[Content note: food, dieting, obesity]

I.

The Hungry Brain gives off a bit of a Malcolm Gladwell vibe, with its cutesy name and pop-neuroscience style. But don’t be fooled. Stephan Guyenet is no Gladwell-style dilettante. He’s a neuroscientist studying nutrition, with a side job as a nutrition consultant, who spends his spare time blogging about nutrition, tweeting about nutrition, and speaking at nutrition-related conferences. He is very serious about what he does and his book is exactly as good as I would have hoped. Not only does it provide the best introduction to nutrition I’ve ever seen, but it incidentally explains other neuroscience topics better than the books directly about them do.

I first learned about Guyenet’s work from his various debates with Gary Taubes and his supporters, where he usually represents the “scientific consensus” side. He is very careful to emphasize that the consensus doesn’t look anything like Taubes’ caricature of it. The consensus doesn’t believe that obesity is just about weak-willed people voluntarily choosing to eat too much, or that obese people would get thin if they just tried diet and exercise, or that all calories are the same. He writes

The [calories in, calories out] model is the idea that our body weight is determined by voluntary decisions about how much we eat and move, and in order to control our body weight, all we need is a little advice about how many calories to eat and burn, and a little willpower. The primary defining feature of this model is that it assumes that food intake and body fatness are not regulated. This model seems to exist mostly to make lean people feel smug, since it attributes their leanness entirely to wise voluntary decisions and a strong character. I think at this point, few people in the research world believe the CICO model.

[Debate opponent Dr. David] Ludwig and I both agree that it provides a poor fit for the evidence. As an alternative, Ludwig proposes the insulin model, which states that the primary cause of obesity is excessive insulin action on fat cells, which in turn is caused principally by rapidly-digesting carbohydrate. According to this model, too much insulin reduces blood levels of glucose and fatty acids (the two primary circulating metabolic fuels), simultaneously leading to hunger, fatigue, and fat gain. Overeating is caused by a kind of “internal starvation”. There are other versions of the insulin model, but this is the one advocated by Ludwig (and Taubes), so it will be my focus.

But there’s a third model, not mentioned by Ludwig or Taubes, which is the one that predominates in my field. It acknowledges the fact that body weight is regulated, but the regulation happens in the brain, in response to signals from the body that indicate its energy status. Chief among these signals is the hormone leptin, but many others play a role (insulin, ghrelin, glucagon, CCK, GLP-1, glucose, amino acids, etc.)

The Hungry Brain is part of Guyenet’s attempt to explain this third model, and it basically succeeds. But like many “third way” style proposals, it leaves a lot of ambiguity. With CICO, at least you know where you stand – confident that everything is based on willpower and that you can ignore biology completely. And again, with Taubes, you know where you stand – confident that willpower is useless and that low-carb diets will solve everything. The Hungry Brain is a little more complicated, a little harder to get a read on, and at times pretty wishy-washy.

But listening to people’s confidently-asserted simple and elegant ideas was how we got into this mess, so whatever, let’s keep reading.

II.

The Hungry Brain begins with the typical ritual invocation of the obesity epidemic. Did you know there are entire premodern cultures where literally nobody is obese? That in the 1800s, only 5% of Americans were? That the prevalence of obesity has doubled since 1980?

Researchers have been keeping records of how much people eat for a long time, and increased food intake since 1980 perfectly explains increased obesity since 1980 – there is no need to bring in decreased exercise or any other factors. Exercise has decreased since the times when we were all tilling fields ten hours a day, but for most of history, as our exercise decreased, our food intake decreased as well. But for some reason, starting around 1980, the two factors uncoupled, and food intake started to rise despite exercise continuing to decrease.

Guyenet discusses many different reasons this might have happened, including stress-related overeating, poor sleep, and quick prepackaged food. But the ideas he keeps coming back to again and again are food reward and satiety.

In the 1970s, scientists wanted to develop new rat models of obesity. This was harder than it sounded; rats ate only as much as they needed and never got fat. Various groups tried to design various new forms of rat chow with extra fat, extra sugar, et cetera, with only moderate success – sometimes they could get the rats to eat a little too much and gradually become sort of obese, but it was a hard process. Then, almost by accident, someone tried feeding the rats human snack food, and they ballooned up to be as fat as, well, humans. The book:

Palatable human food is the most effective way to cause a normal rat to spontaneously overeat and become obese, and its fattening effect cannot be attributed solely to its fat or sugar content.

So what does cause this fattening effect? I think the book’s answer is “no single factor, but that doesn’t matter, because capitalism is an optimization process that designs foods to be as rewarding as possible, so however many different factors there are, every single one of them will be present in your bag of Doritos”. But to be more scientific about it, the specific things involved are some combination of sweet/salty/umami tastes, certain ratios of fat and sugar, and reinforced preferences for certain flavors.

Modern food isn’t just unusually rewarding, it’s also unusually bad at making us full. The brain has some pretty sophisticated mechanisms to determine when we’ve eaten enough; these usually involve estimating food’s calorie load from its mass and fiber level. But modern food is calorically dense – it contains many more calories than predicted per unit mass – and fiber-poor. This fools the brain into thinking that we’re eating less than we really are, and shuts down the system that would normally make us feel full once we’ve had enough. Simultaneously, the extremely high level of food reward tricks the brain into thinking that this food is especially nutritionally valuable and that it should relax its normal constraints.

Adding to all of this is the so-called “buffet effect”, where people will eat more calories from a variety of foods presented together than they would from any single food alone. My mother likes to talk about her “extra dessert stomach”, ie the thing where you can gorge yourself on a burger and fries until you’re totally full and couldn’t eat another bite – but then mysteriously find room for an ice cream sundae afterwards. This is apparently a real thing that’s been confirmed in scientific experiments, and a major difference between us and our ancestors. The !Kung Bushmen, everyone’s go-to example of an all-natural hunter-gatherer tribe, apparently get 50% of their calories from a single food, the mongongo nut, and another 40% from meat. Meanwhile, we design our meals to include as many unlike foods as possible – for example, a burger with fries, soda, and a milkshake for dessert. This once again causes the brain to relax its usual strict constraints on appetite and let us eat more than we should.

The book sums all of these things up into the idea of “food reward” making some foods “hyperpalatable” and “seducing” the reward mechanism in order to produce a sort of “food addiction” that leads to “cravings”, the “obesity epidemic”, and a profusion of “scare quotes”.

I’m being a little bit harsh here, but only to highlight a fundamental question. Guyenet goes into brilliant detail about things like the exact way the ventral tegmental area of the brain responds to food-related signals, but in the end, it all sounds suspiciously like “food tastes good so we eat a lot of it”. It’s hard to see where exactly this differs from the paradigm that he dismisses as “attributing leanness to wise voluntary decisions and a strong character…to make lean people feel smug”. Yes, food tastes good so we eat a lot of it. And Reddit is fun to read, but if someone browses Reddit ten hours a day and doesn’t do any work then we start speculating about their character, and maybe even feeling smug. This part of the book, taken alone, doesn’t really explain why we shouldn’t be doing that about weight too.

III.

There is only one fat person on the Melanesian island of Kitava – a businessman who spends most of his time in modern urbanized New Guinea, eating Western food. The Kitavans have enough food, and they live a relaxed tropical lifestyle that doesn’t demand excessive exercise. But their bodies match caloric intake to expenditure with impressive precision. So do the !Kung with their mongongo nuts, Inuit with their blubber, et cetera.

And so do Westerners who limit themselves to bland food. In 1965, some scientists locked people in a room where they could only eat nutrient sludge dispensed from a machine. Even though the volunteers had no idea how many calories the nutrient sludge was, they ate exactly enough to maintain their normal weight, proving the existence of a “sixth sense” for food caloric content. Next, they locked morbidly obese people in the same room. They ended up eating only tiny amounts of the nutrient sludge, one or two hundred calories a day, without feeling any hunger. This proved that their bodies “wanted” to lose the excess weight and preferred to simply live off stored fat once removed from the overly-rewarding food environment. After six months on the sludge, a man who weighed 400 lbs at the start of the experiment was down to 200, without consciously trying to reduce his weight.

