[Epistemic status: uncertain. Everything in here seems right, but I haven’t heard other people/experts in the field talk about this nearly as much as I would expect them to if it were true. Obviously amount of variability attributable to environment (shared and non-shared) increases as the variability in environments in the sample increases]

The “nature vs. nurture” question is frequently investigated by twin studies, which separate interpersonal variation into three baskets: heritable, shared environmental, and non-shared environmental. Heritable mostly means genes. Shared environmental means anything that two twins have in common – usually parents, siblings, household, and neighborhood. Non-shared environmental is everything else.

At least in relatively homogeneous samples (eg not split among the very rich and the very poor) studies of many different traits tend to find that ~50% of the variation is heritable and ~50% is due to non-shared environment, with the contribution of shared environment usually lower and often negligible. This is typically summarized as “50% nature, 50% nurture”. That summary is wrong.

I mean, it’s tempting. All these social developmentalists were so sure that the way your parents praised you or didn’t praise you, or spanked you or didn’t spank you, had long-lasting repercussions that totally shaped your adult personality. The underwhelming performance of shared environment in twin studies torpedoed that whole area of study. But at least (these scholars of social behavior could tell themselves) it provided a consolation prize. The non-shared environment contributes 50% of variation, just as much as genes. That means things like your friends, your schoolteachers, and even that time you and your twin got sent away to separate camps must be really important. More than enough there to continue worrying about how society is Ruining The Children, right?

Not necessarily. Non-shared environment isn’t really “non-shared environment” the way you would think. It’s more of a dumpster. Anything that isn’t genetic or family-related gets tossed into the non-shared environment term. Here are some of the things that go into that 50% non-shared environment:

1. Error. Measurement error is neither genetics nor family, so it ends up in the non-shared environmental term. Suppose you’re studying intelligence, and you make a bunch of twins take IQ tests. IQ tests measure intelligence, but not perfectly. For example, someone who makes a lucky guess on a multiple choice IQ test will get a higher score even though they are not more intelligent than someone who makes an unlucky guess. Someone who takes the test when they’re tired and stressed may get a lower score even though they’re no less intelligent than somebody else who takes it well-rested and feeling good.

Imagine a world where intelligence is entirely genetic. Two identical twins take an IQ test, one makes some lucky guesses, the other is tired, and they end up with a score difference of 5 points. Then some random unrelated people take the test and they get the 5 point difference plus an extra 20 point difference from genuinely having different IQs. In this world, scientists might conclude that about 80% of IQ is genetic and 20% is environmental. But in fact in terms of real, stable IQ differences, 100% would be genetic and 0% environmental.

This gets even harder when trying to measure fuzzier constructs like criminality. Suppose someone does a twin study on criminality and their outcome is whether a twin was ever convicted of a felony. This depends partly on whether the twin is actually the sort of person with criminal tendencies – but also partly on whether a policeman happened to be in the area to catch them, whether their lawyer happened to be good enough to get them off, whether their judge was feeling merciful that day, et cetera. Imagine a world where criminality is entirely genetic. Identical Twin A becomes a small-time cocaine dealer in a back alley in West Philly, sells to an undercover cop, and ends up in jail. Identical Twin B becomes a small-time cocaine dealer in a back alley in East Philly, doesn’t run into any undercover cops, and so avoids conviction. This shows up as “variation in criminality is due to non-shared environment”.

Riemann and Kandler (h/t JayMan) run a study which is an excellent demonstration of this. Classical twin studies sometimes use self-report to determine personality – ie they ask people to rate how extraverted/conscientious/whatever they are. These studies find that most personality traits are about 40% genetic, 60% non-shared environmental. Riemann and Kandler obsessively collect every possible measurement of personality – self-report, other-report, multiple different tests – and average them out to get an unusually accurate and low-noise estimate of the personality of the twins in their study. They find that variation in personality is about 85% genetic, 15% non-shared environmental. So it looks like much of the non-shared environmental variation in traditional studies of personality was just error.

2. Luck of the draw. Bob becomes a junior advertising executive at Coca-Cola, where he designs a new ad targeting young female consumers. His identical twin Rob becomes a junior advertising executive at Pepsi-Cola, where he designs his own new ad targeting young female consumers. Both ads are very successful – in fact, exactly equally successful. But Coke’s CEO is a crony capitalist who wants to replace everyone in the company with his college buddies, so he ignores Bob’s good work and demotes him to a low-level position. Pepsi’s CEO is a skilled leader who recognizes good talent when she sees it, and she promotes Rob to Vice-President Of Advertising.

Now a scientist comes along, does a twin study on them, and finds that they have very different levels of income. She reports that there’s a lot of difference between these two identical twins, so much of income must be non-shared environmental.

Science reporters read the study finding that much of the variation in income is non-shared environmental, and conclude that despite their identical genes, there must be deep and mysterious differences in Bob and Rob’s abilities and business acumen. They speculate that Rob had a very inspirational teacher in school who pushed him to achieve greatness, and Bob must have fallen in with a bad peer group who didn’t value hard work.

But actually, Bob and Rob are completely identical in every way, no incident in their past did anything to separate them, and Bob just ended up working for a crappy CEO. In this scenario, inherent predisposition to earning money is exactly the same in both twins, they just have different amounts of luck at it. If both twins become pathological gamblers, but one of them hits the jackpot and the other goes broke, that will show up as “non-shared environment” too.

3a. Biological random noise. The genome can’t encode the location of every cell in the body. Instead, it specifies high-level processes which create lower-level processes which create those cells. But this gives the lower-level processes a lot of leeway, meaning that there can be significant biological differences between identical twins.

Consider by analogy The Postmodernism Generator. It’s a cute program that will make a (sort of) convincing sounding postmodernist essay on demand. We can imagine hundreds of different programmers all designing their own postmodernism generators. Some would be really brilliantly designed and consistently come up with plausible looking essays. Others would be poorly designed and consistently come up with crappy essays that don’t convince anybody. But there would also be variation within the results of each generator. There might be a generator that is mostly terrible but occasionally by coincidence comes up with a really funny essay, or vice versa. In this analogy, the genes are the code for the generator, and the person is an individual essay produced by that generator.

Thus, identical twins have different fingerprints, different freckles, and different birthmarks. Only about a fifth of left-handers’ identical twins will also be left-handed. And twins even look different enough that their friends and parents eventually learn to tell them apart. All of these are non-genetic issues likely to show up in “non-shared environment” but not related to schools or peers or “nurture” as traditionally conceived.

3b. The immune system. Immunology is still poorly understood, but it seems very important. Immune reactions and neuroinflammation have been implicated to one degree or another in a lot of psychiatric diseases. A functional immune system can protect good health; a dysfunctional immune system can make someone constantly tired and miserable.

There seems to be more of an element of chance to the immune system than to a lot of other bodily processes. Part of it is the input – one child in a twin pair might inhale a particle of cat dander at a critical time; another might get some unknown adenovirus with no immediate effects but which contributes to obesity twenty years later. Another part is the output; sometimes a natural killer cell stumbles across something quickly and takes it out without any fuss; other times the immune system misses it for a while and it gets more of a chance to spread.

The end result is that immune-system-related-conditions are really discordant across identical twins. If your identical twin has asthma, there’s only a 33% chance you’ll have it as well. If your identical twin has Crohn’s disease, a disabling autoimmune intestinal condition, there’s only a 50% chance you’ll suffer the same. I’m not sure how significant this is in the broad scheme of things, but I suspect more so than people think.

3c. Epigenetics We know that identical twins have substantially different epigenetics, and there are hints that this underlies discordant behavior. This is probably really important, but I feel bad bringing it up because it seems to be passing the buck. We usually think of epigenetic differences as a response to different environments or life choices. But if identical twins start with the same environment and can be expected to make the same life choices, why do they end up with different epigenomes? I’m not sure what to do with this one.

