[Content warning: suffering, oblivion]

Every so often, someone on Reddit realizes that about half of people wipe themselves with toilet paper sitting down, and the other half do it standing up. This discovery is followed by horror on both sides that other people do it differently.

I occasionally have the same feeling when I talk about ethics. Every so often I run up against a base-level clash of intuitions with somebody else, where they disagree on a preference I would have expected to be self-evident. This is pretty bad, since some forms of consequentialism are a lot more elegant if we imagine that all apparent moral disagreements are just people failing to think through their own preferences clearly enough and everyone really agrees about morality deep down.

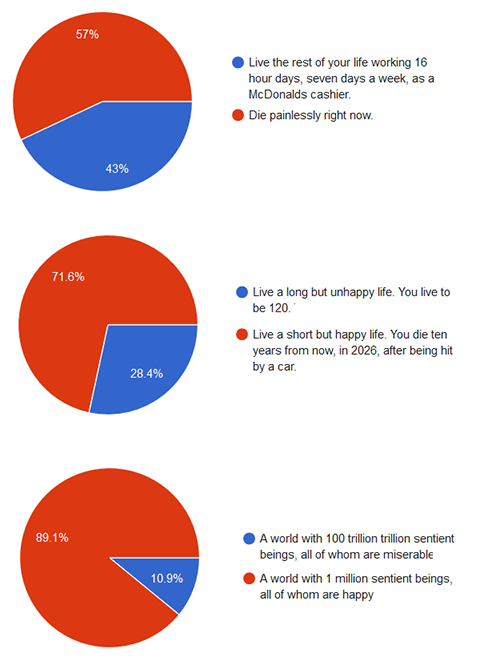

A lot of these clashes of intuitions have to do with the idea of suffering versus oblivion. In order to explore this further, I asked people on Twitter and Tumblr to answer some survey questions like the following:

1. Would you rather:

Option A: Live the rest of your life working 16 hour days, seven days a week, as a McDonalds cashier. You will have no time off except the time you need to eat, sleep, and use the restroom. Your entire life will be spent doing McDonalds cashier related tasks. When you are no longer able to perform your tasks, you will die painlessly.

Option B: Die painlessly right now.

2. Would you rather:

Option A: Live a long but unhappy life. You live to be 120. You spend most of your time unhappy, but you are not actively suicidal.

Option B: Live a short but happy life. You die ten years from now, in 2026, after being hit by a car. Until then, you do fulfilling work, have happy relationships, and meet with success in most projects.

3. Would you prefer:

Option A: A world with 100 trillion trillion sentient beings, all of whom are miserable, but not quite so miserable that they wish they were never born.

Option B: A world with 1 million sentient beings, all of whom are happy and consider their world a utopia.

4. What percent certainty of going to Heaven would you need before you would prefer a world with both Heaven and Hell to a world where death ends inevitably in oblivion?

Before checking the results, I had five hypotheses.

First, people would be split in their answers to these questions, with strong feelings on both sides.

Second, answers to all questions would correlate along a general factor of oblivion-preference versus suffering-preference. That is, people who would prefer oblivion to working at McDonalds would also be more likely to prefer a short life of happiness to a long life of unhappiness, et cetera.

Third, this factor would predict whether somebody endorsed a form of population ethics which promotes creating new people (question 3 is sort of just asking this already, but I also included a more direct question along those lines).

Fourth, this factor would predict some real-world consequences like whether people believed in a right to euthanasia and whether they were signed up for cryonics.

Fifth, happier people would be more likely to prefer suffering over oblivion, because they view life as generally excellent and so oblivion represents more of a sacrifice for them.

1090 people took the survey (social media is a wonderful thing). The survey specifically asked that you not think about other people or the question’s effects on them and just choose whatever made you selfishly happier. Several people complained to me that the concept of “generally unhappy, but does not wish they were never born” didn’t make sense to them, which I guess is data in and of itself. The results were:

The first hypothesis was confirmed:

On the fourth question, people answered everything, from demands of certain salvation (n = 320), to being okay with certain damnation (n = 69), and everything in between.

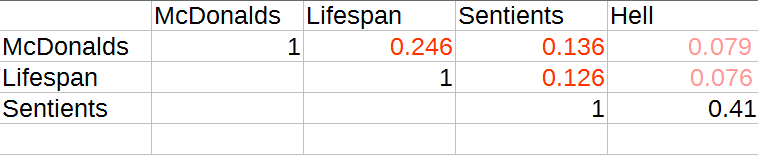

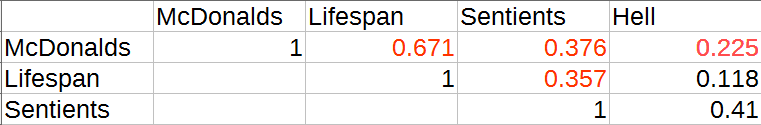

The second hypothesis was weakly confirmed:

Orange results are significant at p < 0.05, red results at p < 0.01. We did not adjust for multiple comparisons.

There are significant correlations between most of the questions, but they are not very strong. When I limited the analysis to the people who felt most strongly about their answers to the questions, the correlations went up a bit:

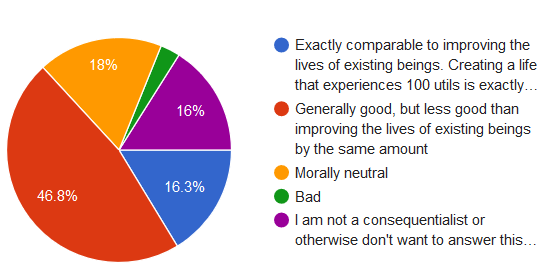

The third hypothesis was not supported.

I asked people a pretty direct question about the ethics of creating new people:

5. Creating new sentient beings is:

Option A: Exactly comparable to improving the lives of existing beings. Creating a life that experiences 100 utils is exactly as good as improving existing lives 100 utils.

Option B: Generally good, but less good than improving the lives of existing beings by the same amount

Option C: Morally neutral

Option D: Bad

Option E: I am not a consequentialist or otherwise don’t want to answer this question

The results were:

The only correlation with any other question was with the one hundred trillion trillion sentients question, which is basically asking the same thing in different words. The correlation with all the other questions was not significant and in fact very close to zero.

The fourth and fifth hypotheses were weakly supported.

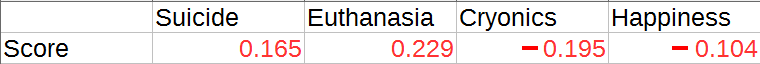

I gathered a general score of people’s pro-oblivion or pro-suffering bias based on their answers to the first three questions and how strongly they felt about them. It predicted the following:

The specific questions here were:

Whether you believe everybody has a right to commit suicide if they want, including people who are not terminally ill.

Whether you believe people who are terminally ill should have a right to suicide, ie traditional euthanasia.

Whether you are interested in signing up for cryonics.

And whether you consider yourself a happy person.

All were correlated with preference for oblivion over suffering in the expected direction, but not very strongly.

So it looks like people have very different opinions about when to choose death versus suffering, but that these opinions are inconsistent and only weakly driven by broad cross-situation intuitions.

You can see the survey here, but please don’t take it since I’m done getting data. You can download anonymized results here (.xlsx, .csv)

When I took this I found myself spending a lot of time looking at the second problem in particular and thinking “what counts as ‘happy’ or ‘unhappy’?” I didn’t feel like it was a very good question because my answer ended up being entirely predicated on what I decided probably counted as “unhappy”.

I would have also appreciated an option on the third question analogous to on the fourth (“I refuse to answer this”); I left it blank.

I agree with this. The second question wasn’t as clear in the tradeoff as the mcdonalds question, so I ended up choosing the longer life despite choosing “die immediately” for #1. Also for the “creating happy sentient beings” question, all I kept thinking of is Eliezer’s argument that it might not be important to make more unique people if you live in a Big Universe, so that tilted me slightly in favour valuing existing people.

