I.

Julian Jaynes’ The Origin Of Consciousness In The Breakdown Of The Bicameral Mind is a brilliant book, with only two minor flaws. First, that it purports to explains the origin of consciousness. And second, that it posits a breakdown of the bicameral mind. I think it’s possible to route around these flaws while keeping the thesis otherwise intact. So I’m going to start by reviewing a slightly different book, the one Jaynes should have written. Then I’ll talk about the more dubious one he actually wrote.

My hypothetical Jaynes 2.0 is a book about theory-of-mind. Theory-of-mind is our intuitive model of how the mind works. It has no relation to intellectual theories about how the mind is made of cognitive algorithms or instantiated on neurons in the brain. Every schoolchild has a theory-of-mind. It usually goes like this: the mind is an imaginary space containing things like thoughts, emotions, and desires. I have mine and you have yours. I can see what’s inside my mind, but not what’s inside your mind, and vice versa. I mostly choose the things that are in my mind at any given time: I will thoughts to happen, and they happen; I will myself to make a decision, and it gets made. This needs a resource called willpower; if I don’t have enough willpower, sometimes the things that happen in my mind aren’t the ones I want. When important things happen, sometimes my mind gets strong emotions; this is natural, but I need to use lots of willpower to make sure I don’t get overwhelmed by them and make bad decisions.

All this seems so obvious to most people that it sounds like common sense rather than theory. It isn’t; it has to be learned. Very young children don’t start out with theory of mind. They can’t separate themselves from their emotions; it’s not natural for them to say “I’m really angry now, but that’s just a thing I’m feeling, I don’t actually hate you”. It’s not even clear to them that people’s minds contain different things; children are famously unable to figure out that a playmate who has different evidence than they do may draw different conclusions.

And the learning isn’t just a process of passively sitting back observing your own mind until you figure out how it works. You learn it from your parents. Parents are always telling their kids that “I think this” and “What do you think?” and “You look sad” and “It makes me feel sad when you do that”. Eventually it all sinks in. Kids learn their parent’s theory-of-mind the same way they learn their parents’ language or religion.

When in human history did theory-of-mind first arise? It couldn’t have been a single invention – more like a gradual process of refinement. “The unconscious” only really entered our theory-of-mind with Freud. Statements like “my abuse gave me a lot of baggage that I’m still working through” involves a theory-of-mind that would have been incomprehensible a few centuries ago. It’s like “I’m clicking on an icon with my mouse” – every individual word would have made sense, but the gestalt would be nonsensical.

Still, everyone always assumes that the absolute basics – mind as a metaphorical space containing beliefs and emotions, people having thoughts and making decisions – must go back so far that their origins are lost in the mists of time, attributable only to nameless ape-men.

Julian Jaynes doesn’t think that. He thinks it comes from the Bronze Age Near East, c. 1500 – 750 BC.

II.

Jaynes (writing in the 1970s) was both a psychology professor at Princeton and an expert in ancient languages, so the perfect person to make this case. He reviews various samples of Bronze Age writing from before and after this period, and shows that the early writings have no references to mental processes, and the later ones do. When early writings do have references to mental processes, they occur in parts agreed by scholars to be later interpolations. If, with no knowledge of the language itself, you tried to figure out which parts of a heavily-redacted ancient text were early vs. late by their level of reference to mental processes, you could do a pretty decent job.

I don’t speak fluent Sumerian, so I am forced to take Jaynes’ word for a lot of this. It’s even worse than that, because Jaynes argues that other translators sometimes err and translate non-mental terms in mental ways. This is an easy mistake for them to make, because most cultures, once they got theory of mind, repurposed existing language to represent it. Jaynes makes a convincing case for why this would happen, and convincingly argues for why his interpretations are truer to the spirit of the text, but it does mean you can’t double-check his work by reading the works in translation.

Jaynes spends the most time talking about the Iliad, with good reason – it’s the longest Bronze Age work we have, and in many ways it’s a psychodrama, focusing as much on the characters of Achilles, Hector, etc as the plot itself. It came together piecemeal through the efforts of Greek bards between about 1100 and 800 BC, finally reaching a canonical version in the mouth of “Homer” around 700 BC – the period Jaynes says theory of mind was starting to evolve. Jaynes uses it to trace the development process, showing how older sections of the Iliad treat psychology in different ways than newer ones.

So for example, a typical translation might use a phrase like “Fear filled Agamemnon’s mind”. Wrong! There is no word for “mind” in the Iliad, except maybe in the very newest interpolations. The words are things like kardia, noos, phrenes, and thumos, which Jaynes translates as heart, vision/perception, belly, and sympathetic nervous system, respectively. He might translate the sentence about Agamemnon to say something like “Quivering rose in Agamemnon’s belly”. It still means the same thing – Agamemnon is afraid – but it’s how you would talk about it if you didn’t have an idea of “the mind” as the place where mental things happened – you would just notice your belly was quivering more. Later, when the Greeks got theory of mind, they repurposed all these terms. You can still find signs of this today, like how we say “I believe it in my heart”. In fact, you can still find this split use of phrenes, which has survived into English both as the phrenic nerve (a nerve in the belly) and schizophrenia (a mental disease). As the transition wore on, people got more and more flowery about the kind of feelings you could have in your belly or your heart or whatever, until finally belly, heart, and all the others merged into a single Mind where all the mental stuff happened together.

The Iliad uses these body parts to describe feelings despite its weak theory of mind. Its solution for describing thoughts and decision-making is more…unconventional.

Suppose Achilles is overcome with rage and wants to kill Agamemnon. But this would be a terrible [idea]; after [thinking] about it for a while, he [decides] against. If Achilles has no concept of any of the bracketed words, nothing even slightly corresponding to those terms, how does he conceptualize his own actions? Jaynes:

The response of Achilles begins in his etor, or what I suggest is a cramp in his guts, where he is in conflict, or put into two parts (mermerizo) whether to obey his thumos, the immediate internal sensations of anger, and kill the king, or not. It is only after this vacillating interval of increasing belly sensations and surges of blood, as Achilles is drawing his mighty sword, that the stress has become sufficient to hallucinate the dreadfully gleaming goddess Athene who then takes over control of the action and tells Achilles what to do.

Wait, what?

III.

As you go about your day, you hear a voice that tells you what to do, praises you for your successes, criticizes you for your failures, and tells you what decisions to make in difficult situations. Modern theory-of-mind tells you that this is your own voice, thinking thoughts. It says this so consistently and convincingly that we never stop to question whether it might be anything else.

If you don’t have theory of mind, what do you do with it? Children don’t have theory of mind, at least not very much of it, and more than half of them have imaginary friends. Jaynes has done some research on the imaginary friend phenomenon, and argues that a better term would be “hallucinatory friend” – children see and hear these entities vividly. The atheoretical mind is a desperate thing, and will comply with any priors you give it to make sense of its experiences. If that prior is that the voice in your head is a friend – or god – it will obediently hallucinate a friend or god for you, and modulate its voice-having accordingly.

I know some very smart and otherwise completely sane evangelical Christians who swear to me that God answers their prayers. They will ask God a question, and they will hear God’s voice answer it. God’s voice may not sound exactly like an external voice, and it may give them only the advice they would have given themselves if they’d thought about it – but they swear that they are not thinking about it, that their experience is qualitatively different than that. And these are normal people! If you’re a special person – a saint or mystic, say – and you actively court the experience by fasting and praying and generally stressing your body to the limit – then the voice will be that much louder and more convincing.