3d. Genes that differ between identical twins. Apparently this happens! Identical twins come from the same zygote, which means they start out with the same genes, but after that all bets are off. If there’s a mutation in one twin in the first embryonic division, then half of that twin’s cells will carry that mutation. Remember that there are a lot of divisions and opportunities for mutation before any cells even start forming the brain, and any mutation before that time could be transmitted to all brain cells. One study found that the average identical twin pair probably has about 359 genetic differences occuring early in development.

I’ve grouped 3a, 3b, 3c, and 3d together as possible biological sources of variation. One of these – or maybe some 3e I don’t know about – is probably the reason for less-than-perfect twin concordance in conditions like Parkinson’s disease, migraine, autism, and schizophrenia. Needless to say, anything that can make you schizophrenic can probably affect your personality and life outcomes pretty intensely.

But all of this gets counted as “non-shared environment” in a twin study, and used to play up the importance of schools and peer groups.

4. Actual nurture. Twins do have different experiences growing up. How much does this shape their adult traits? Can we separate this out in to specific experiences that shape adult traits, like school and summer camp?

The good news is that Eric Turkheimer has a big review article on this; the bad news is that the discussion section is called “The Gloomy Prospect” and says:

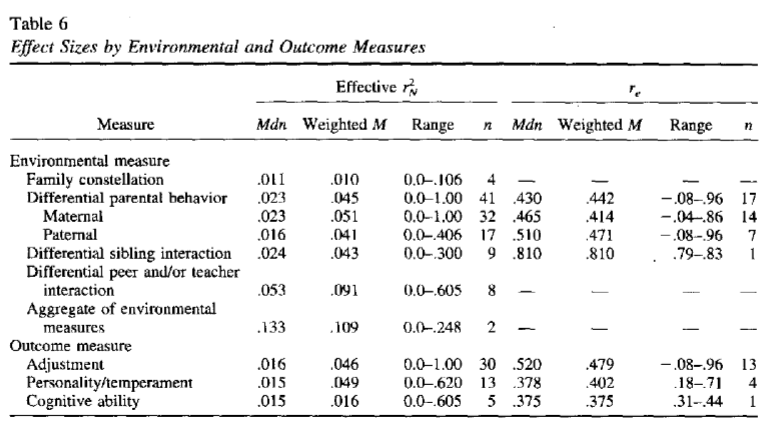

Quantitative analysis of studies of specific nonshared environmental events shows that effect sizes measuring the effects of such variables on child outcomes are generally very small. Effect sizes are largest when confounds with genetic variability and outcome-to-environment causal effects are not controlled. When such confounds are controlled, as in the most recent reports from the NEAD project, effect sizes become smaller still.

I’m not sure if this table represents the “very small” uncontrolled or the “smaller still” controlled sizes

The paper concludes: “We emphasize that these findings should not lead the reader to conclude that the nonshared environment is not as important as had been thought.”

But although I have a huge amount of respect for Turkheimer, I kind of want to conclude that the nonshared environment is not as important as had been thought. My guess is that the nonshared environment as Turkheimer discusses it – differential parenting, schools, peers, and so on – is only a fraction of the “nonshared environmental” term in genetics studies.

If that were true, it would mean that nature is more important than we thought relative to environment in terms of things we can understand and possibly affect. That would make the quest to change important outcomes like intelligence, personality, income, or criminality by changing society even more daunting. And it would make the opportunity to change those outcomes through genetic engineering even more tempting.

IQ tests measure intelligence, but not perfectly. For example, someone who makes a lucky guess on a multiple choice IQ test will get a higher score even though they are not more intelligent than someone who makes an unlucky guess. Someone who takes the test when they’re tired and stressed may get a lower score even though they’re no less intelligent than somebody else who takes it well-rested and feeling good.

Also, experience with the test. Retaking the SAT was generally worth about 150-200 points out of 1600, just because people better used their time and weren’t thrown by the questions.

Classical twin studies use self-report to determine personality

Isn’t self-reporting thought rather poorly of, especially for things that aren’t extremely concrete?

Are you sure? According to here retaking the SAT is worth 10-20 points out of 1600

But those taking the exam five times improved their score by 83 points out of 1600 between the first and last time (see Table 2).

Having taken the SAT, I would feel no surprise concluding that

(A) There’s at least 83 points worth of very studyable/practice-able material in the exam,

but I’ll rule out other explanations first.

Maybe

(B) People get (anywhere close to) 83 SAT-points smarter between Junior and Senior years.

However, looking at Table 6, the time gap between tests doesn’t matter (with the exception that those with only a summer vacation between tests improve slightly less), and people retaking only once show much smaller gains.

Of course there’s also

(C) Students retake tests because they screwed up the previous time(s),

but this effect should be negligible because the mean improvement between “1st time” and “2nd time” looks independent of the number of tests eventually taken.

So it looks like those 83 points come mostly from practice with the SAT and studying. Anything I’m missing?

(Note: I’m writing this primarily for people considering taking the test again.)

The scoring also changes from test to test based on an equating formula. Collegeboard claims that it “ensures that the different forms of the test or the level of ability of the students with whom you are tested do not affect your score”.

https://collegereadiness.collegeboard.org/sat-scoring-before-march-2016

During one test you may get 2 questions wrong and get a 750 while in another you may get 2 questions wrong and still receive a 790. That’s a pretty massive point difference for a top scorer and is a strong incentive to retake the test and maybe get a lucky answer (or hard question that just happens to be right up your alley) on one of the retakes so that you get bumped up to an 800.

For repeat test takers not trying to get a perfect score there’s also the incentive to learn to avoid harder questions and leave the answers blank since a blank doesn’t harm your score as much as a wrong answer. This is a learned skill that someone unaccustomed to it likely isn’t going to pull off as well on their first attempt at it (and if you’re that smart and naturally talented you likely don’t need the mechanic’s assistance that much).

>there’s also the incentive to learn to avoid harder questions and leave the answers blank since a blank doesn’t harm your score as much as a wrong answer.

Sort of, not really. Sure, a blank is better than a wrong answer, but the expected value of a random guess is the same as that of leaving it blank, zero, because you get 1/4 point off for a wrong answer, but will, on average, get one answer in five right.

Of course, it’s not truly random, and test-takers could be subject to a bias–most SAT verbal questions have intentional red herrings designed to catch students relying too much on key words, for example, so it’s not impossible for someone to consistently perform worse than chance. But overall, I expect savvy-ish guessing to have at least a small positive expected value on average.

Yeah, to be honest, I’m not sure why they’re moving away from the wrong-answer penalty.

It made sense: the problem is that in a regular test, you have a strong incentive to bubble in all the answers even if you don’t get time to even look at all of them (and they are designed to do this). The penalty makes it, on average, just the same if you don’t randomly bubble in as if you do.

@TheAltar (did you see that pun coming when you picked your name?):

This is an important point, and I have the interesting suspicion that it affects people very unequally. Presumably variance has a bigger impact at the high end of the test than the middle (both from statistics, and because 750 vs 790 looks like a bigger change than 550 vs 590). And, presumably, this creates larger risks for certain populations.

If you’re an Asian student applying to Princeton based on your academic strength, those 40 points at the high end could make a massive difference. If you’re a non-Asian student applying to [Midtier College Here] on your athletics and charity work, you’re going to feel it a lot less.

Some of that is an obvious “insight” (students counting on academics care more about the SAT, duh), but it is interesting that scoring variation should matter more to groups on the edges of the exam.

