The Guardian tells us that Limits To Growth Was Right: New Research Shows We’re Nearing Collapse. The article begins:

The 1972 book Limits to Growth, which predicted our civilisation would probably collapse some time this century, has been criticised as doomsday fantasy since it was published. Back in 2002, self-styled environmental expert Bjorn Lomborg consigned it to the “dustbin of history”.

It doesn’t belong there. Research from the University of Melbourne has found the book’s forecasts are accurate, 40 years on. If we continue to track in line with the book’s scenario, expect the early stages of global collapse to start appearing soon.

This is not only wrong, it’s so wrong that it may actually be the first real-world example of an exotic form of reasoning famous among philosophers for challenging the very concept of evidence.

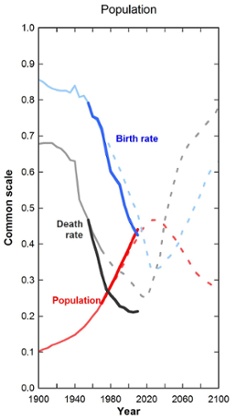

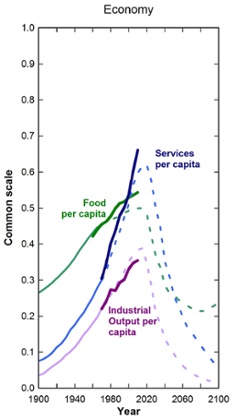

Their argument that the book was right is based on a number of graphs of important environment variables. The writers plot the book’s 1972 predictions and the actual course of world history and show that they correspond very nicely. For example:

. .

. .

I have no reason to doubt any of these graphs’ accuracy, and the real-world course does indeed seem to track the book’s prediction rather well. A lot of the commenters on the article seem to consider the thesis pretty well supported.

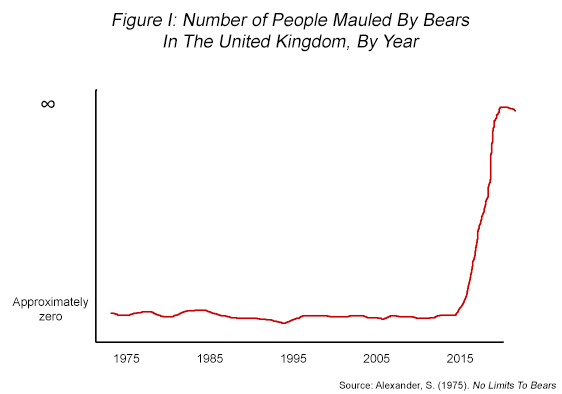

But here’s another graph I have no reason to doubt. The source is my own 1975 work, No Limits To Bears:

(okay, I didn’t actually write a book called No Limits To Bears in 1975. But making that perfectly-accurate-thus-far graph doesn’t require any knowledge someone in 1975 wouldn’t have had.)

Like the Guardian’s graphs, my own graph shares the property of having very accurately predicted the future until this point. Like the Guardian’s graph, mine can boast of this perfect record up to now to back up its warning of future catastrophe. Does that mean the British people should start investing in bear traps? An infinite number of bear traps?

No. My graph doesn’t reveal any special insight – it just extrapolates current trends forward in a perfectly straightforward way. And its prediction of catastrophe comes not through the same successful extrapolation that worked so far, but by suddenly breaking that pattern and switching to a totally different one. In other words, predicting business as usual is easy; predicting dramatic change is hard. Success with one doesn’t necessarily imply success with the other.

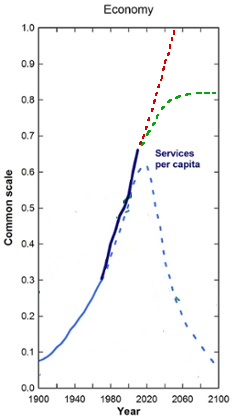

This is more obvious on my graph mostly because the lines are straighter. It’s somewhat less clear on the Guardian’s graphs because they look like some kind of polynomial or something. Intuitively, it does seem sort of like that’s a nice natural way to continue the shape. But note that there are other, equally nice and natural ways of doing so:

This is a graph from Limits to Growth. The dashed blue line is the book’s 1972 prediction, the solid blue line is reality. The dashed red and green lines are alternate models I just made up.

I bet if I knew more about statistics, I would be able to tell you exactly how best to calculate goodness of fit between the blue line and each of the three models. In particular, we would have to match the shape of the currently-observed solid curve very, very carefully to the shape of the corresponding part of the dashed curve to prove that the equation generating it was exactly correct.

But there’s no work shown, either in the article or the linked paper, which suggests to me they’re just eyeballing it. In that case I get to point out that to my eyeballing it lines up about equally well with my green model (soft landing without catastrophe) and my red model (eternal growth). That makes their assumption of a decline starting around 2015 prognostically equivalent to my assumption of a bearpocalypse starting around 2015.

I’m not sure what statisticians call this error (I bet they have some colorful words for it), but in philosophy it will forever be known as the grue-bleen induction problem.

