[source: sowhatfaith.com]

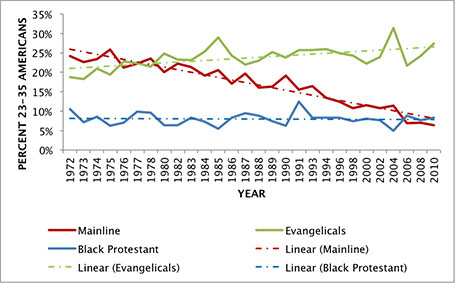

Patheos’ Science On Religion points out that liberal Protestantism is dying even as more conservative Protestant movements thrive. This seems counterintuitive in the context of society as a whole becoming less religious and conservative. So what’s going on?

In the early 1990s, a political economist named Laurence Iannaccone claimed that seemingly arbitrary demands and restrictions, like going without electricity (the Amish) or abstaining from caffeine (Mormons), can actually make a group stronger. He was trying to explain religious affiliation from a rational-choice perspective: in a marketplace of religious options, why would some people choose religions that make serious demands on their members, when more easygoing, low-investment churches were – literally – right around the corner? Weren’t the warmer and fuzzier churches destined to win out in fair, free-market competition?

According to Iannaccone, no. He claimed that churches that demanded real sacrifice of their members were automatically stronger, since they had built-in tools to eliminate people with weaker commitments. Think about it: if your church says that you have to tithe 10% of your income, arrive on time each Sunday without fail, and agree to believe seemingly crazy things, you’re only going to stick around if you’re really sure you want to. Those who aren’t totally committed will sneak out the back door before the collection plate even gets passed around.

And when a community only retains the most committed followers, it has a much stronger core than a community with laxer membership requirements. Members receive more valuable benefits, in the form of social support and community, than members of other communities, because the social fabric is composed of people who have demonstrated that they’re totally committed to being there. This muscular social fabric, in turn, attracts more members, who are drawn to the benefits of a strong community – leading to growth for groups with strict membership requirements.

The evolutionary anthropologist William Irons calls demanding rituals and onerous requirements “hard-to-fake symbols of commitment.” If you’re not really committed to the group, you won’t be very enthusiastic about fasting, abstaining from coffee, tithing ten percent, or following through on any of the other many costly requirements that conservative religious communities demand. The result? Only the most committed believers stick around, benefiting from one another’s in-group-oriented generosity, social support, and community.

Since then, Sosis has also demonstrated that religious Israeli kibbutz members are more generous in resource-sharing games than both secular, urban Israelis and secular kibbutzim. He argues that this is, in part, because demanding rituals – such as having to pray three times a day and study Torah many hours a week – serve as a signal of investment in the kibbutz community. The more rituals you participate in, the more invested you feel – and the more willing you are to sacrifice for your fellows.

But if your community doesn’t have any of these costly requirements, then you don’t feel that you have to be really committed in order to belong. The whole group ends up with a weakened, and less committed, membership. Liberal Protestant churches, which have famously lax requirements about praxis, belief, and personal investment, therefore often end up having a lot of half-committed believers in their pews. The parishioners sitting next to them can sense that the social fabric of their church isn’t particularly robust, which deters them from investing further in the collective. It’s a feedback loop. The whole community becomes weaker…and weaker…and weaker.

Even though I’ve quoted like half the blog post, it’s worth looking at just to see the empirical and statistical arguments for their hypothesis.

Not that any of this should come as a surprise. This is the same principle of maintaining separation between in-group and out-group members which has worked so well for so many eons. But making the in-group follow specific rules to prove their dedication does seem particularly effective.

I’ve been thinking about this in the context of atheist religion-substitutes. I went to the Secular Solstice last weekend, and it was held in the New York Society For Ethical Culture building. As usual I avoided social interaction by beelining to the nearest reading material, and in this case that was a plaque detailing the group’s history. The Society for Ethical Culture was founded in 1877 by an ex-rabbi (of course it was an ex-rabbi) and looks pretty much exactly like every atheist religious substitute today. That got me a little depressed. Atheism has been trying the same things for the past one hundred fifty years and, I would argue, largely failing for the past one hundred fifty years. Religion substitutes are hard.

The biggest atheist religion-substitute I know of is Sunday Assembly. I recently came across their “Ten Commandments”:

1. Is a 100 per cent celebration of life. We are born from nothing and go to nothing. Let’s enjoy it together.

2. Has no doctrine. We have no set texts so we can make use of wisdom from all sources.

3. Has no deity. We don’t do supernatural but we also won’t tell you you’re wrong if you do.

4. Is radically inclusive. Everyone is welcome, regardless of their beliefs – this is a place of love that is open and accepting.

5. Is free to attend, not-for-profit and volunteer-run. We ask for donations to cover our costs and support our community work.

6. Has a community mission. Through our Action Heroes (you!) we will be a force for good.

7. Is independent. We do not accept sponsorship or promote outside organisations.

8. Is here to stay. With your involvement, the Sunday Assembly will make the world a better place.

9. We won’t tell you how to live, but will try to help you do it as well as you can.

10. And remember point 1…The Sunday Assembly is a celebration of the one life we know we have.

But it’s tough for me to picture these on big stone tablets. And yeah, I know the reason we don’t have the original tablets is that when Sunday Assembly Moses came down from Mt. Sinai he saw the Sunday Assembly people only celebrating life 95 percent, and waxed wroth, and broke the tablets, and then ordered the Levites to slaughter all the men, women, and children who had participated in this abomination. And then…

…okay, that’s probably not the reason they’re not on tablets. But that’s just the thing. It’s impossible to imagine these commandments inspiring strong emotions in anybody. It’s impossible to imagine people sinning against them in a meaningful way. Most of them aren’t even commandments. They’re more like promises not to command. If you absolutely must compare this pablum to a list of ten points, the proper analogy is less to the Ten Commandments than to the Bill of Rights.

(“God shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof…”)

Atheist religion-substitutes seem unconcerned about or actively hostile to placing rules upon their members. I mean, there are a lot of things that are like “You must be tolerant”. But in practice everybody thinks “intolerant” means “more intolerant than I am, since I am only intolerant of things that are actually bad,” so no one changes their behavior. People say that we have advanced by replacing useless rules like “don’t eat pork” with useful rules like “be tolerant”, but rules against eating pork resulted in decreased pork consumption whereas it’s not clear that rules like “be tolerant” result in anything.

The only secular-ish group I have ever seen which is truly virtuous in this respect is, once again, Giving What We Can. They demand that members give ten percent of their income to charity. To join you must request and sign a paper copy of a form pledging to do this. Every year, the organization asks you to confirm that you are still complying. I don’t know what happens if you aren’t, but I assume it’s too horrible to contemplate. Maybe Peter Singer breaks into your house and kills you for the greater good.

But the point is, here’s an organization that has a very specific rule and demands you follow it. And even though their pledge form looked kind of like a tax return, signing that form was more of a sanctifying and humbling experience than any of the religion-substitutes that try to intentionally generate sanctification. Not because I was at some chapel where someone gave a rousing sermon overusing the word “community”, but because I was binding myself, voluntarily submitting to a higher moral authority.

Someone on my blog a while back used the word “nomic” to refer to a subculture based on following a rule set, sort of like an opt-in religion without beliefs or supernatural elements. I looked to see if it was a real thing but couldn’t find any references other than the card game. But I find the idea interesting. If it contains mechanisms for treating subculture members differently than non-members, it seems like an optional add-on module to government, and a strong candidate for the sort of thing that could develop into a healthy Archipelago.

The more of Scott’s posts I read, the more they seem to be saying obvious truths that anyone could say. Maybe I’m in a culture bubble.