@anodognosic:

The “equal value” claim is also ruined by the fact that SAT consequences are thresholded, rather than just a skill assessment. (As always, if you incentivize something it ceases to be an accurate metric.)

Students who’ve done practice tests can game the system by knowing what scores their desired colleges expect: low-average students should increase variance, high-average students should decrease it. Further, all students have some incentive to increase variance the first time around: if you score badly you can always retake, but if you score well you can submit that alone and look great.

Also, it takes specific knowledge of the test scoring to know when to answer if you’ve been able to eliminate some of the answers to a question, but you don’t have it down to one answer you’re sure of.

Here’s another of those vaguely remembered things seen on line– that oddly enough, the people who did worst on the math section of the SATs are those who were never taught the material in high school.

On the quarter-point penalty, it always made sense to me, not only because it evened out the expected value of guessing and skipping (instead of infinitely privileging guessing), but because I think it encouraged even a minimal amount of trying. Even if you are able to eliminate one wrong answer, your expected value is now positive.

Now of course, eliminating choices would still benefit you if guessing had no penalty, but the penalty reduces the effect of random luck and, at least I hope, gives test-takers a clear choice of which action to take based on their level of confidence (which should reflect their reasoning ability). This might be the sort of thing anodognosic is referring to when they say “savvy-ish guessing,” and I do think it means something (at least being able to filter out obviously wrong answers, or in math questions, working through some of the steps, if not all, to eliminate now impossible answers, etc.).

Now students will be incentivized, with five minutes left, to fill in A/bubble in an obscene picture/etc. for all their unanswered questions, introducing noise that will reduce the difference between test-takers at different ability levels.

@ Zaxlebaxes:

Maybe I’m missing something, but I don’t see how the wrong-answer penalty encourages trying.

You have, on average, the same incentive either way to eliminate wrong answers and make better guesses.

The only thing it does is reduce noise and luck. And increases the range of scores by eliminating the ~20% floor.

So why does the literature show gains from tutoring/test prep well below 83 points? Maybe the true amount is 83 points but only for those dedicated enough to work their asses off for a whole year+ taking the test over and over again? Or maybe the people taking the test 5 times have some selection bias, maybe they are lower scorers with more opportunity to improve or something?

To me, the obvious guess would be that people with such a high number of retakes don’t offer a random sample of initial scores. If you get a 600 and expected a 700, you retake. If you expected a 500, you don’t.

Even across many retakes, you presumably quit if you get a high score you’re happy with. Some people will be misjudging themselves and won’t ever improve, but the people who really did screw up the exam last time will have a strong incentive to retake.

Nor is that the only sample bias we might be seeing. Perhaps weak test-takers get stressed out and bomb, then slowly improve as they become more comfortable over retests. Perhaps students who get tutoring are particularly unlikely to improve, because they come from rich, academics-promoting families and have already gotten most of the studying/test skills gains available to them before tutoring (anyone know how free SAT prep for troubled students compares to paid SAT prep for rich ones?)

In any event, my best money is on massive sample bias between those two groups.

I’ve never really understood why the SAT wouldn’t respond to studying. I tutor the SAT, and I see people improve all the time. I’ve even improved my own already high scores over the time I’ve been tutoring.

The reading sections can be hard to improve, but the math and grammar sections both depend pretty heavily on having specific knowledge that can be taught. I have an ACT (not exactly the same as the SAT, but very close) student right now who improved his score noticeably just by learning the rules about commas and semicolons.

Because the SAT is (supposed to be) an aptitude test, and hence acts on the assumption that everyone taking it has been taught the appropriate skills. Given that everyone has been taught the necessary material, scores on the SAT should relate directly to aptitude/IQ/intelligence. When that assumption is not valid, you can have very strong gains from learning some fundamental skills. (E.g., in extremum, non-English speakers will do very badly on the SAT regardless of how intelligent they are.) But if the basic skills have already been taught, then there’s very little more to do other than teaching how the test itself works, which doesn’t affect scores much.

I feel like the ACT is a more straightforward “knowledge test” than the SAT, which is full of trick questions and things that lead you off down the wrong path.

Particularly in their respective math sections. The ACT just gives you a list of straightforward math problems and asks you to solve them. Many of the SAT ones, in contrast, are deliberately misleading.

Math was my weakest part on both, but I did significantly better on ACT Math. As I recall, 32/36 on the ACT Math and mid-to-upper 600s on the SAT Math. I applied to college with my ACT scores, along with some SAT IIs (I think US History and…Biology? Looked it up: US History, Molecular Biology, and English Literature) and APs.

Caethan,

I agree, but very few people taking the test actually have all the appropriate skills. If you had 100% of the necessary knowledge for the grammar section, you should be able to get a virtually perfect score. If you read a lot, you’ll have better intuition about which answers sound correct, but ultimately it’s about knowing the rules, either explicitly or intuitively.

The math section is somewhat more aptitude dependent, but most people still don’t know all the necessary skills. Even beyond that, it’s helpful to learn how to solve specific problem types. I’m good at those kind of tests partly because I’m smart, but also because I’ve seen most of these problem types before, and I already have a decent idea how to solve them.

However, looking at Table 6, the time gap between tests doesn’t matter, and people retaking only once show much smaller gains.

People who show a very small gain after retaking once don’t take it a third time?

I had some involvement with the redesign of the SAT a few years back and as I recall, the rule of thumb when “scaling the SAT and PSAT was that each year of the test takers age (maturation+education) within the age range of high school was expected to result in a 100 point gain in their score. Thus the SAT and PSAT were scaled to each other such that a student taking them simultaneously would be expected to get ~200 points higher score on the PSAT, since that test is designed to be taken at the end of 9th grade or beginning of 10th grade while the SAT is expected to be administered in late 11th or early 12th grade. A student taking both the PSAT and SAT at the normal ages is thus expected to get similar scores. A student taking the SAT twice a year apart would be expected to gain 100 points between scores.

This doesn’t mean that the variance is necessarily due to education or study and isn’t inconsistent with the SAT basically being an IQ test. As I understand it, clinical IQ test results for children and youths are normed according to the test takers’ age during scoring, while the SAT is not.

“A student taking the SAT twice a year apart would be expected to gain 100 points between scores.”

Hard to do if the score the first time was over 700 (I assume your gain is on each test, not on the sum).

Do you know if the norming of the PSAT was done the same way fifty+ years ago? I’m pretty sure my score went up from the PSAT to the SAT.

Makes sense, anyone smart enough to understand the broad meta-textual of the SAT, are likely smart enough to understand a few reading comprehension questions.

I just took the SAT recently (I’m a senior in high school now). I took it a year ago in December without studying at all and again last May after doing 3 practice tests the week before. The first time I got a 2170, the second time a 2250. I improved by 20 points in both Math and Reading and 40 points in Writing for an increase of 80 points overall. I also did far lest test prep than most other people at my school who retook the test. But this of course is in the 2400 scale, not the 1600 one, so the scoring may not be very comparable.

I was an example of factor#1 – tired/stressed versus well-rested:

The morning of the SAT I was sick with a cold so I took an antihistamine which made me groggy such that I was literally falling asleep at my seat during the test. So when I retook the test the score went up by over a hundred points (“Math” went from 720 to 800; “Verbal” improved by a more modest amount).

I went the other way. Time #1 I was out till 3 am and up before 7 to take the test. I took naps in between the sections, I scored 20 pts higher than my retake.

Speaking of which, this might be a good place to ask: I could swear I once read about a new technique for getting a measure of infections one has experienced over a lifetime, so you could see person A had had 10 serious infections and person B had had 20, and that this was applied to identical twins, showing that they often had very discrepant viral loads and this was probably a decent part of non-sharedenvironment. But I couldn’t remember any of the details and when I went looking for it a few months ago, I couldn’t find it after hours of searching, and it’s been bugging ever since. Does this ring a bell for anyone?