In a similar experiment going the opposite direction, Ethan Sims got normal-weight prison inmates to eat extraordinary amounts of food – yet most of them still had trouble gaining weight. He had to dial their caloric intake up to 10,000/day – four times more than a normal person – before he was able to successfully make them obese. And after the experiment, he noted that “most of them hardly had any appetite for weeks afterward, and the majority slimmed back down to their normal weight”.

What is going on here? Like so many questions, this one can best be solved by grotesque Frankenstein-style suturing together of the bodies of living creatures.

In the 1940s, scientists discovered that if they damaged the ventromedial hypothalamic nucleus (VMN) of rats, the rats would basically never stop eating, becoming grotesquely obese. They theorized that the VMN was a “satiety center” that gave rats the ability to feel full; without it, they would feel hungry forever. Later on, a strain of mutant rats was discovered that seemed to naturally have the same sort of issue, despite seemingly intact hypothalami. Scientists wondered if there might be a hormonal problem, and so they artificially conjoined these rats to healthy normal rats, sewing together their circulatory systems into a single network. The result: when a VMN-lesioned rat was joined to a normal rat, the VMN-lesioned rat stayed the same, but the normal rat stopped eating and starved to death. When a mutant rat was joined to a normal rat, the normal rat stayed the same and the mutant rat recovered and became normal weight.

The theory they came up with to explain the results was this: fat must produce some kind of satiety hormone, saying “Look, you already have a lot of fat, you can feel full and stop eating now”. The VMN of the hypothalamus must detect this message and tell the brain to feel full and stop eating. So the VMN-lesioned rats, whose detector was mostly damaged, responded by never feeling full, eating more and more food, and secreting more and more (useless) satiety hormone. When they were joined to normal rats, their glut of satiety hormones flooded the normal rats – and their normal brain, suddenly bombarded with “YOU ALREADY HAVE WAY TOO MUCH FAT” messages, stopped eating entirely.

The mutant rats, on the other hand, had lost the ability to produce the satiety hormone. They, too, felt hungry all the time and ate everything. But when they were joined to a normal rat, the normal levels of satiety hormone flowed from the normal rat into the mutant rat, reached the fully-functional detector in their brains, and made them feel full, curing their obesity.

Skip over a lot of scientific infighting and unfortunate priority disputes and patent battles, and it turns out the satiety hormone is real, exists in humans as well, and is called leptin. A few scientists managed to track down some cases of genetic leptin deficiency in humans, our equivalent of the mutant rats, and, well…

Usually they are of normal birth weight and then they’re very, very hungry from the first weeks and months of life. By age one, they have obesity. By age two, they weigh 55-65 pounds, and their obesity only accelerates from there. While a normal child may be about 25% fat, and a typical child with obesity may be 40% fat, leptin-deficient children are up to 60% fat. Farooqi explains that the primary reason leptin-deficient children develop obesity is that they have “an incredible drive to eat”…leptin-deficient children are nearly always hungry, and they almost always want to eat, even shortly after meals. Their appetite is so exaggerated that it’s almost impossible to put them on a diet: if their food is restricted, they find some way to eat, including retrieving stale morsels from the trash can and gnawing on fish sticks directly from the freezer. This is the desperation of starvation […]

Unlike normal teenagers, those with leptin deficiency don’t have much interest in films, dating, or other teenage pursuits. They want to talk about food, about recipes. “Everything they do, think about, talk about, has to do with food” says [Dr.] Farooqi. This shows that the [leptin system] does much more than simply regulate appetite – it’s so deeply rooted in the brain that it has the ability to hijack a broad swath of brain functions, including emotions and cognition.

It’s the leptin-VNM-feedback system (dubbed the “lipostat”) that helps people match their caloric intake to their caloric requirements so impressively. The lipostat is what keeps hunter-gatherers eating exactly the right number of mongongo nuts, and what keeps modern Western overeaters at much closer to the right weight than they could otherwise expect.

The lipostat-brain interface doesn’t just control the raw feeling of hunger, it seems to have a wide range of food-related effects, including some on higher cognition. Ancel Keys (of getting-blamed-for-everything fame) ran the Minnesota Starvation Experiment on some unlucky conscientious objectors to World War II. He starved them until they lost 25% of their body weight, and found that:

Over the course of their weight loss, Keys’s subjects developed a remarkable obsession with food. In addition to their inescapable, gnawing hunger, their conversations, thoughts, fantasies, and dreams revolved around food and eating – part of a phenomenon Keys called “semistarvation neurosis”. They became fascinated by recipes and cookbooks, and some even began collecting cooking utensils. Like leptin-deficient adolescents, their lives revolved around food. Also like leptin-deficient adolescents, they had very low leptin levels due to their semi-starved state.

Unsurprisingly, as soon as the experiment ended, they gorged themselves until they were right back at their pre-experiment weights (but no higher), at which point they lost their weird food obsession.

Just as a well-functioning lipostat is very good at keeping people normal weight, a malfunctioning lipostat is very good at keeping people obese. Fat people seem to have “leptin resistance”, sort of like the VMN-lesioned rats, so that their bodies get confused about how much fat they have. Suppose a healthy person weighs 150 lbs, his body is on board with that, and his lipostat is set to defend a 150 lb set point. Then for some reason he becomes leptin-resistant, so that the brain is only half as good at detecting leptin as it should be. Now he will have to be 300 lbs before his brain “believes” he is the right weight and stops encouraging him to eat more. If he goes down to a “mere” 250 lbs, then he will go into the same semistarvation neurosis as Ancel Keys’ experimental subjects and become desperately obsessed with food until they get back up to 300 again. Or his body will just slow down metabolism until his diet brings him back up. Or any of a bunch of other ways the lipostat has to restore weight when it wants to.

This explains the well-known phenomenon where contestants on The Biggest Loser who lose 200 or 300 pounds for the television camera pretty much always gain it back after the show ends. Even though they’re highly motivated and starting from a good place, their lipostat has seized on their previous weight as the set point it wants to defend, and resisting the lipostat is somewhere between hard and impossible. As far as I know, nobody has taken Amptoons up on their challenge to find a single peer-reviewed study showing any diet that can consistently bring fat people to normal weight and keep them there. After a certain level of lipostat dysregulation, “solving” weight problems by diet and exercise becomes hard-to-impossible, and the people who loudly insist otherwise tend to kind of be jerks.

And alas, it doesn’t seem to work to just inject leptin directly. As per Guyenet

People with garden variety obesity already have high levels of leptin…while leptin therapy does cause some amount of fat loss, it requires enormous doses to be effective – up to forty times the normal circulating amount. Also troubling is the extremely variable response, with some people losing over thirty pounds and others losing little or no weight. This is a far cry from the powerful fat-busting effect of leptin in rodents. [Leptin as] the new miracle weight-loss drug never made it to market.

This disappointment forced the academic and pharmaceutical communities to confront a distressing possibility: the leptin system defends vigorously against weight loss, but not so vigorously against weight gain. “I have always thought, and continue to believe,” explained [leptin expert Rudy] Leibel, “that the leptin hormone is really a mechanism for detecting deficiency, not excess.” It’s not designed to constrain body fatness, perhaps because being too fat is rarely a problem in the wild. Many researchers now believe that while low leptin levels in humans engage a powerful starvation response that promotes fat gain, high leptin levels don’t engage an equally powerful response that promotes fat loss.

Yet something seems to oppose rapid fat gain, as Ethan Sims’ overfeeding studies (and others) have shown. Although leptin clearly defends the lower limit of adiposity, the upper limit may be defended by an additional, unidentified factor – in some people more than others.

This is the other half of the uncomfortable dichotomy that makes me characterize The Hungry Brain as “wishy-washy”. The lipostat is a powerful and essentially involuntary mechanism for getting weight exactly where the brain wants, whether individual dieters are cooperative or not. Here it looks like obesity is nobody’s fault, unrelated to voluntary decisions, and that the standard paradigm really is just an attempt by lean people to feel smug. Practical diet advice starts to look like “inject yourself with quantities of leptin so massive that they overcome your body’s resistance”. How do we connect this with the other half of the book, the half with food reward and satiety and all that?

