[Previously in sequence: Epistemic Learned Helplessness]

I.

“Culture is the secret of humanity’s success” sounds like the most vapid possible thesis. The Secret Of Our Success by anthropologist Joseph Henrich manages to be an amazing book anyway.

Henrich wants to debunk (or at least clarify) a popular view where humans succeeded because of our raw intelligence. In this view, we are smart enough to invent neat tools that help us survive and adapt to unfamiliar environments.

Against such theories: we cannot actually do this. Henrich walks the reader through many stories about European explorers marooned in unfamiliar environments. These explorers usually starved to death. They starved to death in the middle of endless plenty. Some of them were in Arctic lands that the Inuit considered among their richest hunting grounds. Others were in jungles, surrounded by edible plants and animals. One particularly unfortunate group was in Alabama, and would have perished entirely if they hadn’t been captured and enslaved by local Indians first.

These explorers had many advantages over our hominid ancestors. For one thing, their exploration parties were made up entirely of strong young men in their prime, with no need to support women, children, or the elderly. They were often selected for their education and intelligence. Many of them were from Victorian Britain, one of the most successful civilizations in history, full of geniuses like Darwin and Galton. Most of them had some past experience with wilderness craft and survival. But despite their big brains, when faced with the task our big brains supposedly evolved for – figuring out how to do hunting and gathering in a wilderness environment – they failed pathetically.

Nor is it surprising that they failed. Hunting and gathering is actually really hard. Here’s Henrich’s description of how the Inuit hunt seals:

You first have to find their breathing holes in the ice. It’s important that the area around the hole be snow-covered—otherwise the seals will hear you and vanish. You then open the hole, smell it to verify it’s still in use (what do seals smell like?), and then assess the shape of the hole using a special curved piece of caribou antler. The hole is then covered with snow, save for a small gap at the top that is capped with a down indicator. If the seal enters the hole, the indicator moves, and you must blindly plunge your harpoon into the hole using all your weight. Your harpoon should be about 1.5 meters (5ft) long, with a detachable tip that is tethered with a heavy braid of sinew line. You can get the antler from the previously noted caribou, which you brought down with your driftwood bow.

The rear spike of the harpoon is made of extra-hard polar bear bone (yes, you also need to know how to kill polar bears; best to catch them napping in their dens). Once you’ve plunged your harpoon’s head into the seal, you’re then in a wrestling match as you reel him in, onto the ice, where you can finish him off with the aforementioned bear-bone spike.

Now you have a seal, but you have to cook it. However, there are no trees at this latitude for wood, and driftwood is too sparse and valuable to use routinely for fires. To have a reliable fire, you’ll need to carve a lamp from soapstone (you know what soapstone looks like, right?), render some oil for the lamp from blubber, and make a wick out of a particular species of moss. You will also need water. The pack ice is frozen salt water, so using it for drinking will just make you dehydrate faster. However, old sea ice has lost most of its salt, so it can be melted to make potable water. Of course, you need to be able to locate and identify old sea ice by color and texture. To melt it, make sure you have enough oil for your soapstone lamp.

No surprise that stranded explorers couldn’t figure all this out. It’s more surprising that the Inuit did. And although the Arctic is an unusually hostile place for humans, Henrich makes it clear that hunting-gathering techniques of this level of complexity are standard everywhere. Here’s how the Indians of Tierra del Fuego make arrows:

Among the Fuegians, making an arrow requires a 14-step procedure that involves using seven different tools to work six different materials. Here are some of the steps:

– The process begins by selecting the wood for the shaft, which preferably comes from chaura, a bushy, evergreen shrub. Though strong and light, this wood is a non-intuitive choice since the gnarled branches require extensive straightening (why not start with straighter branches?).

– The wood is heated, straightened with the craftsman’s teeth, and eventually finished with a scraper. Then, using a pre-heated and grooved stone, the shaft is pressed into the grooves and rubbed back and forth, pressing it down with a piece of fox skin. The fox skin becomes impregnated with the dust, which prepares it for the polishing stage (Does it have to be fox skin?).

– Bits of pitch, gathered from the beach, are chewed and mixed with ash (What if you don’t include the ash?).

– The mixture is then applied to both ends of a heated shaft, which must then be coated with white clay (what about red clay? Do you have to heat it?). This prepares the ends for the fletching and arrowhead.

– Two feathers are used for the fletching, preferably from upland geese (why not chicken feathers?).

– Right-handed bowman must use feathers from the left wing of the bird, and vice versa for lefties (Does this really matter?).

– The feathers are lashed to the shaft using sinews from the back of the guanaco, after they are smoothed and thinned with water and saliva (why not sinews from the fox that I had to kill for the aforementioned skin?).

Next is the arrowhead, which must be crafted and then attached to the shaft, and of course there is also the bow, quiver and archery skills. But, I’ll leave it there, since I think you get the idea.

How do hunter-gatherers know how to do all this? We usually summarize it as “culture”. How did it form? Not through some smart Inuit or Fuegian person reasoning it out; if that had been it, smart European explorers should have been able to reason it out too.

The obvious answer is “cultural evolution”, but Henrich isn’t much better than anyone else at taking the mystery out of this phrase. Trial and error must have been involved, and less successful groups/people imitating the techniques of more successful ones. But is that really a satisfying explanation?

I found the chapter on language a helpful reminder that we already basically accept something like this is true. How did language get invented? I’m especially interested in this question because of my brief interactions with conlanging communities – people who try to construct their own languages as a hobby or as part of a fantasy universe, like Tolkien did with Elvish. Most people are terrible at this; their languages are either unusable, or exact clones of English. Only people who (like Tolkien) already have years of formal training in linguistics can do a remotely passable job. And you’re telling me the original languages were invented by cavemen? Surely there was no committee of Proto-Indo-European nomads that voted on whether to have an inflecting or agglutinating tongue? Surely nobody ran out of their cave shouting “Eureka!” after having discovered the interjection? We just kind of accept that after cavemen working really hard to communicate with each other, eventually language – still one of the most complicated and impressive productions of the human race – just sort of happened.

(this is how I feel about biological evolution too – how do you evolve an eye by trial and error? I’ve read papers speculating on the exact process, and they make lots of good points, but I still don’t feel happy about it, like “Oh, of course this would happen!” At some point you just have to accept evolution is smarter than you are and smarter than you would expect to be possible.)

Taking the generation of culture as secondary to this kind of mysterious process, Henrich turns to its transmission. If cultural generation happens at a certain rate, then the fidelity of transmission determines whether a given society advances, stagnates, or declines.

For Henrich, humans started becoming more than just another species of monkey when we started transmitting culture with high fidelity. Some anthropologists talk about the Machiavellian Intelligence Hypothesis – the theory that humans evolved big brains in order to succeed at social maneuvering and climbing dominance hierarchies. Henrich counters with his own Cultural Intelligence Hypothesis – humans evolved big brains in order to be able to maintain things like Inuit seal hunting techniques. Everything that separates us from the apes is part of an evolutionary package designed to help us maintain this kind of culture, exploit this kind of culture, or adjust to the new abilities that this kind of culture gave us.

II.

Secret gives many examples of many culture-related adaptations, and not all are in the brain.

Our digestive tracts evolved alongside our cultures. Specifically, they evolved to be unusually puny:

Our mouths are the size of the squirrel monkey’s, a species that weighs less than three pounds. Chimpanzees can open their mouths twice as wide as we can and hold substantial amounts of food compressed between their lips and large teeth. We also have puny jaw muscles that reach up only to just below our ears. Other primates’ jaw muscles stretch to the top of their heads, where they sometimes even latch onto a central bony ridge. Our stomachs are small, having only a third of the surface area that we’d expect for a primate of our size, and our colons are too short, being only 60% of their expected mass.