Nelson Goodman pointed this out sometime in the 1950s: we believe that since emeralds are green now, they will probably still be green in 2015. But this belief is without evidence. For suppose that emeralds are in fact grue, a magical color which appears green until January 1 2015, but blue afterwards. Right now, our observations correspond perfectly to this hypothesis. You can’t correspond any better than perfectly! Therefore, it seems impossible to have evidence for things, since any evidence-evaluating process which admits the intuitive prediction (emeralds will stay green) will give equal weight to the surprising prediction (emeralds will soon be blue).

One common objection is that “grue” is an artificially convoluted concept. Goodman rejects this. Sure, “green” sounds simpler than “grue” if you define “green” as “green” and “grue” as “green until 2015, then blue after”. But suppose we have another magic color, bleen. Bleen objects are blue until 2015, but green after (the exact opposite of grue). Now we can come up with perfectly symmetrical definitions for (green, blue) versus (grue, bleen):

Grue means “Green until 2015, blue afterwards”

Bleen means “Blue until 2015, green afterwards”

Green means “grue until 2015, bleen afterwards”

Blue means “bleen until 2015, grue afterwards”

It all checks out!

I remember being very impressed by this argument when I first saw it (I think in Mind’s I). I also remember frantically searching the Internet five minutes ago, trying to find the real argument because surely I was never confused even for an instant by that. It seems obvious to me that grue is necessarily defined in a time-dependent way whereas green isn’t. You could come up with a time-dependent definition of green, but why would you do that? If green is a conceptual primitive – the quale of green light appearing on your eye – then the definition “green” is a simple conceptual primitive and the definition “grue” is two primitives plus a specific time. Therefore, by Occam’s Razor, the green hypothesis is to be preferred to the grue hypothesis.

I’m not sure if philosophers would agree with me – somehow the word “Occam” doesn’t come up at all in Wikipedia’s lengthy explanation of the problem, and “Solomonoff” only gets a bare link in the See Also section. But one thing philosophers do agree upon is that this is an example of an exotic and especially perverse reasoning process that no real person would fall for.

Which makes it weird that the Guardian does exactly that. “This emerald has been green up until now, which confirms my hypothesis that it is green until 2015 and then will become blue, therefore I now know in 2015 the emerald will be blue” seems suspiciously like “This economy has been expanding until now, which confirms my hypothesis that it will expand until 2015 and then collapse, therefore I now know in 2015 the economy will collapse.”

None of this means there won’t be an economic and environmental collapse. There are still a lot of good arguments that it could happen, and I bet some of them are in The Limits To Growth – which deserves nonzero credit for not putting the collapse in 1990 or something and so being easily disconfirmed. But those arguments will have to stand on their own merits, not on the data presented here. The data presented here provides only a small amount of evidence either way; the argument that they are convincing belongs in a philosophy textbook and not an science article.

The Guardian concludes: “Our findings should sound an alarm bell”. Maybe so, but it’s probably not the one that they think.

It’s not really relevant to your point, but Goodman’s grue isn’t actually a magical color that changes on some date. Something is grue if it is observed before $date and is green, or observed after $date and is blue. There’s not necessarily any color change involved. Goodman then asks: Suppose I observe an emerald after $date. What color do I predict it will be?

The standard response was given by Quine in “Natural Kinds” in which he argues that, seriously dude, “Grue” is just retarded. I mean, come on. And don’t get me started on that non-black non-raven shit.

Interesting to ask why we don’t see a lot more predictions like the Club of Rome’s, really?

I would assume that, given the massive “analyst industry” that exists across academia, think tanks, consulting and finance; the need to protect clients and constituents from the downside of such a collapse; and the money to be made and protected by someone who could successfully predict said collapse- that it would follow that the number of analysts predicting such a collapse would have increased as we reached this 2015 threshold, and we’d see a convergence of predictions towards the baseline of the Club of Rome’s predictions.

This hasn’t happened, which makes me doubt them. Now, one could point to crashes like the 2008 financial crisis, but I don’t think these really count as they are basically blips on long term global trends, whereas the Club of Rome predicted something much, much more fundamental and structural (in a way that makes the changes from the financial crisis pale; the sort of demographic changes they predict exceeds the fallout of the World Wars and the end of the Cold War.

WRT Lomborg: Self-styled climate expert James Hansen, late of NASA, has said, of the current world temp plateau now approaching eighteen years (paraphrase) “level now, hell when it breaks loose.”

Should things collapse in 2015, and we have approximately sixteen months in which at least a noticeable start must be perceptible, it might be because of ISIS and company getting hold of a couple of nukes and taking out some financial centers–London, NYC, etc.–or the oil fields in SA and neighboring locations. Or the US power grid. None of which figure in the predictions. And if this happened, it would not prove the predictions were correct.

