I’m gradually reading through responses to the Anti-Reactionary FAQ, but I’ll take a moment to respond to this excellent and well-argued post from Habitable Worlds in particular because it points out an especially deep disagreement.

Scharlach from Habitable Worlds objects to my point 3.1.1, which claims that progressive ideals aren’t particularly novel or modern because classical Rome shared many of the policies we most associate with progressivism. I mention welfare, strikes agitating greater rights for the poor, multiculturalism, religious syncretism, sexual libertinism, and utopianism.

Scharlach disagrees. He first points out that classical Roman “strikes” were not about greater rights for the “poor”, per se, but for plebians, a class of non-nobles that actually included some very wealthy people. I accept his clarification, but I would add that modern progressive movements are happy to conflate “class made up of disproportionately poor people” with “poor people” as well, whether we are talking about the unemployed, inner city youth, minorities, high school dropouts, inhabitants of the Third World, or whatever. Heck, modern progressivism calls women a “minority” even though they make up 51% of the population just because it is a convenient way to lampshade their less privileged status. So I don’t think it’s especially unprogressive that “more rights for plebians” was the classical Roman rallying cry, rather than “more rights for the poor” per se.

But the crux of his objection is more philosophical:

But the question is: do these seemingly “progressive” policies stem from what today we would consider progressivism? Do they have anything to do with “social justice”? We should remember that when looking back at history, curious similarities arise, but they do so at incongruous joints, and their existence may not signify anything but the fact that large-scale political ecologies have limited practical expressions. Think of it this way: A society whose political discourse and ideals sanction welfare to the poor because it is believed that the underclass is genetically inferior, incapable of taking care of itself, and might revolt if not given enough food . . . that’s a very different society from one whose political ideals sanction welfare because it is believed the poor have a right to good living standards or that the poor deserve welfare because it re-distributes goods rightly theirs but taken from them through an oppressive economic system.

Contemporary progressive policies emerge from ideals and discourses about morality, justice, oppression, and rights. The poor (especially the dark-skinned poor) deserve the welfare they get; it is theirs by Constitutional right. It is a moral and political imperative not to take away the welfare they receive and to give them more if possible. Progressives actively try to alleviate the shame once associated with receiving welfare. Pointing out that the poor in America have it pretty good is a distinctly right-wing thing to do. ”Food stamps” are now “EBT cards” that look and function like debit cards. Medicaid patients sit in the same waiting rooms as patients paying high insurance premiums, and you can’t tell the difference. (Well, you can, but . . .) Welfare in America has become a right, a moral imperative, a matter of justice and just desserts, a thing that brings no shame, a thing to be proud of, a thing to demand, a thing to stand up for…

So Scott Alexander is correct that social policies in ancient Rome look similar to contemporary progressive welfare policies. But were the motives the same? Did the poor and the plebians get free or reduced-cost corn, grain, wine, and olive oil . . . . because they deserved it? because it was theirs by moral and legal right? because it was a matter of social justice?

I’m not a classicist, so I’m willing to be corrected on this, but as near as I can tell, the Roman dole was wrapped up in discourses about a) the might and wealth of Rome and b) goddess worship. Welfare policies in ancient Rome were built upon very different ideals and emerged from very different motives than contemporary progressivism’s welfare policies. Nowhere have I been able to fine a discussion of the Roman congiarium in terms of rights or justice. The dole was there because it made the emperor more popular and demonstrated the wealth of Rome to the people. What’s more, the dole was personified as Annona, a goddess to be worshiped and thanked. Scott Alexander even recognizes this difference in motive when he says that ancient Romans “worshiped a goddess of food stamps.”

Indeed they did. And that’s the whole point. When was the last time you heard welfare policies discussed in terms of worshipful gratitude, mercy, and thankfulness? If that were the discourse surrounding welfare policy, America would be a very different country. It seems that Roman welfare and American welfare are as different from one another as Jubilee is from abolitionism.

I will agree that the Romans used different philosophical justifications for their welfare state than do moderns, but before discussing this, a lengthy and kind of pointless also-not-a-classicist digression on why the difference may not be as big as Scharlach suggests.

If the essay is trying to compare the grateful Roman poor and the entitled, demanding modern poor, I propose that the Roman recipients of the annona were as entitled and demanding as any modern. Ancient Roman leaders automatically assumed any hiccup in the flow of free grain would lead to riots, and their assumption was justified. You may for example read the section on Roman food riots here. Particular high points are the riots of 22 BC, during which rioters threatened to burn the senators alive if they didn’t produce enough free grain, and the riots of 190 AD, when Papirius Dionysius, the prefect in charge of the grain supply, accused political enemy Marcus Aurelius Cleander of threatening it – the disturbance ended when the Emperor Commodus killed Cleander and his son and threw their heads out to the angry mob (which instantly calmed down and dispersed).

Or the essay may be trying to compare a Roman attitude of giving small strategic grants of welfare to the worthy with a modern attitude that everyone deserves as much welfare as they want at all times regardless of situation or else their human rights are violated. But here, too, I do not think the distinction is as great as is claimed. 83% of Americans believe people on welfare should be required to work, and only 7% oppose such a requirement. 69% believe that there are too many people on welfare and the criteria need to be stricter, compared to only 24% who believe the opposite. People who want welfare benefits need to jump through various bureaucratic hoops (some of which are actually kind of stupid) and usually receive them only for a limited amount of time.

(this interpretation would remind me of my frequent complaint that some reactionaries say “X is an unquestionable dogma of our modern society” when they mean “I heard about a college professor who believes X”.)

So much for our pointless digression. Scharlach probably means something more like “Ancient Rome didn’t have modern concepts of human rights and social justice.” I agree with this. I just don’t think it matters.

I assume Scharlach read my FAQ part 3.3, where I claim that progressive values are closely linked to urbanization and technological/economic growth. But he may not have read my We Wrestle Not With Flesh And Blood…, so I’m worried he might have interpreted me in 3.3 as claiming something like:

Urbanization + Growth -> Progressive Values -> Social Change

If that had been my thesis, then it would indeed be relevant that the ancient Romans didn’t have our version of progressive values. Their social change would be a coincidence, unrelated to ours since it missed the crucial middle step that determined the shape our social change would take.

