Related To: You Might Get What You Pay For, Do Life Hacks Ever Reach Fixation?

Here are three interesting psychological studies:

1. Kirschenbaum, Malett, and Humphrey gave students a three month course in how to make monthly plans, then followed them up a year later to see how well their grades were doing. The students who made the plans got an average GPA of 3.3 compared to the students who didn’t getting 2.5. They concluded that plan-making skills are academically important, and that benefits persist at least one year after completion of the plan-making course.

2. Aronson asked Stanford students to write a letter to a middle school “pen pal” urging them to adopt a “growth mindset”. Since this was a psych study, it was all lies and there was no pen pal; the study examined whether writing a letter urging growth mindset made the students themselves have a growth mindset and whether this improved grades. Three months later, the students who wrote the letter had higher GPAs.

3. Oaten and Chang helped undergraduates set up an 8-week time management program involving schedules and diaries. The students who participated not only had better time-management, they also studied more, smoked less, drank less alcohol, exercised more, ate a better diet, spent less money, rated their emotions as better, missed fewer appointments, and were less likely to leave dishes in the sink (really!).

So, remember a couple of weeks ago when I wrote about some psychiatrists conducting a really big (n =~ 1000) study about an early intervention program for troubled youth? A program that cost $58,000 per person and lasted ten years?

And remember how, although it was deemed a success, it was deemed a success because it had modest effects on a couple of outcomes, without improving the really big ones like school retention, employment, or incarceration?

So on the one hand, having a short discussion about making monthly plans will boost your GPA almost a whole point a year later. On the other hand, ten years of private tutoring and pretty much every social service known to mankind will do next to nothing.

This suggests a dilemma: either psychological research sucks or everything else sucks.

I mean, you tell your social engineer “Here’s ten thousand dollars and a thousand hours of class time per pupil per year, go teach our kids stuff,” and they try their hardest.

And then some researcher comes along, performs a quick experimental manipulation (the pen pal one probably took 30 minutes and 30 cents) and dramatically improves outcomes over what the social engineer was able to do on her own.

Then one gets the impression that the social engineer was not using their $10,000 and 1K hours very wisely.

And if it were just the one example, then we could say Carol Dweck or Roy Baumeister or whoever is a genius, the rest of us couldn’t have been expected to come up with that, now that we know we’ll reform the system. But these results have been coming in several times a year for decades. If we’ve been adopting all of them, why aren’t people much better in every way? If we haven’t been adopting them, why not?

My money is on the other branch of the dilemma. The reason the $58,000 study got so much less impressive results is that it was run by medical professionals to medical standards, meaning it only showed the effects that were really there. The reason psychology gets such impressive results is…

Okay. I have only skimmed these three studies, so I don’t want to make it sound like I’m definitively crushing them. But here are some worrying things I notice.

The first study results are actually limited to a small subgroup with I think a single-digit number of students per cell.

The second study results work only on a complex statistical manipulation and disappear when you do basic correlation; further, although the manipulation is supposed to work by increasing trait growth mindset, the correlation between trait growth mindset and academic achievement when correlated directly is actually negative across all variables and in some cases significantly so (!)

The third study is really about stress-related behaviors during an examination period, meaning that all they showed was that people who as part of their time management course were forced to study in a carefully scheduled way for a term show less stress-related behavior during the term exam period, which makes more sense as they probably studied more earlier, had less studying left to do during the exam period, had more free time, and were less stressed. This context was dropped by the popular science press, turning the study into proof that good time management in general always produced all of these effects.

And although there are several other studies I have not been able to find equally worrying flaws with, if they report massive long-term gains from seemingly minor interventions, I expect they’re there and I just missed them.

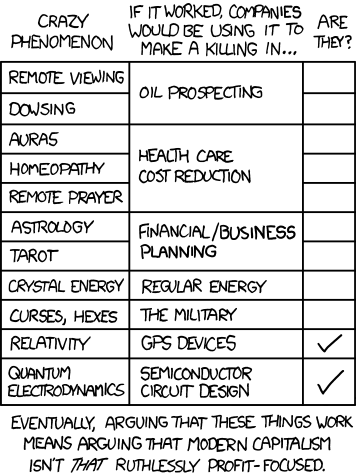

Basically, you remember this chart?

Source: xkcd

In “Crazy Phenomenon”, add “any large and persistent effect from social psychology”. In “If it worked…” add “education, rehab, and mental health”. In “Are They?”, add “not nearly as much as I would expect”.

Pingback: A week of links | EVOLVING ECONOMICS

Pingback: The Psychology of Lifestyle (II) « Econstudentlog

Pingback: Browsing Catharsis – 03.18.15 | Increasing Marginal Utility

Don’t you think that there’s a difference between college students and “troubled youth”? Comparing these two types of studies is comparing grapes and guavas. College students are motivated to improve because they want good grades, good degrees, and good jobs in a professional field. “Troubled youth” are… well… troubled; first they need to be convinced that good grades, good degrees, and a good professional jobs are both desirable and attainable. THEN we can start talking about plan-making and so on. I’m not a psychologist; maybe that’s why this sounds sensible to me.

Cargo cult science, the planes don’t land.

http://neurotheory.columbia.edu/~ken/cargo_cult.html

Perfect information is a prerequisite to successful economic activity.

A review of time management studies (warning PDF download link)(https://encrypted.google.com/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=2&ved=0CCkQFjAB&url=http%3A%2F%2Fwww.researchgate.net%2Fprofile%2FWendelien_Eerde%2Fpublication%2F228664480_A_review_of_the_time_management_literature%2Flinks%2F0912f509b55532ed03000000.pdf&ei=v-oBVc_qDsLnoAS_xYGwBQ&usg=AFQjCNERJ_05dY7BSguKjXjKvfUdUxcsGA&sig2=o9l9OZmMvjw3MRlaZxmwNg&bvm=bv.88198703,d.cGU

)

Found that time management systems had little impact on long term outcomes/goals but did have impact on short term stress/well-being.

slightly better version of link

So it strikes me, reading Scott’s descriptions of the studies (but not the linked articles nor the studies themselves), that they all “assign” a task to a group of subjects, and those who complete the assigned task are more likely to be generally successful later on.

Perhaps they’ve got the causation backwards?

When the benefits are largely uncaptured by the intervening agent, we can’t use the lack of “industrial use” as evidence against the existence of a intervention:

Consider spaced versus massed practice: We have strong evidence that spaced practice is better, but schools enforce the use of spaced repetition only haphazardly (e.g. not using basic software). Why?

Aww, the ending made me sad. I was all set to improve my time management skills.

Speaking of which, does anybody have a resource recommendation for a high performing deadline oriented procrastinator who wants to improve time management?

)(D)oes anybody have a resource recommendation for a high performing deadline oriented procrastinator who wants to improve time management?”

Apart from your mother standing there poking you with a stick going “Get to work, you lazy lump!”, no 🙂

>your mother standing there poking you with a stick going “Get to work, you lazy lump!”

I passed the point where that just makes things worse years ago. (Science, why have you forsaken me?)

I made another post that either is stuck in moderation queue because of the URL or got sp*m filtered. I’ll have to be more vague:

Maneesh Sethi hired someone to do what you are asking for. Hopefully you can Google that to find out what he did.

Thanks, Edward, that’s awesome! On that front, I may have to check out Beeminder. (IIRC, Robin Hanson used it to bet himself that his number of uninterrupted 15 minute work sessions per day would increase over time – I can’t remember how that work out.)

Stop reading long comment threads.

I think I’m about to put a bunch of websites, including this one, on a network-level blacklist for certain time periods each day. My job has exciting parts and boring parts, each equally important, but being on blogs is more inviting than the boring parts!

