From a recent Charter Cities Institute report:

From India’s independence from the British Raj in 1947 to the early 1990s, the country’s economic policy was largely socialist. In the 1980s some early steps were taken to open the Indian economy to increased trade, reduce controls over industry, and set a more realistic exchange rate. In 1991, more widespread economic reforms were introduced. These reforms included the end of government monopolies over certain sectors of the economy, reductions in barriers to entry for new firms, increased foreign investment was allowed, and tariffs and other barriers to trade were reduced or eliminated. After liberalization, exports increased substantially, and various service sector industries saw significant growth.

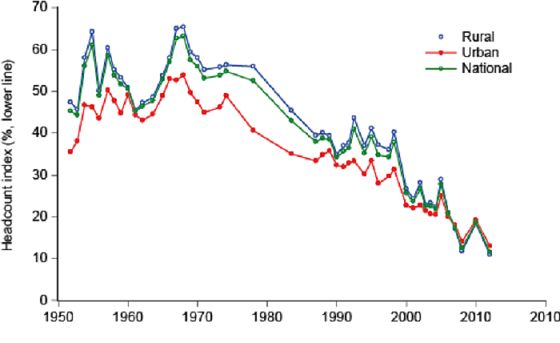

India’s growth has not just been good for the more educated segment of the population. Datt, Ravallion, and Murgai (2016) argue that India has made substantial progress in reducing the incidence of absolute poverty, and that this trend exists in both urban and rural areas. Historically higher rates of rural poverty have been converging with urban rates of poverty, and the overall poverty rate has been declining at an accelerating rate in the post-1991 reform era. In the 1970s over 60 percent of Indians were living in extreme poverty. As of 2011, only 20 percent of the population lived in extreme poverty. Between 2005 and 2016, an estimated 271 million Indians rose out of multidimensional poverty, which accounts for various health, education, and living standard indicators rather than just income (UNDP and OPHI 2018). Infant mortality has fallen from 161.4 deaths per 1,000 births in 1960 to just 32 deaths per 1,000 births in 2017, and India should soon converge with the world average if the current trend continues. Life expectancy has also improved dramatically, rising from 41 years in 1960 to nearly 69 years today. Like with infant mortality, India is close to converging with the world average in life expectancy. Literacy has improved from just 41 percent in 1981 to 72 percent in 2015, an increase of 75 percent. Here too, India is converging with the world average. Female literacy in particular rose from just 25 percent in 1981 to nearly 60 percent in 2011, and female primary school enrollment has increased from 65 percent in 1990 to over 98 percent today. Across the board of development measures, India has made tremendous strides.

Reading this surprised me. I was vaguely aware that India had done relatively well, but I didn’t grasp the scale. This should be up there with the rise of China as one of the most important (and most encouraging) news stories of my lifetime. And if it was really due to the 1991 reforms, they should go down alongside Deng Xiaoping’s liberalization of China as one of the century’s great achievements.

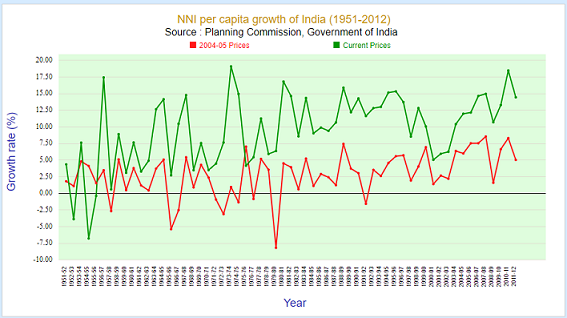

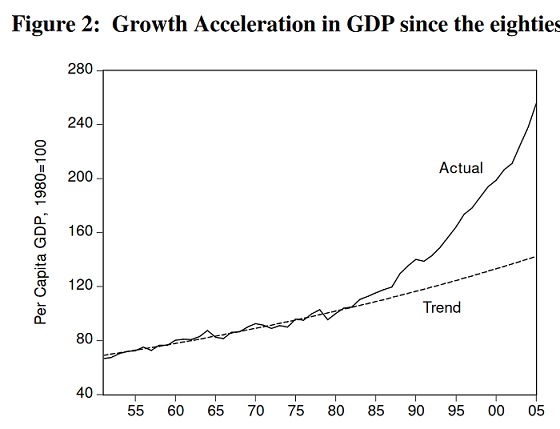

Looking into it further, the progress against poverty is on firm ground, but the attribution to the 1991 reforms is controversial. Here’s India’s rate of GDP growth over time:

And here’s its poverty rate over time:

Neither looks like much happened in 1991. Both show, if anything, gradual progress from around 1980. Kotwal, Ramaswami and Wadhwa have an especially clear presentation of this:

For their claim about 1991, CCI cites Indian-American economist Arvind Panagariya’s 2004 paper. Panagariya is aware that the graphs don’t back him up, and cites other economists like Brad DeLong and Dani Rodrik making approximately this point. But he argues that liberalization deserves credit for India’s growth anyway, on two grounds. First, he says that there was “stealth reform” in the mid-1980s, when reformers opened the economy without publicizing what they were doing in order to avoid a crackdown from angry leftists. These were complete by 1987, leading to a boom from 1987 – 1991. Second, this growth was unsustainable, and ended in a 1991 crash. Only after the major 1991 reforms did India enter a sustained period of economic growth.

But Panagariya’s panegyric is founded on the growth starting in 1987; the graphs don’t support that story either. He can only note that:

It is difficult to pinpoint the timing of the upward shift in India’s growth rate. Thus, in a recent attempt to pinpoint structural breaks in the growth series, Wallack (2003) is able to achieve at best partial success. She finds that with a 90 percent probability the shift in the growth rate of GDP took place between 1973 and 1987. The associated point estimate of the shift, statistically significant at 10 percent level, is 1980. When Wallack replaces GDP by gross national product (GNP), however, the cutoff point with 90 percent probability shifts to the years between 1980 and 1994. The associated point estimate, statistically significant at 10 percent level, now turns out to be 1987.

In other words, statistics is hard, and random upward swings can segue into real changes in trend in hard-to-analyze ways. It’s impossible to say for sure from the GDP numbers that there wasn’t a (random) boom in 1980 that gradually merged with the (real) boom starting in 1987. This works with the GDP numbers, but I find it basically impossible to square with the graph on poverty (which is from 2016 and which Panagariya didn’t have access to).

CCI also cites Datt, Ravillion, and Murgal (paper, article), which claims that “economic reforms following the macroeconomic crisis of 1991-92 marked a significant change in India’s economic landscape, ushering in a new phase of high economic growth. The growth rate of NDP per capita more than doubled in the period since 1992.” But on closer inspection, they are just comparing an average for the period 1957 – 1991 with an average for the period 1992 – 2012, and finding the latter average is higher. They make no effort to establish that the break point is actually in 1991. Since people had been complaining about this for about ten years before the publication of their paper, I’m not sure what their excuse is, other than that they’re mostly making an unrelated point about poverty and this is not super relevant.

More recent work seems to agree that there is something fishy here. Agarwal and Whalley (2013) concludes that:

We do not find persuasive the contention of manyanalysts that growth accelerated after the mid-1980s when reforms were initiated. Nor does statisticalanalysis support the contention that reforms in the mid-1980s resulted in a growth acceleration. Weshow that there is an accelerating rate of growth of GDP after the mid 1970s and it is difficult to relate this gradual acceleration to specific policy changes. The changed policies in the 1980s did not meana basic change in the policy framework. Furthermore, since corporate investment as a share of GDP did not increase in the 1980s it is difficult to identify the mechanism by which the more pro-business policies of the government were translated to higher growth.