But I’m not proposing that model. I’m proposing one that looks more like this:

Urbanization + Growth -> Social Change -> Progressive Values

(really the “social change” node should be called “pressure for social change”, and it and the “progressive values” node should have little circular arrows both pointing at each other, but let’s keep it simple)

Let me give an example of what I mean.

A 25th century historian, looking back at our own age, might notice two things. She would notice that suddenly, around the end of the 20th century, everyone started getting very fat. And she would notice that suddenly, around the end of the 20th century, the “fat acceptance movement” started to become significant. She might conclude, very rationally, that some people started a fat acceptance movement, it was successful, and so everyone became very fat.

With clearer knowledge of our era, we know better. We know that people started getting fat for, uh, reasons. It seems to have a lot to do with the greater availability and better taste of fatty, sugary foods. It might also have to do with complicated biological reasons like hormone disrupters in our plastics. But we have excellent evidence it’s not because of the fat acceptance movement, which started long after obesity rates began to increase. If we really needed to prove it, we could investigate whether obesity is more common in populations with good access to fat acceptance memes (like, uh, Wal-Mart shoppers and American Samoans).

To us early-21st century-ites, it’s pretty clear why the fat acceptance movement started now. Its natural demographic is fat people, there are more fat people around to support it, they feel like they have strength in numbers. and non-fat people are having trouble stigmatizing fat people because it’s much harder to stigmatize a large group than a small group (no pun intended).

Does this have any relevance for the sort of thing reactionaries talk about? Yes. Let’s look at divorce.

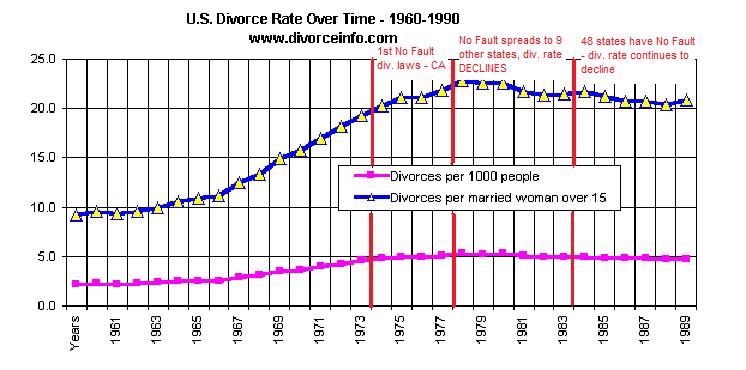

From a historical perspective, no-fault divorce was legalized in the early 1970s, and divorce rates were skyrocketing in the early 1970s. It is incredibly tempting to want to attribute skyrocketing divorce rates to easy-access no-fault divorce.

It’s also wrong. From an excellent article I entirely recommend:

Just from the graph it should be clear how little no-fault divorce mattered, but if you need more formal research it has certainly been done. Even the conservative Institute For Marriage and Public Policy admits in its review article on the subject that “divorce law is not the major cause of the increase in divorce over the last fifty years”, and that even the small bump from no-fault provisions “while sustained for a number of years, eventually fades and the divorce rate moves back to trend”.

I’d guess that the explanation for why skyrocketing divorce rates and no-fault divorce both happened in the early 70s is a lot like the explanation for why skyrocketing obesity rates and fat acceptance both happened in the early 2000s. Lots of people started getting divorced. Under older, stricter divorce laws, this required couples who wanted divorces to manufacture some bogus complaint with the help of lawyers, an embarrassing and expensive process. Eventually the number of people divorcing or wanting to divorce became sufficiently large to form a good political lobby, and the people not involved in the divorce process couldn’t keep stigmatizing divorcees because there were too many of them for it to be easy or convenient. So the divorce lobby won and passed no-fault divorce laws.

I don’t deny that sometimes these ideological movements and the laws they pass have some effect, like the small, quickly fading effect of divorce laws mentioned in the quote above. That’s why I wanted little circular arrows between “Social Change” and “Progressive Values” above. I’m just saying these effects are small and not particularly interesting. They’re the tail wagging the dog.

And I don’t deny that the progressive movement pushing a social change often exists before the social change does. If 100 years from now the existence of vat-grown meat causes all factory farming to shut down, no doubt PETA will claim victory. But just because PETA pushed for the event, and then the event happened, doesn’t mean PETA was the main cause. At best, they kept pushing but it was only the technological change that helped them gain power and respect and enact their positions. At worst, if they didn’t exist then within ten minutes of the invention of vat-grown meat some other group would have sprung up to accept the easy moral victory it provided.

So let’s get back to Rome.

Scharlach points out that the value system associated with Roman welfare was different from the value system associated with our own welfare system.

Ancient Rome had a population of about a million people crowded together, a government vulnerable to the mob, and resources to spare. I propose those situations will, more often than not, inspire a welfare system. They did it in ancient Rome, and they’re doing it in modern DC.

According to legend, Frederick the Great declared of his conquests: “I will begin by taking. I shall find scholars later to demonstrate my perfect right” (okay, Reactionaries, I will admit Frederick the Great was hella cool). If Frederick was in the welfare business, he might have said “I will begin by giving welfare. Later, I will find scholars to come up with a philosophy supporting welfare.”

And just as any historical account of why Frederick conquered new territories should focus on his self-interested goals rather than on whatever justifications his scholars later cooked up, so an account of why we give welfare should focus on the economic, material, and technological conditions that inspire it, rather than fretting over how one society talked about the goddess Annona and another talked about social justice. I’m sure if Frederick conquered both classical Rome and 21st-century America, his Roman supporters would declare he was following the will of Jupiter, and his American supporters would declare he was trying to help disprivileged minorities. It would be the historian’s job to see through that (and also to sort out what I expect would be a very confusing timeline of Frederick’s life).

Which brings us back to Rome one last time. I didn’t discuss the Roman welfare state in isolation. I mentioned it in the context of Rome being surprisingly progressive in a lot of other ways – its plebian “strikes”, its multiculturalism, its religious syncretism, its loose sexual morals.

If the resemblance between Roman and modern welfare systems is a mere coincidence, then we have to add a striking number of other coincidences to the list. Eventually the conjunction of all these coincidences starts to look unlikely.