Link to the referenced argument for people who are interested http://lesswrong.com/lw/ws/for_the_people_who_are_still_alive/

Weird I choose the opposite way for the same reason. There’s nothing stopping McDonalds from being enjoyable and there’s a huge amount of room to exploit the rules there whereas if you’re unhappy you can’t do anything about that.

+1. IMHO a lot of these fell in the “not a good question” category, because depending on how I interpreted the question I could go either way.

For example, the heaven/hell question depends on your personal conception of heaven and hell.

I felt the same way about the heaven/hell one. There are some depictions of hell that I think seem like they would be fairly entertaining and I would only need like a 60/40 split. Then there are the really bad depictions where I would need basically a 100% chance of going to heaven before I agreed to it.

I’m an atheist and thus not vulnerable to definitions of hell that amount to “permanent separation from God”, but isn’t the usual understanding something like “eternal physical and/or mental torment”? Like, being tortured for eternity? Spending a few trillion years being burned, then a few trillion being frozen, and then a few trillion of both at the same time, just as a warmup to the whole eternity thing, where they really start to make it rough?

Fourthed. Reading that question I was thinking, “am I even happy right now?” There are plenty of things I’m hoping to do with my life, but ‘be maximally happy all the time’ is definitely not at the top of the list.

Is my 120-year-old unhappy life comparable to the scenario from the first question (unending drudgery with no hope of respite)? Or is it just a life where struggle and disappointment are the norm and maybe happiness and success will peak through the clouds every once in a while (AKA normal real life)?

I’d sign up for the unhappy long life if I could also accomplish things. You know, if I cured cancer or wrote the great American novel or something. But not if it included also not getting to do the things I want.

The big thing that I could feel swaying me emotionally is the thought of ten more happy years. I like the thought of ten more happy years. But at the end of those years …. I would be more likely to want to switch answers. I’m not ready to die NOW. I’m never ready to to die NOW. But I’m already accustomed to the idea that I will only get a certain number of years, and reading the question I find I’m kind of insensitive to the number.

I would say all the questions are not anyhow precise, resulting in wide interpretations, resulting in upper-capped correlation.

My conception of the world is pretty much summed up by the opening to the prose version of the Hitch-Hiker’s Guide (you know the one):

Mild to moderate unhappiness is pretty commonplace, and people bear up under it with varying degrees of success, much the same way many people bear up under chronic aches and pains with varying degrees of success.

For my part, I haven’t dipped into real depression in some time now and hopefully I won’t anytime soon, but I’ve also come to terms with the fact that a certain degree of unhappiness is probably just…there. Again, rather like long-lasting minor to moderate pains: as long as you can successfully divert your brain from them: Interesting intellectual stimulation, easy sex, drug/alcohol/fats and sugars abuse (but I repeat myself), guided meditation, friends and family, whatever. People choose different coping mechanisms that are to varying degrees helpful or self-destructive, and when the unhappiness gets too severe some percentage have those mechanisms fail and decide that death is preferable.

So why wouldn’t I choose a long, generally unhappy life? As far as I can tell, so has the overwhelming majority of the human race for the overwhelming majority of history.

Those blessed by the right combination of circumstance, intelligence and cognitive skills fitted to those circumstances, and brain chemistry to go through life with ‘happy and content’ as a default state strike me as more alien and distant to me than the richest of multi-billionaires. Hell, half of THEM are pretty damn unhappy, apparently.

I’ve come to think that people are divided, more than anything, by two metrics: baseline anxiousness and baseline happiness.

The sorts of things people do and the sorts of people they become are mostly due to that.

But maybe I’m biased by my experiences. I used to be high-ish anxiety and average happiness, now I’m low-ish anxiety and high happiness. The world just seems really cool and it’s awesome being me in it. Even though I’m not particularly living a golden life; it’s really just perspective.

So I guess you’d find me pretty weird, based on what you say. People often do. But people also tend to like being around me. Happy passion is magnetic.

Also, it works wonders for a straight man’s love life 😉

Care to elaborate what shifted your baselines?

Sure, I’ll try my best. I’m a bit short on time at the moment but check back tomorrow.

I have a strong interest in helping other people become happier and more dynamic. The difference it makes is remarkable. But the process is long, difficult, and kinda hard to describe, so unfortunately there’s no one-size-fits-all solution. If only it were as simple as ‘take this supplement and exercise.’

That said, I think that being in good health is a great start and being in ill health will make this a much more uphill battle, so get that sorted if you can.

This is gonna be a bit philosophical for a bit, but I think it’ll come around to making sense.

The bulk of the work is in habituation, mindset, and (for lack of a better term) ego discipline. Basically, I started with this – a determination to accept the truth, whatever it might be, however little I may like it. In spite of that, I had quite a few illusions about reality and the world – things that you use to create an identity, basically. For example, I was VERY idealistic about romantic relationships – find the ONE, stick with her forever, make it work no matter what by heroic force of will kinda stuff.

So when I was confronted with a romantic relationship that WAS falling apart in spite of all that, I had to rip all that up and start over. It was like a part of me – a central ‘I’ – looked at the naive, idealistic boy I was, and said – you’re good. You’re nice. I like you. But you’re not true, so you have to go. You’re gonna fight like hell to stay, but I’m going to win.

And as I got to work I was surprised by what I found – my head was just FULL of ghosts like this. Ones that told me that I needed to use big words to impress people, cause it’s really important to seem smart. Ones that made me feel guilty for wanting things. Ones that told me I shouldn’t talk to strangers because that was scary. Ones that did all sorts of things like that. And when you tried to remove them – by which I mean, ignore the impulses and desires they create and instead do what you genuinely want to in the moment (rather than what you’re conditioned to do or ‘ought’ to do) – I found out that it hurt like hell. I thought that was strange. The model I used to explain it (psychodynamic handwaving it might be, but it worked to model the situation) is that all these things were defending my ego – because there was, fundamentally, a sense that I wasn’t enough/worthy/good if I didn’t listen to all the ghosts and do as they say. And so I was being twisted around by them without even knowing it, living in imaginary headspaces, having imaginary preferences, doing things based upon imaginary systems of risk and reward that correlated poorly with ACTUAL risk and reward….little wonder I wasn’t more than basically content. I didn’t even know what I ACTUALLY liked to do or be.

So I began steadily trying to keep myself aware of what my impulses were in the moment. And when I found myself recoiling from that impulse, I’d chase down why and I’d find fear, or anger, or pain hiding under the surface – and I’d do my best to amplify that negative emotion, feel it fully, so I didn’t have to hide it any more. Get it out. And then I’d just DO.

A few of these things still pop up from time to time, but now it’s mostly easy and infrequent. And when you strip away all the old ghosts and stories you told yourself about yourself, you can kinda just choose what attitude you’re gonna have at your core. I just kept a central attitude through all this that I’m awesome just for existing and I’m gonna win against obstacles, and that just became my default. There’s nothing egotistical about it – I don’t think I’m better than anyone and I don’t need to prove anything to anyone, I’m just…enough.

See, the thing now is – I’m not trying to tell stories about my actions and preferences and past and so on. I just AM what I am, and when I tell stories about who I am or why I’m doing what I’m doing I do it mostly for fun or utility. Just for fun I basically started telling myself an ‘identity story’ that I’m just godlike in intellect and charisma, and people love it. Because they can tell I’m not taking it too seriously. But it does make me project confidence and charisma, and when some super-cute girl starts pushing back and trying to topple me, and then we go back and forth until she succeeds and then we both just laugh about it cause I don’t care, it’s just a story, well….

Things tend to go well 😉

The other thing I did (this is gonna be a long post sorry) is I forced myself to do a lot of things. Just go on a random road trip, see the place and talk to the people, spur of the moment. Go to clubs and dance. Make out with a girl I don’t know. Go to a bar and talk to the dudes in the athletic jerseys. Play an instrument. Train for an athletic competition. Make a bunch of videos for YouTube. Whatever. If it kinda scares you so much the better.