And Kotwal, Ramaswami, and Wadhwa (2016) says basically the same:

Formal econometric tests also indicate a structural break around 1980. Using an F-test, Wallack (2003) finds the highest value of the F-statistic in 1980. Rodrik and Subramanian (2004) use a procedure of Bai and Perron(1998, 2003) and they report a single structural break in 1979. Balakrishnan and Parameswaran (2007) also used the Bai and Perron procedure and they too locate a single structural break in GDP in 1978-79. The authors also estimate structural breaks for sectoral GDP. Their principal finding is that structural break in agricultural output occurs in the mid-1960s while it occurs in the early to mid-1970s for various sub-sectors of services. On the other hand, the first positive structural break in manufacturing occurs after the GDP break in 1982-83.

Basu (2008) and Sen (2007), however, point out that GDP fell by 5.2% in 1979-80 (due to a combination of a drought and the second oil price shock). If this outlier is disregarded, then the trend break occurs in 1975-76. The average annual growth rate during the period 1975-78 is 5.8% – a rate more in line with the post-1980 experience than with the earlier period.

Is the timing of the structural break important? The discussion in the literature about the structural break takes place in the belief that it could offer clues about what policies led to the shift in the economy’s growth rate. Such inference is problematic because statistical methods alone are unlikely to provide a precise timing. Judgments about outliers, the period of analysis, and the sectors that are considered, matter. An additional complication is that policy measures do not have instantaneous results. The delay would be especially pronounced if the benefits flow from a structural change. It is therefore unwise to correlate the changes in economic variables to the policy changes that immediately preceded them. These caveats notwithstanding, the economy does seem to have moved to a higher growth trajectory sometime in the mid to late 1970s or early 1980s, well before the economic reforms of 1991.

So what did cause the Indian economic boom, save 200 million people from poverty, and accomplish an almost unmatched victory over misery and mortality? After discussing a series of possibilities, Kotwal, Ramaswami, and Wadhwa…admit that they are confused:

Although it is clear that GDP growth rates increased sometime in the ‘70s or early ‘80s, the precise timing is hard to establish and depends on one’s prior. Various explanations have been proposed and it is impossible to be sure which of these is the most important one. The economic orthodoxy would favor one that credits trade liberalization, limited as it was, that decreased the cost of capital equipment but it is hard to disentangle the effects of this from more heterodox factors such as public investment and rise in savings rate (due to bank nationalization), the diffusion of agricultural technology (entirely due to public research and dissemination) or indeed to rule out the role of political attitudes towards business. It is also indisputable that there was an unsustainable fiscal expansion through 1980’s and any income growth resulting from it should be considered qualitatively different from the much more sustainable growth that occurred in the next decade.

Of the various papers they cite, the one I find most interesting is Rodrik and Subramanian (2004). After a while describing the problem, they look at it from a different angle: which Indian states boomed first? They find it was the states most closely allied with the ruling Congress Party, and tell a story where floundering Prime Minister Indira Gandhi decided she needed support from Big Business and adopted a pro-Big-Business attitude. They do excellent work establishing the plausibility of every link in the chain of assumptions here except the one where they admit that this attitude wasn’t reflected in any pro-business policies until the late 1980s at the earliest. Somehow Gandhi’s pro-Big-Business attitude is supposed to have helped business without being reflected in any major economic reforms. Maybe it changed the way existing laws were enforced? Maybe it signalled to businesses that they should get started on long-term strategies because they could expect favorable laws in the future? Or maybe Prime Minister Gandhi just sort of sat in New Delhi, telepathically willing Big Business to succeed, and it worked? Rodrik and Subramanian are kind of agnostic about this. Everything else seems to fit pretty well, though. This might be a good time to reread Does Reality Drive Straight Lines On Graphs, Or Do Straight Lines On Graphs Drive Reality?

This is also a good time to reread The History Of The Fabian Society, because the problem might be their fault to begin with. In the waning days of the British Empire, bright young leaders from all over the developing world (including India’s Jawaharlal Nehru) came to study at Oxford and Cambridge, got inducted into Fabian socialism, went home to their newly independent countries, and pursued socialist policies. All those countries did terribly and became the Third World basketcases of today. Only over the last few decades is the damage starting to be reversed.

If we had a better understanding of what exactly happened and how it was reversed, it could be an important source of information for developing countries in the future. Also, and more selfishly, it would be an important source of information for the US. Historically-informed anti-socialism arguments have tended to hinge on things like socialist China killing 60 million people, or socialist Russia killing 15 million people, or socialist Cambodia killing 1.5 million people, or [insert other socialist regimes killing 6-7 digit numbers of people]. But nobody thinks that Bernie Sanders plans to kill a six to seven digit number of people. To respond to Bernie-Sanders-style-socialism, we need to study and raise awareness of the history of democratic, comparatively “nice” countries that did nothing worse than overregulate business a bit – and investigate whether even these best-case scenarios still doomed millions of people to live in poverty. My (biased) guess is that careful study will show this to be true. But I don’t think this study has been done, I don’t think the facts are in yet, and I don’t think it was appropriate for the Charter Cities Institute to cite Panagariya’s argument on this point without any challenges or caveats.

Yeah, I’m going to have to second other peoples comments and say this is much less than I wanted to know about Indian economic reform. Indian is very underreported in general though, so I get that it’s hard.

Another possible response to Bernie is that Nordic countries aren’t actually socialist.

https://fee.org/articles/the-myth-of-scandinavian-socialism/

You may not be aware that you’re propagating a myth with this comment.

In one particular year in the 70s, there were half as many divorces as marriages, which is where the myth began (even though you can’t count the divorce rate that way). The divorce rate has been declining for a couple of decades now.

If you’re poor, a member of certain minority groups, were very recently married, or have been divorced before, than your group has a higher “risk” of divorce. If you’re black and poor, you might hit 50%. For first-time marriages, the divorce rate is less than 30%. For college-educated, it’s less than 20%. The longer you stay married (with the biggest jump after the first few years, by far), the less likely you are to get divorced.

Now it occurs to me that there are two conceptually different kinds of policies that get cornflated under the label of “socialism”.

First, there are policies that seek to shift the balance of power from owners of capital toward workers, renters and sometimes other groups whose interests are sometimes in tension with the interests of capital owners.

Second, there are policies that seek to increase level of control which the government exercises over what gets produced in the country.

I think that India of Licence Raj, like Soviet Union, is an example of the latter, while Sanders is much more an example of the former.

In order to do the first on command, you need to do the second. Changing the rules of society requires political power. A lot of political power. All those decisions people made based on the current balance between capital and labor? “I should invest my money for retirement instead of spending it on a new car.” “I’ll go to college for my accounting degree instead of spending my life following the Rolling Stones.” “I’ll go and take out a mortgage for a new house instead of rent.” Any of those could have had a different outcome if the balance was different.

If you want to completely transform the balance of society, such redefining the concept of property or getting rid of private ownership of the means of production, it requires pretty close to absolute power in the hands of the political leadership. Absolute power corrupts absolutely. This is why even a well-intentioned communist revolution ends up with what is euphemistically written off as “state capitalism”; to make the change, and make it stick, it requires a period of absolute government power while everyone that was disadvantaged by the change adjusts to the new reality, and that’s if nothing goes wrong.

Um, no, I respectfully disagree.

“State capitalism”, which is synonymous with centrally planned economy, is an illustration that when one is taken to the extreme, those two conceptions of socialism are incompatible. Soviet system was an extreme example of socialism as government’s total control of production, and it required disempowerment of workers, so independent unions and strikes were illegal in the USSR.

Changing the balance of power between workers and capital owners doesn ́t require increase of government power beyond what it already has in modern society, i.e. what is somewhat misleadingly called “State monopoly on violence”. As long as disputes between citizens are mostly resolved by courts and not by private violence, changing the balance of power between groups requires merely changes in what claims are accepted as valid by the justice system.

You can gradually over time shift the balance somewhat; that’s why I specified ‘on command’.

The total value of the US Stock Market is around $30 trillion dollars. If you’re going to require all companies to give a percentage of their stock to workers (I’ve seen numbers for Sanders proposed Democratic Employee Ownership Fund between 40-60%), that’s moving roughly $15 trillion dollars. Yes, the government probably has the legal authority to move $15 trillion, just as it has the legal authority to put people to death for jaywalking, however such a change in the relationship between the government and the people is a massive change in power.