Scott, I think the huge difference there is that on the one hand, university students (including Stanford which, I am given to understand, is not a complete dump unlike Oxford) and on the other hand disadvantaged children. Getting into university means a certain level of stability in life and committed parenting, not to mention financial ability to pay for it. Children who don’t know from one day to the other if they’re going to get breakfast in the morning are somewhat more of a problem to overcome.

I’m tempted to say that people who make and stick to plans are more likely to be the kind who would get better grades anyway, and giving them time management tools merely is the icing on the cake, as it were – people too disorganised/unmotivated to bother participating in learning time management are not going to stick to the goals and routines anyhow, even if they do learn them (I say this from my vast experience of procrastination and only being motivated to complete projects by last-minute shrieking terror of ‘the deadline is tomorrow!’.

That was my thought as well. Could it be that interventions work pretty well, just not on the people that need them the most?

At which point, politically speaking,

“Hey, if I invest a grand into making people who are going to do well in life do EVEN BETTER, it’s a fantastic investment that pays for itself a dozen times over”

is a bit hard to do.

It might be a good idea, but we’re already having enough problems with pre-tax inequality.

Capitalism isn’t that ruthlessly profit-focused.

It’s ruthlessly self-image-of-capitalists focused.

I’ve often argued that status is the forgotten variable in an economic system, but even so, the most solipsistic capitalist usually pulls his head out of his ass before he goes bankrupt. Usually. Unless he can get the government to bail him out.

Well, going bankrupt means a serious loss of status.

Some chancers seem to use serial bankruptcy as a means of setting up companies, milking them for as much as they can get out of them, then declaring bankruptcy and leaving their creditors looking like lemons while they set up new companies under other names (because yay, can discharge your bankruptcy and start afresh!)

Or we have Irish or formerly-Irish people who went big into property development in the boom times, have now gone bust, and have departed to America or England to declare bankruptcy in an attempt to declare that they don’t owe anyone anything (or at least, have no assets worth seizing to pay off those debts). Lack of status does not seem to be distressing them any.

Bankrupt -> Low Status only really works when you’re part of a community. Davos Man doesn’t care what the ordinary Irish think of him. They’re hardly people. He also doesn’t care what the citizens of any other country think of him.

> An economist and a normal person are walking down the street together. The normal person says “Hey, look, there’s a $20 bill on the sidewalk!” The economist replies by saying “That’s impossible- if it were really a $20 bill, it would have been picked up by now.”

My problem with “if it worked we’d already be using it” is that it ignores how doggedly people can cling to bad approaches that work just about well enough to not be thrown out immediately.

My favored example is an experiment where various interventions were tested in schools to try to improve performance. We’ve all known families where the parents attempt try direct cash/material rewards along the lines of “We’ll get you a car if you get all A’s” or similar. It tends to be richer families that do this and their children don’t tend to do badly.

So an experiment was done trying the same thing en-mass. Turns out that exact form of intervention is very ineffective. (big reward for final marks) but some of the variations they tried were massively successful.

The most effective was simply paying children 2 dollars per book they read while also being the cheapest intervention.

Their conclusions were that paying small amounts for things that children can do themselves immediately that improve performance long term is very effective while rewarding long term outcomes is ineffective.

http://scholar.harvard.edu/files/fryer/files/092011_incentives_fryer_allen_paper2.pdf

Yet how often do you see students being paid to read books. You’d expect it to be implemented in every school since it’s cheap an effective.

But people are insanely conservative about these things. the guy running the experiment got death threats because people believed it was wrong to even consider such things.

“If it worked we’d already be using it” is a bad form of argument because there’s more involved than the simple question of whether an intervention would work.

If we count stickers and pizza as payment, pretty routinely.

The $20 bill joke is funny, but it also carries a valid lesson. Real economics doesn’t suggest there are no $20 bills to be found, just that the ability to profit from finding them gets competed down over time. A more accurate but less funny version of the joke would be:

In ten cities, a non-economist is walking with an economist friend and says “Hey, there’s $20 on the street. And I also found $20 yesterday on a different street! I’m going to quit my job, withdraw some savings, hire some employees, and start a business finding money on the street.” The economists say: “If there was enough loose money to support a business, it probably wouldn’t pay better than the job you have now, because other people would look for money until the value dropped below their other options as well. And even if you make a temporary gain over your other options, once people realize what you’re doing, they’ll join in too. On top of that, there’s a good chance you’re wrong in your estimate of how much money there is, and if your job includes any special skills, you’re likely to lose as the rate of return for money-searching drops to, at most, that of unskilled labor.” The ten friends try it. 7 lose their shirts, 2 make a living at the unskilled wage, and 1 reaps an early windfall for a few weeks, then sees his returns drop to that of unskilled labor.

(If you want the joke to be even more realistic and even less funny, you could have the first character quit his or her job to take up walking on the beach with a metal detector – economics doesn’t predict that there is no lost jewelry on the beach, but only that there isn’t enough to reliably quit your job and start finding it, and than on average, people who do so will not see their income increase.)

It’s hard to believe that if dowsing worked reliably, somebody wouldn’t be making a killing on it. You could become fantastically rich in a few years. Similarly, if you could reliably curse people, I’d expect someone somewhere in the world to try it, and once it started working, I’d expect it to be adopted generally. It might take a while, but most of these ideas have supposedly been practiced for thousands of years. (Moldbug had the inverse point about witch hunts – if the people accused actually could perform reliable witchcraft, you’d expect them to put up a better fight.)

It’s hard to believe that if dowsing worked reliably, somebody wouldn’t be making a killing on it. You could become fantastically rich in a few years.

But do geologists who work for oil companies finding oil and gas become fantastically rich in a few years? I suppose, if you’re the most accurate geologist in the field, it would be worth your while to quit the job and found your own exploration and drilling company, since you know and can prove to investors that you find good deposits 90 times out of a 100 while the closest competitor only manages to do it 75 times out of a 100.

But most geologists, I imagine, stick to the day job with the company and keep going till retirement. I don’t see why dowsers in general would be much different?

If dowsers were about as accurate as geologists, but significantly quicker, a dowser could make a lot of money. They wouldn’t have any dowsing competition, and therefore would have a huge advantage over everyone else until other people caught on and started dowsing. In that time, they could make a lot of money, and then dowsing would become standard.

The big advantage of effective dowsing isn’t necessarilty accuracy but reduced search costs, which would let you find oil that other people didn’t know about.

If I could find oil by walking the land without taking or analyzing samples, (or better yet by moving my stick or plumb bob over a map!) I would look for a way to get in front of oil companies. Ideally, you could just buy options on drilling rights, but you might have to own an exploration company to make that work.

Being a geologist for a petroleum company pays pretty well – better than the jobs that most people who claim to be able to dowse currently have. If dowsing worked, at the very least, some oil company would hire dowsers at salaries similar to those of petroleum geologists.

Except: most oil is deep, and even if dowsing were real, it might not be effective at the depths oil is typically found at. I’ve worked with exploration drillers (small-scale stuff, for property development) who believed in dowsing, and used it to “find” utility lines. Personally, I think they were just subconsciously integrating the various clues that utility lines leave at the surface, because they did spend a bunch of time looking all around before doing their thing.

We had a program in elementary school that basically paid you to read books. You’d read a book, then take a short computerized test on the book, and get points based on a combination of how well you did on the test, and what the point value of the book was (based on length * grade level). Then you could trade in your points for prizes at the end of the month.

The bad thing about programs like that, in terms of cost-effectiveness at least, is that it ends up investing a lot more money where it isn’t needed, as the kids who are already good readers and would read a book or two a day anyway will end up using it a lot more than remedial readers who don’t like to read in the first place.