And yet, few people do say these things. If there is one thing we can take from in-group rituals, it is that communication isn’t about information content, but also signalling about focus. Basically, you are double right.

I feel like Scott has had several posts recently that are re-iterating opinions he has already expressed, but in a more complete, coherent way. I am pretty sure he has made the argument in this post before on this blog.

Human history requires that we get obvious truths stated and restated over and over again, because we’re a damn stupid species that constantly goes “yeah, but maybe the fire won’t burn me this time if I stick my hand in it?”

Also, new generations have this uncanny habit of coming along out of nowhere (babies: where do these mysterious alien creatures arrive from? what is their purpose? what goals are they working towards?) and imagining that they are the first persons in the history of the world to ever have these particular experiences and emotions and problems (12th century amour courtois: you don’t understand me, I’m in looooovvveeee and I’m suffering and nobody has ever felt like this before!!!!)

“And the burnt fools bandaged finger

Goes wobbling back to the fire.”

Rudyard Kipling, “The Gods of the Copybook Headings.”

http://www.kiplingsociety.co.uk/poems_copybook.htm

I remember that Neal Stephenson made almost exactly the same point in The Diamond Age where the one binding ritual of the Reformed Distributed Republic was that you had to ritually save the life of or have your life saved by another member each year.

Repeating the obvious is a useful function.

Or just repeating the true.

Yeah, this is at least old fare on the rationalist interwebs. On Less Wrong it is called evaporative cooling, and for Hanson it is costly signalling.

Evaporative cooling doesn’t say the group will grow, it says it will shrink but become stronger.

Personally, I *had* heard this before – from conservative xians. I hadn’t seen the data, or a relatively dispassionate (if basic) analysis of “so what do we do next?”

Obviously there is more going on than evaporative cooling (costly signalling, consitency and committment effects, etc.), but I think that it is a fair first order approximation if the group one is talking about is American xtianity as a whole. As to what to do next, I suppose it really depends on your goals. Kevin Simlar over at MeltingAsphalt has what I consider some of the better steelmanning of religion from an atheist perspective, but is again more descriptive than proscriptive.

Good on ya for noticing that this kinda makes the opposite prediction from the “evaporative cooling” one. Both can’t be true at once for a group; either it is getting more fanatical and smaller, or it is getting more fanatical and larger.

Thing is, evaporative cooling doesn’t predict that groups that become more devoted will become smaller. It predicts that when a belief group shrinks, it will shrink by losing its least devoted members, and therefore become more devoted. Eliezer’s big examples are prophecy-believers whose prophecies are disproven, and Objectivists after Ayn and Nathaniel’s big messy breakup drama.

We can imagine this being a cycle; call it the Cult Engine:

1. Devoted group attracts new members who want to belong to a devoted group.

2. Bringing in new members causes socialization costs, as new members come in faster than the group can indoctrinate them.

3. The center or leadership of the group makes demands that bring members into conflict with larger society or reality, such as false prophecies or expensive signaling.

4. Less-devoted members ditch the group, while more-devoted ones remain (“evaporative cooling”).

Over time, this should be a sorting process: some people join the group and become devoted members, especially after going through a few compression cycles. Others join, then leave shaking their heads at the cult’s weird demands.

The cult engine cycles through the population, accumulating devotees, and not accumulating wishy-washy liberalizers.

If one of these steps fails too much, the engine stalls:

1. If the group stops attracting new converts, it has to make peace with the human genome and settle down into the family way — gaining new members primarily by having babies — like the Amish. It stops cycling through the population for converts, but may well become a stable part of society.

2. If the group attracts new members but can’t socialize them or make demands of them, it has an Eternal September and loses its distinctness as a group.

3. If the group stops making demands of its members, it becomes Ethical Culture and withers away due to boredom. If on the other hand the demands exceed the interest of new members and one of them is “don’t have sex,” the group becomes the Shakers and withers away due to die-off.

4. If the tension between the group and society becomes too large, and the group is too small, society crushes it like the Branch Davidians at Waco. Surviving a crush attempt is a great way to focus the group, though — see the Mormons in Illinois or the entire freaking history of the Jews.

This could be evaporative cooling among mainline protestants. That is, as their congregations shrink those who remain shift toward evangelical strains.

I agree that “difficult things makes groups stronger” is old news, but I don’t think anyone had pointed out the relation to atheist religion substitutes before.

I’m currently reading Sociology: A Very Short Introduction, and there’s a description of the ways in which radical groups become less radical over time (the “Iron Law of Oligarchy”), and how that’s mitigated. I think it’s a pretty standard result in sociology, if I’m not reading too much into that.

Although, no mention of cognitive dissonance, which in this case is actually a relevant concept (the general populace seems to think that it is simply another word for “hypocrisy”, when in fact it means something quite different).

Yes, it annoys me greatly that the term cognitive dissonance has become popular lately, but with the wrong meaning. The proper sense is a very powerful intellectual tool for understanding behavioral change and manipulation, whereas the common usage is merely an epithet.

Religion substitutes being hard to organize is something to be celebrated – if anything, it should be harder. It means that it’s more difficult (though still not very difficult) to convince certain kinds of people to join groups that impose burdens on them and organize them into in-groups. The atheist equivalent of church isn’t (and/or shouldn’t be) “Ethical Culture” and giving 10% to efficient charities, it’s sleeping in on Sunday and rejecting imposed obligations.

I can understand your libertarian desire to not have a government which forces people to give resources towards a common goal, given their poor track record in comparison to groups which are actually trying to be effectively altruistic there isn’t much reason to support liberal social policies. But you also seem opposed to basically any social structure which incentivizes pro social behavior in any form, whether it is consensual or not. Why would making the creation of alternatives to religion which make people happy while encouraging them to save lives more difficult benefit you in any way?

My suspicion is that you just don’t like getting guilt tripped by people with a holier-than-thou attitude, but does this REALLY outweigh the costs.

Because I care about people and want them to do the right thing and for the right reasons, rather than make themselves uncomfortable – especially if they’re making themselves uncomfortable for the wrong reasons. I dislike seeing people wracked with guilt, or even making themselves uncomfortable for some reason that doesn’t in the long run benefit them – if it’s a burden and no one is forcing you to carry it, then don’t carry it. At least, that’s what I think about things like Giving What We Can. As far as alternatives to religion in general, they strengthen loyalty to the ingroup (which is defection against everybody else), increase bias (holding the ingroup and outgroup to different standards), and promote partisanship.

By the way, I’m not against social structures that incentivize pro-social behavior. I’m in favor of capitalism, and also think that some people would be made happy by donating to charity – but it shouldn’t be pushed on people as the correct moral choice regardless of what makes them happy.

Better the right thing for the wrong reason than the wrong thing.

Maybe. If they have the wrong reasons, they’re less likely to do the right thing consistently, even if they do it from time to time. But what I meant was more that charity is the right thing to do only if you have the right reasons for it.

>I dislike seeing people wracked with guilt, or even making themselves uncomfortable for some reason that doesn’t in the long run benefit them – if it’s a burden and no one is forcing you to carry it, then don’t carry it.

But you’re not understanding: acting charitably, is not, primarily, about benefiting oneself, but benefiting *others*, even at cost to one’s self. If you ultimately prioritize yourself (that is, you give on the basis of some form of rationalistic self-interest) all that’s going to happen is you will eventually find it more rationally in your self-interest to not give all that much.

And if one is serious about devoting one’s life, and by extension, society, to that idea of prioritizing others above oneself, then by necessity I myself will need to be discomforted. That is, you can’t serve two masters here; you might be able to serve others and *incidentally* have some level of comfort, or you might serve yourself primarily while occasionally and incidentally giving charitably, but there is a bottom line here that will take priority over other considerations when it conflicts with other things in your life. (Protestant preachers tend to phrase this idea like this: Your God is what you choose to serve.)

