[Parts of this post have since been shown to be wrong, as explained in this post. I endorse this reanalysis as better than the current post.]

Psychologists are split on the existence of “birth order effects”, where oldest siblings will have different personality traits and outcomes than middle or youngest siblings. Although some studies detect effects, they tend to be weak and inconsistent.

Last year, I posted Birth Order Effects Exist And Are Very Strong, finding a robust 70-30 imbalance in favor of older siblings among SSC readers. I speculated that taking a pre-selected population and counting the firstborn-to-laterborn ratio was better at revealing these effects than taking an unselected population and trying to measure their personality traits. Since then, other independent researchers have confirmed similar effects in historical mathematicians and Nobel-winning physicists. Although birth order effects do not seem to consistently affect IQ, some studies suggest that they do affect something like “intellectual curiosity”, which would explain firstborns’ over-representation in intellectual communities.

Why would firstborns be more intellectually curious? If we knew that, could we do something different to make laterborns more intellectually curious? A growing body of research highlights the importance of genetics on children’s personalities and outcomes, and casts doubt on the ability of parents and teachers to significantly affect their trajectories. But here’s a non-genetic factor that’s a really big deal on one of the personality traits closest to our hearts. How does it work?

People looking into birth order effects have come up with a couple of possible explanations:

1. Intra-family competition. The oldest child choose some interest or life path. Then younger children don’t want to live in their older sibling’s shadow all the time, so they do something else.

2. Decreased parental investment. Parents can devote 100% of their child-rearing time to the oldest child, but only 50% or less to subsequent children.

3. Changed parenting strategies. Parents may take extra care with their firstborn, since they are new to parenting and don’t know what small oversights they can get away with vs. what will end in disaster. Afterwards, they are more relaxed and willing to let the child “take care of themselves”. Or they become less interested in parenting because it is no longer novel.

4. Maternal antibodies. Studies show that younger sons with older biological brothers (but not sisters!) are more likely to be homosexual. This holds true even if someone is adopted and never met their older brother. The most commonly-cited theory is that during a first pregnancy, the mother’s immune system may develop antibodies to some unexpected part of the male fetus (maybe androgen receptors?) and damages these receptors during subsequent pregnancies. A similar process could be responsible for other birth order effects.

5. Maternal vitamin deficiencies. An alert reader sent me Does Birth Spacing Affect Maternal Or Child Nutritional Status? It points out that people maintain “stockpiles” of various nutrients in their bodies. During pregnancy, a woman may deplete her nutrient stockpiles in the difficult task of creating a baby, and the stockpiles may take years to recover. If the woman gets pregnant again before she recovers, she might not have enough nutrients for the fetus, and that may affect its development.

How can we distinguish among these possibilities? One starting point might be to see how age gaps affect birth order effects. How close together do two siblings have to be for the older to affect the younger? If a couple has a child, waits ten years, and then has a second child, does the second child still show the classic laterborn pattern? If so, we might be more concerned about maternal antibodies or changes in parenting style. If not, we might be more concerned about vitamin deficiencies or distracted parental attention.

Methods And Results

I used the 2019 Slate Star Codex survey, in which 8,171 readers of this blog answered a few hundred questions about their lives and opinions.

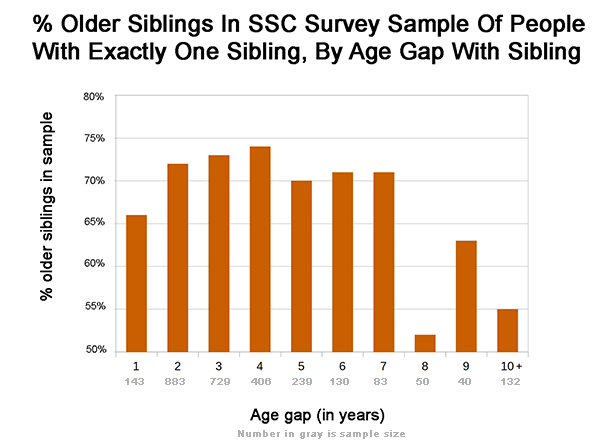

Of those respondents, I took the subset who had exactly one sibling, who reported an age gap of one year or more, and who reported their age gap with an integer result (I rounded non-integers to integers if they were not .5, and threw out .5 answers). 2,835 respondents met these criteria.

Of these 2,835, 71% were the older sibling and 29% were the younger sibling. This replicates the results from last year’s survey, which also found that 71% of one-sibling readers were older.

Here are the results by age gap:

Birth order effects are strong from one-year to seven-year age gaps, and don’t differ much within that space. After seven years, birth order effects decrease dramatically and are no longer significantly different from zero.

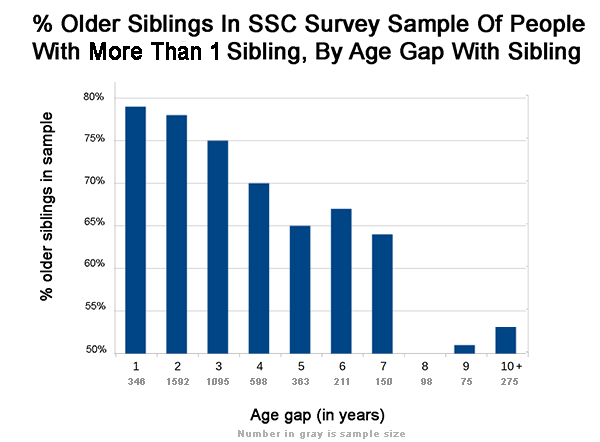

I also investigated people who had more than one sibling, but were either the oldest or the youngest in their families.

More siblings = more problems more of a birth order effect, but the overall pattern was similar. There is a possible small decline in strength from one to seven years, followed by a very large decline between seven and eight years.

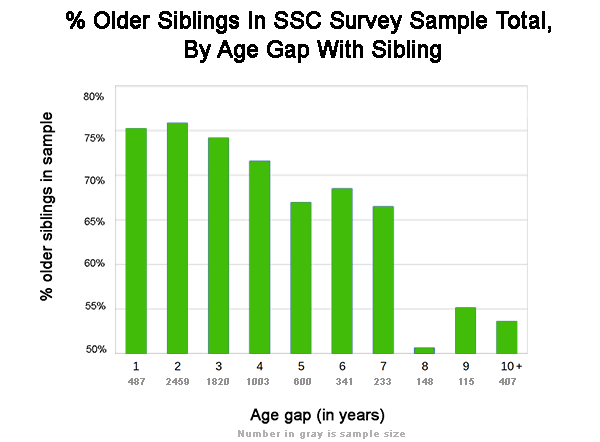

Here’s the previous two graphs considered as a single very-large-n sample:

The pattern remains pretty clear: vague hints of a decline from age 1 to 7, followed by a very large decline afterwards.

(Tumblr user athenaegalea kindly double-checked my calculations; you can see her slightly-differently-presented results here).

Weirdly, among people who reported a zero-year age gap, 70% are older siblings. This wouldn’t make much sense for twins, since here older vs. younger just means who made it out of the uterus first. I don’t know if this means there’s some kind of reporting error that discredits this entire project, whether people who were born about 9 months apart reported this as a zero year age gap, or whether it’s just an unfortunate coincidence.

These results suggest that age gaps do affect the strength of birth order effects. People with siblings seven or fewer years older than them will behave as laterborns; people separated from their older siblings by more than seven years will act like firstborn children.

Discussion

This study found an ambiguous and gradual decline from one to seven years, but also a much bigger cliff from seven to eight years. Is this a coincidence, or is there something important that happens at seven?

Most of the sample was American; in the US, children start school at about age five. Although it might make sense for older siblings stop mattering once they are in school, this would predict a cliff at five years rather than seven years.