But there is a neat explanation for all of them. States that are militarily secure, economically advanced, multicultural, and urbanized tend to adopt progressive policies (here I am confusingly lumping some values like multiculturalism in as policies, but you know what I mean). Ancient Rome and modern America are both militarily secure, economically advanced, multicultural, and urbanized. In between stand a bunch of countries the Reactionaries like to talk about like the Holy Roman Empire, which were not militarily secure, economically primitive, monocultural, and more rural. Those countries didn’t have progressive policies or values.

The original question was whether ancient Rome could be called a progressive society. I say it was. Scharlach objects that it wasn’t, because it didn’t have the particular brand of progressive philosophy we do today. But I respond that the philosophy is irrelevant to what we presumably care about – social policies and social outcomes. Policies (like welfare) and outcomes (like the existence of a large class of welfare-dependent poor) were the same in classical Rome and modern America, and for the same reasons. Therefore, it is correct and useful to call classical Rome an early progressive society, though with the obvious caveat that it did not go as far in that direction as our own.

Your point of view — unlike your opponents’ — fits in well with an increasing shift in my own thought away from traditional “narrative” history (featuring heroic figures and their ideals, achievements, and failures) and toward economics as the driving force of political and social change.

(Yes, I realize that some will consider me rather late to this party…)

I agree with S.A. that neo-reactionaries err by haphazardly treating constants as variables. They have neglected ethics.

I disagree with the implied choice between economics and individuals as the engine of history, unless the concept of economics is extended to encompass everything and becomes trivial. Urbanisation, atheism, mass media, technology, science and the state of institutions are other distributed and impersonal forces that have turned progressivism, as well as Nazism and Communism, into a stable reigning ideology.

A (more or less) reactionary idea with which I agree is that the few and simplistic insights of economics are too prominent in our culture’s discourse. This draws attention away from problems that demand that we understand legal and political systems in detail, not stopping at high abstractions about ‘free markets’.

I agree with you. I only said “economics” to avoid having to say “urbanization, atheism, mass media, technology, science, and the state of institutions” every time.

I think I said “economic, material, and technological factors” a few times, which seems like a decent summary.

Also, I think there’s probably a level at which discourse needs to transcend the simplistic insights of economics, but right now I’d be *thrilled* if people demonstrated understanding of even the most simplistic economic ideas, and the prosperity of society would probably triple overnight.

I disagree here. It seems to me that economics has nontrivial things to say about “everything”. (It may help to remember that most people’s conception of “economics” is too narrow; in particular, much narrower than “that which is studied by economists”, which is close to my intended meaning.)

Nevertheless, I probably should have written “economics etc.” for greater clarity. (Cf. also Scott’s comment below.)

Party’s still happening. Being late doesn’t matter, as long as you show up and want to get funky.

I’m starting to suspect both individual achievements and big social trends have a role to play in historical events. Take the American Civil War.

Here we have a conflict between a (relatively, for the time) urbanized, industrialized Progressive North and an agricultural, aristocratic, almost Reactionary South, to the point that some Southrons cooked up theories of race that said that Yankees were the descendants of Anglo-Saxons, while Southerners were the descendants of the Norman barons who conquered them, and thus Southerners were the rightful leaders of the United States.

And this conflict had been going on for *decades,* ever since the writing of the Constitution! Compromises in 1820 and 1850 helped defuse specific arguments, but the fundamental conflict between an increasingly industrial North and a slave-economy South remained, ready to flare up. A bit like a peat fire, the kind of thing that can smolder underfoot for decades at a time. And eventually it flared up huge and destructive and wrathful and we had Blue and Gray slugging it out on the battlefield.

But one of the sparks of that conflagration was the election of Abraham Lincoln. Look at an 1860 electoral map and you’ll see something striking – Lincoln won *without a single slave state* voting for him. And the huge population of the Northern states meant that the South’s control of the executive was effectively gone forever.

That’s the Big Formless Things grinding at each other. The ossified wealth and privilege and aristocratic social norms of the South met the industrial productivity and enormous population of the North and the South lost badly. One Big Formless thing won, and the other lay broken and battered, its soldiers silent in graves, its plantations smoldering ruins.

And then a funny thing happened. A pro-southern fanatic and actor shot Lincoln in the back of the head, and Andrew Johnson became President.

Here’s an example of individual characteristics and achievements messing up the Vast Formless Things. Because Andrew Johnson was culturally a Southerner. He’d been the military governor of Tennessee, and loyal the the Union, but he’d been chosen to balance the ticket, not for his allegiance to Lincoln’s policies of integrating the freed slaves into society. And once he was in the chair of power, he tried to move political power in the South away from freed slaves and into the hands of poorer whites. Many Southern states enacted “Black Codes,” essentially slavery under the guise of labor contracts.

Lincoln, we think, had a clear idea of policy toward the Confederate states and the freed slaves. Johnson didn’t. So when Booth shot Lincoln, he won a clear victory for the almost dead Vast Formless Thing of the Southern aristocracy. The individual actors implementing reading from the script of the Northern Industrial Vast Formless Thing all had different scripts and without a director (Lincoln) to keep them on the same page, went at each other while the Southern Aristocracy Shoggoth licked its wounds and held onto some vestige of control.

(Though notwithstanding any de-emphasis on heroic leaders in political history, as a musician I am compelled to agree about Frederick the Great’s “hella cool” status.)

“I begin by taking. I shall find scholars later to demonstrate my perfect right.” is from “The Suppliants”, by Euripides.

Actually, I read it was in “The Suppliants” but I can’t find it.

83% of Americans believe people on welfare should be required to work, and only 7% oppose such a requirement. 69% believe that there are too many people on welfare and the criteria need to be stricter, compared to only 24% who believe the opposite.

I doubt it affects your point, but I don’t trust these numbers to reflect people’s actual beliefs. These numbers show people reacting predictably to applause lights. I bet if we ask the question as “should welfare support more low-income people” then there’d be more than 24% saying yes.

Gay marriage becoming increasingly legalized as support for gay rights grows seems like another good example. And at least for me, the gay marriage example makes it quite clear that pressure for social change has to come first – look at how hard it is to get it legalized, even though there is massive support for it. (My country’s quite liberal, but still hasn’t fully gotten around it.) Postulating an alternate history where politicians just said “oh hey, maybe we could make gay marriage legal”, leading to a spread of gay acceptance, seems not only implausible but downright impossible.

