There’s been recent controversy about the use of face masks for protection against coronavirus. Mainstream sources, including the CDC and most of the media say masks are likely useless and not recommended. They’ve recently been challenged, for example by Professor Zeynep Tufekci in the New York Times and by Jim and Elizabeth on Less Wrong. There was also some debate in the comment section here last week, so I promised I’d look into it in more depth.

As far as I can tell, both sides agree on some points.

They agree that N95 respirators, when properly used by trained professionals, help prevent the wearer from getting infected.

They agree that surgical masks help prevent sick people from infecting others. Since many sick people don’t know they are sick, in an ideal world with unlimited mask supplies everyone would wear surgical masks just to prevent themselves from spreading disease.

They also agree that there’s currently a shortage of both surgical masks and respirators, so for altruistic reasons people should avoid hoarding them and give healthcare workers first dibs.

But they disagree on whether surgical masks alone help prevent the wearer from becoming infected, which will be the focus of the rest of this piece.

1. What are the theoretical reasons why surgical masks might or might not work?

Epidemiologists used to sort disease transmission into three categories: contact, droplet, and airborne. Contact means you only get a disease by touching a victim. This could be literally touching them, or a euphemism for very explicit contact like kissing or sex. Droplet means you get a disease when a victim expels disease-laden particles into your face, usually through coughing, sneezing, or talking. Airborne means you get a disease because it floats in the air and you breathe it in. Transmission via “fomites”, objects like doorknobs and tables that a victim has touched and left their germs on, is a bonus transmission route that can accompany any of these other methods.

More recently, scientists have realized that droplet and airborne transmission exist along more of a spectrum. Droplets can stay in the air for more or less time, and spread through more or less volume of space before settling on the ground. The term for this new droplet-airborne spectrum idea is “aerosol transmission”. Diseases with aerosol transmission may be spread primarily through droplets, but can get inhaled along with the air too. This concept is controversial, with different authorities having different opinions over which viruses can be aerosolized. It looks like most people now believe aerosol transmission is real and applicable to conditions like influenza, SARS, and coronavirus.

Surgical masks are loose pieces of fabric placed in front of the mouth and nose. They offer very good protection against outgoing droplets (eg if you sneeze, you won’t infect other people), and offer some protection against incoming droplets (eg if someone else sneezes, it doesn’t go straight into your nose). They’re not airtight, so they offer no protection against airborne disease or the airborne component of aerosol diseases.

Respirators are tight pieces of fabric that form a seal around your mouth and nose. They have various “ratings”; N95 is the most common, and I’ll be using “N95 respirator” and “respirator” interchangably through most of this post even though that’s not quite correct. When used correctly, they theoretically offer protection against incoming and outgoing droplet and airborne diseases; since aerosol diseases are a combination of these, they offer generalized protection against those too. Hospitals hate the new “aerosol transmission” idea, because it means they probably have to switch from easy/cheap/comfortable surgical masks to hard/expensive/uncomfortable respirators for a lot more diseases.

Theory alone tells us surgical masks should not provide complete protection. Coronavirus has aerosol transmission, so it is partly airborne. Since surgical masks cannot prevent inhalation of airborne particles, they shouldn’t offer 100% safety against coronavirus. But theory doesn’t tell us whether they might not offer 99% safety against coronavirus, and that would still be pretty good.

2. Are people who wear surgical masks less likely to get infected during epidemics?

It’s unethical to randomize people to wear vs. not-wear masks during a pandemic, so nobody has done this. Instead we have case-control studies. After the pandemic is over, scientists look at the health care workers who did vs. didn’t get infected, and see whether the infected people were less likely to wear masks. If so, that suggests maybe the masks helped.

This is an especially bad study design, for two reasons. First, it usually suffers recall bias – if someone wore a mask inconsistently, then they’re more likely to summarize this as “didn’t wear masks” if they got infected, and more likely to summarize it as “did wear masks” if they stayed safe. Second, probably some nurses are responsible and do everything right, and other nurses are irresponsible and do everything wrong, and that means that if anything at all helps (eg washing your hands), then it will look like masks working, since the nurses who washed their hands are more likely to have worn masks. Still, these studies are the best we can do.

Gralton & McLaws, 2010 reviews several studies of this type, mostly from the SARS epidemic of the early 2000s. A few are underpowered and find that neither surgical masks nor respirators prevent infection (probably not true). A few others show respirators prevent infection, but do not investigate surgical masks (probably right, but useless for our purposes). Two seem relevant to the question of whether surgical masks work:

Rapid awareness and transmission of SARS in Hanoi French Hospital, Vietnam was conducted in a poor hospital that only had surgical masks, not respirators. In the latter stages of the epidemic, 4 workers got sick and 26 stayed healthy. It found that 3 of the 4 sick workers hadn’t been wearing masks, but only 1 of the 26 healthy workers hadn’t. This is a pretty dramatic result – subject to the above confounders, of course.

Effectiveness of precautions against droplets and contact in prevention of nosocomial transmission of SARS is larger and more prestigious, and looked at a cluster of five hospitals. Staff in these hospitals used a variety of mask types, including jury-rigged paper masks that no serious authority expects to work, surgical masks, and N95 respirators. It found that 7% of paper-mask-wearers got infected, compared to 0% of surgical-mask and respirator wearers. This seems to suggest that surgical masks are pretty good.

The meta-analysis itself avoided drawing any conclusions at all, and would not even admit that N95 respirators worked. It just said that more research was needed. Still, the two studies at least give us a little bit of evidence in surgical masks’ favor.

How concerned should we be that these studies looked at health care workers specifically? On the one hand, health care workers are ordinary humans, so what works for them should work for anyone else. On the other, health care workers may have more practice using these masks, or may face different kinds of situations than other people. Unlike respirators, surgical masks don’t seem particularly hard to use, so I’m not sure health care workers’ training really gives them an advantage here. Overall I think this provides some evidence that surgical masks are helpful.

I was able to find one study like this outside of the health care setting. Some people with swine flu travelled on a plane from New York to China, and many fellow passengers got infected. Some researchers looked at whether passengers who wore masks throughout the flight stayed healthier. The answer was very much yes. They were able to track down 9 people who got sick on the flight and 32 who didn’t. 0% of the sick passengers wore masks, compared to 47% of the healthy passengers. Another way to look at that is that 0% of mask-wearers got sick, but 35% of non-wearers did. This was a significant difference, and of obvious applicability to the current question.

3. Do surgical masks underperform respirators in randomized trials?

Usually it would be unethical to randomize health care workers to no protection, so several studies randomize them to face masks vs. respirators. But a few others were done in foreign hospitals where lack of protection was the norm, and these studies did include a no-protection control group.

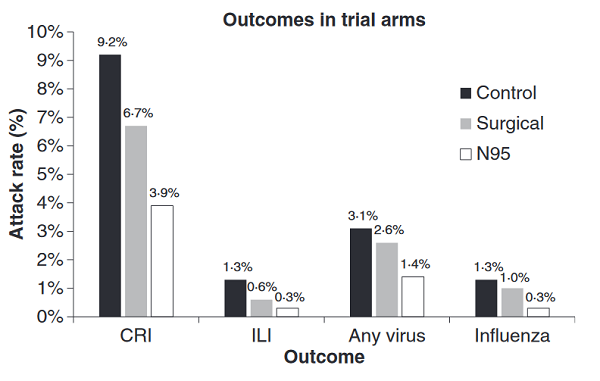

MacIntyre & Chugtai 2015, Facemasks For The Prevention Of Infection In Healthcare And Community Settings, reviews four of these. Two of the four are unable to find any benefit of either masks or respirators. The third finds a benefit of respirators, but only if nobody tested the respirators to see if they fit, which doesn’t make sense and suggests it’s probably an artifact. The fourth finds a benefit of respirators, but not masks. It seems unlikely that respirators don’t help, so this suggests all these studies were underpowered. If we throw good statistical practice to the winds and just look at the trends, they look like this:

In other words, respirators are better than masks are better than nothing. It would be wrong to genuinely conclude this, because it’s not statistically significant. But it would also be wrong to conclude the studies show masks don’t work, because they mostly show respirators don’t work, and we (hopefully) know they do.