What you find if you pay attention is this – you will actually end up liking some things you couldn’t have predicted. And some stuff you thought you liked was, when you’re honest with yourself, just something you were doing to get praise/self-esteem, or that you were using as a buffer to NOT do other things. A reading hobby can actually be a pretend-I’m-smarter-than-everyone hobby, or a I’m-scared-to-socialize hobby.

Eventually you rewire yourself. And in the process you got in lots of circumstances that make you less afraid of new things and more competent in general. The anxiety can be just another ghost.

One final thing – I have struggled with biologically-created anxiety as well. This doesn’t respond the same way precisely; I’m better at managing it when it happens but I can’t just will it away. But I’m lucky enough to have found what triggers it for me and can generally avoid it (I mentioned it in a previous thread; basically my immune system reacts strongly to barley and one of the symptoms of my accidentally eating it is anxiety. Biology is weird).

And who knows, this could all just be false attribution to something that wasn’t actually causative. It made a huge difference for me, in the end. Not much can bother you once the roots of your existence have been turned anyways.

I don’t know how replicable all this is. But I know a few more people like me, and a common thread seems to be reaching some sort of breaking point where all your ego defenses have failed. But maybe such times are actually common, and most just don’t react in the proper way to grow from it, and just make new ego investments instead.

Forge on.

Thank you for the extensive reply. I found it very interesting that the same “determination to accept the truth, whatever it might be, however little I may like it” can lead some people to improve their baseline happiness while leading others to descend into limitless despair because all meaning is imaginary etc.

Dunno if you’re still keeping track, but

The way I think of it is, when you look at things as they are and perceive that there’s no intrinsic meaning to things, that’s nihilism. And it has two possible responses. You can despair. Or you can realize how awesome that is, because it means you can give your own meaning to everything.

Nihilism can make little gods of men, if they only have the wherewithal to accept that degree of freedom and responsibility.

Another agreement here about question #2. Although maybe it was deliberately vague? For #1, the answer was clear: I’d rather die painlessly right now than do nothing but be a McDonald’s cashier for the rest of my life.

But “spend most of my time unhappy” until 120? How unhappy am I? Am I still able to do things? Are there still things I take pleasure in? Do I experience occasional moments of happiness or contentment? If the answer to all these questions is “yes” – and the wording of the question makes me suspect it is, though I’m not sure – then I’d pick living to 120 over dying in ten years.

I agree with anon that ‘be maximally happy all the time’ isn’t a great goal. I spend most of my life in a mood best described as “vaguely content neutrality.” While I am prone to occasional bouts of moderate – though still functional – depression, most of the time I am neither particularly happy nor particularly unhappy. This is fine, far as I’m concerned. I spend more time thinking about what I do and how I behave – whether I’m being a good person, living up to my ethical standards, doings that are productive and/or interesting and/or fun – than whether I actively feel happy (so long as I’m not depressed, that is).

I went the other way – I’d rather be a McDonald’s cashier, because at least I could talk to the customers for short periods, and think about stuff. I’d take the chance at being able to make it a worthwhile experience.

Yeah, if I wasn’t actually depressed, just busy flipping burgers, I could totally make my own happiness out of that. You can be happy almost anywhere if your psyche will let you. (The opposite is also true.)

Agreed. My first impulse was to just die, but after some thought I decided I would prefer working at McDonald’s. At any time I could stop working and be euthanized, so why not give it a try? I would still be able to: talk to (and maybe help) co workers, get to know some funny regulars, listen to music while cleaning up, masturbate (or even have real sex), ride my bike to work, eat food I like.

Granted, the schedule is grueling and my body might not last long, but who knows? Read the stoics and try to make your own attitude.

The survey did specifically ask for your own selfish opinions, and not how it affects other people. Therefore, what counts as “happy” would be what counts as happy to you, and what counts as “unhappy” would be what counts as unhappy to you.

My issue with the question is, the survey is clearly geared towards Scott’s readership (one question using Utils shows me that he didn’t really expect it to be taken by anyone outside this community), yet he used the unprecise wording “mostly”. Mostly could be anything over 50%. At 60% unhappiness, I’d still take the longer life, but at 95% unhappiness, I’d take the early death. I’m not quite sure where the split is for me. I’m thinking finding out where that split is might have gotten some more interesting results.

What kinds of people took the survey? Because if you’re looking for people’s moral intuitions, asking mostly the kinds of people who would know what “utils” are would likely get you a skewed response. I wonder how much the answers of people who are not familiar with ethical philosophy (or at least not familiar with consequentalism, or rationalism) would differ from those of people who’ve spent more time thinking about the kinds of questions you’re asking.

Twitter followers and subredditors of slatestarcodex.

And also those who follow slatestarscratchpad on Tumblr.

well that seems like an awfully narrow subset of people. Valid for rationalists maybe, but not the general population as a whole.

I didn’t know what a util was so I had to Google it. Apparently it is an arbitrary unit of measure, so not really a unit of measure at all. I don’t understand how such concept is consistent with the rationalist or scientific program. Can someone enlighten me as to the usefulness of a unit of measure which is not empirically verifiable? It strikes me as highly problematic.

Scott often writes about the flaws in social science methodology. I would think that a failure to conform to the standards of empirical science is among them. How can social scientists do good science if their terms are not empirically verifiable?

It’s not arbitrary so much as hypothetical. We know that, say, eating pizza is more good than eating poop, so in theory we should be able to measure the amount of good for each. Once we can quantify it, we should then be able to perform calculations on it, and usher in the utilitarian utopia.

The fact that we haven’t come up with a way to actually measure utils is but one of many problems for utilitarians.

I see your point. I suppose my question is, what is actually being measured? I read “more good than” as “prefers”. So, any measurement would have to measure the strength of one person’s preference for one thing over another. That should be, in theory at least, measurable perhaps with some kind of neurological imaging. But at the end you still only have the data point that one person prefers one thing over another, or even many people prefer one thing over another. That doesn’t seem very useful.

If we discard legacy metaphysical terms like “good” and “bad” then we can think of ethical preferences in a practical way. If someone holds a preference I find objectionable I can attempt to persuade them otherwise. (Here we are in the realm of rhetoric rather than science.) I can also reward preferences (especially when expressed by behavior) I like or punish preferences I don’t like. And this, I would argue, is exactly what people do.

Why was there no option for 5. of believing that creating new sentient beings is superior to equivalently increasing the happiness of existing ones?

Does anyone really believe this?

I do. I had to take option E, and I was disappointed that you didn’t even offer me my real choice.

Well, I guess my survey about how other people have ethical preferences I wouldn’t expect failed because someone had an ethical preference I didn’t expect. How could I have possibly seen this coming?

Consider the “hundred trillion sentients” question – how do 11% of people choose the hundred trillion option, unless at least somebody feels like “more lives is a good in itself”?

I’m honestly surprised you included the 100 trillion sentients question if you thought no one assigned utility to new life.

I’m also perhaps irrationally annoyed by “asymmetrical” survey questions even if I think no one will select one option – usually you get a range of options from worse -> neutral -> better, but you left off the whole “better” end!

This does seem like another endorsement of the “full coverage wherever possible” principle for survey design. Non-continuous opinions can be hard this way (e.g. “I am not a consequentialist”), but as a general rule it’s good to deal in every part of a continuum (i.e. ask all of “better, the same, worse”).

I’m not 100% sure it would have caught this case, but it certainly seems relevant.

Implying that a world tiled with sentient beings would be optimal?

Why must utility be linear with population? If there are only 100,000 people, adding another is a huge relative increase in utility (otherwise people may go extinct, and then no one is left to produce utility). If there are already a trillion people, adding an extra is less meaningful. A stable maximum is certainly possible.

Thought the same thing, but I’m not a utilitarian or consequentialist, though both types of reasoning find their way into my own.

Serious question: could you please try to explain your reasoning and/or intuition for this? Like Scott, I’m somewhat confused as to how this belief could even arise.

Let’s say you like birds. Would you like a world that contains one billion thrushes, or a world that contains one billion total birds split between thrushes, nightingales, cuckoos, magpies, herons, hawks, toucans, parakeets, storks, albatrosses, and blue-footed boobies?