I agree more with Scott, but the Guardian’s not quite as idiotic as all that. Here’s what I would reconstruct as the stronger version of their argument:

People currently think that Limits to Growth is a bunch of debunked, 1970s nonsense because it predicted global collapse, and we have in fact seen continued growth and material progress since it was written. However, the book didn’t predict a collapse until at least 2015, so while the lack of a collapse thus far isn’t evidence in favor of the Limits to Growth position, it also shouldn’t be considered as evidence against it as many currently do.

Rather than the grue-bleen dichotomy, the idea is that the original authors (presumably) had non-arbitrary reasons for predicting a collapse when they did, and if they were right we should start to see evidence of it in the near future. They basically just made a long term prediction back in 1972, and we are finally about to see how they did.

IIRC they made a number of predictions based on variations of their model parameters. The model used predicts a collapse of population and living standards during the 21st century. In short, it is just the result of an exponentially increasing population meeting a resource constraint with some terms that produce a time lag (to prevent smooth adjustment to a ceiling). When the authors used “realistic” values for parameters, they got the 2020 or so collapse prediction.

Nevermind, forget this comment. I can’t read. (Though I don’t really understand what a “conceptual primitive” is. Seems like question-begging.)

Dunno about philosophers, but cognitive scientist Peter Gärdenfors makes basically the same argument about bleen/grue in his book Conceptual Spaces. IIRC, the thesis of that book was basically “concepts are clusters in thingspace, and the axes correspond to sensory-based conceptual primitives”.

EDIT: sorry, I realized I basically repeated something that was already in Scott’s post

Help me out here if you would, is the following a form of the same logical perversion? I hypothesize that Scott Alexander is the kind of guy who eats, sleeps, breathes, and fucks little kids. So I follow him around for a bit, and lo and behold, I witness him eating, sleeping, and breathing. This is all excellent evidence for my hypothesis!

I wonder how much is lost/altered in my conversion from the properties of inanimate objects to the behaviours of people. In each case I feel like there’s an expectation of continuity which boils down to being an incidental property of the universe that we’ve evolved to expect as part of our pattern-recognition survival thing.

Also, the Bible says that there a country called Egypt, an empire ruled by Rome, cattle, and a man who came back from the dead.

I think it depends on your prior beliefs and how you get the evidence.

Imagine that there is a holy book that makes four claims: A, B, C, D. At the beginning, I have no idea about truthfulness of any of them; and all of them seem equally likely to me.

Situation 1: I only have resources to verify three of these claims. I randomly choose which three of them it will be; and the result is A, B, C. I verify A, B, C, and they are all true.

Situation 2: I ask the believers to bring me proofs about A, B, C, D. There is some filter, so only the solid proofs get to me. I gradually get proofs of A, B, C.

There is already a difference here. In the second situation, it is reasonably to believe that D is the least likely of these claims, because it takes most time to bring the evidence. In the first situation, I chose D randomly, so that method is more reliable.

For example, if my model is “99% of holy books contain three true claims and one false claim, and 1% of holy books contain four true claims”, the second situation provides zero evidence to distinguish between unreliable and reliable holy books. In the first situation, I have updated that this holy book is reliable with probability 4%, because I would have a chance 3 in 4 to detect an unreliable holy book.

With some of the graphs, I’d go as far to say that the most recent parts of the trend actively work against the thesis of Limits to Growth. Looking at some of the predicted curves, things ought to be starting to tail off about now, the second derivative ought to be getting decidedly negative. And in two out of the three Economy graphs, that doesn’t seem to be the case.

If your grue theorist said, “the emerald will be blue in 2020 – the transition won’t be instantaneous but sigmoidal, here’s a graph”, and reading the graph it looks like you’ll be able to see the emerald looking just a little bit more cyany than usual in 2019, then 2014 we’ve got no good direct empirical test of whether the grue theory is right, we can only go by simplicity, consistency with our other knowledge, etc. In 2019, on the other hand, we do have an empirical test.

Of course, someone will say, “the sigmoid’s a continuous model, a test emerald should be getting more cyany as we speak”, but if the predicted change in colour in 2014 is smaller than anything we can measure, then we don’t have a test.

Even predicting a simple continuation of a trend is occasionally a fraught endeavor.

I was reading a book yesterday, where someone was talking about some silly person who extrapolated some obesity trends and worked out that in America, absolutely everyone would be overweight by 2048. The extrapolator then broke their data down by race and said that all the black people would be overweight only by 2072 (or some year about then, I forget the exact number)… without noticing the contradiction with the first statement.

What’s the problem? In 2048, 90% of black people will be overweight, and 140% of white people will be, and overall 100% will be. The math works out just fine.

Unrelated to your current post: I wonder if you agree with where Sean Carroll place the Schelling fences here: http://www.preposterousuniverse.com/blog/2014/09/03/troublesome-speech-and-the-uiuc-boycott/

Provided the book had correctly predicted something unexpected (I don’t know whether it did), it makes sense to give more confidence to its further predictions than to a random squiggle.

That’s not how system dynamics works.