Or if that scenario doesn’t sound crazy enough, take polyamorous marriage: how plausible does it sound that politicians would just declare “oh, let’s allow multiple people to be married to each other” tomorrow, with no massive public support for the idea but certainly massive public opposition?

And yet, although it seems rather impossible that it would happen with gay marriage or poly marriage, I still accepted essentially the same having happened for no-fault divorce until I read this post.

Gay people have been living together since there were people, so the change definitely came before social pressure for legalizing the change here.

Living together and being married are two different things.

They are indeed. Marriage is legalized living together.

The OP at habitable worlds said:

but as near as I can tell, the Roman dole was wrapped up in discourses about a) the might and wealth of Rome and b) goddess worship.

America might not have had (b), for obvious reasons, but I’m not sure our welfare state never had (a). I’d have to check, but didn’t a lot of social programs starting from at least after World War II, if not the New Deal, have more than a few justifications along the lines of “America is the mightiest and wealthiest nation in the world, none of her citizens should ever go hungry?”

This is probably correct. However, progressivism before the 1960s was also quite different from what it has morphed into. I wrote a short post on this very issue recently: http://habitableworlds.wordpress.com/2013/10/10/moral-and-technological-progress-2/

Early progressives were eugenicists, you know 😉 Almost reactionary!

“his American supporters would declare he was trying to help disprivileged minorities”

Only if his supporters were mostly social justice activists, which seems unlikely. Didn’t you just point out that American society is way less leftist than Reactionaries like to imagine?

Rhetoric about helping groups generally thought of as disadvantaged is way more common in the States than acceptance of the full-blown social justice memeplex. In fact, I’d say one of SJ’s key advantages comes from its use of that kind of rhetoric, which is pretty hard to attack directly without violating one of more widespread taboos.

One or more, rather. Too used to having an edit feature.

“Urbanization + Growth -> Progressive Values -> Social Change

If that had been my thesis, then it would indeed be relevant that the ancient Romans didn’t have our version of progressive values. Their social change would be a coincidence, unrelated to ours since it missed the crucial middle step that determined the shape our social change would take.

But I’m not proposing that model. I’m proposing one that looks more like this:

Urbanization + Growth -> Social Change -> Progressive Values”

It’s too bad these diagrams aren’t in the FAQ, to me they are the most devastating critiques of reactionary thought because if there are true then the reactionary proposal to get rid of progressive values is downright absurd.

Right, there’s a crucial missing “ceteris paribus” here, which in other contexts would lead to uncontested conclusions like:

Urbanization + Growth -> Increased demands for power generation -> Increased pollution

But noting that modern societies produce more pollution than traditional societies does not lead to the conclusion that we should emulate successful past (pre-industrial, low urbanization) societies that produced very little pollution.

True. Do you consider yourself the equivalent of that particular splinter of environmentalism?

From what I understand Reactionaries think that progressive values are harmful because they lead to societal change/decay and that is a problem that needs to be solved. If progressive values are a result of social change (and not the other way around) then proposing to solve everything by getting rid of progressive values is absurd.

If someone thought that they could change demands for power by decreasing pollution then I would consider that absurd.

I’m pretty surprised by your insistence (here and elsewhere) that Reactionary *or* Progressive ideas are still important once we have transhuman level technology. Once we can cure impulsivity and make IQ as high as we want, the problems seem to go away or at least change character drastically.

Value stability is only desired for terminal values, not intermediate ones. Are the reactionary values terminal values for you, then?

If sexual purity is a terminal value for you, then there’s no need to argue over the premarital sex/divorce issue. Sexual purity is desirable for its own sake, and should be sought even if it increased divorce. That’s how you tell.

I’ll admit, sometimes it’s hard to tell instrumental and terminal values apart in human minds. That’s because human minds are irrational lumps of evolved responses slapped together by Azathoth. Which is the same reason why human minds don’t converge to goal-content integrity in the first place.

If Volk makes the National Socialists demotist according to reactionary definition, then SPQR makes the Roman Empire is a demotist state, I would think. At least in the Principate period (eventually, SPQR fades from use and the emperors took on the form as well as the substance of monarchy, princeps giving way dominus and finally to basileus).

One of the things that reactionaries still haven’t really nailed down is a fully general theory of leftism. It seems clear that the trend of politics in the past few centuries appears to follow a particular vector in policy-space; what’s not clear is why this is the case.

So I am interested in the way that you approach the question and further develop the hypothesis posed in your “Thrive/Survive dichotomy.” I’d summarize it as a fairly-strong historical determinist hypothesis: once a society reaches a certain level of development, it inevitably starts to produce a cluster of behaviors we call “leftist,” and then confabulates political philosophy around it to justify these behaviors as a good idea, or even as natural rights. The ideology is not the root cause but rather a public-relations effort after the fait accompli, analogous to the model of the brain that should be very familiar to LWers. This is not a bad theory and is actually pretty close to my currently favored model as well. However, it does lead to some conclusions that you don’t seem to have drawn here.

1. Current progressive political narratives are almost entirely confabulations to justify underlying behavior changes. Talk of justice and rights do not represent far-seeing moral progress or wise interpretations of a living Constitution, but are post hoc rationalizations generated an algorithm that could just as easily justify Renaissance-era witch burning. (Right-wing narratives could of course also be insane, but whatever people are executing the ‘justify these social change’ algorithms *certainly* are.)

2. It’s not obvious that the “wealth + urbanization” changes are ones that we should approve of. There is no more reason to think that “above-subsistence humans in super-Dunbar environments” is the benchmark for human values, any more so than farmers or foragers or solitary asteroid miners should be. Certainly these changes don’t seem to be caused by an actual increase in knowledge or by moral progress. (If they are, then we should also consider increased atomization and decreased social trust – social adaptations to urban living and easy transportation – to likewise reflect moral progress.) If we see evolution as Azathoth, a blind idiot guide editing us in ways that are utterly orthogonal to human values, then perhaps the Cthulhu of value drift should be viewed in similar light. And by analogy, the process should be viewed skeptically, not as an end in itself, and supported only if it helps us reach particular terminal goals. Reaction in this sense can be viewed as a branch of transhumanism, believing that ideological drift is not something to be passively accepted but actively overcome, and pointing to past successful cultures to see that human society could become so much more than it currently is.