Where are you hearing 40-60%? The campaign site specifies 20%, which is quite absurd enough as is, and I don’t recall hearing any other number.

Wouldn’t one possible factor in per capita GDP rates be just, ya know, capita? Looking at India’s fertility rates, they were just under 6 kids per family until late 60s and then started steadily dropping. Maybe this shows in the GDP with a bit of a delay – more parents available for work, more possibilities for families to move from substance agriculture and take chances, the effects of poverty are less dire with less mouths to feed etc. https://assets.lifesitenews.com/images/made/images/remote/https_www.lifesitenews.com/images/local/popgraph1_604_468_75.jpg

It seems kind of short sighted to try and pin all of India’s success on internal policy. By the 1980s globalization in the developed world is in full swing, so almost any developing country with a large population and cheap labor is bound to do better. I don’t know that much more explanation is required

This has to be the most disappointing post I’ve read on SSC. 1. Bernie Sanders isn’t likely to kill millions with his ‘radical socialism’ as many have pointed out – he just wants the USA to be a bit more like Sweden. I don’t personally believe there is a viable path from here to Sweden, but nevertheless, Pol Pot he is not. 2. India is a high entropy mess with a strong and persistent caste system ,a patrimonial political economy and no history as nation state. If Nehru had been Ayn Rand’s lover, I doubt India would be richer today than it is. If he’d been an Ordo-Liberal circa Germany in 1952 I doubt India would be richer than it is. If he’d been General Park of Korea …… etc , etc.

The kind of policies that would have given India, China like growth were just not going to happen in India (the excellent Joe Studwell book on East Asia doesn’t talk about India but it’s clear the social and political conditions that gave East Asia its growth, such as land reform and a strong penetrating state bureacracy capable of designing things well did not obtain in India and that India would rank much lower than his worst cases – the Philippines and Indonesia). Since the 1980’s what’s happened is that India has converged on a quasi liberal, service oriented economy that sort of works for the mess that is India. A lot of it is also demographics. When India starts aging it will be bleak, because India has skipped the industrialization phase that creates a modern economy and modern polity.

India was a British colony into the 1940s. Profits were exported to England, not necessarily spent or reinvested in India. (This is a big development problem. In colonies and many non-colonies, profits are often exported and turned into villas in the Riviera and the like.) Whichever metric one uses, it looks like growth and poverty reduction started in earnest about 20 to 40 years after the end of the colonial era. Unlike the US, which developed its own government and institutions as a colony, the government of India was firmly subordinate to its colonial masters, so it’s not surprising it took a while to get things sorted out and develop institutional expertise.

As for socialism, Bernie Sanders is as socialist as Dwight David Eisenhower. If anything, Sanders wants lower peak marginal tax rates than Eisenhower had. Socialism isn’t all or nothing. In every developed nation, the government has to drive technological advances and create comparative advantages for trade. That means industrial policy, resource policy, agricultural policy, educational policy, health and public safety policy, transportation policy and so on. At some point or another, the government has to pass the torch to the private sector, whether it is at the financial, corporate or individual level. Most arguments about socialism are about where to replace that dividing line, but the important arguments are about the driving direction.

India has a lot more problems than socialism. If nothing else, there is the caste system which encourages social and economic stagnation. Even now, a dalit who wants to get ahead has to tread carefully and encounters all sorts of biases and disadvantages. Contrast this with China where the Han are one people, and there is a long tradition of economic competition. I’m always amazed India does as well as it does.

@kaleberg says:

the profits from FDI are also exported. that doesn’t matter.

Taxes under Eisenhower were 17% of GDP, exactly the same place they’ve been ever since. Bernie wants to raise them considerably from that level. And the high rates under Eisenhower are misleading, because the tax code at the time had many more deductions and exemptions than the modern code.

No it doesn’t. Private capital can do that.

gee, if only there was some sort of social system that allocated capital on the basis of return on investment instead of caste. maybe we could call it capitalism? Is that taken yet?

The fact that the comments of this blog are dominated by reactionary Republicans such as yourself is one of the internet’s biggest mysteries.

Maybe things would be less mysterious if you took more account of the facts we’ve so graciously provided you and less account of the incorrect assertions you’ve made.

India is somewhat decentralized, so states can be quite different. Kerala in the southwest is usually run by the far left. They are said to do a good job with education and services, but are bad for business. So lots of people from Kerala go to work in the Persian Gulf and send money home. The state next door where Bangalore is is said to be more pro-business.

So this could complicate your search for a trend line.

Yeah, seems probable that it would.

Decentralization is key to how India had flourishing parliamentary democracy at the same time as one-Party hereditary rule by the Nehru family, IM(Outsider)O.

Question for Scott unrelated to this post:

Would you be ok with me creating a podcast feed of the entire archive of SSC put through a text-to-speech? Here‘s an example of what it would look like.

looks like poverty rates start their dramatic decline in 1969-1970, a date no one is citing as ‘something having changed’.

The prior years were very bad, if you look at the trends from 1950-70 it looks just like a return to prior trends. It isn’t really until after that point that the trends reverse.

Of course it is possible that it was something that happened in the late 60s – trends that are extremely sensitive to arbitrary starting points can be used to explain about anything if you aren’t careful.

You need to read Ha-Joon Chang

I read some of his books. If I remember correctly he says he is in favor of “capitalism, just not free market capitalism”. Protection of important industries, active government role in fostering other industries, welfare, regulation – that kind of stuff. This is somewhat left of economics mainstream but it’s hardly socialism.

Is that what you’re advocating or do you think this doesn’t go far enough?

Emigration might be an interesting factor to look at. At a cursory glance, migrationpolicy.com tells me that

Remittances could help explain some of the pre-1987 growth. This also helps explain the pro-market and pro-trade reforms as more and more connections between India and the United States are formed and capitalist ideas start to flow back to India.

This is a thing, I wanted to ask aas well. Indian and Pakistani first generation immigrants, are a staple trope from american media from the last 30 years. Expats often send big amounts of money, to the families they left home.

Could this inserted enough capital into India to alow them to finance economic growth?

This article seems to contradict the notion that there weren’t any pro-business policies until the late 80s.

Possibly rude, true, necessary: Basically the entire problem with arguing with capitalist apologia is that those kinds of takes are considered “historically-informed”. This somehow always ignores actual (extra-economic) historical context (like Stalin’s overall disregard for human life, Pol Pot being a genocidal nationalist, or Mao being…uh, Mao.) Meanwhile, even bigger numbers of people who starved to death under capitalist rule are always easily handwaved away. This, of course, is particularly grating while discussing India, which went from millions of people dying every few years to essentially nobody dying in a systemic manner with the simple trick of regaining independence from ur-capitalist British empire.

Bernie Sanders needs not concern himself with India, because he has a perfectly fine positive model for his plans, mainly the entire western world several decades ago. Studying India to counter this will yield an argument even less persuasive than studying Cambodia.

That was an aside, though. My real point here is – there’s essentially no evidence that a degree of economic “liberties” has a meaningful impact on economic well-being of countries in the first place. There is an argument to be made that private property and markets facilitate growth under specific conditions (just as they stifle it in others), but there’s no argument, and indeed no indication, that it in any way generalizes enough to be applicable to 1990’s India, 2020’s America or anywhere else. Concerning oneselves with them is ideologically motivated, and likely to prove merely a huge distraction away from actually meaningful factors.

My personal hunch, superficially consistent with broad-stroke patterns of history, is that economy of a country depends mainly on its bargaining power, which is in most cases a product of military power. The entire history of Asia’s economic down- and up-turns can be directly traced to liberation from western imperialism. First, of course, there’s a post-WW2 decolonization. Then, Japan, then Korea and Taiwan receiving US protection and market access lets them overcome their periphery status. Then, US gets a huge hit in Vietnam, and in Iran, with an oil crisis in the meantime. This shakes up the west’s economic foundations, enough to lead to liberalization of finances and trade, which kickstarts the transition of the world hegemony from North America to East Asia, of which India is one of beneficiaries. Whatever India’s government did during that time is largely insignificant in comparison. They merely had to avoid fucking up as badly as, say, Mao, but seeing that even Mao’s wacky hijinks didn’t stop China for long…

Ah, yes, the claim that socialism isn’t the problem, just socialist leaders. Frankly, even if I grant you the case, you aren’t any better off. Either socialism doesn’t work, or it does work, but the people who become socialists always seem to pick leaders like Mao. either way, the idea should be considered harmful.

You can’t handwave things that don’t exist. capitalist famines are vanishingly rare, even by the most generous definitions of the term, and don’t come anywhere close to the socialist deathtolls.

That’s a funny way of describing a global agricultural revolution that took place in almost all countries regardless of whether or not they remained under british rule. Deaths from small pox also fell dramatically in the same period, are you going to ascribe that to the end of british rule as well?

That’s not a model. those countries did massively different things with massively different results.

This is simply ignorant. The correlation is strong, and the causal link easily demonstrated by countries like Chile, China, and Ireland.

the richest countries europe of any considerable size are switzerland, ireland, norway, iceland, and denmark, none of which has any meaningful military power. Your hunch is nonsense.

Funny how that didn’t work in the Philippines or Thailand, both of which also got US protection and market access.

Yes they did. China was poorer than sub-saharan africa when Mao died. Things didn’t start to change until they liberalized, an idea you earlier said was beyond ridiculous.

Donald Trump hates the Washington Post and New York Times. And the worst thing he can do to them is . . . cancel the White House’s subscriptions.

The United States government began a giant program of surveillance that was illegal on its face, the New York Times knew about it, and the government threatened them, and they didn’t publish.

Caveat 1: In the main, I think “socialism” (if we call the Soviets and Mao that) did kill more.

Caveat 2: This game of piling up all the skulls can get a little gross.

Still…something like 20 million starved to death in the British controlled India 1860-1945. Thats like 2 million every decade. Just in India.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Timeline_of_major_famines_in_India_during_British_rule

Lots of caveats often get added-Don’t the Imperial Japanese deserve the lions share of the blame for the starvation in Bengal in 1943? Once the British imposed the famine codes in the late 19th century the number of famines subside and the British were largely successful in stopping a famine in Bihar in the 1873-don’t they get credit for that?

So yes, for example, 4 million die in the famine in Bengal in the 1940s and 7 million die in the holdomor in the 1930s. We could grant that 35 million die in the Great Leap Forward and 8 million die in the holdomor vs 21 million who die in the Indian/Irish famines from 1840-1950. Stalin is worse than Churchill and the Soviet Union is worse that the British Empire. Capitalist/Imperialism’s pile of skulls is smaller!

But isn’t it at least a little close? An average 1-2 million starving every decade from 1840-1950 isn’t “vanishingly rare.”

India had some bad near-droughts in the 1960s and 1970s. Was that really stopped by the green revolution? It is unclear to me that the famines in the 19th and first half of the 20th century were impossible to prevent and needed 20th century technology. The British did avoid famine in Bihar in the 1873 (wiki implies they overreacted and the government then got criticized for spending too much so they then underreacted to the Great famine of 76) and the famine codes of 1880 did help. Was the Irish or Indian famines really impossible to prevent? Obviously history isn’t a science experience where we can rerun to see how a democratic independent India or Ireland handles those challenges but I am unaware of few famines that ravage independent democratic states-there are a lot of votes to be gotten in making sure people get fed. On the other hand in an imperialist capitalist system where the Indians don’t really vote (and Ireland, despite having half the population of England in 1848, had way less than half the MPs) you can see how the system would be less responsive to the needs of the imperial possessions vs. the metropole.

mrdomino says:

Let’s not play that game. there is no honest sense of the word socialist that does not apply to mao and the USSR

Not nearly as gross as the game of sweeping them under the rug.

That number is absurdly high, but for most of that period India (A) wasn’t really governed by the British. It was bunch of princes that pledged fealty to whoever the current monarch was and then were left to run their own affairs. And (B) isn’t anything remotely capitalist. If capitalism means anything, it’s a society where most people make their living by buying and selling goods on a market. Colonial India was a peasant society where most people grew their own food, not a capitalist one, and peasant societies, by definition, have a lot of people living on the margins of sustainability.

Note the shift in goalposts. Socialist governments run around actively causing famines, and they are being compared to capitalist governments who failed to prevent them. If we’re looking at excess deaths, then capitalism looks even better, because, especially in the time period we’re talking about, LE and GDP per capita are very highly correlated, so an economy that grows faster saves an enormous number of lives. Socialists, always and everywhere, failed to deliver on their economic promises and lagged behind capitalist growth.

“Every bad example of your system is germane and dispositive, every bad example of my system isn’t really my system because reasons.”

Surely you can step outside of yourself to see that when you dismiss the Indian example as not capitalist you are doing EXACTLY what you accuse him of doing with socialism.

@Freddie deBoer says:

Less of this, please.

I gave reasons, very specific ones. If you don’t like them, try arguing against them instead of dismissing them. I rejected one example, not every example. If you want to talk about, say, Ireland, you have a much better claim to calling it capitalist. But India in 1780? no. And in 1943, there was no rice because the Japanese had stolen it all. SO also not capitalist. Stalin, on the other hand, he swore up and down what he was doing was socialist, was celebrated as a great socialist by socialists all around the world, and he refused food aid rather than admit that socialism wasn’t working.

Today, in capitalist India, children literally live surrounded by excrement. But that’s not an indictment of capitalism; that’s not relevant. In Russia, the death of communism and implementation of capitalism saw an immediate and massive decline in life expectancy. If this situation was reversed and Russians suddenly saw a big jump in life expectancy, you would never stop hearing about it from capitalism’s cheerleaders. Instead it declined to a degree that’s truly rare. Yet you certainly don’t hear about it from Scott, and you won’t hear about it from you. But let me guess: that doesn’t count. Because reasons.

@Freddie deBoer

Who said anything about India today? We were talking of india in the mid 20th century. But fine, if you want to talk about india today, is the amount of excrement on children increasing in capitalist india or decreasing? is it higher or lower than in socialist india? because by my measure, it’s going down, something socialist india failed to achieve.

No, the decline of LE started under communism, as the wheels finally started coming off. Under capitalism, even Russia’s very weak capitalism, it’s reached all time highs. Any more myths you’d like dispelled?

I suggest we go further, and include all kinds of death. Yes, even dying of old age. By that metric, both capitalism and socialism have death rates 100%. Therefore, no one should be pointing fingers.

From a sufficiently generous perspective, there is nothing wrong about sending millions of people to death camps. In other regimes, people ultimately die, too!

@Freddie deBoer, @cassander,

The decline trend of Russia’s life expectancy did start in the 1960s, but it’s also about alcohol use/abuse. The uptick in the late 80s before returning to the previous decline trend matches the implementation and then removal of Gorbachev’s strict anti-alcohol policies.

@sharper13

that is a very good point, although that article is about 20 years old and the LE has since surpassed the 60s high. I have no idea how much alcoholism levels have changed since 2000, a followup would be interesting.

The rate of famines increased significantly under British rule, which suggests that colonialism was indeed causing them, just in a less direct way where you can’t blame it on some specific central planning guy who gave a specific order.

(Also, this whole thing smells of Copenhagen ethics – so long as you do nothing, the crisis can’t be your fault, because neglect isn’t a thing. The crowd around here has no issue saying things like “Failing to do public health intervention X killed Y million people and cost Z million QALYs,” why don’t we ever say anything similar when it’s economics and not medicine?)

@beleester says:

Did it? Or did just the documentation of famines increase?

Well, (A) I think there is a huge moral difference between not fixing something bad and causing something bad, but even if you don’t, you need to compare apples to apples. If you want to count the deaths that capitalists allowed to die due to laissez faire policies, then you also need to count the people the socialists allowed to die because lower economic growth resulted in lower LE.

and (B) I don’t say that failing to do X killed Y people, at least not the way you describe. But if I did, you’d have a fair point.