IV.

With more rat studies!

Dr. Barry Levin fed rats either a healthy-rat-food diet or a hyperpalatable-human-food diet, then starved and overfed them in various ways. He found that the rats defended their obesity set points in the expected manner, but that the same rats defend different set points depending on their diets. Rats on healthy-rat-food defended a low, healthy-for-rats set point; rats on hyperpalatable-human-food defended a higher set point that kept them obese.

That is, suppose you give a rat as much Standardized Food Product as it can eat. It eats until it weighs 8 ounces, and stays that weight for a while. Then you starve it until it only weighs 6 ounces, and it’s pretty upset. Then you let it eat as much as it wants again, and it overeats until it gets back to 8 ounces, then eats normally and maintains that weight.

But suppose you get a rat as many Oreos as it can eat. It eats until it weighs 16 ounces, and stays that weight for a while. Then you starve it until it only weighs 6 ounces. Then you let it eat as much as it wants again, and this time it overeats until it gets back to 16 ounces, and eats normally to maintain that weight.

Something similar seems to happen with humans. A guy named Michel Cabanac ran an experiment in which he put overweight people on two diets. In the first diet, they ate Standardized Food Product, and naturally lost weight since it wasn’t very good and they didn’t eat very much of it. In the second diet, he urged people to eat less until they matched the first group’s weight loss, but to keep eating the same foods as normal – just less of them. The second group reported being hungry and having a lot of trouble dieting; the first group reported not being hungry and not having any trouble at all.

Guyenet concludes:

Calorie-dense, highly rewarding food may favor overeating and weight gain not just because we passively overeat it but also because it turns up the set point of the lipostat. This may be one reason why regularly eating junk food seems to be a fast track to obesity in both animals and humans…focusing the diet on less rewarding foods may make it easier to lose weight and maintain weight loss because the lipostat doesn’t fight it as vigorously. This may be part of the explanation for why all weight-loss diets seem to work to some extent – even those that are based on diametrically opposed principles, such as low-fat, low-carbohydrate, paleo, and vegan diets. Because each diet excludes major reward factors, they may all lower the adiposity set point somewhat.

(this reminds me of the Shangri-La Diet, where people would drink two tablespoons of olive oil in the morning, then find it was easy to diet without getting hungry during the day. People wondered whether maybe the tastelessness of the olive oil had something to do with it. Could it be that the olive oil is temporarily bringing the lipostat down to its “bland food” level?)

Why should some food make the lipostat work better than other food? Guyenet now gets to some of his own research, which is on a type of brain cell called a POMC neuron. These neurons produce various chemicals, including a sort of anti-leptin called Neuropeptide Y, and they seem to be a very fundamental part of the lipostat and hunger system. In fact, if you use superprecise chemical techniques to kill NPY neurons but nothing else, you can cure obesity in rats.

The area of the hypothalamus with POMC neurons seem to be damaged in overweight rats and overweight humans. Microglia and astrocytes, the brain’s damage-management and repair cells, proliferated in appetite-related centers, but nowhere else. Maybe this literal damage corresponds to the metaphorically “damaged” lipostat that’s failing to maintain weight normally, or the “damaged” leptin detector that seems to be misinterpreting the body’s obesity?

In any case, eating normal rat food for long enough appears to heal this damage:

Our results suggest that obese rodents suffer from a mild form of brain injury in an area of the brain that’s critical for regulating food intake and adiposity. Not only that, but the injury response and inflammation that developed when animals were placed on a fattening diet preceded the development of obesity, suggesting that this brain injury could have played a role in the fattening process.

Guyenet isn’t exactly sure what aspect of modern diets cause the injury:

Many researchers have tried to narrow down the mechanisms by which this food causes changes in the hypothalamus and obesity, and they have come up with a number of hypotheses with varying amounts of evidence to support them. Some researchers believe the low fiber content of the diet precipitates inflammation and obesity by its adverse effects on bacterial populations in the gut (the gut microbiota). Others propose that saturated fat is behind the effect, and unsaturated fats like olive oil are less fattening. Still others believe the harmful effects of overeating itself, including the inflammation caused by excess fat and sugar in the bloodstream and in cells, may affect the hypothalamus and gradually increase the set point. In the end, these mechanisms could all be working together to promote obesity. We don’t know all the details yet, but we do know that easy access to refined, calorie-dense, highly rewarding food leads to fat gain and insidious changes in the lipostat in a variety of species, including humans. This is particularly true when the diet offers a wide variety of sensory experiences, such as the hyperfattening “cafeteria diet” we encountered in chapter 1.

Personally, I believe overeating itself probably plays an important role in the process that increases the adiposity set point. In other words, repeated bouts of overeating don’t just make us fat; they make our bodies want to stay fat. This is consistent with the simple observation that in the United States, most of our annual weight gain occurs during the six-week holiday feasting period between Thanksgiving and the new year, and that this extra weight tends to stick with us after the holidays are over…because of some combination of food quantity and quality, holiday feasting ratchets up the adiposity set point of susceptible people a little bit each year, leading us to gradually accumulate and defend a substantial amount of fat. Since we also tend to gain weight at a slower rate during the rest of the year, intermittent periods of overeating outside of the holidays probably contribute as well.

How might this happen? We aren’t entirely sure, but researchers, including Jeff Friedman, have a possible explanation: excess leptin itself may contribute to leptin resistance. To understand how this works, I need to give you an additional piece of information: Leptin doesn’t just correlate with body fat levels; it also responds to short-term changes in calorie intake. So if you overeat for a few days, your leptin level can increase substantially, even if your adiposity has scarcely changed (and after your calorie intake goes back to normal, so does your leptin). As an analogy for how this can cause leptin resistance, imagine listening to music that’s too loud. At first, it’s thunderous, but eventually, you damage your hearing, and the volume drops. Likewise, when we eat too much food over the course of a few days, leptin levels increase sharply, and this may begin to desensitize the brain circuits that respond to leptin. Yet Rudy Leibel’s group has also shown that high leptin levels alone aren’t enough – the hypothalamus also seems to require a second “hit” for high leptin to increase the set point of the lipostat. This second hit could be the brain injury we, and others, have identified in obese rodents and humans.

And he isn’t sure exactly what aspect of the normal rodent diet promotes the healing:

I did do some research in mice suggesting that unrefined, simple food does reverse the brain changes and the obesity. I don’t claim that it’s all attributable to the blandness though– the two diets differed in many respects (palatability, calorie density, fiber content, macronutrient profile, fatty acid profile, content of nonessential nutrients like polyphenols). Also, we don’t know how well the finding applies to humans yet. One of the problems is that it’s very hard to get a group of humans to adhere strictly to a whole food diet for long enough to study its long-term effects on appetite and body fatness. People are very attached to the pleasures of the palate!

But all of this together seems to point to a potential synthesis between the hyperpalatability and lipostat models. For most of human history, the lipostat faced only mild stresses and was able to maintain a normal weight without much trouble. Modern society has been incentivized to produce hyperpalatable, low-satiety food as superstimuli. This modern food is able to overwhelm normal satiety cues and produce short-term overeating. And for some reason this short-term overeating raises the lipostat’s set point (maybe because of brain damage and leptin resistance), causing long-term weight gain in a way that is very difficult to reverse.

V.

But I still have trouble reconciling these two points of view.

A couple of days ago, I walked by an ice cream store. I’d just finished lunch, and I wasn’t very hungry at the time, but it looked like really good ice cream, and it was hot out, so I gave in to temptation and ate a 700 calories sundae. Does this mean:

1. Based on the one pound = 3500 calories heuristic, I have now gained 0.2 lbs. That extra weight will stay with me my whole life, or at least until some day when I diet and eat 700 calories less than my requirement. If I were to eat ice cream like this a hundred times, I would gain twenty pounds.

2. My lipostat adjusts for the 700 extra calories, and causes me to exercise more, or ramp up my metabolism, or burn more brown fat, or eat less later on, or something. I don’t gain any weight, and eating the ice cream was that rarest of all human experiences, a completely guiltless pleasure. I should eat ice cream whenever I feel like it, or else I am committing the sin of denying myself a lawful pleasure.