Overall these studies don’t seem very helpful and I’m reluctant to conclude anything from them. In section 6, I’ll talk more about why studies may not have shown any advantage for respirators.

4. Do surgical masks prevent ordinary people from getting infected outside the healthcare setting?

The same review lists nine randomized trials with a different design: when the doctor diagnoses you with flu, she either asks everyone in your family to wear masks (experimental group), or doesn’t do that (control group), and then checks how many family members in each group got the flu.

How did these go? That depends whether you use intention-to-treat or per-protocol analysis. Intention-to-treat means that you just compare number of infections in the assigned-to-wear-masks group vs. the control group. Per-protocol means that you only count someone in the study if they actually followed directions. So if someone in the assigned-to-wear mask group didn’t wear their mask, you remove them from the study; if someone in the control group went rogue and did wear a mask, you remove them too.

Both of these methods have their pros and cons. Per protocol is good because if you’re trying to determine the effect of wearing a mask, you would really prefer to only be looking at subjects who actually wore a mask. But it has a problem: adherence to protocol is nonrandom. The people who follow your instructions diligently are selected for being diligent people. Maybe they also diligently wash their hands, and diligently practice social distancing. So once you go per protocol, you’re no longer a perfect randomized controlled trial. Only intention-to-treat analyses carry the full weight of a gold standard RCT.

According to intention-to-treat, the studies unanimously found masks to be useless. But there were a lot of signs that intention-to-treat wasn’t the right choice here. Only about a fifth of people who were asked to wear masks did so with any level of consistency. The rest wore the mask for a few hours and then get bored and took it off. Honestly, it’s hard to blame them; these studies asked a lot from families. If a husband has flu, and sleeps in the same bed as his wife, are they both wearing masks all night?

Of the three studies that added per-protocol analyses, all three found masks to be useful (1, 2, 3) . Does this prove masks work? Not 100%; per-protocol analyses are inherently confounded. But it sure is suggestive.

The review author summarizes:

The routine use of facemasks is not recommended by WHO, the CDC, or the ECDC in the community setting. However, the use of facemasks is recommended in crowded settings (such as public transport) and for those at high risk (older people, pregnant women, and those with a medical condition) during an outbreak or pandemic. A modelling study suggests that the use of face-masks in the community may help delay and contain a pandemic, although efficacy estimates were not based on RCT data. Community masks were protective during the SARS outbreaks, and about 76% of the population used a facemask in Hong Kong.

There is evidence that masks have efficacy in the community setting, subject to compliance [13] and early use [12, 18, 19]. It has been shown that compliance in the household setting decreases with each day of mask use, however, which makes long term use over weeks or months a challenge […]

Community RCTs suggest that facemasks provide protection against infection in various community settings, subject to compliance and early use. For health-care workers, the evidence suggests that respirators offer superior protection to facemasks.

Parts of this summary are infuriating. If the big organizations recommend that especially vulnerable groups wear masks, aren’t they admitting masks work? But if they’re admitting masks work, why don’t they recommend them for ordinary people?

It looks like they’re saying masks work a little, they’re too annoying for it to be worth it for normal people, but they might be worth it for the especially vulnerable. But then why don’t they just say masks work, and let each person decide how much annoyance is worthwhile? I’m not sure. But it looks like the author basically ends up in favor of community use of surgical masks in a pandemic, mostly on the basis of per-protocol analyses of community RCTs.

5. How do surgical masks and respirators compare in hokey lab studies?

Our source here is Smith et al 2016, Effectiveness Of N95 Respirators Versus Surgical Masks In Protecting Health Care Workers From Acute Respiratory Infection: A Systematic Review And Meta-Analysis. They review some of the same studies we looked at earlier, but then investigate 23 “surrogate exposure studies”, ie throwing virus-shaped particles at different masks in a lab and seeing if they got through. You can find the results of each in their appendix. Typically, about 1 – 5% of particles make it through the respirator, and 10 – 50% make it through the surgical mask. They summarize this as:

In general, compared with surgical masks, N95 respirators showed less filter penetration, less face-seal leakage and less total inward leakage under the laboratory experimental conditions described.

I think in general the fewer virus particles get through your mask, the better, so I think this endorses surgical masks as better than nothing, since their failure rate was less than 100%.

Booth et al, 2013 examines surgical masks themselves more closely. They hook a surgical mask up to “a breathing simulator” and then squirt real influenza virus at it, finding that:

Live influenza virus was measurable from the air behind all surgical masks tested. The data indicate that a surgical mask will reduce exposure to aerosolised infectious influenza virus; reductions ranged from 1.1- to 55-fold (average 6-fold), depending on the design of the mask…the results demonstrated limitations of surgical masks in this context, although they are to some extent protective.

The paper doesn’t discuss how particle number maps to infection risk. Does letting a single influenza virus through mean you will get infected? If so, any reduction short of 100% is useless. I have a vague sense that this isn’t true; your immune system can fight off most viruses, and the fewer you get, the better the chance it will win. Also, even respirators don’t claim to reduce particle load by more than 99% or so, and those work, so it can’t be that literally a single virus will get you. Overall I think modest reductions in particle number are still pretty good, but I don’t have a study that proves it.

6. Is it true that the public won’t be able to use N95 respirators correctly?

Yes.

I remember my respirator training, the last time I worked in a hospital. They gave the standard two minute explanation, made you put the respirator on, and then made you go underneath a hood where they squirted some aerosolized sugar solution. If you could smell the sugar, your respirator was leaky and you failed. I tried so hard and I failed so many times. It was embarrassing and I hated it.

I’m naturally clumsy and always bad at that kind of thing. Some people were able to listen to the two minute explanation and then pass right away. Those kinds of people could probably also listen to a two minute YouTube explanation and be fine. So I don’t want to claim it’s impossible or requires lots of specialized background knowledge. It’s just a slightly difficult physical skill you have to get right.

Bunyan et al, 2013, Respiratory And Facial Protection: A Critical Review Of Recent Literature, discusses this in more depth. They review some of the same studies we reviewed earlier, showing no benefit of N95 respirators over surgical masks for health care workers in most situations. This doesn’t make much theoretical sense – the respirators should win hands down.

The most likely explanation is: doctors aren’t much better at using respirators than anyone else. In a California study of tuberculosis precautions, 65% of health care workers used their respirators incorrectly. That’s little better than the general public, who have a 76% failure rate. Bunyan et al note:

The fitting of N95 respirators has been the subject of many publications. The effective functioning of N95 respirators requires a seal between the mask and the face of the wearer. Variation in face size and shape and different respirator designs mean that a proper fit is only possible in a minority of health care workers for any particular mask. Winter et al. reported that, for any one of three widely used respirators, a satisfactory fit could be achieved by fewer than half of the healthcare workers tested, and for 28% of the participants none of the masks gave a satisfactory fit.

Fit-testing is a laborious task, taking around 30 min to do properly, and comprises qualitative fit-testing (testing whether the respirator-wearing healthcare worker can taste an intensely bitter or sweet substance sprayed into the ambient air around the outside of the mask) or quantitative fit testing (measuring the ratio of particles in the air inside and outside the breathing zone when wearing the respirator). Attempts have been made to circumvent the requirement for fit testing, and it has been suggested that self-testing for a seal by the respirator wearer (see http://youtu.be/pGXiUyAoEd8a for a video demonstration) is a sufficient substitute for fit-testing. However, self-checking for a seal has been demonstrated to be a highly unreliable technique in two separate studies so that full fit-testing remains a necessary preliminary requirement before respirators can be used in the healthcare setting.