Not sure how new it is, but you can get a decent record of your history of infections by looking at the frequencies of the major types of antibodies in the blood (IgA, IgG, IgM, IgD, and IgE). For instance, a concentration of IgM antibodies for rubella indicates a new infection, but IgG antibodies without the IgM antibodies suggests an infection in the past.

I’m way out of my depth with this biology, so you should definitely double-check for yourself.

I think this is what you are looking for.

Looks like it, thanks. I don’t see any mention of twins, though, in it or in any of the citing papers in Google Scholar. Maybe someone merely suggested that it could be used on twins and I misremembered that.

The other side is that we know that some sorts of things vary culturally, eg which language you speak, and virtually everyone in a culture picks up on them.

There should maybe be a category called “obviously environmental effects.”

So for example how well a child does math is almost entirely a function of inherent ability. The teacher makes little difference, the school little difference, mom and dad teaching you multiplication tables doesn’t matter.

So when one kid ends up much better at math than the other conclude the first kid is just better at math. However, if one kid grew up attending school and learning math, while the other worked in a coal mine, and the first ends up more numerate, you know nothing about their relative mathematical ability. Obviously.

Something that worries me is the question of how different the “non-shared” environments are. If we’re talking about siblings (as some of the studies are), they seem likely to be growing up in environments that are extremely similar. Even if they’re studying people that merely live in the same country, that’s going to be a lot of similarities. Obviously, when studying a population that doesn’t have very much variation in environment, variation in environment shouldn’t be expected to have big effects.

Siblings by definition have shared environment – that is, nonshared environment is calculated as things that differ even among siblings.

Your country point is a good one, but we often talk about eg what the US government should do to improve people’s outcomes, in which case the variation attributable to different things within a country is what we should be concerned about.

There is some evidence that environment matters more in samples including very poor people, who don’t make it into the usual studies.

Doesn’t this tell us that twin studies aren’t likely to be very good at telling us how big an effect very large differences in non-shared environment have on people?

I mean, the number of twins raised, one in poverty and the other in wealth, by the same biological parents, must be zero or very near to it.

So what exactly can twin studies tell us about how poverty affects development independent from genetics?

There are some huge identical twin adoption studies that form the basis for the study of non-shared environment.

But how much variation is there among families who adopt children? I would expect, among other things, that they would be richer than the average population.

I’ve also read that adoption agencies actually put a lot of effort into matching up adoptees with “compatible” adoptive families. If that is true, then it would seriously undermine the idea of adoption as a natural randomized experiment.

One French adoption study (not involving twins) tried to find examples of 20 trans-class adoptions but could only find 18. Their data, limited as it was, suggested that IQ at age 14 was 59% nature, 41% nurture.

I think this article would interest you: http://www.nytimes.com/2015/07/12/magazine/the-mixed-up-brothers-of-bogota.html?_r=0

Basically two sets of twins were born around the same time in a hospital in Columbia. One baby from each set was accidentally switched in the hospital. One of the now mixed set of twins grew up in not a wealthy home, but in what is probably middle or working class in Bogota. The other set grew up in a tremendously poor rural farming community, their house was basically a shack, and the closest road you could travel by car on was a 5 hour walk away. So this is basically a wet dream of a twin study. The article is pretty long, but very extensively detailed and interesting.

Much of the research for the study of these 2 pairs of twins switched in the maternity ward was done by Nancy Segal of Cal State Fullerton, who is pretty much the Twin Queen of the social sciences. If you are into twins, just look for Nancy’s name and you’ll know you’re getting good stuff.

That’s not the purpose of twin studies, the purpose of twin studies is to estimate how genetics affects outcomes independent from any other non-genetic factor (excluding non-shared novel mutations).

If you measure the income of pair of identical and fraternal twins, and find that the income of pairs of identical twins is more correlated than the income of pairs of fraternal twins, then this is evidence that there is a genetic effect on income. You can then do the math and turn these correlation values into a “heritability” measure.

“Your country point is a good one, but we often talk about eg what the US government should do to improve people’s outcomes, in which case the variation attributable to different things within a country is what we should be concerned about.”

Cross-cultural variation is really bad for anyone who wants to use studies like the one discusses in the OP as evidence for natures importance over nurture*. If the split between genes and the environment is 50-50 — or even 90-10 in favour of genes — when the difference in environment is incredibly small in comparison to variety of environments that humans actually live in, then it suggests that the environment plays a considerably larger role than genes. The cultural/environmental difference between poor Americans and rich and poor Americans, African-Americans and white Americans is minuscule compared with the difference between any one of those groups and Ancient Egyptians or a tribe living in the Amazon jungle.

You suggest the cross-cultural point is irrelevant when it comes to producing different results for people within a country. This only holds true if we limit potential changes to nothing that isn’t extremely similar to the way we’re already doing things.

*I personally think the distinction between nature and nurture, or biology and culture, is a false one but I’ll stick with the terms here for simplicity’s sake.

“*I personally think the distinction between nature and nurture, or biology and culture, is a false one”

Are you a lamarckian? You believe environment can change your genes?

Well, the environment has some impact on mutation rate. If you happen to live in a very hot area, or very radioactive area, you’re going to see more random mutation.

While the environment can’t currently change your genes, it certainly can affect which genes new people end up with. If genetic engineering in humans becomes practical at a large scale, the environment could become just as important as inheritance for determining the genes of newborns. I’d say the distinction is definitely at least blurred at that point.

Uh, I don’t really care a whole lot about whether the differences between modern Americans and Ancient Egyptians are caused by nature vs. nurture. What exactly would be the impact of that on any modern policy? Whereas knowing that the differences between poor and rich Americans is broadly genetic or broadly environmental has a huge impact on what sort of policies we should choose right now in modern America.

Not everything in siblings’ environment is shared, though. Between when I reached each developmental point and when my younger sister did, my parents had a lot of time to refine their parenting methods and – it turned out – be significantly more lenient with her than with me. When we moved to a new neighborhood, I was age N and had a lot of studying to do inside; she was age (N-K) and just young enough to still roam around yards with all the neighborhood kids. Being older or younger at a given time matters.

Plus, look at all the studies about the significant effects of birth order within a family. Having an older sibling to look up to, or a younger sibling to help, matters a lot in your psychological development.

According to Judith Harris in _The Nurture Assumption_, the birth order stuff is basically bogus. If there are enough different patterns you are looking for, in any one study you can probably find one by chance. Different studies find different patterns. Pool all the studies and the patterns vanish.

I have no expertise in the subject but found her book pretty convincing on that and other topics.

Thanks, David. I saw this comment earlier and was thinking, “Didn’t I see somewhere that birth order arguments are ‘refuted’?”

I think there are a lot of weak arguments for birth order effects that try to draw out slight differences in personalities between, say, the second middle and third middle child. But the strongest effect that I continue to observe as I get older is that if there is a single “wild child” in the mix, it is almost never the eldest. Of course, the “wild child” doesn’t always stay wild, which is consistent with the idea that parenting/environment makes more of a difference in childhood than adulthood.

Also, isn’t homosexuality correlated with being the second son? My father made this observation, very unscientifically, a long time ago. He attributed it to some sort of admiring of the older brother, but now I think the theory is that it has to do with testosterone exposure in the womb.

So it’s not impossible that there are multiple hormonal effects related to birth order that are consistent with an otherwise hereditarian position.

Wency, I’m going from memory here, but while there seems to little evidence for birth order having an effect. Less Wrong has a weirdly high proportion of first borns. This proves that the universe has a sense of humor.

As I understand it, homosexuality doesn’t just correlate with being a second son, but with the number of older brothers.