Yeah, I don’t think that’s actually a thing we do here very much. Also, there is very much a difference between neglect and deliberate harm, and for that matter not all inaction is neglect.

There is a brand of consequentialism that suggests that everyone is always obligated to act so as to minimize global harm. But that’s a minority opinion even here, even more so among the vocal proponents of capitalism here. Those who hold that opinion, generally do not accuse those who fall short of their standards through inaction of being murderers – even as they do accuse those who actively kill people of murder.

Alice walks past a hungry person and does nothing. Bob walks past a successful farmer and takes all his crops, leaving him hungry while Bob pursues some noble cause with his wagon of grain. The attempt to cast them as morally equivalent is noted, ridiculed, and dismissed except as a black mark against whoever said such a damn fool thing.

THERE were two “Reigns of Terror,” if we would but remember it and consider it; the one wrought murder in hot passion, the other in heartless cold blood; the one lasted mere months, the other had lasted a thousand years; the one inflicted death upon ten thousand persons, the other upon a hundred millions; but our shudders are all for the “horrors” of the minor Terror, the momentary Terror, so to speak; whereas, what is the horror of swift death by the axe, compared with lifelong death from hunger, cold, insult, cruelty, and heart-break? What is swift death by lightning compared with death by slow fire at the stake? A city cemetery could contain the coffins filled by that brief Terror which we have all been so diligently taught to shiver at and mourn over; but all France could hardly contain the coffins filled by that older and real Terror—that unspeakably bitter and awful Terror which none of us has been taught to see in its vastness or pity as it deserves – Mark Twain

Like most capitalists, Scott never even tries to address the greater Terror. Like you say, it gets handwaved away.

Analysis of the trope: Compare yourself with the rest of the universe, and argue that the rest of the universe is responsible for more evil (in absolute numbers) than you.

Example:

“How can you praise Hitler? Millions of people died in his concentration camps!”

“Oh, maybe they did. Maybe. But isn’t hypocritical how the opponents of national socialism always fail to mention the billions of people who died outside of our concentration camps since the dawn of history? Now who is the actual bad guy here: the Nazis, or the non-Nazis?”

Does Twain talk about Capitalism or Monarchy?

Do current self-descriped socialist states look more like the Ancien Régime, or do states that do not describe that label to themself?

Le Grand Terreur isn’t staple example against revolutions because the Directorate was so different from what came before. It is an example how it was not different.

Well, according to Marx, French Revolution overthrew feudalism and installed capitalism.

@AlesZiegler,

Well, according to the French National assembly, where the terms were originally defined, the participants in the French Revolution were all literally left-wing. 🙂

@AlesZiegler

All the more reason to ask, why the …. this quote should be a defence for self described socialists states?

Or to be more clear: Is there any proof that socialism is a way out of this first Greate Terror? And I don’t mean the weak sauce “Soziale Marktwirtschafft”, we practise in in Scandinavia and Germany.

That’s a phenomenal quote.

It’s relatively well styled, but in terms of ideas it is muddled.

A Connecticut Tankie in King Arthur’s Court.

– Robert A Heinlein

Leftists who took power by revolution have been terrible. Mao, Stalin, you know the list. Don’t get one of those.

Leftists who took power by election have been… sometimes quite good.

In India, Kerala has been a standout state, with the highest Human Development Index in India, beating out all the others on metrics like infant mortality, education, life expectancy. Why? Because they’ve been ruled by Communist Party governments for much of the decades since independence. And it turns out that the Communist Party took the welfare of ordinary poor Indians a lot more seriously, and with a lot fewer excuses about caste or tradition, than other parties. And because they were in power by votes, not guns, they had to stick to policies that showed benefit in real time to real voters.

Likewise leftist parties in Sweden and Denmark have presided over vast expansions of the welfare state that… haven’t damaged economic growth at all, and seem to have given people a better, more secure life.

On the other hand, leftist policies in Britain after WW2 seem to have been worse than useless, extending the suffering of wartime rationing for decades even as the Continent was enjoying a huge recovery. And while you can have a true-Scotsman argument about leftism in France, whatever it is it doesn’t seem to have aged as well as the Nordic model.

So clearly there exist both “helpful elected leftists” and “harmful elected leftists”.

But leftist revolutions have been a disaster. Don’t have one.

What about right wing revolutions? Have these also been unmitigated disasters? If so, maybe the main problem lies with people trying to take power outside the democratic system.

Are we talking about death toll, or economic growth?

Death toll: right-wing takeover usually looks more like “coup d’etat” than “revolution”, and perhaps because of that usually kills far fewer people from the majority ethnicity. Since they reuse the existing military and police, a coup government needs to kill less to make itself confident in its authority. So right-wing coups are mostly slaughterhouses only for ethnic minorities (Armenians, Jews, Maya, etc., depending on country).

If you’re in a country that doesn’t have a suspect ethnic minority, you probably get a 10x-100x reduction in slaughter for having a right-wing coup instead of a left-wing revolution. (Congratulations?)

The trouble is, saying that sounds like saying these governments are nice, and that’s false. Coup governments are infamous for death squads, “disappearances,” torture, etc. It’s just we may get to measure these tolls in “thousands dead” instead of “millions dead”.

Economically… it’s kind of a mixed bag. When a democratic country has a coup takeover, on average economic growth declines; when an already-autocratic country has a coup takeover, the average economic effect is positive but small. Basically individual cases vary widely.

So if you already have a democracy, don’t have a right-wing coup. If you don’t have a democracy, you might gain from a coup… but be careful what you wish for.

Woah woah. In the early 1970s Swedes had equal GDP/Capita to the US, and then steadily fell behind the US till their market reforms in the 90s. And still haven’t caught up. The Finns have a similar trajectory, but started slightly poorer.

All while the US was taking in a large % of immigrants that mostly came from below the media of their GDP/Capita, making that statistic even more damning.

Sweden’s relative GDP per capita to the USA has been remarkably stable over the long term. Sweden GDP/capita today is 6% above USA; in 1960 it was 3% above USA – basically no difference.

Randomizing across starting years 1960-1969, the curve is even flatter (about 6% over USA income at the start of the sample, and about 6% over now).

You can check out the statistics yourself with the lovely FRED database.

Denmark does a bit worse than the USA, dropping by 8% per capita over 55 years, which is again a pretty small effect relative to noise – especially as most of that decline can be accounted for by the worse EU response to the Great Recession (Denmark’s krone is pegged to the euro, so it was forced to austerity, unlike Sweden).

In fact, if you choose a 2008 end date to avoid “EU handles the Great Recession worse” effects, even France-to-USA doesn’t look that bad, although then we get into arguments about WW2-recovery effects.

I suppose you could argue that European leftism led to being cavalier about central banking, and that in turn led to the mistake of the euro and the uber-mistake of Great Recession EU austerity. If that was true, it would be a nice argument against leftism. But I’m not sure the left is more naive about banking than the right – just differently naive. Comparatively right-wing America has lots of Stupid Banking Mistakes in its history.

That graph is like Viagra for the free marketers (although Sweden is higher at all times than other graphs I’ve seen such as in this

). The welfare state expansion was in the late 60s/early 70s and the market reforms were in the early 90s.

Now, I don’t think these graphs are the be all-end-all. Because I don’t think policies always have effects, and things like GDP/Capita in an interconnected world are more likely to be driven by things like intelligence, education, etc so long as the regime in place is not really bad.

The one thing I remember growing up in the 80’s in India was the change in my family’s life after Rajiv Gandhi came to power in 1984. That should be considered as a starting point. he brought in his friends from Doon School to begin the reform, especially Arun Nehru.

The first thing I remember was the pay Commission of 1985 or 86. Before that, India being a quasi-Socialist country; public servants were paid really badly. Public Service was considered to be doing public good without expecting remuneration, because … I don’t know why. My dad’s pay went up by a considerable amount and 1986 was when I remember having a life without having to worry about the next payday of my Father. So that was where it began. The after the fall of the Soviet Union when India was no longer getting oil on the cheap; IMF forced India to liberalize the economy. The reforms that were judged too ‘controversial’ by previous administrations were finally allowed to be put in. The credit for that should go to the PM PV Narasimha Rao along with Manmohan Singh and Chidambaram. But since PVN was already a part of the Congress leadership in the 80’s, he was privy to the reforms that were proposed in the mid 80’s, but could not be implemented for political reasons. The fall of the Soviet Union and the loss of cheap oil was the triggering point for full scale liberalization. But the seeds were already sown by the Rajiv Gandhi 1984 government.

+1 for the inside look, thanks.

“But nobody thinks that Bernie Sanders plans to kill a six to seven digit number of people.”

First, 35 million people died in a famine because Mao’s economic ideas were terrible, not because he felt they were inferior and had to die. I mean, the CCP did and does commit plenty of murder, but that wasn’t the only problem. No amount of good intentions will cause farmers to learn how to make steel, or change the fact that birds eat pests. Planned economies will always suffer information and incentive problems.

Second, even if the true believers are honestly well-intentioned, their systems open the door for abuse by the sociopaths, the amoral but self-interested, the corrupt, etc. A system that turns to genocide if it puts one evil leader in power is not a robust system. Maybe Dictator-for-life Bernie wouldn’t order me executed, but it doesn’t take long on social media or certain subreddits to find people salivating over the idea of throwing conservatives into re-education camps.

So we’re in a much better position economically, and mistakes don’t cost us as much even when they’re the same kind of mistakes. I can get behind that. This reflects one of my deepest fears – there is an “acceptable level of progress”, and there are a number of wealth sinks that take everything extra. Richer countries have more social policies and more regulation. And regulation behaves like entropy – you mostly get rid of it when you (re)create a country, otherwise it just accumulates.

This isn’t all bad – it’s perfectly normal to take care of your population when you’re a richer country. But this doesn’t really feel like what’s going on. Poor people are still… poor somehow, even if the dollar value of welfare spent on them _should_ make them rich by 1950 standards. Because rents, NIMBY, minimum wages and so on.

It’s something I’m so afraid of because it’s invisible. We don’t see how we could have flying cars, cities on the moon and live to 120. We just see the present and imagine it’s pretty good.

The interesting thing to me is that the big actually existing socialist states existed in economies where there was a large class divide between rural farmers and urban proletariat, as well between both and the bourgeoisie, so there was a three way class thing going on that Marxism doesn’t neatly describe, other than by recourse to terms like petite bourgeois.

Enormous famines were generally created because of A: taking grain from peasants to make things better for proles and to sell abroad for industrial equipment (Stalin), and B: pure incompetence driven by insane looney tunes style ideas about freeing the peasants (Mao).

Now that almost no one is a subsistence peasant and farmers represent an extremely small percentage of the populace, it’s easier to take to take surplus without eating into the amount farmers need to live, so A would be less harmful, and B probably wouldn’t take place in the first place because agriculture doesn’t involve a peasantry to begin with today. Possibly, modern command economy technicians would come up with new ways to fuck things up, but I imagine it would be more similar to the slow grinding misery of the late era Eastern Bloc, then the famines of the early period.

Of course, in some ways a soviet socialism that couldn’t fuck things up much economically would be worse, because a lot of people find the revolution and re-education parts good, and those are harder to argue against from an empirical basis. It ends up as zero sum moral preference stuff. As greater levels of automation become possible and innovation slows down due to the laws of physics limits, state socialism will have fewer economic inputs to fuck with and less innovation to strangle, so it correspondingly becomes more viable and appealing.

There are plenty of countries that currently have to import calories. You can look at figure 3 here to see which countries are particularly teetering on famine if someone threw a wrench in the works.

No, there are plenty of countries *that import* calories. The article lists Italy and Spain as “food insufficient” countries, but all that shows is that it’s not currently economically competitive to farm there, not that those countries would starve if their food imports were restricted.

It looks like the USA has both high food self-sufficiency, and high net exports in food trade, at least.

A lot of beneficial changes in economic policy can happen without any explicit, written policy shift. A lot of government rules, restrictions, etc. are more or less discretionary, especially in countries like India. Individual regulatory actors can pretty much destroy companies if they decide to, or cause them large expenses. India has a lot of those people. Ghandi could have told them to stop, or at least tone it down. Strong signals from leadership that you should stop impeding business formation and development can have a pretty large effect under regimes like this. Ghandi could also make it clear that your advancement will be halted if companies complain about you causing problems for them. Doesn’t take telepathy so much as a strong signal from the leaders of a large bureaucracy that officials will not benefit from causing problems for business. The actual policy in this case might well have been a lagging signal of something that was mostly already done (formal recognition that the bureaucracy stopped interfering quite so much).

The problem with a lot of socialist policies in practice is as much arbitrary enforcement as anything else. The policies are often bad, but the fact that officials have a ton of discretionary power over economic activity is far worse. This is why it’s so hard to detect the impact of regulatory changes on economic activity. The rules matter, but the enforcement of the rules matters a lot more and this is very difficult to measure. From various things I’ve read / heard in talking to Indians, India has a huge number of officials with some power over economic activity. Too many individual pockets of officials that all have to be satisfied in order for a national enterprise to be consistently successful. Weakening as many of those pockets as possible helps a lot for economic growth.

Yeah I suspect this is the main thing. Pure guesswork though. Even if some Indian policy makers from the ’80’s confirmed that this happened then, it would be impossible to prove.

Hi Scott, over the last few weeks/months I’ve noticed the quality of your posts have gone down. This is apparent in this post as well. I’ve nothing against the thesis of this post, I’m broadly in agreement with it. But your previous “much more than you wanted to knows” were much longer, much more well-researched, and had more references. I’m sure you could have written something much more comprehensive about Indian economic reforms if you wanted.

Previously I couldn’t wait to read your posts; in fact after I discovered your blog I read ~150 past posts in a short interval. But now I see ~15 posts in the last month or so that I haven’t bothered to read.

I understand that you have a busy schedule as a doctor. And we can’t demand anything from you, it’s a labor of love. But I just feel sad that something I used to love is going downhill.

That quote from the Charter Cities report seems pretty shoddy. Almost all of the claims about how much things have improved you data points from decades before the 1991 reforms, which clearly is an issue if (as seems to be the case from the poverty graph) improvements were made pre-1990.

What sectors grew during the 1980s and what sectors didn’t?

This is where my thinking was leaning – perhaps, sectors that were less regulated started growing and hit a wall in the late 80s corresponding to the crash and asking ‘why did they stop’ led to further reform?

This seems like it’d have lots of overlap in the research in How Asia Works. That book tends to be pretty pro-socialism, but in a limited fashion, and in the context of a slow transition into capitalism as the end goal.

The Green Revolution comments are good ones. Aside from those, keep other factors in mind: India is, indeed, a state that moved away from its own branch of socialism a bunch. India is also a state that warred with its neighbors, tried to genocide some of its own people, and had millions of its brightest move the hell away. The possible confounders are very much there and should be considered before deciding that the label socialism is to blame for all.

???

That would be the literal millions of sterilisations issued and the pogroms against Sikhs after Indira Gandhi’s bodyguards got fed up and killed her, yes.

Those are only cofounders if you don’t consider them the likely outcome of socialist economic policies. And except for warring with your neighbors, they definitely are.

Non-socialist former colonies have had these things happen, too. It happened in European countries as well, but we’d mostly gotten past that by the point the rest of the world caught up.

India is tough to crack for big sociopolitical questions like this, because what it did after Independence is weird. They had a flourishing parliamentary democracy for decades… that didn’t crack one-Party rule by Congress until 1977. And that breakthrough only happened because, well…

Desai became the first non-Congress Prime Minister with the failure of Indira Gandhi’s attempt to become a dictator, but didn’t pass economic reforms and Indira returned to power in January 1980, the family business of ruling India passing to her son Rajiv upon her assassination. Rajiv was also assassinated, during the second Opposition coalition interregnum in Congress rule, at which point it ceased being the Nehru family business, allowing P.V. Narasimha Rao to come in and dismantle the Licence Raj.

This was basically a reductio of what pro-business Americans complain about as “socialism” or left-of-center hegemony. In the US, they don’t literally need permits from up to 80 government agencies to have a private business and the license laws in place aren’t explicitly linking to desiring a planned economy, but in India…

The timeline on your graph isn’t incompatible with the corrupt bureaucracy enforcing the Raj reforming in the 1980s under Indira and/or Rajiv, but I’m disinclined to give them credit for anything. All credit should go to the Opposition (more the Hindu nationalists than the old coalitions, which as we can see did nothing for the economy in the late ’70s and are hard to disentangle from the 1991 reforms or “invisible” reform by Rajiv their second time in power) and the more democratic Congress of Rao, not the non-Communist leftist hereditary rulers slapping their foreheads and being like “Oops!”

Logged in to say something similar. Something pretty obvious happened to India in 1975. It was called the Emergency. Socialist opposition of central government policies led to things like the suppression of strikes and arrest of opposition. And when Janata came to power, it had a much bigger voice for business (being formed by opposition parties, many of whom cut their teeth against socialists). One that elected a business sympathetic former finance minister in 1977. Meanwhile, the Fabian-influenced socialist party had blown its socialist credentials by doing things like arresting strike workers and also moved in a more pro-business direction. And this led to a notable pro-business shift leading into the liberalizations that have followed…

I can discuss this more but it’s not really that confusing a narrative. It would be confusing if the break was in 1970 but not in 1975, when there was a clear shift in economic policy and politics following a dramatic and wide reaching political event.

https://slatestarcodex.com/2019/10/23/indian-economic-reform-much-more-than-you-wanted-to-know/#comment-812933

Wait, what? Became? They already were! Capitalist Britain turned those places into dumps via capitalist exploitation. Any former colony of the Britain did far better without the yoke of Capitalist British oppression.

You are whitewashing colonialism to put it lightly.

If we’re going to obfuscate and play the death toll game then the argument defeats itself. If we accept the prostituted definition of “Socialism” and “killing” that this argument uses then the death toll of say African Capitalism is far greater then Eurasian socialism/communism.

Also the population of the USSR was increased dramatically by Stalin despite the millions dead.. Perhaps the simplistic narrative you are pushing is more nuanced then you’re suggesting?

Bernie Sanders platform is a mere cookie-cutter Nordic style economy, nothing more, nothing less.

Okay, but did some ex-colonies do better than others?

Isn’t Africa heavily socialist/communist with a heavy dose of authoritarianism? By the way what is that number? If they have over 100m killed as a direct result of capitalist policies that would be very surprising.

Nordic style economies are free market capitalist economies- significantly more free market than the U.S. That is not what Bernie wants. Bernie wants far more regulation than Nordic states have.

> did some ex-colonies do better than others?

Between 1945 and 1960 the following countries got independence from the British empire:

Jordan, India, Pakistan, Israel, Burma, Sri Lanka, Libya, Sudan, Ghana, Malaysia, Cyprus, Nigeria, Somalia

I think Israel, and perhaps Jordan and Cyprus, are the only countries that have clearly done economically better than India during that time, and some have clearly done worse.

> Nordic style economies are free market capitalist economies- significantly more free market than the U.S. That is not what Bernie wants. Bernie wants far more regulation than Nordic states have.

This seems right. I think Warren is much clearer in wanting this sort of social democratic/neoliberal state that Scandinavia has.

Bernie Sanders is definitely unclear about what he wants.

You say you want a revolution… a socialist revolution… that consists of just winning an election rather than violence… and your government won’t institute a command economy…

That’s a bad case of undefined terms.

Libya and Israel were not really colonies of the UK, just administered by them for a relatively short period. Cyprus and Malaysia are well developed countries much richer than India. Interestingly the richest African country is Mauritius a former UK colony, which is described as highly developed, and supposedly is the third freest economy in the world according to the Heritage foundation.

Would you be able to provide any details on that? I’d like to know more!

Population of pretty much any large area of land has grown over that period. Giving Stalin (or socialism) credit for that happening in the USSR is about as justified as thanking him for the fact that the Sun was raising over each of the Soviet Republics, every single day of his reign without ever slacking.

Every good communist knows to thank Uncle Stalin for the sun rising each day over the Soviet Republics. Surely you’re not implying that we shouldn’t thank him? Seems like an… unfortunate misunderstanding on your part. Better apologize before somebody notices.

Nice to meet

a man of culturean ideologically savvy comrade here! Sure Stalin’s played invaluable role in providing sunshine to every Soviet worker and peasant. Moreover, it’s only through his infinite wisdom and thoughtful oversight did the crops know to ripen in the fall to keep people fed trough winter.Stalin’s policies directly led to a decrease in the death rate by giving free healthcare to all among other things. Its all doom and gloom when capitalists talk about Stalin but the man saved millions of lives.

It’s all really doom and gloom when you read memoires of those who lived during that time. Or look at the long long lists of innocent people shot down or send to death in gulags. Capitalists would mostly talk about statistics, which, whether correct or not, is not nearly as graphic.

Whatever healthcare was actually provided – as opposed to just declared – was nowhere nearly enough to offset deaths from repressions, massive forced relocations of entire ethnicities, and hunger caused by completely incompetent management. Nevermind completely incompetent command during first months of USSR participation in the WWII and foreign politics prior to it, which lead to much higher casualties than could’ve been.

Stalin was vastly popular in the USSR even after destalinisation. In Russia today Stalin is held in high regard by about 50% of the people there.

Many were not innocent and were legitimate coup plotters or just your average criminal scum. A user above me provided a very pertinent Mark Twain quote which I will reproduce here –

“THERE were two “Reigns of Terror,” if we would but remember it and consider it; the one wrought murder in hot passion, the other in heartless cold blood; the one lasted mere months, the other had lasted a thousand years; the one inflicted death upon ten thousand persons, the other upon a hundred millions; but our shudders are all for the “horrors” of the minor Terror, the momentary Terror, so to speak; whereas, what is the horror of swift death by the axe, compared with lifelong death from hunger, cold, insult, cruelty, and heart-break? What is swift death by lightning compared with death by slow fire at the stake? A city cemetery could contain the coffins filled by that brief Terror which we have all been so diligently taught to shiver at and mourn over; but all France could hardly contain the coffins filled by that older and real Terror—that unspeakably bitter and awful Terror which none of us has been taught to see in its vastness or pity as it deserves”

Why was this a bad thing? As Molotov put it “The fact is that during the war we received reports about mass treason. Battalions of Caucasians opposed us at the fronts and attacked us from the rear. It was a matter of life and death; there was no time to investigate the details. Of course innocents suffered. But I hold that given the circumstances, we acted correctly”

The Soviet Union was a beacon of workers rights, anti-imperialism and women’s rights, this is why we defend it. One of the reasons the USSR was viewed favourably by its citizen is that it was a huge improvement over Tsar rule.

Your first two answers don’t really address my arguments. In your third you seem to be implying that Caucasians (as well as Kurds, Koreans, Poles, Finns and others) were obliged to fight for Russians just because Russians conquered them. Which is an interesting thing to imply for someone who argued against colonialism few comments before.

That’s why leaving it was a crime punishable by death for the perpetrator and imprisonment for the family members, and people still did it, sometimes going through incredible hardships and danger.

They were poor when the brits got there, then poor when the brits left.

And you’re whitewashing socialist holocausts, to put it lightly.

No it isn’t. Not even close.

Bernie sanders wants reduced labor market regulation, charter schools, and local control of the welfare state now? Damn, who knew!

Yes but the problem was exasperated by capitalist Britain. Surely you aren’t denying that?

Is this really all you got?

No, it wasn’t. india wasn’t poorer when the UK left, it was considerably richer. But, then, you claim stalin as a great humanitarian, so clearly you’ve left all need for fact far behind.