Developmental psychologists sometimes distinguish between early childhood (before 6-8 years) and middle childhood (after that point). This is supposed to be a real qualitative transition, just like eg puberty. We might take this very seriously, and posit that having a sibling in early childhood causes birth order effects, but one in middle childhood doesn’t. But why should this be? Overall I’m still pretty confused about this.

These results may be consistent with an intra-family competition hypothesis. Children try to avoid living in the shadow of their older siblings, perhaps by avoiding intellectual pursuits those children find interesting. But if there is too much of an age gap, then siblings are at such different places that competition no longer feels relevant.

These results may be partly consistent with a parental investment hypothesis. Parents might have to split their attention between first and laterborn children, so that laterborns never get the period of sustained parental attention that firstborns do. But since an age gap as small as one year produces this effect, this would suggest that only the first year of childrearing matters; after the first year, even the firstborn children in this group are getting split attention. This is hard to explain if we are talking about as complicated a trait as “intellectual curiosity” – surely there are things parents do when a child is two or three to make them more curious?

These results don’t seem consistent with hypotheses based on changing parenting strategies or maternal antibodies, unless parenting strategies or the immune system “reset” to their naive values after a certain number of years.

They also don’t seem too consistent with vitamin-based hypotheses. I don’t know how long it takes to replenish vitamin stockpiles, and it’s probably different for every vitamin. But I would be surprised if giving people one vs. five years for this had basically no effect, but giving them eight instead of seven years had a very large effect. Overall I would expect the first year of vitamin replenishment to be the most important, with diminishing returns thereafter, which doesn’t fit the birth order effect pattern.

Overall these results make me lean slightly more towards intra-family competition or parental investment as the major cause of birth order effects. I can’t immediately think of a way to distinguish between these two hypotheses, but I’m interested in hearing people’s ideas.

I welcome people trying to replicate or expand on these results. All of the data used in this post are freely available and can be downloaded here.

A lot of angles have already been covered, but what seems most likely is:

– IQ gaps, when well-measured, and accompment gaps likewise come out to about 3 IQ points of advantage for firstborns. This fully explains your results given the extreme high IQ skew on this blog. (E.g. The Jewish advantage of 12 IQ points explains 8-15x over-representation in some cognitively elite areas. 3 points likewise makes an enormous difference at the tails that could easily account for the skew here.)

– There is good reason to think this is due to the womb. Most imprinted genes (an enormously complex and fast-evolving part of the genome, impacting key genes like igf2) result from the ongoing conflict of the parental genes wanting to gobble up resources and maternal ones wanting to conserve for future children and the mom’s own health. Later borns have lower birth weights on average (compatible with this theory). First borns are more prone to obesity (likely had increased nutrition available in the womb, leading to higher activation of the “growth-prone” pathways etc.). Later children just don’t get the same nutrition–a fresh womb makes a lot of difference to brain and overall growth development.

– Also possible and in accordance with your gap data: having a child at home stresses the mother and distracts her (and diverts resources from the ongoing pregnancy). The first born shares some but not all genes so their incentive is to own her time and attention, even if the stress impacts the pregnancy. The gap (if replicated in other samples…) results in a child with relative peace for most of the day for pregnancy and the first year or so during which most of brain growth happens. It may also result in time and attention focused solely on the new child, where either cognitive stimulation or some alone time matter. If the gap doesn’t replicate, ignore this theory as the first one makes more sense anyway.

“Decreased parental investment. Parents can devote 100% of their child-rearing time to the oldest child, but only 50% or less to subsequent children.”

I would say that’s temporary, and for most of the firstborn’s life, it’s the other way around: As soon as the second child arrives, the first child is deprived of 90% of its prior monopoly on parental attention (infants being vastly more demanding than walking-and-older). This profoundly changes how that older child looks at life, especially if there’s a prolonged gap between births and the firstborn already has fixed expectations.

I suspect it has less to do with parenting, than with “elder siblinging.” As the oldest, I had to brave the paths and take risks my 4 younger siblings didn’t. Also, I taught them “how things are” instead of sitting back and letting them figure it out for themselves.

I have 2 young boys, and I’m surprised you’re not considering the “bossy older sibling” hypothesis. My younger son can barely finish a sentence in our household without his older brother jumping in to correct him or answer questions for him. The older one has to find his own answers and gets to dictate the terms of all of their interactions, whereas the younger has his answers fed to him and must follow the lead of his brother.

I was surprised not to see this hypothesis listed: the presence of an older sibling could reduce the need to make decisions, experiment, and explore unknown territory. A child with an older sibling has the option of following their sibling around, copying strategies that the older sibling has already explored, and acquiring second hand information rather than experimenting.

What bothers me here is a really sharp cut off between 7 and 8 years gap. This isn’t how biological effects typically manifest, is it? Which makes me think there’s either a social effect in play or some peculiar glitch in the data. What takes 7 years exactly in a life of a typical American child/teenager or their parents? (Not American here)

But even then, if we assume it’s high school or something of this sort – some people will have their siblings born before they go to it, some in the middle and some afterwards. I can’t think of anything that requires such a stark delineation.

I do not think the histograms in the post allow to infer anything about the decline of the effect with age difference. To make such an inference one would need to compare the histograms with the distribution of age differences across siblings in the broad population. Imagine two worlds: in World 1 there is a marked decline of birth order effect with age difference and in World 2 birth order effect does not decline at all with age difference, bur few women give birth more than 5 years apart. Your histograms may be consistent with both Worlds or with a combination of them but do not allow to distinguish between World 1 and World 2.

In real world, sibling age difference of 2-5 seems to be much more common than 10+.

Unless I’m misunderstanding your point, that’s not an issue because Scott’s graphs show percentages rather than absolute numbers.

Out of the total number (A) of survey responders with a 3-year age gap, about 73% of them are the older sibling.

Out of the total number (B) of survey responders with a 8-year age gap, only about 53% of them are the older sibling.

You are correct that A is a large group and B is a small group, but we’re looking at percentages *of* those groups.

In a world with no birth-order effects, we would expect both these percentages to be about 50%.

I gave this in the Discord server as a joking answer, but it accidentally sounds a bit too plausible:

As anyone who’s been (or had) an older brother knows, the purposes of older brothers is to introduce their younger brothers to music and drugs. If you don’t have the older brother yourself, you have to seek those things out independently. Therefore…

(my younger brother finds this plausible, for the record)

This is a really huge effect, something you do not find often especially if the reason is not biological. There probably is a tail-amplification effect to get as high as 70%, but still, this is very large.

I wonder which other characteristics have such a strong correlation with birth order. I am aware of homosexuality, but this capture elder/younger effect on maybe 2% of the population – not much.

Is there a size or weight effect? Other effect on quantitative measurable trait? IQ is weakly affected I think, but not to the extend of this 70/30% unbalance.

Listing everything that we know correlate with birth order, together with correlation strength, may help for finding the underlying cause….

A point in favor of the sibling rivalry + resource investment idea: Parents may invest more into the older child because they’re closer to reproducing successfully, while younger siblings may not get the chance (e.g. because of high infant mortality). So a one-year age gap situation won’t always mean undiminished attention for a year followed by equal care, parents are more interested in supporting the older sibling because they’re already one year ahead in the not-dying-of-pneumonia-and-wasting-all-the-investment game.

But what about the drop-off at year seven? Does it represent some kind of “in the clear” zone that frees parents to invest more into the second child? Infant mortality dips pretty hard after the first few years, so maybe seven is just the number at which the fitness scale goes from “shore up kid #1” to “kid #1 is as safe as possible, focus on #2”.

Some random theories.