Have they ruled out, among the lesswrong data, that it could be caused by the greater genetic defect rate among later-born (since western people already tend to be born late, when their parents aren’t in their genetic prime)?

How many were only children (and therefore, technically, first-born)?

Anonymous, that sounds plausible. It might be after you adjust for age of parents at birth that birth order effects disappear. Still, if there’s a homosexuality effect in birth order, can that really be the only effect?

I’m thinking of the people I know who came from good homes but dropped out of school, got addicted to hard drugs, got pregnant at a young age, etc.

I can only think of one who is the first-born — a guy who had a nervous breakdown in college, got into drugs, dropped out, and I’m not sure if he ever went back and finished.

Strangely, he is part of a pair of identical twins where the other twin avoided hard drugs, finished school in four years, got married, and got a good job. It would be a good case study for non-shared effects, and I have no idea what to attribute the difference to.

One of the LW surveys also asked for the parents’ ages when the respondent was born and IIRC the answers weren’t unusually low in average.

I am a layman here, but … siblings must have a somewhat different environment when it comes to … their siblings. There may be a divergence when each sibling is looking for their niche in the family – Peter may decide that since Paul is the mom’s boy, he might rather be the more independent/adventurous one etc. So at the end each sibling is growing up in a slightly different family. I believe there are also different traits in siblings based on order of birth etc.

Right. I know a pair of identical twins who are obsessed with any and all of their differences. One informed me his eyesight was 20-22 and his brother’s was 20-24. One wants to be an engineer the other an actor.

So, sibling rivalry sometimes makes twins reared together more different in certain ways than if they were raised apart.

For example, Horace and Harvey Grant are identical twin 6-9 basketball players. In high school Harvey was the shooting forward, so Horace was, despite his slender frame, the power forward. If they had been raised separately, they likely would have both been shooting forwards at different high schools. (This actually worked out to Horace’s advantage since he enjoyed a longer NBA career, perhaps because he had to stretch himself to learn a different role in high school, whereas most future NBA star 6-9 guys are shooters in high school.

Judith Harris has a later book, _No Two Alike_, which is about the sources of difference in identical twins reared together, including one case of siamese twins who were quite literally together to adulthood–and had noticeably different personalities.

There is some evidence that environment matters more in samples including very poor people, who don’t make it into the usual studies.

That doesn’t sound great, if the results of such studies are being used to create government policies and programmes for school-going children of the poor/parents living in poverty/poor high school drop-outs etc.

Variance component estimates are relative to particular populations and environments, yes. So better environments will tend to yield smaller environmental effects.

Does this matter? I guess it depends on what you want to apply it to. If you’re interested in political or sociological matters, or in improving the general weal, this isn’t really a bad thing: it tells you that you’re going to have a hard time making things better with the simple obvious interventions. eg if schizophrenia turns out to have a small shared-environment effect, you’re probably not going to reduce rates meaningfully by some lead remediation or anti-fridge-mother educational programs, you’re probably going to have to adopt much more radical approaches.

One notes that all twins — identical or fraternal — shared an environment for nine months at a time where the influence was probably large.

That’s a point I was going to bring up, with the additional complication that the uterine environment is also partly genetic.

But even in the womb, one twin typically gets a better position.

I had a question about this shared environment stuff. What happens if you measure the heredity of “what language do you speak at home” or “do you use chopsticks when eating most meals”? Intuitively, you should get near 100% shared environment effects, right? Or am I misunderstanding? (Surely chopstick use is not genetic, right?)

Did anyone try to do this, just as a sanity check of the measurement methods?

You would get the right answer. Consider https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Falconer's_formula 2*(r_mz – r_dz). If you look at the correlation of monozygotic identical twins using chopsticks, it’ll be r=~1, since everyone in a household uses chopsticks or none; similarly, dizygotic fraternal twins will also correlate ~1 (or at least, I assume as much), so then it’s h^2=2*(1 – 1)=2*0=0; if h^2=0, then shared+non-sharedenvironment=1. You could also look at adoption studies: if the adopters use chopsticks, so will the adoptee, and likewise for nonadoptees, so h_n^2 = r_sib – r_ad = 1-1 = 0. So the formulas would get sensible answers in the case of parentally-determined stuff.

Thanks. Followup question: if cultural things like chopsticks are shared environment, what about the Southern US “culture of honor” I keep hearing about? Would some notion of “honor” have a large shared environment component? Or would you say that there’s no such cultural effects at all (a pretty remarkable claim, if you ask me)?

What about effects like “were you ever a member of a gang”? Surely that depends on whether there were gangs in your neighborhood, yes? So can we predict some strong shared environment component?

Basically what I’m asking is, do we EVER see a large shared environment component in ANYTHING? Because if not, something seems wrong.

E.g. in behavioral genetics studies of politics, partisan affiliation (Democrat vs Republican) shows much bigger shared environment effects than ideology measures.

Similarly accent and religious affiliation show high shared environment, while vocabulary and intensity of religious practice show higher heritability and lower shared environment.

See this chart breaking down political traits by genetic, shared environment, and non-shared contributions:

http://www.cell.com/action/showImagesData?pii=S0168-9525%2812%2900111-4

There’s a famous pair of identical twins raised apart known as the Nazi and the Jew twins due to their different political environments when they were children:

http://www.unz.com/isteve/identical-twins-separated-near-birth-the-jew-and-the-nazi/

They were, however, extremely similar in many ways.

“What happens if you measure the heredity of “what language do you speak at home” or “do you use chopsticks when eating most meals”? Intuitively, you should get near 100% shared environment effects, right?”

Yes, except insofar as siblings differ on those.

Okay, but are there actual studies that show shared environment effects in these things (or in *anything*)? If not, why don’t people conduct such studies? Chopsticks are boring, but what about other cultural effects like honor, politeness, respect for authority, etc.? (Surely those are different in Japan than in New York, and surely that difference is not 100% genetic, right?)

Jacob linked to a mega-meta-analysis of all pre-2012 twin studies below. There are shared environment effects found for many, many traits.

The OP exaggerates here:

“studies of many different traits tend to find that 50% of the variation is heritable and 50% is due to non-shared environment”

Non-shared environment tends to be larger than shared environment, but the latter is not uniformly zero.

“Surely those are different in Japan than in New York”

Yes.

Most all behavioral genetic studies are within a country, but when you include international datasets heritability goes down (because of the additional of international environmental differences). You can see that in publications of the Social Science Genetics Association Consortium (which use samples from many countries in Europe and North America).

If you do a behavioral genetics study with data from different times/cohorts, you will also get bigger environmental effects and lower heritability, for the same reasons.

Yes, this is why I thought it was a mistake when Scott took the studies he was looking at as evidence that it was pointless to try to change people by reforming society; surely one has to look at different societies to see how much difference changes in societies can make. And most of the studies don’t do that.

Carl writes:

“If you do a behavioral genetics study with data from different times/cohorts, you will also get bigger environmental effects and lower heritability, for the same reasons.”

That’s related to the Flynn Effect, where it turns out that IQ test scores tend to go up over the decades at a fairly steady pace.

Twin studies, especially identical twins reared apart, work very hard to look at nature and nurture over Space, but it’s slower to look at things over Time, which the Flynn Effect suggests is surprisingly influential.

I’m too tired to say anything intelligent, but I’d be remiss for not posting the Meta-Analysis of Twin Correlations and Heritability (http://match.ctglab.nl/). It’s a meta-analysis of all (and I do mean all) twin studies published up to 2012: “Currently the database includes information from 2748 papers, published between 1958 and 2012, reporting on 17804 traits on a total of 14,558,903 twin pairs. Have Fun!”

