[Thanks to Sarah H. and the people at her house for help understanding this paper]

The predictive coding theory argues that the brain uses Bayesian calculations to make sense of the noisy and complex world around it. It relies heavily on priors (assumptions about what the world must be like given what it already knows) to construct models of the world, sampling only enough sense-data to double-check its models and update them when they fail. This has been a fruitful way to look at topics from depression to autism to sensory deprivation. Now, in Relaxed Beliefs Under Psychedelics And The Anarchic Brain: Toward A Unified Model Of The Brain Action Of Psychedelics, Karl Friston and Robin Carhart-Harris try to use predictive coding to explain the effects of psychedelic drugs. Then they use their theory to argue that psychedelic therapy may be helpful for “most, if not all” mental illnesses.

Priors are unconscious assumptions about reality that the brain uses to construct models. They can range all the way from basic truths like “solid objects don’t randomly disappear”, to useful rules-of-thumb like “most get-rich-quick schemes are scams”, to emotional hangups like “I am a failure”, to unfair stereotypes like “Italians are lazy”. Without any priors, the world would fail to make sense at all, turning into an endless succession of special cases without any common lessons. But if priors become too strong, a person can become closed-minded and stubborn, refusing to admit evidence that contradicts their views.

F&CH argue that psychedelics “relax” priors, giving them less power to shape experience. Part of their argument is neuropharmacologic: most psychedelics are known to work through the 5-HT2A receptor. These receptors are most common in the cortex, the default mode network, and other areas at the “top” of a brain hierarchy going from low-level sensations to high-level cognitions. The 5-HT2A receptors seem to strengthen or activate these high-level areas in some way. So:

Consistent with hierarchical predictive processing, we maintain that the highest level of the brain’s functional architecture ordinarily exerts an important constraining and compressing influence on perception, cognition, and emotion, so that perceptual anomalies and ambiguities—as well as dissonance and incongruence—are easily and effortlessly explained away via the invocation of broad, domain-general compressive narratives. In this work, we suggest that psychedelics impair this compressive function, resulting in a decompression of the mind-at-large—and that this is their most definitive mind-manifesting action.

But their argument also hinges on the observation that psychedelics cause all the problems we would expect from weakened priors. For example, without strong priors about object permanence to constrain visual perception toward stability, we would expect the noise of the visual sensorium to make objects pulse, undulate, flicker, or dissolve. These are some of the most typical psychedelic hallucinations:

consider the example of hallucinated motion, e.g., perceiving motion in scenes that are actually static, such as seeing walls breathing, a classic experience with moderate doses of psychedelics. This phenomenon can be fairly viewed as relatively low level, i.e., as an anomaly of visual perception. However, we propose that its basis in the brain is not necessarily entirely low-level but may also arise due to an inability of high-level cortex to effectively constrain the relevant lower levels of the (visual) system. These levels include cortical regions that send information to V5, the motion-sensitive module of the visual system. Ordinarily, the assumption “walls don’t breathe” is so heavily weighted that it is rendered implicit (and therefore effectively silent) by a confident (highly-weighted) summarizing prior or compressive model. However, under a psychedelic, V5 may be forced to interpret increased signaling arising from lower-level units because of a functional negligence, not just within V5 itself, but also higher up in the hierarchy. Findings of impaired high- but not low-level motion perception with psilocybin could be interpreted as broadly consistent with this model, namely, pinning the main source of disruption high up in the brain’s functional hierarchy.

But F&CH are most interested in whether psychedelics can cause the positive effects we would expect of relaxed priors. If overly strong priors cause closed-mindedness, psychedelics should allow users to “see things with new eyes” and change their minds about important issues. These changes would be precipitated by the drug, but not fundamentally about the drug. For example, imagine a person who formed a strong prior around “I am a failure” at a young age, then later went on to achieve great things. Because their prior was so strong, they might think of each of their accomplishments as a special case, or interpret them as less impressive than they were. On psychedelics, they could reexamine the evidence unbiased by their existing beliefs, determine that their accomplishments were impressive enough to count as successes, and abandon the “I am a failure” prior. They would continue understanding that they were successful even after they sobered up, because the change of mind was a triumph of rationality and not a drug-fueled hallucination.

When I was young, I liked a fantasy book called The Sword of Shannara. The titular sword had an unusual magic power: it made the wielder realize anything he already knew. Neither a truly good person nor a truly bad person would benefit from the sword, but someone who was hypocritical, or deluding themselves, or complicit in their own brainwashing, would find all the parts of their mind flung together so hard that they couldn’t help but realize all the inconvenient facts they were trying to repress, or connect all the puzzle pieces previously scattered in separate mental compartments. Sometimes this resulted in a blinding revelation that you were on the wrong side, or had wasted your life; other times in nothing at all. F&CH argue that psychedelics are the real-life version of this, a way to make all of your beliefs connect with each other and see what results from the reaction.

These dignified scientists don’t like magic-sword related analogies, so they stick to regular-sword-related ones. “Annealing” is a concept in metallurgy where blacksmiths heat a metal object in a forge until it undergoes a phase change. All the molecules move to occupy whatever the lowest-energy place for them to occupy is, strengthening the metal’s structure. Then the metal object leaves the forge and the metal freezes in the new, better configuration.

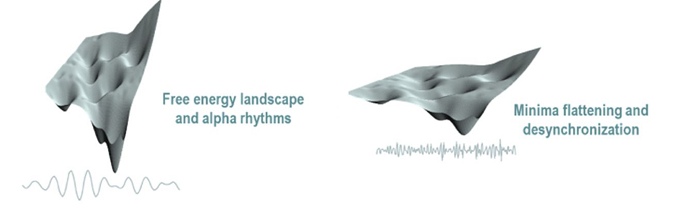

They analogize the same process to “flattening an energy landscape”. Imagine a landscape of hills and valleys. You are an ant placed at a random point in the landscape. You usually slide downhill at a certain rate, but for short periods you can occasionally go uphill if you think it would help. Your goal is to go as far downhill as possible. If you just follow gravity, you will end up in a valley, but it might not be the deepest valley. You might get stuck at a “local minimum”; a valley deep enough that you can’t climb out of it, but still not as deep as other places in the landscape you will never find. F&CH imagine a belief landscape in which the height of a point equals the strength of your priors around that belief. If you settle in a suboptimal local minimum, you may never get out of it to find a better point in belief-space that more accurately matches your experience. By globally relaxing priors, psychedelics flatten the energy landscape and make it easier for the ant to crawl out of the shallow valley and start searching for even deeper terrain. Once the drugs wear off, the energy landscape will resume its normal altitude, but the ant will still be in the deeper, better valley.