Another point:

3. It’s not obvious that the determinism is quite as strong as you believe. Republican France was poorer than late Prussia, yet appeared to be considerably more left-wing. Revolution-era Russia was poorer and more rural yet. Millenial movements such as the siege of Munster or the Taiping Rebellion mostly happen in societies that, economically, aren’t much different from the height of the Holy Roman Empire or the early Qing. There seems to be considerable room for governance and values to shift groups around in culture-space. It does seem true that the 20th century has less diversity in this regard than the average slice of the past, but that’s in part because of military/cultural conquest, not because such diversity has been proven impossible.

If the main point is that we shouldn’t accept the rhetoric of progressives because said rhetoric consists of post hoc rationalizations, but rather we should evaluate policies one by one using more careful and objective criteria then I can’t imagine anyone would object.

However that doesn’t mean that we should simply throw progressive values away. If the relatively strong deterministic hypothesis (which I don’t know if Scott believes, but I think is plausible) is true then values tend to be relatively optimized for the social/economic … environment at the time. So we would expect progressive values to generate the right answers a lot of the time in wealthy urbanized areas.

Lets take a specific example: welfare. (and I apologize for any historical inaccuracies, I am not an expert in this subject). In agrarian societies people grew their own food so they could always rely on themselves. As agrianism faded and people moved into cities, they no longer grew their own food because labor became specialized. Tractors and modern equipment meant that farms became super efficient, and a tiny number of farmers were able to grow enough food to feed an entire country. However, there was a downside – people could no longer guarantee that they would not starve. If they lost their jobs they were in trouble. Governments responded with welfare and over time rhetoric such as “Everyone has a right to food” became entrenched as a value. That statement is pretty silly of course – it isn’t an argument, its just a restatement of a belief without any real justification. The idea that “everyone has a right to food” wouldn’t have made sense in an agrarian society (certainly not in one where famines happened frequently) and it isn’t a universal value. But that isn’t particularly relevant to us since we don’t live in an agrarian society.

If I were to respond to 2 more directly, no it isn’t obvious that welfare is a great idea in general, and the fact that it was optimized for urbanized non-agrarian societies does not make it special or something to strive for as a human ideal. However we _do_ have tractors and super efficient farms now and they aren’t going to go away (we’re almost certainly not going to give those up). So until something better comes along welfare is here to stay.

Point 1 isn’t any more disturbing to me than moral anti-realism. And moral anti-realist can still support or oppose social policies. I think the “cause => policy => value” diagram is true of all values so its not uniquely a problem for progressive values. And there is enough terminal value overlap so that the problem of which values to use doesn’t seem to be a big issue to me.

Regarding point 3, if I may make a chemistry analogy, Scotts model predicts the thermodynamics of value drift. The kinetics are more complicated (as in chemistry).

I’m sorry but I can’t quite wrap my head around the ems scenario – could you spell out specifically a parallel argument to the one I made that would apply to ems scenario. What is the cause and policy?

No?

We already have the process of value drift, and it has produced a society that seems to me to be basically okay for most people. (This is not a unique trait of our society: I am willing to agree that, say, the Middle Ages or fifth century Athens, controlling for technology differences, are also basically okay for most people.)

Whereas you are proposing a process that has, as far as I know, never been tried before. It might be good, if your arguments are correct. But it might be really really bad. There might be downsides of preventing values drift we cannot see. AFAIK you have not explained *how* we should go about preventing values drift, but most of the methods I can think of involve violations of to-me key moral heuristics, such as autonomy. It might not be possible, so we waste resources trying to prevent values drift and don’t actually succeed in doing it. If Scott is correct and values drift is actually change in instrumental values to better suit change in material, technological, and economic factors, then stopping values drift is really really bad– like saying “your species hasn’t had fur for thousands of years, stop evolving fur just because there’s an Ice Age!”

Chesterton’s Fence applies to forces that are changing things, too.

I also think that you overestimate Scott’s similarity with the average 2013 Berkeleyan, given that he believes we ought to build a superintelligent computer to take over the world.

I already have a basically 1950s economic viewpoint. Ah, for the good old days of unions, economic equality, and a strong welfare state.

@ozymandias – I don’t really see how reactionary family values would work without a strong welfare state and secure jobs. Houses often need two incomes, because if one person gets sick/is fired they have another income to survive on. One income households would seem more sensible if there were more of safety net.

@coffeespoons:

How do you explain the way historical societies with single incomes and small welfare benefits worked? It would seem obvious that families, without having the fallback of the welfare state to rely on, would have a incentive to actually make arrangements against such eventualities, such as keeping savings or building good social bonds with neighbors who could help them in their times of need. By contrast, today, poor families know that even if they are irresponsible and short sighted, the bureaucracy will provide; guess what happens?

Also, households fail to capture most of the productivity gains of two incomes versus one income because such gains are simply siphoned into zero-sum expenses, such as rent, status, and credentialed education. See Yvain or Vladimir. A return to a single income standard would not hurt families; on the contrary, by freeing up the wife to look after the house, raise the children, track finances, and tend to her husband after a hard day of work, the quality of life would increase.

Coffeespoons, in practice the effect of women entering the workforce was exactly opposite, reducing security, as explained by the most powerful US reactionary in her best-selling book The Two-Income Trap: Why Middle-Class Mothers and Fathers Are Going Broke (Elizabeth Warren).

@Douglas Knight don’t Scandinavian countries have both high gender equality and job security?

I haven’t looked at the “two incomes cause less security” hypothesis in detail, so I could be wrong, but I’ve always attributed the decrease in job security in the US and Britain to 1) government policies from the 70s onwards (Reagan/Thatcher) and 2) globalisation – workers abroad being cheaper for companies to hire.

I’m not talking about job security at all; as you said, getting sick is as bad as being fired.

You said that it’s useful to have a second income to fall back on. But there’s a difference between having a second reserve worker to fall back on than having a second income already coming in. In practice people spend all their money. Back when the wife didn’t work, the family didn’t consume her potential income; if the husband got sick, she would get a job. Today the working wife has years of job experience and a higher income than if she needed to get a first job, but money is all spent; it is not a reserve protecting against the husband’s job loss.