How many of the 14,558,903 twins pairs are overlaps? What would be the record for most number of studies a twin pair participated in? I wish I knew.

It may be a controversial addition to your list, but free will is another thing that would show up as “non-shared environment”. I don’t especially want to get into a free will debate, but assuming it’s real, Im guessing it wouldn’t end up on the nature side.

That’s covered under “biological random noise”.

Oh, yes. It is, however, very unpopular among people who do studies. I have actually read one saying that he doesn’t believe in free will because you can’t have a science of something with freedom. . . .

Little gap of logic there.

I think that viewpoint is misguided, but there’s a kernel of truth there: if free will is the ability for people to be an uncaused cause of some of their actions, then to whatever extent a person acts on the basis of free will, those actions can’t be explained on the basis of prior causes.

For instance, suppose 100% of the difference between successful people and unsuccessful people is that the former are taught the value of hard work. Well, that’s not free will. That’s a prior cause: the former were taught something the latter were not.

As I quoted in a previous thread concerning the medieval thinker Peter John Olivi:

The bottom line is that to the extent people’s choices are determined by free will, they are unpredictable and there is no outside intervention that can be imposed to improve their outcomes.

I think we’d need to taboo “free will”. People use it in radically different ways.

Some people (particularly from the humanities) treat it as a magical thing, free from the influences of physics/quantum physics and cause/effect where the magical soul impinges on physical reality and because of their version of “free will” the universe cannot be deterministic.

Others just mean that your actions are not practically speaking utterly predictable based on easy to compute simple rules.

If you’ve spent too long trapped in a room with true believers in the former then you can become quite dismissive of every mention of the term.

Measuring sources of variation shouldn’t put a ceiling on what interventions *could* do. If you start with a population in which everyone’s being poisoned by lead in equal amounts, lead explains very little of the variation of intelligence. If you clean up all the lead for half the population, lead exposure will explain a fair bit of variation in intelligence. If you clean up all the lead for everyone, lead exposure will once again explain no variation.

On the other hand, it puts a floor on the level of intervention needed to achieve noticeable change. If a variable affects some outcome but only when it’s moved beyond the range of normally encountered values, then you have to perform some radical changes to make any use of that information.

Yeah, lowering lead exposure isn’t really very radical but it’s not an example of a social intervention, the sort that nurture people really want to believe in.

Not entirely sure who you’re referring to as “nurture people”, but I suspect it shares a lot of overlap with people who are really concerned about:

a) poverty

b) pollution

In addition, lead is a non-racist explanation for racial disparities in intelligence and social well-being, and it can be blamed on evil corporations. It seems to me that lead remediation is exactly the sort of social intervention “nurture people really want to believe in”.

There’s quite a few liberals/leftists who aren’t comfortable with theories that highlight both a demographically measurable difference in IQ and significant downstream effects of that difference even if it’s a difference that can in fact be blamed on racism and the externalities of the private sector.

I’m not one of them, though.

Don’t forget gut flora!

That would have been my contender for ‘3e’. If you consider the human being as a ‘hotel’ for nine times as many ‘cells’ as those human body cells then the total (human and gut flora) genetic profile could easily vary between twins. Diet can lead to a different gut microbe profile, as can environmental factors like infections and poor hygiene, who you live with, or even (especially) courses of antibiotics.

The part that I bolded is the part that I take the biggest issue with. Correct me if I’m wrong, but don’t most of these studies sample people not just from the same country, but generally from within specific geographical regions, and often from within a relatively narrow range of socio-economic status and similar factors?

If so, then couldn’t the low values for shared environment simply indicate that the samples didn’t capture much shared environment variance? Wouldn’t this make these studies practically useless for determining whether or not “fixing society” could improve people’s life outcomes? These studies could effectively be controlling for societal factors.

A bit of anecdotal data on cultural differences: I recently moved from a city in the American South to a city in the American Southwest, and I have encountered a lot of noticeable differences in the way that people act. In particular, I only recently “got” what people mean when they talk about “Southern friendliness,” now that I’ve spent a lot of time in a culture without that trait. I have a very hard time imagining that these differences are due to genetics. Despite speculations about Scotts-Irish ancestry and the like, the ancestry of various regions is very heterogenous when you examine the data. For example, the population of the city that I grew up in, New Orleans, is about 60% black, 30% the same mix of European immigrant descendants that you find in every Atlantic port city (resulting in an accent that has been described as “Brooklyn on Valium”), and 10% Latino or Asian.

Shared environment can vary even within a homogeneous group for factors like whether the mother stays home with the kids, how strict the parents are, what extracurricular activities the kids do. Parents tend to worry a lot about making the ‘right’ choice on issues like this, and the question is how much effect it even has.

In theory, but how much do they vary in practice within a homogenous group? Even comparing different generations in the same culture you find differences in parenting practices that utterly dwarf the differences between modern parenting fads. To slightly paraphrase Jeff Foxworthy, “Now you are supposed to give your kids a ‘time out.’ Our parents took time out of their busy day to whup our ass.” On the other hand, it is common to hear testimonials from people who grew up as late as the 1980s saying that their parents allowed them to ride their bikes across town when they were in single digit ages.

It isn’t just parenting either. All sorts of things change between cultures or just over time within the same culture. To name one example, I gather that physical bullying was a lot more common a few decades ago even than when I was in elementary school in the 1990s. For a comparison between contemporary cultures, in the past few years most of my Facebook friends living in rural Louisiana got married or even had children in their early-to-mid-twenties (the youngest of them got married at the age of 23). Nothing that they posted gave any indication that this was considered unusual where they came from. That’s an almost certainly social environmental effect with a very large impact on life outcomes, but would these studies have captured it?

That may have been true of earlier studies, but there are now a number of big twin samples which are nationally representative. Several European countries have twin registries which recruit basically all twins born in the country. In the US, many twin samples can be regarded as representative of the populations of particular states at least and there are a couple of national samples as well.

Adoption studies have a restriction of range problem in that the worst kind of parents are usually ruled out by adoption agencies. Parents of adoptive children tend to be like Steve Jobs’ adoptive parents: stable solid citizens (while his biological parents were brilliant but unreliable). Adoptive parents aren’t necessarily wealthy or smart, but they are seldom impoverished or vicious.

I knew a reasonably rich family that adopted a child and then gave her back when it turned out she was merely bright and pleasant as opposed to brilliant and studious like their genetic child. It was weird, because they were an otherwise amicable and warm family and it was completely out of the blue.

The daughter spent a while on welfare raising her child, who she absolutely fawns over. So, she didn’t pick up much from her adoptive parents.

I would expect that adoptive families are unrepresentative of the general population in a number of other ways. Most obviously, they almost certainly have a higher rate of infertility, which correlates with age at first marriage and who knows what else.

Does anyone know how common scenarios like the one God Damn John Jay describes of an adoptee being returned by the adoptive family for whatever reason are? Because if it is at all common, it seems like it could pose serious problems for adoption studies.

On a semi-related note, I found an adoption agency’s “Guide to Connecting Adoptive Families with Waiting Children” through Google, and just from skimming it it looks like the process that determines which kids end up with which parents involves a lot of non-random factors.

There was a famous story about a family that gave up a severely mentally ill child they adopted from (Russia?). I think I have heard similar stories out of Popehat as well.

What’s the dependent variable that you are interested in? Clearly, environmental (social) factors are more relevant in explaining income than in explaining criminal behavior, and criminal behavior in turn is probably explained to a larger extent by environmental factors than talents, personality or intelligence.

But maybe I’m missing the point?

“Clearly, environmental (social) factors are more relevant in explaining income than in explaining criminal behavior”

Heritability of income in men is 0.58, heritability of crime is more like 0.5

the mechanisms behind the heritability are social, very likely in the case of income, somewhat less likely in the case of crime.