Here F&CH are clearly thinking of recent research that suggests MDMA treats post-traumatic stress disorder. Post-traumatic stress disorder is well-modeled as a dysfunctional prior, something like “the world is unsafe” or “you’re still in that jungle in ‘Nam, about to be ambushed”. Many PTSD patients have gone on to live good lives in well-functioning communities and now have more than enough evidence that they are safe. But the evidence doesn’t “propagate”; the belief structure is “frozen” in place and cannot be updated. If psychedelics relax strong priors, they can flatten the energy landscape and allow the ant of consciousness to leave the high-walled “the world is unsafe” valley and test the terrain in “the world is actually okay”. And since the latter is a deeper valley (more accurate belief) than the former, the patient will remain there after the drug trip wears off. This seems to really work; the effect size of MDMA on PTSD is very impressive.

But the authors want to go further than that. They write:

In this study, we take the position that most, if not all, expressions of mental illness can be traced to aberrations in the normal mechanics of hierarchical predictive coding, particularly in the precision weighing of both high-level priors and prediction error. We also propose that, if delivered well (Carhart-Harris et al., 2018c), psychedelic therapy can be helpful for such a broad range of disorders precisely because psychedelics work pharmacologically (5-HT2AR agonism) and neurophysiologically (increased excitability of deep-layer pyramidal neurons) to relax the precision weighting of high-level priors (instantiated by high-level cortex) such that they become more sensitive to context (e.g., via sensitivity to bottom-up information flow intrinsic to the system) and amenable to revision (Carhart-Harris, 2018b).

“Most if not all” psychiatric disorders. This has some precedent: some people are already thinking of depression as a high-level prior on negative perceptions and events, obsessive-compulsive disorder as strong priors on the subject of the obsession, etc. But it’s is a really strong claim, and Friston himself has previously published models of depression and anxiety that don’t obviously seem to mesh with this. I wonder if this is Carhart-Harris’ overenthusiasm for psychedelics running a little ahead of the evidence.

Speaking of Carhart-Harris’ overenthusiasm for psychedelics running a little ahead of the evidence, the paper ends with a weird section comparing the hierarchial structure of the brain to the hierarchical structure of society, and speculating that just as psychedelics cause an “anarchic brain” where the highest-level brain structures fail to “govern” lower-level activity, so they may cause society to dissolve or something:

Two figureheads in psychedelic research and therapy, Stanislav Grof and Roland Griffiths, have highlighted how psychedelics have historically “loosed the Dionysian element” (Pollan, 2018) to the discomfort of the ruling elite, i.e., not just in 1960s America but also centuries earlier when conquistadors suppressed the use of psychedelic plants by indigenous people of the same continent. Former Harvard psychology professor, turned psychedelic evangelist, Timothy Leary, cajoled that LSD could stand for “Let the State Dissolve” (Pollan, 2018). Whatever the interaction between psychedelic use and political perspective, we hope that psychedelic science will be given the best possible opportunity to positively impact on psychology, psychiatry, and society in the coming decades—so that it may achieve its promise of significantly advancing self-understanding and health care.

Sure, whatever. But this might be a good time to go back and notice some of the slight discordant notes scattered throughout the paper.

In a paragraph on HPPD, F&CH write:

Hallucinogen-persisting perceptual disorder (HPPD) is a Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th Edition–listed disorder that relates to enduring visual perceptual abnormalities that persist beyond an acute psychedelic drug experience. Its prevalence appears to be low and its etiology complex, but symptoms can still be distressing for individuals (Halpern et al., 2018). Under the REBUS model, it is natural to speculate that HPPD may occur if/when the collapse of hierarchical message passing does not fully recover. A compromised hierarchy would imply a compromised suppression of prediction error, and it is natural to assume that persistent perceptual abnormalities reflect attempts to explain away irreducible prediction errors. Future brain-imaging work could examine whether aspects of hierarchical message passing, such as top-down effective connectivity, are indeed compromised in individuals reporting HPPD.

In other words, the priors relax and don’t unrelax again after the drug experience.

For example, an especially common HPPD experience is seeing solid objects pulsate, ooze, or sway. It’s not surprising that a noisy visual system would sometimes put the edge of an object in one place rather than another. But usually a strong prior on “solid objects are not pulsating” prevents this from interfering with perception. Relax this prior too far and the pulsating becomes apparent. If the prior stays relaxed after the drug trip ends, you’ll keep seeing the pulsation indefinitely.

This is one of two plausible theories of HPPD, the other being that the hours of seeing objects pulsate makes your brain learn a new prior, “objects do pulsate” and stick to it. This would make more sense in the context of other learned permanent perceptual disorders like mal de debarquement.

F&CH include a section called “What To Do About The Woo?”, where they admit many people who have psychedelic experiences end up believing strange things: ghosts, mysticism, conspiracies. They are not very worried about this, positing that “a strong psychedelic experience can cause such an ontological shock that the experiencer feels compelled to reach for some kind of explanation” and arguing that as long as we remind people that science is good and pseudoscience is bad, they should be fine.

But I still worry that psychedelic woo is the cognitive equivalent of HPPD.

On one reading, it’s the failure of relaxed priors to re-strengthen, so that beliefs that previously had low prior probability – “this phenomenon is explained by ghosts”, “this guy at the subway station preaching universal love has really discovered all the secrets of the universe” – become more compelling. Spiritual beliefs are kind of a Pascal’s Wager type of deal – extremely important if true, but so unlikely to be true that we don’t usually pay much attention to them. If someone is walking around with a permanently flattened energy landscape – if all their probabilities are smushed together so that unlikely things don’t seem that much more unlikely than likely ones – then the calculation goes the other way, and the fascinating nature of these beliefs overcomes their improbability to make them seem worthy of attention.

On the other reading, they’re the result of newly-established priors in favor of ghosts and mysticism and conspiracies. People are not actually very good at reasoning. If you metaphorically heat up their brain to a temperature that dissolves all their preconceptions and forces them to basically reroll all of their beliefs, then a few of them that were previously correct are going to come out wrong. F&CH’s theory that they are merely letting evidence propagate more fluidly through the system runs up against the problem where, most of the time, if you have to use evidence unguided by any common sense, you probably get a lot of things wrong.

F&CH aren’t the first people to discuss this theory of psychedelics. It’s been in the air for a couple of years now – and props to local bloggers at the Qualia Research Institute and Mad.Science.Blog for getting good explanations up before the parts had even all come together in journal articles. I’m especially interested in QRI’s theory that meditation has the same kind of annealing effect, which I think would explain a lot.

But F&CH’s paper lends the theory a new level of credibility. Carhart-Harris is one of the pioneers of psychedelic therapy, and the paper looks like it’s intended to get people more interested in and accepting of that work by providing a promising theoretical basis. If so, mission accomplished.

““Annealing” is a concept in metallurgy where blacksmiths heat a metal object in a forge until it becomes molten. All the molecules move to occupy whatever the lowest-energy place for them to occupy is, strengthening the metal’s structure. Then the metal object leaves the forge and the metal freezes in the new, stronger configuration.”

