[Content warning: this is a complicated analysis of something people care about a lot right now. I’m not confident in my analysis, the post comes to no clear conclusion and there are no easy answers about how to proceed. If I see this on Twitter with some headline about it DESTROYING somebody, I am going to be so mad.]

The New York Times says that It’s Time To Make Your Own Face Mask. But MacIntyre et al (2015) says it isn’t.

The surgical masks used in hospitals are made out of non-woven fabrics that are pretty different from anything you have at home. But in some developing countries, health care workers instead use masks made of normal cloth. Laboratory tests find that improvised cloth masks block 60 – 80% of virus particles. Respirators and real surgical masks block 95%+, but 60-80% still seems better than nothing. And most of the masks ordinary people wear in Asian countries are cloth, and they seem to do pretty well. So there’s some circumstantial evidence that these cloth masks might be helpful. Most experts in the early 2000s agreed that these masks were probably better than nothing. In 2015, an Australian team set out to prove it with a randomized controlled trial.

They went to a hospital in Vietnam and randomized workers there to a normal mask group, a cloth mask group, or a control group. Because it would have been unethical to tell the control group not to wear masks, they left the control group alone. Most control group workers did end up wearing masks sometimes, but less than the experimental groups did.

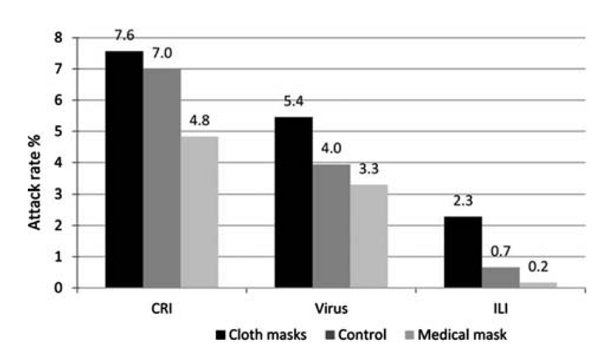

After a month, they counted how many infections each group had, for three different categories of infection. Here are the results:

Technically significant only in the ILI category, but later the authors do various post hoc adjustment for confounders and find it’s significant everywhere

For all three categories, people wearing the real surgical masks were the healthiest, the control group was in the middle, and people wearing the cloth masks were the sickest.

This shows real surgical masks work better than cloth masks. It’s a little bit unclear about how well cloth masks work. They do worse than the control group, but you could tell two stories about that. In one, cloth masks are worse than no mask at all. In the other, cloth masks have zero-to-slight-positive efficacy, but because some people in the control group were wearing real surgical masks some of the time, they did better than the cloth group overall. So it depends a lot what the control group was doing.

Unfortunately, the paper doesn’t give us all the data we want. It tells us that about 57% of both the surgical mask group and the cloth mask group wore masks regularly (defined as more than 70% of the time) but only 24% of the control group did. But there is no way of knowing whether the rest of the control group wore masks 69% of the time or 0% of the time.

A separate paragraph tells us that 37% of the control group used surgical masks, 8% cloth masks, and 53% used a combination of both. These numbers don’t make a lot of sense in the context of the last paragraph, so I’m going to assume they meant that on the infrequent occasions they did wear masks, those were the masks they used. But we don’t know if the compliant workers were disproportionately using cloth masks, disproportionately using medical masks, or both evenly. It’s hard to just eyeball these numbers and get a good sense for whether cloth masks really are worse than nothing.

But the authors themselves lean towards the hypothesis that that cloth masks are actively bad. First, because after some calculations I cannot quite follow, they find that the difference between surgical masks and cloth masks is so high that either the surgical masks are absurdly good, or the difference is being augmented by the cloth masks being actively bad. But nobody has previously found surgical masks to be absurdly good. The authors cite two previous studies of theirs which did include a no-mask control group; surgical masks did not significantly outperform nothing (they did show a trend towards doing so, and the studies were probably underpowered).

Second, because they compare the numbers from this study to numbers from those other two studies directly. They find the rate of infection in surgical mask users is not-significantly-different throughout the three studies, and the rate of infection in surgical mask users and no-mask controls was also not-significantly-different, and therefore surgical masks are the same as nothing and so probably the cloth masks are actively bad.

I am very unimpressed by this. First, you are really not supposed to compare things across multiple different studies. The authors protest that they did all three studies along pretty similar designs, but also admit they were different hospitals during different seasons. But second, almost no differences anywhere are significant, because all of these studies were at least a little underpowered. The current study found no significant difference between cloth masks and surgical masks in two of the three categories, even though the trend was in the expected direction. The other studies found no difference between wearing a medical mask and not wearing a medical mask, even though previous studies have suggested medical masks should work. They couldn’t even find any difference between wearing an N95 respirator and not wearing any protection at all. So when you need a chain of “x is not significantly different from y, which is not significantly different from z” in a bunch of studies that wouldn’t have been able to notice significant differences even if they existed, I stop believing it pretty quickly.

(In fact, I think you could use the same logic to draw the exact opposite conclusion. The cloth mask group in the current study didn’t have a significant difference from the surgical mask group in the other study, and the surgical mask group was no different from placebo, therefore cloth masks cannot have a negative effect. I find it hard to believe the authors missed this, so let me know if I am confused here.)

But MacIntyre et al take it seriously, and conclude:

The study suggests medical masks may be protective, but the magnitude of difference raises the possibility that cloth masks cause an increase in infection risk in HCWs. Further, the filtration of the medical mask used in this trial was poor, making extremely high efficacy of medical masks unlikely, particularly given the predominant pathogen was rhinovirus, which spreads by the airborne route. Given the obligations to HCW occupational health and safety, it is important to consider the potential risk of using cloth masks […] The physical properties of a cloth mask, reuse, the frequency and effectiveness of cleaning, and increased moisture retention, may potentially increase the infection risk for health care workers. The virus may survive on the surface of the face-masks, and modelling studies have quantified the contamination levels of masks. Self-contamination through repeated use and improper doffing is possible. For example, a contaminated cloth mask may transfer pathogen from the mask to the bare hands of the wearer. We also showed that filtration was extremely poor (almost 0%) for the cloth masks. Observations during SARS suggested double-masking and other practices increased the risk of infection because of moisture, liquid diffusion and pathogen retention. These effects may be associated with cloth masks.

Why am I focusing on this one weird study so much? Because it’s the only RCT of cloth face masks we have! Millions of people, egged on by top newspapers, are about to start wearing cloth face masks during a pandemic, when right now the authors of the only randomized trial on them conclude they’re probably net harmful. This should be really scary! Somebody with more experience and statistical knowledge than I have should be looking this over with a fine-toothed comb and trying to figure out what we should do.

