unclear and unsuitable to taxation. But since colonial states had more control over their subjects than the relatively weak feudal monarchies of the Middle Ages, they were able to deal with it in one fell swoop, sometimes comically so:

Nowhere is this better illustrated than in the Philippines under the Spanish. Filipinos were instructed by the decree of November 21, 1849 to take on permanent Hispanic surnames. […]

Each local official was to be given a supply of surnames sufficient for his jurisdiction, “taking care that the distribution be made by letters of the alphabet.” In practice, each town was given a number of pages from the alphabetized [catalog], producing whole towns with surnames beginning with the same letter. In situations where there has been little in-migration in the past 150 years, the traces of this administrative exercise are still perfectly visible across the landscape. “For example, in the Bikol region, the entire alphabet is laid out like a garland over the provinces of Albay, Sorsogon, and Catanduanes which in 1849 belonged to the single jurisdiction of Albay. Beginning with A at the provincial capital, the letters B and C mark the towns along the cost beyond Tabaco to Wiki. We return and trace along the coast of Sorosgon the letters E to L, then starting down the Iraya Valley at Daraga with M, we stop with S to Polangui and Libon, and finish the alphabet with a quick tour around the island of Catanduas.

The confusion for which the decree is the antidote is largely that of the administrator and the tax collector. Universal last names, they believe, will facilitate the administration of justice, finance, and public order as well as make it simpler for prospective marriage partners to calculate their degree of consanguinity. For a utilitarian state builder of [Governor] Claveria’s temper, however, the ultimate goal was a complete and legible list of subjects and taxpayers.

This was actually a lot less cute and funny than the alphabetization makes it sound:

What if the Filipinos chose to ignore their new last names? This possibility had already crossed Claveria’s mind, and he took steps to make sure that the names would stick. Schoolteachers were ordered to forbid their students to address or even know one another by any name except the officially inscribed family name. Those teachers who did not apply the rule with enthusiasm were to be punished. More efficacious perhaps, given the minuscule school enrollment, was the proviso that forbade priests and military and civil officials from accepting any document, application, petition, or deed that did not use the official surnames. All documents using other names would be null and void

Similar provisions ensured the replacement of local dialects with the approved national language. Students were only allowed to learn the national language in school and were punished for speaking in vernacular. All formal documents had to be in the national language, which meant that peasants who had formally been able to manage their own legal affairs had to rely on national-language-speaking intermediaries. Scott talks about the effect in France:

One can hardly imagine a more effective formula for immediately devaluing local knowledge and privileging all those who had mastered the official linguistic code. It was a gigantic shift in power. Those at the periphery who lacked competence in French were rendered mute and marginal. They were now in need of a local guide to the new state culture, which appeared in the form of lawyers, notaries, schoolteachers, clerks, and soldiers.

IV.

So the early modern period is defined by an uneasy truce between states who want to be able to count and standardize everything, and citizens who don’t want to let them. Enter High Modernism. Scott defines it as

A strong, one might even say muscle-bound, version of the self-confidence about scientific and technical progress, the expansion of production, the growing satisfaction of human needs, the mastery of nature (including human nature), and above all, the rational design of social order commensurate with the scientific understanding of natural laws

…which is just a bit academic-ese for me. An extensional definition might work better: standardization, Henry Ford, the factory as metaphor for the best way to run everything, conquest of nature, New Soviet Man, people with college degrees knowing better than you, wiping away the foolish irrational traditions of the past, Brave New World, everyone living in dormitories and eating exactly 2000 calories of Standardized Food Product (TM) per day, anything that is For Your Own Good, gleaming modernist skyscrapers, The X Of The Future, complaints that the unenlightened masses are resisting The X Of The Future, demands that if the unenlightened masses reject The X Of The Future they must be re-educated For Their Own Good, and (of course) evenly-spaced rectangular grids.

(maybe the best definition would be “everything G. K. Chesterton didn’t like.”)

It sort of sounds like a Young Adult Dystopia, but Scott shocked me with his research into just how strong this ideology was around the turn of the last century. Some of the greatest early 20th-century thinkers were High Modernist to the point of self-parody, the point where a Young Adult Dystopian fiction writer would start worrying they were laying it on a little too thick.

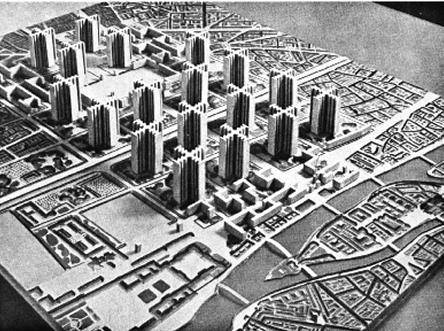

The worst of the worst was Le Corbusier, the French artist/intellectual/architect. The Soviets asked him to come up with a plan to redesign Moscow. He came up with one: kick out everyone, bulldoze the entire city, and redesign it from scratch upon rational principles. For example, instead of using other people’s irrational systems of measurement, they would use a new measurement system invented by Le Corbusier himself, called Modulor, which combined the average height of a Frenchman with the Golden Ratio.

Also, evenly-spaced rectangular grids may have been involved.

The Soviets decided to pass: the plan was too extreme and destructive of existing institutions even for Stalin. Undeterred, Le Corbusier changed the word “Moscow” on the diagram to “Paris”, then presented it to the French government (who also passed). Some aspects of his design eventually ended up as Chandigarh, India.

A typical building in Chandigarh. The Soviets and French must have been kicking themselves when they realized what they’d missed out on.