At no point on the model would there be any change in the equations or pattern. What cause the inflection is from two variables you don’t show but the guardian article does, pollution and resources.

This is a relatively basic model, its not simple statistical extrapolation

http://paws.wcu.edu/emcnelis/SV/presentations/chytrid/chytrid_web_page/vensim/index.htm

Considering that resources feed the process and become more expensive to extract as scarcity increases (the energy cost of metal extraction as purity decreases is a good example) and pollution causes costs. Like Lead increasing crime rates. They’re fairly important to understanding the model.

Agreeing with Leo here.

The way they extrapolate the population curve makes a lot of sense in terms of the underlying model, not just in terms of drawing a good-looking extrapolation. The dropping birth and death rates leads to a rapidly aging population, which means that the death rate picks up again in future years and the population will decline. The shape that they’ve drawn illustrates this perfectly.

Decreasing industrial output is also a very sensible outcome under those circumstances, as workers retire, retirees age, and care of the elderly consumes an increasing fraction of the decreasing productivity.

The demographics alone are already enough to make that a fair case (although not necessarily for 2015), without environmental and resource constraints. China and Japan are demographic time bombs, and their governments are well aware of this and attempting some mitigation strategies (such as expansion in Africa). North America and Europe are in, if not the same boat, at least the same pool.

I agree, the Limits to Growth graph should not be read as an extrapolation with some random inflection point thrown in at 2015 for no reason. Rather, the graph was the outcome of a physical model of economic inputs and outputs.

If the model is going to turn out to have been off in its predictions, then how will it have failed? I think the main thing you have to point to is the “Resources” variable. It turned out we could extract more resources at a cheaper price than was predicted, so we have been able to avoid economic collapse.

I used to be very interested in oil depletion (AKA “Peak Oil”). I like to phrase the problem as “oil depletion” because my concern all along wasn’t about oil production rates peaking per se, but rather, was about oil becoming too expensive (both in monetary and net-energy terms) to allow for the continued growth of the world economy. Back when oil was $20 a barrel, I and others naively thought, “There’s no way that our economy can avoid going into a tailspin with oil over $100 a barrel!” Well, here we are with oil routinely over $100 a barrel and the economy not going into a tailspin.

I have to bite the bullet: that was a macro-economic prediction of mine and others that was falsified. I was wrong. But I still think it was a reasonable prediction–an honest mistake, rather than one that anyone should have known to avoid. It was based on some theoretical calculations of the price inelasticity of oil, a very low EROEI (energy returned on energy invested) for unconventional shale oil, and how sensitive the rest of the economy would be to changes in oil prices.

Well, the oil shale industry came up with some really nifty techniques like toe-to-heel air injection and fracking, and it turned out that this had a much better EROEI and much more manageable cost than predicted, and so the global economy has been granted a temporary reprieve.

Now, the question still lingers in my mind: what do we do with this reprieve? Do we ride the edge of Jevon’s Paradox to the very limit?

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jevons_paradox

Do we maintain our dependence on oil as long as it is even slightly cheaper relative to other alternatives, right up until the very second that it ceases to be cheaper?

Oil depletion would not be a serious issue if oil was any old resource that was completely fungible with some other energy source, and the minute oil became more expensive than an alternative (like electricity) we could just switch to the alternative. Alas, there is oil-dependent infrastructure (gas stations, automobile fleets, highways, patterns of urban development). There will be lag times before we can phase out those oil-dependent assets and phase in new assets that are suited to the alternative. Patterns of urban development, like new coal plants, will be with us for 50+ years. Even if the Peak Oil Apocalypse has not hit like some doomsters were predicting, are we confident enough that oil will still be the dominant energy resource 30 or 40 years from now that we want to place bets on it with investments that we will have to pay for over the next 50 years?

Although I’m not really a “Peak Oiler” in the usual sense anymore, I still have a lingering fear that switching from oil (which we will have to do at some point this century, unless you believe in the theory of abiotic oil) will end up being more economically painful if we insist on doing it at the last moment rather than easing into it and start phasing out 50-year, 30-year, or even 10-year investments (such as automobiles) that will not pay off well in an environment of oil prices creeping upwards.

I do not expect the government to tell people to do this. I expect people (including investors, but ideally not just investors) to do this once they realize that it will make economic sense over the medium to long term. In order to hedge against the possibility of oil price increases, I have:

A. not purchased a new car. I will drive my little fuel-efficient 1997 Honda Civic until it falls apart and then buy a cheap, fuel-efficient replacement.

B. not gotten myself into debt, lest economic problems make it difficult to pay it back. Thanks to paying my way through college as I went, I am completely debt-free.

C. not had any children; nor will I make any plans to have children until it becomes clear how this whole thing will shake out economically. (I have no interest in delivering my kids to a world ruled by Moloch—that is, by primates who are under Malthusian constraints to “race to the bottom” and sacrifice the pleasures in life on the altar of seizing each other’s scarce resources. Either you get to live in the “Dreamtime” of plenty, or life just isn’t worth living at all. That’s my “wireheadist” view of my procreative responsibilities…much to the horror of neoreactionaries who expect us to positively delight at the idea of delivering human flesh to Moloch and becoming pawns in its game ourselves).