Operationally, this presents significant challenges to organizations with many healthcare workers who require fit-testing. Chakladar et al. pointed out that, in addition to the routine need for repeat testing over time to ensure that changes in weight or facial hair have not compromised a good fit, movements of healthcare workers between organizations using different makes of respirators would necessitate additional repeat fit-testing. Fit-testing is likely to remain problematic to health-care organizations for the foreseeable future. In addition to the requirement for fit-testing, ‘fit-checking’ is also required each time the respirator is donned to ensure there are no air leaks.

Is a poorly-fitting N95 respirator better than nothing? The reviewed studies suggest that at that point it’s just a very fancy and expensive surgical mask.

7. Were the CDC recommendations intentionally deceptive?

No, and I owe them an apology here.

I think the evidence above suggests masks can be helpful. Masked health care workers were less likely to catch disease than unmasked ones. Masked travelers on planes were less likely to catch disease than unmasked ones. In per protocol analysis, masked family members are less likely to catch disease from an index patient than unmasked ones. Laboratory studies confirm that masks block most particles. All of this accords with a common-sense understanding of droplet and aerosol transmission of disease.

None of these, except maybe the plane study, tell us exactly what we want to know. The SARS studies were all done in a health care setting, so they don’t prove that regular people can benefit from masks. But health care workers are closely related to homo sapiens and ought to have similar anatomy and physiology. Surgical masks aren’t as complicated as respirators and we can assume most people get them right. And although health care workers are in unusually high-risk situations, that should just affect the magnitude of the benefit, not the sign; obviously the level of risk ordinary people encounter is sometimes relevant, considering they do often catch pandemic diseases. So our default assumption should be that these studies carry over, not that they don’t.

Likewise, most of the community studies were done on family members. Most guidelines already say to mask up if you have a sick family member, so talking about subways and crowds requires a little bit of extrapolation. But again, being in a family is just one form of close contact. It would take bizarre convolutions to even imagine a theory where you can catch diseases from your family members but not from people you sit next to on a train. Our default assumption should be in favor of these results generalizing, not against them.

But the CDC has recommended against mask use. I hypothesized that the CDC was intentionally lying to us, trying to trick us into not buying masks so there would be enough for health care workers.

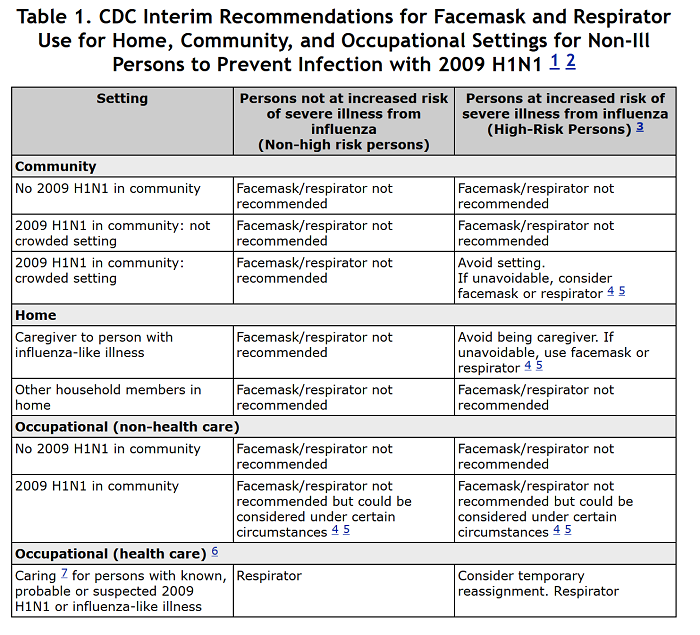

But that can’t be true, because the CDC and other experts came up with their no-masks policy years ago, long before there was any supply shortage. For example, during the 2009 swine flu pandemic, their website offered the following table:

And during the 2015 MERS epidemic, NPR said South Koreans were wrong to wear masks:

Masks can be helpful for protecting health workers from a variety of infectious diseases, including MERS…

But either type of mask is less likely to do much good for the average person on the street…Wearing a mask might make people feel better. After all, MERS has killed about a third of the people known to be infected.

But there are no good studies looking at how well these masks prevent MERS transmission out in the community, says Geeta Sood, an infectious disease specialist at Johns Hopkins University. “On the street or the subway, for MERS specifically, they’re probably not effective,” she says. One problem is that the masks are loose fitting, and a lot of tiny airborne particles can get in around the sides of the masks.

So if studies generally suggest masks are effective, and the CDC wasn’t deliberately lying to us, why are they recommending against mask use?

I’m not sure. I haven’t been able to track down any documents where they discuss the reasons behind their policies. It’s possible they found different studies than I did, or interpreted the studies differently, or have some other superior knowledge.

But I think that more likely, they’re trying to do something different with medical communication. Consider legal communication. If a court declares a suspect is “not guilty”, that could mean that he is actually not guilty of the crime. Or it could mean that he did it but they can’t prove it. Or it could mean that he did it, they can prove it, but the police officer who found the proof didn’t have a warrant at the time so they had to throw it out. A legal communication like “this man is not guilty” is intended not just to convey information, but to formally reflect the output of a sacrosanct process.

Medicine has been traumatized by its century-long war with quackery, and ended up with its jargon also formally reflecting the output of a sancrosanct process. Remember, there are dozens of studies supposedly showing homeopathy works, not to mention even more studies proving telepathy exists. At some point you have to redesign all your institutions to operate in an environment of epistemic learned helplessness, and the result is very high standards of proof.

Masks haven’t quite reached these standards. The case-control trials look good, and the per-protocol RCTs look good, but there aren’t really the large-scale intention-to-treat RCTs that would be absolutely perfect. Even if these studies work, they only prove things about the health care setting and the family setting, not “the community setting” in general. So masks haven’t been proven to work beyond a reasonable doubt. Just like the legal term for “not proven guilty beyond a reasonable doubt” is “not guilty”, the medical communication term for “not proven effective beyond a reasonable doubt” is “not effective”. This already muddled communication gets even worse because doctors are constitutionally incapable of distinguishing “no evidence for” from “there is evidence against” – I have no explanation for this one.

There’s an even more complicated language-use issue. The CDC may be thinking of its recommendations not just as conveying an opinion but as taking an action – performing the medical intervention of recommending people wear masks. All of those RCTs listed above show that the medical intervention of recommending people wear masks is ineffective. Sure, that’s because people don’t listen. But the CDC doesn’t care about that. They’ve proven that giving the advice won’t help, why are you still asking them to give the advice?

I’m not sure this is really the CDC’s reasoning. It seems pretty weird from the point of view of an organization trying to manage a real-world pandemic with people dying if they get it wrong. But I’m having trouble figuring out other possibilities that make sense.

8. So should you wear a mask?

Please don’t buy up masks while there is a shortage and healthcare workers don’t have enough.

If the shortage ends, and wearing a mask is cost-free, I agree with the guidelines from China, Hong Kong, and Japan – consider wearing a mask in high-risk situations like subways or crowded buildings. Wearing masks will not make you invincible, and if you risk compensate even a little it might do more harm than good. Realistically you should be avoiding high-risk situations like subways and crowded buildings as much as you possibly can. But if you have to go in them, yes, most likely a mask will help.

In low-risk situations, like being at home or taking a walk, I mean sure, a mask might make you 0.0001% (or whatever) less likely to get infected. If that’s worth it to you, consider the possibility that you might be freaking out a little too much about this whole pandemic thing. If it’s still worth it, go for it.

You are unlikely to be able to figure out how to use an N95 respirator correctly. I’m not saying it’s impossible, if you try really hard, but assume you’re going to fail unless you have some reason to think otherwise. The most likely outcome is that you have an overpriced surgical mask that might make you incorrectly risk-compensate.

If you are a surgeon performing surgery, bad news. It turns out surgical masks are not very useful for you (1, 2)! You should avoid buying them, since doing so may deplete the number available for people who want to wear them on the subway.

In the event that surgical masks become widely and cheaply available to the public, should we encourage everyone to wear one when in public, to reduce asymptomatic infected people infecting others?

In the mean time, should we be creating cloth masks for this purpose?