>Then you could trade in your points for prizes at the end of the month.

so the reward was delayed significantly: exactly the wrong way to do that.

paying kids to read is insanely cheap compared to the other costs in education and had a dramatic effect in the experiment. You want to help and and all of the kids, not just the ones doing worst.

You got the points immediately, which, for 3rd grade me, was just as good. Just like getting points in a video game. I don’t really see much difference between getting points that are only spendable when the ‘store’ is open and cash that’s only spendable when stores are open.

And today you’re posting on a blog where the minimum commenter IQ is 115. Educational policymakers aren’t worried about coming up with programs that work for you.

Considering that my local library more or less bribed me with “Kid, to stop you coming in every day to return the book you took out yesterday and read last night and now you want to take out another book which you will then return tomorrow, how about we let you have the adult allowance of three books at a time plus we turn a blind eye if you borrow from the adult section, but in turn you only come in once a week?”, if there had been a “pay you to read” scheme in my youth, I would have been rich, rich, I tell you! 🙂

One book at a time for kids, and only three for adults? My condolences.

To be serious, I feel like the success of “pay kids to read” would depend on what would be count. If you get the same cash for a 5-page picture book as you do for a 300-page novel, that discourages the reading of long books. If you weight cash by length of book, it would still encourage easy-but-long books over more challenging, shorter books. It’s probably too complicated to give each book its own weight, as well. Furthermore, would it be implemented by schools, libraries, or some outside party? If so, would books from other sources than the one paying (e. g. library books, if a school does it) count?

Of course, all of that just means that paying for reading might not be perfectly optimal. That doesn’t mean it’s not better than the current state of affairs.

Nope, this is a solved problem. There are systems that weight points on length+grade level of reading. In highschool I made a game of finding single books that would knock out the entire quarter’s reading requirements.

Oh, okay, cool. On one hand, if those systems are that easy to game, then they’re probably not optimal. On the other hand, if you’ve found a book that’s long enough and advanced enough for an entire quarter, it’s probably fine.

In this context, “game the system” means “read Crime & Punishment.” Boy, I sure showed them?

Irrelevant: out of curiousity, do you remember any of the books that met the knock out requirements?

In highschool I made a game of finding single books that would knock out the entire quarter’s reading requirements.

When I was nine, I was reading this.

Would that have counted? 🙂

(By the bye, when I was nine, I was absolutely disgusted that Caroline took to her bed in a decline because she was pining for Robert Moore. No man was worth that!)

@Irrelevant: Yeah, that was my second point. If you’ve got a book long and advanced enough for an entire quarter’s worth, it’s probably fine.

When I was little, our Saturday morning routine with mum consisted of going to the supermarket and then to the library. It got to the point that when we approached the check out counter with our box of books for the week the librarians automatically opened up a new line.

Being limited to 7 books a week was tough enough when we went on holiday. Being limited to only 3 books a week would have been torture.

Yeah, the three book limit meant I went by the principle “the thicker, the better”. A doorstopper might or might not be well-written, but it would at least last 🙂

I agree that we should be running a lot more incentive trials, but Fryer’s coauthor on the Houston study offers some words of caution.

http://theconversation.com/why-cash-incentives-arent-a-good-idea-in-education-32494

Sigh. The teach to the test canard. Imagine a world where a test actually tested for valuable knowledge. Say….reading comprehension, or the ability to write an effective argument, or the ability to solve an analytical problem from a text description, or a test that measures distinct forms of innate intelligence. Imagine a world where these skills are valued.

The imaginings of many that these tests only look for rote memorization skills is false. Geography and history can involve a lot of rote memorization and these are rarely subjects of mandated standardized testing.

We’re not really talking about teach to the test, although Holden mentions it, it’s not relevant to Fryer’s article. (Holden’s not directly responding to Fryer, so it’s not surprising that his article contains other stuff).

Fryer’s article (in Murphy’s original post on this topic) argues that outcomes based incentives don’t show much benefit in studies, so Fryer recommends against paying for test scores (“outputs”) and for paying for schoolwork, like math problems performed (“inputs”). One of the studies Fryer uses to argue for that recommendation is a Houston study that he and Holden did.

In the Holden article I linked, Holden recommends against incentives altogether. Holden says that although his and Fryer’s study showed measurable and lasting gains in math performance when they paid for math problems performed, those gains came at a cost of equivalent losses in reading performance – i.e., that students were presumably shifting study resources on a zero sum basis).

Now, it’s possible that correctly aligned input incentives might produce overall gains, so I think we should do a lot more work on incentives, but Holden doesn’t think that he and Fryer have shown that yet.

The fact is that the ratio of simple solutions working to those that actually claim to work is near zero. I don’t think anyone is claiming it is equal to zero.

Someone probably thought that if we designed a simple page layout language on an interconnected network it would radically change the world…and was dismissed.

Someone probably thought that loaning money en masse to those with bad credit histories would lead to large scale problems in the real estate and financial markets…and was dismissed. That person bet his own money on it and made billions (the story is in the The Big Short).

It happens. Rarely.

This is different because the network (at least at a quality good enough to make the idea work) was new. Simple solutions that take place in new contexts can indeed exist–the objection “if it worked, someone would have done it already” doesn’t apply if it’s new.

“If this new technology worked we’d already be using it. which we aren’t,. so it doesn’t work. so let’s not start using it.”

In all seriousness though I share some of ypur weariness regarding social psychology research. But aren’t you going a bit far? For instance I personally have had worse time management skills than I have now. When I got more clever about how I spent my time school got easier, or at least less stressful. That teaching this explicitly would work seems pretty likely, though maybe it’s limited to sort of ambitious middle-class+ groups?

I think the criticism is the endless parade of “simple fix X discovered for endemic problem Y that has plagued society for Z years” that gets trotted out so regularly that everyone now ignores these pronouncements entirely.

I feel sorry for the poor soul who actually finds something that works like this someday and is completely ignored.

>3. Oaten and Chang helped undergraduates set up an 8-week time management program involving schedules and diaries. The students who participated not only had better time-management, they also studied more, smoked less, drank less alcohol, exercised more, ate a better diet, spent less money, rated their emotions as better, missed fewer appointments, and were less likely to leave dishes in the sink (really!).

I absolutely need this, both the time management and the rest, please throw time management resources at me, preferably the ones used in the experiment!

Also, on glucose, yesterday I managed to fight off alcohol cravings (day 5) with a donut, and this is news to me because normally I dislike sweet stuff and desserts and snacks (I drunk instead).

Do you think the glucose drop after a carby lunch is worse than no lunch at all? As I am thinking eating a healthy breakfast and skipping lunch because healthy lunches are harder to come by (i.e. it is usually sandwiches) and so on. How glucose is supposed to look like after about 10-12 hours fasting, 6:30 breakfast to 17-19h in the evening?

Or, getting a bag of almonds in the grocery store for lunchy snack is also an option.

I’d say try and avoid the doughnuts, go for the almonds (nuts are supposed to be the divil an’ all for good blood glucose) and that probably the sugary, carby goodness of the doughnut helped fight off the desire for alcohol by replacing the calories.

Don’t skip lunch altogether as you’ll end up absolutely starving in the evening and end up stuffing your face, and apparently eating a large meal at night is more fattening than eating the same amount in the morning. So stick to the salad sandwiches and good luck! 🙂

Fasting blood sugar (glucose) levels for diagnosing diabetes from this site:

Is talking about correlations a good way to undermine an intervention study? An explanation for the inverse correlations could be that highly intelligent people are more likely to develop fixed mindset in early life.

Every time I read about sample sizes in medicine or psychology it just makes me laugh.

1000 data points is a lot? Really?