Of course, if we monetized the costs of CO2 pollution somehow, then the economic signals in favor of this type of “low-impact” life strategy would be even clearer.

You should get rid of the Honda Civic. The continued reliability of old Hondas is the only thing keeping car theft going in America – newer cars can’t be hotwired, and other cars that are that old aren’t worth anything.

I’m not sure that’s a strong enough effect.

(Disclaimer: I own a 1993 Civic)

Bizarrely enough, it’s a very real phenomenon: http://www.nytimes.com/2014/08/12/upshot/heres-why-stealing-cars-went-out-of-fashion.html?_r=0&abt=0002&abg=0

right, but I’m not saying that selling my car would make a difference.

Ialdabaoth, would you mind using a name that fits on a single line? for example, “Unwitting Servant of Moloch,” “Ialdabaoth, Servant of Moloch,” or “Ialdabaoth of Moloch of Cthulhu”? Note that the cancer mage has de-escalated.

Okay.

thanks!

The problem with your oil calculation was that it ignored the existence of incentives; running out of oil increases the price of oil, which increases the incentives to find other ways to produce oil.

I’d imagine that by the time we actually run out of oil in the ground, the incentives will have been enough for a long enough period of time that we’re producing oil using bacteria or by chemically processing landfills.

Imagine I’m Bill Gates. I’ll write you a billion-dollar check to get me to Alpha Centauri in one year. There, I’ve just given you the incentive to find a way. Should take care of itself…right?

I agree, incentives are powerful things…but only within the realm of what is physically possible. Yes, “they” always come up with something to save the day (biodiesel, etc.) But there is the assumption that the R&D necessary to find the next saving grace is always within an order of magnitude of what the last big innovation cost.

What if faster-than-light travel were actually physically possible, but it turned out that it would take a quadrillion-dollar R&D budget to discover the new physics that would be necessary to make it so? A billion-dollar incentive would do nothing.

If your economy for some reason depended on this faster-than-light travel being accessible for a decent price, your economy would be in deep trouble despite the fact that, yes, technically speaking, “enough” incentive would clear the market and “solve” the problem.

The “next big thing” in oil needs to be within an order of magnitude in cost to the old “cheap oil,” or else it doesn’t really solve the problem of our economy needing (not freakishly expensive) oil to function well as it is currently set up.

We got lucky with fracking. Oil only got 5 times more expensive. What if it had to go up by another factor of 5, or a factor of 10, or a factor of 100, to incentivize the “next big thing” in oil?

Technically, the inflection point is around 1980.

I dont know how fair it is to say the model changes at the inflection point, since all these variables are related.

Once the birth rate falls low enough the population plateaus and starts to decrease since the deathrate will always be non zero (for the forseeable future). As the population ages the deathrate goes up, so the population decreases. Then he just guesses that the birthrate will go back up I suppose.

Of course that doesnt really explain the services per capita stuff since with everyone dieing and increased automation it seems like there ought to more.

Yay for the meaning of “grue” I grew up with! References to its “a monster that is likely to eat you in the dark” meaning (Worm, I am Looking at You) always really throw me off at first.

I used to lack a nice concrete & concise example of Kolmogorov complexity to use in conversation. This is *perfect*.

They throw you off, huh?

That’s how they get you, you know.

You have been eaten by a grue.

This particular grue is bleen.

How can you tell in the darkness?

I’m kinda surprised that the classical malthusian thinkers aren’t referenced much. No Paul Ehrlich, Barry Commoner, John Holdren, Harrison Brown — I’d expected especially the latter to be name-dropped somewhere.

What’s even more surprising is how badly these predictions do even under favorable coverage. I mean, Ehrlich’s modern defense is hard, but at least his predictions went bad because of things like the Green Revolution, new mines, and new technologies : the big criticism is that he extrapolated trends like a man predicting modern New York City would be knee-deep in horses. The predictions here…

I’ve read parts of the original The Limits to Growth in school. The ‘point’ my teacher emphasized as using models of growth that reflected current levels of growth continuing (exponential growth) rather than simple linear projection. But the analysis doesn’t do much better. Several do much worse than naive extrapolation, most obviously per-capita food, but also service and even death rate.

And the numbers they’re emphasizing are weird, especially for the few that they predict well. They’re reasonably accurate for ‘resources’, according to their numbers, except ‘resources’ is defined as traditional reserves of oil and natural gas. ‘Pollution’ looks amazingly on-the-dot for a graph predating the fall of the Soviet Union, except it doesn’t show a drop or even decrease in rate of growth at the fall of the Soviet Union, which is the first hint that this is really just the use of CO2 as a proxy. Predicting CO2 growth remains reliable isn’t much of an accomplishment. To the shallow read, I’m really hard-pressed to tell what differentiates their model from other Peak Oil assumptions, or why they think a very near Peak Oil scenario is so uncontroversial.