After reading this post, I find the “cloth mask” question pretty pressing. Do the data presented here apply to any piece of fabric placed over the nose and mouth? Or do surgical masks have some special properties that e.g. a scarf or bandana wouldn’t have?

Moreover, how much of the value is lost by re-using a mask? My guess is that it would still stop you from transmitting to others, but wouldn’t provide any protection to you because the virus can easily transmit to the mouth-facing side when taken on and off. Is that right, or am I fundamentally misunderstanding?

This post doesn’t do as good a job as usual at explaining things or looking at the evidence, and you shouldn’t think surgical masks are the same as cloth masks because of it.

Surgical masks are mostly made from paper (or other non-woven material). Cloth masks work worse than them according to the studies I’ve found.

https://academic.oup.com/cid/article/65/11/1934/4068747

https://link.springer.com/article/10.1186/1756-0500-6-216

It’s unclear, but one important reason that homemade cloth masks are a plausibly good idea is that wearers 1) won’t touch their face quite as much, and may remember to wash their hands better, 2) indicate that people in public are taking the risk seriously, and 3) don’t reduce the supply available to doctors and hospitals in the short term.

Also, to the extent the spread is because I cough and a biggish droplet lands on your mouth, a bandana will help with that. And big particles that have to make an extra right-angle turn to get into your lungs may also just not make it in. That’s not going to do much for the really tiny airborne dried-out droplets, but think of the times you’ve been close to someone when they sneeze, cough, or speak, and felt a droplet touch your skin–that’s happened to me, and if they’re infected and shedding virus, you’ve not got some infectious virus on you waiting to be rubbed into your eye or something.

The droplet that would have entered your mouth instead lands on the fabric, where the water evaporates, leaving airborne virus that you inhale.

N95 masks work in part because the holes in the mask/filter media are smaller than some dimensions of the virus. Fabric has holes on the micron scale.

@deciusbrutus:

Our instincts are very different here. My instinct, based on experience using often ill-fitting masks for paint, dust, smoke and solvent protection, is that all masks provide at least some benefit, and that any amount of direct exposure that can be prevented is a good thing. Yes, some of the virus will eventually be inhaled, but don’t you agree that the dosage of active virus will be less than if there was no mask? Some will remain dried on the mask, some (half?) will be blown away on an exhale, and some of what is inhaled will have been deactivated by the drying.

We lack exact numbers, but I’d hope you’d agree that the mask provides some reduction in exposure? Is it that you believe that infection is almost sure to occur over a small threshold, and thus this reduction provides no added protection? That the reduction can only be such a small amount that degree of protection should be ignored? Or something else? It feels like you are (correctly) pointing out that the protection is not perfect, and then jumping to the conclusion that the degree of protection that is provided is thus irrelevant.

decibrutus:

If that mechanism works, why does anyone ever wear a surgical mask?

@deciusbrutus:

CoV19 is very likely not airborne, probably due to being inactivated when drying. So for anthrax your comment would be correct, for CoV19 it is most probably not.

Some countries like the Czech republic and maybe the CDC do recommend cloth face covers as an alternative to masks. As a general question, this is probably very hard to answer, because there are too many variables. One layer of chiffon net is probably not going to do anything. On the other end of the spectrum, with tightly woven cloth and relevant expertise you could probably create a pretty good filter mask.

How you wear the mask is also really important. If your scarf keeps slipping of your face, or makes you itchy, you may well end up touching your face much more than you otherwise would. That’s probably a net negative.

Homemade fabric masks range from ~half as effective as surgical masks to ~about as effective as surgical masks in terms of raw filtration power, but have two downsides:

1. Universally, they don’t fit as well, leading to leakage around the edges. (That part of the study had volunteers make their own from a pattern.)

2. The ones that filter as well as surgical masks are much more difficult to breathe through, and the ones that are as easy to breathe through don’t filter as well.

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/258525804_Testing_the_Efficacy_of_Homemade_Masks_Would_They_Protect_in_an_Influenza_Pandemic#pf7

Since my wife is a hospital medicine doc at a hospital that is short of supplies, a friend and I have been working on masks. She has made both the rectangular pleated and the ‘Fu Face Mask’ types.

1. At least for the mid-weight cotton fabric we have used, an easy way to test is to wet the fabric thoroughly; it is then nearly impossible to breathe through, and leaks are easily detectable. (The fabric is breathable again as soon as it dries.)

2. The primary failure mode of both mask designs seems to be leakage on either side of the nose.

3. It isn’t hard to fashion a nose bridge to shape the fabric to the skin. License plates are made of a soft aluminum alloy and about the right thickness. They can be cut with a good pair of scissors.

4. I formed the metal with my fingers, then attached with VHB outdoor-rated tape, but it might be more durable to sew them on to the outer layer of fabric with embroidery thread (best to let the inner layer free, as it sort of sucks in against the face and improves the seal on inhalation).

This seems kind of important to leverage the efforts of many crafty types who are making masks; I’m not a social media person so not sure how to better promote.

Hi Quercus,

I really want to get involved in this. I’m working on a website to bring together some patterns and instructions (mainly to make it easy to download and print), what we know about which design and materials are effective, how to find places to donate them to, etc. Basically trying to make this info available in one place so people don’t have to search for it.

I sew, but I live on a boat, and I don’t have an iron or any idea how to set one up safely. I plan to make a few masks to learn how, and then focus on writing up what I’ve learned and spreading it around. I’m not really a social media person either, but I know how to set up a website and could probably figure out how to make infographics that are easily shared and stuff. (I’m a programmer, and past hobbies have involved WordPress and photoshop)

It would be really helpful to be able to consult someone who’s producing lots of masks and “gets” the rationalist/ea/whatever approach to things. If you’re willing to chat about it, would you mind sending me an email so we can connect? My email is my username, at Gmail.

Vacuum cleaner bags have tiny pores (better than other materials except surgical masks, but not enough for virus particles).

You can use the existing seams to create a shape with a large surface to breathe through (less pressure and less airflow per area! => easier breathing, lower pressure differential between the mask area and gaps around it!).

If the material has a minimal stiffness, you might end up with something in the shape of a beak or snout (and look like the plague doctors in medieval woodcuts 🙂 ).

ETA: Don’t make big volumes or the wearer will only re-inhale their own exhalated volume… Evolution a work 🙂

ETA2: One bag for in- and one for exhalation, a valve, and something like a snorkel’s mouthpiece? 🙂

Early Modern woodcuts. There are such things as Late Medieval woodcuts, but there are no beaky plague doctors in them, that was a later era.

Thanks!

That’s what I really love about SSC — expose some dumbness and be not allowed to go uncorrected!

I think this is exactly the only right and relevant question at this time. The remainder of the discussion is just noise. Everyone agrees “that surgical masks help prevent sick people from infecting others”. Whether they also protect you is irrelevant: you have your priorities wrong if that’s what you are arguing about (sorry Scott, from a technical point of view this is again a very interesting article, but it’s just not important at the moment and any subsequent discussion about its contents is currently just noise)

> Whether they also protect you is irrelevant

huh. Irrelevant to what?

I personally would like to know, for myself and for others, whether they do protect you. And I’m pretty sure they do. A bit. But I’m happy to get some measure of confirmation.

Sorry, “Confusion”, if my concerns for the protection of myself and those close to me are “just not important”. No, actually: not sorry.

It’s irrelevant whether they protect you, because if we all agree they protect others against you, then everyone should already be wearing them. Arguing about whether they also additionally protect you is a distraction. If you worry about your health, you should be focussing on getting everyone else to wear a face mask. Listening to your selfish impulses and not taking the outside view leads to the wrong priorities that do not lead to an optimal outcome for you.

That is not correct. The result of my listening to my selfish impulses and acting for my own self interest is the optimal outcome for me, although not necessarily for the world.

If advising other people to wear face masks reduces the risk to me by enough to be worth the effort, then my selfish impulses will lead me to do it. My guess is that it doesn’t — the number of people I would persuade, if any, would be such a tiny fraction of the population around me as to have an effect on me very near zero. That’s the usual public good problem.