A lot of preschool and kindergarten programs are half-days. Elementary school starts at 6 years old… but that’s still first grade, and parents do tend to be more involved during first few months of first grade. But a few months in to first grade, dad comes home a little early every so often, resulting in a new pregnancy probably about halfway through the school year, who would be born 9 months later when their first child has turned 7.

I suspect vitamin stockpiles might take a long time to recover. From what I understand, the body doesn’t absorb much beyond what it needs at the moment in terms of most vitamins. Plus consider how difficult it is to keep up with nutrition when running after a child all day. So it’s possible that the mother’s stockpile doesn’t start recovering until the child enters kindergarten at 5, and takes at least 2 years to recover.

And then you have income considerations. Don’t high-income people tend to have fewer kids, partly because of better access to birth control?

Another factor. If your kids are two years apart, you’re likely giving the younger one hand-me-downs. But who stores baby things for more than 5 years? And you’re always going to be more excited about giving your child something new than you will be about giving your child something you had on hand. Plus, as the child starts to show actual interests, the items reflect the interests of the child, but with hand-me-downs, you’re being exposed to your sibling’s interests, not your own.

I was curious how this broke down with age, so I made this figure from the raw data. Error bars are standard errors (computed as sd/sqrt(n)).

The effect seems to be robust at basically all ages, with every reader age cohort having about 2x more younger siblings than older siblings. I did not restrict the data in any way, except to exclude ages 75 due to noisiness. I also imputed all blank sibling counts with zeros.

Is there a website where people who are not intellectually curious go, and can we get them to take a survey, to see if we get the opposite result?

Did you actually do this? Was this pre-planned, but you didn’t need to do it? Or did you do it without looking and so you didn’t notice how many it affected? In the public data, I only see a single non-integer age gap, and it’s 0.000057, ie, a half hour.

I get about 60%, less if we restrict to people that have an older sibling, rather than just an older sibling gap.

Specifically, I believe that you got the 70% figure for zero-year age gap people by incorrectly handling people who reported zero for both older and younger siblings.

My hypothesis is that the difference is caused by different patterns of learning, which are affected by an older sibling being present. Think of it this way. A firstborn is obliged to take more social and intellectual risks in establishing the best strategies for interacting with their environment; this will result in a personality that is more comfortable (or at least better acquainted) with unpredictable situations and systems. (Parents help with the bigger picture, but not the social world kids or teenagers inhabit, as they’ll be too old.)

The younger sibling comes into a social world that is pre-structured: the norms of their environment have been present since birth, and the environment is itself substantially less interesting (for values of ‘interesting’ as found in ‘may you live in interesting times’.) What this should produce is a younger sibling who is made more uncomfortable by more unpredictable environments, and who’ll therefore find the open-ended nature of intellectual inquiry aversive.

This hypothesis predicts the decline of the birth order effect over time as the social environment changes. It also suggests that having an older sibling of the opposite gender should produce a smaller effect, given that the different genders will occupy different environments due to cultural norms.

I may test this against the data and see what I get back.

My N=1. Younger sibling (~4yrs), opposite gender.

I followed in my older sibling’s footsteps, activity-wise, largely because my parents couldn’t invest the time into two completely separate sets of activities. I’m not sure this applies to more generalized “interests” though: I definitely had and have my own interests, which my parents supported, provided they didn’t require too much parental time-investment.

But I also got to experience most of the world 4 years earlier than my older sibling (e.g. watch “mature” tv shows; read more “mature” books), since having separate rules for the two of us was impractical. This arguably fostered any intellectual curiosity, since my childhood was less guarded.

Minor aside: I’m skeptical of the “intellectually curious” moniker: this seems almost impossible to define/test, and a bit self-serving.

It’s gonna be hard to distinguish between decreased parental investment and changed parental strategies.

It should be possible to look between half-brothers, where a new parent hasn’t had time to change parental strategies, but still has to look for a second child, but the problem is that the genetic difference is bigger than between full siblings.

Also, the strategies of the new parent are going to be impacted by the strategies of the experienced parent.

I’m curious how different the dynamics are for family units with half-siblings (where some siblings have one biological parent and others have two in the unit) vs. families with step siblings (where each sibling has exactly one biological parent in the unit).

I think this is strong evidence that there is a systematic error, although I don’t have any hypothesis about what causes it.

Does everyone’s survey list the choices (older, younger) in the same order? If Google doesn’t let Scott randomize the order on the form, did he vary it from year to year?

Not necessarily. It could be that the better-nourished twin is more likely to make it out first.

“Intra-family competition. The oldest child choose some interest or life path. Then younger children don’t want to live in their older sibling’s shadow all the time, so they do something else.”

This sounds weird to me. I have the assumption that a younger sibling would choose a life paths that appear different than their elder sibling, but would likely be from the same set of choices the first sibling had. The first sibling chose scientist from a list of [scientist, teacher, or stock broker] and the second sibling chose stock broker. However, if the first sibling had chosen stock broker, than the second would have chosen scientist. I don’t think scientist is the top choice among sets presented to children.

I would put forward a different hypothesis. Something like “The eldest child is always a pioneer who has to make decisions and form their models of the world completely on their lonesome. Each younger sibling make decisions and form models with information, context, and contrast obtained from their elder siblings and not on their lonesome.”

I think this happened in my family–my sister was math-phobic and artsy in high school, but once she got to college and out of my shadow, she fell hard for statistics and hard science, and ended up as an epidemiologist.

Might there be a “the guy everyone asks” effect?

A strong pattern I’ve seen is that in many groups you’ll get someone leading the pack, perhaps only with a thin lead in capability. Perhaps they’re just the person who opened X up and took a go at reading the manual, perhaps they put a few extra hours in early on.

Roll on a bit and when others face the same questions/challenges/problems they don’t have to work things out from scratch themselves because Bob over there already knows about X.

So Bob has a steady stream of people who go to him to ask about X.

Bob isn’t a deity, he doesn’t know all about X but he gets used to quickly looking up info about X to answer questions and pretty soon he develops a good understanding of X.

In office environments it’s noticeable that people can almost get trapped by not being Bob. Bob has no higher authority to ask but everyone else has Bob so they never get forced to become authorities on X while Bob is pushed to do so.

As an older sibling you’re gonna have quite a few X’s where, thanks to a head start you know more than your siblings.

I was about to say “this assumes that the eldest sibling is reliable at gathering information and willing to work on that task for others” but oh wait…

Interestingly, this can be good or bad. In a small office, it’s not all that great to be the guy everyone knows can solve most of the computer problems–it’s easy to end up with your normal job plus a part-time unpaid computer support job.

A proposed explanation for some of this effect and a suggestion for further questions on future surveys:

The effect I have observed is that older siblings’ personalities matter a lot in figuring out the effect on younger siblings.

My personal example is that I tended to be very intense and intellectually curious… and I demanded that of my (considerably) younger brother, for instance trying to insist that he understand math that was ahead of his level. The result was the opposite: he reacted to this by defining his personality, as he grew up, to be a foil to mine. He became an unserious jokester who faked his way through school, and who got things done with hard work rather than cleverness.

I suspect that if you ask people about their siblings’ personalities you will see a lot of sharp differences between older and younger siblings in two-sibling pairs. (More than 2 and I have no idea, though).

Also, growing up, even as early as grade school, I noticed that a large majority of the ‘cool’ kids seemed to have older siblings. I figure that they were socialized far more, growing up, than the eldest children were — and in the process trained how to act, what to do to fit in, and what external signals to listen to. I would not be surprised if, however, people whose older siblings were very pro-social might often end up being the opposite, in reaction.

…Which definitely does not sound like the personality profile of the typical person here (myself included). I think you may be on to something.

Can we compare it to the number of subscribers that are single child? It should be possible to compare the fraction of single children among subscribers to that in the society (accounting for age distribution). I would expect that the fraction should be close to that of first children, but it would be exciting if that is not so. It would suggest that the presence of a younger sibling has some effect on the personality traits.