There are even whole forms of therapy based on this kind of thing. In Internal Family Systems, the therapist asks the patient to conceptualize some part of their mind (maybe the part that’s producing a certain symptom) as a person, and to talk to it. I know people who swear that this works. They approach their grief or anger or anxiety, and they get a clear image of what “he” or “she” looks like, and then “he” or “she” talks to them. Usually he/she tells them some appropriately psychological sounding thing, like “Hello, I am your anxiety, and I’m only inflicting these fears on you because we were abused as a child and I want to make sure nobody ever abuses us like that again”. Then the patient talks to their anxiety and hopefully strikes a bargain where the patient agrees to take the anxiety’s perspective into account and the anxiety agrees not to make the patient so anxious all the time. Some people swear by this, say it’s helped them where nothing else can, and absolutely insist they are having a real dialogue with their anxiety and not just making up both sides of the conversation.

Most of the people who seem to really like IFS have borderline personality disorder. And borderline people are also at the most risk of dissociative identity disorder (multiple personality). Multiple personality has two main risk factors: borderline, and somebody suggesting to you that multiple personality disorder might be a reasonable thing to have. For a while in the 80s, psychiatrists were really into multiple personality and tried diagnosing everyone with it, and sure enough all those people would admit to having multiple personalities and it would be very exciting. Then the APA told the psychiatrists to stop, people stopped talking about multiple personality as much, and now the condition is rarer.

A few years ago, someone rediscovered/invented tulpamancy, the idea of cultivating multiple personalities on purpose because it’s cool. People who try to do this usually succeed. At least they say they’ve succeeded, and I believe they think this. I think their internal experience is of talking to a different entity inside of them. Also, I have a friend who writes novels, and one time she created such a detailed mental model of one of her characters that it became an alternate personality, which she still has and considers an important part of her life. She is one of the most practical people I know and not usually prone to flights of fancy.

I also have less practical friends, friends who are into occultism. They tell me they sometimes make contact with spiritual entities. I believe them when they say they have these experiences. I believe them when they say that they were not purposely guiding their Ouija board to say whatever it said. I don’t have any friends who are cool enough to have gone through the whole procedure for summoning your Holy Guardian Angel, but from what I read, completing the ritual directly does tend to leave you with an angel who hangs around you and gives you advice. I believe the people who say this is their experience of completing the ritual.

I conclude that giving yourself multiple personalities is actually pretty easy under the right circumstances. Those circumstance are a poor theory of mind (I think borderlines are naturally bad at this) and a cultural context in which having a multiple personality is expected.

Jaynes says ancient people met both criteria. They had absolutely no theory of mind, less theory of mind than the tiniest child does today. And their cultural context was absolutely certain that gods existed. Just as we teach our children that the voice in their mind is them thinking to theirselves, so the ancients would teach their children that the voice in their head was a god giving them commands. And the voice would dutifully mold itself to fit the expected role.

Here Jaynes is at his most brilliant, going through ancient texts one by one, noting the total lack of mental imagery, and highlighting the many everyday examples of conversations with gods. Every ancient culture has near-identical concepts of a god who sits inside of you and tells you what to do. The Greeks have their daemons, the Romans their genii, the Egyptians their ka and ba, and the Mesopotamians their iri. The later you go, the more metaphorically people treat these. The earlier you go, the more literal they become. Go early enough, and you find things like the Egyptian Dispute Between A Man And His Ba which is just a papyrus scroll about a guy arguing loudly with the hallucinatory voice of his guardian spirit, and the guardian spirit’s hallucinatory voice arguing back, and nobody thinking any of this is weird (people who aren’t Jaynes would wimp out and say this is “metaphorical”). Every ancient text is in complete agreement that everyone in society heard the gods’ voices very often and usually based decisions off of them. Jaynes is just the only guy who takes this seriously.

Turn on what Terry Pratchett called “first sight and second thoughts” and try to look at the Bronze Age with fresh eyes. It was really weird. People would center their city around a giant ziggurat, the “House of God”, with a giant idol within. They would treat this idol exactly like a living human – feeding it daily, washing it daily, sometimes even marching it through the streets on sedan chairs carried by teams of slaves so it could go on a “connubial visit” to the temple of an idol of the opposite sex! When the king died, hundreds of thousands of men would labor to build him a giant tomb, and then they would kill a bunch of people to serve him in the afterlife. Then every so often it would all fall apart and everyone would slink away into the hills, trying to pretend they didn’t spend the last twenty years buliding a jeweled obelisk so some guy named Ningal-Iddida could boast about how many slaves he had.

If the Bronze Age seems kind of hive-mind-y, Julian Jaynes argues this is because its inhabitants weren’t quite individuals, at least not the way we think of individuality. They were in the same kind of trance as a schizophrenic listening to voices commanding him to burn down the hospital. All of it – the ziggurats, the obelisks, the pyramids – were an attempt to capture not individual humans, but those humans’ daemons – to get people to identify the voice in their head with the local deity, and replace their free will with a hallucinatory god who represented their mental model of society’s demands on them. In the best case scenario, the voice would be interpreted as the god-king himself, giving you orders from miles away. Jaynes argues the Bronze Age was obsessed with burials and the afterlife (eg the Pyramids) because if you had internalized the voice in your head as Pharaoh Cheops, the voice wasn’t going to go away just because the actual Pharaoh Cheops had died hundreds of miles away in the capital. So even after Pharaoh Cheops dies, as far as all his subjects can tell, he’s still around, commanding them from the afterlife. So they had better keep him really, really happy, just as they did during life. Jaynes presents various pieces of evidence that the main function of pyramids was as a place where you could go to commune with the dead Pharaoh’s spirit – ie ask it questions and it would answer them.

He has a similar explanation for idols. The Bronze Age loved idols. There were the giant idols, ones that made the statue of Zeus at Olympia look like a weak effort. But also, every family had their own individual idols. Archaeologists who dig up Bronze Age houses just find idol after idol after idol, like the ancient Sumerians did nothing except stare at idols all day. Jaynes thinks this is approximately true. Idols were either cues to precipitate hallucinatory voices, or else just there to make conversation more comfortable – it’s less creepy if you can see the person you’re talking to, after all.

Then, around 1250 BC, this well-oiled system started to break down. Jaynes blames trade. Traders were always going into other countries, with different gods. These new countries would be confusing, and the traders’ hallucinatory voices wouldn’t always know all the answers. And then they would have to negotiate with rival merchants! Here theory of mind becomes a huge advantage – you need to be able to model what your rival is thinking in order to get the best deal from him. And your rival also wants theory of mind, so he can figure out how to deceive you. Around 1250 BC, trade started picking up, and these considerations became a much bigger deal. Then around 1200 BC, the Bronze Age collapsed. It’s still not exactly clear why (some of you may have heard me give a presentation on this), though most guesses involve a combination of climate change plus the mysterious Sea Peoples. Whole empires were destroyed, their populations become refugees who flooded the next empire in turn. Now everyone was in unfamiliar territory; nobody had all the answers. The weird habits of mind a couple of traders had picked up became vital; people adopted them or died.

But as theory of mind spread, the voices of the gods faded. They receded from constant companions, to only appearing in times of stress (the most important decisions) to never appearing at all. Jaynes interprets basically everything that happened between about 1000 BC and 700 BC as increasingly frantic attempts to bring the gods back or deal with a godless world.

Now, to be fair, he cites approximately one zillion pieces of literature from this age with the theme “the gods have forsaken us” and “what the hell just happened, why aren’t there gods anymore?” As usual, everyone else wimps out and interprets these metaphorically – claiming that this was just a poetic way for the Mesopotamians to express how unlucky they felt during this chaotic time. Jaynes does not think this was a metaphor – for one thing, people have been unlucky forever, but the 1000 – 750 BC period was a kind of macabre golden age for “the gods have forsaken us” literature. And sometimes it seems oddly, well, on point:

My god has forsaken me and disappeared

My goddess has failed me and keeps at a distance

The good angel who walked beside me has departed.

Or:

One who has no god, as he walks along the street

Headache envelops him like a garment

Jaynes says that “there is no trace whatsoever of any such concerns in any literature previous to the texts I am describing here”.