When you see “heritability” in a scientific or medical paper or usually in these comments, it’s talking about genes or (less likely) prenatal environment or weird epigenetic stuff, not social mechanisms — those are split between shared and nonshared environments. It’s measured with twin studies or other protocols that try to control for everything that happens after you’re born.

This means among other things that the more the thing you’re looking at depends on stuff your parents taught you or money you inherited from them, the less heritable it is. It’s counterintuitive, yes.

Thanks, Nornagest. I did not know that this is the common terminology.

Pre-natal environment is not included in heritability. This is not negotiable. There is a correct answer and an incorrect answer. Adoption studies (but not twin studies) will include it in their measurement of heritability, but that is systematic measurement error, not a variant definition.

When it comes to inherited epigenetic effects, the definitions break down and there isn’t a clear correct answer.

“This means among other things that the more the thing you’re looking at depends on stuff your parents taught you or money you inherited from them, the less heritable it is.”

Not necessarily – take math ability; your parents may “teach you” math (stuff your parents taught you) but maybe they did so because they themselves were (genetically) predisposed to be good at or interested in it. In this scenario is this more or less heritable? We don’t know unless we randomly assign some parents good at math the task to not teach their kids math and then look at how their kids compare to their counterparts whose parents had no such restriction.

The trick with humans is that we have an “external phenotype” – i.e. our genetic predispositions compel us to “create” a particular environment that we subsequently measure as environment and contrast it with “genetic heritability.”

the swedish twin study on income to which scott links is very interesting but limited (1) to the citizens of the very egalitarian swedish welfare state (2) to the extent that very rich people were excluded as outliers, although the questions which factors make people super-rich seems quite relevant. I’m sure the results would be different for the United States, not to mention the entire world, including countries such as Switzerland (58,149 int$/cpt) and Congo (729 int$/cpt). Maybe this seems trivial, but whether income heritability is 0.58 or ridiculously small depends on what context is implicitly controlled for.

Is this true? Eg 60 years ago, being gay was illegal, now it isn’t. So someone could be criminal under one set of laws but not under another even while still doing the same thing.

Was actually being homosexual illegal? Or just performing homosexual acts, regardless of one’s orientation?

There’s variation in how much people prefer homosexual acts, so that affects the odds of being convicted of homosexual acts. Or were you just looking for more specific language?

The laws on which drugs are illegal vary according to time and place, so that’s another example of the same acts being criminal or not depending on circumstances.

Criticizing one’s own government is also variably criminal, and it wouldn’t surprise me if there’s a genetic component to how likely people are to criticize their governments.

I’m not taking Tracy’s comment at face value (or rejecting it out-of-hand) because I’ve heard before some of the more curious stances on homosexuality that come from Protestant Americans. Compare the Catholic “you’re okay if you don’t act on these impulses” vs opinion of at least some American Protestants/Evangelicals “if you feel these impulses you are damned to Hell, regardless of whether you act on them or not”. So it wouldn’t be too far from the realm of possibility that there would be a law forbidding someone to be internally homosexual, regardless of sodomy.

«Catholic “you’re okay if you don’t act on these impulses”»

I was raised Catholic in Portugal. And we had to say things like “I have committed sins either by action, inaction or thought”. Jesus himself in the Bible says to take off your own eyes if you look at a woman the wrong way, because it is better to go to heaven without some part of your body than not going to heaven at all. So they all punish thought crimes. I don’t think religions are as easy to stereotypes as you do there.

@Ricardo

Per the CCC:

This is not a condemnation of those who suffer homosexual urges to Hell for having them. They’re in the same boat as those who have other kinds of lustful thoughts.

@ Anonymous:

And that boat in sailing to hell, unless they repent and ask for forgiveness in the name of God.

Which, of course, gay people are not going to be inclined to do insofar as they don’t think they’re doing anything wrong.

Consider the possibility of the existence of people who do not find their natural inclinations to be morally right.

@ Anonymous:

I didn’t say anything to rule out that possibility.

I said “insofar as” they they don’t think they’re doing anything wrong.

Of course, in order to be convinced that their natural inclinations are wrong, society would have to send that message to them. Which seems incompatible with a message of warm acceptance.

“We’ll accept you and consider you morally good so long as you deny your fundamental sexual impulses.” It should be obvious why that message has little appeal.

That’s not to say that, in and of itself, makes the Catholic position wrong. Maybe the truth is not very pleasant. Many non-religious people think a similar thing about pedophiles: that they don’t have any control over their “orientation”, but that they are “called to chastity” and just have to repress it because acting on it would be immoral. Nevertheless, they’re naturally going to fear and mistrust pedophiles because they recognize that they are cursed with a greater tendency to do evil.

And that boat in sailing to hell, unless they repent and ask for forgiveness in the name of God.

Not necessarily. The thoughts must have the assent of the will. Trying to control your thoughts soon reveals that thoughts frequently occur without its consent. The term for this is concupiscence.

And yes, there are Protestants who think that concupiscence is sinful. Not orthodox Catholic teaching though.

@Vox Imperatoris

OK, that makes sense.

Idly, what’s your standard of classifying pedophile behaviour as immoral, but homosexual behaviour as not immoral?

@ Anonymous:

One of the two is both immoral and illegal because it’s psychologically harmful and non-consensual.

The other is neither one of the two. Maybe you can come up with some argument that it’s harmful and therefore immoral (I disagree), but it’s definitely consensual.

How much do we learn from studying doctrine about how a religion works out in practice?

Oh dear, is that question a variation on genes vs. environment?

“One of the two is both immoral and illegal because it’s psychologically harmful and non-consensual.”

Our legal rules may treat it as non-consensual, but in real terms that depends on the particular case. Psychological harm as well.

Mencken mentions somewhere that he lost his virginity at age fourteen with a girl of the same age. Perfectly normal behavior in many societies. As of 1880, age of consent in the various U.S states was mostly either twelve or ten. Twelve for girls and thirteen for boys, plus some evidence of puberty, in traditional Jewish law (maybe twelve and a half and thirteen and a half–I’m going on memory).

And that was the age of adulthood, at which they could marry without parental consent. A girl could be married off younger than that by her father, but had the option of withdrawing from the marriage when she became an adult.

@ David Friedman:

I’m not saying that our age-of-consent laws are necessarily perfect or that you’re an evil rapist for sleeping with a seventeen-year-old.

We can debate over where the line ought to be drawn. I think eighteen (which is not the line in the majority of US states) is fairly ludicrous.

But strictly speaking, pedophilia refers to attraction / sex with prepubescent children.

In any case, if you want to argue that twelve-year-olds can meaningfully consent, and the sex is not harmful to them, then if that’s true there’s nothing wrong with it. I don’t know if it is true, but that’s the criteria I have.

not a lawyer, but I there’s no way you’re wrong.

but still, that’s hairsplitting

I thought it was doing things that was illegal. My apologies for the unclear language.

“I haven’t heard other people/experts in the field talk about this nearly as much as I would expect them to if it were true”

Steven Pinker makes many of these points in The Blank Slate.

Yeah, my impression of the situation from reading Pinker’s book is basically exactly the situation that Scott expresses in this post.

The non-shared environment contributes 50% of variation, just as much as genes. That means things like your friends, your schoolteachers, and even that time you and your twin got sent away to separate camps must be really important. More than enough there to continue worrying about how society is Ruining The Children, right?

You are summarizing an important aspect of the zeitgeist among educated people of a certain sort. There’s a tremendous belief that there must be identifiable Best Practices by which we can improve human behavior and thereby remedy all sorts of problems. But if the non-shared environment is less susceptible to control than we were led to believe then there is less reason for people to worry too much about following the recommendations in a click-bait article that begins with “According to a recent study…”

50% genes, 26% noise, 18% luck, 9% band camp, and 2% butterscotch ripple.

Consider my priors updated.

Why not more in the “genes” bucket? Genes that differ between twins are still genes.

Not if the genetic differences are caused by environmental differences.

You mean like living in the Chernobyl exclusion zone or next to a coal mine?

I don’t think it’s an error to classify factors like what kind of boss you have or how vigilant the cop in your neighborhood are as non-shared environmental. Nor is it wrong to look at a difference in income and conclude that genes do not 100% control professional success.

They are definitely non-shared environmental variables, but they have zero effect on ability yet huge effect on outcomes. This is why the questions need to be posed carefully. If you want to measure propensity to commit crime, the presence of an alert cop has no effect on somebody’s propensity to commit the crime (assuming they aren’t aware of the cop’s presence), but it has an effect on your ability to measure criminal activity. If you want to measure the rate at which people from a given set of circumstances get arrested, the presence of an alert cop is a huge part of the non-shared environment.

The bad boss might be relevant if the goal is to investigate ability to navigate office politics, but it’s irrelevant if the goal is to investigate ability to put together a technically sound product (assuming, for the sake of argument, that the political situation is fine up until the point that the work is a success, at which point the boss swoops in to steal). If you want to measure technical ability, the presence of a bad boss who steals credit is measurement error (if you’re measuring technical ability based on professional outcomes). If you want to measure interpersonal skills in an office environment, the presence or absence of a bad boss might be an independent variable in the experiment.

And if there was some outward, easily perceived marker, which policeman were trained correlated with danger, and therefore were more alert ….

It’s fair to conclude that genes do not 100% control professional success even if they did 100% control ability. The race is not always to the swift; that’s not a new finding.

I’m not sure whether finding out that it’s harder to get evidence against 100% genetic control of ability should make me update towards it being likely.

May it be the case that the shared environment is just very similar for different people or close to the top of its efficiency on the values measured? Let’s imagine a society where all your life outcomes depends on whether you do or do not know how to prove the Pythagorean theorem (example by A. Markov). If all the children are trained for all their life to prove it, the differences will be almost exclusively genetic, and if it’s an obscure fact no one cares about that is only learned in a few rare math clubs, it’s almost exclusively shared environment (the math club you went to). Most of the things we measure are by coincidence the things we care about as a society, so I expect them to be more genetic than average.

This all seems consistent with Gregory Clark’s research from The Son Also Rises.

TL;DR: In individual instances of inheritance, luck and genes are roughly in the same order of magnitude. Across a whole lineage, it converges on like ~80% genes.

“And it would make the opportunity to

changefilter those outcomes through geneticengineeringdiscrimination even more tempting and much cheaper.”Are you trying to say that reality is racist?

Reality is inherently unfair. It’s not always about race, of course, unless we make it so.

Still, there is no end of excuses for people (whose terminal values are a mystery to me) to choose racism as a heuristic.

>Reality is inherently unfair. It’s not always about race, of course, unless we make it so.

Sure. I inferred racism due to a combination of genetics + discrimination (sexism doesn’t quite fit), though I admit, Multiheaded’s post is highly compressed.

>Still, there is no end of excuses for people (whose terminal values are a mystery to me) to choose racism as a heuristic.

Can you unpack that a little? Racism is one of the easy heuristics, because of how easy it is to tell apart different races.

I think multiheaded is talking about Gattaca-type stuff, not racism per se.

I always thought Gattaca was a stupid movie, though. Just because some people with the rare heart condition don’t die, doesn’t make it a good idea for the space company to hire them to fly the ships over equally qualified people who don’t have it!

Need an epilogue to the movie where he’s flying the ship into land, has a heart attack at the wrong moment and everyone dies.

The problem with genetic discrimination is that it’s always way harder than non-genetic discrimination.

Let’s say I want high-IQ employees. I can either wait twenty years until we truly understand genetics of intelligence, make all my employees give me a saliva sample, pay for/wait for a whole genome analysis, and end up with something that, assuming all of our discoveries are correct, correlates somewhere between 0.5 and 0.8 with the employee’s IQ.

Or I can just have the employee take a quick IQ test and get something that correlates near-perfectly with the employee’s IQ. Sure, that’s legally iffy, but it’s hard to imagine a legal regime where the IQ test remains illegal but the genotyping isn’t.

Does anyone have an example of genetic discrimination that doesn’t fall victim to the same problem, other than the GATTACA example of people at risk of heart disease? (and honestly, a world where people prone to sudden cardiac death don’t become pilots doesn’t seem like much of a dystopia)

It’s only illegal if you can’t prove it works.

From Griggs v. Duke Power

Yes, the people arguing “liberal conspiracy” and complaining about how this is unreasonable need to keep in mind that these were the kinds of “objective tests” being used to deny people the vote.

Also, that Duke Power is a public utility.

Now, I think private businesses shouldn’t be liable for discrimination suits, whether it’s for “disparate impact” or “plain old KKK racism” . But then intention is clear: if only white people like the idea of soccer, they don’t want employers to set some policy like “we only hire people who like the idea of soccer” and then claim they weren’t intending to discriminate against black people—since whether they intended it is virtually impossible to prove. If it has a disparate impact, it should be related to the actual job qualifications.

I think that’s a perfectly fine rule for the government or public utilities.

The Supreme Court even recently ruled that New Haven was unconstitutional in its disparate treatment of white firefighters. The claimed basis was the city’s fear that promoting better-qualified white firefighters over black ones might cause a disparate impact (unrelated to job qualifications). But the Court held that the city had no evidence of an impermissible disparate impact and therefore couldn’t discriminate against white people for that reason.

While I’m not a lawyer, I am absolutely certain that if some insanely rich person, say a Michael Bloomberg*, bought out all the shares of Duke Energy and said “we’re going Sole Proprietorship, de-list us from the NYSE”, the Supreme Court isn’t going to say “well, in that case, Title VII doesn’t apply to you.”

Also, amazingly dick move in conflating the tests used at polls with what was used by employers in hiring and promotion determinations. Aptitude tests could be abused (Duke already had an outstanding policy prohibiting employment of blacks outside of certain areas, which should have been sufficient to trigger Title VII), but they were a valuable tool to help disadvantaged types, who would not (and even today, do not) have the resources to get degrees. Speaking from experience, it is emphatically not superior to have high-paying jobs go to people on the basis of mommy and daddy buying a degree in underfuckingwater basketfuckingweaving, while more experienced, more capable employees languish in low-paying jobs.

*I honestly don’t know if even he, or anyone, has got the money to do that.

@ nyccine:

Clearly not. And I explicitly said that I disagree with the court insofar as I don’t think that the government ought to be able to tell private corporations whom they can hire. I’m just pointing out that in the case at hand, we have some kind of typical quasi-public abomination.

I don’t disagree that aptitude tests could be very useful and beneficial to minorities and other disadvantaged people.

But if, in a particular case, a certain group of minorities can establish that a test is causing a disparate impact on them which is not justified by the actual job qualifications, it seems like the test is not benefiting them.

@nyccine

Note that Griggs struck down a (high school) degree requirement as well as an aptitude test. Both are supposed to be subject to a burden shifting framework — the plaintiff must demonstrate a disparate impact and then the burden shifts to the defendant to show a demonstrable relationship to job performance.

Why the common takeaway of the case seems to be: no aptitude tests ever, and any degree requirement, no matter how nonsensical, is perfectly okay, is a mystery to me.

Brad, you might equally well ask why so many people cite Griggs when it is a dead letter, superseded by (identical) legislation.