Let me be less indirect.

Happiness is not fungible between humans, in that no two humans ever experience exactly the same happiness. Jill!happiness and John!happiness may belong to the same genus, but they are different species. They may be similar enough that you can aggregate them, but that aggregation is lossy because it necessarily ignores the differences between Jill and John’s experience. Therefore, given the choice between giving Jack and Jill both an extra 25 utils, or creating Jack with 50 utils of his own, I choose the latter. In either case we’ve increased the total utils, but in the second case we’ve created a brand-new kind of happiness, namely Jack!happiness. This is a good thing.

I’m not an advocate of the view necessarily, but the first justification that came to mind goes something like this:

As far as I can tell people experience “utils” in a range, nobody is approaching infinity. Say your population of sentient beings is normally distributed around some mean of experienced utility, lets use 100. You have the option of either creating a new being with 50 utils or taking an existing one and bumping it from 100 to 150. In the former case you’ve created a new entity with lots of upside potential. In the latter case you’ve pushed an existing entity to a possibly unstable extreme. By creating new beings you improve the theoretical maximum utility in addition to improving the average.

“in addition to improving the average.”

I think you mean the sum, because the average is decreasing.

Because the alternative is extinction, not just of one’s self but of one’s species.

This is interesting to me, if somewhat odd, the idea that species just existing is more important than species or population of sentients existing that actually want to be around. Is this what you mean?

Anonymous I understand the sentiment, in other words the group and it’s survival should be more important to me than myself? That’s a difficult one to swallow I must admit.

Firstly, humans do usually want to be alive, so even the most hardcore bite-all-the-bullets preference utilitarian should not want the human race to go extinct.

Secondly, yeah, I at least am sad about e.g. the extinction of random animal species – just like I would be sad if a library full of unique books was burned. This would apply to humanity even if there are other sophonts of equivalent or greater worth in existence, and all other concerns about humanity’s extinction had been cancelled out.

Thirdly, of course, there are questions of human values getting to spread across the universe, all that potential snuffed out etc.

Any value matters more to me than myself in sufficient amounts, so that isn’t an issue. Do you … not?

I’ve neurosis(I think that’s the term) around my existence and my feelings about society at large and it’s existence. I seriously don’t want to come off trolly, however overtime it feels like I’ve lost good feelings about humanity existing in and of itself. I’m not saying this is correct or good or etc. it’s just how I feel. The weird thing is how it’s tied up with my identity and how I’m not sure I’d want to go back to the good feeling because I’d feel like I’d lose my identity. I think this comes off of a lot of social isolation and depression.

Isn’t the simple utilitarian answer that, if we are extinct, no one is left to produce more utils?

Any definition of utility worth its salt should be transhumanist, so I don’t think we need to special-case human survival.

We got intelligence once, it can probably happen again. We got life once, it can probably happen again.

Yes. I don’t but for example I’m fairly sure Lucidian does. (http://untiltheseashallfreethem.tumblr.com/)

My solution to the problem of population ethics is to view humanity as a single organism. So my choices about creating new people have to do with whether they increase or decrease humanity’s overall chances of healthy survival.

Thus, if the choice is about spreading a billion new lives across the galaxy so that we’re no longer dependent on earth for survival, that’s better than allocating their utils + some extra utils to existing people stuck on earth.

You are fighting the hypothetical. Would your preference change if the million was distributed across the universe in a manner that made them optimally safe?

Fighting the hypothetical here is valid because the questions have to be interpreted as they are written.

Scott was surprised that people would think that having fewer people people is inherently good. My point is that either more or fewer can be good, but it all depends on what it means for overall civilization health (and NOT merely on individual happiness). It’s how I handle the famous “repugnant conclusion” that requires assigning an inherent value to higher population. So in my value system I can’t answer the survey question without more context about what it means for the civilization.

I’d rather see it as a whole of humanity over time. That is, you get a million happy people, but that’s it. No more sentients after that. Or the history continues until you get 100 trillion trillion, and then humanity dies off.

I use the same solution, and chose the 1 million utopia because I figured that scenario left more resources for a space program.

Yes.

In fact, I find it strange that the question even has to be asked.

Absolutely!

Wasn’t this the point of Asimov’s robot novels?

The spacers were long lived and had great lives but the earthpeople had a healthier society because since they were having more babies their society was more dynamic.

I’ve seen the same meme in High Fantasy novels. I.e. the elves live longer, but humans live more meaningful lives.

As a counterpoint. I believe the High Elves of the West were implied to have derived their wisdom and equanimaty from their longevity. Their silly songs about the simple things in life reflected a zen-like understanding of the eternal recurrence that only comes with experience.

Kind of off topic, but a friend of mine has an excellent headcanon explaining the lack of elven engineering (as opposed to magic): elves live so long that they have no need to accomplish anything with any sort of speed. If they decide to stand there and yell at a mountain to get it to move, they are perfectly able to keep standing there and yelling until erosion has done the job more thoroughly than any dynamite.

That reasoning not only requires that the elf doesn’t need X fast, it also requires that the elf doesn’t need to have any of the second or higher order consequences of X happen fast, not even the consequence of “being in a state where X hasn’t happened yet for a long time”. Unless the elf has a terminal goal of moving mountains, this seems implausible.

Even if the mountain just blocks his view of Venus, why in the world would the elf not care that his view is blocked for a million years, regardless of how long he lives?

If elves are slow, then what does that make treants?

Assuming you mean ents (treants are the Dungeons and Dragons version), they have the same problem. If it really took them days to figure out what to do, what do they do if the forest is burning down?

I just remembered the story of a real world elf. And his name was Cliff Young. Adiabatic Processes are the best kind of processes.

I also wanted that option on that question (didn’t manage to finish the survey, fwiw).

Two people with happy lives are better than one with a life of double happiness.

(But then, I don’t believe that everything is reducible to a single util measure.)

That’s interesting. I agree that two happy people are better than one doubly-happy person, but I’d also rather create one happy person than two miserable people.

So for me, there’s apparently some “happiness cutoff,” above which you can start adding people. I couldn’t quite tell you where that cutoff is though, and figuring it out seems pretty squishy.

It’s a practical question for me, being a parent. Having one more kid is a lot of work and may leave less attention for the kids I have. On the other hand, that one kid would obviously have infinitely more happiness than if we didn’t have him. I definitely think in terms of a cut-off — will we all still be pretty okay with one more kid? Then let’s have another. If it pushes us from “generally happy” to “slightly miserable”, then let’s not.

Of course it’s difficult to tell in advance how much harder one more kid will be, but a good rule of thumb is that if you’re overwhelmed and unhappy NOW, creating another person is a bad call. If you notice a lot of extra happiness floating around, why not share that with a new person?

Alternatively: there’s an effort-to-utility conversion implicit in activity, and it has diminishing returns on increasing both quality and quantity of life: if you’re further along the curve on quality than quantity, you spend your next effort on quantity, and vice versa.

On this perspective, the trillion^2 miserable lives versus the thousand^2 happy ones depends entirely on the agency of the lives in question to improve or reproduce their own situation after the hypothetical expires.

I assume familarity with the parenthood paradox. In case not, first link that came up:

http://www.parisschoolofeconomics.com/clark-andrew/HappinessandtheParenthoodParadox.pdf

So in terms of revealed preferences of parents we are confronted I think with three possible explainations:

a) Parents are stupid and ignorant of said research. They are making a gut choice. Given the number of parents in the total population we should not be surprised that stupid and ignorant people hold inconsistent opinions.

b) Parents are rational but assume that their child’s lifetime happiness will more than offset their suffering and altruistically make this choice. My impression is that this is what parents tell themselves and others.

c) Parents indeed do indeed value creating sentinent live over happiness. Otherwise they would not reproduce. Something something evolution.

I don’t see why it can’t be all three, in various proportions, held by different people.

I didn’t mean to imply an exclusive or.

>a) Parents are stupid and ignorant of said research.

As a parent, I can confirm variants of this. Most parents (including me) had an incredibly poor knowledge of what parenting involves (simple lesson: use the outside view, rather than projecting yourself+child).