3. My lipostat will more or less take care of the ice cream today, and I won’t notice the 0.2 pounds on the scale, but it is very gradually doing hard-to-measure damage to my hypothalamus, and if I keep eating ice cream like this, then one day when I’m in my forties I’m going to wake up weighing three hundred pounds, and no diet will ever be able to help me.

4. Not only will I gain 0.2 pounds immediately, but my lipostat will adjust to want to be 0.2 pounds heavier, and I will never lose it, even if I try really hard to diet later.

5. The above scenario is impossible. Even if I think I just ate ice cream because it looked good, in reality I was driven to do it by my lipostat’s quest for caloric balance. Any feeling of choice in the matter is an illusion.

I think the reason this is so confusing is because the real answer is “it could be any one of these, depending on genetics.”

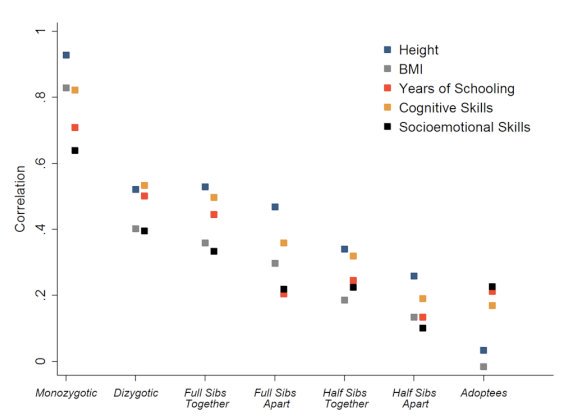

Note the position of the grey squares representing BMI

Right now, within this culture, variation in BMI is mostly genetic. This isn’t to say that non-genetic factors aren’t involved – the difference between 1800s America and 2017 America is non-genetic, and so is the difference between the perfectly-healthy Kitavans on Kitava and the one Kitavan guy who moved to New Guinea. But once everyone alike is exposed to the 2017-American food environment, differences between the people in that environment seem to be really hereditary and not-at-all-related to learned behavior. Guyenet acknowledges this:

Genes explain that friend of yours who seems to eat a lot of food, never exercises, and yet remains lean. Claude Bouchard, a genetics researcher at the Pennington Biomedical Research Center in Baton Rouge, Louisiana, has shown that some people are intrinsically resistant to gaining weight even when they overeat, and that this trait is genetically influenced. Bouchard’s team recruited twelve pairs of identical twins and overfed each person by 1,000 calories per day above his caloric needs, for one hundred days. In other words, each person overate the same food by the same amount, under controlled conditions, for the duration of the study.

If overeating affects everyone the same, then they should all have gained the same amount of weight. Yet Bouchard observed that weight gain ranged from nine to twenty-nine pounds! Identical twins tended to gain the same amount of weight and fat as each other, while unrelated subjects had more divergent responses…Not only do some people have more of a tendency to overeat than others, but some people are intrinsically more resistant to gaining fat even if they do overeat.

The research of James Levine, an endocrinologist who works with the Mayo Clinic and Arizona State University, explains this puzzling phenomenon. In a carefully controlled overfeeding study, his team showed that the primary reason some people readily burn off excess calories is that they ramp up a form of calorie-burning called “non-exercise activity thermogenesis” (NEAT). NEAT is basically a fancy term for fidgeting. When certain people overeat, their brains boost calorie expenditure by making them fidget, change posture frequently, and make other small movements throughout the day. It’s an involuntary process, and Levine’s data show that it can incinerate nearly 700 calories per day. The “most gifted” of Levine’s subjects gained less than a pound of body fat from eating 1,000 extra calories per day for eight weeks. Yet the strength of the response was highly variable, and the “least gifted” of Levine’s subjects didn’t increase NEAT at all, shunting all the excess calories into fat tissue and gaining over nine pounds of body fat…

Together, these studies offer indisputable evidence that genetics plays a central role in obesity and dispatch the idea that obesity is primarily due to acquired psychological traits.

These studies suggest that one way genetics affects obesity is by altering the tolerance level of the lipostat. Genetically privileged people may have very finicky lipostats that immediately burn off any extra calories they eat, and which never become dysregulated. Genetically unlucky people may have weak lipostats which fail to defend against weight gain, or which are too willing to adjust their set point up in the presence of an unhealthy food environment.

So, given how many people seem to have completely different weight-gain-related experiences to each other, the wishy-washyness here might be a feature rather than a bug.

One reason I’ve always found genetics so exciting is that there are all these fields – nutrition is a great example, but this applies at least as much to psychiatry – where everyone has wildly different personal experiences, and where there’s a large and vocal population of people who say that the research is exactly the opposite of their lived experiences. People have tried to shoehorn the experiences to fit the research, with various levels of plausibility and condescendingness. And for some reason, it’s always really hard to generate the hypothesis “people’s different experiences aren’t an illusion; people are genuinely really different”. Once you start looking at genetics, everything sort of falls into place, and ideas which seemed wishy-washy or self-contradictory before are revealed as just reflecting the diversity of nature. People who were previously at each other’s throats disputing different interpretations of the human condition are able to peacefully agree that there are many different human conditions, and that maybe we can all just get along. The Hungry Brain and other good books in its vein offer a vision for how we might one day be able to do that in nutrition science.

VI.

Lest I end on too positive a note, let me reiterate the part where happiness is inherently bad and a sort of neo-Puritan asceticism is the only way to avoid an early grave.

There’s a sort of fatalism to talking about “food reward”. If the enemy were saturated fat, we could just stick with the sugary sweetness of Coca-Cola. If the enemy were carbohydrates, we could go out for steak every night. But what do we do if the enemy is deliciousness itself?

A few weeks ago Guyenet announced The Bland Food Cookbook, a collection of tasteless recipes guaranteed to be low food-reward and so discourage overeating. It was such a natural extension of his philosophy that it took me a whole ten seconds to realize it was an April Fools joke. But why should it be? Shouldn’t this be exactly the sort of thing we’re going for?

I asked him, and he responded that:

If I thought enough people would actually be capable of following the diet, I would consider making such a cookbook non-ironically. The second point I want to make here is that there are many ways to lose weight, and deliberately reducing food reward is only one of them. You could also exercise, eat a low-calorie-density diet, eat a high-protein diet, restrict a macronutrient, restrict animal foods, restrict plant foods, eat nothing but potatoes. Most approaches overlap with a low-reward diet to varying degrees, but I don’t think the low reward value encapsulates everything about why every weight loss strategy works. BTW, low-carb folks often have a knee-jerk reaction to the low-reward thing that goes something like this: “I eat food that’s delicious, such as steaks, bacon, butter, etc. It’s not low in reward.” But it is low reward in the sense that you’re cutting out a broad swath of foods, and an entire macronutrient, that the brain very much wants you to eat. Eating more of a particular category of rewarding food doesn’t completely make up for the fact that you’re cutting out a whole other category of rewarding food that you would avidly consume if you weren’t restricting yourself.

So things aren’t maximally bad. And hunter-gatherers enjoy their healthy diets just fine. And certainly there are things like steak and wine and so on which are traditionally “good food” without being hyperprocessed hyperpalatable junk food. But if you really enjoy a glass of Chardonnay, is that “food reward” in a sense that’s potentially dangerous? Is anything safe? What about mongongo nuts? Is there anywhere we can get them?

At least the consolation of things making a little more sense. One thing that always used to bother me was the so-called “ice cream diet” – that is, if you eat a 700-calorie ice cream sundae for breakfast, lunch, and dinner every day, that’ll be only 2100 calories – around the average person’s daily requirement, and low enough for many people to lose weight. Why wouldn’t you want to do that? The idea of junk food being inherently damaging – while it has a bit of Puritan feel to it – at least fits our intuitions on these sorts of things and gives us a first step towards reconciling the conventional wisdom and the calorie math.

