I.

A lot of people pushed back against my post on preschool, so it looks like we need to discuss this in more depth.

A quick refresher: good randomized controlled trials have shown that preschools do not improve test scores in a lasting way. Sometimes test scores go up a little bit, but these effects disappear after a year or two of regular schooling. However, early RCTs of intensive “wrap-around” preschools like the Perry Preschool Program and the Abecedarians found that graduates of those programs went on to have markedly better adult outcomes, including higher school graduation rates, more college attendance, less crime, and better jobs. But these studies were done in the 60s, before people invented being responsible, and had kind of haphazard randomization and followup. They were also small sample sizes, and from programs that were more intense than any of the scaled-up versions that replaced them. Modern scaled-up preschools like Head Start would love to be able to claim their mantle and boast similar results. But the only good RCT of Head Start, the HSIS study, is still in its first few years. It’s confirmed that Head Start test score gains fade out. But it hasn’t been long enough to study whether there are later effects on life outcomes. We can expect those results in ten years or so. For now, all we have is speculation based on a few quasi-experiments.

Deming 2009 is my favorite of these. He looks at the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth, a big nationwide survey that gets used for a lot of social science research, and picks out children who went to Head Start. These children are mostly disadvantaged because Head Start is aimed at the poor, so it would be unfair to compare them to the average child. He’s also too smart to just “control for income”, because he knows that’s not good enough. Instead, he finds children who went to Head Start but who have siblings who didn’t, and uses the sibling as a matched control for the Head Starter.

This ensures the controls will come from the same socioeconomic stratum, but he acknowledges it raises problems of its own. Why would a parent send one child to Head Start but not another? It might be that one child is very stupid and so the parents think they need the extra help preschool can provide; if this were true, it would mean Head Starters are systematically dumber than controls, and would underestimate the effect of Head Start. Or it might be that one child is very smart and the so the parents want to give them education so they can develop their full potential; if this were true, it would mean Head Starters are systematically smarter than controls, and would inflate the effect of Head Start. Or it might be that parents love one of their children more and put more effort into supporting them; if this meant these children got other advantages, it would again inflate the effect of Head Start. Or it might mean that parents send the child they love more to a fancy private preschool, and the child they love less gets stuck in Head Start, ie the government program for the disadvantaged. Or it might be that parents start out poor, send their child to Head Start, and then get richer and send their next child to a fancy private preschool, while that child also benefits from their new wealth in other ways. There are a lot of possible problems here.

Deming tries very hard to prove none of these are true. He compares Head Starters and their control siblings on thirty different pre-study variables, including family income during their preschool years, standardized test scores, various measures of health, number of hours mother works during their preschool years, breastfedness, etc. Of these thirty variables, he finds a significant difference on only one: birth weight. Head Starters were less likely to have very low birth weight than their control siblings. This is a moderately big deal, since birth weight is a strong predictor of general child health and later life success. But:

Given the emerging literature on the connection between birth weight and later outcomes, this is a serious threat to the validity of the [study]. There are a few reasons to believe that the birth weight differences are not a serious source of bias, however. First, it appears that the difference is caused by a disproportionate number of low-birth-weight children, rather than by a uniform rightward shift in the distribution of birth weight for Head Start children. For example, there are no significant differences in birth weight once low-birth-weight children (who represent less than 10 percent of the sample) are excluded.

Second, there is an important interaction between birth order and birth weight in this sample. Most of the difference in mean birth weight comes from children who are born third, fourth, or later. Later-birth-order children who subsequently enroll in Head Start are much less likely to be low birth weight than their older siblings who did not enroll in preschool. When I restrict the analysis to sibling pairs only, birth weight differences are much smaller and no longer significant, and the main results are unaffected. Finally, I estimate all the models in Section V with low-birth-weight children excluded, and, again, the main results are unchanged.

Still, to get a sense of the magnitude of any possible positive bias, I back out a correction using the long-run effect of birth weight on outcomes estimated by Black, Devereux, and Salvanes (2007). Specifically, they find that 10 percent higher birth weight leads to an increase in the probability of high school graduation of 0.9 percentage points for twins and 0.4 percentage points for siblings. If that reduced form relationship holds here, a simple correction suggests that the effect of Head Start on high school graduation (and by extension, other outcomes) could be biased upward by between 0.2 and 0.4 percentage points, or about 2–5 percent of the total effect.

Having set up his experimental and control group, Deming does the study and determines how well the Head Starters do compared to their controls. The test scores show some confusing patterns that differ by subgroup. Black children (the majority of this sample; Head Start is aimed at disadvantaged people in general and sometimes at blacks in particular) show the classic pattern of slightly higher test scores in kindergarten and first grade, fading out after a few years. White children never see any test score increases at all. Some subgroups, including boys and children of high-IQ mothers, see test score increases that don’t seem to fade out. But these differences in significance are not themselves significant and it might just be chance. Plausibly the results for blacks, who are the majority of the sample, are the real results, and everything else is noise added on. This is what non-subgroup analysis of the whole sample shows, and it’s how the study seems to treat it.

The nontest results are more impressive. Head Starters are about 8% more likely to graduate high school than controls. This pattern is significant for blacks, boys, and children of low-IQ mothers, but not for whites, girls, and children of high-IQ mothers. Since the former three categories are the sorts of people at high risk of dropping out of high school, this is probably just floor effects. Head Starters are also less likely to be diagnosed with a learning disability (remember, learning disability diagnosis is terrible and tends to just randomly hit underperforming students), and marginally less likely to repeat grades. The subgroup results tend to show higher significance levels for groups at risk of having bad outcomes, and lower significance levels for the rest, just as you would predict. There is no effect on crime. For some reason he does not analyze income, even though his dataset should be able to do that.

He combines all of this into an artificial index of “young adult outcomes” and finds that Head Start adds 0.23 SD. You may notice this is less than the 0.3 SD effect size of antidepressants that everyone wants to dismiss as meaningless, but in the social sciences apparently this is pretty good. Deming optimistically sums this up as “closing one-third of the gap between children with median and bottom-quartile family income”, as “75% of the black-white gap”, and as “80% of the benefits of [Perry Preschool] at 60% of the cost”.

Finally, he does some robustness checks to make sure this is not too dependent on any particular factor of his analysis. I won’t go into these in detail, but you can find them on page 127 of the manuscript, and it’s encouraging that he tries this, given that I’m used to reading papers by social psychologists who treat robustness checks the way vampires treat garlic.

Deming’s paper very similar to Garces Thomas & Currie (2002), which does the same methodology on a different dataset. GTC is earlier and more famous and probably the paper you’ll hear about if you read other discussions of this topic; I’m focusing on Deming because I think his analyses are more careful and he explains what he’s doing a lot better. Reading between the lines, GTC do not find any significant effects for the sample as a whole. In subgroup analyses, they find Head Start makes whites more likely to graduate high school and attend college, and blacks less likely to be involved in crime. One can almost sort of attribute this to floor effects; blacks many times more likely to have contact with the criminal justice system, and there are more blacks than whites in the sample, so maybe it makes sense that this is only significant for them. On the other hand, when I look at the results, there was almost as strong a positive effect for whites (ie Head Start whites committed more crimes, to the same degree Head Start blacks committed fewer crimes) – but there were fewer whites so it didn’t quite reach significance. And the high school results don’t make a lot of sense however you parse them. GTC use the words “statistically significant” a few times, so you know they’re thinking about it. But they don’t ever give significance levels for individual results and one gets the feeling they’re not very impressive. Their pattern of results isn’t really that similar to Deming’s either – remember, Deming found that all races were more likely to benefit from high school, and no race had less crime. GTC also don’t do nearly as much work to show that there aren’t differences between siblings. Deming is billed as confirming or replicating GTC, but this only seems true in the sense that both of them say nice things about Head Start. Their patterns of results are pretty different, and GTC’s are kind of implausible.