If I, by my inaction and indolence, fail to donate money that could save the life of people in the third world, is it somehow commendable that I can follow through with my failure to give in comfort? *Shouldn’t* I be uncomfortable with that? Why the hell should I be proud of that kind of attitude? I should be ashamed, and if I feel a conflict coming up here, well, either I’m going to turn off my shame-circuitry and indulge myself, or I’m going to act in accordance with my charitable duties until I don’t anymore. But it seems strange to suggest we can sit on a fence here.

Asking people to prioritize others over themselves is deeply horrifying. This is basically the only thing Rand did get right, and the reason so many people find her so compelling.

(I care a lot about other people, but I do that because it makes me happy. It’s not putting them over me, and it shouldn’t be).

You can definitely serve two masters, or 7 billion, or however many. Of course you can play verbal/mathematical games and call the weighted-average-vector of terminal values a “single master”, but that has the air of fiction about it. A useful fiction in some circumstances (utility theory in economics or game theory), but not faithful to the ways we think about everyday life. Nor is it an improvement over those ways for thinking about everyday choices.

That depends on what you mean by “acting charitably”. I used it to simply mean “giving to charity”, but you seem to be using it to mean “benefiting others for their own sake”. Indeed, I do think that someone pursuing their rational self-interest (and therefore not benefiting others for their own sake) is probably not going to give high amounts to charity.

I’m not suggesting sitting on a fence between self-interest and self-sacrifice. I’m saying we should go with self-interest all the way, but sometimes that involves some charitable giving anyway.

@Jadagul

“Asking people to prioritize others over themselves is deeply horrifying.”

So if you’re considering killing someone so you can steal $100 from them, and I ask you to prioritize the other person not dying over you getting $100, that’s deeply horrifying?

@Paul Torek

“Of course you can play verbal/mathematical games and call the weighted-average-vector of terminal values a “single master”, but that has the air of fiction about it.”

There’s nothing fictional or game-playing about it. If you’re going to go around accusing people playing games every time there’s a large inferential distance, there isn’t going to be much useful discussion.

@blacktrance

“I used it to simply mean “giving to charity” ”

That’s a rather limited meaning.

If I were the sort of person who thought $100 was worth killing over, that would make me horrifying. That doesn’t make you any less horrifying.

You shouldn’t tell me to put others over myself. You should convince me to value other people in such a way that I don’t want to kill them.

I know this sounds like sophistry, but it really isn’t. I do nice things for other people because it makes me happy to do nice things for other people, not because I hate it but feel obligated to do so.

(In general. Visiting my parents for Christmas is about half and half so I’m really crabby this week, sorry).

>If one is serious about devoting one’s life, and by extension, society, to that idea of prioritizing others above oneself

I don’t think of myself as prioritizing others above myself (and practically, not even at the same level of myself). But prioritizing them even some means recognizing that preventing child deaths is more important than me having more expensive clothes, for example.

Jadagul, we are not single points in priority space. Allowing some high-priority needs of others to supersede your low-priority wishes isn’t horrifying.

Note, even the proposal here is ‘90% for you and 10% for others’.

—

“As far as alternatives to religion in general, they strengthen loyalty to the ingroup (which is defection against everybody else)”

No, it’s not.

Sure is. You can rate everyone ++++++ and your group +++++++, but that’s only obfuscation and not functionally different from rating everyone – and your group +.

If everyone in the world is equally likely to help everyone, then ten people promising to help each other a bit more are defecting, even if they aren’t going out to harm everyone else, just passively absorbing resources by redirecting them to their own dome.

No, that is not correct.

There are aspects of loyalty that are negative sum, e.g. being biased when it’s important to be fair, and aspects that are positive sum, e.g. focusing enough attention on helping an ingroup member when diluted, less focused attention is useless.

You’re right, I was thinking strictly of the cases where the community props its members up the overall social ladder, like helping them get jobs, but there are aspects to it which don’t disadvantage outsiders.

My model of you is basically just imagining the straw man Ayn Rand fan, I’m curious if there is actually any situation where you would go against that.

I support a carbon tax, am against the gold standard, and I’m not as dismissive of mainstream economics and philosophy, unlike Rand. As for the straw Rand fan – you don’t see me quoting long passages from Atlas Shrugged, or calling people looters and moochers all the time, do you?

You call them defectors rather than looters or moochers.

Some people use “defector” as a term of condemnation or an insult, but I don’t. I, too, am a defector – if the incentive structure is set up a certain way, then defecting is the rational thing to do. But the existence of defectors is a sign that the incentive structure should be changed.

I’m quite happy to reject the imposed obligation of not kicking you in the head and stealing all your money, blacktrance, if that’s any comfort to you? 🙂

Actually, that’s a lie: I would not be at all comfortable kicking you in the head and stealing your money. But some people would be. Some people would be happy to. Which is why any form of functioning organisation has to impose some kind of sanctions or requirements or penalties or even Codes of Conduct; not to make people guilty for no purpose, but to balance out the fact that some people will only be restrained from doing harm by the prospect of punishment or sanction.

I don’t want to get into the whole happiness versus virtue as a rule of ethics debate, but there are those who won’t “do the right thing for the right reason” either because they don’t recognise it as the right thing or don’t care: they’re happy to do what benefits them and to hell with the rest of you (see your carbon tax idea: if that’s not a coercive measure of imposing socially-sanctioned guilt, what else do you call it?)

It’s to your advantage to choose not to kick me in the head, though – at least, as long as I agree to restrict myself in the same way.

The general principle is that there are certain restrictions that are mutually advantageous to those being restricted, and because it’s advantageous for you to make use of them (by restricting yourself in exchange for others doing the same), it’s not a case of self-sacrifice. One example of this in practice is a right to not be murdered. Another example is a carbon tax, which is about coordination, not guilt. Neither of them is self-sacrificial, because you’re better off than you would have been if no one adhered to the restriction. The same cannot be said for extreme charitable giving (e.g. Giving What We Can), where you’re hurting yourself to make others better off.

“It’s to your advantage to choose not to kick me in the head, though – at least, as long as I agree to restrict myself in the same way.”

Not if I kick hard enough!

Neither of them is self-sacrificial, because you’re better off than you would have been if no one adhered to the restriction.

But am I better off? I can’t buy my nice big expensive gas-guzzling motor that shows how big a cheese I am since I have the spare cash to blow on this yoke* because of your silly old carbon tax, and it is supposed to benefit some not even in existence yet future generations if the land where they’re living is not under salt flood water.

Screw them! How can I participate in the politics of envy if you and your bleeding-heart buddies in the government are slapping these punitive taxes on me?

*May be triggered by recent radio ad campaign I heard that was predicated on, basically, “Sure you’re a miserable grump with no friends because you worked and sweated every hour while other people were having lives, but now you’re The Boss and can buy our Big Luxury Car in order to rub their noses in it that you’re The Boss and rich and they’re not The Boss”.

It was horrible. It wasn’t even “whee, this car is fun” or “indulge yourself”, it was “the only pleasure left in your wizened dried husk of a heart will be to evoke envy in others”.

Presumably the carbon tax will actually make you better off, because the negative effects of global warming aren’t limited to future generations living underwater, but also to effects on agricultural production. You probably buy food, so you care about that.

Would you not support a carbon tax if you thought the negative externalities were farther in the future but the same in magnitude? Do you think sufficiently old people should be against a carbon tax?

It definitely makes sense for old people to be against a carbon tax (unless they care about future generations). As for the general case of the negative effects being further into the future, that’s an interesting question that I’ll have to think about.