Overall I strongly recommend The Hungry Brain for everything I talk about here and for some other good topics I didn’t even get to (stress, sleep, economics). I would also recommend Guyenet’s other writing, especially his debate with Dr. David Ludwig on the causes of obesity (Part 1, Part 2, Part 3. I also recommend the list of diet tips that Guyenet gives at the end of the book. I won’t give them all away here – he’s been nice enough to me that maybe I should repay him by not reprinting the entire text of his book online for free. But it’s similar to a lot of standard advice for healthy living, albeit with more interesting reasoning behind it. Did you know that exercise might help stabilize the lipostat? Or that protein might do the same? Also, one piece of advice you might not hear anywhere else – potatoes are apparently off-the-charts in terms of satiety factor and may be one of the single best things to diet on.

And speaking of good things to diet on…

(note that this next part is my own opinion, not taken from The Hungry Brain or endorsed by Stephan Guyenet)

Slate Star Codex’s first and most loyal sponsor is MealSquares, a “nutritionally complete” food product sort of like a whole-foods-based, protein-rich, solid version of Soylent (it looks and tastes basically like a scone). I’m having some trouble writing this paragraph, because I want to recommend them as potentially dovetailing with The Hungry Brain‘s philosophy of nutrition without using phrases that might make MealSquares Inc angry at me like “bland”, “low food reward”, or “not hyperpalatable”. I think the best I can come up with is “unlikely to injure your hypothalamus”. So, if you’re looking for an easy way to quit the junk food and try a low-variety diet that’s unlikely to injure your hypothalamus, I recommend MealSquares as worth a look.

I tried MealSquares a while back, based on the sidebar advertisement, and liked them pretty well (“liked” in the “this works well for me” sense, not the “food reward” sense). But I don’t see how anyone who’s tried one could call them “hyperpalatable”.

Seconded. I’d rate them as solidly “dry vegan cafeteria scone”. (Although they aren’t, to be clear, vegan.) Not bad, but also not something you’d buy if you enjoyed eating.

That’s exactly the point. I too have had them. Note that it’s “not hyperpalatable”.

I enjoy food, a lot. But when travelling (which I do quite a bit for work), significantly less so – the options easily available to a weary traveller in a business district hotel (ie, room service, hotel restaurants and fast food) tends to be of the “hyperpalatable” kind, and is also high-calorie and have other properties that are commonly (but possibly incorrectly), considered “unhealthy”. And that’s before the temptation of dessert and a glass of wine or two kicks in. It’s also typically quite ridiculously expensive, and even when I don’t pay for it myself, I can’t help but recoiling a bit at what they get away with.

Long story short(er), I’ve taken to “Jake” which is a meal-shake. Same general concept as MealSquares as far as I can tell, except it’s a shake which does add a tiny bit of logistics. It’s, well, as bland as you could imagine a colourless powder mixed with tap water would be (it has a very faint vanilla flavour), but I get perfectly satiated, and I’ve been able to cut out “travelling-food” entirely. Last week I even brought my shake to the gym and drank it on the stationary bike while watching Netflix on my phone #lifehack 🙂

I couldn’t imagine replacing pretty much any “real meals” in my life with Jake (weeknight “can’t be bothered to cook” take away is probably next on the hit-list, though), but it’s definitely very powerful for on-the-go scenarios where “real meals” can be hard to come by (and, again, it would seem MealSquares could be used in the same way).

I’ve replaced my work lunches with mealsquares and an apple a few months ago, after reading about them on this site. I’ve dropped somewhere around 15lbs during that time. I credit the mealsquares lack of deliciousness. They taste acceptable, but they aren’t tasty. There is something about them that is very filling, and the apple is there to occupy me long enough for the satiation to kick in (mealsquares are small and it doesn’t take long to eat one).

I’ve always imagined mealsquares as low-quality lembas bread. Would this be accurate?

Funny, that’s what my wife calls them. I’m not sure how to answer the quality part. They taste vaguely like some foreign pastry that you’ll try once but wont reach for another unless you are really hungry. Chocolaty/whole bready/nutty substance that’s a bit too dry, and very thick. So the very opposite of angel cake. They are very filling. I’m not hungry for hours after eating one, despite it being slightly smaller than a slice of bread. I am not a light eater.

There’s a Tolkien word for that! Cram, made by the Men of Dale: it gives you the strength to keep marching for a day, but unlike lembas, it’s very much not tasty.

Well, now I know where cram rations in Nethack came from.

Exactly! MealSquares are closer to lembas than cram, but not by all that much.

Kinda, except they don’t have preservatives, and if you don’t keep them sealed and/or in your fridge they go bad pretty fast.

Last year I switched to eating a *very* regular diet for lunch and dinner. Breakfast was a single hard boiled egg and 2 pieces of sausage plus black coffee. Lunch was 8 to 10 ounces of plain or vanilla yoghurt with a scoop of coco flavored unsweetened whey powder to up the protein level.

This is pretty satisfying, and depending on workload (I do a combination of Linux administration, shell programming, and some sort of low to mid level management work, which is to say lots of brain engaged which sucks up glycogen) I get a little hungry about 3:30 or 4 PM. I’ve shifted my lunch time a bit to try to push that out to “quitting time”, but that’s not worked well.

These are also things that are readily available when I travel (which I’m doing a lot less this year than last).

I lost about 15 pounds of fat (and picked up some muscle from exercise) last year. Some of the fat came back, and the muscle stayed.

I thought I tended to get hungrier on brain-heavy days. Nice to know I wasn’t just imagining the effect.

I also tried the meal squares based on the sidebar ad here, and found them completely unpalatable. After failing to eat more than a couple bites or to convince anyone in my family to eat more than a couple bites, they ended up in the compost heap.

I’ve also tried soylent, and found it similarly unpalatable, though my spouse found soylent to be acceptable.

If I’m going to eat bland food, I tend to stick with rice or oatmeal.

I tried them too. I didn’t like them and couldn’t eat more than a few bites, which was disappointing because those few bites were absurdly filling.

On the other hand, I gave the remaining ones to someone else, and she eats them just fine. She uses them mostly as a cafeteria food replacement. So it seems one’s mileage may vary.

Strange, unlike apparently every other commenter so far, I found meal squares to be way too sweet. It’s more like (dry) cake than something I’d eat as a meal. It’s certainty sweeter than…noninvented(?)… food, aside from fruit and some outliers like sweet potato.

I drink soylent, which is also sweet, but not quite as bad.

It’s so interesting that most people here don’t find MealSquares hyperpalatable! I ordered them a couple of times and ended up binging on them. They were so convenient and tasty. I wish they could make a version without any sweeteners added. As it is, I find it hard to resist eating too many of them at a time!

As a not-quite-counterpoint but still related; I put in for an order of MealSquares based on this post, despite having seen it in the sidebar a number of times before. Partly it was just convenient timing as I’ve been getting interested in meal replacements again (my previous experience with Soylent was… not great), but also admittedly because there’s something deeply appealing to me about pitching one of your sponsors as “not hyperpalatable” and (justifiably!) expecting that to be effective.

If you’re hungry enough – perhaps because you have eating problems – just having everything in sufficient quantities tastes hyperpalatable. (Speaking from personal experience.)

I don’t really get this argument. We don’t have to exactly match energy intake and expenditure every single day, because what determines the weight gain over a year is the average amount you ate over the entire year. Can’t it just be that people eat slightly random amounts every day, and exercises random amounts every day, and on the scale of years it averages out until we reach the weight where the negative feedback from caloric requirements matches the amount you tend to consume?

Like, tautologically, if someone’s weight is stable, then (food – work) can not vary very far from zero, but in a purely passive model that could be just because the amount of food they eat does not vary much and the amount of work they do also does not vary much. In order to test if there is any active control by the brain, it seems you at least have to have some information about how much variance there is in food intake and work, so we can compare it to how much the body weight varies.

Okay, I’ve gotten enough negative feedback about this point (phrased in various different ways) that I’m just going to give up and delete it.

I wouldn’t delete it entirely. The first paragraph is still accurate. Yes, long-term averaging does help some, but the fact that there’s a very good control system in charge of almost everyone’s weight is very important.

I’m against deleting it, because I just saw it quoted in the comments and thought, “what an interesting insight…wait was that in the article?”.

I think it’s an important point.