Until then, should people stay away from cloth masks? I’m not sure, and this is so not a recommendation, but I lean toward no. The prior that they should work or at least be neutral is too high for a study this weak to convince me otherwise. More important, this study only examines incoming pathogens. Even if they are harmful for blocking incoming pathogens, there are still reasons to think they are helpful for blocking outgoing ones. If I had to hang out with a coronavirus patient for a while, and I had to choose between both of us wearing cloth masks, or neither, I would go with the masks. Only until we could get real surgical masks, which are much better. But I’d go with the cloth ones instead of nothing.

But right now that’s a gut judgment, and the evidence says I’m wrong. This is one of those times where people have to make a life-or-death decision in conditions of high uncertainty, and it really sucks.

[EDIT: Bolded a passage I think is important to make sure people don’t miss it]

This is exactly right. The main value of face masks is not to protect the wearer from others, but to protect others from the wearer. MacIntyre does not address this. Manjoo does, but barely.

The reason everyone should be wearing face masks is because anyone might be infected.

Why is Scott leaning no if this is true? I’m so not getting this.

It’s a double negative. Should people avoid cloth masks? He leans towards no. So he’s saying he leans towards yes, you should wear a cloth mask.

Thanks. I’ve been reading everything way too fast recently and this blew right by me.

100% agree Ashley. And, does anybody see this as a systematic error here in the West? I keep reading variations on the argument, “masks aren’t very protective, and they are in short supply, so you (jane public) shouldn’t wear them.” Ignore the paradox for a sec and focus on the implied cost-benefit equation for widespread public mask use. Benifit: masks could protect wearer – but not very well. LOW. Cost / Manufactured masks are supply-limited. HIGH. Conclusion: NO to widespread public mask use – only the most vulnerable should wear masks.

But … but … Benefit: masks, even homemade ones, may protect others from an infected (possibly asymptomatically) infected wearer. UNKNOWN – where are the studies? Cost: homemade masks have some cost in time and effort, but … LOW. Cost: Masks look weird. This one depends on your temperament and herd instinct but be honest we all have some, and I’m gonna say in the current climate for most of us the social cost of mask-wearing is on the HIGH side. I wore one at Costco recently and got lots of baleful glances (saw one other mask in the store).

That last cost shouldn’t be in there! It is caused by excessive repetition of that irrational mantra “masks aren’t very protective, and they are in short supply, so you shouldn’t wear them.” I find this frustrating.

I also find it interesting that the benefit, ” protecting others” seems to have been prominent from the outset in the analysis by mask-wearing countries, whereas it is coming more slowly here (I’m betting the tide will turn). Could this reflect a cultural value system that skews more towards consideration for others over self? If true, could such an other-oriented value system predict other behaviours that are unfriendly to the spread of disease as well? Dunno, but wonder.

I think some of it is the (rational) focus of prior research on health care workers, where you’re mostly looking to protect the healthy workers from contracting their patients’ illnesses. In that setting it makes a lot more sense to look at rates the nurses/doctors contract illnesses because the other direction is less likely & harder to study.

The one exception I know of is that healthcare staff who are working and either mildly sick (eg. minor cold) or aren’t vaccinated for the flu (for whatever reason) will wear masks in the clinical setting to reduce risks to the patients. But that’s pretty minimal overall.

Ya, good point that the research focus on self-protection up to this point was rational. I will recant my carping about insufficient study of the other direction! I used word “irrational” not for that, but for what I see as the application (whether consciously or not), by governments and public health leaders, of an inappropriate cost function for the decision about whether to recommend widespread use of homemade masks (and commercial when available), in the current pandemic setting. To me that description still seems accurate. If the cost function is changed for one that better fits the desired outcome (eg curve-flattening), and the decision stays the same – so be it – I will no longer use that word!

Exactly. I get the feeling the east understands this instinctively, and for we in the west, it’s secondary.

(Keep your germs to yourself, everyone.)

Does anything in these studies address the idea that wearing a cloth mask leads to people taking higher risks? (I.E. if you wore a cloth mask and acted like you weren’t wearing a mask then it would be at least a small improvement(plus limiting other exposure to your coughing and sneezing) but if you wore a cloth mask and acted like you were wearing an N95 respirator then your behavior is increasing your risk of infection more than the mask is decreasing your risk of infection)

That’s the WAG that i heard(can’t remember where tbh) that seemed plausible.

If there really is a negative effect to cloth masks this seems like a likely cause of it. It also goes both ways, perhaps patients are worse at turning their head before coughing if they think the doctor is protected.

Any sort of risk compensation effect would be absolutely terrible to quantify because it would behave differently across cultures & time; maybe masks work in East Asia because people are used to them but wouldn’t work in the US or Europe because we’d hear n95, think that meant 95% invincible, and stop all other precautions.

This creates a catch-22 where masks only work for people that don’t believe in them, but nobody wears a mask they think doesn’t work.

Is there any evidence that this happens when people wear masks? One could just as easily tell a story where having the mask on reminds people that they’re in a heightened-risk environment, and they behave more cautiously.

There’s also a question of whether *anything* we’ve previously learned about compliance, risk compensation, and other behaviors surrounding mask use – to control influenza – applies in a situation where controlling respiratory infection is the most talked-about topic in the world, 24 hours a day.

I’m skeptical that the hospital personnel in the study would take more risks – they probably don’t have much opportunity to do so given the nature of their workplace.

But I agree that this effect is very relevant to the public policy question of whether to recommend widespread mask-wearing. On the margin, ceteris paribus, I speculatively think there’s good reason to think that people would tend to reopen more workplaces / schools, reduce social distancing, and practice worse hygiene. I’d expect this effect to be larger if public health authorities publicly state that masks are effective.

But also, if you look at the study, the healthcare workers assigned to cloth masks were given 1 to wear the entire 8 hr shift. They were taken off to go to the bathroom, (and I’m sure to eat and/or drink) which would have to mean they were taking them off and putting them back on several times a shift. Where were they placed? Was there contamination from the mask to the mucous membranes with repeated touching?

The group with the hospital masks received 2 per 8 hr shift. So even with the same variables above, there was a point in the day where they received a clean mask.

Masks definitely don’t put me in a risk-taking mood. Wearing a mask, and seeing other people wearing masks, is a constant reminder that things are very much not normal and I shouldn’t be doing normal things.

Risk compensation is a subconcious thing. As long as the mask is a novelty, there should be no negative. When/if it becomes part of your daily life, that’s when you get complacent.