I once spent some time reverse engineering a micro controller program. We didn’t have any way to dump its rom so it was all black-box testing. It took me about six months to get the complete solution, and after a while a pattern emerged: more data = more progress. I went though many cycles of fruitlessly analyzing the data I already had, getting frustrated, giving up on that to work on building better software (and hardware) to collect better data, making quick progress once I saw that data, and then having that progress grind to a halt as it slowly dawned on me that I *still* didn’t have enough data.

Eventually I cracked it with about 50,000 extremely high resolution oscilloscope logs collected off the device. I could have solved it a lot faster with a million of those logs.

In the end the model I wrote for the device fit in a couple pages of matlab.

If it takes n=50,000 to understand a silly little micro controller, I’m skeptical that n=1000 can be enough to understand a human.

Then again those psychologists could just be a *lot* smarter than me. Once I had the model I could confirm it was true with n=10.

Unless you’re offering an ethical source of cheap human test subjects, this is just mocking people for being poor. Tut, tut.

Something like this?

http://www.wsj.com/articles/furor-erupts-over-facebook-experiment-on-users-1404085840

Might fall a little bit short on “ethical” though.

If anything it’s making fun of people for being poor and PRETENDING to be rich.

It’s easy to look at that chart, do a little substitution, and say “if evolution really worked, companies would be using it to make lots of things. Thus proving that evolution is wrong.

Even if you were smart enough to be aware of evolutionary algorithms to design circuits, it’s clear that it’s very rarely used. You could then add “well, what evolution does is such that for most applications, evolution wouldn’t happen to be very useful”, but then someone else could say that as an excuse for any of the items in the chart as well. In order to refute *that* you’d need to basically say “to know whether something is useful in a real-life endeavor, you need details that are not in the chart”, admitting that the chart is worthless by itself.

That’s got more to do with the fact that evolution is the slowest, least powerful method of solving problems.

I think you meant “most powerful”.

The prostate and urethra beg to differ.

Agriculture. Selective Breeding.

There you use evolution in a context where you’re stuck with it. I bet most agricultural scientists would prefer just designing a supercow than laboriously pulling the levers needed to breed one.

Jiro has a point. I encourage everyone, but especially fans of evo-psych, to try to solve some nontrivial optimization problem with a genetic algorithm of their own design. You’ll quickly see how slow or downright obstinate evolution is at delivering the results that selective pressures should “clearly” guide it to.

And viewed from the other side: Bacteria. Antibiotic resistance.

We know that works, and we certainly aren’t *trying* to encourage it!

That’s not plain evolution, that’s intelligent design they’re using! Checkmate, atheists!

I agree that the chart should be improved if used as a serious argument.

However, I think you’re mischaracterizing the implied argument – presumably the question for, e.g. dowsing is not “is there some conceivable way dowsing could technically be a real thing”, but rather “should I pay some guy $500 to dowse for a well”. That is, the chart suggests the phenomena are not exploitable, not that they don’t exist. Maybe curses are real but notoriously unreliable and sometimes bless the target instead or rebound and kill the caster. But in that case you probably don’t want to try cursing your enemies anyway.

This holds for evolution – if you’re not trying to design in very particular fields or selectively breed produce/animals, then it’s not going to do anything for your problem.

So yes, these arguments are less compelling as your intended use diverges from the listed application (maybe you can dowse for water and not oil?), but generally the examples are pretty typical of what people want out of the phenomena.

Directed evolution is used routinely in biotechnology.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Directed_evolution

Apart from that companies are using evolutionary algorithms to do lots of things.

I am currently using a model for dispatch of power plants that uses evolutionary algorithms to calculate the usage of transmission lines.

Is there one optimization problem where evolutionary algorithms are state of the art? I don’t know of any. The best that can be said of them is that they’re sort of good at sort of many things – provided they’re the kind of EAs that look more like stochastic hill climbing, and less like actual biological evolution. Maybe they’re the best thing to use on a problem before one gets the faintest grip on what sort of problem it is.

Of the people buying software that actually use evolutionary algorithms (which is almost always custom software) , half would be better off using some sort of linear programming solver for that task, and the other half would be better off with (another sort of) machine learning model.

The reason my dispatch software uses evolutionary algorithms is even though you can come up with a DC solution using the voltage laws, for a complex power system that’s way too slow for exploring various scenarios. The evolutionary algorithm gets good-enough results a lot faster.

And hey, the DC model is inaccurate anyway, as it is really an AC system.

I don’t know how a machine learning model would work here, as one of the goals of the model is to be able to calculate what would happen in scenarios that haven’t happened yet.

That the chart relies on data not entirely recapitulated in the chart, and that the chart is useless by itself, are two very different claims.

Given all these studies seem to allow people to opt out, surely there is at least some element of bias between those who do the extra work and those who don’t? I’d assume that those who are doing extra work are more motivated or enjoy the course more than those who didn’t, and this would probably account for at least some of any increase in grades. Similarly with the third study dealing with time management skills, those who are motivated or organised tend to be the most likely to sign up for a course despite the fact they already have those skills and you would expect them to do better than people who aren’t willing to sign up for a time management course.

I want to believe that they at least had the presence of mind to create a control group by not enrolling some of the people who opted in. Surely they would at least manage to do that, right? Right?

I’m not sure I understand your complaint about the third study. You seem to be saying “oh, this time management course helped their outcomes, but only by improving their time management”. I guess you could be saying that they didn’t learn any actual time management skills from the course, it’s just that the course forced them to manage their time? But that still seems like a really important result that we should be doing a better job of forcing people to manage their time for their own good.

Said the blog commenter.

Am I reading too much into your descriptions of the studies, or is compliance bias an issue here? You’re describing them as “Students were asked to do X, and students who did X had better outcomes,” which sounds to me as though there were students who were asked to do X and didn’t do X.

The first two are RTCs. I’m not sure which paper the third is, but it’s probably an RTC. The same authors seem to have other papers that claim more improvement among people with better compliance, but that’s OK.

Random Trial Controlled?

I’m not at all convinced that “education, rehab, and mental health” are nearly as ruthlessly focussed on bottom line effectiveness as the fields mentioned in the XKCD comic.

Agreed, it seems way easier for the entities with the best profit incentives to have their employees be productive, good at time management, dedicated to doing well etc. to hire people pre-sorted for having those traits.

Or to put it more depressingly: The worse colleges are at helping their students actually learn useful skills, while still requiring them to do well, the better a signal they are for innate talent and dedication.

This

http://cdn.static-economist.com/sites/default/files/imagecache/original-size/images/print-edition/20131019_FBC916.png

>In “Crazy Phenomenon”, add “any large and persistent effect from social psychology”. In “If it worked…” add “education, rehab, and mental health”. In “Are They?”, add “not nearly as much as I would expect”.

1) something something implementation of uncontroversial social policy often requires centralized planning. Science and common sense indicate that kids would do better if schools would not start the morning so darn early, but we haven’t acted on that one. (Or, say, public transport.)

2) The three studies you mention indicate a fairly short term effect. One semester of elevated GPA during treatment, followed by a total return to baseline upon cessation, is probably easier to procure when compared to superior *life outcomes* over 10 years.

Of course, these particular studies might have flaws and I’m not making any defense of them, but setting aside questions concerning the actual studies; as a general principle there’s nothing incongruous about dramatic short term interventions being cheap, but small, long term stable gains being expensive.

Also, you can’t necessarily make a short term 6 month intervention into a long term 10 year intervention simply by extending the period, since treatment effects often diminish with time. It happens with medication all the time as tolerance builds, and it would be totally unsurprising if time-management courses gradually stop working as the novelty wears off and the motivational effects diminish.

In medical terms, you’re doing the equivalent of comparing “we significantly reduced blood pressure in hypertensives over 3 months” to “we significantly reduced cardiovascular mortality rates over a 10 year period.” and wondering why the latter seems to need more oomph. (Except for the part where you actually find flaws within these particular studies, which may be totally valid.)

Here’s an excellent recent discussion of the problems with using p values to evaluate studies, in Nature Methods. It’s not behind a paywall, and it’s very readable. Title, “The fickle P value generates irreproducible results.” Link below. They basically recommend that P values be ignored in favor of effect sizes and confidence intervals. The confidence intervals convert the hard to interpret P values and sample sizes into easily understandable range of probable outcomes if the study is reproduced.

My basic rules of thumb are, “if a study doesn’t report the effect size in the summary, the effect size is probably so small that the study should be ignored, indeed reviled and insulted for wasting out time.” and “if a study doesn’t report confidence intervals in the summary, the confidence intervals probably include zero (ie, the range of probably outcomes includes no effect), and the study (and it’s authors), deserves to be insulted and ignored.” Based, of course, on the assumption that all bad news is buried, and good news is trumpeted. This saves a great deal of time in evaluating studies.

Anyway, here’s the link to the study. It’s definitely worth your time. It includes some excellent example graphs showing how confidence intervals incorporate both a studies P value, sample size (power) and effect size, in one EASILY UNDERSTANDABLE figure.

http://www.nature.com/nmeth/journal/v12/n3/full/nmeth.3288.html#f4

I’ve started seeing effect sizes a lot more in the past five years, which is good. On the other hand, the new trend seems to be to use some very exotic effect size statistic I’ve never heard of that leaves me confused. I wish people would stick to d.

Is a 95% confidence interval for the effect size that doesn’t include 0 the same thing as a p value of < 0.05?

Yes, if the null hypothesis is an effect size of zero. For any value, we can consider the hypothesis that the effect size is that value. Being outside the confidence interval is the same as rejecting p<0.05 that hypothesis.

Any time you see someone using “advanced” statistics you should immediately ask yourself why this was necessary instead of using the standard measurements.

I’m sure there are legitimate needs for advanced processes, however when only advanced results are shown (to make a tidy argument) without also showing the standard methods and explaining why this standard method was invalid for this purpose, it should raise red flags.

Nice find, dlr. Word needs spreading.

That is one of my least favorite XKCD cartoons, because it makes a snide argument that is false on its face. There are people making a killing off of crystal energy. They’re called crystal energy healers. Dowsing has actually been used to find oil, to occasional success. Health care companies cover many kinds of homeopathy, precisely because they’re often cheaper than traditional treatments.

I do not actually believe in dowsing or anything else in his first column, so my object-level beliefs about those things aren’t much different from Munroe’s. But his meta-level argument still sucks.

(My other least favorite XKCD is this one, which fails for exactly the same reason.)

The alt-text says “Not to be confused with ‘making money selling this stuff to OTHER people who think it works’, which corporate accountants and actuaries have zero problems with.”

I had forgotten about the alt text, but I don’t think it matters. There’s no principled distinction that can be drawn between “making money using X” and “making money selling X to people who believe that it works”. All instances of the former are implicitly instances of the latter.

I don’t see how you come to that conclusion. Say, Exxon-Mobil has a dowsing rod that works. They use it to find plots of oil-rich land they can buy cheap, and start drilling. They sell the oil that comes out. They may or may not tell people that they used a dowsing rod to find it.

This does not even implicitly mean that the customers believe that dowsing rods work. Or even that they care. What matters is that they believe that oil works, and that the stuff Exxon is selling is oil.

There is a reason the distinction is meaningful. “Making money selling X to people who believe that it works” means that your market is entirely limited to people with spare money that they have discretion over, and your business models consists of harming their market performance, thus making them have less money to give to you. “Making money using X”, however, means that your market is not merely people spending their own money, but people spending money on behalf of other people. Your business model consists of making your customers richer, which means they can buy more of your services, which means that they get even richer, etc., to the point that the industry is dominated by your services.

So, take the example of Exxon-Mobil. If you have fake dowsing abilities, you might be able to talk an EM executive into giving you money, and maybe you’ll hit some oil by luck, but eventually the executive will have spent a bunch of money on you, and a bunch more money on dry wells, and at some point the company is going to get sick of this and fire the executive, and now you’re going to have to find another sucker to bleed dry. If EM doesn’t wise up, they’re going to be bleeding money, and if this becomes their dominant way of finding out, they’ll go out of business.

Now suppose you have real dowsing rods. The executive is going to develop a track record of finding oil, and is going to rise the corporate ladder, and be able to devote more and more of EM’s budget to you. Other executives will catch on and start giving you money, too. EM will start making a lot of money, and be able to pay for even more of your services. EM will be so successful that other oil companies will want to hire you. Eventually, all the oil companies will either have dowsers or be forced out of the market.

So, in one case, you’re limited to how much money the executive can get out of his budget. But in the second case, every dollar that anyone spends on oil is a dollar that you potentially could be getting a share of.

Never heard that articulated so well before! Thanks.

What if dowsing does work, just not as well as whatever it is oil companies use now? That would look the same as “doesn’t work” under the xkcd test, wouldn’t it?

Dowsing is very cheap compared to what oil companies do do now. So, as oil companies aren’t using it, dowsing must not only be not as good as the current techniques, but must be an awful lot worse.

Which does undermine anyone who is claiming that dowsing is great.

That’s a good point; I hadn’t considered the cost side. Being near-zero cost, if dowsing were decently effective you’d at least expect some sort of first-pass dowsing sweep before they bring out the fancy technology.

But have we any cases where oil companies used dowsers as well as, or instead of, conventional geological methods? It’s easy to say “if dowsing worked, oil companies would use it”, but if they’ve never tried it at all, how can you say it would or wouldn’t work?

I mean, you can say “I don’t need to try it, I know it’s nonsense” and that’s probably why oil companies don’t try it (imagine being an executive who raises “Hey, why don’t we skip the field analysis and get a dowser in?”) but it doesn’t prove anything one way or the other.

This guy says he’s a professional dowser working for oil companies! He may indeed be a con artist, but who knows? 🙂

Yes they have. There is (or at least, before the recent collapse in oil prices) a lot of small oil companies that can try all sorts of ideas, it’s not all BP and Exxon-Mobile. And a lot of oil is in Texas, which is not a place noted for its strict dedication to sobriety, science and conventional behaviour.

@Jaskologist

“What if dowsing does work, just not as well as whatever it is oil companies use now? That would look the same as “doesn’t work” under the xkcd test, wouldn’t it?”

What would it mean for something to “work”, but to not do better than what oil companies? If by “work”, you mean “do better than picking a random point”, well, picking a random point in Texas is better than picking a random point in the United States. So does pick-a-random-point-in-Texas “work”? If someone spends a hundred hours getting basic knowledge of geology, then spends another ten hours studying the geology of a particular area, then goes out with a dowsing rod and does better than chance, does that show that dowsing “works”?

EM will be so successful that other oil companies will want to hire you. Eventually, all the oil companies will either have dowsers or be forced out of the market.

More likely, EM would have the dowser under a Non-Disclosure Agreement, so as to stay ahead of the other oil companies.

Anyway, to be fair, XKCD should be looking at purposes for which dowsing is admittedly used: shallow wells or pipe locations, etc.

People who hardly ever heard about relativity still use GPS. For all they care it may be a ghost in the box. All that matters is it gets them where they want to be. They believe in “this box gets me there” and this belief is very easily verified or falsified, they do NOT need to believe “relativity is true and it gets me there”.

I actually think this is the best response. “Works in the absence of the consumer’s awareness” is a decent test that allows us to exclude most placebos.

GPS doesn’t work because of relativity. GPS needs to have small corrections made in its calculations that were predicted by relativity (the measurement of time is different for objects that are at different relative velocities, and GPS satellites are moving quite fast compared to a location on earth).

GPS works by triangulation using satellites at different orbital positions in a similar way a cell phone is triangulated using different cell towers.

Shenpen and Tom Scharf – the people who *make* GPS units have to use relativity to make the units perform correctly. A GPS unit made by people who didn’t believe in relativity would be not nearly as useful, and the maker would have a hard time selling the product faced with competition from suppliers who did believe in relativity, and used it in the internal calculations.

Anthony,

If relativity was yet to be discovered, GPS would still be made to work. The error of GPS’s day length measurement being faster by about 39 usec per day is a constant and is compensated for by altering the clock frequency slightly. It is unnecessary to understand why the compensation has to be made in order to make the system work properly. It’s good to know why.

There are lots of errors with GPS that require compensation.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Error_analysis_for_the_Global_Positioning_System

Could you elaborate on how the other one fails on the meta level? I could see how the first one fails (especially since some theories of the free market can consider it ruthlessly profit-focused and still likely to miss ideas that happen to look crazy on the surface, since it doesn’t require anyone to be a good decision-maker), but short of Dresden-Files-esque fields that make electronics stop working around magical things, “Conclusively settled” seems like a mild overstatement at most.

To make your and Munroe’s argument explicit, the claim is that the ubiquity of cell phones means we should have abundant videos of ufos, ghosts, and cryptofauna, and the lack of such videos proves that they don’t exist. However, try going to YouTube and searching for “cell phone ufo” to see if you can spot the flaw in this argument.

My least favorite xkcd, which combines his usual shallow condescension with some sort of valkyrie from nowhere.

I like the comic in general, but if we’re having a whine-off, here’s the worst xkcd.

On the other hand, this is the best one ever, for unintended reasons.

My least favorite xkcd, for reasons that should be obvious to readers of SSC: http://xkcd.com/1357/

It’s not obvious to me (but I’m new here).

There has been a lot of discussion here on the destructive power of online shaming campaigns, especially when they target someone’s employment. Randal Munroe glibly dismisses this as irrelevant.

It also has a somewhat fetishist focus on the First Amendment and Constitutional Right of Free Speech, as if one couldn’t criticize thought policing apart from legal considerations.

It also presupposes that boycotts, bannings, etc. will only be used by the Right-Thinking against the Evil Bigots in plainly black and white cases of I’m Right, You’re An Evil Racist Sexist Homophobic Climate Denialist Bigot (I may have left some other the weight of history is against you causes out, please feel free to add in your own).

But it’s not all Nazis versus the rest of us when it comes to free speech, and it can lead to ‘what you are doing is censorship; what I am doing is refusing a forum to hate speech’ attitudes.

The argument isn’t that stuff that doesn’t work can’t support small-scale economic activity, or randomly appear to work occasionally. The argument is that that they don’t outperform chance reliably enough to support concerted business applications. In short, they don’t scale.

I’ve met quite a bunch of crystal healer type people, and none of them, not one, relied on their “work” as a sole source of income. The “stars” of their fields write and sell books, or teach courses, meaning they mostly live off pyramid schemes, not off putting their beliefs to the practical test.

“The argument is that that they don’t outperform chance reliably enough to support concerted business applications. In short, they don’t scale.”

Exactly. The first army that harnessed magic would be nigh-unstoppable. Never mind tossing fireballs at the enemy. Using magic just to produce potable water and edible food would have had a massive advantage over enemies drinking from streams fouled by their own waste and trying to seize edible food from the local peasants. It’ll be a long siege if the city can produce abundant food and water at will.

You are equivocating in the use of “long-term.” The big study was about the effects 10 years after the intervention ended, while the small studies are about the effects of the intervention only 1 year after the intervention ended. I think that the big study had a big effect 1 year into the intervention and also 1 year after intervention ended. And there are lots of studies of intense interventions that last 1 year and have a big effect 1 year past that. So I don’t think that the small studies claim to be strictly better than the large study, only dramatically more cost-effective.

Here’s a draft paper reporting on a big multiple laboratory replication study. They found that seven out of ten previously published findings in psychology did not replicate: huge effects found in original studies were not reliably different from zero, and even those that did replicate tended to be smaller. See page 19 for a summary graph.

It’s not just psych. under-powered studies are a problem across the board.

http://www.nature.com/nrn/journal/v14/n5/full/nrn3475.html

>Implications for the likelihood that a research finding reflects a true effect. Our results indicate that the average statistical power of studies in the field of neuroscience is probably no more than between ~8% and ~31%, on the basis of evidence from diverse subfields within neuro-science. If the low average power we observed across these studies is typical of the neuroscience literature as a whole, this has profound implications for the field. A major implication is that the likelihood that any nominally significant finding actually reflects a true effect is small. As explained above, the probability that a research finding reflects a true effect (PPV) decreases as statistical power decreases for any given pre-study odds (R) and a fixed type I error level.

This specific XKCD if anyone’s wondering:

http://xkcd.com/808/

Most people using xkcd comics forget to write out the tool-tip/hover-message-thingy, which really is about 60% of the fun (take note, writers!).

So thanks for digging that up.

If education were learning-focused (let alone ruthlessly learning-focused), then I’d have heard about Anki, which has all manner of support, in school and not when I was failing all my classes trying to figure out how to actually learn stuff. (Turns out, in terms of learning, dropping out of school was one of the better choices I’ve made—except for the resulting 9-month period of depression, during which nothing got done. But now that’s over, I can self-study 1.5x the courseload at 2x the pace in a few hours a day, and I can scale the time if I’m under a time constraint.)

That is, each of these interventions could be just as impactful as these studies suggest and colleges would never implement them because, whatever they are optimizing for, it’s certainly not learning outcomes.

There are at least *some* colleges that are trying to optimize for learning outcomes. But feedback loops are slow, and colleges take a long time to fail even if they’re doing badly. The free market works mostly be weeding out the really bad strategies, and colleges are very hard to weed.

Baddeley and Longman (1978) demonstrated that practicing one hour a day is about twice as time-efficient as four hours a day (broken into 2 2-hour chunks). This result has been replicated enough that it has its own Wikipedia article and has been around for >35 years. I’ve attended 5 universities, from community college to Ivy League, and not once have I had a chance to take a course that was broken into shorter periods for 5 days a week, let alone 7.

Ebbinghaus did his work on forgetting curves in 1885. This, too, is sufficiently well-replicated to get their own Wikipedia article. Why does every college I’m aware of maintain several month+-long breaks plus several week-long breaks? (h/t to Sal Khan for this observation).

This stuff really, really isn’t hard. It is not controversial (Wikipedia articles!). It is not new (1978! 1885!). And it’s about as hard to implement as “get rid of the snitch” (or whatever).

To be fair, every professor I’ve talked to is doing their best to maximize student learning, but through some combination of incompetence (math professors, unsurprisingly, don’t read very much cog psy literature), yielding to constraints of “this is what you have to do to keep your job” (which they are blameless for yielding to), and dealing with students who have minimal interest in learning, college classes look almost identical to “we haven’t optimized this for learning at all!”

The education profession as a whole basically acts as if cog psych didn’t exist. It’s why we have things like constructivism.

I’m a bit puzzled as to what US universities look like. At my NZ university, most courses met for about one hour for lectures twice a week and once a week for a tutorial, with longer lab sessions. And at my high school, lessons lasted 50 minutes and we got four lessons per subject per week.

The obvious problem with breaking up courses even more frequently is the transition time between classes. And labs take more set-up and break-down time thus the call for longer periods of time there. It’s not like walking into a typing class and sitting down at an existing typewriter.

As for month+ breaks, pre-air-conditioning and pre-sewage systems, there were obvious reasons to flee large population centres during summer if you could afford to. It’s not like people would have been learning much anyway. Now it’s the time students earn their money.

And while students may learn better with practice distributed during time, original researchers often want long periods of time to intensively work on something (think of Newton spending his time at home during plague in Cambridge to work out most of physics.) There’s a conflict there. Also, if you’ve been working for months on a particular line, it’s nice to have a change.

So, just because something works in lab or study doesn’t mean it’s going to get applied in the real world where there are all sorts of other constraints and costs.

If you’re going to insist on learning via convening classes, then there’s certainly a cost to breaking two 1-hour classes into 5 24-minute (or 7 20-minute) classes. However, once you realize that convening classes prevents you from doing most things the research one level down is telling you to do, you throw out the idea of classes, and have students study at their own pace each day for 24 or 20 minutes or whatever; this also deals with the “pacing problem” found in lectures, wherein the pace at which the professor lectures is either going to be too fast or too slow for virtually every student. Sal Khan has already implemented a version of this in the real world with pretty spectacular results. And he doesn’t even leverage the full bulk of the cog psy literature!

Given the increase in income (but not value) granted by a diploma, it should be cheaper for college students to take a loan and not make money over the summer. The research/internship thing is valuable, but (again, h/t to Sal Khan) it makes more sense to not have large amounts of infrastructure lay fallow for many months a year, but rather allow students to take time off whenever to do research/internships. According to Khan, a system like this has already been implemented with great success.

If want to train “long periods of work” with distributed practice, it’s really easy to pick up two related-but-distinct textbooks (Munkres and Rudin, say) and do 5–10 minutes of one, then 5–10 minutes of the other, then 5–10 minutes of the first… until you’ve been at it for 4 or 14 hours. To my knowledge, Sal Khan hasn’t tried anything like this to great success, but Roediger and McDaniel have. They call it interleaving, and suggest hospitals, which often do one-day training courses, implement practices like that.

tl;dr: it has been demonstrated that it’s possible for tertiary education to implement major improvements to learning that are obvious to anyone who’s read the relevant cognitive psychological literature. They still haven’t.

Tracy W – American universities do indeed work like that. American high schools *mostly* have 5 to 7 classes of 45 – 50 minutes each, meeting 5 days a week. Some high schools use the “block system” where they have either three 90 – 100 minute classes a day which last half the school year (as my high school did), or meet for about 100 minutes two or three times a week for the whole year.

Distributed Practice: In my experience, very few of my college classes were centered around anything that could be considered ‘practice’. Most of my humanities/social science classes were centered around lecture and/or discussion, and most of my math and computer science classes essentially taught a new topic every class. All the professors seemed to operate under the assumption that most of the ‘practice’ would be done at home. The one exception to this that I noticed was foreign language classes, in which there was a lot of in-class practice. These classes also tended to be held more frequently than others (although only 4x/week at max), which seems to be in accordance with your suggestion.

Forgetting Curves: I am largely in agreement with you here, but there are several reasons to have long breaks despite their drawbacks. A long summer break makes it easier for students to get jobs or internships. If a student doesn’t want to do either of those things, most schools do offer summer classes. Furthermore, for students who travel a significant distance to attend college, having two long breaks every year is much more convenient and economical than having a bunch of short breaks.

But we don’t go to schools to learn, at least not tertiary schools. We go for a piece of paper that makes you employable.

I thankfully forgot 90% of the business school bullshit, despite that I work exactly in that field. And things I am actually interested in as opposed to things that pay bills I can learn online or from Amazon books better.

a good idea would be to use SAT and other cognitive tests to replace costly diplomas, to signal competence. But then you end of with disparate impact lawsuits that only the biggest of companies can fight off.

I doubt anyone is going to sue you if you disregard diplomas and only hire based on SAT. On the off chance that it would be illegal, go to a country where it’s legal, set up shop and do it. You’ll make a killing in no time and force everyone to follow you in order to compete.

Or maybe your theory will stay without a check on the right in Randall Munroe’s chart. As it is today. If you have any better explanations of why not more people put their money where their “g”-loaded mouths are, speculate on.

A lot of companies outside the US *do* use IQ tests in hiring (at least two I’ve interviewed with, for example), though in both cases the test was not the *only* thing considered.

Yeah, exactly. GE’s fear of getting sued for it is unwarranted. And lots of people use them, or even dumber tests, in the US too I believe. (A company I used to work for used Scientology tests for a while. Not in my time, luckily.)

But these tests, if they provide anything worthwhile at all, do not provide nearly the value that the wasteful signaling of those expensive diplomas do. Those signals are pretty universally used for a reason. As per the xkcd, if they weren’t useful, someone would get rich on throwing them out.

@Harald K: At the very least those diplomas signal “I’m willing to put up with the most useless crap you can imagine, for years on end, if you just dangle a carrot in front of me.”.

Although they might also signal “I’m willing to put hundreds of hours into learning stuff, to make others happy, even if I’m not sure it does me any good in the long term”, which is probably just a less cynical way of saying the above, I guess.

Anyway, if I as an employer* see that you went to business school for 4 years, I will know -skills aside- that you are able and willing to put obscene amounts of time and effort into my corporation.

*I’m not an employer, though, so it’s only fantasy-talk.

Things like the Leaving Certificate, diplomas, degrees, etc. are often used as filtration by HR departments.

The economy is booming, employment is at nearly full limits, you need new workers? You’ll hire someone who can walk upright and tell their left hand from their right.

The economy is slumping, you have a hundred applicants for every vacancy, or the field is so over-supplied with the qualified you can pick and choose? Then you’ll require a minimum of “Must have three-year degree” even to look at a job application.

In case of lawsuit for GE using IQ tests:

1. The onus would be on GE to prove the business necessity of using the IQ test. The other side would bring out all their experts with sociology degrees.

2. GE would face headlines about being discriminatory against certain people

3. Congress would call GE management before it to demand they explain themselves

Even if GE won, it’s entirely a loss for them. Instead it seems much easier to just hire the duller employees and try to stop them from ruining the better employees’ work.

@Deiseach, an amusing anecdote:

I was on a hiring committee once where we had well over 1500 applicants for one position. The HR manager dumped about half the resumes with the following rationale:

Those people have bad luck and we don’t want to hire unlucky people.

Probably not the most accurate filter, but definitely efficient.

Google i don’t hire unlucky people and you’ll see that’s a common joke. If you personally saw it, I guess someone just took it to heart.

I absolutely positively guarantee you that if you tried to implement such a hiring protocol in the US you would be sued by private individuals and investigated (and sanctioned) by multiple government agencies.

Edward, it’s a moot point, because as I said it’s perfectly legal to discriminate on college admission scores in most countries, and if everything is more or less g-loaded anyway, it shouldn’t be so hard to cobble together an IQ test in disguise.

It’s not legal harassment of the poor IQ advocates which keeps us from abolishing wasteful signalling through degrees. I just don’t buy it. I’m sure Google, Microsoft etc. could have lobbied to overturn whatever precedent Griggs v Duke set in a heartbeat, if they thought it was worth it.

But Godzillarissa is right about all the non-ability related things a diploma signifies. And there are more. One huge one is health, in particular mental health. In my experience, if you have all the markers for “smart” but are a school dropout, you’re probably not entirely all right. Employees sadly (but understandably) are wary of that.