A difference in rates of only children vs first children could also arise from some of the other effects discussed above. E.g. if easier/better babies make parents more likely to have additional kids (and have them sooner), that would also lead to differences between first vs only children.

I have been thinking about incest taboo lately and the way that it might interact with birth order number of Children. I have a theory that the prevalence of romanticized incest in Japanese media might be related to the low birthrate and people not having actual siblings to relate incest to. Do you have any data on this and do you think you could inquire about in on your next survey.

Typo: “become less interesting in parenting” -> “become less interested in parenting”

As your children progress to their teenage years, you also become less interesting in parenting.

“HEY! Are you even listening to me??? Take those goddamn earbuds out and LISTEN, damnit!”

Presumably at least some people who are >10 years older than their only sibling have a sibling who is too young to be answering the SSC survey. Does this explain any of the effect?

Did you filter the data to siblings that shared the same mother and father?

If not 7 years might be a result of some seperate factor such as a social dynamic relating to divorce.

I have two sons (the third’s on the way in a month or so). The elder is indeed the more scholarly of the two, the younger being more boisterous and outgoing. Part of this is simply innate temperament–the elder is very introverted and fussy–but I can see how their ages could contribute. Possibilities not mentioned in OP, though other commenters have raised related points:

1. Firstborn children are more likely to spend time alone entertaining themselves for a while, and therefore become more contemplative.

2. Firstborn children are more likely to direct/control things when siblings play together. My older son gets to be in charge a lot, which means his interests tend to dominate play and the younger son takes cues from him. Even though Kid2 turns five in a few months, we have only a limited sense of his particular personal interests because he spends so much time aping his brother. Left to his own devices, he would probably not be nearly so fascinated by electronics.

Granted, my kids are somewhat weird by modern standards (homeschooled, minimal screen time, not a lot of friendships outside the home and structured environments such as church).

Waaaait….

Doesn’t age gap, by definition, means younger siblings are born at higher parental age and thus have higher mutational load? Couldn’t that be (at least one of the) reason/s for the differences between siblings?

Wouldn’t you then expect the birth-order effect to get stronger with increasing age gap rather than weaker?

That sharp threshold is unbelievable. Even if there were a sharp threshold, eg, 7 years of school=MS+HS, that should be blurred in the data by all sorts of noise, such as the rules of converting age into school cohort. Different people round ages differently, even just for answering this question. The developmental psychologists say 6-8 years, not 7 on the nose.

One simple possibility is that parents get worse as we get older (less energy, more health problems of our own, more accumulated genetic damage to pass onto our kids), and so the first kids get a little better deal than the later kids. I definitely notice the difference in my energy level between playing with or more generally parenting my oldest and youngest, eight years apart!

Developmental psychologists sometimes distinguish between early childhood (before 6-8 years) and middle childhood (after that point). This is supposed to be a real qualitative transition, just like eg puberty.

Or more. The age of reason, the age of criminal responsibility. . . it’s been recognized throughout history and often more important than puberty.

Could there be an effect from breastfeeding? (I’m on my phone so I only read the abstract, but my thought was the nutritional/etc benefits and/or maternal bonding at a young age might improve iq or lead to a parent-child relationship more likely to foster intellectual curiosity.)

My other thoughts are whether there could be an effect of parental favoritism, though from what I found we should then see a lot of eldest and youngest siblings. I also wonder if there’s an effect from the difference in first vs subsequent births (increased likelihood of complications during repeat c-section, labor tending to last longer during 1st births, etc), though I’m not sure what.

Has parental age been controlled for? Wouldn’t first borns generally be born to younger parents than their younger siblings?

>>Overall these results make me lean slightly more towards intra-family competition or parental investment as the major cause of birth order effects. I can’t immediately think of a way to distinguish between these two hypotheses, but I’m interested in hearing people’s ideas.

One of the nice features of a specifically action-oriented (decision-oriented/ intervention-oriented) strategy for (scientific) theorising is that assists in identifying when and how distinctions in the theory make a difference. Tackle the question of how to distinguish by asking what intervention differences would be recommended if one rather than the other were true. If intra-family competition were the causal factor, would you recommend encouraging younger siblings to follow their own interests irrespective of that of older ones, try not to make a fuss about the achievements of older siblings, or something else? If parental investment were the major cause, would you recommend parental attention be switched from older to younger siblings earlier or more severely, or sourcing additional care from extended family, nanny or other carer for younger siblings?

If there would be a difference in recommended intervention, there is a ready made (theoretical) experiment that could distinguish the hypotheses. Ignoring human subject experimentation ethics, one could arrange a blind study. For a lower cost option, one could look for relevant distinguishing factors in the natural population. I’m not suggesting that the above alternatives would be the best ways of distinguishing the hypotheses, but that asking the question “what would we do differently depending on which were true” can be a fruitful way of thinking about it and can at least lead to some ideas that could then be improved upon in more experimentally practical dimensions. If, in fact, there is nothing that would be done differently depending on the truth of the alternative hypotheses, then there is a practical sense in which the distinction doesn’t make a (direct) difference – for (direct) intents and purposes the two hypotheses are the same.

On the other hand (there had to be one, didn’t there) even if there were not an immediate application, to practical child-rearing, of the knowledge of the relative merits of the two hypotheses, there may be an indirect (still practical, but only eventual) benefit. We might not be able to immediately easily exploit knowledge that differential parental investment is significant because the financial, personal or public policy cost of providing more caring resources might be too high given the current state of social and economic development. However, validly disconfirming the intra-family competition hypothesis might result in faster and more efficient use of scarce investigation resources in developing a theory of family dynamics and individual achievement, since it would cut short investigation of a theoretical blind alley. And this may eventually lead more quickly to a practical recommendation – perhaps (implausibly, but for sake of an argument) it is then more quickly discovered that the simple act of only one parent playing with a younger sibling with the specific aim of encouraging them to discover their talents and interests, for only one hour a week for the ages of 4-6, would be sufficient to reverse the birth effect.

The specific application, to the design of the hypothesis testing study, of this profoundly insightful observation, I leave as an exercise for the reader.

I had previously advanced the hypothesis that being a first child correlated with developing thing-focused rather than people-focused interests and personalities due to the presence or absence of near-peer humans to interact with during (very) early childhood – with SSC then selecting for thing-focused personalities. That is I think somewhat consistent with this more detailed analysis, though in that case I’d have expected more of a peak at 2-4 years rather than a strong effect at 1 year that declines slowly through year 7. But it is interesting that the two other cited examples of this effect being recognized are in mathematicians and physicists. Has anyone looked for birth order effects in high achievers in people-focused fields? Actors and politicians strike me as easy places to find mineable data, and if we find a younger-sibling preference in those fields that would be significant.

Harvard undergrads are consistently 55% oldest (excluding only and middle).

last 6 years

Does choosing to answer a survey further filter on thing-orientation?

One confounder for Harvard is that parents may only be able to or want to invest in an expensive private college education for one of their kids (or fewer than all anyway). So even with two equal kids, if the first kid goes to an Ivy, the second kid perhaps accepts a full-ride scholarship to a second-tier school instead.

Also, the demographics that send kids to Ivy League schools tend toward small families–not five kids raised free range and sent to public schools, but one lavishly raised and educated child sent to private schools and test prep classes to max out his chances of getting into Harvard.

A study in the Netherlands found eldest child and only child overrepresented among politicians. They hypothesize it’s parental investment, which could be a huge factor in winning elections even if there is no personality or interest change. I don’t think this study disapproves your hypothesis, but you need a more merit based sample. Maybe check if younger siblings are overrepresented in HR?

