I.

Recently spotted on Tumblr:

“This is going to be an unpopular opinion but I see stuff about ppl not wanting to reblog ferguson things and awareness around the world because they do not want negativity in their life plus it will cause them to have anxiety. They come to tumblr to escape n feel happy which think is a load of bull. There r literally ppl dying who live with the fear of going outside their homes to be shot and u cant post a fucking picture because it makes u a little upset?”

“Can yall maybe take some time away from reblogging fandom or humor crap and read up and reblog pakistan because the privilege you have of a safe bubble is not one shared by others?”

Ignore the questionable stylistic choices and there’s an important point here worth considering. Something like “Yes, the feeling of constantly being outraged and mired in the latest controversy is unpleasant. And yes, it would be nice to get to avoid it and spend time with your family and look at kitten pics or something. But when the controversy is about people being murdered in cold blood, or living in fear, or something like that – then it’s your duty as a decent human being to care. In the best case scenario you’ll discharge that duty by organizing widespread protests or something – but the absolute least you can do is reblog a couple of slogans.”

I think Cliff Pervocracy is trying to say something similar in this post. Key excerpt:

When you’ve grown up with messages that you’re incompetent to make your own decisions, that you don’t deserve any of the things you have, and that you’ll never be good enough, the [conservative] fantasy of rugged individualism starts looking pretty damn good.

Intellectually, I think my current political milieu of feminism/progressivism/social justice is more correct, far better for the world in general, and more helpful to me since I don’t actually live in a perfectly isolated cabin.

But god, it’s uncomfortable. It’s intentionally uncomfortable—it’s all about getting angry at injustice and questioning the rightness of your own actions and being sad so many people still live such painful lives. Instead of looking at your cabin and declaring “I shall name it…CLIFFORDSON MANOR,” you need to look at your cabin and recognize that a long series of brutal injustices are responsible for the fact that you have a white-collar job that lets you buy a big useless house in the woods while the original owners of the land have been murdered or forced off it.

And you’re never good enough. You can be good—certainly you get major points for charity and activism and fighting the good fight—but not good enough. No matter what you do, you’re still participating in plenty of corrupt systems that enforce oppression. Short of bringing about a total revolution of everything, your work will never be done, you’ll never be good enough.

Once again, to be clear, I don’t think this is wrong. I just think it’s a bummer.

I don’t know of a solution to this. (Bummer again.) I don’t think progressivism can ever compete with the cozy self-satisfaction of the cabin fantasy. I don’t think it should. Change is necessary in the world, people don’t change if they’re totally happy and comfortable, therefore discomfort is necessary.

I’d like to make what I hope is a friendly amendment to Cliff’s post. He thinks he’s talking about progressivism versus conservativism, but he isn’t. A conservative happy with his little cabin and occasional hunting excursions, and a progressive happy with her little SoHo flat and occasional poetry slams, are psychologically pretty similar. So are a liberal who abandons a cushy life to work as a community organizer in the inner city and fight poverty, and a conservative who abandons a cushy life to serve as an infantryman in Afghanistan to fight terrorism. The distinction Cliff is trying to get at here isn’t left-right. It’s activist versus passivist.

As part of a movement recently deemed postpolitical, I have to admit I fall more on the passivist side of the spectrum – at least this particular conception of it. I talk about politics when they interest me or when I enjoy doing so, and I feel an obligation not to actively make things worse. But I don’t feel like I need to talk nonstop about whatever the designated Issue is until it distresses me and my readers both.

I’ve heard people give lots of reasons for not wanting to get into politics. For some, hearing about all the evils of the world makes them want to curl into a ball and cry for hours. Still others feel deep personal guilt about anything they hear – an almost psychotic belief that if people are being hurt anywhere in the world, it’s their fault for not preventing it. A few are chronically uncertain about which side to take and worried that anything they do will cause more harm than good. A couple have traumatic experiences that make them leery of affiliating with a particular side – did you know the prosecutor in the Ferguson case was the son of a police officer who was killed by a black suspect? And still others are perfectly innocent and just want to reblog kitten pictures.

Pervocracy admits this, and puts it better than I do:

But god, it’s uncomfortable. It’s intentionally uncomfortable—it’s all about getting angry at injustice and questioning the rightness of your own actions and being sad so many people still live such painful lives. Instead of looking at your cabin and declaring “I shall name it…CLIFFORDSON MANOR,” you need to look at your cabin and recognize that a long series of brutal injustices are responsible for the fact that you have a white-collar job that lets you buy a big useless house in the woods while the original owners of the land have been murdered or forced off it. And you’re never good enough. You can be good—certainly you get major points for charity and activism and fighting the good fight—but not good enough. No matter what you do, you’re still participating in plenty of corrupt systems that enforce oppression. Short of bringing about a total revolution of everything, your work will never be done, you’ll never be good enough.

That seems about right. Pervocracy ends up with discomfort, and I’m in about the same place. But other, less stable people end up with self-loathing. Still other people go further than that, into Calvinist-style “perhaps I am a despicable worm unworthy of existence”. moteinthedark’s reply to Pervocracy gives me the impression that she struggles with this sometime. For these people, abstaining from politics is the only coping tool they have.

But the counterargument is still that you’ve got a lot of chutzpah playing that card when people in Peshawar or Ferguson or Iraq don’t have access to this coping tool. You can’t just bring in a doctor’s note and say “As per my psychiatrist, I have a mental health issue and am excused from experiencing concern for the less fortunate.”

One option is to deny the obligation. I am super sympathetic to this one. The marginal cost of my existence on the poor and suffering of the world is zero. In fact, it’s probably positive. My economic activity consists mostly of treating patients, buying products, and paying taxes. The first treats the poor’s illnesses, the second creates jobs, and the third pays for government assistance programs. Exactly what am I supposed to be apologizing for here? I may benefit from the genocide of the Indians in that I live on land that was formerly Indian-occupied. But I also benefit from the asteroid that killed the dinosaurs, in that I live on land that was formerly dinosaur-occupied. I don’t feel like I’m complicit in the asteroid strike; why should I feel complicit in the genocide?

I have no objection to people who say this. The problem with it isn’t philosophical, it’s emotional. For most people it won’t be enough. The old saying goes “you can’t reason yourself out of something you didn’t reason yourself into to begin with”, and the idea that secure and prosperous people need to “give something back” is a lot older than accusations of “being complicit in structures of oppression”. It’s probably older than the Bible. People feel a deep-seated need to show that they understand how lucky they are and help those less fortunate than themselves.

So what do we do with the argument that we are morally obligated to be political activists, possibly by reblogging everything about Ferguson that crosses our news feed?

II.

We ask: why the heck are we privileging that particular subsection of the category “improving the world”?

Pervocracy says that “short of bringing about a total revolution of everything, your work will never be done, you’ll never be good enough.” But he is overly optimistic. Has your total revolution of everything eliminated ischaemic heart disease? Cured malaria? Kept elderly people out of nursing homes? No? Then you haven’t discharged your infinite debt yet!

Being a perfect person doesn’t just mean participating in every hashtag campaign you hear about. It means spending all your time at soup kitchens, becoming vegan, donating everything you have to charity, calling your grandmother up every week, and marrying Third World refugees who need visas rather than your one true love.

And not all of these things are equally important.