I think an important difference between cloth and surgical masks is that the cloth masks are re-wearable and surgical masks are disposable. They probably need to be laundered periodically, or else your just put a germ-soaked cloth on your face. Also, the difference in population between the people with access to real surgical masks and those with access to cloth ones might also be an over-riding factor that erases all else.

The describtion I heared (in German Telivision by a usually reputable Health Show) was, the mask has to be thrown in boiling water for at least a couple of minutes after every use. And not to be worn for extended periods of time (<20mins). Also you need to be very careful when removing them.

So you need at least two masks, or more when you have to switch them regularly over an workday. Maybe you can replace boiling water with half a minute in an microwave, and thus remove the need to dry the mask. Still you would need a couple.

Any one up to an educated guess, how many over worked health care workers did that? And how much of the general public can be expected to do it right?

If you’re boiling the mask at home, consider boiling it in a sealed zip-loc bag so that it does not get wet. Just make sure to leave the pot boiling for a long time (air is a good insulator, so the mask will take a while to reach a hot enough temperature). This way you don’t have to dry it all the time.

I would guess the microwave is a bad idea, because microwaves heat extremely unevenly – they form hot spots that the rotating plate travels through. This is not a concern when heating something which conducts heat well, like a glass of water, but it’s a big concern for a heat insulator such as a cloth mask.

Using a zip-bag is an good idea. I will remember that.

A zip-lock bag will melt in boiling water.

So I suppose you could use a sous vide circulator too. If you can pasteurize eggs in a sous vide, you should be able to sterilize cloth.

I think heating the mask to 70C (about 160 F) for 30 minutes while keeping it dry inactivates the virus and doesn’t damage the filter medium.

I’mma see if i can use this to convince my wife that we need a sous vide. 🙂

I read somewhere that microwaving disposable N95 masks melted some of the fibers in the mask and likely changed the filtration for the worse.

Also, you can’t microwave an N95 mask intact. You would have to remove the metal nosepiece that keeps it airtight around the bridge of you nose. That seems like a set up for an ineffective mask.

If you’re talking about the need to reuse and clean an N95 mask the best option would be to soak it in hydrogen peroxide 6% for 30minutes

Maybe microwaving with a bowel of water to steam it?

I would use the oven before using a microwave. Microwaves do not work properly on dry goods.

Microwaves have proven to be surprisingly effective in killing of microbes in wiping clothes in the past.

You do not want to make the mask hot but kill the microbes inside of it. And the microwaves are able to do that without heating up the mask just fine.

Do you have a source for this? Having just finished a cloth mask the other night, I’m curious.

Is this true for viruses or just microbes?

Microbes contain water, while viruses probably don’t, which could mean they are less affected.

Trying to find a source I found several sources claiming it does kille bacteria, but will probably not deactivate viruses.

So if in doubt, rather put the mask in boiling water.

https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/0307945042000205874

I am a programmer, so I can’t evaluate the quality of this paper, but it was the only one I found on the topic of microwaving coronavirus.

It’s old paper, so it’s not about ncov2, but about Avian Infectious Bronchitis, also from coronavirus family.

And they say, that 5 seconds in kitchen microwave was enough to harm virus enough that they could not identify it in the sample using their method.

I don’t know if this implies that the virus got neutralized.

As for proposed mechanism, I’ve read somewhere, but without citing original research, that viruses have hydroxyl groups which get twisted by microwaves in similar ways to water molecules, which perhaps “heats” them or teard them apart?

I’d like someone to educate me on this topic, as I believe many people have microwaves and if they would be useful for desinfection that would be great.

Someone started a fire by putting a mask in the microwave dry. In order to sterilize in the microwave the mask needs to be wet and it needs to be microwaved for at least 3 minutes based on studies of other viruses.

Someone asked for a source regarding microwaves and killing of viruses

https://smartairfilters.com/en/blog/microwaving-masks-disinfect-covid-virus/

I’ve been hitting our masks with the steam iron, both sides, lots of steam, press hard. Then they are instantly ready to go again.

If you plan to launder it, I recommend you use bleach.

At a primary research conference years ago I attended a lecture by an epidemiologist and he said when they tested clothes they found something like 99% of the pathogens were eliminated, but the last 1% distributed evenly across everything in the load. Since they found on average a few grams of fecal material on underwear, his recommendation was to launder it separately and use bleach. I imagine a similar principle applies here.

That seems reasonable, but isn’t COVID-19 particularly susceptible to soap because of its envelope? (By contrast, you probably have to nuke the laundry from orbit to kill off the last of the bacterial spores in it.)

If you’re talking about the homemade cloth masks, You are correct. The outer layer of the virus is made up of lipids. Soap dissolves the lipid coating of coronavirus, physically inactivating it making it unable to bind to and enter human cells. The best way to clean the masks is in the washing maching and dry on high heat.

I’ve seen microwaves mentioned, using a study of kitchen sponges as an example, they have to be microwaved for at LEAST 2 minutes to kill the bacteria and viruses. So if you’re going to microwave a homemade cloth mask, you have to make sure it’s wet and microwave it for at least 3 minutes for coronavirus like virus (it hasn’t been tested on covid-19)

Boiling water can actually degrade the cloth in the masks increasing their permeability and will definitely break down any elastic you are using to secure the mask.

A few grams?! Wouldn’t such a quantity be plainly visible to the eye? In any case, what an argument for the bidet…

Someone started a fire by putting a mask in the microwave dry. In order to sterilize in the microwave the mask needs to be wet and it needs to be microwaved for at least 3 minutes based on studies of other viruses.

In the study they were given instructions to wash the masks with soap and water at the end of every shift.

Well, what about this:

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/258525804_Testing_the_Efficacy_of_Homemade_Masks_Would_They_Protect_in_an_Influenza_Pandemic

Not sure what units they’re using, but it seems vacuum cleaner bags are second to surgical masks in terms of efficacy of keeping things out.But keeping B atrophaeus and Bacteriophage MS2 don’t appear to spread in the same manner as the coronavirus, though that is a low confidence claim.

Anyone more knowledgable like to weigh in?

That study is measuring outflow from the wearer. i.e. it is about how much wearing a mask protects other people, not how much wearing a mask protects you from other people. “The median-fit factor of the homemade masks was one-half that of the surgical masks. Both masks significantly reduced the number of microorganisms expelled by volunteers, although the surgical mask was 3 times more effective in blocking transmission than the homemade mask.”

Theres also this: Simple Respiratory Protection—Evaluation of the Filtration Performance of Cloth Masks and Common Fabric Materials Against 20–1000 nm Size Particles

The fast.ai folks are tracking lots of designs that are upgrades over cloth masks and just as easy to make. The simplest is 2 layers of cloth cut from a 100% cotton tshirt, with a disposable paper towel in the middle. Throw away the towel then wash the mask after use.