At a deeper level, I don’t think they understand how volume of a shell of a sphere /works/, at least not at a very deep level.

((In unrelated news, congratulations and my most sincere sympathies on your Instalaunche, even if it did correlate with the comment section on the recent gender thread exploding.))

Instalaunche?

Colloqualism for folk linked by Glenn “Instapundit” Reynolds. Usually brings a pretty decent-sized traffic boost, with all the Sturgeon’s Law related results.

Oh, that’s why that post got over 1200 comments? I thought that was weird but figured it was just the result of the topic being one that tends to inflame passions.

No, it had over 1200 comments well before it was linked. In fact, the comments were closed before it was linked. I think it’s just that the SJ-themed posts on here are the most popular posts and steadily rising in attention, probably much to Scott’s chagrin. Hopefully some readers stay for the other stuff.

Apologies for hijacking this tangential thread for my own narcissistic purposes, but I had some thoughts about the comments policy inspired by the recent GenderFail and I would really like to know if anyone agrees with me.

FWIW, I found this image after about 30 seconds of googling:

http://149.168.59.251/NCWRC_QA/Wildlife_Species_Con/Black_Bear/images/Bear-Population-Estimate-by-Region_view.jpg

http://149.168.59.251/NCWRC_QA/Wildlife_Species_Con/WSC_Black_Bear_Populations.htm

So, bear population has indeed been increasing (if only in North Carolina). Now, if you’ll excuse me, I’m off to Costco to buy several crates of bear traps 🙂

Your analysis of grue and bleen – that they’re time-dependent in a way that green and blue are not – is indeed pretty much the standard position: if you don’t know what year you’re in, you can’t tell if something is grue or not by looking at it.

(Or at least that’s the impression I’ve gotten based on what I’ve read in various books.)

That doesn’t work. You can say “green means ‘grue before the year 2015 and bleen from the year 2015 on'”. Then you can say “I observe this object to be grue”, and go on to “If I don’t know what year I’m in, I can’t tell if something is green or not by looking at it–my observation of grue could mean that it is green or could mean that it is blue, depending on the year”.

And you can’t solve that by saying “green is something I can observe and grue is something I can’t” because that’s what you’re trying to prove.

How about green and blue are things that I can observe with a spectrometer (they are light with a wavelength in certain intervals), but for bleen and grue there are no instruments with which they are the primitive/observable values?

If you respond that the spectrometer shows one thing before 2015 and another thing after, then how about with green and blue as primitives there are fewer things that change definition/calibration on that arbitrary date than there are with bleen and grue?

That doesn’t work, because you can do the same thing for the spectrometer reading as you did for blue and green: I don’t know what the actual readings are but let’s say they’re 100 and 200. You can define “onetwohundred” as “100 before the year 2015 and 200 starting from the year 2015” and “twoonehundred” as “200 before the year 2015 and 100 starting from the year 2015”.

Then, “if the object is grue, then the spectrometer reads onetwohundred. On the other hand, if the object is green, then the spectrometer reads onetwohundred before 2015 and twoonehundred starting with 2015″. So you need to know the year to tell whether the object is green.”

that won’t work – blue light is light whose frequency (and therefore wavelength) is between 64k and 72k the frequency of the hyperfine transition of the ground state of cesium, and green light’s is between 56k and 60k – note that these are *fixed*, *time-independent* *pure mathematical functions* of fundamental constants of nature – and therefore they are different from definitions that internally include other things.

What I can say is that it may be the case that I can observe “green” and “blue” and objects are “green” or “blue”, and it may be the case that I can observe “bleen” and “grue” and objects are “bleen” or “grue”, and these two cases describe the same state of reality and the only difference between them is labels, and this common state of reality, by virtue of not having arbitrary time dependence, is more likely than the state of reality that could be described, depending on labeling, as I can observe “green” and “blue” and objects are “bleen” or “grue”, or as I can observe “bleen” and “grue” and objects are “green” or “blue”.

Whether they have arbitrary time dependence is affected by what concepts you consider primitive. If blue and green are primitives, “grue” means “green before 2015 and blue after that”. But if grue and bleen are primitives, “green” means “grue before 2015 and bleen after that”, so you could equally well say that it’s green that has the time dependence.

You could claim that green has no time dependence when described in terms of other things, like spectrometer readings above, but you could rephrase your descriptions of those other things to change the time dependence as well: green causes a onetwohundred reading before 2015 and a twoonehundred reading from then on; green plants die-not-die before 2015 and not-die-die from then on; green is what you get when you mix-don’tmix blue and yellow before 2015 and when you don’tmix-mix blue and yellow afterwards, etc.

If you forget what year it is, you can still tell whether something is green or blue. You cannot, however, tell whether something is grue or bleen.

You observe that something is grue. You can’t tell if the grue object is green or blue unless you know what year it is, since the grue object would be “green” only if the year is before 2015.