Five million people participated in the #BlackLivesMatter Twitter campaign. Suppose that solely as a result of this campaign, no currently-serving police officer ever harms an unarmed black person ever again. That’s 100 lives saved per year times let’s say twenty years left in the average officer’s career, for a total of 2000 lives saved, or 1/2500th of a life saved per campaign participant. By coincidence, 1/2500th of a life saved happens to be what you get when you donate $1 to the Against Malaria Foundation. The round-trip bus fare people used to make it to their #BlackLivesMatter protests could have saved ten times as many black lives as the protests themselves, even given completely ridiculous overestimates of the protests’ efficacy.

The moral of the story is that if you feel an obligation to give back to the world, participating in activist politics is one of the worst possible ways to do it. Giving even a tiny amount of money to charity is hundreds or even thousands of times more effective than almost any political action you can take. Even if you’re absolutely convinced a certain political issue is the most important thing in the world, you’ll effect more change by donating money to nonprofits lobbying about it than you will be reblogging anything.

There is no reason that politics would even come to the attention of an unbiased person trying to “break out of their bubble of privilege” or “help people who are afraid of going outside of their house”. Anybody saying that people who want to do good need to spread their political cause is about as credible as a televangelist saying that people who want to do good need to give them money to buy a new headquarters. It’s possible that televangelists having beautiful headquarters might be slightly better than them having hideous headquarters, but it’s not the first thing a reasonable person trying to improve the world would think of.

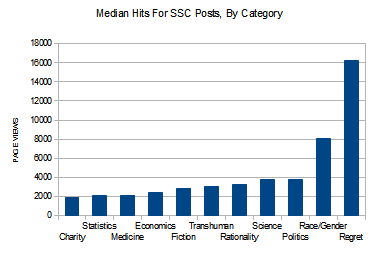

Average number of hits for posts on this blog, by topic

Nobody cares about charity. Everybody cares about politics, especially race and gender. Just as televangelists who are obsessed with moving to a sweeter pad may come to think that donating to their building fund is the one true test of a decent human being, so our universal obsession with politics, race, and gender incites people to make convincing arguments that taking and spreading the right position on those issues is the one true test of a decent human being.

So now we have an angle of attack against our original question. “Am I a bad person for not caring more about politics?” Well, every other way of doing good, especially charity, is more important than politics. So this question is strictly superseded by “Am I a bad person for not engaging in every other way of doing good, especially charity?” And then once we answer that, we can ask “Also, however much sin I have for not engaging in charity, should we add another mass of sin, about 1% as large, for my additional failure to engage in politics?”

And Cliff Pervocracy’s concern of “Even if I do a lot of politics, am I still a bad person for not doing all the politics?” is superseded by “Even if I give a lot of charity, am I a bad person for not doing all the charity? And then a bad person in an additional way, about 1% as large, for not doing all the politics as well?”

There’s no good answer to this question. If you want to feel anxiety and self-loathing for not giving 100% of your income, minus living expenses, to charity, then no one can stop you.

I, on the other hand, would prefer to call that “not being perfect”. I would prefer to say that if you feel like you will live in anxiety and self-loathing until you have given a certain amount of money to charity, you should make that certain amount ten percent.

Why ten percent?

It’s ten percent because that’s the standard decreed by Giving What We Can and the effective altruist community. Why should we believe their standard? I think we should believe it because if we reject it in favor of “No, you are a bad person unless you give all of it,” then everyone will just sit around feeling very guilty and doing nothing. But if we very clearly say “You have discharged your moral duty if you give ten percent or more,” then many people will give ten percent or more. The most important thing is having a Schelling point, and ten percent is nice, round, divinely ordained, and – crucially – the Schelling point upon which we have already settled. It is an active Schelling point. If you give ten percent, you can have your name on a nice list and get access to a secret forum on the Giving What We Can site which is actually pretty boring.

It’s ten percent because definitions were made for Man, not Man for definitions, and if we define “good person” in a way such that everyone is sitting around miserable because they can’t reach an unobtainable standard, we are stupid definition-makers. If we are smart definition-makers, we will define it in whichever way which makes it the most effective tool to convince people to give at least that much.

Finally, it’s ten percent because if you believe in something like universalizability as a foundation for morality, a world in which everybody gives ten percent of their income to charity is a world where about seven trillion dollars go to charity a year. Solving global poverty forever is estimated to cost about $100 billion a year for the couple-decade length of the project. That’s about two percent of the money that would suddenly become available. If charity got seven trillion dollars a year, the first year would give us enough to solve global poverty, eliminate all treatable diseases, fund research into the untreatable ones for approximately the next forever, educate anybody who needs educating, feed anybody who needs feeding, fund an unparalleled renaissance in the arts, permamently save every rainforest in the world, and have enough left over to launch five or six different manned missions to Mars. That would be the first year. Goodness only knows what would happen in Year 2.

(by contrast, if everybody in the world retweeted the latest hashtag campaign, Twitter would break.)

Charity is in some sense the perfect unincentivized action. If you think the most important thing to do is to cure malaria, then a charitable donation is deliberately throwing the power of your brain and muscle behind the cause of curing malaria. If, as I’ve argued, the reason we can’t solve world poverty and disease and so on is the capture of our financial resources by the undirected dance of incentives, then what better way to fight back than by saying “Thanks but no thanks, I’m taking this abstract representation of my resources and using it exactly how I think it should most be used”?

If you give 10% per year, you have done your part in making that world a reality. You can honestly say “Well, it’s not my fault that everyone else is still dragging their feet.”

III.

Once the level is fixed at ten percent, we get a better idea how to answer the original question: “If I want to be a good person who gives back to the community, but I am triggered by politics, what do I do?” You do good in a way that doesn’t trigger you. Another good thing about having less than 100% obligation is that it gives you the opportunity to budget and trade-off. If you make $30,000 and you accept 10% as a good standard you want to live up to, you can either donate $3000 to charity, or participate in political protests until your number of lives or dollars or DALYs saved is equivalent to that.

Nobody is perfect. This gives us license not to be perfect either. Instead of aiming for an impossible goal, falling short, and not doing anything at all, we set an arbitrary but achievable goal designed to encourage the most people to do as much as possible. That goal is ten percent.

Everything is commensurable. This gives us license to determine exactly how we fulfill that ten percent goal. Some people are triggered and terrified by politics. Other people are too sick to volunteer. Still others are poor and cannot give very much money. But money is a constant reminder that everything goes into the same pot, and that you can fulfill obligations in multiple equivalent ways. Some people will not be able to give ten percent of their income without excessive misery, but I bet thinking about their contribution in terms of a fungible good will help them decide how much volunteering or activism they need to reach the equivalent.

Cliff Pervocracy says “Your work will never be done, you’ll never be good enough.” This seems like a recipe for – at best – undirected misery, stewing in self-loathing, and total defenselessness against the first parasitic meme to come along and tell them to engage in the latest conflict or else they’re trash. At worst, it autocatalyzes an opposition of egoists who laugh at the idea of helping others.

On the other hand, Jesus says “Take my yoke upon you…and you will find rest for your souls. For my yoke is easy and my burden is light.” This seems like a recipe for getting people to say “Okay, I’ll take your yoke upon me! Thanks for the offer!”

Persian poet Omar Khayyam, considering the conflict between the strict laws of Islam and his own desire to enjoy life, settles upon the following rule:

Heed not the Sunna, nor the law divine;

If to the poor their portion you assign,

And never injure one, nor yet abuse,

I guarantee you heaven, as well as wine!

I’m not saying that donating 10% of your money to charity makes you a great person who is therefore freed of every other moral obligation. I’m not saying that anyone who chooses not to do it is therefore a bad person. I’m just saying that if you feel a need to discharge some feeling of a moral demand upon you to help others, and you want to do it intelligently, it beats most of the alternatives.