So people got desperate. He says this period was the origin of augury and divination. Omens “were probably present in a trivial way” before this period, but not very important; “there are, for example, no Sumerian omen texts whatsoever”. But after about 1000 BC, omens become an international obsession.

Towards the end of the second millennium BC…such omen texts proliferate everywhere and swell out to touch almost every aspect of life imaginable. By the first millennium BC, huge collections of them are made. In the library of King Ashurbanipal at Nineveh about 650 BC, at least 30% of the twenty to thirty thousand tablets come into the category of omen literature. Each entry in these tedious irrational collections consists of an if-clause or protasis followed by a then-clause or apodosis. And there were many classes of omens…

– If a town is set on a hill, it will not be good for the dweller within that town.

– If black ants are seen on the foundations which have been laid, that house will get built; the owner of that house will live to grow old.

– If a horse enters a man’s house, and bites either an ass or a man, the owner of the house will die, and his household will be scattered.

– If a fox runs into the public square, that town will be devastated.

– If a man unwittingly treads on a lizard and kills it, he will prevail over his adversary.

And then there are the demons. Early Sumerians didn’t really worry about demons. Their religion was very clear that the gods were in charge and demons were impotent. Post 1000 BC, all of this changes.

As the gods recede…there whooshes into this power vacuum a belief in demons. The very air of Mesopotamia became darkened with them. Natural phenomena took on their characteristics of hostility toward men, a raging demon in the sandstorm sweeping the desert, a demon of fire, scorpion-men guarding the rising sun beyond the mountains, Pazuzu the monstrous wind demon, the evil Croucher, plague demons, and the horrible Asapper demons that could be warded off by dogs. Demons stood ready to seize a man or woman in lonely places, while sleeping or eating or drinking, or particularly at childbirth. They attached themselves to men as all the illnesses of mankind. Even the gods could be attacked by demons, and this sometimes explained their absence from the control of human affairs…

Innumerable rituals were devoutly mumbled and mimed all over Mesopotamia throughout the first millennium B.C. to counteract these malign forces. The higher gods were beseeched to intercede. All illnesses, aches, and pains were ascribed to malevolent demons until medicine became exorcism. Most of our knowledge of these antidemoniac practices and their extent comes from the huge collection made about 630 B.C. by Ashurbanipal at Nineveh. Literally thousands of extant tablets from this library describe such exorcisms, and thousands more list omen after omen, depicting a decaying civilization as black with demons as a piece of rotting meat with flies.

…and angels, and prophets, and all the other trappings of religion. When the gods spoke to you every day, and you couldn’t get rid of them even if you wanted to, angels – a sort of intermediary with the gods – were unnecessary. There was no place for prophets – when everyone is a prophet, nobody is. There wasn’t even prayer, at least not in a mystical sense – as Jaynes puts it, “schizophrenics do not beg to hear their voices – it is unnecessary – in the few case where this does happen, it is during recovery when the voices are no longer heard with the same frequency.”

The Assyrians invented the idea of Heaven. Previously, Heaven had been unnecessary. You could go visit your god in the local ziggurat, talk to him, ask him for advice. But word went around that gods had retreated to heaven – some of the stories even use those exact words, blaming the Great Flood or some other cataclysm. The ziggurats shifted from houses for the gods to e-temen-an-ki – pedestals that the gods could descend to from Heaven, should they ever wish to return.

By 500 BC, the ability to hear the gods was limited to a few prophets, oracles, and poets. Jaynes is especially interested in this last group – he cites various ancient sources claiming that the poets only transcribe what they hear gods and goddesses sing to them (everyone else wimps out and says this is metaphorical). For Jaynes, the Iliad starts “Sing, O Muse…” because the poet was expecting a hallucinatory Muse to actually appear beside him and start singing, after which he would repeat the song to his listeners as a sort of echolalia.

Jaynes ends by referencing one of my favorite ancient texts, Plutarch’s On The Failure Of Oracles. Plutarch, writing around 100 AD, is not a skeptic. He believes oracles work in theory. But he records a general consensus that they don’t work as well as they used to, and that some day soon they will stop working at all. Jaynes believes that as the theory-of-mind waterline rises, fewer and fewer people hear the voices of the gods. By the Golden Age of Greece, it was so difficult that only a few specially selected people placed in specially numinous locations could manage – the oracles. By Plutarch’s own time, even those people could barely manage.

The last oracle to fade away was the greatest – Delphi, perched atop a fantastic gorge as if suspended between Heaven and Earth. Jaynes tries to give us an impression of how important it was in its time; important people from all over the classical world would make the pilgrimage there, leave lavish gifts, and ask Apollo for advice on weighty matters. He thinks that the oracle’s fame protected it; if a cultural validation is an important ingredient in god-hearing, Delphi had the strongest and best. Its reputation was unimpeachable. Still, in the centuries after Plutarch, its prophecies became rarer and rarer; the Pythia’s few divine utterances became separated by more and more incoherent raving. Finally:

As part of [the Emperor Julian’s] personal quest for authorization, he tried to rehabiliate Delphi in AD 363, three years after it had been ransacked by Constantine. Through his remaining priestess, Apollo prophecied that he would never prophesy again. And the prophecy came true.

IV.

The real Origin Of Consciousness In The Breakdown Of The Bicameral Mind is like my edited version above, except that wherever I say “theory of mind”, it says “consciousness”.

Jaynes has obviously thought a lot about this, and he’s a psychology professor so I’m sure he’s heard of theory of mind. Still, I am so against this choice. Consciousness means so many different things to so many different people, and none of them realize they’re talking past each other, and it’s such a loaded term that any argument including it is basically guaranteed to veer off into the fantastic.

Did he literally believe that the Sumerians, Homeric Greeks, etc were p-zombies? That there was nothing that it was like to be them? That they took in photons and emitted actions but experienced no “mysterious redness of red”? I cannot be completely sure. At times he refers to Bronze Age people as “automatons”, which seems like a pretty final judgment. But he also treats them as genuinely hearing, seeing, and having feelings about the hallucinatory gods who appear to them. The god-human interaction seems like it involves the human being at least minimally conscious. But if Jaynes has a coherent theory here, I must have missed it.

I think he is unaware of (or avoiding) what we would call “the hard problem of consciousness”, and focusing on consciousness entirely as a sort of “global workspace” where many parts of the mind come together and have access to one another. In his theory, that didn’t happen – the mental processing happened and announced itself to the human listener as a divine voice, without the human being aware of the intermediate steps. I can see how “consciousness” is one possible term for this area, if you didn’t mind confusing a lot of people. But seriously, just say “theory of mind”.

Jaynes seems aware of this objection, which he summarizes as “the Bronze Agers did not lack consciousness, they just lacked the concept of consciousness”. His retort is that in some cases, the concept of a thing is the same as the thing itself – he suggests baseball as an example. This seems a little sophistic to me. If somebody told me that Mandarin Chinese doesn’t have a word for “consciousness”, I would be surprised but not stunned – it seems like a strange word for a rich and ancient language to lack, but weirder things have happened. If somebody told me that Chinese people didn’t even have the concept of consciousness until it was introduced from the West, that wouldn’t shock me either – sometimes I think half of philosophers don’t even have the same concept of consciousness I do, and I can imagine the Chinese carving up the world in very different ways. But if someone told me that Chinese people were not conscious, I would dismiss them as a crank. So I can’t accept that having consciousness and having a concept of consciousness are exactly the same thing, and I continue to think “theory of mind” is better here.

The other major difference between my rewrite and Jaynes’ real book is that Jaynes focuses heavily on “bicamerality” – the division of the brain into two hemispheres. He believes that in the Bronze Age mind design, the left hemisphere was the “mortal” and the right hemisphere the “god” – ie the hallucinatory voice of the god was the right hemisphere communicating information to the left hemisphere. In the modern mind design, the two hemispheres are either better integrated, or the right hemisphere just doesn’t do much.