Scandinavia is not monolithic. In Sweden it is basically impossible to fire people, while in Denmark it is very easy. But that has little to do with Warren. Welfare certainly works better in Scandinavia, which means that the final effects are not as bad, but I don’t know whether Scandinavia has the intermediate problems that Warren talks about, namely bidding up positional goods consuming everyone’s income.

Dunno about rents and status, but tuitions are waaaaaaaaay cheaper in continental Europe than in the Anglosphere.

Okay, I’m still not seeing the parallel argument, what is it? What would cause a society to adopt policies and values consistent with an ems future?

Unfortunately Robin seems to have Yudkowsky syndrome – it takes him a million words to explain a simple idea. This is the part that I’m struggling with:

” if the transition from an industrial society to a society of emulated human minds”

What is causing that transition? Take the farmer case: why would a group of farmers choose to work in a city even though it means giving up their own means of production? Because although there are risks, the wages in the city are higher (so the farmer can afford to buy more food on average than he could have grown) and the existence of modern technology reduces the need for farmers. He also has to work fewer hours.

On the other hand I find it very hard to imagine a scenario in which someone would choose to be uploaded as an em knowing that they could be deleted. Perhaps I’m misunderstanding the scenario.

Ems are simulations on computers. If Moore’s law is as powerful as and as long lasting as some think it might be (Hanson thinks it’ll probably slow down, but when Ems come around, it’ll come back faster than ever) then you’ll be able to do things so much faster in a simulation that you’ll need to be an em to get anything done at all.

Did you ever see DBZ? The Hyperbolic Time Chamber made the characters do a years work in a day. All the most productive people will do it, so you’ll have to do it, too. This goes for any domain, but especially basic economics. No one will delete you if you’re worth more than your bandwidth. (In theory. I mean contracts could cover foul play, but we might need rights somewhere anyway. Just don’t assume they look like contemporary values.)

@Alexander Stanislaw: Have you read “Crack of a Future Dawn”? That’s probably Hanson’s most concise explanation of his upload scenario.

Remember that uploads can be copied just like any other piece of software. So even a tiny number of people who, for whatever reason, decide to upload could jumpstart an em population explosion. Then the companies/countries that use uploads will have an enormous advantage over the ones that don’t, and accidental or deliberate modification of uploads creates variety, and darwinian pressures favor uploads who value making copies of themselves even when their life is hard and short, etc…

Okay that’s much clearer. I have to say that’s quite depressing and something only an economist could come up with:

Normal Sci Fci geek: “Whole brain emulations? That’s awesome! You could have virtual reality and virtual sky diving, epic adventures, the sky is the limit!”

Robin Hanson: “Whole brain emulations? How delightful, a replicable source of human capital! The productivity gains you could make by weeding out the weaker workers and copying the strong workers are huge!”

Apart from being depressing though, its an interesting idea to be sure. Murder is universally condemned at least partially because human lives are not replaceable. Take that away and you’re left with a very bizarre scenario. I don’t have much an opinion of the em’s world other than that.

I really don’t like Robin Hanson, partly because of this, and partly because of his politics-fails w/r/t rape, for example. Wish he would stick to being the Most Cynical Man In The World. In particular, his em scenario seems to me like it should lead to post-scarcity and also like he is abstracting morality too much.

Scott has criticized him on the basis that ems would probably end up getting modified in such a way as to take away their humanity.

Some excellent points brought up in this rebuttal. If my response ends up being short, I’ll post it here; otherwise, I’ll put it up at my blog.

I have to disagree that the philosophy behind a movement or an outcome doesn’t matter: I think there’s a very big difference between, say, someone who offers assisted suicide because they want a (relatively) safe way to commit murder, and someone who offers it because they believe in the right to end one’s own life at a time of one’s choosing.

Dr Harold Shipman got into trouble over this; would you seriously say “It doesn’t matter if John Smith will sell you poison because he gets a kick out of murder by proxy or because he wants to end your suffering, if you end up dead either way”?

>would you seriously say “It doesn’t matter if John Smith will sell you poison because he gets a kick out of murder by proxy or because he wants to end your suffering, if you end up dead either way”?.

Absolutely, as long as we’re actually talking about someone who’d end up dead either way. John Smith’s motives in this scenario are only important insofar as sufficiently bad ones might cause people to die who wouldn’t want to on reflection; if he takes the same actions and gives the same advice as a hypothetical perfectly altruistic euthanist, then as far as I’m concerned he can take his jollies where he finds them.

Motives only matter (to people) in as much they allow you to predict future behavior. If someone is pushing assissted suicide because they get off on murder, that matters only because it indicates they are likely to commit other murders as well, or exert pressure to undertake the suicide rather than urge due restraint, etc. If you could find some way of garunteeing that that would not happen (probably impossible) then the motives would be irrelevant.

You focus on divorce rate is silly, because marriage rates have plummeted. Marriage rates are at an all time low. With just the best couples getting married, divorce rates should be lower than ever but this is not the case.

More:

(1) People are marrying much later in life now, with fewer years of fertility left. Divorce is not a good option if you may not get another shot at having a family.

(2) Divorce rates do not properly capture what is going on. Many couples who would have gotten divorced are now simply shacking up and then breaking up, without leaving a legal trail. If these couples were included, divorce rates would be higher than ever.

(3) Years of economic stagnation mean that divorce is too expensive for many people. Instead, commonly people now separate and then get on with their lives. Similarly, marriage is also too expensive for many people.

(4) Speaking of later marriage into one’s 30s, this is itself to me a sign of decline. People stuck marrying people past their prime? Yuck. Objectively sub-optimal.

>just the best couples getting married

Surely you mean “most naive”. I’m not sure your counterfactual prediction is right.

Would have been a relevant argument in the anti-Reactionary FAQ article, but seems orthogonal to the point here. The only mention of divorce here is that despite the temptation to attribute (past) rising divorce rates to no-fault divorce, a close analysis shows that isn’t true.

Divorce risk is negatively correlated with age at first marriage, so I don’t think increased age at first marriage is objectively sub-optimal at all.