Le Corbusier was challenged on his obsession with keeping his plan in the face of different local conditions, pre-existing structures, residents who might want a say in the matter, et cetera. Wasn’t it kind of dictatorial? He replied that:

The despot is not a man. It is the Plan. The correct, realistic, exact plan, the one that will provide your solution once the problem has been posited clearly, in its entirety, in its indispensable harmony. This plan has been drawn up well away from the frenzy in the mayor’s office or the town hall, from the cries of the electorate or the laments of society’s victims. It has been drawn up by serene and lucid minds. It has taken account of nothing but human truths. It has ignored all current regulations, all existing usages, and channels. It has not considered whether or not it could be carried out with the constitution now in force. It is a biological creation destined for human beings and capable of realization by modern techniques.

What was so great about this “biological creation” of “serene and lucid minds”? It…might have kind of maybe been evenly-spaced rectangular grids:

People will say: “That’s easily said! But all your intersections are right angles. What about the infinite variations that constitute the reality of our cities?” But that’s precisely the point: I eliminate all these things. Otherwise we shall never get anywhere.

I can already hear the storms of protest and the sarcastic gibes: “Imbecile, madman, idiot, braggart, lunatic, etc.” Thank you very much, but it makes no difference: my starting point is still the same: I insist on right-angled intersections. The intersections shown here are all perfect.

Scott uses Le Corbusier as the epitome of five High Modernist principles.

First, there can be no compromise with the existing infrastructure. It was designed by superstitious people who didn’t have architecture degrees, or at the very least got their architecture degrees in the past and so were insufficiently Modern. The more completely it is bulldozed to make way for the Glorious Future, the better.

Second, human needs can be abstracted and calculated. A human needs X amount of food. A human needs X amount of water. A human needs X amount of light, and prefers to travel at X speed, and wants to live within X miles of the workplace. These needs are easily calculable by experiment, and a good city is the one built to satisfy these needs and ignore any competing frivolities.

Third, the solution is the solution. It is universal. The rational design for Moscow is the same as the rational design for Paris is the same as the rational design for Chandigarh, India. As a corollary, all of these cities ought to look exactly the same. It is maybe permissible to adjust for obstacles like mountains or lakes. But only if you are on too short a budget to follow the rationally correct solution of leveling the mountain and draining the lake to make your city truly optimal.

Fourth, all of the relevant rules should be explicitly determined by technocrats, then followed to the letter by their subordinates. Following these rules is better than trying to use your intuition, in the same way that using the laws of physics to calculate the heat from burning something is better than just trying to guess, or following an evidence-based clinical algorithm is better than just prescribing whatever you feel like.

Fifth, there is nothing whatsoever to be gained or learned from the people involved (eg the city’s future citizens). You are a rational modern scientist with an architecture degree who has already calculated out the precise value for all relevant urban parameters. They are yokels who probably cannot even spell the word architecture, let alone usefully contribute to it. They probably make all of their decisions based on superstition or tradition or something, and their input should be ignored For Their Own Good.

And lest I be unfair to Le Corbusier, a lot of his scientific rational principles made a lot of sense. Have wide roads so that there’s enough room for traffic and all the buildings get a lot of light. Use rectangular grids to make cities easier to navigate. Avoid frivolous decoration so that everything is efficient and affordable to all. Use concrete because it’s the cheapest and strongest material. Keep pedestrians off the streets as much as possible so that they don’t get hit by cars. Use big apartment towers to save space, then use the open space for pretty parks and public squares. Avoid anything that looks like a local touch, because nationalism leads to war and we are all part of the same global community of humanity. It sounded pretty good, and for a few decades the entire urban planning community was convinced.

So, how did it go?

Scott uses the example of Brasilia. Brazil wanted to develop its near-empty central regions and decided to build a new capital in the middle of nowhere. They hired three students of Le Corbusier, most notably Oscar Niemeyer, to build them a perfect scientific rational city. The conditions couldn’t have been better. The land was already pristine, so there was no need to bulldoze Paris first. There were no inconvenient mountains or forests in the way. The available budget was in the tens of billions. The architects rose to the challenge and built them the world’s greatest High Modernist city.

It’s…even more beautiful than I imagined

Yet twenty years after its construction, the city’s capacity of 500,000 residents was only half-full. And it wasn’t the location – a belt of suburbs grew up with a population of almost a million. People wanted to live in the vicinity of Brasilia. They just didn’t want to live in the parts that Niemeyer and the Corbusierites had built.

Brasilia from above. Note both the evenly-spaced rectangular grid of identical buildings in the center, and the fact that most people aren’t living in it.

What happened? Scott writes:

Most of those who have moved to Brasilia from other cities are amazed to discover “that it is a city without crowds.” People complain that Brasilia lacks the bustle of street life, that it has none of the busy street corners and long stretches of storefront facades that animate a sidewalk for pedestrians. For them, it is almost as if the founders of Brasilia, rather than having planned a city, have actually planned to prevent a city. The most common way they put it is to say that Brasilia “lacks street corners,”by which they mean that it lacks the complex intersections of dense neighborhoods comprising residences and public cafes and restaurants with places for leisure, work, and shopping.