I am not an expert in functional neuroanatomy, but my impression is that recent research has not been kind to any theories too reliant on hemispheric lateralization. While there are a few well-studied examples (language is almost always on the left) and a few vague tendencies (the right brain sort of seems to be more holistic, sometimes), basically all tasks require some input from both sides, there’s little sign that anybody is neurologically more “right-brained” or “left-brained” than anyone else, and most neuroscientific theories don’t care that much about the right-brain left-brain distinction. Also, Michael Gazzaniga’s groundbreaking work on split-brain patients which got everyone excited about hemispheres and is one of the cornerstones of Jaynes’ theory doesn’t replicate. Also, Jaynes says his theory implies that schizophrenic hallucinations come from the language centers of the right hemisphere, and I think the latest fMRI evidence is that they don’t.

(Also, Jaynes says his theory implies that demonic possession occurs in the right hemisphere. But some absolute madman actually put a possessed women in an fMRI machine and then exorcised her while the machine was running and although it showed some odd deficiencies in interhemispheric communication, it didn’t seem to show unusual right hemisphere activity. Imagine having to write that IRB application!)

I don’t think either of these issues fundamentally changes Jaynes’ theory. Just switch “consciousness” to “theory of mind”, and change the psychiatry metaphor from split-brain patients to dissociative-identity patients, and you’re fine.

V.

But there’s another class of problem that Jaynes’ theory doesn’t survive nearly as well: what about Australian Aborigines?

Or American Indians, or Zulus, or Greenland Inuit, or Polynesians, or any other human group presumably isolated from second-millennium-BC Assyrians until anthropologists got a chance to examine them? If consciousness is an invention, and it didn’t spread to these groups, did these groups have it? If so, how? If not, why aren’t they hallucinating gods all the time?

I mean, some of these groups definitely have shamans and medicine men. I’m not saying none of them ever hear gods. But Jaynes claims Bronze Agers heard gods literally all the time, as a substitute for individual thought. Nothing I’ve heard from these people or the anthropologists who study them suggest anything like this is true. And these people also seem to be able to strategically deceive others, another key consciousness innovation Jaynes says Bronze Agers lacked. Or at least I assume I would have heard about it from some anthropologist if they weren’t.

I don’t have a good sense of how Jaynes would answer this objection. The most relevant part of the book is around page 135. Jaynes argues that bicamerality (his term for the hallucinatory gods) started with agriculture in the Bronze Age Near East, though there were scattered hallucinations before then. So plausibly the Inuit, aborigines, etc, were not bicameral. They are in a pre-bicameral state, where they have neither full subjective consciousness, nor clear hallucinations of gods. They may have flashes of both, or do something else entirely, or just be blank. Or something. The point is, if they were perfectly normal conscious people like us, then Jaynes is wrong about everything.

Maybe I’ve done some violence to Jaynes’ theory by rounding it off to “theory of mind” and emphasizing it as an invented technology? But he tries to really emphasize the inventedness of it in the first few chapters, talking about how it had to be built up by layer upon layer of well-chosen metaphor. As far as I can tell I relayed that part faithfully.

And I’m looking at the bulletin board on julianjaynes.org, and there’s a post by someone who met Jaynes before he died and asked him this question. They write:

On the About Julian Jaynes page it says he gave a lecture at the Wittgenstein Symposium in [Kirchberg]. I was there. It was a wonderful lecture. It is a pity that his work has not had a deeper impact. I still believe he was basically right (and certainly his prose was brilliant).

I did ask him, by the way, whether he thought it possible that the Aborigines in Australia were not conscious as late as the 18th or 19th century. He said he was not sure and that it would be worthwhile to investigate. Well, I never did and probably no one else [did].

So I don’t think I am misunderstanding him by making this criticism, and it sounds like he just bites the bullet and says maybe this was true. The main position on the forum seems to be that anthropologists weren’t asking the right questions as soon as they met uncontacted tribes, and so maybe they would have missed this. I find this hard to believe. It should be really easy to notice, and also the process of them learning Western theory of mind should leave some scars – at least one of them should say something like “that couple-year period when we all stopped hallucinating gods and became conscious – that was a weird time.”

Jaynes partisans are able to come up with a few anthropological works suggesting that the minds of primitive people are pretty weird, and I believe that, but they don’t seem quite as weird as Jaynes wants them to be. So the question becomes whether we would notice if some people worked in a pre-bicameral and pre-conscious way.

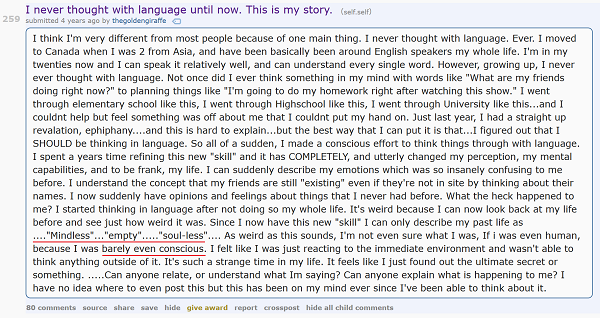

I’m tempted to answer “yes, obviously”, but for the counterargument, see this Reddit thread.

This guy thinks he “barely” had consciousness (in the Jaynesian sense), and it took him however many years to notice this about himself. It was just another universal human experience you can miss without realizing it! And notice how it was the culturally learned knowledge that other people worked differently which shifted him to the normal equilibrium. So maybe if there was some tribe like this somewhere, it would be easy to miss.

I’m also thinking of some cross-cultural psychiatry classes I had to take in residency. It’s well-known that some other cultures rarely get depression and anxiety in the classical Western sense. Instead, in the situations where we would become depressed and anxious, they get psychosomatic complaints, especially stomach pain. This happens to Westerners too sometimes, but in other cultures (eg China, Latin America) it’s by far the most common presentation. This seems similar to Jaynes’ argument that the ancient Greeks talked about feelings in their stomachs when we would talk about thoughts in our minds. I’m not saying these people aren’t conscious or have no theory of mind. But it seems like their theory of mind must be…arranged…differently than ours is, somehow. Or that cultural expectations about how these issues express themselves are shaping the way these issues express themselves, powerfully enough that you can just have whole cultures where depression the way we experience it isn’t a thing. See also this list of culture-bound syndromes. Make sure to read the discussion of Western culture-bound syndromes on the bottom – and make sure to spend a few moments considering what a politically-incorrect person might add to the list.

Even if I don’t accept all the stuff about hallucinatory Athena choreographing the Trojan War, the most important thing I’m going to take away from Origin of Consciousness is that theory of mind is an artifact, not a given, and it’s not necessarily the same everywhere. Much of the way we relate to our mind is culturally determined, and with a different enough cultural environment you can get some weird mind designs in ways that have real effect on behavior. Theory-of-mind-space is wider than we imagine, whether we’re thinking about ancient Sumerians or our ordinary-seeming neighbors.

If theory of mind became widespread because of trade and having to think about the decision-making of your counterparties, then for theory of mind to have been uncommon before, people would have to have been really bad at wars, (strategy) games, and any sort of negotiating. Were there no wars, (strategy) games, or negotiating before, or were people shockingly bad at it? This seems unlikely.

If everyone was worse at a competitive skill, how could we tell? Maybe if there was a detailed and accurate description of a situation and how someone responded, then we could tell whether they missed a low-hanging fruit in their decision space.

Except that there would be a competitive advantage to whomever was the first to develop modern theory of mind, which seems to raise the question: “Why didn’t it happen until the development of long-range trade? Why weren’t previous wars, negotiations, and other social interactions enough to spark the same process?”

Just a random guess. In context vs out of context failures.

Their gods were stronger today is an in context failure. Loosing a war makes sense to a bronze age guy because his gods can be beaten by other gods.