Compared to other animals, we have such atrophied digestive tracts that we shouldn’t be able to live. What saves us? All of our food processing techniques, especially cooking, but also chopping, rinsing, boiling, and soaking. We’ve done much of the work of digestion before food even enters our mouths. Our culture teaches us how to do this, both in broad terms like “hold things over fire to cook them” and in specific terms like “this plant needs to be soaked in water for 24 hours to leach out the toxins”. Each culture has its own cooking knowledge related to the local plants and animals; a frequent cause of death among European explorers was cooking things in ways that didn’t unlock any of the nutrients, and so starving while apparently well-fed.

Fire is an especially important food processing innovation, and it is entirely culturally transmitted. Henrich is kind of cruel in his insistence on this. He recommends readers go outside and try to start a fire. He even gives some helpful hints – flint is involved, rubbing two sticks together works for some people, etc. He predicts – and stories I’ve heard from unfortunate campers confirm – that you will not be able to do this, despite an IQ far beyond that of most of our hominid ancestors. In fact, some groups (most notably the aboriginal Tasmanians) seem to have lost the ability to make fire, and never rediscovered it. Fire-making was discovered a small number of times, maybe once, and has been culturally transmitted since then.

But it’s not just about chopping things up or roasting them. Traditional food processing techniques can get arbitrarily complicated. Nixtamalization of corn, necessary to prevent vitamin deficiencies, involves soaking the corn in a solution containing ground-up burnt seashells. The ancient Mexicans discovered this and lived off corn just fine for millennia. When the conquistadors took over, they ignored it and ate corn straight. For four hundred years, Europeans and Americans ate unnixtamalized corn. By official statistics, three million Americans came down with corn-related vitamin deficiencies during this time, and up to a hundred thousand died. It wasn’t until 1937 that Western scientists discovered which vitamins were involved and developed an industrial version of nixtamalization that made corn safe. Early 1900s Americans were very smart and had lots of advantages over ancient Mexicans. But the ancient Mexicans’ culture got this one right in a way it took Westerners centuries to match.

Our hands and limbs also evolved alongside our cultures. We improved dramatically in some areas: after eons of tool use, our hands outclass those of any other ape in terms of finesse. In other cases, we devolved systems that were no longer necessary; we are much weaker than any other ape. Henrich describes a circus act of the 1940s where the ringmaster would challenge strong men in the audience to wrestle a juvenile chimpanzee. The chimpanzee was tied up, dressed in a mask that prevented it from biting, and wearing soft gloves that prevented it from scratching. No human ever lasted more than five seconds. Our common ancestor with other apes grew weaker and weaker as we became more and more reliant on artificial weapons to give us an advantage.

Even our sweat glands evolved alongside culture. Humans are persistence hunters: they cannot run as fast as gazelles, but they can keep running for longer than gazelles (or almost anything else). Why did we evolve into that niche? The secret is our ability to carry water. Every hunter-gatherer culture has invented its own water-carrying techniques, usually some kind of waterskin. This allowed humans to switch to perspiration-based cooling systems, which allowed them to run as long as they want.

III.

But most of our differences from other apes are indeed in the brain. They’re just not where you’d expect.

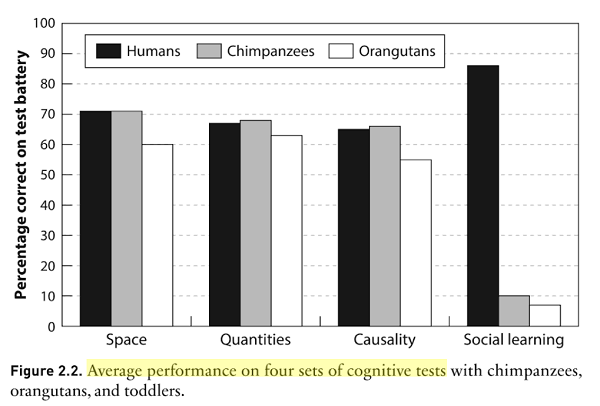

Tomasello et al tested human toddlers vs. apes on a series of traditional IQ type questions. The match-up was surprisingly fair; in areas like memory, logic, and spatial reasoning, the three species did about the same. But in ability to learn from another person, humans wiped the floor with the other two ape species:

Remember, Henrich thinks culture accumulates through random mutation. Humans don’t have control over how culture gets generated. They have more control over how much of it gets transmitted to the next generation. If 100% gets transmitted, then as more and more mutations accumulate, the culture becomes better and better. If less than 100% gets transmitted, then at some point new culture gained and old culture lost fall into equilibrium, and your society stabilizes at some higher or lower technological level. This means that transmitting culture to the next generation is maybe the core human skill. The human brain is optimized to make this work as well as possible.

Human children are obsessed with learning things. And they don’t learn things randomly. There seem to be “biases in cultural learning”, ie slots in an infant’s mind that they know need to be filled with knowledge, and which they preferentially seek out the knowledge necessary to fill.

One slot is for language. Human children naturally listen to speech (as early as in the womb). They naturally prune the phonemes they are able to produce and distinguish to the ones in the local language. And they naturally figure out how to speak and understand what people are saying, even though learning a language is hard even for smart adults.

Another slot is for animals. In a world where megafauna has been relegated to zoos, we still teach children their ABCs with “L is for lion” and “B is for bear”, and children still read picture books about Mr. Frog and Mrs. Snake holding tea parties. Henrich suggests that just as the young brain is hard-coded to want to learn language, so it is hard-coded to want to learn the local animal life (maybe little boys’ vehicle obsession is an outgrowth of this – buses and trains are the closest thing to local megafauna that most of them will encounter!)

Another slot is for plants:

To see this system in operation, let’s consider how infants respond to unfamiliar plants. Plants are loaded with prickly thorns, noxious oils, stinging nettles and dangerous toxins, all genetically evolved to prevent animals like us from messing with them. Given our species wide geographic range and diverse use of plants as foods, medicines and construction materials, we ought to be primed to both learn about plants and avoid their dangers. To explore this idea in the lab, the psychologists Annie Wertz and Karen Wynn first gave infants, who ranged in age from eight to eighteen months, an opportunity to touch novel plants (basil and parsley) and artifacts, including both novel objects and common ones, like wooden spoons and small lamps.

The results were striking. Regardless of age, many infants flatly refused to touch the plants at all. When they did touch them, they waited substantially longer than they did with the artifacts. By contrast, even with the novel objects, infants showed none of this reluctance. This suggests that well before one year of age infants can readily distinguish plants from other things, and are primed for caution with plants. But, how do they get past this conservative predisposition?

The answer is that infants keenly watch what other people do with plants, and are only inclined to touch or eat the plants that other people have touched or eaten. In fact, once they get the ‘go ahead’ via cultural learning, they are suddenly interested in eating plants. To explore this, Annie and Karen exposed infants to models who both picked fruit from plants and also picked fruit-like things from an artifact of similar size and shape to the plant. The models put both the fruit and the fruit-like things in their mouths. Next, the infants were given a choice to go for the fruit (picked from the plant) or the fruit-like things picked from the object. Over 75% of the time the infants went for the fruit, not the fruit-like things, since they’d gotten the ‘go ahead’ via cultural learning.

As a check, the infants were also exposed to models putting the fruit or fruit-like things behind their ears(not in their mouths). In this case, the infants went for the fruit or fruit-like things in equal measure. It seems that plants are most interesting if you can eat them, but only if you have some cultural learning cues that they aren’t toxic.

After Annie first told me about her work while I was visiting Yale in 2013, I went home to test it on my 6-month-old son, Josh. Josh seemed very likely to overturn Annie’s hard empirical work, since he immediately grasped anything you gave him and put it rapidly in his mouth. Comfortable in his mom’s arms, I first offered Josh a novel plastic cube. He delighted in grabbing it and shoving it directly into his mouth, without any hesitation. Then, I offered him a sprig of arugula. He quickly grabbed it, but then paused, looked with curious uncertainty at it, and then slowly let it fall from his hand while turning to hug his mom.

It’s worth pointing out how rich the psychology is here. Not only do infants have to recognize that plants are different from objects of similar size, shape and color, but they need to create categories for types of plants, like basil and parsley, and distinguish ‘eating’ from just ‘touching’. It does them little good to code their observation of someone eating basil as ‘plants are good to eat’ since that might cause them to eat poisonous plants as well as basil. But, it also does them little good to narrowly code the observation as ‘that particular sprig of basil is good to eat’ since that particular sprig has just been eaten by the person they are watching. This another content bias in cultural learning.

This ties into the more general phenomenon of figuring out what’s edible. Most Westerners learn insects aren’t edible; some Asians learn that they are. This feels deeper than just someone telling you insects aren’t edible and you believing them. When I was in Thailand, my guide offered me a giant cricket, telling me it was delicious. I believed him when he said it was safe to eat, I even believed him when he said it tasted good to him, but my conditioning won out – I didn’t eat the cricket. There seems to be some process where a child’s brain learns what is and isn’t locally edible, then hard-codes it against future change.

(Or so they say; I’ve never been able to eat shrimp either.)

Another slot is for gender roles. By now we’ve all heard the stories of progressives who try to raise their children without any exposure to gender. Their failure has sometimes been taken as evidence that gender is hard-coded. But it can’t be quite that simple: some modern gender roles, like girls = pink, are far from obvious or universal. Instead, it looks like children have a hard-coded slot that gender roles go into, work hard to figure out what the local gender roles are (even if their parents are trying to confuse them), then latch onto them and don’t let go.

In the Cultural Intelligence Hypothesis, humans live in obligate symbiosis with a culture. A brain without an associated culture is incomplete and not very useful. So the infant brain is adapted to seek out the important aspects of its local culture almost from birth and fill them into the appropriate slots in order to become whole.

IV.

The next part of the book discusses post-childhood learning. This plays an important role in hunter-gatherer tribes:

While hunters reach their peak strength and speed in their twenties, individual hunting success does not peak until around age 30, because success depends more on know-how and refined skills than on physical prowess.

This part of the book made most sense in the context of examples like the Inuit seal-hunting strategy which drove home just how complicated and difficult hunting-gathering was. Think less “Boy Scouts” and more “PhD”; a primitive tribesperson’s life requires mastery of various complicated technologies and skills. And the difference between “mediocre hunter” and “great hunter” can be the difference between high status (and good mating opportunities) and low status, or even between life and death. Hunter-gatherers really want to learn the essentials of their hunter-gatherer lifestyle, and learning it is really hard. Their heuristics are:

Learn from people who are good at things and/or widely-respected. If you haven’t already read about the difference between dominance and prestige hierarchies, check out Kevin Simler’s blog post on the topic. People will fear and obey authority figures like kings and chieftains, but they give a different kind of respect (“prestige”) to people who seem good at things. And since it’s hard to figure out who’s good at things (can a non-musician who wants to start learning music tell the difference between a merely good performer and one of the world’s best?) most people use the heuristic of respecting the people who other people respect. Once you identify someone as respect-worthy, you strongly consider copying them in, well, everything:

To understand prestige as a social phenomenon, it’s crucial to realize that it’s often difficult to figure out what precisely makes someone successful. In modern societies, the success of a star NBA basketball player might arise from his:

(1) intensive practice in the offseason

(2) sneaker preference

(3) sleep schedule

(4) pre-game prayer

(5) special vitamins

(6) taste for carrotsAny or all of these might increase his success. A naïve learner can’t tell all the causal links between an individual’s practices and his success. As a consequence, learners often copy their chosen models broadly across many domains. Of course, learners may place more weight on domains that for one reason or other seem more causally relevant to the model’s success. This copying often includes the model’s personal habits or styles as well as their goals and motivations, since these may be linked to their success. This “if in doubt, copy it” heuristic is one of the reasons why success in one domain converts to influence across a broad range of domains.

The immense range of celebrity endorsements in modern societies shows the power of prestige. For example, NBA star Lebron James, who went directly from High School to the pros, gets paid millions to endorse State Farm Insurance. Though a stunning basketball talent, it’s unclear why Mr. James is qualified to recommend insurance companies. Similarly, Michael Jordan famously wore Hanes underwear and apparently Tiger Woods drove Buicks. Beyonce’ drinks Pepsi (at least in commercials). What’s the connection between musical talent and sugary cola beverages?

Finally, while new medical findings and public educational campaigns only gradually influence women’s approach to preventive medicine, Angelina Jolie’s single OP-ED in the New York Times, describing her decision to get a preventive double mastectomy after learning she had the ‘faulty’ BRCA1 gene, flooded clinics from the U.K. to New Zealand with women seeking genetic screenings for breast cancer. Thus, an unwanted evolutionary side effect, prestige turns out to be worth millions, and represents a powerful and underutilized public health tool.

Of course, this creates the risk of prestige cascades, where some irrelevant factor (Henrich mentions being a reality show star) catapults someone to fame, everyone talks about them, and you end up with Muggeridge’s definition of a celebrity: someone famous for being famous.

Some of this makes more sense if you go back to the evolutionary roots, and imagine watching the best hunter in your tribe to see what his secret is, or being nice to him in the hopes that he’ll take you under his wing and teach you stuff.

(but if all this is true, shouldn’t public awareness campaigns that hire celebrity spokespeople be wild successes? Don’t they just as often fail, regardless of how famous a basketball player they can convince to lecture schoolchildren about how Winners Don’t Do Drugs?)

Learn from people who are like you. If you are a man, it is probably a bad idea to learn fashion by observing women. If you are a servant, it is probably a bad idea to learn the rules of etiquette by observing how the king behaves. People are naturally inclined to learn from people more similar to themselves.

Henrich ties this in to various studies showing that black students learn best from a black teacher, female students from a female teacher, et cetera.

Learn from old people. Humans are almost unique in having menopause; most animals keep reproducing until they die in late middle-age. Why does evolution want humans to stick around without reproducing?

Because old people have already learned the local culture and can teach it to others. Henrich asks us to throw out any personal experience we have of elders; we live in a rapidly-changing world where an old person is probably “behind the times”. But for most of history, change happened glacially slowly, and old people would have spent their entire lives accumulating relevant knowledge. Imagine a Silicon Valley programmer stumped by a particularly tough bug in his code calling up his grandfather, who has seventy years’ experience in the relevant programming language.

Sometimes important events only happen once in a generation. Henrich tells the story of an Australian aboriginal tribe facing a massive drought. Nobody knew what to do except Paralji, the tribe’s oldest man, who had lived through the last massive drought and remembered where his own elders had told him to find the last-resort waterholes.

This same dynamic seems to play out even in other species:

In 1993, a severe drought hit Tanzania, resulting in the death of 20% of the African elephant calves in a population of about 200. This population contained 21 different families, each of which was led by a single matriarch. The 21 elephant families were divided into 3 clans, and each clan shared the same territory during the wet season (so, they knew each other). Researchers studying these elephants have analyzed the survival of the calves and found that families led by older matriarchs suffered fewer deaths of their calves during this drought.

Moreover, two of the three elephant clans unexpectedly left the park during the drought, presumably in search of water, and both had much higher survival rates than the one clan that stayed behind. It happens that these severe droughts only hit about once every four to five decades, and the last one hit about 1960. After that, sadly, elephant poaching in the 1970’s killed off many of the elephants who would have been old enough in 1993 to recall the 1960 drought. However, it turns out that exactly one member of each of the two clans who left the park, and survived more effectively, were old enough to recall life in 1960. This suggests, that like Paralji in the Australian desert, they may have remembered what to do during a severe drought, and led their groups to the last water refuges. In the clan who stayed behind, the oldest member was born in 1960, and so was too young to have recalled the last major drought.

More generally, aging elephant matriarchs have a big impact on their families, as those led by older matriarchs do better at identifying and avoiding predators (lions and humans), avoiding internal conflicts and identifying the calls of their fellow elephants. For example, in one set of field experiments, researchers played lion roars from both male and female lions, and from either a single lion or a trio of lions. For elephants, male lions are much more dangerous than females, and of course, three lions are always worse than only one lion. All the elephants generally responded with more defensive preparations when they heard three lions vs. one. However, only the older matriarchs keenly recognized the increased dangers of male lions over female lions, and responded to the increased threat with elephant defensive maneuvers.

V.

I was inspired to read Secret by Scholar’s Stage’s review. I hate to be unoriginal, but after reading the whole book, I agree that the three sections Tanner cites – on divination, on manioc, and on shark taboos – are by far the best and most fascinating.

On divination:

When hunting caribou, Naskapi foragers in Labrador, Canada, had to decide where to go. Common sense might lead one to go where one had success before or to where friends or neighbors recently spotted caribou.

However, this situation is like [the Matching Pennies game]. The caribou are mismatchers and the hunters are matchers. That is, hunters want to match the locations of caribou while caribou want to mismatch the hunters, to avoid being shot and eaten. If a hunter shows any bias to return to previous spots, where he or others have seen caribou, then the caribou can benefit (survive better) by avoiding those locations (where they have previously seen humans). Thus, the best hunting strategy requires randomizing.

Can cultural evolution compensate for our cognitive inadequacies? Traditionally, Naskapi hunters decided where to go to hunt using divination and believed that the shoulder bones of caribou could point the way to success. To start the ritual, the shoulder blade was heated over hot coals in a way that caused patterns of cracks and burnt spots to form. This patterning was then read as a kind of map, which was held in a pre-specified orientation. The cracking patterns were (probably) essentially random from the point of view of hunting locations, since the outcomes depended on myriad details about the bone, fire, ambient temperature, and heating process. Thus, these divination rituals may have provided a crude randomizing device that helped hunters avoid their own decision-making biases.

This is not some obscure, isolated practice, and other cases of divination provide more evidence. In Indonesia, the Kantus of Kalimantan use bird augury to select locations for their agricultural plots. Geographer Michael Dove argues that two factors will cause farmers to make plot placements that are too risky. First, Kantu ecological models contain the Gambler’s Fallacy, and lead them to expect floods to be less likely to occur in a specific location after a big flood in that location (which is not true). Second…Kantus pay attention to others’ success and copy the choices of successful households, meaning that if one of their neighbors has a good yield in an area one year, many other people will want to plant there in the next year. To reduce the risks posed by these cognitive and decision-making biases, Kantu rely on a system of bird augury that effectively randomizes their choices for locating garden plots, which helps them avoid catastrophic crop failures. Divination results depend not only on seeing a particular bird species in a particular location, but also on what type of call the bird makes (one type of call may be favorable, and another unfavorable).

The patterning of bird augury supports the view that this is a cultural adaptation. The system seems to have evolved and spread throughout this region since the 17th century when rice cultivation was introduced. This makes sense, since it is rice cultivation that is most positively influenced by randomizing garden locations. It’s possible that, with the introduction of rice, a few farmers began to use bird sightings as an indication of favorable garden sites. On-average, over a lifetime, these farmers would do better – be more successful – than farmers who relied on the Gambler’s Fallacy or on copying others’ immediate behavior. Whatever the process, within 400 years, the bird augury system spread throughout the agricultural populations of this Borneo region. Yet, it remains conspicuously missing or underdeveloped among local foraging groups and recent adopters of rice agriculture, as well as among populations in northern Borneo who rely on irrigation. So, bird augury has been systematically spreading in those regions where it’s most adaptive.

Scott Aaronson has written about how easy it is to predict people trying to “be random”:

In a class I taught at Berkeley, I did an experiment where I wrote a simple little program that would let people type either “f” or “d” and would predict which key they were going to push next. It’s actually very easy to write a program that will make the right prediction about 70% of the time. Most people don’t really know how to type randomly. They’ll have too many alternations and so on. There will be all sorts of patterns, so you just have to build some sort of probabilistic model. Even a very crude one will do well. I couldn’t even beat my own program, knowing exactly how it worked. I challenged people to try this and the program was getting between 70% and 80% prediction rates. Then, we found one student that the program predicted exactly 50% of the time. We asked him what his secret was and he responded that he “just used his free will.”

But being genuinely random is important in pursuing mixed game theoretic strategies. Henrich’s view is that divination solved this problem effectively.

I’m reminded of the Romans using augury to decide when and where to attack. This always struck me as crazy; generals are going to risk the lives of thousands of soldiers because they saw a weird bird earlier that morning? But war is a classic example of when a random strategy can be useful. If you’re deciding whether to attack the enemy’s right vs. left flank, it’s important that the enemy can’t predict your decision and send his best defenders there. If you’re generally predictable – and Scott Aaronson says you are – then outsourcing your decision to weird birds might be the best way to go.

And then there’s manioc. This is a tuber native to the Americas. It contains cyanide, and if you eat too much of it, you get cyanide poisoning. From Henrich:

In the Americas, where manioc was first domesticated, societies who have relied on bitter varieties for thousands of years show no evidence of chronic cyanide poisoning. In the Colombian Amazon, for example, indigenous Tukanoans use a multistep, multiday processing technique that involves scraping, grating, and finally washing the roots in order to separate the fiber, starch, and liquid. Once separated, the liquid is boiled into a beverage, but the fiber and starch must then sit for two more days, when they can then be baked and eaten. Figure 7.1 shows the percentage of cyanogenic content in the liquid, fiber, and starch remaining through each major step in this processing.

Such processing techniques are crucial for living in many parts of Amazonia, where other crops are difficult to cultivate and often unproductive. However, despite their utility, one person would have a difficult time figuring out the detoxification technique. Consider the situation from the point of view of the children and adolescents who are learning the techniques. They would have rarely, if ever, seen anyone get cyanide poisoning, because the techniques work. And even if the processing was ineffective, such that cases of goiter (swollen necks) or neurological problems were common, it would still be hard to recognize the link between these chronic health issues and eating manioc. Most people would have eaten manioc for years with no apparent effects. Low cyanogenic varieties are typically boiled, but boiling alone is insufficient to prevent the chronic conditions for bitter varieties. Boiling does, however, remove or reduce the bitter taste and prevent the acute symptoms (e.g., diarrhea, stomach troubles, and vomiting).

So, if one did the common-sense thing and just boiled the high-cyanogenic manioc, everything would seem fine. Since the multistep task of processing manioc is long, arduous, and boring, sticking with it is certainly non-intuitive. Tukanoan women spend about a quarter of their day detoxifying manioc, so this is a costly technique in the short term. Now consider what might result if a self-reliant Tukanoan mother decided to drop any seemingly unnecessary steps from the processing of her bitter manioc. She might critically examine the procedure handed down to her from earlier generations and conclude that the goal of the procedure is to remove the bitter taste. She might then experiment with alternative procedures by dropping some of the more labor-intensive or time-consuming steps. She’d find that with a shorter and much less labor-intensive process, she could remove the bitter taste. Adopting this easier protocol, she would have more time for other activities, like caring for her children. Of course, years or decades later her family would begin to develop the symptoms of chronic cyanide poisoning.

Thus, the unwillingness of this mother to take on faith the practices handed down to her from earlier generations would result in sickness and early death for members of her family. Individual learning does not pay here, and intuitions are misleading. The problem is that the steps in this procedure are causally opaque—an individual cannot readily infer their functions, interrelationships, or importance. The causal opacity of many cultural adaptations had a big impact on our psychology.

Wait. Maybe I’m wrong about manioc processing. Perhaps it’s actually rather easy to individually figure out the detoxification steps for manioc? Fortunately, history has provided a test case. At the beginning of the seventeenth century, the Portuguese transported manioc from South America to West Africa for the first time. They did not, however, transport the age-old indigenous processing protocols or the underlying commitment to using those techniques. Because it is easy to plant and provides high yields in infertile or drought-prone areas, manioc spread rapidly across Africa and became a staple food for many populations. The processing techniques, however, were not readily or consistently regenerated. Even after hundreds of years, chronic cyanide poisoning remains a serious health problem in Africa. Detailed studies of local preparation techniques show that high levels of cyanide often remain and that many individuals carry low levels of cyanide in their blood or urine, which haven’t yet manifested in symptoms. In some places, there’s no processing at all, or sometimes the processing actually increases the cyanogenic content. On the positive side, some African groups have in fact culturally evolved effective processing techniques, but these techniques are spreading only slowly.

Rationalists always wonder: how come people aren’t more rational? How come you can prove a thousand times, using Facts and Logic, that something is stupid, and yet people will still keep doing it?

Henrich hints at an answer: for basically all of history, using reason would get you killed.

A reasonable person would have figured out there was no way for oracle-bones to accurately predict the future. They would have abandoned divination, failed at hunting, and maybe died of starvation.

A reasonable person would have asked why everyone was wasting so much time preparing manioc. When told “Because that’s how we’ve always done it”, they would have been unsatisfied with that answer. They would have done some experiments, and found that a simpler process of boiling it worked just as well. They would have saved lots of time, maybe converted all their friends to the new and easier method. Twenty years later, they would have gotten sick and died, in a way so causally distant from their decision to change manioc processing methods that nobody would ever have been able to link the two together.

Henrich discusses pregnancy taboos in Fiji; pregnant women are banned from eating sharks. Sure enough, these sharks contain chemicals that can cause birth defects. The women didn’t really know why they weren’t eating the sharks, but when anthropologists demanded a reason, they eventually decided it was because their babies would be born with shark skin rather than human skin. As explanations go, this leaves a lot to be desired. How come you can still eat other fish? Aren’t you worried your kids will have scales? Doesn’t the slightest familiarity with biology prove this mechanism is garbage? But if some smart independent-minded iconoclastic Fijian girl figured any of this out, she would break the taboo and her child would have birth defects.

In giving humans reason at all, evolution took a huge risk. Surely it must have wished there was some other way, some path that made us big-brained enough to understand tradition, but not big-brained enough to question it. Maybe it searched for a mind design like that and couldn’t find one. So it was left with this ticking time-bomb, this ape that was constantly going to be able to convince itself of hare-brained and probably-fatal ideas.

Here, too, culture came to the rescue. One of the most important parts of any culture – more important than the techniques for hunting seals, more important than the techniques for processing tubers – is techniques for making sure nobody ever questions tradition. Like the belief that anyone who doesn’t conform is probably a witch who should be cast out lest they bring destruction upon everybody. Or the belief in a God who has commanded certain specific weird dietary restrictions, and will torture you forever if you disagree. Or the fairy tales where the prince asks a wizard for help, and the wizard says “You may have everything you wish forever, but you must never nod your head at a badger”, and then one day the prince nods his head at a badger, and his whole empire collapses into dust, and the moral of the story is that you should always obey weird advice you don’t understand.

There’s a monster at the end of this book. Humans evolved to transmit culture with high fidelity. And one of the biggest threats to transmitting culture with high fidelity was Reason. Our ancestors lived in Epistemic Hell, where they had to constantly rely on causally opaque processes with justifications that couldn’t possibly be true, and if they ever questioned them then they might die. Historically, Reason has been the villain of the human narrative, a corrosive force that tempts people away from adaptive behavior towards choices that “sounded good at the time”.

Why are people so bad at reasoning? For the same reason they’re so bad at letting poisonous spiders walk all over their face without freaking out. Both “skills” are really bad ideas, most of the people who tried them died in the process, so evolution removed those genes from the population, and successful cultures stigmatized them enough to give people an internalized fear of even trying.

VI.

This book belongs alongside Seeing Like A State and the works of G.K. Chesterton as attempts to justify tradition, and to argue for organically-evolved institutions over top-down planning. What unique contribution does it make to this canon?

First, a lot more specifically anthropological / paleoanthropological rigor than the other two.

Second, a much crisper focus: Chesterton had only the fuzziest idea that he was writing about cultural evolution, and Scott was only a little clearer. I think Henrich is the only one of the three to use the term, and once you hear it, it’s obviously the right framing.

Third, a sense of how traditions contain the meta-tradition of defending themselves against Reason, and a sense for why this is necessary.

And fourth, maybe we’re not at the point where we really want unique contributions yet. Maybe we’re still at the point where we have to have this hammered in by more and more examples. The temptation is always to say “Ah, yes, a few simple things like taboos against eating poisonous plants may be relics of cultural evolution, but obviously by now we’re at the point where we know which traditions are important vs. random looniness, and we can rationally stick to the important ones while throwing out the garbage.” And then somebody points out to you that actually divination using oracle bones was one of the important traditions, and if you thought you knew better than that and tried to throw it out, your civilization would falter.

Maybe we just need to keep reading more similarly-themed books until this point really sinks in, and we get properly worried.

Just discovered this blog. Really fascinating; quite an amazing island of rationalism/moderation in an ocean of ideology/extremism.

For all this talk of rationalism vs. tradition, it seems to me it should be important to distinguish between the “Facts” and “Logic” aspects of rationalism. Whereas Logic is a method of coming to the wrong conclusion with confidence, Fact-based empiricism is a method of coming to a correct conclusion that often seems uninuitive and nonsensical.

I would argue that tradition as explored in this book review is “evolutionary empiricism” while science is “systematic/accelerated empiricism”. And just as using the Logic subset of rationalism could get you killed in ancient times (or possibly produce inoffensive superstitions), in contemporary times that same Logic has produced pseudoscience and various absurd (and even dangerous) ideologies.

I think bundling Logic and Fact together as Rationalism is the reason many people reject it; humans suck at Logic, it has a bad track record, and people instinctively know that.

This whole discussion seems to be centered around people with high-level cognitive skills and who expect to use them routinely, effectively, “intellectuals”. I think that’s an error, as those people are a fairly small faction in society (especially before very recent times) and aren’t necessarily politically dominant.

But it is the “Enlightenment” philosophy, the idea that everything can be understood and improved by rational thought. These articles applied a scientific approach to understanding the mechanical and production processes, and offered new ways to improve machines to make them more efficient.

An acute example of this is the gay marriage controversy. The advocates have largely been high-IQ people who live in very Enlightenment circumstances, but in most cases, the bulk of the voters have been opposed to gay marriage, for illegible, traditionalist reasons.

This shows that it’s possible to have traditionalism within a democratic system, as long as a large faction of society are not intellectuals, and can’t be convinced by de-novo intellectual arguments.

A case that can be used to dig into this dynamic is the history of monetary policy. For a long time, it was operated in a traditionalist way, though of course subject to the usual buffeting by politics. (E.g., Bryan’s “Cross of Gold” speech, which was a plea to inflate money, to counter the pervasive deflation of the late 1800s and the stress it put on farmers with mortgages.) John Maynard Keynes produced a monetary theory which predicted that unemployment could be lowered on an ongoing basis by tolerating continuous inflation. This was ignored until decades later when John Kennedy appointed a Council of Economic Advisers and appointed Keynsians to the Fed. Unfortunately, Keynes’s theory isn’t correct, and to produce a permanent reduction in unemployment, you need to have the continuously rising inflation. But it took the Fed twenty years to discern this in practice.

So current monetary policy is a body of traditional observations of what gives desirable and undesirable results. I suspect that monetary decisions are supported by a body of analysis and theory which are improved by active research, but the big framework seems to be fundamentally tradition.

A broader and deeper arena for these sorts of interactions is the “constitution” of a democracy. Constitutions are traditionalist instruments, and it’s a sign of bad government when a country changes its constitution frequently. But constitutions aren’t fixed, and usually their “interpretation” is given to a formal or informal body of high-IQ individuals who are nonetheless tasked with the preservation and implementation of tradition. In the US, this has been explicitly assumed by the Supreme Court (It can be argued that this task was not envisioned when the US Constitution was written!); in a lot of European countries the legislature has a lot of power to revise the constitution but is highly circumscribed by tradition.

There’s also a connection with Buckley’s quip that he would rather be governed by the first 2,000 names in the Boston telephone book than the faculty of Harvard. The implication is that the Harvard faculty are just the sort of intellectuals who tend to think that they’ve figured out a new and better way to run things … and often their proposal works worse in reality.

No mention is made of the fact that this account of human success supports Robin Hanson’s argument in the FOOM debate. The perhaps most common defense for the FOOM claim is that human brains are so vastly better and more capable than chimpanzee brains. Yet Hanson’s counter-point is, essentially, the point made by Henrich: we are mostly unique in being good at transmitting culture, and that allowed innovation to grow. Human success, including the subset of human success that is growth, broadly construed, has been the product of superior culture that accumulated rather than pure brain gain per se.

After all, the brain of modern humans is roughly the same as the brains of hunter-gatherer humans, and yet virtually all the things we claim are uniquely human and which people fear from advanced AI, came from post hunter-gatherer humans. This is worth reflecting on, IMO.

This post has illuminated some thoughts on how a hare runs in a random pattern to avoid being caught by their predator. The technique works best when it’s truly random and not conscious to the hare. If the hare were conscious about the pattern and it’s next move, it’s body language might be too revealing to the predator. Over time the hares with more self awareness would likely die out and most modern hares likely come from descendants of less self knowledge.

Similarly, humans might be descended from ancestors who were skilled at hiding their motives, not only from outsiders but from themselves too.

I suppose the point I am trying to make here, is evolution works in mysterious ways. Whether it be subconscious behaviors that only work because the host unaware of the behavior, or traditions that are better following because of their potential adaptive utility.

Another book that pairs well with _The Secret of Our Success_ is Thomas Sowell’s _Knowledge and Decisions_.

The thing is, cultural evolution’s reach is also increased via reason. Those processing steps were surely the result of a hill-climbing process (probably with high-cyanide manioc) that involved the women adapting to manioc by thinking about stuff that had worked in the past, or stuff they knew how to do, or stuff that seemed to take the bitter taste out or make people less sick. Good bows, arrows, spears, houses, clothing, etc., weren’t made from random improvements the way evolution works in genes. Instead, they must have been individual innovations that then stuck or didn’t stick for some combination of working well and being usable/comprehensible by other people.

Consider the Openness to Experience personality trait. You can think of this as a kind of slider bar that’s set by some combination of your genes, your early childhood environment, and your culture. Slide it too far to the left and you never innovate–you’re stuck in a rut, and when new problems or challenges arise, you can’t figure out what to do. Slide it too far to the right, and you’re constantly discarding all the accumulated wisdom of your civilization and getting cyanide poisoning or making arrows that don’t fly true.

My guess is that food taboos are some of the strongest ones we have. And also that overcoming those taboos has happened in our history mostly at times when our ancestors were otherwise starving to death.

A pretty obvious strategy for all kinds of civilizational inertia vs innovation is to look around at how things are working out for you. If you’re constantly getting your ass kicked in tribal conflicts, or you’re hungry and sick all the time, you should become more willing to be innovative. And also, you probably want a fair distribution of innovative/conservative people in your tribe, so there are always a few people trying out new stuff and often getting burned, but occasionally getting a big benefit.

Aaronson’s ancedote doesn’t check out to me. I remember a psychology study that found that, if you tell some humans to generate random sequences and then give them timely and accurate feedback of how random they’re being, they learn to do it in a few minutes.

Re: humans evolving to be physically puny.

For most of our evolution, our tools have aided us in physical tasks, allowing us to survive with reduced physical ability. Naturally, evolution responded by reducing our physical abilities. Recently our tools have begun to substitute for mental tasks. The likely consequences are horrifying to contemplate.

That seems to me a misrepresentation. Tools made it so that being burly was not all that needed, but selection doesn’t pick (and don’t anyf***** one @ me at how selection and choosing arent the right words for evolution) weakness. Instead it picked two traits that were hard to square with burly bulk: Stamina and Precision.

Its not impossible that AI would result in selecting for dullards, but it might also select against dullards as their limited mental ability is the first set of abilities to become useless.

I don’t think this is right. Look at some of the examples given: small mouths, reduced teeth (especially canines), reduced jaw muscles. Those don’t help with stamina — they’re metabolically expensive, and so they naturally were done away with once humans invented tools to cut and grind food, fire to cook it, and weapons to slice and bash people with.

We used to have pretty thick skulls: evolved defense against being bashed on the head. Then at some point our skulls started getting lighter. Why? Missile weapons. We also got a lot more gracile around this time.

(I’m somewhat skeptical of the endurance running hypothesis of human evolution anyway, but that’s another matter).

For people interested in the story of how we (very slowly) came to realize what caused the physical and mental problems associated with a high-corn, low-meat/milk/vegetable diet, I recommend the book “The Butterfly Caste: A Social History of Pellagra in the South” by Elizabeth Etheridge.

Thank you so much for this peak at an important book!

Amazing. I feel like I’m one of today’s lucky 10000.

Perhaps the real point is not “20 years later, everyone dies of cyanide poisoning” but “200 years later, absolutely everyone dies from the effects of climate change”?

As others have said, the initial example is unfortunate. Seal hunting is a skill. Skills take time to acquire. If you’re stranded in a situation where you need to hunt seals to survive, it’s too late to learn.

The idea of hunting seals is not difficult, as Clutzy said. It’s the implementation which is hard.

Clearly in this instance the skill has been refined over many generations, and in that sense is cultural. But there’s no “mysterious process” here. It’s just successive generations of Inuit using their intellects to make marginal improvements to the technique.

Maybe this gets the review off to a bad start, but it seems to me that what is being described as “cultural evolution” could equally amount to saying that humans (a) have the intelligence to develop tools and techniques for a variety of environments and (b) are able to pass this knowledge on to other humans, including their children. And yes, the accumulated body of knowledge passed down within a given area is “culture”, and a human from a different culture will likely lack knowledge essential to that area, but there doesn’t seem anything very remarkable about this.

The account of human evolution in II seems dodgy. AFAIK, the masticatory apparatus and digestive systems of primates vary widely depending on their diet. There is trade off between the digestive system and brain, because both are energy intensive. There are lots of explanations for why humans evolved as persistence hunters (assuming they did, which not everyone agrees), but I’m pretty certain it has something to do with bipedalism. At any rate, the observation that “every hunter-gatherer culture” has water-carrying techniques is not to the point, since no contemporary (or historically recorded) hunter-gatherer culture relies exclusively on persistance hunting techniques, and all such cultures possess many technologies unknown to our earliest ancestors.

I’m always skeptical of rational explanations of taboos. Fijians have lots of taboos, including lots related to pregnancy. There are bound to be some which are actually reasonable precautions (although I’m not aware that shark-related birth defects are a problem anywhere in the world), but I doubt that a systematic analysis of taboos as a whole would show them to be justified. One sees a similar thing with with Judaic dietary laws: one can point to health-based reasons for this or that law, but as a systematic explanation of the laws as a whole, that works much less well than the purity-based explanation which is also stated in the text.

Fascinating! Presumably in the divination case with the caribou, there’s a chance that this is a sort of coordination. In that there may be some generally better hunting spots but if people go to those the caribou don’t etc. But the implication might be that actually a person not using divination is not a failure but a defector: he chooses the prime spots but because others don’t this isn’t a big enough pattern to put off the caribou.

Separately: the detoxification thing is explored in Terry Pratchett’s ‘Island’, kinda: you have to spit into then sing over something while you make it, which an outsider dismisses, but actually the spit is important because the enzymes respond to break down poison and the song gives the requisite amount of time for it to work.

More generally, I guess the issue is that tradition has to work for some good reason but this doesn’t mean it can’t be hijacked: if you can embed ‘and then bring the best food to the medicine man’ into your detoxification ritual then you’re exploiting the (legitimate) tradition adaptation.

If I may wade into total speculation mode with limited information…

I assume that the randomness isn’t real randomness. Ie the ‘map’ isn’t treated as a literal map where you get the result and then go searching for a place that it fits. Instead you are to look at the map and be reminded of one of several hunting grounds that you know about and select that one. This would prevent over hunting of individual grounds but prevent the silliness of walking randomly around looking for prey.

I swear that throughout the reading of this sequence I keep having a mental picture of Scott as the Fiddler on the roof, not that surprising I suppose, after all, most of us are shtetl optimized.

Here is the first monologue I think it fits well:

A fiddler on the roof…

TEVYE: “Sounds crazy, no? But here, in our little village of Anatevka, you might say every one of us is a fiddler on the roof. Trying to scratch out a pleasant, simple tune without breaking his neck. It isn’t easy. You may ask, why do we stay up there if it’s so dangerous? Well, we stay because Anatevka is our home.

And how do we keep our balance? That I can tell you in one word!

Tradition!(Song plays)

TEVYE: Because of our traditions, we’ve kept our balance for many, many years. Here in Anatevka, we have traditions for everything. How to sleep. How to eat. How to work. How to wear clothes. For instance, we always keep our heads covered, and always wear a little prayer shawl. This shows our constant devotion to God. You may ask, how did this tradition get started? I’ll tell you. I don’t know. But it’s a tradition. And because of our traditions, every one of us knows who he is and what God expects him to do”.

The explanation of divination as a randomization strategy reminds me somehow of that proposal by Peter Leeson that trial by ordeal really did work to separate the guilty from the innocent: if everyone believes that trial by ordeal works, then only an innocent person would choose it over alternatives, so the administrator could rig the trial to ensure that the accused would pass, and generally have the right result.

First you see a post which explains how a convincing theory outside one’s area of expertise can be accepted by a rational person.

Then you see a post which pushes a convincing theory. To most, at least, judging by the positive tone of the comments.

And no adds the two? Amazing.

I guess I got lucky because based on my personal experience many arguments in the book being reviewed ring false.

Have you read any of Nassim Taleb’s books, Scott? He’s definitely of this same “cultural evolutionist” mold, skeptical of rationalist, as opposed to time-tested, solutions to problems. I would recommend Antifragile as the most complete statement of his ideas. I would love to read a review of it by you.

https://slatestarcodex.com/2018/09/19/book-review-the-black-swan/

Seems to me that the Enlightenment was a bit too optimistic about Reason. People say everything good in modern life is a direct descendant of the Enlightenment. Is it true?

For example, it is good to not have slavery. Now when the Spanish discovered the Americas the churchmen of Salamanca got together in the royal court to discuss whether the natives are even human. They deducted that they have a religion, therefore they are human, therefore they should have the same rights as all other subjects of the king, like to not be killed or enslaved. Well they got killed and enslaved anyway, but that was not the churchmen’s fault. And their reasoning, while clearly pre-Enlightenment seems good to me: having a religion implies abilities like abstract thinking and imagination. Human abilities. Humans make sense of the world somehow, with religion, with philosophy, with science, somehow.

Anyway, long story short, later on slavery was defended with religious ideas, but also Enlightenment ideas, attacked with Enlightenment ideas, but also religious ideas.

So it is not conclusive to me that we not having slavery is entirely because of the Enlightenment.

I’ve long felt that my affiliation with LessWrong was atypical in that a large proportion of the old school commentariat of LW reported fabulous “rationalist origin stories”, nearly all of which involved a rejection of some (quite recently evolved?) form of evangelical protestantism that their parents and church pushed on them. These experiences didn’t resonate with me at all. In the normal stories, accepting that literalist non-denominational protestantism (or sometimes a conservative judaism) might be “not literally true” had sad social repercussions, often leading to ostracism and major life adjustments.

When I tried to come up with some equivalent experience, I mostly came up empty. Three out of four of my grandparents were alcoholics. None attended church. Each had a uniquely crazy (and probably dysfunctional) worldview that was not shared by either of my parents (who rejected vast swathes of their own parental influence) and in turn my organizing life beliefs and lifestyle choices are again quite different from my parents. One of my favorite ways to troll my parents nowadays is to speak well of filial piety, ask their opinion on things in my life, and then take their advice “because filial piety is good”. Neither of them believed in filial piety, so me believing in it feels pleasantly transgressive 😛

When I searched my memories of my life from 12-25 seeking a rationalist origin story similar to someone else rejecting evangelical Christianity after having been raised in it, I found a strong memory from when I was roughly 14. What happened was that I looked around and accidentally sort of “accepted in my bones” that almost everyone was acting in a way that involved flinching from an enormous number of painful but obvious truths, the uttering of which in their presence would count as a sort of unforgivably mean insult. Clearly this was psychologically healthy on their part… but also I didn’t respect it. It wasn’t something that a sincere truth seeker would do.

Around that time, and based on emotions like these, I more or less decided to commit a very long and slow and abstractly silly kind of “suicide” via Cognitive Russian Roulette. I decided that when I ran into a possible truth that seemed horrible, like something utterly unhealthy to contemplate at length, or only believed by bad people, and ridiculously weird to talk about in public… but which was ALSO HOW THINGS ACTUALLY ARE, those ideas were the stuff I’d specialize in learning and thinking about.

Obviously it wouldn’t be smart to talk about this content in public, because what part of “unforgivably mean insult” would I have to miss to make that mistake? Also most people I observed didn’t have blind spots like this for other people, mostly they just had these blind spots for themselves. So… uh… yeah.

It seemed to me then that if it turned out to be the case that orienting toward the idea of Truth in this way was unhealthy… so be it. If putting an important, accurate, and logically consistent idea in my head caused me to suffer or to die early, or some such, then suffering and early death would be my lot. My motto here was “Truth, truth, truth… to the bitter end.” It was NOT an attempt to construct a shiny new world view and life pattern that would be obviously eventually be better than conservative Judaism. To use the language of LW, it it was simply an (aesthetic?) rejection of instrumental rationality on topics (especially about myself) where epistemic rationality would hurt more.

It took something like 8 years before I found methods to ameliorate some of the worse aspects of this strategy, and more than 20 years later arguably I’m still in the grips of residual aspects of it?

Anyway, it is for this reason that I rarely try to evangelize “rationality” to normal people. My approach to this stuff seems unlikely to be good or healthy on average for normal people. My relationship with “the truth” feels to me somewhat like that of a moth to a candle, and if I can warn others away from the same path, that might be for the best. Conscientiousness upgrades and Filial Piety seem a *lot* safer to promote!

Two final comments…

ONE: The generation of novel culture seems pretty easy to account for to me. It just comes from people making shit up that “seems plausible” when they haven’t got any better ideas. Turn on the reinforcement learning engine and do whatever it outputs. Iterate this process and something semi-adequate often arises pretty fast. Paul Graham’s essay “Hackers and Painters” points to this phenomenon I think. Essentially, in various domains sometimes people have no option but to play Cognitive Russian Roulette and when it works out they try to “repeat the same thing”, and when repetition works, other people notice. Google [compensatory mutation] for a roughly analogous biological version. Broken mutants who lose an essential trick don’t necessarily get an optimal genome after compensatory mutations, but often they can “make do” with second order adjustments which wouldn’t even be useful if the original error hadn’t already been introduced.

TWO: I’m a huge fan of this sequence so far! It feels deep and useful and non-hubristic, and not super preachy, in a way that sort of reminds me of your posts on Bravery Debates. Also the grounding in practical examples is nice. If I was going to challenge the premise, it would eventually involve seeking contrasting examples. Larry Page and Elon Musk might be good case studies here, because they *both* have an obsession with first principles thinking, and both (rightly or wrongly) attribute some of their success partly to this obsession.

I don’t know if reason biologically exists in humans, but rather disagreeableness. Logical thinking is maybe a scalar applied to that. Diametrical opposition seems to comprise 80% of our heuristics whenever we deliberate.

Or maybe reason exists, but like the babies and vegetables, it’s domain-specific. So, in societies with bartering or a proto-currency, reason quickly became an adaptive trait to ensure fair deals.

An old Rabinnical-Jewish adage goes “the world was created in a disagreement” – this is basically the Socratic method of epistemology.

A funny point about the random number generators: Rituals which require more effort are more likely to produce truly random results, because a ritual which required less effort would be more tempting to re-do if you didn’t like the result.

This reminds me of my father’s argument that cheap computers resulted in less reliable statistical results. If running one multiple regression takes hundreds of man hours and thousands of dollars, running a hundred of them and picking the one that, by chance, gives you the significant result you are looking for, isn’t a practical option.

This could explain why the replication crisis is a recent phenomenon?

It could just as easily be the opposite – more unsound results were being published in the past and we now have more resources to detect it.

Mild necro-posting, but I have a two part theory on this that I think is important – though everything is always complicated and there are always many factors for everything, of course.

1) Technology has made hard things easy, so not only is it easier to keep doing more analyses (the point above), but it’s lowered the barriers to entry so that less competent people can perform complex analyses that they don’t really understand. In the past, most of the powerful statistical tools required quite a bit of mathematical skill to do, which controls for both raw intelligence (I.e. dumb people can’t do them at all) and understanding of what it means (if you don’t understand how it work, you probably can’t do the math to get any result at all).

2) Science as a practice has been degrading over the past ~50 years, which appears to be an almost paradoxical result of nuclear physics, with the net result that many people practice scientism (doing things that are facially similar to science) rather than science itself. A partial explanation for this change can be seen in the mid-century science giants – today we think of Einstein as a physicist, while in the 1930’s (post relativity) he was seen as a mathematician (as were almost all of his contemporaries, and all of the famous ones). After WW2, leaders in industry started hiring physicists and scientists because they were proven miracle workers, which incentivized people to don the mantle of science as a way of gaining prestige.

These two combined have resulted in people who use apparently powerful tools, appearing like a scientist from the outside, and claiming to use science, which has gained such a high reputation from the actual miracles of the 20th century (nuclear power, Bosch-Haber process, rockets, etc).

Overly simple examples:

Many high school and college math courses teach “calculus,” not by teaching the actual functions or theory, but by teaching the “cheats” (for those who know, the simple ways of integration and differentiation of polynomials, rather than infinite series expansions). This trick works for many cases where calculus is useful to the average man, but do not teach how they actually work. Anecdotally, I’ve never met anyone who has actually used calculus outside of school except for those who understand how it works, though there’s an obvious self selection bias.

Climate science is a good example of #2, with commonly heard statements such as “scientific consensus,” when consensus means precisely nothing to science, and the almost complete disregard of testing predictions to see if they’re true.

Richard Feynman explained the scientific method best:

Step 1: guess a rule of nature (hypothesis)

Step 2: calculate the consequences of your guess (prediction)

Step 3: test to see if your predictions are true.

If they’re not then your guess was wrong, if they’re right then your guess is only “not disproven.” The only yardstick for science is it’s ability to predict the future.

You can find a very short version of his presentation here: https://youtu.be/5v8habYTfHU

This is a bizarre strawman: The person this argument disproves believes that a person can be transported essentially immediately to a completely unfamiliar environment and become completely, survivable familiar before he or she starves to death, despite being alone and unprepared after a lifetime of living socially with preparation.

Does anybody argue this? Not that I’ve ever heard. It’s like saying “Well, it’s obvious we can’t build computers; one guy can’t unexpectedly find himself on an island with all the raw materials for computers and invent a working internet by himself with no experience in computers or computing books in a single lifetime”. Nobody expects that’s how computers and the internet were invented. We expect they were the product of a lot of tiny innovations, from multiple innovators, accumulated into a big thing.

The strawman is weirder considering Scott then talks about the Inuit, an invasive species in the cold-weather areas they live, who can live there because of innovation and intelligence built up over time. The difference people are talking about is that.

When we compare the Inuit to a raccoon, we aren’t saying “well, one single Inuit guy was teleported to the frozen north, and then invented everything he needed to survive by himself, in a week! It would have taken the raccoon many generations!” The comparison is that the raccoon, assuming he did not develop intelligence or evolve to a brute-force hunter, would never be able to hunt seals, while we can, as well as any other animal.

Once you take away the strawman of “everybody besides me and this author thinks everything ever was invented in one day” there’s no point actually being made here.

The view stated for contradiction in the immediately preceding sentence (to which “this” appears to refer in the passage you quoted) was “we are smart enough to invent neat tools that help us survive and adapt to new environments”.

As you say, the example shows that we can do this. The inuit have precisely invented neat tools (antler hole assayers! harpoons! bows! polar bear spikes! soapstone lamps!) to allow them to survive and adapt to an environment pretty much as far as possible from the ancestral environment.

The European explorer does badly (although as stated elsewhere, many Europeans have in fact successfully explored the Arctic) only by comparison with other humans.

A useful counter to this post–and this book–would be Edgerton’s “Sick Societies”, which argues fairly persuasively against the claim that culture is inherently adaptive, by citing numerous cultural practices around the world that were glaringly, shockingly maladaptive for the societies that embraced them–in a few cases, in fact, to the point of actual self-extermination.

I don’t see how it’s a counter, really. Nobody bats an eye when species have shockingly maladaptive traits, and nobody would consider this a rebuke to biologic evolution writ large. Dead ends… happen. Self-extermination is one way of getting rid of them.

Guys, I think we found a PC. Has anyone followed up with him so we can determine which genre of game we’re in?

Glad to see I’m not the only one who had that reaction.

Ok, digging in more now that I’m off mobile. I’m always in favor of giving the tool-use theory of human intellectual development a good kicking, and while while Tomasello’s work in distinguishing what exactly makes human intelligence special* is incredibly laudable, I don’t buy Henrich’s theory that it was in service of cultural transmission. That’s an “in order to” story instead of a “because of” story, and evolution doesn’t work with those. Rewriting the explanation so that marginal increases in cultural transmission capability results in runaway fitness increases… doesn’t really seem convincing. Especially not in contrast to the Machiavellian Intelligence Hypothesis, which we can practically see recurring with a few other species in real time.

*Answer – it’s always less than you think. Dissolution of difference in kind to difference in degree is incredibly suggestive, but that’s another topic.