While Brasilia provides well for some human needs, the functional separation of work from residence and of both from commerce and entertainment, the great voids between superquadra, and a road system devoted exclusively to motorized traffic make the disappearance of the street corner a foregone conclusion. The plan did eliminate traffic jams; it also eliminated the welcome and familiar pedestrian jams that one of Holston’s informants called “the point of social conviviality

The term brasilite, meaning roughly Brasilia-itis,which was coined by the first-generation residents, nicely captures the trauma they experienced. As a mock clinical condition, it connotes a rejection of the standardization and anonymity of life in Brasilia. “They use the term brasilite to refer to their feelings about a daily life without the pleasures-the distractions, conversations, flirtations, and little rituals of outdoor life in other Brazilian cities.” Meeting someone normally requires seeing them either at their apartment or at work. Even if we allow for the initial simplifying premise of Brasilia’s being an administrative city, there is nonetheless a bland anonymity built into the very structure of the capital. The population simply lacks the small accessible spaces that they could colonize and stamp with the character of their activity, as they have done historically in Rio and Sao Paulo. To be sure, the inhabitants of Brasilia haven’t had much time to modify the city through their practices, but the city is designed to be fairly recalcitrant to their efforts.

“Brasilite,” as a term, also underscores how the built environment affects those who dwell in it. Compared to life in Rio and Sao Paulo, with their color and variety, the daily round in bland, repetitive, austere Brasilia must have resembled life in a sensory deprivation tank. The recipe for high-modernist urban planning, while it may have created formal order and functional segregation, did so at the cost of a sensorily impoverished and monotonous environment-an environment that inevitably took its toll on the spirits of its residents.

The anonymity induced by Brasilia is evident from the scale and exterior of the apartments that typically make up each residential superquadra. For superquadra residents, the two most frequent complaints are the sameness of the apartment blocks and the isolation of the residences (“In Brasilia, there is only house and work”). The facade of each block is strictly geometric and egalitarian. Nothing distinguishes the exterior of one apartment from another; there are not even balconies that would allow residents to add distinctive touches and create semipublic spaces.

Brasilia is interesting only insofar as it was an entire High Modernist planned city. In most places, the Modernists rarely got their hands on entire cities at once. They did build a number of suburbs, neighborhoods, and apartment buildings. There was, however, a disconnect. Most people did not want to buy a High Modernist house or live in a High Modernist neighborhood. Most governments did want to fund High Modernist houses and neighborhoods, because the academics influencing them said it was the modern scientific rational thing to do. So in the end, one of High Modernists’ main contributions to the United States was the projects – ie government-funded public housing for poor people who didn’t get to choose where to live.

I never really “got” Jane Jacobs. I originally interpreted her as arguing that it was great for cities to be noisy and busy and full of crowds, and that we should build neighborhoods that are confusing and hard to get through to force people to interact with each other and prevent them from being able to have privacy, and no one should be allowed to live anywhere quiet or nice. As somebody who (thanks to the public school system, etc) has had my share of being forced to interact with people, and of being placed in situations where it is deliberately difficult to have any privacy or time to myself, I figured Jane Jacobs was just a jerk.

But Scott has kind of made me come around. He rehabilitates her as someone who was responding to the very real excesses of High Modernism. She was the first person who really said “Hey, maybe people like being in cute little neighborhoods”. Her complaint wasn’t really against privacy or order per se as it was against extreme High Modernist perversions of those concepts that people empirically hated. And her background makes this all too understandable – she started out as a journalist covering poor African-Americans who lived in the projects and had some of the same complaints as Brazilians.

Her critique of Le Corbusierism was mostly what you would expect, but Scott extracts some points useful for their contrast with the Modernist points earlier:

First, existing structures are evolved organisms built by people trying to satisfy their social goals. They contain far more wisdom about people’s needs and desires than anybody could formally enumerate. Any attempt at urban planning should try to build on this encoded knowledge, not detract from it.

Second, man does not live by bread alone. People don’t want the right amount of Standardized Food Product, they want social interaction, culture, art, coziness, and a host of other things nobody will ever be able to calculate. Existing structures have already been optimized for these things, and unless you’re really sure you understand all of them, you should be reluctant to disturb them.

Third, solutions are local. Americans want different things than Africans or Indians. One proof of this is that New York looks different from Lagos and from Delhi. Even if you are the world’s best American city planner, you should be very concerned that you have no idea what people in Africa need, and you should be very reluctant to design an African city without extensive consultation of people who understand the local environment.

Fourth, even a very smart and well-intentioned person who is on board with points 1-3 will never be able to produce a set of rules. Most of people’s knowledge is implicit, and most rule codes are quickly replaced by informal systems of things that work which are much more effective (the classic example of this is work-to-rule strikes).

Fifth, although well-educated technocrats may understand principles which give them some advantages in their domain, they are hopeless without the on-the-ground experience of the people they are trying to serve, whose years of living in their environment and dealing with it every day have given them a deep practical knowledge which is difficult to codify.

How did Jacobs herself choose where to live? As per her Wikipedia page:

[Jacobs] took an immediate liking to Manhattan’s Greenwich Village, which did not conform to the city’s grid structure.

V.

The same thing that happened with cities happened with farms. The American version was merely farce:

We should recognize that the rationalization of farming on a huge, even national, scale was part of a faith shared by social engineers and agricultural planners throughout the world. And they

were conscious of being engaged in a common endeavor…They kept in touch through journals, professional conferences, and exhibitions. The connections were strongest between American agronomists and their Russian colleagues – connections that were not entirely broken even during the Cold War. Working in vastly different economic and political environments, the Russians tended to be envious of the level of capitalization, particularly in mechanization, of American farms while the Americans were envious of the political scope of Soviet planning. The degree to which they were working together to create a new world of large-scale, rational, industrial agriculture can be judged by this brief account of their relationship […]Many efforts were made to put this faith to the test. Perhaps the most audacious was the Thomas Campbell “farm” in Montana, begun – or, perhaps I should say, founded – in 1918 It was an industrial farm in more than one respect. Shares were sold by prospectuses describing the enterprise as an “industrial opportunity”; J. P. Morgan, the financier, helped to raise $2 million from the public. The Montana Farming Corporation was a monster wheat farm of ninety-five thousand acres, much of it leased from four Native American tribes. Despite the private investment, the enterprise would never have gotten off the ground without help and subsidies from the Department of Interior and the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA).