Metallurgy nitpicks: Annealing often (but not always) involves a phase change, but both phases are solid and nothing melts. Additionally, annealing brings things into the softest (i.e. weakest) state, not a stronger one. Annealed steel is nice and easy to machine, but would make for a poor sword.

Thank you for correcting that. I could not stand the incorrect analogy. The fact that it becomes nice and easy to machine actually makes for a better analogy.

This was such an interesting article. I love it when phenomena are explained by energy fields, somehow it feels very intuitive. I wonder if psychedelic therapy will really be the answer to many problems of the human mind. I could see a lot of resistance from the drug manufacturers’ lobbyists if mental problems get solved so quickly. Anti-depressant industry is fairly big and I would assume that there are many deep-pocketed figures that want it to stay that way.

Thank you, I’ve made changes in that paragraph.

Not to nitpick, but you still say “strengthening the metal’s structure” and “new, better configuration.” As jimmy correctly notes, annealing softens metal, and while this is sometimes what you want, calling it “better” is a bit of a stretch. I’d just say “easier to work with”, which fits your analogy really well!

Sorry that your readership has such strong opinions on metallurgy.

Soft != Weak

Steel that’s excessively hard will be brittle.

“Soft” definitely equals “weak”. “Hardness” is a micro-scale measure of compressive strength and it correlates quite well with tensile strength. You can’t have “soft” and “strong” at the same time, but you can have “hard” and “weak” at the same time when the material is too brittle for the high small scale strength to translate to larger scales. In general though, “tough” != “strong”.

With swords, there’s quite a lot going on. Generally you want the initial work to be done on fairly soft steel, apply a hardening process, and then depending on sword type, tempering.

Hardening is basically the opposite of annealing – heat it up to annealing temperatures, then cool it down fast, to lock in the high-energy structure. Tempering involves raising hardened steel to a lower temperature, and cooling. It’s a bit harder to understand and I’m not sure whether it’s specific to the various phases in steel or whether it’s as universal as annealing and hardening. Anyway, tempering helps to increase elasticity, making a sword springy. So when a sword flexes to absorb the impact of a blow it doesn’t stay bent.

Japanese swords – e.g. katana – tend to be made using a differential hardening process, where the edge is hardened more than the body of the blade – so the edge stays sharp but the body doesn’t shatter. There’s no tempering. I think there’s also some clever work that means the carbon content of the sword isn’t uniformly distributed.

European swords tend to be tempered. I’ve seen a few references to “differential tempering” but they seem to be less widespread, many comparisons of European and Japanese sword-smithing leave it out. As far as I can tell, the result is that the swords tend to be less sharp, but more durable.

Quite how this all plays out as metaphors in general or metaphors for psychadelic therapy in particular is anyone’s guess.

While metallurgical annealing was the original inspiration, ‘simulated annealing’ as a computational optimisation method has been around since about 1980. I would guess the authors’ inspiration came via this rather than directly from metallurgy.

This is possibly the best segue I have ever read.

I was so amused by this I read it twice. Honestly, the whole piece was really well written. Definitely Post of the month material.

Could writing a note to yourself or affirming a few basic truths to yourself ahead of time- so you don’t reroll them- work?

Chanting to yourself “solid objects don’t move without a reason” and “ghosts aren’t real and magic isn’t real” for example.

I worry that conscious beliefs are really different from unconscious priors, and that’s why eg telling yourself “there’s nothing to be depressed about, my life is good” doesn’t cure depression, or why “that spider’s not even poisonous” doesn’t cure arachnophobia.

The “notes” are the difference between doing drugs and using drugs as treatment.

There are plenty of friend-to-friend or therapist-to-patient talks that go like “she’s obviously bad for you, why do you still keep trying?!” and answered with “I know, I know!” and two hours later sending a message to her.

Having the same kind of conversation in a flattened state might work a lot better. That’s probably what Purplehermann means by “notes” – a full chain of evidence that normally should change one’s opinion but doesn’t because of existing priors.

As a software guy, that reads a lot like stopping a program (administer drugs) so the IDE allows modifying the code (talk to the person while they’re receptive to new ideas), then restarting (drugs wear off) and hoping you didn’t fix one bug to introduce two new ones.

Considering the ideas people that do drugs a bit too much tend to have… I’d say that’s an accurate description.

I would love to say that this was meant as well =)

Yes, the arachnophobe part of the brain will reply, “it may not be poisonous, but it’s certainly venomous!”

Regarding conscious vs. unconscious beliefs, as I’ve mentioned before, it seems to me that psychedelics can aid in moving things from the former to the latter. Are you aware of any research that would either support or undercut that idea?

I’m not sure that’s right: there’s only one brain here, and I’m not understanding the model as including a separate ‘conscious’ part of the brain operating by different rules. Aren’t conscious beliefs just a particular sort of high-level prior?

I’m also not sure that this division is doing what you want it to. Someone who believes themselves to be a failure is conscious of believing that they’re a failure, even if they reject the belief analytically. The difficulty is that although they see the logical force of some argument like, “Failures cannot accomplish X; you have accomplished X; therefore you are not a failure,” it fails to shift their belief. But as you pointed out in Epistemic Learned Helplessness, there’s nothing very unusual or pathological about that.

You mean with psychedelics?

People are usually fully aware that they are tripping and that solid “objects don’t move without reason”. And yet they still see walls breathing and pretty patterns. But those patterns aren’t perceived as “real” in the same way outside world is “real”.

People can make visuals “stronger or “more noticeable” by focusing on them in a specific way. Or less strong. This works a little bit, but not that much.

But vision is a lot more low-level than beliefs in ghosts or magic. I don’t think you’d normally start believing in magic unless you were already somehow predisposed to it. I’d expect reminding yourself to work a lot better here.

If the belief is important/strong enough to you that you are willing to chant it before/after taking psychedelics to minimize the risk of it being altered by the psychedelic experience all acording to a paper you read on line because you are generally intersted in maintaing accurate priors and beliefs – that belief/prior is way to strong to be altered by anything but years of heavy psychedelic use.

Honestly, the ‘woo’ crowd is into ‘woo’ mostly not because of psychedelics but they are into psychedelics because it plays into their delusions/beliefs. There are exceptions, people who go off the rails after a single trip or, more often, it’s psychedelic use in conjuction with severe life distrurbances; death of a love one, job loss, etc.

Chanting things like that to yourself seems like a great way to get sectioned!

Really interesting, thanks!

“F&CH imagine a belief landscape in which the height of a point equals the strength of your priors around that belief.”

I think this should say “depth” rather than “height”, since the rest of the paragraph is talking about local *minima* and the *depth* of points corresponding to the compellingness of beliefs. (I know depth is “height” in the same sense as slowing down is “acceleration”, but using the word “depth” would be clearer and less open to misinterpretation.)

“Without any priors, the world would fail to make sense at all, turning into an endless succession of special cases without any common lessons. ”

Could this also explain why the room spins after too much alcohol?

That’s probably because the brain don’t get input/get wrong input from the sense of balance, in the inner ear.

Yes; there are actual physiological changes to the inner ear balance perception due to alcohol thinning the blood:

http://mentalfloss.com/article/12557/why-does-alcohol-cause-spins

Typo: “But it’s is a really strong claim” -> “But it is a really strong claim” or “But it’s a really strong claim”

I quite liked the term “relaxed priors” when I first heard it as I think it also explains many of the effects of sustained concentration meditation (samadhi). These include proprioceptive, auditory and visual hallucinations. “Wet insight” practice where you build up concentration then shift to mindfulness (vipassana) also makes a lot of sense under this model. Relax your priors then shift to sensory input to recalibrate. Consider a sustained, repeated meditation practice in a safe, stable environment. Might this not (for example) gradually reset assumptions of an unsafe world with relaxed priors and ongoing exposure to a peaceful space.

This theory certainly meshes well with my own experience. I took magic mushrooms a few times at regular doses, about 0.5-1 gram (in Canada we measure drugs with the metric system, this is one of a few cases where I dont know how to make the appropriate conversion). But then one time I took mushrooms two days in a row (protip: never do this), and when everyone else was clearly feeling the effects I was still sober, so I took an additional 1.5-2 grams (protip: never EVER do this) and smoked a big joint. What followed is the worst trip in my life where I was convinced of my impending death, eternal damnation to hell, and then walking around the city until 5am the next morning convinced the police was going to arrest me.

Despite this horrible experience, the next day and several days after, I had a profound feeling that it was a good thing I had gone through this, and that I was now a new person, changed for the better by my experience. Resetting my priors seems like a very good and parsimonious explanation for how I felt.

Agreed. Having “been there, done that”, I find this theory persuasive.

“When I was young, I liked a fantasy book called The Sword of Shannara. […]”

It’s the first time I saw someone recommend this series by stating something that would attract me (and I suppose not just me).

I’ve read this book. I remember it being a pulpy Lord of the Rings pastiche with some of its own wacky inventions thrown in. It has what I can only describe as the Arnold Schwarzenegger edition of Gandalf.

As Gandalf faces off against the Balrog in Moria:

Frodo: “Gandalf!”

Gandalf: “Git to de suhface.”

Frodo: “Noooooooooo!”

Gandalf: “Do eet! Do eet naowh!”

Now I want to read a take on Lord of the Rings where Gandalf speaks entirely in action movie one-liners.

I recall having very mild visual hallucinations on occasion while taking SSRIs (of the “those squigly lines on this bahtroom floor like kind of like they’re moving though I know they’re not” variety).

I think taking MDMA once or twice might have semi-permanently helped my social anxiety because it relaxed a prior I seemed to have that e.g. terrible things will for some reason happen if you show overt romantic interest in someone and they don’t reciprocate.

I read a study recently that supposedly a particular drug (forget which) temporarily made it possible, or at least theoretically possible, based on whatever model, for an adult to learn perfect pitch. Descriptions I’ve had of the experience of perfect pitch is that pitches have some kind of “C-ness” or “F-ness” about them that’s instantly perceptible the way color might be for others. One imagines that whatever one would need to pay attention to to form those “bins” might be the sort of thing the brain just stops looking for early on, if it ever was looking (there may not be any particular way to cause any baby to develop perfect pitch, even if they listen to complex tonal music all day).

This skill also seems related to learning native-like pronunciation for a language after adulthood: if your native language doesn’t distinguish, say, l and r, then your brain creates one “bin” to toss them both into and ignores the possibility that there’s a finer distinction there worth paying attention to when listening to and speaking other languages.

If I ever end up in a band we’re tuning to A432 just to annoy everyone with perfect pitch.

You will be in good evil company.

I have a band-mate with perfect pitch, and he’s not bothered by out of tune-ness. He even plays bagpipes.

Very interesting article which intuitively appears to make sense, even without relaxed beliefs!

On the topic of HPPD, I can tell you that back when I was using psychoactive compounds somewhat regularly, the ‘breathing walls’ were occasionally apparent in the days after an experience. This would occur when staring into blank space and daydreaming. In a period of a few weeks (of abstinence) I found that I could focus and exaggerate this effect, eventually being able to create it on demand. I soon realised that this wasn’t a particularly useful skill to have in one’s repertoire, and promptly put an end to the practice. Little conscious effort was required and it hasn’t occurred since (despite continued sporadic use of psychedelics). I couldn’t really say which of the two theories fit better with my experience, but the breaking down of the notion that “solid objects are not pulsating” seems somewhat more satisfying to me.

Same here — by closely watching a popcorn ceiling I could make it crawl like a snake. On the other hand, during one psilocybin experience I was fascinated to see patches of rainbow iridescence on the underside of well-lit clouds. I imagined, even at the time, that this was just an hallucination, however, years later, I see that those patches are really there, I just never noticed them before.

“Religious” thoughts/behaviors are the culprits.

Indeed they can be “really different” and very much the same, depending on the stance of perspective (context); or, what are the parameters of any given situation being examined. In other word’s, “degrees.” Think of PTSD and the fact that the same situation does not produce the same affect on different subjects; and, the mathematical “limit” when approaching a PTSD causing stimulus for any single subject.

When it comes down to it, they are two concepts. They intermingle with each other when building a “person.” Meaning that they each build with, on and in each other when we are considering a whole personal psych. Think, at which point does a conscious belief “become” an unconscious prior, within one self (subject)? Where is it that the subject gained the thought, “there’s nothing to be depressed about, my life is good”, and in what manners was this thought produced within a subject? In essence, a “cure for depression” could be said to be the precise moment that the conscious belief, “there’s nothing to be depressed about, my life is good,” becomes an unconscious prior.

To my main point here… Using the same ant from above, there are several ways to produce the “flattening” required for the ants development, and the mathematical “degree” is one process of producing different ‘ways’, along with the more obvious differencing process’ (different drugs, different modes of gaining information, dif. subjects, etc.) In other words, and to sum this up, the manners in which someone gains conscious beliefs seems to be of importance. For example, gained while under the influence of… fill in the blank; drugs, group of cohorts (“friend-to-friend”), business affair, war/trauma, teacher/student relation, food, hypnosis, psych/patient (“therapist-to-patient”), self/self, religious/spiritual, etc. I’m quite sure that this could all be experimentally accurate within lab settings.

What purplesherman points to has been named by many names, “mantra” is one of those names. I venture to say that this is the overall essence of “how humans learn”. The “energy landscape” here is a representation of “mental world” and it must be consistently recognized that this ‘mental world’ is dynamic and not static and develops highs and lows based on the other highs and lows in the system, including, the “base mental function” (ex. a base mind at birth; wether that’s a flat energy landscape or “pre-bumpy” does not matter here), and how those highs and lows become what they are can be seen as “learning”. Therefore, PTSD can be viewed as a high low area; the highs and lows are adjusted according to learning activity; the degrees between rapid and slow in the landscapes adjustment can be seen as the quality of the learning activity (dif. between trauma-rapid and schooling-slow). Perhaps the “flattening” is a widening use of senses. The more senses “open” or “interpreting external stimuli at a near full capacity” relates to the more rapid learning (and unlearning).

Thanks for the great reading!

Here’s a Qualia Research Institute post on REBUS: https://qualiacomputing.com/2019/08/27/carhart-harris-friston-2019-rebus-and-the-anarchic-brain/

I’ve never done drugs. I’ve never seen a need for them in my life. My (admittedly biased) perception of drugs is that they turn you into A: a damaged addict, B: an idiot or C: a weirdo. I know that there are exceptions to this rule, but… you know, priors are hard to adjust. I’m not saying my perspective if universal, but it’s a fairly widespread one throughout the squares of America.

Choosing to include stuff nonsense like the stuff printed above in a scientific paper raises my skepticism up from “maybe worth some controlled experimentation” to “those crazy kooks will try anything to get their LSD legalized, I am free to ignore everything else in this paper.”

I guess if you’re in a culture where drug use is more common, or have experimented with it yourself, someone saying that this compound could dissolve the state can be dismissed with a “sure, whatever.” For people not in that culture, however, it’s going to make you sound either ludicrous or dangerous. Either way, I’m not going to listen to your proposal. I don’t know if this is possible, but I’d highly recommend in the future avoiding weird inclusions like this; it actively hurts your credibility.

I understand your point but luckily that portion of America is unlikely to be reading this origonal research anyway. If you are already in the field of studying psychedelics, your peers are either on board or already think you are a weirdo, etc.

It’s also a bit ironic; you acknowledge that you & others have biased perspectives/priors on drugs/psychedelics which interferes with trusting a paper about how psychedelics relax the strength of priors.

I’m just thinking a few steps down the line. If the people writing this paper truly hold think that psychedelics hold the answer to treating most if not all psychiatric disorders, and want to actively pursue a future where their use is more widespread, then it naturally follows that they are going to have to break out of the field of studying psychedelics and start trying to convince people who aren’t already drinking the cool-aid.

I think most people can be convinced by an argument of “look, we realize this treatment regime may sound unorthodox, but… [insert convincing argument on priors/ Bayesian perspectives and how psychedelics can disrupt that error chain]” If the psychedelic researchers look like scientists and act like scientists, they’ll get treated like scientists. Appending a “oh yeah, by the way, dissolve the state disrupt politics” to the end of that argument is going to rubber band people back into viewing them as kooks.

Kooks don’t get political change to happen.

Why would they care about credibility with outsiders lacking usefully informed priors? It’s not a few steps down the line, it’s a paper written to a certain audience, one that is more sympathetic to psychedelics than you. And, within that community the oldest meme around is concerned with social “programming” (a kind of prior, perhaps), so this passing speculation makes sense at the end of the paper. It’s a little bit of a reach, but probably as likely as not to provide motivation and enthusiasm to the intended audience, rather than detract from the credibility, especially given who the author is.

Here’s the start of the second paragraph:

Here’s the last sentence last paragraph:

From start to finish, this paper is aware that psychedelics are in a state where they are fighting for legitimacy and for the first time in decades, there’s a chance they might win. This article is, on some level, an advocacy piece. That’s fine, great even! If he’s right and we can cure all mental illnesses with them, that sounds like a wonderful future to be in!

But as an advocacy piece, this the writers shoot themselves in the foot. Sure, the intended audience likely will be motivated by this kind of talk, but the intended audience is already using psychedelics.

This help’s Scott’s credibility, he pointed out that there are weird things in the paper.

I’m glad he brought the paper in general because it’s a really interesting idea.

Why would you think that the weird piece was an attempt to get LSD legalized? I thought it was either a joke, or a result of the people being weidos, quite possibly because of drugs. This doesn’t mean everything gets ignored, just subject to more skepticism.

It seems like you possibly aren’t realizing the difference between Scott’s views and the paper he is representing

Reading my original post, I can see that my use of the word “you” was unspecific. I was referring to the scientists, not Scott. Including this detail in Scott’s write-up of the paper raises my perception of Scott’s credibility (well, not really. It’s likely already capped out).

Deciding to include that piece in the original paper, however, lowers my perception of the credibility of the people who wrote it. I don’t think Scott’s article was a push to get LSD legalized, I think that the underlying push of the paper as written is to expand access to LSD.

Hopefully this clears up confusion, sorry for not being clearer in my writing.

That makes a lot more sense.

Do you think adding the ‘dissolution of the state’ makes it more likely they are making things up to push for legalization, or do you just think it makes people more likely to take the paper that way?

I’m walking into this argument relatively uninformed about the potential positive benefits of drug use, but hyper-aware of the negatives. I’m also aware that in the past, people who have sought to expand access to drugs made a bunch of convincing-sounding arguments about all the great things drugs would do that turned out to be either incorrect or massively overstated. For example: see pretty much every claim made by marijuana advocates other than “it’s my life and I want to get high.”

I’m also aware that I’m not an expert in this topic. They are. When they present evidence or declare that they’ve successfully proven a point, I’m largely taking that fact on faith. Sure, I can follow their train of logic, but I’m not a neuropharmacolologist (or whatever), I don’t have the background or interest to learn about how/why the brain responds in certain ways. I also have no experience with psychedelics, I can only trust their account of what they do.

I’m willing to trust them when they are talking and acting like credible researchers, but when stuff like “dissolve the state” slips in, I stop seeing them as credible researchers and start seeing them more as kooks. This makes every previous argument less believable.

The irony of the ‘dissolution of the state’ is that it was the CIA’s Project MKUltra that turned on Ken Kesey, giving us the Merry Pranksters and the Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test, leading to the Grateful Dead, and turned on Robert Hunter, their lyricist.

Aftagley you are assuming that these people, who seem pretty smart, have a specific agenda in writing this paper- getting lsd legalised (which usually requires appealing to people outside their circles). You also noticed that others who aren’t in that field are less likely to take them seriously when putting in weird stuff like this.

So you seem to think that smart people have a main agenda which they are sabotaging, and if they weren’t sabotaging this agenda you’d be more willing to believe that they don’t have this agenda.

Could you explain why this is logical?

(Please note that I’m fairly anti-drugs, and am occasionally guilty of lecturing people on the evils of legalizing marijuana, and am not an expert in psychedelics, so we’re have similar priors in regards to the actual subject matter, but your thread of logic doesn’t make sense to me)

Purplehermann, you asked

I don’t think that Aftagley is assuming that they have an agenda of legalizing LSD, only that it is possible, and that dissolution of the state comments make it more likely.