Nope. Even if the carbon tax made a significant difference in warming and did so at a reasonable cost (both pretty unlikely assumptions), the near-term effects of global warming on agriculture in general (say, over the next 50 years) are generally predicted to be positive. In northern climates where most of the food is grown now, a little more warmth gives you a longer growing season, and a little more CO2 helps crops grow better. Closer to the equator where it’s too hot for most food crops they don’t need any more warming but the extra CO2 makes forestry more productive.

According to the IPCC the first 1-3 degrees of warming is a net positive for food. It’s true that their predictions are for it to EVENTUALLY be a negative factor, but that’ll be after we’re dead so by your own logic we can’t take that into account in deciding whether to have a carbon tax.

(see here, section 19.3.2.3 “Aggregate market impacts” https://www.ipcc-wg2.gov/AR4/website/19.pdf . The admission that expected warming this century probably HELPS FEED THE PLANET is always made begrudgingly and with lots of “…though it *could* be worse!” hedging, but it’s there. In this iteration of the report, the relevant quote is: “Some estimates suggest that gross world product could increase up to about 1-3°C warming, largely because of estimated direct CO2 effects on agriculture, but such estimates carry only low confidence.” )

Deiseach on love: Pleasure and indulgence will ruin you and doom us all. Work and sweat every hour and harden your will against the whims of your heart.

Deiseach on cars: Live a little! Don’t let work turn you into a wizened husk!

I’m not saying this is at all contradictory. I am saying it is hilarious.

In the phrase attributed to Sir Boyle Roche, “Why should we care for posterity? What has posterity ever done for us?”

Of course I can afford food, I’m rich enough to buy, tax and run a huge status-signalling machine! Poor people grow and harvest my food for me; so what if quinoa becoming a cash crop means the harvest gets exported to the West and a former staple gets priced off the market for the natives?

Or to quote the Scottish comedian Frankie Boyle: “In Scotland we have mixed feelings about Global Warming, because we will get to sit on the mountains and watch the English drown”.

🙂

Leo, I do think people should be very aware of the consequences of indulgence. But for feck’s sake, if you’re going to sin, at least get some enjoyment out of it! That car ad was all about stoking envy, and it didn’t even pretend you would get any benefit or enjoyment out of your expensive status symbol other than “yes, you’ve made yourself miserable all your life only for the money to buy useless products like this, the only benefit of which is that they make other people feel bad”.

That’s not how I want to live: if I’m going to be working hard and scrimping and going without and generally being a secular ascetic, the least I’d want is “the end result will give you or others pleasure and happiness”.

That’s why Eliezer’s view in the quoted post about “Church versus Taskforce”, whatever his real views are, about stained glass giving him the heebie-jeebies is so sad. His Brave New World is a vision of vast bare concrete walls with no chink to let the light in? Video screens playing useful, improving, instructive lectures with occasional breaks for (doubtlessly carefully-selected) popular entertainment, but no expression of the arts and crafts of artisans in making coloured glass, putting it together in designs, and building it into walls to intertwine made-things with natural-things so that humans can relish human ingenuity and beauty? That’s a sad, grey, anthill world and I don’t want to live in it!

While I can’t find the post you’re referring to, I rather suspect Eliezer’s heebie-jeebies are restricted to stained glass, not art in general, and are a statement of personal preference, not a normative prescription.

Heck, heebie-jeebies aren’t even really a personal preference, just a psychological reaction.

But then it’s about how you frame it. If you frame it as “agree to refrain from kicking me in the head”, then it’s not to your advantage. It’s only when you couple that with “in exchange for me agreeing to refrain from kicking you in the head”, and treat those two agreements as a single unit, that they become advantageous. With the carbon tax, you believe that it is to everyone’s advantage to have it, but there are others than disagree with you about how harmful carbon dioxide is. So for them, it is an imposed obligation. Charity can be viewed as being in one’s rational self-interest, if it’s framed in terms of counterfactual precommitments with respect to the Rawlian Veil.

Regarding carbon dioxide, that’s an empirical matter. Either it is sufficiently harmful for people to rationally restrict themselves, or it isn’t.

That would be a misleading framing, because we don’t have reasons to care about what bargains we would’ve made behind the Veil of Ignorance. It’s like Parfitt’s Hitchhiker – you want to commit to pay all future drivers from now on, but given the situation you’re in now, paying existing drivers would be a loss. It’s the same with the Rawlsian Veil – charity may have a positive expected value to people who don’t know their position, but we aren’t and have never been in that state, so it doesn’t matter.

Yes and no.

By “atheist religion substitute” I don’t mean “turning atheism into a religion”, I mean “a thing that fills religion’s mental niche, but is not incompatible with lack of belief in God”. Sleeping in on Sundays isn’t it.

I didn’t think you meant turning atheism into a religion. Of course, sleeping in on Sunday is as much of a religion substitute as not eating is a cuisine. As other commenters have pointed out, there are things that may fulfill religion’s mental niche while being secular (e.g. political activism), but in certain respects they’re still less similar to religion than they could be. But I think one of the advantages of atheism is that it doesn’t have that “thing that fills religion’s mental niche”, and part of rationality is combating the presence of that niche to the extent that it exists.

But I think one of the advantages of atheism is that it doesn’t have that “thing that fills religion’s mental niche”

I think atheism does, if you think of the “reasons/search for meaning/purpose of life” stuff that religion at least in part claims to answer. How often do you see things like “Cosmos” and its remake do the Big End Vision bit where we’re told that the universe is a vast trove of marvels and wonders and science reveals all these to us, so humans can find transcendence even without religion?

I’m sure at least some atheists do find “meaning of life” satisfaction in atheism as a philosophical, ethical or cultural system to provide a framework and structure of meaning, even if it’s Douglas Adams “The answer is 42” type materialism, or the British bus ad campaign “There’s probably no god, now stop worrying and enjoy your life”.

Even if atheism provides “Humans are the ones who create and define such a concept as ‘meaning’ in a materialist, determinist universe, so it’s in your hands to go out there and make what difference in the world you think is best” as a principle, it’s at least an alternative to the Baltimore Catechism question and answer:

You confuse the issue by speaking of imposed obligations, since these groups are voluntary (unless they’re employing psychological manipulation). It seems society has progressed considerably thanks to the general rise in standards of personal conduct (something I’m particularly conscious of at the moment, as I’m presently reading Steven Pinker’s The Better Angels of Our Nature. Of course a society guided consistently by an ethic of compassion will be understanding of those who are unable to live up to it for reasons like intellectual impairment or innate sociopathy.

Impositions of obligations can be non-coercive but still bad. There are other examples of non-coercive imposition: “If you really loved me, you’d do X”, “You’re a bad person if you don’t share this link”, “Repent for your sins!”, etc.

Why not look at the societies that have become largely non-religious? Countries such as Sweden or Japan were just as religous as others a few centuries ago, and now being a religious believer is a slightly odd, slightly suspect minority behavior.

I don’t know what did happen (having a state church in Sweden is sometimes cited as a reason, but Japan never had a similar religious monoculture) but I do know that “sekular alternatives” played no role at all. There never were non-trainspotting communities celebrating their shared disinterest in trainspotting. And why would there be?

Mightn’t State Shinto, even though it was only imposed in anything approaching an organized way for eighty years, have played a similar role in Japan? It seems to me that it was widely accepted enough for a long enough period that Japanese culture could’ve react against it in a similar way to Swedish (and, to a perhaps-lesser extent, British) culture reacting against its own state church.