Relevant links and discussion: https://forums.fast.ai/t/masks-for-covid-19/66057

I think there are a number of major issues here:

1) This study’s control group isn’t actually a control group. If people are wearing more intense PPE in the most important situations, then you may well find no difference between the mask group and the control group because most of the time, masks don’t do anything, but in high risk situations, they’re actually useful. Thus, the difference between someone who wears a mask only in high risk situations and who always wears a mask may well not be statistically significant.

2) Most doctors don’t use their masks correctly. I know the proper procedure for putting on a face mask and taking off a face mask. I’ve seen doctors and dentists use facemasks. I would say that about 80-90% of the time, they do it wrong.

Just to be clear, here are the “correct instructions” for wearing a facemask, taken from the San Francisco public health division website:

Step 1. Clean your hands with soap and water or hand sanitizer before touching the mask.

Step 2. Remove a mask from the box and make sure there are no obvious tears or holes in either side of the mask.

Step 3. Determine which side of the mask is the top. The side of the mask that has a stiff bendable edge is the top and is meant to mold to the shape of your nose.

Step 4. Determine which side of the mask is the front. The colored side of the mask is usually the front and should face away from you, while the white side touches your face.

Step 5. Follow the instructions below for the type of mask you are using.

Face Mask with Ear loops: Hold the mask by the ear loops. Place a loop around each ear.

Face Mask with Ties: Bring the mask to your nose level and place the ties over the crown of your head and secure with a bow.

Face Mask with Bands: Hold the mask in your hand with the nosepiece or top of the mask at fingertips, allowing the headbands to hang freely below hands. Bring the mask to your nose level and pull the top strap over your head so that it rests over the crown of your head. Pull the bottom strap over your head so that it rests at the nape of your neck.

Step 6. Mold or pinch the stiff edge to the shape of your nose.

Step 7. If using a face mask with ties: Then take the bottom ties, one in each hand, and secure with a bow at the nape of your neck.

Step 8. Pull the bottom of the mask over your mouth and chin.

Here’s what I actually observe:

Step 1: Grab a mask and put it on, often handling both sides of the mask.

Step 2: If it is a mask with ties, tie it up and go.

Quite often, they fail to wash their hands. Sometimes, they mishandle the mask. Frequently, they don’t really adjust the mask properly, just kind of slap it on there and get going. Sometimes they’ll put on gloves before doing it (which is sort of like hand washing)… but sometimes they put on the gloves after doing it. And sometimes they use potentially dirty gloves to put on the face mask, because they start off doing stuff, and then do something that they’re like “Oh, I should put on a mask for this.”

The steps for taking it off, incidentally:

Step 1. Clean your hands with soap and water or hand sanitizer before touching the mask.Avoid touching the front of the mask. The front of the mask is contaminated. Only touch the ear loops/ties/band.

Step 2. Follow the instructions below for the type of mask you are using.

Face Mask with Ear loops: Hold both of the ear loops and gently lift and remove the mask.

Face Mask with Ties: Untie the bottom bow first then untie the top bow and pull the mask away from you as the ties are loosened.

Face Mask with Bands: Lift the bottom strap over your head first then pull the top strap over your head.

Step 3. Throw the mask in the trash. Clean your hands with soap and water or hand sanitizer.

I sometimes see them wash their hands either before taking off the mask, or after taking off the mask, but I’ve never once seen someone do it both times. And a lot of the time, they don’t do it at all, at least not within my line of sight (maybe some of them go wash their hands afterwards?).

3) I have the suspicion that you should wash your face before putting on a mask, and wash it again after you put on a mask, instructions which aren’t in these checklists for some reason. The thing is, if you put on a mask, and you already got some germs on your face, you’ve trapped them against your face. Likewise, if your face apart from the mask has been contaminated, and you take off your mask, you’re pretty likely to rub your face afterwards and spread the germs from the dirty areas, at which point, well, you’ve just kind of defeated the purpose of wearing the mask. And it’s a natural human reaction to rub your face afterwards.

4) Sometimes I see people pull masks off to rub their face underneath and then put the mask back on, because they aren’t thinking about it, or pull the mask down for a bit then pull it back up.

5) I really suspect that people should probably just be wearing masks all the time in medical settings so as to minimize exposure as well as minimize the number of times taking off and putting on masks, but people don’t do that because it sucks to wear a mask all the time.

My guess is that if you wash your hands and face, put on a mask at home, go out, do stuff, and then when you get home, wash your hands, take off the face mask, and wash your face and hands again, you’ll probably see much better results than actual doctors do from their masks.

It might depend upon your goal. Until recently, the only time I’d wear a mask on the ambulance was if I thought I was sick with a cold and going somewhere with vulnerable populations, like a nursing home. In that case I’d take a mask out of my “clean disposables pocket”, put it on and wear it until I dropped the patient off at the hospital. Then I’d take it off, throw it in the trash and wash my hands. But I wasn’t worried about getting sick myself. And anything contaminated (in this case, on the inside), I already had it.

Just wondering – has anybody considered that if masks (or not-great masks ) only have a marginal benefit, could this be (greatly?) outweighed by the confidence-inspired extra risky behavior it generates? Yes, there’s a name for this, which presently escapes me, but in other contexts it’s afaik quite widely studied.

ETA just noticed this was partially addressed up thread. I must have skimmed right over the top of it – my bad.

I believe the word you’re looking for is “risk compensation”. A related idea is “moral hazard”.

“Risk compensation” is the phrase I’ve most often heard, and various forms of it are easy to demonstrate (ranging from things like imagining driving without wearing a seatbelt and think about how much more careful you would be, to studies showing that people in automobiles pass much closer to cyclists that are wearing helmets than to cyclists that are not).

+1

Risk compensation is a real potential issue here–if you wouldn’t have ridden the subway without your homemade mask, but will with it because it makes you feel safer, it’s quite likely that the mask is making you worse off.

There’s an analogy to firearms here–if carrying a gun makes you more willing to get into dangerous confrontations, you should have left the damned thing at home.

The headline picture for the Wikipedia article for Risk Compensation shows people skydiving in boats, which is such an amazingly good summary that I bet some editors try really hard every day to remove it.

I think the important point here is that the CDC is saying the mask is in ADDITION TO social distancing (6 feet). That they are working in combination, not one or the other.

I think this study is not answering the right question for Coronavirus. This looks at whether wearing a mask stops you getting sick. But for Coronavirus, the important question is whether wearing a mask stops you getting others sick.