But for many parents, it’s about preferences (eg looking for meaning, doing your duty, taking on a new role) rather than hedonism.

Duty?

To take a spouse, sire children and raise the next generation.

There’s a fourth option: we don’t actually know what happiness is or how to measure it.

Yeah.

The best I’ve been able to come up with regarding happiness is that it’s a reward for living well. No progress of any kind regarding quantification, though.

I don’t think these people are taking the hypothetical the same way you would. The answers given are basically they’d prefer two people with identical levels of utility to one with double the utility, which of course means in the first world their utility is also increased because they prefer that world, in which case they’re just saying they prefer a world with more total utility.

Either that or they’re just valuing diversification as a risk management strategy, effectively saying it is better to own two different stocks valued at $5 each than one valued at $10, all else being equal, as your risk of ruin is less in the former case. A larger population is less likely to be wiped out.

Neither of these is the same thing as saying it’s an ultimate good to just tile the universe with sentient beings without regard to what extent they actually enjoy their own existence. Even in the second case, at a certain point the further risk decrease from one additional person eventually goes to zero.

That’s actually a major flaw in the questions. Asking people whether they would prefer X to Y doesn’t necessarily mean that they subscribe to a theory which leads them to preferring unlimited amounts of X to Y. Even if the question doesn’t put a number on it, people will answer as though they were asked about a finite quantity of X. If you want to know whether they would prefer X to an unlimited level, you have to explicitly say “would you prefer an unlimited level of X”. And if you want to ask if they would prefer an unlimited level of X even if it affects other considerations, you must explicitly specify that too.

Even the question about directly creating new sentient beings would normally be read by most people to mean “creating some finite number of sentient beings” and does not imply there is no point of diminishing returns past which they would no longer want to create any.

Not only that, but people are pretty clearly imagining having their own children, and it is hard to extricate rational reasons to prefer more persons to fewer from involuntary post hoc justification of the basic compulsion felt by all biological creatures that voluntary reproduce to create copies of themselves.

No one is imagining a hypothetical world in which they flip a switch and, several hundred billion years later, long after humans have gone extinct, 100 trillion trillion gas creatures from 2061 come into existence magically that we could never communicate with or even recognize as alive, that can’t even communicate with each other but nonetheless are capable of experiencing positive utility. They’re imagining all of the pride and good feeling that comes from family, culture, and shared history.

The answer to “Does anyone really believe X?” is “yes” independent of X.

do it for the children!

“to being okay with certain damnation (n = 69)”

Eeeeer…. surely they are just winding you up?

I ended up answering 50%, but a more honest answer would’ve been “either 0 or 100, depending on the hell in question”. If it’s something like the hell in Hell is the Absence of God or The Great Divorce, or if it’s finite and you go to heaven after atoning for your sins or whatever, I’d absolutely prefer that over oblivion, so the question of heaven is moot; whereas if it’s “spend all eternity in literally the worst conditions possible”, I’m not gonna take that chance no matter how good heaven is.

Doesn’t that assume that the hell-bound are randomly selected as opposed to deserving? A whole stack of theology is about determining who is going to hell (or, what one needs to do/be/think/say in order to not go there).

You can be fine with 99% of people going to hell if you are in the 1%.

Or you can look at the Jehovah’s Witnesses who believe in hell and that they almost certainly will end up there because heaven is finite and so there probably won’t be room for them.

In that scenario, I interpreted the question as asking about the probability that I’d manage to successfully live a virtuous enough life to end up in heaven.

It’s worth noting that some religions (even major Judeo-Christian ones) use a Hell or Hell-analogue that’s simply not that bad. Judaism tends to deal in “nothingness” or “not heaven”, Mormonism deals in “atonement” (with a side of “nothingness”) and so on.

While I assume many people inferred Catholic-style “infinite bliss, infinite suffering”, it’s possible to get a wildly different standard while still answering in line with mainstream Western religion.

And then there’s Archbishop Blackadder’s conception of Hell:

I’m not sure how many people misunderstood the question. I noticed that the expected correlations got a little stronger when I deleted everything below 50, which is consistent with some of those people giving numbers the wrong way round.

On the most recent open thread, there was this poster

https://slatestarcodex.com/2016/06/26/open-thread-52-5/#comment-378754

Other people who put that answer may have had similar reasons.

For my part, I put 50% on that one.

I did not understand n “percent certainty of going to heaven” to imply 100-n% certainty of going to hell. I understood it as “your belief that you will go to heaven is n% correlated with the outcome as compared to population statistics,” i.e. at 0% you go to heaven at population odds.

I’m not a survey respondent, but this is similar to how I interpreted it when reading the question above. I took 0% to mean “life ending in oblivion” with no chance of going to heaven or hell, and a finite percentage to mean that degree of certainty (x) of life resulting in going to heaven or hell, presumably based on behavior, and 1-x chance of ending in oblivion. The question then seemed to be about how big x would have to be that you’d care about it.

I had a Calvinist interpretation, that the question was asking what proportion of the population was in the Book of Life.

I answered 0% knowing exactly what it intended and assuming that the remaining percentage chance was hell-bound, for what it’s worth.

Personally I answered 0%, as what scares me about death is the end of sentience. If hell meant losing my mind, then I would want a higher percentage. If it meant being practically immortal but having to push a stone up a hill for eternity, I could perhaps live with it.

My answers were inconsistent as you look at them because I do not expect others to share this preference.

I am an atheist btw.

Emmm.

It is very possible that removing outliers that don’t fit with your hypothesis was not the best choice.

Rationally speaking, I mean.

My assumption was that the figure was the degree of certainty that I would go to heaven, so 0% would be completely unsure whether I would go to Heaven or Hell, 100% would be something like a divine intervention telling me no matter what I’d go to Heaven, and I think I was assuming some divine declaration of probability for lower numbers.

I think I’d still take 100% probability Hell over oblivion, but it’s a much closer call than the question I thought I was being asked, although having a guarantee of some religious higher power might be enough value on its own to make it a better world.

I’d choose oblivion over a lifetime of monotony, but an eternity of pain (or possibly even monotony – if hell is an eternity of boredom I might have to rethink that question) over oblivion.

There are reasons, mainly coming down to “Pain is interesting in a way that monotony isn’t, and also eternity is a nice compensation package in any case”. I think I may have put 50% down for the “hell” question, though.

I suspect that you have never experienced truly crippling pain, to the point you cannot move at all, to the point that your brain regularly shuts down and you pass out, to the point you would gladly kill yourself if you could but you can’t even move yourself to the window ledge ten feet away. It is not interesting or preferable to monotony in any way, not remotely.

Edit: Heck, I’m just thinking of my own experiences, but honestly, I’m not even sure I’ve had the worst of it. My wife is congenitally immune to lidocaine, which she unpleasantly found out while receiving a root canal, an experience she doesn’t even remember now but I just can’t imagine how that experience, repeated endlessly, can possibly be preferable to anything, let alone monotony.

Imagine being wireheaded so that you experience pleasure so intensely you would do anything to make it stop.

What the heck does that mean? You may as well ask me to imagine a rock so heavy it weighs nothing.

@Orphan Wilde

What I think you are saying here is that you have some mental function you can run which allows you to gain positive utilons from pain and suffering. You focus on how interesting the experience is, and suddenly you don’t mind it any more.

Even allowing that ability to be effective for unending torture, I think that is fighting the hypothetical to some extant. There is the pithy answer, which is as soon as you arrive in hell, the demons snip whatever neurons allowed you to derive utilons from torture, and proceed to torture you. But even that is fighting the hypothetical.

I think that “Hell” in that sentence should be replaced with “The worst thing that could possibly happen to you, and you are allowed to violate any law of physics, biology, and neurology to make it worse”. There are possible minds in mindspace where the worst thing is oblivion, or monotony. I am very confident that I am not one of them. I am confident that nearly every evolved mind is not one of them, enough so that I assume anyone claiming that the worst possible thing is monotony or oblivion is mistaken about their preferences.