And for that matter, ten years earlier two of these authors, Currie and Thomas, did a similar study. They also use the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth, meaning I’m not really clear how their analysis differs from Deming’s (maybe it’s much earlier and so there’s less data?) They first use an “adjust for confounders” model and it doesn’t work very well. Then they try a comparing-siblings model and find that Head Starters are generally older than their no-preschool siblings, and also generally born to poorer mothers (these are probably just the same result; mothers get less poor as they get older). They also tend to do better on a standardized test, though the study is very unclear about when they’re giving this test so I can’t tell if they’re saying that group assignment is nonrandom or that the intervention increased test scores. They find Head Start does not increase income, maybe inconsistently increases test scores among whites but not blacks, decreases grade repetition for whites but not blacks, and improves health among blacks but not whites. They also look into Head Start’s effect on mothers, since part of the wrap-around program involves parent training. All they find is mild effects on white IQ scores, plus “a positive and implausibly large effect of Head Start on the probability that a white mother was a teen at the first birth” which they say is probably sampling error. Like the later study, this study does not give p-values and I am too lazy to calculate them from the things they do give, but it doesn’t seem like they’re likely to be very good.

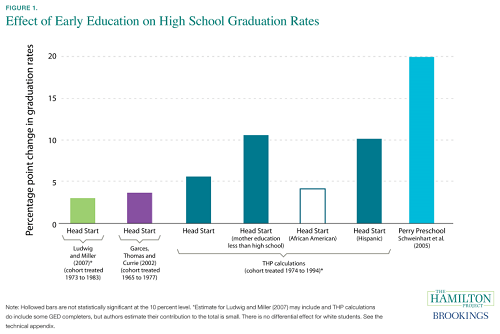

Finally, Deming’s work was also replicated and extended by a team from the Brookings Institute. I think what they’re doing is taking the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth – the same dataset Deming and one of the GTC papers used – and updating it after a few more years of data. Like Deming, they find that “a wide variety” of confounders do not differ between Head Starters and their unpreschooled siblings. Because they’re with the Brookings Institute, their results are presented in a much prettier way than anyone else’s:

The Brookings replication (marked THP here) finds sizes somewhat larger than GTC, but somewhat smaller than Perry Preschool. It looks like they find a positive and significant effect on high school graduation for Hispanics, but not blacks or whites, which is a different weird racial pattern than all the previous weird racial patterns. Since their sample was disproportionately black and Hispanic, and the blacks almost reached significance, the whole sample is significant. They find increases of about 6% on high school graduation rates, compared to Deming’s claimed 8%, but on this chart it’s hard to see how Deming said his 8% was 80% as good as Perry Preschool. There are broadly similar effects on some other things like college attendance, self esteem, and “positive parenting”. They conclude:

These results are very similar to those by Deming (2009), who calculated high school graduation rates on the more limited cohorts that were available when he conducted his work.

These four studies – Deming, GTC, CT, and Brookings – all try to do basically the same thing, though with different datasets. Their results all sound the same at the broad level – “improved outcomes like high school graduation for some racial groups” – but on the more detailed level they can’t really agree which outcomes improve and which racial groups they improve for. I’m not sure how embarrassing this should be for them. All of their results seem to be kind of on the border of significance, and occasionally going below that border and occasionally above it, which helps explain the contradictions while also being kind of embarrassing in and of itself (Deming’s paper is the exception, with several results significant at the 0.01 level). Most of them do find things generally going the right direction and generally sane-looking findings. Overall I feel like Deming looks pretty good, the Brookings replication is too underspecified for me to have strong opinions on, and the various GTC papers neither add nor subtract much from this.

II.

I’m treating Ludwig and Miller separately because it’s a different – and more interesting – design.

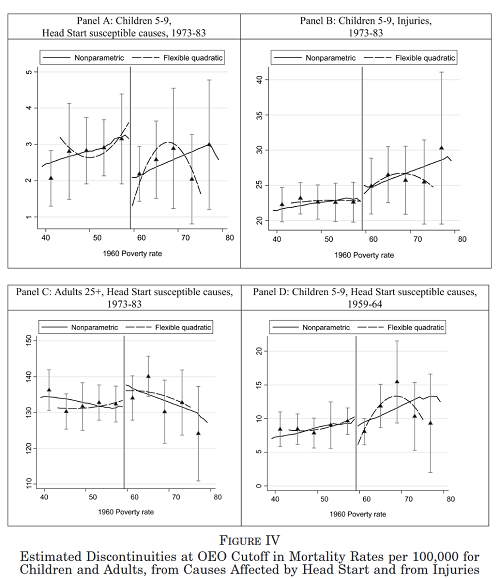

In 1965, the government started an initiative to create Head Start programs in the 300 poorest counties in the US. There was no similar attempt to help counties #301 and above, so there’s a natural discontinuity at county #300. This is the classic sort of case where you can do a regression discontinuity experiment, so Ludwig and Miller decided to look into it and see if there was some big jump in child outcomes as you moved from the 301st-poorest-county to the 300th.

They started by looking into health outcomes, and found a dramatic jump. Head Start appears to improve the outcomes of certain easily-preventable childhood diseases 33-50%. For example, kids from counties with Head Start programs had much less anemia. Part of the Head Start program is screening for anemia and supplementing children with iron, which treats many anemias. So this is very unsurprising. Remember that the three hundred poorest counties in 1965 were basically all majority-black counties in the Deep South and much worse along every axis than you would probably expect – we are talking near-Third-World levels of poverty here. If you deploy health screening and intervention into near-Third-World levels of poverty, then the rates of easily preventable diseases should go down. Ludwig and Miller find they do. This is encouraging, but not really surprising, and maybe not super-relevant to the rest of what we’re talking about here.

But they also find a “positive discontinuity” in high school completion of about 5%. Kids in the 300th-and-below-poorest counties were about 5% more likely than kids in the 301st-and-above-poorest to finish high school. This corresponds to an average of staying in school six months longer. This discontinuity did not exist before Head Start was set up, and it does not exist among children who were the wrong age to participate in Head Start at the time it was set up. It comes into existence just when Head Start is set up, among the children who were in Head Start. This is a pretty great finding.

Unfortunately, it looks like this. The authors freely admit this is just at the limit of what they can detect at p < 0.05 in their data. They double check with another data source, which shows the same trend but is only significant at p < 0.1. "Our evidence for positive Head Start impacts on educational attainment is more suggestive, and limited by the fact that neither of the data sources available to us is quite ideal." This study has the strongest design, and it does find an effect, but the effect is basically squinting at a graph and saying "it kind of looks like that line might be a little higher than the other one". They do some statistics, but they are all the statistical equivalent of squinting at the graph and saying "it kind of looks like that line might be a little higher than the other one", and about as convincing. For a more complete critical look, see this post from the subreddit.

There is one other slightly similar regression discontinuity study, Carneiro and Ginja, which regresses a sample of people on Head Start availability and tries to prove that people who went to Head Start because they were just within the availability cutoff do better than people who missed out on Head Start because they were just outside it. This sounds clever and should be pretty credible. They find a bunch of interesting effects like that Head Starters are less likely to be obese, and less likely to be depressed. They find that non-blacks (but not blacks) are less likely to be involved in crime (which, remember, is the opposite finding as the last paper about Head Start and crime and race). But they don’t find any effect on likelihood to graduate high school or be involved in college. Also, they bury this result and everyone cites this paper as “Look, they’ve replicated that Head Start works!”

III.

A few scattered other studies to put these in context:

In 1980, Chicago created “Child Parent Centers”, a preschool program aimed at the disadvantaged much like all of these others we’ve been talking about. They did a study, which for some reason published its results in a medical journal, and which doesn’t really seem to be trying in the same way as the others. For example, it really doesn’t say much about the control group except that it was “matched”. Taking advantage of their unusually large sample size and excellent follow-up, they find that their program made children stay in school the same six months longer as many of the other studies find, had a strong effect on college completion (8% vs. 14% of kids), showed dose-dependent effects, and “was robust”. They are bad enough at showing their work that I am forced to trust them and the Journal of the American Medical Association, a prestigious journal that I can only hope would not have published random crap.