Yes you could call “green” “grue” and vice-versa because words are arbitrary identifiers, but if your perception of it doesn’t change at time t the paradox doesn’t happen and you’re just quibbling with words instad of anything interesting

How exactly do you do this if you don’t know what year it is?

What’s this ‘observation of grue’ you’re making? Our eyes observe an instantaneous color, whereas both grue and green (as you’ve defined it) are functions from time to instantaneous color.

Actually, I think verbal ambiguity between instantaneous color and such functions is the source of a lot of confusion here. If we accept that ‘instagreen’ and ‘instablue’ are the things our eyes, and spectrometers, can actually observe, and then define ‘green’, ‘blue’, ‘grue’, and ‘bleen’ as functions, it becomes a fairly straightforward application of induction to apply a gigantic complexity penalty to the hypothesis that something is grue.

Ariel: Still doesn’t work. You could have a concept of “56-64” (which means what we would currently describe as “in a range starting with 56 before 2015 and in a range starting with 64 from then on) and “64-52”, which is the opposite. Then, “grue has a spectrometer reading of 56-64. On the other hand, green has a spectrometer reading of 56-64 before 2015 and 64-56 from then on.”

ADifferentAnonymous: True, but that just means that the reference to instagreen and instablue are subject to the same questioning. Why do you say that your eyes observe instagreen and not instagrue?

Let’s just give the instantaneous colors neutral names, Foo and Bar. These are names we give to the kinds of reports we get from our eyes, and for this reason they are our primitives. We can look at an object and, given no other knowledge, know whether we perceive Foo or Bar.

Now we can define ‘green’ as ‘perceived as Foo before 2015 and perceived as Foo after 2015’ and ‘grue’ as ‘perceived as Foo before 2015 and perceived as Bar after 2015’, and any decent complexity prior will tell us things are more likely to be green than grue.

I suspect that the reason some philosophers take “grue” seriously is because qualia and concepts built upon them are “subjective” and “therefore” (?!??!!!) not part of reality. Once you’ve taken those off the table, there really isn’t any complexity disadvantage for grue and bleen. But then, the complex move is taking our subjective feels and concepts off the reality table.

Many important people do take this logic seriously. Or something kind of like this logic. Though only when applied to things less “clear” than that emeralds are green.

Nassim Taleb always talks about the “Turkey Problem.”

edit: I agree Taleb picked a pretty bad example of a turkey. Maybe he meant a Turkey on a nice farm, where the turkey never sees other turkey’s killed. Though I think his point still has some merit?

Quote: In the book, I have the story of a turkey that is fed for 1,000 days by a butcher, and every day confirms to the turkey and the turkey’s economics department and the turkey’s risk management department and the turkey’s analytical department that the butcher loves turkeys, and every day brings more confidence to the statement. But on day 1001 there will be a surprise for the turkey.”

Throughout anti-fragile he gives advice to “not be a turkey.” As Taleb puts it the Turey got killed just when its confidence in its hypothesis was highest. Taleb is a serious and influential thinker (if a little arrogant).

The other example that comes to my mind is Eliezer Yudkowsky! Every day we get more and more evidence that technology improves human life. Yet Eliezer warns that technology might be a “Black swan” that will one day take away far more than the sum of everything it has ever given. Of course Eliezer was influenced by Taleb conceptually. But Eliezer could be interpreted saying this induction problem is not some minor philosophical point, when the risks are high enough. Just when we have the most evidence for the claim “science improves human life” we all get turned into paperclips!

Though idk how kindly Taleb would view Yudkowsky! Taleb tends to think in a very “old ways are better as they have been vetted by time” scheme. But still Taleb’s economic advice, that if an institution or company has a non-trivial risk of existential failure it is fragile and will not last long can be applied to humanity. And it does not predict us making it very long imo. Though maybe friendly AI will work!

Okay? But say Graham Turnerkey argues to his fellow turkeys that the farmers kill turkeys when they turn 20 weeks old. And then when he and his turkey brethren are 19 weeks old, he goes:

“See? DO YOU SEE? We’re still alive, EXACTLY AS I PREDICTED. Obviously in a week we will all be killed and eaten.”

Now, if turkeys were actually that smart they would be noticing things like:

“This pen is really crappy, how could you say that the farmer cares about us?”

“I saw a turkey who sneaked out of the barn once and he said he was eight years old. Nobody here is even one year old. What the hell?”

“Bob? Bob? Hey, has anyone seen Bob?”

Edit – the ‘Welfare Concerns’ section of the Wikipedia page for domesticated turkeys packs a ridiculous amount of disturbing into very few paragraphs. Yeesh. Any turkey that thinks farmers care about them is definitely not thinking clearly.

Preparing for the unexpected but catastrophic is different from believing that you have increasing evidence that the catastrophic will occur when it fails to do so.

Consider a wife who gets more and more suspicious of her husband as he continues to support her. “See? I predicted he would leave me when I’m old and grey, and him staying with me now that I am middle-aged only proves that I am right about his being a scoundrel!”