Proclaiming that farming was about 90 percent engineering and only 10 percent agriculture, Campbell set about standardizing as much of his operation as possible. He grew wheat and flax, two hardy crops that needed little if any attention between planting and harvest time.The land he farmed was the agricultural equivalent of the bulldozed site of Brasilia. It was virgin soil, with a natural fertility that would eliminate the need for fertilizer. The topography also vastly simplified matters: it was flat, with no forests, creeks, rocks, or ridges that would impede the smooth course of machinery over its surface. In other words, the selection of the simplest, most standardized crops and the leasing of something very close to a blank agricultural space were calculated to favor the application of industrial methods […]

This is not the place to chronicle the fortunes of the Montana Farming Corporation, and in any event Deborah Fitzgerald has done so splendidly. Suffice it to note that a drought in the second year and the elimination of a government support for prices the following year led to a collapse that cost J. P. Morgan $1 million. The Campbell farm faced other problems besides weather and prices: soil differences, labor turnover, the difficulty of finding skilled, resourceful workers who would need little supervision. Although the corporation struggled on until Campbell’s death in 1966,it provided no evidence that industrial farms were superior to family farms in efficiency and profitability.

But the Soviet version was tragedy. Instead of raising some money to start a giant farm and seeing it didn’t work, the USSR uprooted millions of peasants, forced them onto collective farms, and then watched as millions of people starved to death due to crop failure. What happened?

Scott really focuses on that claim (above) that farming was “90% engineering and only 10% agriculture”. He says that these huge farms all failed – despite being better-funded, higher-tech, and having access to the wisdom of the top agricultural scientists – exactly because this claim was false. Small farmers may not know much about agricultural science, but they know a lot about farming. Their knowledge is intuitive and local – for example, what to do in a particular climate or soil. It is sometimes passed down over generations, and other times determined through long hours of trial-and-error.

He gave the example of Tanzania, where small farmers grew dozens of different crops together in seeming chaos. Western colonists tried to convince them – often by force – to switch to just growing one thing at a time to reap advantages of efficiency, standardization, and specialization of labor. Only growing one crop in the same field was Agricultural Science 101. But this turned out to be a bad idea in the difficult Tanzanian environment:

The multistoried effect of polyculture has some distinct advantages for yields and soil conservation. “Upper-story” crops shade “lowerstory” crops, which are selected for their ability to thrive in the cooler soil temperature and increased humidity at ground level. Rainfall reaches the ground not directly but as a fine spray that is absorbed with less damage to soil structure and less erosion. The taller crops often serve as a useful windbreak for the lower crops. Finally, in mixed or relay cropping, a crop is in the field at all times, holding the soil together and reducing the leaching effects that sun, wind, and rain exert, particularly on fragile land. Even if polyculture is not to be preferred on the grounds of immediate yield, there is much to recommend it in terms of sustainability and thus long-term production.

Our discussion of mixed cropping has thus far dealt only with the narrow issues of yield and soil conservation. It has overlooked the cultivators themselves and the various other ends that they seek by using such techniques. The most significant advantage of intercropping, Paul Richards claims, is its great flexibility, “the scope [it] offers for a range of combinations to match individual needs and preferences, local conditions, and changing circumstances within each season and from season to season.” Farmers may polycrop in order to avoid labor bottlenecks at planting and at harvest.44Growing many different crops is also an obvious way to spread risks and improve food security. Cultivators can reduce the danger of going hungry if they sow, instead of only one or two cultivars, crops of long and short maturity, crops that are drought resistant and those that do well under wetter conditions, crops with different patterns of resistance to pests and diseases, crops that can be stored in the ground with little loss (such as cassava), and crops that mature in the “hungry time” before other crops are gathered. Finally, and perhaps most important, each of these crops is embedded in a distinctive set of social relations. Different members of the household are likely to have different rights and responsibilities with

respect to each crop. The planting regimen, in other words, is a reflection of social relations, ritual needs, and culinary tastes; it is not just a production strategy that a profit-maximizing entrepreneur took straight out of the pages of a text in neoclassical economics.

Nor could this be solved just by adding a pinch of empiricism. A lot of European farming specialists were into empiricism, sort of. What they ended up doing was creating crops that worked really well in a lab but not in actual Tanzania. If they were lucky, they created crops that worked really well on the one experimental farm in Tanzania they fenced off as a testing ground, but not on any other Tanzanian farms. If they were really lucky, they created crops that would grow on Tanzanian farms and be good on whatever single axis they were optimizing (like selling for lots of money) but not in other ways that were equally important to the populace (like being low-risk, or useful for non-food purposes, or resistant to disease, or whatever). And if they were supremely lucky, then they would go to the Tanzanians and say “Hey, we invented a new farming method that solves all your problems!” and the Tanzanians would say “Yeah, we heard rumors about that, so we tried it ourselves, and now we’ve been using it for five years and advanced it way beyond what you were doing.”

There were some scientists who got beyond these failure modes, and Scott celebrates them (while all too often describing how they were marginalized and ignored by the rest of the scientific community). But at the point where you’ve transcended all this, you’re no longer a domain-general agricultural scientist, you’re a Tanzanian farming specialist who’s only one white coat removed from being a Tanzanian farmer yourself.