It’s also possible that having a younger sibling increases intellectual curiosity, rather than that having an older sibling decreases it. It seems tricky to test which of these is the case.

I had this thought as well. We have one child, ten months old, and she is fascinating. I’m an only child, and never spent much time with babies before having one. Seeing a tiny human unfold in realtime has been a very enjoyable learning experience. My husband has one brother about four years younger than himself. Feeling his baby brother kick inside the womb and later arrive home from the hospital are my husband’s first memories. He doesn’t recall much else of his early childhood or his brother’s too clearly, but I’m sure growing up *with* someone had some effect on his perceptions. Just being around a baby is an education.

Can we study only children next time? Naturally, we love hearing about ourselves.

I’m also not sure why so many people assume the sibling difference expressed here is so negative. My husband and his brother are both very successful. The data holds true mainly in the sense that my husband has traveled more and maybe taken a few more personal and professional risks. But his younger brother is an MD PhD. So even though my husband didn’t manage to get him into reading this blog, my brother-in-law has definitely been using his brain for something. My point is that “intellectual curiosity” might express itself in being an engineer who reads SSC and collects obscure musical instruments (my husband) vs becoming a doctor who goes to concerts and runs marathons (his brother). There’s no real problem to correct there.

Hm. I don’t know if this is correct but the dropoff at high age gaps might be even more pronounced than the data shows.

If a 20 year old with a 15 year old sibling answeres the survey this will give a hit at the +5 year score but we probably wouldn’t expect the 15 year old to read SCC and thus provide the necessary vote to cancel this out.

Although I don’t remember the SCC age statistics enough (and this would have to account for age + sibling age gap) to know if this moves the statistics around any significant amount.

My experience as an eldest child is being the guinea pig. I don’t think it’s that younger children avoid following in our footsteps, but that they are able to avoid many of the same experimental things older children go through. They’re given an additional authority figure they can rely on to know any given answer. On top of this, older children become accustomed to taking more risks, which I suspect lines up with intellectual curiosity.

Large gaps between children would reopen the need for experimentation as the world the younger goes through would be noticeably different.

Couldn’t the original firstborn effect be driven by parental decision-making?

Suppose that SSC readers (type (G)ood) exhibit early intelligence and make parents more positively inclined to having more kids. Suppose 50% of childs are type G, and every type G child motivates parents to have another kid. But parents only have another kid 50% of the time after they have a type B child.

If the first child is a G, they will definitely end up in your survey, because they will have a sibling. But if the first child is a B, only half of them will end up in your survey, because the other half’s parents decided to stop at that point.

If we assume that all firstborns and secondborns end up in your survey, then we can use Bayes’ rule to determine that 4/7 of G kids (i.e. SSC readers) are firstborns. But it’s all child-to-parent effects, not parent-to-child effects as you are surmising.

This just demonstrates that we can get unexpected values of P(FB|SSC reader). It would be easy to change the probabilities to get us to 70%.

This is a cool idea, but you would have to have parents determining children’s types as early as 1 year old (since there are birth order effects at 1 year). Kids aren’t even talking then, and even when researchers can measure personality traits they seem really unstable around that age. So I doubt this is it.

Doesn’t most positive qualities positively correlate? I imagine robust, healthy happy babies are more likely to (1) turn out well and (2) encourage their parents to have more kids.

I agree — the biggest stretch is that SSC-preferences are correlated with “easy baby” — I don’t see why this would be the case, and could also imagine the reverse to be true, e.g. if SSCers had tendencies toward aspergers.

However I can definitely attest from my experiences and those of my close relatives that there are child characteristics that affect your preferences for more kids, even in the first year. It’s mostly down to easy baby or hard baby, but this difference has a huge impact on parent quality of life. Again, it’s hard to form a clear theory for why those would be linked to SSC-reading preferences. Too bad you can’t ask people when they started sleeping through the night.

From talking to a lot of other new parents, I’m quite confident that many, even most, final decisions to stop having babies are made when the youngest is less than one years old.

By the time your youngest has her first birthday, if you haven’t already decided to stop, you’ll have forgotten how incredibly hard the beginning was and that removes the biggest reason not to have another.

I want to bump this idea. Parents will not want to have children for a while after a difficult birth/pregnancy, or after a child that is sickly or has complications and needs extra care in their first couple of years, which would make more difficult children likely to be the youngest child, or at least have a large age difference with the next youngest child. This would presumably be correlated with adult health and therefore life success and IQ.

Maybe a question about early health complications of siblings (natural vs. cesarian birth, autistm/down, etc.) could help measure this effect?

Are there birth-order effects for adopted kids? Looking at the order within the biological family and within the adopting family should narrow down the theories.

Agreed. Scott, I think your survey does not ask about adopted status, and I suggest it do so in the future. I am the second child in my family but the first-born of my mother, as my older sibling is adopted. So I probably show up in your data as a “second” kid. Asking about adopted status could go a long way toward separating out some of the possible hypothesis (although it also adds another confounding factor).

This is super fascinating.

I think you’re making too much of the threshold around 7. If the true model was a monotonic decline in birth order effects with an age gap, you would be very likely to see a jump like this in the data from random chance alone. e.g. you’re basically conducting 9 hypothesis tests: (i) is there a jump at 1? (ii) is there a jump at 2? (iii) is there a jump at 3? etc.. There’s a very high probability that one of these will deliver a false positive. Most likely, the low birth order effects at 8 years are just a random outlier which is drawing your eye to this result.

My interpretation of these graphs is that birth order effects seem to be monotonically declining in the size of the age gap, but it is hard to say a lot more given the sample size.

I’m less willing to dismiss the threshold around 7 because it showed up in two independent samples (1 sibling and more than 1 sibling)

Good point. Even if there was a random drop in every sample, odds are only 1/10 it would appear after the same number. That definitely shifts my priors a little more..

I don’t see a need for the hypotheses Scott postulates given that, with a normality assumption, the overrepresentation of first-borns follows directly from the small birth order effect on IQ that has been robustly demonstrated. Contrary to what Scott says, there’s a small IQ effect favoring first-borns, equivalent to 1.5 points (0.1 SDs). If first-borns average 101.5 and second-borns 100, the relative prevalences of first-borns versus second-borns at various IQ levels look like this:

IQ>100: 1.08 first-borns to every second-born

IQ>115: 1.16 first-borns to every second-born

IQ>130: 1.26 first-borns to every second-born

IQ>145: 1.38 first-borns to every second-born

IQ>160: 1.52 first-borns to every second-born

The way in which a small difference in average IQ levels causes quite substantial differences in the right tail may be sufficient to explain the overrepresentation of first-borns among intellectually eminent people (and SSC readers as well). However, one may additionally postulate that there are other small mean differences favoring first-borns that affect these outcomes via similar tail effects.

There are 2.4 first-borns per second-born here, so either SSC selects for >200 IQ, or it’s something else.

(or your 0.1 SD number is way too low, I guess)

1.5 points is probably too low because it’s based on observed test scores that contain measurement error. Moreover, younger siblings benefit from the (possibly cognitively “hollow”) Flynn effect in relation to their older siblings. If the real effect it, say, 2.5 points, the ratio of first to second borns is 1.47 at IQ>130. And, as I said, IQ may not be the only variable with small mean differences and large tail differences.

How did you calculate those numbers?

An anecdote about twins: I’m an elder twin, and I definitely took on more of the “older sibling” inter-family role, while my twin sister took on more of the “middle sibling” role. But as my parents say, I popped out of the womb ruddy and quietly looking around, while my sister popped out an hour later, blueish, eyes shut and screaming. Maybe the child who pops out first isn’t actually random?

Our particular sibling order effects may also be affect by the fact that we have a younger brother – so same-sex competition for me, but not my sister. Did the survey look at or even collect sibling gender? That might have interesting effects.