It hindered its development and made its position in the world relative to the rest of the world far worse. Increasing GDP means nothing when that wealth goes to rich British aristocrats.

No amount of whitewashing can alter the fact that Indians had poverty forced upon them by capitalist Britain, their present road to damascus economy speaks for itself.

FDI where the profits go to western investors is precisely how india is getting rich today. The idea of colonial powers sucking money out of their colonies is simply ignorant, the flow was usually the opposite direction. Indians didn’t have poverty forced on them by the UK, they were found in poverty and, at the absolute worst, left in relative (but not objective) poverty.

@cassander

You accuse me of deny socialist holocausts but then deny the economic subjugation of India. Hilarious.

Because you do.

No, I point out that colonialism didn’t work the way you claim it does. What you describe is reasonably accurate for the Belgian Congo, but not India.

If Bernie Sanders style socialism is enacted in the US I predict the resulting death toll will easily be in the millions.

Could anyone send me the link to the large ethnically diverse country that has embraced socialism and thrived? because every single one I can think of has lead to the widespread slaughter along ethnic lines?

The State department and MSM told us South Africa was going to become a diverse paradise,

Hugo Chavez was a light of hope,

and that Iraq and Libya could finally be “free” without dictators.

but actually they were all Trillion dollar disasters. Now these same Phules are convinced that leftism will succeed, but every time I check who these people are they live in rich neighborhoods and send their children to schools that poor hispanics and ADOS can’t attend.

To quote a comment above that is needed here:

Obviously mass killings are, in a definitional sense, orthogonal

Are you arguing for apartheid? Because I can’t take any other interpretation from your South Africa point.

Also, “Phules”?

The first thing I would mention is that the trend in the graph on poverty (the second graph) is really reliant on one data point in what looks like 1985 plus the rise in poverty from 1960 to 1970.

My experience of socialism coloured the first half of my life. One rarely thinks of the UK as a radical socialist society, but the breadth and depth of Clement Attlee’s reforms starting in 1945 are quite staggering. A cradle to grave welfare state, including the NHS. Nationalisation of steel, mining, railways, all power utilities, water utilities, railways, road haulage. Long waits for everything became part of life, and were borne with a sense that such were necessary if we were to have access for all. Some aspects were a great benefit – for example university entrance was competitive and strictly based on ability, but once there tuition was paid and a means-tested grant would keep you fed and housed. No student debt, but only possible when a minority went on to higher education. But the sclerotic bureaucracy, and powerful union, in every state-run enterprise became an ever heavier burden to their function and dissatisfaction with this, along with the rapid inflation associated with the effort to maintain full employment meant it could not go on. Despite their imposition of such a workers’ paradise, the government was able to maintain a punitive attitude towards those who tried, with an 83% top tax rate, and a 98% rate for ‘unearned’ investment income. If there were anything left when you died, inheritance tax could be as high as 80% of an estate in 1969. Unsurprisingly, the economy ground to a halt.

I’m still not sure how to feel about Margaret Thatcher. We hated her at the time, and she was one of the reasons I left the UK and moved to Canada. But looking back I realise she was exactly what was needed at the time, and it seems certain she created the kind of economic change occurring at a slower rate in India as described above. With the advantage of age, hindsight and perspective, it seems rather clear we were whipped up into a fashionable, right-on, revulsion at everything about her: appearance, accent, twin-sets, pearls, handbags, policies, condescension and all. (There is a parallel to Trump today. I haven’t a good word to say about Trump, but I do see the media making a firestorm about every tiny little thing to keep up the hate – and goodness knows, there are enough whopping big faults with the man that they need not pretend to be fainting over the small infractions.)

I wouldn’t recommend anyone choose to live in the grim country of Attlee and Wilson, and equally I can’t see the relatively unregulated capitalism of extreme inequality being any use in the long term. The politicians of the ‘third way’ have been wolves in sheep’s clothing (Clinton and Obama being more conservative than advertised, and Blair far more radically left than supposed), and there is no reason to believe that a stable compromise or happy medium exists between the Attlees and the Thatchers. We must bounce back and forth between them, never letting either side make too many changes before swapping governments.

for personal reasons, I’d prefer the socialism side of things, but if I look at it with clear eyes and objectivity it’s really hard for me to deny that this sort of see-saw is what would really be best for the largest number of people

socialism to build people up, capitalism to let those people make the most of the skills socialism gave them. that capitalism builds up material wealth, then you turn back to socialism to channel that material wealth into more human development on a wide and equitable scale. rinse and repeat

Lancelot – my experience mirrors yours and I agree with most of your points. The only difference was that I was a supporter of Thatcher in the day. Thinking back on that time though I can’t help wondering if it could have been done in a better way, with less all round hatred and less of an economic cost.

Can you unpack the Blair comment? Found that interesting and wondering what you meant. For someone coming of age in new labour years it must be said that compared to both my impressions of what came before and what seem to be the options now,.it feels like something of a golden age…

Was there ever a golden age that didn’t turn out to be gilt? Beware nostalgia, which will eventually turn the worst experiences into happy memories!

Blair was sold as a third way politician in the serious media, but it was always noted that, learning from Clinton, he was willing to say whatever the focus groups indicated would be popular. Short on principle, perhaps, or maybe that responsiveness to popular sentiment is the true hallmark of the third way. Traditional lefties regard him as right wing, and conservatives have indicated they might have some grudging respect for him. Economically, the Thatcher boom was slowing, and the downsides of an economy linked to Europe were being felt, so he had little choice except to be fiscally responsible.

However, he had a very strong desire to permanently change some aspects of British society, and the changes he made to parliament are not to be underestimated. The Lords is now like the Canadian Senate – an appointed body with a few hereditaries in there to keep them quiet and maintain appearances. Instead of the Lords as the highest court of the land we have a Supreme Court which also permits appointments to colour its tone just as in the USA. The official immigration policy was to allow mass migration. The underlying thread behind this was all left wing populism, and we see one aspect remaining in the use of the term ‘The People’s [fill in blank]” today. Such a label still carries an automatic weight with the British public, the desirability of the blank notwithstanding. Simple, but clever, manipulation. It wasn’t just Thatcher that made me leave; the persistence of class mattering far more than it ought was also a factor, and perhaps I should approve of his wiles. But it turns out I dislike politicians who always tell me what I want to hear even more!

Blair explicitly marketed himself as a break with existing social democracy, calling his politics the Third Way.

It’s pretty interesting how several countries had similar politicians at roughly the same time. I see Reagan, Thatcher and the Ruud Lubbers as moderate right-libertarian reformers of a bloated welfare system, to be followed by Third Way politicians like Clinton, Blair and Wim Kok from left-wing parties, but who explicitly chose to break with traditional social democracy.

for ideological reasons, nobody wants to advocate for, or even much investigate, it, but the combination of a generation or two of socialism (to develop human capital) followed by liberalization (to unleash that capital) makes logical sense as a recipe for an undeveloped country’s net success–and fits the available data

How exactly do you think India’s human capital was developed when it was socialist?

Accessible (free/cheap) education seems to be the most successful socialist program that has ever existed.

Do you think India has (had) a better education system than comparable non-socialist countries? I haven’t seen evidence of that.

I suspect that they had a better education system than Pakistan and Afghanistan, as Orthodox madrassas seem to teach very poorly.

This assertion I would highly question. The ability of people to homeschool to great effect, and the cheap and successful schools set up in impoverished nations suggest that the West has settled on an education system that is ridiculously expensive and minimally effective. Its biggest advantage being that it is REALLY good for politicians who scream, “think of the children.”

I think there’s a selection effect in who chooses to homeschool that mean we shouldn’t assume that homeschooling would always work if done more broadly.

More importantly, the cost of homeschooling needs to take into account the labor of the parent involved. Total $/pupil/year spent in most states is between 10,000 to 20,000. So whatever parent is homeschooling instead earning money some other way during that time needs to either have low earning power or be super efficient to not be spending more than public school costs. Homeschooling may have benefits, but I don’t think being cheap is one of them.