Even in less exotic locales like Russia, the peasant farmers were extraordinary experts on the conditions of their own farms, their own climates, and their own crops. Take all of these people, transport them a thousand miles away, and give them a perfectly rectangular grid to grow Wheat Cultivar #6 on, and you have a recipe for disaster.

VI.

So if this was such a bad idea, why did everyone keep doing it?

Start with the cities. Scott notes that although citizens generally didn’t have a problem with earlier cities, governments did:

Historically, the relative illegibility to outsiders of some urban neighborhoods has provided a vital margin of political safety from control by outside elites. A simple way of determining whether this margin exists is to ask if an outsider would have needed a local guide in order to find her way successfully. If the answer is yes, then the community or terrain in question enjoys at least a small measure of insulation from outside intrusion. Coupled with patterns of local solidarity, this insulation has proven politically valuable in such disparate contexts as eighteenth-and early nineteenth-century urban riots over bread prices in Europe, the Front de Liberation Nationale’s tenacious resistance to the French in the Casbah of Algiers, and the politics of the bazaar that helped to bring down the Shah of Iran. Illegibility, then, has been and remains a reliable resource for political autonomy

This was a particular problem in Paris, which was famous for a series of urban insurrections in the 19th century (think Les Miserables, but about once every ten years or so). Although these generally failed, they were hard to suppress because locals knew the “terrain” and the streets were narrow enough to barricade. Slums full of poor people gathered together formed tight communities where revolutionary ideas could easily spread. The late 19th-century redesign of Paris had the explicit design of destroying these areas and splitting up poor people somewhere far away from the city center where they couldn’t do any harm.

The Soviet collective farms had the same dubious advantage. The problem they “effectively” “solved” was the non-collectivized farmers becoming too powerful and independent a political bloc. They lived in tight-knit little villages that did their own thing, the Party officials who went to these villages to keep order often ended up “going native”, and the Soviets had no way of knowing how much food the farmers were producing and whether they were giving enough of it to the Motherland:

Confronting a tumultuous, footloose, and “headless” rural society which was hard to control and which had few political assets, the Bolsheviks, like the scientific foresters, set about redesigning their environment with a few simple goals in mind. They created, in place of what they had inherited, a new landscape of large, hierarchical, state-managed farms whose cropping patterns and procurement quotas were centrally mandated and whose population was, by law, immobile. The system thus devised served for nearly sixty years as a mechanism for procurement and control at a massive cost in stagnation, waste, demoralization, and ecological failure.

The collectivized farms couldn’t grow much, but people were thrown together in artificial towns designed to make it impossible to build any kind of community: there was nowhere to be except in bed asleep, working in the fields, or at the public school receiving your daily dose of state propaganda. The towns were identical concrete buildings on a grid, which left the locals maximally disoriented (because there are no learnable visual cues) and the officials maximally oriented (because even a foreigner could go to the intersection of Street D and Street 7). All fields were perfectly rectangular and produced Standardized Food Product, so it was (theoretically) easy to calculate how much they should be producing and whether people were meeting that target. And everyone was in the same place, so if there were some sort of problem it was much easier to bring in the army or secret police than if they were split up among a million tiny villages in the middle of nowhere.

So although modernist cities and farms may have started out as attempts to help citizens with living and farming, they ended up as contributors to the great government project of legibility and taxing people effectively.

Seeing Like A State summarizes the sort of on-the-ground ultra-empirical knowledge that citizens have of city design and peasants of farming as metis, a Greek term meaning “practical wisdom”. I was a little concerned about this because they seem like two different things. The average citizen knows nothing about city design and in fact does not design cities; cities sort of happen in a weird way through cultural evolution or whatever. The average farmer knows a lot about farming (even if it is implicit and not as book learning) and applies that knowledge directly in how they farm. But Scott thinks these are more or less the same thing, that this thing is a foundation of successful communities and industries, and that ignoring and suppressing it is what makes collective farms and modernist planned cities so crappy. He generalizes this further to almost every aspect of a society – its language, laws, social norms, and economy. But this is all done very quickly, and I feel like there was a sleight of hand between “each farmer eventually figures out how to farm well” and “social norms converge on good values”.

Insofar as Scott squares the above circle, he seems to think that many actors competing with each other will eventually carve out a beneficial equilibrium better than that of any centralized authority. This doesn’t really mesh will with my own fear that many actors competing with each other will eventually shoot themselves in the foot and destroy everything, and I haven’t really seen a careful investigation of when we get one versus the other.

VII.

What are we to make of all of this?

Well, for one thing, Scott basically admits to stacking the dice against High Modernism and legibility. He admits that the organic livable cities of old had life expectancies in the forties because nobody got any light or fresh air and they were all packed together with no sewers and so everyone just died of cholera. He admits that at some point agricultural productivity multiplied by like a thousand times and the Green Revolution saved millions of lives and all that, and probably that has something to do with scientific farming methods and rectangular grids. He admits that it’s pretty convenient having a unit of measurement that local lords can’t change whenever they feel like it. Even modern timber farms seem pretty successful. After all those admissions, it’s kind of hard to see what’s left of his case.

(also, I grew up in Irvine, the most planned of planned cities, and I loved it.)

What Scott eventually says is that he’s not against legibility and modernism per se, but he wants to present them as ingredients in a cocktail of state failure. You need a combination of four things to get a disaster like Soviet collective farming (or his other favorite example, compulsory village settlement in Tanzania). First, a government incentivized to seek greater legibility for its population and territory. Second, a High Modernist ideology. Third, authoritarianism. And fourth, a “prostrate civil society”, like in Russia after the Revolution, or in colonies after the Europeans took over.