Sure, what’s important is that they are 98% accurate on average, over the course of the year, not that they are 98% accurate every single day. But even that seems to me to be pretty clearly false. There must be some negative feedback, either in hunger or in energy consumption.

I resisted the idea of calorie counting, until a question I asked on an open thread (“how can I tell when I eat enough food?”) suggested it anyway, and I’ve now been tracking calories for nearly a year, skipping times when I cannot due to travel.

I have a pretty good idea of how many calories I need to eat to lose, maintain, or gain weight. It took a few months of trial-and-error but I’m there. I am slightly nervous that when I next go back into weight-cutting mode that It Won’t Work Any More, but so far it seems like I can choose my weight.

I read Scott’s wonderful essay so I’m not saying this will work for everybody.

We’re talking about the accuracy of people who aren’t consciously trying to count calories, who haven’t even heard of a calorie.

Of course, but noting that it is “either” doesn’t help much—the rest of the article wants to talk about feedback in the form of hunger/fidgeting/etc, mediated by the brain. But (as quoted text acknowledges), there is also feedback from increasing energy consumption (which does not need to be mediated by the brain). In order to talk about the lipostat you need to distinguish those two mechanisms, and this argument doesn’t do that.

Potatoes are a diet food?

Maybe that’s why I lose weight during Passover.

I’m delighted to note that fries are made of potatoes.

Potatoes soaked in fat…

But apparently it’s not the fat that’s bad; it’s the tastiness itself.

Well, it’s both tastiness and caloric density, right? French fries have both, to a much greater extent then potatoes do.

Passover seems like the ideal weight-loss ritual based on this book. All my jewish friends find matzos hyper-unpalatable, and food variety is restricted.

Considering the Wall Street Journal article a couple weeks ago about all sorts of fancy matzo-flavored foods, I’m guessing not everyone agrees with your friends? When I tried matzo myself (I’m a gentile, so it’s pretty rare for me) I found it fairly good-tasting as crackers go.

I’ve gotten the same response from some goyim I know. I think the disparity of feelings between Jews and non-Jews largely comes from Jews associating it with periods of practicing highly inconvenient food restrictions during which we have to (by tradition, if not necessity) use matzoh as a bread replacement. Many things taste worse than matzoh, but few things taste worse in the moment than shmurah matzoh covered with sauce and cheese when you really want pizza. It probably doesn’t help that we also participate in religious rituals in which we sit at a dinner table for up to two hours without eating anything substantial, after which we’re compelled to eat (according to some) a whole matzoh plain as the first thing.

(Followed, of course, by more matzoh with horseradish and apples).

Out of curiosity, if Jews don’t like Matzo during Passover, then why not other forms of unleavened bread that are more soft or moist, like tortillas, or roti?

@Alexp

It’s seems to be against the spirit of the holiday. But kosher restaurants do use non-matza bread replacements.

I love matzos. And if you add haroset to it… Very, very palatable. Don’t eat much bread normally, btw, so it’s not super-inconvenient for me. Wouldn’t probably enjoy eating the whole leaf plain… though if it’s the fancy one, with eggs, also is very palatable. Same goes for matzah brei.

Hm — how clear is it that the problem is just food reward, though? I mean, yes, one of the hypotheses for what’s damaging the hypothalamus is that it’s just overeating, but it could also be something more specific (such as low fiber content). Actually, I don’t really see how the “it’s just due to overeating” idea is consistent with the “there is some second hit that is necessary” idea. If the second hit is the hypothalamic damage, but the hypothalamic damage is caused by overeating…? Well, I guess depending on what exactly the “second hit” hypothesis is, I guess it could still be technically a “second hit” if overeating causes the damage by means other than leptin, but a bit confusing terminology then. And the fact that lab animals have been getting fatter over time despite their diets remaining the same, as has been mentioned on this blog before, would indeed seem to suggest that there is another factor beside genes and overeating — which could be (or be one cause of) the “second hit” discussed above, perhaps?

Could it be something related to the generational testosterone decline in Western males?

If I understand correctly, the causes for it are unclear, but if there is some environmental factor (some kind of industrial pollutant/flavoring/additive that somehow gets into junk food?) that can have significant endocrine effects then I wouldn’t be surprised if it was involved in disregulation of the lipostat, whether through testosterone itself (which is involved in fat balance) or other hormones that affect and are regulated by the hypothalamus.

Women are still obese too, so it can’t be through testosterone – women normally have near-zero levels of that, so there’s nothing to disrupt by lowering it. If T is involved, it has to be as a symptom rather than cause.

Good point. Seems like it could easily be a symptom: some background pollutant could simultaneously be decreasing testosterone and damaging hypothalamuses (hypothalami?). Or, there could of course be two pollutants.

Endocrine disruptors as a class might still be involved, even if the pathways affected differ between men and women. Women have much less testosterone than men, but it still plays a role in the female endocrine system. While low testosterone is positively correlated with obesity with men, and may have a weaker correlation with overweight in women, female obesity is often associated with a hyperandrogenism in a feedback loop where increased adiposity generates higher androgen levels. Some researchers are investigating the role of sex hormone binding globulins – the bound/unbound hormone fraction may influence adiposity in both sexes. Many common forms of hormonal birth control affect SHBG levels.

Good point.

Xenoestrogens can decrese testosterone in men and they can cause endocrine distruptions in both genders.

Indeed, the age of onset of puberty in females has progressively lowered in the last centuries, and although many confounding factors, such as nutrition, may play a part, some studies have implicated xenoestrogens. (Wikipedia).

I’m interested to know how does fasting come into play in the lipostat model. I haven’t read a lot about fasting, but it seems that some nutritionists and doctors do recommend fasting as a weightloss strategy (i think its called “intermitten fasting”).

Obesity is, as always, a very complicated issue. If “not hyperpalatable” food is one of the keys to combat obesity, how should any government legislate policies to advocate that? Are existing policies futile?

Obesity, of course, brings a lot of health problems, and medical expense (although some dispute whether the extra expenditure is more than the amount their earlierdeaths cut), and “reduce competitiveness”, “lower quality of life”. So should governments “intervene”? If governments do ought to maintain the quality of public health, and even improve it, what can governments do?

I have travelled a few times to the US and still can’t wrap my head about how incredibly tasty is the snack food there. Every time I try an american Dorito is like an explosion of flavour in my mouth and nothing I can buy in an European store can compare. The same happens in different ratios with fast food and pre-packaged food.

So, whats happening?

1) Is a cultural thing? Maybe at some point the American snack companies tried to introduce this kind of thing into Europe and the test groups were like “nah, too tasty”. It sounds like an un-human thing to do. I kind of got weirded out the first time I tried some, but I got used to it really fast, like, by the time I finished the first bag I already loved them (it helps that the American servings are just huge).

2) In Europe is already regulated? Maybe the chemicals that make the American snacks taste so good are banned in Europe, or there is a maximum of salt you can put in a serving, or something.

I’d love to get lost in the internet looking for an answer, but I don’t have the time and a quick google search does not reveal anything but buzzfeed-like anecdata, so if anyone is willing, looking for the European vs American differences in snack food might be a lead.

Good question.

I knew people who worked at the Frito Lay Corporation and they would have appreciated your appreciation of Doritos. A lot of effort is put into flavor engineering American foods.

In general, American foods seems tastier today than when I was young. For example, pizza in Los Angeles is much better than in 1975.

I’ve noticed the same thing with desserts. Europe seems to have a set limit on how good a dessert they are willing to serve.

Maybe they need more growth mindset.

This might be the nost SSC comment ever

Girth Mindset?

The longest I’ve ever been outside the US was a semester in Israel. By the end I had this intense, persistent craving for peanut butter Ritz Bitz. Which is weird because I hadn’t eaten any for at least a year before leaving the States. But I would daydream about them, and I could practically taste the salt.

Also there were no brownies. Mostly there were bland dry cakes.

Not just Europe, either. I’d long heard that the only country to have completely lapped the USA in snack food technology was Japan, and it’s true that if you can find a Japanese grocery you’ll step into a Wonkan cornucopia, an insane profusion of brightly colored foil packages, each with their own kawaii mascot.

But most of the stuff I’ve tried, shrimp puffs to mochi, just seems so… subtle. Nothing like the brisk slap across the face you get from a Spicy Sweet Chili Dorito.

This is my experience as well, but to be fair, if I let myself I could probably eat shrimp chips all day. I find them much more appealing than most American snack foods.

On the other hand, I seem to have a significantly easier time regulating my weight than many people do (I gained significant amounts of fat early in college with a transition to dramatically worse eating habits, but manage to lose it all relatively quickly when I put my mind to it, although it took hard work.) Maybe the facts that I find shrimp chips more appealing than Doritos, and that I generally don’t struggle to maintain a healthy weight, both have a common cause.

When I am eating a bag of doritos they are the best thing ever and I can’t wait to have another one. But I don’t have any cravings for them on a day to day basis. In fact, right now the idea of eating one seems vaguely gross.

That’s not the same thing with say ice cream, which I have a steady desire for that is sometimes resisted and sometimes not. I don’t know why the difference exactly.

This is my experience. Doritos aren’t something I crave. I don’t really crave processed snack foods in general. But if you put them in front of me I will just slam them down.

If I open a bag of barbeque Fritos, I am eating every last one of them, including the dust, including your fingers if they get in my way.

I don’t buy them any more.

I have close to precisely the same experience with the chips they serve at Mexican restaurants – it’s not even that they taste good (I have yet to actually try the salsa they come with), but after starting it’s difficult to stop.

On the other hand, after noticing this I elected not to start eating them on subsequent visits, which has worked pretty well so far. It has yet to generalize to restaurants that serve dinner rolls, though.

There’s exactly one flavor of Doritos I can stand, and the rest taste like snorting concentrated flavor powder through a rolled-up hundred-dollar bill. It’s not pleasant. Maybe whatever makes me feel this way is more common in Europe?

That’s funny. When I travel to the States I generally eat eat healthier than I do at home because I can’t stand how sweet most of the processed food is, (excluding New York bagels), and thus wind up living off salads and raw nuts and the like (and bagels). When I was there for three months I actually dropped a couple of dress sizes.

Also Americans don’t do salt &vinegar crisps. (Or at least I have never found any). You can’t be at the forefront of snack food if you don’t do salt & vinegar crisps.

They don’t? They’re common in Canada.

They do show up sometimes, but my impression of the “standard” flavor options has been “barbecue” and “sour cream and onion” (note: I do not buy potato chips, so take the anecdata for what it’s worth).

Contrast with New Zealand, where “lamb and mint” chips were ubiquitous.

They also don’t have ketchup chips. Or all-dressed chips.

The potato chip gap between Canada and the US is surprisingly large.

Which makes me think that in terms of “explosion[s] of flavour”, Canada is way ahead.

Frankly, ketchup chips should not be legal. They’re like crack but without the barest possibility of health benefits.

I actually saw all-dressed chips in my grocery store for the first time last weekend. I’m not much of a chip-eater, and I try not to be taken in by flavor novelty marketing, so I passed them by, but if some Rand on the internet says they’re good…

Bagged salt and vinegar potato chips are pretty common, at least where I’m from in the States. Delicious combination.

Yeah same here. WalMart has I think literally a dozen flavors of regular Lays, not including the wavy, kettle chip, and ruffled varieties.

Best ones are the Mexican flavors, particularly Chile Limon. Those may not be available nationwide. Salt and Vinegar isn’t the most common, but it’s hardly rare. Without looking it up I’d guess the ranking goes plain->bbq->sour cream and onion->salt and vinegar. Cheddar cheese is probably in there somewhere, and jalepeno is a popular newcomer.

Lays does a flavor contest every year or so, often with some oddities (e.g. chicken and waffles). Out of the last batch, the “reuben” flavor was pretty good I thought. Not much “beefy” but definitely pickled/sauerkraut flavors, caraway, and a bit of swiss cheese.

I thought the biscuits-and-gravy chips Lays was testing a couple years ago were pretty good.

@gbdub

“Lays does a flavor contest every year or so”

I wonder if they turn around the

“Then, almost by accident, someone tried feeding the rats human snack food, and they ballooned up to be as fat as, well, humans.”

– and do a preliminary screening of possible flavors with

rodent weight gain as the assay criterion? 🙂

Why bother paying for rats when you’ve got so many human volunteers?

Salt-and-vinegar was a something you could get in the Midwest 20 years ago and is gradually spreading to the rest of the US.

Salt and vinegar was certainly available on the east coast over 20 years ago. Well, at least Maryland, which may have been considered a good market because of the popularity of vinegar fries. But they’ve been available in Philly and NYC areas for a long time as well.

BTW, salt and vinegar chips might be better called sodium diacetate chips, but no one would buy them if they were. Though perhaps “salt OF vinegar” would work.

I eat salt and vinegar chips all the time. They seem to be a love-it-or-hate-it thing among Americans, but there’s a high enough “love it” fraction that they’re easy to find in stores or e.g. delis.

Might be a regional thing, though. I’ve never seen crab chips on the West Coast or jalapeno on the East, for example. Canadians like ketchup chips, which is just bizarre to me.

Jalapeño chips are fairly common in Philadelphia, or at least south Philadelphia.

I haven’t tried ketchup chips (actually haven’t noticed them for sale), but people put ketchup on french fries, so it doesn’t seem totally unreasonable.

I love them right up till they strip the skin off the entire inside of my mouth.

Philadelphia also has a brand called Herr’s that does the best salt and vinegar chip I’ve ever found: it’s got unbelievably strong flavor, almost to the point of burning as you put it on your tongue (this is more delicious than it sounds)

I had to quit buying them because I couldn’t stop eating them.

Are Miss Vickies common in the US? Their salt and vinegar chips are good.

Ketchup chips are great. I don’t know why they’re an only-Canadian thing.

Based on comments here, my opinion of American snack food has just gone up sharply. So hey, I learnt something today.

Interesting, I don’t like most of American snacks (also not born in US, though living here for a while). The Doritos and other things like that are kind of addictive, and it can be hard to stop eating them if they are laid out in front of you on a table, but I don’t really like them and never buy them for myself.

Same for many other US foods, especially fast foods – they seem too salty, too sweet, too spicy, too… well, many things, for me. Fortunately, the variety of flavors, especially if you are willing to do a little internet searching, is awesome, so it’s possible to find one for virtually every taste.

But I don’t think this kind of preferences is exclusively European, I’ve never lived in Europe (at least Western Europe) for long. Though when I’m there I tend to like the food. But maybe indeed Europeans prefer less “American” foods (no idea how to define that term).

Fasting is one of the (many) things that make me throw my hands up in desperation at reading nutrition advice. The advice I used to hear was that one should eat small meals often, to the point of splitting the three traditional meals into 5-6 smaller ones. Then starting last year I start seeing praise for exactly the opposite approach, fasting for 24+ hours. I guess they can be reconciled if you don’t gorge at the end of each fast, but you see what I’m getting at.

There’s so much conflicting advise that my current course is just “do what you’ve been doing so far and hope it never stops working because you’ll be doomed”.

It might be the case that any change causes people to be more aware of how much they eat and thus makes them overeat less.

“A change is as good as a rest” strikes again.

I don’t think the evidence in favor of fasting falls into that bucket, if I’m recalling it correctly. Mostly because there are a bunch of health benefits that have come up in animal studies, as well as certain biomarkers in shorter-term studies where food intake was fully specified. In neither case the level of mindfulness about one’s food all that relevant.

I wonder if fasting (as in, actually spending a significant amount of time hungry, not just eating less) regulates the lipostat by building a tolerance for low leptin, just as overeating builds a tolerance for high leptin?

I did an “intermittent fast” which basically consisted of 3 days a week of eating nothing for breakfast and lunch, and then a modest (~500 calorie) dinner. Ate normally the other days, not particularly trying to be healthy / restrict calories. I did lose about 20 lbs over 3 months on that program, and it was relatively easy to avoid gaining back after I stopped fasting.

The first couple weeks were the hardest and I had hunger headaches and some fatigue. I adjusted partly just by getting used to it but also by adding a small snack (handful of almonds) at lunch time, and that made it pretty easy.

One thing I noticed was that I became acutely aware of actually being hungry, and realized how infrequently I was hungry otherwise. The small dinner at the end of a fast day was still satisfying, because I was very aware of the satiety signals coming through and the ravenous signals going away.

That I think helped with the sustainment – my body and mind got used to being hungry, and “hungry as the new normal” carried over after the fast period and I noticed fewer (or at least easier to ignore) cravings.

This largely squares with what I’ve been thinking, and believe it or not, McDougal and co. have, actually, kind of invented the “bland food cookbook,” based on their somewhat somewhat similar “pleasure trap” idea (the problem is hyperpalatable/calorically dense food in general). Of course, they don’t call their diet “the bland food diet,” they call it “the Vegan SOS-free diet” (where SOS stands for “sugar, oil, salt,” i.e. all the things that make things delicious).

The big question this leaves for me is: didn’t we know how to cook 100 years ago? I have a lot of pretty old cookbooks. Like early 20th c. cookbooks (admittedly, they tend to be from Louisiana, which may not be a typical food culture), and they are, if anything, even worse, seemingly, than today’s cookbooks. A typical recipe from 100 years ago seems to be something like: “melt one stick butter over medium heat; add fish fillets and fry until brown. Remove fish and set aside. Deglaze pan with brandy and add four egg yolks. Season with salt and pepper to taste and serve with potatoes au gratin and creamed spinach.” It’s not just more fat; it’s just like the type of cookbook you’d expect people to write if everyone was super skinny and had never heard of cholesterol.

My best guess is that this was “special occasion food” and people went back to eating boring stuff the 350 days out of the year that wasn’t Christmas, Thanksgiving, or guests for dinner. And of course the variety was less and the price higher and the convenience lower, etc.

But makes me doubt that hyperpalatable is the only culprit. Cheap, easy availability of a wide variety of foods may be worse. Which confirms my sense that the “food pyramid”-type charts are more harmful than helpful: looking at these things gives you an impression that you need to eat a really wide variety of foods every day or suffer potential malnutrition. Yet these native populations eating only nuts and bear fat do better than us in many cases.

And then there’s everyone quitting smoking…

They may have had fattening recipes and fattening ingredients 100 years ago, but they also had like four spices and six ingredients in the cupboard, as well as no possibility of Mexican tonight, kebabs tomorrow, Chinese the day after, and Italian the day after that.

Personally, if I had to eat only Mexican food this month and only Italian food next month, I’d probably find it harder to gain weight than if I were allowed to freely alternate them. You get tired of a certain set of ingredients, but life today is an endless, multi-ethnic buffet.

Maybe I should write a cookbook, capitaling on the minimalism trend, called the “10 ingredients per month” diet, or something. Since pretty much any weird way of restricting one’s diet works for a little while, I predict it will be a big hit.

I can’t speak to a hundred years ago, but a thousand years ago they had quite a wide variety of spices, and continued to do so for at least the next six centuries, that being roughly the span of my historical cooking. Of course, that describes the situation for the upper class, which is where most of our early cookbooks come from. Were medieval aristocrats typically fat?

They had a pretty wide variety of ingredients too, but more of a seasonal restriction than we have.

AFAIK, yes.

(To be clear, they would be ‘mildly overweight’ by today’s standards.)

I don’t know about medieval aristocrats, but starting from the Renaissance, when realistic painting became popular, aristocrats often look fat. And there are historical records of them suffering health problems (e.g. gout) due to unbalanced diet.

Some Egyptian mummies show signs of diabetes, such as clogged peripherial arteries and amputated toes.

Anyway, at least during the early Middle Ages, where religious dietary restrictions were strictly observed, aristocrats might have fared better.

Why did you reply to yourself?

Also, I think “bland” may be insufficiently precise terminology. as the anecdote about paleo dieters notes, the various diets people embark on can still contain plenty of pretty tasty food like steaks and butter and whatever, but as nice as those foods might be they still won’t compare to the engineered deliciousness of a mcdonalds french fry, or an ice cream sundae, or a dorito or suchlike. Bland doesn’t mean tasteless, it means not ruthlessly optimised for taste. If you think to food that you have cooked, has it ever been inescapably moreish? If I cook a lasagna, it might be delicious but I’m only going to have one piece before putting the rest in the fridge. Not so with snacks you might buy at a supermarket.

I’d imagine that some of the factors you identify, like variety, price, convenience and occasion all played some role in low incidences of obesity as well

I replied to myself because I was unable to edit the original response. It was within the window, but I had switched to another computer.

I am using “bland” here ironically/jokingly to mean “food which hasn’t been optimized for deliciousness.” There are many fresh fruits I enjoy quite a lot, and which possess many interesting flavors, textures, etc. but it’s still hard to compare them, in terms of pure eating pleasure, to say, a chocolate chip cookie. On this definition, the fruit is “bland” and the cookie “optimized for deliciousness,” even if the fruit actually has more complex flavors than the cookie on some objective level.

The food I cook for myself is at least as addictive, to me, as most fast food. But then, I have optimized my recipes for deliciousness as perceived by me.

Still, I’m probably healthier when eating my own cooking, since I am more conscious of what I put in it: restaurants tend to “cheat” by adding more butter, salt, and sugar than I would, in good conscience, usually add to food myself.

Thinking recently about what it means “to optimize for deliciousness,” I was interested to learn that many of the condiment-type items world cultures add to food to give it that extra, savory kick are actually high in glutamate, i.e. natural MSG: parmesan cheese, worcestershire sauce, Thai fish sauce, and, of course, the original source, Japanese seaweed-bonito broth.

Those who worry about MSG claim it is an “excitotoxin”: almost like it “burns out” your taste receptors like loud music. But if that were true we’d expect obesity to be worse in Asia, at least if “burning out your taste buds” had any effect on weight set point.

I would also rate the food I cook as being superior to eat than various snack foods, but my point remains that with the former I simply cannot eat than a standard serving. If I made a chili to a recipe of 6 servings, then chances are I would get 6 servings from it even if I ate it myself over several days. I could not imagine forcing myself to consume the entire thing within one day.

Conversely, I can and have eaten an entire packet of oreos in an afternoon, when they should ostensibly last several days. I don’t even particularly like oreos against any other biscuit or confectionary item, but something about them makes it easy to consume again and again.

Personally, I find it much easier to rapidly consume a large number of home-made cookies as compared to any pre-packaged cookie.

The one exception is those little powdered doughnuts. Those are made of crack or something.

@onyomi: I’m glad I’m not the only one. I can’t buy them anymore, they’re gone within a couple of days.

Snacks are not only optimized for high deliciousness, they are also optimized for low satiating power, so you can eat a ton of them and let the snack companies make big bucks.

Homemade food, when highly delicious, is often also highly satiating.

@vV_Vv

To second your point. It is not about snack foods being particularly delicious, it is a combination of not being very satiating, being pretty tasty, variety of flavors, and I think very important, but kind of glossed over here, ease. I would eat my own cooking over almost any fast food/snack product, but it is dramatically easier to eat fast food/snack products, which is another axis they have been optimizing on.

I spent my early 20’s on a steady diet of junkfood. Mostly sonic double burgers. Naturally, there was weight gain. However, eating the same thing for lunch and dinner day after day meant there was relatively little variety. Why didn’t my brain get brain get used to sonic burger and stopped thinking of them as a trap?

My grandma’s recipes from the mid-20th century did tend to be calorie-dense (plenty of butter, corn syrup, Crisco), but they were also designed to feed six boys on a middle-class salary with mid-20th-century food infrastructure, so they usually used canned or bulk ingredients, didn’t take much individualized preparation, and didn’t use spices or, for much of the year, many fresh fruits or vegetables. They were good in a sticks-to-your-ribs way, but very much not flashy; breakfast Monday through Saturday was plain oatmeal with a pat of butter and a peach or plum in season, for example, with pancakes, sausage and bacon on Sunday.

This doesn’t fit very well with the fat or carbs superstimulus theory, but it fits reasonably well with the flavor superstimulus theory, I think.

Probably because everyone was super skinny and hadn’t ever heard of cholesterol.