I’m not a twin, but I was coming to say basically this. I don’t think it’s implausible that the effect would hold for twins. I’d expect the one who comes out first to be the physically stronger one more often than not, which probably means the one who got a greater share of the nutrition in utero.

And if this is correct, then it’s evidence that maternal nutrition is the cause (or part of the cause) of the birth order effect in non-twin siblings.

(Also: I find this topic really interesting and was excited to see a new post on it)

Agreed. There is research about effects of first-born twin (“Twin A”) versus second-born (“Twin B”). One study: “Comparing the perinatal outcome of second twin in both groups, the odds for APGAR score ≤7 was 3.385 times (OR-3.384, 95% CI 1.2099- 9.4684, p=0.02) in the vaginal group compared to the caesarean group.”

It’s possible that being the first-born twin itself is indicative of something, and also possible that the second delivery is subject to more complications.

This effect might be entirely separate from the other birth-order effects discussed so far.

> Weirdly, among people who reported a zero-year age gap, 70% are older siblings. This wouldn’t make much sense for twins, since here older vs. younger just means who made it out of the uterus first.

Even for a non-twin every minute that passage thru the birth canal takes longer increases the risk for the new-born. I assume that the situation for the twin doesn’t get easier with every minute of labour either. I guess that can be confirmed with Apgar scores of second twins. Which might push them into the role of underdog with their twin in many cases – like a younger sibling.

I came here to say this too – my model was that if you’re having a caesarean, they often fish the big twin out first, and a 30 second google found a paper supporting my prejudice, “As expected, first-born twins had greater birth weight than second-born twins.”: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5100672/ (tiny sample size and I haven’t actually read it)

We already know that birthweight is linked with IQ / life outcomes etc. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-health-iq-birth-weight-idUSKCN18E29J

If parental investment were the key, shouldn’t both members of any set of twins immediately get a knock-down? I can see how a 1-7yr older child might exert enough of an extra pull on resources that it would be the younger who gets the short end of the stick, but twins should be negatively effected roughly equally, especially if of the same gender, right? Is this something the current survey data could answer?

Twins take a slight IQ hit, so they should already be underrepresented among SSC readers.

I vote for run the test again next year. If you still get a drop-off from 7 – 8 years, then it’s worth thinking about. Esp if you get it among people who are new to the quiz.

Otherwise, it’s not a big deal, IMAO

I think there is another major hypothesis I don’t see listed: The figure it out for yourself effect

The younger sibling doesn’t *have* to be intellectually curious, because there is already a path he can follow which was paved by the older sibling. The younger sibling observes and imitates what the older one before him did without having to figure it out from first principles. It’s possible with a sufficiently large age gap, the younger sibling becomes unable to directly observe and relate to what the older sibling did at the same developmental time and therefore has to figure it out for himself again.

If parental investment is what makes the big difference, then we’d expect to see only children doing much better than either older or younger children by a lot.

Yeah, this was my first thought as well.

And to make a broader point: I always see speculation on birth order effects built around the child’s relationship to the parents (e.g., parental investment, competition for parental attention). But shouldn’t the relationship with the sibling(s) themselves be the most obvious thing to consider?

I like this as an account of the general decline in chart 3. It doesn’t (yet) account for the big jump at year 8 though. Any thoughts on that?

Children become capable of being deputy parents at around that age

Of course, they will attempt to do so much earlier 😉

But even if this ‘deputy parent’ capability went from nonexistent to fully capable at age 8 (which it doesn’t), *and* were fully utilized by parents (which it isn’t) – how would that explain the younger kid’s figure-it-out-for-yourself level going from “much less than firstborn” (when gap = 7 years) to “equal to firstborn” when gap = 8 years?

It seems you’d have to argue that the presence of the deputy parent during younger sibs’ first year has a big ongoing impact on the latter’s tendency to figure things out for themselves. Does this seem plausible?

As a father of four, I think there is a pretty sharp cutoff around that age, yes. Even down to the child’s ability to carry the younger sibling around.

You characterize it as “figure-it-out-for-yourself” but that’s not how the studies say it. A first child has all parental resources until the younger sibling comes, the younger sibling has less parental resources. But if you have a sibling 8 years older, suddenly you get equal parental resources to the older child because you have three parents. I think it’s possible.

Since having my second child, I’m finding myself astonished that not everyone thinks parental investment is the clear answer here. We absolutely treat the kids differently, for most of the reasons you mentioned: less time because older child monopolizes that time, less worried about things in general, etc.

(For the record, they’re 2 years apart)

The only way I can imagine this *not* having an impact is if you assume that parenting basically doesn’t affect outcomes at all. Which I guess is a pretty common belief on its own.

I wonder how true this is generally? I suppose it depends on what was meant. My observational experience is that the younger child monopolizes time once they come along, and the older child spends much more time left to their own devices/in daycare/in school/etc. This would seem to bear out in the trope that older kids get jealous/act out because the younger child is getting seemingly all of the attention. I guess the older child got more attention at the same age as the younger one, since presumably (hopefully?) some time is still going towards the oldest where with the first child it all went to the one child, but over time I would expect the younger child to end up taking more…units of parenting.

Maybe just the fact that there was a significant change here is important (the younger child has always had an older sibling, the older sibling at some point did not and now suddenly does)?

This is feels pretty desperate, but taking a stab at the 7-8 year discontinuity: SSC readers’ families likely send their kids off to college. So youngest siblings with a gap-to-nearest of 8 years or more were usually not beyond elementary school when they became the ‘only child at home’. The resulting increased parental involvement had a chance to affect the kid before the ‘parental influence window’ closed with the grade-6 advent of middle school and (soon) puberty.

I like this theory. I had a brother who was 8 years older who left home when I was 9 or 10. I definitely remember my childhood as divided between a period where I had an older sibling around and a period where I was essentially an only child. Seems pretty plausible to me that there could be something developmentally significant about going through the tween/puberty years alone as opposed to with an older sibling around.

Unfortunately I doubt you’ll have the sample size for this but I’d personally want to see if the effect is consistent over age? Doesn’t serve to differentiate between intra-family competition or parental investment but would be interesting.

I would love to see all of the above bucketed by age of responder, to see if there some sort of societal change hypothesis that makes sense; particularly in instances where the siblings age is an age group that has a lower likelihood of reading a blog such as SSC.

Epistemic status: anecdotal

None of the 5 solutions on offer in the article ring true to me.

The idea that sprang immediately to mind to me was more along the lines of peer guidance. The eldest sibling is the one to experience everything for the first time within that nuclear family cohort. They have to make sense of it in a novel way that probably isn’t legible to a parent so far removed from that stage of development. But the idea of an inherent peer guide that could make sense of experiences or explain them in a legible manner?

If this were the case I’d expect to see large (>9yr?) gaps in birth order “reset” the intellectual curiosity button. I’d also expect that non-nuclear familys, eg close cousins, to show a similar effect to birth order as well but within age hierarchy for cousins instead of siblings.

I like this idea of older siblings being peer guides. Older sibling gives a leg up on social ques. They know what is cool because what older kids like is cool. First borns lack this source in navigating the ruthless status games of early years of peer group existence. If older sibling is socially succesful, the younger sibling will imitate. If the older sibling is socially unsuccesful the younger sibling steers away from that path.

I’d assume older siblings will have longer childhoods, play with toys to older age, start cool teenager stuff like skateboarding or playing an instrument in a rock band later (in my youth these were the things, I don’t know what they are now). That way younger siblings have different path than older siblings.