Suppose that a researcher can be a “kook” or a “suit”. A kook lacks scientific integrity and says whatever he wants to promote legalizing his favorite drug. A “suit” is trying his best to find the truth, and has no political agenda. You don’t know if a researcher is a kook or a suit a priori. You have to infer it from the article. If you consider the probability the article is a good faith attempt at discussing the current research, P(real), you can break it up as:

P(real) = P(real | kook) * P(kook) + P(real | not kook) * (1 – P(kook))

Obviously, P(real | kook) << P(real | not kook).

All Aftagley is saying is that comments about the dissolution of the state cause a Bayesian update of P(kook), so P(real) should go down.

I generally agree with all of this, and the reason this is important is because people's priors on P(kook) when it comes to psychedelic research probably average much higher than for (say) particle physics research. If you write a paper in this domain, you should bend over backwards to not be seen as a kook. Since these are smart researchers, one can only conclude that they are either writing for a different audience with lower priors on P(kook), that they are not good at rhetoric, or that they indeed share some goals with the kooks.

Re turning into a “damaged addict”: two of the most common psychedelics, psilocybin (magic mushrooms) and LSD are entirely non-addictive. They’re also non-toxic at any reasonable dose, including so-called “heroic” doses.

Different drugs have different effects and different risks. Don’t treat them all the same.

I know. I don’t think that the person collapsed on the sidewalk outside my apartment this morning was in that state because she took shrooms or LSD. Whatever chemical did that to her, however, has the same top-level categorization as the those two, however, in that they’re all “drugs.”

But our society treats them the same. If I wanted to buy them, I’d have to financially engage with the same criminal organizations that could sell me other, far more dangerous compounds. If I tested positive for those compounds in one of my periodic tests, I would lose my job. The only time I ever see these compounds in real life is at parties/festivals where lots of other illegal substances are being consumed.

This is the bias psychedelic advocates are going up against. You’ll have to convince us why psychedelics SHOULDN’T be in the same category as cocaine, heroin and meth. Arguments like you presented above are a great way to do this, referencing society dissolving is not.

Point of order: cocaine and meth are legal for medical uses in the US as Schedule II drugs. Heroin is not (though it is in the UK), and most psychedelics are not, all being Schedule I which legally claims they have no medical use.

Moving these drugs from Schedule I to Schedule II so that they can be used in appropriate medical treatment is a much larger perception change than it is a policy change. That is, most psychiatrists are unlikely to start using or recommending acid trips, even if legal (thoughts, Scott?) and it will likely fall to a small set of specialists in certain disorders who want to deal with the paperwork headaches.

Having lived in the Netherlands for several years, I felt like legal recreational access to marijuana and psilocibin were working out pretty well. On the rare occasions when we wanted one, we were able to pick up a nicely rolled joint in an establishment that resembled a Starbucks. Truffles came nicely packed and measured with detailed instructions. Criminals might have been involved somewhee in the supply chain, but the retail end seemed entirely legit and no interaction with shady characters was required of us. So a lot of the social evils associated with these things in the US seemed greatly mitigated, if not absent.

Previous tolerance for harder drugs had not worked out so well; contrary to popular American belief, all drugs are not legal over there. But drug-related offenses are treated differently, and there is a significant band of non-punitive responses to drug abuse such that putting someone in jail is not the first or only response.

What reads as a culture of permissiveness to Americans is actually very conservative in practice. There is a great emphasis on avoiding “antisocial” behavior. So can you can weed and trip on shrooms in a few proscribed ways where it doesn’t bother anyone else, and for just about everyone that works. It’s sort of telling that the drugs which turned out to be impossible to tolerate were those that couldn’t “stay in their box”. A lot of the capacity for drugs to ruin someone’s life now seem to be artificially imposed in the US, especially when it comes to marijuana. Although it’s worth noting that alcohol seemed to be by far the most personally and socially destructive substance in both countries and no one seriously advocated limits on that. I also rolled my eyes at the “dissolving the state” line because to me it seemed like a strong state with the right policies can do a lot to protect people inclined to use recreational drugs from themselves and others while also protecting society as a whole from substances whose chaos:pleasure ratio is just too damn high.

One can get addicted without any chemicals, like to gambling or porn. It is not the chemical in itself addictive but the activity of doing something that is fun, and the brain gets addicted to things that are fun. If LSD or mushrooms are at least as much fun as gambling or masturbation and at least as easy to do daily, taking them (the activity) is addictive. The activity, not the chemicals.

The relevant chemical is the brain’s own dopamine, not the drug. Dopamine is basically a learning through reinforcement kind of system. One part of the brain thinks this activity is good for us and rewards the rest with a dopamine rush. The rest thinks wow, this activity leads to that good feeling, let’s do it more. That is addiction. The difference between being addicted to porn vs. liking it when you get a promotion at work is that you do not get daily promotions and porn is likely a stronger dopamine rush.

Psychedelics are anti-addictive, in a way. The mind state they create is interesting, often pleasant, but very much overwhelming. You don’t really want to repeat the experience for some time (measured in weeks) – there is a kind of tiredness akin to returning home after a very intense and adventure-filled day, where you’d just like to chill for a while instead and process everything that happened.

Also, the rapid buildup of tolerance means that redosing during the trip usually doesn’t do anything, and anything you’ll take within a few days from the trip will have extremely dimnished effect as well.

How do we normally convince people’s unconscious/subconscious priors that ghosts aren’t real?

If we have that methodology, shouldn’t that be able to accomplish the same results as above without the use of psychedelics?

That would be ‘start over as a newborn’ therapy, or would it?

I don’t know. People can lose their unconscious religious beliefs to very strong extents afaik. If the solution to psychogical issues is just strong bayesian updating on difficult areas, then we do already know of lots of areas and methods that work for this.

Appreciation journals and loving-kindness meditation are already established effective treatments for some things. That would mirror unconscious bayesian belief updating. That would imply a large possible set of possible methods that are still available to be discovered to fix things using that methodology.

Or perhaps these could be combined with psychadelics to lead to faster changes? A conterargument I’ve read to that is that the more you try to consciously control an experience, the riskier things become towards having a bad trip.

Appreciation journals and loving-kindness meditation are already established effective treatments for some things.

Yeah… but… I remember two folks where convinced they (physically) “saw” the “little people”, or a kind of gnome, resp.. Both had gone through early childhood trauma. I think if even the interpretation of raw sensual data is affected, it will need more than a journal and CBT (with, in these cases, confrontations with camera records of those moments, if that ever was possible).

Or perhaps these could be combined with psychadelics to lead to faster changes? A conterargument I’ve read to that is that the more you try to consciously control an experience, the riskier things become towards having a bad trip.

That might be a matter of lacking research for the best controls. My guess is that a doctor/therapist would be helpful for a 1) preparation (providing narratives, play-acting (for muscle memory), words, and concepts to help making sense and to guide the forming of new priors; 2) accompanying and guidance during the shake-up of priors; 3) processing and assistance in realizing the new beliefs in everyday life.