Another one is status and networks. The exact same business model, and the exact same entrepreneur skills and IQ scores, would still draw vastly different amounts of venture funding (and vastly different levels of positive media coverage, etc.) depending on whether they’re based in Silicon Valley or Sao Paulo.

@Deiseach – that suggests a really nasty feedback loop: booming business -> hire anyone with a pulse -> useless deadweight employees drive company into ground -> recession -> company gets lean and mean -> only very best get jobs -> great employees bring company out of doldrums -> rinse, repeat.

I don’t really think that’s exactly how it works, but that’s going to be a tough thought to get out of my cynic-brain now.

Microsoft and Google don’t need to overturn Griggs. They can have disparate impact if the employer can show how they are required for business function. There are certainly lots of people who are angry about the racial and gender makeup of Silicon Valley companies, but they haven’t tried using Griggs because they know it’s a losing battle.

A large general-purpose employer like GE or Duke Power doesn’t have that same luxury.

Bryan Caplan has written a great deal about “why hasn’t the college degree requirement gone away yet?” that one can Google. A big reason is that it costs nothing to the employer to demand the college degree; any savings would go to the employee. Maybe they could hire the really smart people who skipped college and saved the time + tuition costs of college at a discount, you say? But how do they signal that? They could offer to hire 18- and 19-year-olds out of high school, but there’s still substantial maturing that happens over the next several years.

There are some feedbacks, but they generally aren’t in the appropriate place to really work.

I’m sure Google, Microsoft etc. could have lobbied to overturn whatever precedent Griggs v Duke set in a heartbeat, if they thought it was worth it.

I can see the headline now: “Microsoft’s lobbying reveals corporate racism.” Sounds like a real smart business move.

“There are certainly lots of people who are angry about the racial and gender makeup of Silicon Valley companies”

All these “angry” people need to do is look at the racial and gender makeup of those who graduate with tech degrees.

Or they can choose not to look. and this is what they invariably will choose to do.

They would then need to be “angry” at the educational system for it’s clearly measured statistical racism in preventing diversity in those who graduate with tech degrees.

But that is not the politically correct target, so we shall avert our eyes.

@ Edward Scizorhands:

“If you are a high school dropout, you’re probably not entirely all right.”

Interestingly, this wasn’t the case 100 years ago, when it was common for right, stable teenagers to drop out of school to get a job in order to (literally) put bread on the table.

Nowadays, (happily) hardly any families in first-world countries are so desperately poor that they would encourage a studious kid to go to work and (less happpily) due to credentialism, a kid who does so has little chance of getting a good job, or eventually moving up in the world.

Julie K, it wasn’t Edward who wrote that, it was me. And I was only talking about apparently “smart” people. Question is, “if you’re so smart, graduating should be easy for you, so why didn’t you?”

The answer may be nonconformism, motivation issues, mental health or physical health, but whatever it is, it’s probably something employers reasonably worry about.

@Harald

FWIW, I have seen a few companines ask for SAT scores in job applications.

In the 80s, Microsoft did have a reputation for hiring people right out of high school.

Google and Microsoft do hire lots of people without college degrees: interns. The big mystery to me is why they tell them: you’re great, come back in a year and we’ll hire you. Why don’t they ask them to drop out of college and start work immediately? Sure, they’re probably learning something in that last year of school that the employer isn’t paying for, but that’s probably small compared to risk that someone else will hire them and the discount rate.

In fact, my impression is that there is a class of interns that would be offered a full-time job if they asked for it, but the company thinks it’s too weird to tempt people to drop out of college. (For grad school interns, dropping out pisses off the advisor, so Google has a policy of not making full-time offers to interns, but there is no individual that matters in the undergrad case.)

@Tom Scharf:

What are you talking about? People complain about the race/gender makeup of computer science (and other STEM) classes all the time.

Dropping out of college to take a Google or Microsoft job offer is bad because dropping out makes it much harder to get a job in case the Google or Microsoft one fails. So an offer which has to be taken immediately is much less attractive than an offer that says “finish college first, and then we’ll hire you”.

Nornagest,

I am speaking to root cause analysis. Silicon valley corporations are not what is causing the diversity problem. Those who believe this are being willfully blind.

Origins of success in STEM is certainly worth debate. One can go back further and examine aptitude tests entering college and also find a disparity. Women drop out of STEM at a disproportionately high rate for reasons other than ability.

FWIW I think you’re basically right, but “willfully blind” is overselling it. Most of the people that care about diversity problems don’t care about root cause analysis; nor do they really understand or care about the internals of STEM industry. They just want the gap in the statistics to go away, or at least to be seen to be doing something about that gap. Silicon Valley has money, isn’t too popular, and is probably the most publicly visible step in the causal chain, so it’s an obvious target to lean on.

Is that just? Effective? No, but if you think this is about either one, you haven’t been paying attention.

Assuming you’re objecting more to “willfully” than to “blind”: it does look like they put effort into resisting alternative explanations.

Technically, this isn’t fair because he’s only saying SAT-only is better than the status quo, not that it’s enough better to compensate for running your country in some tin-pot dictatorship where they send IP packets by carrier pigeon.

The real reason grey-dawg is wrong is that the college system is basically a really slow, really expensive SAT which (as other have pointed out) the employer doesn’t have to pay for. People get sorted into prestigious colleges and difficult majors and people-who-graduated roughly by SAT.

Even apart from insanity, there’s the more continuous “Is normal, sociable, plays well with others, etc.” factor that is of genuine importance. But you’ll find in general that people who do what’s considered normal in their society are generally more normal and nice (compare typical German NSDAP members, typical American neo-Nazis). If graduating from HS and sending your SATs to Google was normal, normal people would do it, and the people selected would be as normal as the people at Google now.

Greenspun (of the 10th rule) said roughly all the girls he supervised CS honors theses for were in a file marked “Medical School Recommendations.” They’d realized that STEM is a shit job and acted accordingly. He theorized that men by nature are more likely to focus laserlike on winning the competition to be #1 STEM guy, without stepping back and asking if it’s worth doing. I mean, if a group of highly qualified men are competing very, very hard at something, it MUST be a big deal to be #1. Right, guys? Women. Whadda they know?

If you read Griggs v Duke, technically it says that you can’t use a college degree just as much as you can’t use an IQ test. This isn’t the popular wisdom so you can get away with it for awhile.

Otherwise, I would set up a 1-day unaccredited school that admits purely based on SAT > 1400/2100 and give out diplomas based on that.

The law involves judges using human judgment, so they’d have no problem saying that that is a sham university and using a diploma from it is still discriminating.

Griggs did not say, technically or otherwise, that you can’t use a college degree. The Court very specifically declined to decide anything about degrees (since the case had not involved degrees, they didn’t have to).

Though I think the logic of Griggs applies to degrees, I don’t think anyone has ever gotten a court to do so. Practice since Griggs has allowed degrees to be used as a “condition of employment or advancement,” and no one expects that to change.

Roger, Griggs explicitly talked about degrees.

(whoops, wrong subthread. How do I delete this?)

Left bridge: “This bridge was designed and built by the smartest most qualified people we could find”

Right bridge: “This bridge was designed and built by a random unbiased cross section of society”

Which bridge are you going to drive over with your family in the car? There is discrimination by intelligence, education, and experience for very good reasons. It is a sad reflection on society when people start to question this.

If you tell a random unbiased cross section of society to build a bridge, what do they do? They look around for people who can tell them how it’s done, and if possible, do it for them. Which is sane, which is good.

There is the problem that you need to have a certain level of competence to know that you’re incompetent, but a) groups are much better at this than individuals, and b) It’s not really much of an issue in bridge building. Really, everyone knows they don’t know that. The people who overestimate their abilities to do that, are more likely to be beginning civil engineering students.