This month is the membership drive for Giving What We Can, the organization of people who have promised to give 10% of their earnings to charity. I am a member. Ozy is an aspiring member who plans to join once they are making a salary. Many of the commenters here are members – I recognize for example Taymon Beal’s name on their list. Some well-known moral philosophers like Peter Singer and Derek Parfit are members. Seven hundred other people are also members.

I would recommend giving them a look.

Re possible reasons for passivism: my personal one is that I had tried activism a few times over the years, and it backfired in various traumatic and unexpected ways, even though my words and actions were indistinguishable (to me) from those taken by other, much more successful activists. My conclusion was that my social IQ is about 70 and I should not try to lead anyone anywhere, ever.

There’s lots of useful volunteer work you can do without leading. You can do research, do grunt work (mailings, postering, leafleting), act as a volunteer bookkeeper, etc. Maybe you have particular sklils (software dev, graphic design, etc.).

There’s no reason activism must be equal to working with large groups of people. Many nonprofits can make good use of people who’d like to do solo work.

I have no problem at all refusing to reblog things on Tumblr or posts on Facebook, whether it’s “Little Timmy’s one-legged puppy needs a new collar for Kwanzaa if you don’t like this post you are a heartless monster!!!!” armtwisting or the more serious HOW CAN YOU SIT THERE WITH THE ELECTRIC LIGHT ON IN YOUR WARM HOUSE WHILE PAKISTAN/MEXICO/THE GREAT BARRIER REEF ARE BEING DESTROYED????

And the reason for this is because all my life I’ve been susceptible to guilt-tripping. All my life I’ve been a people-pleaser. Now that I’m old and decrepit and falling apart, I finally have the confidence to say “No.” Whether it’s because :

(1) No, I DON’T care about your cause. Yes, I’m a horrible heartless monster. Little Timmy can go whistle as far as I’m concerned.

Or whether it’s because:

(2) No, I’m NOT going to like/post/reblog. Because me doing it is only piling on the mass frenzy and will achieve precisely bugger-all in terms of doing anything except stroke your ego about being a great activist who is getting the news out there and Getting Stuff Done. If you in fact are not a great activist who is not getting stuff done, save that the only stuff being done is having a herd of followers reblogging, then you are useless also.

I’ll care about what I choose to care about. I no longer will live down to the tyranny of expectation about “what kind of person are you?” It is entirely possible that I am a shitty, selfish, human being. But genuine outrage and pain is one matter, someone who likes to plume themselves on being an ally or an activist or an organiser simply because they urge reblogging with threats of “you are SCUM if you ignore this” are not doing anything useful, are not helping, and are part of the problem.

Well said! If this were Tumblr I would reblog it.

What sort of experiences did you run into? Perhaps your experiences could be helpful to others!

Do you think it was a case of not being suited to the specific group(s) that you were in? Or do you think it was a more general problem?

This is a nice idea, and while I usually don’t give to charity, if I had a salary right now I would probably go find something to give something to.

Unfortunately, I very much doubt that it’ll do much to reduce the number of people shouting about how it’s a moral obligation to retweet $CAUSE. The purpose behind that message — whether you model it as the occulted true desire of the leaders of the movements which spawned it, or the final cause of that feature of the message as a self-replicating meme — is nothing to do with people wanting to make the world a better place as best they can. Its purpose is to generate support for the message, and place more political power at the disposal of the movements and/or ensure the replication of the meme. It hijacks the moral response in order to get adherents, just like it hijacks the tribalistic response. This message isn’t anything like an answer against those who intentionally spread that particular meme; it’s irrelevant to the real argument.

That said, it’s still worth having posted, and it’s worth signal-boosting. While it may not strike at the heart of the meme’s real purpose, it may well act as an effective inoculant — at least for some people, in some places, who may otherwise have been vulnerable to getting drawn in and thinking that they’re morally obligated to parrot $CAUSE. That can’t but be a good thing, both in limiting the meme’s spread, and for the happiness of those people. If that was the dominant message, rather than the contrasting meme, maybe I could stop being so damned cynical. <_<

Thanks for writing this.

This strategy doesn’t change the incentives for the message, but might inoculate against it in its listeners.

I like this post but could we add one caveat? Give 10% of your income to charities with strong evidence to support their effectiveness given the values system you have. Giving 10% of your income to Kony 2012 campaigns might not do all that much good for the world. I’ll grant that if we had 7 trillion dollars worth of charity money floating around, a charity wouldn’t have to be all that marginally effective to still be worth getting some piece of that pie, but until that happy day let’s make sure to keep the “give to charities that are useful and that your ten percent can actually help” in mind.

The Giving What We Can Foundation mentioned in the essay is already on the case:

“We recommend the most effective charities working to help people in developing countries. The best research in effectiveness can help you to make the biggest possible difference with your money. “

What would you estimate is the charity level (lives saved) of writing/re-blogging posts like these?

Depends on the viewership, in terms of how likely it is this will influence them, and how many people will see it. If one extra person, on a $30k annual income donates $3k annually for (say) 5 years due to this post, that’s several lives assuming somewhat effective donations.

The tricky part in these calculations is assignment of “cause.” Someone might see this post and decide to donate so we might attribute it to the post. However, they might attribute it to themselves. GiveWell/Giving What We Can will say they helped move such and such amount of money. And let’s not forget the charity itself, although arguably that part is taken care of as part of “room for more funding” calculation. Counter-factually if a single one didn’t exist, the donation would not happen. All of these existing might be necessary for the cause be solved. This isn’t an argument against giving, rather an adjustment of how many lives “you” saved vs. all the enablers and influences.

Because of that spread of responsibility, it might be worth up-weighting certain actions where responsibility is completely your own. However, i still doubt that things like helping your friend with a resume or solving a work problem in non-confrontational come anywhere close the impact of effective charities.

I don’t think the idea of responsibility or cause needs to work like that. Is it the wheels, suspension, fuel, or engine that makes the car go?

You can’t add up the lives each individual saved, and get the total number of lives saved. You can look at which actions will save more or less lives. The former doesn’t matter when it comes to making decisions.

If nothing else, it inspired me to throw $100 at GiveDirectly and subsequently brag about it on two different forums that are inhabited by several people who might be motivated to do the same.

That’s awesome!

It may not be concrete “number of lives saved”. But cooling down hysteria is a valuable service, even if only as a metaphysical counter to the vast number of screaming guilt-tripping SPREAD THIS MESSAGE GET OUTRAGED YELL AND POUND THE TABLE messages that get spewed out.

I’m at the stage now that even when I see something I know is wrong or mistaken being blasted as THE TRUTH, I am so weary of fights on the Internet that I simply let it go. What’s the use, they have their mind made up already, I can’t change that, and besides I’ve seen this being cemented in people’s minds as the really real true facts, I’ll never get to enough people to counter this, there’s no point trying.

At least Scott is not at that level of apathy, and who knows? Someone outside the readership here may come across this post, read it, and then stop a minute when they’re next on the point of engaging in the reblog/post this or else!!!! frenzy, and think about what they’re doing and what they hope to achieve.

How many lives are saved with this post: I’d guess quite a few.

I see this blog as the best moral and enlightening guideline I can find in this so confusing world.

So I try to be better. But I am no saint. Right now, with my lifestyle, my debt and the legal battles I still have ahead of me, 10% is too much of a burden.

But as a result of this post, I have decided that my new year’s resolution is going to be to increase my charity level to 3% (from 0.8%).

And since I have now said it openly, I have a high moral incentive to carry this through.

Looking at

http://childsdream.org/how-we-help/

right now, because I like Asia. They operate in an area which has given a lot to me, so it’s fair I give something back.