Past trends are one source of evidence about what the future will be like, but they are not the only kind of evidence, and they aren’t very strong evidence.

Who’s Yudkowsky!Taleb ? 🙂

Did you use an actual bear population graph for the pre-2015 part of that graph? If so, do you know whether there’s any significance to the odd little jump around 1994, or is that just noise?

The explanation for the small bump around 1994 is that I drew the red line on a somewhat lumpy notebook I use as a makeshift mousepad.

Um, I mean El Nino.

Didn’t know El Nino reached up to your Frozen Glove. 😛

It doesn’t. El Nino makes the weather warmer in South America, which makes more tourists visit from the UK. With fewer people in the UK, fewer of them get mauled by bears.

There are deeper problems here than making up more or less arbitrary ways to continue the lines they’ve graphed. They’re doing that, sure, but even before the collapse the fit is much weaker than they’re making it out to be: all the variables they’re graphing on the population axis are derived more or less directly from birth/death ratios, and all the ones on the economic axis are various restatements of “resources per capita” — which at least isn’t tautologically related, but which breaks down into two variables one of which is directly bound.

In other words, the only interesting part is how the authors choose to relate that resource term and the population term. And since it looks like they’re projecting a bog-standard Malthusian collapse, there’s not too much that’s new or interesting there, either.

I find it amusing as an aside that the Guardian has to point out that Lomborg’s credentials are suspiciously “self-styled”.

I wonder if that is a label he has affixed to himself? His book was the “skeptical environmentalist” , but really, is he a misappropriating the term in the way that is any different from a great many people?

Anyway, good post, although the error you are pointing out is pretty blatant, I should hope.

Really any analysis of the books foresight should focus on the reasons given. There has to be some reason for the inflection points he predicts, and we should be able to better judge whether those reasons are valid as we get closer to that point, even if we can’t necessarily do so based just on the graph. For instance, if he predicted changing birthrates starting in 2020, we should start to see some differences among different age cohorts or geographical regions or something. If he predicted falling oil supplies, we should be able to better judge the date that that would occur now than we would in 1975.

The graphs in and of themselves are the least interesting part of it.

Lomborg gave a TED Talk a while ago in which he recommended not trying to mitigate global warming, and instead using the money on fighting AIDS, on cost-effectiveness grounds. And FWIW, I seem to recall that he gets cited a lot by global-warming-skeptic types making relatively more strenuous attempts to seem reasonable.

I think “self-styled environmentalist” is about as accurate a descriptor for Lomborg as “self-styled feminist” would be for Christina Hoff Sommers: they both present themselves as part of a movement despite disagreeing with a lot of its majority positions.

Well, the Guardian says he is a “self-styled environmental expert”, which sounds to me like they’re doubting not his movement membership but his expertise.

Fair point. FWIW, Wikipedia claims that his academic background is in political science rather than climatology or ecology, and most of his published research listed on Google Scholar is either in game theory or in environmental economics; he doesn’t seem to have published any research on climatology proper, ecology, or the like.

Has he actually called himself an expert, though?

Saying “self-styled” implies that he claims the expertise and does not deserve it, and they don’t back that up.

He certainly has called himself an environmental expert, in precisely those words – or at least his speakers’ bureau has.

(I don’t know how much control people have over their speakers’ bureau profiles, but I’d imagine he at least glanced at that page and OK’d it.)

It’s always made me laugh to hear conservative GOP politicians quoting the work of a gay vegan socialist from Denmark out of context.

More to the point, his argument (and the one of the “Copenhagen Consensus”) is one that should make sense to the sorts around here- our current ameliorative resources are limited, therefore we should find the most cost-effective places to apply them; preferably in ways that generate more productivity than they eat, thus creating additional resources to fight additional problems, ad infinitum…

… and the organization’s math shows us that global warming mitigation efforts just aren’t worth it.

I’m just disappointed that people attack him and his motives rather than digging into his data and refuting his math, while accepting his basic premise, which is one that makes sense to me.

In this case “grue” has a non-arbitrary basis, in the arguments for Limits to Growth, whatever those might be (maybe good, maybe bad, I’m in no position to say.)

Now, this is of course pretty weak (positive) evidence that Limits was right, because of course the simpler (at least simpler hypothesis of continuing secular trends is confirmed just as well. But it is a pretty good basis for rejecting inductive rejections (not rejections operating on a deeper theoretical level) based on the secular trend line. If you published No Limits to Bears in 1970 and someone responded to the bait and said “no bear explosion yet!” that would hardly put your prediction to a grizzly end. I assume this is what whoever it is at the University of Melbourne is saying, and that the Guardian is reporting on it in a predictably clickbaity way.

Ha. Your pun there was a little hard to bear.

I thought so at first, but over time I grue in appreciation of it.

I’m ever so sorry, I don’t bleen you.

I’m much more troubled by the fuzzy thinking Scott used to refute The Guardian.

Should I invest in a multi polar bear trap?