The evidence from various sources is that even cloth masks stop the passage of some viral particles. You could argue that this is immaterial because sick people should be staying home, but that still ignores the very long asymptomatic period of coronavirus (median 6 days to symotoms) and the likelihood of many fully asymptomatic infections: in Iceland, 50% of positive tests were in people with no symptoms; there was a similar percentage (60?) in the village in Italy that tested the whole population. Wuhan estimated that over 70% of new symptomatic infections were from an unknown source and China is now actively seeking to quarantine asymptomatic infected people.

All that suggests that:

– many infected people never show symptoms, or have a long period of feeling fine but shedding virus

– many new infections come from asymptomatic people.

That implies that there is a public health benefit to everyone (not just sick people, who are hopefully quarantined) wearing masks, washing hands frequently and being extremely careful about what they touch when out and about: because in the absence of widespread testing it is better to take precautions as if you are infectious.

Now, it could be that the “asymptomatic infections” are actually false positives. I’m not sure that’s likely. I’d believe it for Iceland, where they were randomly sampling a population with a low base rate of infection. However:

– new infections in Vo stopped when asymptomatic people were quarantined

– countries that have aggressively contact-traced and quarantined have had much better success at controlling the infection spread

That suggests that there is indeed considerable asymptomatic transmission and that any precautions that we can take to reduce spread from people who feel well (and may never know they are infected) are valuable. That would include staying home as much as possible and wearing a mask (cloth to save the better ones for healthcare workers) when out and about.

Anecdotally, my flat-mate has been ill for the past week with what looks extremely likely to be coronavirus (bad cough, loss of all sense of smell/taste, low fever, poor O2 saturation on one day, chest pain). We are 4 adults living in a 570 sq ft apartment with 1 bathroom (this is quite normal in London), we have been quarantined like this for 8 days now and all three if the rest of us feel 100% fine. I’d say if the R0 of Coronavirus is indeed 2.5 that it’s highly unlikely that we are not infected (and infectious), and yet we are not unwell at all. If we didn’t know that we are highly likely to be exposed, we would have no way of knowing. It really brings home the importance of both testing and social distancing (including mask wearing) to stop the infection spread.

Note that the 50% thing was people who had no symptoms at the time they were tested; the media, being incompetent, suggested that 50% of infections are asymptomatic.

Given that the median onset time for symptoms is close to a week and that you are typically sick for 1-2 weeks after that, the 50% asymptomatic thing could well indicate a 0% rate of asymptomatic carriers in the long run, as the half of detected cases were just people who had been infected, but had not yet shown symptoms, as there are far more people infected when the cases are ramping up than there are people who are showing symptoms.

That said, I believe that shouldn’t change recommendations on a societal or individual level. Whether you believe you may be infected and asymptomatic, or you believe you may be infected and not-yet-symptomatic – in either case, the recommendation should be to wear a mask.

Agreed. And I just read a study today that said that a person with coronavirus is actually MORE contagious (their secretions have a higher viral load) than when they become symptomatic.

Also, why the low efficacy for surgical masks? Whatever happened to the much-vaunted promise of nanotech even a few short decades ago? Why don’t we have super-high efficacy, nano-printer fabricated, face-hugging masks at this point? Why do even surgical masks seem to be stalled at an earlier stage of evolution?

Cost and convenience.

If you want something new to be adopted it needs to be the same cost (or cheaper) and as convenient. Alternatively, it needs to show a noticeable improvement in some key metric that hospitals care about, like post-op infections or something. Otherwise it won’t happen.

Nanotech was always a buzzword with very little relationship with reality.

What people claimed nanotech would do and what nanotech actually is are wildly different things.

As for the surgical mask question – we do have things that work great. They’re called respirators.

The problem is that for something to “hug your face”, it must be shaped so that it fits on your face, or have some sort of seal on it (probably made out of rubber) that can mold to your face. Or both.

As someone who has worn a full-face respirator for work, I can assure you, they do work. But they also get warm when you’re wearing them and aren’t particularly comfortable to wear for long periods of time as, again, they’re pressed in tight against your face to form a seal and the fact that they are so good at sealing stuff in means that they’re good at sealing stuff in, including your own radiated body heat.

I’ve seen these sorts of buzzwords come and go in fields closer to my own, so I’m curious if you could expound upon the story behind this one.

All nanotech actually means is “nano-scale technology”, which is to say, technology which is on the scale of less than a micron.

It is no single thing.

What people were imagining were tiny microbe-sized robots. But there are all sorts of physical issues with mechanical devices that small.

What we actually see are mostly processes that involve things that are less than a micron in size.

For example, ICs are probably the most well-known and widely used nanotechnology. We just made them smaller and smaller, and now we create die features with a size of less than 1 micron (in fact, now we’re down to some die features that are only a single nanometer thick – this is about the thickness of ten atoms, so these are really small!).

We’re using atomic force microscopes and very fine ion beams to deposit or remove tiny amounts of material from stuff for various purposes.

There are various chemical deposition processes which are designed to put extremely thin layers of some compound on something else, creating a thin coating to alter its properties. This is “nanotechnology”.

Genetic engineering is nanotechnology, as we’re deliberately altering DNA strands on a molecular level.

But even things like colloids can be classified as “nanotechnology” when we create solutions of suspended particles that are less than a micron in diameter.

What people think of when they think of nanotechnology are like, tiny little robots or whatever, but the reality is that there’s nothing particularly unified about nanotechnology as a “thing” beyond it simply creating or manipulating things on a certain size scale.

Thanks. That’s helpful, particularly with where nano-scale stuff has been useful. I still want to push for a bit more, though.

I do significantly larger robotics, and haven’t really kept up in the realm of the super small stuff. My guess would be that the primary concern here is power? Are there more significant issues? A couple other issues that are approximately the same level of difficulty?

Power is one big issue here. Another is that nothing is really rigid on the molecular scale, so you’re trying to build robots out of rubber. Sticky, unvulcanized rubber.

Also, nanoscale robots that you have to build by brute force with big expensive hardware like chip fabs are of limited utility, so a big part of the promise was that nano-robots would build more nano-robots in an exponential-growth regime. And we still haven’t figured out how to build robots that can replicate themselves entirely from scratch when we’re building them from steel and plastic and silicon and plugging them into 480 VAC; it’s not going to get easier when we have to make them from sticky rubber and power them with a glucose solution or whatever.

Roughly speaking, the near-term plausibility of “nanotech” is inversely proportional to the degree in which you have to think of the nano-thingies as “robots”.

That makes sense. Thanks!

We know that Drexlerian nanotech aka molecular nanotech aka tiny machines is possible, because that’s how living creatures are engineered. We don’t know whether, or how soon, we can do it.

The idea goes back to a talk by Feynman and was publicized by Eric Drexler in Engines of Creation.