Well done for publicly committing! I’d recommending looking at the GiveWell-recommend charities. If you particularly want your donations to work in Asia, you might look at Deworm The World, which is recommended by GiveWell and which works primarily in India and Kenya.

I have had three people tell me they are going to join GWWC and start donating 10% as a result of this post.

Convincing other people to donate money seems so much easier and more effective than donating yourself (even if you don’t already have a big blog) that I am suspicious of it.

The director of my department, who also runs a charity aimed at ensuring education for girls in Africa, has stated more than once that the hardest part of running a charity is asking people for money. He also said it’s surprising how readily people respond, and how little denial stings over time. Most of all, “You’ll miss every shot you don’t take; you won’t get any dollar you don’t ask for.”

I’m not certain of the effectiveness of his charity vs. others, given that I haven’t reviewed it and dead girls can’t be educated. However, speaking with him and other very charitable people in my life has taught me that convincing others to give is easy… with one caveat:

You must give. People will trust a demonstrable investment; people do not trust a bell-ringer who they don’t see drop in a penny every now and then. It would be nice, given BlackLivesMatter etc, if people thought that way in regard to activism.

Four. (I did it too.)

Five.

This post will probably cause me to give more money to charity.

I am interested in this, though:

> If charity got seven trillion dollars a year, the first year would give us enough to solve global poverty, eliminate all treatable diseases, […]

Probably a comparable or greater amount of money was collected worldwide as taxes last year. So why didn’t we manage to accomplish all these wonderful things?

Those seven trillion dollars are in addition to extant spending. Also, government priorities are not the same as charity priorities. There are very few charities dedicated to military research.

1. Almost all taxes are spent in the country of origin. Rich countries have gone pretty far to eliminating starvation, homelessness, easily treatable infectious diseases, et cetera. Their failures are often more political than economic – for example, we don’t give everybody free housing not because we can’t afford it but because welfare is controversial.

2. Most taxes don’t go to idealistic social projects. The US spends most of its taxes on the military, Social Security for old people, health care for rich people in a country with super-duper inflated health care costs that are mostly useless, and interest on the federal debt. Even money that goes to idealistic projects is extremely politicized in its exact placement.

3. The charity would be in addition to existing taxes, so if taxes have done half the job, charity could do the other half.

I can’t help but nitpick: We don’t give free housing to everyone, because the level of housing we would be able to provide would be insufficient.

The limiting cost of housing for most people is not the physical building, but the land. A naieve approach might note that there is much unoccupied land in the US that is available for housing for dirt cheap, but this housing is in the middle of nowhere. Sure you could build free housing for the poor in rural South Dakota. But that housing would be in rural South Dakota. It would be far from meaningful infrastructure, economic development, etc. You might give homeless folks roofs over their head, but you’ll accidentally lock them out of economic prosperity by placing them in the middle of nowhere.

On the other hand, if you wanted to provide them with housing anywhere close to the economic opportunities in urban areas, all of the sudden you’re facing up against a pretty obvious blocker: there’s already houses there, and there are already people in them. At this point you can do a few things. You can try to regulate supply, through below-market housing quotas, rent controls, or what have you. History, as well as economic theory, shows that this doesn’t work. You can build denser housing. Most existing residents are not too fond of this, and if too much of it happens all at once it can stress local economic and logistic systems to the breaking point. You can start building outward in inexpensive suburbs. This causes people to be dependent on (in the US, virtually nonexistent) public transit, or compels them to spend large sums of money on buying/maintaining a car (and the opportunity cost of sitting in LA-style gridlock).

And, throughout all of this, you’re hit with a familiar problem in any free market: If two people want one thing, the person with more money wins. For virtually any proposed solution, people with more money are going to get their preferred housing before people with less money get any. You can try and use the law to lock them out, but like I mentioned above, this rarely works in practice. Additionally, there are strong moral reasons why this might not work at scale (see: arguments over who is allowed/entitled to live in San Francisco vs who should be (forcibly?) expelled).

The only long term viable solution to housing is for there to be enough housing that the market clears. But housing is restricted. Partly geographically, partly economically, partly by regulation, and partly just because housing is (literally, in 3d space) a positional good: its price depends a lot more on where it is than what it is.

Housing is a hard problem, and I think it’s not telling the whole story to chalk it up purely to a political failure

My suspicion is that any society that manages to solve the ‘building sufficient adequate housing for the poor in areas close to centres of economic activity’ problem is likely to also be the sort of society that manages to solve the ‘link the suburbs up to economic hubs with decent public transport’ problem – or at least that failure to one is likely to be a symptom of underlying factors that cause failure to do both.

I don’t understand, why can’t there be centers of economic activity where there’s housing?

There are. But some people like suburbs precisely because there’s no economic activity there.

Grumpus – economic activity won’t just show up because there are potential workers there; especially if those potential workers are people who’ve had a hard time getting or keeping any job beyond those barely productive enough to pay minimum wage. And even if the potential workers are desirable, there are other conditions which may deter economic activity.

Of course, if someone had built lots of free housing for the poor in western North Dakota a decade ago, many of those poor people would be much better off today.

“Hard Problem” in certain inefficient nations with political failure, possibly.

Locally, we subsidize the construction of housing (To help the market clear), which is then rented out to poor people who are being given money with which to do this.

This also solves the problem of perverse incentives – the subsidies are not so great that you can make money building appartments in the local equivalent of South Dakota, you must still rent them out later and are thus encouraged to build where people will rent.

This does create suburbs, which is an easily-solved problem with public transportation.

Or to rephrase and answer your actual quote:

Housing is a solved problem, and only political failure is preventing you from adopting the solution.

Yeah…there are all manner of ways to fuck up urban planning, but getting the basics right isn’t actually all that hard, and I find it odd that a lot of people treat it as basically insoluble.

Where are these places that have completely solved the problem of housing? A quick search suggests that Europe has roughly the same rate of homelessness as the US, and other parts of the world are doing no better. Furthermore, housing “crises” in the US tend to be along the lines of “housing costs more than I want to pay”, and doesn’t actually mean “I have nowhere to live.”

Some of the better-run public housing projects, “council housing” in British English, seem to come close. This guy seems to be making the case for New York City, though I understand things are moving in the wrong direction lately.

I think it might be more accurate to say that “housing” is a solved problem in the sense of providing a weatherproof enclosure of durable materials fitted with indoor plumbing, electricity, and the other requirements for minimally acceptable first-world housing, within reasonable commuting distance of an economic hub. Find the cheapest land within 10-20 miles of the chosen hub. Contract out the construction of large, boringly identical blocks of apartments or flats that meet your minimum standard. If necessary, put in a light rail line.

Then subsidize whatever fraction of the rent (up to 100%) is needed to get the homeless poor under the roof. This can be done for an up-front cost that most first-world taxpayers will be willing to see devoted to such use, and probably second-world authoritarian governments as well.

The nearly insoluble problems are: First, this sort of project is terribly easy to turn into a pork-distribution machine for labor unions and crony capitalists, which can greatly magnify construction costs. Second, it preferentially attracts on the resident side people who are economically incapable of securing housing on the private market (which correlates with being bad neighbors) and on the management side the sort of bureaucrats who like throwing their weight around without accountability. And third, it largely removes the incentive to maintain the housing in livable condition, at least from anyone who would have the ability to do so.

Hence, all but the very best-run public housing projects tend to decline precipitously in quality from the very start. Often before they even open their doors. I don’t think anybody has codified the mojo that allows a few places to avoid this fate.

Also: If your metric for “solved the housing problem” is 0% homelessness, that’s not going to happen. There is an irreducible minimum homeless population composed of people whose mental illness causes them to see shelters/housing projects/whatever as Illuminati Mind Control Centers, people who are so committed to self-reliance that they see accepting such charity as sinful, people who are living out of their cars because they are certain that their fortunes will improve Real Soon Now and that they are not the sort of people who will end up warehoused in public housing, and people who are such bad neighbors that they will be thrown out of any housing arrangement that isn’t an actual prison or locked-ward psychiatric hospital.

I suppose you could make homelessness a criminal offense punishable by imprisonment; barring that you’re going to be stuck with a few percent homeless.

>Housing is a solved problem, and only political failure is preventing you from adopting the solution.

To say that slums are a “solution” to the problem of housing is to assume anything is better than homelessness.

i believe there are also people who have been exposed to enough violence in homeless shelters that they’d rather take their chances on the street.

Subsidising housing can be an expensive way of helping the poor as it creates an incentive for non-poor people to indulge in fraud to get the housing subsidises. I don’t know of any studies, but I’ve heard a fair bit of rumours about how much low-income housing set asides that developers were required to build is occupied by not-so-low-income people.

(Obviously, giving money directly to the poor also creates incentives for fraud, but, as you need to do that anyway to enable some people to buy things like food and heat, you also need to check for fraud, so sunk costs).

I am not recommending it as a strategy, but I think that communism has left my east-european country full of dense, thus cheap, and nicely center-adiacent living spaces. I have always lived in (semi/central) blocks of flats, I could afford the rent, and could realistically solve my businesses using public transport or bikes. I think a significant portion of y’all’s aversion to denser living is not only cultural, but land-developer-originated propaganda.

“Most existing residents are not too fond of this”

Which makes it a political problem, not a capability problem. We could provide enough housing in urban areas. The affordable end might be small and dependent on public transit rather than owning cars, but we could do it. We choose to require parking spaces and minimum apartment sizes instead.

Changing zoning to allow building more densely packed housing seems like it should go a long way there.

This doesn’t chime with what I recall of my urban economics (at least pre-trains, motorized buses, etc.). Because with housing you can fit people in more or less densely. Selling 40 people $100,000 apartments raises more money than selling one person a $2 million house. (Though profits depend on the relevant costs).

Eg New York City, until the subway was built, had a pattern of the rich selling off their mansions and moving out a bit, with their mansions being replaced by tenement housing to accommodate the masses of poor. Or in London, there were lots of Tudor mansions with extensive pleasure grounds along the river, some of which remain, but, over time, the new mansions moved further out, to Hampstead Heath, or further (I’ve seen the modern equivalents in the hills of Surrey), and the rich built grand town houses, in the West End but typically not that large by country-home standards and nearly always without extensive grounds (exception being Buckingham Palace, where the King could hit up Parliament for funds). Eg the Duke of Wellington’s home in central London is nothing on the scale of Blenheim Palace in the English countryside (built for the Duke of Marlborough, the 17th century military equivalent of the Duke of Wellington). Meanwhile, hordes of very poor people were living in London’s East End, where they could walk to work.

All this changed when there was mass, non-pooing, transport possibilities, and changed even more with elevators that make living in a 20-story apartment building doable. I am not saying that we should expect poor people nowadays to live in 19th century slums like those of London and New York. I’m just saying that the bidding war between the rich and poor for land for housing doesn’t necessarily mean that the rich always win.

I’d say rather that the rich normally win, but that sometimes the rich decide to use the expensive land as a source of prestige by building a fancy house in it and living there, and sometimes as a source of money by building cheap housing there and renting it out.

Obviously Mr Rothschild is unlikely to be the one knocking down the Rothschild mansion to build tenements, because he likely liked the mansion, but Mr Monaghan might well do so because he likes rent more than a mansion of unfashionable style; later Ms Li might knock down the Monaghan mansion and build tenements for rent; later Ms Adebayo does the same to the Li mansion, unless by that point having your income come from low-rent housing even through eleven layers of well-briefed intermediary is regarded as an irredeemable social flaw

When the rich decide to use the land to build housing for the poor, the poor win too. Because they get a place to live.

Economies are not zero-sum.

Another argument for giving to charity, which may sway some of your libertarian-leaning readers, is a reminder that the (US) government does not tax you on anything you donate to a registered charity. It’s like Moloch wants you to defeat him, by giving you tax breaks!

Caveat: You have to itemize deductions and have sufficient deductible expenses to surpass the standard deduction. As such, many of your donated dollars may be taxed just like normal before some of your donated dollars are untaxed. For low and moderate income individuals, the tax implications very well may be nil.

If you’re already itemizing deductions, for example because you have a mortgage, then each dollar you donate is like a dollar you never earned for tax purposes.

If you wouldn’t itemize deductions if not for your donations, then yes, you’re right.

If you only donate to one charity, which you probably should be doing anyway, then itemizing deductions wouldn’t be difficult.

In the US, itemizing deductions does not require listing each individual charitable donation if no individual donation was over $250. See 1040 Schedule A, Line 16, and page A-9 of the instructions. Even if it was over $250 for a single donation, they just tell you to keep a receipt for your records, not to send one in.

The issue isn’t the complexity, the issue is that there is a very large deduction that can be claimed only if one does not itemize.

I’m sure there are reasons this is oversimplified but, roughly, you want to itemize if the total things you could deduct add up to more than the standard deduction. This is $6200 for a single person or $12400 for a married couple filing jointly. So, if you are giving 10% to deductible charities, this applies if your income is above $62K as an individual or $124K collectively. That’s high (90% percentile and 73% percentile respectively), but not at all impossible given the number of tech people reading this blog.

If you have a mortgage, it is almost surely to your advantage to itemize.

Note also that you can generally (if you itemize) deduct state and local property and income taxes (as well as medical expenses above 10% of your income and job expenses), so even if you’re not taking the home mortgage deduction, especially if you have relatively high income, it might be worth it to itemize.

Also medical expenses over a certain level.

When considering whether to itemize or not, be sure to get a Schedule A and look at what you can deduct.

Similar things are true in other jurisdictions. For instance, in the UK there is a scheme called “Gift Aid”; if the proper formalities are observed, then when a taxpayer gives to a registered charity the income tax they’ve paid on the money is returned. Some of it goes to the charity, and some to the taxpayer.

Just because the government does something doesn’t automatically make it the work of Moloch. That being said, I’d be curious to learn the history of charitable contribution deductions and how they became a thing.

According to this, it was born from the worry that introducing an income tax would soak up the money that was previously going to charity.

Arguably this is a bad thing from a moral viewpoint. The government has calculated somehow that it needs $X a year to fund whatever the government does. That need for $X doesn’t go away if people give money to charity, so, the more charitable deductions are taken, the more taxes must go up somewhere else to compensate. If two people, A and B, have similar incomes and similar circumstances in other relevant ways (eg number of dependent children), but A gives more to charity as B is paying off student load debt, or has heavy child support obligations or what not, why should B’s taxes go up?

I’ve been wondering for a while – why isn’t the use of force a more popular political or charitable cause? I would donate a lot to anyone who was willing to take a gun and live in anarchic parts of Africa while trying to set up a functional democratic government. It’s actually something I’ve considered doing myself, though ultimately I’m too selfish for it.

Obviously, imperialism is a potential issue, and corruption another. But it’s hard for me to believe that there’s no one born in those regions moral enough to want to achieve this. If someone were to start a charity for this cause, would it be illegal in the US/Canada or Europe to donate to it?

Relatedly, why aren’t any private corporations trying anything like this? It seems like completely controlling a modernized country, even if it were small, would be worth it. Am I underestimating the difficulties here?

I wondered the same thing. Security concerns are a huge problem that prevent different kinds of aid from being effective — there’s no point in building schools when the kids end of getting kidnapped or killed. The South African mercenary firm Executive Outcomes successfully crushed the RUF in Sierra Leone with few problems, before being forced to leave for political reasons. Obviously uncontrolled mercenary firms are bad, but if there were a few private battalion-sized units that the UN could contract out it would be a godsend. No need to stand by and hand-wring as Rwanda happens because risking military casualties is politically sensitive. No more Srebrenicias because of incompetent or intimidated troops.

EDIT: People have tried to do things like that, it’s just politically unfeasible. This is a particularly fun one, featuring Margaret Thatcher’s son and some former SAS.

Submitted without comment.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/United_Fruit_Company#History_in_Central_America

“imperialism is a potential issue”

No, imperialism is the name of what you are describing, or at the least the exact image it would present.

But at least in theory, benevolent imperialism could be considered justifiable (in a utilitarian sense). Strictly in theory, mind you, the last two wars have shown just how disastrously wrong nation-building can go.

Sure, but one has to consider that one is working with humans. Is it worth making peoples lives better if you make them miserable in the process? That is, is it worth bringing order and technology to the third world if every way of doing so effectively causes them to feel resentment such that the only “utilons” or “hedons” gained are your own for being such a swell chap?

It’d probably save time just to drop the rice off with the local warlord and tell yourself he’ll distribute it fairly.

>Is it worth making peoples lives better if you make them miserable in the process?

I’d consider that a contradiction in terms. If bringing order and technology to the third world makes people miserable rather than happy, it isn’t making their lives better, and if it makes their lives better, they will be less miserable.

Has that ever happened? I mean, it’s common for net-positive policies to nonetheless make certain political coalitions really mad, and it’s common for policies intended to meet people’s basic survival needs to backfire horribly. But I can’t think of a policy that ever successfully met people’s basic survival needs but nonetheless made them so mad that it failed for that reason alone to be net-positive.

Yeah, the mission civilisatrice and the “white man’s burden” were not well received by the people who ostensibly benefited from them. But I was thinking more of sending a mercenary unit to crush the RUF or ISIS, which wouldn’t provoke the same resentment as foreign rule.

@Taymon

The occupations of Iraq and Afghanistan come to mind. Large segments of the population objected to having foreign troops present, even when said troops were there in support of their own elected governments.

“But I was thinking more of sending a mercenary unit to crush the RUF or ISIS, which wouldn’t provoke the same resentment as foreign rule.”

It would just create a nice power vacuum, struggles between factions with a selection for desirable traits until the next most ruthless group takes power. And starts acting with as much violence and disregard for your principles as the overthrown group. We’ve been there, done that, got the perks.

If those occupations were net-negative, then it was because they caused people living in those countries to get killed, not merely because they caused them to become annoyed about having foreigners in their country.

@Taymon

It does not stop at people being killed (as in, the somewhat easy to compute direct bodycount). It’s also institutions being toppled, infrastructures being destroyed, and very long term consequences of the forced destabilization. China after the opium wars for example.

Sure, but those things are bad primarily because they kill people. I was arguing against the idea that the occupations were net-positive in terms of lives saved, even after taking into account longer-term factors, but nonetheless were bad because they made people mad. See also this post from Scott’s old blog about dystopian fiction, which makes a related point.

@Taymon

1) my point was that you will have a very hard time counting how many people dead as a result of your action.

2) from the point of view you are stating, Mao is the greatest humanitarian in history., and Stalin is a close contender. See here

“Mercenary unit to crush ISIS”

The average person in the middle East, excepting the sadly shrinking Christian minorities, may prefer to live in a nominal Islamic state run well with lax moral regulations, and be inwardly displeased by the harsh rule of ISIS when they take over, however they may be even more displeased to have there religion humiliated by infidels whenever a regime an infidel mercenary group dislikes takes power.

This may seem strange because the average person in the middle east is not interchangeable with the average person at a Berkley keyboard.

If the factual claims in that blog post are true, which I highly doubt, then sure, Mao was a great humanitarian. My objection to communism isn’t that it prevents people from actualizing their highest selves, it’s that as far as I can tell it’s worse than capitalism at meeting people’s basic survival needs.

Is the cost of colonialism really a matter of resentment, or is it more that colonialism is unaccountable power, so you get things like the salt tax in India (and not getting enough salt is a serious matter, especially in a hot climate), taking children from their families to raise them differently (and frequently worse), not letting people use their own languages, and probably more I’m not thinking of?

What if colonies had the power to regularly vote on which empire controlled them?

It seems the main, if only problem with imperialism is that the natives have no way to hold the empire accountable. That and empires fight over colonies. Once all that is replaced with nonviolent competition, is it still a bad system?

I think colonialism is a more accurate name for what is being proposed, but it runs into the same problem.

Both imperialism and colonialism are more universally unpopular than they are universally wrong or harmful. If a new name helps people discuss a proposed new instance of a thing on its specific merits, that doesn’t strike me as a bad thing.

Possibly an impractical thing, given the certainty that opponents of any such plan would go out of their way to relink it with the hated old words.

A group of libertarians tried to do this in Honduras. It was shut down by the court.

http://www.theguardian.com/world/2012/oct/04/honduran-judges-reject-model-cities

Came here to post just that, and it wasn’t a greatly violent venture as well. It was just politely asking for a space to be carved out, and was roundly refused.

No matter how politely I ask for a share of your living room, you are quite likely roundly to refuse, and it’s perfectly reasonable for you to refuse.

I think a better analogy would be:

You own vast tracts of mostly unused land, with you and your extended family living on only a small percentage of it. You are pretty comfortable, but most of your family is barely surviving. Somebody comes to you and offers to use his own resources to build some orchards and gardens in one unused corner of your land, part of the proceeds from which will go to you and your family, which is a good thing, because you happen to have thousands of extended family members living on your property, and many of them are starving.

Sure, you COULD say no, but there doesn’t seem to be a good reason to. In fact, it kind of seems like you owe it to your family to say yes.

Maybe they remember when Mexico let a bunch of Americans settle in Texas.

The charter cities idea as I’ve seen it presented is primarily about giving people who are already citizens of the country a chance to live and work under a more favorable legal regime, not about carving out a space for foreigners to live, though obviously a lot of the initial investment capital is coming from abroad.

Also, who, on average, enjoys higher living standards: Mexicans living in Mexico or Mexicans living in Texas? Related question, if you were going to be a Chinese person growing up in the 50s, 60s, or 70s, would you rather have been living under the “native” rule of the PRC, or under the crushing imperialist thumb of British Hong Kong?

This is not to defend imperialism per se, but rather to point out that being oppressed by people who share your language, genetic makeup, and/or culture, is not, in my mind, preferable to being left alone or provided with more favorable conditions by people who don’t.

“The charter cities idea as I’ve seen it presented is primarily about giving people who are already citizens of the country a chance to live and work under a more favorable legal regime, not about carving out a space for foreigners to live, though obviously a lot of the initial investment capital is coming from abroad.”

If the host country was to allow open borders to the libertarian city-state, there are obvious reasons for the host government to object. The city-state would drain away businesses that prefer the less regulated state, and they would use it as shelter to avoid paying taxes or following government regulations. (to a lesser extent something like this happens in the United States due to differences in tax policy and regulations between the “states”)

Yes, I can see why the governments of the country would not like it, because, from their perspective, it is competition. Governments, like all other organizations, prefer not to have competition. But it’s good for the people, who not only have the choice to move to the new place, but who will probably enjoy better governance even if they don’t move, since the original government may have to do a better job to keep people from leaving.

I think things would be so much better in general if people stopped viewing governments as transcendent embodiments of the “will of the people,” and instead as what they really are: territorial monopolies on taxation and the provision of certain services, like law and its enforcement.

Under this latter conception, governmental competition will nearly always produce better governance, as competition does with just about everything else.

I know nothing about Honduras so this is going to be a more hypothetical scenario, so lets say the host-state in country is slightly left-leaning.

Presumably the reason they have their higher taxes and business regulations is because they think it helps people, regardless of whether this is true or not. So they think allowing the businesses to go unregulated and untaxed is hurting people, regardless of whether this is true or not. So its not just about competition.

Now, you seem to be a libertarian of some sort, so you either disagree with their claim, have a different value system, or both. Me; I think that letting people do that is inviting in Moloch, and that the most competitive economic system is not necessarily the best according to my value system.

Well, here’s a question: presumably you don’t favor world government, correct? If not, then you are in favor of some level of governmental competition. Assuming that is the case, then what level of competition is ideal? Generally speaking, very small nation-states and city states do much better, on average, than larger states surrounding them: citizens of Hong Kong, Singapore, and Monaco have much higher average living standards than citizens of Guangdong Province, Malaysia, and France and Spain, respectively.

Presumably you don’t like the idea of people being unable to leave a country in which they don’t like living, either due to explicit legal barriers, or prohibitive personal and financial cost (and it’s almost always harder to move out of a geographically larger nation)? If not, then why would more options for people who don’t want to live in, say, a high tax environment be bad? Unless you think citizens have an obligation to continue living under a regime they don’t like?

Well, I do like the general idea behind Scott’s Archipelago, though I am concerned that economic issues might make the idea unworkable in a pre-post scarcity world. But Archipelago is not like international competition, rather it is just an especially tolerant variety of a liberal or even leftist state. Archipelago enforces freedom of movement between communities, (both negative and positive), prevention of externalities like pollution, and re-distributive taxation. And it implicitly engages in surveillance state stuff.

So I guess what I’m saying is, for people to have freedom to choose their society, you need a liberal-ish world-state or at least world-alliance to enforce their freedom. Otherwise you end up with nasty states preventing people from leaving as they please and doing nasty things to them.

“Presumably you don’t like the idea of people being unable to leave a country in which they don’t like living”

Libertarians should understand the difference between “I don’t like X” and “I think people should be forced to pay to stop X”. I don’t like the idea of people starving, but I also don’t like the idea of taxing everyone 90% to give away to starving people. Opening borders causes immigrants to be a drain on public resources. Those public resources are essentially owned by the citizens jointly, and should not be given away any more than property held by the citizens individually should just be given away.

Does that argument apply to anyone who is likely to be a drain on public resources? For example, if someone is likely to live on disability all their life, should they be deported? And if we something like a UBI, should anyone who’d take more out of it than they’d pay into it also be deported?

Whatever your answer, this is at most an argument for excluding immigrants from the welfare state, which doesn’t necessarily require keeping them out of the country. For example, you could have open borders and a citizens-only welfare state.

Treating public resources as jointly owned by the citizens does not imply limiting someone to a “fair share” of resources, so this would not imply kicking out citizens at all, whether for disability or otherwise. For that matter, it doesn’t even mean we can’t let disabled people–or anyone else–become citizens; the joint owners can arbitrarily give away their own property. It does, however, mean that there is no *principled* reason why such a society *should* give away citizenship to all comers. (And a government that is imperfectly democratic can actually give away citizenship wrongly.)

And you are correct that it doesn’t imply not letting them physically live in the country, just not letting them use public resources. But this is one of those cases where being half-libertarian can be worse than being all-libertarian or none; you can’t just let in the immigrants, say “we’ll keep them from using resources some day when it’s feasible”, and think that at least you’re halfway there.

Doesn’t it imply that? If someone has a certain share in ownership of resources, it’s reasonable that they’d be limited to that share. You’re right in that the joint owners can choose to give away more of their property, but if they’re choosing to give it away to natives (who are strangers to them and about whom they have no particular reason to care about), they can give them away to immigrants as well. It’s one thing to prefer a friend or family member to a stranger, but it’s arbitrary to prefer one stranger to another.

Oh, the rejection of the model cities projects makes me so, so angry. The local governments obviously know the prosperity achieved there is going to make them look bad and that they’ll be stuck with competition for citizens, but they always fight against it using arguments about national dignity, “Neo-Imperialism,” etc.

You know what improves national dignity? Having food and clean, running water?

I hope Paul Romer is going to keep working on the idea. Last I’ve seen, he was doing something in NYC, but I think the third world needs his efforts more. Though a bit outdated now, I think his TED talk still does a good job outlining the basic idea, and in addressing the “neo-imperialism” criticism:

http://www.ted.com/talks/paul_romer?language=en

National dignity is a terrible reason to stonewall a project.

Concerns about extraterritoriality and colonialism are much more valid, to my mind. I think the charter city is a defensible project, and one that might be worth trying, but I don’t think it’s nearly as one-sided as you’re suggesting.

It got unrejected later.

Oh, that’s hopeful. Though I can imagine ways it could go wrong, it seems very much worth trying.

You’re better off contributing to seasteading.org which will increase the number of sovereign and quasi-sovereign cities in the world. This benefit will trickle down to people with lower skills, if not overtaken by the population explosion.

However, if perversely inspired by the previous post, you’re interested in something more controversial, your plan for violent takeover is probably more controversial.

I think it is hilarious that libertarians want free, open borders, and an island nation with a twenty mile moat.

(I understand this is not in all cases the same people)

Not libertarian, but I like to think of it as “free open borders, but not for tanks”.

There are two primary reasons for the Seasteading idea, so far as I understand: 1. there’s basically no habitable land on earth not already claimed by some state, and 2. if one’s land is floating, moving away from a community which no longer reflects one’s values is super easy.

It’s not about keeping people out (other than the agents of existing states); it’s about freedom from the territorial claims of existing regimes and also those of any potentially pushy neighbors. It’s kind of like Nozick’s imaginary universe in which the ideally sized states emerge through everyone having a right of secession.

China is doing this, and that will probably be the thing that actually lifts Africa out of poverty. The best way to improve the world is not to give money to charities (who have poor incentives and can only take a very limited category of actions) but to be an enthusiastic participant in the global economy.

I have even seen arguments that Bill Gates’ money would have done more good invested in developing economies than in all of his charity work. Seems plausible to me, especially given that I think some of his charity work (common core) is downright harmful, and I’ve heard from others working on the ground that their huge foundation is not very responsive to local needs.

I’m sure a lot of good has, nevertheless, been accomplished by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, but more good than if all that money had been invested in economic development of third world nations? I’m not so sure.

This is why the idea of micro-loans also really appeals to me. It’s not “charity,” so much as an invitation to the poor to join in the development that has already so greatly improved living standards around the world.

In practice, micro-loans are just a crappy version of cash transfers. The theoretical advantage is that they provide greater cost-efficiency because the money has to be repaid, but this doesn’t seem to pan out much of the time.

This was a major argument for the Iraq War. Still willing to argue for it?

People with guns setting up a more democratic polity is being done all over the place – haven’t you kept track of all the coups and current wars and insurrections?

“Private companies doing it” is also a thing – look at the contractors in Iraq, for example, or Mark Thatcher’s failed coup attempt.

The problem here is “the arts that win a crown must it maintain”. People, particularly private companies, who go into a country with guns and soldiers are doing it not out of the goodness of their hearts, but with “what’s in it for me?”

Which generally ends up with the strong military leader stuffing the new democratic government with his relatives and supporters and the state treasury ending up in Swiss bank accounts in his name for when the next strong military leader takes over.

Donating to violent action does happen. IIRC the IRA got funds from American donations.

Also, while I’m not so sure about sending money, foreign volunteers showing up to help a side in a civil war that matches their ideology is definitely something that happens. For example, Islamists going to join ISIS/the Mujaheddin, and various leftists going to help in the Spanish civil war.

(I never said that these are for causes I agreed with. For the record, I’m against Islamists and the IRA, and in favor of the Spanish Republicans (or at least they were much better than the alternative)).

NORAID were indeed a major source of funds for the Provos in the Troubles. It was a major policy priority of the British Government throughout the Troubles to shut off the flow of NORAID funds.

It won’t work because the “international community” would crush you. As it has done every other government which is not “democratic” according to its standards, which involve “will of the people”, and other modern concepts. This process is not fast, either; it tends to take years of posturing, sanctions, and subversion via various means. As a consequence, the country you were attempting to save becomes impoverished by sanctions. And unless you go full hermit kingdom ala North Korea, you get a rebellion of the best, brightest, and most power-hungry people, who naturally pick up the signals from the State Department that if only they’d rebel, they’d get support. “Responsibility to protect.” So you end up with a country that is impoverished, with a civil war. And also you personally end up like Saddam or Gaddafy. This is not effective.

Now, if the “international community” were to lose its power, then what you are talking about — colonialism — would work. So, maybe you can wait for it. Or maybe you can take the really long view, and work for the demise of the “international community”.

I see no sign of the international community attempting to crush Singapore or Malaysia, or Mexico during the PRI period, or Japan under the LDP; provided you have elections, you’re fine to direct disproportionate media coverage at the Teal Party and make strong explicit promises of withdrawing development funding from the precincts that voted Orange.

If you can’t manage a mandate using Lee Kwan Yew’s level of manipulation of the democratic process, you didn’t deserve it in the first place.

That’s as scary as it is true.

(With apologies to XKCD.)

SITUATION: There are 14 competing warlords and no functioning government.

CUEBALL: 14? Ridiculous! We should hire a mercenary army that’s good enough to establish hegemony, take over, clean the place up, and install a real democracy!

PONYTAIL: Yeah!

Soon:

SITUATION: There are 15 competing warlords and no functioning government.

Imperialism is probably a bad plan for anybody not willing to make a wasteland and call it peace.

The use of military force to overthrow an existing government, or to establish one, is a form of political activism, which as Scott pointed out is one of the least efficient forms of doing good for the world.

Even worse, it’s THE LEAST EFFICIENT FORM OF POLITICAL ACTIVISM. Military force is really, really good at killing lots of people and destroying lots of infrastructure, and really, really bad at producing stable, non-abusive, democratic governments, as demonstrated by basically every revolution ever.

Germany and Japan being the most obvious counterexamples, and I think too monumentally significant to be dismissed as outliers.

Though it may be significant that we did not “use military force” to overthrow their governments; we waged war against them. People who euphemize their warfighting are almost guaranteed to leave the job half-done, and that just leaves you with dead bodies and broken stuff. Acknowledging that you are waging war is I think a necessary but not significant condition for accomplishing anything really useful by the use of military force.

It has a bad reputation for historical reasons, but also there are knowledge problems involved: running a government in your own country is difficult enough, but it’s even worse when you’re unfamiliar with the local problems, customs, etc.

1. Charities are bad at binary things. It’s easy to start your malaria charity small, treat ten people, and then expand until you treat a million people. A violence charity would have to have a pretty strong army before it could do anything at all.

2. Relatively likely to start at least a small war, I don’t think people want that kind of blood on their hands. Most people donate to charity to feel good. Even if the war was won and the reconstruction successfully improved the country, that’s not exactly warm and fuzzy. And there’s no guarantee those two conditions would hold.

3. I think there are laws against a country supporting or tolerating any movement to invade another country it recognizes diplomatically. See this incident, which is probably closest to what you describe.

4. Everyone would hate you and the media would beat up on you nonstop.

1. You could presumably start by e.g. arranging ten mercenaries or volunteers to guard food distribution convoys on the fringes of a hostile warlord’s territory, and scale up from there if successful. Indeed, this has been done – the word “technical” for “pickup truck with a heavy machine gun or whatever” evolved from the creative accounting dodges various charitable groups in Somalia used when locally arranging such guards.

2. You could probably get people to feel good about this, at least on a small scale. Beating up on warlords who tyrannize the wretched is kind of a feel-good thing, particularly if you do it defensively. Though, as noted, charities in Somalia preferred to conceal their efforts in this area.

3. and 4. are definitely going to be problems if you try to scale this sort of thing up. If I had to try it, I’d want a rock-solid reputation as the Good Guys who guard food convoys and refugee camps, then carefully escalate to preemptive attacks on the military forces of the warlords who keep attacking the refugees. Eventually, hopefully, the warlord has no army and flees, and the charity is the de facto government. But I expect it would fail on the world stage even if it were tactically successful in the field, for the reasons you cite.

There’s also the danger of being co-opted and corrupted by people who would offer to finance a whole lot of food-convoy escorts and refugee-camp guards if you were to also guard their lucrative mines and plantations and associated shipping routes.

For myself, the answer is a lack of evidence. There’s just no way for me (or, if we’re being pessimistic, anyone) to know whether you’re making a positive difference at all. I would also worry about the incentives that might arise if regular donations to militaries became a common thing.

It was very popular in Northern Ireland for decades. And, by proxy, very popular in Glasgow, Scotland and Boston, USA, from what I hear.

This may explain why it’s no longer so popular.

I’m now having happy daydreams of a world where everyone needs to purchase an “activism license” by tithing to charity, as a prerequisite for doing any cost-free holiness signalling like hashtag activism. You could call it the “Put Up or Shut Up Act of 2015”.

I like this plan.

Insofar as such messages are predominant in one’s upbringing, I am having a hard time seeing how this does not constitute an emotionally abusive childhood. Certainly the effects on the recipient are the same:

For what it’s worth, I was raised in a very religious household that held a very similar belief: We are all worthless sinners, saved but by the grace of god. We will always be horrible people, but we have a moral obligation to try our absolute hardest to overcome.

I consider this to have been emotionally abusive. It fucked me up in the brain pretty good.

I don’t think “argument from emotional fragility” is particularly persuasive; would you respect the person arguing against teaching evolution on the reason that hearing that mankind is simply another animal and there is no eternal purpose to existence was emotional abuse and a brain fuck-up?

I had a broadly similar worldview taught growing up and consider myself more-or-less psychologically well adapted.

1. Evolution does not imply either of the things you mentioned.

2. If the message was that that mankind is simply another animal and there is no eternal purpose to existence and you must always feel horrible about that (accomplished by whatever rhetorical methods), then yes, I would consider it emotional abuse and a brain fuck-up.

3. If the mere fact that some people can come out of an experience “psychologically well adapted” means that emotional abuse did not take place, then nothing can qualify as emotional abuse.

4. Your argument would be considered “victim blaming” under the liberal ethos, as it attributes the problem to “emotional fragility” on the part of the sufferer. Either way the liberal ethos collapses on itself.