Not knowing that another merchant thinks it’s offensive to negociate without breaking bread is an out of context problem. Why would the god of trade not know that?

This makes sense. In addition, modeling a trader with different traditions is a harder problem than modeling a general. There are a lot of constraints on military, because it revolves around using a few types of weapons to kill the opponent and stay alive. An archer is an archer, regardless of the army, and will be used in certain ways. A general can work by assuming his opponent is identical to him.

A merchant can’t work by assuming that other merchants are identical to him. If salt is salt and of equal value, why trade? The merchant must realize that the seaside community that produces salt or the town with salt mines will value salt less. In addition there are unexplained values like many cultures (but not all) really liking cowrie shells.

I also am under the impression that merchant was a low-class occupation treated with distrust/disgust kind of all through antiquity until the modern day.

@Furslid

But trading, including long distance trading that took advantage of ‘arbitrage’ between locations where goods had locally different values, was common waaaay before 1000 or 1250 BC. The ancient Mesopotamians were trading with the Indus Valley civilizations something like 1500 years before that time, for instance:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Indus%E2%80%93Mesopotamia_relations

And trade between seaside towns for salt and inland towns for whatever? Yeah, that’s probably been going on since the Neolithic.

The timing doesn’t line up if it’s as simple as “merchants need to be able to understand the mindset of other merchants who grew up with different customs.”

@Ttar

“Merchants were disrespected” maybe compared to whoever the ruling elite of a given society was (e.g. landed aristocracy in feudal Europe), sure. But they tended to have status that put them comfortably above that of the average peasant, and “money talked” even then.

I don’t think the hypothesis has enough explanatory power to explain “there is an entire category of psychological ‘software’ that human beings never bothered to develop until Bronze Age merchants needed it some time in the late part of the second millenium BC.”

…

Especially when the alternative is that it was simply the language of the Bronze Agers that had culturally learned ways to describe psychological mechanisms similar to the ones we use today.

@Furslid

Does this require more understanding than that one place has salt, but the other doesn’t, but would like salt too?

I don’t know why it did not happen earlier – but maybe it is an important civilization corner stone and if it happened earlier – then everything would just follow earlier and we would have this same conversation earlier?

A description of a situation where someone had abysmal strategic sense? Such as, say, two women fighting over a baby, and they were told that the baby was going to be split between them, and one of them one wasn’t smart to realize that “Sure, sounds fair to me” was not a good response?

She thought “Sure, sounds fair to me” was a good response because a king willing cut a baby in half is dangerous and you better do whatever he wants. Solomon’s trick depended on the true mother’s maternal love overwhelming her reason.

They’re low-class hookers. Picture them as the type of person who goes on Maury and it becomes a lot more plausible.

Or, you know, somebody wanted to tell a story with a moral, while pumping up the reputation of a revered king, and hit on this idea of a woman who cared only about pride and possession, contrasted with a woman who wanted the best for her child? I guess you’d need a theory of mind to think up a story like that, whenever it was thought up.

Even a woman who only cared about pride an possession, if she had even basic theory of mind, would realize that she should at least pretend to care about the baby.

Trade as strategizing doesn’t seem to work. To me, it’s probably more about interacting with people who just think differently than you. In a tribe, you know everyone and they all have the same basic assumptions. When you deal with people who are so different from you, it has an affect. I grew up a conservative Christian and when I started watching tv shows for adults, it was jarring.

Furthermore wouldn’t a lack of theory of mind preclude any sort of deception-based strategy like, oh, say, hiding a bunch of men inside a wooden horse and expecting your enemies to bring it within their walls? (Or disguising yourself as an old man to sneak inside your house and kill your wife’s suitors, or escaping from a cyclops whilst hiding under a sheep, or…)

Understanding that others don’t know that an object is hidden inside another object unless they’ve seen it hidden is exactly one of the developmental milestones used to assess children’s theory of mind. The existence of the Trojan Horse story in the Odyssey might not prove that the Bronze Age Greeks had a fully modern theory of mind but it certainly puts limits on what sort of theory of mind they might have had.

But they think that Odysseus is super-smart for coming up with all these ideas, instead of just “some guy.”

Reading the Odyssey makes his brilliance seem a lot more like everyone else is dumb than like he’s a unique genius. Of course, we have lots of knowledge they don’t, but… isn’t that what this is about?

I agree that the plots of the “cunning Odysseus” are not exactly Lex Luthor level stuff.

Still, without a 3/4/5-year-old’s level of theory of mind, the story of the Trojan Horse would be incomprehensible and unimaginable to both Homer and his audience.

Then again, even a squirrel knows how to hide objects. Is the squirrel applying a theory of mind when it buries its nuts, or does it just feel an inexplicable urge to do so?

The latter. That’s why the squirrel doesn’t understand that hiding something while someone is watching you is not effect. Ravens, on the other hand, do understand that.

And they understand without the benefit of our culture’s theory of mind!

I think the point here about comprehensibility is well taken.

The idea that Odysseus was (for his times) staggeringly intelligent for realizing “wait, if we all hide inside the giant wooden horse, the Trojans won’t know we’re in there” doesn’t work because then nobody would have understood the plot because nobody has a concept of “hiding.”

For that matter, it is SUPER obvious that any hunter-gatherer society (with an emphasis on ‘hunter’) must necessarily have a good concept of how to hide, or to prepare a trap and know animals will blunder into it because they don’t know it’s there. Animals get by on instincts and by having super keen senses that just make it impractical to hide from them at all, but humans don’t seem to have that going for them. And most animals, notably, don’t construct traps or snares… humans do.

Likewise, it seems hard to imagine how we’d develop language (let alone written language!) without a theory of mind. How did our ancestors of five or ten millennia ago develop language so sophisticated and complex, if they didn’t have a clear concept of what “thinking” and “mind” were, or if they didn’t really understand things like ‘other people may have different thoughts and feelings than I do?”

I know children today learn language before developing complete theories of mind… But if you took an entire species of people who have the mentality of a human toddler when it comes to understanding other people’s emotions and mental state, and none of them already knew complex language, would they develop it on their own?

I kind of can’t escape the conclusion that the rise of language came after the rise of consciousness and after at least limited theory of mind emerged in proto-human adults.

When squirrels are aware that they are being observed, they will pretend to hide a nut (“fake burial”) and then run off to reach an unobserved location while their observer tries to dig up a nonexistent nut. That suggests theory of mind.

How good are squirrels at differentiating between “I am being observed” and “there is another lifeform in the area?”

For example, how do squirrels behave when observed by creatures who are entirely uninterested in them and won’t be digging up the nuts realistically? How do they behave when there is a sleeping animal present, or an animal that is preoccupied with something else?

Because “fake burial then run off and do real burial” is within the realm of behaviors that instinct could explain, even in the absence of theory of mind. Theory of mind is what you need to figure out from observation whether or not nearby creatures are watching you or not, by directly examining their behavior and not merely reacting to their presence.

I don’t know why I can’t reply to Simon_Jester down below, so I’ll just do it here:

We don’t have to assume the level of theory of mind is monotonic increasing. Two neighbour ancestral tribes would have reasons to deceive each other, and hunter-gatherers need to know how to hide. But I could almost imagine Bronze-age large-scale civilisation (i.e. city-states) being a technology that allowed people do dispense with theory of mind by homogenizing people at a large scale.

So hunter-gatherers had some amount of TOM, then it was locally lost as vestigial with the rise of homogenous large-scale civilisation in the bronze age (along with all the other changes from hunter-gatherer-tribal to agricultural-feudal society, like how hunter-gatherers were individually smarter, stronger, and taller than their agricultural competition), then it re-emerged once it became memetically adaptive again with the bronze age collapse and the situation shifted to a new equilibrium (feudal agricultural civilisation, but with high levels of TOM) where it didn’t go away until now.