@Immortal Lurker:

Effectively, yes, pleasure and pain, as qualia, are bloody well near identical. An identical sensation can be pleasant in one context and unpleasant in another.

Cutting the neurons, or whatever, would just be a mental press on “Negative context”. And anything at all would be unpleasant with a sufficiently negative mental context. The mind control, in that context, is just a press down on a mental “Negative Utility” button. Your utility goes down; your utility multiplier on every activity becomes negative.

With that kind of mind control being applied, you could be exactly as miserable eating a tart as being tortured; physical punishment is unnecessary and pointless and subtracts from our understanding by imposing biological biases. This implies a kind of Hell far, far worse than the one Scott describes for its subjective occupants, one that would look pleasant from the outside.

So I’d be inconsistent if I preferred a happy but short life to a long but unhappy one, but preferred oblivion to hell. That’s not a good understanding of what “unhappy” is. [ETA: Preferred a long unhappy life over a happy but short one, but then also preferred oblivion to hell.]

“oblivion, or monotony.”

Not saying you did, but let’s be careful not to conflate oblivion and monotony. I’d much prefer oblivion to an eternity of monotony. In fact, one of the first ways I recall imagining hell as a child was simply being stuck in some kind of tiny, featureless room for all eternity with no way of achieving oblivion or escape. I’m not sure whether being stabbed in an immortal face by demons for all eternity would be worse; I think it might be better. Anything which offers the chance of interaction with other beings, even beings one hates, seems preferable to eternal loneliness.

Contrasted to that, oblivion is not boring. It’s just nothing. Were you bored for the billions of years which preceded your birth?

I actively dropped the question because my answer was going to be intensely hell-dependent. There are major Western religions preaching versions of Hell that I would take at a 0% chance of salvation, simply as better than nonexistence.

“Infinite suffering vs. infinite bliss” would get either 100% or 51% (infinities are tricky, not sure), “God’s grace vs. lake of fire” would invite a little more risk, and the various “outside God’s grace” or “place where you atone” hells look way nicer than nothingness.

You should have been more specific about the hell in question… Adding “Unsong’s Hell” (plus a requirement to actually read the relevant chapter, of course) to the statement of the question would have gone a long way to solve the ambiguity. I don’t believe the ambiguity with respect to Heaven is important, but given the number of people who think of Hell as “absence of God”, “nothingness”, or similar, it would have been a good idea.

My idea of Hell is something like Unsong’s Hell instead of the milquetoast alternatives, but many people seem to think differently.

Other than this, it’s a great survey, and the other questions seem unambiguous.

Not really. I can imagine someone who prefers continued existence even under torture to oblivion. And Scott’s question doesn’t even specify that Hell involves torture; C. S. Lewis’s The Great Divorce postulates a Hell mostly comprised of boredom and maybe psychological torment, while Mammon on Reddit comments that he imagines Hell as “a vacation club for people who need some amount of coercion to get along.” In either of those circumstances, I could readily imagine someone being okay with P(Hell)=1.

Disclaimer: Being myself religious, and sure (P > .99) that Heaven exists and that I’ll go there, I found it very difficult to even put myself in the right frame of mind to consider going to Heaven as a randomly-picked variable.

Can you elaborate on your religion? I am very surprised that there would be a religion that would allow you have 99% confidence of ending up in heaven. Is that because pretty much everyone does, because you are in some way very special or some other mechanism? Are there really no bad life choices open to you that give more than 1% probability of not ending up in heaven?

I can’t speak for Evan, but I also have a >99% certainty I’ll go to heaven, and I’m reasonably sure Evan has the same religion as me. Your question about if there’s any act I can do that would lead me to not go to heaven is coming at the issue backwards. It’s the fact that I will go to heaven that keeps me from doing bad things. God saves by grace through faith, and it’s being saved that causes you to take good actions, not the other way around.

That gives you P(heaven) > 0.99 conditioned on you actually being saved, but why should the probability that you’re correct in believing yourself to be saved be 100%? Surely, some people have believed this but were later proven wrong. It’s not completely impossible you’re such a person.

Well, I’m a Christian, and the Bible talks about exactly this in a couple places. One place is 2 Peter 1:

There’s a lot to talk about here, but I want to point out that it’s an example of what I said before: doing good things isn’t what sends you to heaven; being on your way to heaven is what makes you do good things. That’s why it starts with “he has granted to us his precious and very great promises” before going on to “for this reason make every effort” and so on.

So when you ask the question, “How do I know that I am saved?” the first part of the answer is, “What does my life look like?” Does it have a pattern where I am increasing in virtue and knowledge and so on, or am I staying in the same place or moving backwards? When we read the rest of the Bible, we also realize that many of these qualities are as much internal as external. When I become more virtuous, am I also secretly becoming more prideful about it? Depending on your answer, there may be cause to examine yourself and see where you really stand.

When the Bible talks about “real faith”, it always refers to action: what acts have you taken because of what you believe? How has it made a difference in your life? If there’s not one, maybe you should look into that.

And then there’s also an ineffable quality that being saved has that being unsaved lacks. The Bible talks about how we are indwelt by God’s spirit. Slowly you begin to see changes in yourself. Slowly you become more aware of spiritual truths. Slowly you begin to see a spiritual dimension to events that doesn’t diminish any part of the physical reality. Never bright lights or fire from heaven, but a definite push towards certain things and away from others. A growing hatred of wrong and a love of what is right; a growing ability to see good and evil in starker contrast, a growing vision of both how the world is broken and what the world redeemed will be like. Something inside you has changed, and you have a sense of both yourself broken and yourself set right again. You read the Bible or hear it preached and suddenly words that never made sense to you before fit together perfectly, and you see how obviously it was true all along. You live life but not for life; you learn how to smile in suffering, you learn how to say “I was wrong” and “I’m sorry”; you learn how to make peace and forgive. Each individual step always seems perfectly natural. It’s only when you look back that you see God was with you all along.

So if you ask me how I know I’m saved- well, I know it as I know most anything else I’ve known for sure. I’ve been there. I’ve walked through it and stood beside it and laughed and cried and screamed over it. And maybe that’s not a knowledge I can communicate to someone else. Maybe the path I’ve walked isn’t one I can share. But I look into myself and when I see light it is light shining in from outside, and the only choice worth making is kneel before the One from whom that light shines.

How do you know anything else for sure?

Knowing something always includes at least the possibility that you’ve made mistakes or rationalizations. Are you claiming that religion is something about which it is impossible for you to have made mistakes?

@Jiro

Going to borrow a phrase from a different Scott A. – the way I read this is that Two believes that his religious beliefs are sanity-complete: sure, he could be rationalizing them or outright wrong, but he could also be a brain in a vat in a universe where 1 + 1 = 7; his priors on further exploration of the topic resulting in a change of opinion (or of action) are indistinguishable in practice from zero (or whatever his minimum value is for priors).

Whether or not this is actually the case, well, that depends on which definition of “knowledge” you’re using.

What Jiro said. I don’t know a single thing with 100% certainty. I mean, I’m infinitesimally close on “other people exist” and “the sun will rise tomorrow,” but metaphysical propositions on which all of humanity has had widespread disagreement throughout its entire history? I don’t think you’re calibrating properly.

Well, of course making mistakes is also possible. But my past experience in correcting mistakes has been less like exchanging geocentricism for heliocentricism and more like exchanging Newton for Einstein, if you understand my meaning. Most changes of opinion aren’t about overthrowing existing beliefs but about subsuming existing beliefs. In other words, there’s a discernible process by which beliefs level up, in which they gain not only greater explanatory power, but also a kind of aesthetic beauty. To change my beliefs, I need to be shown that the change in beliefs has this “level up” quality, and while Eilezer’s version of atheism is indeed very powerful and very aesthetically pleasing, it is not quite up to the level of my current set of beliefs. I think I can explain Eliezer, but I do not believe that he can explain me. “Sanity-complete” is a good way of putting it, if possibly an undersell.

And of course there is the part that comes from living it all, which isn’t easily communicable.

If doing good from within is a sign of being saved, what does that say of athiests and followers of other religions that do good things – or even great (both in the large sense and the positive sense) things?

@Cypher – “If doing good from within is a sign of being saved, what does that say of athiests and followers of other religions that do good things – or even great (both in the large sense and the positive sense) things?”

…Nothing? Doing good out out thankfulness and a desire to more closely emulate God is one reason to do good. there are others as well. The good done isn’t an entry on a ledger.

@Adam – “What Jiro said. I don’t know a single thing with 100% certainty.”

Sure. But one of the specific instructions, as I understand it, is to not freak out about going to hell. Like, worrying about going to hell if you do it wrong is itself doing it wrong. You are guaranteed not to be doing it right, and you can and should make every effort to do it less wrong, but there are no points, there is no pass/fail threshold. It’s a relationship, not a test. Hence the stuff about Grace and Faith and so on; if God promises you that you’ll be fine if you trust in him, either you trust him and everything’s fine, or you don’t believe him, and then it’s easier just not to believe IN him, and then what’s the problem?

Dude, the entire point is everything you said is one possibility. You stated it as if it is the absolute truth. Of course if it’s the absolute truth, then you’re good to go, no danger. Assuming that to begin with, and then using that assumption to justify your belief that you’re going to heaven, is question-begging.

That sounds to me like quite some confidence. I agree with Koldos in being curious as to how you get so high a probability.

I mean, my own estimate of the probability of Heaven as traditionally described actually existing is about as close to zero as yours is to 1, but if I thought that there was a Heaven with your level of confidence, my probability estimate of ‘and I will go there’ would be much lower. Roughly, if I thought that it was at all likely that we lived in a universe with something like one of the Abrahamic gods behind it, I would be terrified of going to Hell for choosing the wrong religion, because if I was a mainstream [Christian / Muslim], the existence of a billion-plus [Muslims / Christians] would be proof that billions of people can believe something catastrophically wrong with just as much intensity as others can believe something true, with the decision largeley predetermined for you by your upbringing, before you even get into ‘actually, neither of the above; some other existing religion, or even one that doesn’t exist yet, is true’ territory (or ‘one specific denomination or subgroup is true’).

So I’m curious as to how you get from the high confidence that there is a heaven, to the comparably high confidence that we don’t live in a universe that has a hell as well.

Disclaimer: Although Catholic, I am not the Pope, and therefore cannot speak for official Catholic doctrine. What I write below is an attempt to explain a concept I’m a little fuzzy on myself in modern terms. Further, the ideas of Heaven and Hell are so distorted by being wrapped in parables, metaphors, and Dante’s later allegory that we can’t know what God has in mind.

My understanding is that Catholic theology posits a third option, Purgatory, which can be likened to Temporary Hell Lite or Club Fed Hell (as opposed to Maximum Security Regular Hell). If you’re bad but not irredeemable, you end up spending a lot of time (which is subjective, considering we’ve passed out of time entirely at this point) coming to understand what you did wrong, then you get moved on to Heaven. So it’s easy to think that most people will end up in Purgatory if you think people as a whole are generally good.

Catholic theology got tripped up at some point by people asking about the extreme edge cases, people who were incredibly incredibly good people in life who may have lived in times or places where they never could have even heard of Christianity, or people that were not Christian but were innocent enough to be incapable of being evil, such as the really really young. There seems to be general agreement that whatever happens in these cases, it isn’t bad. Dante included a ‘good-but-not-Christian’ section in Hell in his Inferno in the form of Limbo.

That causes me to wonder how it is possible, given infinite time, for a person to be completely beyond any future hope of redemption. Surely some extremely long but finite period of suffering is sufficient punishment for any finite crime.

Pretty sure some of those people are members of the Invisible Church.

Punishment is only half the issue. Heaven is a place where everybody always picks cooperate over defect. You’re asking how long they need to be punished for defecting, when really we want to know what it will take for them to go and defect no more.

And Presence charms requiring more Willpower points than you have to resist is not the answer.

Jask, you just said heaven is a place where everyone always chooses cooperate over defect. 1) No person’s willful choices are ever guaranteed to be stable for an infinite period of time, so you can never guarantee this for any person, even if they managed to never defect while spending several decades alive on earth, and 2) if heaven is like this because everyone always cooperates without having to choose, then you can guarantee a person will always cooperate by simply putting them in heaven.

That causes me to wonder how it is possible, given infinite time, for a person to be completely beyond any future hope of redemption. Surely some extremely long but finite period of suffering is sufficient punishment for any finite crime.

I was once in a fantasy PBEM game where you play a Greek-style deity in charge of a group of followers, and the game left me with a theoretical question that occasionally, on those dank, sweaty summer nights, keeps me awake.

To translate it into understandable terms, imagine a proposal for justice reform: we build a secure and isolated prison in the middle of nowhere, and when we say we execute someone, we just fake their death and put them there. Criminals still fear the death penalty, but there’s no actual risk of killing an innocent person. If we find we’ve accidentally put away an innocent person there for a capital crime, we give them a ton of money and put them in a witness protection program. Since we’re human, we obviously can’t make this work perfectly, but if we could, would it be better than the system as it is now?

To me, yes, of course that would be better. To someone who thinks a proper purpose of the criminal justice system is to actually dole out punishment in proportion to offense and just to aid other lines of effort in reducing the treat and occurrence of crime, the answer might be no, it’s better to actually kill people even if some of them are bound to be innocent.

What percentage of people need to receive the maximum punishment for a crime for that punishment to be effective?

In this case, we have a crime, and we know the range of punishments the judge is allowed to give out, but we don’t know what sentence previous defendants received. In order to reduce crime, it’s in the judges best interest to make sure people know what the maximum sentence is, regardless of how often that sentence is given out.

I’ll freely I’m no criminologist, but I was under the impression that the best empirical evidence suggests that sentence severity has almost no deterrent effect anyway. The perceived likelihood of getting caught and punished at all does, though.

The classical, allegorical definition of God, heaven and hell, postulates a 100% chance you will get caught. To human minds, when dealing with the infinite afterlife, the punishment as far as we can understand it effectively amounts to either ‘slap on the wrist and time served’ or ‘death penalty’. If you want to reduce crime, I think this is one point where you’d play up the greater potential sentence.

Well, the key thing is believing there is a 100% chance of getting caught. So between non-believers and indulgences, that wasn’t necessarily the case. God could have smartly invested effort into presenting convincing evidence of the truth of his word and not allowing it to be presented through corruptible priests.

“My understanding is that Catholic theology posits a third option, Purgatory, ”

Purgatory is not a third option. It’s the ante-chamber to Heaven. If you made it to Purgatory, you’re saved. You’re just getting clean before you make your entrance.

“No person’s willful choices are ever guaranteed to be stable for an infinite period of time, so you can never guarantee this for any person, even if they managed to never defect while spending several decades alive on earth, ”

No person ON EARTH.

The Afterlife is a different mode of existence, possibly not even involving being related to time in the same way we are now.

Well, the key thing is believing there is a 100% chance of getting caught. So between non-believers and indulgences, that wasn’t necessarily the case. God could have smartly invested effort into presenting convincing evidence of the truth of his word and not allowing it to be presented through corruptible priests.

Without getting too much into the early history of the church, which, admittedly, like all human things is necessarily imperfect, this isn’t how Catholics see it.

Nobody is perfect. We all make mistakes. To a Catholic, we are all sinners, because we all have moments of pride, lust, greed, etc. Being good just means you handle that better. It’s like someone that escaped from prison and lived his life as a model citizen; he’s still guilty of the original crime, but his subsequent behavior earns him leniency from the judge. (Indulgences were more ‘I was a great guy before I robbed the bank, so go easy on me.’) With non-believers, you may not know what Christian teaching says, but you still have a sense of right and wrong.

As far as the whole Babelfish paradox goes, I have my own theories, but they are a product of my own odd internal logic.

Purgatory is not a third option. It’s the ante-chamber to Heaven. If you made it to Purgatory, you’re saved. You’re just getting clean before you make your entrance.