As you say, it wasn’t for that long, and it wasn’t all that organized if I understand it right; it was only a state religion – in Sweden, the church was effectively a part of the public administration for centuries. You could certainly argue that the Catholic church is at least as, and likely more, embedded in Italian life as _the_ societally appproved and sanctioned organization as Shinto ever was during the Meji era.

Also, they never pushed to homogenize or drive out all the buddhist sects in the country. I think both the situation and the time frame is too different to serve as a common explanation.

But the Swedes haven’t really “reacted against” their state church. The Lutheran Church in Sweden, like in Finland, is liberal, inclusive, and as secular as an organization can be while still being called a “church”, and most of the people who identify as non-religious are still members of the church!

In Finland, the main force driving people to renounce their membership in the Church these days seems to be the conservative views of the chairwoman of the minority Christian Democratic party, views that are emphatically not part of the mainline dogma (and neither the party nor the chair herself has any official position in the Church!) Ironically, when the Archbishop recently stood for gay marriage, that too triggered a wave of resignations – this time by the more conservative members who felt the Church has become way too liberal!

Right. The Swedish Lutheran Church has declined much the same as the US mainlines, and for the same reason. (Whatever that reason is, though I concur with Handle’s take.)

This may be analogous with the case of biological monocultures. In a region with only one super-dominant organism, an infection that infects that organism can level the whole ecosystem. In a nation with one super-dominant religious body, an infection in that body can cause its total collapse. But the US has never been a religious monoculture; it’s always had a plurality of sects. Those that were susceptible to progressivism are dying of that disease, but those that are more resilient are able to thrive in the new space created for them.

IANAS (I am not a Swede), but I think another thing may be that Sweden’s biological and cultural homogeneity makes it safe for Swedes to abandon their traditional religion. Their “Swedishness” is enough social glue that the church is redundant, or at least something that can be ignored without fear of social isolation or unraveling.

Yeah, but people don’t flock from liberal mainline lutheranism to conservative evangelical sects like in the US! It’s mostly secular church-members-in-name-only staying that way or resigning and becoming officially nonreligious. The conservative sects have stayed largely irrelevant; most people who can be said to be actually religious are content with staying with the mainline church. Many people simply don’t seem to have a need in their lives for an organized religion or an equivalent.

@Johannes, I don’t have a ready explanation for that. One hypothesis would be that a competitive religious environment increases religiosity across the board, even in the mainline churches, such that even the mainliners have a conservative, highly religious segment which jumps ship (or at least complains loudly) as the decline into secularism advances; while the churches in the non-competitive environment have no such segment, or a much smaller segment.

I think of it as a monopoly losing customers while many competing suppliers always innovate.

Either way, this is why I think Iran will be a very atheist country in a generation or three.

It is too early to learn much from the Swedish or Japanese experiments. We need a few more generations to see how things shake out, and the demographics frankly do not look promising so far.

The problem with saying that it’s too early to learn from prominent examples like Sweden or Japan is that you’ve basically made the original claim unfalsifiable–none of the possible evidence is good enough to count.

Sometime we really don’t have good evidence available! That is not a case you should discount!

But see also this comment. History is available for perusal.

I wonder what you think Sweden’s fertility rate is, and whether you’ve looked it up recently.

Well, if you believe Internet commenters, Sweden is being taken over by increasingly extreme Muslims, so perhaps they’re not an exception to the rule.

“but I do know that “sekular alternatives” played no role at all. ”

Probably not explicitly, as groups that demanded membership, but I believe that secular (i.e., state-sponsored) alternatives to the tangible benefits of belonging to a religion – public schools, kindergardens, hospitals, retirement homes, counselling, secular wedding ceremonies etc. – are important.

Interestingly, for many Finns, at least, one of the very few reasons to retain their church membership is to get a church wedding.

Because (almost?) every other society in history has had religion play a role in community life. It seems like such a structure would naturally form as long as there are bunch of humans in one place. And if it didn’t, there would be reason to feel like something important was missing.

It seems to me that religiosity negatively correlates with the perceived level of safety and security, of all kinds (financial security, health, security against crime, ethnic persecution, foreign invasion, etc.)

I suppose this is because religious communities provide both material benefits to their members and feel good delusions to quench their anxiety (“the opium of the people”).

Japan, for instance, is a country with high median material wealth, the highest life expectancy in the world, low crime, ethnically homogeneous, low risk of war.

Sweden is, or at least used to be, similar. Right now however, like other wealthy European countries, they seem to have problems with the large scale Muslim immigration: a significant fraction of second and third generation immigrants radicalize their religious beliefs, possibly due to perceived hostility of the natives, which in turn makes the natives even more hostile. Christianity might make a come back.

(I wrote the comment above. I’ve no idea why it appeared as Anonymous)

> It seems to me that religiosity negatively correlates with the perceived level of safety and security, of all kinds (financial security, health, security against crime, ethnic persecution, foreign invasion, etc.)

Generally true, but the US is an outlier.

Is it? Compared to most other developed countries like Japan and Sweden, the US has higher crime rates, lower social welfare and higher racial, ethnic and religious dishomogeneity.

…dishomogeneity.

Is there some reason you felt the word “heterogeneity” no longer suffices?

“Religious belief and activity are seen as a

superficial coping mechanism that is easily cast

offwhen the majorify in a given sociefy enjoy

democratic governance and a secure,

comfortable middle-class lifestvle.”

http://www.gregspaul.webs.com/questionssolved.pdf

(Much else of Codexian interest on the same site).

Alternatively, riches give people the delusion of self-sufficiency. That one’s a rather old observation, actually.

Seems to be true in the present, but how much in the past?

China seems like it would provide a good case study. There was a large stretch of time where they literally, and pretty justifiably, considered themselves the center of civilization. Presumably, they felt pretty secure during this time. Were they also non-religious then? Same for Japan during their insular period.

I understand that the Chinese also developed a theory of dynastic cycles. That probably contains useful information as well.

(Interestingly, once it became clear that basically every European power could push China around without breaking a sweat, they turned hard towards Marxist atheism. That may not count as “less religious,” though; I basically agree with the others here that Marxism/progressivism/SJWism are the atheist religions.)

They tried Christianity first. As with Maoism, many people died.

China was dominated by foreign powers for over a century before the communists took over. And Marxism was a European ideology that was supported by Russia.

>(Interestingly, once it became clear that basically every European power could push China around without breaking a sweat, they turned hard towards Marxist atheism. That may not count as “less religious,” though; I basically agree with the others here that Marxism/progressivism/SJWism are the atheist religions.)

a much broader segment of the educated population fixed on the KMT’s fascism (that’s what they called it prior to ww2) than communism. the peasants just signed up with mao because he let them kill their landlords.

I wouldn’t find implausible that the average citizen of Medieval China or Medieval Japan felt more secure than the average citizen of the war-ridden plague-ridden Medieval Europe and, as a result, was less religious.

In fact, AFAIK there were no holy wars in Medieval China and Japan, or persecutions of heretics, or the various manifestation of religious histeria and fundamentalism that were common in Europe.

China and Japan, on the other hand, had various schools of Buddhism in addtion to their local and equally varied traditional religions (Chinese folk religion and Shinto) which coexisted largely pacefully.

Also, Medieval Europeans devoted a significant fraction of their resorces to build giant gothic cathedrals. While China and Japan also have some large temples, I doubt that the fraction of per-capita resources spent on religion was comparable.

Medieval Chinese and Japanese people probably felt more secure compared to other Medieval people, but obviously they must have felt much less secure compared to anybody living in a present-day developed country, which is consistent with them being more religious than modern people living in developed countries.

>In fact, AFAIK there were no holy wars in Medieval China and Japan, or persecutions of heretics, or the various manifestation of religious histeria and fundamentalism that were common in Europe.