…wait, 30 is past their prime for you? That seems like a very unusual preference and I wish you the best of luck in being able to fulfill it.

Sure, but 1. the decline is slower than you may think and 2. the kind of attractiveness you can see from picture and you use to decide whom to have a one-night stand with isn’t the only thing that matters in long-term monogamous relationships, let alone marriages.

Damn, I’ve screwed up the formatting. I should look at the preview the next time.

As for ‘fat-acceptance’ vs. shaming, it makes an enormous amount of difference. In Japanese culture, fat shaming is a shared cultural pleasure and that nation is the least overweight developed country. My wife is Japanese and rocks the scales at 129 pounds after five pregnancies (not trolling, true statement). She just loses the weight each time because to be fat would be gross to her, and she’s on her way back to her normal 120 lbs. I benefit from her barbs about my weight and I have not gained any weight since she started dropping occasional insults about my stomach. With luck I’ll live as long as a Japanese person.

Japanese can get fat if they want to (witness the national sport) but they choose not to. Choice… what an intolerant, antiquated term…

A pretty big point of the article was that you shouldn’t assume causality flowing from the values (judgmental culture) to the social variable (lack of obesity).

Scott explicitly claimed it goes both ways. I would be super surprised if people thinking fitness was virtuous and fatness was shameful actually had no effect on fatness.

Shame/virtue has a huge effect on my behavior at least.

I’ve lived in Japan a few years and agree that they are very thin people.

But as I mentioned in post, Americans started becoming fatter than Japanese long before there was any such thing as a fat acceptance movement.

My interpretation of this data would be to look at the difference between US diet (primarily bread and meat) and Japanese diet (primarily rice and fish).

I admit there is a confusing question as to why America was the first country to have rising obesity rates, as opposed to Europe, Mexico, et cetera. I don’t think either of us can answer that question right now, but I’d be interested in being proven wrong.

Rome progressive, sure why not. I already had this narrative in my mind:

Step 1: Rome was awesome.

Step 2: Rome becomes progressive.

Step 3: Rome fails as a result of inward collapse and implosion.

Familiar?

That would be very odd, because the Ancient Roman Food Stamps and religious syncretism both started fairly early in the era of the Roman Republic and multiculturalism was definitely a thing by the time of the Pax Romana. If food stamps herald that the West only has another 600 years as a great power, in which time we will have astonishing political, scientific, and literary achievements, I don’t see them as a reason to be overly concerned.

Though welfare handouts of various forms have been around since before the United States:

http://www.welfareinfo.org/history/

“The history of welfare in the U.S. started long before the government welfare programs we know were created. In the early days of the United States, the colonies imported the British Poor Laws. These laws made a distinction between those who were unable to work due to their age or physical health and those who were able-bodied but unemployed. The former group was assisted with cash or alternative forms of help from the government. The latter group was given public service employment in workhouses.”

So we might have as few as 300 years of Cool Stuff before the apocalyptic fall. 😛

I’m not sure if this is the consensus among reactionaries about leftism, or even if they have a consensus which I kinda doubt. But the gist of some arguments is that Progressivism is a secular offshoot of Calvinism adapted to late 20th century culture, right? And Calvinism basically evolved from turmoil within the Catholic Church, which is one of the finished products of Early Christianity, right? And Early Christianity appeared in, and conquered, the already and unusually progressive (by modern standards) Rome despite the early Church’s eagerness to make brutal enemies of literally all the ideologies everyone else actually believed in that time and place, right?

So, to all appearances, what was more or less Progressivism catalyzed the creation and triumph of the twisted ideology uniquely capable of generating Progressivism? It’s probably just that I’ve spent the last week devouring half of Chesterton’s collective writings and am otherwise hopelessly ignorant of the actual subject matter, but it seems like this would mean that leftism is its own progenitor able to transcend causality. That or progressive ideas have just always been around in one form or another.

Still, I kind of like the idea of a group of intellectuals invalidating a rival ideology by proving it to be the Holy Trinity. Someone should write a story like that.

For the record, through intense reason and introspection (and a less consequential personal encounter) I’ve changed my mind greatly on feminism; I used to think things were getting a little too annoyingly feminist on ,preciois interwerbs – but now I seriously, solemnlly, completely unironically proclaim that we’ve been living under brutal unbearable patriarchal tyranny since about the beginning of agriculture/population growth/value capture, and that the 1960s revolutionary feminists in the West, as well as anarcha-feminists in Spain and in the Far East – were only just radical enough to grasp how fucked up shit is. MY gender is the enemy! (Not that many women aren’t complicit house negros). It is a cog in the machinery of immdrtsyiom. annihilation and sexualized reproduction! This shit got to stop, and men, by definition, can’t lead the way, they need to assist the radical cause.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Qiu_Jin

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Noe_It%C5%8D

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Shulamith_Firestone

http://arewomenhuman.me/ I’ve seen this fucking shit myself, and I’d never let you sweep old-timey shit under the rug with your pathetic “chivalry”. The only bit of “Chivalry” that could really make a systemic effect IMO is criminalizing all spousal rape, and herewe quite a neat graph by counry. Notice the fat black dot in the far east. Wonder why so many Singaporean men are still virgins. Pathetic zero-world futrure, I’d say. Who cares,if you’ve got the fence and the drone. The Watching Wall, The Reaper-Bird and the Troubled White Masculinity the Imperial Court is in ssson. Who cares Zimmermann was a wife-beater with a habit of abuse, the system allows him to keep on keeping on with the Wall and the Bird. One day They unwashed smelly hordes will come, – one day – but now white America would give its own flesh and blood to keep it enforcers happyl

ps. fuck yeah those Soviet tranqs are the fucking shit.can barely hit letters together, SO FINE MANG

Oh well…. finish it off with a nice Gibson generator</a?

Wpw. O sp,ehpw br[;e evem that:

http://www.geekosystem.com/lorem-gibson/

>(Not that many women aren’t complicit house negros)

This is what I don’t get about radical feminism. Some minority has decided that some set of values (autonomy, non-hierarchical relationships, etc) is of utmost importance. Sure, I can appreciate that. But then there’s this implication that some other larger and vaguely similar group, who afaik doesn’t even agree, should be made to get on board with this radicalism. Why is that?

Calling them nasty names is not an argument. What if the situation is not one of having internalized the oppression, but of having a legitimate philosophical stance in not caring about those things? Are you just pushing alien and possibly harmful values on people who don’t want it?

I’m not well versed in your philosophy, does it have an answer on that? Or is the assumption that the “house negroes” are just wrong taken as axiomatic?

My impression of many younger feminists I know is “whatever, as long as it’s someone’s *choice.*” Essentially, that women who choose to be housewives and mothers should be respected, the same as men who choose to be househusbands. But women should not be discouraged from seeking college and jobs – or as my mother was told, “It’s no use training you – you’ll just drop out of the workforce to have kids.”

BTW, she’s an aerospace engineer who worked on the Hubble Space Telescope.

Though feminism is a very, very, broad camp, and you end up getting a lot of different viewpoints.

@Andy

Ok, that may be what the nice feminist intellectuals are thinking, but the situation on the ground in many circles (including public discourse) *does* seem to be one of discouraging housewifery and motherhood. AFAIK, people who say things like “housewifery and motherhood are noble choices and may be a better choice than careerism for most women” in public discourse tend to get shouted down as evil misogynists who want to subjugate women or complicit house nigs.

I understand that it’s a morally retarded minority of crazies who do the witch-burning, but the broader feminist community doesn’t seem to be willing to stand up and say “no, that’s bullshit; demeaning motherhood is about the most anti-feminist thing you can do”, so the crazies get to control public discourse on feminism, and the rest of us have to assume that that behavior is condoned.

@nyansandwich

“I understand that it’s a morally retarded minority of crazies who do the witch-burning, but the broader feminist community doesn’t seem to be willing to stand up and say “no, that’s bullshit; demeaning motherhood is about the most anti-feminist thing you can do”, so the crazies get to control public discourse on feminism, and the rest of us have to assume that that behavior is condoned.”

And yet I’ve seen exactly that conversation half a dozen times in the last year or so. Then again, I’m on a college campus and exposed to a younger set of feminists who see exactly that decision coming in their futures.

I’d say: give it 5 or 10 years and we’ll start seeing exactly what I’ve seen – moderate feminists telling more radical feminists not to STFU, but to embrace multiple lifeways. The debate needs time to climb down the intellectual tower into the public square. And that’ll take time. Lots of steps on the tower, dontcha know.

“Notice the fat black dot in the far east.”

Brunei

“Wonder why so many Singaporean men are still virgins.”

???

Pingback: A Response to Scott Alexander’s Response to my Response to Alexander’s Response to Neoreaction |

Pingback: Addendum to the last post |

This internet site is certainly as a substitute helpful considering that I’m with the second developing an online floral web-site regardless of the fact that I am only commencing out for a result it is truly relatively little, nothing in any way similar to this online web-site. Can web page link to some from the posts appropriate here because they are fairly. Many thanks considerably. Zoey Olsen

Dear Mr. Scott Alexander,

You are right on the surface, but you don’t know deep enough. Please think this through:

1) The ideology of progressive movements like the fat acceptance movements rests on concepts like equality, all human beings having equal value, and freedom in the sense of the freedom of subjective choice.

2) Value means suitability for a purpose. A good knife is one that cuts well, i.e. well suited for the purpose of cuttin, a good doctor is someone who is well suited for the purpose of healing people, and a good human beging is…. is um, er, what? Well suited for the purpose of human beings? Is there one? Wait…

3) Any statement about the value of human beings, i.e. it being equal or not equal, rests on the idea that value is even definable for human beings i.e. being a homo sapiens sapiens is inherently directed towards a goal. But the last people who believed in that were the Scholastics who took it from Aristotle and Aquinas. And they were the last reactionaries. Not conincidentally.

4) If human life has no inherent direction, it means we may as well live according to our own desires and wishes. This is where the freedom of subjective choice comes from. If there is no goal we all are supposed to pursue, then our value is equal or rather #undef. And if every value judgement comes from someone’s desire, then the desires of one person worth just as much as the desires of another person.

This is where everything comes from, from fat acceptance to accepting gays. If human beings are not naturally geared towards reproduction in the sense that people who reproduce are considered better because they are well suited for an important subset of human goals, if sex is just for fun, what is wrong with gays indeed? If aesthethics is subjective, and everybody is free to make a choice between living long or dying young but having lots of fun, what is wrong with being fat indeed? When we look down on fat people, we feel like they are failing some built-in goal in life. Fat acceptence like all the other progressive movements is based on the idea that there is one.

So, Mr. Alexander, ideology is not merely about social circumstances. It is also about whether we believe that human life is goal-oriented, teleological, Aristotelean, and thus do not really believe in equality or subjective freedom, or do.

Pingback: Reaction Ruckus | Handle's Haus

Two points:

1) I concur with earlier posters that if social change drives progressive values and progressive values drive social change, then you haven’t fully rebutted important reactionary – or at least conservative – claims in this area. It may be true that comparatively, the latter effects are “small.” But they can still be important, because these are areas we have more control over. For example, the Pill probably played a much bigger role in rising divorce rates than no-fault divorce. But banning contraception is not a politically viable option today, whereas toughening divorce laws (and, say, providing economic incentives for people to get and stay married) is. (Cultural changes, such as making more people Catholic, are also semi-feasible.)

2) I think it’s ironic that you hold up Rome as a progressive society, especially your wording in the Anti-Reactionary FAQ:

Although their tolerance famously did not always extend as far as Christianity, when the Romans had to denounce it they claimed it was not a religion but merely a “superstition” – a distinction which itself sounds suspiciously Progressive to modern ears. Indeed, the insistence of Christianity (and Judaism) on a single god, and their unwillingness to respect other religions as equally valid (in a very modern and relativistic way) was a large part of the Roman complaint against them.

If this is “progressive,” that seems like fuel for the fire of the contemporary conservative Christian narrative of totalitarian progressivism oppressing Christians.

Scott, are you familiar with the works of Oswald Spengler? His civilization model (unrigorous narrative history though it may be) accounts for a lot of the parallels you draw between Ancient Rome and the modern United States, all while working them into a generally reactionary (or at least antiprogressive) understanding of human history. You could think of it as a generalized theory (and telos) of value drift.

i am HERO 😀