At least that’s one just-so story you could tell that seems more plausible than monotonically increasing TOM: widespread TOM and centralised idol-worship allowing you to largely (!) dispense with TOM because everyone thinks the same are competing technologies/ways a society can work, that are in direct opposition to each other (tautologically).

It’s tricky evaluating how cunning Odysseus was, especially in the case of the Trojan Horse, because we live in a civilizational context that has had 3000+ years of knowing “Let’s all hide in this giant wooden horse and hope our enemies mistake it for a going-away present” as an iconic legendary ruse. For us, calling it “the oldest trick in the book” is only a moderate exaggeration. But somebody had to think of it first, and that guy would have seemed really, really smart when they tried it and it worked.

There was also a religious component that we don’t immediately understand today but would have been understood by the audience. The horse (the story goes) was meant as an offering to Athena, so the Trojans would be offending the gods by not accepting it. Offending the gods would have led to destruction for the Trojans in the failure of crops or natural disaster and they had to balance that with the possibility it was a trap—they weren’t necessarily totally naive

Also we should keep in mind that this whole story was mythologized and different parts or different characters may have been adapted from other legends. We have Odysseus the culture hero whose thing is being really smart and we have the story of Troy and the Trojan horse. Maybe they were tied together from the beginning but it is also possible they were not initially related and that over hundreds of retellings by illiterate bards, Odysseus becomes the person who invents the ruse. Oral epic before writing is in some ways more like a game of telephone than history as we know it.

Correct me if I’m wrong, but wasn’t it an offering to Poseidon? Athena is not typically associated with horses. And wasn’t it that it was meant to appear to be an offering from the Greeks to Poseidon and that the Trojans were under no obligation to take it but rather felt they would gain favor and prestige by stealing the Greeks offering?

@FLWAB

It’s true that Poseidon is the god of horses but the tradition is that the offering was to Athena. The “standard” version is explained in Vergil’s Aeneid Book II. If I remember correctly there’s a sort of reverse psychology where the guy the Greeks leave behind tells the Trojans that the Greeks want the Trojans to be suspicious in order that the Trojans refuse the gift which would annoy Athena (Minerva to Vergil) and destroy their city.

But Vergil postdates Homer by 600-700 years. After reading your comment I was curious and I took a look to see if I could find any earlier sources that explicitly mention one of the gods. I couldn’t find any and the Odyssey just says gods (θεῶν) (VIII. 510). It says that the Trojans were divided three ways. Some want to chop up the horse, others want to throw it from the cliffs, and the last groups wants to offer it to the gods. It seems weird to us that’s listed as “three ways” and not just two (destroy it or keep it) but I think that’s another example of religious thinking. Throwing it off of a cliff might offend the gods less than chopping it up.

Another thing to keep in mind is that the strict division of the gods into categories is a later thing. In Homer’s time the gods had general domains of power but it’s more difficult to characterize a god as “god of only this one thing.” Athena also makes sense for two reasons: 1. she was on the Greek side of the war and a supporter of Odysseus. 2. Homeric Athena is the goddess and protector of the city-state. We think of Athena as the goddess of wisdom at least partially due to later conflation with Roman Minerva. In Homer, Athena was the goddess of warfare (but not wild slaughter, that was the least popular Olympian, Ares) and of the city. If the Greeks wanted the Trojans to take an offering inside their city borders it would make sense it would be an offering to Athena.

In fact, it was deliberately built too large to fit in the gate with the claim that this was to prevent the Trojans from bringing it in (and the real reason of getting them to damage their own gate).

Also, the guy who told them this was supposed to have escaped human sacrifice, or been left behind, so he clearly could deceive.

(It was to Athena, by the oldest accounts.)

Jaynes says the Odyssey is later than the Iliad and is basically a celebration of the new “theory of mind” thing, with Odysseus as a sort of Prometheus-figure bringing theory of mind into the world. That’s why, as commenters above note, he’s celebrated as devious and brilliant for five-year-old-level plots.

In the land of the blind,

the one-eyed man is kingsorry, too soon.Isn’t the simpler explanation that:

a. If everyone is hitting the enemy with pointed sticks and their response to the problem of “we’ve been here for ten years already and we haven’t made much headway” is “let’s hit them even harder“, the guy who proposes any sort of solution that doesn’t boil down to “hit people with sticks” is going to look like Einstein – especially if it works,

b. In order to come up with a brilliant stratagem one has to be a brilliant strategist and appreciating the brilliance requires a sufficient level of sophistication on the part of the audience. There’s no reason to believe (the collective) Homer was a brilliant strategist, nor was his target audience a bunch of military nerds that had a sufficient understanding to see what makes the strategy brilliant. To see the elegance of a solution to a chess problem, for example, you need to be sufficiently good at chess. Everyone understands a big wooden horse.

How/does Jaynes address Genesis ?

The Abraham-Jacob plot can be neatly read as bicamerality breaking down into ToM in the course of three generations.

It starts with Abraham rejecting personal gods in favor of a more abstract universal one who only sometimes speaks to him and directs his actions, his grandson Jacob is already seen using some advanced ToMing to get his brother to trade his birthright for food while still engaging in a struggle with the bicameral vestiges in a dream.

Wikipedia places Genesis’s writing at 6th or 5th century BC. Doesn’t that line up with ET Jaynes’s timeline?

5th-6th century would be the time of writing and I think it’s a given that the authors of the book themselves possessed a ToM because they describe things like repent and contemplation but the ancient myths recounted – some probably derived from the summerian and accadic ones like epic of Gylgamesh date to much earlier times, the Canaanite lands to which Abraham was sent to by God would have been there at the late bronze age

The method that Odysseus used to get Achilles to join the Trojan war is complicated enough that I teach it in my game theory class. Basically, when the Greeks come to recruit Achilles his mother dresses up her son as a girl and places him among girls because she doesn’t want him to fight. Odysseus has the challenge of figuring out which person dressed as a girl is Achilles. Odysseus asks everyone dressed as a girl to go to a table that has lots of weapons on it. Odysseus then suddenly blows a battle horn and all the girls run away while (born to fight and not very bright) Achilles instinctively grabs a weapon.

Do you also teach the method from Tom Sawyer & Huckleberry Finn?

Were this one woman finds out that the two “girls” she has taken in, are really boys, by throwing something at them. Back then, boys put their knees together to catch something in their lap, girls open their legs to catch it with their skirt.

But back to Odysseus, this also works as a just so story to describe someone who has a better theory of mind, as the people around him. He is aware that Achilles dressed as a woman will still instinctivly act as a warrior, because despite the female outside he is still Achilles.

How is Achilles old enough to fight but young enough to pass for a girl?

@bullseye

My mother told me that, she felt like the people did not percive her as a women when she went to Turkey in the 70ties. When “Trouseres and no veil” signals man, to people they just don’t look to closely.

So maybe a close shave, the right hairdress and women specific clothing might be all that most people needed to be fooled in that time.

I think there are similar theories, how the female pirates we know about, were able to pass as man, in the close environment of a ship.

That episode is not from the Iliad though. Its earliest (extant?) depictions date from the classical period, well after the transition supposedly happened.

I feel like our reference pool of verifiably authentic fiction that dates back to before the Bronze Age Collapse is small enough that it’s going to be kind of hard to prove to the standards of this theory that yes, the ancients had a theory of mind based on these fictional accounts.

Even most of our myths dating back to that era are the product of stuff that got repeatedly transcribed and cannot be convincingly dated back to earlier than, say, 700 BC.

There were plenty of people writing things down before then, but before the Bronze Age Collapse, writing in the Near East was a specialty discipline devoted to preparing written records, usually for bureaucratic purposes. People weren’t writing the Great Sumerian Novel.

So about all we’ve got to work on is either the equivalent of government inventory catalogs, or stylized religious documents like the stuff the ancient Egyptians carved into tomb walls.