Havnes and Mogstad analyze a free universal child-care program in Norway, which was rolled out in different places at different times. They find that “exposure to child care raised the chances of completing high school and attending college, in orders of magnitude similar to the black-white race gaps in the US”. I am getting just cynical enough to predict that if Norway had black people, they would have a completely different pattern of benefits and losses from this program, but the Norwegians were able to avoid a subgroup analysis by being a nearly-monoethnic country. This is in contrast to Quebec, where a similar childcare program seems to have caused worse long-term outcomes. Going deeper into these results supports (though weakly and informally) a model where, when daycare is higher-quality than parental care, child outcomes improve; when daycare is lower-quality than parental care, child outcomes decline. So a reform that creates very good daycare, and mostly attracts children whose parents would not be able to care for them very well, will be helpful. Reforms that create low-quality daycare and draw from households that are already doing well will be harmful. See the discussion here.

Then there’s Chetty’s work on kindergarten, which I talk about here. He finds good kindergarten teachers do not consistently affect test scores, but do consistently affect adult earnings, similar to fade-out arguments around preschool. This study is randomized and strong. Its applicability to the current discussion is questionable, since kindergarten is not preschool, having a good teacher is not going to preschool at all, and the studies we’re looking at mostly haven’t found results about adult earnings. At best this suggests that schooling can have surprisingly large and fading-out-then-in-again effects on later life outcomes.

And finally, there’s a meta-analysis of 22 studies of early childhood education showing an effect size of 0.24 SD in favor of graduating high school, p less than 0.001. Maybe I should have started with that one. Maybe it’s crazy of me to save this for the end. Maybe this should count for about five times as much as everything I’ve mentioned so far. I’m putting it down here both to inflict upon you the annoyance I felt when discovering this towards the end of researching this topic, and so that you have a good idea of what kind of studies are going into this meta-analysis.

IV.

What do we make of this?

I am concerned that all of the studies in Parts I and II have been summed up as “Head Start works!”, and therefore as replicating each other, since the last study found “Head Start works!” and so did the newest one. In fact, they all find Head Start having small effects for some specific subgroup on some specific outcome, and it’s usually a different subgroup and outcome for each. So although GCT and Deming are usually considered replications of each other, they actually disprove each other’s results. One of GCT’s two big findings is that Head Start decreases crime among black children. But Deming finds that Head Start had no effect on crime among black children. The only thing the two of them agree on is that Head Start seems to improve high school graduation among whites. But Carneiro and Ginja, which is generally thought of as replicating the earlier two, finds Head Start has no effect on high school graduation among whites.

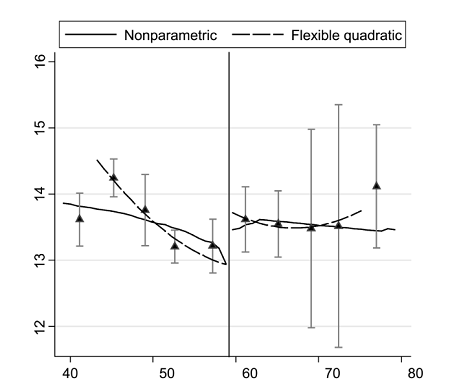

There’s an innocent explanation here, which is that everyone was very close to the significance threshold, so these are just picking up noise. This might make more sense graphically:

It’s easy to see here that both studies found basically the same thing, minus a little noise, but that Study 1 has to report its results as “significant for blacks but not whites” and Study 2 has to report the opposite. Is this what’s going on?

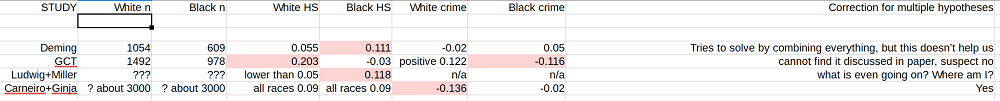

I made a table. I am really really not confident in this table. On one level, I am fundamentally not confident that what I am doing is even possible, and that the numbers in these studies are comparable to one another or mean what it looks like they mean. On a second level, I’m not sure I recorded this information correctly or put the right numbers in the right places. Still, here is the table; red means the result is significant:

This confirms my suspicions. Every study found something different, and it isn’t even close. For example, Carneiro & Ginja finds a strong effect of lowering white crime, but GCT finds that Head Start nonsignificantly increases white crime rates. Meanwhile, GCT find a strong and significant effect lowering black crime, but Carneiro and Ginja find an effect of basically zero.

The strongest case for the studies being in accord is for black high school graduation rates. Both Deming and Ludwig+Miller find an effect. Carneiro and Ginja don’t find an effect, but their effect size is similar to those of the other studies, and they might just have more stringent criteria since they are adjusting for multiple comparisons and testing many things. But they should have the more stringent criteria, and by trying to special-plead against this, I am just reversing the absolutely correct thing they did because I want to force positive results in the exact way that good statistical practice is trying to prevent me from doing. So maybe I shouldn’t do that.

Here is the strongest case for accepting this body research anyway. It doesn’t quite look like publication bias. For one thing, Ludwig and Miller have a paper where they say there’s probably no publication bias here because literally every dataset that can be used to test Head Start has been. For another, although I didn’t focus on gender or IQ on the chart above, most of the studies do find that it helps males and low-IQ people more with the sorts of problems men and low-IQ people usually face, which suggest it passes sanity checks. Most important, in a study whose results are entirely spurious, there should be an equal number of beneficial and harmful findings (ie they should find Head Start makes some subgroups worse on some outcomes). Since each of these studies investigates many things and usually finds many different significant results, it should be hard to publication bias all harmful findings out of existence. This sort of accords with the positive meta-analysis. Studies either show small positive results or are not signficant, and when you combine all of them into a meta-analysis, they become highly significant, look good, and make sense. And this would fit very well with the Norwegian study showing strong positive effects of childcare later in life. And Chetty’s study showing fade-out of kindergarten teachers followed by strong positive effects later in life. And of course the Perry Preschool and Abecedarian studies showing fade-out of tests scores followed by strong positive effects later in life. I even recently learned of a truly marvelous developmental explanation for why this might happen, which unfortunately this margin is too small to contain – expect a book review in the coming weeks.

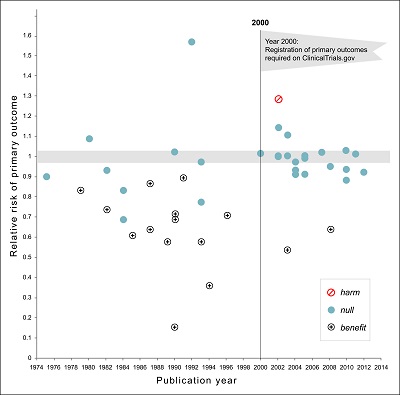

The case against this research is that maybe the researchers cheated to have there be no harmful findings. Maybe the meta-analysis just shows that when a lot of researchers cheat a little, taking care to only commit minor undetectable sins, that adds up to a strong overall effect. This is harsh, but I was recently referred to this chart (h/t Mother Jones, which calls it “the chart of the decade” and “one of the greatest charts ever produced”):

This is the outcome of drug trials before and after the medical establishment started requiring preregistration (the vertical line) – in other words, before they made it harder to cheat. Before the vertical line, 60% of trials showed the drug in question was beneficial. After the vertical line, only 10% did. In other words, making it harder to cheat cuts the number of positive trials by a factor of six. It is not at all hard to cheat in the research of early childhood education; all the research in this post so far comes from the left side of the vertical line. We should be skeptical of all but the most ironclad research that comes from the left – and this is not the most ironclad research.