We’re dealing with analogies to something unknowable. Purgatory is a third option if the only two options presented are ‘go directly to heaven’ and ‘go directly to hell, do not pass go, do not collect $200’.

When discussing criminal justice, if we’re comparing ‘prison’ and ‘not prison’, ‘probation’ is covered under ‘not prison’, but it also seems useful to distinguish between ‘not prison – free’ and ‘not prison – probation’.

Yeah, but “non-believers” includes non-Catholics. Obviously, hell can’t serve as an adequate deterrence for them if they don’t believe it exists.

Yeah, but “non-believers” includes non-Catholics. Obviously, hell can’t serve as an adequate deterrence for them if they don’t believe it exists.

You’re not a believer and you know about hell. That’s why most Christians are called to evangelize (which does not perfectly overlap with Evangelical Christians).

As far as believe, that gets into the Babelfish Paradox mentioned above. (Short version: it’s possible to set up a God where he can’t prove he exists.)

Yeah, of course. I guess the Franciscans are distinct from what we’d call “evangelicals” and the process by which they made my ancestors Catholic was not a pretty process, though I guess it illustrates the idea to turn life itself into something like hell.

But still, I don’t see how knowing some people believe in hell is supposed to serve as a deterrent to me. Even though Buddhists don’t really evangelize, I’m sure you at least know of Dharma, but the prospect of being reborn as an untouchable probably isn’t what keeps you from being a jackass in this life. They know about hell, too, but it doesn’t motivate them.

I’m a religious Jew and I also had a very hard time answering, because Heaven/Hell dichotomy doesn’t make much sense to me and I had to guess what Scott was intending. I ended up answering ‘100%’ after trying to translate the question in terms that I can actually relate to. Let’s put it this way: I have a high confidence that if there are consequences for our actions after death, that it derives from the parameters of my own religion’s most consistent and reasonable (and rationalist?) sensibilities and is just, and basically doesn’t have anyone ‘going’ to a Christian-esque version of Hell, and neither to the Christian-esque Heaven (but with basically everyone having a limited-time experience comparable in a limited way to ‘purgatory’ – an experience that is not pleasant but not comparable to Hell). If not this – if my own religious beliefs are fundamentally untrue – I expect that it is definitely the case that no religious outlooks are true and thus the after-life outcome for everyone is oblivion. I’d rather oblivion than unjust afterlife consequences for my or others’ actions, and I require 100% confidence that the afterlife consequences are just.

I’ve never understood the “Muslims don’t worship the same god as you”! argument. I mean, it boils down to, “There are a bunch of people who disagree with you, now what?” Well, okay. There are lots of people who disagree with me on every conceivable topic, not just religion. That doesn’t stop me from holding an opinion in those areas; why should it stop me here?

It shouldn’t stop you from holding opinions. It should stop you from being 100% certain you’re correct about them. Arguably, most of your opinions can even be held with P(correct) < 0.5 if you're choosing from more than two disjoint possibility subsets, as is the case when choosing a specific religious particularism.

Adam already answered this one well. But to be specific, if you think that a heaven exists, the number of people who agree with you that a heaven exists is vastly higher than the number of people who agree with you about exactly what it takes to get there. And from the outside, the people who disagree with you about that seem to believe their versions about as passionately, and with about as much good evidence, as the people who agree with you. Some of them even hold that what you think is necessary to get to heaven is in fact guaranteed to prevent you getting there.

Therefore your probability estimate of a heaven existing should be significantly higher than your probability estimate of you personally getting to go there.

Evan Thorn seems to have p(a heaven exists) ≈ p(a heaven exists and I personally will go there), which is a level of confidence that needs some explanation.

I think that characterization of the problem relies on some pretty big (and completely unfounded) metaphysical assumptions, personally, but I can see that perspective, I suppose.

You essentially must consider the possibility that some third factor is making both groups believe, such as an innate human propensity to religion.

Or, much less charitably, if you know it’s possible to make a mind control ray, even if it’s imperfect, you must ask yourself if such a device has been used on you already. Certainly, we can observe some political ideologies massively distorting peoples’ worldviews into nearly-inescapable spirals that they are willing to die for.

I don’t know. I took the survey and put my required odds of heaven at about 5%.

Here’s the thing: while I can sort of maybe make peace with my personal oblivion, the notion that eventually all humans everywhere will dissolve into nothingness fills me with utter horror. I absolutely prefer a universe with Hell to a universe with Nothing. If the universe also happens to contain Heaven, and lots of people are there, then so much the better.

I think this might be endemic: People profess to prefer Hell to Oblivion, because they prefer to believe in Hell rather than believe in Oblivion.

Suppose that you cannot change your beliefs nor the beliefs of anyone else. Keeping your expectations up until the point of death constant, would you prefer oblivion or a hell created by a competent entity with the express purpose of making the afterlife worse than oblivion?

I would, and do, prefer oblivion to a Heaven or Hell. A deity that created a world of such needless suffering and demands that we worship and obey it for all eternity or we will be punished for all eternity is not a deity that I would serve. To that capricious, unworthy deity I say, “non serviam.”

What if no deity, just Heaven and Hell for pure physical reasons and a quantum random number to decide where you’d go.

To me, this seems like freely choosing a death sentence because you think the judge is an arsehole, even when you have a get out of jail free card. If the hypothetical judge IS actually an arsehole, he doesn’t really care that you’ve been executed, so it’s a bit pointless.

Ew, I have to reply to myself to reply to you…

Vamair said:

“What if no deity, just Heaven and Hell for pure physical reasons and a quantum random number to decide where you’d go.”

If there were a way to rig the game, I’d likely choose the supposedly better option. If not, I’d take oblivion, after all, I wouldn’t be around to care.

Eh said:

“To me, this seems like freely choosing a death sentence because you think the judge is an arsehole, even when you have a get out of jail free card. If the hypothetical judge IS actually an arsehole, he doesn’t really care that you’ve been executed, so it’s a bit pointless.”

Except it isn’t the choice between do what you want or be executed, the choice is worship the arsehole judge for eternity, or be executed. A cage is still a cage, no matter that it be appointed with silk sheets and jewel encrusted bars. Besides, if there is an omnipotent, omniscient deity, it would certainly know what I think of it and its shoddy work, and I’m pretty sure that’s on the no-no list of all the Abrahamic religions and their various offshoots. Which, I’m assuming are the versions of heaven and hell on offer.

Exactly!

Actually, doing what you want to do is a form of worship.

Can you elaborate on that?

I get the impression that there is a fair bit of typical mind fallacy going on between instinctively religious and instinctively non-religious people – I’ve often heard it claimed that atheists ‘worship themselves’ or ‘worship science’, or such like, from people who, I suspect, simply cannot imagine what it feels like from the inside to just not have any inclination to worship anything, and therefore cast around to see what it is that the atheists worship if they aren’t worshipping any gods.

And from my own perspective, I can’t be sure, but I suspect that one of the factors contributing to me growing up to identify as an atheist was: why would a god which wanted us to worship it design our brains in such a way as to find the act of worshipping it so mind-numbingly boring? – I was unable to wrap my head around the idea that some people actually enjoy praying and church rituals.

I hope I am not being too uncharitable in suggesting that, in calling ‘doing what you want’ a form of worship, you may be using an unnaturally expansive definition of ‘worship’ that doesn’t actually map onto what we normally consider the word to mean, or onto anything the people doing what they want are actually feeling from the inside.

Perhaps you underestimate peoples capability for self sacrifice? What if somebody believes that:

* They currently live in the universe where heaven and hell don’t exist.

* If they did most people would go there but they personally wouldn’t.

* The universe where heaven and hell exist is better than the one where it doesn’t, in pure utilitarian terms.

So they would be willing to take on the personal sacrifice of eternal damnation so that others can live in heaven. We have an entire mythology surrounding a person who is revered for having done just that, so it’s not inconceivable that there are others who would be willing to follow his example.

The first part of the survey, not included in this post, is the disclaimer: