This is the semimonthly open thread. Post about anything you want, ask random questions, whatever. Also:

1. Thanks to everyone who attended the meetups earlier this month. It was nice to finally get to meet some of you. For those of you at the Google meetup, Jesse has created a relevant internal mailing list at slatestarcodex-discuss

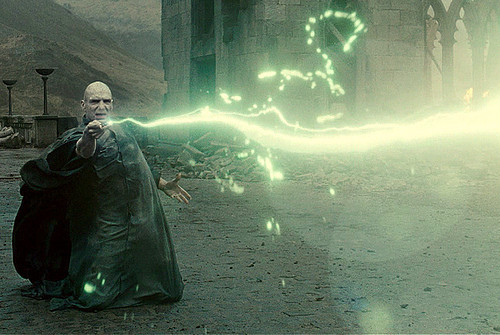

2. Relevant to the title: Harry Potter and the Methods Of Rationality is ending Saturday. For those of you who aren’t familiar, this is a Harry Potter fanfiction by Eliezer Yudkowsky, the guy who taught me most of what I know about rationality and writing. Most people either love it or hate it in a hilarious over-the-top way; since both are interesting, I can highly recommend it to people who like that sort of thing. See also the Vice article about it. You can find the story at HPMOR.com.

3. And for those of you who are familiar, you might be interested in the HPMOR wrap parties going on Saturday in various cities around the world. Check the map here to see if there’s one with you, or get more information on this page.

4. I’m on call Saturday morning, but if it’s not too hectic I’m going to try to make the Detroit party, which looks like it’s about 20 people strong now. If anyone else in Michigan is interested, come to 1481-A Wordsworth, Ferndale, Michigan 48220 at 3 PM and hopefully I’ll see you there.

5. If you are a high school student, you might want to think about applying to SPARC, a free camp for talented children focusing on game theory, cognitive science, and statistics. Many of the instructors are friends of mine and/or Slate Star Codex readers, and one of the instructors is the aforementioned Eliezer Yudkowsky. See their website for more details and the application.

6. Comment of the week is this real-life trolley problem and the British government’s weird response to it.

7. A request for legal advice, but it’s long enough that I’ll stick it in the comments rather than write it all out here.

There’s an even better British real-life trolley problem, that’s almost unknown other than to train enthusiasts, since the only report of it is buried on page 17 of a 65 page incident report

A broken down maintenance locomotive (RGU) with two workers on board, and with its brakes disabled was being towed uphill when it broke away. It was heading towards a working section of track which had running passenger trains;

An interesting example of Schelling points:

My local Swing dancing club has a free weekly dance, and a monthly dance that costs 5-10$ to get in. The monthly dance is slightly longer (though most people don’t stay the whole time anyways), but otherwise basically indistinguishable from the weekly dance (which is free, and held at the same place by the same people).

The monthly dance always has a lot more people come – as in about 3-4 times as many people. This is probably because a lot of people like dancing enough to go once a month but not once a week, and partly because people only want to go when there are enough other people, which only happens once a month. This Schelling point effect is apparently enough to counter the 10$ cost most people pay to get in.

The idea of measuring how much people are willing to pay for a Schelling point is interesting- does anyone have a good example that measures the limits of this effect?

That’s a great example.

It reminds me of the concept of “Paris Metro Price Discrimination,” where there are two classes of cars, identical except in price. People pay simply for less crowding, which exists solely because of the different prices. But that’s a simpler example than paying for a Schelling point.

American Psychological Association demolishes the gender-difference myth:

http://www.apa.org/research/action/difference.aspx

https://slatestarcodex.com/2014/12/13/debunked-and-well-refuted/

Also, it’s from 2005.

I don’t think that link is useful or relevant. Hyde asks the right first questions and gives the right answers to them. People claiming to debunk her are just wrong. She fails to ask any further questions and encourages the publication of articles like this one that claim to debunk other beliefs. It is that jump that is nonsense, but the main problem with the jump is that it is vague, not that it wrong. There are no contrary pairs of studies. There are only people who want to address different questions (and people too clueless to even ask questions).

That is a really awful essay. Try the original paper.

Scott posted another study in a link dump and there’s some discussion there, but it’s buried in all the discussion of the other links.

Yes, most personality traits have small sex differences, maybe d=0.3. But what do you mean by sex differences or sex similarities? Do you care about particular personality traits? What the second paper says is that by using all personality traits, it is easy to distinguish sex. In that sense, sex differences exist. Which is necessary but not sufficient for them to exist in places that we care about. The ultimate question is: for a particular purpose, do the relevant personality traits generally point in the same direction or different directions?

The second paper also points to several sub-traits of the big five that have much larger differences than the big five. This is rather suspicious. If sensitivity (tender-mindedness) has d=2.3 and warmth has d=0.9, why doesn’t PCA doesn’t produce a first factor of sex?

why doesn’t PCA doesn’t produce a first factor of sex?

How do you know it doesn’t?

That’s a somewhat serious question – assuming that the creators of the OCEAN (and HEXACO) models did use some sort of PCA to create or reinforce their models, did they in fact discover that the first principal component was sex, then go on to describe the second through sixth (or seventh, for HEXACO) principal components for their model?

I don’t have anywhere nearly enough background in psychometrics to know where to begin looking up that question. (Other than to check Wikipedia, of course.)

What I’ve always heard is that CANOE is simply defined as the first five principal components of the Galton lexical personality test of applying each English personality word to each subject. That’s what Thurstone did in Vectors of Mind (1934, 1947).

This article on sex differences has been influential in some circles. I was wondering if you could check it out.

“Sex Redefined

The idea of two sexes is simplistic. Biologists now think there is a wider spectrum than that.” http://www.nature.com/news/sex-redefined-1.16943

Does anyone remember that post that Scott wrote about how much of political arguments were just noise and angry yelling? I think he took meaningless connector words out of things people had written and left what became obviously non-sensical non-arguments. If it exists, could someone maybe give me the link?

It’s in “Top Posts.” See if you can guess from the titles.

https://slatestarcodex.com/tag/fnord/

I hope this doesn’t count as race since that’s not my point, I only mean to refer to politicization aspects and not the substance. Sincere apologies if it does. Anyway:

http://www.washingtonpost.com/blogs/post-partisan/wp/2015/03/16/lesson-learned-from-the-shooting-of-michael-brown/

http://www.nationalreview.com/corner/415349/ferguson-report-and-right-jason-lee-steorts

Two articles from either “side” on Ferguson, both encouraging their tribes to look a bit past the noise and to focus on discussion of more substantive issues.

Between this and a whole lot of anti-purity test thinkpieces in the past week or two, I feel like there’s been some encouraging signs of anti-tribalism lately. Maybe we’re moving in a more positive direction? Dare I dream?

Pun relevant to thread title.

A small study shows that practicing more is not as important as practicing correctly, even if that means slowing down, breaking things up, etc:

http://www.creativitypost.com/psychology/8_things_top_practicers_do_differently

Any thoughts on this? My initial reaction was just “well, so people who were good at things the first time were good at things the second time and giving the bad people more practice time just doesn’t help as much as we’d hope,” but if they’re right about which strategies might work for just about everyone it would have pretty big implications for teaching. Namely, it seems like it’s more important to get new material right the first time, even if that means slowing down and spending more time on each bit of new material.

I’m not entirely sure how this tallies with my own experience, because, on the one hand, it’s definitely true that bad habits are harder to break than good habits to instill. On the other, learning and forgetting and learning and forgetting seems to be an inevitable part of all learning processes for me, as does “jumping in and picking up necessary basics as I go” to overcome initial hurdles of boredom.

I think there’s some level of how “right” you have to get something for it to matter. Having learned to fence, and learned several dance styles, it’s possible to practice certain moves getting one part right while being somewhat sloppy on another aspect of those moves, then getting the other aspect right later. (Footwork versus body movement in many sorts of dancing, for example.) However, you can’t be doing the other part really *wrong*, or you will be setting yourself back.

Having studied cello for quite some time, nothing here really surprised me. Other thoughts:

This sort of “reflection” is a practice strategy recommended in Make It Stick, a book by a pair of cognitive scientists who’d just completed a decade of research on effective learning (recommended).

The article claims that the top three pianists used all these strategies and all the lesser pianists barely utilized them. I find this both surprising, because every single student-musician who was serious about music uses them, and not surprising, because everyone I know who’s serious uses these strategies; if you’re not using them, no wonder you’re not in the top.

Then again, I live in an unusually good musical community. My friend is son of a professional conductor, has played Yo-Yo Ma’s cello several times, and has studied under the best teachers in the world the country’s best music programs. I have a fraction of his talent, growing-up-in-a-musical-household, and practice regimen, and I’ve still been able to work with members of the Philadelphia Orchestra.

Notice how close Texas (where the study in question was conducted) is to any of the Big Five orchestras. It’s extremely plausible that the study subjects—advanced undergraduate and graduate piano and piano pedagogy majors—are genuinely unaware of the best practice strategies that are completely obvious to someone relatively talentless like me because they don’t come from a culture that supports it*.

There’s probably a pre-selection effect here: if you’re a music student and know how to practice effectively, you probably aren’t going to school in Texas, and if you’re a good music teacher and keep up with what works the best and are good at changing your mind in response to new evidence and maybe even read some cog psy literature, you probably aren’t teaching in Texas.

—-

*If you doubt that different regional cultures can have such drastic effects, just look briefly at how entirely Korea dominates The Rest of the World in Starcraft 2. I can’t dig up a really great primary reference, but Koreans are so much better than “foreigners” (as they’re called) that there’s essentially two leagues: one for Koreans and one for everyone else, so they aren’t beaten by Koreans. It’s a bit like men’s and women’s leagues in physical sports: the best non-Koreans can maybe compete with second-string Koreans, but it’s truly remarkable/unheard of for a foreigner to beat an A-team Korean. For instance, Hydra, a Korean progamer somewhere between A- and B-team, was recently defeated by a foreigner, after going something like 60-0 against foreigners.

…There’s a point here, and it’s that Koreans beat the snot out of non-Koreans and that the best explanation is Korean culture: they treat the best Starcraft players like Americans treat the best baseballers (in all honesty, they inspire more awe—when was the last time a baseballer was painted on an airplane?), and they’ve figured out how to practice Starcraft most effectively. Foreigners don’t the same coaching quality, high-level practice partners, or practice regimen, and thus get the snot beat out of them.

So, yes: if a game like Starcraft, which is inherently internet-centric, can have the best players in different regions doing different things because of cultural differences, then we shouldn’t be surprised to see something similar in classical music, which doesn’t mesh well with the internet.

Re: the study — meh. For one thing, the study doesn’t seem to have had a control group. They simply sat 17 college musicians down and drew correlations.

Re: the conclusions — this absolutely agrees with my personal experience. Like a coach of mine used to say,

The underlying idea was that it’s really easy for us athletes to rationalize “Yeah, my practice runs are sloppy, but I’ll have perfect form on race-day.” This is lazy and false. If we practice with bad habits, then we’ll race with bad habits.

The goal is for us to train such that good form comes second-nature. This way, when we’re chugging along on an empty fuel-tank, we’ll be able to maintain good form without thinking about it. If it’s not second-nature, we won’t have enough will-power to maintain good form on race-day, because we’ll be too busy fighting through the fatigue.

…

As a hobbyist musician, I can tell you that slowing down difficult passages is considered best-practice. Isolated one passage; slow down (enough to play without mistakes); repeat the passage; then gradually speed up repetitions as the piece becomes more comfortable. Like zz said, pretty standard.

Repeating decelerated passages builds what’s called muscle memory. If you play incorrectly, your muscles will memorize the wrong movements. Better to play the right notes slowly than to play the wrong notes quickly.

Also, I remember one high-school band teacher who differentiated himself from the average teacher by (among other ways) making us practice a single difficult passage for an entire class period. I will be the first to vouch that it worked miracles. The typical band teacher will use class-time to simply run through the sheet music repeatedly from top to bottom and say handwavy things like “um, maybe we could be more dynamic” (this is a generalization).

(He was my second favorite teacher because he proved himself immensely classy and competent. I had to delete several paragraphs of merely-tangential fanboying. In lieu, I will note that our music program started winning lots of awards under his stewardship.)

Well, yeah. If you’re just learning music for fun, go ahead and play your favorite songs without laying down the fundamentals. I know lots of self-taught friends who’ve played for years without ever learning what a scale is. If you’re playing music as a hobby, it’s perfectly acceptable to just sight-read everything and make small mistakes in front of an audience. That’s generally what I do nowadays. But if you want to improve your musicianship and be at the top of your game, then you gotta practice the boring stuff.

Do you think Kobe Bryan spends more time practicing alley-oops, or boring lay-ups? The lay-ups, of course. For music, the analog is practicing scales. Practicing scales is super-super boring. Hobbyists generally don’t practice scales. But for those who want to shred like Van Halen, starting each practice session with scales will pay spades in the long run.

And like I said before: good habits are important. Consider weight-lifting. Lifting with good form is a must. If your torso lunges while practicing curls, then you’ll finish your sets more quickly – but your biceps won’t gain as much. Similarly, if I practice lazily (with bad posture, or without a strong diaphragm, or without a tight embouchure, or with poor articulation, or without stagger breathing, or without intonation, or without a strong attack, or monotonously, etc) then I’m not going to improve as nearly as quickly.

I agree with the other commenters that this isn’t surprising at all, even though the study isn’t really powerful enough to justify its conclusions without a musician’s prior. That seems to happen a lot with this kind of research. These experiments don’t really have the scope to powerfully test hypotheses in realistic settings (that’s never easy, and doubly so here), but they still seem to point toward conclusions well known to expert folk wisdom or to more general learning research (deliberate practice, interleaved practice, spaced repetition, testing effect, metacognition, scaffolding). Your best bet is still having a good teacher who can communicate these things; barring that, find some good expert case studies (I like The Practice of Practising) and translate the most robust research on learning in general. (Even then it’s hard for most people to actually put this stuff into practice — see link in name.)

http://www.patheos.com/blogs/hallq/2015/03/harry-potter-methods-rationality-review/

I kind of like HPMOR but this review (by HallQ) seems to point to real problems. Also the links in it to other articles (by hallQ) are good.

I personally disliked the conclusion, as well. It was too gimmicky. Not because Voldemort was stupid, because he wasn’t as stupid as it might seem. But the way Harry solved the final problem was just… boring, somehow. It didn’t have enough action to make up for the gimmickiness, and it didn’t have anything to do with the larger narrative.

damn… the entire series is 661,637 words

that easily makes it one of the longest contiguous novels ever http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_longest_novels

From the review:

Cbvagvat bhg gur vzcynhfvovyvgvrf bs cerivbhf vgrengvbaf bs lbhe senapuvfr, ohg fgvyy gelvat gb tvir lbhe nhqvrapr gur traer-svpgvba rkcrevrapr gurl jnag, whfg zrnaf lbh’yy raq hc snyyvat onpx ba irefvbaf bs gubfr vzcynhfvovyvgvrf va gur raq [….]

Pratchett might have bit the bullet and raised this meta to a meta meta, probably turning a whole level inside-out. Ref _Witches Abroad_, misc, and especially what tvtropes calls Traer Fniil in _Guards! Guards!_

Happy Pi Day.

03/14/15

Vi Hart has something to say about that: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5iUh_CSjaSw

I’m familiar with the Tao Manifesto. This just gives us another reason to bake more pies in June. 😀

Not to be insulting, but I have come to think about this day as Laugh-At-Americans-Because-They-Can’t-Even-Put-Dates-In-A-Sensible-Order-Day.

Not as catchy, I’ll admit.

That said, even DD/MM/YY or DD/MM/YYYY is still somewhat middle-endian – for a non-middle-endian date format you want YYYY-MM-DD, but I don’t tend to go for that – except in filenames…

I use YYYY-MM-DD almost exclusively, in hope that exposure will prompt better filenaming.

ISO! ISO IS THE STANDARD!

For the record, I do use the YYYY-MM-DD format whenever I can. Because of both the ISO Standard and the decreasingly-significant digits. Not that I’m keeping track, but I’m the only American I know of who does this (in the hopes that others will catch on to the format’s sheer correctness). But in the mean time …

I’m currently going through the Canadian immigration process, where you’ll be happy to learn all dates must be entered in the form YYYY-MM-DD.

It’s an International Standard. I learned this from Adam Cadre.

DD/MM/YYYY is not middle-endian. DD/MM/YY isn’t, either, it’s just suffering from lossy compression.

The trouble with DD/MM/YYYY is… if I label the most significant digit as 8 and the least as 1, then 21/43/8765, with the ends (1 and 8) in the middle. OK, with byte orders, you don’t worry about ordering within the byte (is it even meaningful to talk about ordering within a byte in the same way as ordering between bytes?), so treat DD, MM and YYYY as being analogous to bytes, then you can’t call it middle-endian. This is why I said “somewhat”.

Ok. I hadn’t been thinking of that, but you’re right.

Speaking as an American, I always put my dates in the infinitely more sensible DD/MM/YYYY format.

I have a vague hope that eventually all of my countrymen will spontaneously start following me.

And in the meantime, you and the MM/DD/YYYY people are of course quite OK with people reading the date you wrote as 01/02/2015 and having no clue what it means. I mean, actually communicating information is less important than making a statement about how stubborn you are, right? Wouldn’t want to be like those wimps who go for the international standard of YYYY-MM-DD, which nobody misunderstands…

OK, sorry for being a bit overly-sarcastic (especially since I’m not really sure that Chevalier Mal Fet was serious). But really, why do people use MM/DD/YYYY or DD/MM/YYYY? Do they not realize that substantial numbers of people use the opposite of these two formats, and that they therefore aren’t actually communicating?

Do they not realize that substantial numbers of people use the opposite of these two formats, and that they therefore aren’t actually communicating?

Americans don’t really believe in the existence of people outside the U.S.A. (e.g. all the English language versions of Windows being in default American so you have the happy experience of downloading your Irish-based purchase of your Irish-based usage of the Office Suite and going through everything from Word onwards and switching from U.S. spelling etc. to what you actually use – if I knew who thought setting Word by default to font Calibri, size 11, 6 pt spacing, multiple line spacing was a good idea and what every customer wanted, I’d strangle them with their own intestines), and the rest of us are either using a system that everyone else we communicate with understands, or we have to like it or lump it translate from American; it does help when reading a date given as 3/17/15 to go “There aren’t 17 months in the year, so this must be the American for St Patrick’s Day”. This does not, however, help when you barbarians call it Patty’s Day 🙂

YOU barbarians? YOU? Hey, here in this village outside Sligo, I’m the one who calls it “St. Patrick’s Day” and my husband (a Tyrone man) and the locals who wish me a “happy St. Paddy’s Day”.

But I do agree with you on the stupid fake ineffective internationalism of Windows. I had to buy a new laptop from a UK company a month ago and kick Windows in the crotch repeatedly until it realized I was expecting Irish English, not UK English, and not whatever that thing is I grew up speaking in the US.

Also, “16 Mar 2015” is my standard since I became a documentation specialist for a multinational corporation. It doesn’t help the non-English speakers much but since I write in English anyway, it presumably gets translated along with the text.

As an American, when the value of the day and month are such that there would be ambiguity as to whether a written date was day-first or month-first, I decide which to use by flipping a coin. Otherwise, I use ISO format.

Personally, i just write the name of the month for clarity’s sake.

I do the same. A date like “1/Apr/2015” may seem clunky, but at least there is no possibility of a misunderstanding.

But that’s only for documents that will be used by others, like checks or government forms. My personal files use the YYYY-MM-DD convention, which allows for easy alphanumeric sorting.

The Russian (Soviet?) convention seemed to be DDmmYYYY with the month in roman numerals. So yesterday would have been 14III2015. My source on that may not be accurate, but it seems a somewhat sensible system, since only August is longer than using 3-letter abbreviations. (And you don’t need to translate, either. What’s 17ene2015?)

I also systematically do the same, in case I’m read by an American that doesn’t go out much.

It’s maybe more sensible, but if you say we’ll meet at 1/1/2016 10:00, now you’re listing them in the order (from largest time unit to smallest) 3/2/1/4/5. How sensible is that?

That is why 2015-01-01T10:00 (with military time, of course) is the standard. There’s very little chance of people misunderstanding you if you put years first and minutes last.

Your own Pi Day celebration on 3 Dodecember will surely leave ours in the shade anyway.

Please, it will be on 31 April. 😀

Look, if you want to celebrate Pi Day on July 22, we’re not going to lead an international coalition to liberate you or anything. Well, probably not.

Why would anyone read Harry Potter and the Methods of Rationality when they could read Harry Potter and the Natural 20 instead?

You don’t sort by favorites and read all of the top ones?

Because Harry Potter and the Natural 20 doesn’t update often enough?

Why does it have to be either or?

An idea I’ve been kicking around, which is probably stated better elsewhere: “Do your own thing” doesn’t scale.

When my dad was young, the evil patriarchy reigned, and women were more or less supposed to be mothers and housewives. They could maybe do other things, but it wasn’t entirely uncontroversial, and in any case, being housewives and mothers was clearly the main thing they should do. A woman who categorically didn’t want to be a mother/housewife was obviously broken somehow.

Dad and others were attracted to the feminism of the time, whereby they would change society so that if women wanted to be housewives and mothers, they could, and if they wanted to be other things, they could. Women obviously still had to have the babies, but if they wanted to have careers and the men wanted to raise the babies that was fine too. Basically, whatever works for you. Also, it was pretty hip back then, unlike now where every goddamned college kid and his dog are feminists.

Flash forward to today: Women are more or less supposed to have careers, like men. They can maybe have children, but it’s not entirely uncontroversial, and in any case, having careers is clearly the main thing they should do. A woman who aspires to be a mother/housewife is either a moron, or laboring under the weight of the false consciousness whose last vestiges Dad didn’t get around to shaking off before he got busy raising his own family and going back to school and stuff like that.

Looking back, dad isn’t exactly turning his back on feminism, but he’ll admit this wasn’t the idea.

Since I don’t want to write an essay of examples, I’ll just skip to the end: A few highly-independent individuals (like my dad) can use “Do what works for you” as a guiding ideal. For everyone else, we basically get to choose a fuzzy ideal, and have society copy it. We can have patriarchy for everyone, or feminist gynocracy for everyone. There may be a third option, but it won’t look any more universally unobjectionable than the first two.

It’s not so much that my dad can beat up your dad as that if you want to move society, fuzzy ideals is how you do it. You can try move it with abstract principles, just like you can try to teach a pig to sing. So your options are going to be fairly limited.

Two objections:

How does the fact that men and women are expected to have similar life goals imply that we live in a gynocracy?

Why do you think marrying someone who makes enough money that you don’t have to work should be considered a respectable life goal? It certainly doesn’t sound like one to me.

“Gynocracy” is just a term of abuse to go along with “Patriarchy.” If you prefer a different term of abuse, that’s okay with me.

Your other objection is a straw man. You’ll have to at least plate him if you want me to take you seriously.

Why do you think marrying someone who makes enough money that you don’t have to work should be considered a respectable life goal? It certainly doesn’t sound like one to me.

Ah – a sufferer from feminist false consciousness.

Let’s rephrase: Why shouldn’t women aspire to marrying a man who is successful enough to allow them to spend all the energy necessary to raising their own children, rather than having to hire people with less attachment to their children to do that work for them? And incidentally, have children who hopefully have inhereted some of the characteristics which made that man successful?

The example isn’t supposed to be the point here, but since I have yet to find a way to approach my opinion on the larger topic that doesn’t require I coredump my worldview, might as well address the example.

The phrasing of the dichotomy was deliberately over-polarized, ala characterizing the abortion debate as baby-murderers vs. woman-haters. He’s implying there is no happy medium that doesn’t make someone in the space of colourable mainstream views declare you evil for having encouraged a social order that stomps all over their desires. My interpretation is this.

People do not intrinsically know what they want. They must either rely on received knowledge of what “people like them” want, or they must absorb substantial opportunity costs of one form or another in order to experiment with different life plans until they find one that fits better. “Do your own thing” is commonly held up as an ideal and in the ideal person’s best interest, but it does not scale because it is only the very well-equipped (cognitively, financially, socially, whatever) who are able to eat the opportunity costs involved in determining what they want from a broad range of possibilities and come out ahead by doing so. For everyone else, the advice is bad, and executing their society’s best guess for people like them (or selection from a narrow range of best guesses) is in their best interest instead.

Now historically, this was rarely a problem, because society’s best guess was nearly always right. Survival bottlenecks dominated the equation, maintaining the supplies of food, clothing, shelter, and bodies required rounds-to-all of humanity’s available labor, and virtually nobody could take on the costs of exploring non-default possibilities. In this context, strong gender roles, professional heredity, multi-generational clan marriage contracts, and similar constructs that feel like rank violations of personal liberty from a modern perspective were instead the legitimate results of a necessarily risk-averse optimization strategy: Women shall ensure disaster-resistant replacement-rate fertility and perform other compatible tasks. Men shall follow their father’s trade and marry their mother’s niece. Our search depth is terrible but by committing to this paradigm we’ve freed up enough resources that we don’t starve too much and we can slowly search for improvements. Technological change alters these constraints, with social change following as the dominant strategy is renegotiated.

And through that system we slowly get to the modern world, where all those survival constraints are gone, and our search depth is incredible, and we devote the resources to pick out who’s inclined to be surgeons out of the field of people inclined to be doctors that we picked out of the field of people inclined to be technical that we picked out of the field of people inclined to grasp abstractions well… but we’ve still got some problems. Three of them, specifically.

Firstly, remember that awful, dumb, search depth-1 survivalist algorithm we started with? Well the bad news is we used it for so long that we reshaped ourselves to use it better. Inability to identify the dominant strategy is existentially distressing, and when we see other people who are failing to comply with the dominant strategy we want to gang up and shout at them, and when we meet a gang of people like us shouting at us to follow the dominant strategy we’re inclined to agree.

Secondly, the perceived dominant strategy is laggy and therefore historically contingent.

Thirdly, when I said we’d gotten rid of all our initial constraints, I was lying. We still need disaster-resistant replacement-rate fertility.

Enter feminism, which has taken up the unenviable responsibility of trying to renegotiate what we consider the dominant strategy for women while subject to these constraints. What we want is a new default division of labor that lets people find what’ll make them happy and productive without expending extraordinary effort or wallowing in self-doubt ever after, avoids demographic crises, and doesn’t heavily hinge on the historical accident that we solved the problem of farming being really hard before we solved the problem of clothing requiring continuous intensive maintenance.

What we tend to get in practice is tactical abuses of Problem 1 to declare my personal preference the new default and enforce that by ganging up on anyone who doesn’t agree.

I basically like this, but:

>”(…) when we see other people who are failing to comply with the dominant strategy we want to gang up and shout at them”

We do? Why? This doesn’t look realistic to me. Looks like it’s lacking moving parts, a couple of gears missing between “see people failing to comply with dominant strategy” and “want to shout at them”.

Wait, are you arguing that we don’t enjoy exerting peer pressure, or are you asking me to explain why/how we enjoy exerting peer pressure, or did you just not recognize that as a description of peer pressure?

Well, it has been argued that humans have a well-developed Cheater Detection module as part of our survival algorithm (quite useful in negotiating reciprocity and repeated Prisoner’s Dilemma scenarios), and that module might identify certain non-compliers as defectors or parasites (sometimes rightly so!)

Irrelevant, I was looking for some response like Svejk’s.

If our “cheating-detection” mechanisms, for some reason, activate in response to “people failing to comply with dominant strategy”, that’s one missing gear found.

But then, why *would* that activate our cheating detection mechanisms?

Ah, in that case, yeah, Svejk has the right idea: We have an evolved tendency to find judging people intrinsically rewarding, which took hold because it functions as a hardware hack that rigs a bunch of complex coordination problems towards reaching the right answer. This allows immensely useful, society-enabling things like altruistic punishment to function by default, rather than requiring everyone to be inducted into some sort of explicit bargain.

As to your second question, it works on optimization failures rather than just defections/sins because the mechanism involved isn’t very specific, and seemingly triggers on a sense of “you’re doing something wrong” that’s more like “you’re violating my category-informed predictive model of you.”

>” it works on optimization failures”

Oh, now I see it. I was looking at it as punishment for defection, and it just wasn’t clicking (incidentally, “cheating detection” looks wrong now).

Nice. I see the gears connecting self-optimizing through empathy/mirror neurons into other-optimizing; getting annoyed when you see people behaving sub-optimally would then be analogous to flinching when you see someone get hurt.

And/or: whatever it is that makes us imitate and learn from others might “try to process” behavior X but reject it as stupid, generating dissonance and annoyance.

But I don’t know what I’m talking about, and will update my reading list.

Yeah, I’m not sure on that part either. We’re looking at the system that generates contractualism-like social models in hardware without requiring you actually convene the contractualist congress. Reciprocity and contractualism are obviously related, and when I’m blackboxing I want to assume as few internal mechanisms as possible, so my initial guess would be that “cheater detection” uses the same system.

But on the other hand, altruistic punishment is as far as we can tell human-specific, so we’re talking about a very new innovation, while other animals can still pull off simpler forms of reciprocity. And the emotional signals on observing defection and on observing atypical behavior feel somewhat different, in a way that’s probably not just one being an attenuation of the other. So my best guess is that “You’re being unfair!”and “You’ve gone insane!” do use different systems. (Sanity check: if they’re different types of bad, an alignment between them should feel even worse. And… yep, treason gets you an extra-special circle of hell.) I acknowledge, however, that I’ve got a lot of social programming telling me that individualism is a good thing, so it’s possible that I’m wrong and if I lived in circumstances where there were no mixed messages on the matter, I would feel moral signals from conformity failures in the same way I do cheating. So I’m unsure.

A+

There’s certainly a fair amount of that, but it’s not clear to me that these people (I’ll call them “Feminist Kants”) are the reason why we can’t have nice feminism.

My intuition here is that the way you communicate the renegotiation to society is by saying “Here is Sally. She is a woman who has a career. This is good. You should be like Sally.” If you try to make it complicated like “Sally is good, but so is Betty who is a housewife, because Sally & Betty’s respective natures fit with those social roles” society can’t hear you over the clamor.

As much as I’d like to blame it all on horrible Feminist Kants, I don’t think the problem is their fault. Or maybe it is in the sense that they made an impact which was the only impact which could be made. But reasonable people could have believed that all of the views put forward would be considered by society, and the best overall one would be accepted.

You’re of course right that it’s more complicated than that and especially that it’s harder to assign blame. The whole line of reasoning is based on taking an ennobling high-agency approximation of humans that offers a sort of ceiling function to people’s behavior but is not in fact correct. Morality and blame are a particularly weak area of correspondence because the model assumes path invariance, while morality is all about path. If the king declares a law you dislike, responding by giving a speech that moves him to recant, by murdering him and installing a new king, or by starving to death are all considered “negotiation” moves that, to the extent that they generate the same effect on how people act in the next generation, are equivalent actions.

So when I spoke of tactical abuse, I was doing it at an abstraction level that groups together both “Actor A comes up with a plan that makes them happy, realizes it would do terrible things if generalized, and advocates universal implementation of their plan” and “Actor B comes up with a plan that makes them happy, pre-wonders for a moment if it would do terrible things if generalized, recoils from the line of thought because it gave stressful feedback, and advocates universal implementation of their plan.” That, when they say they think their plan is good for everyone, A is lying and B is mistaken doesn’t make a difference, because they’re sending the same incorrect signals and externalizing the same costs onto everyone else.

I agree with how the communication tends to function but not why it seems to be failing. What reasonable people seem to have believed starting off was that the ideals could diversify without persistent conflict. That is, that deciding whether you were a person like Sally the Businesswoman and should imitate Sally or a person like Betty the Housewife and should imitate Betty would be relatively simple. And they had good evidence for this, because on the male side visions of success aren’t in bitter conflict. We have a lot of competing ideals but people can mostly figure out which group has the people they’re more like and be OK there. There’s status competition between groups, to be sure, but the soldiers don’t feel a need to convert all the bankers into soldiers, and the bankers don’t feel a need to convert all the soldiers into bankers, and no man’s publishing articles anguishing over the fact that they failed to become soldier-bankers and whether this means they’ve let down their gender. And for some reason this hasn’t turned out to be the case on the women’s side yet.

I am three chapters into Harry Potter and the Methods of Rationality and so far it is one of the best things to ever happen to me, fiction-wise.

One can only imagine how delighted Stella will be when she discovers science fiction novels. Or non-science fiction novels.

Scott, do you suppose you could do something to discourage the degree of hero-worship we’re seeing from your commentariat? It’s kind of worrying. These are smart kids you’ve got here, and they’re not broadening their horizons. I can try trolling harder, but I’m not sure it’s working.

You mean fantasy novels, right?

I mean kumquats, the concept of doubt, or a blurry polaroid of someone you loved passionately who died too soon.

Remind me again what’s wrong with liking a really good book?

(I doubt it’s hero-worship; if Stella’s only 3 chapters in right now it means she hasn’t been following along and probably doesn’t even know who Eliezer is)

You think HPMoR is a really good book? Not like, amusing, a bit educational, or a better way to spend your time than petty theft and drug abuse, but really good? I guess I have to revise my opinion of one of you…

Maybe I’m reacting too strongly, but I’m seeing a pattern of people getting, in my vainglorious opinion, too attached to certain members of the rationalist community as individuals, as opposed to somebody who has produced good thoughts and will probably do so again.

There was that medical student kid who said, forget going around to medical student forums and asking lots of different people for their advice, and attempting to somehow synthesize this information into an informed decision. I’m just going to ask Scott, and his views will determine my decision. He’s like a rationalist medical-resident God!

Maybe that’s not totally accurate. Maybe what level of devout following you get is natural given the effort you put into this blog and the quality of it. Maybe you have too much responsibility as it is to worry if people are taking your opinions too seriously. I’m not totally sure. I just get a weird feeling occasionally. I’ll take two asprin and call you tomorrow.

Dude, do you even availability heuristic?

Of course you’re seeing a lot of “Woo Yay Eliezer” and “Woo Yay LW” etc on here. You’re here.

I don’t really care about Eliezer but all I can say is that I’m reading three things currently, HPMOR (as of yesterday), Better Angels of our Nature, and an apparent classic of English language literature, Ulysses, and I’m finding myself wanting to read HPMOR more than the others.

I’m not going to argue its great literature, but then neither is the source material. It is, however, amusing and enjoyable and makes me want to know what happens next and that surely meets at least some definitions of “really good.”

Taste is entirely subjective, remember. I’ve read LOTR twice and found it incredibly tedious both times.

I have a friend who considered Eliezer a hack, was not much of a fan of Harry Potter beforehand and who has very little tolerance of things he deems low quality.

He finished the entire story in a week.

Now, I’m not actually much of a fan of the story (the prose could use a lot of work, there’s a complicated plot but not a theme), but I find it hard to believe that you can’t give it at least as much credit as a page turner, that works on people who aren’t completely turned off by EY’s stupendous status blindness.

I think it’s worth remembering that lots of people in Less Wrong spheres have a STEM background and minimal interest in literature. To open a novel and find critical thinking + wizards might be something of a revelation.

Something like 1/4 of Less Wrong survey respondents were referred to LW by HPMOR, not the other way around. So a lot of people like HPMOR on its merits (whatever they are) rather than liking it because they are “too attached to certain members of the rationalist community as individuals.”

To open a novel and find critical thinking + wizards might be something of a revelation.

For that, put Y’s Harry into iirc _The Flying Sorcerers_, instead of assuming a Hogwarts faculty with no common sense.

I agree with a lot of this (while still having a high opinion of the rationalist community), but it’s silly to conclude that anyone who thinks HPMOR is “really good” is hero-worshipping. (Even if only someone with bad taste would think that, bad taste is different from hero worship.)

The prize for adding value to the discussion goes to BD Sixsmith.

Anyone who wants to beat this dead horse further should keep in mind that the words complained of were “One of the best things to ever happen to me, fiction-wise.” “Really good book” was Scott’s more measured description.

I think it’s worth remembering that lots of people in Less Wrong spheres have a STEM background and minimal interest in literature.

Minimal interest in literature.

This sentence as a whole makes me sad and that part makes me cry 🙁

It’s like saying someone has eyes but would never bother even looking at Botticelli’s Pallas and the Centaur because pfft, centaurs aren’t real!

C.P. Snow’s The Two Cultures is alive and kicking still, and even worse because STEM fields are more than ever considered to be the Only True Way of knowing anything or helping make life better, while the humanities are the equivalent of putting gilt on gingerbread.

“You think HPMoR is a really good book? Not like, amusing, a bit educational, or a better way to spend your time than petty theft and drug abuse, but really good? I guess I have to revise my opinion of one of you…”

I don’t know how to answer this.

I’m aware that The Great Gatsby is supposed to be an amazing brilliant literary classic. I’ve read it at least twice, and although I get the themes it’s trying to talk about and I feel like I understand it on the same level as the people writing the “Understanding The Great Gatsby” guides, it doesn’t do anything for me. It doesn’t excite me. It doesn’t move me. It doesn’t teach me anything about life. Give it to me alongside an agreed-to-be-mediocre story about 1920s rich people doing 1920s rich people things, and I won’t be able to tell much interesting difference.

On the other hand, HPMOR did excite me, to the point where I would religiously read each update the day it came out. And it did move me, to the point where I cried at the points where I was supposed to cry and felt uplifted by the points where I was supposed to feel uplifted. And it did teach me things (or at least it would have if I hadn’t read Eliezer’s previous presentations of the same ideas). It’s certainly not unique in this – Asimov, Pratchett, Carey, etc are other authors who can do this to me – but it was part of that group.

Does that mean HPMOR is better than Great Gatsby. I know I’d be lynched if I said it was. So all I can say is that I see a lot of evidence that there’s something called “great literature” such that people who can appreciate it get more out of great literature than I get out of anything, and it’s an extremely difficult technical challenge to produce great literature that should be celebrated when someone does it right – but that I lack the knack for it.

But if I had to remove either Gatsby or HPMOR from my own life, it wouldn’t even be a hard choice.

This isn’t because I’m uncultured – I wouldn’t be surprised if I’ve read more great classics than the people who are going to show up to mock me here. And I’m not totally dead-set against the literary establishment – I have very strong appreciation for classic poetry, such that I can admit that eg Tennyson has done something I wouldn’t expect one in a million people to be able to replicate, even including Eliezer. It’s just that the great works of prose don’t do it for me.

Also, I strongly reject all of this “Less Wrongers, as STEM nerds, don’t know anything about culture or literature” stuff as rank stereotypes. I am consistently impressed with how much “STEM nerds” know about history, literature, and culture. The SSC meetup in San Jose, the heart of Silicon Valley, devolved into competing to see who could recite more Kipling poems, and debating the causes of the fall of the Roman Empire.

I am consistently impressed with how much “STEM nerds” know about history, literature, and culture.

Would like to be clear that I said “lots of people” and not “all” and did not say “nerds”.

I don’t think people necessarily lose out by being uninterested in literature any more than I lose out by being uninterested in maths. There are always going to be sciency types and arty types for the simple reason that the hours in a day are finite and so are the interests in a life, and it takes a special kind of person to learn quantum theory and read the canon. (The kind of people one might at SSC meet-ups in San Jose.) What societies need is for the interests of different people to complement each other so that they can form a collective wisdom.

@Scott:

You answered correctly. If you wanted to say “HPMoR is a really good book, like Scoop or My Man Jeeves” I’d say you could make a case for that (although there’s no way it’s better than Scoop).

Then you know cool STEM nerds, and I’m jealous, but part of me is also incredulous. I’ve met cultured STEM nerds too, but not many. I’m confident the stereotype is accurate. But then, most of them are.

1. I have, in fact, read *lots* and *lots* of books, in a variety of genres though fantasy and science fiction have been my favorites.

2. When I said that HPMOR was one of the best things to ever happen to me fiction-wise, I was exaggerating for comedic effect. I was, after all, only three chapters in. I am enjoying it, though.

3. I haven’t finished it, so I can’t judge whether it’s a “great book” or not. I’m not sure I believe in the concept of “great books” per se–I may be a book relativist. That being said, I think it has clear prose, strong character work, and page-turning plotting. The humor fits my humor, and if it’s insaaaaaaaaanely preachy at least I mostly agree with it’s sermons. I also appreciate how it relies on its readers having a detailed knowledge of the original books fueled by childhood nostalgia (the first HP books came out when I was 7, making me the perfect age for them) so that you can appreciate the hints and allusions and ways the originals have been slightly twisted. Similar things have been done, of course, mostly to fairy tales and mythology, but the HP books are huge books full of details, giving more opportunities for twisting. I’m finding that an extremely pleasant experience.

4. I do not know who Eliezer is. He’s the guy who wrote it? Whatever.

Scott: That is literally exactly how I feel about The Great Gatsby. The only thing that moved me about it was the poetry of the language, though even that I find exhausting after a while. I, personally, like my poetry short as a punch. (Similarly, I like Faulkner’s *sentences* and his *paragraphs* but not his *novels.*)

Great Literature improves the world, and has truth and beauty it it. However, I have always detected a strong dose of tribal signaling (a.k.a. snobbery) in those who not only love Great Literature but scorn those who aren’t as inclined to it. All groups do this, of course. I’m a chemical engineer, and in college we would laugh about how much easier the civil engineering course was and also about how much more socially adept we were than the electrical engineers.

The Great Literature snobs have always annoyed me particularly for all the usual reasons one group of snobs annoys you more than another.

Metasnobs are the worst.

Don’t get me started on metametasnobs, Airgap.

What I read of HPMOR screamed out to me “this is wishful thinking where you can be right but not have any social skills, and actually get away with it”.

(And Harry is only even right by authorial contrivance. If his ideas worked, someone would have already been implementing them; if not, there’s probably some reason why they don’t work which involves knowledge he’s unaware of.)

It turns out Harry is wrong in a lot of the things he thinks. “Harry overestimates his ability to do things” is a really important theme in the story.

You should try reading Eliezer Yudkowsky’s Abridged Guide to Intelligent Characters.

A possible motivational mindhack I have accidentally stumbled on:

The door to my office at work used to have an extremely difficult lock that required a bunch of finesse to get open. A couple of years ago, they replaced the lock with a new one that is much easier to work. Yet even now, I still get a substantial sense of satisfaction from getting the door open, as though I’ve pulled off something requiring a significant degree of skill (a not totally inaccurate description of getting the old lock open).

So if you’re faced with a necessary routine task you’re not particularly motivated to perform, it may be possible to get a long-term increase in the dopamine reward your brain releases by temporarily adding complications that make the task harder.

So, I’ve just started reading HPMOR and I’m enjoying it so far, finding it laugh out loud funny and so on, but does Harry get any less irritating? I just want to give him a well deserved slap around the head at this point (I’ve read 12 chapters).

I never found him particularly irritating, but his behavior does change pretty significantly as the story morphs into more of a… well, story, instead of just straight deconstruction. Also, see this: https://www.facebook.com/yudkowsky/posts/10152305725324228

Thanks for the link. That’s the chapter I bailed at, but not so much for the status reason that others gave. I thought the author was making McG (and Hermoine in a previous chapter) very stupidly stupid; trashing good characters. If he wanted to show HP being smarter, he should be smarter than their best state, not smarter than their cartoon flat versions.

I sort of tolerated it with Hermoine, who was another student, and it was sort of reasonable to use another student as a Watson. But making the experienced teacher just plain dumb? As for respect, it seemed that H was deliberately being mean to McG, who might reasonably have felt bad when he did it.

Iirc on an afterword to that chapter, EY said dropping anvils on characters came along with first draft inspiration. If he ever rewrites it to clean out that sort of thing, I hope someone will let me know.

Thanks for that. Since I wrote that comment I have read another couple of chapters and he’s grown on me slightly.

As I said, I’m enjoying it (although I actively disliked chapter 6 nor was I a huge fan of the sorting hat chapter), but I don’t think I could have read over 100 chapters with me wanting to strangle Harry to within an inch of his life before Obliviating him so I could do it all again next week without any consequences. I’d happily just give him a couple of well timed pies in the face at this point.

No, he only gets worse. However, if you can manage to ignore him, it can be entertaining.

@scott: if you blocked my last comment for language choices, I’m happy to clean it up a bit.

It got auto-blocked by the spam filter for language. I un-auto-blocked it for you.

Can I complain about something about social justice for a bit? I work in a field of academia where there are a lot of social justice types, and it’s very easy to get “called out” for saying very ordinary things on the professional blogs. For example, I’ve seen people told they were being ableist for saying an idea is “crazy” or for using the phrase “blind review” to describe anonymous refereeing.

This gets to the thing I find strangest about call-out culture: People within this culture often seem to think that violations of even very controversial and arguable ethical principles ought to be called out. These are principles accepted by only a tiny segment even of progressive academics.

That says nothing whatsoever about the truth or falsehood of these principles, of course. But it seems to me that it does have import for whether it makes sense to call people out. My vegan friends don’t publicly call me to account whenever I drink milk in their presence. I think they’re making the right decision by not doing so, and I thank them for it.

(Of course I’m always happy to have a substantive discussion about whether some controversial ethical thesis is right. What I find odious is being on the receiving end of social opprobrium for holding the nearly-universally-accepted opposite view.)

Well, sure. That’s where the money is.

The way they see it, there’s no real need to call out views which are well beyond the pale of the right side of the overton window.

A: “Slavery is too good for subhuman nigger scum. They should be executed to a man, cremated as a body, and their ashes shot into space, to ensure future scientists are unable to clone them from traces of their DNA.”

B: “Whoa, dude. Not cool.”

Person A is already effectively excluded from the conversation, or at least the one carried on by people with any power. Also, a combination of social and cognitive stratification as well as their own discrimination as individuals ensures that SJWs will never meet anyone like Person A.

(Note you can replace “SJW” with “Stormfront Poster” and that sentence is still accurate.)

By contrast, calling people out over controversial points advances the SJ cause.

Why would they? A true-blue activist will see this as like having a philosophical discussion with an enemy soldier over whether you’re allowed to shoot back at him. Having such a discussion admits that there’s a discussion to have. If there isn’t, his position is stronger.

You’ve probably selected your friends carefully for qualities like basic human decency. SJW scum comes in “vegan” too.

If Social Justice was your boyfriend, I’d tell you to quit complaining and dump him because he’s an abuser and he definitely won’t stop if you keep indulging him. I don’t mean you need to change your views (that can wait), but is it impossible to escape your present toxic SJ environment? Are there doors, for example?

You mention “Progressive Academics” though, which makes it sound like you’ve chosen to place yourself in a position where SJW abuse is normal and tolerated, possibly without having considered this fact, and you probably cannot leave without abandoning a significant investment. I don’t really know what your options are, but I suggest you consider them. Maybe you can find a department with fewer assholes. It’s worth a shot. And if none exist, that’s worth knowing.

It’s very far from being a problem that would ever make me consider changing my field (which I love). It’s more of an annoyance that keeps me away from certain issues on certain blogs. Doesn’t happen much in person.

I meant “Department” in the sense of “University” rather than “Field of study.” Like, maybe the faculty of Walpolo’s Chosen Field at Columbia is saner than the one at NYU. You don’t go nuclear until you’ve ruled out conventional warfare.

[deleted]

Scott, and anyone else interested in psychiatry and deinstitutionalization, I recommend Clayton Cramer’s My Brother Ron: A Personal and Social History of the Deinstitutionalization of the Mentally Ill.

Cramer is one of the people who discovered that Michael Bellesiles was making shit up, and documented how and where Bellesiles was wrong. He later wrote a book about it, which is a cross between a history of guns in the US and a prosecution brief against Bellesiles; My Brother Ron is as meticulously footnoted as the previous book. There are some fascinating bits of history in the book, and it does a great job of explaining how we got to the point of using urban alleyways as our primary housing for the severely mentally ill.

Scott, I don’t know if you take post topic requests/suggestions. On the off chance you do, here is one (or perhaps two, if you want to split it up).

You often write about Less Wrong, and sometimes also about Eliezer Yudkowsky, who I understand to be the main person behind/author of material on LW, as well as a personal friend of yours. When you write about it, you often write as if everyone who reads Slate Star Codex reads/is involved with LW. Personally, I’d never heard of it until I began reading your blog a few months ago, and still haven’t done more than poke around the site a bit, and google a bit.

So what I’d love to see is Scott’s Guide to the Less Wrong World, and/or Scott’s Personal Story of His Involvement with Less Wrong & Eliezer Yudkowsky, or both combined into one. Basically, I’d love to hear what you’d have to say about the site and/or the person behind it to people (I’m guessing I’m not the only one who reads SSC?) who don’t know much if anything about it/him.

This was prompted, by the way, by following the link to the Vice article in the main post. It implied a certain cultishness to LW, which I gathered from googling is one of the main lines of its detractors. So I was a bit surprised (only a bit) that you linked to it. If you wanted to address this (apparently) common perception — and certainly a perception that a quick google on Eliezer Yudkowsky and Less Wrong leaves, rightly or wrongly (I presume you think wrongly) — I’d love to hear about that in particular.

Thanks!

I’d also be interested to hear about how Scott got involved with Less Wrong. I’ve tried (and I’m still trying, slowly) to become acquainted with the site, but I have to admit that I’m finding it difficult. The Sequences do not make for particularly easy reading, IMO.

The Sequences were much easier reading when they were published as a blog post a day. Someone reading the SSC archives would probably have a hard time of it too.

I only started reading SSC less than a year ago, though, and I don’t have the same problem with it. The “best of” page is great for getting up to speed on the most important posts, and there’s a clearly ordered archive where I can go back and read posts in chronological order.

I think some of the problems I’m having reading The Sequences have to do with the format I’m trying to read them in (one of the e-book compilations). Organization/ordering is a big problem with the particular compilation I downloaded, and it also hasn’t really been cleaned up to work well as an e-book; there are still links all over the place that point to the original posts, which don’t work well on my Kindle. I hear there’s another e-book compilation being published soon, so I’m hopeful that it will solve those problems.

The other problem I have, though, is that some (several?) of The Sequences are written as parables, and… well, I’m not opposed to parables per se, but I feel like they’re not the best format for a treatise on rationality.

Try ciphergoth’s e-book. It’s by far the best of the compilations. All the pictures are there, all the links work and take you to another part of the book rather than to a webpage, and all of the blog posts are included in a single file and listed in simple chronological order.

Thanks jaimeastorga2000. I’ll give that one a try.

Proper ebook exists! Can be purchased for as little as $0.00

http://lesswrong.com/lw/lvb/rationality_from_ai_to_zombies/

Also, you didn’t have Eli’s posts interspersed with a bunch of “Rationalist recipes for cupcakes” grade posts from the hoi polloi. Sure, Robin did post occasionally, but it wasn’t nearly as bad.

Your writing is clearer and less idiosyncratic than Eliezer’s.

Having read both the SSC archives (and much of our old blog) as well as most of the Sequences I disagree. Your writing seemed very clear. The sequences required alot of pain and effort to understand. In many cases I had to read a Elizier post multiple times (Separated by weeks or moths) o even really get what the main point was.

I could just be unintelligent but Luke M. also claims that Elizier’s writing is impenetrable to him. And Luke is not dumb.

I would be very surprised if an intelligent person had alot of trouble understanding Scott’s writing. But tons of intelligent people report great difficulties in understand Elizier’s posts.

I guess I sort of already said it above, but I will third this, and I consider myself at least reasonably intelligent – although perhaps only average for the SSC crowd. 🙂 I’ve only read a handful of the Sequences and there have already been several where I felt like I just wasn’t getting the point. I shall continue trying, though.

FWIW, the Ebborian story during the Quantum Physics Sequence really threw me. Otherwise, I felt both you and Eliezer were pretty clear.

Also. When I stumbled across LW, I didn’t really follow any of the sequences at first. I just kinda followed Eliezer’s links wherever they would take me. Like I would do with TV Tropes, or Wikipedia.

I think also when the communit was more active and people like you and luke[rg were regularly posting ood articules with links back to sequences that made it easier to get into

I’m a bit surprised by this thread.

I thought the sequences were easy enough to read, and quite pleasant. Exceptions: the QM sequence (but that’s on QM, not Eliezer, and he made it easier than I would have expected), and the metaethics sequence (I think EY gets weird when speaking of ethics, but then again who doesn’t).

I’m not sure what it’s being compared to, but I can’t think of more readable sources that deal with similar subjects (Scott is wonderful, but his preferred subjects are easier to communicate, I think).

Also, I think Scott’s style produces the illusion of agreement more than Eliezer’s. And maybe the illusion of comprehension. This might just be that Scott writes longer essays, while Eliezer’s short essays cause one to stop and assess more often.

The short version is that economist Robin Hanson and self-taught AI safety researcher Eliezer Yudkowsky started blogging about cognitive science and philosophy on the site Overcoming Bias in 2007ish. A lot of people liked their stuff, and so Eliezer spun off an online community sort of like a web forum called Less Wrong.

I started reading Overcoming Bias in 2008. When Less Wrong was formed I did a lot of the blogging there that I’m now doing here. When I got this site, a lot of people followed me over, so a lot of (most) SSC readers are familiar with LW.

People on LW often believe in unusual things like transhumanism and effective altruism, and they sometimes use a lot of idiosyncratic jargon (though I think we’re getting better at that). This has created a really strong in-group vibe, and so a lot of people formed real-life friendships and relationships within the LW community or even moved to the Bay Area where the community is strongest. This has led some people to joke that LW is a cult. It admittedly doesn’t help that many members are polyamorous, that some people like experimenting with “rituals” and “ceremonies”, and that Eliezer is constitutionally incapable of doing anything without coming across as hilariously over-the-top arrogant, and at some point instead of fighting it he just turned it into his style so that now it’s kind of hard to tell when he’s joking or not.

Aside from reading his writing and hugely respecting his ideas, I haven’t had too much personal interaction with Eliezer, although when I lived in the Bay Area in 2012 we sometimes went to the same parties. I just find him consistently insightful and interesting in a way very few people are.

Probably the best introduction to all of this you could get is to read the new ebook version of the original blog posts that started Less Wrong.

of the original blog posts that started Less Wrong.

Part of the “Cult” allegation stems from the incident where most of the staff of SIAI committed suicide via phenobarbital-assisted asphyxiation as part of a misguided attempt at “Mind Uploading.” Eliezer was not indicted in connection with the incident, but he was forced to sell the trademark to Ray Kurzweil in order to fund the creation of MIRI.

You do realize this will probably take some convoluted route to ending up on rationalwiki…

Good. If RationalWiki is going to be retarded, it may as well be entertaining too.

He gives you a shout-out in the Preface for being responsible for making LW a nicer culture.