I think his theory is that the back-and-forth between centralized government and civil society allows scientific advances to be implemented smoothly instead of just plowing over everyone in a way that leads to disaster. I also think that maybe a big part of it is incremental versus sudden: western farming did well because it got to incrementally add advances and see how they worked, but when you threw the entire edifice at Tanzania it crashed and burned.

I’m still not really sure what’s left. Authoritarianism is bad? Destroying civil society is bad? You shouldn’t do things when you have no idea what you’re doing and all you’ve got to go on is your rectangle fetish? The book contained some great historical tidbits, but I’m not sure what overarching lesson I learned from it.

It’s not that I don’t think Scott’s preference for metis over scientific omnipotence has value. I think it has lots of value. I see this all the time in psychiatry, which always has been and to some degree still is really High Modernist. We are educated people who know a lot about mental health, dealing with a poor population who (in the case of one of my patients) refers to Haldol as “Hound Dog”. It’s very easy to get in the trap of thinking that you know better than these people, especially since you often do (I will never understand how many people are shocked when I diagnose their sleep disorder as having something to do with them drinking fifteen cups of coffee a day).

But psychiatric patients have a metis of dealing with their individual diseases the same way peasants have a metis of dealing with their individual plots of land. My favorite example of this is doctors who learn their patients are taking marijuana, refuse to keep prescribing them their vitally important drugs unless the patient promises to stop, and then gets surprised when the patients end up decompensating because the marijuana was keeping them together. I’m not saying smoking marijuana is a good thing. I’m saying that for some people it’s a load-bearing piece of their mental edifice. And if you take it away without any replacement they will fall apart. And they have explained this to you a thousand times and you didn’t believe them.

There are so many fricking patients who respond to sedative medications by becoming stimulated, or stimulant medications by becoming sedated, or who become more anxious whenever they do anti-anxiety exercises, or who hallucinate when placed on some super common medication that has never caused hallucinations in anyone else, or who become suicidal if you try to reassure them that things aren’t so bad, or any other completely perverse and ridiculous violation of the natural order that you can think of. And the only redeeming feature of all of this is that the patients themselves know all of this stuff super-well and are usually happy to tell you if you ask.

I can totally imagine going into a psychiatric clinic armed with the Evidence-Based Guidelines the same way Le Corbusier went into Moscow and Paris armed with his Single Rational City Plan and the same way the agricultural scientists went into Tanzania armed with their List Of Things That Definitely Work In Europe. I expect it would have about the same effect for about the same reason.

(including the part where I would get promoted. I’m not too sure what’s going on there, actually.)

So fine, Scott is completely right here. But I’m only bringing this up because it’s something I’ve already thought about. If I didn’t already believe this, I’d be indifferent between applying the narrative of the wise Tanzanian farmers knowing more than their English colonizers, versus the narrative of the dumb yokels who refuse to get vaccines because they might cause autism. Heuristics work until they don’t. Scott provides us with these great historical examples of local knowledge outdoing scientific acumen, but other stories present us with great historical examples of the opposite, and when to apply which heuristic seems really unclear. Even “don’t bulldoze civil society and try to change everything at once” goes astray sometimes; the Meiji Restoration was wildly successful by doing exactly that.

Maybe I’m trying to take this too far by talking about psychiatry and Meiji Restorations. Most of Scott’s good examples involved either agriculture or resettling peasant villages. This is understandable; Scott is a scholar of colonialism in Southeast Asia and there was a lot of agriculture and peasant resettling going on there. But it’s a pretty limited domain. The book amply proves that peasants know an astounding amount about how to deal with local microclimates and grow local varieties of crops and so on, and frankly I am shocked that anyone with an IQ of less than 180 has ever managed to be a peasant farmer, but how does that apply to the sorts of non-agricultural issues we think about more often?

The closest analogy I can think of right now – maybe because it’s on my mind – is this story about check-cashing shops. Professors of social science think these shops are evil because they charge the poor higher rates, so they should be regulated away so that poor people don’t foolishly shoot themselves in the foot by going to them. But on closer inspection, they offer a better deal for the poor than banks do, for complicated reasons that aren’t visible just by comparing the raw numbers. Poor people’s understanding of this seems a lot like the metis that helps them understand local agriculture. And progressives’ desire to shift control to the big banks seems a lot like the High Modernists’ desire to shift everything to a few big farms. Maybe this is a point in favor of something like libertarianism? Maybe especially a “libertarianism of the poor” focusing on things like occupational licensing, not shutting down various services to the poor because they don’t meet rich-people standards, not shutting down various services to the poor because we think they’re “price-gouging”, et cetera?

Maybe instead of concluding that Scott is too focused on peasant villages, we should conclude that he’s focused on confrontations between a well-educated authoritarian overclass and a totally separate poor underclass. Most modern political issues don’t exactly map on to that – even things like taxes where the rich and the poor are on separate sides don’t have a bimodal distribution. But in cases there are literally about rich people trying to dictate to the poorest of the poor how they should live their lives, maybe this becomes more useful.

Actually, one of the best things the book did to me was make me take cliches about “rich people need to defer to the poor on poverty-related policy ideas” more seriously. This has become so overused that I roll my eyes at it: “Could quantitative easing help end wage stagnation? Instead of asking macroeconomists, let’s ask this 19-year old single mother in the Bronx!” But Scott provides a lot of situations where that was exactly the sort of person they should have asked. He also points out that Tanzanian natives using their traditional farming practices were more productive than European colonists using scientific farming. I’ve had to listen to so many people talk about how “we must respect native people’s different ways of knowing” and “native agriculturalists have a profound respect for the earth that goes beyond logocentric Western ideals” and nobody had ever bothered to tell me before that they actually produced more crops per acre, at least some of the time. That would have put all of the other stuff in a pretty different light.