For a shorter account, see Chapter 18 of my Future Imperfect.

Because surgical masks aren’t made for contagion or isolation from known infectious diseases…they’re SURGICAL masks that are worn in the OR to protect the patient. The intention of the surgical mask has never been to protect the wearer. (Another time they are used by a healthcare provider might be when seeing an immunocompromised patient. The protection again is for the patient, not the wearer of the mask.)

Another argument I’ve seen for wearing masks (or any face covering) is that it reduces your incoming and/or outgoing viral load. Even if small viruses can get through, large droplets are contained. Viral load arguments say that the smaller your initial dose, the better chance your body has to fight off the virus. High initial #’s of virus give the virus a big head start. This is backed up by variolation in earlier viruses (e.g. smallpox in UK) and anecdotal evidence for coronavirus that, in Wuhan, first members of a household were likelier to have a milder case (brief exposure to stranger) compared to other household members (in frequent contact with their exposed family member).

Dose dependent infection severity is apparently standard virology.

It’s also the explanation for the extremely high rate of fatal infections in medical staff – they’re much more likely to get a huge dose or multiple doses of the virus.

New Scientist article on the subject

> …surgical masks did not significantly outperform nothing (they did show a trend towards doing so…

Finally, someone statistically literate used this phrase, so I can ask:

What does this mean in the context of a single study?

If you’re considering a few studies, each of higher power than the last, and each getting closer to p<.05, I can easily understand that as "trending toward significance." But what does it mean for a single study to be trending toward significance?

Technically? Nothing. It’s a nonsense phrase. I’ve never seen a formal definition for “trending towards significance”. Colloquially, I understand it to mean “the p-value is kinda close to the chosen level of the test, and the sign of the parameter estimate is correct, so can I have partial credit on my Science, pretty please?”

Here’s my attempt at giving the phrase a coherent meaning, though I think this is all nonsense:

Suppose you have some ordinal explanatory variable, and notionally, if you used a more extreme intervention than the most extreme one in the study, it may have produced a significant effect. You draw a trend line (or curve or w/e) using the actual interventions from your study (after placing them on some imaginary number line if the explanatory variable is ordinal rather than continuous), then extrapolate that line out to where you’d place the more extreme intervention that you didn’t include in the study. You can now estimate a hypothetical effect size and do a t-test or whatever.

But there’s a bunch of problems with this. First off, if your explainer is strictly ordinal and not continuous, interpolating a linear effect between the ordinal levels doesn’t always make sense. The most generous interpretation of the interventions in the study Scott cites is that they’re ordinal, with “nothing” being less intervention than “cloth mask”, which is less than “surgical mask”, but given the vagaries of the control group discussed elsewhere on this thread, that may not be a sensible interpretation. Either way, definitely not continuous, so you’re already making shit up if you place them on number line and draw a best fit line. This means you have to postulate some “distance” between each level, including the new level for which you don’t have any data. Then, you have to extrapolate your trend on your made-up number line beyond the point where you have data. Then, you can measure an effect and say, “Well, maybe if we’d tested that level and the trend continued, and we got the same error estimates and a million other things, then the results of our study would’ve been statistically significant!!

But all of that above is just a fancy way of saying, “We didn’t choose the right factor levels for our study, and we didn’t collect enough data.”

What are CRI and ILI?

The linked report defines these terms as:

(1) Clinical respiratory illness (CRI), defined as two or more respiratory symptoms or one respiratory symptom and a systemic symptom

(2) influenza-like illness (ILI), defined as fever ≥38°C plus one respiratory symptom

The other endpoint used in the report is:

(3) laboratory-confirmed viral respiratory infection

I saw this design on twitter, which seems simple enough to make. And while the main benefit of masks seems to be not spreading the disease yourself, I’d like to make something that has a good chance of lowering my odds of getting infected as well.

https://twitter.com/evolutionarypsy/status/1244608593715965952

Would the filter she’s using actually be useful? If so, is there a minimum rating level I should look for?

Do cloth masks block outgoing pathogens even if I am asymptomatic?

The model I know for blocking outgoing pathogens is that, when I sneeze or cough, it slows down and/or catches the droplets near me.

But I’m not sneezing or coughing. As far as I know, I am not sick with the flu or coronavirus. If I were, I would not go outside for any reason.

Does the model also work for asymptomatic people who happen to be shedding the virus?

You also produce respiratory droplets when breathing or talking, although in smaller quantities than a cough or sneeze.

I’ve been paying a lot more attention to my potential respiratory symptoms the past few weeks. There are still occasions where I cough or sneeze, because a very mild level of allergy has been triggered, or because I inhale a bit of dust or swallow awkwardly. There have been some days where I cough five times and sneeze twice, and other days where I cough zero times and sneeze zero times (and no days with sustained coughing or sneezing throughout the day since I got over my last cold in the first week of March). Presumably an asymptomatic carrier would also sometimes have those days where coughs and sneezes happen for unrelated reasons.

Think droplets. Every time you talk, you spread little droplets of saliva/virus in front of you. They land on surfaces and nearby people and maybe in your buddy’s Diet Coke. Sometimes, you cough or sneeze and spread way more droplets in a much bigger cloud. Sometimes you yell or sing, and that probably spreads more droplets further. A mask in front of your mouth and nose will catch some/most of those droplets, which means they don’t land in your buddy’s Diet Coke or on his lips or on something he’s going to touch.

This is also why, if you cough or sneeze into your hand, or rub your eyes, you should use hand sanitizer immediately. This does nothing to protect you, but it may protect everyone around you.

Interesting study. A few (naive) thoughts reading through it:

1) It’s worth looking at absolute numbers to get a better sense of the size of effects. The study had about 500 people in each each arm, so a 1-2% differences in “attack rates” between arms means 5-10 more people becoming infected. A 5% attack rate (as observed for virus with cloth masks) means 25 people becoming infected. 1 person getting sick (likely random fluctuation) is thus about .2%. This implies that the observed differences are indeed large enough to be unlikely to be random, but are small enough that they might be swamped by even minor systematic effects.

2) The study is measuring “intent to treat” (that is, recommending a particular type of mask) but the answer most people here are interested in is whether particular types of masks actually work better when used correctly. The compliance numbers are low enough that any measurement error here could confound everything else. For both the medical and cloth mask arms, just over half the participants wore masks more than 70% of the time. Were the noncompliant users identical in both arms? If not, this could might explain all the differences observed.

3) Rather than comparing total outcomes with limited compliance, if our interest is which approach works best if actually followed, it would be helpful to know what the results are when restricted to extremely high levels of compliance. Presumably, some subset of the users in both arms used the masks (almost) all the time. How did they compare? If one is trying to make a personal decision about mask usage based on effectiveness, this would be very useful information, but doesn’t seem to be given in the report.

4) One of the biggest oddities in the study is the difference in Handwashing between the different arms of the study as shown in Table 1. The Medical mask arm had 2-3 more hand washings per day (14 total) than the Cloth (11) or Control (12). This seems almost impossible to occur by random chance, implying that there must be something systematic happening here. Since we know handwashing is effective, just this effect might be enough to explain the entirety of the results. Is there any explanation for such a large difference here that doesn’t call into question all the rest of the conclusions?

5) Lastly, and as many others have pointed out, in an epidemic setting we care a lot about whether masks help to prevent the spread of disease from the wearer to others. It’s not a fault, but this study doesn’t really answer that. It does however probably put a limit on how large the increased risk of wearing a cloth mask can be for the wearer. I think this implies that if masks are effective at all at preventing an infected wearer from spreading the disease, the use of some form of mask probably should be recommended.

Proper procedure for donning a mask is to wash your hands before putting it on, and wash your hands before you take it off, and wash your hands after you take it off. That may well be why they washed their hands more.

Good point! I presume that in theory the “proper procedure” would be the same for cloth masks, though. While it would be interesting if the difference in effect was that the medical mask users followed proper procedure for handwashing and the cloth mask users did not, I wouldn’t take this to mean that cloth masks are inherently less effective.

If you go outside just once or twice a week to get groceries, does this negate all the self-reinfection issues? Even without any sterilization the virus doesn’t survive on surfaces for over 3 days IIRC, and you have plenty of time to wash and dry the mask or whatever.

One study I read said active virus was detected on the outside of (I think) an N95 mask after 7 days. OTOH, I have an N95 mask I used for shopping a little more than a week ago, and it’s in a ziploc bag in my car until the next time I need it. (I left the bag open for a few days to dry out, then sealed it.) I’m hoping the virus degrades over time, since I don’t have enough N95 masks to use a new one every time I go shopping. (Nor would I feel great about going through a couple dozen N95 masks during a time when doctors and nurses treating infected patients are doing without.)

Apparently ~99.8 of the trapped particles remain trapped in an N95 mask.

Source: Recommended Guidance for Extended Use and Limited Reuse of N95 Filtering Facepiece Respirators in Healthcare Settings

The relevant subsection is paragraph II under heading Risks of Extended Use and Reuse of Respirators

I think the most important question that needs to get answered concerning masks for the populace at large is not this business about the efficacy of masks (whether surgical or cloth) for a random individual (whether wearer or bystander), but rather: Consider a group of persons in a confined environment, the group having x% of infected individuals at some fixed time and (100-x)% of noninfected individuals. Consider two strategies: 1. The group wears masks; 2. The group does not wear masks. Question: what is the difference in expected transmission rates for these two strategies?

I would expect an interaction between physical distancing and mask wearing.

Physical distancing probably has a disappointing effect. Two meters is about the upper limit of what is practical, while simultaneously about the lower limit of what is effective. A cough or a sneeze can project droplets well over a meter, while daily living squeezes the distance well below two meters. Result: infection.

But put on a crappy home-made mask. That disrupts the out breath, reducing muzzle velocity and range. It can basically fail, letting droplets spread half a meter from the cougher or sneezer, and yet the physical distancing (that is supposed to be two meters but gets squeezed down to little more than one meter) starts to be far enough and works well.

Empirical research on this is terribly difficult. We can do whether wearing protects an uninfected wearer from becoming infected. But the interesting question is whether wearing stops an infected wearer from spreading infection. We want to look at each infected person and ask: was the person who infected them wearing a mask? But we don’t even know who infected them!

Worse still is the risk compensation. If we are trying to research the efficacy of the combination, both mask and physical distancing, our research will be vulnerable to people getting closer because the mask makes them feel safe. There could be large, variable, culture dependent gaps between the instructions for the experiment, and what people actually do.

It is tempting to say that we know enough from seeing droplets glinting in the sunlight, and trying to blow out a candle while wearing a crappy home-made mask, that we should prefer theory over impractical experiments.

As others have already stated, the post basically buries the lede.

Lets look at what the CDC is actually contemplating:

So all of this stuff about the efficacious of cloth masks in protecting the wearer is basically irrelevant. An N95 with an outlet valve is great at protecting the wearer (assuming it’s used correctly) … and mostly useless in the context of needing to avoid societal spread. We won’t be able to train 330+ million people, and make, and distribute 10+ billion masks in the timeframe we need. And people wearing outlet valved N95 masks will still spread the viirus to others.

And what is (maybe) the biggest reason we haven’t seen the change happen yet:

Risk compensation (as pointed out elsewhere) could make masks a net negative if the message on “stay at home” and “physical distancing” get diluted.

So, I don’t think this study is at really germane to the question at hand. I’m going to ask my daughter, the tailor in the family, to make me a few masks to wear if/when I go out. But I won’t do anything else different. Still distancing. Still avoiding going places as much as possible.

What makes you say that about the N95 outlet valve? I was wondering about this and put my 3M CoolFlow on in the mirror. Unless I expired hard, the valve appeared to stay sealed. Also, the valve has that little plastic shield that directs the expired air downward. Obviously, this design still emits potentially contaminated expired air, but you have to wonder about the actual exposure radius with these outflow valved respirators.

@Biff_Ditt:

It’s not designed to keep things in, it’s designed to keep things out. And your point about the valve not opening if you don’t “expire hard”? You mean it only expels air right when you cough? The exact time you most need to contain what’s being expelled?

So, if you get the virus, you are still a decent good risk to spread the virus. Absent decent training and regimented use, you won’t be getting the full benefit of protecting yourself either.

And we won’t be able to distribute the billions and billions of those masks, which also makes them inadequate for what we need to do at a population level.

But, if I could wave a magic wand and give everyone N95 masks and make them wear them, without giving up anything else, sure, it’s better on the margin. But that isn’t the real world trade off.

I briefly thought this post was about a different MacIntyre on cloth masks, and expected an analysis on the relative virtues of listening to authorities, personal responsibility, trying not to cause mass hysteria…

This is probably more practical.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3373043/

Seems relevant, substantially more careful, and slightly against the conclusion of the study above.

I’m confused by all of the discussion about boiling, microwaving, ovens, etc. If soap is good enough for our hands to be coronavirus free, why wouldn’t it be good enough for an organic material like cotton?

Soap is good enough, but boiling is better. But putting your hand in boiling water for 5 Minutes is not recommended[citation needed].

I have often in my life seen recommendations to wash your hands in as hot of water as you can stand, but I have not seen that once related to coronavirus. Everything emphasizes soap, scrubbing, and duration, and some explicitly say that cold water is fine. So I sort of assume the soap penetration is the critical thing here and not the temperature. There must be writeups on this.

Supposedly sterilizing coronavirus requires 70 degrees celcius for 30 minutes.

Washing hands with warmer water won’t matter much i assume

So you’re saying, soap and cold water is as good as soap and warm water but substantially worse than boiling water with no soap?

Soap is supposed to be reasonably good at disrupting the membrane of COVID-19 and inactivating it. But really, the reason to use soap and water is to wash the little globs of virus-laden mucus and dirt and such off your hands and down into the sewer, where they can no longer infect you.

Maybe skin is quite good at keeping bad stuff outside, while dead objects like cotton or other fabric is worse at this?

You know, I find it really persuasive that trephination should cure many types of mental illness. Really, really persuasive. Just seems so obvious. The sick person is not himself, obviously, which means there’s someone else inside his head, clearly, so cutting a hole to let that bad spirit out should work. At least, it’s surely better than nothing.

Push back: here the mechanism isn’t really in question – infection rates can be brought down by effective filtering.

The only question is how good a job does a cloth mask do.

If you insist on your example, take a world where the issue actually is An evil spirit in his head, the question is whether the implement used in the surgery can make a big enough hole, (and remember that in this alternate world holes in people’s heads close up instantly if desired, and the holes aren’t dangerous) so you might as well try, maybe the whole will be big enough

Supposedly, it will matter A LOT what kind of fabrics and layering you use, even when you make your own? This seems like it would be crucial information.

Given that the main policy recommendation as a result of this discussion isn’t for medical personal in a medical setting but for regular people in a public setting, shouldn’t studies focusing on that be more relevant?

They aren’t using RCTs but matched controls, but nevertheless aren’t Lau et al (link) and Wu et al (link) essentially seem to be more relevant sources. And both show a substantial effect of a reduction in virus infections through masks worn by regular people in everyday settings.

Sore anyone know how to go about getting ahold of a supply of KN95 masks fairly quickly?

(Thousands or tens of thousands, to the midwest area, without paying through the nose)

Unless you know something the federal and state governments don’t know, please try not to hinder their acquisition and distribution schemes.

The Feds have explicitly not approved use of KN95 masks, so they’ve got no cause to complain.

The Feds didn’t even restock their mask stockpile after H1NI… do you know how many years ago that was? I stocked my basement with N95 masks back then.

Be like the Swiss. Keep your essential supplies in your house, not in your fantasies of bureaucrats conspiring to help you 😉

Unless you happen to live in Taiwan, I guess.. they actually donated 10 million masks to the EU and US slackers.

anonymousskimmer the feds are not exactly perfect in this case regardless of mask type, I do think I could probably allocate better on a small scale

Step one is to speak Chinese, I suspect. Lots of English-language sellers of KN95 masks on the web, all of them stink of scammer; I wouldn’t expect to get anything from them, or if I did, it might be an off-brand coffee filter with two rubber bands.

Did they try to trace how the doctors became sick? A mask worn at work won’t help a bit if you catch the disease from your neighborhood or family. Given the supposed general underpoweredness of this study and the other studies they looked at, eliminating the multiple variables of non-work infection routes is even more important.

I think one particular aspect that makes it not ethical to NOT have a no-treatment control group is when the treatment has to be rationed anyways. So, even on “an Ebola ward”, if there aren’t sufficient masks for everyone, then it’s unethical to NOT assign them randomly (and run an experiment too, if feasible).

The random assignment procedure (‘coin toss’) could (and probably should) take into account factors like, e.g. the severity of a case.

ivermectin kills SARS-CoV-2 in cell culture:

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0166354220302011

Tens of millions of people use ivermectin… we should be able to create a virtual experiment and figure this out in a couple of days!

Interestingly, the CBC also cited the McIntyre study as evidence against mask-wearing. So these one-sided studies, although they answer the question that was of interest to the researchers at the time (do masks protect the wearer), are being cited without qualifiers, and possibly leading to poor decisions in the pandemic context. Wish we could split “protect” into two different words – to distinguish incoming vs outgoing transmissions. Because in this age of TLDR, the distinction keeps getting ignored. EG CBC says (1):

“A 2015 randomized clinical trial (2) found that cloth masks, for example, did not block influenza and respiratory viruses and actually increased the rate of infections among health care workers, and even surgical masks blocked only slightly more than half of virus particles.”

If they just said “did not block incoming influenza and respiratory viruses ” , the reader might be less likely to conclude outright that masks are useless in our current situation.

(Interestingly the article presented both pro and anti mask arguments with more emphasis on the pro … but the McIntyre citation perfectly sums up the prevailing anti-mask arguments, complete with glaring omission of protection in the outgoing direction).

(1) https://www.cbc.ca/news/politics/covid-19-pandemic-coronavirus-masks-1.5515526

(2) https://bmjopen.bmj.com/content/5/4/e006577

What I would be worried about with a cloth mask is droplets from the outside seeping into the fabric. Then you’re wearing a fomite tightly around your nose and mouth.

And virtually no one has tried to find out if they work.

Let’s pause to think about that.

Are we stupid or evil?

Hey Scott, you got a shout out from The Week in Virology podcast. Good job!

https://www.microbe.tv/twiv/twiv-598/

+1

TWIV and the rest of Vincent’s science podcasts are an amazing resource, and it’s fun to see a link between TWIV and SSC (also an amazing thing on the internet).

It would be interesting for some of these studies to get people to bet on themselves as the participants. Imagine if everyone (on both sides) of this trial had risked 10% of their net worth in order to win 5% of their net worth on this. That kind of removes/mitigates a lot of the motivation/effort confounders that could exist. Probably practically impossible though as you may reduce the pool of applicants by 90%+

There are high-speed videos of people sneezing, that show the spread of fluids coming out. I’m curious if anyone has done any similar videos of people sneezing with a mask on (cloth, surgical, or N95/KN95). Intuitively, there should be less material making it out into the world this way, but it would be useful to have some confirmation of that.

Someone else may have linked to this paper in Nature (I think it’s behind a paywall–sorry.) It describes a small experiment involving influenza, rhinovirus, and a cold-causing coronavirus. It suggests that surgical masks probably do help slow the spread of both big droplets and aerosols somewhat in the cold-causing coronavirus and in influenza. The biggest issue here is that n is small, but this at least suggets that putting everyone in a surgical mask would probably decrease the spread of the virus. (That is, it would lower the probability that a susceptible person would catch the virus, conditioned on them being exposed to an infected person, because the infected person would spread fewer infectious droplets of various sizes into the area.)