Japan is famous for having forcibly rolled back christianity, and china had what was arguably the biggest religious war in history. And when you go back earlier, there is definitely on again off again persecution of whatever sect was out of favor by the in favor sect, but I don’t know enough to know how vehement it was.

The Taiping Rebellion happened in the mid 19th century, that’s hardly Medieval. I don’t know much about Christianity in Japan though.

Not this again. Don’t make me start talking about Burma. (Did you know there have been Buddhist religious wars? And that there are Buddhist fundamentalists? And that there are Buddhist fundamentalists today?)

Not that this was confined to Burma.

Shinto vs. Buddhism, Zen vs. the Allies, all those new religions… and that’s just Japan, which, unlike China, is not known for rebellions, wars with the hordes, and the Seven Kill Stele.

(Fun fact: the Taiping Rebellion, which started in 1850, killed about as many people as lived in the USA at the time.)

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_Chinese_wars_and_battles

But in that case, the entire society is the “non-trainspotting community”. If religious persons are the weirdoes and uncool kids, then the cool, normal, thing is to be the secular person who fits in with the predominant social culture. Things changed gradually and subtly; I have no idea about Sweden, but I’d be happy to venture that part of the reason for Japan’s change was to do with post-war social changes: the American occupation, for want of a better word, where emulation of Western society was perceived as the way forward, including losing or downplaying anything associated with the discredited old regime – see the insistence on removing the quasi-divine status of the Emperor, and the Directive abolishing Shintoism as the state religion.

Because the old military regime had used religion as part of ultra-nationalism, the occupying Western powers were quite determined to remove the threat of Japanese militarism (and to replace Japan with themselves as the major influence in the Asian sphere), which included stripping-out identification of the national religion with national identity, and make Japan into a model Western-style secular democracy (see today where it’s routine to refer to Israel as the only secular democracy in the Middle East).

Same thing happened in Western cultures, of course; look at British history and the Glorious Revolution and the identification of Protestantism (in the form of the State church: Anglicans only, no Dissenters or Non-Conformists need apply) with freedom, progress, and science which created the British Empire, height and summit of human history*

(*I may possibly be approaching this from an Irish angle which means a certain amount of disagreement with their self-assessment of Westminster as “Mother of Parliaments” and giving the rule of law and democracy to the world).

There was the Danka system, which surely counts as a state religion if ever there was one. Lasted about three centuries. The Shintoist movement under the Meiji Restoration was sort of a reaction against the Danka system, attempting to replace “foreign” Buddhism with “native” Shinto, but it never really worked. Nonetheless, if you add the two together you get a state religious system which was in place for about as long as Anglicanism has been official in England. More than you wanted to know here.

So in the “Nobody is Perfect, Everything is Commensurable” thread, someone said that the drive for holiness leads to self-mortification. Maybe that is another factor in this phenomenon.

It’s easy to ignore this as a flippant comparison, but David Foster Wallace (among many others, but I think he’s the writer I’d recommend on this subject) suggests that, as ritualistic people, all humans always have religion. Sometimes that religion is drug use. Sometimes that religion is competitive tennis. And there’s something to be said about religion, that simply being around has battle tested it enough to know it won’t totally ruin your life like tennis-as-religion will. I feel like this is a well understood idea generally, to the point of extreme paranoia that the above is accidentally plagiarized.

In our hearts, many of us feel this is the community and ritual that guides us. But defining rituals is incredibly hard to do right, maybe impossible to do deliberately. And I’m not sure ritualism meets my personal goals (which include agenty-ness). So the ritual itself might be cringe-worthy for reasons slightly more complex than if we asked people to wear mage costumes, for instance (which, I mean, it’s something we could ask of ourselves).

It sounds like this ties in to the reason-as-memetic-immune-disorder idea. Tennis as memetic immune disorder?

(Also, why the hell does my computer query the spelling of ‘memetic’? It’s a perfectly cromulent word)

Though I’m not sure I’d want to use the word ‘religion’ here. Perhaps ‘enthusiasms’? Most humans have enthusiasms (of which religions-in-the-traditional-sense are an important subset), but I’m not sure you can so easily say that the non-religion enthusiasms are less likely to take over your life. Most drug users are not addicts, and most amateur tennis players, as far as I can tell, enjoy that without it taking over their lives either. Can you be more specific about your threshold for ‘ruining your life’?

[Edited to add: my point is that people vary widely in the degree to which their enthusiasms take over their lives; some people are wired to take whatever they end up doing much more seriously than others, and I’m not sure that there is any significant weighting of the non-religious enthusiasms towards the take-things-very-seriously end of the spectrum]

Yeah, I think we are on the same page. I used those examples because those are some of the bigger examples in Infinite Jest, taken from different angles.

I’m not saying all drugs or all tennis is a religion that will ruin your life. I’m saying that there is a tendency for the human heart to fixate on one thing, the leading digit of our emotional preferential sort, if you will. When that’s tennis, when tennis is what your life is about, that will screw you up pretty hard. So will drugs, if they are the center of your personal attempt at meaning. Most things will. It’s not like tennis is super-evil (drugs are a tad more complex than tennis, but in a largely irrelevant way). It’s merely that if you select a random thing as the focus of your life, it will very likely destroy you.

That’s my concern with making up a new ritual, a new focus to satisfy that human impulse. Beauty, tennis, drugs, money, pleasure… we look at the world and see that these are bad choices. But no one is proposing a way to tell the ones that will ruin your life from the ones that won’t. Say what you will about Mormonism (and there is quite a lot to be said about how hard a sell that ritual must have been), but that is a ritual-set doesn’t ruin your life.

Other secular religions: rock n roll, stand up comedy.

Music for sure. Stand up? I want to go to that church.

The Pastrix of the House for All Sinners and Saints (Lutheran) says that stand-up is a prerequisite for becoming a preacher.

Not *funny* stand up. Jokes are optional in stand up, but youve got to have a cute back story about being half eskimo or something.

Liberalism seems like the classic example of a “secular religion” – see claims that Communists weren’t “really” atheists (on the theory that atheism and religion are mutually exclusive somehow.)

I think it’s possible that what we’re seeing here is liberalism converting the members of already liberal-influenced churches, rather than liberal-influenced churches inevitably dissolving into nothing in a why-our-kind-can’t-cooperate fashion.

The same almost certainly happens with conservatism, but it’s better at maintaining cover – see people talking about how the Constitution was “divinely inspired” and how Big Government is an agent of the Antichrist. Many conservative “Christian” groups are better understood as simply “conservative groups” that happen to use xian iconography.

>I think it’s possible that what we’re seeing here is liberalism converting the members of already liberal-influenced churches,

this is precisely what we’re seeing. there is a direct line of descent, both political and genetic, from puritans to patriots, abolitionists/unionists, social gospel/christian socialists, and finally to progressives. and Moldbug was hardly the first to point this out

It’s not so much that communists weren’t atheists, but that putting communists and atheists in the same category is rather like putting the US and NK in the same category of “demotic”.

For the “atheists have no morality” meme, I would then assume the proper interpretation of this belief is that religious people view atheists as religious people shirking their obligations. I would expect the secular Northern European countries have strong norms about obligations us Amerikaners don’t recognize as religious.

More simply, what they mean is that “atheists have no Divine Command meta-ethics”, which, well, they don’t. Religious people just play rhetorical games to pretend that Divine Command is the only viable meta-ethical position capable of yielding anything we could label “morality”.

Yes, that’s true. But I wouldn’t say it’s a rhetorical game, divine command theory is the only solid basis for robust moral realism. Unless you want to argue for the existence of a Platonic form of the good, but that’s not something people typically do.