Insofar as you have an argument, it is that my unselfish concern for other people is a reason to wear a mask, not that my effect on them is a selfish reason, which is what you are claiming.

Even if I have a concern for other people, I also have a very strong concern for myself, so whether the mask protects me is and should be relevant to my decision. Furthermore, whether a mask protects the wearer is relevant to whether I should urge those I care about to wear one, for both their good and mine.

That is a real world issue. In a few days, my daughter is going to do the shopping for the household, being a good deal younger and less at risk than either of her parents. Scott’s essay strengthens the argument for her wearing a surgical mask while doing so. I don’t want her to get sick, and I don’t want her to get us sick.

> If advising other people to wear face masks reduces the risk to me by enough to be worth the effort, then my selfish impulses will lead me to do it.

If those impulses do that for you, good for you. They don’t for kaicarver, whose selfish impulses lead them into the temptation of the availability bias, thinking that anything *they* can do right now, independent of any others, is necessarily the best thing to do. And I think you’re making the same mistake below.

> My guess is that it doesn’t — the number of people I would persuade, if any, would be such a tiny fraction of the population around me as to have an effect on me very near zero. That’s the usual public good problem.

Then you’re trying not very hard? Since I know you’re a smart person, you could come up with something and since you haven’t, you’re not trying very hard. Why not? Because you have fallen prey to the same availability bias trap, exemplified by saying “Scott’s essay strengthens the argument for her wearing a surgical mask while doing so. I don’t want her to get sick, and I don’t want her to get us sick.”

Let me suggest this: have her take a stack of masks to the shop and hand them out (from an appropriate distance), asking everyone to wear them while she is shopping. If you get even 1% of simultaneous shoppers to wear the mask, she’s much better protected than by wearing a mask herself.

I’m sure there’s about 15 other things you can come up with.

Argument by assertion. Would you like to offer some back of the envelope calculations to justify it?

Assumptions:

* we’re talking about makeshift masks (most don’t have decent masks)

* makeshift masks are > 75% effective at stopping spread of droplets in air expelled by wearer (see various links floating around here)

* makeshift masks are < 1% effective at stopping droplets in air inhaled by wearer (that's how I interpret Scott for this situation)

* n shoppers

* base chance a shopper infects you is p (captures how many are infected, their behavior, anything related to how likely they are to infect you)

* all shoppers independent

With no masks, odds of not being infected are (1 – p)^n

If you wear a mask, the odds become (1 – 0.99*p)^n

If 1% of the shoppers wears a mask while you don't, the odds become (1 – p)^(0.99n) * (1 – 0.25*p)^(0.01n)

For p is 0.01 (absurdly large) and 100 shoppers this gives 0.366 vs. 0.370 vs. 0.369

So my 1% was an underestimate: you need to convince 2% to beat the effect of wearing a mask yourself (0.372).

So convincing only one other person to wear a mask confers the same magnitude of benefit to you as wearing one yourself.

For transparency some more numbers:

* If you believe makeshift masks are 10% effective to the wearer, you'd need to convince 14% to wear a mask for the benefit to be larger than just wearing a mask yourself.

* If you believe makeshift masks are only 50% effective to the environment, you'd need to convince 3% to wear a mask.

* If p = 0.001, this whole mask business becomes a lot less interesting, providing only marginal benefits (~0.001 change)

So these numbers are somewhat sensitive to what you believe about the effectiveness of masks and your base chance of getting infected.

If it's a store with 10 people and handing out nice artisanal masks gets 5 to don one, well, that seems like a good trade off to me if you're serious about being afraid of getting infected.

This is kind-of orthogonal to your discussion, but I’d be worried about taking a mask from someone else. If they are an asymptomatic carrier and got virus on the inside of the mask, I’m putting that on my face and inhaling through it, which is pretty much optimal for getting the virus.

Before getting into details …

What you wrote was:

You now have shown that, if you put in a bunch of conjectural values, she is twice as well protected by wearing a mask herself. Note your confident “much better protected” in the other direction.

The mask my daughter will be wearing is a commercial surgical mask, several of which we happen to have. Nothing in our previous exchange implied that she would be wearing a makeshift mask — that was pure invention on your part.

I have no idea where you got that number. Scott cites a variety of different studies of surgical masks. Among other quotes:

All of which suggest an effectiveness one to two orders of magnitude greater than the one you assumed. Feel free to redo your calculations with those numbers.

And very sensitive to the assumption you made that the mask has almost no protective effect, the assumption that Scott just spent a long and detailed post refuting.

Irrelevant to what the policy recommendation is. The correctness of the social policy is independent of whether it’s the wearer or the people around them that benefit. In either case you should equally support things like stores requiring mask use inside or fines for not wearing masks while outside as measures to prevent the spread of infection. So if the question is “should the cdc recommend mask use” whether they protect the wearer seems irrelevant (given a fixed total protection effect size, the distribution of that protection to wearer vs others is irrelevant).

1. Why do you assume a fixed total effect size? One of the things determining the total effect size is whether the mask protects the wearer and by how much.

2. One way of getting people to do something is to show them that it is in their interest. If wearing a mask protects me, that may not be a better reason for you to order me to wear a mask than the same amount of protection for other people, but it is a much better reason for me to choose to wear a mask, given that I am not totally altruistic.

So the CDC is much more likely to have its recommendation followed if the mask protects the wearer than if it doesn’t.

@DavidFriedman

> So the CDC is much more likely to have its recommendation followed if the mask protects the wearer than if it doesn’t.

Saying “much more likely” overstates the case, and even “more likely” is only true if all else is equal. My impression is that you are less influenced by peer pressure than most people, and thus are underestimating the strength of public shaming. If a CDC campaign caused people to shame people who didn’t wear masks in public, people’s desire to avoid this shaming might have an even stronger than self-interest.

Consider the parallel of public spitting. Despite possibly being a benefit to spitter, and despite still being acceptable in some other cultures, in the US it’s strongly looked down upon to spit in public. My impression is that much of the current US attitude is the result of an successful intentional public health campaign against tuberculosis: https://www.mentalfloss.com/article/561579/tuberculosis-anti-spitting-campaigns.

One could argue that this is still the power of self-interest, but it’s the self-interest of those who want not to be infected. If a majority of the public became convinced that their safety was improved by having others wear masks, it seems quite likely that mask wearing could quickly become the norm. If you add in some criminalization or liability for non-mask wearers, the self-protection aspect of masks (or lack thereof) would probably only be a rounding error.

@DavidFriedman

I’m not saying the effect size actually is fixed, I’m saying that the apportionment of the benefit between wearer and others doesn’t matter to policy. Obviously when the benefit is B= X + Y a higher Y increases B, but this article seems to disproportionately focus on Y when X is obviously meaningful and positive so we already know B is meaningful and positive, Y being 0, small and positive, or large and positive doesn’t affect the correctness of a policy of “most people should wear masks”.

Honestly I just don’t believe this. Flu vaccination rates are like ~50%, and it seems very doubtful masks will have a better rational expected value than that. On the other hand, Masks are obvious and visible so a campaign of “people who don’t wear masks endanger you and your children” seems drastically more likely to actually produce compliance because selfish bystanders will help produce that compliance, instead of ignoring violators that “only endanger themselves”.

Is your unstated assumption that as long as B is positive, most people should wear masks, however small B is? Without that your conclusion doesn’t follow, since B+Y could be large enough to justify the policy even if B was not.

Your further argument seems to be:

There are both self-regarding and other-regarding reasons to get flu shots.

Many people fail to get flu shots.

Therefor self-regarding reasons are less important than other-regarding reasons as motives for behavior.

Am I missing something in the logic of your argument?

@david.friedman

Part 1: the context here is basically that the article spends the vast majority of the time on the question of “do masks protect the wearer” when “do masks protect others” is equally important from a general policy perspective (medical personnel/hospitals obviously have justifiably different policies). The only mention of outgoing protection I see is

And by corollary to recommendations to “sneeze into your sleeve” masks seem like essentially a better version of that. Studies that look only at protecting the wearer are going to underestimate total protection from wearing masks and so aren’t asking what’s ultimately the more important question when talking about a policy of “should random asymptomatic people wear masks” (as AFAICT nobody actually disputes them being valuable for medical personnel).

Yes, this is not my argument at all. My claim is that if a central authority gets to make one claim about masks that saying “masks protect others” will reduce in higher mask wearing rates than “masks protect the wearer”, primarily because “masks protect others” spreads itself far more aggressively. “Masks protect others” leads to self interested people demanding that all the people around them wear masks and shaming those who don’t. It’s not about whether the actual motivation for someone to put a mask on is “selfless” (not get other people sick) or “selfish” (protect oneself / not get yelled at). Emphasizing “protect others” also seems more likely to lead to things like stores requiring shoppers wear masks (because more shoppers may demand it as a policy than don’t want to wear masks).

Consider public attitudes towards riding a bicycle without a helmet vs drunk driving. I think drunk driving has a much stronger negative association due to risk-to-others regardless of the underlying actual risks.

The flu vaccine part is a sidenote to establish why I don’t think rational self interest will lead to extremely widespread adoption of medical interventions, even when those interventions have a clear selfish benefit.

If so, it is equally evidence that concern with effects on others will not lead to widespread adoption, since the flu vaccine protects both you and others.

Which was my point.

@DavidFriedman

You’re still not actually engaging with my argument about why I don’t think “the CDC is much more likely to have its recommendation followed if the mask protects the wearer than if it doesn’t.”

I’m saying that “masks protect others” would be a more effective CDC proclamation because it would get people to selfishly make other people wear masks, not that “selflessness” would produce more mask use than “selfishness”. If the CDC tells people that you can wear a mask to protect themselves, selfish and rational people will wear a mask. If the CDC tells people that wearing a mask “protects others” selfish people will make other people wear masks (while presumably also wearing one themselves to not look hypocritical).

A pure altruist should wear a mask regardless of who it protects (because protecting yourself prevents you from spreading the illness as well) so they aren’t really an interesting part of the dynamic.

Maybe our confusion here is on what it means for the CDC to have its “have its recommendation followed”? My understanding of that it’s something like >60% of people wearing masks, and I just don’t see that happening without socially enforced compliance. Because I see socially enforced compliance as being primarily influenced by the degree to which people think “masks protect other people”, I am skeptical that direct self-protection is a significant factor.

Note that one issue with the flu vaccine is that it doesn’t provide very good protection–it’s what we have, but it’s a pretty lousy vaccine. Compare with most other vaccines (MMR, polio, etc.) which are very effective. If flu vaccines were better, it would make both the individual and collective case for getting them stronger.

I mean, my family and I get our flu shots every year, but the protection is better than nothing, and that’s about all that can be said for it.

My claim is that if a central authority gets to make one claim about masks

Why would a central authority with any sense make only one claim? “It’s safer for you and safer for everyone else.” “You’re less likely to get it and less likely to spread it.”

@albatross Where are you getting your “flu vaccines aren’t very effective” information from/what does that level of effectiveness actually mean to you? The CDC reports something like 50% reduction in flu infections and an additional ~60% of decreasing severity in the event of an infection (e.g. ICU rates of hospitalized patients). Neither of those effects is as high as MMR effectiveness, but it feels like underselling it to say they’re only “better than nothing”.

@Roger Sweeny

Obviously the CDC gets to make multiple claims but they have limited time, people have limited attention spans, etc. So their website should always have mostly the full information, but increasing the message length isn’t free, and I’m arguing that emphasizing social benefits is a better use of that budget than personal benefits so it should be spent something like 80/20 on the social benefits. This is in contrast to DavidFriedman who I interpret as saying the personal benefit is more important (but maybe he means they’re equally important and either gets 40% of the population to mask up, this both together is 80%).

But what the CDC has actually been doing is using part of their limited budget of public attention to tell people that there is no private benefit — to lie about the facts.

I assume that both private and public benefit are motives to wear masks. But the CDC never, I think, denied the public benefit, so Scott sensibly focused on the private benefit. That’s important both as one significant incentive to wear masks and as evidence that statements by the CDC ought not to be trusted.

I think the “masks don’t help much” position is common among health professionals in the US. The TWIV guys (academic virologists doing a podcast) have all said the same thing–they don’t think wearing surgical masks does much good at keeping the wearer safe. I suspect they’re somewhat wrong in this case–it probably does some good if only by reminding you not to stick your pen in your mouth or scratch your nose–but it’s not a slam-dunk. For really small airborne droplets, a surgical mask or homemade mask is probably better than nothing but that’s about it. OTOH, it seems really useful for slowing the spread of COVID-19 if everyone wears them, because it seems like most transmission is probably happening from big droplets coughed/sneezed out onto surfaces, and a mask is going to catch most of those. They had a guest (an infectious disease doctor) who more-or-less said that in a fairly recent episode. Though ironically, I haven’t listened to TWIV or other podcasts much lately–that was what I did at the gym, but the gym is closed now.

I doubt that the TWIV guys were worried about causing a run on masks (how many people listen to academic virology podcasts?) and were engaging in a noble lie. I think they were repeating common wisdom among medical personnel in the US, which may or may not be right but isn’t an intentional lie.

There are years where the strains predicted for the flu shot were completely wrong, and years where the flu shot manufacturing was botched up and vastly smaller amounts were produced. If you look at y-o-y flu deaths you could never guess which years those were.

I get the shot, because why not?, but it’s not that great. The people working on it are much smarter than me, that’s not the issue. They are just working on a problem that is much bigger than them.

If you think you can get anyone to wear a mask by telling them it will prevent them from getting infected, you will have as much success as you have by telling them they shouldn’t go the bar tonight.

Many people *have* stopped going to bars and other public places. Not everyone, but a lot of people.

It seems like the only world you find acceptable is the one where everyone wears masks but purely for altruistic reasons. I’m willing to settle for the world where more people wear masks than they do now, even if it is for selfish reasons.

“Confusion”

Nominative determinism strikes again.

Datapoint: My wife and I stopped going to restaurants and coffee shops several days before they were all moved to carry-out-only. The last time we went out to lunch together, the restaurant we went to was almost empty.

@Nathaniel: no, the world I’m going for as one where everyone wears masks. I don’t care about the reasons they have for wearing masks.

I am pointing out that people are misleading themselves by arguments from a naive sense that they are allowed to be selfish, which result in them not sufficiently examining what would be optimal if they truly cared about their well being.

I won’t speculate about the reason for the discrepancy between what they claim to want and what their behavior shows they want, but what would Robin Hanson say?

What do you think the strength of this evidence will look like compared to the evidence for the flu vaccine, which only had about 50% coverage for US adults? It seems far more likely that mask usage would reach high levels due to shaming / social norms which I’d personally guess are easier to form when not having a mask mostly endangers others.

This is also my takeaway. I’m a reasonably young, reasonably healthy person (at least as related to COVID-19 risk) living in a large multifamily building with many older and less healthy folks. It sounds like making some sort of fabric mask from an old pillowcase or whatever is unambiguously the correct thing to do, and the rest of the post is interesting but for me, not actionable. I wish my home’s craft supplies were better stocked.

I agree. There are a lot of DIY mask tutorials out there by now. Some use very little craft supplies, for example, I’ve used stapling instead of sewing and it works just fine.

However, WHO says:

I wonder why is that.

I assume it’s a “not recommended” vs “recommended against” thing, but I’m confused on why they don’t word it as “only minimally effective” if that’s the case.

coming from hong kong where the topic of masks has been discussed at length over the past couple of months, here are some things we’ve learned:

– wearing a mask is a good idea if supply for healthcare workers is not a concern. this is especially important since asymptomatic covid carriers abound (and hong kong is a dense city). another upside is that it encourages those who are sick to wear a mask without the fear of being identified or stigmatized, and in turn becoming unknowing transmitters.

– for diy masks to be meaningful, they need to mimic the protection of surgical masks.

typically, a three-layer surgical mask has a waterproof outer layer, a middle layer that filters tiny bacterial and viral particles, and an inner layer that absorbs the moisture exhaled from the wearer. both the outer layer and the inner layer are to protect the middle layer from getting wet and becoming a conduit for bacterial and viral particles to pass through, defeating the purpose of the mask.

therefore, diy masks would need to be able to keep the filter cloth dry for it to do its work. one way of doing so, though un-elegantly, is to wear a full-face visor at the same time and adding a tissue between the mouth and the filter cloth for moisture absorption. the filter cloth can’t be too porous either, otherwise the tiny viral/bacterial particles can still pass through.

– as another commenter suggested, having a mask on helps keep people from touching their faces, which is important as well.

so, if masks are available, by all means wear one. or make one that works well.

Would a single layer of cloth help reduce an infected wearer infecting others?

for an unknowingly infected person, a cloth mask may reduce droplets from spraying all over during coughing or sneezing, but it may not be enough to block covid droplets given their minute size. some people who make diy cloth masks insert a piece of non-woven fabric (like a dried wet wipe or even an air-conditioning filter) in between cloths as the filter to mimic surgical masks. that seems like a better option.

separately, the WHO has published some guidelines on mask use that is a good reference:

https://apps.who.int/iris/rest/bitstreams/1272436/retrieve

Yes!

1) Almost any mask will create turbulence and therefore prevent your breath from spreading as far, generally. This is a Big Deal.

2) Almost any mask will serve the crucial role of interfering with coughs and sneezes (which can literally travel 20-30 FEET!)

3) Most fabric masks will catch the largest droplets (which contain the most virus and are the most dangerous) and

4) Most masks have a psychological aspect which may keep you focused on transmission issues.

FYI: If you really have to cough or sneeze and you’re not wearing a mask, the safest way to protect those around you is NOT using your sleeve. It’s to pull out your neck and sneeze/cough down your shirt. Yes, it’s a bit gross but is highly effective.

Thank you, this makes sense.

“People may get infected by the virus if they touch those surfaces or objects, and then touch their mouth, nose or eyes.” (from covid19.govt.nz) – does that imply that to be completely effective a mask would need to cover your eyes as well as your mouth and nose? Or is direct contact infection significantly different from aerosol infection?

If it’s a true aerosol situation, you’d want a full face respirator.

If it’s respiratory droplets, but you’re worried about it getting in your eye/nose, you can wear a mask under a face shield.

As long as you don’t touch your face, a mask should protect against respiratory droplets just hanging in the air/directed towards your mouth.

On the ambulance, we have PPE kits that comprise a respirator, a face shield (to protect the eyes), a gown, and gloves.

But that only protects against droplets, not airborne risks for which you would need a CBRN mask (also currently sold out).

This post correctly notes that there is a nationwide shortage of N95 masks. Most worldwide supply is currently spoken for, though production is rapidly ramping up.

But it may surprise you (or may not, depending on how much pre-existing cynicism you have about the regulated nature of the healthcare industry) that there are millions of *exactly equivalent* masks sitting around, in stock, ready to be bought, that are not being utilized. These are “KN95” masks. These have basically identical specifications, here is a writeup by 3M: https://multimedia.3m.com/mws/media/1791500O/comparison-ffp2-kn95-n95-filtering-facepiece-respirator-classes-tb.pdf

KN95s and N95s are in fact, often manufactured in the same factories. But the difference is that production of N95s are ceritifed by the US FDA, whereas production of KN95s are certified by the equivalent Chinese regulatory agency. This detail makes no difference in how well the masks protect against COVID19, but ensures that essentially no hospital in the United States can buy them. CDC just issued guidance last week recommending that hospitals consider masks of equivalent international specifications: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/hcp/respirators-strategy/crisis-alternate-strategies.html, but I have yet to encounter a single hospital purchasing department that has adapted to this recommendation.

The N95 shortage is so acute that I have heard stories of nurses, sometimes over 60 years old and vulnerable to COVID19, going into ICUs to treat confirmed COVID19 cases with only a surgical mask. Or with a single N95 mask that they re-use every day (official guidance is to swap these out after every *patient*), despite no clear reliable way of sanitizing them.

The shortage of N95s while millions of functionally-identical but legally distinct masks sit in warehouse struck me as so galling that I decided to just raise money to buy KN95s from China and then distribute them to US hospitals, usually giving them directly to doctors and nurses since the hospital administration officially deals just in FDA-approved equipment. I apologize for probably breaking some rule about promotions and perhaps getting this comment deleted, but I’ll risk it because this is worth it; you can donate here: https://www.gofundme.com/manage/kn95-masks-for-impacted-hospitals . I have so far raised enough to order 60,000 masks and, if I just had the money, have the ability to purchase many hundreds of thousands more.

I am effectively doing the exact same thing for the exact same reason. I have several sources for KN95’s (which Scott should address in this post) and am buying and distributing as much as I can. My company is going to do a “Masks for All” coin as a fundraiser (we make coins/belt buckles usually). We’ll sell you a coin and buy several masks with the proceeds and distribute them. I learned about the differences on my many trips to China over the years and couldn’t believe that during the present shortage, many hospitals would rather reuse (without sterilizing) K95’s than use KN95’s. It has been my personal online crusade on Facebook (ugh) trying to convince people that the masks that are 3X less expensive and readily available are likely as good or at least ALMOST as good as the ones that no one can get.

Also look for R95/R100 and P95/P100. I’ve had luck finding those even while the N95 masks are months backordered. I’d much rather wear a P100 than an N95 for virus protection

Yeah, it seems a lot easier to get the seal to work on my P100 mask than on the N95 mask I wore to the store last time I went. I may just go with the P100 mask next time, though it will look extra weird. I guess I’ll wipe off the surfaces with a disinfectant after going out with it.

I think you’ve put in the wrong link – https://www.gofundme.com/f/kn95-masks-for-impacted-hospitals works for me (note the “f” in place of the “manage”).

Thank you for the correct link, I may have given up otherwise!

argh, thanks so much for fixing this!

I am donating today. Please update when you have begun distributing masks and confirm that healthcare staff are using them and report what your turnaround time is from purchase until the masks are in use. I’ll likely make another donation at that point.

If anyone else has commentary on why we should or shouldn’t donate here, or a recommendation for a more effective donation, please post!

Thank you very much! The first shipment will arrive Friday or Saturday, and I will be sending an update to the page when this happens.

I think this is at least partially inaccurate. Here is a great summary from a LessWrong thread: https://www.lesswrong.com/posts/7K8fSFTnpfN4EBuZ8/how-useful-are-masks-during-an-epidemic?commentId=DAJTniy2swhdtiZdh

Hey there –

I admit I’m not an expert on industrial mask design and can’t address all the specific engineering points. But I have learned a few things from my research talking with both physicians and medical import/export companies.

– “industrial vs. medical” is orthogonal to “KN95 vs N95”. There are industrial grade KN95 masks and medical-grade KN95 masks, just as there are industrial grade N95 masks and medical grade N95 masks. Of course, medical-grade KN95 masks are pretty much only sold and used in China. I’m just speculating here, but maybe US industrial users routinely buy KN95 masks because they are a bit cheaper, whereas hospitals never do, which is why the commenter thinks all KN95’s are industrial-rated?

– Note also that FDA just issued guidance last week for hospitals to go head and use industrial-grade N95 masks if they have to, extending liability protection to those manufacturers.

– the point this comment raises about moisture is absolutely true, and common to hardware-grade masks of both the KN95 and N95 varieties. It’s definitely a compromise that is being made with the short-term use of hardware-grade masks in medical settings.

– fit is also orthogonal to the KN95 vs. N95 distinction – there are masks in both categories that either have multi-size fits or attempt to be one-size-fits all, the former being better and safer but, of course, requiring you to track and order multiple SKUs.

Hi @mlinsey , we have a few nursing homes which need masks, and may be interested in buying if they can arrive fairly quickly.

How can I get in contact with you?

Scott please delete this, thank you

Over here in East Asia, it is generally believed that one of the main benefits of mask use is that is stops people from touching their face, nose, and mouth (this is critical!), in addition to the limited protection a mask itself might offer.

And the common wisdom over here is that surgical masks work. Period. The government wants everyone to wear a mask, even if you have to put it on a clothesline for a day after use. Which is why… I found the the back-and-forth in the US rather amusing.

It is not improbable that the CDC foresaw the possibility of future shortages of medical equipment, and intentionally geared their policies to prevent excessive demand three years in advance. After all, all these pandemics aren’t exactly super-unprecedented, and well, everyone knew this sort of thing could happen.

I don’t find the situation in Asia very compelling evidence. That is, it’s just as likely that east Asian society is blind to scientific fact as that western society is.

In particular, isn’t mask-wearing pretty common in east Asia for reasons unrelated to germs, namely seasonal dust storms (so I’ve heard, unconfirmed)? That would reasonably bias people to support evidence that masks have other positive effects, since they’re wearing them anyways so it’s low risk.

Lots of mask use due to scooter use and general traffic congestion, but also superstition after SARS. Well superstition is a strong label, people just accept it because it has become the norm. But the rationale that made sense to me is that covid19 spread via respiratory particles, and mask reduce the viral load over time, which reduces risk of infection and severity since your body will have more time to recognize the infection and ramp up antibody production much earlier in the virus’s exponential growth cycle. Reduces R0 when ubiquitous, almost like cheap heard immunity.

I think the country to observe is Japan, fairly ubiquitous mask usage, by all accounts they’re under-testing to suppress numbers so Summer Olympics doesn’t tank (except it just did), but also they should have been overwhelmed like Italy by now, that level daily death – military trucks convoys shipping coffins – can not be hidden. Instead, ground reality doesn’t appear starkly different than Korea or Taiwan. I think there is a chance that China over reacted because it had to, there was so much unknowns early in the outbreak. But seems like all the countries that are doing well right now have ubiquitous mask usage and hygiene due to past SARS experience. That or because they’re functionally islands and can easily shut down their borders.

There are far fewer cases and deaths in Japan now as compared to Europe despite the disease having arrived there earlier and the fact that life has shut down to a lesser degree with people still riding crowded subways, etc. Of course, other factors could contribute (bowing instead of kissing on the cheek), but it makes sense that if it’s spread by coughing, sneezing, etc. widespread mask wearing would significantly slow the spread even if not that useful for each individual.

I think mask wearing is more or less ubiquitous in SE Asia, and that is where you find the countries that have been able to curb the pandemic. This is circumstantial evidence, but it is one more thing to consider.

Actually, people wear masks during exam season, so their performance during and immediately before school exams doesn’t get screwed over by a cold or something.

Some people wear masks when air pollution is particularly bad, but that isn’t common at all.

All sick people are expected to wear masks in my corner of East Asia; to not use a mask while obviously sick is considered very rude.

And as usual many Americans and Euros in East Asia don’t wear masks even when available and walk around scaring the bejesus out of the rest of us.

This does not match my experience with face masks. I wore a face mask last time I was sick, and I felt like I touched my face more often, in order to adjust the comfort level. I suppose I might have touched my mouth less often, but nose and face seemed to be very often. Maybe I am just atypical and was doing it wrong?

I had the same problem initially; I also found it difficult to breath at first. Somehow you get used to it and it doesn’t seem so bad. That said, while it may possibly be a wash in terms of risk for many individuals (lower chance of inhaling virus offset by higher likelihood of touching your face to fix your mask or feeling of safety conferred by the mask causing you to be less cautious in other ways), I’m pretty confident it’s highly beneficial when almost everybody using e.g. public transportation is wearing. Imagine how many people could get infected by one uncovered sneeze on a crowded subway; not just because they might directly inhale, but because the saliva can alight on surfaces people will touch.

It seems to me that respiratory viruses have clearly evolved to take advantage of our bodies’ reflexes to expel crap from our respiratory systems by coughing and sneezing. That’s how they get a free ride to the outside, and from there to other bodies, either directly or by landing on something people touch. Effectively covering everyone’s coughs and sneezes in public seems to throw a major wrench in that.

“amusing” is one way to describe it. I would describe it as infuriating and terrifying. I feel like western society is too disorganized and selfish to get this thing under control any time soon. It seems like it’s going to just keep spreading until half of us all get sick, one way or another.

Here’s some top Korean doctor on infectious diseases saying masks are effective and that he’s not sure why the CDC saying differently except possible because of trying to prioritise masks for medical staff

https://youtu.be/gAk7aX5hksU

In Japan many people wear masks for hay fever.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hay_fever_in_Japan

For what it’s worth, Chinese National Health and Medical Commission recently posted their official guidance on mask usage. The cat meme is because someone reposted the article on Chinese Quora. Use Google translate. Normal surgical masks is recommended for almost all circumstances N95+ for specific personal and exposure. The only situation where no mask is necessary:

Also, relevant interview with microbiologist Yuen Kwok-yung, “key figure in identifying and arresting the spread of the Sars pathogen that ravaged Hong Kong in 2003”, and one of the expert group who was sent to Wuhan at the beginning of the outbreak:

Give

+1

The burden of proof is on organizations like the CDC telling people that wearing masks is “not recommended”. Unintuitive advice requires justification, since when none is forthcoming, credibility is diminished.

If there is a well-founded concern about supply, at the very least you would think that DIY masks cannot hurt, so you might as well wear them. Again, one can imagine reasons that this might not be the case, but the burden of proof lies with those imagining such reasons.

“Not recommended” doesn’t mean “recommended against,” does it?

This was Scott’s point here:

Indeed, I thought to comment on this. However, there is a reason that containers full of petrol are not labeled inflammable.

Consider not wearing a mask when driving (they can be distracting), especially an N95+ mask which can make breathing more difficult.

“When used correctly, they[respirators] theoretically offer complete protection against incoming and outgoing droplet and airborne diseases”

“Also, even respirators don’t claim to reduce particle load by more than 99% or so, and those work”

“But it would also be wrong to conclude the studies show masks don’t work, because they mostly show respirators don’t work, and we (hopefully) know they do.”

99% isn’t complete protection. Complete protection hasn’t been demonstrated, so “theoretically” is meaningless. But “we know they work” seems to depend on complete protection, or on the hope that a 95-99% reduction is enough to let our immune system do the rest – which may be less true for some viruses, perhaps especially for novel ones.

I think probabilistic elimination of viruses confers protection regardless. If 1 virus is enough to get sick then 95% won’t do much in a 100 virus environment, but will probably protect you in a 10 virus environment.

I think there’s also some complicated biology things where case development can differ based on number of viruses in the initial exposure – see e.g. https://ccforum.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s13054-019-2566-7. So getting 5 virus instead of 100 may lead you to still get infected but have milder/no symptoms.

If the anecdotes about many deaths in the medical profession are true, it seems quite likely that the number of virions you are exposed to counts.

I suppose it might also depend on *how* you are exposed to them. What if ingesting some viruses to your digestive system might let your immune system get acquainted, whereas they only do harm when they get into your lungs? (Purely speculative hypothesis.)

This seems awfully likeky to me too–young, healthy healthcare workers might not get badly sick if they rode the subway next to one sick guy once, but spending 12 hours a day in a roomful of very sick people, sleeping on a cot in the hospital and reusing their mask/gown the next day to conserve supplies, they’re getting a ton of virus exposure, all the time. Also probably getting many slightly different strains of the virus at once, which might matter.

Robin Hanson is speculating along these lines and has some additional studies where initial dose seems a strong determinant of long term outcome. The home vs public exposure piece is very speculative though, it’s not clear how it changes if the larger dose comes cumulatively over a 24-60 hour period.