I understand Scott is an anarchist. He didn’t really try to defend anarchism in this book. But I was struck by his description of peasant villages as this totally separate unit of government which was happily doing its own thing very effectively for millennia, with the central government’s relevance being entirely negative – mostly demanding taxes or starting wars. They kind of reminded me of some pictures of hunter-gatherer tribes, in terms of being self-sufficient, informal, and just never encountering the sorts of economic and political problems that we take for granted. They make communism (the type with actual communes, not the type where you have Five Year Plans and Politburos and gulags) look more attractive. I think Scott was trying to imply that this is the sort of thing we could have if not for governments demanding legibility and a world of universal formal rule codes accessible from the center? Since he never actually made the argument, it’s hard for me to critique it. And I wish there had been more about cultural evolution as separate from the more individual idea of metis.

A final note: Scott often used the word “rationalism” to refer to the excesses of High Modernism, and I’ve deliberately kept it. What relevance does this have for the LW-Yudkowsky-Bayesian rationalist project? I think the similarities are more than semantic; there certainly is a hope that learning domain-general skills will allow people to leverage raw intelligence and The Power Of Science to various different object-level domains. I continue to be doubtful that this will work in the sort of practical domains where people have spent centuries gathering metis in the way Scott describes; this is why I’m wary of any attempt of the rationality movement to branch into self-help. I’m more optimistic about rationalists’ ability to open underexplored areas like existential risk – it’s not like there’s a population of Tanzanian peasants who have spent the last few centuries developing traditional x-risk research whom we are arrogantly trying to replace – and to focus on things that don’t bring any immediate practical gain but which help build the foundations for new philosophies, better communities, and more positive futures. I also think that a good art of rationality would look a lot like metis, combining easily teachable mathematical rules with more implicit virtues which get absorbed by osmosis.

Overall I did like this book. I’m not really sure what I got from its thesis, but maybe that was appropriate. Seeing Like A State was arranged kind of like the premodern forests and villages it describes; not especially well-organized, not really directed toward any clear predetermined goal, but full of interesting things and lovely to spend some time in.

Would the idea that everyone needs/should go to college and so we’ll make loans easy to take be an example of another high modernist failing in our modern era? Or am I stretching the definition/concept here?

Tricky question.

The subsidies seem to support your claim but on the other hand employers and prospective students are the ones driving the demand of degrees, and they are the ones holding any metis in this case. which would make the high-modernists those who claim we should tear down education since all our lab-room science shows it’s useless.

So this seems more like a case where the common people and the state are on the same side, and possibly shooting themselves in the foot.

How much metis is that, really? The drive towards college is a relatively recent phenomenon, compared to the other examples provided, and I’d hesitate to agree that there’s any sort of battle-tested equilibrium at this point.

Good point, I’d argue more than 100 years so there’s not much to go on. I think that puts us in a position where this just isn’t an issue that relates to existing knowledge vs. lazy rationality framing.

What about the argument that employers only care about degrees because it’s a way to exclude icky poor people without suffering an employment-equity lawsuit? Metis and responses to incentives look similar from the outside.

Aren’t they the same thing from the inside as well?

I mean, whether we are talking about people subconsciously or consciously not wanting to hire “icky poor people” they probably want to avoid it because they believe it would hurt them.

The higher-education-subsidy-abolitioners are still trying to change the current order because they Know What’s Best for other people. (except that davidp is right and no side here can claim it’s using lots of data)

Instead of getting data by looking back in time, why not look at other countries?

That seems unlikely to me. I would expect there to be some “status” value associated with college, but right now the gap between what the average college educated worker is paid and what the average worker without college is paid is huge, and has been rapidly growing larger and larger.

http://www.epi.org/publication/class-of-2016/

>Among young high school graduates, real (inflation-adjusted) average wages stand at $10.66 per hour—2.5 percent lower than in 2000. Young college graduates have average wages of $18.53—roughly the same as in 2000 (only 0.7 percent higher).

I have to think that there is some sense in which college is actually making workers more economically productive compared to workers without a college degree (speaking in relative terms, it may just be that people without college are much less economically valuable today). Otherwise I would not expect that gap to be that large; if a business could hire non-college workers and save something like 40% on it’s labor costs without losing economic productivity, I’d have to think that more would be, which would narrow the gap.

Like the joke Scott referenced about the economist saying “If there was a $20 bill on the ground someone would have picked it up by now”. If college educated workers really didn’t add much in terms of worker productivity or in some very significant way provide value to a company, then there are a heck of a lot of $20 bills businesses are just leaving on the ground, and I find that unlikely.

Could be they’re just more ambitious.

I’m sure that’s a part of it, there are obviously a lot of confounding effects here that make this hard to measure. But I think the fact that the gap between “college” and “non-college” is getting *bigger* is significant, and probably implies an actual increasing difference in the value of the worker.

Nah, I think it is just that the value of intelligence continues to rise as economies become more automated, so proxies for intelligence such as college also correlate better with income.

That argument:

1: Doesn’t fit the history. There have been plenty of poor people through out time. College degrees have only been in high demand relatively recently.

2: Doesn’t make any sense. The U.S. is not generally that classist to go ‘Ewww. Poor people!’. Certain extreme levels of poverty might trigger a disgust response, but that is a very small band of ‘poor’. Those that think otherwise are likely projecting.

College degrees came to prominence as an employment requirement because degrees are being used as a proxy for IQ tests.