Thank you for telling me this. I might not have found it otherwise, and it made my whole week.

Thanks for the reply! If you felt like talking more about your own personal experience/take (i.e. the sort of stuff that *isn’t* in the sequences), I’d love to read more.

How is “Eliezer is constitutionally incapable of doing anything without coming across as hilariously over-the-top arrogant, and at some point instead of fighting it he just turned it into his style so that now it’s kind of hard to tell when he’s joking or not”

distinguishable by anyone that isn’t Eliezer from

“Eliezer used to take steps to pretend he wasn’t hilariously over-the-top arrogant, and eventually just gave up trying.”?

Because I have to say from everything I’ve read (I’ve never met the guy), it sounds a lot like the second one.

May I recommend you read The Sequences? I would rate Scott Alexander as second only to Eliezer Yudkowsky as far as non-fiction authors go.

Just today, a proper ebook of the sequences has been published, and can be yours for as little as $0.00!

http://lesswrong.com/lw/lvb/rationality_from_ai_to_zombies/

Maybe that’s a proper ebook and Jaime’s second link isn’t a proper ebook, but at least it’s a proper server. It will take me at least 10 minutes to download from your link and determine what you mean by “proper.” That’s a lot more than $0.00 of my time and attention.

Proper, as in “put out by MIRI, oh, and we also reorganized the content so it reads like more like a 333-chapter book rather than a series of blog posts, added some new content, and edited the old stuff where necessary.”

All of which you would’ve known had you read the link.

All I’m saying is that your link is crap and that everyone should use Jaime’s. Sorry if I implied I cared what you meant by “proper.”

You may be interested to know that the author of the non-crappy version suggests everyone read the crappy one.

You should read Terry Pratchett’s book of essays, A Slip of the Keyboard. Pratchett is just as good a non-fiction writer as he is fiction.

…er, was. ;_;

<_< Buuuut I'm kind of hugely devoted to him and still in mourning, so I may be biased.

How many non-fiction authors have you read? I have a lot of respect for both Scott and Eli, but come on.

> I would rate Scott Alexander as second only to Eliezer Yudkowsky as far as non-fiction authors go.

I agree with those words, but not their order.

But, Ancient, what does “Scott Yudkowsky would only go as far as I to rate Eliezer Alexander non-fiction authors as second” even mean?

His intended meaning was obviously “Go second! As Scott Alexander, I only non-fiction authors – would Eliezer Yudkowsky as far as to rate?”

Has anyone been as far as to rate?

I figure TheAncientGreek has a more logical mind, and his intention is clearly “Alexander as as as authors Eliezer far go I non-fiction only rate Scott second to would Yudkowsky.”

Sorry, _all_ non-fiction authors? How much non-fiction have you read?

—

re: “cultishness.”

A certain inability to look past one’s nose (like the parent post) is one problem in the community that I see a fair bit.

Eliezer’s ego/acting like a guru is another problem. I am sure some of it is a kind of inside joke … but can you really do that? If I act like an asshole online, for example, can I just say “actually it’s just an inside joke between me and my friends.” No, I think it just means I act like an asshole online.

—

I find myself criticizing the rationalist community a fair bit, which is kind of a shame, because I find much value in many rationalist ideas. I just find the social dynamic extremely off-putting, and I think folks whose cultey sense is tingling are completely right.

I’ve posted here a few times about my anxiety problems, and after many ineffective stops on the med-go-round, combined with semi-effective psychotherapy, I’m still looking for a better solution. Today I saw an ad for this device. I immediately assumed it must be a Scientology-level scam: I’ve never heard of it before; no doctor or psychiatrist has recommended it to me; and it looks like a fucking stud finder.

But then I started reading and saw that there are apparently multiple published studies supporting its efficacy, and that it is “FDA cleared.” It also requires a prescription to purchase. I haven’t read any of the studies myself yet, and given my limited knowledge of medicine and biology, I don’t know that I’d be able to spot any methodological errors or even blatant factual falsehoods.

I’m still very skeptical about this device, but anxiety really sucks, so if there’s even some real evidence behind it, I might be willing to try it… even with the hefty price tag. Can anyone here with more expertise (*cough* Scott *cough*) comment on whether or not this thing might be legit?

I’d never heard of this. A brief search turns up this article in which the FDA rejects it because “The Agency reported finding mixed results and problems in study size, design, and methodology. The reviewers concluded, that the FDA believes the available valid scientific evidence does not demonstrate that CES will provide a reasonable assurance of effectiveness for the indication of insomnia, depression, and anxiety.” Wikipedia sounds similarly unimpressed. And the anecdotal reviews I am seeing online are a lot of “it did nothing for me”.

This doesn’t seem like a complete scam – in theory it’s the sort of thing that might work and it does have some intelligent people behind it. But if you’re after highly theoretical things with only a smidgeon of evidence, I bet you could find much less expensive ones.

Thanks Scott! I have to admit that wasn’t the answer I was hoping for, but as the litany goes, “if the box does not contain a diamond…”

Words can’t express how much appreciate you spending your own time to look at these sorts of things for me. Truly. I doubt I’ll ever be able to repay the favor, but if there’s anything I can do for you, let me know.

Several people including Scott have suggested inositol as surprisingly good for panic (but not if you’re bipolar). I tried some today with lunch and found almost immediate relief. Fwiw my anxiety all seems to be centered in my gut and the inositol made it go from panicky to kind of a numb fuzzy feeling that lasted the rest of the day. (The fact that my symptoms can be simultaneously severe and vague drives. me. bonkers.) I’ve used it a few times at around 0.5-1g/day.

Thanks for the suggestion! I will talk to my psychiatrist about it next time I see her.

(Something I’ve brought up before)

For effective altruists and consequentialists and utilitarians: how does the “impartial care for all humans” part of those philosophies doesn’t work well with our natural tendancy to care more for our friends and family?

For me, this is why I don’t consider myself a consequentialist / utilitarian, unless I take a very loose interpretation whereby I’m an “utilitarian for my utility function”, and my utility function values people “close to me” more strongly, with decreasing circles of loyalty.

This is entirely compatible with consequentialism, although not with some formulations of utilitarianism.

> “utilitarian for my utility function”

That is certainly a way to align your morality and your intuitions.

You can also just claim that you’re an utlitarian and also a bad person.

Utils for the util throne!

I think a world without friends and family would be a sad one. And importantly, I think pretty much everyone in the world would agree with that. So any ethical theory that tells us to do away with friends and family is to my mind a flawed one. If we were to somehow find the “correct” theory of ethics (whatever that means) and implement it, I suspect it would make some people sad at the expense of others (in fact it’d pretty much have to). But it shouldn’t make *everyone* sad – that would be absurd. In what sense is it even an ethical theory then? Ethics exists for humans, not the other way around. That’s why I (tentatively, anyway; always tentatively) identify as a consequentalist contractualist.

There’s no incompatibility with consequentialism or with some formulations of effective altruism (though it is incompatible with utilitarianism) I don’t care about all humans impartially, and I care about those close to me more than I care about strangers. But when I help someone, I want to spend my resources as effectively as I can.

So they turned the Sequences into an ebook: http://lesswrong.com/lw/lvb/rationality_from_ai_to_zombies/

I may be unreasonably excited about this.

Now… how do I get people to *read* it?

…actually, this is really good news to me.

Last week I downloaded the crude ebook made of Yudkowsky’s blog posts from 2006 to 2010, since the main reason I haven’t read most of the sequences is lack of time/convenience. But the million-word project was mighty daunting and I have made little progress given the size of my reading list.

I’ll read this one instead.

I’ve been waiting to put this on a coffee table one day. Then hopefully one of my friends will casually pick it up while I’m in another room, leaf though it, and ask to borrow it. I suppose I should get around to reading HPMoR too. I decided to abstain until after it was completed. And I’ve never even picked up Terry Pratchet. So much to read … yet so little time. 🙁

+1

Does anyone know how substantial the edits and changes were?

I’ve been meaning to post this in an open thread for a while!