The former isn’t going to tell us whether the lights were on inside at the time or whether all the scribes were in conversation with hallucinatory imaginary friends because they didn’t have a theory of mind and were in a state of induced schizophrenia. And the latter, while we might call it fiction today, doesn’t have the core traits of a work of artistic fiction. It’s standardized and will tend to remain stable over long periods during which things like customary linguistic metaphors and figures of speech get forgotten. It’s hieratic and ritualized rather than being designed to keep the interest of an audience using relatable characters.

So once we start dismissing ancient myths as ‘not ancient enough,’ we’re going to run real short on source material, real quick. Not entirely out of it, but short.

How is that related to game theory? And that article seems to be written by someone with only a passing familiarity with game theory.

Going by this along with DarkTigger’s comment about Huckleberry Finn seems like *very* strong evidence that the readers of the Illiad and the target audience of Huckleberry Finn 3000 years later had any major gaps intelligence-wise, since very similar stratagems are used to signify “smart, observant, clever person” in both. This matches the theoretical model that if all humans have had the same capacity on a genetic level and been using the same energy to run our brains, anyone who just wasn’t using it would have a massive disadvantage even in competitions within their own tribe.

On a broader note: I have a very strong prior to suspect any claim that the ancient Greeks invented a particular thing circa 500 bc or a bit earlier, because at that time in Greece just after the arrival of the Phoenician alphabet there was a huge explosion in *writing down* of things other than government propaganda and business records, so a lot of people claim that the ancient Greeks invented literally everything when really they were just the first to write about it extensively (that’s survived to the present day- the fact that medieval monks were more interested in Greek works than their contemporaries was a huge factor too). This theory focuses on a slightly earlier time period, but it’s close enough and has the same format as those “having fun with your friends was invented in 538 ad in the city of Thebes” claims that it still pings the same BS-detector for me.

No One In Particular,

It relates to a separating equilibrium. Imagine you have private information about your true nature, and I want to find your true nature, but you have some incentive to lie to me. I will try to arrange a situation so that you will take a different visible action depending on your true nature.

@DarkTigger

Interesting idea about recognizing gender. I always wondered this about Shakespeare plays, too–is it really supposed to be plausible that a woman could pass as a man or vice versa in all these different situations? It’s not like they would have had Mrs. Doubtfire levels of makeup to work with. Being able to tell someone’s gender seems like a pretty basic human skill. Do you have any more info about how it might be limited by culture? Some quick googling hasn’t turned up much.

My understanding is that “separating equilibrium” refers to a situation where it is game-theoretical optimal to reveal private information, not any situation where an external stimuli causes a person to reveal private information.

Dumb story is dumb story, thousands of years old or not. It deserves neither credence nor criticism.

I always wondered this about Shakespeare plays, too–is it really supposed to be plausible that a woman could pass as a man or vice versa in all these different situations?

Remember that boys/young men were playing the female roles in those plays. So you had boys pretending to be women pretending to be men. At some level that had to be a meta joke the audience was in on.

Anyway, even today people will accept a whole lot of implausibility in the service of humor. A quick look at any TV sitcom will tell you that. Are there any examples of a gender switching in Shakespeare’s tragedies?

@dogiv

Note that there have been well-attested real life example of (certain) men passing as women, and vice versa. For example, Richard Zarvona, the cross-dressing Civil War pirate. Or Bonnie Prince Charlie.

And there have been at least dozens of well-attested real life examples of women passing as men in army life.

Yes, but being able to bypass deliberate deception about someone’s gender is not a basic human skill. It’s almost never relevant. Most humans simply have no incentive to conceal their gender, and don’t try. Indeed, most humans accentuate their gender, intentionally adopting exaggerated gender characteristics expected of them by society. This occurs to the point where if a man thinks he doesn’t look manly enough he may decide to grow a beard for that reason alone, and if a woman thinks she doesn’t look womanly enough she may start wearing push-up bras or something.

Women put on makeup and personal accessories that (by custom) no man would wear. Men and women adopt different clothing, different hairstyles, different manners of speech, different body language.

Furthermore, there is actually little or no adverse consequence to a typical human of not knowing a given person’s biological sex, or alternatively their gender. If you’re not interested in them as a romantic partner, what they have between their legs is unlikely to matter to you in any practical way. If you ARE interested in them, then even if you somehow manage to be completely mistaken about the matter… Well, there is no inherent consequence of being wrong, beyond an awkward situation in the bedroom. All the consequences of accidentally misgendering someone are socially constructed, and even the socially constructed ones usually aren’t too bad in practice.

Therefore, most humans have no real reason to develop sophisticated skills for “clocking” a cross-dresser, be they male or female. They have every reason to just use the human brain’s fertile powers of pattern-matching to assume that anyone who struts and belches and wears men’s clothing and stuffs a sock down the front of their trousers is a man. And that conversely, anyone who sits primly and speaks in a thin, quiet, high-pitched voice and wears body-concealing women’s clothing is a woman.

EDIT:

As an addendum to this, in the ancestral environment (a hunter-gatherer band), such deceptions would be nearly impossible because there are almost no encounters with strangers. When you and everyone you know is part of a group of at most 100-200 people who live in the wild under Stone Age conditions for decades at a time, there are very few opportunities to be somehow confused as to whether the person you’re interacting with is male or female.

@Simon_Jester

There are huge consequences to misgendering someone.

Their gender presentation is one of the most important factors in someone deciding whether they’re interested.

If you run into gay panic, that’s a rather serious consequence. Or they’re insulted that you misgendered them. And if you’ve invested resources into wooing them, then those resources are wasted. Physical appearance is extremely important in sexual selection. Our brains are hard-wired to evaluate secondary sex characteristics. The matter of which sex someone is is extremely important and something that evolution has devoted a large amount of resources to. Consider what sort of resources you would need to make a computer program that can reliably tell what sex someone is, versus how easy it is for a human to do it. The widespread existence of sex-differentiated pronouns is just one sign of how important sex is to humans.

Social consequences are still consequences.

Interesting, I didn’t r

There are historical records of similar ruses being used in the actual Bronze Age, though. E.g., a Hittite general once pretended to abandon a siege and march his army away, and then when the defenders had let their guard down and started partying he hurried back and took their city by escalade before they could reorganise their defences.

Importantly, that particular ruse de guerre would probably work in real life in the modern day. If someone told me that the commander of an eighteenth century army had used a similar trick to storm a fortified city, I’d believe it. You don’t have to have some kind of childlike inability to comprehend deception to believe, after weeks or months of siege warfare, that the enemy is actually packing up and marching away, or to let down your guard after they remain out of sight for a day or two.

It’s not prudent, wise, or smart, but it’s not some kind of blinding “you cannot possibly be a functional adult and be this stupid” stupidity compared to the kinds of mistakes people make in the real world in the present day.

No radical revolution in the nature of consciousness or cognition required.

It’s possible that as the human support system improved, there was less & less possibility of getting support from a spirit.

The spirit solves & articulates your puzzles & omens. Once other humans started doing it, there is little left for the spirit to do for you.

I don’t think it’s implausible that entire cultures could miss obvious (to us in hindsight) strategies for centuries. Many people today still play Tic-Tac-To!

Do adult seriously play Tic-Tac-To? I stopped as a kid for the obvious reason.

I occasionally played it well into my teens.

Of course the vast majority of individual games are ties, but it you keep playing enough times eventually one of you will blunder and lose.

Or if you play against someone who realizes that memorizing the strategy of a kid’s game is hardly productive use of one’s time.

I played an excellent computer game called Fran Bow a couple of years ago, and this was in fact one of the puzzles you had to solve.

Another weird example of this is basic probability. The Greeks loved gambling and were good at logic, but the scoring of their games was nonsensical by modern standards. It’s not like they needed full-fledged probability theory to figure this out—knuckle bones were scored the same whether they landed on the broad face or on their edges, for example. It looks more like having some conceptual blind spot.