The Virtues of Rationality say:

One who wishes to believe says, “Does the evidence permit me to believe?” One who wishes to disbelieve asks, “Does the evidence force me to believe?” Beware lest you place huge burdens of proof only on propositions you dislike, and then defend yourself by saying: “But it is good to be skeptical.” If you attend only to favorable evidence, picking and choosing from your gathered data, then the more data you gather, the less you know. If you are selective about which arguments you inspect for flaws, or how hard you inspect for flaws, then every flaw you learn how to detect makes you that much stupider.

This is one of the many problems where the evidence permits me to disbelieve, but does not force me to do so. At this point I have only intuition and vague heuristics. My intuition tells me that in twenty years, when all the results are in, I expect early childhood programs to continue having small positive effects. My vague heuristics say the opposite, that I can’t trust research this irregular. So I don’t know.

I think I was right to register that my previous belief preschool definitely didn’t work was outdated and under challenge. I think I was probably premature to say I was wrong about preschool not working; I should have said I might be wrong. If I had to bet on it, I would say 60% odds preschool helps in ways kind of like the ones these studies suggest, 40% odds it’s useless.

I hope that further followup of the HSIS, an unusually good randomized controlled trial of Head Start, will shed more light on this after its participants reach high school age sometime in the 2020s.

> I would say 60% odds preschool helps in ways kind of like the ones these studies suggest

But… costs. In the end, betting that years of effort help “somewhat” is really “duh” territory. Are they even close to recouping costs, including opportunity ones?

Are you seriously interested in this question or are you using it to avoid engaging with the evidence and to reinforce your prior?

I submit that a useful way to distinguish the two would be whether you made a serious effort to find out whether that question is addressed in the literature.

> Are you seriously interested in this question

Government spending is full of programs that may have a benefit but where the costs outweigh the benefits. I don’t see why someone needs to justify asking what is the cost benefit.

This is even before noting (per SSC) that these studies were not pre-registered. So discount by a factor of 6. They had so many degrees of freedom that the reported P values are almost certainly exaggerated.

And a meta-analysis based on cherry picked stats is also highly suspect.

They do, when they raise the question as an objection, i.e. pretend to care about this, as in, pretend it is relevant to their overall take on the matter while apparently having spent so little time on the question that they can’t even reach a tentative conclusion on it’s factual state.

If it was a totally neutral query, sure, that’s perfectly legit, but that’s not what the comment was.

As for pre-registration and the meta-analysis, did you miss the part where Scott said that both every outcome and every conceivable dataset had been looked at in the context of these interventions? (Also, FWIW, if you take the factor 6 from the post above, I think that’s a misinterpretation of the cited paper by Scott based on the poor discussion in the paper. I’d love to discuss Likelihood of Null Effects of Large Clinical trials (https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0132382) in the next OT, but think it would be a distraction here.)

also @brmic:

I don’t usually find a lack of knowledge to be evidence against neutrality.

What’s the ninth largest country by landmass divided by population? I have no idea, largely because I don’t really care. If you said it was Antarctica, though, I’d be dubious, just on priors.

I think what you’re talking about is a real thing, but I don’t see a lot of reason to think that’s what’s happening here.

At a mild tangent: my prior is that people often forget to weigh all the advantages and disadvantages, and that taxes are sometimes a particularly fertile area for this. I think my natural inclination is to be pro-schooling- it benefits kids, it seems like it might get us a more rational population- but when I see an article about whether we should be doing it or not that makes no mention of costs, alarms go off. It’s half legitimate quibble, half local validity thing.

I don’t really care who raises the question of cost, or for what motive, but I am happy that someone does so between suggesting a policy and deciding if it is worth doing.

This seems unnecessarily argumentative. I believe what he’s saying is that even if you charitably accede that the research is correct in showing a small positive net benefit on outcomes that it is still probably not worth it vs. e.g. simply giving the parents money, or even possibly doing nothing at all. I’m unsure what “avoid(ing) engaging with the evidence” could add or subtract here.

It would add _at the very least_ the requirement that you check the papers linked for whether any of them addresses the question.

You’re doing the same thing without noticing it here: ‘probably not worth it’. You don’t know, you haven’t run the numbers, you don’t even have a position on someone else’s report of having run the numbers. You just moved your bias one level up.

This is very bad epistemiology for a rationalist comment section.

As mentioned above, I think it’s fine to ask a truly open question. It’s fine to disagree with the available analyses, to find fault with them, to point to other analyses with different results. But if you haven’t done an analysis, and haven’t read one and still assert what it’s outcome would likely be, you’re using your biases, not your ratio to come to that conclusion.

Reading through the thread, I wasn’t really with you until this line. I didn’t especially disagree with you either, but I wasn’t fully persuaded. More that I sort of got what you were getting at, but some of the critiques levied against your position seemed valid too.

But this is a really good point. The manner of delivery indicates biased skepticism in a way that you have very elegantly explicated; hats off to you.

Ok, I get where you’re coming from now. I concede the general point. In this specific case, we’re talking about a massive federal program. My wife and I both work in government (she in social services) and I (in rationalist parlance) have a high prior that unless this program provides a significant benefit it couldn’t possibly justify the cost of its existence (although, again, as a rationalist I’m open to the idea of the data saying otherwise).

@brmic:

In his defense, asking Scott has proven to be a reliable low-effort alternative to looking things up. I kind of had the same question, tbh.

I think there are a lot of things I care enough about to ask a smart friend, but not enough about to research them on my own.

The utility of looking for yourself varies a lot, at least mine does; if I expect to find the answer on my own, it’s often worth it, but if there’s just a hole where the answer should be… then there’s never a clear point where it’s time to stop looking, which is stressful, and ever after I wonder if I should have looked longer.

That approach particularly suggests itself when you’re commenting on a post in which Scott bemoans the difficulty of wringing out of the literature even a tentative conclusion about whether the programs produce any benefit at all. If the studies point every which way on that question, it would be surprising if they gave a definitive answer on cost vs. benefit.

In Radu’s defense, at the end of the previous post on Preschool Scott made a policy recommendation. But since, Scott did not revisit that recommendation here I read it as a legitimate question part of the larger conversation we are having about preschool.

There is no rule here that every comment has to be a comment directly related to the OP.

On the other hand, Radu’s post comes across as needlessly inflammatory and low-effort ‘whataboutism.’

One identified intervention that makes a lot of sense (at least in the 1960s) was basic medical screening. That’s gotta be a whole lot cheaper than daily care and teaching, and would cover one of the strongest results from any of the studies.

But they are two entirely different questions. “Does preschool help kids?” vs. “Is the cost of preschool worth it?”

The post is long enough as it is. And answering the second question would require a deep-dive into economic and political philosophy. Questions of taxation, political feasibility, and weighing moral values against each other.

It’s better just to answer the first, smaller question, and use the results to update whatever preexisting political philosophy you have.

That’s true if you are trying to evaluate whether it’s better to spend an extra dollar on preschool or lower taxes by a dollar. But it’s not so true if you’re trying to decide whether to spend a dollar on preschool or a give a dollar cash transfer or spend a dollar on some health intervention or spend a dollar improving public high schools.

Most of these objections to Radu’s question imply that questioning the efficacy of preschool is some kind of de facto red tribe position. It can be. And it can be something entirely different. For one thing, one of the reasons that universal preschool has such widespread political support is that people tend to view children as innocent and, therefore, want to believe that they ultimately malleable.

It can sometimes be much easier to get people to approve of public programs aimed at very young children than to support interventions for older children, in part, because people tend to believe that older children have already made their choices and are irredeemable. Personally, I think it is worth the time and effort to find out how true these assumptions really are.

What you’re calling “duh territory” is what I said I can only be 60% sure of at this point, and what many commenters on the last post denied entirely. I think your intuitions here are different from other people’s.

Many of the studies I linked, including Deming, included cost-benefit analyses purporting to show that benefits exceeded costs at the effect sizes they found. I wasn’t as interested in these because I am more focused on the academic question of what affects early childhood development, but you can take a look at them if you want.

If the results are correct, and it inceases high school graduation rates by 8%, then it’s worth the cost just from that alone.

https://www.ssa.gov/retirementpolicy/research/education-earnings.html

High school graduates earn about $400,000 more over a lifetime than people who don’t finish high school. 8% of that is $36,000 per student. Head start only costs about $7600 per student.

There are a lot of other likely benefits here as well, lower crime rate is also a big deal, poor parents probably earn more if they have child care, ect. If you agree there’s a 60% chance it raises high school graduation rates and a 60% chance it reduces crime it’s a good investment.

Head start costs that up front though, $7,600 compounded for 65 years at 5% is $180,000 and at 7% is $620,000

That may be overstating the benefit. Assume that Head Start achieves its result by turning marginal dropouts into marginal graduates: marginal dropouts probably earn more on average than the entire population of dropouts, while marginal graduates probably earn less on average than the entire population of graduates.

True, but Head Start presumably also turns median dropouts into superior dropouts, and marginal graduates into median graduates, which will both be associated with some increase in earning potential. Very roughly speaking, an 8% increase in graduation rates means that everybody moves up an average of 8% of the “distance” between zero and minimal high school graduation

If you can’t measure at that level of detail, assuming that a flat 8% (or whatever) jump directly from “average dropout” to “average graduate” is a statistically reasonable approximation of the full effect; assuming that the benefit was only experienced by the top 8% of dropouts is not.

But, accounting for the time value of money, Head Start is still looking like a very marginal proposition and we should also be looking at other things we could be doing better.

As the article says, “These children are mostly disadvantaged because Head Start is aimed at the poor”. I don’t think “average dropout” to “average graduate” is a reasonable assumption for such selected population; “average dropout” to “minimal graduate” seems like a better starting assumption (high end of graduates is still going to be rare even after the program).

The possibility being suggested, if I’m understanding it right, isn’t that the average dropouts get upgraded directly to average grads– it’s that they slide over to take the place of the somewhat-better-than-average dropouts, who in turn take the place of the just-missed-graduating, and so on up the chain, so that the net effect is the same as if the people at the bottom end leapfrogged to the top while everyone else stood still. It’s possible, though speculative (we’re no longer talking about a direct benefit from increased graduation rates, but rather using the increase as a proxy for benefits to people whose graduation status hasn’t changed).

One detail I missed at first which adds a bit of plausibility to the case for preschool: the $400,000 improvement in earnings is based on the median for high-school graduates with no further educational attainment— not for all high-school graduates. That’s a more reasonable example of something current dropouts might aspire to with a bit of help.

@Paul Zrimsek:

But the studies didn’t say that academic performance would improve noticeably, so I assume it’s just that people choose to continue education even though they aren’t doing particularly well. This effect clearly produces more low-quality graduates.

Even if you assumed that academic performance or even IQ were boosted directly, if the shapes of the distributions for the poor population and others were anything like normal distributions, boosting the inferior population to a better-but-still-inferior level would still increase the graduates proportionally more at the worse-than-average level.

Individual return isn’t the same as social return.

And individual cost isn’t the same as social cost.

The child not being at preschool also has significant oppurtunity costs, since the alternative is normally one parent being at home with them and not working. So even if the value of preschool for the child is negligible it can be beneficial through higher parental earnings (both during the time they’re in preschool and in the future from better job experience). Which is good for the family as a whole, and probably for the child given all the well known positive outcomes of more money

You should probably alter this line:

before someone takes it out of context.

Too late, I’m already doing that.

Very obviously, research which is plausibly politically-biased should be scrutinized severely, but only doing this for one side just moves the problem up a level.

“On the left” did not refer to politics here. It referred to being on the left side of the line in the provided chart, in other words, studies before the year 2000.

Yes, I know; I thought Incurian was referencing the political misreading.

I was gonna say the same thing – I misread the line at first and was surprised by it.

I missed that. My first straussian reading of this post was not to believe any of this week’s update posts, but this suggests a different reading.

Just to clarify for anyone who forgot: ‘The left’ here refers to studies before the year 2000.

So it’s “the left” that’s the real conservatives?

😛 Straussian Conservatives

I half-suspect it was intended as bait, just to see who bites.

Hmm…still skeptical.

Okay let’s assume head start and preschool produce tiny but statistically significant later gains in life among some blacks and maybe some Hispanics. Is it worth the cost. If slightly boosting high school or college attendance is considered a success, then there are probably cheaper and more effective ways of doing that (such as giving high school grads $10 to apply to college). It sorta seems like goalpost moving: your program fails to do what it was originally intended, but because there are are some tiny secondary gains later in life if one looks hard enough, that justifies keeping the program. It’s like saying the Iraq war failed to find anything or create peace and it cost trillions of dollars, but because it boosted the sale of patriotic bumper stickers, it is worthwhile.

In fact, the goalposts were moved for the Iraq War. The original impetus was to protect the US from weapons of mass destruction. After we sent in the military, wasted pallets of cash, and discovered no weapons of mass destruction, we patted ourselves on the back for freeing the Iraqi people from a dictator. Would we have spent so many lives and resources if the original goal was to depose a dictator? Assuredly not.

This is inaccurate. that was, at most, the most noisy justification of the war. the goal, and virtually every book written on the bush administration agrees with this point, was to get rid of nasty despots in the middle east and replace them with democracies in order to drain the swamp of terrorism. And this goal was achieved, to a remarkable degree. It took several years longer, and about a trillion dollars more, than was originally anticipated, but it was achieved.

Yes, the middle-east is a bastion of America loving democracies now…mission accomplished.

Also, that may have been the administration’s goal, but that is not how it was presented or justified to the public.

They didn’t do the whole middle east. they did iraq. And Iraq is a democracy, the only one in the arab world.

Yes, it was. WMD was only one of many arguments explicitly articulated by the administration, one that feels louder in hindsight than it actually was becuase of the unexpected failure to find any meant that critics could hammer them on the point.

Cass, I am a bit young to fully remember the political debates about whether we should have gone into Iraq, but my memory is that WMD was reason #1 and reason #2 was a distant second.

If this wasn’t the case, then there is a real problem with the military strategy for the war. People love to tout “the surge” etc at the end of the Bush years, but if you wanted democracy, you needed to not just take out Saddam and the Royal Guard, you needed to take POWs and keep them encamped for a few years, you needed to bomb “strategic locations” in cities (aka any plausible target you can find without explicitly admitting you are committing a war crime) and start from day 1 with a robust propaganda and iron first (aka counterinsurgency) campaign.

The article you linked seems to imply that WMD was indeed the primary (but not only) argument going into the war, but then subsided as evidence that WMDs were there subsided. I feel like this detracts from your point rather than supports it.

I second what acymetric said. This was the face of the administration’s case for the Iraq War: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/United_Nations_Security_Council_and_the_Iraq_War#Colin_Powell's_presentation

Of course they downplayed the WMD angle and Iraq’s role in supporting terror and tried to shift focus to democratization as the first two proved… elusive.

Also, I would take a closer look at Iraq’s current democracy and then ask some serious cost-benefit questions before declaring the Iraq War a success.

It’s also worth pointing out that everyone believed that Iraq did have WMDs. Including Saddam, probably. If he didn’t have the things, why did he play games with the UN weapons inspectors? Maybe he wanted us to believe he did, but at this point, all you’re saying is that he fooled the CIA. Which isn’t impossible.

@bean, The easy explanation for why he played games with the weapons inspectors is that he wanted his local rivals to believe he had WMDs.

idontknow131647093

Their strategy was to pull a massive scale version of the invasion of grenada. the thinking was that the best way to prevent an insurgency was to get in and out as quickly as possible with as little an occupation as possible. It clearly didn’t work, and I’m much more inclined to the method that you describe, but that was the plan.

@acymetric

the evidence they present shows that in the beginning the two biggest reasons for the invasion were WMD and internationalism, with internationalism slightly more important. Both those arguments start to decline in importance before the start of the invasion, at about the same time the freedom/democracy argument starts its upwards trajectory. the WMD argument drops out long before it’s apparent that there were none.

@Protagoras

I tend to agree with you. the best place for saddam to be was to not have any WMD, because then no one could ever find them, but to have everyone convinced he had them, so they would all still be afraid of him.

Just to point out the dog that didn’t bark here – none of this affected IQ.

The original premise was that IQ variance was environmental, but big changes to environment made no difference.

I’m a stranger to this debate, so I’m unaware of the background. What do you mean by “the original premise”?

This isn’t quite right; low birth weight (proxy for general healthiness) correlates with IQ and is affected by Head Start participation; low birth weight is associated with up to 10% lower IQ, although as the authors of the linked meta-analysis note this is really hard to study in isolation. I don’t believe anybody did the kind of subset analysis which would detect this at the population level.

“low birth weight (proxy for general healthiness) correlates with IQ and is affected by Head Start participation”

How exactly is a person’s birth weight determined by something that happened after their birth?

Head Start did not affect the birth weight. Head Start was just disproportionately attended by kids with a low birth weight.

The summary said the opposite, that low birth weight kids avoided HS disproportionately.

This is probably the most interesting point not yet discussed. I would have guess the opposite, if you had a low birth weight child with issues wouldn’t you be more aggressive in seeking out help, not less? The mechanism for selecting against low birth weight should be discussed (it also is possibly a coincidence since he looked at 30 variables and found 1 that was significant in a P-hacking sort of way).

Early Head Start includes perinatal medical care and education.

It seems very unlikely that pre-school could have an effect which was race-dependent in any fundamental way. Where there are observed differences in outcomes between racial groups that is presumably because race is a proxy for something else (like poverty), but that relationship will be inconsistent across time and space. Might that explain the inconsistent outcomes by racial subgroups? I don’t really understand why the data is being analysed in this way.

That’s a fashionable but difficult pre-supposition (that race is only a proxy for e.g. poverty).

Maybe there are important genetic differences between races (I’m not convinced there are, but can’t rule it out a priori). Maybe the cultural impacts of racism and colonialism are strong enough that they last for generations after colonialism is dead and overt racism is rare (my hunch says yes to at least this one).

Or maybe you’re right but it’s moot: race is a proxy for culture but the cultural influences are so pervasive that it might as well be a thing, and unlike poverty this would be more stable over time (or rather would require a longer timescale to show meaningful change).

Or maybe your just plain right: it’s a reasonable guess. But I have a lower prior for that viewpoint than it’s popularity would suggest.

But race is also a proxy for cultural impacts. Nigerian immigrants from the 90s did not have ancestors that suffered from discrimination in America.

Race is also a proxy for culture. Not all hispanics are cultural hispanics. Not all cultural hispanics are hispanic.

Skin color is about the least likely attribute to have a direct effect on any but a very small set of outcomes, like skin cancer. While it’s among the easiest attributes to measure, wouldn’t it make sense to invest a little more effort in singling out attributes that actually matter, like poverty, genealogy, and culture?

Race is more than skin color. Lots of tan white people are darker than lots of Asians, Hispanics, even blacks

It depends.

How strong is the correlation? Is it like lung cancer and smoking strong? Because if it is, we might as well just talk about race like it’s a thing. If it’s not, it’s probably worth the effort to find better categorizations.

I’m reminded of all the SSC posts on IQ. People keep wanting to talk about different kinds of intelligence, and maybe there are, but that doesn’t mean IQ isn’t a thing.

Maybe it’s just time to pick a word that doesn’t have as much baggage. Have we loaded up “ethnicity” with negative affect yet?

They controlled for poverty in the studies, which is why they were even taken seriously.

I want to gripe at you slightly for your bad habit of citing organizations instead of people; here, “h/t Mother Jones, which calls it “the chart of the decade”” instead of “h/t Kevin Drum” or if you really feel the organization is important for some reason “h/t Kevin Drum at Mother Jones.” Kevin Drum is a blogger. His opinions are not necessarily those of Mother Jones, and vice versa. There is no sense in which “Mother Jones” is calling this “the chart of the decade” – that is Kevin Drum’s opinion only.

You can say it’s Mother Jones’ opinion if it’s in a staff editorial.

It’s not quite the same thing but you would immediately see the problem if someone pointed at an opinion you wrote on LessWrong and attributed it to “LessWrong” instead of “Scott Alexander.”

I am doing this on purpose, because I often criticize people and I don’t like it to sound like personal attacks.

I really enjoy posts like this and find them very interesting.

While I enjoyed the post, I’m not sure what I’m supposed to think about the effect of preschool now. This could just have well been titled “Preschool: ¯\_(ツ)_/¯”

I think that works sufficiently well as an emoji for “Much More Than You Needed to Know” posts.

I got the same result, but one thing I like about Scott is that he publishes his “I don’t know” posts that other people would not, avoiding the file-drawer effect.

But what is preschool from what age and what are the alternatives to it? I mean in my country daycare/kindergarten/preschool/whatever you want to call that thing that happens between the ages of 2 and 6, is mostly about letting women go back to the workforce after 2 years of maternity leave. And if the kids are there anyway, they might as well try to teach them something but that is kind of secondary.

Only the last year, when they are 5 years old, called the school preparation year is where some more formal teaching takes place. It is the only year that is mandatory, the earlier not. Is this the preschool in the US sense, is this what Scott is writing about?

What is actually being done there? Here it is stuff like improving speech and speech understanding abilities, teamwork abilities etc.

What is the alternative to preschool in the Scott sense? Staying at home sitting on mom’s skirt until school? Sounds like bad socialization, no relationship with other kids and losing much of the workforce. Be in a kind of daycare or kindergarten but learn nothing, just play all day? Sounds like a waste of time. Why shock kids with school being totally different than daycare instead of having a gradual transition?

So what exactly is the no preschool scenario?

Same here. In my country they go to school at 7, and 6 is the school-preparation year.

I think in the US what they call pre-school is systemtically teaching things to 3 and 4-year-olds.

What is the alternative to preschool in the Scott sense? Staying at home sitting on mom’s skirt until school? Sounds like bad socialization, no relationship with other kids and losing much of the workforce. Be in a kind of daycare or kindergarten but learn nothing, just play all day? Sounds like a waste of time.

These are not at all agreed upon, as I understand. It may, for example, be better to learn socializing from the grown-ups, since they are the ones who actually can socialize in a polite, pro-social manner. From the other kids you can learn how to be obnoxiously selfish and break down in tantrums if something bothers you (I don’t really mean that you can’t learn anything useful from playing with other kids).

Also, sitting on mom’s skirt feels very safe, while going to a large group of strangers can feel real unsafe (you can see how some kids desperately cling to their parents, crying and begging, when they are being dropped off at the daycare). There are suggestive differences in child cortisol levels between daycare and no daycare days, for example. Feeling safe can plausibly be connected to good life outcomes.

Plus we cannot deny that children had plenty of relationships with other kids before daycare became widespread, so daycare is not necessary for that. I suppose the one most important benefit of daycare is letting the mothers go to work.

Aside from that, playing all day is probably not waste of time, play is how young kids naturally learn, right?

At least in mathematics, per Benezet formal education before sixth grade is completely unnecessary at best and may be actively depressing population adult outcomes. So, yeah, fractions for toddlers are probably not a great idea.

Cortisol levels: well, our kid certain screams every morning that she does not want to go to kindergarten. And yet if we are on a holiday after 2 days she says she wants to. Just like how she is screaming every evening she does not want to take a bath, and then enjoys it so much she does not want to get out. So don’t know which version of her should I believe.

She has a weird love-hate relationship with a classmate. She sometimes says he bullies her, name-calling, and yet always looking for him and wants to play together. But I know that a bit of aggressive behavior is not alien from her either (whe she is tearing at her mothers breasts at full force, it is really hard for her to stay principled and not slap her), so I asked the boys parents and yeah there were some complaints about she bullying him as well. Again don’t know what to believe.

In the US, most kids go to Kindergarten when they’re 5, and that’s part of the standard schooling system. Preschool is something offered before that, usually from 3-5 years of age, and is not required and generally not free. Head Start is a free preschool program for 3-5 year old children from low-income families, and there’s also a program known as Early Head Start that helps provide health and educational services for low-income kids younger than that. The no-preschool scenario for low income families usually mean that the mother or other family members (often grandparents) take care of the kid. Sometimes the kid goes to a community or church-based daycare center, but I think this is less common. In some cases, there isn’t one person who can consistently take care of the child, so kids are sent to whatever relative or community member can currently do it. So, as Scott and Kelsey have both mentioned in their articles, the effects of preschool in the US may be related to providing any kind of consistent childcare environment, as well as giving the mothers better employment options. Any formal education preschools provide is probably irrelevant.

Also, this is a tangential point, companies in the US are only required to offer 12 weeks of maternity leave, and this is often unpaid, especially for low paying jobs. 2 years of maternity leave is unheard of there, and there are extremely few free childcare options. This may be more relevant to the first couple years of life rather than preschool, but it might give context for what the “no preschool scenario” means.

“2 years of maternity leave should be the standard!” (turns around) “wait, you want to code in Ruby On Rails? What the fuck, lady, you think it’s still 2016?”

????

This is a weird reply. I wasn’t proposing that two years of maternity leave should be standard. It probably shouldn’t, though 12 wks unpaid leave probably shouldn’t either. Also, not sure that female developers are the most relevant to a discussion more focused on low income childcare options.

FWIW, in most countries that have 2 years, a lot of women in tech and other more competitive jobs don’t take that full period. Also, US women in tech don’t tend to be the people choosing between 12 weeks unpaid leave or nothing, they generally have at least slightly better benefits provided by their employers. Tradeoffs between parental leave and ongoing training/job experience are worth talking about, but kind of a different topic of conversation.

This is an elitist viewpoint, Silicon bleedin’ edge Valley. Most websites in the world are still programmed in PHP and Asp.NET. In the comfy mediocre tepid company I work at, the average company, we are considering rewriting Asp .NET web forms in ASP.NET MVC. Don’t know the exact numbers but it is like replacing 2002 tech with 2012 tech? Roughly that.

An elitist viewpoint? Maybe. But it’s not especially uncommon, and it’s not something that’s being pushed by Evul Kepitelist Bosses to exploit the poor downtrodden workers.

Elitist was probably a bit of a loaded word to use there…but your position definitely does not apply to the majority of coding jobs available out there (which I think is what nameless1 was getting at). It might apply to the best coding jobs, but even that probably isn’t universally true.

As a Euro I don’t think maternity leave is a big deal. I get job offers from the US with much higher pretax and basically 2x as much posttax pay. So if my wife was at home for unpaid instead of paid €660 per month by the state as maternity leave (our rent + utilities is €850 so it is not a lot of money) but I would earn much more, it would be the same thing.

I admit I think mostly conservative about this: families of 2 parents + kids, pooled income, one budget, it is entirely irrelevant if the income is dad earning a lot or maternity leave or tax breaks or whatever title it has.

Matters more for single moms, but looking my above numbers… well at least it does not encourage family breakups much.

Another thing is really that you cannot leave a kid in a kindergarten for 9 hours. Too stressful. So one parent will have a part time, 5-6 hour job and pick them up at 15:00. Due to social, biological or whatever reasons, the typical gender role is here the old one: dad is working his ass off to make a career, mom has more just a basic job than a career because you cannot career in 5-6 hours a day.

A good number of double income families get around this by having one parent start work early and get out early and one parent start work late and get out late.

What do you mean by “a good number”? I suspect that a large majority of 2-income households do not have that kind of flexibility with their work hours.

You guys could just Google an empirical question like that. Most sources I just came across in 2 minutes of searching indicate that between 27 and 30 percent of workers in the United States have access to flex time. It would appear that you’re both right: “A good number of families” do get around this; while “a large majority” do not.

As a parent, I can tell you that a lot of us address this issue by making use of after-school programs.

About half of the 2 income families that I know do this. You only need one flexible schedule, the person working 9-5 drops off and the one who works starts between 7 and 8 picks up.

This is hard in an office if the office hours are 9 to 17. But this is precisely why my wife is orienting herself towards logistics. Warehouses tend to be early birds, sending trucks out at 5:00 to get into the shops before opening.

Now there are people who get ready in 10 minutes in the morning. We are not that kind of people. More like 90 minutes with several coffees and phone browsing. And if it takes a hour to load the truck she would get up a 2:00, go to sleep at 18:00. The kind of marriage that guard sergeant had in Terry Pratchett’s Guards! Guards! mostly conducted through post-it notes.

So dunno what exactly are going to do to be honest.

This doesn’t give us much of an answer though. What you need is for a pair of parents to have enough differences in their schedules to make pick up and drop off work, not “flexibility”. It could be that flex time is common for certain demographics where both partners have it, and then the 37% means more like 18% of households have it, or it could be common for one partner to seek it out and then up to 74% of

(dual income) households have it.

But flex time really doesn’t cover it, not all flex time is flexible enough, and no flex time is needed in many situations. One couple I know both work for the same large company, one is a manager in the warehouse, and is a manager in procurement. The first is at work before 6am, the other at work until 6pm, neither needs flex time to make it work.

Daycare and preschool are separated by how many formal activities there are. Preschool has a few formal activities. Daycare has informal activities.

Not completely sure about this next bit, but I think preschool also has a higher adult-to-child ratio than daycare. Meaning more individualized attention, which has always been shown to increase outcomes for students.

Regarding the Mother Jones chart: I feel like their sensationalist headline is not sensationalist enough:

Doesn’t the chart mean that we cannot trust ANY medical reasearch that came out before 2000, and by extension ALL drugs and treatments approved before 2000? And by even further extension, all research from any field that was not preregistered?

If science was a factory, seeing this chart should make the foreman stop all conveyor belts because of production defects.

Prior to Preregistration Of Primary Endpoints, the study method was “do a study, look at the data, find something that the data will support, pretend that thing was your primary endpoint all along and publish your study”

After Preregistration, if you didn’t hit the original goal of the study then it was Null Result no matter what else you found.

It’s not “everyone prior to Y2K was LYING”, despite what MoJo is telling you so that you’ll click on their website and look at the ads.

Now, if you want to say “these studies may not have had enough data to confidently identify the effect they claim to have found, and if they’d been looking for that effect then they *would* have collected that much data” then you’re certainly right to say that. But this whole thing is being presented like some Freakonomics bullshit–“every science study ever done is WRONG!!!!”.

Drug research is different from drug approval. Drug approval is based on research, but it is preregistered and the analysis is performed by the FDA. Also, it’s illegal for drug companies to show any other research to doctors.

See https://slatestarcodex.com/2013/02/17/90-of-all-claims-about-the-problems-with-medical-studies-are-wrong/ for my previous discussion of this.

No, not at all. You should update in the direction that some past results were/are overly optimistic, and that standards have improved and are still improving.

I think the study itself is mediocre and a bit sensationalist, and Kevin Drum’s treatment of it is awful.

To list just a few criticisms:

– The scatterplot suggests a triangle to me, consistent with lower hanging fruit being picked. But more importantly, I simply don’t see the discontinuity except in that there a few studies right around the cut point.

– If you check sample sizes you’ll find that the pre-2000 results represent a total sample of 57k, with 22k of those coming from one study. The post-2000 sample size is 232k, so 4 times the pre-2000 sample size. This suggests a very simple explanation, namely that the pre-2000 results have a file drawer problem, coupled with the statistical necessity of anything significant in small samples being an overestimate. At any rate, the authors don’t discuss this.

– However, they say they focussed on large scale trials with annual costs over $500,000, and that almost all of these are published, so file drawers are not an issue. Aaaah, yes. That’s were the list of sample sizes comes in again: Head to table S2, and find e.g. the FISH OIL study: 9 participants in both groups, and this supposedly cost over 500k? Let’s check the publication: https://academic.oup.com/ajcn/article-abstract/57/1/59/4715542 (there’s another fish oil study from the same year with different authors but similar sample size). Couple things come to mind: (1) if this cost over 500k/year, I’ll eat my hat. (2) This is not a ‘large scale trial’ by any measure. If this is really that expensive, expect lots of similar studies which went unpublished. (3) I don’t think the authors did a good job of selecting studies.

– In line with that, note that the CAST study was excluded from the eye-catching graph. Mmmh. Does not raise confidence this is honest reporting.

– While we’re at it, note that the eye catching graph is for primary endpoint AND that continuous primary endpoints are excluded AND that the authors note that mortality was reported in 24 of 30 trials pre-2000 (80%), which means two things: (1) they could very well have done the eye-catching graph for all-cause mortality with the added benefit of having a consistent outcome. Figure 1 with ‘primary endpoint’ is mixing outcomes like ‘death’ with ‘developed atrial fibrillation (y/n)’, which is a considerable limitation. That they don’t report Fig 1 for all cause mortality makes me suspicious. (2) That they want to sell the story of no-preregistration = outcome switching and thus try to downplay one outcome being consistently reported in almost all studies (Whether all cause mortality is being selectively underreported pre-2000 would require a look at the studies in question. If they’re like fish oil, then no, it’s perfectly benign that fish oil doens’t report mortality).

– Ok, so what would the results for all-cause mortality look like? See Figure S2, meta-analytic overall null effects both before and after 2000 (The p-value in that line is for the heterogenity test, you need to check whether the CI’s of the overall effect include 1.) Do they mention that in their discussion? No, instead they treat it as gospel that there was a decrease around 2000 despite the fact that this is only true for one of their DVs (namely primary endpoint) and not true for the other. (At which point I’d like to acknowledge a commenter on PLOS One pointing out that this meta-analysis was apparently not preregistered and for myself wonder, whether there wasn’t a bit of outcome switching involved in the meta-analysis as well.)

– On a content level, all these studies are ‘evaluating drugs or dietary supplements for the treatment or prevention of cardiovascular disease’. Yet when I look through the list of studies, directly acting oral anticoagulants (DOACs) are missing. This is certainly explicable in some way, but OTOH, DOACs are a major advance in the treatment of atrial fibrillation, CAD, MI etc., which I’d count as cardiovascular, and DOACs trials were published from around 2008 onwards. It’s a bit odd to not even mention that whole segment of studies, which might well have added some non-null results post 2000.

– While on the subject of DOACs, it’s relevant to consider how those trials work: The aim is usually to show non-inferiority to warfarin (the standard drug) for a couple of outcomes and to show improvement over warfarin on some of those outcomes. Warfarin itself trades off bleeding versus thrombi, and so a better drug can lower either while keeping the other constant. Yet you only get one primary endpoint, and depending on which you pick the pre-registered trial is either null or not. The point is, in these kinds of things it’s often not clear, what the correct primary endpoint is and there’s a continuum from total pre-registration to measuring 30 outcomes and only reporting the best. In the middle you have studies which don’t much care a-priori whether they get fewer strokes or fewer myocardial infractions but they expect either or both to go down, and if it so happens that both decrease, yet one is significant and the other is not, then the significant gets written up in the paper in the spirit of putting one’s best foot forward. That’s ‘outcome switching’, but it’s outcome switching in the same sense as a meta-analysis highlighting a figure for one endpoint and not producing the figure for another endpoint.

– In light of that, in turn, it looks to me like the data are most plausibly explained by some curious selection choices in the meta-analysis, more selective reporting and file drawering before 2000 and the low hanging fruit being picked as science advances.

– For further conclusions about the relative importance of these factors, we’d need to see the analysis repeated: including continuous outcomes, including DOAC trials, lowering the financial requirement or raising it, preferably while addressing the sample size differences pre-2000 and post, and most importantly, doing this with something non-cardiovascular. Basically: We all believed, prior to reading the study, that forcing scientists to pre-register their studies keeps them honest and that file drawering and p-hacking are a thing we get less of with pre-registration. It would be very odd if the results said anything else and we’d be doubting the study design, not the theory, if they did. So, obvious things being obvious, what we really want to know is how strong the effect is. This study, in isolation, is a poor guide to that question, for reasons given above.

If you check sample sizes you’ll find that the pre-2000 results represent a total sample of 57k, with 22k of those coming from one study. The post-2000 sample size is 232k, so 4 times the pre-2000 sample size. This suggests a very simple explanation, namely that the pre-2000 results have a file drawer problem, coupled with the statistical necessity of anything significant in small samples being an overestimate.

I am amused by the irony of someone criticizing the statistical basis for the claims of a study claiming that studies generally lack statistical basis for their claims 😀

Thanks for this. Want to dig into the research when I get some free time later. But just want to say that very few people could do what you do, Scott.

Admit a mea culpa, make a serious effort going through the research in an unbiased way, get yelled at by a bunch of people on the Internet, calmly and charitably pay attention to their points, double the effort to dig into the research, still remain unbiased and open-minded, without any other expectation other than getting yelled at by people on the Internet some more.

I’ll probably do some yelling at you later. But for now, just want to say you don’t get a tenth of the appreciation that you deserve.

As often happens here, I found the comment that I wanted to make already posted. Well said.

Just want to agree completely.

Agreed.

Pre-school and daycare programs seem to me to be aimed at two problems primarily, that have little to do with educational outcomes, that are not mentioned much, if at all, in the literature. They are sometimes discussed as add-on topics (and came up in the last post’s comments).

1) Helping young and struggling families with childcare needs so that they can work, go to school, or otherwise advance themselves.

2) Removing children from very bad environments in an attempt at providing positive examples that their home lives lack.

I feel as though these are the actual reasons that we, as a society, push for Head Start and other pre-school programs. We also seem reluctant to talk plainly about these goals, with the exception of some quite recent Democrat pushes for daycare. The goalpost moving being complained about with the switch from “educational attainment” to “life outcomes” makes more sense if what we always cared about was closer to “life outcomes,” but wouldn’t have been accepted as a valid approach in the 60s. #1 is welfare wrapped in a different package (with associated baggage and complaints) while #2 is demeaning and would be incredibly insulting to talk about. What kind of disadvantaged mother would sign up for the “the state thinks I’m a horrible mother” program?

This topic feels to me like everyone is kinda in on the real reasons, but we’re playing taboo and can’t talk about it in broad society. Anyone else get a similar impression?

I think it’s more like people thought the purpose of school was education and educated people have better life outcomes, so improve the schooling. But after decades of believing intelligence / school performance was largely (half? all?) environmental, people are beginning to concede that no, significantly increasing intelligence is nigh-impossible and raising test scores is really really hard. I don’t think the initial advocates for Head Start deep-down knew this was the case and hid it. People thought early childhood education could make smarter adults, but no, not really, but it maybe can make better socially adapted adults.

I agree that the original proponents would have made the connection from intelligence/school performance to environment as you say. On the other hand, if the goal was life outcomes, and education was a means, then they can drop education and not change direction. Even thinking that was the best method to achieve their goal did not tie them to that method.