In what sense does divine command constitute robust moral realism? It’s just another kind of subjectivism, with a specific choice of whose preferences matter.

Because God isn’t an arbitrarily selected human, or even an old man in the sky, but rather the ontological basis of reality, who created humanity with the telos of learning to follow his will. The theory makes perfect sense from a traditionalist perspective and none and all from a modern one, as explained by Scott.

I doubt there are any more people who understand divine command theory in the esoteric way you suggest than there are who accept something like a Platonic form of the good.

Why can’t objective morality be fixed by an ontological basic reality of a kind that is completely impersonal, in a way that is nothing like a command?

@Protagoras

That position is pretty standard theology, it’s basically my understanding of Aquinas and co. That said, most laymen don’t really get into theology, “God wants me to do X therefore I do x” is about as far as it goes. Which is perfectly adequate when it comes to actual practice.

@peterdjones

I suppose it could, Neoplatonists certainly thought so. I think CS Lewis had some objections to the idea but I can’t recall off the top of my head.

You may be right about Aquinas (some of his views seem completely incoherent to me, so I find it hard to comment on him), but he is hardly all theologians; plenty of theologians reject divine command theory (often for the reason I mentioned). And as you note, most religious believers aren’t theologians. I continue to think that there are more believers in something like Platonic moral forms than believers in the variant of divine command theory you mention. Far more numerous yet are the Kantians, who don’t seem to me to make any less sense or have any less solid a base for their moral realism than the Thomists (not that that’s saying much).

No theologians hold divine command theory. Many defend the naive divine command theory of the commoner as the truth seen through a glass.

This is from me, houseboatonstyx.

From Lewis’s Reflections on the Psalms, I think.

“There were in the eighteenth century terrible theologians who held that ‘God did not command certain things because they are right, but certain things are right because God commanded them.’ To make the position perfectly clear, one of them even said that though God has, as it happens, commanded us to love Him and one another, He might equally well have commanded us to hate Him and one another, and hatred would then have been right. It was apparently a mere toss-up which He decided on.”

(quoted secondhand)

@drunkenrabbit

“Because God isn’t an arbitrarily selected human, or even an old man in the sky, but rather the ontological basis of reality, who created humanity with the telos of learning to follow his will.”

That’s nonsense.

@Anonymous

“That said, most laymen don’t really get into theology, “God wants me to do X therefore I do x” is about as far as it goes. Which is perfectly adequate when it comes to actual practice.”

If someone doesn’t understand something, then it’s not their morality. If someone just follows what their priest tells them Divine Command theory says, then they aren’t following Divine Command, they’re following their priest, in which case they ARE following what some arbitrarily selected human says.

Heres the main thing I have with moral realism of any sort: I don’t see why I should care.

I don’t think the idea of an objectively correct preference makes any sense anyways, but lets give that and say that the “ontological basis of reality” “thinks” something is evil that I don’t have a problem with, or “thinks” something is good that I do have a problem with? Why should I care? That doesn’t change my preferences. I suppose that then makes me “evil”, but if so then I am evil and I am proud.

I suppose I might care in the same way I would care what Stalin thinks if I lived in Soviet Russia in 1950. But I wouldn’t care in the sense of it wanting to make me change my opinions.

“You should care” is just what moral realism means. If you don’t see why you should care you have not actually grasped the hypothetical of moral realism, you are just saying “given that moral realism is false, assuming moral realism is true doesn’t seem to make much sense”.

Philosophers talk about this problem as well — they ask whether morality is motivating. That is, if you believe that doing X is good, does that entail your being more likely to do X?

Compare this with other sorts of motivations and related beliefs. If you are hungry, and you believe that F is food, you are more likely to eat F than if you were unsure if it is food or not. Knowing that it is food entails being more likely to put it in your mouth when you want nourishment. The belief is linked — causally! — to action.

Some people report that they have moral beliefs that are not effectively motivating. “I know it would be good to tithe to charity, but I don’t do it because I am not that good.”

For me, thinking through things consequentially is a big part of the motivation to do things that people call “good”. It’s not that the act of sending a big check to Against Malaria Foundation has a “good” XML tag on it. It’s that I have a model of the world in which there are fewer little kids in Africa shivering in the throes of malaria if I donate than if I don’t.

I prefer the world with less malaria in it to the world with more malaria in it. And it seems that we have an effective way of achieving that result.

Since it doesn’t matter if I “am good” or not, the argument “I’m not that good, so I shan’t donate” doesn’t hold water. The only question is, “Given the world as it is … what do I prefer?”

And that’s a lot more motivating.

@suntzuanime

“you are just saying “given that moral realism is false, assuming moral realism is true doesn’t seem to make much sense”.”

No, II is saying that they don’t see how moral realism makes sense. Asserting that one does not understand the basis of a claim is not circular reasoning.

I believe in moral philosophy there are concepts called “motivational internalism” and “motivational externalism.” Motivational internalists hold that morality is intrinsically motivating, and that if you understand the ontological-universal-Platonic-morality you will be motivated to care. Externalists believe that moral knowledge is not intrinsically motivating, and that you need something extra, (such a a moral conscience) to motivate you to care.

I believe the reason there is so much confusion around this area is that a lot of Internalists have the same attitude that Divine Command Theorists do, they are so full of themselves that they identify their position with morality itself. A lot of Internatlists seem to believe that if motivational internalism is false, moral realism is false. So you often hear people make the argument that failure to be motivated by a moral argument is an argument against moral realism.

As you have probably figured out, I am a Motivational Externalist and think Motivational Internalism is stupid. My answer to the “Why should I care?” question is “If you have a conscience you already do, if you don’t you’re a sociopath and I hope we can incarcerate you before you hurt anyone.”

Sociopaths exist. There are people who know an action is wrong, and don’t care. That isn’t an argument against moral realism, that’s just an argument against Motivational Internalism.

That’s one form of motivational internalism, but not the only one. Another is that morality is constituted by whatever is internally motivating, and that the causal direction goes not from understanding morality to being motivated by it, but from having already existing motivations to constructing morality out of them.

And with good reason. If morality is what we ought to do, there should be some connection between that and what we find motivating, or at least would find motivating in an ideal rational state. Otherwise, we can rationally reject being moral, in which case the truth of morality is highly questionable.

“Why should I care?” is the most important question for morality, and if it’s to have a content that can provide an answer that’s not “You shouldn’t”, then it must follow from the agent’s motivational reasons. It’s not enough to say “You already care”, because different people care about different things to different degrees, and it’s misleading to label some subset of that as “caring” when it’s so different from person to person.

For the record, not a sociopath. I do have a “morality”, or utility function, or whatever you want to call it. I just see it as a personal preference rather than objective truth (note: this won’t stop me from trying to force it on others. People act on their preferences. Moral preferences are no different).

But if I found out that the universe itself has a different value system than I do (whatever the hell that would even mean), that would not cause me to switch value systems. I would still advocate and follow my preferences for the state of the universe. Thus the “then I would be evil and proud” thing.

Religious people also play rhetorical games pretending that Divine Command necessitates God.

So is Giving What We Can a lifetime commitment? This is something I could not determine by looking at their website, but it sounds like Scott is saying it is. I really like the idea of it, but giving 10% of my income for life is a very big commitment that I’m not sure I’m ready for.

Its for life or until you retire. The text is

Thanks. I will need to ponder on this, because in truth, that length of commitment makes me feel much less comfortable with the prospect. But… it shouldn’t, should it?

By the way, I read some of your blog posts, and they’re quite good; especially the one about your mother (my condolences). Incidentally, I happen to be in the Seattle area, but unfortunately I did not realize that there was a Secular Solstice meet up nearby. Perhaps in the future I can become involved in this community.