Maybe that was part of the point of the game? The premise that all six sides of a die have to be equally likely to come up sounds a lot more culturally constructed than the idea “the die is more likely to come up on the big sides than the small ones.”

Looking at a translation of the Complaint Tablet to Ea-Nasir (written c. 1750 BC, about 500 years before the Bronze Age Collapse), it seems to imply at least a toddler-level understanding theory of mind.

The bits I emphasized in particular sound like the complainant (Nanni) is thinking about the mental state behind Ea-Nasir’s actions and is issuing a warning in hope of deterring future misbehavior on Ea-Nasir’s part.

I think using theory-of-mind instead of consciousness is an improvement but it brings its own problems. Like not having a theory-of-mind making you incapable of trading. Maybe modern-theory-of-mind would have been better.

Scott writes

> Theory-of-mind-space is wider than we imagine

Clearly bronze age people had a concept of a mind – multiple actually. All those voices. And they seemed to ascribe intentions to them. It is just not the modern state of there being a single ‘I’ voice (mainly; see the exceptions mentioned like imaginary friends). The modern expectation of a single mind/voice simplifies a lot of things – like trade – but hides the complexities of the individual – which then show up as ‘disorders’.

Could explain how europeans conquered the Americas so easily.

Still, I’m confused as to how a theory of mind would lead to better strategic thinking or how “I have an internal voice I model as a god” seems to be treated as somehow more closely related with “I don’t have an internal monologue” than “I have an internal voice I model as myself”.

I think the part where all of the Native Americans were dead of diseases is a good enough explanation on its own.

Generals would choose their military moves based on signs from the gods. It’s been suggested that this was useful as an injection of randomness, to keep them from becoming predictable.

Maybe this is why the sea peoples wiped the floor with everyone else. Having one group come up and completely dominate all others in warfare or trade is not uncommon, though in the modern times we attribute this to technology.

I’d say in most cases it had a lot more to do with asabiyyah than technology.

What’s more valuable: asabiyyah or a sophisticated and deceptive strategy/tactics? I think most of the time, asabiyyah. It’s pretty rare that the arc of a civilization is decisively turned by superior strategy and tactics. Hannibal died a failure. Most of the time we point to military geniuses who prevailed against all odds, they also happened to have a large advantage in asabiyyah over their enemies.

And I don’t know that asabiyyah benefits from theory of mind. It might be better to think of your opponents as alien and monstrous.

You make a good point on tactics (and made me look up asabiyyah), but there are two items to consider:

One is that we generally only appreciate tactical genius when it’s exposed due to a force mismatch. People venerate Yi Sun-sin because he prevailed over impossible odds. Even generals like Lee and Hannibal are remembered even though they were ultimately defeated because they managed to claim victories where they should have had none. When tactics serve only to make the likely certain they are less likely to be celebrated.

On the strategic front, it is hard to imagine a group without theory of mind prevailing over one that does, simply because so much of strategy involves predicting the enemies’ actions and manipulating them to fight when and where you want to. If you cannot do this then you are unlikely to anticipate it being done to you and will be surprised time and time again, constantly fighting on unfavorable terms.

This is a great question.

I once in high school opened a book of military history. It started with a few landmark ancient greek battles, the first of which was a Battle of Leuctra (apparently 371 BC) where the innovation was to not distribute their soldiers equally over the width of the battlefield. So it seems there wasn’t a lot of strategy in war in the Bronze Age.

Strategy games are a different game entirely. It seems like some version of Checkers existed since 3000BC, and it definitely requires a theory of mind to play well, although I was able to play it (badly) at an age where you’re not supposed to have one yet. Weiqi (Go in japanese, Baduk in korean), which is very much about strategy and tactics, was invented (Lasker would say discovered) circa 2000BC. This page has a poem dated around year 0 that shows there were strong players at the time (as well as a game listing from 400AD that the dan-level players at r/baduk say was played by players who are stronger than them, how cool is that!), but this is a thousand years after the date we’re interested in.

This post seems to sidestep what I consider to be the single most interesting question (except maybe when it’s talking about pre-bicameral thought). What causes us to hear voices in our heads?

This post claims that pre-bronze-age peoples heard voices speaking to them and assumed they were gods. I hear a voice in my head and have some ability to control it (i.e. if you tell me to make the voice say something, I can do that, but if you ask me to make the voice stop, that’s harder). I base a lot of my decisions on the things that voice says, similarly to how I would base my decisions on what external people say. If I monologue about how I should go on a diet, it has a similar effect to listening to a podcast about going on a diet (namely I may take some steps towards that but won’t necessarily accomplish it). A lot of our understanding of consciousness and the mind in general is based on how we understand that voice, and this blog post is an example of that.

What is the voice though? Why do humans hear that? I had heard of Jaynes’s book before, and thought from the title that it would explain the evolutionary origin of the voice. Do we think monkeys have something like it? Is it an obvious byproduct of our capacity for language? Is the voice real, or just something I’ve been taught to claim I can hear? Like maybe I have abstract thoughts in the first place, but whenever I’m asked to speak about them I translate them into words, and when I try to think about my own thoughts I often transcribe them into words for convenience? What is the voice?

Hot take: Indian monkeys experience it as Hanuman, Egyptian monkeys experience it as Thoth.

It is good that you stopped using the word “mind”.

The voice is making up a science that can end nescience.

They do, obviously. They too suffer. They too want to get out of suffering. That said, they have limited puzzles & omens. The answer cannot exceed the question.

Global Workspace Theory holds that one of the primary functions of consciousness is to be a place where different subsystems in the brain exchange information between each other. Under this model, the voices that people hear in their heads are just like any other thoughts, emotions, mental content etc.: information coming from some particular subsystem, which just happens to be relayed in the form of internal speech.

Many people also report that the voices they hear remind them of real people: someone might have a critical voice which resembles that of their critical mother, for instance. In that case, the voice would be the product of a subsystem which has evolved to model the expected reactions of other people, and report how they would react. If you have internal models of other people, telling you what they would disapprove of, then that model can express its disapproval before you do a thing – in which case you don’t need to suffer the consequences of doing the thing and then suffering from the disapproval of the real person. (Likewise, if you have encouraging voices, they might push you to do socially approved things that you otherwise wouldn’t.)

(“An internalized model of society’s rules” seems like it would pretty well match having the ruler’s voice in your head…)

A related paper: Frith & Metzinger argue that one of the functions why consciousness evolved, might be to allow models of group interests to be integrated with one’s psyche. This allows the group model to regulate the individual’s behavior, and allows for social emotions such as regret, when one realizes that their individual preferences have violated group preferences:

That’s…brilliant. Thanks for posting. That’s as right as I’ve ever heard anyone say it.

Chicken-and-egg problem here. Why consider these “social control” mechanisms to be “inherently social”, instead of “social control” co-opting mechanisms of a more general nature?

The last two paragraphs you quoted are intriguing, barring the ultimate sentence.

Wait, people get multiple voices, and ones with distinct Identities? I only get one voice, my own internal narrative, and it’s really bland. I’m mildly autistic though, I guess maybe that explains it?

I always assumed that I think in words.

And I was really surprised some time ago by this Reddit thread and people on LessWrong saying they lack internal monologue.

So, I’ve read some articles about experiments in which they asked people at random moments during the day what mode of thinking they were experiencing at the moment, and a lot of the answers indicated non-verbal thoughts going on.

And then I’ve realized there is one possibility I haven’t even considered to be a hypothesis before: that I am not honest with myself when I ask myself “what mode of communication do I use?”.

I *recall* that I was using words, but did I really?

What if I think in abstract terms, but when I am *asked* *what* I was thinking I am serializing it to string?

What if this is just like in those lazy-evaluated expressions in some programming languages which only “collapse”/evaluate when you really need them?