Come to think of it, psychiatry might partly adopt/adapt the old structure of initiations in primitive tribal societies, in an inpatient clinic setting. This would probably take several days or even weeks around one, or a short series of, drug sessions.

Also, the bad trips might be just the right thing to re-experience in order to release, only in too high intensity.

Releasing priors implicates a release of repression (“the brain’s functional architecture ordinarily exerts an important constraining and compressing influence “ that is lowered). It would be interesting to see research into whether released priors will disappear quietly, or will be experienced; “bad” trips then would mean: in uncontrollable intensity. Intensity might be open to moderation through dosage, trip frequency, setting, preparation, etc.

Fascinating speculations…

I have a good friend who was diagnosed with cancer a few years ago, and experienced some fairly significant depression as a result. He was on Prozac for a while but hated it. Then he found someone in Berkeley that was treating depression with psilocybin — each session involves taking 5 grams of mushrooms and sitting blindfolded (!) in a room listening to music, among other things. He does this every 6 months or so.

The results were/are astonishing. Essentially cured, he describes it has having his computer rebooted… perhaps clearing those new, destructive beliefs in the process.

5 grams is a pretty solid dose…I’m not sure I would be entirely comfortable being blindfolded after taking that much (or any…actually I just wouldn’t be comfortable being blindfolded for an extended period whether mushrooms were involved or not).

I’m guessing that “blindfolded” is just an unfortunate and somewhat misleading choice of words. In therapeutic settings it is typical to put on a sleep mask (easily removable if desired) and listen to high-quality music such as the Johns Hopkins psilocybin playlist.

Does the word “blindfold” imply lack of consent or ill will? I’d never infer that meaning myself.

It doesn’t necessarily imply that it is forced or that you can’t remove it at will, but that is how I read it initially. Might have just been an interpretation problem on my end.

Thanks, could be that word does imply something dark without the right context. And when the context here is “5 grams” (!!), well… I get it.

flye, I’m somewhat bemused by your “(!!)” reaction to 5 grams of magic mushroom. My impression is that therapeutic doses are generally on the higher end compared to the dosage of a recreational user; 5 g of cubensis is what I’d consider a middle-of-the-road dose. With that dose I’m laying down wearing a sleep mask and playing music on headphones for about the first 2 hours.

On the other hand, individual response varies a lot, so YMMV.

Try wearing a blindfold and then report back if there’s any meaningful difference.

Devil’s advocate: the “normal”, non-woo belief system that most people have is the result of strong priors imposed basically via social pressure, rather than actually best fitting the available evidence per se. If someone stops believing this after going through a prior-shaking annealing cycle, maybe they’ve become closer to correct, rather than further.

Folks may also be interested in reading Sarah’s paper (cited by F&CH). Her model is that psychedelics lead to decomposed (more granular) predictions with higher rates of prediction error, and the brain’s attempt to minimise those errors in various ways can explain the likes of hallucination, time dilation, lasting after-effects, ego death, etc. One cool nugget: another way to think about “set and setting” is that set = top-down predictions from the brain, and setting = bottom-up environmental data.

The comments form won’t let me post the link, but if you google “Perception is in the Details: A Predictive Coding Account of the Psychedelic Phenomenon” it’s there.

The mind illuminated spends a chapter (p113) explaining “How mindfulness actually works”. It describes the “magic” of mindfulness as being able to cast direct non judgemental attention onto deeper and deeper priors. Starting with “Anger is an appropriate response to situation X” all the way back to the nature of suffering and existince.

The question seems to me to be: does casting attention onto priors in this way lead to more accurate beliefs? People who practice mindfulness seem often to have different beliefs about the nature of suffering and existence than people who do not, but that is consistent with mindfulness being a sort of self-induced hallucinatory state.

I guess it’s the same problem as indicated in the OP: weakening your priors might cause you to shift to a deeper, better valley in belief space, but it might also cause you to shift to believing nonsense.

Priming may play a role here. In the model: Even if the energetic landscape is flattened, there may be influential differences in the form of new minima, or transitional grooves, that have been established beforehand, e.g. through preparation sessions for the drug session, through teaching, cultural narratives, or therapy.

The model needs a mechanism to show how conscious action, e.g. in CBT, can set such a potential new prior.

What if you had managed to get over your trauma and realize life was worth living? Do we really want to reroll on that belief?

Assuming the claims in the paper are true, I wonder if the same process could be used to treat not just figurative but also literal myopia. I remember reading that the type of nearsightedness caused by kids spending too much time indoors is partially neurological—basically the brain ends up thinking that everything in the world is in fact really close. Maybe it would be possible to use psychedelics to “reset” that prior?

You know, if you read enough trip reports, you sometimes do see people commenting about changes in their vision: typically claiming better color perception, but also better vision in general. One wonders.

FWIW, my myopia actually DOES get better on psychedelics, in the sense of the brain getting more creative about filling in the blanks and sharpening the edges.

However, putting on glasses helps a lot more.

Myopia may be “partially neurological”, but it’s definitely a problem of physical geometry of the eye – I can sort of fix it temporarily by pulling on the skin outside of the eye, and gently flattening the eyeball.

from the tiny amount of knowledge I have about photoreceptors and the areas of the brain that interpret imaging and light, that blows me away

For B/W contrast and depression it has been established that Contrast vision relies on so-called amacrine cells within the retina, which horizontally connect the retina’s neurons called ganglion cells with each other. These cells rely on dopamine, … (source)

Don’t know for color contrast or vividness, though.

My very first psychedelic trip (which was DMT, for the record), was followed by my nearsightedness becoming markedly less severe (went from about a -3.5/-4 to around a -1/-2; in both cases my left eye is somewhat worse than my right); my depth perception became somewhat better (I became a much better bowler), but this effect went away after 1-2 months. Subsequent psychedelic trips were not associated with anything like this. I also have protanopia which makes my color perception significantly different from that of those around me; this wasn’t affected by psychedelic use*.

*On psychedelics I sometimes have the impression of seeing colors I’ve never seen before, but I find them very difficult to describe and cannot visualize them after the trip is over.

I was under the impression that this is how you get flesh interfaces.

Fanfic request: Mother Horse Eyes x Friston

(Link for the curious, please read: https://www.reddit.com/r/9M9H9E9/wiki/narrative)

As a moderately depressed person, I’d say my experience with psylocybin mushrooms is that things seem just… okay. A veil is lifted, trees are really trees, rain is really rain. Things appear the way they did in childhood, before being reduced to a barely-noticed symbol. All the contortions of thought that seem really stressful in the “normal” state of mind seem like not a problem at all. Life feels good, in a vaguely spiritual way.

Then the trip ends. Over several days the old patterns reassert themselves, sometimes in a less severe permanent form. I wouldn’t call psychedelics a miracle cure, but they’re definitely helping.

A curious effect is that much of the same is caused by travel. Physical change of surroundings seems to force the brain to pay attention to things again, and I’ve seen it also in other depressed people.

Relaxing priors matches perfectly my LSD experience. My impression was that it is not putting new things like hallucinations inside my mind, it just turned off my expectations, inner monologue so that I could really pay attention to what I am seeing and hearing. It focused my attention outside, not inside.

This happened in the context of electronic music like techno. Psychedelic and similar drugs are well known to be popular at such parties, raves. This is because there is more to that music that first hits the ear. While a track from a car audio just sounds like synth and drums going on, if you just put on some quality headphones, lie down in bed in a dark room and close your eyes, you will realize that it has 16 tracks going on at the same time, not just 2-3. Those tracks are just less loud. Psychedelics similarly help paying attention to details in the music.

It seems to me that three kinds of things can happen under the influence of psychedelics. With relaxed priors, you interpret reality weirdly, so you hallucinate. This never happened to me. Not under drugs at least. Under fever, yes. Or you just pay really close attention to reality and just get blown away by all the details you never noticed. Or you have that famous spiritual satori all is one experience. This comes from both relaxed priors but also not really playing much attention to outside reality either. You just… exist. And it is… really fun. Happiest thing ever.

Then I didn’t really want to get used to drugs so I did what people told me, to try to recreate it with meditation. It sometimes worked. Not very reliably, but sometimes. That is, sometimes able to pay more attention to reality and sometimes this satori. This very vibrant awareness. From turning off the internal dialogue.

I think this is what Owen Barfield called Original Participation. Look that up. It is refreshing to have a non-Eastern and not even overly mystical approach to it. Although still mystical, still based in Steinerian Anthroposophy.

As usual, I don’t understand the free energy thing. I understand the relaxed Bayesian priors but just not idea what the eff free energy is…

This happened in the context of electronic music like techno. Psychedelic and similar drugs are well known to be popular at such parties, raves. This is because there is more to that music that first hits the ear.

The music (the rhythm, probably) has its own psychedelic properties. Here’ s some useless knowledge I picked up:

– At some rave parties an artist projected movies on the wall: snaking bands, or pulsation grids of large polka dots. (Is that a regular — reinforcing? — part of house music events?)

– When seeing strobing lights in certain frequencies (and (poly)rhythms?), probands reported spontaneous vision of whitish polka dots. That was not from an external image; they had something like halved table tennis balls over their eyes.

– Cave paintings have been found that display an overlay of a grid of white polka dots.

Conclusion: Mating strategies in girls have come a long way…

(Sorry for the fuzzy weasely anecdote quality.)

Regarding the “weird section comparing the hierarchial structure of the brain to the hierarchical structure of society,” this seems analogous to, if not an example of, Conway’s Law, that is: “organizations which design systems … are constrained to produce designs which are copies of the communication structures of these organizations.”

In my experience, a lot of societal structures also exhibit something that looks a lot like predictive processing dynamics.

Anyone working in a large hierarchical structure knows that “predictions” come down from the top (i.e. “these projects will be completed at this time”), while “sense inputs” come up from the bottom (i.e. “the foo-api can’t talk to the bar-api because they have differing underlying assumptions about rates of dataflow, and we can’t fix them because we’re all prioritizing the baz intiative”), at which point layers in the middle resolve these conflicts, sometimes by telling the bottom, “the senses are wrong!” (i.e., “We need to come in weekends”) or telling the top that priors are wrong (i.e. “these projects required more investment than was initially realized”).

“walking around with a flattened energy landscape” is actually very helpful in allowing me to understand the experiences I previously had.

I had very strong priors growing up. Went through tramua / growth phase, including some pyschedelics, and most (but somehow not all priors) were flattened, and then they seem to have re-emerged in the period afterwards when i regrew most of my beliefs from first principles. Somehow the “physics” and “math” priors managed to avoid not getting flattened, while almost everything else did.

The hardest thing about having a flattened belief landscape is that you lose any ability to make value judgements. If you think all outcomes are about equally likely at all times, then the concept of value becomes meaningless. I went into that place because i knew value was both “extremely important” and something I didn’t really understand. I came out of it with a much better-defined value system than I had going in.

I realized at some point afterwards that the shift in my thinking could be summarized by the belief that washing a dish all the way is better than washing it partially, and leaving some dirt or soap scum on it. I understood that, during the mystic (“flat belief landscape”) phase, I would have challenged this judgement, saying something like “but what if (unlkely sequence of events) causes, afterwards, it to have been better to have not washed the dish all the way?”

By explicitly rejecting value statements as having meaning, I was effectively flattening the belief landscape. My intention was just to understand value, and the more i looked at the concept, the less sense it made. Destorying that concept made my life into a mess, and then eventually i fixed it by latching onto a few values (such as loving my family and wanting them not to worry), at which point the value system (and thus the probability landscape) regrew themselves.

During the recovery phase, I _knew_ that this “what if you really want somewhat dirty dishes” belief was silly, but I hadn’t generalized it by connecting it to a flattened probability landscape. If the true probability landscape IS flat, then maybe you DO want dirty dishes. But it’s not flat at all, and you really want your dishes _clean_, not in various states of cleanliness.

The hardest thing about having a flattened belief landscape is that you lose any ability to make value judgements. If you think all outcomes are about equally likely at all times, then the concept of value becomes meaningless.

Did this only affect thinking, or where you also unable to decide (aboulia), or act?

It wasn’t aboulia at all. I think this was more like, I had a strong prior that the _concept_ of value was meaningless. So individual drive still made sense, but it’s like i was rejecting any attempt by my brain to conceptualize value because i couldn’t map that notion into physics or math. Until I eventually found valid a notion of value that pops naturally out of physics, it was like individual drives and motives could exist, but i refused to stitch them together into a coherent model, because doing so seemed to violate the priors i’d somehow latched onto that “only things which can be either translated into mathematical models, or statements about physics, can be truth.”

I think the whole value-flattening thing and subsequent harsh contact with reality lead to a new prior, basically “act normal (by following the expectations of people around you) as until figure out how reality works”

Thank you. This reminds me of the “suchness” of things in Buddhism (tathātā, dharmatā) — they are what they are, anything of meaning (in the meaning of life sense, not semantic) we glue onto them is just illusion. But a quick glance at your blog indicates some other insights.

Your anchoring in math or physics is interesting, in that it looks at something eternal and fundamental to a reality that is supposedly able to exist without our contributions. (Not going into philosophical depths here, simulation, thing-in-itself etc.).

Bookmarked your blog for reading ASAifindfreetime.

Is there overlap between the concept of “relaxed priors” and the concept of “suggestibility” as we might see in children or people with borderline or dependent personality disorder? Are they both related to a weak sense of the self-concept? This would also explain the overlap with meditation.