You might want to have a look at Try Giving. GWWC operate it for people who are interested in EA, but don’t feel ready/able to make a lifetime commitment to giving. See the bottom of this page: https://www.givingwhatwecan.org/get-involved/become-member

The real question is why you want a religion-substitute. Judging from this post, it seems like the main reason is to create a community. But what kind of community? “A group of people highly devoted to a set of teachings about the nature of the universe, morality, and how to live one’s life who meet up about once a week” already describes the LessWrong sphere. (In fact, I would argue that LessWrong already represents a fairly logical “religion for atheists”.)

One thing I always thought was nice about church is that once you’re married with kids it seems like a nice way to meet people and hang out with other families fairly regularly in a space where everyone feels at least a bit of pressure to be kind to each other. It seems to me like it’s hard to make and maintain friendships in middle-age, and church seems like it would be a good way to at the very least feel like part of a community. I could almost see myself at some point in my life going to church just for the companionship. It would be nice if there was a secular equivalent of such a thing. But I’m not sure how possible this is to create.

But in the end, that’s just the side benefits of religion. The real benefits are the internal (I accidentally typed “eternal” here, which is also fitting) ones – a sense of security, a sense of meaning in life, fears of death alleviated. Can an atheist religion provide that?

I guess the question is what do you imagine your atheist religious community looking like?

And also: if we’re going to have rules, what should they be?

I guess I have something of an answer to “what would the point of an atheist religion substitute be” since I am an atheist who has recently been feeling like I would really benefit from having something like church in my life.

I have been to maybe three church services in my life, so I’m not really qualified to talk about this, but in my understanding, what happens on Sunday in (good) churches is that people take time out of their day to work on being good people and on understanding how to live in the world. It’s a designated time and place for going to the meta-level and pondering how one might do better in the daily object-level tasks of life. It’s a way to get some grounding, to develop one’s sense of right and wrong and hopefully some inner strength.

So in a sense, one secular church-“equivalent” is therapy. (Which is also something I’d benefit from!) But there seem to be some important differences. Therapy is focused on your particular problems, which is great but potentially limiting. Therapy is kind of intense – it requires your active participation. You can’t just sit and listen and think like you might at a church service. And therapy (usually?) lacks the sort of sense of wonder and inspiration that I think (many?) churches strive for.

And yeah, church can provide community, and it’s a particular kind of community – it’s a community with people who share some core values and who have probably had some more or less profound experiences together. So in theory people in this community may be quite likely to get along better with each other than with people they meet in some other way.

So part of my wish to find a secular church-equivalent is that I feel like I would benefit from systematically taking time to think about life and morality in a directed way.

Another is that I sometimes, despite not believing in any god, have a strong desire to pray. Which is a really weird feeling. When I — give in to it, or imagine myself doing so? not sure which — I get a feeling of relief and comfort. I’ve decided I can kind of get around the dissonance by just letting some part of my brain be the “God module” – I can (sort of) pray to the construct that is my idea of “God”, and perhaps it begins to approach the kind of effect that people who believe in God achieve. It’s weird.

I’m not sure how or whether a secular church-equivalent would solve that. But that’s where I’d be most likely to meet some other people who have similar feelings. Maybe they have some some useful thoughts I might benefit from.

Also, importantly, therapy is expensive.

So is tithing, but I guess if you’re Giving Well, it’s a wash.

Therapy is also usually only between you and a therapist. If there is a group, it’s often anonymous, and you rarely meet outside of sessions. being able to talk about deeply personal and philosophical topics with people without worry of judgment is one of the things I miss most about my old youth group. Also, as GBM indicated above, something that draws me to the rationalist community, despite my current inability to attend meetups.

Just for weirdness’s sake, I nominate the Ten Pledges of the God Tet:

All bloodshed, war and pillaging is forbidden. (This includes any kind of violence or violation of rights, like physical injuries, rape or an Armor-Piercing Slap.)

All conflicts will be resolved through games.

Each party involved in a game must bet something that both sides agree is of equal value. (The wagers can also be non-material, so long as both side agree to it being equivalent.)

As long as it doesn’t go against Pledge 3, the things that are wagered and the rules of the game will not be questioned.

The challenged party has the right to decide the rules of the game. (This also includes the right to refrain from the game.)

Any bets made in accordance with the Oaths must be upheld.

Conflicts between groups will be conducted by designated representatives with absolute authority.

Being caught cheating during a game is grounds for an instant loss.

In the name of God, the previous rules may never be changed.

Everyone must have fun playing together!

Ooh, I like that.

My friends and I tried a few times to play this game Morton’s List, where basically you roll a die a few times and it tells you what your activity for the day is. You’re supposed to perform a ritual of sorts before you play so that the game is more binding – i.e. people don’t say “that’s too hard” or “let’s do something else” or “can we roll again” or “that doesn’t sound like fun” or whatever. However in reality, this is almost always what happens, and the group ends up sitting around bored just like they were before.

I think if you’re going to have arbitrary binding rules that everyone has to follow, a great way to use them would be in the interest of fun. Solve the co-ordination problem of “everyone is sitting around bored as hell but no one wants to put in the effort to get something started”.

That works out a lot better when it’s actually enforced by omnipotent divine power instead of being something you’re asking people to unilaterally abide by.

That’s something I always liked about Tet; he doesn’t passive-aggressively tell people what to do to give them a chance to disobey him so he has an excuse to subject them to torments, he just enforces the conduct that he wants from people with his own power. Seems a lot more honest.

What happens when Pledge 2 (“all conflicts will be resolved through games”) and Pledge 5 (“the challenged party has the right…to refrain from the game”) conflict?

Is pledge 2 a “must” – the only method of conflict resolution is through games, so if you want your conflict resolved you have to play – or a “one selection out of several” – if you refuse to play, you can go to law or have the oldest granny in the village make the decision or see what square the sacred chickens peck the grain from?

And if the challenged party can refrain from the game, does that mean they can continue on with their behaviour until or unless the conflict is resolved, e.g. Ig challenges Uz because he says Uz is stealing his gooseberries from his bushes when they ripen; Uz refuses to play the game Ig selects; stalemate and so Uz keeps robbing the gooseberries, making jam, and selling it at the farmers’ market for a tidy profit?

I believe that gameplaying was only meant to replace physical conflict, changing the final argument of kings from war to chess. Arguing about the proper outcome in court is fine, except that when the officers of the court come to enforce their judgment against you and you resist, they’ll use a deck of cards instead of a club.

I believe seeing what square the sacred chickens pick the grain from would be considered a game of chance, so it would be available by mutual agreement.

I don’t recall the right to refrain from playing a game being in the rules when I read them and it does seem to defeat the original purpose of replacing all violent conflict. I think that may have been an error? You could maybe make it work with some really sketchy divinely-enforced property rights, but I think the system only works if you can force people to acknowledge the game system. Otherwise it isn’t any more of a final argument of kings than just arguing is.

Mmm – well, I’m hopeless at cards, so if I’m in Ig’s position, I’m screwed. All Uz has to do, as challenged party, is go “Excellent! Let us settle this dispute with a hand of poker! Or 45! Or Snap?”

He gets all my gooseberries and becomes a jam magnate and I’m toast.

The right to refuse challenges was there, it’s the main flaw of the system. But then Tet is around to cause ripples whenever the war gets too cold for his tastes.

Remember how at the end, when they wanted to challenge the beastmen, they had to tip their hand, hint that they know about their cheating game, bet many times more compared to what the beastmen were betting, and still play the beastmen’s game where they knew they would be cheated, just because otherwise the beastmen won’t accept?

I just remember there were bandits in the first episode, and it seems like banditry is pretty hard in a world where all force is voluntary.