I don’t seem to have enough english to but this elegantly, so: maybe first borns are more likely to end up social outcast nerds, because they don’t have the guidance of older siblings, and nerds are self selected to read this blog and answer it’s survey. It would be interesting to see what the younger siblings are more likely to do. More likely to like Metallica, play team sports? 🙂

It is a weird epistemic situation that I have two kids, see the differences between them… and still have no idea whether those differences are caused by social influence of the other sibling, different parenting, different mix of genes, or perhaps maternal hormones.

On one hand, it is tempting to believe that it is the impact of the other sibling or the family setting, because that impact is what we observe every day (while the biological factors are hidden from sight). We will never be able to give 100% of our attention to the younger child, because we are now more busy, and seeing the same “first steps” for the second time is less interesting.

The older child has regressed in some areas psychologically; things previously done solo became now “hey, if my sibling doesn’t have to do this, why do I? I also don’t know how to do it!” The younger child is copying the older one like a crazy monkey. According to this, it should perhaps be the other way round; the younger child should be more intellectually advanced (controlled for child’s age). But perhaps the strategy of copying competes with the strategy of exploration, and the younger child rarely gets an opportunity to discover something alone. Copying gets advantage in short term, but discovery more likely leads to Nobel prizes.

On the other hand, the kids were quite different literally since the moment they were born. (I find it difficult to imagine how a parent with more than one child could ever believe in “tabula rasa”. Differences between near mode and far mode, I guess.) The older one immediately tried to kick me and jump out of my arms; the younger one was sleepy and mewling. The relation to Nobel prizes seems less clear here.

When I think about my younger sister, she was a strong case of “not wanting to live in older sibling’s shadow”. I believe this is a harmful strategy on average, because if there is a genetic predisposition for being good at something, the older sibling is likely to try it first, and the younger sibling is likely to avoid it, thus avoiding exactly the area of their biological advantage. (Hopefully, there are multiple such areas, and the older sibling does not have enough time to become good at all of them.) For example, after I became a math/computer nerd, my sister refused to use computers. Only in her 30s, after trying a few different jobs, she decided to give computers a chance… and she almost doubled her income overnight. (She did not become a programmer, only a skilled user, but even that made a big difference.) I wonder what an earlier change of mind could have brought; whether computer use could have helped her significantly e.g. in her artistic attempts.

Give parents basic income when their second child is born. (So their attention is first divided between the first child and the job, later between the first and the second child.) Make it conditional on providing various reports about the second child, such as when it learned which words or skills. (So they have to pay attention to these things, even if they are not new for them.) That should reduce the parental investment difference.

Alternatively, give parents basic income since the first child, under condition that the children will be raised in separate rooms and will never see each other. That should reduce the intra-family competition.

I’m curious about what role gender plays, especially in more traditional environments. This is personal for me: I’m the 2nd of 4, the only boy with three sisters. I’d say I’m more typically a “first child” if that means intellectual curiosity. My oldest child is a boy, however, and my second (18 months younger) is a girl. It’s not that my 2nd isn’t intellectually curious, but definitely somewhat overshadowed by my son. I don’t know that this is exactly a problem, but I’m also not sure it’s not a problem. My daughter, while maybe not as “intellectually curious” as my son, is certainly more daring and independent. Which is also maybe an effect of being a younger sib.

I have a terrible time trying to figure out how much is just temperament, but also how much temperament is influenced by birth order and so forth. Maybe there are just too many inputs to be able to reach much of a conclusion (for instance: my third child, a girl, is autistic, and requires a great deal of attention; so my second child might just be in a weird spot anyway.) This is a really hard problem to get meaningful data about with so many variables. But I’d like to see what effect gender has.

Are there known effects of having a sibling with some kind of disability, in terms of impact on other siblings? I’d expect the disabled sibling to take much more parental attention.

I have two younger siblings 2 years and 6 years younger. I definitely have the most intellectual curiosity and the youngest has more than the middle. I wouldn’t go so far as calling it intra family competition but that is closer to what my experience indicates. I think it had to do with the fact that I was older meant I got to decide what TV we watched, what games we played, and how we would accomplish goals like how to build the best sandcastle or divert the ‘river’ of rain water as it went through the woods ect (obviously not 100% of the time but the vast majority). If there was something I found interesting and wanted to explore it happened; If the middle sibling wanted to explore something it had to be done independently, or it required convincing me to indulge which ran the risk of me just taking over instead of allowing for self discovery.. The youngest was less of a peer and by the time she was old enough to be exploring I was old enough to understand that was how she needed to learn and encouraged it or just stayed out of the way. The Youngest still didn’t have as much autonomy as I did, but she had more than the middle sibling.

My working hypothesis was that older siblings taking a role parenting duties helped expand intellectual curiosity, but if that was the case, I would expect the effect to be more dramatic at larger age groups and insignificant at 1 year. I’ll lean to Intra-family competition now, since that’s more consistent with the data, and still makes sense observationally.

That’s still my working hypothesis, with the difference that I think it may be ‘figuring out what little sib wants & getting it for them’ that could be the trigger. Even with 1-year age gaps, the elder sib is better at communicating, manipulating small objects and getting access to things, and you often hear that younger sibs don’t bother trying to speak clearly or solve their own problems because they’ve got a very motivated slightly older helper to do it for them. Elder sib, in turn, gets to feel smart and useful, receive praise and perhaps train his or her curiosity skills.

Once the age difference becomes too much, babies become ‘boring’.

How about this: older siblings taking a role in parenting increases intellectual curiosity in the younger child. Now the younger child has the limited parenting time of the actual parents, plus the parenting of the older sibling- bringing them back up to the total level of parenting of the firstborn.

Does your survey data distinguish between full and half sibs?

Presumably siblings spaced more widely are more likely half sibs. And more likely to have different mothers. Some fraction of those widely spaced second sibs have different mothers and thus might be first offspring for their moms. Maybe a spike in this effect around 7 years?

In my own family experience, children who are 6 years apart play together, and the older is a strong influence on the younger. At 8 years apart, the older child barely gets to see the younger child, and is much less of an influence. I have two children 7 years apart, and it was quite rare that they could play together, the age gap was just a little too great. Sometimes they could play board games, as the younger is very smart, but almost all other games just did not happen. At five years gap, children play together all the time.

My guess is that 7 years is the maximum age gap that children can overcome while playing. Children’s biggest influence is their peers, and so if you have a sibling less than 8 years older than you, you play with them, and they are a huge influence on you. A sibling greater than that much away might as well not exist.

Children start playing games with other children when they are about 3 or 4. 8 years older puts children at 11 or 12, and just hitting puberty, and so too old to play with 3 and 4 year olds, though obviously girls especially play the role of mother at that age, and some love minding kids. When the older child leaves home at 18, the younger would be 10, and unable to appreciate the same movies, books or games that the older consumed.

You might think that 7 years is too big a gap to overcome, but older children really will play down, and younger will play up. I think the developmental milestones of reaching inter-group play at 4, puberty at 11, and leaving home at 18 give two seven year windows, and this results in the seven year effect.

My anecdotal experience agrees with this. My brother was 8 years older than me and we barely interacted. My wife’s brother is 6 years older than her and they were fairly close.

Yes. My oldest son is eight years older than my daughter–they have a really good relationship, but it’s not two kids playing together–instead, he’s almost like uncle or another parent for her.

My anecdotal evidence:

I am older brother to three sisters, triplets, 7 years younger than me.

We had a huge influence on each other. I tried to be the best brother there could be, as helpful to my parents and my siblings as possible. That was mainly being the judge in a lot of disputes where my parents did not care enough to find out who really was in the wrong and who should apologize to whom haha. And a looot of explaining. I loved it.

I remember how I noticed when they first started to really be able to have conversations. I think that was really fun and may have been a time where our relationship changed. Maybe that is the 4 and 11 years old period?

Well, I think the most interesting thing I have to contribute is this:

A thing I noticed very much is that I was to my sisters a sort of person that I had missed in my own life. My parents were caring, but not really the best at explaining stuff and making clear to me why thing had to be a certain way. I made sure to always calmly explain everything to my sisters, to make sure that everything is as reasoned as possible and as little “because I said so” as possible.

So.

Maybe this makes a significant difference in ones life?

I used to feel misunderstood so much.

Another thing is that obviously, I had a lot more alone time then them, which may have shaped my interests.

I’m sorry for poor style, this is not my native language and I’m tired

Probably a coincidence, but I’d note that 7 years is enough that (in most of the U.S., anyway), kids will never be at the same “level” of school, and will generally be two stages apart: younger sibling hits kindergarten when older sibling hits middle school, middle school when the older sibling is in college, etc.

This would be consistent with the “overshadowing” theory if the overshadowing is expressed more through social interaction with peers (and wanting to socially differentiate from siblings in that context) than through interaction at home.

This makes some sense. My sister (9 years younger) went to the same high school I did, and we had no teachers in common (so there was no “oh you’re so-and-so’s little sister).

My sister is 4.5 years older than me, which was enough to ensure that we never went to the same school at the same time. We didn’t associate with the same neighborhood kids either (though part of that was probably the gender difference). I don’t think there was a single person who knew both of us except for family and one boyfriend (and he only knew me because he was at our house a lot).

This is of particular concern to me – we have two children, aged 3 and 1, with a third on the way.

Assuming the issue is intra-family competition or parental investment, what steps should parents take to minimize the effect?

Man, I don’t know, I just run the surveys.

I’m skeptical about intra-family competition, though only from my own experience. My siblings and I are interested in lots of the same things, and we often collaborated more than competed. I see the same thing in my own children. They all have some different interests, but their interests overlap more than they don’t.

Parental investment, though: that’s very hard. My oldest monopolizes my attention. It’s not just that we gave him more attention initially; he seems to also rely on his parents more than his siblings do. Oddly enough, my youngest (we have 5) tends to monopolize my wife’s time. So we have this odd system where the oldest and youngest get more parental attention than the middle children.

The only thing I can think is to be sure to have regular (weekly?) one-on-one time with every child as well as time with all the children together. I don’t think you need equal time as much as each child needs a little regular time with each parent without competition.

Collaboration can also be a kind of competition, if there is a division of labor. The older child likely gets the most difficult role. Or the older child becomes the “manager” of the project.

The regular one-on-one time seems like a great idea, but it may have limited effect on the kinds of things you do during that time. For example, if you spend the whole one-on-one time playing or debating, but let kids work and study during the shared time, the younger kids may learn independence in debating, without independence in learning. (Making their own opinions, but not doing their own research, for example.)

MIDDLE CHILD SYNDROME STRIKES AGAIN

I thought the same thing.

My younger sister was born with latent-middle child syndrome; when our brother was born it became a chronic ache in her life.

I think that is excellent advice, and would address a lot of the theories brought up in the comments.

Aren’t we talking about very slight differences in total number of hours spent with each child, though? Doing some back of the envelope calculations: my wife (on extended maternity leave and spends pretty much all day with our kids) spends 9 hours a day with them on weekdays (our three year old is in school part time; our 1 year old still naps 3 hours a day). But she also spends part of the day doing housework and other things that is not directly “time with the kids”; call that two hours a day. It’s probably more. Down to 7 hours. Even if I’m not forgetting something – and I probably am – and even if “time spent with both kids simultaneously” somehow counts as half as valuable for these purposes as “time spent with one kid alone”, we’re talking a difference of 17 1/2 hours per week. That’s not nothing, but if we’re only talking about the fact that when my wife spends time with both kids, she’s actually spending more time with our eldest because he’s a little more interactive than our one year old, the difference is significantly less.

Actually, if the “parental investment” theory is correct, shouldn’t the difference in child achievement – or whatever we’re calling it – be the greatest for eldest children who have large gaps between themselves and their younger siblings? Those are the kids who get the most parental time to themselves. I’m definitely confused.

“My siblings and I are interested in lots of the same things, and we often collaborated more than competed.”

There’s both sibling rivalry (Cain and Abel) and sibling revelry (the Coen Brothers).

Are all of these differences necessarily bad even if it is a result of intra-family competition or parental investment?

Keep them separated. Get them to live like they’re single children.

Did the survey ask if siblings were from the same set of parents, vs being half-siblings? One thing that seems plausible to happen around the ~7-ish year mark is that the parents have split up and one or the other is having another child with a new partner. This would obviously make all sorts of family-environment aspects different from “normal” siblings.

Half-sibling data (especially, whether they’re children of the poll-taker’s mother or father) could also potentially shed some light on the maternal androgen hypothesis.

I have two older stepsisters and a (much) younger half sister. I have no idea how the question was phrased or how I answered it. I’m pretty sure I said I was the oldest, since I never lived with the steps. With half siblings, it is probably important to distinguish between half siblings who share a mom vs. half siblings who share a dad.

Unrelated, I wonder which is more common (half siblings connected by a mom vs. half siblings connected by a dad).

I expect dad. Men are fertile for a longer period. Also, children are usually raised by the mom after a split/divorce, so women are more likely to have a definite limit on how many children they want (at the same time at least, and they are usually too old by the time their first child grows up).

On the next survey you could ask whether the reader’s interests are generally similar to or different from those of their sibling (or something along those lines). Under the “intra-family competition” hypothesis, one would expect “different” to be a more common response for siblings with age gap less than 8 than for siblings with age gap 8 or more.

I like the general idea presented by other commenter (the comment disappeared since): interactions with siblings could plausibly be important. And interactions with older siblings will give you different skills/experiences than interactions with younger siblings.

If this was true, you would probably expect birth order effects to be stronger when you have more younger siblings. It would also make sense for those effects to grow with age gap, at least initially. This is actually somewhat consistent with the data.

I find it weird this is not mentioned in the prominent theories – are there reasons to exclude this?

Also does the data include half-siblings? 7 years is also close to the average marriage length, so maybe divorces influence the pattern?

Also curious about half-sibs (and even step-sibs). I went back to the questions asked, and there’s no indication that the responses should only be limited to full biological siblings. Also, no questions about divorce, which could be another complicating factor here.

I wonder about older siblings teaching things to their younger siblings–in my own experience, explaining things to someone is a good way of forcing myself to think them through, so older siblings might get a better and more systematic understanding of stuff by teaching it to their siblings.

I was thinking the same thing.

“Studies show that younger sons with older biological brothers (but not sisters!) are more likely to be homosexual. This holds true even if someone is adopted and never met their older brother. The most commonly-cited theory is that during a first pregnancy, the mother’s immune system may develop antibodies to some unexpected part of the male fetus”.

I got pretty interested in this, and after reading “Genes in conflict” realized it might be an evolutionary feature, and not a bug.

Imagine some masculinizing resource consumed during pregnancy necessary for heterosexual development and a fetal allele expressed during development that consumes that resource.

In a viscous ancestral population, who would be a primary competitor for mates? your younger brothers obviously. If a mutant allele over-consumed that resource and deprived your younger brothers of it, they develop into a homosexual, and you’ve defeated them in mate competition without violence.

caveat:

you need your younger brother’s evolutionary loss, weighted by a relatedness of .5, to be exceeded by your gain to get the argument to work. this is hamilton’s rule and i think this is pretty plausible in lots of societies (even those without primogeniture).

i thought this was pretty crazy, and asked robert trivers if it makes any sense as an explanation for why exclusive human male homosexuality persists (it does, although there are candidate gene studies forming a competing theory).

That’s pretty fascinating (and I like being in a world where people can just ask Robert Trivers stuff) but: