Aquinas famously said: beware the man of one book. I would add: beware the man of one study.

For example, take medical research. Suppose a certain drug is weakly effective against a certain disease. After a few years, a bunch of different research groups have gotten their hands on it and done all sorts of different studies. In the best case scenario the average study will find the true result – that it’s weakly effective.

But there will also be random noise caused by inevitable variation and by some of the experiments being better quality than others. In the end, we might expect something looking kind of like a bell curve. The peak will be at “weakly effective”, but there will be a few studies to either side. Something like this:

We see that the peak of the curve is somewhere to the right of neutral – ie weakly effective – and that there are about 15 studies that find this correct result.

But there are also about 5 studies that find that the drug is very good, and 5 studies missing the sign entirely and finding that the drug is actively bad. There’s even 1 study finding that the drug is very bad, maybe seriously dangerous.

This is before we get into fraud or statistical malpractice. I’m saying this is what’s going to happen just by normal variation in experimental design. As we increase experimental rigor, the bell curve might get squashed horizontally, but there will still be a bell curve.

In practice it’s worse than this, because this is assuming everyone is investigating exactly the same question.

Suppose that the graph is titled “Effectiveness Of This Drug In Treating Bipolar Disorder”.

But maybe the drug is more effective in bipolar i than in bipolar ii (Depakote, for example)

Or maybe the drug is very effective against bipolar mania, but much less effective against bipolar depression (Depakote again).

Or maybe the drug is a good acute antimanic agent, but less effective at maintenance treatment (let’s stick with Depakote).

If you have a graph titled “Effectiveness Of Depakote In Treating Bipolar Disorder” plotting studies from “Very Bad” to “Very Good” – and you stick all the studies – maintenence, manic, depressive, bipolar i, bipolar ii – on the graph, then you’re going to end running the gamut from “very bad” to “very good” even before you factor in noise and even before even before you factor in bias and poor experimental design.

So here’s why you should beware the man of one study.

If you go to your better class of alternative medicine websites, they don’t tell you “Studies are a logocentric phallocentric tool of Western medicine and the Big Pharma conspiracy.”

They tell you “medical science has proved that this drug is terrible, but ignorant doctors are pushing it on you anyway. Look, here’s a study by a reputable institution proving that the drug is not only ineffective, but harmful.”

And the study will exist, and the authors will be prestigious scientists, and it will probably be about as rigorous and well-done as any other study.

And then a lot of people raised on the idea that some things have Evidence and other things have No Evidence think holy s**t, they’re right!

On the other hand, your doctor isn’t going to a sketchy alternative medicine website. She’s examining the entire literature and extracting careful and well-informed conclusions from…

Haha, just kidding. She’s going to a luncheon at a really nice restaurant sponsored by a pharmaceutical company, which assures her that they would never take advantage of such an opportunity to shill their drug, they just want to raise awareness of the latest study. And the latest study shows that their drug is great! Super great! And your doctor nods along, because the authors of the study are prestigious scientists, and it’s about as rigorous and well-done as any other study.

But obviously the pharmaceutical company has selected one of the studies from the “very good” end of the bell curve.

And I called this “Beware The Man of One Study”, but it’s easy to see that in the little diagram there are like three or four studies showing that the drug is “very good”, so if your doctor is a little skeptical, the pharmaceutical company can say “You are right to be skeptical, one study doesn’t prove anything, but look – here’s another group that finds the same thing, here’s yet another group that finds the same thing, and here’s a replication that confirms both of them.”

And even though it looks like in our example the sketchy alternative medicine website only has one “very bad” study to go off of, they could easily supplement it with a bunch of merely “bad” studies. Or they could add all of those studies about slightly different things. Depakote is ineffective at treating bipolar depression. Depakote is ineffective at maintenance bipolar therapy. Depakote is ineffective at bipolar ii.

So just sum it up as “Smith et al 1987 found the drug ineffective, yet doctors continue to prescribe it anyway”. Even if you hunt down the original study (which no one does), Smith et al won’t say specifically “Do remember that this study is only looking at bipolar maintenance, which is a different topic from bipolar acute antimanic treatment, and we’re not saying anything about that.” It will just be titled something like “Depakote fails to separate from placebo in six month trial of 91 patients” and trust that the responsible professionals reading it are well aware of the difference between acute and maintenance treatments (hahahahaha).

So it’s not so much “beware the man of one study” as “beware the man of any number of studies less than a relatively complete and not-cherry-picked survey of the research”.

II.

I think medical science is still pretty healthy, and that the consensus of doctors and researchers is more-or-less right on most controversial medical issues.

(it’s the uncontroversial ones you have to worry about)

Politics doesn’t have this protection.

Like, take the minimum wage question (please). We all know about the Krueger and Card study in New Jersey that found no evidence that high minimum wages hurt the economy. We probably also know the counterclaims that it was completely debunked as despicable dishonest statistical malpractice. Maybe some of us know Card and Krueger wrote a pretty convincing rebuttal of those claims. Or that a bunch of large and methodologically advanced studies have come out since then, some finding no effect like Dube, others finding strong effects like Rubinstein and Wither. These are just examples; there are at least dozens and probably hundreds of studies on both sides.

But we can solve this with meta-analyses and systemtic reviews, right?

Depends which one you want. Do you go with this meta-analysis of fourteen studies that shows that any presumed negative effect of high minimum wages is likely publication bias? With this meta-analysis of sixty-four studies that finds the same thing and discovers no effect of minimum wage after correcting for the problem? Or how about this meta-analysis of fifty-five countries that does find effects in most of them? Maybe you prefer this systematic review of a hundred or so studies that finds strong and consistent effects?

Can we trust news sources, think tanks, econblogs, and other institutions to sum up the state of the evidence?

CNN claims that 85% of credible studies have shown the minimum wage causes job loss. But raisetheminimumwage.com declares that “two decades of rigorous economic research have found that raising the minimum wage does not result in job loss…researchers and businesses alike agree today that the weight of the evidence shows no reduction in employment resulting from minimum wage increases.” Modeled Behavior says “the majority of the new minimum wage research supports the hypothesis that the minimum wage increases unemployment.” The Center for Budget and Policy Priorities says “The common claim that raising the minimum wage reduces employment for low-wage workers is one of the most extensively studied issues in empirical economics. The weight of the evidence is that such impacts are small to none.”

Okay, fine. What about economists? They seem like experts. What do they think?

Well, five hundred economists signed a letter to policy makers saying that the science of economics shows increasing the minimum wage would be a bad idea. That sounds like a promising consensus…

..except that six hundred economists signed a letter to policy makers saying that the science of economics shows increasing the minimum wage would be a good idea. (h/t Greg Mankiw)

Fine then. Let’s do a formal survey of economists. Now what?

raisetheminimumwage.com, an unbiased source if ever there was one, confidently tells us that “indicative is a 2013 survey by the University of Chicago’s Booth School of Business in which leading economists agreed by a nearly 4 to 1 margin that the benefits of raising and indexing the minimum wage outweigh the costs.”

But the Employment Policies Institute, which sounds like it’s trying way too hard to sound like an unbiased source, tells us that “Over 73 percent of AEA labor economists believe that a significant increase will lead to employment losses and 68 percent think these employment losses fall disproportionately on the least skilled. Only 6 percent feel that minimum wage hikes are an efficient way to alleviate poverty.”

So the whole thing is fiendishly complicated. But unless you look very very hard, you will never know that.

If you are a conservative, what you will find on the sites you trust will be something like this:

Economic theory has always shown that minimum wage increases decrease employment, but the Left has never been willing to accept this basic fact. In 1992, they trumpeted a single study by Card and Krueger that purported to show no negative effects from a minimum wage increase. This study was immediately debunked and found to be based on statistical malpractice and “massaging the numbers”. Since then, dozens of studies have come out confirming what we knew all along – that a high minimum wage is economic suicide. Systematic reviews and meta-analyses (Neumark 2006, Boockman 2010) consistently show that an overwhelming majority of the research agrees on this fact – as do 73% of economists. That’s why five hundred top economists recently signed a letter urging policy makers not to buy into discredited liberal minimum wage theories. Instead of listening to starry-eyed liberal woo, listen to the empirical evidence and an overwhelming majority of economists and oppose a raise in the minimum wage.

And if you are a leftist, what you will find on the sites you trust will be something like this:

People used to believe that the minimum wage decreased unemployment. But Card and Krueger’s famous 1992 study exploded that conventional wisdom. Since then, the results have been replicated over fifty times, and further meta-analyses (Card and Krueger 1995, Dube 2010) have found no evidence of any effect. Leading economists agree by a 4 to 1 margin that the benefits of raising the minimum wage outweigh the costs, and that’s why more than 600 of them have signed a petition telling the government to do exactly that. Instead of listening to conservative scare tactics based on long-debunked theories, listen to the empirical evidence and the overwhelming majority of economists and support a raise in the minimum wage.

Go ahead. Google the issue and see what stuff comes up. If it doesn’t quite match what I said above, it’s usually because they can’t even muster that level of scholarship. Half the sites just cite Card and Krueger and call it a day!

These sites with their long lists of studies and experts are super convincing. And half of them are wrong.

At some point in their education, most smart people usually learn not to credit arguments from authority. If someone says “Believe me about the minimum wage because I seem like a trustworthy guy,” most of them will have at least one neuron in their head that says “I should ask for some evidence”. If they’re really smart, they’ll use the magic words “peer-reviewed experimental studies.”

But I worry that most smart people have not learned that a list of dozens of studies, several meta-analyses, hundreds of experts, and expert surveys showing almost all academics support your thesis – can still be bullshit.

Which is too bad, because that’s exactly what people who want to bamboozle an educated audience are going to use.

III.

I do not want to preach radical skepticism.

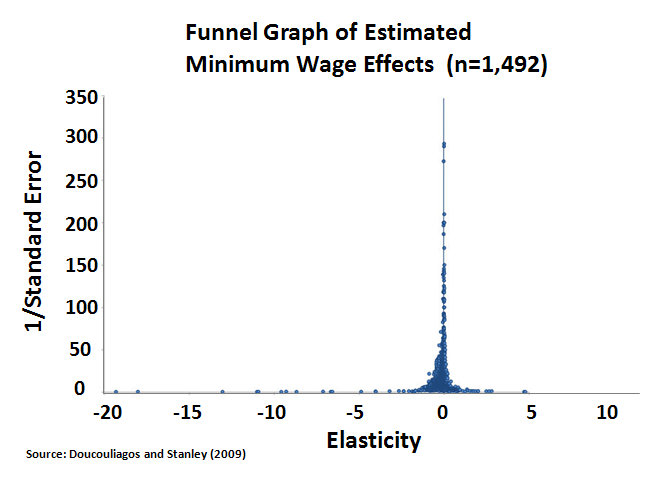

For example, on the minimum wage issue, I notice only one side has presented a funnel plot. A funnel plot is usually used to investigate publication bias, but it has another use as well – it’s pretty much an exact presentation of the “bell curve” we talked about above.

This is more of a needle curve than a bell curve, but the point still stands. We see it’s centered around 0, which means there’s some evidence that’s the real signal among all this noise. The bell skews more to left than to the right, which means more studies have found negative effects of the minimum wage than positive effects of the minimum wage. But since the bell curve is asymmetrical, we intepret that as probably publication bias. So all in all, I think there’s at least some evidence that the liberals are right on this one.

Unless, of course, someone has realized that I’ve wised up to the studies and meta-analyses and and expert surveys, and figured out a way to hack funnel plots, which I am totally not ruling out.

(okay, I kind of want to preach radical skepticism)

Also, I should probably mention that it’s much more complicated than one side being right, and that the minimum wage probably works differently depending on what industry you’re talking about, whether it’s state wage or federal wage, whether it’s a recession or a boom, whether we’re talking about increasing from $5 to $6 or from $20 to $30, etc, etc, etc. There are eleven studies on that plot showing an effect even worse than -5, and very possibly they are all accurate for whatever subproblem they have chosen to study – much like the example with Depakote where it might an effective antimanic but a terrible antidepressant.

(radical skepticism actually sounds a lot better than figuring this all out).

IV.

But the question remains: what happens when (like in most cases) you don’t have a funnel plot?

I don’t have a good positive answer. I do have several good negative answers.

Decrease your confidence about most things if you’re not sure that you’ve investigated every piece of evidence.

Do not trust websites which are obviously biased (eg Free Republic, Daily Kos, Dr. Oz) when they tell you they’re going to give you “the state of the evidence” on a certain issue, even if the evidence seems very stately indeed. This goes double for any site that contains a list of “myths and facts about X”, quadruple for any site that uses phrases like “ingroup member uses actual FACTS to DEMOLISH the outgroup’s lies about Y”, and octuple for RationalWiki.

Most important, even if someone gives you what seems like overwhelming evidence in favor of a certain point of view, don’t trust it until you’ve done a simple Google search to see if the opposite side has equally overwhelming evidence.

This essay seems to be suggesting that no matter how many studies you have, you cannot use them to figure out much of anything. How does this jibe with your article on race and justice in which you try to use studies to determine whether the justice system mistreats blacks? Aren’t you saying here that what you tried to do a few weeks ago is a fool’s errand?

Pingback: “Beware The Man of One Study” * The New World

Pingback: Beware The Man Of One Study | Slate Star Codex « Economics Info

Pingback: On examining evidences for points of view, etc | The Daily Pochemuchka

Pingback: Links for December 2014 - foreXiv

Scott, I meant to comment on this earlier, but I’m way behind on everything.

First of all, let me say very good post. This:

…is solid gold!

Other very good points in here, like:

Now, those said, you do indeed seem to preach from a point of adamant skeptical neutrality – indeed, radical skeptical neutrality. That’s not the best approach to take, and frankly isn’t really true skepticism.

Let me illustrate the problem. You say:

Here’s the problem: if you don’t understand a matter well enough to look at the evidence and come to a conclusion yourself, you’re screwed. There is no strategy, no system, no method you can use to ascertain truth with contradictory results when you, ultimately, have to rely on “experts.” End of story. If I can’t look at a matter and come to my own conclusions, I don’t form an opinion.

Proper skepticism isn’t just being critical of claims on a matter, but being able to methodologically examine the evidence to get towards the correct conclusion. Indeed, this is integral to good science.

Those said, again, good post. That funnel plot was rather telling (I love funnel plots), if not definitive thanks to methodological issues. Nonetheless, still telling.

Pingback: A week of links | EVOLVING ECONOMICS

Pingback: The Liberty Herald – Potpourri

Pingback: Potpourri

Pingback: 10 Tuesday PM Reads | The Big Picture

The margins on many studies are too small to show much of anything. Minimum wages at the currently proposed levels being a good example. So on minimum wage I think that we all would agree that raising it to $30/hour would increase unemployment, fuel an increase in the black market for low skilled labor and drive many very low margin businesses into bankruptcy. So does the dose make the poison or can we interpolate from that, that smaller changes in he minim wage probably increase unemployment?

> These sites with their long lists of studies and experts are super convincing. And half of them are wrong.

More than half of them are wrong, since many of them on the right side will have incorrect reasons for reaching their conclusions!

Pingback: Quotes & Links #22 | Seeing Beyond The Absurd

Two points on the minimum wage issue:

1. One of the authors of Card and Krueger, in an interview, commented that the study was for a small increase and he wouldn’t expect the result to hold for a large one. That’s some evidence on one side, given what Obama is proposing. On the other hand, in the same interview, he described the hostility he got from colleagues for the article, which is some evidence for the other side, since it suggests that studies which go against the dominant view in the field are less likely to get published. (To reveal my own bias as one member of the field, I am confident that raising the minimum wage reduces unemployment for unskilled workers, although I have no strong view on the size of the effect. My guess, polls aside, is that most serious economists, people who view economics as a way of making sense of the world rather than a fun game, would agree. It comes down to expecting the demand curve for unskilled labor to slope the same way as all other demand curves for inputs.)

2. A lot of the discussion confuses the issue by talking about the unemployment rate rather than the unemployment rate for unskilled workers—more precisely, workers who are now making less than the proposed minimum wage. Minimum wage workers are a very small part of the labor force, so even a substantial change in their unemployment rate has an almost unobservably small effect on the national unemployment rate. Anyone who tells you “state X raised its minimum wage and the unemployment rate went up instead of down” with the implication that that’s relevant evidence is either a fool or a rogue. Ditto in the other direction.

. (To reveal my own bias as one member of the field, I am confident that raising the minimum wage reduces unemployment for unskilled workers, although I have no strong view on the size of the effect.

I’m almost certain you typed the opposite of what you meant there. (Should read employment, not unemployment. Or possibly increases instead of reduces.)

Oops. That should have been “reduces employment.”

When two sincere opponents get locked into such a stalemate I would suggest that they might just be asking the wrong question.

The question is not “do small increases in the minimum wage harm employment for lower skilled workers?” It is “do small increases in the minimum wage distort the labor market?”

As a business person I would be surprised if small changes had a measurable effect on unemployment for the following reasons:

1) only a small percentage of workers are earning minimum wage and only a small percentage of the currently unemployed are seeking minimum wage jobs. This latter fact is critical as a higher minimum wage will change the distribution of unemployed toward the unskilled as higher skilled workers now find it easier to find a job. The net effect is to skew the employability toward higher skills.

2) minimum wage does not directly translate into higher total employment costs. As profiled in the comments above, hourly wage is only a component of total compensation. There is also training, uniforms, breaks, benefits, discounts on purchases and so forth. A business will logically cut these to the detriment of the employee. Total compensation costs (and hence total employee rewards) therefore do not necessarily increase with minimum wage.

3). Labor is a contract with two variables. The wage can change, but so too can expectations to get or keep the job. At a higher compensation cost (assuming no other compensation factors adjust as in the prior point) the employer can just change the demands placed upon the employee. Less absence or tardiness, more burgers flipped per hour, etc. In other words, the employer can respond by being more of a hard ass. The cost/benefit of higher job demands has changed again to the detriment of the employee and the employer.

4). Minimum wage raises the price of an hour of employment, not the cost per employee. The logical short term response of a part-time employer is not to reduce workers. It is to reduce hours per worker. This still counts as employment, but does not lead to higher total wages. Note that the reason employers don’t have larger pools of part time workers is greatly because the workers are competing with each other for more hours. The increase in the minimum wage reduces this bargaining chip for employees. The net effect of a minimum wage hike would be fewer hours worked on average for a wider pool of part timers. You could also see relative shifts as better workers get more hours and lower skilled or problem employees get less.

5). Employment costs are only one component of the production costs. As this component rises, there are other areas which an employer can adjust. For example, it may make sense now to reduce how often the building is painted, or how good of a landscaping service is used. Or it may make sense to increase the pace of roll out for the new automation which replaces burger flippers.

6). If all the above fail, the employers can scrape by on lower margins. This reduces incentives for new employers, new branches, new competitors in the industry, but would take place over years. Possibly even a decade or more and would be completely opaque to any employment statistics.

In summary, the effects of a higher minimum wage would be expected to be broad based and multi-faceted. The labor market would be clearly distorted, but only one small fraction and quite possibly none of this distortion would show up as less employment.

For an economic study to focus only on the employment effects is perplexing to say the least. I would assume they have talked to businesses to see how they would actually react…no?*

Yet for some reason the debate continues along this one dimension.

*yes I am aware of the studies which track these other effects.

Pingback: Weekly review: Week ending December 12, 2014 - sacha chua :: living an awesome life

Not relevant to the argument, but: I think you are misinterpreting Aquinas. I always understood the quote to mean (and the Wikipedia page you link to backs me up) that somebody who has thoroughly mastered a single book is very formidable. (As opposed to superficial knowledge of many books.)

I must admit I haven’t looked (this isn’t a subject that really bothers me greatly either way (even if that might be surprising to anyone who knows my political ideology; but it’s true)), but I wonder if there have been studies about minimum wage not affecting employment, but the wages of the ‘middle-class’.

As in, the idea that people will not hire any less people, but they will take the money they’re paying to the jobs that they were previously paying less than minimum wage to from the people who were just above the minimum wage.

Differently stated (numbers used have been pulled entirely out of thin air): If person A makes 1$/hour and person B makes 3$/hour and the minimum wage were instated/raised to 2$/hour, would person A and person B both make 2$/hour afterwards? Have there been studies on that? I imagine so, I just find myself curious, since it seems to be entirely absent from the narrative in the media that I’ve encountered, which keeps harping on the unemployment topic.

(For the record, even if there were such an effect, I think arguments about such an effect can be made both ways.)

I can’t give you studies directly on that, as I’m not aware of them.

I can’t think of any economic theory that would lead to that though. The negotiating power of person B hasn’t changed, and their marginal value hasn’t fallen (unless they were just managing a group of As now being made redundant). There would be no reason to expect the market wage for their type of work to fall much, and if a company cut their wages anyway, it could expect them to up sticks for greener pastures.

What I’d expect to see instead is companies that are structured around employing lots of person A type people struggling, and companies that are structured around employing lots of person B types taking advantage.

For example, Costco pays something like $11/hr + benefits, employs people who have valuable skills (personable, self reliant, strong work-ethic, etc) and competes on customer experience and product quality wants the minimum wage to go up, while Wal-Mart pays something like $8/hr + all the out-of-work disrespect you can tolerate, employs people who couldn’t get jobs at Costco (introverted, physically handicapped, uneducated, criminal records, etc) and competes on price and accessibility (more locations open more hours) would suffer from the minimum wage.

Unsurprisingly, Costco is a proponent of raising the minimum wage, because that makes Wal-Mart’s business model less efficient but doesn’t hurt Costco.

I think it’s interesting that after all of that you still manage to believe that liberals are probably right on this issue even though your reason is that “it’s probably publication bias”. If you were a conservative, would you find that convincing?

I’m not as leftist as you think and probably more against the minimum wage than in favor. See also here

Nice post.

“But I worry that most smart people have not learned that a list of dozens of studies, several meta-analyses, hundreds of experts, and expert surveys showing almost all academics support your thesis – can still be bullshit.

Which is too bad, because that’s exactly what people who want to bamboozle an educated audience are going to use.”

You should read http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Propaganda:_The_Formation_of_Men%27s_Attitudes , among all the other insights it offers, the author rather thoroughly destroys the notion that education is of any use when it comes to resisting propaganda.

If I know that I haven’t done the research, should I decrease my confidence in “The minimum wage has a significant positive overall economic effect”, “… negative overall…”, or “has no significant overall…”?

If you haven’t heard about p-curve, see:

http://psycnet.apa.org/journals/xge/143/2/534/

http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/Papers.cfm?abstract_id=2377290

When publication bias results from selective reporting of studies based on significance, funnel plot methods (trim and fill) aren’t adequate.

Not everyone who uses funnel plots uses trim and fill. In particular, this post did not. Funnel plots subsume the p-curve.

Your first link is broken. The correct link is here.

I’m on the side of minimal effects of current US minimum wage, mainly due to my experience with sabermetrics in baseball. The rest of this post assumes basic baseball knowledge, but I think it’s a useful example of how some of this stuff works in practice.

Probably the biggest gap between baseball intuition and the sabermetric consenus was DIPS (Defense Independent Pitching Stats). Voros McCracken had the bright idea to try and measure only the things pitchers had control over and the defense had no control over (Ks, BBs, and HRs), to help disentangle pitcher performance from fielder performance. He ended up discovering that this measure was not just more predictive of future performance than measuring the total runs allowed by a pitcher, but that the leftover result (BABIP, batting average on balls in play) was effectively random, and had no correlation on a year to year basis. Everyone who has ever played baseball knew that pitchers had control over how hard the batter hit the ball, so they generally totally rejected the findings despite the overwhelming empirical evidence.

The solution to the paradox was mostly selection effects: first, pitchers that were not very good at preventing batters from hitting the ball well never make it to the majors. Second, when a Major League Baseball player gets a “bad” pitch in modern baseball, they tend to hit it out of the ballpark, so it’s no longer a ball in play. The current US minimum wage is similarly highly selected, given that it’s set below the prevailing wage for unskilled labor. In a world where nobody employed at Wal-Mart makes minimum wage, people who make the minimum wage are really weird. The exceptions are teenagers, and minimum wage increases affect teenage employment in the expected way. For people who are that weird, if it’s a result of antisocial behavior or total inability to follow directions, they aren’t worth employing for free (analagous to the HRs that end up out of the sample). So you end up with empirical results that contradict the general theory.

Why are effect sizes in medicine often so small?

Human body is massively complex system where any given change is overwhelmed by intricate, overlapping feedbacks?

Different genetic/metabolic signatures between different humans would predict larger effect sizes for certain individuals – but studies don’t/can’t segregate people into these groups, so what would be a large effect size in a specific set of 100 people becomes a tiny effect in a randomly selected set of 100 people?

Why, why, why?

Could also be that it’s hard to find compounds that have large desired effects but not large undesired (side)effects.

/not an expert

How would you fix this?

Like, suppose I know that of every 100 people with depression, 50 get better by chance/placebo per year.

I get 100 people and I give them Paxil. 60 get better. I do my tests and find it’s statistically significant with a small effect size.

Now what do I do?

If we knew for sure what dimension responders vs. non-responders varied upon, that’d be one thing. Until then, as best I can tell all we can do is say “100% of all responders respond!”

Chasing down the characteristics of responders vs. nonresponders is almost never a good use of your time. If you’re doing genetics, you’ll get a zillion false hits and no true ones. If you’re doing metabolomics, you’ll get a zillion things that make a tiny amount of difference and nothing useful.

Don’t forget to distinguish employment levels from unemployment levels – those two measures can vary independently. Expect people to select whichever measure produces evidence they like.

Besides the publication bias, another interesting thing this funnel plot shows is systematic vs random error, or to use a more LWy term, ‘confidence levels inside and outside an argument’: does anyone actually believe that the real causal effect of minimum wage might be an elasticity of -20? Or that it’s remotely correct to note that 3 studies or so have a precision of ~1/300 and interpret this as giving a correct measurement of the genuine correlation (much less causation)? Past 1/50 or so in precision and 1 in elasticity, I suspect random error is going to be negligible and all the results driven by systematic biases & errors in the underlying data & analyses.

(I suspect a ‘credibility ceiling’ approach, as ad hoc as I find it, would produce better results; for an explanation of the idea, which is basically just specifying some estimates for systematic error and capping influence of individual studies at the point where they’re primarily systematic error, see “Synthesis of observational studies should consider credibility ceilings”, Salanti & Ioannidis 2009 and an example application, “Application of credibility ceilings probes the robustness of meta-analyses of biomarkers and cancer risks”, Papatheodorou et al 2014; eyeballing it, I would guess that reasonable credibility ceilings would drain the influence of the >1/50 studies and produce a point-estimate somewhere 0 to -1 – which is not a definitive answer since a small shift like that is ascribable to publication bias and other highly plausible issues (seriously, -20‽) but at least is a sensible answer.)

I believe you made a sign error when you said that leftists would say:

“People used to believe that the minimum wage decreased unemployment.”

You probably wanted to say:

“People used to believe that the minimum wage decreased employment.”

When the empirical evidence is so mixed, one can sometimes turn to theory. Minimum wage is about as close as you can get in economics to a simple question answered by the most basic microeconomic models which while not always right in more complex settings are almost certainly right here. Namely, if you increase the price of something (low end labor), people will buy less of it. There are rare exceptions (positional goods) but unskilled labor does not at all resemble them.

So there is a very strong reason to expect a very small but very definitely negative effect on employment of the least skilled workers. Generally these are young, poor, and uneducated, exactly those most vulnerable. This is a short-term effect and you can argue there are beneficial long run effects, which is not ruled out by this model, although the evidence is for negative long run effects too

Given the effect should be tiny, the studies should cluster around zero. The larger the hike and the more the study focuses on the tiny population of people who work for minimum wage,the more accurate it should be.

Why does theory say that the effect should be tiny? Don’t the authors of these dozens of studies disagree with that expectation?

The effect should be small and hard to tease out if the change in the wage is small and gradual, as it usually is. The main US counterexample I can think of is in 2007 when we tried to ramp up wages in American Samoa and the Mariana Islands to US levels. (That minimum wage change killed entire industries and had to be put on hold.) But usually each individual minwage change is small on a percentage basis and phased in gradually, so its effect is small too.

Patri,

The controversy bears a certain resemblance to the marginalist controversy of the early-middle of the previous century. See https://www.princeton.edu/~tleonard/papers/minimum_wage.pdf. What can falsify an economic theory? Note the James Buchanan quote on page 21. In the case of the marginalists they were right to be skeptical of the prima facie interpretation of the survey evidence that firms are not profit-maximizers. Frank Knight taught of the inverse relationship between choice and competition, and in the end the marginalists were probably right to dismiss the opinions of the business owners as mostly irrelevant. Milton Friedman and Paul Samuelson found some common ground here.

Let me push back against the idea that we must turn from evidence to theory. Perhaps the discussion is too parochial. The economic theory of the effects of price floors has far more evidence for it than specifically studies on the effects of the minimum wage. Given that, how mixed is the evidence really? It must be asked why we would think labor might be an exception, and if it is an exception, surely there must be others. Presumably welfare-improving opportunities for price floors must exist in many industries if we are to take this argument very seriously.

The debate around the economic effects of the minimum wage is like cutting at a single scale on Leviathan’s back. Whether it is in fact loose enough that it may be torn off the main body is a question, but the reason for doubting it has to do with the strength of the great sea monster’s entire corpus. It would take a very sharp knife indeed to injure it, as we have seen time and time again. So we do not turn from evidence to theory at all but instead ask how strong this new evidence really is, that it should demand the attention of the great sea beast.

Reasons for skepticism that do not seem sufficiently discussed to me are the questions of how predictable and periodic these minimum wage increases are, and what role the minimum wage itself might play in promoting monopsony. Part of the value of this sort of research is that it has tended to incline economists away from treating economics as the study of choice and instead as the study of the optimizing pressures that scarcity imposes on some given system. The resulting insights are some of the reasons Knight, Alchian, and Becker are so highly regarded, to name just a few. Yet that the minimum wage should make its own demands on the industry seems to be an underrated insight. Market forces will tend to minimize the negative impact of the minimum wage over time (internships are an obvious example, as are selection effects producing monopsonistic firms), and so the clearest study of “the” effects of the minimum wage would be a surprising and unprecedented minimum wage the industry is not prepared for. Then you might see some unemployment, I suspect. It will probably be difficult to find such a thing in a democratic society where policy is made slowly. I do not know much about the impositions or effects of minimum wages in more dictatorial countries, but I would be more persuaded if minimum wages in such countries also seemed to have little to no unemployment effect.

While I am skeptical of the conclusions both the anti-marginalists and the skeptics of the unemployment effects of the minimum wage advocates wish to draw, it is unfortunate that no one seems to want to discuss the importance of the effort that goes in to these studies and the quality attitude they require. The anti-marginalists or those who became them had the brilliant idea of calling up businesses and asking them how they set prices. Card and Krueger’s criticisms of econometric malpractice have been largely ignored relative to the perhaps less interesting question of the effects of the minimum wage, although this may be because no one has any very major disagreements. I would say the same of real business cycle theory–it reflects an important effort and a sound attitude, regardless of the theory’s ultimate veracity.

I do also see value in these sorts of efforts in that they probably do function to dispel the impressions economists form that may not be quite implied by their theories but nevertheless probably tend to manifest themselves in the human mind. That is, economists are forced to adjust to these data, and usually for the better. Economists learned from the marginalist controversy, and they will learn from the minimum wage controversy as well. These things have significant value, but people do tend to get a bit too excited about them.

“Part of the value of this sort of research is that it has tended to incline economists away from treating economics as the study of choice and instead as the study of the optimizing pressures that scarcity imposes on some given system.”

Thanks for the new crystalized concept!

Something I’ve found to be an effective way of learning about these kinds of econ/policy questions is by stalking smart people on Reddit. There are a handful of people that commentate on reddit.com/r/badeconomics, as well as holding good economics discussion in the r/economics sub (one of them is a moderator). They routinely post papers, technical blog discussions, etc. Several of them are economics professors in universities (though, they like to keep their anonymity and won’t divulge where).

On the question of minimum wage specifically, here is my (layman’s) attempt at summary of their consensus on the minimum wage discussion (source: discussion at reddit.com/r/economics and reddit.com/r/badeconomics)

* The labour market has unique frictions that make a naieve supply and demand model inapplicable.

* Specifically, the minimum wage labour market appears to function somewhat as a monopsony, with one buyer (the employer) buying many employees. This seems to largely stem from mobility issues amongst the workers; They are too poor to move somewhere else, commute farther for work, etc., and so their employers can exercise wage suppression power on them.

* Minimum wage may be an acceptable way of addressing this problem, but it’s known to be a rather weak solution. In terms of an anti-poverty measure, minimum wage only helps the subset of the poor who can pull it together enough to pass a job interview; this largely locks out the worst off folks.

* Especially given that the monopsony power of minimum wage employers comes from lack of options and lack of mobility, more effective long term solutions would involve things that break this hold directly. Increased access to inexpensive transportation, increased ability to move in search of new work, additional options for minimum wage employment. Either in-kind provision or subsudies, both would be effective in the long term.

* In the short term, moderate minimum wage increases (+ pegged to inflation) are probably a good partial solution.

* Small to moderate minimum wage increases likely do not have significant effects on employment or inflation. Large minimum wage increases likely do, and they will likely cause other disruptive shocks.

* Minimum wage increases preferentially shift employment from small companies to large companies in the long term; McDonalds is more able to absorb a cost increase than the mom&pop down the street. This may or may not be a bad thing for overall welfare.

”

* Specifically, the minimum wage labour market appears to function somewhat as a monopsony, with one buyer (the employer) buying many employees. This seems to largely stem from mobility issues amongst the workers; They are too poor to move somewhere else, commute farther for work, etc., and so their employers can exercise wage suppression power on them. ”

Monopsony? Really? So real wages don’t increase in the absence of the minimum wage?

I guess that the minimum wage didn’t have to be continually raised because real wages were increasing then and that real wages were flat prior to the introduction of the minimum wage… oh wait, neither of those are true.

Wages are only monopsony in company towns and isolated small towns (and for the latter only in the short run).

This is absolutely false, and typical of the whack-a-mole that needs to be played. There are huge numbers of firms hiring at the minimum wage, and minimum wage employees are the most likely of any employees to quit their job to take a new one. There is a complete absence of data to suggest monopsony, and a huge amount of data to suggest a very competitive marketplace. Above, we even have a (pro minimum wage) commenter saying that of course no-one is so foolish as to argue for a monopsony model to justify the minimum wage… yet here we are.

1. each reddit has a particular majority point of view (by self-association / upvote-seeking). it would be a mistake to characterize the consensus of a reddit (in favor of minimum wage increase) as the consensus of an academic field (which I assume is closer to the opposite)

2. fakers on reddit are pretty common – wouldn’t trust “I’m an anonymous professor”

This also leads me to a related conclusion: progressives and liberals love empirical data with counter-intuitive conclusions, because it gives them a chance to relive the smug superiority they feel with respect to intelligent design in the same way they love to discover a new oppressed group (or a new way of conceiving of oppression, such as “micro-aggression”), as it allows them to relive the glories of the civil rights era.

Therefore, if you can say, “it may seem like minimum wage would increase unemployment, but actually many scientific studies have shown this to be false,” or even, “it may seem like minimum wage would increase unemployment, but in certain cases it’s been empirically shown to LOWER unemployment” (I have seen this claim, btw), then that is great on TWO counts, because, not only do you get empirical support for something you wanted to do anyway, but you also get to look down on all the neanderthals who refuse to accept the scientific consensus just because of their dumb intuitions about “common sense.”

Hope the above didn’t come off as too snarky; I am just so sick of my Facebook feed being full of people proudly, “bravely” coming out against: hating gay people, raping, not vaccinating your children, intelligent design, and, of course, “stupid conservatives who just don’t understand the economy,” even though I’m pretty sure virtually nobody on my friend list, or even on most of my friends’ friend lists actually believes in intelligent design, hating gay people, raping, anti-vax, etc. and even though I’m sure 99% of the people complaining about the stupidity of conservatives, or, if they’re more sophisticated, “neo-liberal economics,” are not as smart as Milton Friedman, to put it charitably.

I am just so sick of my Facebook feed being full of people proudly, “bravely” coming out against: hating gay people, raping, not vaccinating your children, intelligent design, and, of course, “stupid conservatives who just don’t understand the economy,”

It sounds like you are complaining about people using facebook for its intended function.

So the intended function is to provide a platform for people to signal to their friends how enlightened they are by attacking boo lights and coming out in favor of applause lights? I’m not saying you’re wrong, but… how depressing?

In the interest of fairness, I should also note one of my own tribe’s biases–a bias I tend to share–which is to be contrarian:

http://bleedingheartlibertarians.com/2014/10/the-contrarian-trap-the-source-of-the-liberty-movements-dark-side/

We are much more likely than average, for example, to be into Crossfit or the Paleo diet, which are sort of contrarian views on fitness and nutrition, respectively.

“So the intended function is to provide a platform for people to signal to their friends how enlightened they are by attacking boo lights and coming out in favor of applause lights?”

Almost, or rather, too much:

“So the intended function is to provide a platform for people to signal [things, mostly positive] to their friends”

Certain people do it the way you mention, some do it by talking about their personal achievements, others like to talk about how cute their grandchildren/pets are.

I think you succeeded in depressing me further by making me realize that what I thought I hated about Facebook is actually something I hate about people in general: not that they like to signal positive things about themselves, but that it’s incredibly difficult to have a dispassionate discussion about controversial or consequential topics while maintaining amicability and without shifting into “arguments are soldiers” mode.

In this respect Facebook is like a giant party: most of what is said is innocuous and pleasant; sometimes somebody brings up politics, religion, or philosophy and either is met with pats on the back because everyone agrees, or else tempers start to flare and someone adroitly changes the subject.

What very, very rarely happens (in my experience, at least–in real life, and on Facebook), is that someone expresses a dissenting opinion and then people thoroughly and deeply explore various arguments without anyone’s feelings getting hurt.

What usually seems to happen is either people get really pissed off, or, much more likely, just kind of clam up, change the subject, say, “oh, politics, you know…” etc. which is always the point when I was getting really interested.

Then I can go back to looking at pictures of people’s grandkids and hearing about how anti-rape they are.

but that it’s incredibly difficult to have a dispassionate discussion about controversial or consequential topics while maintaining amicability

That is is, but . . . with regards to facebook, most of the “friends” who I disagree with about anything substantial are not capable of any sort of discussion that involves critical thought . . . the best I can do is expose them to information they would not have come across on their own.

You know, it’s issues like these that have made me default to just ignoring most empirical social science work (as I don’t have the time nor inclination to investigate every claim I see), and being much more interested in theory and a priori reasoning that makes sense to me on these issues, even if in principle empirical evidence should be better.

A couple notes:

1. Studies that attempt to tell you what will come (predictive) are in a different category than those that try to unscramble the eggs of what has occurred. Predictive studies are very dependent on their assumptions.

2. Some things are simply not knowable or close to it. As above many studies attempt to root out causation where many confounding factors exist (unscrambling the eggs). Invariably they use models with assumptions and “truth” pops out of the math-e-magic. Many studies falling on both sides may simply mean nobody really knows.

Some of these studies are likely best efforts and possibly without any bias. And they can still be pretty much useless in finding fact. The best and brightest trying their hardest doesn’t equate to useful outcomes.

You will find activists to be the most prone to “single study syndrome”, invariably only quoting the most extreme outcomes that support their side. This seems to be counter-productive as it invariably hurts their credibility in the long term.

This is all fine and business as usual, but what I find distressing is where there is a somewhat corrupt sector of science that feeds activists what they want to hear and attaches an aura of authority to it. The less ugly cousin is confirmation bias where outcomes are heavily dependent on data processing methods and the “right” answer can be found by tweaking methods and models.

Of course, this leaves out any mention that the minimum wage is totally immoral, because it’s a form of coercion. If you believe it’s wrong to point a gun at someone who doesn’t obey your ideas of a utopia, then you have to disbelieve that the minimum wage is a good idea. Also, you’d need to analyze so many effects along such a long time curve that absolutely no study on the minimum wage, pro or con should be trusted, even slightly. Noone can see the perverse incentives associated with the tendency of more coercion to prevent innovation, and the opening of new marketplaces.

This could be a result of the minimum wage, or it could be the result of the coercion and uncertainty of the political environment that allowed the minimum wage (who’s to say it won’t get hiked again, and again? this eliminates the ability to reliably plan, and that ability is assessed differently by every different business. What if your business or planning ability is robust and fault tolerant? Then you keep your business open, because “it can take it” no matter what the minimum wage is. So, do the studies really examine every single business, and determine 1–what the IQ of the business owner is 2–what the cash reserves at every stage of the business’s life have been, and currently are 3–how fault tolerant the business itself is 4–what the competition for the business is like 5–what other options there are for the business owners if they close 6–what surrounding areas are there, that a business could move to, if they viewed the minimum wage as unacceptable 7–would the business owner have invested the excess money now spent on wages on capital improvements to the business that would have employed more people, or allowed him to expand? This last question is totally unknowable, but one can assume the business owner would have spent the money in the way he saw was optimal. So, by forcing him to pay that money on minimum wage, you’ve threatened him into behaving in a way he previously had indicated he wouldn’t act, without the coercion.)

The only thing we know is that the minimum wage requires coercion, and the market does not. That most businesses pay more than minimum wage indicates precisely what the market would pay. If people want to pay less, then inherently one can assume that, if they would pay much less, while wanting more work done, then there would be some people who go jobless because the employer cannot afford to pay.

What if it’s only 1 person? Even so, if one person has their rights violated in one area and cannot employ as many low-skilled workers as he’d like, he may move to another area. Even if he doesn’t he still had the displeasure of having the state tell him how to run his business implying that his judgment wasn’t accurate.

And what if it was? What if the min-wage person was happy enough to work for the min wage, because he didn’t need to pay for housing and wanted the easier job? Now that his employer is forced to have fewer workers, he may want a better quality worker, and fire or “lay off” the less hard-working. After all, the state can’t force him to remain as an employer.

The fact that the state can’t force an employer to remain in business (that’s known as “slavery”), means that the state shouldn’t impose a minimum wage. What right do they have to tell anyone how to spend money that they didn’t even have to make? What right do they have to bully people who don’t want to be bullied?

It’s generally not useful to make comments assuming a specific morality that the vast majority of your interlocutors are not going to share.

“useful”? There you go again, assuming consequentialism, when Jack is clearly a deontologist.

Jack is also arguing. The point of argument is generally to convince one’s opponents. Just because someone isn’t a consequentialist doesn’t mean that they never have goals. Sure, it’s possible that Jack is arguing for no reason, but unless you’re Jack and accidentally posted anonymously, I don’t think there’s any reason to believe that.

I’m pretty sure Anon was telling a joke. (I liked it!)

Everyone seems to have missed this, but I’ll bother you specifically about it.

This doesn’t “leave out” anything. I don’t care about the minimum wage. I was using it as an example of how there can be multiple studies on both sides of an issue. Whether or not it’s immoral doesn’t matter in that context.

You’re right that the state uses coercion. The problem is that the same can be said about property rights.

In the particular example shown, “the bell curve skews slightly left” is the consensus expert opinion: the minimum wage likely has small negative employment effects. If you’re on the right, this proves that the minimum wage increases unemployment, done. If you’re on the left, it proves that the policy has small costs relative to benefits, done. Obviously neither side can/will recognize offsetting arguments in the sound bite/headline version of the argument.

(I am personally concerned that the harms of unemployment are understated by looking at “wages lost” instead of horrible psychological effects.)

We also know from one study (woo! I can find a link when I’m at a real computer) that US labor economists skew left. Would you interpret that to mean that the research somewhat understates the harm of the minimum wage (policy preferences drive research results) or that research like this is good and pushes you leftward as you study labor economics (research results drive policy preferences)? (Feel free to shout “false dichotomy” here.)

No, that’s not the consensus. There really is a factual disagreement. As you could tell if you had read the post. Or meta-analyses.

In English, “consensus” can mean the average or general opinion. It is also sometimes used to mean a unanimous opinion, so one can see how that can be confusing for people still learning the language. Factual disagreement is not inconsistent with having a central tendency in expert judgment on an issue.

That you are wrong about English does not change the fact that you are wrong about the state of economic opinion.

What’s really fun is there’s not even fundamental agreement on terms. You can get together a lot of studies on “unemployment”, “wage”, and “negative impact”, none of which use the same terms to mean the same thing, and many of which will use the terms in a way no sane person would. Unemployment can reasonably mean workforce participation rate, or people who are looking for work and not currently working a certain number of hours a week, or people who have been looking for work for a certain period of time, or a count of individuals who are not employed for N hours a week, all of which are different things and look toward entirely different trends. Wage can range from the actual per-hour wages to including any of a wide variety of non-monetary benefits, may or may not be indexed for cost of living, and may or may not be the actually paid rate as opposed to the declared rate.

That’s before we get to the unreasonable definitions, which are a dime a dozen, or the question of which well-recognized standard of measurement we use.

And this is a field with well-recognized special terms, and government agency after government agency giving the exactly definitions and numbers for many of these things.

Economics presents the problem of being much more politically charged than medicine, but the advantage of being more amenable to a priori reasoning (here revealing my Austrian tendencies).

That is, there’s no logical, a priori reason to expect any substance to have any particular effect. We might say that “given that amphetamine is a stimulant, we wouldn’t expect methamphetamine to be a depressant,” but that still depends on empirical observation of the effects of amphetamine.

Compared to this, you can say, logically, regardless of what data points show, that we would expect people to buy less of a thing the more it costs. This doesn’t require any particular observation, other than those involved in being a person living in a world of scarcity. We know it by simple reflection and have every reason to believe others act similarly.

Of course, we can and should test the a priori theories against real life to some extent. There may be some weird case of a luxury good where people buy something expensive to signal something about their status, and so the high price itself becomes a “good” of a kind. We may also be able to figure out whether there is a good reason either to rethink our a priori conclusions, or else to believe that there are some empirical effects strongly ameliorating them–like an inelastic demand curve, say (and this is, tbh, the only reasonable way to argue for minimum wage, imo–not to say that it doesn’t cause unemployment, but that the degree to which it does cause unemployment is relatively small compared to the benefits).

But we also have to be super careful about inferring causality, of course, since there are always so many potential confounding factors–say unemployment was about to go way down due to other factors, and then we raise the minimum wage and it still goes down, only less. One can start to intuit a general empirical trend if there is enough data available for say, many different increases of the minimum wage at different times and places, but no one thing can ever be isolated (though in this respect, it is kind of like medicine, where you’ve got so much going on inside any given body).

Anyway, since basic logic tells us that raising the minimum wage should increase unemployment (though not by how much), I think one should err on the side of assuming it does, unless very strong empirical evidence can point you in the direction of why this would not be so.

This is different from drug studies because the human mind cannot come to rational, a priori conclusions about the effect of some chemical substance on the human body. It can, however, come to conclusions about its own decision making and that of other minds, which is what economics is all about. These conclusions may be far from perfect due to “no typical mind” and the huge number of other factors at work, but they are still possible.

I guess what I’m really getting at is that we shouldn’t start a debate about the effect of something like minimum wage from a stance of total agnosticism and only then make up our minds based on pure data, given that we have logical reasons to believe one thing rather than another. Empirical data could so strongly favor a conclusion opposite to our logical intuition that we are forced to reexamine the latter for bias or failure to take into account some factor, but we should start with the assumption that things are as they seem.

Given that the empirical studies seems fairly inconclusive, I’m going to go with the seemingly obvious conclusion: minimum wage does cause unemployment. A little increase in the minimum wage increases unemployment a little, and a big increase in the minimum wage increases unemployment a lot.

The ‘minimum wage and unemployment’ argument is part of a really interesting meta-debate.

The key thing to watch is how the conservatives are able to massively out-maneuver the progressives by exploiting two effects. First, they’re focusing on a narrow technical question that they know will be misunderstood. And second, they’re exploiting progressives’s treatment of equality as a sacred value.

Both of these tricks are encapsulated in the AEA survey.

To see why these problems are misleading, consider a scenario where we could increase wages by $5/hour for 100,000 people at the cost of 2 jobs.

Technically, the first question is asking if a LARGE increase wage will have ANY effect on employment. That invites the economists to answer yes. Even if they think the effects are as one-sided as in the hypothetical.

The gimmick is that economists say ‘AN effect’ and the public hears ‘A LARGE, IMPORTANT effect’. And so they assume that the question is somehow relevant to policy making.

Progressives tend to get lured into an ambush. It feels rhetorically important to refute the conservative subtext. But the literal economic claim “big price increases tend to reduce demand” is super-easy for conservatives to defend.

The progressives should be willing to concede that policies aren’t one-sided. The wage increase will help the overwhelming majority of people. If the conservatives want to argue for a LARGE effect, they should do it — but the research doesn’t really bear that out.

But that’s where the second question: “68% think these employment losses fall disproportionately on the least skilled” comes in. The factual question is trivial — minimum wage changes will mostly impact people making the minimum wage.

I think it’s asked to invoke ‘equality’ as a sacred value. That $5/hour increase for 100,000 people at the cost of 2 jobs would be massively beneficial. But technically, it would increase inequality in that group.

The result is that people are primed against acknowledging possible tradeoffs. So, instead of the policy important debate of “will unemployment increase enough that we should care” most people get stuck at “will unemployment increase at all”?

Conservative economists do not actually believe “haha, the minimum wage actually will have utterly insignificant negative effects in the aggregate, but we have this cute rhetorical trick to make it sound like they will”. They genuinely believe that the policy will be a net harm to the class of people it is intended to help, and a net harm overall. That is to say, they believe it is an instrumentally bad policy even under their opponents’ value system.

Yes, but their opponents don’t, and yet their cute rhetorical trick makes it sound like they do. This model permits the conservatives to be perfectly sincere in their beliefs; they’re just dishonest in their argumentation. They’re trying to make their honestly-held position seem like more of a consensus than it is by using leading questions that obscure the actual controversy.

See below. I think most conservatives in that position honestly believe that they are responding to someone who is arguing for the proposition that there is either no loss or almost no loss of employment from minimum wage increases.

This was my perception of unemployment extensions. There were a lot of people in 09 on the blogs arguing that under economic conditions at that time, extending unemployment from 13 to 99 months would have literally no effect on unemployment, because there weren’t jobs to be had, and conservatives saying “what are you talking about?” Eventually, it turned out that everyone who knew anything (about 25% of the debaters basically agreed that under those conditions, the best but imperfect estimate of the effect would be that unemployment would increase by about 0.5%, and at that point, we could talk about whether helping the other several percent made that worth it.

The dishonest argument is a meme that thrives in an environment of people arguing both for and against it, with the people arguing against it not understanding the trick. But the people arguing for the argument don’t have to understand the trick either. It could even be “better” if they don’t, so they can’t leak the understanding to their opponents.

The economists were answering the question they were asked. I have no objection to that.

What’s interesting is how partisans can ask experts “is the effect non-zero?” knowing that the public will hear “is the effect big enough to change policy?”

Bonus points if the other side can get invested in “effect is definitely zero!”

I’ve seen similar games played with questions like: Does public benefits fraud exist? Do vaccines risk permanent brain damage? Are there are natural causes of global warming?

This pattern is interesting to me because it happens so frequently. Conservatives have a ton of true-but-trivial statements they can throw out. People rush towards the trap (“vaccines have no risks!”), and lose what should have been an easily winnable argument (“on balance, vaccines are overwhelmingly worthwhile.”).

Thinking about it, this dynamic is the most common reason I see progressives lose otherwise-winnable arguments.

What do you mean by “win” and “lose”? It sounds like you are using “lose” to mean make statements that you judge false. But that sounds like a lousy goal to me.

‘Lose’ = ‘Fail to convince an audience’

“Conservatives have a ton of true-but-trivial statements they can throw out.”

The example statement you’ve provided does not seem trivial if large numbers of people are under the impression that the statement is false or debatable, to the point of “taking the rhetorical bait” (so to speak).

You are right: it is important to evaluate the trade-off as a whole RE: benefits accrued to those who have their wages increase as opposed to those who see themselves without work. So long as many progressives do not acknowledge the latter drawback to a minimum wage increase, how can stating the fact that this drawback exists be “trivial” when the valid public policy question (as you yourself acknowledge) is something like, “are these disadvantages large and if so, do they outweigh the benefits of a wage increase for remaining workers?”

To the degree that it is a “rhetorical trick”, it is because the discussion is not even close to arriving at what is already known and deduced in academic circles regarding the subject.

>’What’s interesting is how partisans can ask experts “is the effect non-zero?” knowing that the public will hear “is the effect big enough to change policy?”’

I think this gives the public too much credit, by assuming people would react any differently to “non-zero” vs. “large enough”.

Let me challenge your perception a bit.

My perception is that when conservative economists argue there will be a reduction in employment as a result of minimum wage increases, they are responding directly people who have stated the position that there will in fact be no change in employment, or almost none. (And to be fair, Scott’s funnel graph suggests that’s a defensible position, althouth I think it’s intuitively not).

My perception is that progressives often argue that their preferred proposal (high speed trains from point a to point b; Obamacare; minimum wage increase) has at least some benefit, but ignore the cost. Your perception is that conservatives often argue that the program has some cost and ignore the benefit — it might be that both sides are doing a cost benefit agreement but arguing with their mistaken perception of the other side’s position.

I’m not critiquing economists, conservative or otherwise. They answered the question asked. They’re good at doing cost/benefit discussions.

I’m saying that conservative policy advocates (who are generally not economists) use a clever rhetorical trick to bait otherwise intelligent progressives into taking dumb positions.

Then I’m exploring the trick.

I think I agree with your subtext that it’s not a particularly unfair trick. There totally are minimum-wage advocates who’ve invested themselves in there being absolutely NO effect. And it’s fair for conservatives to respond to that.

I’m calling out the trick because I’d like people to stop falling for it.

—

That said, it sounds like you lean conservative, so I have a question.

Can you think of any examples where liberals use this sort of provocative technicality to out-maneuver conservatives?

All of the examples that come to mind are cleverness by the ‘other’ tribe. That seems like a blindspot

I generally feel like discussions of ‘needing’ X in gun control debates frequently take that general form, i.e. “Nobody needs (feature) for (Schelling point use case)” is deliberately used to try to get the argument onto what is and isn’t needed for what, and get the implicit concession that anything not ‘needed’ should be forbidden. It has, however, gotten less effective in recent years.

Ahh yes, the cunning mastery of those devious conservatives of all academia, with their noted conservative bias!

Interesting that the main competing propositions being presented here are “negative effect” versus “no effect” on the economy. Maybe this has something to do with the fact that I’m mostly surrounded by blue-tribe people, but I often hear assertions that an increase in the minimum wage would positively affect the economy. The idea seems to be that not only would it not significantly increase unemployment, but it would directly benefit the working class, who would then spend more. I think I’ve even heard Obama make vague assertions about a rise in minimum wage strengthening the economy from the middle class outwards. Unfortunately, I don’t have a good enough understanding of macroeconomics to really evaluate the plausibility of this hypothesis.

Your second meta-analysis link is broken. Here is the correct link.

Minimum wage is a fascinating epistomological problem.

On the one hand, it seems intuitively obvious to me that there should be some reduction in employment over the medium and longer term. First, there should be some jobs where it’s now cheaper to substitute other means of delivering the service. Second, and probably more importantly, you would expect an increase in labor costs to result in an increase in product cost, which should encourage consumers to substitute where they can.

Now these effects may be pretty small if minimum wage labor is a small component of the overall costs, but I wouldn’t expect them to be zero.

On the other hand, that’s a pretty convincing funnel plot (seriously). I’m honestly not sure what to do next.

I never understand why everyone gets this wrong- in econ 101 world, an increased production cost should not be associated with a price increase- the price that maximizes profit is independent of the production cost. Changing the price to cope with an increase in production cost will just hurt you twice.

The employment effect happens because marginally profitable businesses are no longer profitable, and they close down. This result in fewer jobs. In an econ 101 world, where most minimum wage labor demand is highly profitable national chains we’d expect a very small effect.

… false?

Profit = Quantity * (Price – Cost)

In the econ 101 model with a downward sloping demand curve, the profit-maximizing firm will always increase Price in response to an increase in Cost, although not 1-for-1.

And if you have perfect competition, then price = marginal cost, and so actually will increase 1-for-1.

There’s a school of thought that says businesses are inefficient and need to be kicked into making improvements. During the recession, companies trimmed the fat and laid off workers, yet profits are record high anyway.

The government did provide financial incentives to invest in productivity increasing machinery.

Although that probably isn’t the reason. What firms were making record profits and which ones where shedding workers?

One hypothesis from Macroeconomics 101 is that increases in aggregate demand offset the increase in unemployment.

Well, as someone old enough to have been working a shop job when the minimum wage was raised in the ’90s, the interesting thing to me was how mad it made people making just above the new minimum wage. I was the new kid, I’d been making $2-4 less per hour than the guys with more seniority. When the hike hit, we all were basically making the same. Those guys didn’t get a raise, and in effect, I took their raises for the next several years. Unamused were they.

That’s interesting, since one of the common anti-minimum-wage arguments appears to be ‘if we increase the wage for unskilled minions of the third and lower kinds, we will have to increase the wage for everyone else proportionally and that will be a much greater cost than just the minions’.

I don’t have an opinion one way or another about wage compression, but I’ve had the good luck of a career in industries where wages are not so significant a cost that increasing them 3% annually is an issue – effectively support groups for really expensive bits of capital equipment, where the cost for the crystallography-software group or the CPU-design group is minimal compared to the cost of electricity and consumables for the synchrotron or the chip fab.

FYI, the reason minimum wage discussions suck is, IMO, almost certainly because minimum wage changes have low to no short term negatives due to wage and employment stickiness effects. But conservative economists are lunatics who regularly deny that these exist, or else insist that these cannot possibly have meaningful effects. Acknowledging that they do would undermine conservative theory on unemployment.

So they can’t explain their opponents error without committing heresy against conservative economic doctrine.

I’d be interested to read a conservative economist who thinks that minimum wage would necessarily have a short term effect on employment levels – my guess is that most think that medium and long term effects are inevitable.

I am having difficulty understanding how you could come by this belief.

What other explanation is there for the huge publication bias?

I imagine they generally set those issues aside because it’s so arbitrary how sticky you make things. It’s not really something that can be disproved or addressed outside of showing how other simpler models will explain the same thing.

That said, I’m sure there are papers confronting it directly.

Because stickiness effects explain why wages do not adjust to economic downturns the way certain economic models predict. Because this leads to a chain of inferences that explain involuntary unemployment and justify stimulus bills. Because if you pay attention you can watch them do what I described.

If you can, please send me some links to someone who denies short term stickiness in minimum wage effects, as opposed to arguing that there are medium or long term effects.

try half of the links here: https://slatestarcodex.com/2014/12/12/beware-the-man-of-one-study/

Edit: sorry, that was nasty which I shouldn’t be.

You’ve made the error of identifying “conservatives” with “a particular school of macroeconomists, many of whom actually do accept nominal and/or real wage and/or price stickiness as a central feature of their models, but who tend to be misrepresented or weakmanned by Paul Krugman”.

If you actually peruse the conservative econ blogosphere, for example, you will see widespread (near-universal?) use of stickiness as a prominent feature of the models where it is relevant.

I think one of the main points of this blog is that that is a bad argument.

That’s because it’s not an argument at all?

Perhaps you’d care to cite one of these “lunatics”?