That is not a fact. There no reason why IQ should be a better indication of ability to do job X than having done job X. It doesn’t even convey information about conscientious. And IQ testing is not widely used in countries where it is not a legal problem.

The obsession with IQ is one of the great irrationalites of the rationalsphere.

Remember also that in the US context, “poor” is often a euphemism for “minority”.

“That is not a fact. There no reason why IQ should be a better indication of ability to do job X than having done job X.”

Yeah, it is. Just because you don’t like it doesn’t mean that it isn’t true. The ban happened in the late 70s which is right before the college tuition started to skyrocket. While correlation isn’t causation, it does wink suggestively and say ‘look over here’. Having worked with a few hiring managers, I can tell you that the thought is going through their minds, regardless of what they put on paper.

Intelligence and conscientiousness are the two single greatest traits for predicting job performance. (as well as lifetime income) It is so critical that the U.S. military has set a lower bound on the IQ it will accept (yes, they use the ASVAB, but a rose by any other name). Also keep in mind that hiring decisions aren’t really about finding the best person, but the person for whom hiring is the easiest to defend. Which is why you see years and years of experience being required even though performance for most people has hit diminishing returns after 3 years.

“IQ testing is not widely used in countries where it is not a legal problem.”

Different cultures have different priorities. In the U.S. we love the interview even though it has been determined time and time again to be worthless.

Here in the UK we’ve had similar pushes to increase university enrolment, and as far as I’m aware it’s not illegal over here to set IQ tests for job applicants.

There’s no ban as such in the US.

There is a legal regime whose practical implementation causes people to greatly fear lawsuits should they implement IQ testing for prospective employees but to not fear lawsuits should they implement a (possibly informal) requirement for college degrees.

This is the sort of thing that many people will colloquially refer to as a “ban” if they don’t want to spell out an extra thirty words.

I dashed out the first reply on my lunch. Now I have a bit more time to reply in depth. Part of the problem is that several different assertions have been blended, so I will try to separate them and address each individually. I can only speak for the U.S., so in all my further statements, it can be assumed that I am talking about U.S. conditions, unless otherwise specified.

Are intelligence tests prohibited? It is technically correct to state that intelligence tests are not strictly prohibited. Such tests are (for a variety of reasons) a major legal minefield for a company to walk through, so most companies are loathed to use them.

Is intelligence a good predictor of job performance? Unequivocally yes. The more complex the job, the more intelligence matters. Obviously, you will hit diminishing returns fairly quickly on intelligence if you are hiring someone to dig ditches with a shovel. Intelligence isn’t the only thing that matters, but it is quite important. This is especially true here, where low complexity jobs are undergoing rapid extinction.

Is a college degree a useful proxy for intelligence? Yes. The average IQ of a college student is 115, which puts the typical college student at roughly 1 standard deviation above average.

Saying that having done the job is the best indicator of being able to do the job is about the equivalent of saying A = A. From a prediction standpoint, that is essentially a tautology. The problem is with the application.

Just because someone was working at a job doesn’t mean they were any good at it. The world is filled with people that are performing marginally competent work at best. So just because they were ‘doing the job’ doesn’t mean you want them doing the job for you. Productivity isn’t normally distributed, it is Pareto distributed. 80% of everything is crap, and that goes for people too. As an employer, you are essentially blind to someone’s prior job performance in all but the most extreme cases. So just give them a work sample you say? Well…

Complex jobs are very difficult/time consuming to model for a prospective worker. Such jobs frequently employ company specific (or industry specific) software/processes. This makes for a job that someone isn’t going to be able to just sit down and do. If it is a job they can sit down and do, and prospective employee produces output of value, you may be legally obligated to pay the person for the output. As any given model is likely to not have been extensively litigated, using a job model for employment decisions will open the employer up to litigation risk. So proving that someone can do the job tends to be an expensive proposition.

With that in mind, consider who is doing the hiring. If it is some HR lackey or low level manager, you are probably looking at someone whose primary goal is to be able to defend the hiring decision, and fill the slot with an acceptable hire with a minimum of time/expense, not pick the best hire.

As to other cultures/economies, there are complicating considerations. Just because something is effective doesn’t mean that it is used, as well as just because something is used doesn’t mean it is effective. Additionally, not everything is done in the same manner. Unless you have had an extremely unusual career or have some research to share, it is highly unlikely that you are in any position to speak authoritatively on how other countries handle hiring. China, for example, does extensive intelligence testing. They just call it the civil service exam. Japan does all their testing upfront in the school system. In both of those cases, if you were looking for the employer to present the test you would likely miss it, as the test already happened.

@Jason K.

Where are you getting this 115 number from? When I tried to find out the average IQ of an undergrad degree holder, it was 105. Given that more than 30% of the US population holds undergraduate degrees, wouldn’t it be impossible for the average to be 115, since that 115 is ~85th percentile?

Jason: So, how can you distinguish between, say, “College serves as a proxy for IQ tests” with the alternate hypothesis “More education tends to make workers more economically productive, especially at the higher-skilled positions that are well paid today, so giving someone a college education increases their value in the labor market”?

Well, we could try seeing if students learn anything at college, as a first pass, before seeing if it’s useful.

I’ve certainly heard of reports that they often learn virtually nothing the first two years.

If you are going to go “yeah, it is”, you need to follow it with something more proof-like than a suggestive wink.

The issue is how good it is in relation to other predictors that an HR department might want to use.

Does an IQ test give you information about conscientiousness and knowledge relevant to the role? No. So it is still looking like degrees are a better indicator than an IQ test alone.

What”s bad about tautologies? They don’t convey novel information. What’s good about tautologies? They are true.